Ecovirology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Virology is the

Virology is the

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their

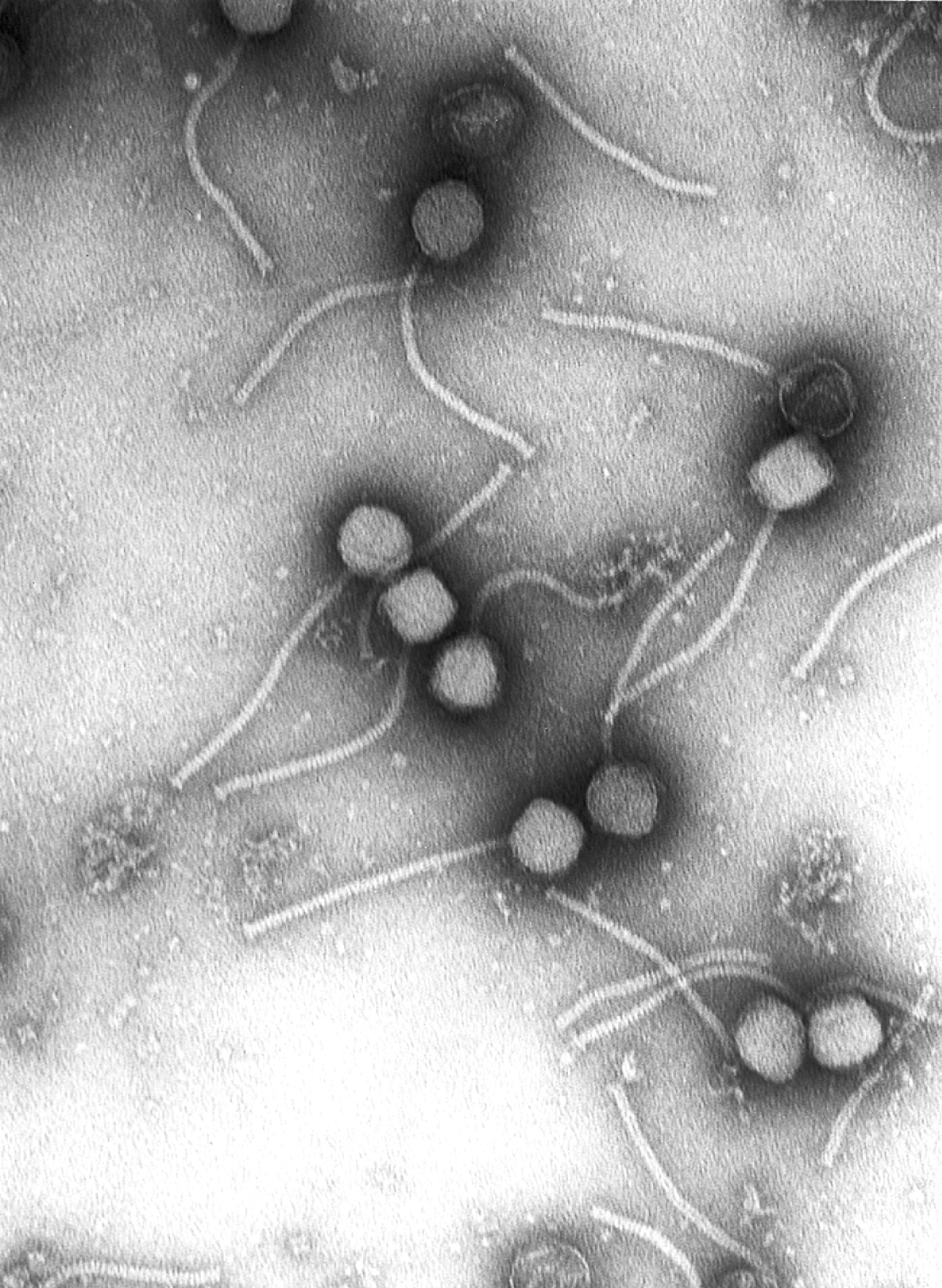

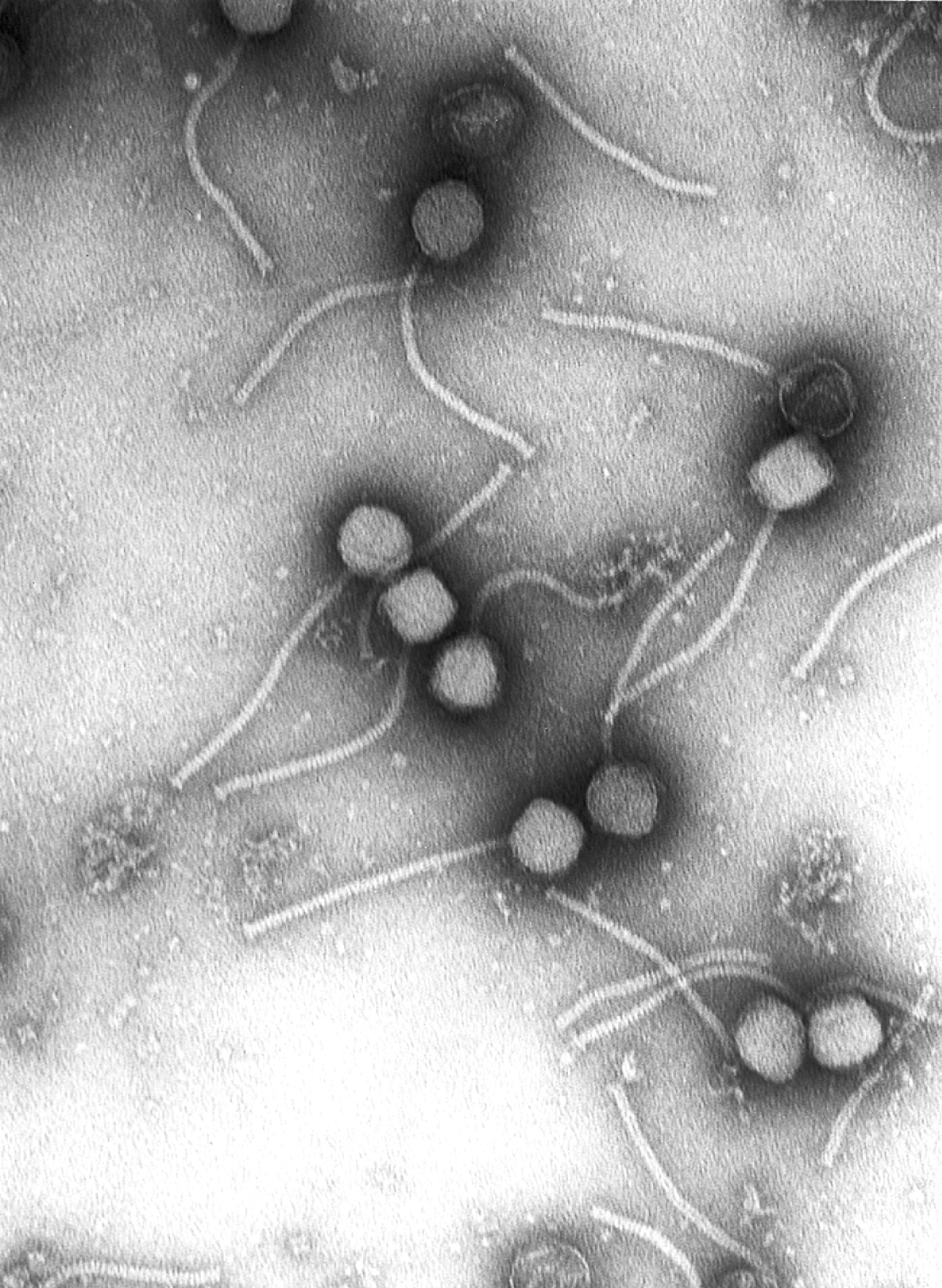

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of

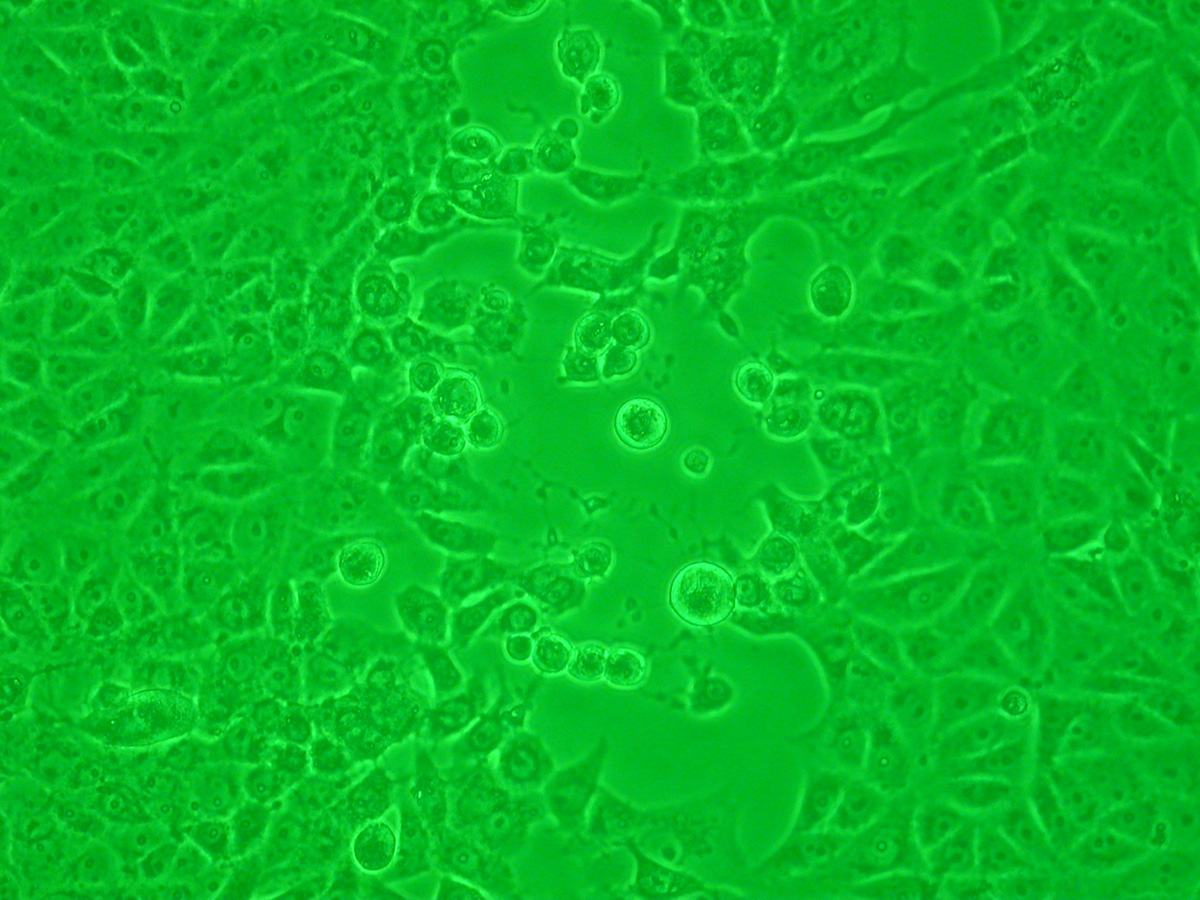

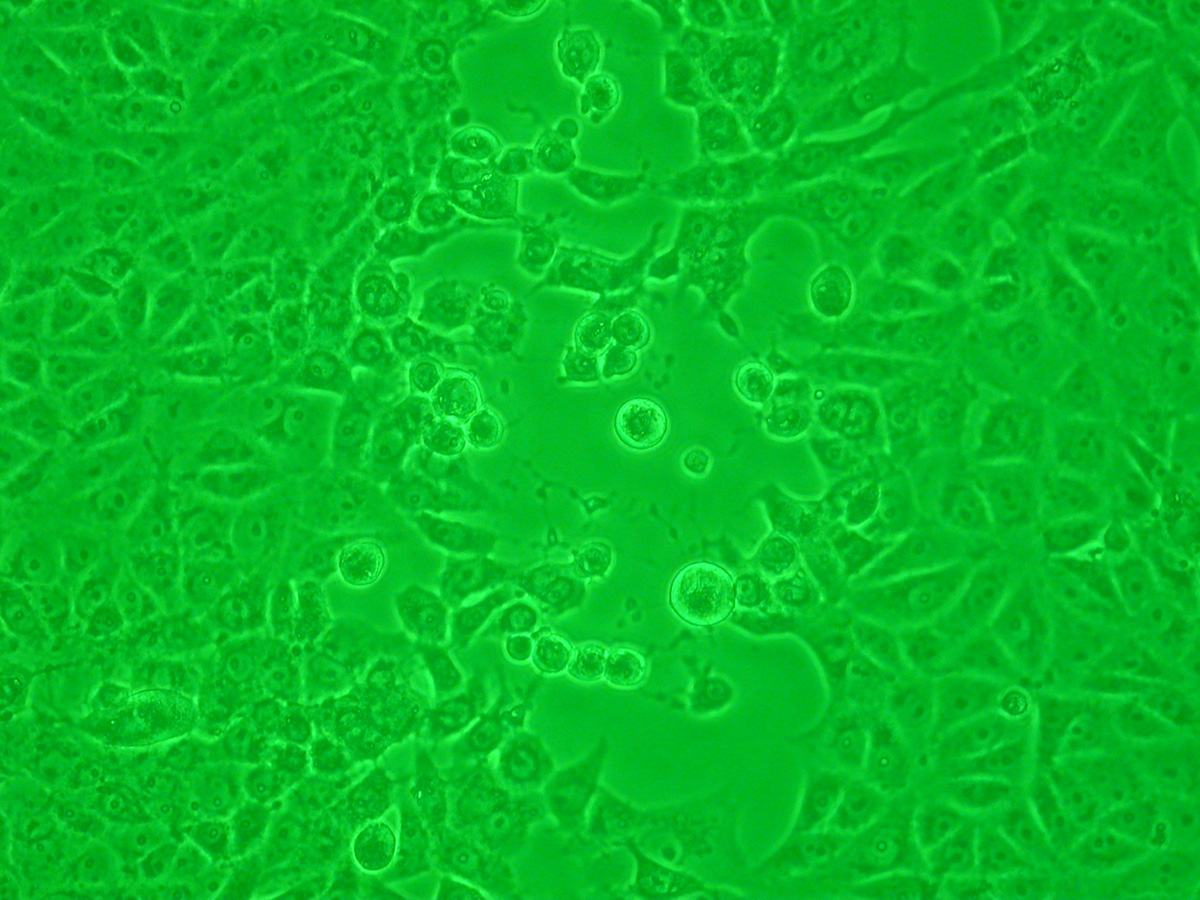

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can by indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can by indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These

