Golden Age Of Aviation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sometimes dubbed the Golden Age of Aviation, the period in the

Sometimes dubbed the Golden Age of Aviation, the period in the  During this period

During this period

A number of nations operated airships between the two world wars, including Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, France, the Soviet Union and

A number of nations operated airships between the two world wars, including Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, France, the Soviet Union and  The US Navy explored the idea of using airships as

The US Navy explored the idea of using airships as

During the late 1920s and early 1930s the available power from aero engines increased significantly, making possible the adoption of the fast cantilever-wing

During the late 1920s and early 1930s the available power from aero engines increased significantly, making possible the adoption of the fast cantilever-wing

Many aviation firsts occurred during this period. Long-distance flights by pioneers such as

Many aviation firsts occurred during this period. Long-distance flights by pioneers such as

Sometimes dubbed the Golden Age of Aviation, the period in the

Sometimes dubbed the Golden Age of Aviation, the period in the history of aviation

The history of aviation extends for more than two thousand years, from the earliest forms of aviation such as kites and attempts at tower jumping to supersonic and hypersonic flight by powered, heavier-than-air jets.

Kite flying in Chin ...

between the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1918) and the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

(1939) was characterised by a progressive change from the slow wood-and-fabric biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

s of World War I to fast, streamlined metal monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

s, creating a revolution in both commercial and military aviation. By the outbreak of World War II in 1939 the biplane was all but obsolete. This revolution was made possible by the continuing development of lightweight aero engine

An aircraft engine, often referred to as an aero engine, is the power component of an aircraft propulsion system. Most aircraft engines are either piston engines or gas turbines, although a few have been rocket powered and in recent years many ...

s of increasing power. The jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and hybrid propulsion, the term ...

also began development during the 1930s but would not see operational use until later.

During this period

During this period civil aviation

Civil aviation is one of two major categories of flying, representing all non-military and non-state aviation, both private and commercial. Most of the countries in the world are members of the International Civil Aviation Organization and work ...

became widespread and many daring and dramatic feats took place such as round-the-world flights, air races and barnstorming

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in t ...

displays. Many commercial airlines were started during this period. Long-distance flights for the luxury traveller became possible for the first time; the early services used airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

s, but, after the Hindenburg disaster

The ''Hindenburg'' disaster was an airship accident that occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The German passenger airship LZ 129 ''Hindenburg'' caught fire and was destroyed during its attemp ...

, airships fell out of use and the flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

came to dominate.

In military aviation, the fast all-metal monoplane equipped with retractable landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for takeoff or landing. For aircraft it is generally needed for both. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, such as the Glenn L. Martin ...

— first placed into production by the Soviet Union with the Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 (russian: Поликарпов И-16) is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it was the world's first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to attain ope ...

of 1934 — emerged in such classic designs as the German Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

and the British Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

, which would go on to see service in the coming war.

Airships

A number of nations operated airships between the two world wars, including Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, France, the Soviet Union and

A number of nations operated airships between the two world wars, including Britain, the United States, Germany, Italy, France, the Soviet Union and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.

