First Nations (french: Premières Nations) is a term used to identify those

Indigenous Canadian peoples who are neither

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

nor

Métis. Traditionally, First Nations in Canada were peoples who lived south of the

tree line

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snow ...

, and mainly south of the

Arctic Circle. There are 634 recognized

First Nations governments or bands across Canada. Roughly half are located in the provinces of

Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

and

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

.

Under

Charter jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, First Nations are a "designated group," along with women,

visible minorities

A visible minority () is defined by the Government of Canada as "persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour". The term is used primarily as a demographic category by Statistics Canada, in connect ...

, and people with physical or mental disabilities. First Nations are not defined as a

visible minority

A visible minority () is defined by the Government of Canada as "persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour". The term is used primarily as a demographic category by Statistics Canada, in connect ...

by the criteria of

Statistics Canada.

North American indigenous peoples have cultures spanning thousands of years. Some of their

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

s accurately describe historical events, such as the

Cascadia earthquake of 1700 and the 18th-century

Tseax Cone

The Tseax Cone ( ), also called the Tseax River Cone or the Aiyansh Volcano, is a young and active cinder cone and adjacent lava flows associated with the Nass Ranges and the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province. It is located east of Crater ...

eruption. Written records began with the arrival of

European explorers and

colonists during the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

in the late 15th century.

by

trappers

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or gin, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithic ...

,

traders,

explorers

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

, and

missionaries give important evidence of early contact culture. In addition,

archeological and

anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

research, as well as

linguistics

Linguistics is the science, scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure ...

, have helped scholars piece together an understanding of ancient cultures and historic peoples.

Terminology

Collectively, First Nations,

Inuit,

and Métis (

FNIM

In Canada, Indigenous groups comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Although ''Indian'' is a term still commonly used in legal documents, the descriptors ''Indian'' and '' Eskimo'' have fallen into disuse in Canada, and most consider the ...

) peoples constitute

Indigenous peoples in Canada,

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

, or "

first peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

". "First Nation" as a term became officially used by the government beginning in 1980s to replace the term "Indian band" in referring to groups of Indians with common government and language.

The First Nations people had begun to identify by this term during 1970s activism, in order to avoid using the word "Indian", which some considered offensive.

No legal definition of the term exists.

Some indigenous peoples in Canada have also adopted the term First Nation to replace the word "band" in the formal name of their community. A band is a "body of Indians (a) for whose use and benefit in common lands ... have been set apart, (b) ... moneys are held ... or (c) declared ... to be a band for the purposes of", according to the ''

Indian Act'' by the

Canadian Crown

The monarchy of Canada is Canada's form of government embodied by the Canadian sovereign and head of state. It is at the core of Canada's constitutional federal structure and Westminster-style parliamentary democracy. The monarchy is the founda ...

.

The term 'Indian' is a misnomer, given to indigenous peoples of North America by European explorers who erroneously thought they had landed in the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

. The use of the term

''Native Americans'', which the government and others have adopted in the United States, is not common in Canada. It refers more specifically to the Indigenous peoples residing within the boundaries of the US. The parallel term "Native Canadian" is not commonly used, but "Native" (in English) and "" (in

Canadian French; from the Greek , own, and , land) are. Under the

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, also known as the "Indian ''

Magna Carta,''"

the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

referred to

indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

in

British territory

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remnants of the former Bri ...

as tribes or nations. The term First Nations is capitalized. Bands and

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective Identity (social science), identity of a group of people unde ...

s may have slightly different meanings.

Within Canada, the term First Nations has come into general use for indigenous peoples other than

Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories ...

and

Métis. Individuals using the term outside Canada include

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

,

U.S. tribes within the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

, as well as supporters of the

Cascadian independence movement. The singular, commonly used on culturally politicized

reserves, is the term "First Nations person" (when gender-specific, "First Nations man" or "First Nations woman"). Since the late 20th century, members of various nations more frequently identify by their

tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

or

national

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, c ...

identity only, e.g., "I'm

Haida", or "We're

Kwantlens", in recognition of the distinct First Nations.