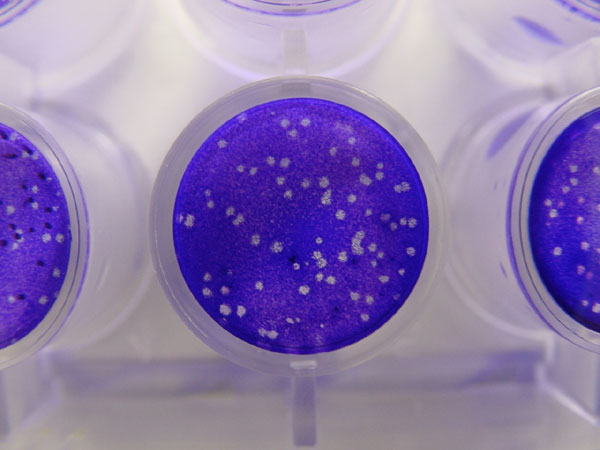

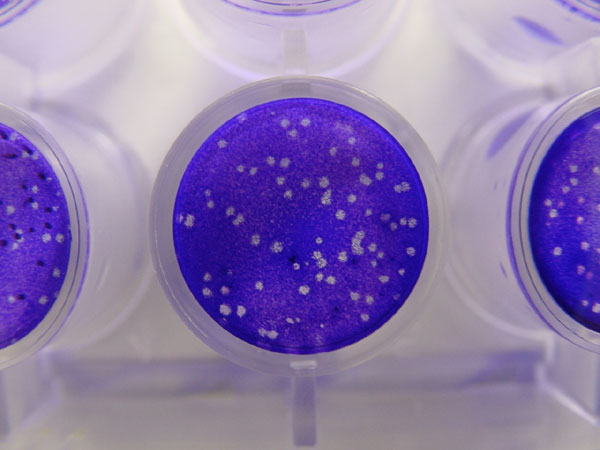

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume. For host cells, plants or cultures of bacterial or animal cells are used. Laboratory animals such as mice have also been used particularly in veterinary virology. These are assays are either quantitative where the results are on a continuous scale or quantal, where an event either occurs or it does not. Quantitative assays give

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume. For host cells, plants or cultures of bacterial or animal cells are used. Laboratory animals such as mice have also been used particularly in veterinary virology. These are assays are either quantitative where the results are on a continuous scale or quantal, where an event either occurs or it does not. Quantitative assays give  The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs

The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

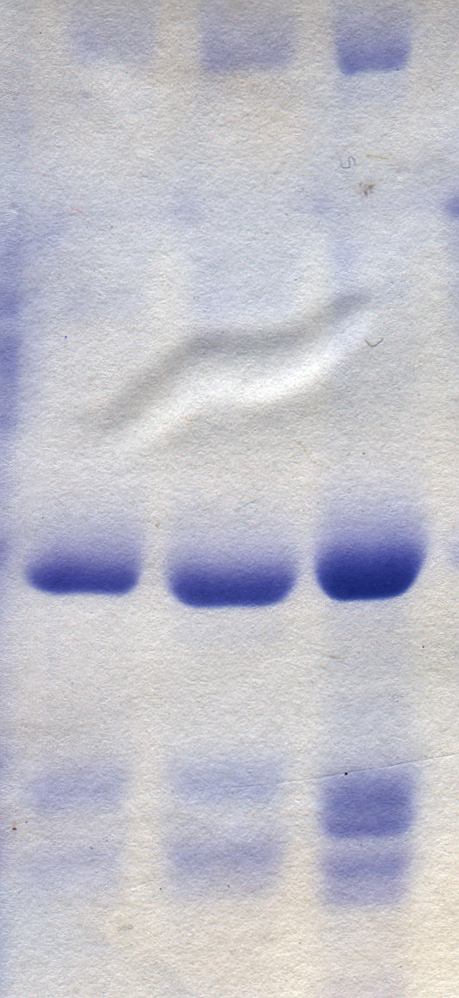

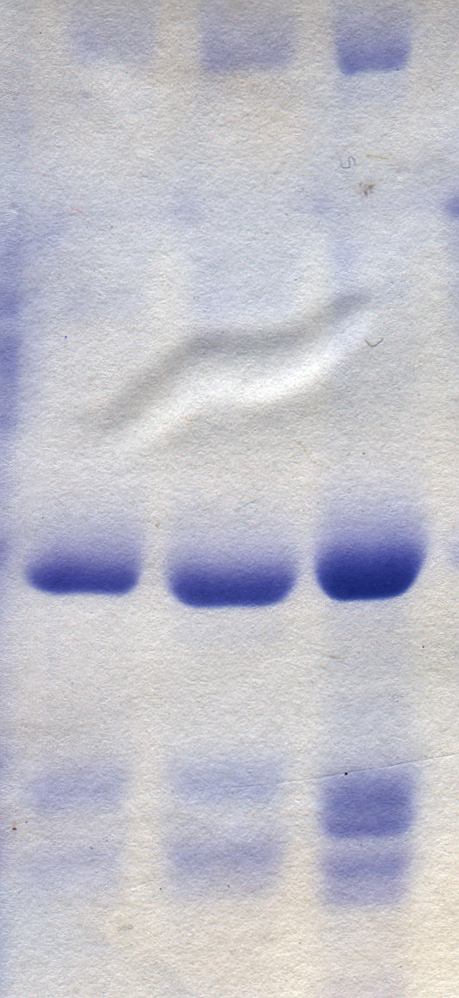

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist

International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

{{Authority control Viruses

Virology is the

Virology is the scientific study

Scientific study is a kind of study that involves scientific theory, scientific models, experiments and physical situations. It may refer to:

*Scientific method, a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, based on empirical or measurabl ...

of biological virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es. It is a subfield of microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

*Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Host ...

cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

for reproduction, their interaction with host organism physiology and immunity, the diseases they cause, the techniques to isolate and culture them, and their use in research and therapy.

The identification of the causative agent of tobacco mosaic disease

''Tobacco mosaic virus'' (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus ''Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteri ...

(TMV) as a novel pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

by Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Willem Beijerinck (, 16 March 1851 – 1 January 1931) was a Dutch microbiologist and botanist who was one of the founders of virology and environmental microbiology. He is credited with the discovery of viruses, which he called "''c ...

(1898) is now acknowledged as being the official beginning of the field of virology as a discipline distinct from bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

. He realized the source was neither a bacterial

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

nor a fungal

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from th ...

infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, but something completely different. Beijerinck used the word "virus" to describe the mysterious agent in his 'contagium vivum fluidum

''Contagium vivum fluidum'' (Latin: "contagious living fluid") was a phrase first used to describe a virus, and underlined its ability to slip through the finest-mesh filters then available, giving it almost liquid properties. Martinus Beijerinck ...

' ('contagious living fluid'). Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, co ...

proposed the full structure of the tobacco mosaic virus in 1955.

Virology began when there were no methods for propagating or visualizing viruses or specific laboratory tests for viral infections. The methods for separating viral nucleic acids (RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

and DNA) and protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, which are now the mainstay of virology, did not exist. Now there are many methods for observing the structure and functions of viruses and their component parts. Thousands of different viruses are now known about and virologists often specialize in either the viruses that infect plants, or bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and other microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s, or animals. Viruses that infect humans are now studied by medical virologists. Virology is a broad subject covering biology, health, animal welfare, agriculture and ecology.

History

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

was unable to find a causative agent for rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected by microscopes. In 1884, the French microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Ancient Greek, Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of Microorganism, microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, f ...

Charles Chamberland

Charles Chamberland (; 12 March 1851 – 2 May 1908) was a French microbiologist from Chilly-le-Vignoble in the department of Jura who worked with Louis Pasteur.

In 1884 he developed a type of filtration known today as the Chamberland filte ...

invented the Chamberland filter

A Chamberland filter, also known as a Pasteur–Chamberland filter, is a porcelain water filter invented by Charles Chamberland in 1884.

It was developed after Henry Doulton, Henry Doulton's ceramic water filter of 1827. It is similar to the Be ...

(or Pasteur-Chamberland filter) with pores small enough to remove all bacteria from a solution passed through it. In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitri Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus

''Tobacco mosaic virus'' (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus ''Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteri ...

: crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remained infectious even after filtration to remove bacteria. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849– ...

produced by bacteria, but he did not pursue the idea.Collier p. 3 At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium—this was part of the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade h ...

.Dimmock p. 4

In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck

Martinus Willem Beijerinck (, 16 March 1851 – 1 January 1931) was a Dutch microbiologist and botanist who was one of the founders of virology and environmental microbiology. He is credited with the discovery of viruses, which he called "''c ...

repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent. He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a ''contagium vivum fluidum

''Contagium vivum fluidum'' (Latin: "contagious living fluid") was a phrase first used to describe a virus, and underlined its ability to slip through the finest-mesh filters then available, giving it almost liquid properties. Martinus Beijerinck ...

'' (soluble living germ) and reintroduced the word ''virus''. Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley

Wendell Meredith Stanley (16 August 1904 – 15 June 1971) was an American biochemist, virologist and Nobel laureate.

Biography

Stanley was born in Ridgeville, Indiana, and earned a BSc in Chemistry at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. ...

, who proved they were particulate. In the same year, Friedrich Loeffler

Friedrich August Johannes Loeffler (; 24 June 18529 April 1915) was a German bacteriologist at the University of Greifswald.

