Habsburg Moravia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a

Moravia borders

Moravia borders

Evidence of the presence of members of the human genus, ''

Evidence of the presence of members of the human genus, ''

A variety of Germanic and major Slavic tribes crossed through Moravia during the

A variety of Germanic and major Slavic tribes crossed through Moravia during the

Bohemia 1138–1254.jpg, Bohemia and Moravia in the 12th century

Brno - Kostel sv. Tomáše, místodžitelský palác a alegorická postava spravedlnosti.jpg, Church of St. Thomas in Brno, mausoleum of Moravian branch

Growth of Habsburg territories.jpg,

JanCerny.jpg,

Tatra 77.jpg, The

The Moravians are generally a Slavic ethnic group who speak various (generally more archaic) dialects of

The Moravians are generally a Slavic ethnic group who speak various (generally more archaic) dialects of

Johan_amos_comenius_1592-1671.jpg, Comenius

Gregor_Mendel_oval.jpg, Gregor Mendel

Jan Vilímek - František Palacký 2.jpg, František Palacký

Jasomir Mundy.jpg, Jaromír Mundy

Tomáš_Garrigue_Masaryk_1925.PNG, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

Leoš_Janáček.jpg, Leoš Janáček

Sigmund Freud, by Max Halberstadt (cropped).jpg, Sigmund Freud

Edmund_Husserl_1910s.jpg, Edmund Husserl

Alfons_Mucha_LOC_3c05828u.jpg, Alphonse Mucha

Adolf Loos (1870–1933) (vor 1920; Franz Löwy).jpg, Adolf Loos

Tomas_Bata.jpg, Tomáš Baťa

Kurt_gödel.jpg, Kurt Gödel

Fotothek_df_roe-neg_0006305_003_Emil_Zátopek-2.jpg, Emil Zátopek

Milan Kundera redux.jpg, Milan Kundera

Lendl_CU.jpg, Ivan Lendl

Notable people from Moravia include (in order of birth):

* Anton Pilgram (1450–1516), architect, sculptor and woodcarver

* Jan Ámos Komenský (Comenius) (1592–1670), educator and theologian, last bishop of Unity of the Brethren

* Georg Joseph Camellus (1661–1706),  *

*

Moravian museum official website

Moravian gallery official website

Moravian library official website

Moravian land archive official website

Province of Moravia – Czech Catholic Church – official website

Welcome to the 2nd largest city of the CR

Welcome to Olomouc, city of good cheer...

Znojmo – City of Virtue

* {{Authority control Counties of the Holy Roman Empire Geography of Central Europe Geography of the Czech Republic Historic counties in Moravia Historical regions in the Czech Republic Historical regions Subdivisions of Austria-Hungary

historical region

Historical regions (or historical areas) are geographical regions which at some point in time had a cultural, ethnic, linguistic or political basis, regardless of latterday borders. They are used as delimitations for studying and analysing socia ...

in the east of the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The Cz ...

and one of three historical Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic sinc ...

, with Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

and Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (, also , ; cs, České Slezsko; szl, Czeski Ślōnsk; sli, Tschechisch-Schläsing; german: Tschechisch-Schlesien; pl, Śląsk Czeski) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. Czech Silesia is ...

.

The medieval and early modern Margraviate of Moravia

The Margraviate of Moravia ( cs, Markrabství moravské; german: Markgrafschaft Mähren) was one of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown within the Holy Roman Empire existing from 1182 to 1918. It was officially administrated by a margrave in coopera ...

was a crown land

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it ...

of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were a number of incorporated states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods connected by feudal relations under the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of Bo ...

from 1348 to 1918, an imperial state

An Imperial State or Imperial Estate ( la, Status Imperii; german: Reichsstand, plural: ') was a part of the Holy Roman Empire with representation and the right to vote in the Imperial Diet ('). Rulers of these Estates were able to exercise s ...

of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

from 1004 to 1806, a crown land of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

from 1804 to 1867, and a part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with t ...

from 1867 to 1918. Moravia was one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

founded in 1918. In 1928 it was merged with Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (, also , ; cs, České Slezsko; szl, Czeski Ślōnsk; sli, Tschechisch-Schläsing; german: Tschechisch-Schlesien; pl, Śląsk Czeski) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. Czech Silesia is ...

, and then dissolved in 1949 during the abolition of the land system following the communist coup d'état.

Its area of 22,623.41 km2 is home to more than 3 million people.

The people are historically named Moravians

Moravians ( cs, Moravané or colloquially , outdated ) are a West Slavic ethnographic group from the Moravia region of the Czech Republic, who speak the Moravian dialects of Czech or Common Czech or a mixed form of both. Along with the Sil ...

, a subgroup of Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestr ...

, the other group being called Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

ns. Moravia also had been home of a large German-speaking population until their expulsion in 1945. The land takes its name from the Morava river, which runs from its north to south, being its principal watercourse. Moravia's largest city and historical capital is Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

. Before being sacked by the Swedish army

The Swedish Army ( sv, svenska armén) is the land force of the Swedish Armed Forces.

History

Svea Life Guards dates back to the year 1521, when the men of Dalarna chose 16 young able men as body guards for the insurgent nobleman Gustav Va ...

during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

, Olomouc

Olomouc (, , ; german: Olmütz; pl, Ołomuniec ; la, Olomucium or ''Iuliomontium'') is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 99,000 inhabitants, and its larger urban zone has a population of about 384,000 inhabitants (2019).

Located on th ...

served as the Moravian capital, and it is still the seat of the Archdiocese of Olomouc.

Toponymy

The region and former margraviate of Moravia, ''Morava'' in Czech, is named after its principal river Morava. It is theorized that the river's name is derived fromProto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo-E ...

''*mori'': "waters", or indeed any word denoting ''water'' or a ''marsh''.

The German name for Moravia is ''Mähren'', from the river's German name ''March''. This could have a different etymology, as ''march'' is a term used in the Medieval times for an outlying territory, a border or a frontier (cf. English ''march

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of Ma ...

'').

Geography

Moravia occupies most of the eastern part of theCzech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The Cz ...

. Moravian territory is naturally strongly determined, in fact, as the Morava river basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, the ...

, with strong effect of mountains in the west (''de facto'' main European continental divide) and partly in the east, where all the rivers rise.

Moravia occupies an exceptional position in Central Europe. All the highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

s in the west and east of this part of Europe run west–east, and therefore form a kind of filter, making north–south or south–north movement more difficult. Only Moravia with the depression of the westernmost Outer Subcarpathia

Outer Subcarpathia ( pl, Podkarpacie Zewnętrzne; uk, Прикарпаття, ''Prykarpattia''; cs, Vněkarpatské sníženiny; german: Karpatenvorland) denotes the depression area at the outer (western, northern and eastern) base of the Car ...

