History Of Chess on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in

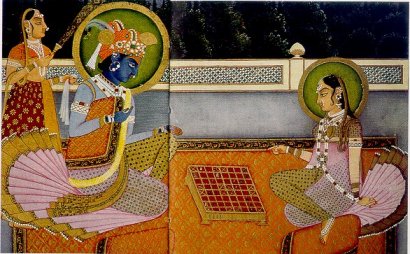

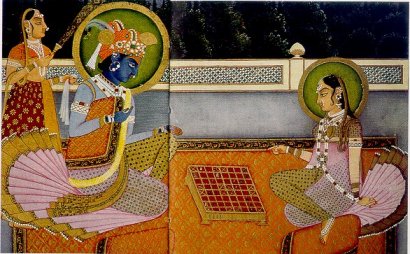

The earliest precursor of modern chess is a game called chaturanga, which flourished in India by the 6th century, and is the earliest known game to have two essential features found in all later chess variations—different pieces having different powers (which was not the case with

The earliest precursor of modern chess is a game called chaturanga, which flourished in India by the 6th century, and is the earliest known game to have two essential features found in all later chess variations—different pieces having different powers (which was not the case with

Image:Shatranj.jpg,

The Karnamak-i Ardeshir-i Papakan, a Pahlavi epical treatise about the founder of the

Over the centuries, features of European chess (e.g. the modern moves of queen and bishop, and castling) found their way via trade into Islamic areas. Murray's sources found the old moves of queen and bishop still current in

Over the centuries, features of European chess (e.g. the modern moves of queen and bishop, and castling) found their way via trade into Islamic areas. Murray's sources found the old moves of queen and bishop still current in

Image:KnightsTemplarPlayingChess1283.jpg,

The queen and bishop remained relatively weak until between 1475 AD and 1500 AD, in

The queen and bishop remained relatively weak until between 1475 AD and 1500 AD, in

Valencia Spain: The Cradle of European Chess

. Retrieved 10 December 2006 with the exception of the rules about stalemate, which were finalized in the early 19th century. The modern move of the queen may have started as an extension of its older ability to once move two squares with jump, diagonally or straight.

Image:EnxadrismoGravuras.003.jpg, A

Writings on the theory of how to play chess began to appear in the 15th century. The oldest surviving printed chess book, ''Repetición de Amores y Arte de Ajedrez'' (''Repetition of Love and the Art of Playing Chess'') by

In 1861 the first time limits, using sandglasses, were employed in a tournament match at

In 1861 the first time limits, using sandglasses, were employed in a tournament match at

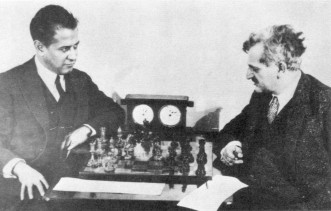

The first modern chess tournament was held in London in 1851 and won, surprisingly, by German

The first modern chess tournament was held in London in 1851 and won, surprisingly, by German  Deeper insight into the nature of chess came with two younger players.

Deeper insight into the nature of chess came with two younger players.  It took a prodigy from