Biography

He obtained his M.D. degree from the University of Berlin in 1874. He worked with Robert Koch from 1879 to 1884I ...

and Paul Frosch passed the first animal virus, aphthovirus

''Aphthovirus'' (from the Greek -, vesicles in the mouth) is a viral genus of the family ''Picornaviridae''. Aphthoviruses infect split-hooved animals, and include the causative agent of foot-and-mouth disease, ''Foot-and-mouth disease virus'' ...

(the agent of foot-and-mouth disease

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) or hoof-and-mouth disease (HMD) is an infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including domestic and wild bovids. The virus causes a high fever lasting two to six days, followe ...

), through a similar filter.

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort

Frederick William Twort FRS (22 October 1877 – 20 March 1950) was an England, English bacteriologist and was the original discoverer in 1915 of bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria). He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, London, w ...

discovered a group of viruses that infect bacteria, now called bacteriophages

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacterio ...

(or commonly 'phages'), and the French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle

Felix may refer to:

* Felix (name), people and fictional characters with the name

Places

* Arabia Felix is the ancient Latin name of Yemen

* Felix, Spain, a municipality of the province Almería, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, ...

described viruses that, when added to bacteria on an agar plate

An agar plate is a Petri dish that contains a growth medium solidified with agar, used to culture microorganisms. Sometimes selective compounds are added to influence growth, such as antibiotics.

Individual microorganisms placed on the plate wil ...

, would produce areas of dead bacteria. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension. Phages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

and cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

. The development of bacterial resistance to antibiotics has renewed interest in the therapeutic use of bacteriophages.

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity

In epidemiology, infectivity is the ability of a pathogen to establish an infection. More specifically, infectivity is a pathogen's capacity for horizontal transmission — that is, how frequently it spreads among hosts that are not in a parent� ...

, their ability to pass filters, and their requirement for living hosts. Viruses had been grown only in plants and animals. In 1906 Ross Granville Harrison

Ross Granville Harrison (January 13, 1870 – September 30, 1959) was an American biologist and anatomist credited for his pioneering work on animal tissue culture. His work also contributed to the understanding of embryonic development. Harrison ...

invented a method for growing tissue in lymph

Lymph (from Latin, , meaning "water") is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues to ...

, and in 1913 E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R.A. Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue. In 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s when poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species ''Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of an ...

was grown on a large scale for vaccine production.

Another breakthrough came in 1931 when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture

Ernest William Goodpasture (October 17, 1886 – September 20, 1960) was an American pathologist and physician. Goodpasture advanced the scientific understanding of the pathogenesis of infectious diseases, parasitism, and a variety of ricketts ...

and Alice Miles Woodruff

Alice Miles Woodruff (November 29, 1900 – November 24, 1985), born Alice Lincoln Miles, was an American virologist. She developed a method for growing fowlpox outside of a live chicken alongside Ernest William Goodpasture. Her research greatly ...

grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chicken eggs. In 1949, John Franklin Enders

John Franklin Enders (February 10, 1897 – September 8, 1985) was an American biomedical scientist and Nobel Laureate. Enders has been called "The Father of Modern Vaccines."

Life and education

Enders was born in West Hartford, Connecticut on Fe ...

, Thomas Weller

Thomas Christian Weller (born 4 November 1980) is a German former professional association football, footballer who plays as a left midfielder or left-back for FC Romanshorn.

Career

Weller joined FC St. Gallen on 24 October 2007.

He moved t ...

, and Frederick Robbins

Frederick Chapman Robbins (August 25, 1916 – August 4, 2003) was an American pediatrician and virologist. He was born in Auburn, Alabama, and grew up in Columbia, Missouri, attending David H. Hickman High School.

He received the Nobel Prize in P ...

grew poliovirus in cultured cells from aborted human embryonic tissue, the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. This work enabled Hilary Koprowski

Hilary Koprowski (5 December 191611 April 2013) was a Polish virologist and immunologist active in the United States who demonstrated the world's first effective live polio vaccine. He authored or co-authored over 875 scientific papers and co ...

, and then Jonas Salk

Jonas Edward Salk (; born Jonas Salk; October 28, 1914June 23, 1995) was an American virologist and medical researcher who developed one of the first successful polio vaccines. He was born in New York City and attended the City College of New Y ...

, to make an effective polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all chil ...

.

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska

Ernst August Friedrich Ruska (; 25 December 1906 – 27 May 1988) was a German physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986 for his work in electron optics, including the design of the first electron microscope.

Life and career

Erns ...

and Max Knoll

Max Knoll (17 July 1897 – 6 November 1969) was a German electrical engineer.

Knoll was born in Wiesbaden and studied in Munich and at the Technical University of Berlin, where he obtained his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', ...

. In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley

Wendell Meredith Stanley (16 August 1904 – 15 June 1971) was an American biochemist, virologist and Nobel laureate.

Biography

Stanley was born in Ridgeville, Indiana, and earned a BSc in Chemistry at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. He ...

examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein. A short time later, this virus was separated into protein and RNA parts.

The tobacco mosaic virus was the first to be crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

lised and its structure could, therefore, be elucidated in detail. The first X-ray diffraction

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

pictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. Based on her X-ray crystallographic pictures, Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, co ...

discovered the full structure of the virus in 1955. In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat

Heinz Ludwig Fraenkel-Conrat (July 29, 1910 – April 10, 1999) was a biochemist, famous for his research on viruses.

Early life

Fraenkel-Conrat was born in Breslau/Germany.

He was the son of Lili Conrat and Professor Ludwig Fraenkel, direc ...

and Robley Williams

Robley Cook Williams (October 13, 1908 – January 3, 1995) was an early biophysicist and virologist. He served as the first president of the Biophysical Society.

Career

Williams attended Cornell University on an athletic scholarship, completi ...

showed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its protein coat can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery, and most of the documented species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years. In 1957 equine arterivirus and the cause of Bovine virus diarrhoea (a pestivirus

''Pestivirus'' is a genus of viruses, in the family ''Flaviviridae''. Viruses in the genus ''Pestivirus'' infect mammals, including members of the family Bovidae (which includes cattle, sheep, and goats) and the family Suidae (which includes var ...

) were discovered. In 1963 the hepatitis B virus

''Hepatitis B virus'' (HBV) is a partially double-stranded DNA virus, a species of the genus ''Orthohepadnavirus'' and a member of the ''Hepadnaviridae'' family of viruses. This virus causes the disease hepatitis B.

