Interwar Era, Interwar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relatively short, yet featured many significant social, political, and economic changes throughout the world. Petroleum-based energy production and associated mechanisation led to the prosperous Roaring Twenties, a time of both

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relatively short, yet featured many significant social, political, and economic changes throughout the world. Petroleum-based energy production and associated mechanisation led to the prosperous Roaring Twenties, a time of both

Following the

Following the

The Roaring Twenties highlighted novel and highly visible social and cultural trends and innovations. These trends, made possible by sustained economic prosperity, were most visible in major cities like New York City, Chicago, Paris, Berlin, and London. The Jazz Age began and Art Deco peaked. For women, knee-length skirts and dresses became socially acceptable, as did bobbed hair with a Marcel wave. The young women who pioneered these trends were called " flappers". Not all was new: "normalcy" returned to politics in the wake of hyper-emotional wartime passions in the United States, France, and Germany. The leftist revolutions in Finland, Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Spain were defeated by conservatives, but succeeded in Russia, which became the base for Soviet Communism and Marxism–Leninism. In Italy the National Fascist Party came to power under

The Roaring Twenties highlighted novel and highly visible social and cultural trends and innovations. These trends, made possible by sustained economic prosperity, were most visible in major cities like New York City, Chicago, Paris, Berlin, and London. The Jazz Age began and Art Deco peaked. For women, knee-length skirts and dresses became socially acceptable, as did bobbed hair with a Marcel wave. The young women who pioneered these trends were called " flappers". Not all was new: "normalcy" returned to politics in the wake of hyper-emotional wartime passions in the United States, France, and Germany. The leftist revolutions in Finland, Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Spain were defeated by conservatives, but succeeded in Russia, which became the base for Soviet Communism and Marxism–Leninism. In Italy the National Fascist Party came to power under

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relatively short, yet featured many significant social, political, and economic changes throughout the world. Petroleum-based energy production and associated mechanisation led to the prosperous Roaring Twenties, a time of both

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War. The interwar period was relatively short, yet featured many significant social, political, and economic changes throughout the world. Petroleum-based energy production and associated mechanisation led to the prosperous Roaring Twenties, a time of both social mobility

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society ...

and economic mobility for the middle class. Automobiles, electric lighting, radio, and more became common among populations in the developed world. The indulgences of the era subsequently were followed by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, an unprecedented worldwide economic downturn that severely damaged many of the world's largest economies.

Politically, the era coincided with the rise of communism, starting in Russia with the October Revolution and Russian Civil War, at the end of World War I, and ended with the rise of fascism, particularly in Germany and in Italy. China was in the midst of half-a-century of instability and the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party. The empires of Britain, France and others faced challenges as imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

was increasingly viewed negatively in Europe, and independence movements emerged in many colonies; for example the south of Ireland became independent after much fighting.

The Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, and German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

s were dismantled, with the Ottoman territories and German colonies redistributed among the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, chiefly Britain and France. The western parts of the Russian Empire, Estonia, Finland, Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, and Poland became independent nations in their own right, and Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

(now Moldova and parts of Ukraine) chose to reunify with Romania.

The Russian communists managed to regain control of the other East Slavic states, Central Asia and the Caucasus, forming the Soviet Union. Ireland was partitioned between the independent Irish Free State and the British-controlled Northern Ireland after the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War ( ga, Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United ...

in which the Free State fought against "anti-treaty" Irish republicans, who opposed partition. In the Middle East, both Egypt and Iraq gained independence. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, countries in Latin America nationalised many foreign companies, most of which were American, in a bid to strengthen their own economies. The territorial ambitions of the Soviets, Japanese, Italians, and Germans led to the expansion of their domains.

The period ended at the beginning of World War II.

Turmoil in Europe

Following the

Following the Armistice of Compiègne

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

on 11 November 1918 that ended World War I, the years 1918–1924 were marked by turmoil as the Russian Civil War continued to rage on, and Eastern Europe struggled to recover from the devastation of the First World War and the destabilising effects of not just the collapse of the Russian Empire, but the destruction of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, and the Ottoman Empire, as well. There were numerous new or restored countries in Southern, Central and Eastern Europe, some small in size, such as Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

or Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, and some larger, such as Poland and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. The United States gained dominance in world finance. Thus, when Germany could no longer afford war reparations to Britain, France and other former members of the Entente

Entente, meaning a diplomatic "understanding", may refer to a number of agreements:

History

* Entente (alliance), a type of treaty or military alliance where the signatories promise to consult each other or to cooperate with each other in case o ...

, the Americans came up with the Dawes Plan and Wall Street invested heavily in Germany, which repaid its reparations to nations that, in turn, used the dollars to pay off their war debts to Washington. By the middle of the decade, prosperity was widespread, with the second half of the decade known as the Roaring Twenties.

International relations

The important stages of interwar diplomacy and international relations included resolutions of wartime issues, such as reparations owed by Germany and boundaries; American involvement in European finances and disarmament projects; the expectations and failures of the League of Nations; the relationships of the new countries to the old; the distrustful relations of the Soviet Union to the capitalist world; peace and disarmament efforts; responses to theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

starting in 1929; the collapse of world trade; the collapse of democratic regimes one by one; the growth of efforts at economic autarky; Japanese aggressiveness toward China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, occupying large amounts of Chinese land, as well as border disputes between the Soviet Union and Japan, leading to multiple clashes along the Soviet and Japanese occupied Manchurian border; Fascist diplomacy, including the aggressive moves by Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany; the Spanish Civil War; Italy's invasion and occupation of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

; the appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

of Germany's expansionist moves against the German-speaking nation of Austria, the region inhabited by ethnic Germans called the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

in Czechoslovakia, the remilitarisation of the League of Nations demilitarised zone of the German Rhineland region, and the last, desperate stages of rearmament as the Second World War increasingly loomed.

Disarmament was a very popular public policy. However, the League of Nations played little role in this effort, with the United States and Britain taking the lead. U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes sponsored the Washington Naval Conference of 1921 in determining how many capital ships each major country was allowed. The new allocations were actually followed and there were no naval races in the 1920s. Britain played a leading role in the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference

The Geneva Naval Conference was a conference held to discuss naval arms limitation, held in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1927. The aim of the conference was to extend the existing limits on naval construction which had been agreed in the Washington Na ...

and the 1930 London Conference that led to the London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Italy, and the United States that was signed on 22 April 1930. Seeking to address is ...

, which added cruisers and submarines to the list of ship allocations. However the refusal of Japan, Germany, Italy and the USSR to go along with this led to the meaningless Second London Naval Treaty of 1936. Naval disarmament had collapsed and the issue became rearming for a war against Germany and Japan.