It took a prodigy from

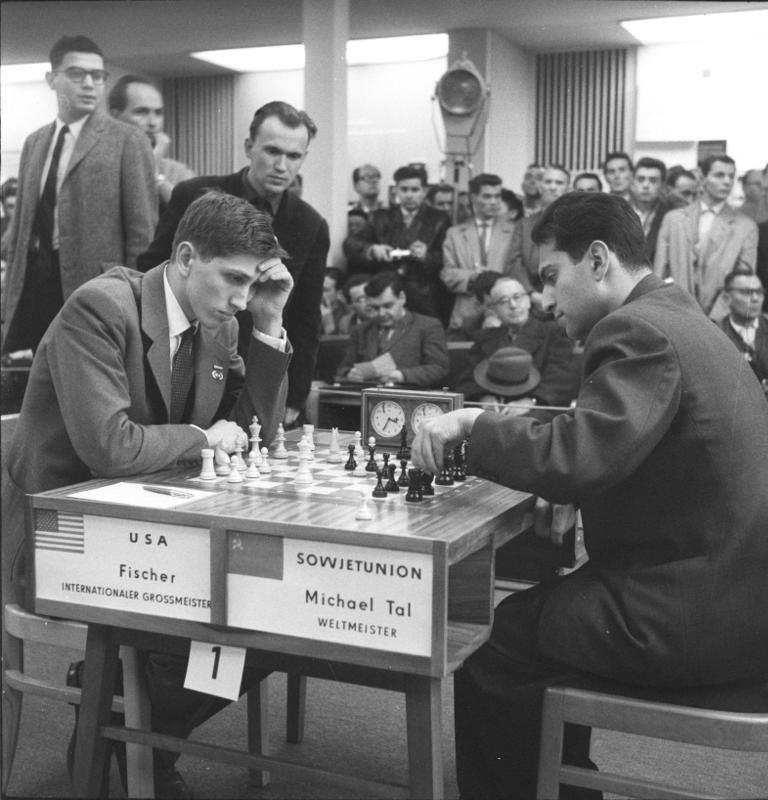

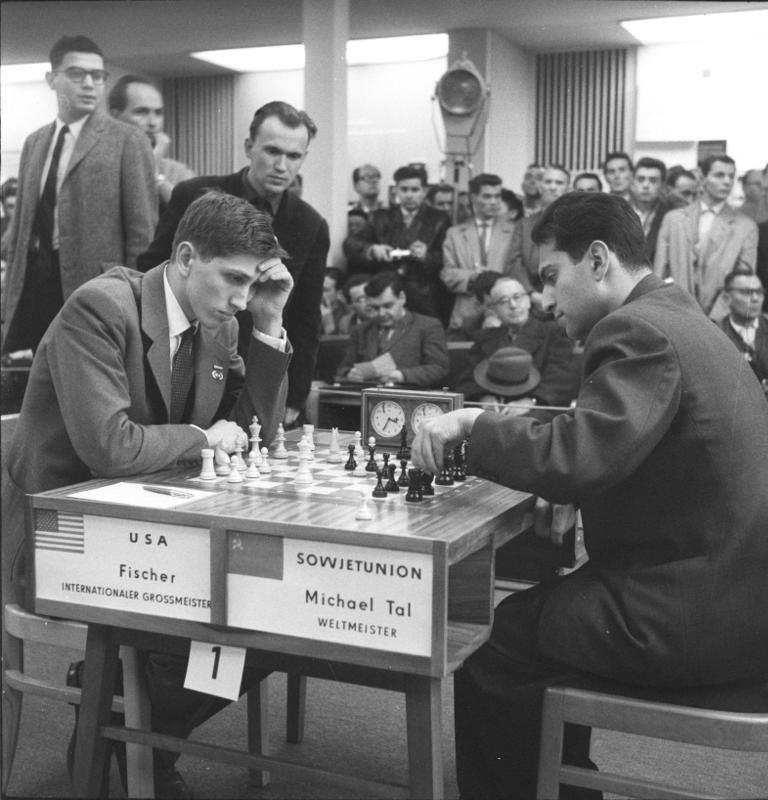

After the death of Alekhine, a new World Champion was sought in a tournament of elite players ruled by FIDE, who have controlled the title since then, with a sole interruption. The winner of the 1948 tournament, Russian

After the death of Alekhine, a new World Champion was sought in a tournament of elite players ruled by FIDE, who have controlled the title since then, with a sole interruption. The winner of the 1948 tournament, Russian  The next championship saw the first non-Soviet challenger since

The next championship saw the first non-Soviet challenger since

''The History of Chess: From the Time of the Early Invention of the Game in India Till the Period of Its Establishment in Western and Central Europe''

London: W. H. Allen & Co. * * * * * Reprint: (1996) * * * * * * * Leibs, Andrew (2004). ''Sports and Games of the Renaissance''. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. * * * * Musser Golladay, Sonja

"''Los Libros de acedrex dados e tablas'': Historical, Artistic and Metaphysical Dimensions of Alfonso X's ''Book of Games''"

(PhD diss., University of Arizona, 2007) * * * * Saidy, Anthony. ''The battle of chess ideas'' (Batsford, 1972); scholarly history; ''The March of Chess Ideas: How the Century's Greatest Players Have Waged the War Over Chess Strategy'' (1994) * * * * * Journals * Anand, Viswanathan

"The Indian Defense"

PDF version

* *

Origin and history of Chess, Xiangqi, Shogi and more

Initiative group Koenigstein

Alfonso X y el ajedrez - Alfonso X and Chess

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Chess

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in

The history of chess can be traced back nearly 1500 years to its earliest known predecessor, called chaturanga, in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

; its prehistory is the subject of speculation. From India it spread to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Following the Arab invasion and conquest of Persia, chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

was taken up by the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

and subsequently spread to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and the rest of Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

. The game evolved roughly into its current form by about 1500 CE.

"Romantic chess

Romantic chess is a style of chess popular in the 18th century until the 1880s. This style of chess emphasizes quick, tactical maneuvers rather than long-term strategic planning. Romantic players consider winning to be secondary to winning with sty ...

" was the predominant playing style from the late 18th century to the 1880s. Chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

games of this period emphasized quick, tactical maneuvers rather than long-term strategic planning. The Romantic era of play was followed by the Scientific, Hypermodern, and New Dynamism eras. In the second half of the 19th century, modern chess tournament

A chess tournament is a series of chess games played competitively to determine a winning individual or team. Since the first international chess tournament in London 1851 chess tournament, London, 1851, chess tournaments have become the standard ...

play began, and the first official World Chess Championship

The World Chess Championship is played to determine the world champion in chess. The current world champion is Magnus Carlsen of Norway, who has held the title since 2013.

The first event recognized as a world championship was the 1886 match ...

was held in 1886. The 20th century saw great leaps forward in chess theory and the establishment of the World Chess Federation

The International Chess Federation or World Chess Federation, commonly referred to by its French acronym FIDE ( Fédération Internationale des Échecs), is an international organization based in Switzerland that connects the various national c ...

. In 1997, an IBM supercomputer beat Garry Kasparov

Garry Kimovich Kasparov (born 13 April 1963) is a Russian chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion, writer, political activist and commentator. His peak rating of 2851, achieved in 1999, was the highest recorded until being surpassed by ...

, the then world chess champion, in the famous Deep Blue versus Garry Kasparov

Deep Blue versus Garry Kasparov was a pair of six-game chess matches between the world chess champion Garry Kasparov and an IBM supercomputer called Deep Blue. The first match was played in Philadelphia in 1996 and won by Kasparov by 4–2. ...

match, ushering the game into an era of computer domination. Since then, computer analysis – which originated in the 1970s with the first programmed chess games on the market – has contributed to much of the development in chess theory and has become an important part of preparation in professional human chess. Later developments in the 21st century made the use of computer analysis far surpassing the ability of any human player accessible to the public. Online gaming, which first appeared in the mid-1990s, also became popular in the 21st century.

Origin

Precursors tochess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

originated in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. There, its early form in the 7th century CE was known as '' chaturaṅga'' (), which translates to "four divisions (of the military)": infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

, cavalry, elephantry

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elephan ...

, and chariotry. These forms are represented by the pieces that would evolve into the modern pawn

Pawn most often refers to:

* Pawn (chess), the weakest and most numerous piece in the game

* Pawnbroker or pawnshop, a business that provides loans by taking personal property as collateral

Pawn may also refer to:

Places

* Pawn, Oregon, an his ...

, knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

, bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is c ...

, and rook

Rook (''Corvus frugilegus'') is a bird of the corvid family. Rook or rooks may also refer to:

Games

*Rook (chess), a piece in chess

*Rook (card game), a trick-taking card game

Military

* Sukhoi Su-25 or Rook, a close air support aircraft

* USS ...

, respectively.

