Freedom Of Religious Expression on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest

Historically, ''freedom of religion'' has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while ''freedom of worship'' has been defined as freedom of individual action. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. An example commonly cited by scholars is the status of

Historically, ''freedom of religion'' has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while ''freedom of worship'' has been defined as freedom of individual action. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. An example commonly cited by scholars is the status of  In Antiquity, a

In Antiquity, a

Most Roman Catholic kingdoms kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the

Most Roman Catholic kingdoms kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the  The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards, and native Sicilians lived in harmony. Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1215–1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his Christian army and even into his personal bodyguards.

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards, and native Sicilians lived in harmony. Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1215–1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his Christian army and even into his personal bodyguards.

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the

Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston Common, 1 June 1660

' pp. 1–2. BiblioBazaar, LLC. As one of the four executed Quakers known as the

Symbol of Enduring Freedom

p. 19, Columbia Magazine, March 2010. Fifteen years later (1649), the

The French philosopher

The French philosopher

Wealth of Nations

, Penn State Electronic Classics edition, republished 2005, pp. 643–649

According to the Catholic Church in the

According to the Catholic Church in the

In Islam, apostasy is called "''ridda''" ("turning back") and is considered to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "''murtadd fitri''" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "''murtadd milli''" (apostate from the community).

In Islamic law (

In Islam, apostasy is called "''ridda''" ("turning back") and is considered to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "''murtadd fitri''" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "''murtadd milli''" (apostate from the community).

In Islamic law (

The

The

Models of Religious Freedom: Switzerland

the United States, and Syria by Analytical, Methodological, and Eclectic Representation, 375 ff. (Lit 2012).'', by Marcel Stüssi, research fellow at the University of Lucerne. * Associated Press (2002)

* [http://www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/FHPL_IndianRelFreAct.pdf American Indian Religious Freedom Act] (1978)

Policy Concerning Distribution of Eagle Feathers for Native American Religious

''Ban on Minarets: On the Validity of a Controversial Swiss Popular Initiative (2008), ''

, by Marcel Stuessi, research fellow at the University of Lucerne. * * * * *

Religion and Foreign Policy Initiative

Council on Foreign Relations.

The Complexity of Religion and the Definition of "Religion" in International Law

Harvard Human Rights Journal article from the President and Fellows of Harvard College (2003)

Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC)

U.S. State Department country reports

Institute for Global Engagement

Institute for Religious Freedom

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Religious Freedom and the Constitution by Christopher L. Eisgruber, Lawrence G. Sager

* [http://www.scientologyreligion.org/religious-freedom/what-is-freedom-of-religion/ What is Freedom of Religion? booklet]

Religious Freedom Resources from Mormon Newsroom

{{DEFAULTSORT:Religion Freedom of religion,

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

or belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to take i ...

in teaching, practice, worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity. It may involve one or more of activities such as veneration, adoration, praise, and praying. For many, worship is not about an emotion, it is more about a recognition ...

, and observance. It also includes the freedom to change one's religion or beliefs, "the right not to profess any religion or belief", or "not to practise a religion".

Freedom of religion is considered by many people and most nations to be a fundamental

Fundamental may refer to:

* Foundation of reality

* Fundamental frequency, as in music or phonetics, often referred to as simply a "fundamental"

* Fundamentalism, the belief in, and usually the strict adherence to, the simple or "fundamental" idea ...

human right

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

. In a country with a state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

, freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion, and does not persecute

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these terms ...

believers in other faiths (or those who have no faith).

Freedom of belief is different. It allows the right to believe what a person, group, or religion wishes, but it does not necessarily allow the right to practice the religion or belief openly and outwardly in a public manner, a central facet of religious freedom. Freedom of worship is uncertain but may be considered to fall between the two terms. The term "belief" is considered inclusive of all forms of irreligion

Irreligion or nonreligion is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and a ...

, including atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

, humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

, existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

or other schools of thought. Whether non-believers or humanists should be considered for the purposes of freedom of religion is a contested question in legal and constitutional contexts. Crucial in the consideration of this liberty is whether religious practices and motivated actions which would otherwise violate secular law should be permitted due to the safeguarding freedom of religion, such as (in American jurisprudence) ''United States v. Reynolds

''United States v. Reynolds'', 345 U.S. 1 (1953), is a landmark legal case in 1953 that saw the formal recognition of the state secrets privilege, a judicially recognized extension of presidential power.

Overview

Three employees of the Radio ...

'' or ''Wisconsin v. Yoder

''Wisconsin v. Jonas Yoder'', 406 U.S. 205 (1972), is the case in which the United States Supreme Court found that Amish children could not be placed under compulsory education past 8th grade. The parents' fundamental right to freedom of religion ...

'', (in European law

European Union law is a system of rules operating within the member states of the European Union (EU). Since the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community following World War II, the EU has developed the aim to "promote peace, its valu ...

) ''S.A.S. v. France

''S.A.S. v. France'' was a case brought for the European Court of Human Rights which ruled that the French ban on face covering did not violate European Convention on Human Rights's (ECHR) provisions on right to privacy or freedom of religion, nor ...

'', and numerous other jurisdictions.