, wide, between the Bohemian Massif

The Bohemian Massif ( cs, Česká vysočina or ''Český masiv'', german: Böhmische Masse or ''Böhmisches Massiv'') is a geomorphological province in Central Europe. It is a large massif stretching over most of the Czech Republic, eastern Ger ...

and the Outer Western Carpathians

Divisions of the Carpathians are a categorization of the Carpathian mountains system.

Below is a detailed overview of the major subdivisions and ranges of the Carpathian Mountains. The Carpathians are a "subsystem" of a bigger Alps-Himalaya Sy ...

(gripping the meridian at a constant angle of 30°), provides a comfortable connection between the Danubian

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

and Polish regions, and this area is thus of great importance in terms of the possible migration routes of large mammals – both as regards periodically recurring seasonal migrations triggered by climatic oscillations in the prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, when permanent settlement started.

Moravia borders

Moravia borders Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

in the west, Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt ...

in the southwest, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

in the southeast, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

very shortly in the north, and Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (, also , ; cs, České Slezsko; szl, Czeski Ślōnsk; sli, Tschechisch-Schläsing; german: Tschechisch-Schlesien; pl, Śląsk Czeski) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. Czech Silesia is ...

in the northeast. Its natural boundary is formed by the Sudetes

The Sudetes ( ; pl, Sudety; german: Sudeten; cs, Krkonošsko-jesenická subprovincie), commonly known as the Sudeten Mountains, is a geomorphological subprovince in Central Europe, shared by Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic. They co ...

mountains in the north, the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

in the east and the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands

The Bohemian-Moravian Highlands ( cs, Českomoravská vrchovina or ''Vysočina''; german: Böhmisch-Mährische Höhe) is a geomorphological macroregion and mountain range in the Czech Republic. Its highest peaks are the Javořice at and Devět s ...

in the west (the border runs from Králický Sněžník

Králický Sněžník () or Śnieżnik (Polish: ) is a mountain in Eastern Bohemia, located on the border between the Czech Republic and Poland. With , it is the highest mountain of the Snieznik Mountains.

Etymology

The name ''Sněžník'' or ' ...

in the north, over Suchý vrch, across Upper Svratka Highlands

The Upper Svratka Highlands ( cs, Hornosvratecká vrchovina, german: Hohe Schwarza Bergeland) is a mountain range in Moravia, Czech Republic. The Highlands, together with the Křižanov Highlands threshold, form the Western-Moravian part of Mo ...

and Javořice Highlands to tripoint

A tripoint, trijunction, triple point, or tri-border area is a geographical point at which the boundaries of three countries or subnational entities meet. There are 175 international tripoints as of 2020. Nearly half are situated in rivers, la ...

nearby Slavonice in the south). The Thaya

The Thaya ( cs, Dyje ) is a river in Central Europe, the longest tributary to the river Morava. Its drainage basin is . It is ( with its longest source river German Thaya) long and meanders from west to east in the border area between Lower ...

river meanders along the border with Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

and the tripoint

A tripoint, trijunction, triple point, or tri-border area is a geographical point at which the boundaries of three countries or subnational entities meet. There are 175 international tripoints as of 2020. Nearly half are situated in rivers, la ...

of Moravia, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

is at the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river ( main stem); ...

of the Thaya and Morava rivers. The northeast border with Silesia runs partly along the Moravice, Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

and Ostravice rivers. Between 1782 and 1850, Moravia (also thus known as ''Moravia-Silesia'') also included a small portion of the former province of Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

– the Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, (historically also ''Oesterreichisch-Schlesien, Oesterreichisch Schlesien, österreichisch Schlesien''); cs, Rakouské Slezsko; pl, Śląsk Austriacki officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, (historically ''Herzogth ...

(when Frederick the Great annexed most of ancient Silesia (the land of upper and middle Oder river) to Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Silesia's southernmost part remained with the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

s).

Today Moravia includes the South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which tr ...

, the Zlín Region

Zlín Region ( cs, Zlínský kraj; , ) is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the south-eastern part of the historical region of Moravia. It is named after its capital Zlín. Together with the Olomouc Region it fo ...

, vast majority of the Olomouc Region

Olomouc Region ( cs, Olomoucký kraj; , ; pl, Kraj ołomuniecki) is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the north-western and central part of its historical region of Moravia (''Morava'') and in a small part of ...

, southeastern half of the Vysočina Region

The Vysočina Region (; cs, Kraj Vysočina "Highlands Region", , ) is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located partly in the south-eastern part of the historical region of Bohemia and partly in the south-west of the hist ...

and parts of the Moravian-Silesian, Pardubice

Pardubice (; german: Pardubitz) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 89,000 inhabitants. It is the capital city of the Pardubice Region and lies on the Elbe River. The historic centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban mon ...

and South Bohemian regions.

Geologically, Moravia covers a transitive area between the Bohemian Massif

The Bohemian Massif ( cs, Česká vysočina or ''Český masiv'', german: Böhmische Masse or ''Böhmisches Massiv'') is a geomorphological province in Central Europe. It is a large massif stretching over most of the Czech Republic, eastern Ger ...

and the Carpathians (from northwest to southeast), and between the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

basin and the North European Plain

The North European Plain (german: Norddeutsches Tiefland – North German Plain; ; pl, Nizina Środkowoeuropejska – Central European Plain; da, Nordeuropæiske Lavland and nl, Noord-Europese Laagvlakte ; French : ''Plaine d'Europe du Nord ...

(from south to northeast). Its core geomorphological features are three wide valleys, namely the Dyje-Svratka Valley (''Dyjsko-svratecký úval''), the Upper Morava Valley

Upper may refer to:

* Shoe upper or ''vamp'', the part of a shoe on the top of the foot

* Stimulant

Stimulants (also often referred to as psychostimulants or colloquially as uppers) is an overarching term that covers many drugs including thos ...

(''Hornomoravský úval'') and the Lower Morava Valley (''Dolnomoravský úval''). The first two form the westernmost part of the Outer Subcarpathia

Outer Subcarpathia ( pl, Podkarpacie Zewnętrzne; uk, Прикарпаття, ''Prykarpattia''; cs, Vněkarpatské sníženiny; german: Karpatenvorland) denotes the depression area at the outer (western, northern and eastern) base of the Car ...

, the last is the northernmost part of the Vienna Basin. The valleys surround the low range of Central Moravian Carpathians. The highest mountains of Moravia are situated on its northern border in Hrubý Jeseník, the highest peak is Praděd

Praděd (; german: Altvater; pl, Pradziad; literally " great grandfather") () is the highest mountain of the Hrubý Jeseník mountains, Moravia, Czech Silesia and Upper Silesia and is the fifth-highest mountain of the Czech Republic. The hig ...

(1491 m). Second highest is the massive of Králický Sněžník (1424 m) the third are the Moravian-Silesian Beskids

The Moravian-Silesian Beskids ( Czech: , sk, Moravsko-sliezske Beskydy) is a mountain range in the Czech Republic with a small part reaching to Slovakia. It lies on the historical division between Moravia and Silesia, hence the name. It is part ...

at the very east, with Smrk

Smrk may refer to:

* Smrk (Jizera Mountains), the highest mountain in the Jizera Mountains of Bohemia, Czech Republic at 1124m

* Smrk (Moravian-Silesian Beskids), a mountain in the Moravian-Silesian Beskids range in the Czech Republic

* Smrk (T� ...