Chess was introduced to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

from India and became a part of the princely or courtly education of Persian nobility. Around 600 CE in Sassanid Persia

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

, the name for the game became ''chatrang'' ( fa, چترنگ), which subsequently evolved to ''shatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

'' ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج) after the conquest of Persia by the Rashidun Caliphate, due to the lack of native ''ch'' and ''ng'' sounds in the Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

.Shenk, David. "The Immortal Game." Doubleday, 2006. The rules were developed further during this time; players started calling "Shāh!" (Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

for "King!") when attacking the opponent's king, and "Shāh Māt!" (Persian for "the king is helpless" – see checkmate) when the king was attacked and could not escape from attack. These exclamations persisted in chess as it traveled to other lands.

The game was taken up by the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

after the early Arab Muslims conquered the Sassanid Empire, with the pieces largely keeping their Persian names. The Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

rendered the Persian term "''shatranj''" as ''shaṭerej'', which gave rise to the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

', ' and '; in Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

it became , and in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

(ζατρίκιον), but in the rest of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

it was replaced by versions of the Persian ''shāh'' ("king"). Thus, the game came to be called or in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, in Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, in Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

, in French (Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

), in Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, in German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, in Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, in Latvian, in Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

, in Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

, in Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

, in Finnish

Finnish may refer to:

* Something or someone from, or related to Finland

* Culture of Finland

* Finnish people or Finns, the primary ethnic group in Finland

* Finnish language, the national language of the Finnish people

* Finnish cuisine

See also ...

, in South Slavic languages, in Hungarian and in Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

; there are two theories about why this change happened:

# From the exclamation "check" or "checkmate" as it was pronounced in various languages.

# From the first chessmen known of in Western Europe (except Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

and Greece) being ornamental chess kings brought in as curios by Muslim traders.

The Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

call the game ''shatar'', and in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

it is called ''senterej'', both evidently derived from ''shatranj''.

Chess spread directly from the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

to Russia, where chess became known as шахматы (, literally "checkmates", a plurale tantum

A ''plurale tantum'' (Latin for "plural only"; ) is a noun that appears only in the plural form and does not have a singular variant for referring to a single object. In a less strict usage of the term, it can also refer to nouns whose singular fo ...

).

The game reached Western Europe and Russia by at least three routes, the earliest being in the 9th century. By the year 1000 it had spread throughout Europe.Hooper and Whyld, 144-45 (first edition) Introduced into the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

by the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

in the 10th century, it was described in a famous 13th-century Spanish manuscript covering ''shatranj'', backgammon

Backgammon is a two-player board game played with counters and dice on tables boards. It is the most widespread Western member of the large family of tables games, whose ancestors date back nearly 5,000 years to the regions of Mesopotamia and Pe ...

and dice

Dice (singular die or dice) are small, throwable objects with marked sides that can rest in multiple positions. They are used for generating random values, commonly as part of tabletop games, including dice games, board games, role-playing g ...

named the ''Libro de los juegos

The ''Libro de los juegos'' (Spanish: "Book of games"), or ''Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas'' ("Book of chess, dice and tables", in Old Spanish), was a Spanish language, Spanish translation of Arabic texts on chess, dice and Tables games, tabl ...

'', which is the earliest European

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

treatise on chess as well as being the oldest document on European tables games

Tables games are a class of board game that includes backgammon and which are played on a tables board, typically with two rows of 12 vertical markings called points. Players roll dice to determine the movement of pieces. Tables games are among ...

.

Chess spread throughout the world and many variants of the game soon began taking shape. Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

pilgrims, Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

traders and others carried it to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

where it was transformed and assimilated into a game often played on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares. ''Chaturanga'' reached Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

through Persia, the Byzantine empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the expanding Arabian empire

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

. Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

carried chess to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

by the 10th century.

The game was developed extensively in Europe. By the late 15th century, it had survived a series of prohibitions and Christian Church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

sanctions to almost take the shape of the modern game. Modern history

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is applie ...

saw reliable reference works, competitive chess tournaments, and exciting new variants. These factors added to the game's popularity, further bolstered by reliable timing mechanisms (first introduced in 1861), effective rules, and charismatic players.

India

The earliest precursor of modern chess is a game called chaturanga, which flourished in India by the 6th century, and is the earliest known game to have two essential features found in all later chess variations—different pieces having different powers (which was not the case with

The earliest precursor of modern chess is a game called chaturanga, which flourished in India by the 6th century, and is the earliest known game to have two essential features found in all later chess variations—different pieces having different powers (which was not the case with checkers

Checkers (American English), also known as draughts (; British English), is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve diagonal moves of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Checkers ...

and Go), and victory depending on the fate of one piece, the king of modern chess. A common theory is that India's development of the board, and chess, was likely due to India's mathematical enlightenment involving the creation of the number zero. Other game pieces (speculatively called "chess pieces") uncovered in archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

findings are considered as coming from other, distantly related board games, which may have had boards of 100 squares or more.Chess: Ancient precursors and related games (Encyclopædia Britannica 2002)

Chess was designed for an ''ashtāpada

Ashtāpada ( sa, अष्टापद) or Ashtapadi is an Indian board game which predates chess and was mentioned on the list of games that Gautama Buddha would not play. Chaturanga, which could be played on the same , appeared sometime around ...

'' (Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

for "having eight feet", i.e. an 8×8 squared board), which may have been used earlier for a backgammon

Backgammon is a two-player board game played with counters and dice on tables boards. It is the most widespread Western member of the large family of tables games, whose ancestors date back nearly 5,000 years to the regions of Mesopotamia and Pe ...

-type race game (perhaps related to a dice-driven race game still played in south India where the track starts at the middle of a side and spirals into the center). Ashtāpada, the uncheckered 8×8 board served as the main board for playing chaturanga.Wilkins 2002: 46 Other Indian boards included the 10×10 ''Dasapada'' and the 9×9 ''Saturankam''. Traditional Indian chessboards often have X markings on some or all of squares a1 a4 a5 a8 d1 d4 d5 d8 e1 e4 e5 e8 h1 h4 h5 h8: these may have been "safe squares" where capturing was not allowed in a dice-driven backgammon-type race game played on the ashtāpada

Ashtāpada ( sa, अष्टापद) or Ashtapadi is an Indian board game which predates chess and was mentioned on the list of games that Gautama Buddha would not play. Chaturanga, which could be played on the same , appeared sometime around ...

before chess was invented.Murray (1913), p. 42

The Cox-Forbes theory, proposed in the late 18th century by Hiram Cox Captain Hiram Cox (1760–1799) was a British diplomat, serving in Bengal and Burma in the 18th century. The city of Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh is named after him.

