History of the Czech lands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Czech lands – an area roughly corresponding to the present-day Czech Republic – starts approximately 800,000 years BCE. A simple chopper from that age was discovered at the Red Hill ( cz, Červený kopec) archeological site in

The archeological site in Předmostí at Přerov represents the largest accumulation of human remains of the Gravettian culture,

known for creating so-called Venus figurines. One of such figurines is the famous Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000–25,000 BCE) found in

The archeological site in Předmostí at Přerov represents the largest accumulation of human remains of the Gravettian culture,

known for creating so-called Venus figurines. One of such figurines is the famous Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000–25,000 BCE) found in

The realm of Great Moravia probably was established in the area of today's Moravia and western Slovakia in the 830s. It saw the rise of the first ever Slavic literary culture in the Old Church Slavonic language and the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet dedicated to a Slavic language. Glagolitic was later simplified into the Cyrillic alphabet that is today used in Russia and many countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. Glagolitic was created by

The realm of Great Moravia probably was established in the area of today's Moravia and western Slovakia in the 830s. It saw the rise of the first ever Slavic literary culture in the Old Church Slavonic language and the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet dedicated to a Slavic language. Glagolitic was later simplified into the Cyrillic alphabet that is today used in Russia and many countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. Glagolitic was created by

Bořivoj from Levý Hradec was the first known member of the Přemyslid dynasty. In 880, he moved his residence to Prague Castle, which laid the foundation of the city of Prague that emerged centuries later. He was a vassal to the kings of Great Moravia and was baptised during the christanisation of Great Moravia by St. Cyril and St. Methodius. His son Spytihněv I together with the head of another major Bohemian tribe

Bořivoj from Levý Hradec was the first known member of the Přemyslid dynasty. In 880, he moved his residence to Prague Castle, which laid the foundation of the city of Prague that emerged centuries later. He was a vassal to the kings of Great Moravia and was baptised during the christanisation of Great Moravia by St. Cyril and St. Methodius. His son Spytihněv I together with the head of another major Bohemian tribe  In 1002, during the reign of the duke Vladivoj, the Duchy of Bohemia formally became a part of the Holy Roman Empire. After a period of dynastic infighting, Oldřich took power. His son

In 1002, during the reign of the duke Vladivoj, the Duchy of Bohemia formally became a part of the Holy Roman Empire. After a period of dynastic infighting, Oldřich took power. His son

In 1212 Ottokar I was granted a hereditary title of the King of Bohemia by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Thus began the Kingdom of Bohemia, which lasted de iure until the end of World War I. His reign marked the start of the German eastward colonization, which over time significantly altered the language composition of the Czech Lands. His son Wenceslaus I had to deal with the Mongol invasion of Europe at the start of 1240s. He managed to defend Bohemia, but Moravian lands were heavily plundered. When the Duke of Austria Frederick II died in 1246 without male heirs, Wenceslaus I tried to secure the Austrian lands by marrying his eldest son Vladislaus to Frederick's nice Gertrude. This plan failed because of Vladislaus's premature death in the year after. Wenceslaus I then decided for the invasion of Austria and he was successful. His successor, Ottokar II, continued the expansion of the realm. He gained more territory south of Austria and led two crusades against the pagan Old Prussians. He was hoping to gain the Imperial crown, but lost in the 1273 election to Rudolf of Habsburg, the first in a line of Habsburg emperors. Rudolf of Habsburg demanded that Ottokar II returns all of the lands he had acquired south of Bohemia. Ottokar refused and waged two wars against the emperor which ended with his death at the battlefield of Marchfeld in 1278.

The crown was passed to his 6-year-old son Wenceslaus II. Otto V, Margrave of Brandenburg ruled as a regent in his stead, later replaced by

In 1212 Ottokar I was granted a hereditary title of the King of Bohemia by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Thus began the Kingdom of Bohemia, which lasted de iure until the end of World War I. His reign marked the start of the German eastward colonization, which over time significantly altered the language composition of the Czech Lands. His son Wenceslaus I had to deal with the Mongol invasion of Europe at the start of 1240s. He managed to defend Bohemia, but Moravian lands were heavily plundered. When the Duke of Austria Frederick II died in 1246 without male heirs, Wenceslaus I tried to secure the Austrian lands by marrying his eldest son Vladislaus to Frederick's nice Gertrude. This plan failed because of Vladislaus's premature death in the year after. Wenceslaus I then decided for the invasion of Austria and he was successful. His successor, Ottokar II, continued the expansion of the realm. He gained more territory south of Austria and led two crusades against the pagan Old Prussians. He was hoping to gain the Imperial crown, but lost in the 1273 election to Rudolf of Habsburg, the first in a line of Habsburg emperors. Rudolf of Habsburg demanded that Ottokar II returns all of the lands he had acquired south of Bohemia. Ottokar refused and waged two wars against the emperor which ended with his death at the battlefield of Marchfeld in 1278.

The crown was passed to his 6-year-old son Wenceslaus II. Otto V, Margrave of Brandenburg ruled as a regent in his stead, later replaced by

Earlier in 1346, the Pope Clement VI declared the Emperor Louis IV a heretic and demanded a new

Earlier in 1346, the Pope Clement VI declared the Emperor Louis IV a heretic and demanded a new  In 1355, Charles IV travelled to Rome where he was crowned the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ruled as the Holy Roman Emperor for over 20 years and managed to secure the title of the King of Romans for his eldest son

In 1355, Charles IV travelled to Rome where he was crowned the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ruled as the Holy Roman Emperor for over 20 years and managed to secure the title of the King of Romans for his eldest son  Wenceslaus IV did not share the governance abilities of his father. In 1393, the torture and murder John of Nepomuk – vicar-general of the archbishop Jan of Jenštejn – sparked a noble rebellion. He was imprisoned for two years at Králův Dvůr and was only released after an intervention from his younger brother Sigismund, who had become the King of Hungary. In 1400, Wenceslaus IV was deposed as the Holy Roman Emperor, mainly due to his failure to address the

Wenceslaus IV did not share the governance abilities of his father. In 1393, the torture and murder John of Nepomuk – vicar-general of the archbishop Jan of Jenštejn – sparked a noble rebellion. He was imprisoned for two years at Králův Dvůr and was only released after an intervention from his younger brother Sigismund, who had become the King of Hungary. In 1400, Wenceslaus IV was deposed as the Holy Roman Emperor, mainly due to his failure to address the

After the Battle of Mohács, the Ottomans were unsuccessful in their Siege of Vienna in 1529 and Ferdinand I managed to sign the Treaty of Constantinopole, postponing the Ottoman expansion attempts. Ferdinand and his brother Charles V – who was the Holy Roman Emperor at the same time – had to deal with not only the Ottoman threat, but also with the Schmalkaldic League which formed in 1531 to advance the interests of Lutheran states in the Holy Roman Empire. Largely Protestant Czech nobility had a favorable view of the Schmalkaldic League's goals and so when in 1546 Ferdinand I ordered the Czech estates to raise their army and march against the Protestant

After the Battle of Mohács, the Ottomans were unsuccessful in their Siege of Vienna in 1529 and Ferdinand I managed to sign the Treaty of Constantinopole, postponing the Ottoman expansion attempts. Ferdinand and his brother Charles V – who was the Holy Roman Emperor at the same time – had to deal with not only the Ottoman threat, but also with the Schmalkaldic League which formed in 1531 to advance the interests of Lutheran states in the Holy Roman Empire. Largely Protestant Czech nobility had a favorable view of the Schmalkaldic League's goals and so when in 1546 Ferdinand I ordered the Czech estates to raise their army and march against the Protestant