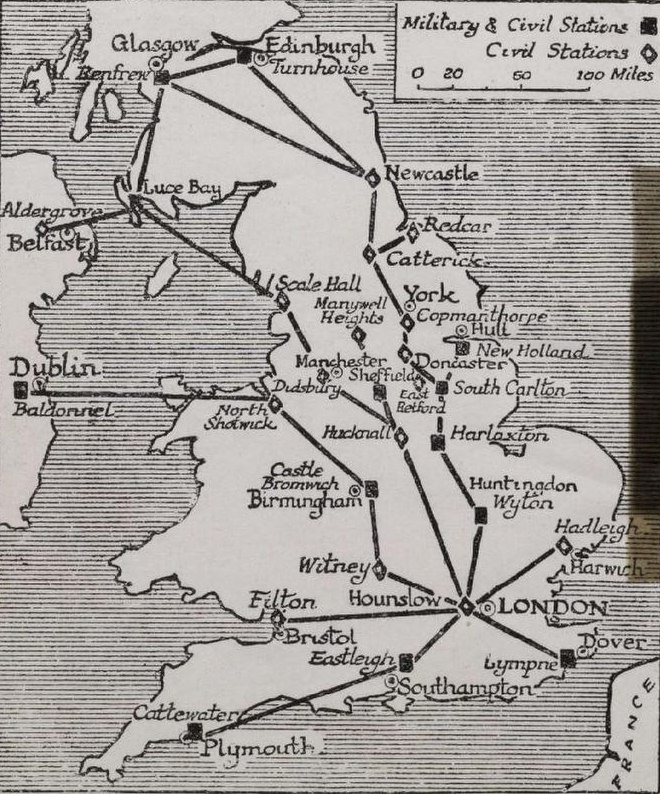

This period marked the great age of the airship. Before the First World War, pioneers such as the German Zeppelin company had begun passenger services, but the airships constructed in the years following were altogether larger and more famous. Large airships were also experimented with for military purposes, notably the American construction of two airborne aircraft carriers, but their large size made them vulnerable and the idea was dropped. This period also saw the introduction of non-flammable helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

as a lifting gas by the United States, while the more dangerous hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

continued to be used since the United States had the only sources of the gas at that time, and would not export it.

In 1919 the British airship ''R34 R34 may refer to:

* R34 (New York City Subway car)

* R34 (South Africa)

* HM Airship ''R.34'', a rigid airship of the Royal Air Force

* , a destroyer of the Royal Navy

* Nissan Skyline (R34), a mid-size car

* Nissan Skyline GT-R (R34), a sports ca ...

'' flew a double crossing of the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and in 1926 the Italian semi-rigid airship, ''Norge

Norge is Norwegian (bokmål), Danish and Swedish for Norway.

It may also refer to:

People

* Kaare Norge (born 1963), Danish guitarist

* Norge Luis Vera (born 1971), Cuban baseball player

Places

* 11871 Norge, asteroid

Toponyms:

*Norge, Oklah ...

'' was the first aircraft confirmed to fly over the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

.

The first American-built rigid airship, the , flew in 1923. The ''Shenandoah'' was the first to use helium, which was in such short supply that the one airship contained most of the world's reserves.

The US Navy explored the idea of using airships as

The US Navy explored the idea of using airships as airborne aircraft carrier

An airborne aircraft carrier is a type of mother ship aircraft which can carry, launch, retrieve and support other smaller parasite aircraft.

The only dedicated examples to have been built were airships, although existing heavier-than-air airc ...

s. Whereas the British had experimented with an aircraft "trapeze" on the ''R33'' many years before, the Americans built hangars into two new airships and even designed specialist airplanes for them. The and were the world's largest airships at the time, with each carrying four F9C Sparrowhawk

The Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk is a light 1930s biplane fighter aircraft that was carried by the United States Navy airships and . It is an example of a parasite fighter, a small airplane designed to be deployed from a larger aircraft such as ...

fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplan ...

in its hangar. Although successful, the idea was not taken further. By the time the Navy started to develop a sound doctrine for using these airships, both had been lost in accidents. More significantly, the seaplane had become more mature and was considered a better investment.

