)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesMali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mal ...

, the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics ( ICRISAT) and the Aga Khan Foundation

The Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) is a private, not-for-profit international development agency, which was founded in 1967 by Shah Karim Al Hussaini, Aga Khan IV, the 49th Hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. AKF seeks to provide long-term ...

trained women's groups to make ''equinut'', a healthy and nutritional version of the traditional recipe ''di-dèguè'' (comprising peanut paste, honey and millet or rice flour). The aim was to boost nutrition and livelihoods by producing a product that women could make and sell, and which would be accepted by the local community because of its local heritage.

Middle East and North Africa

Six countries in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

region are on target to meet goals for reducing underweight children by 2015, and 12 countries have prevalence rates below 10%.Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, Sudan, and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

.Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

are underweight, a percentage that has worsened by 4% since 1990.Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red ...

, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

are all projected to meet minimum nutrition goals, with OPT, Syrian AR, and Tunisia the fastest improving regions.United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at t ...

, for example, despite being a wealthy nation, has similar child death rates due to malnutrition to those seen in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

.

East Asia and the Pacific

The East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

and Pacific region has reached its goals on nutrition, in part due to the improvements contributed by China, the region's most populous country.Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

, Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

, and Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

are all projected to reach nutrition MDGs.Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, bor ...

has the lowest under five mortality rate of any nation, besides Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, in the world, at 3%.Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

has the highest rate of child mortality in the region (141 per 1,000 live births), while still its proportion of underweight children increased by 5 percent to 45% in 2000. Further nutrient indicators show that only 12 per cent of Cambodian babies are exclusively breastfed and only 14 per cent of households consume iodized salt

Iodised salt ( also spelled iodized salt) is table salt mixed with a minute amount of various salts of the element iodine. The ingestion of iodine prevents iodine deficiency. Worldwide, iodine deficiency affects about two billion people and is t ...

.

Latin America and the Caribbean

This region has undergone the fastest progress in decreasing poor nutrition status of children in the world.Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-eth ...

region has reduced underweight children prevalence by 3.8% every year between 1990 and 2004, with a current rate of 7% underweight.Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

has seen improvement from 9 to 4 percent underweight under 5 between 1996 and 2004.Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, and Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

.Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, mostly have relatively low rates of underweight under 5, with only 6% and 8%.

Nutrition access disparities

Occurring throughout the world, lack of proper nutrition is both a consequence and cause of poverty.socioeconomic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their l ...

status, both between and within nations, provide the largest threat to child nutrition in industrialized nations, where social inequality is on the rise.underweight

An underweight person is a person whose body weight is considered too low to be healthy. A person who is underweight is malnourished.

Assessment

The body mass index, a ratio of a person's weight to their height, has traditionally been used ...

as those in the richest.quintile

Quintile may refer to:

*In statistics, a quantile for the case where the sample or population is divided into fifths

*Quintiles, a biotechnology research company based in the United States

*Quintile (astrology)

In astrology, an aspect is an ...

and whose mothers have the least education demonstrate the highest rates of child mortality and stunting.South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

.

Nutrition policy

Nutrition interventions

Nutrition directly influences progress towards meeting the Millennium Goals of eradicating hunger and poverty through health and education.

Implementation and delivery platforms

In April 2010, the World Bank and the IMF released a policy briefing entitled "Scaling up Nutrition (SUN): A Framework for action" that represented a partnered effort to address the Lancet's Series on under nutrition, and the goals it set out for improving under nutrition.UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Cur ...

in 2010 as a road map encouraging the coherence of stakeholders like governments, academia

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary or tertiary higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membership). The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, ...

, UN system organizations and foundations in working towards reducing under nutrition.gender equality

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing d ...

, agriculture, food security

Food security speaks to the availability of food in a country (or geography) and the ability of individuals within that country (geography) to access, afford, and source adequate foodstuffs. According to the United Nations' Committee on World ...

, social protection

Social protection, as defined by the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, is concerned with preventing, managing, and overcoming situations that adversely affect people's well-being. Social protection consists of policies and ...

, education, water supply, sanitation, and health care".Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, improved production and market availability of iodized salt increased household consumption.

Advice and guidance

Government policies

Canada's Food Guide

''Canada's Food Guide'' (french: Guide alimentaire canadien) is a nutrition guide produced by Health Canada. In 2007, it was reported to be the second most requested Canadian government publication, behind the Income Tax Forms. The Health Canada ...

is an example of a government-run nutrition program. Produced by Health Canada, the guide advises food quantities, provides education on balanced nutrition, and promotes physical activity in accordance with government-mandated nutrient needs. Like other nutrition programs around the world, Canada's Food Guide divides nutrition into four main food groups: vegetables and fruit, grain products, milk and alternatives, and meat and alternatives. Unlike its American counterpart, the Canadian guide references and provides alternative to meat and dairy, which can be attributed to the growing vegan

Veganism is the practice of abstaining from the use of animal product—particularly in diet—and an associated philosophy that rejects the commodity status of animals. An individual who follows the diet or philosophy is known as a vegan. ...

and vegetarian

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetariani ...

movements.

In the US, nutritional standards and recommendations are established jointly by the US Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

and US Department of Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a cabinet-level executive branch department of the U.S. federal government created to protect the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. Its motto is ...

(HHS) and these recommendations are published as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Dietary and physical activity guidelines from the USDA are presented in the concept of MyPlate, which superseded the food pyramid, which replaced the Four Food Groups. The Senate committee currently responsible for oversight of the USDA is the ''Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee''. Committee hearings are often televised on C-SPAN. The U.S. HHS provides a sample week-long menu that fulfills the nutritional recommendations of the government.

