Fairey Rotodyne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fairey Rotodyne was a 1950s British

''

During 1951 and 1952,

During 1951 and 1952,

On 6 November 1957, the prototype performed its

On 6 November 1957, the prototype performed its

In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies. By delaying or withholding access to defence contracts, the British firms could be forced into mergers;

In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies. By delaying or withholding access to defence contracts, the British firms could be forced into mergers;

"The Fairey Rotodyne."

''Gyrodyne Technology (Groen Brothers Aviation)''. Retrieved: 17 January 2011. though John Farley, chief test pilot of the

"The Fairey Rotodyne: An Idea Whose Time Has Come – Again?"

''gyropilot.co.uk.'' Retrieved: 18 May 2007. * Charnov, Dr. Bruce H. ''From Autogiro to Gyroplane: The Amazing Survival of an Aviation Technology''. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2003. . * Gibbings, David. ''Fairey Rotodyne''. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2009. . * Gibbings, David.

The Fairey Rotodyne-Technology Before its Time?: The 2003 Cierva Lecture.

''The Aeronautical Journal'' (The Royal Aeronautical Society), Vol. 108, No 1089, November 2004. (Presented by David Gibbings and subsequently published in The Aeronautical Journal.) * Green, William and Gerald Pollinger. ''The Observer's Book of Aircraft, 1958 edition''. London: Fredrick Warne & Co. Ltd., 1958. * Hislop, Dr. G.S. "The Fairey Rotodyne." A Paper presented to ''The Helicopter Society of Great Britain and the RAeS'', November 1958.

''Flight International'', 9 August 1962, pp. 200–202.

''

Fairey's promotional video for the Rotodyne on YouTube

a 1957 ''Flight'' article

Why The Vertical Takeoff Airliner Failed: The Rotodyne Story

9min documentary {{Authority control 1950s British airliners 1950s British experimental aircraft Cancelled aircraft projects Experimental helicopters Rotodyne Gyrodynes Slowed rotor VTOL aircraft Tipjet-powered helicopters Aircraft first flown in 1957

compound gyroplane

A gyrodyne is a type of VTOL aircraft with a helicopter rotor-like system that is driven by its engine for takeoff and landing only, and includes one or more conventional propeller or jet engines to provide forward thrust during cruising flight ...

designed and built by Fairey Aviation

The Fairey Aviation Company Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer of the first half of the 20th century based in Hayes in Middlesex and Heaton Chapel and RAF Ringway in Cheshire. Notable for the design of a number of important military a ...

and intended for commercial and military uses."Rotodyne, Fairey's Big Convertiplane Nears Completion: A Detailed Description."''

Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

'', 9 August 1957, Number 2533 Volume 72, pp. 191–197. A development of the earlier Gyrodyne

A gyrodyne is a type of VTOL aircraft with a helicopter rotor-like system that is driven by its engine for takeoff and landing only, and includes one or more conventional propeller (aircraft), propeller or jet engines to provide forward thrust d ...

, which had established a world helicopter speed record, the Rotodyne featured a tip-jet

A tip jet is a jet nozzle at the tip of some helicopter rotor blades, used to spin the rotor, much like a Catherine wheel firework. Tip jets replace the normal shaft drive and have the advantage of placing no torque on the airframe, thus not re ...

-powered rotor that burned a mixture of fuel and compressed air bled from two wing-mounted Napier Eland

The Napier Eland was a British turboshaft or turboprop gas-turbine engine built by Napier & Son in the early 1950s. Production of the Eland ceased in 1961 when the Napier company was taken over by Rolls-Royce.

Design and development

The Eland ...

turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. Fuel ...

s. The rotor was driven for vertical takeoffs, landings and hovering, as well as low-speed translational flight, but autorotated during cruise flight with all engine power applied to two propellers.

One prototype was built. Although the Rotodyne was promising in concept and successful in trials, the programme was eventually cancelled. The termination has been attributed to the type failing to attract any commercial orders; this was in part due to concerns over the high levels of rotor tip jet noise generated in flight. Politics had also played a role in the lack of orders (the project was government funded) which ultimately doomed the project.

Development

Background

From the late 1930s onwards, considerable progress was made on an entirely new field of aeronautics in the form ofrotary-wing aircraft

A rotorcraft or rotary-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft with rotary wings or rotor blades, which generate lift by rotating around a vertical mast. Several rotor blades mounted on a single mast are referred to as a rotor. The Internat ...

.Wood 1975, p. 108. While some progress in Britain had been made prior to the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, wartime priorities placed upon the aviation industry meant that British programmes to develop rotorcraft and helicopters were marginalised at best. In the immediate post-war climate, the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) and Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

elected to procure American-developed helicopters in the form of the Sikorsky R-4

The Sikorsky R-4 is a two-seat helicopter that was designed by Igor Sikorsky with a single, three-bladed main rotor and powered by a radial engine. The R-4 was the world's first large-scale mass-produced helicopter and the first helicopter used by ...

and Sikorsky R-6

The Sikorsky R-6 is an American light two-seat helicopter of the 1940s. In Royal Air Force and Royal Navy service, it was named the Hoverfly II.