Roaring Twenties

The Roaring Twenties highlighted novel and highly visible social and cultural trends and innovations. These trends, made possible by sustained economic prosperity, were most visible in major cities like New York City, Chicago, Paris, Berlin, and London. The Jazz Age began and Art Deco peaked. For women, knee-length skirts and dresses became socially acceptable, as did bobbed hair with a Marcel wave. The young women who pioneered these trends were called " flappers". Not all was new: "normalcy" returned to politics in the wake of hyper-emotional wartime passions in the United States, France, and Germany. The leftist revolutions in Finland, Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Spain were defeated by conservatives, but succeeded in Russia, which became the base for Soviet Communism and Marxism–Leninism. In Italy the National Fascist Party came to power under

The Roaring Twenties highlighted novel and highly visible social and cultural trends and innovations. These trends, made possible by sustained economic prosperity, were most visible in major cities like New York City, Chicago, Paris, Berlin, and London. The Jazz Age began and Art Deco peaked. For women, knee-length skirts and dresses became socially acceptable, as did bobbed hair with a Marcel wave. The young women who pioneered these trends were called " flappers". Not all was new: "normalcy" returned to politics in the wake of hyper-emotional wartime passions in the United States, France, and Germany. The leftist revolutions in Finland, Poland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Spain were defeated by conservatives, but succeeded in Russia, which became the base for Soviet Communism and Marxism–Leninism. In Italy the National Fascist Party came to power under Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

after threatening a March on Rome in 1922.

Most independent countries enacted women's suffrage in the interwar era, including Canada in 1917 (though Quebec held out longer), Britain in 1918, and the United States in 1920. There were a few major countries that held out until after the Second World War (such as France, Switzerland and Portugal). Leslie Hume argues:

: The women's contribution to the war effort combined with failures of the previous systems' of Government made it more difficult than hitherto to maintain that women were, both by constitution and temperament, unfit to vote. If women could work in munitions factories, it seemed both ungrateful and illogical to deny them a place in the polling booth. But the vote was much more than simply a reward for war work; the point was that women's participation in the war helped to dispel the fears that surrounded women's entry into the public arena.

In Europe, according to Derek Aldcroft and Steven Morewood, "Nearly all countries registered some economic progress in the 1920s and most of them managed to regain or surpass their pre-war income and production levels by the end of the decade." The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Greece did especially well, while Eastern Europe did poorly, due to the First World War and Russian Civil War. In advanced economies the prosperity reached middle class households and many in the working class with radio, automobiles

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport people instead of goods.

The year 1886 is regarded as ...

, telephones, and electric light

An electric light, lamp, or light bulb is an electrical component that produces light. It is the most common form of artificial lighting. Lamps usually have a base made of ceramic, metal, glass, or plastic, which secures the lamp in the soc ...

ing and appliances. There was unprecedented industrial growth, accelerated consumer demand and aspirations, and significant changes in lifestyle and culture. The media began to focus on celebrities, especially sports heroes and movie stars. Major cities built large sports stadiums for the fans, in addition to palatial cinemas. The mechanisation of agriculture

Mechanised agriculture or agricultural mechanization is the use of machinery and equipment, ranging from simple and basic hand tools to more sophisticated, motorized equipment and machinery, to perform agricultural operations. In modern times, po ...

continued apace, producing an expansion of output that lowered prices, and made many farm workers redundant. Often they moved to nearby industrial towns and cities.

Great Depression

TheGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

was a severe worldwide economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economical downturn that is result of lowered economic activity in one major or more national economies. Economic depression maybe related to one specific country were there is some economic ...

that took place after 1929. The timing varied across nations; in most countries it started in 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s. It was the longest, deepest, and most widespread depression of the 20th century. The depression originated in the United States and became worldwide news with the stock market crash of 29 October 1929 (known as Black Tuesday). Between 1929 and 1932, worldwide GDP fell by an estimated 15%. By comparison, worldwide GDP fell by less than 1% from 2008 to 2009 during the Great Recession. Some economies started to recover by the mid-1930s. However, in many countries, the negative effects of the Great Depression lasted until the beginning of World War II.

The Great Depression had devastating effects in countries both rich and poor

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little

Democracy and prosperity largely went together in the 1920s. Economic disaster led to a distrust in the effectiveness of democracy and its collapse in much of Europe and Latin America, including the Baltic and Balkan countries, Poland, Spain, and Portugal. Powerful expansionary anti-democratic regimes emerged in Italy, Japan, and Germany.

While communism was tightly contained in the isolated Soviet Union, fascism took control of the Kingdom of Italy in 1922; as the Great Depression worsened, Nazism emerged victorious in Germany, fascism spread to many other countries in Europe, and also played a major role in several countries in Latin America. Fascist parties sprang up, attuned to local right-wing traditions, but also possessing common features that typically included extreme militaristic nationalism, a desire for economic self-containment, threats and aggression toward neighbouring countries, oppression of minorities, a ridicule of democracy while using its techniques to mobilise an angry middle-class base, and a disgust with cultural liberalism. Fascists believed in power, violence, male superiority, and a "natural" hierarchy, often led by dictators such as

Democracy and prosperity largely went together in the 1920s. Economic disaster led to a distrust in the effectiveness of democracy and its collapse in much of Europe and Latin America, including the Baltic and Balkan countries, Poland, Spain, and Portugal. Powerful expansionary anti-democratic regimes emerged in Italy, Japan, and Germany.

While communism was tightly contained in the isolated Soviet Union, fascism took control of the Kingdom of Italy in 1922; as the Great Depression worsened, Nazism emerged victorious in Germany, fascism spread to many other countries in Europe, and also played a major role in several countries in Latin America. Fascist parties sprang up, attuned to local right-wing traditions, but also possessing common features that typically included extreme militaristic nationalism, a desire for economic self-containment, threats and aggression toward neighbouring countries, oppression of minorities, a ridicule of democracy while using its techniques to mobilise an angry middle-class base, and a disgust with cultural liberalism. Fascists believed in power, violence, male superiority, and a "natural" hierarchy, often led by dictators such as

The changing world order that the war had brought about, in particular the growth of the United States and Japan as naval powers, and the rise of independence movements in India and Ireland, caused a major reassessment of British imperial policy. Forced to choose between alignment with the United States or Japan, Britain opted not to renew the

The changing world order that the war had brought about, in particular the growth of the United States and Japan as naval powers, and the rise of independence movements in India and Ireland, caused a major reassessment of British imperial policy. Forced to choose between alignment with the United States or Japan, Britain opted not to renew the  India strongly supported the Empire in the First World War. It expected a reward, but failed to get sovereignty as the British Raj kept control in British hands and feared another rebellion like that of 1857. The Government of India Act 1919 failed to satisfy demand for independence. Mounting tension, particularly in the Punjab region, culminated in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919.