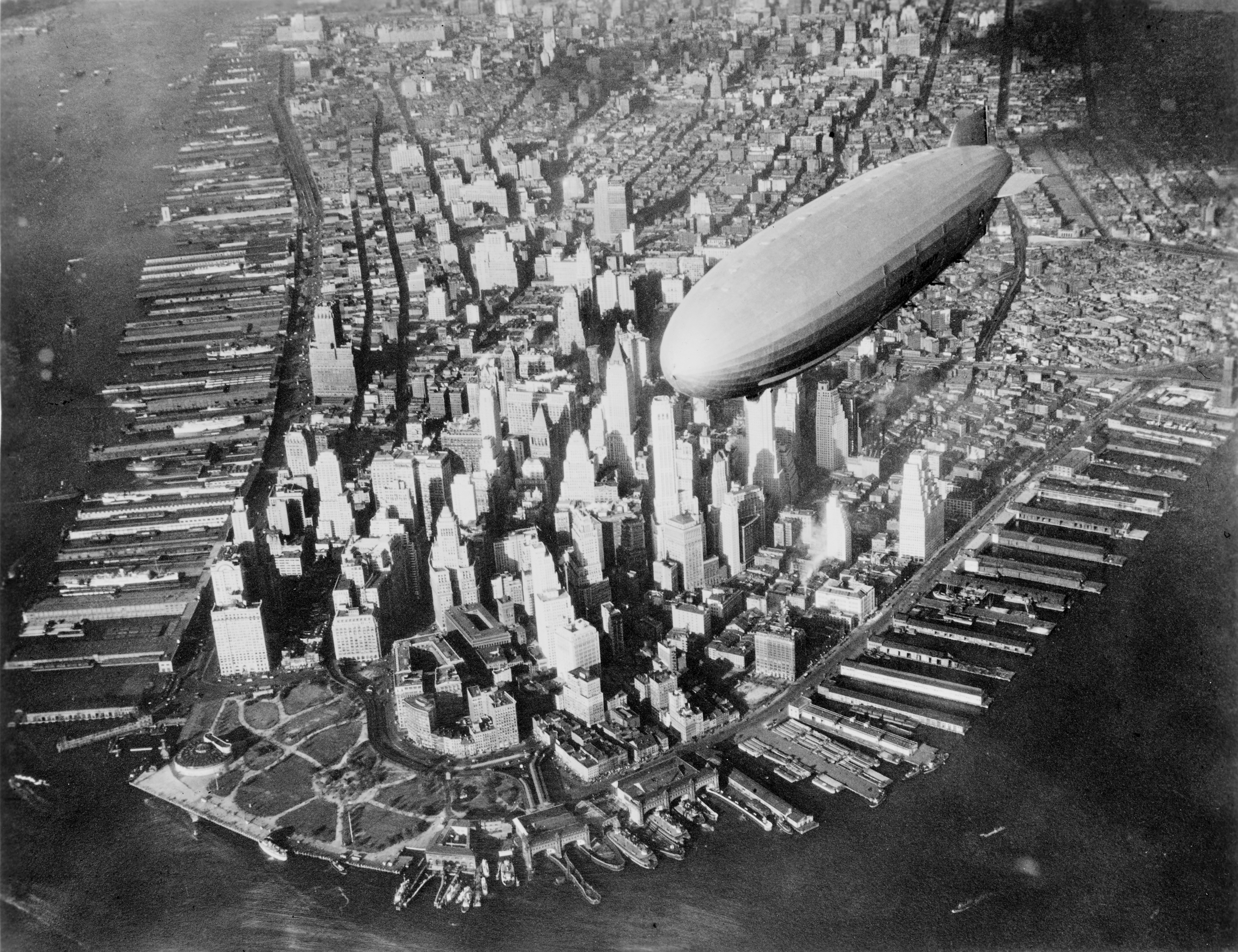

The Empire State Building

The Empire State Building is a 102-story Art Deco skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The building was designed by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon and built from 1930 to 1931. Its name is derived from "Empire State", the nickname of the st ...

, then the tallest building in the world, was completed in 1931 with a dirigible mast, in anticipation of passenger airship service.

The most famous airships today are the passenger-carrying rigid airships made by the German Zeppelin company, especially the '' Graf Zeppelin'' of 1928 and the '' Hindenburg'' of 1936.

The ''Graf Zeppelin'' was intended to stimulate interest in passenger airships, and was the largest airship that could be built in the company's existing shed. Its engines ran on ''blau gas

Blau gas (german: Blaugas) is an artificial illuminating gas, similar to propane, named after its inventor, Hermann Blau of Augsburg, Germany. Not or rarely used or produced today, it was manufactured by decomposing mineral oils in retorts by ...

'', similar to propane

Propane () is a three-carbon alkane with the molecular formula . It is a gas at standard temperature and pressure, but compressible to a transportable liquid. A by-product of natural gas processing and petroleum refining, it is commonly used a ...

, which was stored in large gas bags below the hydrogen cells. Since its density was similar to that of air, it avoided any weight change as fuel was used, and thus the need to vent hydrogen. The ''Graf Zeppelin'' became the first aircraft to fly all the way around the world.