Maximilian II succeeded Ferdinand I in 1562 and – like his father – ruled from Vienna. He approved

Maximilian II succeeded Ferdinand I in 1562 and – like his father – ruled from Vienna. He approved

He was succeeded by his cousin Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria. The Diets of Bohemia confirmed Ferdinand's position as Matthias' successor only after he had promised to respect the Letter of Majesty – a document granting religious freedoms, signed by Rudolf II. eight years earlier. Ferdinand II did not share the religious benevolence of his predecessors. A year after he was crowned, he prohibited the construction of Protestant ecclesial buildings on royal land. That led to protests among the Protestant nobility – who saw it as a violation of the Letter of Majesty – and the

He was succeeded by his cousin Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria. The Diets of Bohemia confirmed Ferdinand's position as Matthias' successor only after he had promised to respect the Letter of Majesty – a document granting religious freedoms, signed by Rudolf II. eight years earlier. Ferdinand II did not share the religious benevolence of his predecessors. A year after he was crowned, he prohibited the construction of Protestant ecclesial buildings on royal land. That led to protests among the Protestant nobility – who saw it as a violation of the Letter of Majesty – and the

In 1648, the Thirty Years War finally ended with the

In 1648, the Thirty Years War finally ended with the

Charles VI had no male heirs and with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 he ensured that all the titles held by him could be inherited by a woman. Charles VI sought the other European powers' approval, which he gained in exchange for various concessions. Regardless, after her father's death, Maria Theresa had to defend her inheritance from the coalition of Prussia, Bavaria, France, Spain, Saxony and Poland in the War of Austrian Succession, that broke out mere weeks after her coronation in 1740. She ultimately managed to defend her title, but paid for it with the loss of Silesia, which became a part of Prussia. That was the ended the unity of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In 1757 during the Seven Years' War, the Prussians invaded Bohemia again and laid siege to Prague, but subsequently lost the

Charles VI had no male heirs and with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 he ensured that all the titles held by him could be inherited by a woman. Charles VI sought the other European powers' approval, which he gained in exchange for various concessions. Regardless, after her father's death, Maria Theresa had to defend her inheritance from the coalition of Prussia, Bavaria, France, Spain, Saxony and Poland in the War of Austrian Succession, that broke out mere weeks after her coronation in 1740. She ultimately managed to defend her title, but paid for it with the loss of Silesia, which became a part of Prussia. That was the ended the unity of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In 1757 during the Seven Years' War, the Prussians invaded Bohemia again and laid siege to Prague, but subsequently lost the

In 1805,

In 1805,

Throughout the 19th century, the nationalist tendencies and movements in the Czech lands known as the Czech National Revival slowly grew, led by activists such as linguists Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, historian and politician František Palacký or writer Božena Němcová and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský. The efforts of the Czech National Revival first peaked during the revolutions of 1848. Ferdinand I was forced to abdicate and his successor was his young nephew Francis Joseph I. When he – after losing the war with Italy in 1859 – also lost the war with Prussia in 1866, the Hungarian representatives forced Francis Joseph I to end his absolutist rule over Hungary in the

Throughout the 19th century, the nationalist tendencies and movements in the Czech lands known as the Czech National Revival slowly grew, led by activists such as linguists Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, historian and politician František Palacký or writer Božena Němcová and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský. The efforts of the Czech National Revival first peaked during the revolutions of 1848. Ferdinand I was forced to abdicate and his successor was his young nephew Francis Joseph I. When he – after losing the war with Italy in 1859 – also lost the war with Prussia in 1866, the Hungarian representatives forced Francis Joseph I to end his absolutist rule over Hungary in the

The newly formed Real union of Austria-Hungary lasted for the next half-a-century. The policies suppressing the National Revival in the Czech lands under the Austrian government continued, as well as the suppression of the Slovak National Revival under the Hungarian government. The end of the 19th century also was a time of a demographic boom and a rapid urbanization. Population in centers of industry doubled or tripled within a few decades. At the start of the 20th century, Austria's unilateral annexation of Bosnia in 1908 caused the Bosnian Crisis and prompted the eventual assassination of

The newly formed Real union of Austria-Hungary lasted for the next half-a-century. The policies suppressing the National Revival in the Czech lands under the Austrian government continued, as well as the suppression of the Slovak National Revival under the Hungarian government. The end of the 19th century also was a time of a demographic boom and a rapid urbanization. Population in centers of industry doubled or tripled within a few decades. At the start of the 20th century, Austria's unilateral annexation of Bosnia in 1908 caused the Bosnian Crisis and prompted the eventual assassination of

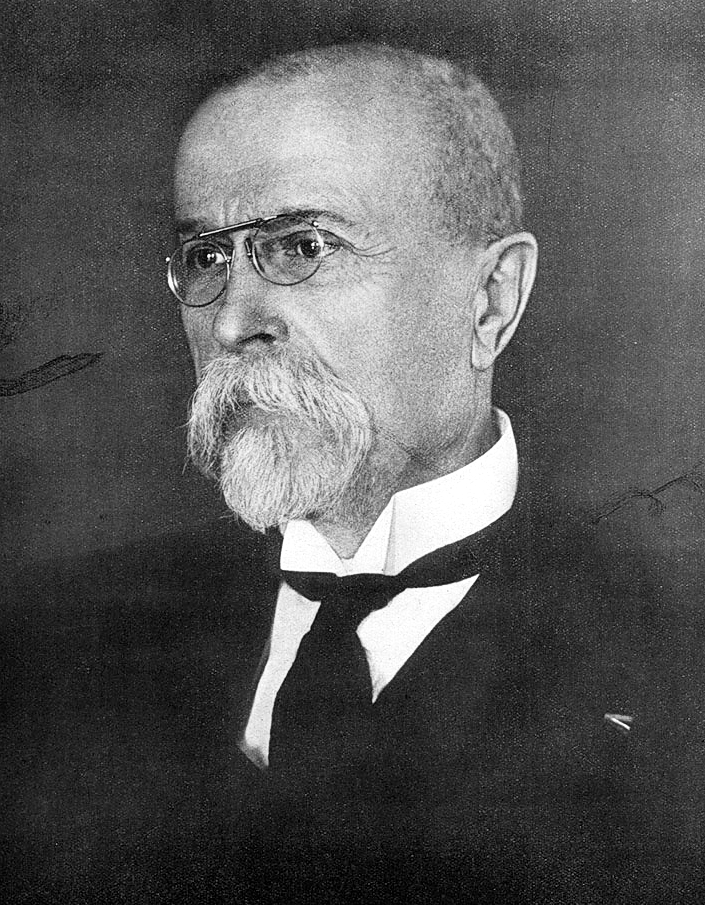

The republic of Czechoslovakia was declared in October 1918. It was a democratic presidential republic. In 1920, its defined territory was not inhabited only by Czechs and Slovaks, it contained significant populations of other nationalities: Germans (22.95%), Hungarians (5.47%) and Ruthenians (3.39%). The

The republic of Czechoslovakia was declared in October 1918. It was a democratic presidential republic. In 1920, its defined territory was not inhabited only by Czechs and Slovaks, it contained significant populations of other nationalities: Germans (22.95%), Hungarians (5.47%) and Ruthenians (3.39%). The