Government programs

Governmental organisations have been working on nutrition literacy interventions in non-primary health care settings to address the nutrition information problem in the U.S. Some programs include:

The Family Nutrition Program (FNP) is a free nutrition education program serving low-income adults around the U.S. This program is funded by the Food Nutrition Service's (FNS) branch of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) usually through a local state academic institution that runs the program. The FNP has developed a series of tools to help families participating in the Food Stamp Program stretch their food dollar and form healthful eating habits including nutrition education.

Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program

(ENFEP) is a unique program that currently operates in all 50 states and in American Samoa, Guam, Micronesia, Northern Marianas, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. It is designed to assist limited-resource audiences in acquiring the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and changed behavior necessary for nutritionally sound diets, and to contribute to their personal development and the improvement of the total family diet and nutritional well-being.

An example of a state initiative to promote nutrition literacy i

Smart Bodies

a public-private partnership between the state's largest university system and largest health insurer, Louisiana State Agricultural Center and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana Foundation. Launched in 2005, this program promotes lifelong healthful eating patterns and physically active lifestyles for children and their families. It is an interactive educational program designed to help prevent childhood obesity through classroom activities that teach children healthful eating habits and physical exercise.

Education

Nutrition is taught in schools in many countries. In England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

, the Personal and Social Education

Personal and social education (PSE) is a component of the state school curriculum in Scotland and Wales. PSE became a statutory requirement in schools in September 2003, and is compulsory for all students at key stages 1, 2, 3 and 4 (5 to 16 yea ...

and Food Technology curricula include nutrition, stressing the importance of a balanced diet and teaching how to read nutrition labels on packaging. In many schools, a Nutrition class will fall within the Family and Consumer Science (FCS) or Health departments. In some American schools, students are required to take a certain number of FCS or Health related classes. Nutrition is offered at many schools, and, if it is not a class of its own, nutrition is included in other FCS or Health classes such as: Life Skills, Independent Living, Single Survival, Freshmen Connection, Health etc. In many Nutrition classes, students learn about the food groups, the food pyramid, Daily Recommended Allowances, calories, vitamins, minerals, malnutrition, physical activity, healthful food choices, portion sizes, and how to live a healthy life.

A 1985 US National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

report entitled ''Nutrition Education in US Medical Schools'' concluded that nutrition education in medical schools was inadequate.[Commission on Life Sciences. (1985). ''Nutrition Education in US Medical Schools'']

p. 4

National Academies Press. Only 20% of the schools surveyed taught nutrition as a separate, required course. A 2006 survey found that this number had risen to 30%. Membership by physicians in leading professional nutrition societies such as the American Society for Nutrition

The American Society for Nutrition (ASN) is an American society for professional researchers and practitioners in the field of nutrition. ASN publishes four journals in the field of nutrition. It has been criticized for its financial ties to the ...

has generally declined from the 1990s.

Professional organizations

In the US, Registered dietitian nutritionists (RDs or RDNs) are health professionals qualified to provide safe, evidence-based dietary advice which includes a review of what is eaten, a thorough review of nutritional health, and a personalized nutritional treatment plan through dieting. They also provide preventive and therapeutic programs at work places, schools and similar institutions. Certified Clinical Nutritionist A nutritionist is a person who advises others on matters of food and nutrition and their impacts on health. Some people specialize in particular areas, such as sports nutrition, public health, or animal nutrition, among other disciplines. In many ...

s or CCNs, are trained health professionals who also offer dietary advice on the role of nutrition in chronic disease, including possible prevention or remediation by addressing nutritional deficiencies before resorting to drugs. Government regulation especially in terms of licensing, is currently less universal for the CCN than that of RD or RDN. Another advanced Nutrition Professional is a Certified Nutrition Specialist or CNS. These Board Certified Nutritionists typically specialize in obesity

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it may negatively affect health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's ...

and chronic disease

A chronic condition is a health condition or disease that is persistent or otherwise long-lasting in its effects or a disease that comes with time. The term ''chronic'' is often applied when the course of the disease lasts for more than three m ...

. In order to become board certified, potential CNS candidate must pass an examination, much like Registered Dieticians. This exam covers specific domains within the health sphere including; Clinical Intervention and Human Health. The National Board of Physician Nutrition Specialists offers board certification for physicians practicing nutrition medicine.

Nutrition for special populations

Sports nutrition

The protein requirement for each individual differs, as do opinions about whether and to what extent physically active people require more protein. The 2005 Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA), aimed at the general healthy adult population, provide for an intake of 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

Maternal nutrition

Paediatric nutrition

Adequate nutrition is essential for the growth of children from infancy right through until adolescence. Some nutrients are specifically required for growth on top of nutrients required for normal body maintenance, in particular calcium and iron.

Elderly nutrition

Malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is "a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients" which adversely affects the body's tissues ...

in general is higher among the elderly, but has different aspects in developed and undeveloped countries.

History of human nutrition

Early human nutrition was largely determined by the availability

In reliability engineering, the term availability has the following meanings:

* The degree to which a system, subsystem or equipment is in a specified operable and committable state at the start of a mission, when the mission is called for at ...

and palatability of foods. Humans evolved as omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nut ...

hunter-gatherers, though the diet of humans has varied significantly depending on location and climate. The diet in the tropics tended to depend more heavily on plant foods, while the diet at higher latitudes tended more towards animal products. Analyses of postcranial and cranial remains of humans and animals from the Neolithic, along with detailed bone-modification studies, have shown that cannibalism also occurred among prehistoric humans.

Agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

developed at different times in different places, starting about 11,500 years ago, providing some cultures with a more abundant supply of grains (such as wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and '' Porteresia'', both wild and domesticat ...

and maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

) and potatoes; and originating staples such as bread, pasta dough

Dough is a thick, malleable, sometimes elastic paste made from grains or from leguminous or chestnut crops. Dough is typically made by mixing flour with a small amount of water or other liquid and sometimes includes yeast or other leavenin ...

, and tortillas

A tortilla (, ) is a thin, circular unleavened flatbread originally made from maize hominy meal, and now also from wheat flour. The Aztecs and other Nahuatl speakers called tortillas ''tlaxcalli'' (). First made by the indigenous peoples of M ...

. The domestication of animals provided some cultures with milk and dairy products.

In 2020, archeological research discovered a frescoed thermopolium

In the ancient Greco-Roman world, a thermopolium (plural ''thermopolia''), from Greek (''thermopōlion''), i.e. cook-shop, literally "a place where (something) hot is sold", was a commercial establishment where it was possible to purchase ready ...

(a fast-food counter) in an exceptional state of preservation from 79 in Pompeii, including 2,000-year-old foods available in some of the deep terra cotta jars.

Nutrition in antiquity

During classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, diets consisted of simple fresh or preserved whole foods that were either locally grown or transported from neighboring areas during times of crisis.

18th century until today: food processing and nutrition

Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

in the 18th and 19th century, the food processing industry has invented many technologies

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

that both help keep foods fresh longer and alter the fresh state of food as they appear in nature. Cooling

Cooling is removal of heat, usually resulting in a lower temperature and/or phase change. Temperature lowering achieved by any other means may also be called cooling.ASHRAE Terminology, https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/free-resources/as ...

and freezing

Freezing is a phase transition where a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point. In accordance with the internationally established definition, freezing means the solidification phase change of a liquid ...

are primary technologies used to maintain freshness, whereas many more technologies have been invented to allow foods to last longer without becoming spoiled. These latter technologies include pasteurisation

Pasteurization or pasteurisation is a process of food preservation in which packaged and non-packaged foods (such as milk and fruit juices) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than , to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life.

Th ...

, autoclavation, drying

Drying is a mass transfer process consisting of the removal of water or another solvent by evaporation from a solid, semi-solid or liquid. This process is often used as a final production step before selling or packaging products. To be consider ...

, salting, and separation of various components, all of which appearing to alter the original nutritional contents of food. Pasteurisation and autoclavation (heating techniques) have no doubt improved the safety of many common foods, preventing epidemics of bacterial infection.

Modern separation techniques such as milling, centrifugation, and pressing have enabled concentration of particular components of food, yielding flour, oils, juices, and so on, and even separate fatty acids, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. Inevitably, such large-scale concentration changes the nutritional content of food, saving certain nutrients while removing others. Heating techniques may also reduce the content of many heat-labile nutrients such as certain vitamins and phytochemicals, and possibly other yet-to-be-discovered substances.

Because of reduced nutritional value, processed foods are often enriched or fortified with some of the most critical nutrients (usually certain vitamins) that were lost during processing. Nonetheless, processed foods tend to have an inferior nutritional profile compared to whole, fresh foods, regarding content of both sugar and high GI starches, potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosph ...

/sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable ...

, vitamins, fiber, and of intact, unoxidized (essential) fatty acids. In addition, processed foods often contain potentially harmful substances such as oxidized fats and trans fatty acids.

A dramatic example of the effect of food processing on a population's health is the history of epidemics of beri-beri

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (Vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The two main types in adults are wet beriberi and dry beriberi. Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system, r ...

in people subsisting on polished rice. Removing the outer layer of rice by polishing it removes with it the essential vitamin thiamine

Thiamine, also known as thiamin and vitamin B1, is a vitamin, an essential micronutrient, that cannot be made in the body. It is found in food and commercially synthesized to be a dietary supplement or medication. Phosphorylated forms of thi ...

, causing beri-beri. Another example is the development of scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

among infants in the late 19th century in the United States. It turned out that the vast majority of those affected were being fed milk that had been heat-treated (as suggested by Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named after ...

) to control bacterial disease. Pasteurisation was effective against bacteria, but it destroyed the vitamin C.

Research of nutrition and nutritional science

Antiquity: Start of scientific research on nutrition

Around 3000 BC the Vedic texts made mention of scientific research on nutrition. The first recorded dietary advice, carved into a Babylonian stone tablet in about 2500 BC, cautioned those with pain inside to avoid eating

Around 3000 BC the Vedic texts made mention of scientific research on nutrition. The first recorded dietary advice, carved into a Babylonian stone tablet in about 2500 BC, cautioned those with pain inside to avoid eating onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' L., from Latin ''cepa'' meaning "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus ''Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onio ...

s for three days. Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

, later found to be a vitamin C deficiency

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

, was first described in 1500 BC in the Ebers Papyrus.

According to Walter Gratzer, the study of nutrition probably began during the 6th century BC. In China, the concept of '' qi'' developed, a spirit or "wind" similar to what Western Europeans later called ''pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for " spirit" or "soul". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is ...

''.[Gratzer 2005, p. 40.] Food was classified into "hot" (for example, meats, blood, ginger, and hot spices) and "cold" (green vegetables) in China, India, Malaya, and Persia.Humours

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

'' developed perhaps first in China alongside ''qi''.Wu Xing Wuxing may refer to:

Places in China Counties and districts

*Huzhou, formerly Wuxing County, Zhejiang, China

*Wuxing District (吴兴区), central district of Huzhou

Subdistricts (五星街道)

*Wuxing Subdistrict, Mudanjiang, in Dong'an District ...