Airship operations suffered a series of highly publicised fatal accidents, notably to the British R101

R101 was one of a pair of British rigid airships completed in 1929 as part of a British government programme to develop civil airships capable of service on long-distance routes within the British Empire. It was designed and built by an Air Mi ...

in 1930 and the German Hindenburg in 1937. Following the Hindenburg disaster, the age of the great airships was effectively over.

Aeronautical advances

During the late 1920s and early 1930s the available power from aero engines increased significantly, making possible the adoption of the fast cantilever-wing

During the late 1920s and early 1930s the available power from aero engines increased significantly, making possible the adoption of the fast cantilever-wing monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

, originally pioneered as far back as late 1915. The ability to handle the high mechanical stresses imposed by this advanced form of airframe design philosophy suited the all-metal aircraft construction techniques pioneered by some earlier designers, and the increasing availability of high strength-to-weight aluminum alloys — first used by Hugo Junkers

Hugo Junkers (3 February 1859 – 3 February 1935) was a German aircraft engineer and aircraft designer who pioneered the design of all-metal airplanes and flying wings. His company, Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (Junkers Aircraft and Mo ...

in 1916-17 as duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of '' Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its use as a tra ...

for his all-metal airframe designs — made it practical, allowing the earliest all-metal airliners like the Ford Trimotor

The Ford Trimotor (also called the "Tri-Motor", and nicknamed the "Tin Goose") is an American three-engined transport aircraft. Production started in 1925 by the companies of Henry Ford and ended on June 7, 1933, after 199 had been made. It w ...

designed by William Stout

William Stout (born September 18, 1949) is an American fantasy artist and illustrator with a specialization in paleoart, paleontological art. His paintings have been shown in over seventy exhibitions, including twelve one-man shows. He has worke ...

, and Junkers' own pioneering airliners like the Junkers F.13

The Junkers F 13 was the world's first all-metal transport aircraft, developed in Weimar Republic, Germany at the end of World War I. It was an advanced Cantilever#Aircraft, cantilever-wing monoplane, with enclosed accommodation for four passenge ...

to be built and accepted into service. When Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev (russian: Андрей Николаевич Туполев; – 23 December 1972) was a Russian Empire, Russian and later Soviet Union, Soviet aeronautical engineer known for his pioneering aircraft designs as Di ...

likewise used the Junkers firm's techniques for all-metal aircraft construction, his designs ranged in size to the enormous, 63 meter (206 ft) wingspan eight-engined Soviet ''Maksim Gorki'', the largest aircraft built anywhere before World War II.

The de Havilland DH.88 Comet

The de Havilland DH.88 Comet is a British two-seat, twin-engined aircraft built by the de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was developed specifically to participate in the 1934 England-Australia MacRobertson Air Race from the United Kingdom to A ...

racer of 1934 was one of the first designs to incorporate all the features of the modern fast monoplane, including; stressed-skin construction, a thin, clean, low-drag cantilever wing, retractable undercarriage

Undercarriage is the part of a moving vehicle that is underneath the main body of the vehicle. The term originally applied to this part of a horse-drawn carriage, and usage has since broadened to include:

*The landing gear of an aircraft.

*The ch ...

, landing flaps, variable-pitch propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

and enclosed cockpit

A cockpit or flight deck is the area, usually near the front of an aircraft or spacecraft, from which a Pilot in command, pilot controls the aircraft.

The cockpit of an aircraft contains flight instruments on an instrument panel, and the ...

. Unusually for such a highly stressed wing at that time it was still made of wood, with the thin stressed-skin design made possible by the appearance of new high-strength synthetic resin adhesives.

The Comet was powered by two race-tuned but otherwise standard production de Havilland Gipsy Six engines with a combined output of 460 hp (344 kW). This compares for example on the one hand to the single 180 hp engine fitted to the Junkers CL.I

The Junkers CL.I was a ground-attack aircraft developed in Germany during World War I. Its construction was undertaken by Junkers under the designation J 8 as proof of Hugo Junkers' belief in the monoplane, after his firm had been required by the ...

all-metal monoplane of 1918 and to the 1,172 hp Rolls-Royce Merlin

The Rolls-Royce Merlin is a British liquid-cooled V-12 piston aero engine of 27-litres (1,650 cu in) capacity. Rolls-Royce designed the engine and first ran it in 1933 as a private venture. Initially known as the PV-12, it was later ...