Development

The R-6/Hoverfly II was developed to improve on the successful Sikorsky R-4. In order to ...

, known locally as the ''Hoverfly I'' and ''Hoverfly II'' respectively. Experience from the operation of these rotorcraft, along with the extensive examination that was conducted upon captured German helicopter prototypes, stimulated considerable interest within the armed services and industry alike in developing Britain's own advanced rotorcraft.

Fairey Aviation was one such company that was intrigued by the potential of rotary-wing aircraft, and proceeded to develop the Fairey FB-1 Gyrodyne

The Fairey FB-1 Gyrodyne is an experimental British rotorcraft that used single lifting rotor and a tractor propeller mounted on the tip of the starboard stub wing to provide both propulsion and anti-torque reaction.

Design and development

In ...

in accordance with Specification E.16/47.Wood 1975, pp. 108-111. The Gyrodyne was a unique aircraft in its own right that defined a third type of rotorcraft, including autogyro

An autogyro (from Greek and , "self-turning"), also known as a ''gyroplane'', is a type of rotorcraft that uses an unpowered rotor in free autorotation to develop lift. Forward thrust is provided independently, by an engine-driven propeller. Whi ...

and helicopter. Having little in common with the later Rotodyne, it was characterised by its inventor, Dr JAJ Bennett, formerly chief technical officer of the pre-Second World War Cierva Autogiro Company as an intermediate aircraft designed to combine the safety and simplicity of the autogyro with hovering performance. Its rotor was driven in all phases of flight with collective pitch being an automatic function of shaft torque, with a side-mounted propeller providing both thrust for forward flight and rotor torque correction. On 28 June 1948, the FB-1 proved its potential during test flights when it achieved a world airspeed record, having attaining a recorded speed of .Wood 1975, p. 111. The programme was not trouble-free however, a fatal accident involving one of the prototypes occurring in April 1949 due to poor machining of a rotor blade flapping link retaining nut. The second FB-1 was modified to investigate a tip-jet driven rotor with propulsion provided by propellers mounted at the tip of each stub wing, being renamed the Jet Gyrodyne.

During 1951 and 1952,

During 1951 and 1952, British European Airways

British European Airways (BEA), formally British European Airways Corporation, was a British airline which existed from 1946 until 1974.

BEA operated to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East from airports around the United Kingdom. The a ...

(BEA) internally formulated its own requirement for a passenger-carrying rotorcraft, commonly referred to the ''Bealine-Bus'' or ''BEA Bus''.Wood 1975, p. 116. This was to be a multi-engined rotorcraft capable of serving as a short-haul airliner, BEA envisioned the type as being typically flown between major cities and carrying a minimum of 30 passengers in order to be economical; keen to support the initiative, the Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

proceeded to sponsor a series of design studies to be conducted in support of the BEA requirement. Both civil and government bodies had predicted the requirement for such rotorcraft, and viewed it as being only a matter of time before they would become commonplace in Britain's transport network.

The BEA Bus requirement was met with a variety of futuristic proposals; both practical and seemingly impractical submissions were made by a number of manufacturers. Amongst these, Fairey had also chosen to submit its designs and to participate to meet the requirement; according to aviation author Derek Wood: "one design, particularly, seemed to show promise and this was the Fairey Rotordyne". Fairey had produced multiple arrangements and configurations for the aircraft, typically varying in the powerplants used and the internal capacity; the firm made its first submission to the Ministry on 26 January 1949. Within two months, Fairey had produced a further three alternative submissions, centring on the use of engines such as the Rolls-Royce Dart

The Rolls-Royce RB.53 Dart is a turboprop engine designed and manufactured by Rolls-Royce Limited. First run in 1946, it powered the Vickers Viscount on its maiden flight in 1948. A flight on July 29 of that year, which carried 14 paying passe ...

and Armstrong Siddeley Mamba. In October 1950, an initial contract for the development of a 16,000 lb, four-bladed rotorcraft was awarded.Wood 1975, p. 117. The Fairey design, which was considerably revised over the years, received government funding to support its development.

Early on in development, Fairey found that securing access to engines to power its design proved to be difficult. In November 1950, Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

chairman Lord Hives protested that the design resources of his company were being stretched too thinly across multiple projects; accordingly, the initially-selected Dart engine was switched to the Mamba engine of rival firm Armstrong Siddeley

Armstrong Siddeley was a British engineering group that operated during the first half of the 20th century. It was formed in 1919 and is best known for the production of luxury vehicles and aircraft engines.

The company was created following ...