History

Nationhood

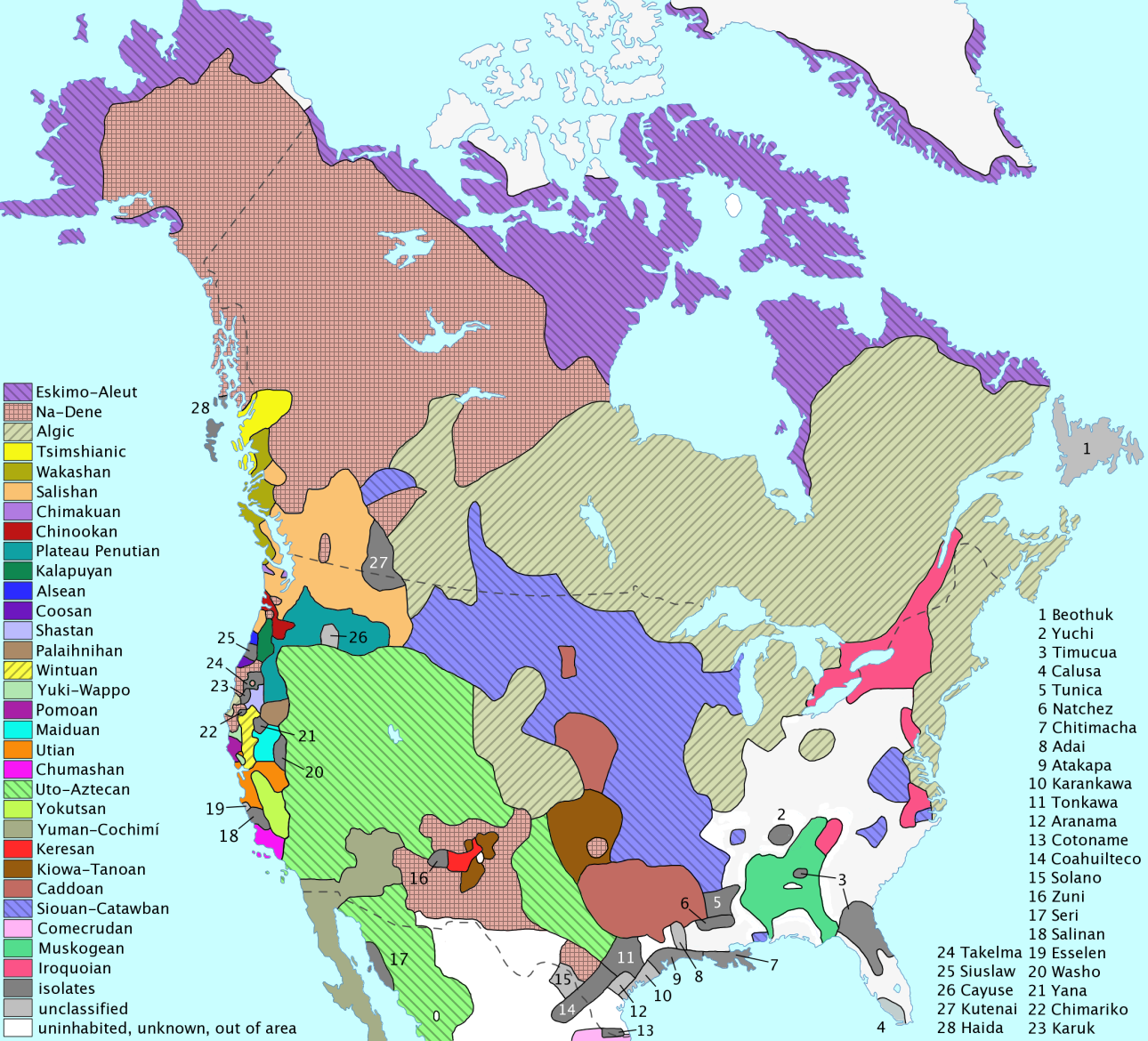

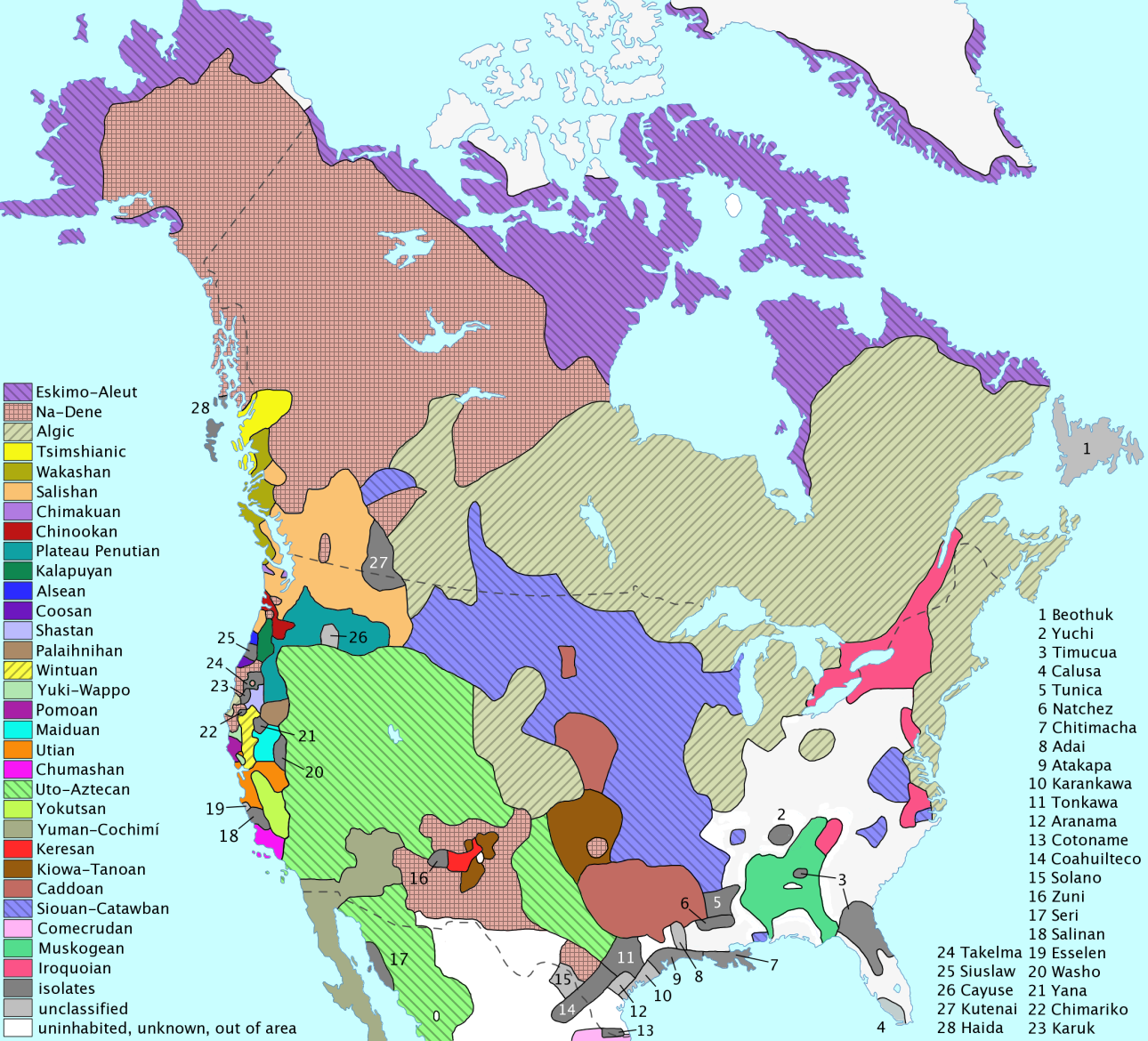

:''First Nations by linguistic-cultural area:

List of First Nations peoples

The following is a partial list of First Nations peoples of Canada, organized by linguistic-cultural area. It only includes First Nations people, which by definition excludes Metis and Canadian Inuit groups. The areas used here are in accordance t ...

''

First Nations peoples had settled and established trade routes across what is now Canada by 500 BCE – 1,000 CE. Communities developed, each with its own culture, customs, and character.

In the northwest were the

Athapaskan-speaking peoples,

Slavey

The Slavey (also Slave and South Slavey) are a First Nations indigenous peoples of the Dene group, indigenous to the Great Slave Lake region, in Canada's Northwest Territories, and extending into northeastern British Columbia and northwestern ...