: fire, water, earth, wood, and metal), and he classified diseases as well as prescribed diets.[Gratzer 2005, p. 41.] About the same time in Italy, Alcmaeon of Croton

Alcmaeon of Croton (; el, Ἀλκμαίων ὁ Κροτωνιάτης, ''Alkmaiōn'', ''gen''.: Ἀλκμαίωνος; fl. 5th century BC) was an early Greek medical writer and philosopher-scientist. He has been described as one of the most ...

(a Greek) wrote of the importance of equilibrium between what goes in and what goes out, and warned that imbalance would result in disease marked by obesity

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it may negatively affect health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's ...

or emaciation

Emaciation is defined as the state of extreme thinness from absence of body fat and muscle wasting usually resulting from malnutrition.

Characteristics

In humans, the physical appearance of emaciation includes thinned limbs, pronounced and protrud ...

.[Gratzer 2005, p. 36.]

Around 475 BC, Anaxagoras wrote that food is absorbed by the human body and, therefore, contains "homeomerics" (generative components), suggesting the existence of nutrients.[''History of the Study of Nutrition in Western Culture'']

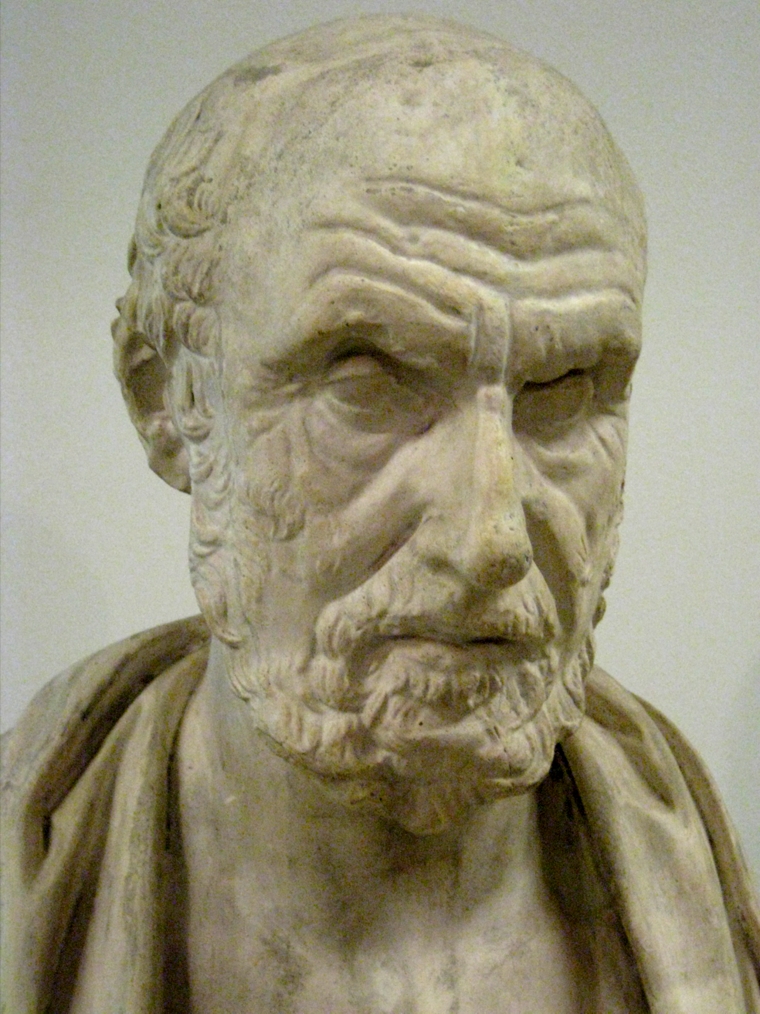

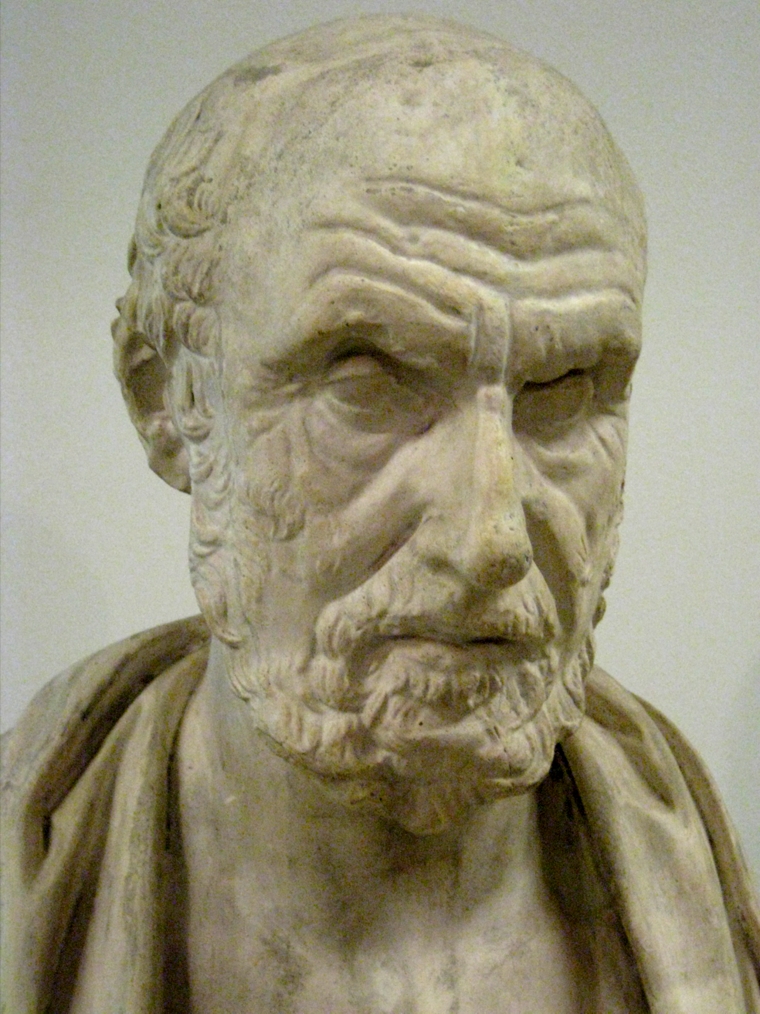

(Rai University lecture notes for General Nutrition course, 2004) Around 400 BC, Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