History

Historically, ''freedom of religion'' has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while ''freedom of worship'' has been defined as freedom of individual action. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. An example commonly cited by scholars is the status of

Historically, ''freedom of religion'' has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while ''freedom of worship'' has been defined as freedom of individual action. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. An example commonly cited by scholars is the status of dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

s under Islamic sharia law. Stemming from the Pact of Umar

The Pact of Umar (also known as the Covenant of Umar, Treaty of Umar or Laws of Umar; ar, شروط عمر or or ), is a treaty between the Muslims and the non-Muslim inhabitants of either Syria, Mesopotamia, or Jerusalem that later gained a c ...

and literally meaning "protected individuals", it is often argued that non-Muslims possessing the dhimmi status in medieval Islamic societies enjoyed greater freedoms than non-Christians in most medieval European societies, while duly noting that the protection was limited because of regulation by and obligations to government such as taxation (compare jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent Kafir, non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The jizya tax has been unde ...

and zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ne ...

) and military service differed between religions. In modern concepts of religious freedom, the law is usually blind to religious affiliation in conferring such matters.

In Antiquity, a

In Antiquity, a syncretic

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

point of view often allowed communities of traders to operate under their own customs. When street mobs of separate quarters clashed in a Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

or Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

city, the issue was generally perceived to be an infringement of community rights.

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

established the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

ca. 550 BC, and initiated a general policy of permitting religious freedom throughout the empire, documenting this on the Cyrus Cylinder

The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay cylinder, now broken into several pieces, on which is written a declaration in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of Persia's Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great. Kuhrt (2007), p. 70, 72 It dates from the 6th c ...

.

Some of the historical exceptions have been in regions where one of the revealed religions has been in a position of power: Judaism, Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religions, Iranian religion and one of the world's History of religion, oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian peoples, Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a Dualism in cosmology, du ...

, Christianity and Islam. Others have been where the established order has felt threatened, as shown in the trial of Socrates

The trial of Socrates (399 BC) was held to determine the philosopher's guilt of two charges: ''asebeia'' (impiety) against the pantheon of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: ...

in 399 BC.

Freedom of religious worship was established in the Buddhist Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in the Indian subcontinent based in Magadha, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 1 ...

of ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

by Ashoka the Great

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

in the 3rd century BC, which was encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expres ...

.

GreekJewish clashes at Cyrene in 73 AD and 117 AD and in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

in 115 AD provide examples of cosmopolitan cities as scenes of tumult.

Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr />Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent)Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin

, ...

was one of the first rulers who in 13th century enacted a law explicitly guaranteeing religious freedom to everyone and every religion.

Ancient Roman policy

TheRomans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

tolerated most religions, including Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

, and encouraged local subjects to continue worshipping their own gods. They did not however, tolerate Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

until it was legalised by the Roman emperor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

in 311. Holmes and Bickers note that as long as Christianity was treated as a part of Judaism it enjoyed the same freedom, but the Christian claim to religious exclusivity meant its followers found themselves subject to hostility.

The early Christian apologist Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

was the first-known writer referring to the term ''libertas religionis''. The Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

guaranteed freedom of religion in the Roman Empire until the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholic (term), Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds s ...

in 380, which outlawed all religions except Christianity.

Muslim world

Following a period of fighting lasting around a hundred years before 620 AD which mainly involved Arab and Jewish inhabitants ofMedina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

(then known as ''Yathrib''), religious freedom for Muslims, Jews and pagans Pagans may refer to:

* Paganism, a group of pre-Christian religions practiced in the Roman Empire

* Modern Paganism, a group of contemporary religious practices

* Order of the Vine, a druidic faction in the ''Thief'' video game series

* Pagan's ...

was declared by Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

in the Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina (, ''Dustūr al-Madīna''), also known as the Charter of Medina ( ar, صحيفة المدينة, ''Ṣaḥīfat al-Madīnah''; or: , ''Mīthāq al-Madina'' "Covenant of Medina"), is the modern name given to a document be ...

. In early Muslim history (until mid 11th century), most Islamic scholars maintained a level of separation from the state which helped to establish some elements of institutional religious freedom. The Islamic Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

later guaranteed religious freedom under the conditions that non-Muslim communities accept ''dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

'' status and their adult males pay the punitive ''jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent Kafir, non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Sharia, Islamic law. The jizya tax has been unde ...

'' tax instead of the ''zakat

Zakat ( ar, زكاة; , "that which purifies", also Zakat al-mal , "zakat on wealth", or Zakah) is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam as a religious obligation, and by Quranic ranking, is ne ...

'' paid by Muslim citizens. Though Dhimmis were not given the same political rights as Muslims, they nevertheless did enjoy equality under the laws of property, contract, and obligation.

Religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and tolerating the religious diversity of a society or countr ...

existed in classical Islamic ethics

Islamic ethics (أخلاق إسلامية) is the "philosophical reflection upon moral conduct" with a view to defining "good character" and attaining the "pleasure of God" (''raza-e Ilahi''). It is distinguished from "Islamic morality", which per ...

and Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

, as the religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas others ...

s and courts of other religions, including Christianity, Judaism and Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, were usually accommodated within the Islamic legal framework, as seen in the early Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

, Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

, and the Ottoman Millet system. In medieval Islamic societies, the ''qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a '' sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and mino ...

'' (Islamic judges) usually could not interfere in the matters of non-Muslims unless the parties voluntarily choose to be judged according to Islamic law, thus the ''dhimmi'' communities living in Islamic state

An Islamic state is a State (polity), state that has a form of government based on sharia, Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical Polity, polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a t ...

s usually had their own laws independent from the Sharia law, such as the Jews who would have their own ''Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' courts.