,

Tłı̨chǫ

The Tłı̨chǫ (, ) people, sometimes spelled Tlicho and also known as the Dogrib, are a Dene First Nations people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group living in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

Name

The name ''Dogrib'' ...

,

Tutchone-speaking peoples, and

Tlingit

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ), . Along the Pacific coast were the Haida,

Tsimshian

The Tsimshian (; tsi, Ts’msyan or Tsm'syen) are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their communities are mostly in coastal British Columbia in Terrace and Prince Rupert, and Metlakatla, Alaska on Annette Island, the only r ...

, Salish,

Kwakiutl,

Nuu-chah-nulth

The Nuu-chah-nulth (; Nuučaan̓uł: ), also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth or Tahkaht, are one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada. The term Nuu-chah-nulth is used to describe fifte ...

,

Nisga'a

The Nisga’a , often formerly spelled Nishga and spelled in the Nisga'a language as (pronounced ), are an Indigenous people of Canada in British Columbia. They reside in the Nass River valley of northwestern British Columbia. The name is a ...

and

Gitxsan

Gitxsan (also spelled Gitksan) are an Indigenous people in Canada whose home territory comprises most of the area known as the Skeena Country in English (: means "people of" and : means "the River of Mist"). Gitksan territory encompasses approxi ...

. In the plains were the Blackfoot,

Kainai

The Kainai Nation (or , or Blood Tribe) ( bla, Káínaa) is a First Nations band government in southern Alberta, Canada, with a population of 12,800 members in 2015, up from 11,791 in December 2013.

translates directly to 'many chief' (fro ...

,

Sarcee and

Northern Peigan

The Piikani Nation (, formerly the Peigan Nation) ( bla, Piikáni) is a First Nation (or an Indian band as defined by the '' Indian Act''), representing the Indigenous people in Canada known as the Northern Piikani ( bla, script=Latn, Aapátohsi ...

. In the northern woodlands were the

Cree and

Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene Indigenous Canadian people of the Athabaskan language family, whose ancestors are identified ...

. Around the Great Lakes were the

Anishinaabe

The Anishinaabeg (adjectival: Anishinaabe) are a group of culturally related Indigenous peoples present in the Great Lakes region of Canada and the United States. They include the Ojibwe (including Saulteaux and Oji-Cree), Odawa, Potawat ...

,

Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

,

Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and

Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, also known as the Huron

* Wyandot language

Wyandot (sometimes spelled Wandat) is the Iroquoian language traditionally spoken by the people known variously as Wyandot or Wya ...

. Along the Atlantic coast were the

Beothuk

The Beothuk ( or ; also spelled Beothuck) were a group of indigenous people who lived on the island of Newfoundland.

Beginning around AD 1500, the Beothuk culture formed. This appeared to be the most recent cultural manifestation of peoples w ...

,

Maliseet,

Innu,

Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

and

Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the nort ...

.

The

Blackfoot Confederacy

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

resides in the

Great Plains of

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

and

Canadian provinces of

Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

,

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a province in western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dak ...

.

The name ''Blackfoot'' came from the dye or paint on the bottoms the their leather

moccasin

A moccasin is a shoe, made of deerskin or other soft leather, consisting of a sole (made with leather that has not been "worked") and sides made of one piece of leather, stitched together at the top, and sometimes with a vamp (additional panel o ...

s. One account claimed that the Blackfoot Confederacies walked through the ashes of prairie fires, which in turn blackened the bottoms of their moccasins.

They had migrated onto the Great Plains (where they followed bison herds and cultivated berries and edible roots) from the area of now eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. Historically, they allowed only legitimate traders into their territory, making treaties only when the bison herds were exterminated in the 1870s.

Pre-contact

Squamish history

Squamish history is the series of past events, both passed on through oral tradition and recent history, of the Squamish (''Sḵwx̱wú7mesh''), a people indigenous to the southwestern part of British Columbia, Canada. Prior to colonization, they ...

is passed on through

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

of the

Squamish indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Prior to colonization and the introduction of writing had only oral tradition as a way to transmit stories, law, and knowledge across generations.

[

] The writing system established in the 1970s uses the

Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet or Roman alphabet is the collection of letters originally used by the ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered with the exception of extensions (such as diacritics), it used to write English and th ...

as a base. Knowledgeable elders have the responsibility to pass historical knowledge to the next generation. People lived and prospered for thousands of years until the

Great Flood

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval ...

. In another story, after the Flood, they repopulated from the villages of

Schenks and Chekwelp

Schenks ( Squamish ''Schètx̱w'') and Chekwelp (''Ch’ḵw’elhp'') are two villages of the Indigenous Squamish, located near what is now known as Gibsons, British Columbia. Although vacant for years, these villages are told in the oral his ...

, located at

Gibsons

Gibsons is a coastal community of 4,605 in southwestern British Columbia, Canada on the Strait of Georgia.

Although it is on the mainland, the Sunshine Coast is not accessible by road. Vehicle access is by BC Ferries from Horseshoe Bay in West ...

. When the water lines receded, the first Squamish came to be. The first man, named Tseḵánchten, built his

longhouse

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from timber and often rep ...

in the village, and later on another man named Xelálten, appeared on his longhouse roof and sent by the Creator, or in the

Squamish language

Squamish (; ', ''sníchim'' meaning "language") is a Coast Salish language spoken by the Squamish people of the Pacific Northwest. It is spoken in the area that is now called southwestern British Columbia, Canada, centred on their reserve comm ...

. He called this man his brother. It was from these two men that the population began to rise and the Squamish spread back through their territory.

The Iroquois influence extended from northern New York into what are now southern Ontario and the Montreal area of modern Quebec. The Iroquois Confederacy is, from oral tradition, formed circa 1142. Adept at cultivating the

Three Sisters (

maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

/

beans/

squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

), the Iroquois became powerful because of their confederacy. Gradually the Algonquians adopted agricultural practises enabling larger populations to be sustained.

The

Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakod ...

were close allies and trading partners of the Cree, engaging in wars against the

Gros Ventres

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

alongside them, and later fighting the Blackfoot.

A Plains people, they went no further north than the

North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows event ...

and purchased a great deal of European trade goods through Cree middlemen from the

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

. The lifestyle of this group was semi-nomadic, and they followed the herds of

bison during the warmer months. They traded with European traders, and worked with the

Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still re ...

,

Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent ...