, who recognized and was concerned with obesity, which may have been common in southern Europe at the time,moderation

Moderation is the process of eliminating or lessening extremes. It is used to ensure normality throughout the medium on which it is being conducted. Common uses of moderation include:

*Ensuring consistency and accuracy in the marking of stud ...

and emphasized exercise.Salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

, pepper

Pepper or peppers may refer to:

Food and spice

* Piperaceae or the pepper family, a large family of flowering plant

** Black pepper

* ''Capsicum'' or pepper, a genus of flowering plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae

** Bell pepper

** Chili ...

and other spices were prescribed for various ailments in various preparations for example mixed with vinegar. In the 2nd century BC, Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato (; 234–149 BC), also known as Cato the Censor ( la, Censorius), the Elder and the Wise, was a Roman soldier, senator, and historian known for his conservatism and opposition to Hellenization. He was the first to write his ...

believed that cabbage (or the urine of cabbage-eaters) could cure digestive diseases, ulcers, warts, and intoxication. Living about the turn of the millennium, Aulus Celsus, an ancient Roman doctor, believed in "strong" and "weak" foods (bread for example was strong, as were older animals and vegetables).Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th century BC setting. Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon", it combines a prophecy of history with an eschatology ...

, dated to the second century BC, contains a description of a comparison in health of captured people following Jewish dietary laws versus the diet of the soldiers of the king of Babylon. (The story may be legendary rather than historical.)

1st to 17th century

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

was physician to gladiators in Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greece, ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a ...

, and in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, physician to Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

and the three emperors who succeeded him.[Gratzer 2005, p. 38.]

In use from his life in the 1st century AD until the 17th century, it was heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

to disagree with the teachings of Galen for 1500 years.[Gratzer 2005, pp. 38, 39, 41.] Most of Galen's teachings were gathered and enhanced in the late 11th century by Benedictine monks

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict ( la, Ordo Sancti Benedicti, abbreviated as OSB), are a Christian monasticism, monastic Religious order (Catholic), religious order of the Catholic Church following the Rule of Saint Benedic ...

at the School of Salerno

The Schola Medica Salernitana ( it, Scuola Medica Salernitana) was a Medieval medical school, the first and most important of its kind. Situated on the Tyrrhenian Sea in the south Italian city of Salerno, it was founded in the 9th century and ros ...

in ''Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum

''Regimen sanitatis Salernitanum'', Latin: ''The Salernitan Rule of Health'' (commonly known as ''Flos medicinae'' or ''Lilium medicinae'' - ''The Flower of Medicine'', ''The Lily of Medicine'') is a medieval didactic poem in hexameter verse. It ...

'', which still had users in the 17th century.[Gratzer 2005, p. 39.] Galen believed in the bodily ''humours'' of Hippocrates, and he taught that ''pneuma'' is the source of life. Four elements

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simi ...

(earth, air, fire and water) combine into "complexion", which combines into states (the four temperaments

The four temperament theory is a proto-psychological theory which suggests that there are four fundamental personality types: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. Most formulations include the possibility of mixtures among the types w ...

: sanguine, phlegmatic, choleric, and melancholic). The states are made up of pairs of attributes (hot and moist, cold and moist, hot and dry, and cold and dry), which are made of four humours

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

: blood, phlegm, green (or yellow) bile, and black bile (the bodily form of the elements). Galen thought that for a person to have gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

, kidney stones

Kidney stone disease, also known as nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis, is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material (kidney stone) develops in the urinary tract. Kidney stones typically form in the kidney and leave the body in the urine s ...

, or arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

was scandalous, which Gratzer likens to Samuel Butler's ''Erehwon

''Erewhon: or, Over the Range'' () is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872, set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.

The firs ...

'' (1872) where sickness is a crime.Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

He w ...

was probably the first to criticize Galen publicly.Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

compared metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run c ...

to a burning candle. Leonardo did not publish his works on this subject, but he was not afraid of thinking for himself and he definitely disagreed with Galen.Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' '' ...

, sometimes called the father of modern human anatomy

The human body is the structure of a human being. It is composed of many different types of cells that together create tissues and subsequently organ systems. They ensure homeostasis and the viability of the human body.

It comprises a he ...

, overturned Galen's ideas. He was followed by piercing thought amalgamated with the era's mysticism and religion sometimes fueled by the mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

of Newton and Galileo. Jan Baptist van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont (; ; 12 January 1580 – 30 December 1644) was a chemist, physiologist, and physician from Brussels. He worked during the years just after Paracelsus and the rise of iatrochemistry, and is sometimes considered to ...

, who discovered several gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

es such as carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

, performed the first quantitative experiment. Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

advanced chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

. Sanctorius

Santorio Santori (29 March, 1561 – 25 February, 1636) also called Santorio Santorio, Santorio de' Sanctoriis, or Sanctorius of Padua and various combinations of these names, was an Italian physiologist, physician, and professor, who introduc ...

measured body weight

Human body weight is a person's mass or weight.

Strictly speaking, body weight is the measurement of weight without items located on the person. Practically though, body weight may be measured with clothes on, but without shoes or heavy accessor ...