C development engine which powered the prototype Spitfire in 1936.

In the 1930s development of the jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and hybrid propulsion, the term ...

began in Germany and in England. In England Frank Whittle patented a design for a jet engine in 1930 and towards the end of the decade began developing an engine. In Germany Hans von Ohain patented his version of a jet engine in 1936 and began developing a similar engine. The two men were unaware of the other's work, and both Germany and Britain would go on to develop jet aircraft by the end of World War II. In Hungary, György Jendrassik

György Jendrassik or in English technical literature: George Jendrassik (1898 Budapest – 1954 London) was a Hungarian physicist and mechanical engineer.

Jendrassik completed his education at Budapest's József Technical University, then at the ...

began construction of the world's first turboprop engine.Green, W. and Swanborough, G.; "Plane Facts", ''Air Enthusiast'' Vol. 1 No. 1 (1971), Page 53.

Civil aviation

Many aviation firsts occurred during this period. Long-distance flights by pioneers such as

Many aviation firsts occurred during this period. Long-distance flights by pioneers such as Sir Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was b ...

, Alcock and Brown, Charles Lindbergh and Amy Johnson blazed a trail which new commercial airlines soon followed.

Many of these new routes had few facilities such as modern runways, and this era also became the age of the great flying boats such as the German Dornier Do X, American Sikorsky S-42 and British Short Empire, which could operate from any stretch of clear, calm water.

This period also saw the growth of barnstorming

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in t ...

and other aerobatic displays which produced a corps of skilled pilots who would contribute to military air forces during World War II on all sides of the conflict. Harry Bruno (1944) ''Wings over America: The Story of American Aviation'', Halcyon House, Garden City, New York.

Recreational gliding flourished, particularly in Germany through Rhön-Rossitten. In the US, the Schweizer brothers

Paul, William (Bill), and Ernest Schweizer were three brothers who started building gliders in 1930. In 1937, they formed the Schweizer Metal Aircraft Company. Their first commercial glider sale was an Schweizer SGU 1-7, SGU 1-7 Glider (sailplane ...

manufactured sport sailplanes to meet the new demand. Sailplanes continued to evolve through the 1930s and sport gliding became the main application of gliders.

Military aviation

In military aviation, the fast all-metal monoplane emerged slowly. During the 1920s the high-wing parasol monoplane vied with the traditionalbiplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

. It was not until the arrival of the American Boeing P-26 Peashooter in 1932 — nearly fifteen years after the first low-wing fighter to enter limited military service, the all-metal airframe Junkers D.I

The Junkers D.I (factory designation J 9) was a monoplane fighter aircraft produced in Germany late in World War I, significant for becoming the first all-metal fighter to enter service. The prototype, a private venture by Junkers named the J 7, ...

had entered service with the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' in 1918 — that the low-wing monoplane began to gain favour, reaching its classic form in such designs. These were pioneered in late 1933 by the Soviet Union with the Polikarpov I-16

The Polikarpov I-16 (russian: Поликарпов И-16) is a Soviet single-engine single-seat fighter aircraft of revolutionary design; it was the world's first low-wing cantilever monoplane fighter with retractable landing gear to attain ope ...

fighter, powered initially with an American Wright Cyclone nine-cylinder radial engine. Within only a few years after the I-16's first flights, the German Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

of 1935 and the British Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

of 1936 were also flying, powered by new and powerful liquid-cooled vee-twelve engines respectively from Daimler-Benz and Rolls-Royce. The rotary engines common in the First World War quickly fell out of favour, being replaced by more powerful stationary air-cooled radial engines such as the Pratt and Whitney Wasp series.

References

Inline citations

General references

*Almond, P.; ''Aviation: The early years'', Ullmann, 2013 edition. {{History of aviation Between Interwar period