, and

Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011) tribes.

[

]

In the earliest

oral history, the Algonquins were from the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

coast. Together with other Anicinàpek, they arrived at the "First Stopping Place" near Montreal.

[

] While the other Anicinàpe peoples continued their journey up the

St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, the Algonquins settled along the

Ottawa River (), an important highway for commerce, cultural exchange, and transportation. A distinct Algonquin identity, though, was not realized until after the dividing of the Anicinàpek at the "Third Stopping Place", estimated at 2,000 years ago near present-day

Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at t ...

.

According to their tradition, and from recordings in

birch bark

Birch bark or birchbark is the bark of several Eurasian and North American birch trees of the genus ''Betula''.

The strong and water-resistant cardboard-like bark can be easily cut, bent, and sewn, which has made it a valuable building, craftin ...

scrolls (), Ojibwe (an Algonquian-speaking people) came from the eastern areas of North America, or

Turtle Island, and from along the east coast.

[

] They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast. According to the oral history, seven great (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the to teach the peoples of the

way of life. One of the seven great beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the when the people were in its presence. The six great beings remained to teach while the one returned into the ocean. The six great beings then established (clans) for the peoples in the east. Of these , the five original Anishinaabe were the (

Bullhead), (Echo-maker, i.e.,

Crane), (

Pintail Duck), (Tender, i.e.,

Bear) and (Little

Moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

), then these six beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh being stayed, it would have established the

Thunderbird

Thunderbird, thunder bird or thunderbirds may refer to:

* Thunderbird (mythology), a legendary creature in certain North American indigenous peoples' history and culture

* Ford Thunderbird, a car

Birds

* Dromornithidae, extinct flightless birds ...

.

The Nuu-chah-nulth are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. The term ''Nuu-chah-nulth'' is used to describe fifteen separate but related First Nations, such as the

Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations,

Ehattesaht First Nation and

Hesquiaht First Nation

The Hesquiaht First Nation (pronounced Hesh-kwit or Hes-kwee-at) is a Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations band government based on the west coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. The Hesquiaht First Nation are members of the Nuu-chah-n ...

whose traditional home is on the west coast of

Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

. In pre-contact and early post-contact times, the number of nations was much greater, but

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and other consequences of contact resulted in the disappearance of groups, and the absorption of others into neighbouring groups. The Nuu-chah-nulth are relations of the

Kwakwaka'wakw, the

Haisla Haisla may refer to:

* Haisla people, an indigenous people living in Kitamaat, British Columbia, Canada.

* Haisla language, their northern Wakashan language.

* Haisla Nation The Haisla Nation is the Indian Act-mandated band government which nominall ...

, and the

Ditidaht

The Ditidaht First Nation is a First Nations band government on southern Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada.

The government has 17 reserve lands: Ahuk, Tsuquanah, Wyah, Clo-oose, Cheewat, Sarque, Carmanah, Iktuksasuk, Hobitan, Oyees, Doo ...

. The

Nuu-chah-nulth language

Nuu-chah-nulth (), Nootka (), is a Wakashan language in the Pacific Northwest of North America on the west coast of Vancouver Island, from Barkley Sound to Quatsino Sound in British Columbia by the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. Nuu-chah-nulth is a ...

is part of the

Wakashan language group.

In 1999 the discovery of the body of

Kwäday Dän Ts'ìnchi

Kwäday Dän Tsʼìnchi (), or Canadian Ice Man, is a naturally mummified body found in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in British Columbia, Canada, by a group of hunters in 1999. Kwäday Dän Tsʼìnchi means "Long Ago Person Found" in Southern ...

provided archaeologists with significant information on indigenous tribal life prior to extensive European contact. Kwäday Dän Ts'ìnchi (meaning "Long Ago Person Found" in

Southern Tutchone

The Southern Tutchone are a First Nations people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group living mainly in the southern Yukon in Canada. The Southern Tutchone language, traditionally spoken by the Southern Tutchone people, is a variet ...

), or "Canadian Ice Man", is a naturally

mummified

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay furt ...

body that a group of hunters found in

Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park

Tatshenshini-Alsek Park or Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Wilderness Park is a provincial park in British Columbia, Canada . It was established in 1993 after an intensive campaign by Canadian and American conservation organizations to halt mining e ...

in British Columbia.

Radiocarbon dating of artifacts found with the body placed the age of the find between 1450 AD and 1700 AD.

showed that he was a member of the

Champagne and Aishihik First Nations

The Champagne and Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) is a First Nation band government in Yukon, Canada. Historically its original population centres were Champagne (home of the ''Kwächä̀l kwächʼǟn'' - "Champagne people/band") and Aishihik (home ...

.

European contact

Aboriginal people in Canada interacted with Europeans as far back as 1000 AD,

but prolonged contact came only after Europeans established permanent settlements in the 17th and 18th centuries. European written accounts noted friendliness on the part of the First Nations,

who profited in trade with Europeans. Such trade strengthened the more organized political entities such as the Iroquois Confederation.

The

Aboriginal population is estimated to have been between 200,000 and two million in the late 15th century. The effect of European colonization was a 40 to 80 percent Aboriginal population decrease post-contact. This is attributed to various factors, including repeated outbreaks of European

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

s such as

influenza,

measles and

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

(to which they had not developed immunity), inter-nation conflicts over the fur trade, conflicts with colonial authorities and settlers and loss of land and a subsequent loss of nation self-suffiency.

For example, during the late 1630s, smallpox killed more than half of the

Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

, who controlled most of the early

fur trade in what became Canada. Reduced to fewer than 10,000 people, the Huron Wendat were attacked by the Iroquois, their traditional enemies. In the Maritimes, the Beothuk disappeared entirely.

There are reports of contact made before

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

between the first peoples and those from other continents.

Even in Columbus' time there was much speculation that other Europeans had made the trip in ancient or contemporary times;

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (August 14781557), commonly known as Oviedo, was a Spanish soldier, historian, writer, botanist and colonist. Oviedo participated in the Spanish colonization of the West Indies, arriving in the first few year ...

records accounts of these in his ''General y natural historia de las Indias'' of 1526, which includes biographical information on Columbus.

[

] Aboriginal first contact period is not well defined. The earliest accounts of contact occurred in the late 10th century, between the Beothuk and

Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the pr ...

.