Dhimmis were allowed to operate their own courts following their own legal systems in cases that did not involve other religious groups, or capital offences or threats to public order. Non-Muslims were allowed to engage in religious practices that were usually forbidden by Islamic law, such as the consumption of alcohol and pork, as well as religious practices which Muslims found repugnant, such as the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic on ...

practice of incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity (marriage or stepfamily), adoption ...

uous "self-marriage" where a man could marry his mother, sister or daughter. According to the famous Islamic legal scholar Ibn Qayyim

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb al-Zurʿī l-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he school ...

(1292–1350), non-Muslims had the right to engage in such religious practices even if it offended Muslims, under the conditions that such cases not be presented to Islamic Sharia courts and that these religious minorities believed that the practice in question is permissible according to their religion.

Despite Dhimmis enjoying special statuses under the Caliphates, they were not considered equals, and sporadic persecutions of non-Muslim groups did occur in the history of the Caliphates.

India

Ancient Jews fleeing frompersecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in their homeland 2,500 years ago settled in India and never faced anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Freedom of religion edicts

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Pro ...

have been found written during Ashoka the Great

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

's reign in the 3rd century BC. Freedom to practise, preach and propagate any religion is a constitutional right in Modern India. Most major religious festivals of the main communities are included in the list of national holidays.

Although India is an 80% Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

country, India is a secular state without any state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

s.

Many scholars and intellectuals believe that India's predominant religion, Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

, has long been a most tolerant religion. Rajni Kothari

Rajni Kothari (16 August 1928 – 19 January 2015) was an Indian political scientist, political theorist, academic and writer. He was the founder of Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in 1963, a social sciences and humanities res ...

, founder of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies

The Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) is an Indian research institute for the social sciences and humanities. It was founded in 1963 by Rajni Kothari and is largely funded by the Indian Council of Social Science Research Govt ...

has written, "ndia Ndia or NDIA may refer to:

* Ndia Constituency, Kirinyaga District, Central Province, Kenya

*Alternative name for the Southern Kirinyaga dialect of the Kikuyu language

*National Defense Industrial Association, an American trade association

* Natio ...

is a country built on the foundations of a civilisation that is fundamentally non-religious."

The Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current Dal ...

, the Tibetan leader in exile, said that religious tolerance of 'Aryabhoomi,' a reference to India found in the Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the ''Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kuruk ...

, has been in existence in this country from thousands of years. "Not only Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism which are the native religions but also Christianity and Islam have flourished here. Religious tolerance is inherent in Indian tradition," the Dalai Lama said.

Freedom of religion in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

is exemplified by the reign of King Piyadasi (304–232 BC) (Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

). One of King Ashoka's main concerns was to reform governmental institutes and exercise moral principles in his attempt to create a just and humane society. Later he promoted the principles of Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, and the creation of a just, understanding and fair society was held as an important principle for many ancient rulers of this time in the East.

The importance of freedom of worship in India was encapsulated in an inscription of Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

:

On the main Asian continent, the Mongols were tolerant of religions. People could worship as they wished freely and openly.

After the arrival of Europeans, Christians in their zeal to convert local as per belief in conversion as service of God, have also been seen to fall into frivolous methods since their arrival, though by and large there are hardly any reports of law and order disturbance from mobs with Christian beliefs, except perhaps in the north eastern region of India.

Freedom of religion in contemporary India is a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 25 of the nation's constitution. Accordingly, every citizen of India has a right to profess, practice and propagate their religions peacefully.

In September 2010, the Indian state of Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

's State Election Commissioner announced that "Religious heads cannot issue calls to vote for members of a particular community or to defeat the nonbelievers". The Catholic Church comprising Latin, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara rites used to give clear directions to the faithful on exercising their franchise during elections through pastoral letters issued by bishops or council of bishops. The pastoral letter issued by Kerala Catholic Bishops' Council (KCBC) on the eve of the poll urged the faithful to shun atheists.

Even today, most Indians celebrate all religious festivals with equal enthusiasm and respect. Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

festivals like Deepavali

Diwali (), Dewali, Divali, or Deepavali (IAST: ''dīpāvalī''), also known as the Festival of Lights, related to Jain Diwali, Bandi Chhor Divas, Tihar, Swanti, Sohrai, and Bandna, is a religious celebration in Indian religions. It is on ...

and Holi

Holi (), also known as the Festival of Colours, the Festival of Spring, and the Festival of Love,The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) p. 874 "Holi /'həʊli:/ noun a Hindu spring festival ...". is an ancient Hindu religious festival ...

, Muslim festivals like Eid al-Fitr

, nickname = Festival of Breaking the Fast, Lesser Eid, Sweet Eid, Sugar Feast

, observedby = Muslims

, type = Islamic

, longtype = Islamic

, significance = Commemoration to mark the end of fasting in Ramadan

, dat ...

, Eid-Ul-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's comm ...

, Muharram

Muḥarram ( ar, ٱلْمُحَرَّم) (fully known as Muharram ul Haram) is the first month of the Islamic calendar. It is one of the four sacred months of the year when warfare is forbidden. It is held to be the second holiest month after R ...

, Christian festivals like Christmas and other festivals like Buddha Purnima

Buddha's Birthday (also known as Buddha Jayanti, also known as his day of enlightenment – Buddha Purnima, Buddha Pournami) is a Buddhist festival that is celebrated in most of East Asia and South Asia commemorating the birth of the Prince ...