After giving up

After giving up

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power in a coup d'état. Klement Gottwald became the first communist president. He nationalized the country's industry and collectivized its farms to form Sovkhozs inspired by the Soviet model. Czechoslovakia thus became a part of the

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power in a coup d'état. Klement Gottwald became the first communist president. He nationalized the country's industry and collectivized its farms to form Sovkhozs inspired by the Soviet model. Czechoslovakia thus became a part of the

Czech description read Radio Prague online history

- short text

– from Catholic and German point of view

– from Catholic and German point of view

History and archaeology of Czech Republic and central Europe

– Czech published academic journal (in English) {{European history by country Bohemistics

Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

. Many different primitive cultures left their traces throughout the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

, which lasted approximately until 2000 BCE. The most widely known culture present in the Czech lands during the pre-historical era is the Únětice Culture, leaving traces for about five centuries from the end of the Stone Age to the start of the Bronze Age. Celts – who came during the 5th century BCE – are the first people known by name. One of the Celtic tribes were the Boii (plural), who gave the Czech lands their first name ''Boiohaemum'' – Latin for ''the Land of Boii''. Before the beginning of the Common Era the Celts were mostly pushed out by Germanic tribes. The most notable of those tribes were the Marcomanni and traces of their wars with the Roman Empire were left in south Moravia.

After the turbulent times of the Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

, the Czech lands were ultimately settled by the Slavic tribes. The year of 623 marks the formation of the first known state in the Czech lands, when Samo united the local Slavic tribes, defended their lands from the Avars to the east and – few years later – won the battle of Wogastisburg against the Franks invading the Czech lands from the west. The next state appearing in the Czech lands after the dissolution of the Samo's state was probably the Great Moravia. The center of its power lay in the area of Moravia and present-day western Slovakia. In 863, Cyril and Methodius, two scholars from Greece, brought Christianity to the Great Moravia and established the first Slavic script – Glagolitsa

The Glagolitic script (, , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed to have been created in the 9th century by Saints Cyril and Methodius, Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessaloniki, Thessalonica. He and his brothe ...

. The Great Moravia fell during the Magyar invasion at the start of the 10th century.

A new state formed around the tribe of Premyslids, who founded the Duchy of Bohemia. The duchy existed largely within the sphere of influence of the East Franconia and later the Holy Roman Empire. The duchy sided with the Roman Catholic Church during the East-West Schism and in 1212, the duke Ottokar I was granted the hereditary title of king for his service to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. The Přemyslid dynasty died out at the start of the 14th century and was replaced by the Luxembourg dynasty. The most notable of the Luxembourg rulers was the Charles IV, who was elected the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He established the Archbishopric of Prague and Charles University

)

, image_name = Carolinum_Logo.svg

, image_size = 200px

, established =

, type = Public, Ancient

, budget = 8.9 billion CZK

, rector = Milena Králíčková

, faculty = 4,057

, administrative_staff = 4,026

, students = 51,438

, undergr ...

, the first university north of the Alps and east of Paris. The start of the 15th century saw the rise of Proto-Protestantic sentiments in the Czech lands. The execution of Jan Hus sparked the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Cat ...

and the religious split that followed them. The Jagiellon dynasty ascended the Czech throne in 1471. They ruled for half a century before the king Louis Jagiellon died in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

and the empty throne was given to the House of Habsburg.

After the death of the Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the ...

, the religious and political tensions grew, resulting in the Second Defenestration of Prague

The Defenestrations of Prague ( cs, Pražská defenestrace, german: Prager Fenstersturz, la, Defenestratio Pragensis) were three incidents in the history of Bohemia in which people were defenestrated (thrown out of a window). Though already ex ...

, which sparked the Thirty Years War. Many of the Czech nobles supported the Protestant side and were stripped of their properties as a result. Germanization and recatholicisation of the Czech lands followed. The spread of Romanticism during the late 18th century went hand in hand with the movement of the Czech National Revival. After 1848, the leading representatives of the Czech National Revival increased their political efforts to gain more autonomy for the Czech lands within the Habsburg Monarchy.

The start of World War I opened the possibility of gaining full independence and formation of a sovereign state. In the Cleveland Agreement of 1915, the Czech and Slovak representatives declared their goal of creating a common state, based on the right of a people to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

. After the capitulation of Austria-Hungary three years later, the Czechoslovak Republic became a reality. The so-called First Republic lasted only for 20 years, cut short by the advent of the World War II. Following the end of World War II, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took power and Czechoslovakia became a member of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. In August 1968, armies of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia to prevent further attempts at the reformation of the Communist system. At the end of 1989, the Velvet Revolution replaced the Communist regime with a democratic Czech and Slovak Federative Republic

After the Velvet Revolution in late-1989, Czechoslovakia adopted the official short-lived country name Czech and Slovak Federative Republic ( cz, Česká a Slovenská Federativní Republika, sk, Česká a Slovenská Federatívna Republika; ''� ...

. Three years later, Czech and Slovak representatives agreed to the Dissolution of Czechoslovakia

The dissolution of Czechoslovakia ( cs, Rozdělení Československa, sk, Rozdelenie Česko-Slovenska) took effect on December 31, 1992, and was the self-determined split of the federal republic of Czechoslovakia into the independent countries o ...

and the formation of separate states. In 2004, the Czech Republic became a member of the European Union.

Ancient times

Stone Age

A simple chopper – left by the ancestors of the present-day Homo Sapiens – dated to 800,000 BCE was uncovered in Red Hill in Brno. First evidence of human camps was found in Přezletice near Prague and inStránská skála

Stránská skála is a hill and a national nature monument in Brno in the Czech Republic. It refers to a Mid-Pleistocene- Cromerian interglacial most important paleontological site in Central Europe.

Location

Stránská skála is situated in t ...

near Brno which dates to about 200,000 years after that.

Stone tools were found in the Kůlna Cave

The Kůlna Cave is a cave in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It is part of the Moravian Karst. Visit of Kůlna Cave is part of sightseeing tours of the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves.

Geography

The cave is located in the municipal terri ...

in central Moravia, with the estimated age of 120,000 years. More stone tools and the skeletal remains of a Neanderthal man were found at the same site in a 50,000-year-old layer.

Human remains from 45,000 years ago were found in Koněprusy Caves in Zlatý kůň at Beroun District. Human remains from 30,000 years BCE were found in Mladeč caves mammoth tusks with complex engravings (again around 30,000 BCE) were found both in Pavlov Pavlov (or its variant Pavliv) may refer to:

People

*Pavlov (surname) (fem. ''Pavlova''), a common Bulgarian and Russian last name

*Ivan Pavlov, Russian physiologist famous for his experiments in classical conditioning

Places Czech Republic

*Pavlo ...

and Předmostí at Přerov, making south Moravia one of the most important archeological areas in Europe.

The archeological site in Předmostí at Přerov represents the largest accumulation of human remains of the Gravettian culture,

known for creating so-called Venus figurines. One of such figurines is the famous Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000–25,000 BCE) found in

The archeological site in Předmostí at Přerov represents the largest accumulation of human remains of the Gravettian culture,

known for creating so-called Venus figurines. One of such figurines is the famous Venus of Dolní Věstonice (29,000–25,000 BCE) found in Dolní Věstonice

Dolní Věstonice (german: Unterwisternitz) is a municipality and village in Břeclav District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 300 inhabitants. It is known for the eponymous archaeological site.