[ According to the ]Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders ( is, Íslendingasögur, ), also known as family sagas, are one genre of Icelandic sagas. They are prose narratives mostly based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and early el ...

, the first European to see what is now Canada was Bjarni Herjólfsson

Bjarni Herjólfsson ( 10th century) was a Norse- Icelandic explorer who is believed to be the first known European discoverer of the mainland of the Americas, which he sighted in 986.

Life

Bjarni was born to Herjólfr, son of Bárdi Herjólfsso ...

, who was blown off course en route from Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

to Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

in the summer of 985 or 986 CE.

16th–18th centuries

The Portuguese Crown

This is a list of Portuguese monarchs who ruled from the establishment of the Kingdom of Portugal, in 1139, to the deposition of the Portuguese monarchy and creation of the Portuguese Republic with the 5 October 1910 revolution.

Through the nea ...

claimed that it had territorial rights in the area visited by Cabot. In 1493 Pope Alexander VI – assuming international jurisdiction – had divided lands discovered in America between Spain and Portugal. The next year, in the Treaty of Tordesillas, these two kingdoms decided to draw the dividing line running north–south, 370 leagues (from approximately depending on the league used) west of the Cape Verde Islands. Land to the west would be Spanish, to the east Portuguese. Given the uncertain geography of the day, this seemed to give the "new founde isle" to Portugal. On the 1502 Cantino map

The Cantino planisphere or Cantino world map is a manuscript Portugal, Portuguese world map preserved at the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, Italy. It is named after Alberto Cantino, an agent for the Ercole I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, Duke of Ferrara ...

, Newfoundland appears on the Portuguese side of the line (as does Brazil). An expedition captured about 60 Aboriginal people as slaves who were said to "resemble gypsies

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sign ...

in colour, features, stature and aspect; are clothed in the skins of various animals ...They are very shy and gentle, but well formed in arms and legs and shoulders beyond description ...." Some captives, sent by Gaspar Corte-Real

Gaspar Corte-Real (1450–1501) was a Portuguese explorer who, alongside his father João Vaz Corte-Real and brother Miguel, participated in various exploratory voyages sponsored by the Portuguese Crown. These voyages are said to have been some o ...

, reached Portugal. The others drowned, with Gaspar, on the return voyage. Gaspar's brother, Miguel Corte-Real

Miguel Corte-Real (; – 1502?) was a Portuguese explorer who charted about 600 miles of the coast of Labrador. In 1502, he disappeared while on an expedition and was believed to be lost at sea.

Early life

Miguel Corte-Real was a son of ...

, went to look for him in 1502, but also failed to return.

In 1604 King

In 1604 King Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarch ...

granted Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons

Pierre Dugua de Mons (or Du Gua de Monts; c. 1558 – 1628) was a French merchant, explorer and colonizer. A Calvinist, he was born in the Château de Mons, in Royan, Saintonge (southwestern France) and founded the first permanent French set ...

a fur-trade monopoly.[

] Dugua led his first colonization expedition to an island located near to the mouth of the St. Croix River. Samuel de Champlain, his geographer, promptly carried out a major exploration of the northeastern coastline of what is now the United States. Under Samuel de Champlain, the Saint Croix settlement moved to Port Royal (today's Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia), a new site across the Bay of Fundy, on the shore of the Annapolis Basin

The Annapolis Basin is a sub-basin of the Bay of Fundy, located on the bay's southeastern shores, along the northwestern shore of Nova Scotia and at the western end of the Annapolis Valley.

The basin takes its name from the Annapolis River, whic ...

, an inlet in western Nova Scotia. Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

became France's most successful colony to that time. The cancellation of Dugua's fur monopoly in 1607 ended the Port Royal settlement. Champlain persuaded First Nations to allow him to settle along the St. Lawrence, where in 1608 he would found France's first permanent colony in Canada at Quebec City. The colony of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

grew slowly, reaching a population of about 5,000 by 1713. New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

had cod

Cod is the common name for the demersal fish genus '' Gadus'', belonging to the family Gadidae. Cod is also used as part of the common name for a number of other fish species, and one species that belongs to genus ''Gadus'' is commonly not call ...

-fishery coastal communities, and farm economies supported communities along the St. Lawrence River. French ''voyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including th ...

'' travelled deep into the hinterlands (of what is today Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba, as well as what is now the American Midwest and the Mississippi Valley

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

), trading with First Nations as they went – guns, gunpowder, cloth, knives, and kettles for beaver furs. The fur trade kept the interest in France's overseas colonies alive, yet only encouraged a small colonial population, as minimal labour was required. The trade also discouraged the development of agriculture, the surest foundation of a colony in the New World.

According to David L. Preston

David L. Preston is an American historian, writer, and professor. He is the author of two books on conflict between English colonists in North America and their French and Native American neighbors, which have won multiple awards. He currently s ...

, after French colonisation with Champlain "the French were able to settle in the depopulated St. Lawrence Valley, not directly intruding on any Indian nation’s lands. This geographic and demographic fact presents a striking contrast to the British colonies’ histories: large numbers of immigrants coming to New England, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the Carolinas all stimulated destructive wars over land with their immediate Indian neighbors...Settlement patterns in New France also curtailed the kind of relentless and destructive expansion and land-grabbing that afflicted many British colonies."

The Métis

The Métis (from French ''métis'' – "mixed") are descendants of unions between Cree, Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

, Saulteaux

The Saulteaux (pronounced , or in imitation of the French pronunciation , also written Salteaux, Saulteau and other variants), otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations band government in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, A ...

, Menominee

The Menominee (; mez, omǣqnomenēwak meaning ''"Menominee People"'', also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as ''Mamaceqtaw'', "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recog ...

and other First Nations in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and Europeans, mainly French. The Métis were historically the children of French fur traders and Nehiyaw women or, from unions of English or Scottish traders and Northern Dene women (Anglo-Métis

A 19th century community of the Métis people of Canada, the Anglo-Métis, more commonly known as Countryborn, were children of fur traders; they typically had Scots (Orcadian, mainland Scottish), or English fathers and Aboriginal mothers.B ...

). The Métis spoke or still speak either Métis French

Métis French (french: français métis), along with Michif and Bungi, is one of the traditional languages of the Métis people, and the French-dialect source of Michif.Bakker. (1997: 85).

