Galápagos Islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Galápagos Islands ( es, Islas Galápagos) are an

The Galápagos Islands ( es, Islas Galápagos) are an

The islands are located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, off the west coast of South America. The majority of islands are also more broadly part of the South Pacific. The closest land mass is that of mainland

The islands are located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, off the west coast of South America. The majority of islands are also more broadly part of the South Pacific. The closest land mass is that of mainland

The 18 main islands (each having a land area at least 1 km2) of the archipelago (with their English names) shown alphabetically:

* Baltra (South Seymour) Island – Baltra is a small flat island located near the centre of the Galápagos. It was created by geological uplift. The island is very arid, and vegetation consists of salt bushes, prickly pear cacti and palo santo trees. Until 1986,

The 18 main islands (each having a land area at least 1 km2) of the archipelago (with their English names) shown alphabetically:

* Baltra (South Seymour) Island – Baltra is a small flat island located near the centre of the Galápagos. It was created by geological uplift. The island is very arid, and vegetation consists of salt bushes, prickly pear cacti and palo santo trees. Until 1986,  * Floreana (Charles or Santa María) Island – It was named after Juan José Flores, the first

* Floreana (Charles or Santa María) Island – It was named after Juan José Flores, the first  * Isabela (Albemarle) Island – This island was named in honor of Queen Isabella I of Castile. With an area of , it is the largest island of the Galápagos. Its highest point is Volcán Wolf, with an altitude of . The island's

* Isabela (Albemarle) Island – This island was named in honor of Queen Isabella I of Castile. With an area of , it is the largest island of the Galápagos. Its highest point is Volcán Wolf, with an altitude of . The island's  *

*  * San Cristóbal (Chatham) Island – It bears the name of the patron saint of seafarers, " St. Christopher". Its English name was given after

* San Cristóbal (Chatham) Island – It bears the name of the patron saint of seafarers, " St. Christopher". Its English name was given after  * Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island – Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish. It was originally named Norfolk Island by Cowley, but renamed after the British frigate HMS ''Indefatigable'' after her visit there in 1812. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Santa Cruz hosts the largest human population in the archipelago, the town of

* Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island – Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish. It was originally named Norfolk Island by Cowley, but renamed after the British frigate HMS ''Indefatigable'' after her visit there in 1812. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Santa Cruz hosts the largest human population in the archipelago, the town of

*

*

Although the islands are located on the equator, the

Although the islands are located on the equator, the

European discovery of the Galápagos Islands is recorded occurring on 10 March 1535, when the

European discovery of the Galápagos Islands is recorded occurring on 10 March 1535, when the

The first English captain to visit the Galápagos Islands was

The first English captain to visit the Galápagos Islands was

The first known permanent human resident on Galápagos was Patrick Watkins, an Irish sailor who was

The first known permanent human resident on Galápagos was Patrick Watkins, an Irish sailor who was  The second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' under

The second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' under

For a long time during the early 1900s and at least through 1929, a cash-strapped Ecuador had reached out for potential buyers of the islands to alleviate financial troubles at home. The US had repeatedly expressed its interest in buying the islands for military use as they were positioned strategically guarding the

For a long time during the early 1900s and at least through 1929, a cash-strapped Ecuador had reached out for potential buyers of the islands to alleviate financial troubles at home. The US had repeatedly expressed its interest in buying the islands for military use as they were positioned strategically guarding the

The islands are administered as Ecuador's

The islands are administered as Ecuador's

Options for air travel to the Galápagos are limited to two islands: San Cristobal (

Options for air travel to the Galápagos are limited to two islands: San Cristobal (

Though the first protective legislation for the Galápagos was enacted in 1930 and supplemented in 1936, it was not until the late 1950s that positive action was taken to control what was happening to the native flora and fauna. In 1955, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature organized a fact-finding mission to the Galápagos. Two years later, in 1957,

Though the first protective legislation for the Galápagos was enacted in 1930 and supplemented in 1936, it was not until the late 1950s that positive action was taken to control what was happening to the native flora and fauna. In 1955, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature organized a fact-finding mission to the Galápagos. Two years later, in 1957,

New 7 Wonders of the World: Live Ranking

The islands' biodiversity is under threat from several sources. The human population is growing at a rate of 8% per year (1995). Introduced species have caused damage, and in 1996 a US$5 million, five-year eradication plan commenced in an attempt to rid the islands of introduced species such as goats, rats, deer, and donkeys. Except for the rats, the project was essentially completed in 2006. Rats have only been eliminated from the smaller Galápagos Islands of Rábida and Pinzón.

Galápagos geology, with general information on the Galápagos Islands

{{DEFAULTSORT:Galapagos Islands *Islands Biosphere reserves of Ecuador Surfing locations in Ecuador Ecoregions of Ecuador Pacific islands of Ecuador Seabird colonies States and territories established in 1973 World Heritage Sites in Ecuador Tourist attractions in Galápagos Province Articles containing video clips Tropical Eastern Pacific

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of volcanic island

Geologically, a high island or volcanic island is an island of volcanic origin. The term can be used to distinguish such islands from low islands, which are formed from sedimentation or the uplifting of coral reefs (which have often form ...

s in the Eastern Pacific, located around the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can al ...

west of the mainland of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the souther ...

. They form the Galápagos Province

Galápagos () is a province of Ecuador in the country's Insular region, located approximately off the western coast of the mainland. The capital is Puerto Baquerizo Moreno.

The province administers the Galápagos Islands, a group of tiny vo ...

of the Republic of Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Ekua ...

, with a population of slightly over 33,000 (2020). The province is divided into the cantons of San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz, and Isabela, the three most populated islands in the chain. The Galápagos are famous for their large number of endemic species

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

, which were studied by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

in the 1830s and inspired his theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by means of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

. All of these islands are protected as part of Ecuador's Galápagos National Park

Galápagos National Park ( es, Parque Nacional Galápagos) was established in 1959. It began operation in 1968, and it is Ecuador's first national park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Park history

The government of Ecuador has designated ...

and Marine Reserve

A marine reserve is a type of marine protected area (MPA). An MPA is a section of the ocean where a government has placed limits on human activity. A marine reserve is a marine protected area in which removing or destroying natural or cultural ...

.

Thus far, there is no firm evidence that Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

or the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of South America reached the islands before their accidental discovery by Bishop Tomás de Berlanga in 1535. If some visitors did arrive, poor access to fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does incl ...

on the islands seems to have limited settlement. The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

similarly ignored the islands, although during the Golden Age of Piracy

The Golden Age of Piracy is a common designation for the period between the 1650s and the 1730s, when maritime piracy was a significant factor in the histories of the Caribbean, the United Kingdom, the Indian Ocean, North America, and West Afric ...

various pirates used the Galápagos as a base for raiding Spanish shipping along the Peruvian

Peruvians ( es, peruanos) are the citizens of Peru. There were Andean and coastal ancient civilizations like Caral, which inhabited what is now Peruvian territory for several millennia before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century; Peruvian p ...

coast. The goats

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a domesticated species of goat-antelope typically kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the a ...

and black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

and brown rat

The brown rat (''Rattus norvegicus''), also known as the common rat, street rat, sewer rat, wharf rat, Hanover rat, Norway rat, Norwegian rat and Parisian rat, is a widespread species of common rat. One of the largest muroids, it is a brown or ...

s introduced during this period greatly damaged the existing ecosystems of several islands. English sailors were chiefly responsible for exploring and mapping the area. Darwin's voyage on HMS ''Beagle'' was part of an extensive British survey of the coasts of South America. Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar language, Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechuan ...

, which won its independence from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

in 1822 and left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia ( Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1 ...

in 1830, formally occupied and claimed the islands on 12 February 1832 while the voyage was ongoing. José de Villamil

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacu ...