Disease

Despite there bein ...

was discovered by Baruch Blumberg

Baruch Samuel Blumberg (July 28, 1925 April 5, 2011), known as Barry Blumberg, was an American physician, geneticist, and co-recipient of the 1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (with Daniel Carleton Gajdusek), for his work on the hepat ...

, and in 1965 Howard Temin

Howard Martin Temin (December 10, 1934 – February 9, 1994) was an American geneticist and virologist. He discovered reverse transcriptase in the 1970s at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, for which he shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Phy ...

described the first retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

. Reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

, the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

that retroviruses use to make DNA copies of their RNA, was first described in 1970 by Temin and David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is President Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technolo ...

independently. In 1983 Luc Montagnier

Luc Montagnier (; , ; 18 August 1932 – 8 February 2022) was a French virologist and joint recipient, with and , of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He worked as a res ...

's team at the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

in France, first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV. In 1989 Michael Houghton's team at Chiron Corporation

Chiron Corporation ( ) was an American multinational biotechnology firm founded in 1981, based in Emeryville, California, that was acquired by Novartis on April 20, 2006. It had offices and facilities in eighteen countries on five continents. C ...

discovered hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. During the initial infection people often have mild or no symptoms. Occasionally a fever, dark urine, a ...

.

Viral diseases

One main motivation for the study of viruses is because they cause many infectious diseases of plants and animals. The study of the manner in which viruses cause disease isviral pathogenesis

Viral pathogenesis is the study of the process and mechanisms by which viruses cause diseases in their target hosts, often at the cellular or molecular level. It is a specialized field of study in virology.

Pathogenesis is a qualitative descriptio ...

. The degree to which a virus causes disease is its virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

. These fields of study are called plant virology, animal virology

Veterinary virology is the study of viruses in non-human animals. It is an important branch of veterinary medicine.

Rhabdoviruses

Rhabdoviruses are a diverse family of single stranded, negative sense RNA viruses that infect a wide range of hos ...

and human or medical virology

Medical microbiology, the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various ...

.

Detecting viruses

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their antigens

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

or nucleic acids and infectivity assays.

Electron microscopy

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

s instead of light, which have a much shorter wavelength and can detect objects that cannot be seen using light microscopes. The typical magnification obtained using electron microscopes is up to 10,000,000 timesPayne S. Methods to Study Viruses. Viruses. 2017;37-52. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00004-0 whereas the highest magnification obtainable with light microscopes is around 1,500 times.

Virologists often use negative staining In microscopy, negative staining is an established method, often used in diagnostic microscopy, for contrasting a thin specimen with an optically opaque fluid. In this technique, the background is stained, leaving the actual specimen untouched, an ...

to help visualise viruses. In this procedure, the viruses are suspended in a solution of metal salts such as uranium acetate. The atoms of metal are opaque to electrons and the viruses are seen as suspended in a dark background of metal atoms. This technique has been in use since the 1950s. Many viruses were discovered using this technique and negative staining electron microscopy is still a valuable weapon in a virologist's arsenal.

Traditional electron microscopy has disadvantages in that viruses are damaged by drying in the high vacuum inside the electron microscope and the electron beam itself is destructive. In cryogenic electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a cryomicroscopy technique applied on samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An aqueous sample so ...

the structure of viruses is preserved by embedding them in an environment of vitreous water. This allows the determination of biomolecular structures at near-atomic resolution, and has attracted wide attention to the approach as an alternative to X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

or NMR spectroscopy

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, most commonly known as NMR spectroscopy or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), is a spectroscopic technique to observe local magnetic fields around atomic nuclei. The sample is placed in a magnetic fiel ...

for the determination of the structure of viruses.

Growth in cultures

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites and because they only reproduce inside the living cells of a host these cells are needed to grow them in the laboratory. For viruses that infect animals (usually called "animal viruses") cells grown in laboratorycell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. The term "tissue culture" was coined by American pathologist Montrose Thomas Burrows. This te ...

s are used. In the past, fertile hens' eggs were used and the viruses were grown on the membranes surrounding the embryo. This method is still used in the manufacture of some vaccines. For the viruses that infect bacteria, the bacteriophages

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacterio ...

, the bacteria growing in test tubes can be used directly. For plant viruses, the natural host plants can be used or, particularly when the infection is not obvious, so-called indicator plants, which show signs of infection more clearly.

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can by indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can by indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These cytopathic effect

Cytopathic effect or cytopathogenic effect (abbreviated CPE) refers to structural changes in host cells that are caused by viral invasion. The infecting virus causes lysis of the host cell or when the cell dies without lysis due to an inability to ...

s are often characteristic of the type of virus. For instance, herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), also known by their taxonomical names ''Human alphaherpesvirus 1'' and '' Human alphaherpesvirus 2'', are two members of the human ''Herpesviridae'' family, a set of viruses that produce viral inf ...

es produce a characteristic "ballooning" of the cells, typically human fibroblast

A fibroblast is a type of cell (biology), biological cell that synthesizes the extracellular matrix and collagen, produces the structural framework (Stroma (tissue), stroma) for animal Tissue (biology), tissues, and plays a critical role in wound ...

s. Some viruses, such as mumps virus

The mumps virus (MuV) is the virus that causes mumps. MuV contains a single-stranded, negative-sense genome made of ribonucleic acid (RNA). Its genome is about 15,000 nucleotides in length and contains seven genes that encode nine proteins. The g ...

cause red blood cells from chickens to firmly attach to the infected cells. This is called "haemadsorption" or "hemadsorption". Some viruses produce localised "lesions" in cell layers called plaques

Plaque may refer to:

Commemorations or awards

* Commemorative plaque, a plate or tablet fixed to a wall to mark an event, person, etc.

* Memorial Plaque (medallion), issued to next-of-kin of dead British military personnel after World War I

* Pla ...

, which are useful in quantitation assays and in identifying the species of virus by plaque reduction assays.

Viruses growing in cell cultures are used to measure their susceptibility to validated and novel antiviral drug

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Unlike most antibiotics, antiviral drugs do n ...

s.