Features

Métis French is a variety of Canadian French ...

or a mixed language

A mixed language is a language that arises among a bilingual group combining aspects of two or more languages but not clearly deriving primarily from any single language. It differs from a creole or pidgin language in that, whereas creoles/pidgin ...

called Michif

Michif (also Mitchif, Mechif, Michif-Cree, Métif, Métchif, French Cree) is one of the languages of the Métis people of Canada and the United States, who are the descendants of First Nations (mainly Cree, Nakota, and Ojibwe) and fur trade work ...

. ''Michif'', ''Mechif'' or ''Métchif'' is a phonetic spelling

A phonemic orthography is an orthography (system for writing a language) in which the graphemes (written symbols) correspond to the phonemes (significant spoken sounds) of the language. Natural languages rarely have perfectly phonemic orthographi ...

of the Métis pronunciation of ''Métif'', a variant of ''Métis''. The Métis predominantly speak English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, with French a strong second language, as well as numerous Aboriginal tongues. Métis French is best preserved in Canada, Michif in the United States, notably in the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation

Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation (Ojibwe language: ''Mikinaakwajiwing'') is a reservation located in northern North Dakota, United States. It is the land base for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. The population of the Turtle Moun ...

of North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

, where Michif is the official language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

of the Métis that reside on this Chippewa reservation. The encouragement and use of Métis French and Michif is growing due to outreach within the five provincial Métis councils after at least a generation of steep decline. Canada's Indian and Northern Affairs define Métis to be those persons of mixed First Nation and European ancestry.

Colonial wars

Allied with the French, the first nations of the

Allied with the French, the first nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

of Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

fought six colonial wars against the British and their native allies (See the French and Indian Wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

, Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

and Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Briti ...

). In the second war, Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

, the British conquered Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

(1710). The sixth and final colonial war

Colonial war (in some contexts referred to as small war) is a blanket term relating to the various conflicts that arose as the result of overseas territories being settled by foreign powers creating a colony. The term especially refers to wars ...

between the nations of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

(1754–1763), resulted in the French giving up their claims and the British claimed the lands of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

.

In this final war, the Franco-Indian alliance

The Franco-Indigenous Alliance was an alliance between North American indigenous nations and the French, centered on the Great Lakes and the Illinois country during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). The alliance involved French settlers on ...

brought together Americans, First Nations and the French, centred on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

and the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

.Menominee

The Menominee (; mez, omǣqnomenēwak meaning ''"Menominee People"'', also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as ''Mamaceqtaw'', "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recog ...

, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Mississaugas, Illiniwek

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Ill ...

, Huron-Petun

The Petun (from french: pétun), also known as the Tobacco people or Tionontati ("People Among the Hills/Mountains"), were an indigenous Iroquoian people of the woodlands of eastern North America. Their last known traditional homeland was sou ...

, Potawatomi etc.Ohio valley

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

before the open conflict between the European powers erupted.

In the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, the British recognized the treaty rights of the indigenous populations and resolved to only settle those areas purchased lawfully from the indigenous peoples. Treaties and land purchases were made in several cases by the British, but the lands of several indigenous nations remain unceded and/or unresolved.

Slavery

First Nations routinely captured slaves from neighbouring tribes. Sources report that the conditions under which First Nations slaves lived could be brutal, with the Makah

The Makah (; Klallam: ''màq̓áʔa'')Renker, Ann M., and Gunther, Erna (1990). "Makah". In "Northwest Coast", ed. Wayne Suttles. Vol. 7 of '' Handbook of North American Indians'', ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Instit ...

tribe practicing death by starvation as punishment and Pacific coast tribes routinely performing ritualized killings of slaves as part of social ceremonies into the mid-1800s. Slave-owning tribes of the fishing societies, such as the Yurok

The Yurok (Karuk language: Yurúkvaarar / Yuru Kyara - "downriver Indian; i.e. Yurok Indian") are an Indigenous people from along the Klamath River and Pacific coast, whose homelands are located in present-day California stretching from Trinidad ...

and Haida lived along the coast from what is now Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

to California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. Fierce warrior indigenous slave-traders of the Pacific Northwest Coast raided as far south as California. Slavery was hereditary, the slaves and their descendants being considered prisoners of war. Some tribes in British Columbia continued to segregate and ostracize the descendants of slaves as late as the 1970s. Among Pacific Northwest tribes about a quarter of the population were slaves.Fox nation

Fox Nation is an American subscription video on demand service. Announced on February 20, 2018, and launching on November 27 of that year, it is a companion to Fox News Channel carrying programming of interest to its audience, including origina ...

, a tribe that was an ancient rival of the Miami people

The Miami ( Miami-Illinois: ''Myaamiaki'') are a Native American nation originally speaking one of the Algonquian languages. Among the peoples known as the Great Lakes tribes, they occupied territory that is now identified as North-central Indi ...

and their Algonquian allies.

Native (or "pani", a corruption of Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska ...

) slaves were much easier to obtain and thus more numerous than African slaves in New France, but were less valued. The average native slave died at 18, and the average African slave died at 25Act Against Slavery

The ''Act Against Slavery'' was an anti-slavery law passed on July 9, 1793, in the second legislative session of Upper Canada, the colonial division of British North America that would eventually become Ontario. It banned the importation of sla ...

of 1793 legislated the gradual abolition of slavery: no slaves could be imported; slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at age 25.[

] The Act remained in force until 1833 when the British Parliament's Slavery Abolition Act

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. It was passed by Earl Grey's reforming administrati ...

finally abolished slavery in all parts of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

.[

] Historian Marcel Trudel

Marcel Trudel (May 29, 1917 – January 11, 2011) was a Canadian historian, university professor (1947–1982) and author who published more than 40 books on the history of New France. He brought academic rigour to an area that had been ma ...

has documented 4,092 recorded slaves throughout Canadian history, of which 2,692 were Aboriginal people, owned by the French, and 1,400 blacks owned by the British, together owned by approximately 1,400 masters.