India strongly supported the Empire in the First World War. It expected a reward, but failed to get sovereignty as the British Raj kept control in British hands and feared another rebellion like that of 1857. The Government of India Act 1919 failed to satisfy demand for independence. Mounting tension, particularly in the Punjab region, culminated in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919.

French census statistics from 1938 show an imperial population with France at over 150 million people, outside of France itself, of 102.8 million people living on 13.5 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 64.7 million lived in Africa and 31.2 million lived in Asia; 900,000 lived in the

French census statistics from 1938 show an imperial population with France at over 150 million people, outside of France itself, of 102.8 million people living on 13.5 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 64.7 million lived in Africa and 31.2 million lived in Asia; 900,000 lived in the

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The Treaty stripped Germany of all of its overseas colonies, of

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The Treaty stripped Germany of all of its overseas colonies, of

Hitler's diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations, rejected the Versailles Treaty, and began to rearm. Retaking the Territory of the Saar Basin in the aftermath of a plebiscite that favoured returning to Germany, Hitler's Germany remilitarised the Rhineland, formed the Pact of Steel alliance with Mussolini's Italy, and sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Germany seized Austria, considered to be a German state, in 1938, and took over Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement with Britain and France. Forming a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939, Germany invaded Poland after Poland's refusal to cede the

Hitler's diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations, rejected the Versailles Treaty, and began to rearm. Retaking the Territory of the Saar Basin in the aftermath of a plebiscite that favoured returning to Germany, Hitler's Germany remilitarised the Rhineland, formed the Pact of Steel alliance with Mussolini's Italy, and sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Germany seized Austria, considered to be a German state, in 1938, and took over Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement with Britain and France. Forming a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939, Germany invaded Poland after Poland's refusal to cede the

In 1922, the leader of the Italian Fascist movement,

In 1922, the leader of the Italian Fascist movement,  After Great Britain signed the Anglo-Italian

After Great Britain signed the Anglo-Italian

The Japanese modelled their industrial economy closely on the most advanced Western European models. They started with textiles, railways, and shipping, expanding to electricity and machinery. The most serious weakness was a shortage of raw materials. Industry ran short of copper, and coal became a net importer. A deep flaw in the aggressive military strategy was a heavy dependence on imports including 100 percent of the aluminium, 85 percent of the iron ore, and especially 79 percent of the oil supplies. It was one thing to go to war with China or Russia, but quite another to be in conflict with the key suppliers, especially the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands, of oil and iron.

Japan joined the Allies of the First World War to make territorial gains. Together with the British Empire, it divided up Germany's territories scattered in the Pacific and on the Chinese coast; they did not amount to very much. The other Allies pushed back hard against Japan's efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Its occupation of Siberia proved unproductive. Japan's wartime diplomacy and limited military action had produced few results, and at the Paris Versailles peace conference. At the end of the war, Japan was frustrated in its ambitions. At the

The Japanese modelled their industrial economy closely on the most advanced Western European models. They started with textiles, railways, and shipping, expanding to electricity and machinery. The most serious weakness was a shortage of raw materials. Industry ran short of copper, and coal became a net importer. A deep flaw in the aggressive military strategy was a heavy dependence on imports including 100 percent of the aluminium, 85 percent of the iron ore, and especially 79 percent of the oil supplies. It was one thing to go to war with China or Russia, but quite another to be in conflict with the key suppliers, especially the United States, Britain, and the Netherlands, of oil and iron.

Japan joined the Allies of the First World War to make territorial gains. Together with the British Empire, it divided up Germany's territories scattered in the Pacific and on the Chinese coast; they did not amount to very much. The other Allies pushed back hard against Japan's efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Its occupation of Siberia proved unproductive. Japan's wartime diplomacy and limited military action had produced few results, and at the Paris Versailles peace conference. At the end of the war, Japan was frustrated in its ambitions. At the

The civilian government in Tokyo tried to minimise the Army's aggression in Manchuria, and announced it was withdrawing. On the contrary, the Army completed the conquest of Manchuria, and the civilian cabinet resigned. The political parties were divided on the issue of military expansion. Prime Minister Tsuyoshi tried to negotiate with China, but was assassinated in the May 15 Incident in 1932, which ushered in an era of nationalism and militarism led by the Imperial Japanese Army and supported by other right-wing societies. The IJA's nationalism ended civilian rule in Japan until after 1945.

The Army, however, was itself divided into cliques and factions with different strategic viewpoints. One faction viewed the Soviet Union as the main enemy; the other sought to build a mighty empire based in Manchuria and northern China. The Navy, while smaller and less influential, was also factionalised. Large-scale warfare, known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, began in August 1937, with naval and infantry attacks focused on Shanghai, which quickly spread to other major cities. There were numerous large-scale atrocities against Chinese civilians, such as the Nanjing massacre in December 1937, with mass murder and mass rape. By 1939 military lines had stabilised, with Japan in control of almost all of the major Chinese cities and industrial areas. A puppet government was set up. In the U.S., government and public opinion—even including those who were isolationist regarding Europe—was resolutely opposed to Japan and gave strong support to China. Meanwhile, the Japanese Army fared badly in large battles with the Soviet Red Army in Mongolia at the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in summer 1939. The USSR was too powerful. Tokyo and Moscow signed a nonaggression treaty in April 1941, as the militarists turned their attention to the European colonies to the south which had urgently-needed oil fields.

The civilian government in Tokyo tried to minimise the Army's aggression in Manchuria, and announced it was withdrawing. On the contrary, the Army completed the conquest of Manchuria, and the civilian cabinet resigned. The political parties were divided on the issue of military expansion. Prime Minister Tsuyoshi tried to negotiate with China, but was assassinated in the May 15 Incident in 1932, which ushered in an era of nationalism and militarism led by the Imperial Japanese Army and supported by other right-wing societies. The IJA's nationalism ended civilian rule in Japan until after 1945.

The Army, however, was itself divided into cliques and factions with different strategic viewpoints. One faction viewed the Soviet Union as the main enemy; the other sought to build a mighty empire based in Manchuria and northern China. The Navy, while smaller and less influential, was also factionalised. Large-scale warfare, known as the Second Sino-Japanese War, began in August 1937, with naval and infantry attacks focused on Shanghai, which quickly spread to other major cities. There were numerous large-scale atrocities against Chinese civilians, such as the Nanjing massacre in December 1937, with mass murder and mass rape. By 1939 military lines had stabilised, with Japan in control of almost all of the major Chinese cities and industrial areas. A puppet government was set up. In the U.S., government and public opinion—even including those who were isolationist regarding Europe—was resolutely opposed to Japan and gave strong support to China. Meanwhile, the Japanese Army fared badly in large battles with the Soviet Red Army in Mongolia at the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in summer 1939. The USSR was too powerful. Tokyo and Moscow signed a nonaggression treaty in April 1941, as the militarists turned their attention to the European colonies to the south which had urgently-needed oil fields.