Biography

As an officer of the East India Company, Captain Cox was appointed Supe ...

, and later developed by Duncan Forbes, asserted that the four-handed game chaturaji

Chaturaji (meaning "four kings") is a four-player chess-like game. It was first described in detail c. 1030 by Al-Biruni in his book ''India''. Originally, this was a game of chance: the pieces to be moved were decided by rolling two dice. A ...

was the original form of chaturanga. The theory is no longer considered tenable.Hooper 1992: 74

In Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, the word ''chaturaṅga'' literally means "having four limbs (or parts)" and in epic poetry

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

often means "army" (the four parts are elephants, chariots, horsemen, foot soldiers).Meri 2005: 148 The name came from a battle formation mentioned in the Indian epic Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the ''Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kuruk ...

. The game chaturanga was a battle-simulation game which rendered Indian military strategy of the time.Kulke 2004: 9

Some people formerly played chess using a die

Die, as a verb, refers to death, the cessation of life.

Die may also refer to:

Games

* Die, singular of dice, small throwable objects used for producing random numbers

Manufacturing

* Die (integrated circuit), a rectangular piece of a semicondu ...

to decide which piece to move. There was an unproven theory that chess started as this dice-chess and that the gambling and dice aspects of the game were removed because of Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

religious objections.Wilkins 2002: 48

Scholars in areas to which the game subsequently spread, for example the Arab Abu al-Hasan 'Alī al-Mas'ūdī

Al-Mas'udi ( ar, أَبُو ٱلْحَسَن عَلِيّ ٱبْن ٱلْحُسَيْن ٱبْن عَلِيّ ٱلْمَسْعُودِيّ, '; –956) was an Arab historian, geographer and traveler. He is sometimes referred to as the "Herodotus ...

, detailed the Indian use of chess as a tool for military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired strategic goals. Derived from the Greek word '' strategos'', the term strategy, when it appeared in use during the 18th century, was seen in its narrow s ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three el ...

and even its vague association with astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

.Wilkinson 1943 Mas'ūdī notes that ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

in India was chiefly used for the production of chess and backgammon

Backgammon is a two-player board game played with counters and dice on tables boards. It is the most widespread Western member of the large family of tables games, whose ancestors date back nearly 5,000 years to the regions of Mesopotamia and Pe ...

pieces, and asserts that the game was introduced to Persia from India, along with the book '' Kelileh va Demneh,'' during the reign of emperor Nushirwan.

In some variants, a win was by checkmate, or by stalemate

Stalemate is a situation in the game of chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the inferior ...

, or by "bare king" (taking all of an opponent's pieces except the king).

In some parts of India the pieces in the places of the rook, knight and bishop were renamed by words meaning (in this order) Boat, Horse, and Elephant, or Elephant, Horse, and Camel, but keeping the same moves.

In early chess the moves of the pieces were:

Two Arab travelers each recorded a severe Indian chess rule against stalemate

Stalemate is a situation in the game of chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the inferior ...

:

*A stalemated player thereby at once wins.

*A stalemated king can take one of the enemy pieces that would check the king if the king moves.

Iran (Persia)

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

ian shatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

set, glazed fritware

Fritware, also known as stone-paste, is a type of pottery in which frit (ground glass) is added to clay to reduce its fusion temperature. The mixture may include quartz or other siliceous material. An organic compound such as gum or glue may ...

, 12th century, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 F ...

Image:Persianmss14thCambassadorfromIndiabroughtchesstoPersianCourt.jpg, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n manuscript from the 14th century describing how an ambassador from India brought chess to the Persian court

Image:Shams ud-Din Tabriz 1502-1504 BNF Paris.jpg, Shams-e-Tabrīzī as portrayed in a 1500 painting in a page of a copy of Rumi

Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī ( fa, جلالالدین محمد رومی), also known as Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Balkhī (), Mevlânâ/Mawlānā ( fa, مولانا, lit= our master) and Mevlevî/Mawlawī ( fa, مولوی, lit= my ma ...

's poem dedicated to Shams

File:The Chess Game.jpg, Chess game between Tha'ālibī and Bakhazari, 1896 painting by Ludwig Deutsch

Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

, mentions the game of chatrang

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as ...

as one of the accomplishments of the legendary hero, Ardashir I

Ardashir I (Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭥𐭲𐭧𐭱𐭲𐭥, Modern Persian: , '), also known as Ardashir the Unifier (180–242 AD), was the founder of the Sasanian Empire. He was also Ardashir V of the Kings of Persis, until he founded the new emp ...

, founder of the Empire.Bell 1979: 57 The oldest recorded game in chess history is a 10th-century game played between a historian from Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

and a pupil.Chess: Introduction to Europe (Encyclopædia Britannica 2007)

A manuscript explaining the rules of the game called "Matikan-i-chatrang" (the book of chess) in Middle Persian

Middle Persian or Pahlavi, also known by its endonym Pārsīk or Pārsīg () in its later form, is a Western Middle Iranian language which became the literary language of the Sasanian Empire. For some time after the Sasanian collapse, Middle Per ...

or Pahlavi still exists.

In the 11th-century ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,00 ...

'', Ferdowsi

Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi ( fa, ; 940 – 1019/1025 CE), also Firdawsi or Ferdowsi (), was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a sin ...

describes a Raja

''Raja'' (; from , IAST ') is a royal title used for South Asian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in South Asia and Southeast Asia, being attested f ...

visiting from India who re-enacts the past battles on the chessboard. A translation in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, based on the manuscripts in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, is given below:

:One day an ambassador from the king of Hind A hind is a female deer, especially a red deer.