, Mahavir Jayanti

Mahavir Janma Kalyanak is one of the most important religious festivals in Jainism. It celebrates the birth of Mahavir, the twenty-fourth and last Tirthankara of present Avasarpiṇī. On the Gregorian calendar, the holiday occurs either in Ma ...

, Gur Purab etc. are celebrated and enjoyed by all Indians.

Europe

Religious intolerance

Most Roman Catholic kingdoms kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the

Most Roman Catholic kingdoms kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Jews were alternately tolerated and persecuted, the most notable examples of the latter being the expulsion of all Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

from Spain in 1492. Some of those who remained and converted were tried as heretics in the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

for allegedly practicing Judaism in secret. Despite the persecution of Jews, they were the most tolerated non-Catholic faith in Europe.

However, the latter was in part a reaction to the growing movement that became the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. As early as 1380, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of O ...

in England denied transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of th ...

and began his translation of the Bible into English. He was condemned in a papal bull in 1410, and all his books were burned.

In 1414, Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspir ...

, a Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n preacher of reformation, was given a safe conduct by the Holy Roman Emperor to attend the Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

. Not entirely trusting in his safety, he made his will before he left. His forebodings proved accurate, and he was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. The Council also decreed that Wycliffe's remains be disinterred and cast out. This decree was not carried out until 1429.

After the fall of the city of Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

, Spain, in 1492, the Muslim population was promised religious freedom by the Treaty of Granada

The Treaty of Granada, also known as the Capitulation of Granada or simply the Capitulations, was signed and ratified on November 25, 1491, between Boabdil, the sultan of Granada, and Ferdinand and Isabella, the King and Queen of Castile, Leó ...

, but that promise was short-lived. In 1501, Granada's Muslims were given an ultimatum to either convert to Christianity or to emigrate. The majority converted, but only superficially, continuing to dress and speak as they had before and to secretly practice Islam. The Morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open p ...

s (converts to Christianity) were ultimately expelled from Spain between 1609 (Castile) and 1614 (rest of Spain), by Philip III.

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

published his famous 95 Theses in Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon language, Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the Ri ...

on 31 October 1517. His major aim was theological, summed up in the three basic dogmas of Protestantism:

* The Bible only is infallible.

* Every Christian can interpret it.

* Human sins are so wrongful that no deed or merit, only God's grace, can lead to salvation.

In consequence, Luther hoped to stop the sale of indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The '' Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

s and to reform the Church from within. In 1521, he was given the chance to recant at the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

before Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (Crown of Castile, Castil ...

. After he refused to recant, he was declared heretic. Partly for his own protection, he was sequestered on the Wartburg

The Wartburg () is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the p ...

in the possessions of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony

Frederick III (17 January 1463 – 5 May 1525), also known as Frederick the Wise (German ''Friedrich der Weise''), was Elector of Saxony from 1486 to 1525, who is mostly remembered for the worldly protection of his subject Martin Luther.

Freder ...

, where he translated the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

into German. He was excommunicated by papal bull in 1521.

However, the movement continued to gain ground in his absence and spread to Switzerland. Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

preached reform in Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

from 1520 to 1523. He opposed the sale of indulgences, celibacy, pilgrimages, pictures, statues, relics, altars, and organs. This culminated in outright war between the Swiss cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, t ...

that accepted Protestantism and the Catholics. In 1531, the Catholics were victorious, and Zwingli was killed in battle. The Catholic cantons made peace with Zurich and Berne.

The defiance of papal authority proved contagious, and in 1533, when Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

was excommunicated for his divorce and remarriage to Anne Boleyn, he promptly established a state church with bishops appointed by the crown. This was not without internal opposition, and Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, who had been his Lord Chancellor, was executed in 1535 for opposition to Henry.

In 1535, the Swiss canton of Geneva became Protestant. In 1536, the Bern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

ese imposed the reformation on the canton of Vaud

Vaud ( ; french: (Canton de) Vaud, ; german: (Kanton) Waadt, or ), more formally the canton of Vaud, is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of ten districts and its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat of arms b ...

by conquest. They sacked the cathedral in Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR-74), ...

and destroyed all its art and statuary. John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

, who had been active in Geneva was expelled in 1538 in a power struggle, but he was invited back in 1540.

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

returned that country briefly to the Catholic fold in 1553 and persecuted Protestants. However, her half-sister, Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

was to restore the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

in 1558, this time permanently, and began to persecute Catholics again. The King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

commissioned by King James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the Union of the Crowns, union of the Scottish and Eng ...

and published in 1611 proved a landmark for Protestant worship, with official Catholic forms of worship being banned.

In France, although peace was made between Protestants and Catholics at the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye

The Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye was signed on 8 August 1570 by Charles IX of France, Gaspard II de Coligny and Jeanne d'Albret, and ended the 1568 to 1570 Third Civil War, part of the French Wars of Religion.

The Peace went much further tha ...

in 1570, persecution continued, most notably in the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew's Day on 24 August 1572, in which thousands of Protestants throughout France were killed. A few years before, at the "Michelade" of Nîmes in 1567, Protestants had massacred the local Catholic clergy.

Early steps and attempts in the way of tolerance

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards, and native Sicilians lived in harmony. Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1215–1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his Christian army and even into his personal bodyguards.

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards, and native Sicilians lived in harmony. Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1215–1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his Christian army and even into his personal bodyguards.