ImageSize = width:800 height:200

PlotArea = width:640 height:140 left:65 bottom:20

AlignBars = late

Colors =

id:time value:rgb(0.7,0.7,1) #

id:period value:rgb(1,0.7,0.5) #

id:age value:rgb(0.95,0.85,0.5) #

id:era value:rgb(1,0.85,0.5) #

id:eon value:rgb(1,0.85,0.7) #

id:filler value:gray(0.8) # background bar

id:black value:black

Period = from:1900 till:1950

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:10 start:1900

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:1 start:1900

PlotData =

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:10 mark:(line,white) width:11 shift:(0,-5)

bar:Decades color:era

from:1920 till:1929 text: Twenties

from:1929 till:1939 text: Depression

bar:Machine color:era

from:1900 till:1945 text: Machine Age

bar:World.Wars color:era

from:1914 till:1918 text: WWI

from:1918 till:1939 text:Interwar period

from:1939 till:1946 text: WWII

online

. * Morris, Richard B. and Graham W. Irwin, eds. ''Harper Encyclopedia of the Modern World: A Concise Reference History from 1760 to the Present'' (1970

online

* Albrecht-Carrié, René. ''A Diplomatic History of Europe Since the Congress of Vienna'' (1958), 736pp; a basic introduction, 1815–195

online free to borrow

* Berg-Schlosser, Dirk, and Jeremy Mitchell, eds. ''Authoritarianism and democracy in Europe, 1919–39: comparative analyses'' (Springer, 2002). * Berman, Sheri. ''The Social Democratic Moment: Ideas and Politics in the Making of Interwar Europe'' (Harvard UP, 2009). * Bowman, Isaiah. ''The New World: Problems in Political Geography'' (4th ed. 1928) sophisticated global coverage; 215 maps

online

* Brendon, Piers. '' The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s'' (2000) a comprehensive global political history; 816p

excerpt

* Cambon, Jules, ed ''The Foreign Policy of the Powers'' (1935) Essays by experts that cover France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Russia and the United State

Online free

* Clark, Linda Darus, ed. ''Interwar America: 1920–1940: Primary Sources in U.S. History'' (2001) * Dailey, Andy, and David G. Williamson. (2012) ''Peacemaking, Peacekeeping: International Relations 1918–36'' (2012) 244 pp; textbook, heavily illustrated with diagrams and contemporary photographs and colour posters. * Doumanis, Nicholas, ed. ''The Oxford Handbook of European History, 1914–1945'' (Oxford UP, 2016). * Duus, Peter, ed., ''The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 6, The Twentieth Century'' (1989) pp 53–153, 217–340

online

* Feinstein, Charles H., Peter Temin, and Gianni Toniolo. ''The World Economy Between the World Wars'' (Oxford UP, 2008), a standard scholarly survey. * Freeman, Robert. ''The InterWar Years (1919–1939)'' (2014), brief survey * Garraty, John A. '' The Great Depression: An Inquiry into the Causes, Course, and Consequences of the Worldwide Depression of the Nineteen-1930s, As Seen by Contemporaries'' (1986). * Gathorne-Hardy, Geoffrey Malcolm. ''A Short History of International Affairs, 1920 to 1934'' (Oxford UP, 1952). *

Online free to borrow

* Grift, Liesbeth van de, and Amalia Ribi Forclaz, eds. ''Governing the Rural in Interwar Europe'' (2017) * Grossman, Mark ed. ''Encyclopedia of the Interwar Years: From 1919 to 1939'' (2000). * Hicks, John D. ''Republican Ascendancy, 1921-1933'' (1960) for US

online

* – a view from the Left. * Kaser, M. C. and E. A. Radice, eds. ''The Economic History of Eastern Europe 1919–1975: Volume II: Interwar Policy, The War, and Reconstruction'' (1987) * * Koshar, Rudy. ''Splintered Classes: Politics and the Lower Middle Classes in Interwar Europe'' (1990). * * Luebbert, Gregory M. ''Liberalism, Fascism, Or Social Democracy: Social Classes and the Political Origins of Regimes in Interwar Europe'' (Oxford UP, 1991). * * Matera, Marc, and Susan Kingsley Kent. ''The Global 1930s: The International Decade'' (Routledge, 2017

excerpt

* * *

also online free to borrow

* Murray, Williamson and Allan R. Millett, eds. ''Military Innovation in the Interwar Period'' (1998) * Newman, Sarah, and Matt Houlbrook, eds. ''The Press and Popular Culture in Interwar Europe'' (2015) * Overy, R.J. ''The Inter-War Crisis 1919–1939'' (2nd ed. 2007) * Rothschild, Joseph. ''East Central Europe Between the Two World Wars'' (U of Washington Press, 2017). * Seton-Watson, Hugh. (1945) ''Eastern Europe Between The Wars 1918–1941'' (1945

online

* – 550 pp; wide-ranging political, social and economic coverage of Britain, 1910–35 * Sontag, Raymond James. ''A Broken World, 1919–1939'' (1972

online free to borrow

wide-ranging survey of European history * Sontag, Raymond James. "Between the Wars." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 29.1 (1960): 1–1

online

* Steiner, Zara. ''The Lights that Failed: European International History 1919–1933''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. * Steiner, Zara. ''The Triumph of the Dark: European International History 1933–1939''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. * Toynbee, A. J. ''Survey of International Affairs 1920–1923'' (1924

online

''Survey of International Affairs'' annual 1920–193

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1924'' (1925); ''Survey of International Affairs 1925'' (1926

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1924'' (1925

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1927'' (1928

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1928'' (1929

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1929'' (1930

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1932'' (1933

online

''Survey of International Affairs 1934'' (1935), focus on Europe, Middle East, Far East; ''Survey of International Affairs 1936'' (1937

online

* Watt, D.C. et al., A History of the World in the Twentieth Century (1968) pp 301–530. * Wheeler-Bennett, John. ''Munich: Prologue To Tragedy,'' (1948) broad coverage of diplomacy of 1930s * Zachmann, Urs Matthias. ''Asia after Versailles: Asian Perspectives on the Paris Peace Conference and the Interwar Order, 1919–33'' (2017)

Mount Holyoke College edition

"Britain 1919 to the present"

Several large collections of primary sources and illustrations

{{Authority control . . Chronology of World War II Periodization

income< ...

. Personal income, tax revenue, profits, and prices dropped, while international trade plunged by more than 50%. Unemployment in the United States rose to 25% and in some countries rose as high as 33%. Prices fell sharply, especially for mining and agricultural commodities. Business profits fell sharply as well, with a sharp reduction in new business starts.

Cities all around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming communities and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by about 60%. Facing plummeting demand with few alternative sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as mining and logging suffered the most.