1775–1815

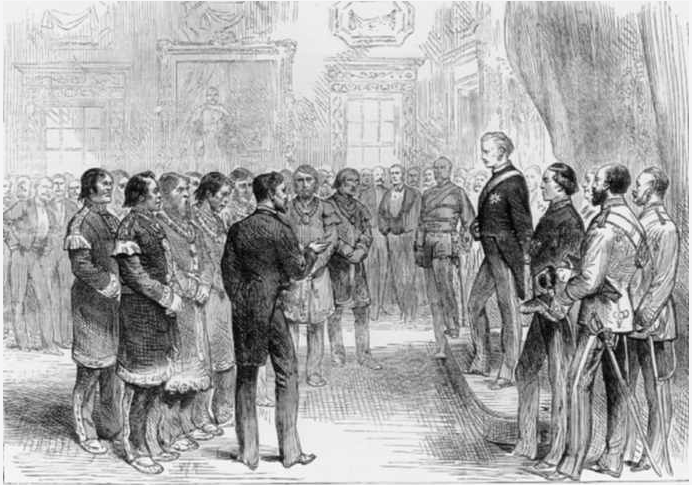

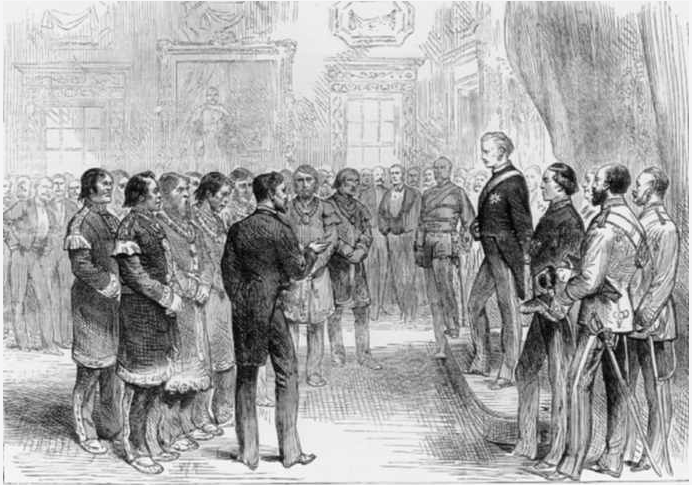

British agents worked to make the First Nations into military allies of the British, providing supplies, weapons, and encouragement. During the

British agents worked to make the First Nations into military allies of the British, providing supplies, weapons, and encouragement. During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

(1775–1783) most of the tribes supported the British. In 1779, the Americans launched a campaign to burn the villages of the Iroquois in New York State. The refugees fled to Fort Niagara and other British posts, with some remaining permanently in Canada. Although the British ceded the Old Northwest to the United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, it kept fortifications and trading posts in the region until 1795. The British then evacuated American territory, but operated trading posts in British territory, providing weapons and encouragement to tribes that were resisting American expansion into such areas as Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois and Wisconsin. Officially, the British agents discouraged any warlike activities or raids on American settlements, but the Americans became increasingly angered, and this became one of the causes of the War of 1812

The origins of the War of 1812 (1812-1815), between the United States and the British Empire and its First Nation allies, have been long debated. The War of 1812 was caused by multiple factors and ultimately led to the US declaration of war o ...

.

In the war, the great majority of First Nations supported the British, and many fought under the aegis of Tecumseh. But Tecumseh died in battle in 1813 and the Indian coalition collapsed. The British had long wished to create a neutral Indian state in the American Old Northwest, and made this demand as late as 1814 at the peace negotiations at Ghent. The Americans rejected the idea, the British dropped it, and Britain's Indian allies lost British support. In addition, the Indians were no longer able to gather furs in American territory. Abandoned by their powerful sponsor, Great Lakes-area natives ultimately assimilated into American society, migrated to the west or to Canada, or were relocated onto reservations in Michigan and Wisconsin. Historians have unanimously agreed that the Indians were the major losers in the War of 1812.

19th century

Living conditions for Indigenous people in the

Living conditions for Indigenous people in the prairie

Prairies are ecosystems considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and a composition of grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the ...

regions deteriorated quickly. Between 1875 and 1885, settlers and hunters of European descent contributed to hunting the North American bison almost to extinction; the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway brought large numbers of European settlers west who encroached on Indigenous territory. European Canadians established governments, police forces, and courts of law

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

with different foundations from indigenous practices. Various epidemics continued to devastate Indigenous communities. All of these factors had a profound effect on Indigenous people, particularly those from the plains who had relied heavily on bison for food and clothing. Most of those nations that agreed to treaties had negotiated for a guarantee of food and help to begin farming.Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

Edgar Dewdney

Edgar Dewdney, (November 5, 1835 – August 8, 1916) was a Canadian surveyor, road builder, Indian commissioner and politician born in Devonshire, England. He emigrated to British Columbia in 1859 in order to act as surveyor for the Dewdney ...

cut rations to indigenous people in an attempt to reduce government costs. Between 1880 and 1885, approximately 3,000 Indigenous people starved to death in the North-Western Territory/ Northwest Territories. Offended by the concepts of the treaties, Cree chiefs resisted them. Big Bear refused to sign

Offended by the concepts of the treaties, Cree chiefs resisted them. Big Bear refused to sign Treaty 6

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specif ...

until starvation among his people forced his hand in 1882.Anglo-Métis

A 19th century community of the Métis people of Canada, the Anglo-Métis, more commonly known as Countryborn, were children of fur traders; they typically had Scots (Orcadian, mainland Scottish), or English fathers and Aboriginal mothers.B ...

) asked Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

to return from the United States, where he had fled after the Red River Rebellion

The Red River Rebellion (french: Rébellion de la rivière Rouge), also known as the Red River Resistance, Red River uprising, or First Riel Rebellion, was the sequence of events that led up to the 1869 establishment of a provisional government by ...

, to appeal to the government on their behalf. The government gave a vague response. In March 1885, Riel, Gabriel Dumont, Honoré Jackson

William Henry Jackson (May 3, 1861 – January 10, 1952), also known as Honoré Jackson or Jaxon, was secretary to Louis Riel during the North-West Rebellion in Canada in 1885. He was married to Aimée, a former teacher in Chicago.

He was ...

(a.k.a. Will Jackson), Crowfoot

Crowfoot (1830 – 25 April 1890) or Isapo-Muxika ( bla, Issapóómahksika, italics=yes; syllabics: ) was a chief of the Siksika First Nation. His parents, (Packs a Knife) and (Attacked Towards Home), were Kainai. He was five years old when ...