. By July 1951, Fairey had re-submitted proposals using the Mamba engine in two and three-engine layouts, supporting all-up weights of and respectively; the adopted configuration of pairing the Mamba engine to auxiliary compressors was known as the ''Cobra''. Due to complaints by Armstrong Siddeley that it too was lacking resources, Fairey also proposed the alternative use of engines such as the de Havilland Goblin

The de Havilland Goblin, originally designated as the Halford H-1, is an early turbojet engine designed by Frank Halford and built by de Havilland. The Goblin was the second British jet engine to fly, after Whittle's Power Jets W.1, and the f ...

and the Rolls-Royce Derwent

The Rolls-Royce RB.37 Derwent is a 1940s British centrifugal compressor turbojet engine, the second Rolls-Royce jet engine to enter production. It was an improved version of the Rolls-Royce Welland, which itself was a renamed version of Fran ...

turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, and ...

to drive the forward propellers.

Fairey did not enjoy a positive relationship with de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

however, and thus chose to turn to D. Napier & Son and its Eland turboshaft

A turboshaft engine is a form of gas turbine that is optimized to produce shaftpower rather than jet thrust. In concept, turboshaft engines are very similar to turbojets, with additional turbine expansion to extract heat energy from the exhaust ...

engine in April 1953. Following the selection of the Eland, the basic design of the rotorcraft, known as the ''Rotodyne Y'', soon emerged; it was powered by a pair of Eland N.El.3 engines furnished with auxiliary compressors and a large-section four-blade main rotor, with a projected all-up weight of 33,000 lb. At the same time, a projected enlarged version, designated as the ''Rotodyne Z'', outfitted with more powerful Eland N.El.7 engines and an all-up weight of 39,000 lb, was proposed as well.Wood 1975, pp. 117-118.

Contract

In April 1953, theMinistry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

contracted for the building of a single prototype of the Rotodyne Y, powered by the Eland engine, later designated with the serial number

A serial number is a unique identifier assigned incrementally or sequentially to an item, to ''uniquely'' identify it.

Serial numbers need not be strictly numerical. They may contain letters and other typographical symbols, or may consist enti ...

''XE521'', for research purposes. As contracted, the Rotodyne would have been the largest transport helicopter of its day, seating a maximum of 40 to 50 passengers, while possessing a cruise speed of 150 mph and a range of 250 nautical miles. At the time of the award, Fairey had estimated that £710,000 would cover the costs of producing the airframe. With a view to an aircraft that would meet regulatory approval in the shortest time, Fairey's designers worked to meet the Civil Airworthiness Requirements for both helicopters and similar-sized twin-engined aircraft. A one-sixth scale rotorless model was extensively wind tunnel tested for fixed-wing performance. A smaller (1/15th-scale) model with a powered rotor was used for downwash investigations.

While the prototype was being built, funding for the programme reached a crisis. Cuts in defence spending led the Ministry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

to withdraw its support, pushing the burden of the costs onto any possible civilian customer. The government agreed to maintain funding for the project only if, among other qualifications, Fairey and Napier (through their parent English Electric

N.º UIC: 9094 110 1449-3 (Takargo Rail)

The English Electric Company Limited (EE) was a British industrial manufacturer formed after the Armistice of 11 November 1918, armistice of World War I by amalgamating five businesses which, during th ...

) contributed to development costs of the Rotodyne and the Eland engine respectively. As a result of disagreements with Fairey on matters of policy, Dr Bennett left the firm to join Hiller Helicopters

Hiller Aircraft Company was founded in 1942 as Hiller Industries by Stanley Hiller to develop helicopters.

History

Stanley Hiller, then seventeen, established the first helicopter factory on the West Coast of the United States, located in Berkele ...

in California; responsibility for the Rotodyne's development was assumed by Dr George S Hislop, who became the firm's chief engineer.Wood 1975, p. 118.

The manufacturing of the prototype's fuselage, wings, and rotor assembly was conducted at Fairey's facility in Hayes, Hillingdon

Hayes is a town in west London, historically situated within the county of Middlesex, and now part of the London Borough of Hillingdon. The town's population, including its localities Hayes End, Harlington and Yeading, was recorded as 83,564 i ...

, West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North London ...

, while construction of the tail assembly was performed at the firm's factory in Stockport

Stockport is a town and borough in Greater Manchester, England, south-east of Manchester, south-west of Ashton-under-Lyne and north of Macclesfield. The River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey here.

Most of the town is within ...

, Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester is a metropolitan county and combined authority, combined authority area in North West England, with a population of 2.8 million; comprising ten metropolitan boroughs: City of Manchester, Manchester, City of Salford, Salford ...

and final assembly was performed at White Waltham Airfield

White Waltham Airfield is an operational general aviation aerodrome located at White Waltham, southwest of Maidenhead, in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England.