Places

* Hind (Sasanian province, 262-484)

* Hind and al-Hind, a Persian and Arabic name for the Indian subcontinent

* Hind (crater), a lunar impact crater

* 1897 Hind, an asteroid

Military

...

arrived at the Persian court of Chosroes, and after an oriental exchange of courtesies, the ambassador produced rich presents from his sovereign and amongst them was an elaborate board with curiously carved pieces of ebony and ivory. He then issued a challenge:

:"Oh great king, fetch your wise men and let them solve the mysteries of this game. If they succeed my master the king of Hind will pay tribute as an overlord, but if they fail it will be proof that the Persians are of lower intellect and we shall demand tribute from Iran."

:The courtiers were shown the board, and after a day and a night in deep thought one of them, Bozorgmehr

Bozorgmehr-e Bokhtagan (Middle Persian: ''Wuzurgmihr ī Bōkhtagān''), also known as Burzmihr, Dadmihr and Dadburzmihr, was an Iranian sage and dignitary from the Karen family, who served as minister ('' wuzurg framadār'') of the Sasanian king ...

, solved the mystery and was richly rewarded by his delighted sovereign.

The ''Shahnameh'' goes on to offer an apocryphal account of the origins of the game of chess in the story of Talhand and Gav, two half-brothers who vie for the throne of Hind (India). They meet in battle and Talhand dies on his elephant without a wound. Believing that Gav had killed Talhand, their mother is distraught. Gav tells his mother that Talhand did not die by the hands of him or his men, but she does not understand how this could be. So the sages of the court invent the game of chess, detailing the pieces and how they move, to show the mother of the princes how the battle unfolded and how Talhand died of fatigue when surrounded by his enemies. The poem uses the Persian term "Shāh māt" (check mate) to describe the fate of Talhand.

The philosopher and theologian Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polymat ...

mentions chess in ''The Alchemy of Happiness

)

, translator = Muhammad Mustafa an-Nawali, Claud Field, Jay Crook

, image = Alchemy of Happiness.png

, caption = Cover of a 1308 Persian copy held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

, author = Al ...

'' (c. 1100). He uses it as a specific example of a habit that may cloud a person's good disposition:

The appearance of the chess pieces

A chess piece, or chessman, is a game piece that is placed on a chessboard to play the game of chess. It can be either white or black, and it can be one of six types: king, queen, rook, bishop, knight, or pawn.

Chess sets generally come with s ...

had altered greatly since the times of chaturanga, with ornate pieces and chess pieces depicting animals giving way to abstract shapes. This is because of a Muslim ban on the game's lifelike pieces, as they were said to have been too like idols. The Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the mai ...

sets of later centuries followed a pattern which assigned names and abstract shapes to the chess pieces, as Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

forbids depiction of animals and human beings in art. These pieces were usually made of simple clay and carved stone.

East Asia

China

As a strategy board game played in China, chess is believed to have been derived from the Indian chaturanga. Chaturanga was transformed into the gamexiangqi

''Xiangqi'' (; ), also called Chinese chess or elephant chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is the most popular board game in China. ''Xiangqi'' is in the same family of games as '' shogi'', '' janggi'', Western chess, '' ch ...

where the pieces are placed on the intersection of the lines of the board rather than within the squares.Bell 1979, V.I p.66 The object of the Chinese variation is similar to chaturanga, i.e. to render helpless the opponent's king, known as "general" on one side and "governor" on the other. Chinese chess also borrows elements from the game of Go, which was played in China since at least the 6th century BC. Owing to the influence of Go, Chinese chess is played on the intersections of the lines on the board, rather than in the squares. The game of Xianqi is also unique in that the middle rank represents a river, and is not divided into squares. Chinese chess pieces are usually flat and resemble those used in checkers

Checkers (American English), also known as draughts (; British English), is a group of strategy board games for two players which involve diagonal moves of uniform game pieces and mandatory captures by jumping over opponent pieces. Checkers ...

, with pieces differentiated by writing their names on the flat surface.

An alternative origin theory contends that chess arose from xiangqi

''Xiangqi'' (; ), also called Chinese chess or elephant chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is the most popular board game in China. ''Xiangqi'' is in the same family of games as '' shogi'', '' janggi'', Western chess, '' ch ...

or a predecessor thereof, existing in China since the 3rd century BC.Li 1998 David H. Li, a translator of ancient Chinese texts, hypothesizes that general Han Xin

Han Xin (; 231/230–196 BC) was a Chinese military general and politician who served Liu Bang during the Chu–Han Contention and contributed greatly to the founding of the Han dynasty. Han Xin was named as one of the "Three Heroes of the ear ...

drew on the earlier game of Liubo

''Liubo'' () was an ancient Chinese board game played by two players. The rules have largely been lost, but it is believed that each player had six game pieces that were moved around the points of a square game board that had a distinctive, sym ...

to develop an early form of Chinese chess in the winter of 204–203 BC. The German chess historian Peter Banaschak, however, points out that Li's main hypothesis "is based on virtually nothing." He notes that the "Xuanguai lu", authored by the Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

minister Niu Sengru (779–847), remains the first real source on the Chinese chess variant xiangqi.

Japan

A prominent variant of chess in East Asia is the game ofshogi

, also known as Japanese chess, is a strategy board game for two players. It is one of the most popular board games in Japan and is in the same family of games as Western chess, ''chaturanga, Xiangqi'', Indian chess, and '' janggi''. ''Shōgi'' ...

, transmitted from India to China and Korea before finally reaching Japan. The three distinguishing features of shogi are:

# The captured pieces may be reused by the captor and played as a part of the captor's forces.

# Pawns capture as they move, one square straight ahead.

# The board is 9×9, with a second gold general on the other side of the king.

Drops were not originally part of shogi. In the 13th century, shogi underwent an expansion, creating the game of dai shogi

Dai shogi (大将棋, 'large chess') or Kamakura dai shogi (鎌倉大将棋) is a chess variant native to Japan. It derived from Heian era shogi, and is similar to standard shogi (sometimes called Japanese chess) in its rules and game play. Dai sho ...