Geography

Dolní ...

in south Moravia along with many other artifacts from that time. Another Venus figurine is the Venus of Petřkovice, found in what is today Ostrava. Remains of mammoth hunters from 22,000 BCE were also found in the aforementioned Kůlna Cave along with the remains of reindeer hunters and horse hunters, dated to about 10,000 years later. Approximately between 5500 and 4500 BCE, people of the Linear Pottery culture

The Linear Pottery culture (LBK) is a major archaeological horizon of the European Neolithic period, flourishing . Derived from the German ''Linearbandkeramik'', it is also known as the Linear Band Ware, Linear Ware, Linear Ceramics or Inci ...

resided in Czech lands. Their settlement was discovered in Bylany near Kutná hora. Their culture was succeeded by the Lengyel culture, Funnelbeaker culture and Stroke-ornamented ware culture, which coexisted in the Czech Lands during the end of the Stone Age.

Copper Age and Bronze Age

Corded Ware culture in the north and Baden culture in the south were the predominant cultures in the Czech Lands throughout the Copper Age. With the start of the Bronze Age, Únětice culture appeared. This culture got its name from a village near Prague, where the first discovery was made in the 1870s. Many of their burial mounds were uncovered, mostly in central Bohemia. Urnfield culture is a blanket term for various Bronze Age cultures who cremated their dead and buried the urns with their ashes.Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western Europe, Western and Central European Archaeological culture, culture of Late Bronze Age Europe, Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe ...

was the last culture of the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. The key archeological site of the Hallstatt culture in the Czech Lands is the Býčí skála Cave, where a rare bronze statue of a bull was found. Many of these archeological sites were occupied by multiple cultures throughout the ancient times.

Iron Age

The area was settled by the Celtic tribes at the start of the Iron Age. The most prominent tribe in Bohemia were the Boii (plural), who gave the area the name of ''Boiohaemia'' (Latin for ''the land of Boii''), which later turned into Bohemia. Before the start of the 1st century CE, they were pushed out by various Germanic tribes ( Marcomanni,Quadi

The Quadi were a Germanic

*

*

*

people who lived approximately in the area of modern Moravia in the time of the Roman Empire. The only surviving contemporary reports about the Germanic tribe are those of the Romans, whose empire had its bord ...

, Lombards). Traces of Roman army camps were found in south Moravia, most notably near Mušov. The winter camp in Mušov was built to house approximately 20,000 soldiers. The Romans were repeatedly at war with the Marcomanni tribe during the first two centuries CE. Germanic towns are described on the Map of Ptolemaios from the 2nd century, e.g. Coridorgis for Jihlava.

Arrival of the Slavs

The following centuries of what is known as the Great Migration once again changed the ethnic composition of the Czech Lands. In the 6th century, Slavic tribes, displaced by Langobard and Thuringian tribes began to move into the Czech Lands from the east. They fought with neighboring Avars – Turko-Tartar nomads – who seized thePannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

and frequently raided the Slavic lands and even the Frankish Empire.

Samo's realm

In 623 – according to the Chronicle of Fredegar – the Slavic tribes revolted against the oppression of the Avars. During this time, the Frankish merchant Samo allegedly came to the Czech lands with his entourage and joined with the Slavs to defeat the Avars. Thus the Slavs adopted Samo as their ruler. Later Samo and the Slavs came into conflict with the Frankish empire whose ruler Dagobert I wanted to extend his rule to the east. That led to the Battle of Wogastisburg in 631, in which the newly established Realm of Samo successfully defended its autonomy. The realm disintegrated after Samo's death.Medieval times

Great Moravia

The realm of Great Moravia probably was established in the area of today's Moravia and western Slovakia in the 830s. It saw the rise of the first ever Slavic literary culture in the Old Church Slavonic language and the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet dedicated to a Slavic language. Glagolitic was later simplified into the Cyrillic alphabet that is today used in Russia and many countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. Glagolitic was created by

The realm of Great Moravia probably was established in the area of today's Moravia and western Slovakia in the 830s. It saw the rise of the first ever Slavic literary culture in the Old Church Slavonic language and the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet, the first alphabet dedicated to a Slavic language. Glagolitic was later simplified into the Cyrillic alphabet that is today used in Russia and many countries in eastern Europe and central Asia. Glagolitic was created by St. Cyril and St. Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

, who arrived in Great Moravia in 863 from Thessaloniki in Byzantine Empire. They were invited by the king Rastislav who invited them to introduce literacy and a legal system to Great Moravia. His nephew and successor Svatopluk I's diplomacy was oriented more towards Rome. Great Moravia was taken under the protection of the Holy See in 880 and six years after, he expelled the disciples of Methodius after their teacher's death. During his reign, Great Moravia's sphere of influence reached its peak. After his death, the realm was split among his sons and soon after fell to ruin due to infighting and constant Magyar raids during the start of the 10th century.

Duchy of Bohemia

Bořivoj from Levý Hradec was the first known member of the Přemyslid dynasty. In 880, he moved his residence to Prague Castle, which laid the foundation of the city of Prague that emerged centuries later. He was a vassal to the kings of Great Moravia and was baptised during the christanisation of Great Moravia by St. Cyril and St. Methodius. His son Spytihněv I together with the head of another major Bohemian tribe

Bořivoj from Levý Hradec was the first known member of the Přemyslid dynasty. In 880, he moved his residence to Prague Castle, which laid the foundation of the city of Prague that emerged centuries later. He was a vassal to the kings of Great Moravia and was baptised during the christanisation of Great Moravia by St. Cyril and St. Methodius. His son Spytihněv I together with the head of another major Bohemian tribe Witizla

Witizla, who possibly was the founder of Slavnik's dynasty was with Spytihněv I, when Bohemians came to the Roman Empire from Great Moravia. This was the last time in Bohemian history when there were groups of princes like Bohemians, Lemuzes, ...

used the collapse of Great Moravia and in 895 swore allegiance to the East Frankish king Arnulf of Carinthia

Arnulf of Carinthia ( 850 – 8 December 899) was the duke of Carinthia who overthrew his uncle Emperor Charles the Fat to become the Carolingian king of East Francia from 887, the disputed king of Italy from 894 and the disputed emperor from Feb ...

. Spytihněv's nephew Wenceslaus (later proclaimed a saint by the Catholic Church) ruled from 921 and had to submit to the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

king Henry I in order to maintain his ducal authority. He was murdered by his younger brother Boleslaus I. Boleslaus I expanded the Duchy of Bohemia eastwards conquering the lands of Moravia and Silesia and areas around Kraków. He stopped paying tribute to the Saxon king igniting a war which he lost and was forced to recognize Saxon suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

over the Duchy of Bohemia. The Bishopric of Prague

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Prague (Praha) ( cs, Arcidiecéze pražská, la, Archidioecesis Pragensis) is a Metropolitan Catholic archdiocese of the Latin Rite in Bohemia, in the Czech Republic.

The cathedral archiepiscopal see is St. V ...

was founded in 973 during the reign of his son Boleslaus II. The bishopric was subordinated to the Archbishopric of Mainz

The Electorate of Mainz (german: Kurfürstentum Mainz or ', la, Electoratus Moguntinus), previously known in English as Mentz and by its French name Mayence, was one of the most prestigious and influential states of the Holy Roman Empire. In the ...

.