Serology

Viruses areantigens

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

that induce the production of antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

and these can antibodies can be used in laboratories to study viruses. Related viruses often react with each other's antibodies and some viruses can be named based on the antibodies they react with. The use of the antibodies which were once exclusively derived from the serum (blood fluid) of animals is call serology

Serology is the scientific study of Serum (blood), serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the medical diagnosis, diagnostic identification of Antibody, antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in r ...

. Once and antibody–reaction as taken place in a test, other methods are needed to confirm this. Older methods included complement fixation test

The complement fixation test is an immunological medical test that can be used to detect the presence of either specific antibody or specific antigen in a patient's serum, based on whether complement fixation occurs. It was widely used to diagnos ...

s, hemagglutination inhibition

The hemagglutination assay or haemagglutination assay (HA) and the hemagglutination inhibition assay (HI or HAI) were developed in 1941–42 by American virologist George Hirst as methods for quantifying the relative concentration of viruses, bact ...

and virus neutralisation. Newer methods us enzyme- immunoassays (EIA).

In the years before PCR was invented immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on microbiological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specif ...

was used to quickly confirm viral infections. It is an infectivity assay that is virus species specific because antibodies are used. The antibodies are tagged with a dye that is luminescencent and when using an optical microscope with a modified light source, infected cells glow in the dark.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other nucleic acid detection methods

PCR is a mainstay method for detecting viruses in all species including plants and animals. It works by detecting traces of virus specific RNA or DNA. It is very sensitive and specific, but can be easily compromised by contamination. Most of the tests used in veterinary virology and medical virology are based on PCR or similar methods such astranscription mediated amplification

Transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) is an isothermal (does not change the nucleic acid temperature), single-tube nucleic acid Gene_duplication#As_amplification, amplification system utilizing two enzymes, RNA polymerase and reverse transcri ...

. When a novel virus emerges, such as the covid coronavirus, a specific test can be devised quickly so long as the viral genome has been sequenced and unique regions of the viral DNA or RNA identified. The invention of microfluidic

Microfluidics refers to the behavior, precise control, and manipulation of fluids that are geometrically constrained to a small scale (typically sub-millimeter) at which surface forces dominate volumetric forces. It is a multidisciplinary field tha ...

tests as allowed for most of these tests to be automated, Despite its specificity and sensitivity, PCR has a disadvantage in that it does not differentiate infectious and non-infectious viruses and "tests of cure" have to be delayed for up to 21 days to allow for residual viral nucleic acid to clear from the site of the infection.

Diagnostic tests

In laboratories many of the diagnostic test for detecting viruses are nucleic acid amplification methods such as PCR. Some tests detect the viruses or their components as these include electron microscopy and enzyme-immunoassays. The so-called "home" or "self"-testing gadgets are usually lateral flow tests, which detect the virus using a taggedmonoclonal antibody

A monoclonal antibody (mAb, more rarely called moAb) is an antibody produced from a cell Lineage made by cloning a unique white blood cell. All subsequent antibodies derived this way trace back to a unique parent cell.

Monoclonal antibodies ca ...

. These are also used in agriculture, food and environmental sciences.

Quantitation and viral loads

Counting viruses (quantitation) has always had an important role in virology and has become central to the control of some infections of humans where theviral load

Viral load, also known as viral burden, is a numerical expression of the quantity of virus in a given volume of fluid, including biological and environmental specimens. It is not to be confused with viral titre or viral titer, which depends on the ...

is measured. There are two basic methods: those that count the fully infective virus particles, which are called infectivity assays, and those that count all the particles including the defective ones.

Infectivity assays

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume. For host cells, plants or cultures of bacterial or animal cells are used. Laboratory animals such as mice have also been used particularly in veterinary virology. These are assays are either quantitative where the results are on a continuous scale or quantal, where an event either occurs or it does not. Quantitative assays give

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume. For host cells, plants or cultures of bacterial or animal cells are used. Laboratory animals such as mice have also been used particularly in veterinary virology. These are assays are either quantitative where the results are on a continuous scale or quantal, where an event either occurs or it does not. Quantitative assays give absolute value

In mathematics, the absolute value or modulus of a real number x, is the non-negative value without regard to its sign. Namely, , x, =x if is a positive number, and , x, =-x if x is negative (in which case negating x makes -x positive), an ...

s and quantal assays give a statistical probability such as the volume of the test sample needed to ensure 50% of the hosts cells, plants or animals are infected. This is called the median infectious dose or ID 50. Infective bacteriophages can be counted by seeding them onto "lawns" of bacteria in culture dishes. When at low concentrations, the viruses form holes in the lawn that can be counted. The number of viruses is then expressed as plaque forming units

A plaque-forming unit (PFU) is a measure used in virology to describe the number of virus particles capable of forming plaques per unit volume. It is a proxy measurement rather than a measurement of the absolute quantity of particles: viral part ...

. For the bacteriophages that reproduce in bacteria that cannot be grown in cultures, viral load assays are used.

The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs

The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs immunostaining

In biochemistry, immunostaining is any use of an antibody-based method to detect a specific protein in a sample. The term "immunostaining" was originally used to refer to the immunohistochemical staining of tissue sections, as first described by A ...

techniques using fluorescently labeled antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

specific for a viral antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

to detect infected host cells and infectious virus particles before an actual plaque is formed. The FFA is particularly useful for quantifying classes of viruses that do not lyse the cell membranes, as these viruses would not be amenable to the plaque assay. Like the plaque assay, host cell monolayers are infected with various dilutions of the virus sample and allowed to incubate for a relatively brief incubation period (e.g., 24–72 hours) under a semisolid overlay medium that restricts the spread of infectious virus, creating localized clusters (foci) of infected cells. Plates are subsequently probed with fluorescently labeled antibodies against a viral antigen, and fluorescence microscopy is used to count and quantify the number of foci. The FFA method typically yields results in less time than plaque or fifty-percent-tissue-culture-infective-dose (TCID50) assays, but it can be more expensive in terms of required reagents and equipment. Assay completion time is also dependent on the size of area that the user is counting. A larger area will require more time but can provide a more accurate representation of the sample. Results of the FFA are expressed as focus forming units per milliliter, or FFU/

Viral load assays

When an assay for measuring the infective virus particle is done (Plaque assay, Focus assay), viral titre often refers to the concentration of infectious viral particles, which is different from the total viral particles. Viral load assays usually count the number of viral genomes present rather than the number of particles and use methods similar to PCR. Viral load tests are an important in the control of infections by HIV. This versatile method can be used for plant viruses.Molecular biology

Molecular virology is the study of viruses at the level of nucleic acids and proteins. The methods invented bymolecular biologists

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

have all proven useful in virology. Their small sizes and relatively simple structures make viruses an ideal candidate for study by these techniques.