, Chief of the Blackfoot First Nation and Chief Poundmaker

Pîhtokahanapiwiyin ( – 4 July 1886), also known as Poundmaker, was a Plains Cree chief known as a peacemaker and defender of his people, the Poundmaker Cree Nation. His name denotes his special craft at leading buffalo into buffalo poun ...

, who after the 1876 negotiations of Treaty 6

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specif ...

split off to form his band. Together, they set up the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan

The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was an independent state declared during the North-West Rebellion of 1885 in the District of Saskatchewan of the North-West Territories. It included parts of the present-day Canadian provinces of Albe ...

, believing that they could influence the federal government in the same way as they had in 1869. The North-West Rebellion of 1885 was a brief and unsuccessful uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

by the Métis people of the District of Saskatchewan

The District of Saskatchewan was a regional administrative district of Canada's North-West Territories. It was formed in 1882 was later enlarged then abolished with the creation of the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1905. Much of the a ...

under Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

against the Dominion of Canada, which they believed had failed to address their concerns for the survival of their people. In 1884, 2,000 Cree from reserves met near Battleford

Battleford ( 2011 population 4,065) is a small town located across the North Saskatchewan River from the City of North Battleford, in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Battleford and North Battleford are collectively referred to as "The Battlefords" b ...

to organise into a large, cohesive resistance. Discouraged by the lack of government response but encouraged by the efforts of the Métis at armed rebellion, Wandering Spirit and other young militant Cree attacked the small town of Frog Lake Frog Lake may refer to:

* Frog Lake, Alberta, a Cree community in Canada, site of the

** Frog Lake Massacre

* Frog Lake (Colchester), a lake of Colchester County, in Nova Scotia, Canada

* Frog Lake (Guysborough), a lake of Guysborough District, i ...

, killing Thomas Quinn, the hated Indian Agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

and eight others.Red River Rebellion

The Red River Rebellion (french: Rébellion de la rivière Rouge), also known as the Red River Resistance, Red River uprising, or First Riel Rebellion, was the sequence of events that led up to the 1869 establishment of a provisional government by ...

of 1869–1870, Métis moved from Manitoba

, image_map = Manitoba in Canada 2.svg

, map_alt = Map showing Manitoba's location in the centre of Southern Canada

, Label_map = yes

, coordinates =

, capital = Winn ...

to the District of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a province in western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dak ...

, where they founded a settlement at Batoche on the South Saskatchewan River

The South Saskatchewan River is a major river in Canada that flows through the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

For the first half of the 20th century, the South Saskatchewan would completely freeze over during winter, creating spectacular ...

.

In Manitoba settlers from

In Manitoba settlers from Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

began to arrive. They pushed for land to be allotted in the square concession system of English Canada

Canada comprises that part of the population within Canada, whether of British origin or otherwise, that speaks English.

The term ''English Canada'' can also be used for one of the following:

#Describing all the provinces of Canada tha ...

, rather than the seigneurial system Seigneurial system may refer to:

* Manorialism - the socio-economic system of the Middle Ages and Early Modern period

* Seigneurial system of New France

The manorial system of New France, known as the seigneurial system (french: Régime seigneu ...

of strips reaching back from a river which the Métis were familiar with in their French-Canadian culture. The buffalo were being hunted to extinction by the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

and other hunters, as for generations the Métis had depended on them as a chief source of food.

Colonization and assimilation

The history of colonization is complex, varied according to the time and place. France and Britain were the main colonial powers involved, though the United States also began to extend its territory at the expense of indigenous people as well.

From the late 18th century, European Canadians encouraged First Nations to assimilate into the European-based culture, referred to as "

The history of colonization is complex, varied according to the time and place. France and Britain were the main colonial powers involved, though the United States also began to extend its territory at the expense of indigenous people as well.

From the late 18th century, European Canadians encouraged First Nations to assimilate into the European-based culture, referred to as "Canadian culture

The culture of Canada embodies the artistic, culinary, literary, humour, musical, political and social elements that are representative of Canadians. Throughout Canada's history, its culture has been influenced by European culture and traditi ...

". The assumption was that this was the "correct" culture because the Canadians of European descent saw themselves as dominant, and technologically, politically and culturally superior.[

] There was resistance against this assimilation and many businesses denied European practices. The Tecumseh Wigwam of Toronto, for example, did not adhere to the widely practiced Lord's Day observance, making it a popular spot, especially on Sundays. These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Founded in the 19th century, the Canadian Indian residential school system

In Canada, the Indian residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. The network was funded by the Canadian government's Department of Indian Affairs and administered by Christian churches. The school s ...

was intended to force the assimilation of Aboriginal and First Nations people into European-Canadian society. The purpose of the schools, which separated children from their families, has been described by commentators as "killing the Indian in the child."[

]

Funded under the '' Indian Act'' by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, a branch of the federal government, the schools were run by churches of various denominations – about 60% by Roman Catholics, and 30% by the Anglican Church of Canada and the

Funded under the '' Indian Act'' by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, a branch of the federal government, the schools were run by churches of various denominations – about 60% by Roman Catholics, and 30% by the Anglican Church of Canada and the United Church of Canada

The United Church of Canada (french: link=no, Église unie du Canada) is a mainline Protestant denomination that is the largest Protestant Christian denomination in Canada and the second largest Canadian Christian denomination after the Catholi ...

, along with its pre-1925 predecessors, Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

, Congregationalist and Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

churches.

The attempt to force assimilation involved punishing children for speaking their own languages or practicing their own faiths, leading to allegations in the 20th century of cultural genocide

Cultural genocide or cultural cleansing is a concept which was proposed by lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944 as a component of genocide. Though the precise definition of ''cultural genocide'' remains contested, the Armenian Genocide Museum defines i ...

and ethnocide

Ethnocide is the extermination of cultures.

Reviewing the legal and the academic history of the usage of the terms genocide and ethnocide, Bartolomé Clavero differentiates them by stating that "Genocide kills people while ethnocide kills socia ...

. There was widespread physical and sexual abuse

Sexual abuse or sex abuse, also referred to as molestation, is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using force or by taking advantage of another. Molestation often refers to an instance of sexual assa ...

. Overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of medical care led to high rates of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

, and death rates of up to 69%. Details of the mistreatment of students had been published numerous times throughout the 20th century, but following the closure of the schools in the 1960s, the work of indigenous activists and historians led to a change in the public perception of the residential school system, as well as official government apologies, and a (controversial) legal settlement.