This large grass airfield is best known for its asso ...

, Maidenhead

Maidenhead is a market town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in the county of Berkshire, England, on the southwestern bank of the River Thames. It had an estimated population of 70,374 and forms part of the border with southern Bu ...

. In addition, a full-scale static test rig was produced at RAF Boscombe Down

MoD Boscombe Down ' is the home of a military aircraft testing site, on the southeastern outskirts of the town of Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. The site is managed by QinetiQ, the private defence company created as part of the breakup of the Def ...

to support the programme; the static rig featured a fully operational rotor and powerplant arrangement which was demonstrated on multiple occasions, including a 25-hour approval testing for the Ministry.Wood 1975, pp. 118-119.

While construction of the first prototype was underway, prospects for the Rotodyne appeared positive; according to Wood, there was interest in the type from both civil and military quarters.Wood 1975, p. 119. BEA was monitoring the progress of the programme with interest; it was outwardly expected that the airline would place an order shortly after the issuing of an order for a militarised version of the rotorcraft. The American company Kaman Helicopters also showed strong interest in the project, and was known to have studied it closely as the firm considered the potential for licensed production Licensed production is the production under license of technology developed elsewhere. The licensee provides the licensor of a specific product with legal production rights, technical information, process technology, and any other proprietary compon ...

of the Rotodyne for both civil and military customers.

Due to army and RAF interest, development of the Rotodyne had been funded out of the defence budget for a time.Wood 1975, pp. 119-120. During 1956, the Defence Research Policy Committee had declared that there was no military interest in the type, which quickly led to the Rotodyne becoming solely reliant upon civil budgets as a research/civil prototype aircraft instead.Wood 1975, pp. 119-120. After a series of political arguments, proposals, and bargaining; in December 1956, HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

authorised work on both the Rotodyne and Eland engine to be continued until the end of September 1957. Amongst the demands exerted by the Treasury were that the aircraft had to be both a technical success and would need to acquire a firm order from BEA; both Fairey and English Electric

N.º UIC: 9094 110 1449-3 (Takargo Rail)

The English Electric Company Limited (EE) was a British industrial manufacturer formed after the Armistice of 11 November 1918, armistice of World War I by amalgamating five businesses which, during th ...

(Napier's parent company) also had to take on a portion of the costs for its development as well.Wood 1975, p. 120.

Testing and evaluation

On 6 November 1957, the prototype performed its

On 6 November 1957, the prototype performed its maiden flight

The maiden flight, also known as first flight, of an aircraft is the first occasion on which it leaves the ground under its own power. The same term is also used for the first launch of rockets.

The maiden flight of a new aircraft type is alwa ...

, piloted by chief helicopter test pilot Squadron Leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is also ...

W. Ron Gellatly and assistant chief helicopter test pilot Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

John G.P. Morton as second pilot. The first flight had originally been projected to take place in 1956; however, delay was viewed as inevitable with an entirely new concept such as used by the Rotodyne.

On 10 April 1958, the Rotodyne achieved its first successful transition from vertical to horizontal and then back into vertical flight. On 5 January 1959, the Rotodyne set a world speed record in the convertiplane category, at 190.9 mph (307.2 km/h), over a 60-mile (100 km) closed circuit. As well as being fast, the rotorcraft had a safety feature: it could hover with one engine shut down with its propeller feathered, and the prototype demonstrated several landings as an autogyro. The prototype was demonstrated several times at the Farnborough and Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

air shows, regularly amazing onlookers. In one instance, it even lifted a 100 ft girder bridge.

The Rotodyne's tip drive and unloaded rotor made its performance far better when compared to pure helicopters and other forms of "convertiplanes." The aircraft could be flown at 175 kn (324 km/h) and pulled into a steep climbing turn without demonstrating any adverse handling characteristics.

Throughout the world, interest was growing in the prospect of direct city-to-city transport. The market for the Rotodyne was that of a medium-haul "flying bus": It would take off vertically from an inner-city heliport

A heliport is a small airport suitable for use by helicopters and some other vertical lift aircraft. Designated heliports typically contain one or more touchdown and liftoff areas and may also have limited facilities such as fuel or hangars. I ...

, with all lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

coming from the tip-jet driven rotor, and then would increase airspeed, eventually with all power from the engines being transferred to the propellers

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

with the rotor autorotating. In this mode, the collective pitch

A helicopter pilot manipulates the helicopter flight controls to achieve and maintain controlled aerodynamic flight. Changes to the aircraft flight control system transmit mechanically to the rotor, producing aerodynamic effects on the rotor bla ...

, and hence drag, of the rotor could be reduced, as the wings would be taking as much as half of the craft's weight. The Rotodyne would then cruise at speeds of about 150 kn (280 km/h) to another city, ''e.g.'', London to Paris, where the rotor tip-jet system would be restarted for landing vertically in the city centre. When the Rotodyne landed and the rotor stopped moving, its blades drooped downward from the hub. To avoid striking the vertical stabiliser

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, sta ...

s on startup, the tips of these fins were angled down to the horizontal. They were raised once the rotor had spun up.