, played on a 15×15 board with many new pieces, including the independently invented rook, bishop and queen of modern Western chess, the drunk elephant that promotes to a second king, and also the even more powerful lion, which among other idiosyncrasies has the power to move or capture twice per turn. Around the 14th or 15th centuries, the popularity of dai shogi then waned in favour of the smaller chu shogi

Chu shogi ( or Middle Shogi) is a strategy board game native to Japan. It is similar to modern shogi (sometimes called Japanese chess) in its rules and gameplay. Its name means "mid-sized shogi", from a time when there were three sizes of shogi ...

, played on a smaller 12×12 board which removed the weakest pieces from dai shogi, similarly to the development of Courier chess

Courier chess is a chess variant that dates from the 12th century and was popular for at least 600 years. It was a part of the slow evolution towards modern chess from Medieval Chess.

Medieval rules

Courier chess is played on an 8x12 board (i. ...

in the West. In the meantime, the original 9×9 shogi, now termed sho shogi Shō shōgi (小将棋 'small chess') is a 16th-century form of shogi (Japanese chess), and the immediate predecessor of the modern game. It was played on a 9×9 board with the same setup as in modern shogi, except that an extra piece stood in front ...

, continued to be played, but was regarded as less prestigious than chu shogi and dai shogi. Chu shogi was very popular in Japan, and the rook, bishop, and drunk elephant from it were added to sho shogi, where the first two remain today.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, yet more shogi variant

A shogi variant is a game related to or derived from shogi (Japanese chess). Many shogi variants have been developed over the centuries, ranging from some of the largest chess-type games ever played to some of the smallest. A few of these variant ...

s were described, on large boards and with many more pieces. The 1694 book ''Shōgi Zushiki

The ''Shōgi Zushiki'' (象戯図式), ''Sho Shōgi Zushiki'' (諸象戯図式), and ''Shōgi Rokushu no Zushiki'' (象棋六種之図式) are Edo period publications describing various variants

Variant may refer to:

In arts and entertainment

* ...

'' details tenjiku shogi

Tenjiku shogi (天竺将棋 ''tenjiku shōgi,'' "Indian chess" or 天竺大将棋 ''tenjiku dai shōgi'' "great Indian chess") is a large-board variant of shogi (Japanese chess). The game dates back to the 15th or 16th century and was based on the ...

(16×16), dai dai shogi Dai dai shōgi (大大将棋 'huge chess') is a large board variant of shogi (Japanese chess). The game dates back to the 15th century and is based on the earlier dai shogi. Apart from its size, the major difference is in the range of the pieces a ...

(17×17), maka dai dai shogi

Maka dai dai shōgi (摩訶大大将棋 or 摩𩹄大大象戯 'ultra-huge chess') is a large board variant of shogi (Japanese chess). The game dates back to the 15th century and is based on dai dai shogi and the earlier dai shogi. The three Edo-e ...

(19×19), and tai shogi

Tai shogi (泰将棋 ''tai shōgi'' or 無上泰将棋 ''mujō tai shōgi'' "grand chess", renamed from 無上大将棋 ''mujō dai shōgi'' "supreme chess" to avoid confusion with 大将棋 '' dai shōgi'') is a large-board variant of shogi (Jap ...

(25×25); it also mentions wa shogi

Wa shogi (和将棋, ''wa shōgi'', harmony chess) is a large board variant of shogi (Japanese chess) in which all of the pieces are named for animals. It is played either with or without drops.

Because of the terse and often incomplete wording ...

(11×11), ko shogi Kō shōgi (広将棋 or 廣象棋 'broad chess') is a large-board variant of shogi, or Japanese chess. The game dates back to the turn of the 18th century and is based on xiangqi and go as well as shogi. Credit for its invention has been given ...

(19×19), and taikyoku shogi

is the largest known variant of shogi (Japanese chess). The game was created around the mid-16th century (presumably by priests) and is based on earlier large board shogi games. Before the rediscovery of taikyoku shogi in 1997, tai shogi was be ...

(36×36). It is not thought that these games were played very much.

Chu shogi declined in popularity after the addition of drops to sho shogi and the removal of the drunk elephant in the 16th century, becoming moribund around the late 20th century. These changes to sho shogi created what is essentially the modern game of shogi.

Thailand

The Thai variant of chess,makruk

''Makruk'' ( th, หมากรุก; ; ), or Thai chess, is a board game that is descended from the 6th-century Indian game of ''chaturanga'' or a close relative thereof, and is therefore related to chess. It is part of the family of chess ...

is a close living relative to chaturanga, retaining the vizier, non-checkered board, limited promotion, offset kings, and elephant-like bishop move.

Mongolia

Chess is recorded from Mongolian-inhabited areas, where the pieces are now called: * King: Noyon – Ноён –lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or ar ...

* Queen: Bers / Nohoi – Бэрс / Нохой – dog (to guard the livestock)

* Bishop: Temē – Тэмээ – camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

* Knight: Morĭ – Морь – horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

* Rook: Tereg – Тэрэг – cart

A cart or dray (Australia and New Zealand) is a vehicle designed for transport, using two wheels and normally pulled by one or a pair of draught animals. A handcart is pulled or pushed by one or more people.

It is different from the flatbed tr ...

* Pawn: Hū – Хүү – boy (the piece often showed a puppy

A puppy is a juvenile dog. Some puppies can weigh , while larger ones can weigh up to . All healthy puppies grow quickly after birth. A puppy's coat color may change as the puppy grows older, as is commonly seen in breeds such as the Yorksh ...

)

Names recorded from the 1880s by Russian sources, quoted in Murray,Murray (1913), p. 367, p. 372 among the Soyot

The Soyot are ethnic group of Turkic origin live mainly in the Oka region in the Okinsky District in the Buryatia, Russia. According to the 2010 census, there were 3,608 Soyots in Russia. Their extinct language (partly revitalized) was of a Tur ...

people (who at the time spoke the Soyot

The Soyot are ethnic group of Turkic origin live mainly in the Oka region in the Okinsky District in the Buryatia, Russia. According to the 2010 census, there were 3,608 Soyots in Russia. Their extinct language (partly revitalized) was of a Tur ...