In 1002, during the reign of the duke Vladivoj, the Duchy of Bohemia formally became a part of the Holy Roman Empire. After a period of dynastic infighting, Oldřich took power. His son

In 1002, during the reign of the duke Vladivoj, the Duchy of Bohemia formally became a part of the Holy Roman Empire. After a period of dynastic infighting, Oldřich took power. His son Břetislav I

Bretislav I ( cs, Břetislav I.; 1002/1005 – 10 January 1055), known as the "Bohemian Achilles", of the Přemyslid dynasty, was Duke of Bohemia from 1034 until his death.

Youth

Bretislav was the son of Duke Oldřich and his low-born concubine ...

led many ambitious conquests and later revolted against the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III hoping to gain a full autonomy for the Duchy of Bohemia. Despite the initial success in Battle at Brůdek, he could not withstand the second invasion of the imperial army and ultimately had to renounce all of his conquests save for Moravia and recognize Henry III as his sovereign. After Břetislav's death, the infighting among Přemyslids continued – a consequence of seniority inheritance laws. Among the more notable rulers belong ( Vratislaus II and Vladislaus

Vladislav ( be, Уладзіслаў (', '); pl, Władysław, ; Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, sh-Cyrl, Владислав) is a male given name of Slavic origin. Variations include ''Volodislav'', ''Vlastislav'' and ''Vlaslav''. ...

) who were awarded lifetime titles of kings by the Holy Roman Emperors for their services.

Kingdom of Bohemia

Late Přemyslids

In 1212 Ottokar I was granted a hereditary title of the King of Bohemia by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Thus began the Kingdom of Bohemia, which lasted de iure until the end of World War I. His reign marked the start of the German eastward colonization, which over time significantly altered the language composition of the Czech Lands. His son Wenceslaus I had to deal with the Mongol invasion of Europe at the start of 1240s. He managed to defend Bohemia, but Moravian lands were heavily plundered. When the Duke of Austria Frederick II died in 1246 without male heirs, Wenceslaus I tried to secure the Austrian lands by marrying his eldest son Vladislaus to Frederick's nice Gertrude. This plan failed because of Vladislaus's premature death in the year after. Wenceslaus I then decided for the invasion of Austria and he was successful. His successor, Ottokar II, continued the expansion of the realm. He gained more territory south of Austria and led two crusades against the pagan Old Prussians. He was hoping to gain the Imperial crown, but lost in the 1273 election to Rudolf of Habsburg, the first in a line of Habsburg emperors. Rudolf of Habsburg demanded that Ottokar II returns all of the lands he had acquired south of Bohemia. Ottokar refused and waged two wars against the emperor which ended with his death at the battlefield of Marchfeld in 1278.

The crown was passed to his 6-year-old son Wenceslaus II. Otto V, Margrave of Brandenburg ruled as a regent in his stead, later replaced by

In 1212 Ottokar I was granted a hereditary title of the King of Bohemia by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Thus began the Kingdom of Bohemia, which lasted de iure until the end of World War I. His reign marked the start of the German eastward colonization, which over time significantly altered the language composition of the Czech Lands. His son Wenceslaus I had to deal with the Mongol invasion of Europe at the start of 1240s. He managed to defend Bohemia, but Moravian lands were heavily plundered. When the Duke of Austria Frederick II died in 1246 without male heirs, Wenceslaus I tried to secure the Austrian lands by marrying his eldest son Vladislaus to Frederick's nice Gertrude. This plan failed because of Vladislaus's premature death in the year after. Wenceslaus I then decided for the invasion of Austria and he was successful. His successor, Ottokar II, continued the expansion of the realm. He gained more territory south of Austria and led two crusades against the pagan Old Prussians. He was hoping to gain the Imperial crown, but lost in the 1273 election to Rudolf of Habsburg, the first in a line of Habsburg emperors. Rudolf of Habsburg demanded that Ottokar II returns all of the lands he had acquired south of Bohemia. Ottokar refused and waged two wars against the emperor which ended with his death at the battlefield of Marchfeld in 1278.

The crown was passed to his 6-year-old son Wenceslaus II. Otto V, Margrave of Brandenburg ruled as a regent in his stead, later replaced by Záviš of Falkenštejn

Zawisza or Záviš is a Slavic names, Slavic name and may refer to:

People

* Zawisza Czarny (1379–1428), known as Zawisza the Black, a famous Polish medieval knight and diplomat

* Zawisza Czerwony (died 1433), known as Zawisza the Red, a less ...

, who married Ottokar II's widow. In 1290, Wenceslaus II had Záviš beheaded for alleged treason and began ruling independently. Year later, Przemysł II, the king of Poland, was murdered and Wenceslaus II gained the Polish crown for himself. At the end of the 13th century, huge deposits of silver were found in Kutná Hora

Kutná Hora (; medieval Czech: ''Hory Kutné''; german: Kuttenberg) is a town in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 20,000 inhabitants. The centre of Kutná Hora, including the Sedlec Abbey and its ossuary, was designa ...

, which allowed him to start issuing vast amounts of silver coins called Prague groschen

The Prague groschen ( cz, pražský groš, la, grossi pragenses, german: Prager Groschen, pl, grosz praski) was a groschen-type silver coin that was issued by Wenceslaus II of Bohemia since 1300 in the Kingdom of Bohemia and became very co ...

. In 1301, another neighbouring monarch died – Andrew III of Hungary, the last male member of the Árpád dynasty. Wenceslaus II married his son Wenceslaus III to Andrew III's only daughter and had him crowned in Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

as the King of Hungary. Four years later, Wenceslaus II died – only 33 years old – probably of tuberculosis. Wenceslaus III abandoned his claim to the Hungarian throne, seeing that his rule was only nominal. Władysław the Elbow-high Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

*W ...

challenged Wenceslaus III's rule in Poland and conquered Krakow in 1306. Before Wenceslaus III could start his retaliation campaign, he was murdered in Olomouc by unknown assassins.

House of Luxembourg

Wenceslaus III was the last male member of the main branch of Přemyslids. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg married his son John to Wenceslaus III's sisterElisabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sc ...

and secured for him the Bohemian throne. John of Luxembourg was raised in Paris, did not speak any Czech and was widely unpopular among the Czech nobility. John never stayed long in the Czech lands, he traveled all across Europe and took part in multiple military conflicts. While crusading in Lithuania in 1336, John lost his eyesight due to ophthalmia, which earned him the nickname John the Blind. A year later he took the side of King Philip VI of France

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 ...

in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

and died in 1346 in the Battle of Crécy. His eldest son, Charles IV succeeded him on the Bohemian throne.

Earlier in 1346, the Pope Clement VI declared the Emperor Louis IV a heretic and demanded a new

Earlier in 1346, the Pope Clement VI declared the Emperor Louis IV a heretic and demanded a new Imperial election

The election of a Holy Roman Emperor was generally a two-stage process whereby, from at least the 13th century, the King of the Romans was elected by a small body of the greatest princes of the Empire, the prince-electors. This was then followed ...