By January 1959, British European Airways

British European Airways (BEA), formally British European Airways Corporation, was a British airline which existed from 1946 until 1974.

BEA operated to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East from airports around the United Kingdom. The a ...

(BEA) announced that it was interested in the purchase of six aircraft, with a possibility of up to 20, and had issued a letter of intent

A letter of intent (LOI or LoI, or Letter of Intent) is a document outlining the understanding between two or more parties which they intend to formalize in a contract, legally binding agreement. The concept is similar to a Heads of agreement ( ...

stating such, on the condition that all requirements, including noise levels, were met.Wood 1975, p. 121. The Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) had also placed an order for 12 military transport versions. New York Airways

New York Airways was a helicopter airline in the New York City area, founded in 1949 as a mail and cargo carrier. On 9 July 1953 it may have been the first scheduled helicopter airline to carry passengers in the United States, with headquarters ...

signed a letter of intent for the purchase of five at $2m each, with an option of 15 more albeit with qualifications, after calculating that a larger Rotodyne could operate at half the seat mile cost of helicopters; however, unit costs were deemed too high for very short hauls of 10 to 50 miles, and the Civil Aeronautics Board

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) was an agency of the federal government of the United States, formed in 1938 and abolished in 1985, that regulated aviation services including scheduled passenger airline serviceStringer, David H."Non-Skeds: Th ...

was opposed to rotorcraft competing with fixed-wing on longer routes. Japan Air Lines

, also known as JAL (''Jaru'') or , is an international airline and Japan's flag carrier and largest airline as of 2021 and 2022, headquartered in Shinagawa, Tokyo. Its main hubs are Tokyo's Narita International Airport and Haneda Airport, as w ...

, which had sent a team to Britain to evaluate the Rotodyne prototype, stated it would experiment with Rotodyne between Tokyo Airport and the city itself, and was interested in using it on the Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

-Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

route as well.

According to rumours, the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

was also interested in buying around 200 Rotodynes. Fairey was keen to secure funding from the American Mutual Aid programme, but could not persuade the RAF to order the minimum necessary 25 rotorcraft needed; at one point, the firm even considered providing a single Rotodyne to Eastern Airlines

Eastern Air Lines, also colloquially known as Eastern, was a major United States airline from 1926 to 1991. Before its dissolution, it was headquartered at Miami International Airport in an unincorporated area of Miami-Dade County, Florida.

Ea ...

via Kaman Helicopters, Fairey's U.S. licensee, so that it could be hired out to the U.S. Army for trials. All Rotodynes destined for US customers were to have been manufactured by Kaman in Bloomfield, Connecticut.

Financing from the government had been secured again on the proviso that firm orders would be gained from BEA. The civilian orders were dependent on the noise issues being satisfactorily met; the importance of this factor had led to Fairey developing 40 different noise suppressors by 1955. In December 1955, Dr Hislop said he was certain that the noise issue could be 'eliminated'. According to Wood, the two most serious problems revealed with the Rotodyne during flight testing was the noise issue and the weight of the rotor system, the latter being 2,233 lb above the original projection of 3,270 lb.

Issues and cancellation

In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies. By delaying or withholding access to defence contracts, the British firms could be forced into mergers;

In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies. By delaying or withholding access to defence contracts, the British firms could be forced into mergers; Duncan Sandys

Edwin Duncan Sandys, Baron Duncan-Sandys (; 24 January 1908 – 26 November 1987), was a British politician and minister in successive Conservative governments in the 1950s and 1960s. He was a son-in-law of Winston Churchill and played a key ro ...

, Minister of Aviation

The Ministry of Aviation was a department of the United Kingdom government established in 1959. Its responsibilities included the regulation of civil aviation and the supply of military aircraft, which it took on from the Ministry of Supply. ...

, expressed this policy to Fairey and made it known that the price of continued government backing for the Rotodyne would be for Fairey to virtually withdraw from all other initiatives in the aviation field.Wood 1975, p. 122. Ultimately, Saunders-Roe

Saunders-Roe Limited, also known as Saro, was a British aero- and marine-engineering company based at Columbine Works, East Cowes, Isle of Wight.

History

The name was adopted in 1929 after Alliott Verdon Roe (see Avro) and John Lord took a co ...

and the helicopter division of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

were incorporated with Westland Westland or Westlands may refer to:

Places

*Westlands, an affluent neighbourhood in the city of Nairobi, Kenya

* Westlands, Staffordshire, a suburban area and ward in Newcastle-under-Lyme

*Westland, a peninsula of the Shetland Mainland near Vaila ...