Kingdom of Bohemia

The Kingdom of Bohemia ( cs, České království),; la, link=no, Regnum Bohemiae sometimes in English literature referred to as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe, the predecessor of the modern Czec ...

(present-day Czech Republic) enjoyed religious freedom between 1436 and 1620 as a result of the Bohemian Reformation

The Bohemian Reformation (also known as the Czech Reformation or Hussite Reformation), preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, was a Christian movement in the late medieval and early modern Kingdom and Crown of Bohemia (mostly what is no ...

, and became one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world during that period of time. The so-called Basel Compacts of 1436 declared the freedom of religion and peace between Catholics and Utraquists

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds") or Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', mug, borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', shell, husk; Czech: kališníci) was a belief amongst Hussites, a reformist Christia ...

. In 1609 Emperor Rudolf II granted Bohemia greater religious liberty with his Letter of Majesty. The privileged position of the Catholic Church in the Czech kingdom was firmly established after the Battle of White Mountain

), near Prague, Bohemian Confederation(present-day Czech Republic)

, coordinates =

, territory =

, result = Imperial-Spanish victory

, status =

, combatants_header =

, combatant1 = Catholic L ...

in 1620. Gradually freedom of religion in Bohemian lands came to an end and Protestants fled or were expelled from the country. A devout Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II forcibly converted Austrian and Bohemian Protestants.

In the meantime, in Germany Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

drafted the Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, ''Confessio Augustana'', is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Re ...

as a common confession for the Lutherans and the free territories. It was presented to Charles V in 1530.

In the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, Charles V agreed to tolerate Lutheranism in 1555 at the Peace of Augsburg. Each state was to take the religion of its prince, but within those states, there was not necessarily religious tolerance. Citizens of other faiths could relocate to a more hospitable environment.

In France, from the 1550s, many attempts to reconcile Catholics and Protestants and to establish tolerance failed because the State was too weak to enforce them. It took the victory of prince Henry IV of France, who had converted into Protestantism, and his accession to the throne, to impose religious tolerance formalized in the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was signed in April 1598 by King Henry IV and granted the Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was in essence completely Catholic. In the edict, Henry aimed pr ...

in 1598. It would remain in force for over 80 years until its revocation in 1685 by Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Versa ...