. Charles IV was the pope's preferred candidate and he was crowned as the King of Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

in November 1346 in Bonn. Charles had been in charge of the administration of Czech Lands since 1333, due to his father's absence and health indisposition. Soon after his coronation as the King of Bohemia and the King of Romans, he settled in Prague and laid the foundations of the New Town

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

expanding the capitol. In 1348 he founded the University of Prague, the first university north of Alps and east of Paris. He also legally established the Lands of the Bohemian Crown (''Corona regni Bohemiae'' in Latin), meaning the core territories no longer belonged to a king or a dynasty but to the Bohemian monarchy (crown) itself.  In 1355, Charles IV travelled to Rome where he was crowned the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ruled as the Holy Roman Emperor for over 20 years and managed to secure the title of the King of Romans for his eldest son

In 1355, Charles IV travelled to Rome where he was crowned the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He ruled as the Holy Roman Emperor for over 20 years and managed to secure the title of the King of Romans for his eldest son Wenceslaus IV

Wenceslaus IV (also ''Wenceslas''; cs, Václav; german: Wenzel, nicknamed "the Idle"; 26 February 136116 August 1419), also known as Wenceslaus of Luxembourg, was King of Bohemia from 1378 until his death and King of Germany from 1376 until he w ...

.

Wenceslaus IV did not share the governance abilities of his father. In 1393, the torture and murder John of Nepomuk – vicar-general of the archbishop Jan of Jenštejn – sparked a noble rebellion. He was imprisoned for two years at Králův Dvůr and was only released after an intervention from his younger brother Sigismund, who had become the King of Hungary. In 1400, Wenceslaus IV was deposed as the Holy Roman Emperor, mainly due to his failure to address the

Wenceslaus IV did not share the governance abilities of his father. In 1393, the torture and murder John of Nepomuk – vicar-general of the archbishop Jan of Jenštejn – sparked a noble rebellion. He was imprisoned for two years at Králův Dvůr and was only released after an intervention from his younger brother Sigismund, who had become the King of Hungary. In 1400, Wenceslaus IV was deposed as the Holy Roman Emperor, mainly due to his failure to address the Papal Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon b ...

. Two years later, Wenceslaus IV was briefly imprisoned again, this time by his brother Sigismund, who looted Moravia. After the death of Rupert

Rupert may refer to:

People

* Rupert (name), various people known by the given name or surname "Rupert"

Places Canada

*Rupert, Quebec, a village

*Rupert Bay, a large bay located on the south-east shore of James Bay

*Rupert River, Quebec

*Rupert' ...

– who had replaced Wenceslaus as the King of Romans – Wenceslaus IV competed with his brother Sigismund and his cousin Jobst of Moravia for the title of the King of Romans. He ultimately surrendered the title to Sigismund in exchange for keeping Bohemia. In 1414, Sigismund called the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

, which finally resolved the Papal Schism. It also condemned the teaching of Jan Hus, rector of the University of Prague and a popular church reformist. After Jan Hus refused to retract his teachings, he was burnt alive at stake, which prompted the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Cat ...

. The religious military conflicts stopped in 1434 with the battle Battle of Lipany, but the religious tensions continued on. Although Sigismund became the titular King of Bohemia after Wenceslaus IV's death in 1419, it was not until 1436 that he was recognized by the Czech Estates and he died a year after.

House of Habsburg

After Sigismunds's death the title of the King of Bohemia went to his son-in-law Albert from the House of Habsburg, who died shortly after. The claim to the Lands of the Bohemian Crown was passed to his unborn sonLadislaus

Ladislaus ( or according to the case) is a masculine given name of Slavic origin.

It may refer to:

* Ladislaus of Hungary (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus I (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus II (disambiguation)

* Ladislaus III (disambiguation)

* Ladi ...

, who gained the nickname ''Posthumous''. He was raised at the court of his distant relative Emperor Frederick III. Although he was crowned the King of Bohemia in 1453,Krejčíř 1996, p. 45 his regent George of Poděbrady continued to effectively rule Bohemia in his stead. Ladislaus died in Prague after fleeing a rebellion in Hungary, aged only seventeen. Many of his contemporaries suspected he was poisoned, but modern examinations of his skeleton proved he died of acute leukemia. With his death the Albertinian Line of the House of Habsburg ended.

House of Poděbrady

In 1458, the estates of Bohemia elected George of Poděbrady as the new King of Bohemia. He had a difficult role trying to maintain a fragile peace between the Catholic side and the Hussite side, for which he earned the nickname ''King of two peoples''. Despite his efforts, he ultimately did not succeed and in 1465, the catholic nobles formed theUnity of Green Mountain

Unity may refer to:

Buildings

* Unity Building, Oregon, Illinois, US; a historic building

* Unity Building (Chicago), Illinois, US; a skyscraper

* Unity Buildings, Liverpool, UK; two buildings in England

* Unity Chapel, Wyoming, Wisconsin, US; a h ...

and challenged his rule. A year after, he was excommunicated by the new Pope Paul II, which gave a justification for the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus to invade the Czech Lands and start the Bohemian–Hungarian War.

House of Jagiellon

After the king George's death, the war was continued by Vladislaus II from the House of Jagiellon, who was offered the throne of Bohemia by George of Poděbrady himself. After ten years of fighting, the Bohemian-Hungarian War finally ended by signing of the Peace of Olomouc in 1479, in which Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia were ceded to Matthias Corvinus for the rest of his life and both monarchs were allowed to use the title of King of Bohemia. In 1485, Vladislaus II confirmed right of all Bohemian noblemen and commoners to freely adhere either to Hussitism or Catholicism in the Peace of Kutná Hora. After Matthias Corvinus died in 1490, Vladislaus II was elected the King of Hungary and gained all the territories he ceded 30 years earlier. From then on he ruled fromBuda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

. Although Vladislaus II was married three times, he only had two children late in his life: son Louis and daughter Anne. Vladislaus II's two children married two children of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I Maximilian I may refer to:

*Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, reigned 1486/93–1519

*Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria, reigned 1597–1651

*Maximilian I, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1636-1689)

*Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria, reigned 1795� ...

as a result of negotiations at the First Congress of Vienna, tying the House of Jagiellon and the House of Habsburg together.

A year after that, in 1516, Vladislaus II died and his ten-year-old son Louis II became the king of both Hungary and Bohemia. In 1521 he refused to pay the agreed annual tribute to the new Ottoman sultan, Süleyman I

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

and executed his ambassadors. War ensued, Belgrade fell to Ottoman hands the same year. In 1526, Louis II led his forces against Suleiman I in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and those ...

, which ended with a decisive defeat of the Hungarian army and Louis II drowned during his attempted retreat. He left no heirs and so the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were inherited by Ferdinand I Ferdinand I or Fernando I may refer to:

People

* Ferdinand I of León, ''the Great'' (ca. 1000–1065, king from 1037)

* Ferdinand I of Portugal and the Algarve, ''the Handsome'' (1345–1383, king from 1367)

* Ferdinand I of Aragon and Sicily, '' ...

from the House of Habsburg, as was agreed during the First Congress of Vienna.

Part of Habsburg Monarchy

Protestantism

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony, also known as Electoral Saxony (German: or ), was a territory of the Holy Roman Empire from 1356–1806. It was centered around the cities of Dresden, Leipzig and Chemnitz.

In the Golden Bull of 1356, Emperor Charles ...

as part of the Schmalkaldic War, they did so very reluctantly. The next year the Czech estates refused to gather an army again and rebelled, for which they were punished after the Schmalkaldic League decisively lost the Battle of Mühlberg. As a result, Ferdinand I managed to strengthen his position in the Land of the Bohemian Crown, limit city privileges and begin the process of recatholicization by inviting the Jesuit Order to Prague in 1556.  Maximilian II succeeded Ferdinand I in 1562 and – like his father – ruled from Vienna. He approved

Maximilian II succeeded Ferdinand I in 1562 and – like his father – ruled from Vienna. He approved Czech Confession

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

*Czech, ...