The Weimar Republic in Germany gave way to two episodes of political and economic turmoil, the first culminated in the German hyperinflation of 1923 and the failed Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and othe ...

of that same year. The second convulsion, brought on by the worldwide depression and Germany's disastrous monetary policies, resulted in the further rise of Nazism. In Asia, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

became an ever more assertive power, especially with regard to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Fascism displaces democracy

Democracy and prosperity largely went together in the 1920s. Economic disaster led to a distrust in the effectiveness of democracy and its collapse in much of Europe and Latin America, including the Baltic and Balkan countries, Poland, Spain, and Portugal. Powerful expansionary anti-democratic regimes emerged in Italy, Japan, and Germany.

While communism was tightly contained in the isolated Soviet Union, fascism took control of the Kingdom of Italy in 1922; as the Great Depression worsened, Nazism emerged victorious in Germany, fascism spread to many other countries in Europe, and also played a major role in several countries in Latin America. Fascist parties sprang up, attuned to local right-wing traditions, but also possessing common features that typically included extreme militaristic nationalism, a desire for economic self-containment, threats and aggression toward neighbouring countries, oppression of minorities, a ridicule of democracy while using its techniques to mobilise an angry middle-class base, and a disgust with cultural liberalism. Fascists believed in power, violence, male superiority, and a "natural" hierarchy, often led by dictators such as

Democracy and prosperity largely went together in the 1920s. Economic disaster led to a distrust in the effectiveness of democracy and its collapse in much of Europe and Latin America, including the Baltic and Balkan countries, Poland, Spain, and Portugal. Powerful expansionary anti-democratic regimes emerged in Italy, Japan, and Germany.

While communism was tightly contained in the isolated Soviet Union, fascism took control of the Kingdom of Italy in 1922; as the Great Depression worsened, Nazism emerged victorious in Germany, fascism spread to many other countries in Europe, and also played a major role in several countries in Latin America. Fascist parties sprang up, attuned to local right-wing traditions, but also possessing common features that typically included extreme militaristic nationalism, a desire for economic self-containment, threats and aggression toward neighbouring countries, oppression of minorities, a ridicule of democracy while using its techniques to mobilise an angry middle-class base, and a disgust with cultural liberalism. Fascists believed in power, violence, male superiority, and a "natural" hierarchy, often led by dictators such as Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

or Adolf Hitler. Fascism in power meant that liberalism and human rights were discarded, and individual pursuits and values were subordinated to what the party decided was best.

Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

To one degree or another, Spain had been unstable politically for centuries, and in 1936–1939 was wracked by one of the bloodiest civil wars of the 20th century. The real importance comes from outside countries. In Spain the conservative and Catholic elements and the army revolted against the newly elected government of the Second Spanish Republic, and full-scale civil war erupted. Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany gave munitions and strong military units to the rebelNationalist faction

The Nationalist faction ( es, Bando nacional) or Rebel faction ( es, Bando sublevado) was a major faction in the Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939. It was composed of a variety of right-leaning political groups that supported the Spanish Coup ...

, led by General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

. The Republican (or "Loyalist") government, was on the defensive, but it received significant help from the Soviet Union and Mexico. Led by Great Britain and France, and including the United States, most countries remained neutral and refused to provide armaments to either side. The powerful fear was that this localised conflict would escalate into a European conflagration that no one wanted.

The Spanish Civil War was marked by numerous small battles and sieges, and many atrocities, until the Nationalists won in 1939 by overwhelming the Republican forces. The Soviet Union provided armaments but never enough to equip the heterogeneous government militias and the "International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

" of outside far-left

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars consider ...

volunteers. The civil war did not escalate into a larger conflict, but did become a worldwide ideological battleground that pitted all the Communists and many socialists and liberals against Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, conservatives and fascists. Worldwide there was a decline in pacifism and a growing sense that another world war was imminent, and that it would be worth fighting for.

British Empire

The changing world order that the war had brought about, in particular the growth of the United States and Japan as naval powers, and the rise of independence movements in India and Ireland, caused a major reassessment of British imperial policy. Forced to choose between alignment with the United States or Japan, Britain opted not to renew the

The changing world order that the war had brought about, in particular the growth of the United States and Japan as naval powers, and the rise of independence movements in India and Ireland, caused a major reassessment of British imperial policy. Forced to choose between alignment with the United States or Japan, Britain opted not to renew the Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The first was an alliance between Britain and Japan, signed in January 1902. The alliance was signed in London at Lansdowne House on 30 January 1902 by Lord Lansdowne, British Foreign Secretary, and Hayashi Tadasu, Japanese diplomat. A dip ...

and instead signed the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, in which Britain accepted naval parity with the United States. The issue of the empire's security was a serious concern in Britain, as it was vital to the British pride, its finance, and its trade-oriented economy.

India strongly supported the Empire in the First World War. It expected a reward, but failed to get sovereignty as the British Raj kept control in British hands and feared another rebellion like that of 1857. The Government of India Act 1919 failed to satisfy demand for independence. Mounting tension, particularly in the Punjab region, culminated in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919.

India strongly supported the Empire in the First World War. It expected a reward, but failed to get sovereignty as the British Raj kept control in British hands and feared another rebellion like that of 1857. The Government of India Act 1919 failed to satisfy demand for independence. Mounting tension, particularly in the Punjab region, culminated in the Amritsar Massacre in 1919. Indian nationalism

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, b ...

surged and centred in the Congress Party

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

led by Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

. In Britain, public opinion was divided over the morality of the massacre between those who saw it as having saved India from anarchy and those who viewed it with revulsion. – 25 chapters; 845 pp

Egypt had been under ''de facto'' British control since the 1880s, despite its nominal ownership by the Ottoman Empire. In 1922, the Kingdom of Egypt was granted formal independence, though it continued to be a client state following British guidance. Egypt joined the League of Nations. Egypt's King Fuad and his son King Farouk and their conservative allies stayed in power with lavish lifestyles thanks to an informal alliance with Britain who would protect them from both secular and Muslim radicalism. Mandatory Iraq

The Kingdom of Iraq under British Administration, or Mandatory Iraq ( ar, الانتداب البريطاني على العراق '), was created in 1921, following the 1920 Iraqi Revolt against the proposed British Mandate of Mesopotamia, an ...

, a British mandate

Mandate most often refers to:

* League of Nations mandates, quasi-colonial territories established under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 June 1919

* Mandate (politics), the power granted by an electorate

Mandate may also ...

since 1920, gained official independence as the Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

in 1932 when King Faisal agreed to British terms of a military alliance and an assured flow of oil.

In Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, Britain was presented with the problem of mediating between the Palestinian Arabs and increasing numbers of Jewish settlers. The Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

, which had been incorporated into the terms of the mandate, stated that a national home for the Jewish people would be established in Palestine, and Jewish immigration allowed up to a limit that would be determined by the mandatory power. This led to increasing conflict with the Arab population, who openly revolted in 1936. As the threat of war with Germany increased during the 1930s, Britain judged the support of Arabs as more important than the establishment of a Jewish homeland, and shifted to a pro-Arab stance, limiting Jewish immigration and in turn triggering a Jewish insurgency.

The Dominions (Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the Irish Free State) were self-governing and gained semi-independence in the World War, while Britain still controlled foreign policy and defence. The right of the Dominions to set their own foreign policy was recognised in 1923 and formalised by the 1931 Statute of Westminster. (Southern) Ireland effectively broke all ties with Britain in 1937, leaving the Commonwealth and becoming an independent republic.

French Empire

French census statistics from 1938 show an imperial population with France at over 150 million people, outside of France itself, of 102.8 million people living on 13.5 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 64.7 million lived in Africa and 31.2 million lived in Asia; 900,000 lived in the

French census statistics from 1938 show an imperial population with France at over 150 million people, outside of France itself, of 102.8 million people living on 13.5 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 64.7 million lived in Africa and 31.2 million lived in Asia; 900,000 lived in the French West Indies

The French West Indies or French Antilles (french: Antilles françaises, ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy fwansez) are the parts of France located in the Antilles islands of the Caribbean:

* The two overseas departments of:

** Guadeloupe, ...

or islands in the South Pacific. The largest colonies were French Indochina with 26.8 million (in five separate colonies), French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

with 6.6 million, the French protectorate in Morocco, with 5.4 million, and French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

with 35.2 million in nine colonies. The total includes 1.9 million Europeans, and 350,000 "assimilated" natives.

Revolt in North Africa against Spain and France

The Berber independence leader Abd el-Krim (1882–1963) organised armed resistance against the Spanish and French for control of Morocco. The Spanish had faced unrest off and on from the 1890s, but in 1921, Spanish forces were massacred at the Battle of Annual. El-Krim founded an independent Rif Republic that operated until 1926, but had no international recognition. Eventually, France and Spain agreed to end the revolt. They sent in 200,000 soldiers, forcing el-Krim to surrender in 1926; he was exiled in the Pacific until 1947. Morocco was now pacified, and became the base from which Spanish Nationalists would launch theirrebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against the Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

in 1936.

Germany

Weimar Republic

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The Treaty stripped Germany of all of its overseas colonies, of

The humiliating peace terms in the Treaty of Versailles provoked bitter indignation throughout Germany, and seriously weakened the new democratic regime. The Treaty stripped Germany of all of its overseas colonies, of Alsace–Lorraine

Alsace–Lorraine, now called Alsace–Moselle, is a historical region located in France. It was created in 1871 by the German Empire after it had seized the region from the Second French Empire in the Franco-Prussian War with the Treaty of Fra ...

, and of predominantly Polish districts. The Allied armies occupied industrial sectors in western Germany including the Rhineland, and Germany was not allowed to have a real army, navy, or air force. Reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

were demanded, especially by France, involving shipments of raw materials, as well as annual payments.

When Germany defaulted on its reparation payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the heavily industrialised Ruhr district (January 1923). The German government encouraged the population of the Ruhr to passive resistance: shops would not sell goods to the foreign soldiers, coal mines would not dig for the foreign troops, trams in which members of the occupation army had taken seat would be left abandoned in the middle of the street. The German government printed vast quantities of paper money, causing hyperinflation, which also damaged the French economy

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

. The passive resistance proved effective, insofar as the occupation became a loss-making deal for the French government. But the hyperinflation caused many prudent savers to lose all the money they had saved. Weimar added new internal enemies every year, as anti-democratic Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, Nationalists, and Communists battled each other in the streets.

Germany was the first state to establish diplomatic relations with the new Soviet Union. Under the Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

, Germany accorded the Soviet Union ''de jure'' recognition, and the two signatories mutually agreed to cancel all pre-war debts and renounced war claims. In October 1925 the Treaty of Locarno was signed by Germany, France, Belgium, Britain, and Italy; it recognised Germany's borders with France and Belgium. Moreover, Britain, Italy, and Belgium undertook to assist France in the case that German troops marched into the demilitarised Rhineland. Locarno paved the way for Germany's admission to the League of Nations in 1926.

Nazi era, 1933–1939

Hitler came to power in January 1933, and inaugurated an aggressive power designed to give Germany economic and political domination across central Europe. He did not attempt to recover the lost colonies. Until August 1939, the Nazis denounced Communists and the Soviet Union as the greatest enemy, along with the Jews. Hitler's diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations, rejected the Versailles Treaty, and began to rearm. Retaking the Territory of the Saar Basin in the aftermath of a plebiscite that favoured returning to Germany, Hitler's Germany remilitarised the Rhineland, formed the Pact of Steel alliance with Mussolini's Italy, and sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Germany seized Austria, considered to be a German state, in 1938, and took over Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement with Britain and France. Forming a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939, Germany invaded Poland after Poland's refusal to cede the

Hitler's diplomatic strategy in the 1930s was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations, rejected the Versailles Treaty, and began to rearm. Retaking the Territory of the Saar Basin in the aftermath of a plebiscite that favoured returning to Germany, Hitler's Germany remilitarised the Rhineland, formed the Pact of Steel alliance with Mussolini's Italy, and sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Germany seized Austria, considered to be a German state, in 1938, and took over Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement with Britain and France. Forming a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939, Germany invaded Poland after Poland's refusal to cede the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

in September 1939. Britain and France declared war and World War II began – somewhat sooner than the Nazis expected or were ready for.

After establishing the "Rome-Berlin Axis

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were Na ...

" with Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, and signing the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan – which was joined by Italy a year later in 1937 – Hitler felt able to take the offensive in foreign policy. On 12 March 1938, German troops marched into Austria, where an attempted Nazi coup had been unsuccessful in 1934. When Austrian-born Hitler entered Vienna, he was greeted by loud cheers. Four weeks later, 99% of Austrians voted in favour of the annexation ( Anschluss) of their country Austria to the German Reich. After Austria, Hitler turned to Czechoslovakia, where the 3.5 million-strong Sudeten German

German Bohemians (german: Deutschböhmen und Deutschmährer, i.e. German Bohemians and German Moravians), later known as Sudeten Germans, were ethnic Germans living in the Czech lands of the Bohemian Crown, which later became an integral part ...

minority was demanding equal rights and self-government.Donald Cameron Watt, ''How war came: the immediate origins of the Second World War, 1938–1939'' (1989).R.J. Overy, ''The Origins of the Second World War'' (2014).