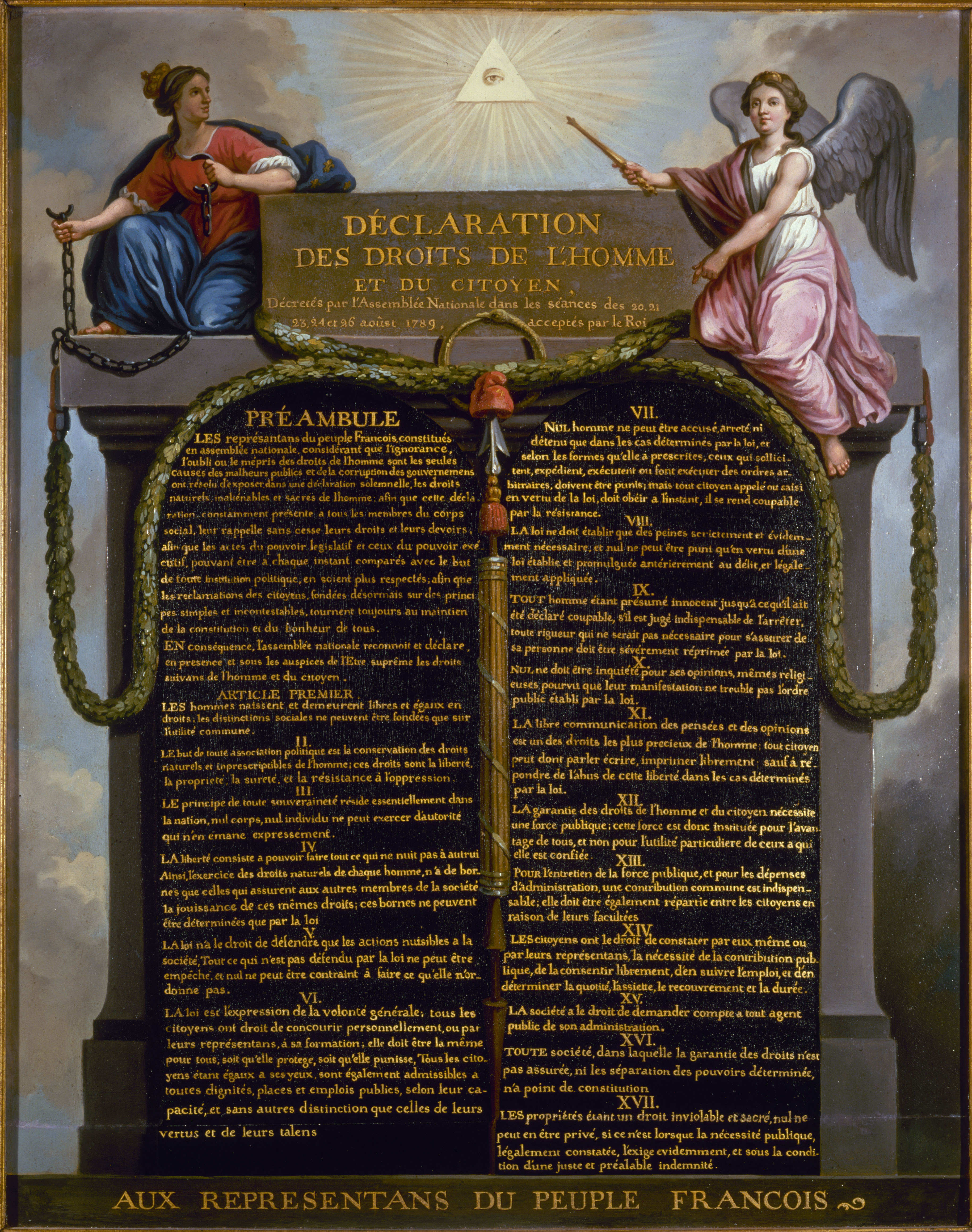

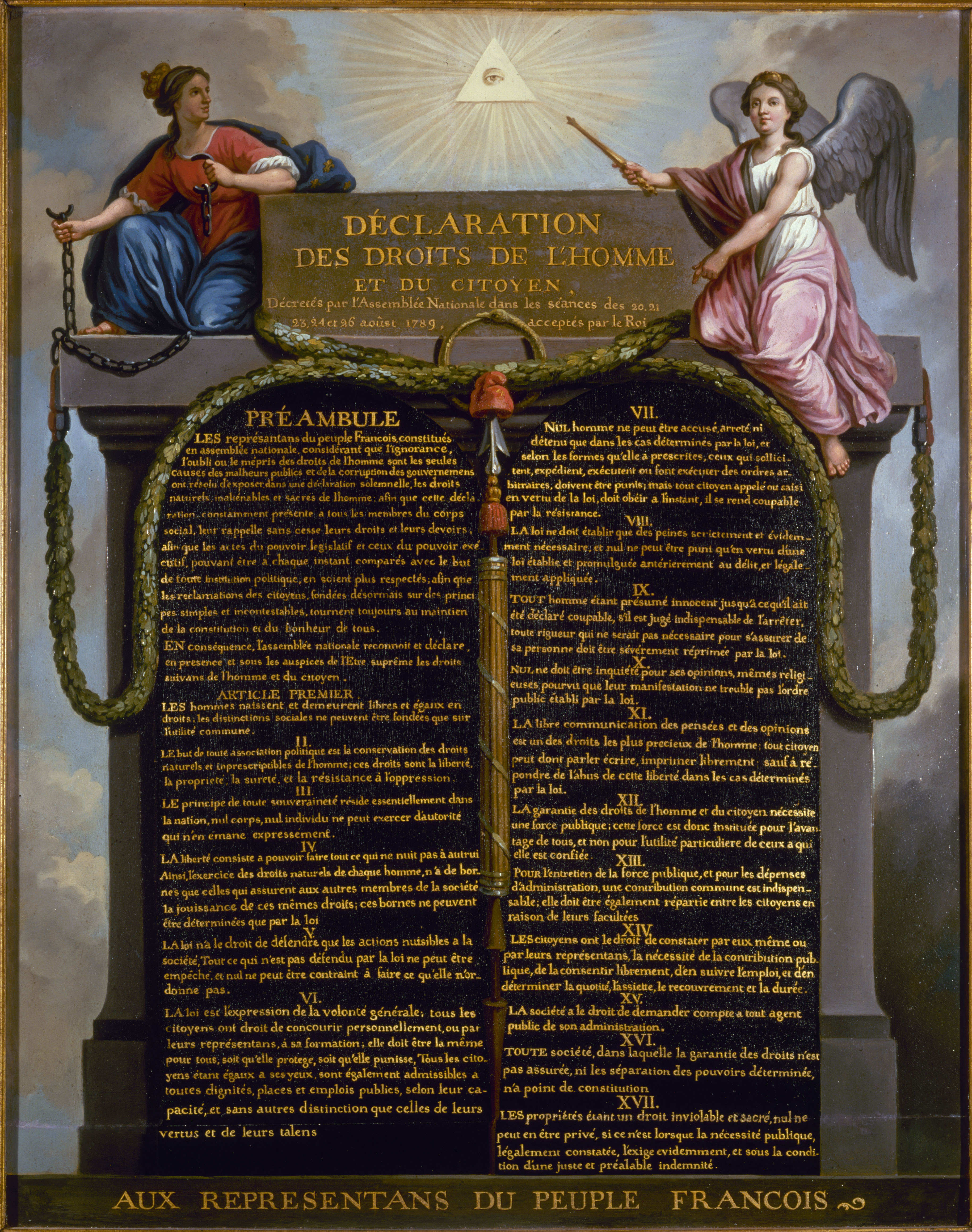

. Intolerance remained the norm until Louis XVI, who signed the Edict of Versailles (1787), then the constitutional text of 24 December 1789, granting civilian rights to Protestants. The French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

then abolished state religion and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (french: Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen de 1789, links=no), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolu ...

(1789) guarantees freedom of religion, as long as religious activities do not infringe on public order in ways detrimental to society.

Early laws and legal guarantees for religious freedom

Principality of Transylvania

In 1558, theTransylvanian Diet

The Transylvanian Diet (german: Siebenbürgischer Landtag; hu, erdélyi országgyűlés; ro, Dieta Transilvaniei) was an important legislative, administrative and judicial body of the Principality (from 1765 Grand Principality) of Transylvania ...