(1278 m), and then south from here Javorníky (1072). The White Carpathians along the southeastern border rise up to 970 m at Velká Javořina. The spacious, but moderate Bohemian-Moravian Highlands

The Bohemian-Moravian Highlands ( cs, Českomoravská vrchovina or ''Vysočina''; german: Böhmisch-Mährische Höhe) is a geomorphological macroregion and mountain range in the Czech Republic. Its highest peaks are the Javořice at and Devět s ...

on the west reach 837 m at Javořice

Javořice (german: Jaborschützeberg) is a mountain in the Javořice Highlands mountain range within the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands in the Czech Republic. With an elevation of , it is the highest mountain of the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands and o ...

.

The fluvial system of Moravia is very cohesive, as the region border is similar to the watershed of the Morava river, and thus almost the entire area is drained exclusively by a single stream. Morava's far biggest tributaries are Thaya (Dyje) from the right (or west) and Bečva

The Bečva (; german: Betschwa, also ''Betsch'', ''Beczwa'') is a river in the Czech Republic. It is a left tributary of the river Morava. The Bečva is created by two source streams, the northern Rožnovská Bečva (whose valley separates the Mo ...

(east). Morava and Thaya meet at the southernmost and lowest (148 m) point of Moravia. Small peripheral parts of Moravia belong to the catchment area of Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

, Váh

The Váh (; german: Waag, ; hu, Vág; pl, WagWag

w Słowniku geograficznym Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów ...

and especially w Słowniku geograficznym Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów ...

Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows ...

(the northeast). The watershed line running along Moravia's border from west to north and east is part of the European Watershed. For centuries, there have been plans to build a waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other languages. A first distinction is necessary ...

across Moravia to join the Danube and Oder river systems, using the natural route through the Moravian Gate

The Moravian Gate ( cs, Moravská brána, pl, Brama Morawska, german: Mährische Pforte, sk, Moravská brána) is a geomorphological feature in the Moravian region of the Czech Republic and the Upper Silesia region in Poland. It is formed by t ...

.

History

Pre-history

Evidence of the presence of members of the human genus, ''

Evidence of the presence of members of the human genus, ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus ''Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' (modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely related ...

'', dates back more than 600,000 years in the paleontological area of Stránská skála.

Attracted by suitable living conditions, early modern humans settled in the region by the Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone to ...

period. The Předmostí archeological (Cro-magnon

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from Western Asia, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They i ...

) site in Moravia is dated to between 24,000 and 27,000 years old. Caves in Moravský kras were used by mammoth hunters. Venus of Dolní Věstonice

The Venus of Dolní Věstonice ( cs, Věstonická venuše) is a Venus figurine, a ceramic statuette of a nude female figure dated to 29,000–25,000 BCE (Gravettian industry). It was found at the Paleolithic site Dolní Věstonice in the Morav ...

, the oldest ceramic figure in the world, was found in the excavation of Dolní Věstonice by Karel Absolon.

Roman era

Around 60 BC, theCelt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic Volcae

The Volcae () were a Gallic tribal confederation constituted before the raid of combined Gauls that invaded Macedonia c. 270 BC and fought the assembled Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae in 279 BC. Tribes known by the name Volcae were found si ...

people withdrew from the region and were succeeded by the Germanic Quadi

The Quadi were a Germanic

*

*

*

people who lived approximately in the area of modern Moravia in the time of the Roman Empire. The only surviving contemporary reports about the Germanic tribe are those of the Romans, whose empire had its bo ...

. Some of the events of the Marcomannic Wars

The Marcomannic Wars ( Latin: ''bellum Germanicum et Sarmaticum'', "German and Sarmatian War") were a series of wars lasting from about 166 until 180 AD. These wars pitted the Roman Empire against, principally, the Germanic Marcomanni and Qu ...

took place in Moravia in AD 169–180. After the war exposed the weakness of Rome's northern frontier, half of the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

s (16 out of 33) were stationed along the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. In response to increasing numbers of Germanic settlers in frontier regions like Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now ...

, Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus ...

, Rome established two new frontier provinces on the left shore of the Danube, Marcomannia and Sarmatia

The Sarmatians (; grc, Σαρμαται, Sarmatai; Latin: ) were a large confederation of ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic peoples of classical antiquity who dominated the Pontic steppe from about the 3rd century BC to the 4th cent ...

, including today's Moravia and western Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

.

In the 2nd century AD, a Roman fortress stood on the vineyards hill known as german: link=no, Burgstall and cz, Hradisko ("hillfort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post- Ro ...

"), situated above the former village Mušov

Mušov (german: Muschau) is a cadastral area and a defunct village in the municipality of Pasohlávky, South Moravian Region, Czech Republic. It covers an area of .

Geography and history

Mušov was the lowest-lying village in the Břeclav Di ...

and above today's beach resort at Pasohlávky

Pasohlávky (german: Weißstätten) is a municipality and village in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 700 inhabitants. It is a summer resort at the Nové Mlýny Reservoir.

Geography

Pasohláv ...

. During the reign of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

, the 10th Legion was assigned to control the Germanic tribes who had been defeated in the Marcomannic Wars. In 1927, the archeologist Gnirs, with the support of president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk Tomáš () is a Czech and Slovak given name, equivalent to the name Thomas.

It may refer to:

* Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937), first President of Czechoslovakia

* Tomáš Baťa (1876–1932), Czech footwear entrepreneur

* Tomáš Berdych ...

, began research on the site, located 80 km from Vindobona

Vindobona (from Gaulish ''windo-'' "white" and ''bona'' "base/bottom") was a Roman military camp on the site of the modern city of Vienna in Austria. The settlement area took on a new name in the 13th century, being changed to Berghof, or now s ...

and 22 km to the south of Brno. The researchers found remnants of two masonry buildings, a ''praetorium

The Latin term (also and ) originally identified the tent of a general within a Roman castrum (encampment), and derived from the title praetor, which identified a Roman magistrate.Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 2 ed. ...

'' and a '' balneum'' ("bath"), including a ''hypocaustum

A hypocaust ( la, hypocaustum) is a system of central heating in a building that produces and circulates hot air below the floor of a room, and may also warm the walls with a series of pipes through which the hot air passes. This air can warm th ...

''. The discovery of bricks with the stamp of the Legio X Gemina

Legio X ''Gemina'' ("The Twins' Tenth Legion"), was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. It was one of the four legions used by Julius Caesar in 58 BC, for his invasion of Gaul. There are still records of the X ''Gemina'' in Vienna in the begi ...

and coins from the period of the emperors Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

, Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

and Commodus

Commodus (; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was a Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 176 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. ...

facilitated dating of the locality.