. Physician Herman Boerhaave

Herman Boerhaave (, 31 December 1668 – 23 September 1738Underwood, E. Ashworth. "Boerhaave After Three Hundred Years." ''The British Medical Journal'' 4, no. 5634 (1968): 820–25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20395297.) was a Dutch botanist, ...

modeled the digestive process. Physiologist Albrecht von Haller

Albrecht von Haller (also known as Albertus de Haller; 16 October 170812 December 1777) was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist, encyclopedist, bibliographer and poet. A pupil of Herman Boerhaave, he is often referred to as "the fa ...

worked out the difference between nerve

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons) in the peripheral nervous system.

A nerve transmits electrical impulses. It is the basic unit of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the e ...

s and muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

s.

18th and 19th century: Lind, Lavoisier and modern science

Sometimes forgotten during his life,

Sometimes forgotten during his life, James Lind

James Lind (4 October 1716 – 13 July 1794) was a Scottish doctor. He was a pioneer of naval hygiene in the Royal Navy. By conducting one of the first ever clinical trials, he developed the theory that citrus fruits cured scurvy.

Lind arg ...

, a physician in the British navy, performed the first scientific

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

nutrition experiment in 1747. Lind discovered that lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

juice saved sailors that had been at sea for years from scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

, a deadly and painful bleeding disorder. Between 1500 and 1800, an estimated two million sailors had died of scurvy.vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits and vegetables, also sold as a dietary supplement and as a topical 'serum' ingredient to treat melasma (dark pigment spots) ...

within citrus fruits would not be identified by scientists until 1932. Around 1770,

Around 1770, Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and th ...

discovered the details of metabolism, demonstrating that the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of food is the source of body heat. Called the most fundamental chemical discovery of the 18th century, Lavoisier discovered the principle of conservation of mass

In physics and chemistry, the law of conservation of mass or principle of mass conservation states that for any system closed to all transfers of matter and energy, the mass of the system must remain constant over time, as the system's mass can ...

. His ideas made the phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory is a superseded scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burni ...

of combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

obsolete.

In 1790, George Fordyce

George Fordyce (18 November 1736 – 25 May 1802) was a distinguished Scotland, Scottish physician, lecturer on medicine, and chemist, who was a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

Early life

George Fo ...

recognized calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

as necessary for the survival of fowl. In the early 19th century, the elements carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon mak ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

, and oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as ...

were recognized as the primary components of food, and methods to measure their proportions were developed.François Magendie

__NOTOC__

François Magendie (6 October 1783 – 7 October 1855) was a French physiologist, considered a pioneer of experimental physiology. He is known for describing the foramen of Magendie. There is also a ''Magendie sign'', a downward a ...

discovered that dogs fed only carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or m ...

s (sugar), fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple est ...

(olive oil), and water

Water (chemical formula ) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living ...

died evidently of starvation, but dogs also fed protein survived – identifying protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

as an essential dietary component. William Prout

William Prout FRS (; 15 January 1785 – 9 April 1850) was an English chemist, physician, and natural theologian. He is remembered today mainly for what is called Prout's hypothesis.

Biography

Prout was born in Horton, Gloucestershire in 1 ...

in 1827 was the first person to divide foods into carbohydrates, fat, and protein. In 1840, Justus von Liebig

Justus Freiherr von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 20 April 1873) was a German scientist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry. As a professor at t ...

discovered the chemical makeup of carbohydrates (sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

s), fats (fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, ...

s) and proteins (amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s). During the 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Dumas

Jean Baptiste André Dumas (14 July 180010 April 1884) was a French chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuring v ...

and von Liebig quarrelled over their shared belief that animals get their protein directly from plants (animal and plant protein are the same and that humans do not create organic compounds). With a reputation as the leading organic chemist

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J.; ...

of his day but with no credentials in animal physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical an ...

, von Liebig grew rich making food extract

An extract is a substance made by extracting a part of a raw material, often by using a solvent such as ethanol, oil or water. Extracts may be sold as tinctures, absolutes or in powder form.

The aromatic principles of many spices, nuts, h ...

s like beef bouillon

Bouillon can refer to:

Food

* Bouillon (broth), a simple broth

** Court-bouillon, a quick broth

* Bouillon (soup), a Haitian soup

* Bouillon (restaurant), a traditional type of French restaurant

**Bouillon Chartier, a bouillon restaurant foun ...

and infant formula

Infant formula, baby formula, or simply formula (American English); or baby milk, infant milk or first milk (British English), is a manufactured food designed and marketed for feeding to babies and infants under 12 months of age, usually prepar ...

that were later found to be of questionable nutritious value.

In the early 1880s, Kanehiro Takaki observed that Japanese sailors (whose diets consisted almost entirely of white rice) developed

In the early 1880s, Kanehiro Takaki observed that Japanese sailors (whose diets consisted almost entirely of white rice) developed beriberi

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (Vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The two main types in adults are wet beriberi and dry beriberi. Wet beriberi affects the cardiovascular system, r ...

(or endemic neuritis, a disease causing heart problems and paralysis), but British sailors and Japanese naval officers did not. Adding various types of vegetables and meats to the diets of Japanese sailors prevented the disease. (This was not because of the increased protein as Takaki supposed, but because it introduced a few parts per million of thiamine

Thiamine, also known as thiamin and vitamin B1, is a vitamin, an essential micronutrient, that cannot be made in the body. It is found in food and commercially synthesized to be a dietary supplement or medication. Phosphorylated forms of thi ...

to the diet.)).

In the 1860s, Claude Bernard

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. Historian I. Bernard Cohen of Harvard University called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term ''milieu intérieur'', and the a ...

discovered that body fat can be synthesized from carbohydrate and protein, showing that the energy in blood glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

can be stored as fat or as glycogen.