Turkic language

The Turkic languages are a language family of over 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and Western Asia. The Turkic languag ...

) include: ''merzé'' (dog), ''täbä'' (camel), ''ot'' (horse), ''ōl'' (child) and Mongolian names for the other pieces. This game is called shatar

Shatar ( Mongolian: ''Monggol sitar-a'', "Mongolian shatranj"; a.k.a. shatar) and hiashatar are two chess variants played in Mongolia.

Game rules

The rules are similar to standard chess; the differences being that:

* The ''noyan'' (, ''lord'' ...

; a large 10×10 variant called hiashatar

Hiashatar is a medieval chess variant played in Mongolia. The game is played on a 10×10 board. The pieces are the same as in chess with the exception that there is an additional piece which is called the "bodyguard".http://www.chessvariants.org ...

was also played.

The change with the queen is likely due to the Arabic word ''firzān'' or Persian word ''farzīn'' (= "vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

") being confused with Turkic or Mongolian native words (''merzé'' = "mastiff", ''bar'' or ''bars'' = "tiger", ''arslan'' = "lion").

Western chess is now the prevalent form of the game in Mongolia.

East Siberia

Chess was also recorded from theYakuts

The Yakuts, or the Sakha ( sah, саха, ; , ), are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly live in the Republic of Sakha in the Russian Federation, with some extending to the Amur, Magadan, Sakhalin regions, and the Taymyr and Evenk Districts ...

, Tunguses

The Evenks (also spelled Ewenki or Evenki based on their endonym )Autonym: (); russian: Эвенки (); (); formerly known as Tungus or Tunguz; mn, Хамниган () or Aiwenji () are a Tungusic people of North Asia. In Russia, the Eve ...

, and Yukaghir

The Yukaghirs, or Yukagirs ( (), russian: юкаги́ры) are a Siberian ethnic group people in the Russian Far East, living in the basin of the Kolyma River.

Geographic distribution

The Tundra Yukaghirs live in the Lower Kolyma region ...

s; but only as a children's game among the Chukchi. Chessmen have been collected from the Yakutat people in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

, having no resemblance to European chessmen, and thus likely part of a chess tradition coming from Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

.

Arab world

Chess passed from Persia to the Arab world, where its name changed to Arabicshatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

. From there it passed to Western Europe, probably via Spain.

Over the centuries, features of European chess (e.g. the modern moves of queen and bishop, and castling) found their way via trade into Islamic areas. Murray's sources found the old moves of queen and bishop still current in

Over the centuries, features of European chess (e.g. the modern moves of queen and bishop, and castling) found their way via trade into Islamic areas. Murray's sources found the old moves of queen and bishop still current in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

. The game became so popular it was used in writing at that time, played by nobility and regular people. The poet al-Katib once said, "The skilled player places his pieces in such a way as to discover consequences that the ignorant man never sees... thus, he serves the Sultan's interests, by showing how to foresee disaster."

Russia

Chess has 1000 years of history in Russia. Chess was probably brought to Old Russia in 9th century via the Volga-Caspian trade route. From the 10th century cultural connections with theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

also influenced the history of chess in Russia. The vocabulary in Russian chess has various foreign-language elements and testifies to different influences in the evolution of chess in Russia. Chess is mentioned in folk poems as a popular game and is documented in the Old Russian '' byliny''. Numerous archeological finds of the chess game have already been found in the regions of Old Russia. From 1262 on chess was called in Russia ''shakhmaty''. Various foreign travellers commented that in the 16th century, chess was popular among all classes in Russia. Ivan IV the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan ...

, who ruled Russia from 1530 to 1584, is said to have died while playing chess. In 1791 the popular chess book ''Morals of Chess'' by Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

was translated into Russian and published in the country. Chess enjoys a very high status in Russia and was gradually introduced as a school subject in all primary schools since 2017.

Europe

Early history

Shatranj

Shatranj ( ar, شطرنج; fa, شترنج; from Middle Persian ''chatrang'' ) is an old form of chess, as played in the Sasanian Empire. Its origins are in the Indian game of chaturaṅga. Modern chess gradually developed from this game, as i ...

made its way via the expanding Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic Arabian

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

empire to Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

. It also spread to the Byzantine empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, where it was called . Chess appeared in Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Alba ...

during the end of the first millennium, often introduced to new lands by conquering armies, such as the Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, Duchy of Brittany, Breton, County of Flanders, Flemish, and Kingdom of France, French troops, ...

.Riddler 1998 Previously little known, chess became popular in Northern Europe when figure pieces were introduced.

In the 14th century, Timur

Timur ; chg, ''Aqsaq Temür'', 'Timur the Lame') or as ''Sahib-i-Qiran'' ( 'Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction'), his epithet. ( chg, ''Temür'', 'Iron'; 9 April 133617–19 February 1405), later Timūr Gurkānī ( chg, ''Temür Kür ...

played an enlarged variation of the game which is commonly referred to as Tamerlane chess. This complex game involved each pawn having a particular purpose, as well as additional pieces.Rudolph, Jess. "The History and Variants in West Asia." Case Western Reserve University.

The sides are conventionally called White and Black. But, in earlier European chess writings, the sides were often called Red and Black because those were the commonly available colours of ink when handwriting drawing a chess game layout. In such layouts, each piece was represented by its name, often abbreviated (e.g. "ch'r" for French "chevalier" = "knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

").

The social value attached to the game – seen as a prestigious pastime associated with nobility and high culture – is clear from the expensive and exquisitely made chessboards of the medieval era. The popularity of chess in the Western courtly society peaked between the 12th and the 15th centuries.Gamer 1954 The game found mention in the vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

language literature throughout Europe, and many works were written on or about chess between the 12th and the 15th centuries. H. J. R. Murray

Harold James Ruthven Murray (24 June 1868 – 16 May 1955) was a British educationalist, inspector of schools, and prominent chess historian. His book, ''A History of Chess'', is widely regarded as the most authoritative and comprehensive his ...

divides the works into three distinct parts: the didactic

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need to ...

works e.g. Alexander of Neckham

Alexander Neckam (8 September 115731 March 1217) was an English magnetician, poet, theologian, and writer. He was an abbot of Cirencester Abbey from 1213 until his death.