Ancient Moravia

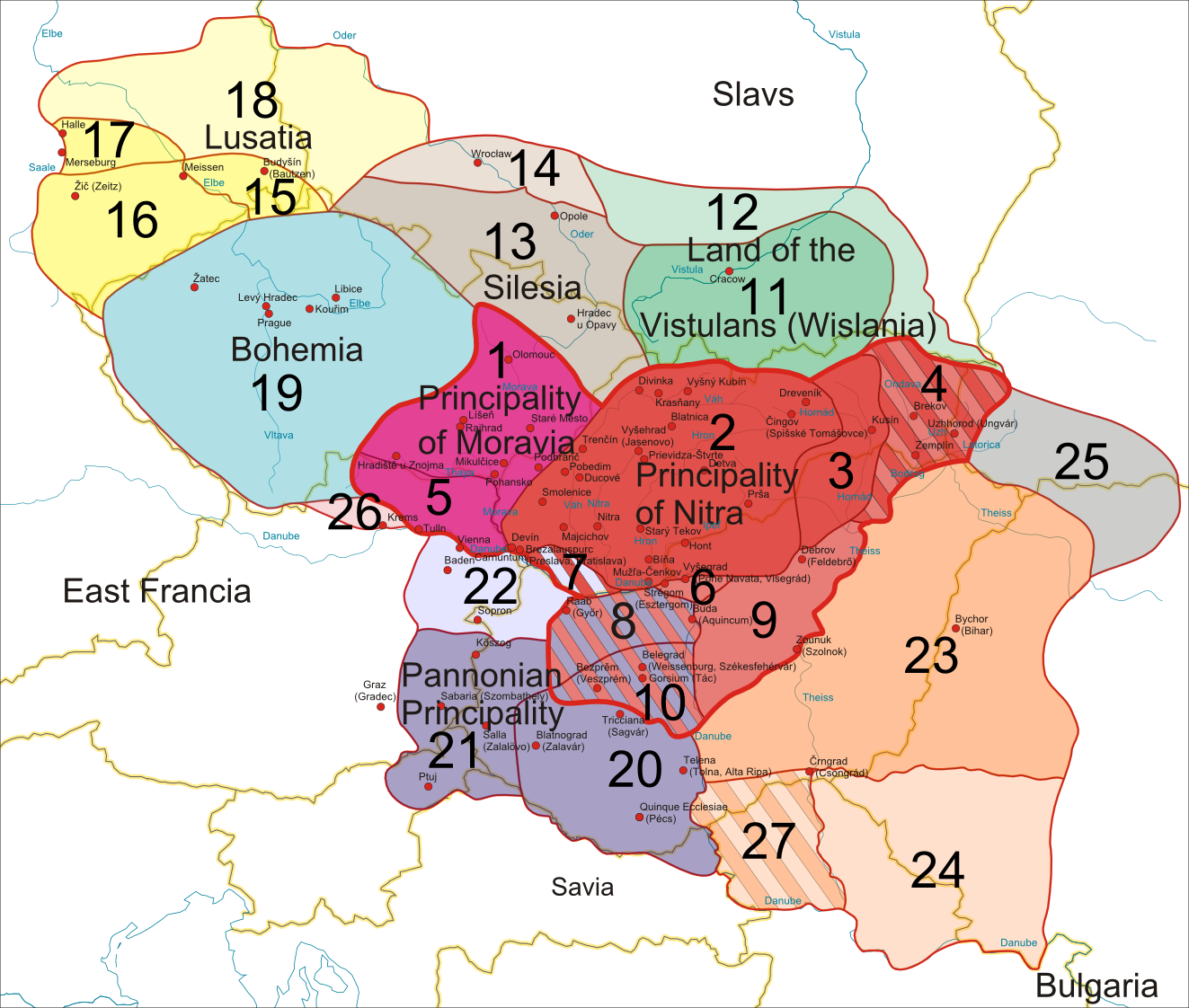

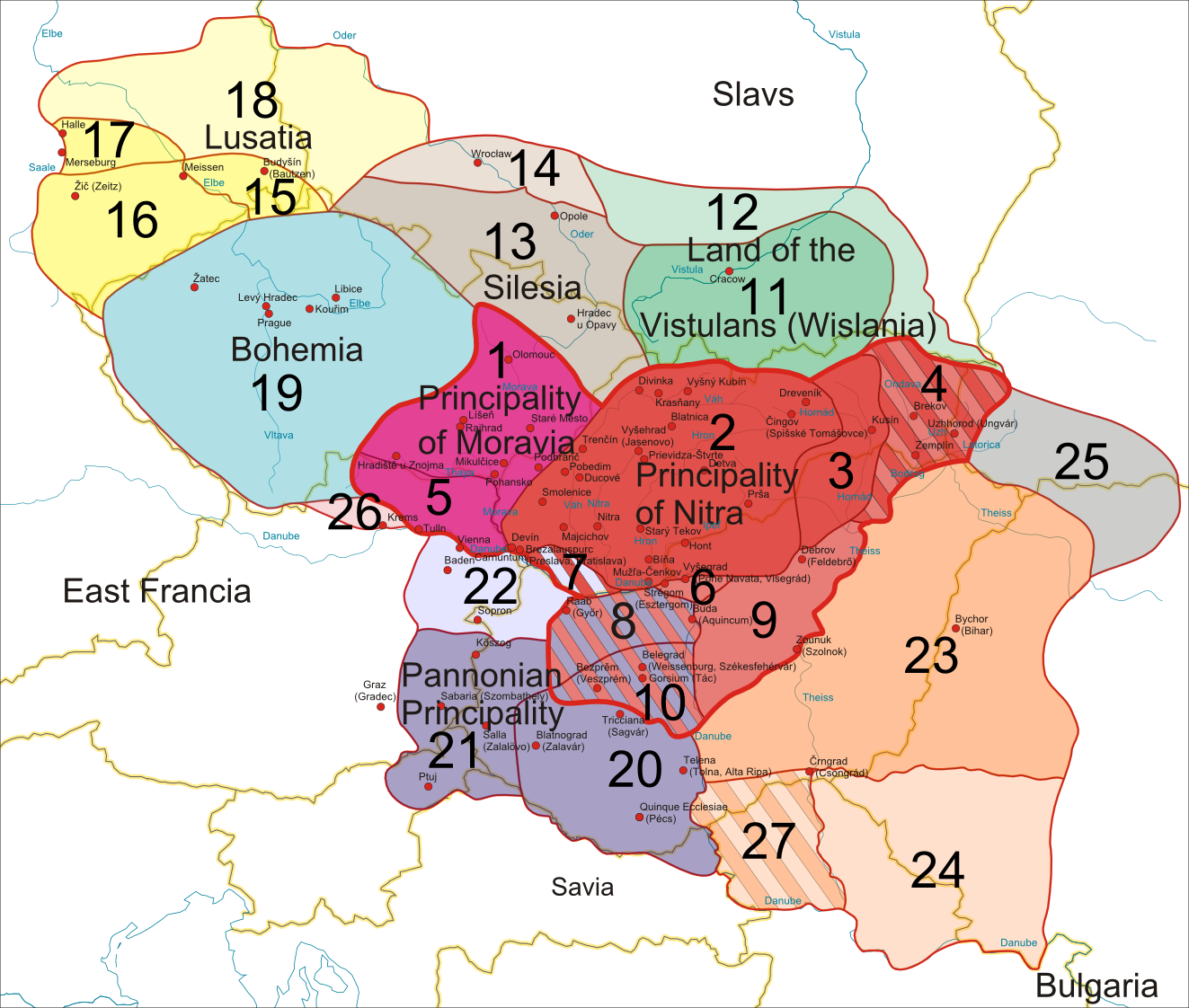

A variety of Germanic and major Slavic tribes crossed through Moravia during the

A variety of Germanic and major Slavic tribes crossed through Moravia during the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Rom ...