, the founder of the Ecuadorian Navy

The Ecuadorian Navy ( es, Armada del Ecuador) is an Ecuadorian entity responsible for the surveillance and protection of national maritime territory and has a personnel of 9,127 men to protect a coastline of 2,237 km which reaches far into t ...

, led the push to colonize and settle the islands,. gradually supplanting the English names of the major islands with Spanish ones. The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

built the islands' first airport as a base to protect the western approaches of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a Channel ( ...

in the 1930s. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, its facilities were transferred to Ecuador. With the growing importance of ecotourism

Ecotourism is a form of tourism involving responsible travel (using sustainable transport) to natural areas, conserving the environment, and improving the well-being of the local people. Its purpose may be to educate the traveler, to provide fund ...

to the local economy

Local purchasing is a preference to buy locally produced goods and services rather than those produced farther away. It is very often abbreviated as a positive goal, "buy local" or "buy locally', that parallels the phrase " think globally, act lo ...

, the airport modernized in the 2010s, using recycled materials for any expansion and shifting entirely to renewable energy sources to handle its roughly 300,000 visitors each year.

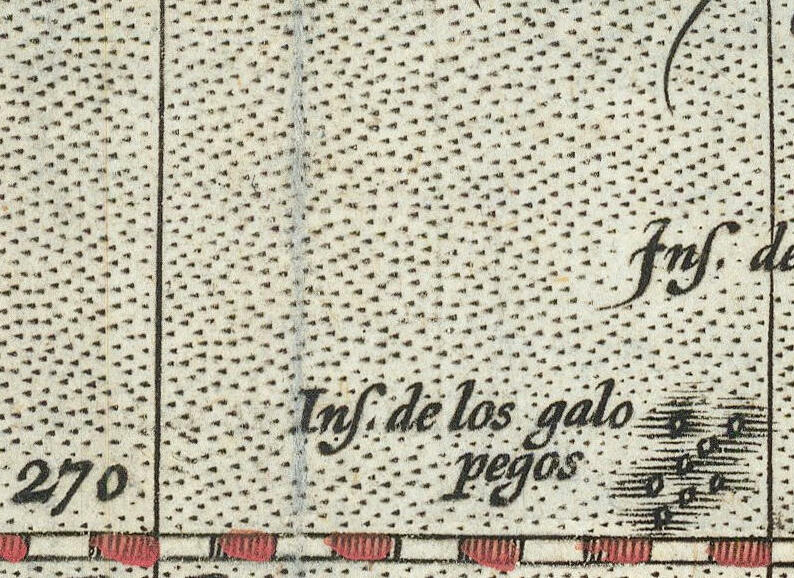

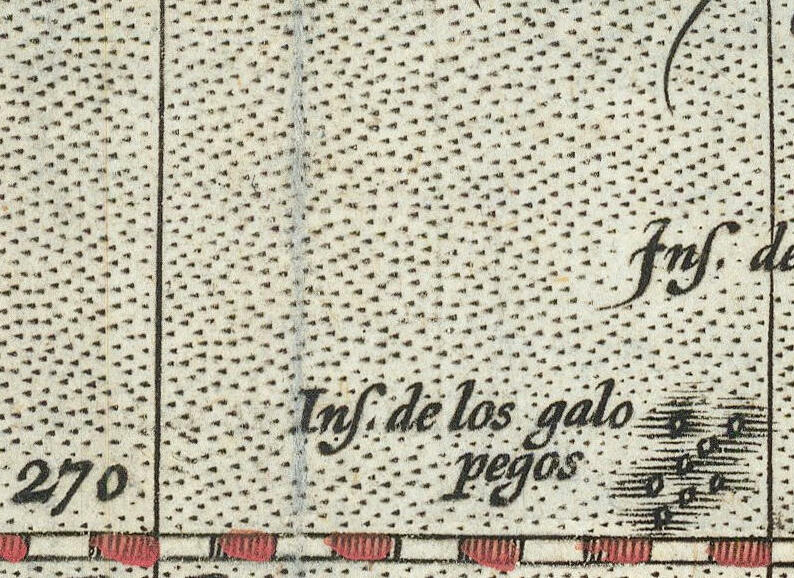

Names

The Galápagos or Galapagos Islands are named for their giant tortoises, which were more plentiful at the time of their discovery. TheSpanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

word derives from a pre-Roman Iberian word meaning "turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

", the meaning it still has in most dialects

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is ...

. Within Ecuadorian Spanish

Spanish is the most-widely spoken language in Ecuador, though great variations are present depending on several factors, the most important one being the geographical region where it is spoken. The three main regional variants are:

* Equatoria ...

, however, it is now also used to describe the islands' large tortoises. The islands' name is pronounced in most dialects of Spanish but by locals. (The accent over the second A does not change the name's pronunciation but moves the stress from the 3rd syllable to the 2nd.) It is usually read in British English

British English (BrE, en-GB, or BE) is, according to Lexico, Oxford Dictionaries, "English language, English as used in Great Britain, as distinct from that used elsewhere". More narrowly, it can refer specifically to the English language in ...

and in American English

American English, sometimes called United States English or U.S. English, is the set of varieties of the English language native to the United States. English is the most widely spoken language in the United States and in most circumstances ...

. The name is first attested as the Spanish/Latin hybrid ("Islands of the Turtles") on the map of the Americas in Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a Brabantian cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer, conventionally recognized as the creator of the first modern atlas, the '' Theatrum Orbis Terr ...

's '' Theater of the Lands of the World'' (), first published in 1570.

The islands were also previously known as the Enchanted Isles or Islands () from sailors' difficulty with the winds and currents around them; as the Ecuador Archipelago () or Archipelago of the Equator () following their settlement by Ecuador in 1832; and as the Colon or Columbus Archipelago () in 1892 upon the quadricentennial of Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

's first voyage.