; in May 1960, Fairey Aviation

The Fairey Aviation Company Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer of the first half of the 20th century based in Hayes in Middlesex and Heaton Chapel and RAF Ringway in Cheshire. Notable for the design of a number of important military a ...

was also taken over by Westland. By this time, the Rotodyne had flown almost 1,000 people for 120 hours in 350 flights and conducted a total of 230 transitions between helicopter and autogiro — with no accidents.

By 1958, the Treasury was already expressing its opposition to further financing for the programme. The matter was escalated to Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as "Supermac", he ...

, the then Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, who wrote to Aubrey Jones

Aubrey Jones (20 November 1911 – 10 April 2003) was a British Conservative politician who served as Member of Parliament for Birmingham Hall Green from 1950 to 1965.

Early life

Jones was born in Penydarren. He attended Cyfarthfa Castle Second ...

, the Minister of Supply

The Minister of Supply was the minister in the British Government responsible for the Ministry of Supply, which existed to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to the national armed forces. The position was campaigned for by many sceptics of the for ...

, on 6 June 1958, stating that "this project must not be allowed to die". Considerable importance was placed upon BEA supporting the Rotodyne by issuing an order; however, the airline refused to procure the aircraft until it was satisfied that guarantees were given over its performance, economy, and noise criteria. Shortly after Fairey's merger with Westland, the latter was issued a £4 million development contract for the Rotodyne, which was intended to see the type enter service with BEA as a result.

As flight testing with the Rotodyne prototype had proceeded, Fairey had become increasingly dissatisfied with Napier and the Eland engine as progress to improve the latter had been less than expected. For the extended 48-seat model of the Rotodyne to be achieved, the uprated 3,500 ehp Eland N.E1.7 would be necessary; of the estimated £7 million needed to produce the larger aircraft, £3 million would be for its engines. BEA was particularly supportive of a larger aircraft, potentially seating as many as 66 passengers, which would have required a still-far greater sum of money to achieve. Fairey was already struggling to achieve the stated performance of the Eland engine and had resorted to adopting a richer fuel mixture to get the necessary power, a side effect of which was to further aggravate the noticeable noise issue as well as reducing fuel efficiency.Wood 1975, pp. 120-121. As a result of being unable to resolve the issues with the Eland, Fairey opted to adopt the rival Rolls-Royce Tyne

The Rolls-Royce RB.109 Tyne is a twin-shaft turboprop engine developed in the mid to late 1950s by Rolls-Royce Limited to a requirement for the Vickers Vanguard airliner. It was first test flown during 1956 in the nose of a modified Avro Linc ...

turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. Fuel ...

engine to power the larger Rotodyne Z instead.Wood 1975, pp. 121-122.

The larger Rotodyne Z design could be developed to take 57 to 75 passengers and, when equipped with the Tyne engines (5,250 shp/3,910 kW), would have a projected cruising speed of 200 kn (370 km/h). It would be able to carry nearly 8 tons (7 tonnes) of freight; cargoes could have included some British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

vehicles and even the intact fuselage of some fighter aircraft that would fit into its fuselage.Wood 1975, pp. 122-124. It would have also been able to carry large cargoes externally as an aerial crane, including vehicles and whole aircraft. According to some of the later proposals, the Rotodyne Z would have had a gross weight of 58,500 lb, an extended rotor diameter of 109 ft, and a tapered wing with a span of 75 ft.Wood 1975, p. 124.

However, the Tyne engines were also starting to appear under-powered for the larger design. The Ministry of Supply had pledged to finance 50 per cent of the development costs for both the Rotodyne Z and for the model of the Tyne engine to power it.Wood 1975, p. 122. Despite the strenuous efforts of Fairey to achieve its support, the expected order from the RAF did not materialise — at the time, the service had no particular interest in the design, being more focused on effectively addressing the issue of nuclear deterrence

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy ...

. As the trials continued, both the associated costs and the weight of the Rotodyne continued to climb; the noise issue continued to persist, although, according to Wood: "there were signs that silencers would later reduce it to an acceptable level".

While the costs of development were shared half-and-half between Westland and the government, the firm determined that it would still need to contribute a further £9 million in order to complete development and achieve production-ready status. Following the issuing of a requested quotation to the British government for 18 production Rotodynes, 12 for the RAF and 6 for BEA, the government responded that no further support would be issued for the project, for economic reasons. Accordingly, on 26 February 1962, official funding for the Rotodyne was terminated in early 1962.Wood 1975, pp. 124-125. The project's final end came when BEA chose to decline placing its own order for the Rotodyne, principally because of its concerns regarding the high-profile tip-jet noise issue. The corporate management at Westland determined that further development of the Rotodyne towards production status would not be worth the investment required. Thus ended all work on the world's first vertical take-off military/civil transport rotorcraft.Wood 1975, p. 125.