before Slavs established themselves in the 6th century AD. At the end of the 8th century, the Moravian Principality came into being in present-day south-eastern Moravia, Záhorie in south-western Slovakia and parts of Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt ...

. In 833 AD, this became the state of Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavic to ...

with the conquest of the Principality of Nitra

The Principality of Nitra ( sk, Nitrianske kniežatstvo, Nitriansko, Nitrava, lit=Duchy of Nitra, Nitravia, Nitrava; hu, Nyitrai Fejedelemség), also known as the Duchy of Nitra, was a West Slavic polity encompassing a group of settlements th ...

(present-day Slovakia). Their first king was Mojmír I

Mojmir I, Moimir I or Moymir I ( Latin: ''Moimarus'', ''Moymarus'', Czech and Slovak: ''Mojmír I.'') was the first known ruler of the Moravian Slavs (820s/830s–846) and eponym of the House of Mojmir. In modern scholarship, the creation o ...

(ruled 830–846). Louis the German

Louis the German (c. 806/810 – 28 August 876), also known as Louis II of Germany and Louis II of East Francia, was the first king of East Francia, and ruled from 843 to 876 AD. Grandson of emperor Charlemagne and the third son of Louis the P ...

invaded Moravia and replaced Mojmír I with his nephew Rastiz who became St. Rastislav. St. Rastislav (846–870) tried to emancipate his land from the Carolingian influence, so he sent envoys to Rome to get missionaries to come. When Rome refused he turned to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

to the Byzantine emperor Michael. The result was the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

who translated liturgical book

A liturgical book, or service book, is a book published by the authority of a church body that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.

Christianity Roman Rite

In the Roman Rite of the Catholic ...

s into Slavonic, which had lately been elevated by the Pope to the same level as Latin and Greek. Methodius became the first Moravian archbishop, the first archbishop in Slavic world, but after his death the German influence again prevailed and the disciples of Methodius were forced to flee. Great Moravia reached its greatest territorial extent in the 890s under Svatopluk I

Svatopluk I or Svätopluk I, also known as Svatopluk the Great (Latin: ''Zuentepulc'', ''Zuentibald'', ''Sventopulch'', ''Zvataplug''; Old Church Slavic: Свѧтопълкъ and transliterated ''Svętopъłkъ''; Polish: ''Świętopełk''; Greek ...

. At this time, the empire encompassed the territory of the present-day Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The Cz ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

, the western part of present Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croa ...

(Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now ...

), as well as Lusatia

Lusatia (german: Lausitz, pl, Łużyce, hsb, Łužica, dsb, Łužyca, cs, Lužice, la, Lusatia, rarely also referred to as Sorbia) is a historical region in Central Europe, split between Germany and Poland. Lusatia stretches from the Bóbr ...

in present-day Germany and Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

and the upper Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in t ...

basin in southern Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. After Svatopluk's death in 895, the Bohemian princes defected to become vassals of the East Frankish ruler Arnulf of Carinthia

Arnulf of Carinthia ( 850 – 8 December 899) was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894 and the disputed emperor from Fe ...

, and the Moravian state ceased to exist after being overrun by invading Magyars in 907.

Union with Bohemia

Following the defeat of the Magyars by EmperorOtto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of Hen ...

at the Battle of Lechfeld

The Battle of Lechfeld was a series of military engagements over the course of three days from 10–12 August 955 in which the Kingdom of Germany, led by King Otto I the Great, annihilated the Hungarian army led by '' Harka ''Bulcsú and the ch ...

in 955, Otto's ally Boleslaus I, the Přemyslid ruler of Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

, took control over Moravia. Bolesław I Chrobry Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

*Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, Pol ...

of Poland annexed Moravia in 999, and ruled it until 1019, when the Přemyslid prince Bretislaus recaptured it. Upon his father's death in 1034, Bretislaus became the ruler of Bohemia. In 1055, he decreed that Bohemia and Moravia would be inherited together by primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

, although he also provided that his younger sons should govern parts (quarters) of Moravia as vassals to his oldest son.

Throughout the Přemyslid era, junior princes often ruled all or part of Moravia from Olomouc

Olomouc (, , ; german: Olmütz; pl, Ołomuniec ; la, Olomucium or ''Iuliomontium'') is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 99,000 inhabitants, and its larger urban zone has a population of about 384,000 inhabitants (2019).

Located on th ...

, Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

or Znojmo

Znojmo (; german: Znaim) is a town in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 33,000 inhabitants. Znojmo is the historical and cultural centre of southwestern Moravia and the second most populated town in the South Moravian R ...

, with varying degrees of autonomy from the ruler of Bohemia. Dukes of Olomouc often acted as the "right hand" of Prague dukes and kings, while Dukes of Brno and especially those of Znojmo were much more insubordinate. Moravia reached its height of autonomy in 1182, when Emperor Frederick I Frederick I may refer to:

* Frederick of Utrecht or Frederick I (815/16–834/38), Bishop of Utrecht.

* Frederick I, Duke of Upper Lorraine (942–978)

* Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (1050–1105)

* Frederick I, Count of Zolle ...

elevated Conrad II Otto of Znojmo to the status of a margrave

Margrave was originally the medieval title for the military commander assigned to maintain the defence of one of the border provinces of the Holy Roman Empire or of a kingdom. That position became hereditary in certain feudal families in the ...

, immediately subject to the emperor, independent of Bohemia. This status was short-lived: in 1186, Conrad Otto was forced to obey the supreme rule of Bohemian duke Frederick. Three years later, Conrad Otto succeeded to Frederick as Duke of Bohemia and subsequently canceled his margrave title. Nevertheless, the margrave title was restored in 1197 when Vladislaus III of Bohemia resolved the succession dispute between him and his brother Ottokar

Ottokar is the medieval German form of the Germanic name Audovacar.