's Edict of Torda

The Edict of Torda ( hu, tordai ediktum, ro, Edictul de la Turda, german: Edikt von Torda) was a decree that authorized local communities to freely elect their preachers in the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom of John Sigismund Zápolya. The delegates ...

declared free practice of both Catholicism and Lutheranism. Calvinism, however, was prohibited. Calvinism was included among the accepted religions in 1564. Ten years after the first law, in 1568, the same Diet, under the chairmanship of King of Hungary

The King of Hungary ( hu, magyar király) was the ruling head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1000 (or 1001) to 1918. The style of title "Apostolic King of Hungary" (''Apostoli Magyar Király'') was endorsed by Pope Clement XIII in 1758 ...

, and Prince of Transylvania

The Prince of Transylvania ( hu, erdélyi fejedelem, german: Fürst von Siebenbürgen, la, princeps Transsylvaniae, ro, principele TransilvanieiFallenbüchl 1988, p. 77.) was the head of state of the Principality of Transylvania from the last d ...

John Sigismund Zápolya

John Sigismund Zápolya or Szapolyai ( hu, Szapolyai János Zsigmond; 7 July 1540 – 14 March 1571) was King of Hungary as John II from 1540 to 1551 and from 1556 to 1570, and the first Prince of Transylvania, from 1570 to his death. He was ...

(John II), following the teaching of Ferenc Dávid

Ferenc Dávid (also rendered as ''Francis David'' or ''Francis Davidis''; born as Franz David Hertel, c. 1520 – 15 November 1579) was a Unitarian preacher from Transylvania, the founder of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania, and the lea ...

, the founder of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania

The Unitarian Church of Transylvania ( hu, Erdélyi Unitárius Egyház; ro, Biserica Unitariană din Transilvania), also known as the Hungarian Unitarian Church ( hu, Magyar Unitárius Egyház; ro, Biserica Unitariană Maghiară), is a Christian ...

, extended the freedom to all religions, declaring that "''It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion''". However, it was more than a religious tolerance; it declared the equality of the religions, prohibiting all kinds of acts from authorities or from simple people, which could harm other groups or people because of their religious beliefs. The emergence in social hierarchy wasn't dependent on the religion of the person thus Transylvania had also Catholic and Protestant monarchs, who all respected the Edict of Torda. The lack of state religion was unique for centuries in Europe. Therefore, the Edict of Torda is considered as the first legal guarantee of religious freedom in Christian Europe.

Four religions (Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

, Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there i ...

) were named as accepted religions (religo recepta), having their representatives in the Transylvanian Diet, while the other religions, like the Orthodoxs, Sabbatarians

Sabbatarianism advocates the observation of the Sabbath in Christianity, in keeping with the Ten Commandments.

The observance of Sunday as a day of worship and rest is a form of first-day Sabbatarianism, a view which was historically heralded ...

and Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

were tolerated churches (religio tolerata), which meant that they had no power in the law making and no veto rights in the Diet, but they were not persecuted in any way. Thanks to the Edict of Torda, from the last decades of the 16th century Transylvania was the only place in Europe, where so many religions could live together in harmony and without persecution.

This religious freedom ended however for some of the religions of Transylvania in 1638. After this year the Sabbatarians

Sabbatarianism advocates the observation of the Sabbath in Christianity, in keeping with the Ten Commandments.

The observance of Sunday as a day of worship and rest is a form of first-day Sabbatarianism, a view which was historically heralded ...

begun to be persecuted, and forced to convert to one of the accepted Christian religions of Transylvania.

=Habsburg rule in Transylvania

= Also the Unitarians (despite of being one of the "accepted religions") started to be put under an ever-growing pressure, which culminated after the Habsburg conquest of Transylvania (1691), Also after the Habsburg occupation, the new Austrian masters forced in the middle of the 18th century theHutterite

Hutterites (german: link=no, Hutterer), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptism, Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Refor ...

Anabaptists (who found a safe haven in 1621 in Transylvania, after the persecution to which they were subjected in the Austrian provinces and Moravia) to convert to Catholicism or to migrate in another country, which finally the Anabaptists did, leaving Transylvania and Hungary for Wallachia, than from there to Russia, and finally in the United States.

Netherlands

In theUnion of Utrecht

The Union of Utrecht ( nl, Unie van Utrecht) was a treaty signed on 23 January 1579 in Utrecht, Netherlands, unifying the northern provinces of the Netherlands, until then under the control of Habsburg Spain.

History

The Union of Utrecht is r ...

(20 January 1579), personal freedom of religion was declared in the struggle between the Northern Netherlands and Spain. The Union of Utrecht was an important step in the establishment of the Dutch Republic (from 1581 to 1795). Under Calvinist leadership, the Netherlands became the most tolerant country in Europe. It granted asylum to persecuted religious minorities, such as the Huguenots, the Dissenters, and the Jews who had been expelled from Spain and Portugal. The establishment of a Jewish community in the Netherlands and New Amsterdam (present-day New York) during the Dutch Republic is an example of religious freedom. When New Amsterdam surrendered to the English in 1664, freedom of religion was guaranteed in the Articles of Capitulation. It benefitted also the Jews who had landed on Manhattan Island in 1654, fleeing Portuguese persecution in Brazil. During the 18th century, other Jewish communities were established at Newport, Rhode Island, Philadelphia, Charleston, Savannah, and Richmond.