After the programme was terminated, the prototype Rotodyne itself, which was government property, was dismantled and largely destroyed in a fashion reminiscent of the Bristol Brabazon

The Bristol Type 167 Brabazon was a large British piston-engined propeller-driven airliner designed by the Bristol Aeroplane Company to fly transatlantic routes between the UK and the United States. The type was named ''Brabazon'' after th ...

. A single fuselage bay, as pictured, plus rotors and rotorhead mast survived, and are on display at The Helicopter Museum

The Helicopter Museum in Weston-super-Mare, North Somerset, England, is a museum featuring a collection of more than 80 helicopters and autogyros from around the world, both civilian and military. It is based at the southeastern corner of the fo ...

, Weston-super-Mare.

Analysis

The one great criticism of the Rotodyne was the noise the tip jets made; however, the jets were only run at full power for a matter of minutes during departure and landing and, indeed, the test pilot Ron Gellatly made two flights over central London and several landings and departures at Battersea Heliport with no complaints being registered,Anders, Frank"The Fairey Rotodyne."

''Gyrodyne Technology (Groen Brothers Aviation)''. Retrieved: 17 January 2011. though John Farley, chief test pilot of the

Hawker Siddeley Harrier

The Hawker Siddeley Harrier is a British military aircraft. It was the first of the Harrier series of aircraft and was developed in the 1960s as the first operational ground attack and reconnaissance aircraft with vertical/short takeoff and ...

later commented:

From two miles away it would stop a conversation. I mean, the noise of those little jets on the tips of the rotor was just indescribable. So what have we got? The noisiest hovering vehicle the world has yet come up with and you're going to stick it in the middle of a city?There had been a noise-reduction programme in process which had managed to reduce the noise level from 113 dB to the desired level of 96 dB from 600 ft (180 m) away, less than the noise made by a

London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent ceremonial counties of England, counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and He ...

train, and at the time of cancellation, silencers were under development, which would have reduced the noise even further — with 95 dB at 200 ft "foreseen", the limitation being the noise created by the rotor itself. This effort, however, was insufficient for BEA which, as expressed by Chairman Sholto Douglas

Sholto Douglas was the mythical progenitor of Clan Douglas, a powerful and warlike family in medieval Scotland.

A mythical battle took place: "in 767, between King '' Solvathius'' rightful king of Scotland and a pretender ''Donald Bane''. The vic ...

, "would not purchase an aircraft that could not be operated due to noise", and the airline refused to order the Rotodyne, which in turn led to the collapse of the project.

It is only relatively recently that interest has been reestablished in direct city-to-city helicopter transport, with aircraft such as the AgustaWestland AW609

The AgustaWestland (now Leonardo) AW609, formerly the Bell/Agusta BA609, is a twin-engined tiltrotor VTOL aircraft with a configuration similar to that of the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey. It is capable of landing vertically like a helicopter whil ...

and the CarterCopter

The CarterCopter is an experimental compound autogyro developed by Carter Aviation Technologies in the United States to demonstrate slowed rotor technology. On 17 June 2005, the CarterCopter became the first rotorcraft to achieve mu-1 (μ=1), an ...

/ PAV. The 2010 Eurocopter X3

Airbus Helicopters SAS (formerly Eurocopter Group) is the helicopter manufacturing division of Airbus. It is the largest in the industry in terms of revenues and turbine helicopter deliveries. Its head office is located at Marseille Provence Ai ...

experimental helicopter shares the general configuration of the Rotodyne, but is much smaller. A number of innovative gyrodyne designs are still being considered for future development.

Design

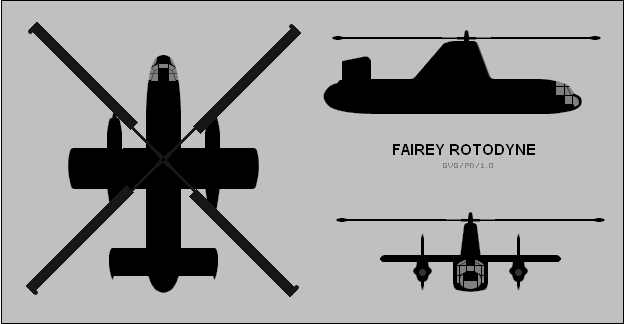

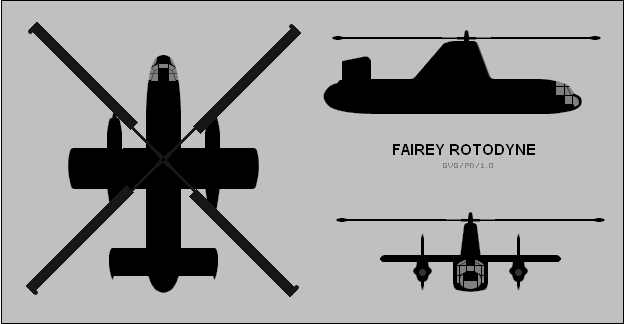

The Fairey Rotodyne was a large hybrid rotorcraft termedcompound gyroplane

A gyrodyne is a type of VTOL aircraft with a helicopter rotor-like system that is driven by its engine for takeoff and landing only, and includes one or more conventional propeller or jet engines to provide forward thrust during cruising flight ...