In 1896, Eugen Baumann

Eugen Baumann (12 December 1846 – 3 November 1896) was a German chemist. He was one of the first people to create polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and, together with Carl Schotten, he discovered the Schotten-Baumann reaction.

Life

Baumann was born i ...

observed iodine in thyroid glands. In 1897, Christiaan Eijkman

Christiaan Eijkman ( , , ; 11 August 1858 – 5 November 1930) was a Dutch physician and professor of physiology whose demonstration that beriberi is caused by poor diet led to the discovery of antineuritic vitamins (thiamine). Together with S ...

worked with natives of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

, who also had beriberi. Eijkman observed that chickens fed the native diet of white rice developed the symptoms of beriberi but remained healthy when fed unprocessed brown rice with the outer bran intact. His assistant, Gerrit Grijns correctly identified and described the anti-beriberi substance in rice. Eijkman cured the natives by feeding them brown rice, discovering that food can cure disease. Over two decades later, nutritionists learned that the outer rice bran contains vitamin B1, also known as thiamine

Thiamine, also known as thiamin and vitamin B1, is a vitamin, an essential micronutrient, that cannot be made in the body. It is found in food and commercially synthesized to be a dietary supplement or medication. Phosphorylated forms of thi ...

.

Early 20th century

In the early 20th century,

In the early 20th century, Carl von Voit

Carl von Voit (31 October 1831 – 31 January 1908) was a German physiologist and dietitian.

Biography

Voit was born in Amberg, the son of August von Voit and Mathilde Burgett. From 1848 to 1854 he studied at the universities of Munich and W ...

and Max Rubner

Max Rubner (2 June 1854, Munich27 April 1932, Berlin) was a German physiologist and hygienist.

Academic career

He studied at the University of Munich and worked as an assistant under Adolf von Baeyer and Carl von Voit (doctorate 1878). Later ...

independently measured caloric energy expenditure in different species of animals, applying principles of physics in nutrition. In 1906, Edith G. Willcock and Frederick Hopkins

Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins (20 June 1861 – 16 May 1947) was an English biochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1929, with Christiaan Eijkman, for the discovery of vitamins, even though Casimir Funk, a Po ...

showed that the amino acid tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α- carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromatic ...

aids the well-being of mice but it did not assure their growth. In the middle of twelve years of attempts to isolate them, Hopkins said in a 1906 lecture that "unsuspected dietetic factors", other than calories, protein, and minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

, are needed to prevent deficiency diseases. In 1907, Stephen M. Babcock

Stephen Moulton Babcock (22 October 1843 – 2 July 1931) was an American agricultural chemist. He is best known for developing the Babcock test, used to determine butterfat content in milk and cheese processing, and for the single-grain experime ...

and Edwin B. Hart started the cow feeding, single-grain experiment

The single-grain experiment was an experiment carried out at the University of Wisconsin–Madison from May 1907 to 1911. The experiment tested if cows could survive on a single type of grain. The experiment would lead to the development of modern ...

, which took nearly four years to complete.

In 1912 Casimir Funk

Kazimierz Funk (; February 23, 1884 – November 19, 1967), commonly anglicized as Casimir Funk, was a Polish-American biochemist generally credited with being among the first to formulate (in 1912) the concept of vitamins, which he called "vita ...

coined the term vitamin

A vitamin is an organic molecule (or a set of molecules closely related chemically, i.e. vitamers) that is an essential micronutrient that an organism needs in small quantities for the proper functioning of its metabolism. Essential nutrie ...

to label a vital factor in the diet: from the words "vital" and "amine", because these unknown substances preventing scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra

Pellagra is a disease caused by a lack of the vitamin niacin (vitamin B3). Symptoms include inflamed skin, diarrhea, dementia, and sores in the mouth. Areas of the skin exposed to either sunlight or friction are typically affected first. Over t ...

, and were thought then to derive from ammonia. In 1913 Elmer McCollum

Elmer Verner McCollum (March 3, 1879 – November 15, 1967) was an American biochemist known for his work on the influence of diet on health.Kruse, 1961. McCollum is also remembered for starting the first rat colony in the United States to be us ...

discovered the first vitamins, fat-soluble vitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin and an essential nutrient for humans. It is a group of organic compounds that includes retinol, retinal (also known as retinaldehyde), retinoic acid, and several provitamin A carotenoids (most notably bet ...

and water-soluble vitamin B

B vitamins are a class of water-soluble vitamins that play important roles in cell metabolism and synthesis of red blood cells. Though these vitamins share similar names (B1, B2, B3, etc.), they are chemically distinct compounds that often coexist ...

(in 1915; later identified as a complex of several water-soluble vitamins) and named vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits and vegetables, also sold as a dietary supplement and as a topical 'serum' ingredient to treat melasma (dark pigment spots) ...

as the then-unknown substance preventing scurvy. Lafayette Mendel

Lafayette Benedict Mendel (February 5, 1872 – December 9, 1935) was an American biochemist known for his work in nutrition, with longtime collaborator Thomas B. Osborne, including the study of Vitamin A, Vitamin B, lysine and tryptophan.

...

(1872-1935) and Thomas Osborne (1859–1929) also performed pioneering work on vitamins A and B.

In 1919, Sir Edward Mellanby

Sir Edward Mellanby (8 April 1884 – 30 January 1955) was a British biochemist and nutritionist who discovered vitamin D and its role in preventing rickets in 1919.