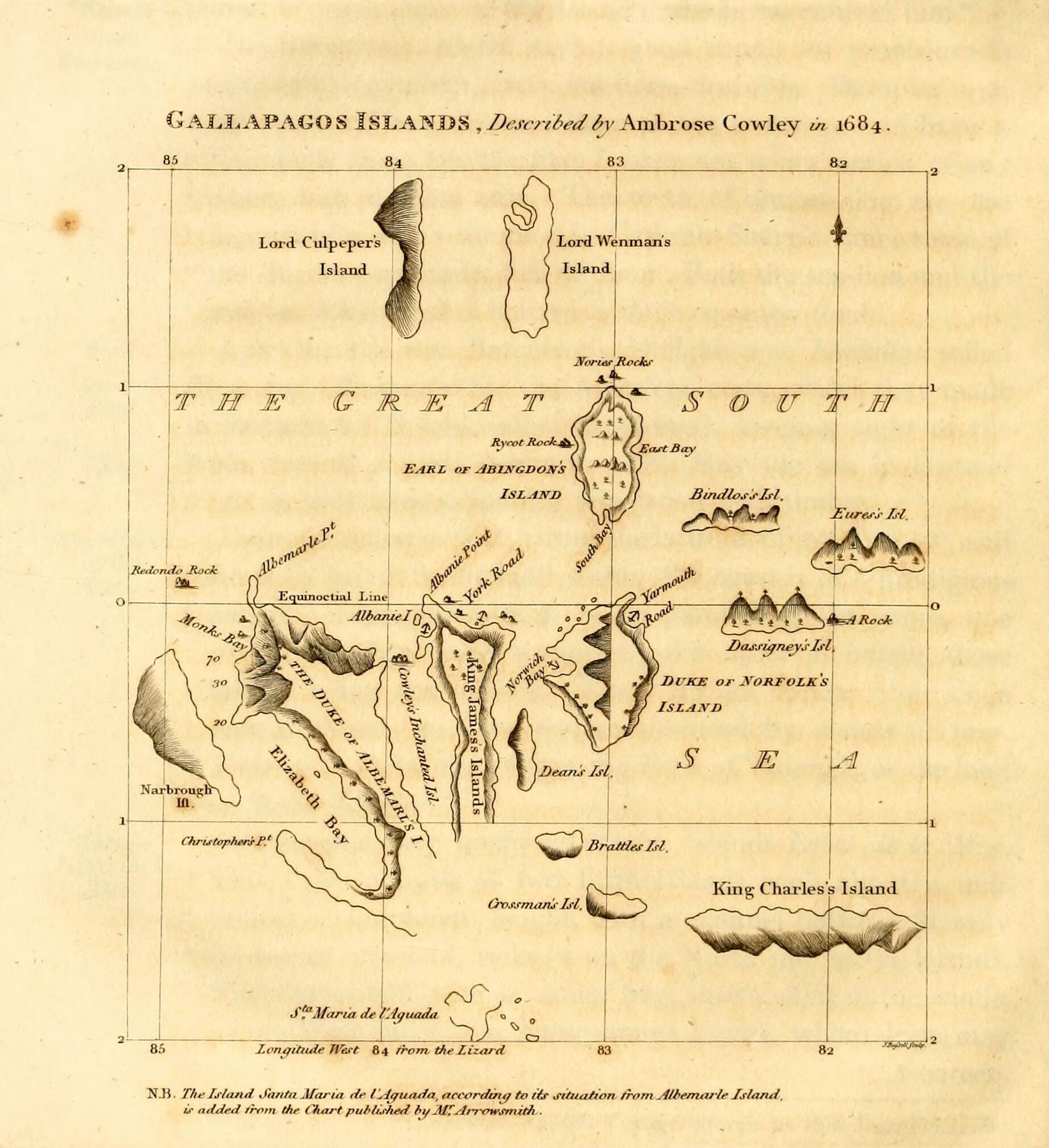

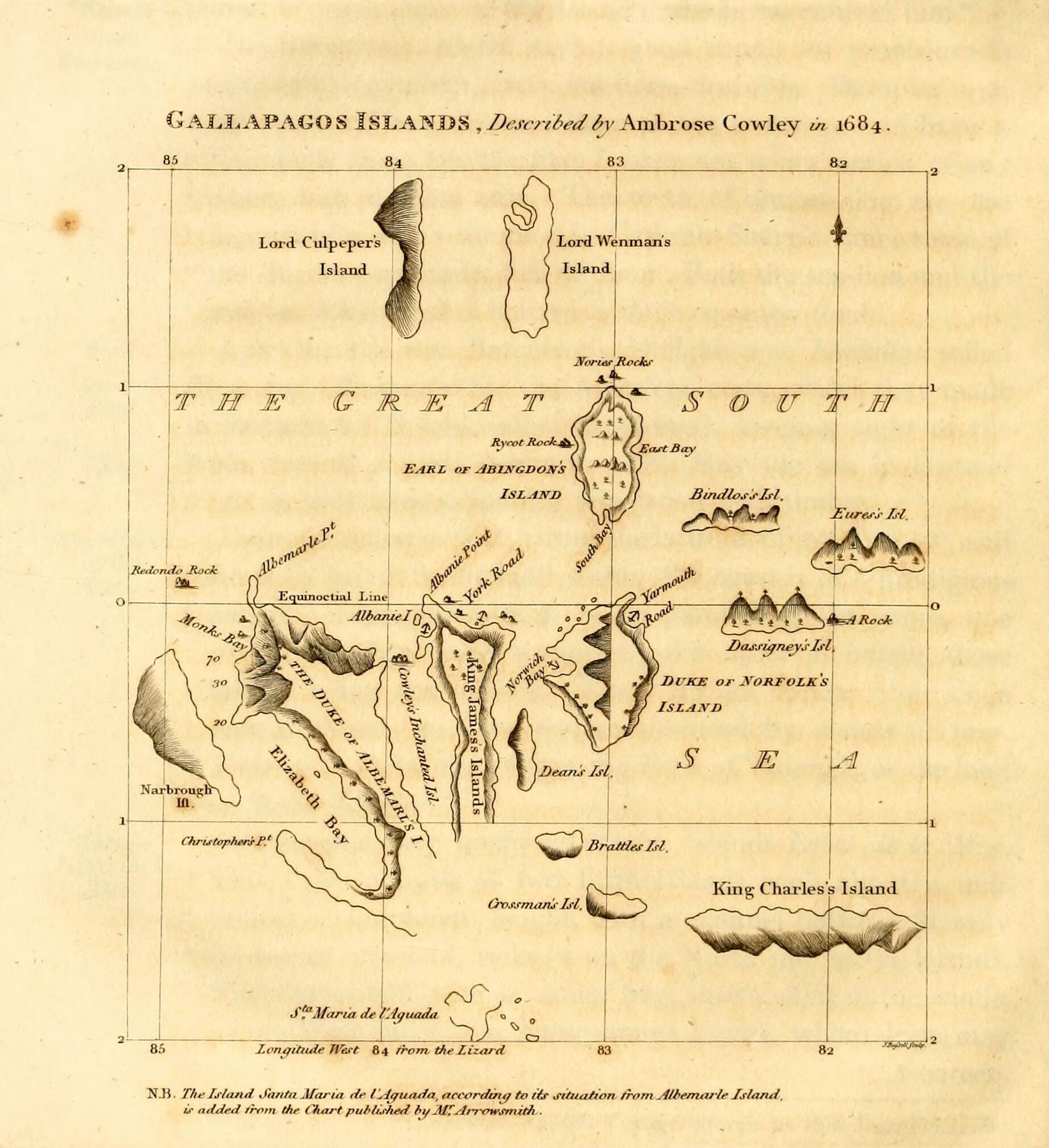

The islands were mapped by the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

buccaneer

Buccaneers were a kind of privateers or free sailors particular to the Caribbean Sea during the 17th and 18th centuries. First established on northern Hispaniola as early as 1625, their heyday was from the Restoration in 1660 until about 1688, ...

William Ambrosia Cowley in 1684 and by the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

James Colnett

James Colnett (1753 – 1 September 1806) was an officer of the British Royal Navy, an explorer, and a maritime fur trader. He served under James Cook during Cook's second voyage of exploration. Later he led two private trading expeditions that ...

in 1793. The names they chose to honour British kings, nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteri ...

, and naval officers

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent context ...

of their eras continued to be used for the major islands until recently and are still used for many of the smaller islets. The Spanish names have varied over time, but the current official names have gradually supplanted the English ones for most of the major islands.

Geology

Volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the Earth#Surface, surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the su ...

has been continuous on the Galápagos Islands for at least 20 million years, and perhaps even longer. The mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

beneath the east-ward moving Nazca Plate

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the ...

(51 km/myr

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago). ...

) has given rise to a 3-kilometre-thick platform under the island chain and seamount

A seamount is a large geologic landform that rises from the ocean floor that does not reach to the water's surface (sea level), and thus is not an island, islet or cliff-rock. Seamounts are typically formed from extinct volcanoes that rise a ...

s. Besides the Galápagos Archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

, other key tectonic features in the region include the Northern Galápagos Volcanic Province between the archipelago and the Galápagos Spreading Center

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a dive ...

(GSC) to the north at the boundary of the Nazca Plate

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the ...

and the Cocos Plate

The Cocos Plate is a young oceanic tectonic plate beneath the Pacific Ocean off the west coast of Central America, named for Cocos Island, which rides upon it. The Cocos Plate was created approximately 23 million years ago when the Farallon Plate ...