Intolerance of dissident forms of Protestantism also continued, as evidenced by the exodus of the Pilgrims, who sought refuge, first in the Netherlands, and ultimately in America, founding Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

in Massachusetts in 1620. William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

, the founder of Philadelphia, was involved in a case which had a profound effect upon future American laws and those of England. In a classic case of jury nullification

Jury nullification (US/UK), jury equity (UK), or a perverse verdict (UK) occurs when the jury in a criminal trial gives a not guilty verdict despite a defendant having clearly broken the law. The jury's reasons may include the belief that the ...

, the jury refused to convict William Penn of preaching a Quaker sermon, which was illegal. Even though the jury was imprisoned for their acquittal, they stood by their decision and helped establish the freedom of religion.

Poland

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz, and the Kalisz Privilege, granted Jews in the Middle Ages special protection and positive discrimination in Poland when they were being persecuted in Western Europe. These r ...

was issued by the Duke of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

Boleslaus the Pious on 8 September 1264 in Kalisz

(The oldest city of Poland)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = ''Top:'' Town Hall, Former "Calisia" Piano Factory''Middle:'' Courthouse, "Gołębnik" tenement''Bottom:'' Aerial view of the Kalisz Old Town

, image_flag = POL Kalisz flag.svg ...

. The statute served as the basis for the legal position of Jews in Poland and led to the creation of the Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

-speaking autonomous Jewish nation until 1795. The statute granted exclusive jurisdiction of Jewish courts over Jewish matters and established a separate tribunal for matters involving Christians and Jews. Additionally, it guaranteed personal liberties and safety for Jews including freedom of religion, travel, and trade. The statute was ratified by subsequent Polish Kings: Casimir III of Poland

Casimir III the Great ( pl, Kazimierz III Wielki; 30 April 1310 – 5 November 1370) reigned as the King of Poland from 1333 to 1370. He also later became King of Ruthenia in 1340, and fought to retain the title in the Galicia-Volhynia Wars. He wa ...

in 1334, Casimir IV of Poland

Casimir is classically an English, French and Latin form of the Polish name Kazimierz. Feminine forms are Casimira and Kazimiera. It means "proclaimer (from ''kazać'' to preach) of peace (''mir'')."

List of variations

*Belarusian: Казі ...

in 1453 and Sigismund I of Poland

Sigismund I the Old ( pl, Zygmunt I Stary, lt, Žygimantas II Senasis; 1 January 1467 – 1 April 1548) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1506 until his death in 1548. Sigismund I was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty, the ...

in 1539. Poland freed Jews from direct royal authority, opening up enormous administrative and economic opportunities to them.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the futurePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

throughout the 15th and early 16th century, however, complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in 1573 during the Warsaw Confederation. Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth kept religious freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.

United States

Most of the early colonies were generally not tolerant of dissident forms of worship, with Maryland being one of the exceptions. For example,Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

found it necessary to found a new colony in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

to escape persecution in the theocratically dominated colony of Massachusetts. The Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

were the most active of the New England persecutors of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, and the persecuting spirit was shared by Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

and the colonies along the Connecticut river

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

. In 1660, one of the most notable victims of the religious intolerance was English Quaker Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan turned Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. ...

, who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony.Rogers, Horatio, 2009. Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston Common, 1 June 1660

' pp. 1–2. BiblioBazaar, LLC. As one of the four executed Quakers known as the

Boston martyrs

The Boston martyrs is the name given in Quaker tradition to the three English members of the Society of Friends, Marmaduke Stephenson, William Robinson and Mary Dyer, and to the Barbadian Friend William Leddra, who were condemned to death and e ...

, the hanging of Dyer on the Boston gallows marked the beginning of the end of the Puritan theocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

and New England independence from English rule, and in 1661 King Charles II explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism. Anti-Catholic sentiment appeared in New England with the first Pilgrim and Puritan settlers. In 1647, Massachusetts passed a law prohibiting any Jesuit Roman Catholic priests from entering territory under Puritan jurisdiction. Any suspected person who could not clear himself was to be banished from the colony; a second offense carried a death penalty. The Pilgrims of New England held radical Protestant disapproval of Christmas. Christmas observance was outlawed in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in 1659. The ban by the Puritans was revoked in 1681 by an English appointed governor, however it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became common in the Boston region.

Freedom of religion was first applied as a principle of government in the founding of the colony of Maryland, founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore, in 1634.Zimmerman, MarkSymbol of Enduring Freedom

p. 19, Columbia Magazine, March 2010. Fifteen years later (1649), the

Maryland Toleration Act

The Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, the first law in North America requiring religious tolerance for Christians. It was passed on April 21, 1649, by the assembly of the Maryland colony, in St. Mary's City in S ...

, drafted by Lord Baltimore, provided: "No person or persons...shall from henceforth be any waies troubled, molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof." The Act allowed freedom of worship for all Trinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

Christians in Maryland, but sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

anyone who denied the divinity of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. The Maryland Toleration Act was repealed during the Cromwellian Era with the assistance of Protestant assemblymen and a new law barring Catholics from openly practicing their religion was passed. In 1657, the Catholic Lord Baltimore regained control after making a deal with the colony's Protestants, and in 1658 the Act was again passed by the colonial assembly. This time, it would last more than thirty years, until 1692 when, after Maryland's Protestant Revolution of 1689, freedom of religion was again rescinded. Retrieved 22 February 2010 In addition, in 1704, an Act was passed "to prevent the growth of Popery in this Province", preventing Catholics from holding political office. Full religious toleration

Toleration is the allowing, permitting, or acceptance of an action, idea, object, or person which one dislikes or disagrees with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining "toleration" as a ...