(''Confessio Bohemica'' in Latin) – a new document confirming religious freedoms – replacing the older Compacts of Basel The Compacts of Basel, also known as Basel Compacts or ''Compactata'', was an agreement between the Council of Basel and the moderate Hussites (or Utraquists), which was ratified by the Estates of Bohemia and Moravia in Jihlava on 5 July 1436. The a ...

, that did not take non- Ultraquist Protestants into account. He also showed his religious tolerance by reaffirming the Statuta Judaeorum – a document providing legal protection for the Jews in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. His son Rudolf II succeeded him in 1576 and in 1583 he moved the royal court to Prague. Thanks to Rudolf's patronage of art, Prague became a major cultural hub of Europe during his reign. He was a reclusive ruler who preferred his hobbies to the daily affairs of the state. In 1605 Rudolf II was forced by his other family members to cede the rule of Hungary to his younger brother Archduke Matthias Matthias is a name derived from the Greek Ματθαίος, in origin similar to Matthew.

People

Notable people named Matthias include the following:

In religion:

* Saint Matthias, chosen as an apostle in Acts 1:21–26 to replace Judas Iscariot

* ...

following the Bocskai Uprising after the Long Turkish War. The differences of opinions between the two brothers ultimately resulted in Rudolf's imprisonment at the Prague Castle and all effective power was given into the hands of Matthias. After Rudolf II's death in 1612 the royal court moved back to Vienna. Matthias did not have any children – same as his brother Rudolf – and he died six years later, aged 62. Second Defenestration of Prague

The Defenestrations of Prague ( cs, Pražská defenestrace, german: Prager Fenstersturz, la, Defenestratio Pragensis) were three incidents in the history of Bohemia in which people were defenestrated (thrown out of a window). Though already ex ...

in 1618, which sparked the conflict that would become the Thirty Years War. The revolting Bohemian estates then chose Frederick V of Palatinate as their new king and gathered an army in preparation of war. They were joined by Lutheran nobility in Austria. Ferdinand II asked his Spanish relative Philip III for help. Spanish army in the Netherlands made sure forces of Protestant Union could not join the revolt happening in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and in Austria. After dealing with the Austrian rebels, Ferdinand II decisively defeated Frederick V at the Battle of White Mountain, near Prague. Widespread confiscation of property followed, which was then sold to loyal nobles, often of foreign origin. Ferdinand II also had the 27 leaders of the revolt publicly beheaded and strengthened the royal power over the estates. The Lands of the Bohemian Crown and especially Silesia were some of the territories that were hit the hardest by the devastating Thirty Years War. The war continued even after Ferdinand II's death during the reign of Ferdinand III.

Absolutism and National Revival

Late Habsburgs

In 1648, the Thirty Years War finally ended with the

In 1648, the Thirty Years War finally ended with the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

. Ferdinand III continued the recatholicization and centralization policies of his father. After his death in 1657, he was succeeded by his only surviving son Leopold I. During the fourth Austro-Turkish War in 1663 the Turkish army invaded Moravia before being stopped in the Battle of Saint Gotthard. Leopold continued waging wars with Ottomans and France throughout his long rule. He increased corvée to three days a week which caused the Peasant Revolt of 1680

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peas ...

. The infamous Losiny Estate Witch Trials took place between 1678 and 1696 resulting in almost 100 dead. More protests against the increased corvée occurred, but all in vain. In 1705, Leopold I's rule ended and his son Joseph I succeeded him. Joseph I planned to enact many administrative reforms, most of which he did not get the chance to finish, due to his premature death of smallpox. One year before his death he issued letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

ordering that all Romani people in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown had one of their ears cut off. If they returned after being expelled, all Romani men were to be hanged without a trial. Similar letters patents were published in other territories under his rule and led to mass killings of Romani people.David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) p.XI p.36-37 After Joseph I's premature death in 1711, the Austrian throne went to his younger brother Charles VI.

Charles VI had no male heirs and with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 he ensured that all the titles held by him could be inherited by a woman. Charles VI sought the other European powers' approval, which he gained in exchange for various concessions. Regardless, after her father's death, Maria Theresa had to defend her inheritance from the coalition of Prussia, Bavaria, France, Spain, Saxony and Poland in the War of Austrian Succession, that broke out mere weeks after her coronation in 1740. She ultimately managed to defend her title, but paid for it with the loss of Silesia, which became a part of Prussia. That was the ended the unity of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In 1757 during the Seven Years' War, the Prussians invaded Bohemia again and laid siege to Prague, but subsequently lost the

Charles VI had no male heirs and with the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 he ensured that all the titles held by him could be inherited by a woman. Charles VI sought the other European powers' approval, which he gained in exchange for various concessions. Regardless, after her father's death, Maria Theresa had to defend her inheritance from the coalition of Prussia, Bavaria, France, Spain, Saxony and Poland in the War of Austrian Succession, that broke out mere weeks after her coronation in 1740. She ultimately managed to defend her title, but paid for it with the loss of Silesia, which became a part of Prussia. That was the ended the unity of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. In 1757 during the Seven Years' War, the Prussians invaded Bohemia again and laid siege to Prague, but subsequently lost the Battle of Kolín

The Battle of Kolín on 18 June 1757 saw 54,000 Austrians under Count von Daun defeat 34,000 Prussians under Frederick the Great during the Third Silesian War (Seven Years' War). Prussian attempts to turn the Austrian right flank turned into pi ...

and were repelled. Maria Theresa was not able to regain Silesia and the war ended in a draw. She tried to follow the ideas of Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, she established compulsory secular primary schools, but also state censorship of books that were deemed to be against the Catholic religion. Because of her marriage to Francis Stephen of Lorraine, all of her children were considered to be members of a new joint House of Habsburg-Lorraine.

House of Habsburg–Lorraine

After the death of Maria Theresa's husband in 1765, her son Joseph II started to rule with her as a co-ruler and since 1780 as the sole ruler. He enforced many reforms, among the most notable are the abolition of serfdom, Patent of Toleration expanding religious freedom and the dissolution of all monastic orders not involved in education, healthcare or science. As part of his centralization efforts, he also pressed for the expansion of German language to all territories under his rule. Both of his wives died relatively young of smallpox and because he had no sons, he was succeeded by his younger brother Leopold II. Although Leopold II only ruled for two years, he spent several weeks in Prague in 1791 and he let himself be crowned the King of Bohemia.Krejčíř 1996, p. 73 The first Czech Industrial Exhibition was prepared in honor of his visit in Clementinum and the Czech Estates commissioned an opera fromMozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

for the occasion. Leopold II was succeeded by Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe ...

, the first-born of his 12 sons.