. This spreading center truncates into the East Pacific Rise

The East Pacific Rise is a mid-ocean rise (termed an oceanic rise and not a mid-ocean ridge due to its higher rate of spreading that results in less elevation increase and more regular terrain), a divergent tectonic plate boundary located alon ...

on the west and is bounded by the Cocos Ridge and Carnegie Ridge in the east. Furthermore, the Galápagos Hotspot

Hotspot, Hot Spot or Hot spot may refer to:

Places

* Hot Spot, Kentucky, a community in the United States

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Hot Spot (comics), a name for the DC Comics character Isaiah Crockett

* Hot Spot (Tra ...

is at the northern boundary of the Pacific Large Low Shear Velocity Province while the Easter Hotspot is on the southern boundary.

The Galápagos Archipelago is characterized by numerous contemporaneous volcanoes, some with plume magma sources, others from the asthenosphere

The asthenosphere () is the mechanically weak and ductile region of the upper mantle of Earth. It lies below the lithosphere, at a depth between ~ below the surface, and extends as deep as . However, the lower boundary of the asthenosphere is ...

, possibly due to the young and thin oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafi ...

. The GSC caused structural weaknesses in this thin lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

leading to eruptions forming the Galápagos Platform. Fernandina and Isabela in particular are aligned along these weaknesses. Lacking a well-defined rift zone

A rift zone is a feature of some volcanoes, especially shield volcanoes, in which a set of linear cracks (or rifts) develops in a volcanic edifice, typically forming into two or three well-defined regions along the flanks of the vent. Believed t ...

, the islands have a high rate of inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

prior to eruption. Sierra Negra on Isabela Island experienced a uplift between 1992 and 1998, most recent eruption in 2005, while Fernandina on Fernandina Island indicated an uplift of , most recent eruption in 2009. Alcedo on Isabela Island had an uplift of greater than 90 cm, most recent eruption in 1993. Additional characteristics of the Galápagos Archipelago are closer volcano spacing, smaller volcano sizes, and larger caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber ...

s. For instance, Isabela Island includes six major volcanoes, Ecuador, Wolf, Darwin, Alcedo, Sierra Negra and Cerro Azul, with most recent eruptions ranging from 1813 to 2008. The neighboring islands of Santiago and Fernandina last erupted in 1906 and 2009, respectively. Overall, the nine active volcanoes in the archipelago have erupted 24 times between 1961 and 2011. The shape of these volcanoes is tall and rounded as opposed wide and smooth in the Hawaiian Islands. The Galápagos's shape is due to the pattern of radial and circumferential fissure

A fissure is a long, narrow crack opening along the surface of Earth. The term is derived from the Latin word , which means 'cleft' or 'crack'. Fissures emerge in Earth's crust, on ice sheets and glaciers, and on volcanoes.

Ground fissure

A ...

, radial on the flanks, but circumferential near the caldera summits. It is the circumferential fissures which give rise to stacks of short lava flow

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

s.

The volcanoes at the west end of the archipelago are in general, taller, younger, have well developed calderas, and are mostly composed of tholeiitic basalt

The tholeiitic magma series is one of two main magma series in subalkaline igneous rocks, the other being the calc-alkaline series. A magma series is a chemically distinct range of magma compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma ...

, while those on the east are shorter, older, lack calderas, and have a more diverse composition. The ages of the islands, from west to east are 0.05 Ma for Fernandina, 0.65 Ma for Isabela, 1.10 Ma for Santiago, 1.7 Ma for Santa Cruz, 2.90 Ma for Santa Fe, and 3.2 Ma for San Cristobal. The calderas on Sierra Negra and Alcedo have active fault systems. The Sierra Negra fault is associated with a sill

Sill may refer to:

* Sill (dock), a weir at the low water mark retaining water within a dock

* Sill (geology), a subhorizontal sheet intrusion of molten or solidified magma

* Sill (geostatistics)

* Sill (river), a river in Austria

* Sill plate, a ...

below the caldera. The caldera on Fernandina experienced the largest basaltic volcano collapse in history, with the 1968 phreatomagmatic eruption

Phreatomagmatic eruptions are volcanic eruptions resulting from interaction between magma and water. They differ from exclusively magmatic eruptions and phreatic eruptions. Unlike phreatic eruptions, the products of phreatomagmatic eruptions cont ...

. Fernandina has also been the most active volcano since 1790, with recent eruptions in 1991, 1995, 2005, and 2009, and the entire surface has been covered in numerous flows since 4.3 Ka. The western volcanoes have numerous tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock ...

cones

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines co ...

.

Physical geography

The islands are located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, off the west coast of South America. The majority of islands are also more broadly part of the South Pacific. The closest land mass is that of mainland

The islands are located in the eastern Pacific Ocean, off the west coast of South America. The majority of islands are also more broadly part of the South Pacific. The closest land mass is that of mainland Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar language, Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechuan ...

, the country to which they belong, to the east.

The islands are found at the coordinates 1°40'N–1°36'S, 89°16'–92°01'W. Straddling the equator, islands in the chain are located in both the northern and southern hemispheres, with Volcán Wolf and Volcán Ecuador on Isla Isabela being directly on the equator. Española Island

Española Island ( Spanish: ''Isla Española'') is part of the Galápagos Islands. The English named it ''Hood Island'' after Viscount Samuel Hood. It is located in the extreme southeast of the archipelago and is considered, along with San ...

, the southernmost islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be perman ...

of the archipelago, and Darwin Island

Darwin Island (Spanish: ''Isla Darwin'') is among the smallest in the Galápagos Archipelago with an area of just . It is named in honour of English scientist Charles Darwin. With no dry landing sites, Darwin Island's main attractions are fo ...

, the northernmost one, are spread out over a distance of . The International Hydrographic Organization

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) is an intergovernmental organisation representing hydrography. , the IHO comprised 98 Member States.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ensure that the world's seas, oceans and navigable waters ...

(IHO) considers them wholly within the South Pacific Ocean, however. The Galápagos Archipelago consists of of land spread over of ocean. The largest of the islands, Isabela, measures and makes up close to three-quarters of the total land area of the Galápagos. Volcán Wolf on Isabela is the highest point, with an elevation of above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as '' orthometric heights''.

The ...

.

The group consists of 18 main islands, 3 smaller islands, and 107 rocks and islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be perman ...

s. The islands are located at the Galapagos Triple Junction. The archipelago is located on the Nazca Plate

The Nazca Plate or Nasca Plate, named after the Nazca region of southern Peru, is an oceanic tectonic plate in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin off the west coast of South America. The ongoing subduction, along the Peru–Chile Trench, of the ...

(a tectonic plate), which is moving east/southeast, diving under the South American Plate at a rate of about per year. It is also atop the Galápagos hotspot

The Galápagos hotspot is a volcanic hotspot in the East Pacific Ocean responsible for the creation of the Galápagos Islands as well as three major aseismic ridge systems, Carnegie, Cocos and Malpelo which are on two tectonic plates. The hotsp ...

, a place where the Earth's crust is being melted from below by a mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

, creating volcanoes. The first islands formed here at least 8 million and possibly up to 90 million years ago.

While the older islands have disappeared below the sea as they moved away from the mantle plume, the youngest islands, Isabela and Fernandina, are still being formed. In April 2009, lava from the volcanic island Fernandina started flowing both towards the island's shoreline and into the center caldera.

In late June 2018, Sierra Negra, one of five volcanoes on Isabela and one of the most active in the Galapagos archipelago, began erupting for the first time since 2005. Lava flows made their way to the coastline, prompting the evacuation of about fifty nearby residents and restricting tourist access.