At the Munich Conference

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

of September 1938, Hitler, the Italian leader Benito Mussolini, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

, and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier agreed upon the cession of Sudeten territory to the German Reich by Czechoslovakia. Hitler thereupon declared that all of German Reich's territorial claims had been fulfilled. However, hardly six months after the Munich Agreement, in March 1939, Hitler used the smouldering quarrel between Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

and Czechs as a pretext for taking over the rest of Czechoslovakia as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In the same month, he secured the return of Memel from Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

to Germany. Chamberlain was forced to acknowledge that his policy of appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

towards Hitler had failed.

Italy

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, was appointed Prime Minister of Italy after the March on Rome. Mussolini resolved the question of sovereignty over the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

at the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

, which formalised Italian administration of both Libya and the Dodecanese Islands, in return for a payment to Turkey, the successor state to the Ottoman Empire, though he failed in an attempt to extract a mandate of a portion of Iraq from Britain.

The month following the ratification of the Treaty of Lausanne, Mussolini ordered the invasion of the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

after the Corfu incident. The Italian press supported the move, noting that Corfu had been a Venetian possession for four hundred years. The matter was taken by Greece to the League of Nations, where Mussolini was convinced by Britain to evacuate Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfre ...

troops, in return for reparations from Greece. The confrontation led Britain and Italy to resolve the question of Jubaland

Jubaland ( so, Jubbaland, ar, , it, Oltregiuba), the Juba Valley ( so, Dooxada Jubba) or Azania ( so, Asaaniya, ar, ), is a Federal Member State in southern Somalia. Its eastern border lies east of the Jubba River, stretching from Gedo t ...

in 1924, which was merged into Italian Somaliland.