In 1805,

In 1805, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's army attacked Austria and defeated the Austrian and Russian army in the decisive Battle of Austerlitz in south Moravia. In the Peace of Pressburg, Francis I lost many of his territories and soon after, the Holy Roman Empire dissolved, replaced by the Confederation of the Rhine. Following the end of Napoleonic Wars, the Congress of Vienna reinstated the Austrian Empire as one of the Great Powers of Europe in 1815. Francis I was a proponent of conservatism and his policies suppressed all of the emerging liberal and nationalist movements in his Empire. He was the first of Austrian monarchs to widely utilize the secret police and he increased censorship. His son Ferdinand I Ferdinand I or Fernando I may refer to:

People

* Ferdinand I of León, ''the Great'' (ca. 1000–1065, king from 1037)

* Ferdinand I of Portugal and the Algarve, ''the Handsome'' (1345–1383, king from 1367)

* Ferdinand I of Aragon and Sicily, '' ...

became the Austrian Emperor after him. Because of his frequent seizures, he was not capable of ruling and the actual executive power was held by the Regent's Council. In 1836, one year after his succession, he was crowned the King of Bohemia under the name of Ferdinand V.  Throughout the 19th century, the nationalist tendencies and movements in the Czech lands known as the Czech National Revival slowly grew, led by activists such as linguists Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, historian and politician František Palacký or writer Božena Němcová and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský. The efforts of the Czech National Revival first peaked during the revolutions of 1848. Ferdinand I was forced to abdicate and his successor was his young nephew Francis Joseph I. When he – after losing the war with Italy in 1859 – also lost the war with Prussia in 1866, the Hungarian representatives forced Francis Joseph I to end his absolutist rule over Hungary in the

Throughout the 19th century, the nationalist tendencies and movements in the Czech lands known as the Czech National Revival slowly grew, led by activists such as linguists Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann, historian and politician František Palacký or writer Božena Němcová and journalist Karel Havlíček Borovský. The efforts of the Czech National Revival first peaked during the revolutions of 1848. Ferdinand I was forced to abdicate and his successor was his young nephew Francis Joseph I. When he – after losing the war with Italy in 1859 – also lost the war with Prussia in 1866, the Hungarian representatives forced Francis Joseph I to end his absolutist rule over Hungary in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (german: Ausgleich, hu, Kiegyezés) established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary ...

. The Czech representatives who hoped for a similar increase in autonomy were left out and the Czech lands remained firmly under the control of Austria.

Austria-Hungary

The newly formed Real union of Austria-Hungary lasted for the next half-a-century. The policies suppressing the National Revival in the Czech lands under the Austrian government continued, as well as the suppression of the Slovak National Revival under the Hungarian government. The end of the 19th century also was a time of a demographic boom and a rapid urbanization. Population in centers of industry doubled or tripled within a few decades. At the start of the 20th century, Austria's unilateral annexation of Bosnia in 1908 caused the Bosnian Crisis and prompted the eventual assassination of

The newly formed Real union of Austria-Hungary lasted for the next half-a-century. The policies suppressing the National Revival in the Czech lands under the Austrian government continued, as well as the suppression of the Slovak National Revival under the Hungarian government. The end of the 19th century also was a time of a demographic boom and a rapid urbanization. Population in centers of industry doubled or tripled within a few decades. At the start of the 20th century, Austria's unilateral annexation of Bosnia in 1908 caused the Bosnian Crisis and prompted the eventual assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria

Archduke Franz Ferdinand Carl Ludwig Joseph Maria of Austria, (18 December 1863 – 28 June 1914) was the heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary. His assassination in Sarajevo was the most immediate cause of World War I.

F ...

, sparking the World War I in 1914. Many of the Czech nationalists saw the war as an opportunity for gaining full independence from the Austria-Hungary. Desertion among the Czech conscripts was commonplace and Czechoslovak Legions were formed to fight for the side of Entente Powers. In the Cleveland Agreement of 1915

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. m ...

, the Czech and Slovak representatives declared their goal of creating a common state, based on the right of a people to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

. When the World War I ended in 1918, the Kingdom of Bohemia officially ceased to exist and a new democratic republic of Czechoslovakia took its place.

Modern times

Czechoslovakia

The republic of Czechoslovakia was declared in October 1918. It was a democratic presidential republic. In 1920, its defined territory was not inhabited only by Czechs and Slovaks, it contained significant populations of other nationalities: Germans (22.95%), Hungarians (5.47%) and Ruthenians (3.39%). The

The republic of Czechoslovakia was declared in October 1918. It was a democratic presidential republic. In 1920, its defined territory was not inhabited only by Czechs and Slovaks, it contained significant populations of other nationalities: Germans (22.95%), Hungarians (5.47%) and Ruthenians (3.39%). The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

starting at the end of 1920's together with the rise of the National Socialist Party in neighbouring Germany during the 1930s caused increasing tensions between the different nationalist groups in Czechoslovakia. In foreign relations the newly established republic relied heavily on its western allies of Great Britain and France. That proved to be a mistake as in 1938, both allied countries agreed to Hitler's demands and co-signed the Munich Treaty

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, stripping the Czechoslovakia of its borderlands, leaving it indefensible.

German protectorate

After giving up

After giving up Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, the Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, Druhá československá republika, sk, Druhá česko-slovenská republika) existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was composed of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and ...

lasted only half-a-year before its full dismemberment before the start of World War II. The Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

declared its independence from Czechoslovakia and became Germany's client state, while two days later the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed. During the World War II – given the high level of industrialization of pre-war Czechoslovakia – the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia served as a major hub of military production for Germany. The oppression of ethnic Czechs increased after the assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

of Reinhard Heydrich by members of the Czech resistance in 1942. After Germany's defeat in 1945, the vast majority of ethnic Germans were forcefully deported from Czechoslovakia.

Rule of the Communist Party

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power in a coup d'état. Klement Gottwald became the first communist president. He nationalized the country's industry and collectivized its farms to form Sovkhozs inspired by the Soviet model. Czechoslovakia thus became a part of the

In February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power in a coup d'état. Klement Gottwald became the first communist president. He nationalized the country's industry and collectivized its farms to form Sovkhozs inspired by the Soviet model. Czechoslovakia thus became a part of the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

. Attempts at a reformation of the political system during the Prague Spring

The Prague Spring ( cs, Pražské jaro, sk, Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization and mass protest in

the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Sec ...

of 1968 were ended by the invasion of armies of the Warsaw Pact. The Czechoslovakia remained under the rule of the Communist Party until the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

Post Cold War

One of the leaders of the dissent, Václav Havel became the first president of the democratic Czechoslovakia. Slovakia's demands for sovereignty were fulfilled at the end of 1992, when the representatives of Czechs and Slovaks agreed to split the Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. The official start of the current Czech Republic was set on the 1st January 1993. The Czech Republic became a member of NATO in 1999, and the European Union in May 2004.See also

*Lech, Czech and Rus

Lech, Czech and Rus' (, ) refers to a founding legend of three Slavic brothers who founded three Slavic peoples: the Poles (or Lechites), the Czechs, and the Rus'. The three legendary brothers appear together in the ''Wielkopolska Chronicle'', ...

* Czech Silesia

* Politics of the Czech Republic

* Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

Lists:

* List of presidents of Czechoslovakia

* List of prime ministers of Czechoslovakia

* List of presidents of the Czech Republic

* List of prime ministers of the Czech Republic

References

Further reading

* Hochman, Jiří. ''Historical dictionary of the Czech State'' (1998) * Heimann, Mary. 'Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed' 2009 * Lukes, Igor. 'Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler', Oxford University Press 1996, * Skilling Gordon. 'Czechoslovakia's Interrupted Revolution', Princeton University Press 1976,External links

Czech description read Radio Prague online history

- short text

– from Catholic and German point of view

– from Catholic and German point of view

History and archaeology of Czech Republic and central Europe

– Czech published academic journal (in English) {{European history by country Bohemistics