Main islands

The 18 main islands (each having a land area at least 1 km2) of the archipelago (with their English names) shown alphabetically:

* Baltra (South Seymour) Island – Baltra is a small flat island located near the centre of the Galápagos. It was created by geological uplift. The island is very arid, and vegetation consists of salt bushes, prickly pear cacti and palo santo trees. Until 1986,

The 18 main islands (each having a land area at least 1 km2) of the archipelago (with their English names) shown alphabetically:

* Baltra (South Seymour) Island – Baltra is a small flat island located near the centre of the Galápagos. It was created by geological uplift. The island is very arid, and vegetation consists of salt bushes, prickly pear cacti and palo santo trees. Until 1986, Seymour Airport

Seymour Galapagos Ecological Airport (Spanish: ''Aeropuerto Ecológico Galápagos Seymour'') is an airport serving the island of Baltra, one of the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador.

Facilities

The airport became the world's first "green" air ...

was the only airport serving the Galápagos. Now, there are two airports which receive flights from the continent; the other is located on San Cristóbal Island. Private planes flying to Galápagos must fly to Baltra, as it is the only airport with facilities for private planes. On arriving in Baltra, all visitors are immediately transported by bus to one of two docks. The first dock is located in a small bay, where the boats cruising Galápagos await passengers. The second is a ferry dock, which connects Baltra to the island of Santa Cruz. During the 1940s, scientists decided to move 70 of Baltra's land iguanas to the neighboring North Seymour Island

North Seymour ( es, Isla Seymour Norte) is a small island near Baltra Island in the Galápagos Islands. It was formed by uplift of a submarine lava formation. The whole island is covered with low, bushy vegetation.

The island is named after an ...

as part of an experiment. This move proved unexpectedly useful when the native iguanas became extinct on Baltra as a result of the island's military occupation in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. During the 1980s, iguanas from North Seymour were brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station

#REDIRECT Charles Darwin Foundation

The Charles Darwin Foundation (Spanish: ''Fundación Charles Darwin'') was founded in 1959, under the auspices of UNESCO and the World Conservation Union. The Charles Darwin Research Station serves as headqu ...

as part of a breeding and repopulation project, and in the 1990s, land iguanas were reintroduced to Baltra. As of 1997, scientists counted 97 iguanas living on Baltra; 13 of which had hatched on the islands.

* Bartolomé (Bartholomew) Island – Bartolomé Island is a volcanic islet just off the east coast of Santiago Island in the Galápagos Islands group. it is one of the younger islands in the Galápagos archipelago. This island, and neighbouring Sulivan Bay on Santiago (James) island, are named after lifelong friend of Charles Darwin, Sir Bartholomew James Sulivan, who was a lieutenant aboard HMS ''Beagle''. Today Sulivan Bay is often misspelled Sullivan Bay. This island is one of the few that are home to the Galápagos penguin

The Galápagos penguin (''Spheniscus mendiculus'') is a penguin endemic to the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. It is the only penguin found north of the equator. Most inhabit Fernandina Island and the west coast of Isabela Island. The cool water ...

which is the only wild penguin species to live on the equator. The green turtle

The green sea turtle (''Chelonia mydas''), also known as the green turtle, black (sea) turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the family Cheloniidae. It is the only species in the genus ''Chelonia''. Its range exten ...

is another animal that resides on the island.

* Darwin (Culpepper) Island – This island is named after Charles Darwin. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Here fur seals, frigates, marine iguanas

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine repti ...

, swallow-tailed gulls, sea lions, whales, marine turtles, and red-footed and Nazca boobies can be seen. The remnants of Darwin's Arch, a natural rock arch which would at one time have been part of this larger structure, are located less than a kilometre from the main Darwin Island, and it was a landmark well known to the island's few visitors. It collapsed in May 2021. The two remaining stumps are now nicknamed the "Pillars of Evolution".

* Española (Hood) Island – Its name was given in honor of Spain. It also is known as ''Hood'', after Viscount Samuel Hood. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Española is the oldest island at around 3.5 million years, and the southernmost in the group. Due to its remote location, Española has a large number of endemic species. It has its own species of lava lizard, mockingbird, and Galápagos tortoise

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a species of very large tortoise in the genus ''Chelonoidis'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). It comprises 15 subspecies (13 ...

. Española's marine iguanas

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine repti ...

exhibit a distinctive red coloration change between the breeding season. Española is the only place where the waved albatross

The waved albatross (''Phoebastria irrorata''), also known as Galapagos albatross,Remsen Jr., J.V. (2008) is the only member of the family Diomedeidae located in the tropics. When they forage, they follow a straight path to a single site off the ...

nests. Some of the birds have attempted to breed on Genovesa (Tower) Island, but unsuccessfully. Española's steep cliffs serve as the perfect runways for these birds, which take off for their ocean feeding grounds near the mainland of Ecuador and Peru. Española has two visitor sites. Gardner Bay is a swimming and snorkelling site, and offers a great beach. Punta Suarez has migrant, resident, and endemic wildlife, including brightly colored marine iguana

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine repti ...

s, Española lava lizards, hood mockingbirds, swallow-tailed gull

The swallow-tailed gull (''Creagrus furcatus'') is an equatorial seabird in the gull family, Laridae. It is the only species in the genus ''Creagrus'', which derives from the Latin ''Creagra'' and the Greek ''kreourgos'' which means butcher, al ...

s, blue-footed boobies, Nazca boobies

The Nazca booby (''Sula granti'') is a large seabird of the booby family, Sulidae, native to the eastern Pacific. First described by Walter Rothschild in 1902, it was long considered a subspecies of the masked booby until recognised as distinc ...

, red-billed tropicbird

The red-billed tropicbird (''Phaethon aethereus'') is a tropicbird, one of three closely related species of seabird of tropical oceans. Superficially resembling a tern in appearance, it has mostly white plumage with some black markings on the w ...

s, Galápagos hawks, three species of Darwin's finches, and the waved albatross.

* Fernandina (Narborough) Island – The name was given in honor of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, who sponsored the voyage of Columbus. Fernandina has an area of and a maximum altitude of . This is the youngest and westernmost island. On 13 May 2005, a new, very eruptive process began on this island, when an ash and water vapor cloud rose to a height of and lava flows descended the slopes of the volcano on the way to the sea. Punta Espinosa is a narrow stretch of land where hundreds of marine iguanas gather, largely on black lava rocks. The famous flightless cormorant

The flightless cormorant (''Nannopterum harrisi''), also known as the Galapagos cormorant, is a cormorant endemic to the Galapagos Islands, and an example of the highly unusual fauna there. It is unique in that it is the only known cormorant th ...

s inhabit this island, as do Galápagos penguin

The Galápagos penguin (''Spheniscus mendiculus'') is a penguin endemic to the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. It is the only penguin found north of the equator. Most inhabit Fernandina Island and the west coast of Isabela Island. The cool water ...

s, pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

s, Galápagos sea lion

The Galápagos sea lion (''Zalophus wollebaeki'') is a species of sea lion that lives and breeds on the Galápagos Islands and, in smaller numbers, on Isla de la Plata (Ecuador). Being fairly social, they are often spotted sun-bathing on sandy ...

s and Galápagos fur seal

The Galápagos fur seal (''Arctocephalus galapagoensis'') is one of eight seals in the genus ''Arctocephalus'' and one of nine seals in the subfamily ''Arctocephalinae.'' It is the smallest of all of the eared seals. They are endemic to the Galá ...

s. Different types of lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock ( magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or ...

flows can be compared, and the mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in several ...

forests can be observed.

* Floreana (Charles or Santa María) Island – It was named after Juan José Flores, the first

* Floreana (Charles or Santa María) Island – It was named after Juan José Flores, the first President of Ecuador

The president of Ecuador ( es, Presidente del Ecuador), officially called the Constitutional President of the Republic of Ecuador ( es, Presidente Constitucional de la República del Ecuador), serves as both the head of state and head of gover ...

, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. It is also called Santa Maria, after one of the caravels of Columbus. It has an area of and a maximum elevation of . It is one of the islands with the most interesting human history, and one of the earliest to be inhabited. Flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes are a type of wading bird in the family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only extant family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas (including the Caribbean) ...

s and green sea turtles nest (December to May) on this island. The ''patapegada'' or Galápagos petrel

The Galápagos petrel (''Pterodroma phaeopygia'') is one of the six endemic seabirds of the Galápagos Islands, Galápagos. Its scientific name derives from Ancient Greek: ''Pterodroma'' originates from ''pteron'' and ''dromos,'' meaning "wing" a ...

, a sea bird which spends most of its life away from land, is found here. At Post Office Bay, where 19th-century whalers kept a wooden barrel that served as a post office, mail could be picked up and delivered to its destinations, mainly Europe and the United States, by ships on their way home. At the "Devil's Crown", an underwater volcanic cone

Volcanic cones are among the simplest volcanic landforms. They are built by ejecta from a volcanic vent, piling up around the vent in the shape of a cone with a central crater. Volcanic cones are of different types, depending upon the nature ...

and coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secre ...

formations are found.

* Genovesa (Tower) Island – The name is derived from Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

, Italy, the birthplace of Christopher Columbus. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . This island is formed by the remaining edge of a large caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber ...

that is submerged. Its nickname of "the bird island" is clearly justified. At Darwin Bay, frigatebird

Frigatebirds are a family of seabirds called Fregatidae which are found across all tropical and subtropical oceans. The five extant species are classified in a single genus, ''Fregata''. All have predominantly black plumage, long, deeply forke ...

s and swallow-tailed gull

The swallow-tailed gull (''Creagrus furcatus'') is an equatorial seabird in the gull family, Laridae. It is the only species in the genus ''Creagrus'', which derives from the Latin ''Creagra'' and the Greek ''kreourgos'' which means butcher, al ...

s, the only nocturnal species of gull in the world, can be seen. Red-footed boobies

A booby is a seabird in the genus ''Sula'', part of the family Sulidae. Boobies are closely related to the gannets (''Morus''), which were formerly included in ''Sula''.

Systematics and evolution

The genus ''Sula'' was introduced by the Frenc ...

, noddy tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated as a subgroup of the family Laridae which includes gulls and skimmers and consists o ...

s, lava gulls, tropic birds, dove

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primaril ...

s, storm petrel

Storm-petrel may refer to one of two bird families, both in the order Procellariiformes, once treated as the same family.

The two families are:

*Northern storm petrels (''Hydrobatidae'') are found in the Northern Hemisphere, although some specie ...

s and Darwin finches are also in sight. Prince Philip's Steps is a bird-watching plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ...

with Nazca and red-footed boobies. There is a large Palo Santo forest.

* Isabela (Albemarle) Island – This island was named in honor of Queen Isabella I of Castile. With an area of , it is the largest island of the Galápagos. Its highest point is Volcán Wolf, with an altitude of . The island's

* Isabela (Albemarle) Island – This island was named in honor of Queen Isabella I of Castile. With an area of , it is the largest island of the Galápagos. Its highest point is Volcán Wolf, with an altitude of . The island's seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or " ...

shape is the product of the merging of six large volcanoes into a single land mass. On this island, Galápagos penguins, flightless cormorants, marine iguanas, pelicans and Sally Lightfoot crabs abound. At the skirts and calderas of the volcanoes of Isabela, land iguanas and Galápagos tortoises can be observed, as well as Darwin finches, Galápagos hawks, Galápagos doves and very interesting lowland vegetation. The third-largest human settlement of the archipelago, Puerto Villamil

Puerto Villamil is a small port village located on the southeastern edge of Isla Isabela in the Galapagos Islands. Of the 2,200 people who live on Isabela, the majority live in Puerto Villamil. The harbor is frequently full with sailboats, a ...

, is located at the southeastern tip of the island.

* Marchena (Bindloe) Island – Named after Fray Antonio Marchena, it has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Galapagos hawk

The Galápagos hawk (''Buteo galapagoensis'') is a large hawk endemic to most of the Galápagos Islands.

Description

The Galapágos hawk is similar in size to the red-tailed hawk (''Buteo jamaicensis'') and the Swainson's hawk (''Buteo swainso ...

s and sea lions inhabit this island, and it is home to the Marchena lava lizard, an animal endemic to Marchena

''Marchena'' is a genus of jumping spiders only found in the United States. Its only described species, ''M. minuta'', dwells on the barks of conifers along the west coast, especially California, Washington and Nevada.Maddison, Wayne. 199 ...

.

North Seymour Island

North Seymour ( es, Isla Seymour Norte) is a small island near Baltra Island in the Galápagos Islands. It was formed by uplift of a submarine lava formation. The whole island is covered with low, bushy vegetation.

The island is named after an ...

– Its name was given after an English nobleman, Lord Hugh Seymour

Vice-Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour (29 April 1759 – 11 September 1801) was a senior British Royal Navy officer of the late 18th century who was the fifth son of Francis Seymour-Conway, 1st Marquess of Hertford, and became known for being both a p ...

. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . This island is home to a large population of blue-footed boobies and swallow-tailed gulls. It hosts one of the largest populations of frigate birds. It was formed from geological uplift.

* Pinzón (Duncan) Island – Named after the Pinzón brothers, captains of the Pinta and Niña caravels, it has an area of and a maximum altitude of and has no permanent population. Home to giant Galápagos tortoise

The Galápagos tortoise or Galápagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a species of very large tortoise in the genus ''Chelonoidis'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America). It comprises 15 subspecies (13 ...

s of the subspecies Chelonoidis duncanensis and Galápagos sea lion

The Galápagos sea lion (''Zalophus wollebaeki'') is a species of sea lion that lives and breeds on the Galápagos Islands and, in smaller numbers, on Isla de la Plata (Ecuador). Being fairly social, they are often spotted sun-bathing on sandy ...

s, the island has no visitor facilities and a permit is required for legal visits.

* Pinta (Louis) Island – Named after the Pinta caravel, it has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Sea lions, Galápagos hawks, giant tortoises, marine iguanas, and dolphins can be seen here. Pinta Island was home to the last remaining Pinta tortoise, called Lonesome George

Lonesome George ( es, Solitario George or , 1910 – June 24, 2012) was a male Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger abingdonii'') and the last known individual of the subspecies. In his last years, he was known as the rarest creat ...

. He was moved from Pinta Island to the Charles Darwin Research Station

#REDIRECT Charles Darwin Foundation

The Charles Darwin Foundation (Spanish: ''Fundación Charles Darwin'') was founded in 1959, under the auspices of UNESCO and the World Conservation Union. The Charles Darwin Research Station serves as headqu ...

on Santa Cruz Island, where scientists attempted to breed from him. However, Lonesome George died in June 2012 without producing any offspring.

* Rábida (Jervis) Island – It bears the name of the convent of Rábida, where Columbus left his son during his voyage to the Americas. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . The high amount of iron contained in the lava at Rábida gives it a distinctive red colour. White-cheeked pintail ducks live in a saltwater lagoon close to the beach, where brown pelicans and boobies have built their nests. Until recently, flamingos were also found in the lagoon, but they have since moved on to other islands, likely due to a lack of food on Rábida. Nine species of finches have been reported in this island.

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

. It has an area of and its highest point rises to . This is the first island in the Galápagos Archipelago Charles Darwin visited during his voyage on the ''Beagle''. This island hosts frigate birds, sea lions, giant tortoises, blue- and red-footed boobies

A booby is a seabird in the genus ''Sula'', part of the family Sulidae. Boobies are closely related to the gannets (''Morus''), which were formerly included in ''Sula''.

Systematics and evolution

The genus ''Sula'' was introduced by the Frenc ...