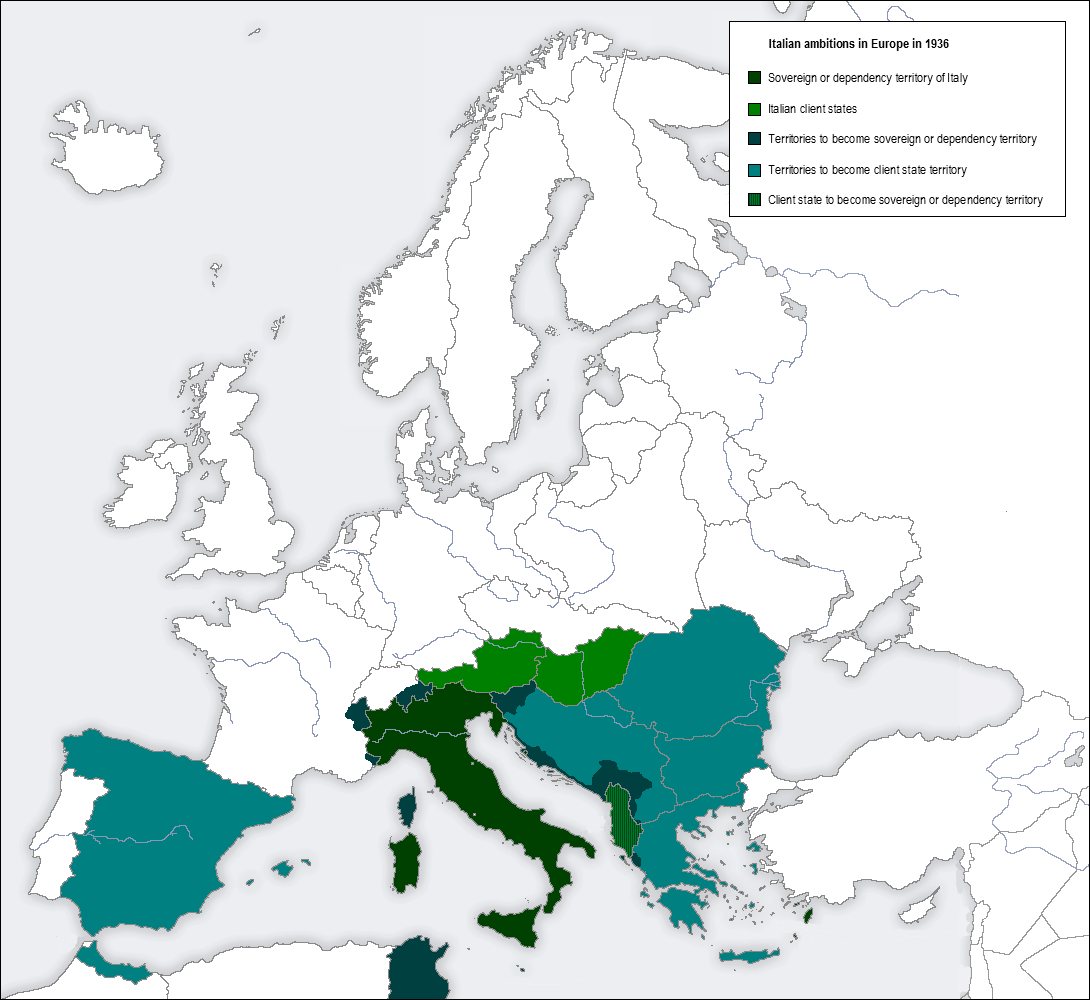

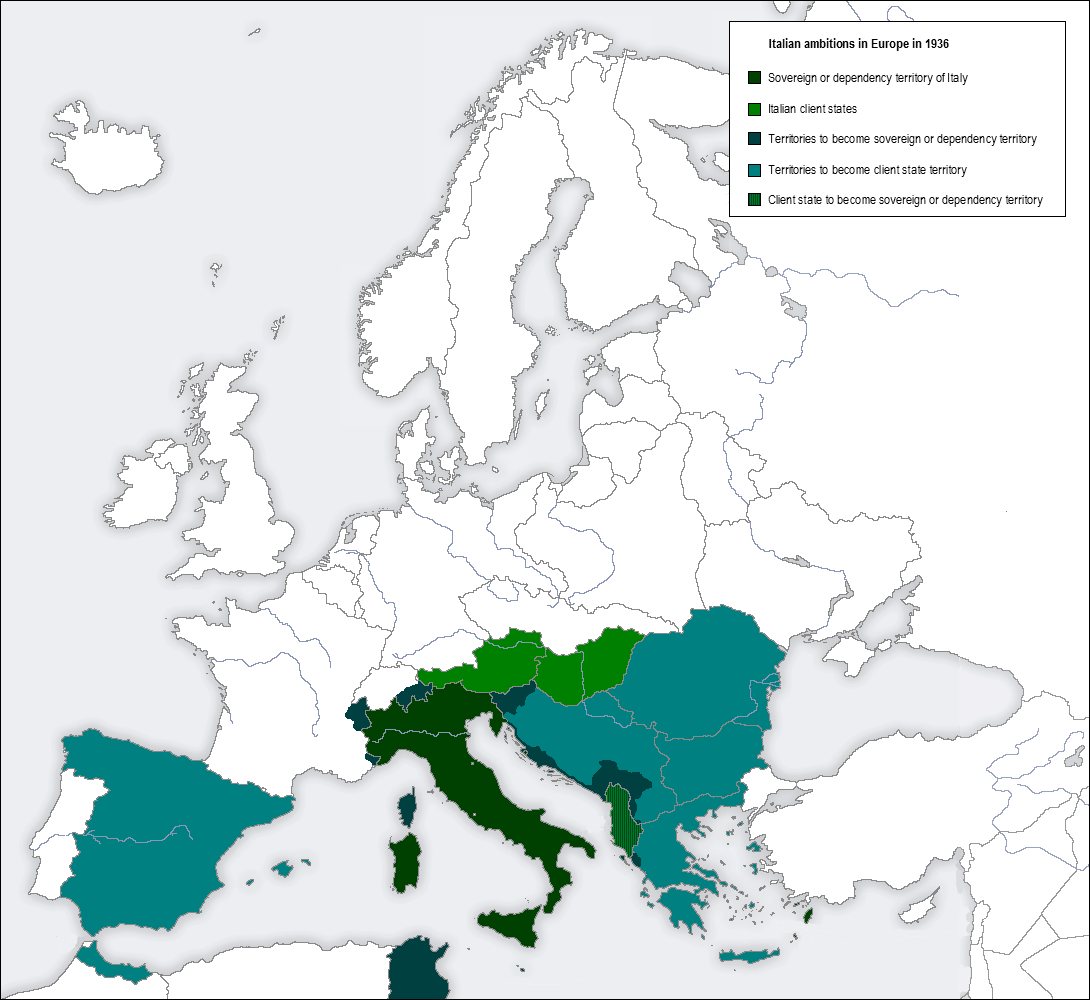

During the late 1920s, imperial expansion became an increasingly favoured theme in Mussolini's speeches. Amongst Mussolini's aims were that Italy had to become the dominant power in the Mediterranean that would be able to challenge France or Britain, as well as attain access to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Mussolini alleged that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty. This was elaborated on in a document he later drew up in 1939 called "The March to the Oceans", and included in the official records of a meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism. This text asserted that maritime position determined a nation's independence: countries with free access to the high seas were independent; while those who lacked this, were not. Italy, which only had access to an inland sea without French and British acquiescence, was only a "semi-independent nation", and alleged to be a "prisoner in the Mediterranean":

In the Balkans, the Fascist regime claimed Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

and held ambitions over Albania, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, and Greece based on the precedent of previous Roman dominance in these regions. Dalmatia and Slovenia were to be directly annexed into Italy while the remainder of the Balkans was to be transformed into Italian client states. The regime also sought to establish protective patron-client relationships with Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

In both 1932 and 1935, Italy demanded a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

of the former German Cameroon

Kamerun was an African colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1916 in the region of today's Republic of Cameroon. Kamerun also included northern parts of Gabon and the Congo with western parts of the Central African Republic, southwestern ...

and a free hand in the Ethiopian Empire from France in return for Italian support against Germany in the Stresa Front. This was refused by French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot, who was not yet sufficiently worried about the prospect of a German resurgence. The failed resolution of the Abyssinia Crisis led to the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, in which Italy annexed Ethiopia to its empire.

Italy's stance towards Spain shifted between the 1920s and the 1930s. The Fascist regime in the 1920s held deep antagonism towards Spain due to Miguel Primo de Rivera's pro-French foreign policy. In 1926, Mussolini began aiding the Catalan separatist movement, which was led by Francesc Macià, against the Spanish government. With the rise of the left-wing Republican government replacing the Spanish monarchy, Spanish monarchists and fascists repeatedly approached Italy for aid in overthrowing the Republican government, in which Italy agreed to support them to establish a pro-Italian government in Spain. In July 1936, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

of the Nationalist faction in the Spanish Civil War requested Italian support against the ruling Republican faction, and guaranteed that, if Italy supported the Nationalists, "future relations would be more than friendly" and that Italian support "would have permitted the influence of Rome to prevail over that of Berlin in the future politics of Spain". Italy intervened in the civil war with the intention of occupying the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

and creating a client state in Spain. Italy sought the control of the Balearic Islands due to its strategic position—Italy could use the islands as a base to disrupt the lines of communication between France and its North African colonies and between British Gibraltar

The history of Gibraltar, a small peninsula on the southern Iberian coast near the entrance of the Mediterranean Sea, spans over 2,900 years. The peninsula has evolved from a place of reverence in ancient times into "one of the most densely ...

and Malta. After the victory by Franco and the Nationalists in the war, Allied intelligence was informed that Italy was pressuring Spain to permit an Italian occupation of the Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

.

After Great Britain signed the Anglo-Italian

After Great Britain signed the Anglo-Italian Easter Accords

The Anglo-Italian Agreements of 1938, also called the Easter Pact or the Easter Accords (Italian: ''Patto'' or ''Accordi di Pasqua''), were a series of agreements concluded between the British and the Italian governments in Rome on 16 April 1938 ...

in 1938, Mussolini and Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano issued demands for concessions in the Mediterranean by France, particularly regarding French Somaliland

French Somaliland (french: Côte française des Somalis, lit= French Coast of the Somalis so, Xeebta Soomaaliyeed ee Faransiiska) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which time it became the French Ter ...

, Tunisia and the French-run Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

. Three weeks later, Mussolini told Ciano that he intended for an Italian takeover of Albania. Mussolini professed that Italy would only be able to "breathe easily" if it had acquired a contiguous colonial domain in Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Oceans, and when ten million Italians had settled in them. In 1938, Italy demanded a sphere of influence in the Suez Canal in Egypt, specifically demanding that the French-dominated Suez Canal Company accept an Italian representative on its board of directors. Italy opposed the French monopoly over the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

because, under the French-dominated Suez Canal Company, all merchant traffic to the Italian East Africa colony was forced to pay tolls on entering the canal.

Albanian Prime Minister and President Ahmet Zogu

Zog I ( sq, Naltmadhnija e tij Zogu I, Mbreti i Shqiptarëve, ; 8 October 18959 April 1961), born Ahmed Muhtar bey Zogolli, taking the name Ahmet Zogu in 1922, was the leader of Albania from 1922 to 1939. At age 27, he first served as Albania's y ...

, who had, in 1928, proclaimed himself King of Albania, failed to create a stable state. Albanian society was deeply divided by religion and language, with a border dispute with Greece and an undeveloped, rural economy. In 1939, Italy invaded and annexed Albania as a separate kingdom in personal union with the Italian crown. Italy had long built strong links with the Albanian leadership and considered it firmly within its sphere of influence. Mussolini wanted a spectacular success over a smaller neighbour to match Germany's annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia. Italian King Victor Emmanuel III took the Albanian crown, and a fascist government under Shefqet Vërlaci