People with the name Ottokar include:

*Two kings of Bohemia, members of the Přemyslid dynasty

** Ottokar I of Bohemia (–1230)

** Ottokar II of Bohemia (–1278)

*Four Styrian m ...

by abdicating from the Bohemian throne and accepting Moravia as a vassal land of Bohemian (i.e., Prague) rulers. Vladislaus gradually established this land as Margraviate, slightly administratively different from Bohemia. After the Battle of Legnica

The Battle of Legnica ( pl, bitwa pod Legnicą), also known as the Battle of Liegnitz (german: Schlacht von Liegnitz) or Battle of Wahlstatt (german: Schlacht bei Wahlstatt), was a battle between the Mongol Empire and combined European forces t ...

, the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member of ...

carried their raids into Moravia.

The main line of the Přemyslid dynasty became extinct in 1306, and in 1310 John of Luxembourg

John the Blind or John of Luxembourg ( lb, Jang de Blannen; german: link=no, Johann der Blinde; cz, Jan Lucemburský; 10 August 1296 – 26 August 1346), was the Count of Luxembourg from 1313 and King of Bohemia from 1310 and titular King of ...

became Margrave of Moravia and King of Bohemia. In 1333, he made his son Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

the next Margrave of Moravia (later in 1346, Charles also became the King of Bohemia). In 1349, Charles gave Moravia to his younger brother John Henry who ruled in the margraviate until his death in 1375, after him Moravia was ruled by his oldest son Jobst of Moravia who was in 1410 elected the Holy Roman King but died in 1411 (he is buried with his father in the Church of St. Thomas in Brno – the Moravian capital from which they both ruled). Moravia and Bohemia remained within the Luxembourg dynasty of Holy Roman kings and emperors (except during the Hussite wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Ca ...

), until inherited by Albert II of Habsburg

Albert the Magnanimous KG, elected King of the Romans as Albert II (10 August 139727 October 1439) was king of the Holy Roman Empire and a member of the House of Habsburg. By inheritance he became Albert V, Duke of Austria. Through his wife ('' ...

in 1437.

After his death followed the interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

until 1453; land (as the rest of lands of the Bohemian Crown) was administered by the landfriedens (''landfrýdy''). The rule of young Ladislaus the Posthumous

Ladislaus the Posthumous( hu, Utószülött László; hr, Ladislav Posmrtni; cs, Ladislav Pohrobek; german: link=no, Ladislaus Postumus; 22 February 144023 November 1457) was Duke of Austria and King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia. He was t ...

subsisted only less than five years and subsequently (1458) the Hussite George of Poděbrady

George of Kunštát and Poděbrady (23 April 1420 – 22 March 1471), also known as Poděbrad or Podiebrad ( cs, Jiří z Poděbrad; german: Georg von Podiebrad), was the sixteenth King of Bohemia, who ruled in 1458–1471. He was a leader of the ...

was elected as the king. He again reunited all Czech lands (then Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Upper & Lower Lusatia) into one-man ruled state. In 1466, Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II ( la, Paulus II; it, Paolo II; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States

from 30 August 1464 to his death in July 1471. When his maternal uncle Eugene IV ...

excommunicated George and forbade all Catholics (i.e. about 15% of population) from continuing to serve him. The Hungarian crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

followed and in 1469 Matthias Corvinus

Matthias Corvinus, also called Matthias I ( hu, Hunyadi Mátyás, ro, Matia/Matei Corvin, hr, Matija/Matijaš Korvin, sk, Matej Korvín, cz, Matyáš Korvín; ), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490. After conducting several m ...

conquered Moravia and proclaimed himself (with assistance of rebelling Bohemian nobility Czech nobility consists of the noble families from historical Czech lands, especially in their narrow sense, i.e. nobility of Bohemia proper, Moravia and Austrian Silesia – whether these families originated from those countries or moved into them ...

) as the king of Bohemia.

The subsequent 21-year period of a divided kingdom was decisive for the rising awareness of a specific Moravian identity, distinct from that of Bohemia. Although Moravia was reunited with Bohemia in 1490 when Vladislaus Jagiellon, king of Bohemia, also became king of Hungary, some attachment to Moravian "freedoms" and resistance to government by Prague continued until the end of independence in 1620. In 1526, Vladislaus' son Louis died in battle and the Habsburg Ferdinand I was elected as his successor.

House of Luxembourg

The House of Luxembourg ( lb, D'Lëtzebuerger Haus; french: Maison de Luxembourg; german: Haus Luxemburg) or Luxembourg dynasty was a royal family of the Holy Roman Empire in the Late Middle Ages, whose members between 1308 and 1437 ruled as kin ...

, rulers of Moravia; and the old governor's palace, a former Augustinian abbey

Trebic podklasteri bazilika velka apsida.jpg, 12th century Romanesque St. Procopius Basilica in Třebíč

St. Procopius Basilica ( cs, Bazilika svatého Prokopa) is a Romanesque- Gothic Christian church in Třebíč, Czech Republic. It was built on the site of the original Virgin Mary's Chapel of the Benedictine monastery in 1240–1280. It became ...

Moravská orlice.jpg, The Moravian banner of arms, which first appeared in the medieval era

Habsburg rule (1526–1918)

After the death of KingLouis II of Hungary and Bohemia

Louis II ( cs, Ludvík, hr, Ludovik , hu, Lajos, sk, Ľudovít; 1 July 1506 – 29 August 1526) was King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia from 1516 to 1526. He was killed during the Battle of Mohács fighting the Ottomans, whose victory led to t ...

in 1526, Ferdinand I of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

was elected King of Bohemia and thus ruler of the Crown of Bohemia (including Moravia). The epoch 1526–1620 was marked by increasing animosity between Catholic Habsburg kings (emperors) and the Protestant Moravian nobility (and other Crowns') estates. Moravia, like Bohemia, was a Habsburg possession until the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fight ...

. In 1573 the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

University of Olomouc

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, ...

was established; this was the first university in Moravia. The establishment of a special papal seminary, Collegium Nordicum, made the University a centre of the Catholic Reformation and effort to revive Catholicism in Central and Northern Europe. The second largest group of students were from Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swed ...

.

Brno and Olomouc served as Moravia's capitals until 1641. As the only city to successfully resist the Swedish invasion, Brno become the sole capital following the capture of Olomouc. The Margraviate of Moravia had, from 1348 in Olomouc and Brno, its own Diet, or parliament, ''zemský sněm'' (''Landtag'' in German), whose deputies from 1905 onward were elected separately from the ethnically separate German and Czech constituencies.

The oldest surviving theatre building in Central Europe, the Reduta Theatre, was established in 17th-century Moravia. Ottoman Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

and Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

invaded the region in 1663, taking 12,000 captives. In 1740, Moravia was invaded by Prussian forces under in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

, and Olomouc was forced to surrender on 27 December 1741. A few months later the Prussians were repelled, mainly because of their unsuccessful siege of Brno in 1742. In 1758, Olomouc was besieged by Prussians again, but this time its defenders forced the Prussians to withdraw following the Battle of Domstadtl

The Battle of Domstadtl (also spelled Domstadt, cs, Domašov) was a battle between the Habsburg monarchy and the Kingdom of Prussia in the Moravian village of Domašov nad Bystřicí during the Third Silesian War (part of the Seven Years ...