, tropicbirds, marine iguana

The marine iguana (''Amblyrhynchus cristatus''), also known as the sea iguana, saltwater iguana, or Galápagos marine iguana, is a species of iguana found only on the Galápagos Islands (Ecuador). Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine repti ...

s, dolphins and swallow-tailed gull

The swallow-tailed gull (''Creagrus furcatus'') is an equatorial seabird in the gull family, Laridae. It is the only species in the genus ''Creagrus'', which derives from the Latin ''Creagra'' and the Greek ''kreourgos'' which means butcher, al ...

s. Its vegetation includes ''Calandrinia galapagos'', ''Lecocarpus darwinii'', and trees such as ''Lignum vitae''. The largest freshwater lake in the archipelago, Laguna El Junco, is located in the highland

Highlands or uplands are areas of high elevation such as a mountainous region, elevated mountainous plateau or high hills. Generally speaking, upland (or uplands) refers to ranges of hills, typically from up to while highland (or highlands) is ...

s of San Cristóbal. The capital of the province of Galápagos is Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, which lies at the southern tip of the island, and is close to San Cristóbal Airport

San Cristóbal Airport is an airport on the island of San Cristóbal, in the Galápagos Islands of Ecuador. The airport is on the southwestern end of the island, with rising terrain to the northeast. Approaches to both runways are over the ocean ...

.

* Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island – Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish. It was originally named Norfolk Island by Cowley, but renamed after the British frigate HMS ''Indefatigable'' after her visit there in 1812. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Santa Cruz hosts the largest human population in the archipelago, the town of

* Santa Cruz (Indefatigable) Island – Given the name of the Holy Cross in Spanish. It was originally named Norfolk Island by Cowley, but renamed after the British frigate HMS ''Indefatigable'' after her visit there in 1812. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Santa Cruz hosts the largest human population in the archipelago, the town of Puerto Ayora

Puerto Ayora is a town in central Galápagos, Ecuador. Located on the southern shore of Santa Cruz Island, it is the seat of Santa Cruz Canton. The town is named in honor of Isidro Ayora, an Ecuadorian president. The town is sometimes mistakenly ...

. The Charles Darwin Research Station

#REDIRECT Charles Darwin Foundation

The Charles Darwin Foundation (Spanish: ''Fundación Charles Darwin'') was founded in 1959, under the auspices of UNESCO and the World Conservation Union. The Charles Darwin Research Station serves as headqu ...

and the headquarters of the Galápagos National Park Service are located here. The GNPS and CDRS operate a tortoise breeding centre here, where young tortoises are hatched, reared, and prepared to be reintroduced to their natural habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

. The Highlands of Santa Cruz offer exuberant flora, and are famous for the lava tunnels. Large tortoise populations are found here. Black Turtle Cove is a site surrounded by mangroves, which sea turtles, rays and small sharks sometimes use as a mating area. Cerro Dragón, known for its flamingo lagoon, is also located here, and along the trail one may see land iguanas foraging.

* Santa Fe (Barrington) Island – Named after a city in Spain, it has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Santa Fe hosts a forest of Opuntia

''Opuntia'', commonly called prickly pear or pear cactus, is a genus of flowering plants in the cactus family Cactaceae. Prickly pears are also known as ''tuna'' (fruit), ''sabra'', '' nopal'' (paddle, plural ''nopales'') from the Nahuatl word ...

cactus

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Gre ...

, which are the largest of the archipelago, and Palo Santo. Weathered cliffs provide a haven for swallow-tailed gulls, red-billed tropic birds and shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds in the petrel family Procellariidae. They have a global marine distribution, but are most common in temperate and cold waters, and are pelagic outside the breeding season.

Description

These t ...

petrels. Santa Fe species of land iguanas are often seen, as well as lava lizards.

* Santiago (San Salvador, James) Island – Its name is equivalent to Saint James in English; it is also known as San Salvador, after the first island discovered by Columbus in the Caribbean Sea. This island has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Marine iguanas, sea lions, fur seals, land and sea turtles, flamingo

Flamingos or flamingoes are a type of wading bird in the family Phoenicopteridae, which is the only extant family in the order Phoenicopteriformes. There are four flamingo species distributed throughout the Americas (including the Caribbean) ...

s, dolphins and sharks are found here. Pigs and goats, which were introduced by humans to the islands and have caused great harm to the endemic species, have been eradicated (pigs by 2002; goats by the end of 2006). Darwin finches and Galápagos hawks are usually seen, as well as a colony of fur seals. At Sulivan Bay, a recent (around 100 years ago) pahoehoe lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock ( magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or ...

flow can be observed.

* Wolf (Wenman) Island – This island was named after the German geologist Theodor Wolf. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . Here, fur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family ''Otariidae''. They are much more closely related to sea lions than Earless seal, true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), r ...

s, frigatebirds, Nazca and red-footed boobies, marine iguanas, sharks, whales, dolphins and swallow-tailed gulls can be seen. The most famous resident is the vampire finch

The vampire ground finch (''Geospiza septentrionalis'') is a small bird native to the Galápagos Islands. It was considered a very distinct subspecies of the sharp-beaked ground finch (''Geospiza difficilis'') endemic to Wolf and Darwin Islands ...

, which feeds partly on blood pecked from other birds, and is only found on this island.

Minor islands

*

* Daphne Major

Daphne Major is a volcanic island just north of Santa Cruz Island and just west of the Baltra Airport in the Archipelago of Colón, commonly known as the Galápagos Islands. It consists of a tuff crater, devoid of trees, whose rim rises above the ...

– A small island directly north of Santa Cruz and directly west of Baltra, this very inaccessible island appears, though unnamed, on Ambrose Cowley's 1684 chart. It is important as the location of multidecade finch population studies by Peter and Rosemary Grant

Peter Raymond Grant (born October 26, 1936) and Barbara Rosemary Grant (born October 8, 1936) are a British married couple who are evolutionary biologists at Princeton University. Each currently holds the position of emeritus professor. They ...

.

* South Plaza Island () – It is named in honor of a former president of Ecuador, General Leónidas Plaza

Leónidas Plaza y Gutiérrez de Caviedes (18 April 1865 – 17 November 1932) was an Ecuadorian politician who was the President of Ecuador from 1 September 1901 to 31 August 1905 and again from 1 September 1912 to 31 August 1916.

He was the so ...

. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of . The flora of South Plaza includes ''Opuntia

''Opuntia'', commonly called prickly pear or pear cactus, is a genus of flowering plants in the cactus family Cactaceae. Prickly pears are also known as ''tuna'' (fruit), ''sabra'', '' nopal'' (paddle, plural ''nopales'') from the Nahuatl word ...

'' cactus and ''Sesuvium

''Sesuvium'' is a genus of flowering plants in the ice plant family, Aizoaceae. The roughly eight species it contains are commonly known as sea-purslanes.

Selected species

* ''Sesuvium crithmoides'' Welw. – Tropical sea-purslane

* '' Se ...

'' plants, which form a reddish carpet on top of the lava formations. Iguanas (land, marine and some hybrids of both species) are abundant, and large numbers of birds can be observed from the cliffs at the southern part of the island, including tropic birds and swallow-tailed gulls.

* North Plaza Island - This island lies north of South Plaza Island.

* Nameless Island – A small islet used mostly for scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chri ...

.

* Roca Redonda

Roca Redonda is a flat-topped, steep-sided islet located roughly northwest of the island of Isabela, in the Galápagos Islands of Ecuador. It measures long and wide with a maximum elevation of . Its isolation and inaccessibility coupled with i ...

– An islet approximately northwest of Isabela. Herman Melville devotes the third and fourth sketches of The Encantadas

"The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles" is a novella by American author Herman Melville. First published in '' Putnam's Magazine'' in 1854, it consists of ten philosophical "Sketches" on the Encantadas, or Galápagos Islands. It was collected in ''T ...

to describing this islet (which he calls "Rock Rodondo") and the view from it.