. According to Wood, it was "the largest transport helicopter of its day". It featured an unobstructed rectangular fuselage, capable of seating between 40 and 50 passengers; a pair of double- clamshell doors were placed to the rear of the main cabin so that freight and even vehicles could be loaded and unloaded.

The Rotodyne had a large, four-bladed rotor

Rotor may refer to:

Science and technology

Engineering

*Rotor (electric), the non-stationary part of an alternator or electric motor, operating with a stationary element so called the stator

* Helicopter rotor, the rotary wing(s) of a rotorcraft ...

and two Napier Eland

The Napier Eland was a British turboshaft or turboprop gas-turbine engine built by Napier & Son in the early 1950s. Production of the Eland ceased in 1961 when the Napier company was taken over by Rolls-Royce.

Design and development

The Eland ...

N.E.L.3 turboprops, one mounted under each of the fixed wings. The rotor blades were a symmetrical aerofoil around a load-bearing spar. The aerofoil was made of steel and light alloy because of centre of gravity concerns. Equally, the spar was formed from a thick machined steel block to the fore and a lighter thinner section formed from folded and riveted steel to the rear. The compressed air was channelled through three steel tubes within the blade. The tip-jet combustion chambers were composed of Nimonic 80, complete with liners that were made from Nimonic 75.

For takeoff and landing, the rotor was driven by tip-jets. The air was produced by compressors driven through a clutch off the main engines. This was fed through ducting in the leading edge of the wings and up to the rotor head. Each engine supplied air for a pair of opposite rotors; the compressed air was mixed with fuel and burned. As a torqueless rotor system, no anti-torque correction system was required, though propeller pitch was controlled by the rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally aircraft, air or watercraft, water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to ...

pedals for low-speed yaw control. The propellers provided thrust for translational flight while the rotor autorotated. The cockpit controls included a cyclic and collective pitch lever, as in a conventional helicopter.Winchester 2005, p. 97.

The transition between helicopter and autogyro modes of flight would have taken place around 60 mph, (other sources state that this would have occurred around 110 knotsGibbings 2004, p. 568.); the transition would have been accomplished by extinguishing the tip-jets. During autogyro flight, up to half of the rotocraft's aerodynamic lift was provided by the wings, which also enabled it to attain higher speed.

Specifications (Rotodyne "Y")

See also

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Charnov, Dr. Bruce H"The Fairey Rotodyne: An Idea Whose Time Has Come – Again?"

''gyropilot.co.uk.'' Retrieved: 18 May 2007. * Charnov, Dr. Bruce H. ''From Autogiro to Gyroplane: The Amazing Survival of an Aviation Technology''. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2003. . * Gibbings, David. ''Fairey Rotodyne''. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: The History Press, 2009. . * Gibbings, David.

The Fairey Rotodyne-Technology Before its Time?: The 2003 Cierva Lecture.

''The Aeronautical Journal'' (The Royal Aeronautical Society), Vol. 108, No 1089, November 2004. (Presented by David Gibbings and subsequently published in The Aeronautical Journal.) * Green, William and Gerald Pollinger. ''The Observer's Book of Aircraft, 1958 edition''. London: Fredrick Warne & Co. Ltd., 1958. * Hislop, Dr. G.S. "The Fairey Rotodyne." A Paper presented to ''The Helicopter Society of Great Britain and the RAeS'', November 1958.

''Flight International'', 9 August 1962, pp. 200–202.

''

Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

'', 9 August 1957, pp. 191–197.

* Taylor, H.A. ''Fairey Aircraft since 1915''. London: Putnam, 1974. .

* Taylor, John W. R. ''Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1961–62''. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1961.

* Taylor, John W.R. ''Jane's Pocket Book of Research and Experimental Aircraft''. London: Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd, 1976. .

* Winchester, Jim, ed. "Fairey Rotodyne." ''Concept Aircraft'' (The Aviation Factfile). Rochester, Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2005. .

* Wood, Derek. ''Project Cancelled''. Macdonald and Jane's Publishers, 1975. .

External links

Fairey's promotional video for the Rotodyne on YouTube

a 1957 ''Flight'' article

Why The Vertical Takeoff Airliner Failed: The Rotodyne Story

9min documentary {{Authority control 1950s British airliners 1950s British experimental aircraft Cancelled aircraft projects Experimental helicopters Rotodyne Gyrodynes Slowed rotor VTOL aircraft Tipjet-powered helicopters Aircraft first flown in 1957