Education

Mellanby was born in West Hartlepool, the son of a shipyard owner, ...

incorrectly identified rickets

Rickets is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children, and is caused by either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stunted growth, bone pain, large forehead, and trouble sleeping. Complications may ...

as a vitamin A deficiency because he could cure it in dogs with cod liver oil.vitamin E

Vitamin E is a group of eight fat soluble compounds that include four tocopherols and four tocotrienols. Vitamin E deficiency, which is rare and usually due to an underlying problem with digesting dietary fat rather than from a diet low in vitami ...

as essential for rat pregnancy, originally calling it "food factor X" until 1925.

In 1925 Hart discovered that iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

absorption requires trace amounts of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

. In 1927 Adolf Otto Reinhold Windaus

Adolf Otto Reinhold Windaus (; 25 December 1876 – 9 June 1959) was a German chemist who won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1928 for his work on sterols and their relation to vitamins. He was the doctoral advisor of Adolf Butenandt who also won ...

synthesized vitamin D, for which he won the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in Chemistry in 1928. In 1928 Albert Szent-Györgyi

Albert Imre Szent-Györgyi de Nagyrápolt ( hu, nagyrápolti Szent-Györgyi Albert Imre; September 16, 1893 – October 22, 1986) was a Hungarian biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937. He is credited with fi ...

isolated ascorbic acid

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits and vegetables, also sold as a dietary supplement and as a topical 'serum' ingredient to treat melasma (dark pigment spots) an ...

, and in 1932 proved that it is vitamin C by preventing scurvy. In 1935 he synthesized it, and in 1937 won a Nobel Prize for his efforts. Szent-Györgyi concurrently elucidated much of the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle (CAC)—also known as the Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reactions to release stored energy through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins ...

.

In the 1930s, William Cumming Rose

William Cumming Rose (April 4, 1887 – September 25, 1985) was an American biochemist and nutritionist. He discovered the amino acid threonine, and his research determined the necessity for essential amino acids in diet and the minimum daily re ...

identified essential amino acid

An essential amino acid, or indispensable amino acid, is an amino acid that cannot be synthesized from scratch by the organism fast enough to supply its demand, and must therefore come from the diet. Of the 21 amino acids common to all life form ...

s, necessary protein components that the body cannot synthesize. In 1935 Eric Underwood

Eric John Underwood AO, CBE (7 September 1905 – 19 August 1980) was an Australian scientist who pioneered research into sheep nutrition and wool production.

Personal life

Underwood was born in Harlington, Middlesex, England on 7 September 1 ...

and Hedley Marston independently discovered the necessity of cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...

. In 1936, Eugene Floyd DuBois showed that work and school performance are related to caloric intake. In 1938, Erhard Fernholz discovered the chemical structure of vitamin E.Paul Karrer

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

.Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

closed down its nutrition department after World War II because the subject seemed to have been completed between 1912 and 1944.

Institutionalization of nutritional science in the 1950s

''Nutritional science'' as a separate, independent science discipline was institutionalized in the 1950s. At the instigation of the British physiologist John Yudkin

John Yudkin Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry, FRSC (8 August 1910 – 12 July 1995) was a British physiology, physiologist and nutritional science, nutritionist, and the founding Professor of the Department of Nutrition at Queen Elizabe ...

at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

, the degrees Bachelor of Science and Master of Science in nutritional science were established. The first students were admitted in 1953, and in 1954 the Department of Nutrition was officially opened.[Davies, Louise (24 July 1995)]

"Obituary: John Yudkin"

''The Independent''. In Germany, institutionalization followed in November 1956, when Hans-Diedrich Cremer was appointed to the chair for human nutrition in Giessen. Over time, seven other universities with similar institutions followed in Germany. From the 1950s to 1970s, a focus of nutritional science was on dietary fat

In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specifically to triglycerides (triple e ...

and sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

. From the 1970s to the 1990s, attention was put on diet-related chronic diseases and Dietary supplement, supplementation.

See also

General

* Health

* Dieting

* Healthy diet

Substances

* Dietary supplement

* Food fortification

* Nutraceuticals

* Probiotic

* Prebiotic (nutrition)

Healthy eating advice and tools

* 5 A Day

* Canada's Food Guide

''Canada's Food Guide'' (french: Guide alimentaire canadien) is a nutrition guide produced by Health Canada. In 2007, it was reported to be the second most requested Canadian government publication, behind the Income Tax Forms. The Health Canada ...

* Food group

* Food guide pyramid

* Healthy eating pyramid

* MyPyramid

* Nutritional rating systems

* Nutrition scale

Types of food

* Diet food

* Fast food

* Functional food

* Junk food

* Food supplement

* Ultra-processed food

* Edible seaweed

Academic publishing

* ''Advances in Nutrition''

* ''Annual Review of Nutrition''

* ''The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition''

Biology

* Basal metabolic rate

* Bioenergetics

* Digestion

* Enzyme

Lists

* List of diets

* List of food additives

* List of illnesses related to poor nutrition

* List of life extension related topics

* List of macronutrients

* List of micronutrients

* List of publications in medicine#Nutrition, List of publications in nutrition

* List of unrefined sweeteners

* List of antioxidants in food, List of antioxidants

* List of phytochemicals in food, List of phytochemicals

Organizations

* Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

* American Society for Nutrition

The American Society for Nutrition (ASN) is an American society for professional researchers and practitioners in the field of nutrition. ASN publishes four journals in the field of nutrition. It has been criticized for its financial ties to the ...

* British Dietetic Association

* Food and Drug Administration

* Society for Nutrition Education

Professions

* Dietitian

* Nutritionist A nutritionist is a person who advises others on matters of food and nutrition and their impacts on health. Some people specialize in particular areas, such as sports nutrition, public health, or animal nutrition, among other disciplines. In many ...

* Food Studies

Further reading