* Guy Fawkes Island - A small island of the coast of Santa Cruz. It is an island group composed of two crescent-shaped islets—North Guy Fawkes I. (I. Guy Fawkes Norte) and South Guy Fawkes I. (I. Guy Fawkes Sud)—and two rocks located northwest of Santa Cruz Island in the Galápagos Archipelago in Ecuador. The group is uninhabited but sometimes visited by scuba divers.

* Isla Beagle - This small island near to Santiago is largely uninhabited.

* Isla Caldwell - This island is near Floreana and has a length of 3.06 kilometers.

* Isla Campéon - Also known as Champion island, this islet is 1.64 kilometers in length and is one of the last refuges of the Floreana mockingbird.

* Isla Watson - This small islet is one of the many islets of Floreana island.

* Enderby Island

Enderby Island is part of New Zealand's uninhabited Auckland Islands archipelago, south of mainland New Zealand. It is situated just off the northern tip of Auckland Island, the largest island in the archipelago.

Geography and geology

Enderby ...

- Besides of Isla Campéon, this island is another place where the Floreana mockingbird lives.

* Gardner Island (Galapagos) - In the Galapagos Islands, there are two places called Gardner Island

Gardner Island is a largely ice-free island which lies about 3 km west of Broad Peninsula in the southern Vestfold Hills, in Prydz Bay on the Ingrid Christensen Coast of Princess Elizabeth Land, Antarctica. It has been designated an I ...

. There is one island near Española, and one island near Floreana.

* Mosqua Island - Mosquera is one of the smallest islands in the archipelago. Located between North Seymour and Baltra Islands, it consists of many coral reefs, making it a great site for practicing snorkel and observing the marine life.

Mosquera is also home to one of the largest colonies of sea lions in the Galapagos, and there have been occasional orca whale sightings around the islet. As is usual in the archipelago, the islet is shared by many seabirds, marine iguanas, blue-footed boobies and Sally Lightfoot crabs.

* Tortuga Island - Isla Tortuga is unique as the island is in the shape of a crescent. The island is actually a collapsed volcano that is a nesting location for a variety of seabirds such as Frigatebirds and the elusive Red-Billed Tropicbird, among others.

* Isla Los Hermanos - This is a small island off Isabela.

* Isla Sombrero Chino - One of the most recognizable of the Galapagos Islands, Sombrero Chino name means "Chinese Hat." It's easy to see why: this islet off of Santiago is shaped like an old-fashioned Chinaman's hat, a gently sloping cone rising out of the clear Galapagos water. Because of its distinctive shape, Sombrero Chino has fascinated visitors as long as they have been coming to Galapagos.

* Daphne Minor - It is very near Daphne Major

Daphne Major is a volcanic island just north of Santa Cruz Island and just west of the Baltra Airport in the Archipelago of Colón, commonly known as the Galápagos Islands. It consists of a tuff crater, devoid of trees, whose rim rises above the ...

and share a lot of similarities, as both are tuff cones devoid of trees.

* Las Tintoreras Islet - It is a group of seven small islets to the south of the bay of Puerto Villamil in the island of Isabela, that forms part of the archipelago and national park of the Galapagos Islands, including administratively in the Province Of Galapagos.

* Leon Dormido - This island is located of San Cristobal.Visually striking, the two rocks of Leon Dormindo, which means “Sleeping Lion,” soar to some 450 feet (140 meters) into the air. The mild current between the two rocks creates a hotbed habitat for an extremely diverse group of fish and mammals.

* Isla Cowley - This small island is very small, located off Isabela.

* Isla El Edén - Eden Island is a sliver of volcanic rock located along the northwest shore of the large Santa Cruz Island. Isla El Edén measures less than 2,000 square feet in diameter. Despite its small size of .01 square miles, it exhibits three distinct landscapes. One is flat, arid and barren. In the middle is a 233 foot cliff.

* Isla Albany - Albany Rock is a small crescent shaped islet located in the northwest of Santiago Island.

* Isla Onslow - It is one of the many islands near Floreana.

* Corona Del Diablo - Corona Del Diablo, also known as the Devil's Crown, located off of Floreana Island, not far from the shore, is a ring of uneven rocks that stick out of the water. Its name comes from the fact that it looks almost like an uncomfortable crown, that only the devil could wear.

Climate

Although the islands are located on the equator, the

Although the islands are located on the equator, the Humboldt Current

The Humboldt Current, also called the Peru Current, is a cold, low-salinity ocean current that flows north along the western coast of South America.Montecino, Vivian, and Carina B. Lange. "The Humboldt Current System: Ecosystem components and p ...

brings cold water to them, causing frequent drizzles during most of the year. The weather is regularly influenced by the El Niño

El Niño (; ; ) is the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (approximately between the International Date ...

events, which occur every 3 to 7 years and bring warmer sea surface temperature

Sea surface temperature (SST), or ocean surface temperature, is the ocean temperature close to the surface. The exact meaning of ''surface'' varies according to the measurement method used, but it is between and below the sea surface. Air ma ...

s, a rise in sea level, greater wave action, and a depletion of nutrients in the water. This cycle can greatly affect the precipitation from one year to another. At Charles Darwin Station, the precipitation during the month of March in the particularly wet year of 1969 was , but during March 1970 the next year it was only .

There is also a large range in precipitation from one place to another and across the islands' two main seasons. The archipelago is mainly characterized by a mixture of a tropical savanna climate

Tropical savanna climate or tropical wet and dry climate is a tropical climate sub-type that corresponds to the Köppen climate classification categories ''Aw'' (for a dry winter) and ''As'' (for a dry summer). The driest month has less than of ...

and a semi-arid climate

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi- ...

, transitioning to a tropical rainforest climate

A tropical rainforest climate, humid tropical climate or equatorial climate is a tropical climate sub-type usually found within 10 to 15 degrees latitude of the equator. There are some other areas at higher latitudes, such as the coast of southea ...

in the northwest. During the rainy season known as the from June to November, the temperature near the sea is around , a steady cool wind blows from south and southeast, frequent drizzles () for days, and dense fog conceals the islands. During the warm season from December to May, the average sea and air temperatures rise to around , there is no wind at all, and the sun shines apart from sporadic strong downpours. Weather also changes as altitude increases on the larger islands. Temperature decreases gradually with altitude, while precipitation increases due to the condensation of moisture from clouds on the slopes. This pattern of generally wet highlands and drier lowlands affects the plant life on the larger islands. The vegetation in the highlands tends to be green and lush, with tropical woodland in places. The lowland areas tend to have arid and semi-arid vegetation, with many thorny shrubs and cacti and areas of barren volcanic rock.

Some islands also fall within the rain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carri ...

of others during some seasons. During March 1969, the precipitation over Charles Darwin Station on the southern coast of Santa Cruz was , while on nearby Baltra Island the precipitation during the same month was only . This is because Baltra is located behind Santa Cruz when the prevailing winds are southerly, causing more moisture to fall on the Santa Cruz highlands.

The following table for the especially wet year of 1969 shows the variation of precipitation in different places of Santa Cruz Island

Santa Cruz Island ( Spanish: ''Isla Santa Cruz'', Chumash: ''Limuw'') is located off the southwestern coast of Ventura, California, United States. It is the largest island in California and largest of the eight islands in the Channel Islands ...

:

Ecology

Terrestrial

Most of the Galápagos is covered in semi-desert vegetation, including shrublands, grasslands, and dry forest. A few of the islands have high-elevation areas with cooler temperatures and higher rainfall, which are home to humid-climate forests and shrublands, and montane grasslands (''pampas'') at the highest elevations. There are about 500 species of nativevascular plant