Early life

Born on 8 September 1157 in St Albans, Alexander shared his b ...

's ''De scaccis'' (c. 1180); works of morality like ''Liber de moribus hominum et officiis nobilium sive super ludo scacchorum'' (Book of the customs of men and the duties of nobles or the Book of Chess), written by Jacobus de Cessolis

Jacobus de Cessolis ( it, Jacopo da Cessole; c. 1250 – c. 1322) was an Italian author of the most famous morality book on chess in the Middle Ages.

In the second half of the 13th century, Jacobus de Cessolis, a Dominican friar in Cessole ( ...

; and the works related to various chess problems, written largely after 1205. Chess terms, like ''check,'' were used by authors as a metaphor for various situations.Vale 2001: 177

Chess was soon incorporated into the knightly style of life in Europe. Peter Alfonsi

Petrus Alphonsi (died after 1116) was a Jewish Spanish physician, writer, astronomer and polemicist who converted to Christianity in 1106. He is also known just as Alphonsi, and as Peter Alfonsi or Peter Alphonso, and was born Moses Sephardi. ...

, in his work ''Disciplina Clericalis,'' listed chess among the seven skills that a good knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

must acquire.Vale 2001: 171 Chess also became a subject of art during this period, with caskets and pendants decorated in various chess forms. Queen Margaret of England had green and red chess sets

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to distin ...

made of jasper and crystal. Kings Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the No ...

, Henry II and Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was overl ...

of England were chess patrons. King Alfonso X

Alfonso X (also known as the Wise, es, el Sabio; 23 November 1221 – 4 April 1284) was King of Castile, León and Galicia from 30 May 1252 until his death in 1284. During the election of 1257, a dissident faction chose him to be king of Germ ...

of Castile and Tsar Ivan IV of Russia

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan ...

gained a similar status.

Saint Peter Damian

Peter Damian ( la, Petrus Damianus; it, Pietro or '; – 21 or 22 February 1072 or 1073) was a reforming Benedictine monk and cardinal in the circle of Pope Leo IX. Dante placed him in one of the highest circles of '' Paradiso'' ...

denounced the bishop of Florence in 1061 for playing chess even when aware of its evil effects on the society. The bishop of Florence defended himself by declaring that chess involved skill and was therefore "unlike other games," and similar arguments followed in the coming centuries. Two incidents in 13th-century London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, in which men of Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

resorted to violence resulting in death as an outcome of playing chess, caused further sensation and alarm. The growing popularity of the game – now associated with revelry and violence – alarmed the Church.

The practice of playing chess for money became so widespread during the 13th century that Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

issued an ordinance against gambling in 1254.Vale 2001: 172 This ordinance turned out to be unenforceable and was largely neglected by the common public, and even the courtly society, which continued to enjoy the now-prohibited chess tournaments uninterrupted.

Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

playing chess, ''Libro de los juegos

The ''Libro de los juegos'' (Spanish: "Book of games"), or ''Libro de axedrez, dados e tablas'' ("Book of chess, dice and tables", in Old Spanish), was a Spanish language, Spanish translation of Arabic texts on chess, dice and Tables games, tabl ...

'', 1283

Image:Meister der Manessischen Liederhandschrift 004.jpg, Otto IV of Brandenburg playing chess with a woman, 1305 to 1340

Image:Chess playing Louvre OA117.jpg, A couple playing chess, ivory mirror case c. 1300

Shapes of pieces

The pieces, which had been nonrepresentational in Islamic countries (see piece values in shantranj), changed shape in Christian cultures. Carved images of men and animals reappeared. The shape of the rook, originally a rectangular block with a V-shaped cut in the top, changed; the two top parts separated by the split tended to get long and hang over, and in some old pictures look like horses' heads. The split top of the piece now called the bishop was interpreted as a bishop's mitre or a fool's cap. By the mid-12th century, the pieces of the chess set were depicted as kings, queens, bishops, knights andmen at arms

A man-at-arms was a soldier of the High Medieval to Renaissance periods who was typically well-versed in the use of arms and served as a fully-armoured heavy cavalryman. A man-at-arms could be a knight, or other nobleman, a member of a kni ...

.Vale 2001: 173 Chessmen made of ivory began to appear in North-West Europe

Northwestern Europe, or Northwest Europe, is a loosely defined subregion of Europe, overlapping Northern and Western Europe. The region can be defined both geographically and ethnographically.

Geographic definitions

Geographically, Northw ...

, and ornate pieces of traditional knight warriors were used as early as the mid 13th century. The initially nondescript pawn had now found association with the ''pedes'', ''pedinus,'' or the footman

A footman is a male domestic worker employed mainly to wait at table or attend a coach or carriage.

Etymology

Originally in the 14th century a footman denoted a soldier or any pedestrian, later it indicated a foot servant. A running footman deli ...

, which symbolized both infantry and loyal domestic service.

Names of pieces

The following table provides a glimpse of the changes in names and character of chess pieces as they crossed from India through Persia to Europe: The game, as played during the early Middle Ages, was slow, with many games lasting days. Some variations in rules began to change the shape of the game by the year 1300. A notable, but initially unpopular, change was the ability of the pawn to move two places in the first move instead of one. In Europe some of the pieces gradually received new names: * Fers: "queen", because it starts beside the king. * Aufin: "bishop", because its two points looked like a bishop'smitre

The mitre (Commonwealth English) (; Greek: μίτρα, "headband" or "turban") or miter (American English; see spelling differences), is a type of headgear now known as the traditional, ceremonial headdress of bishops and certain abbots in ...

. Its Latin name was reinterpreted many ways.

Early changes to the rules

Attempts to make the start of the game run faster to get the opposing pieces in contact sooner included: * Pawn moving two squares in its first move. This led to the ''en passant