. In 1777, a new Moravian bishopric was established in Brno, and the Olomouc bishopric was elevated to an archbishopric. In 1782, the Margraviate of Moravia was merged with Austrian Silesia

Austrian Silesia, (historically also ''Oesterreichisch-Schlesien, Oesterreichisch Schlesien, österreichisch Schlesien''); cs, Rakouské Slezsko; pl, Śląsk Austriacki officially the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, (historically ''Herzogth ...

into ''Moravia-Silesia'', with Brno as its capital. Moravia became a separate crown land of Austria again in 1849, and then became part of Cisleithania

Cisleithania, also ''Zisleithanien'' sl, Cislajtanija hu, Ciszlajtánia cs, Předlitavsko sk, Predlitavsko pl, Przedlitawia sh-Cyrl-Latn, Цислајтанија, Cislajtanija ro, Cisleithania uk, Цислейтанія, Tsysleitaniia it, Cislei ...

n Austria-Hungary after 1867. According to Austro-Hungarian census of 1910 the proportion of Czechs in the population of Moravia at the time (2.622.000) was 71.8%, while the proportion of Germans was 27.6%.

Habsburg Empire

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

Crown land

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it ...

s: growth of the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

territories and Moravia's status

Verwaltungsgliederung der Markgrafschaft Mähren 1893.svg, Administrative division of Moravia as crown land of Austria in 1893

20th century

Following the break-up of theAustro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise o ...

in 1918, Moravia became part of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. As one of the five lands of Czechoslovakia, it had restricted autonomy. In 1928 Moravia ceased to exist as a territorial unity and was merged with Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (, also , ; cs, České Slezsko; szl, Czeski Ślōnsk; sli, Tschechisch-Schläsing; german: Tschechisch-Schlesien; pl, Śląsk Czeski) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. Czech Silesia is ...

into the Moravian-Silesian Land (yet with the natural dominance of Moravia). By the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

(1938), the southwestern and northern peripheries of Moravia, which had a German-speaking majority, were annexed by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, and during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia

Occupation commonly refers to:

* Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

* Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, ...

(1939–1945), the remnant of Moravia was an administrative unit within the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German occ ...

.

In 1945 after the end of World War II and Allied defeat of Germany, Czechoslovakia expelled the ethnic German minority of Moravia to Germany and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populou ...

. The Moravian-Silesian Land was restored with Moravia as part of it and towns and villages that were left by the former German inhabitants, were re-settled by Czechs, Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4 ...

and reemigrants. In 1949 the territorial division of Czechoslovakia was radically changed, as the Moravian-Silesian Land was abolished and Lands were replaced by "''kraje''" (regions), whose borders substantially differ from the historical Bohemian-Moravian border, so Moravia politically ceased to exist after more than 1100 years (833–1949) of its history. Although another administrative reform in 1960 implemented (among others) the North Moravian and the South Moravian regions (''Severomoravský'' and ''Jihomoravský kraj''), with capitals in Ostrava and Brno respectively, their joint area was only roughly alike the historical state and, chiefly, there was no land or federal autonomy, unlike Slovakia.

After the fall of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and the whole Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, the Czechoslovak Federal Assembly condemned the cancellation of Moravian-Silesian land and expressed "firm conviction that this injustice will be corrected" in 1990. However, after the breakup

A relationship breakup, breakup, or break-up is the termination of a relationship. The act is commonly termed "dumping omeone in slang when it is initiated by one partner. The term is less likely to be applied to a married couple, where a bre ...

of Czechoslovakia into Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The Cz ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

in 1993, Moravian area remained integral to the Czech territory, and the latest administrative division of Czech Republic (introduced in 2000) is similar to the administrative division of 1949. Nevertheless, the federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

or separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

movement in Moravia is completely marginal.

The centuries-lasting historical Bohemian-Moravian border has been preserved up to now only by the Czech Roman Catholic Administration, as the Ecclesiastical Province of Moravia corresponds with the former Moravian-Silesian Land. The popular perception of the Bohemian-Moravian border's location is distorted by the memory of the 1960 regions (whose boundaries are still partly in use).

Jan Černý

Jan Černý (4 March 1874, in Uherský Ostroh, Moravia, Austria-Hungary – 10 April 1959, in Uherský Ostroh, Czechoslovakia) was a Czechoslovak civil servant and politician. He was the prime minister of Czechoslovakia from 1920 to 1921 and ...

, president of Moravia in 1922–1926, later also Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia

Map of Moravia.jpg, A general map of Moravia in the 1920s

First Czechoslovak Republic.SVG, In 1928, Moravia was merged into Moravia-Silesia, one of four lands of Czechoslovakia, together with Bohemia, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to th ...

and Subcarpathian Rus

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

.

Economy

An area inSouth Moravia

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

, around Hodonín

Hodonín (; german: Göding) is a town in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 24,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Hodonín is made up of only one administrative part.

Geography

Hodonín is located about southeast ...

and Břeclav

Břeclav (; german: Lundenburg) is a town in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 24,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Town parts of Charvátská Nová Ves and Poštorná are administrative parts of Břeclav.

Etymol ...

, is part of the Viennese Basin

The Vienna Basin (german: Wiener Becken, cz, Vídeňská pánev, sk, Viedenská kotlina, Hungarian: ''Bécsi-medence'') is a geologically young tectonic burial basin and sedimentary basin in the seam area between the Alps, the Carpathians and ...

. Petroleum and lignite

Lignite, often referred to as brown coal, is a soft, brown, combustible, sedimentary rock formed from naturally compressed peat. It has a carbon content around 25–35%, and is considered the lowest rank of coal due to its relatively low hea ...

are found there in abundance. The main economic centres of Moravia are Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

, Olomouc

Olomouc (, , ; german: Olmütz; pl, Ołomuniec ; la, Olomucium or ''Iuliomontium'') is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 99,000 inhabitants, and its larger urban zone has a population of about 384,000 inhabitants (2019).

Located on th ...

and Zlín

Zlín (in 1949–1989 Gottwaldov; ; german: Zlin) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 73,000 inhabitants. It is the seat of the Zlín Region and it lies on the Dřevnice river. It is known as an industrial centre. The development of t ...

, plus Ostrava

Ostrava (; pl, Ostrawa; german: Ostrau ) is a city in the north-east of the Czech Republic, and the capital of the Moravian-Silesian Region. It has about 280,000 inhabitants. It lies from the border with Poland, at the confluences of four rive ...

lying directly on the Moravian–Silesian border. As well as agriculture in general, Moravia is noted for its viticulture

Viticulture (from the Latin word for '' vine'') or winegrowing (wine growing) is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of '' Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine, ...

; it contains 94% of the Czech Republic's vineyard

A vineyard (; also ) is a plantation of grape-bearing vines, grown mainly for winemaking, but also raisins, table grapes and non-alcoholic grape juice. The science, practice and study of vineyard production is known as viticulture. Vineyar ...

s and is at the centre of the country's wine industry. Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and sou ...

have at least a 400-year-old tradition of slivovitz

Slivovitz is a fruit spirit (or fruit brandy) made from damson plums, often referred to as plum spirit (or plum brandy). If anyone else has a dictionary of some Slavic language that translates your word for slivovitz as "plum brandy", please a ...

making.

The Czech automotive industry also had a large role in the industry of Moravia in the 20th century; the factories of Wikov in Prostějov

Prostějov (; german: Proßnitz) is a city in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 43,000 inhabitants. The city is known for its fashion industry. The historical city centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban ...

and Tatra in Kopřivnice produced many automobiles.

Moravia is also the centre of the Czech firearm industry, as the vast majority of Czech firearms manufacturers (e.g. CZUB, Zbrojovka Brno

Pre-war Československá zbrojovka, akc.spol. (or a.s.) (Czechoslovak Armory)and post-war Zbrojovka Brno, n.p.(Brno Armory) was a maker of small arms, light artillery, and motor vehicles in Brno, Czechoslovakia. It also made other products and ...

, Czech Small Arms, Czech Weapons, ZVI, Great Gun) are found in Moravia. Almost all the well-known Czech sporting, self-defence, military and hunting firearms are made in Moravia. Meopta rifle scopes are of Moravian origin. The original Bren gun was conceived here, as were the assault rifles the CZ-805 BREN and Sa vz. 58, and the handguns CZ 75

The CZ 75 is a semi-automatic pistol made by Czech firearm manufacturer ČZUB. First introduced in 1975, it is one of the original " wonder nines" and features a staggered-column magazine, all-steel construction, and a hammer forged barrel. ...

and ZVI Kevin (also known as the "Micro Desert Eagle").

The Zlín Region

Zlín Region ( cs, Zlínský kraj; , ) is an administrative unit ( cs, kraj) of the Czech Republic, located in the south-eastern part of the historical region of Moravia. It is named after its capital Zlín. Together with the Olomouc Region it fo ...

hosts several aircraft manufacturers, namely Let Kunovice (also known as Aircraft Industries, a.s.), ZLIN AIRCRAFT a.s. Otrokovice (formerly known under the name Moravan Otrokovice), Evektor-Aerotechnik and Czech Sport Aircraft. Sport aircraft are also manufactured in Jihlava

Jihlava (; german: Iglau) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 50,000 inhabitants. Jihlava is the capital of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava River on the historical border between Moravia and Bohemia.

Historically, Jihlava ...

by Jihlavan Airplanes/ Skyleader.

Aircraft production in the region started in 1930s; after a period of low production post-1989, there are signs of recovery post-2010, and production is expected to grow from 2013 onwards.

Tatra 77

The Czechoslovakian Tatra 77 (T77) is by many considered to be the first serial-produced, truly aerodynamically-designed automobile. It was developed by Hans Ledwinka and Paul Jaray, the Zeppelin aerodynamic engineer. Launched in 1934, the Tatra ...

(1934)

Sportovní vůz Supersport.gif, WIKOV Supersport (1931)

Michael Thonet 14.jpg, Thonet No. 14 chair

The No. 14 chair is the most famous chair made by the Thonet chair company. Also known as the 'bistro chair', it was designed by Michael Thonet and introduced in 1859, becoming the world's first mass-produced item of furniture. It is made usin ...

M 290.002 Slovenská strela, Žleby zastávka – Žleby 02.jpg, The speed train Tatra M 290.0 Slovenská strela 1936

Zlin XIII OK-TBZ (8190833921).jpg, Zlín XIII aircraft on display at the National Technical Museum in Prague

Zetor 25A.jpg, Zetor 25A tractor

Electron microscope Mamut at the Institute of Scientific Instruments of the Czech Academy of Science in Brno (4).jpg, Electron microscope Brno

File:LET L-410NG OK-NGA ILA Berlin 2016 09.jpg, Aeroplane L 410 NG by Let Kunovice

File:Rifle scope.jpg, Precise rifle scope by MeOpta

File:CZ BREN 2.jpg, The (modern) BREN gun M 2 11

File:Czech Raildays 2012, Evo2 (01).jpg, The modern street car EVO 2

File:Czech Raildays 2012, ČD Bfhpvee295, 80-30 020-9 (03).jpg, Diesel railway coach class Bfhpvee295

Machinery industry

The machinery industry has been the most important industrial sector in the region, especially inSouth Moravia

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which trad ...

, for many decades. The main centres of machinery production are Brno (Zbrojovka Brno

Pre-war Československá zbrojovka, akc.spol. (or a.s.) (Czechoslovak Armory)and post-war Zbrojovka Brno, n.p.(Brno Armory) was a maker of small arms, light artillery, and motor vehicles in Brno, Czechoslovakia. It also made other products and ...

, Zetor

Zetor (since January 1, 2007, officially Zetor Tractors a.s.) is a Czech agricultural machinery manufacturer. It was founded in 1946. The company is based in Brno, Czech Republic. Since June 29, 2002, the only shareholder has been a Slovak co ...

, První brněnská strojírna, Siemens

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', ' ...

), Blansko ( ČKD Blansko, Metra), Kuřim

Kuřim (; german: Gurein) is a town in Brno-Country District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 11,000 inhabitants. It is the most populated town of Brno-Country District.

Geography

Kuřim is located about north of ...

( TOS Kuřim), Boskovice

Boskovice (; german: Boskowitz) is a town in Blansko District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 12,000 inhabitants. The area of the historic town centre, Jewish quarter, château complex and castle ruin is well prese ...

(Minerva, Novibra) and Břeclav

Břeclav (; german: Lundenburg) is a town in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 24,000 inhabitants.

Administrative parts

Town parts of Charvátská Nová Ves and Poštorná are administrative parts of Břeclav.

Etymol ...

(Otis Elevator Company

Otis Worldwide Corporation ( branded as the Otis Elevator Company, its former legal name) is an American company that develops, manufactures and markets elevators, escalators, moving walkways, and related equipment.

Based in Farmington, Connec ...

). A number of other, smaller machinery and machine parts factories, companies and workshops are spread over Moravia.

Electrical industry

The beginnings of the electrical industry in Moravia date back to 1918. The biggest centres of electrical production are Brno ( VUES, ZPA Brno,EM Brno

EM, Em or em may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* EM, the E major musical scale

* Em, the E minor musical scale

* Electronic music, music that employs electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology in its production

* En ...

), Drásov, Frenštát pod Radhoštěm and Mohelnice (currently Siemens).

Cities and towns

Cities

*Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

, c. 381,000 inhabitants, former land capital and nowadays capital of South Moravian Region

The South Moravian Region ( cs, Jihomoravský kraj; , ; sk, Juhomoravský kraj) is an administrative unit () of the Czech Republic, located in the south-western part of its historical region of Moravia (an exception is Jobova Lhota which tr ...