Purifying viruses and their components

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

Centrifugation

Centrifuge

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby separating fluids of different densities (e.g. cream from milk) or ...

s are often used to purify viruses. Low speed centrifuges, ie. those with a top speed of 10,000 revolutions per minute

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

(rpm) are not powerful enough to concentrate viruses, but ultracentrifuge

An ultracentrifuge is a centrifuge optimized for spinning a rotor at very high speeds, capable of generating acceleration as high as (approx. ). There are two kinds of ultracentrifuges, the preparative and the analytical ultracentrifuge. Both cla ...

s with a top speed of around 100,000 rpm, are and this difference is used in a method called differential centrifugation

In biochemistry and cell biology, differential centrifugation (also known as differential velocity centrifugation) is a common procedure used to separate organelles and other sub-cellular particles based on their sedimentation rate. Although o ...

. In this method the larger and heavier contaminants are removed from a virus mixture by low speed centrifugation. The viruses, which are small and light and are left in suspension, are then concentrated by high speed centrifugation.

Following differential centrifugation, virus suspensions often remain contaminated with debris that has the same sedimentation coefficient

The sedimentation coefficient () of a particle characterizes its sedimentation during centrifugation. It is defined as the ratio of a particle's sedimentation velocity to the applied acceleration causing the sedimentation.

: s = \frac

The sedime ...

and are not removed by the procedure. In these cases a modification of centrifugation, called buoyant density centrifugation

Buoyant density centrifugation (also isopycnic centrifugation or equilibrium density-gradient centrifugation) uses the concept of buoyancy to separate molecules in solution by their differences in density.

Implementation

Historically a caesium c ...

, is used. In this method the viruses recovered from differential centrifugation are centrifuged again at very high speed for several hours in dense solutions of sugars or salts that form a density gradient, from low to high, in the tube during the centrifugation. In some cases, preformed gradients are used where solutions of steadily decreasing density are carefully overlaid on each other. Like an object in the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, despite the centrifugal force the virus particles cannot sink into solutions that are more dense than they are and they form discrete layers of, often visible, concentrated viruses in the tube. Caesium chloride is often used for these solutions as it is relatively inert but easily self-forms a gradient when centrifuged at high speed in an ultracentrifuge. Buoyant density centrifugation can also be used to purify the components of viruses such as their nucleic acids or proteins.

Electrophoresis

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called electrophoresis

Electrophoresis, from Ancient Greek ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron, "amber") and φόρησις (phórēsis, "the act of bearing"), is the motion of dispersed particles relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric fie ...

. Viruses and all their components can be separated and purified using this method. This is usually done in a supporting medium such as agarose

Agarose is a heteropolysaccharide, generally extracted from certain red seaweed. It is a linear polymer made up of the repeating unit of agarobiose, which is a disaccharide made up of D-galactose and 3,6-anhydro-L-galactopyranose. Agarose is o ...

and polyacrylamide gel

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a technique widely used in biochemistry, forensic chemistry, genetics, molecular biology and biotechnology to separate biological macromolecules, usually proteins or nucleic acids, according to their ...

s. The separated molecules are revealed using stains such as coomasie blue, for proteins, or ethidium bromide

Ethidium bromide (or homidium bromide, chloride salt homidium chloride) is an intercalating agent commonly used as a fluorescent tag (nucleic acid stain) in molecular biology laboratories for techniques such as agarose gel electrophoresis. It i ...

for nucleic acids. In some instances the viral components are rendered radioactive before electrophoresis an are revealed using photographic film in a process known as autoradiography

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions (e.g., beta particles or gamma rays) from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also available ...

.

Sequencing of viral genomes

As most viruses are too small to be seen by a light microscope, sequencing is one of the main tools in virology to identify and study the virus. Traditional Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are used to sequence viruses in basic and clinical research, as well as for the diagnosis of emerging viral infections, molecular epidemiology of viral pathogens, and drug-resistance testing. There are more than 2.3 million unique viral sequences in GenBank. NGS has surpassed traditional Sanger as the most popular approach for generating viral genomes. Viral genome sequencing as become a central method in viralepidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evidenc ...

and viral classification

Virus classification is the process of naming viruses and placing them into a taxonomic system similar to the classification systems used for cellular organisms.

Viruses are classified by phenotypic characteristics, such as morphology, nucleic ...

.

Phylogenetic analysis

Data from the sequencing of viral genomes can be used to determine evolutionary relationships and this is calledphylogenetic analysis

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

. Software, such as PHYLIP

PHYLogeny Inference Package (PHYLIP) is a free computational phylogenetics package of programs for inferring evolutionary trees (phylogenies). It consists of 65 portable programs, i.e., the source code is written in the programming language C. As ...

, is used to draw phylogenetic trees

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

. This analysis is also used in studying the spread of viral infections in communities, (epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evidenc ...

).

Cloning

When purified viruses or viral components are needed for diagnostic tests or vaccines, cloning can be used instead of growing the viruses. At the start of theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

the availability of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), the respiratory illness responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had a No ...

RNA sequence enabled tests to be manufactured quickly. There are several proven methods for cloning viruses and their components. Small pieces of DNA called cloning vector

A cloning vector is a small piece of DNA that can be stably maintained in an organism, and into which a foreign DNA fragment can be inserted for cloning purposes. The cloning vector may be DNA taken from a virus, the cell of a higher organism, or ...

s are often used and the most common ones are laboratory modified plasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

(small circular molecules of DNA produced by bacteria). The viral nucleic acid, or a part of it, is inserted in the plasmid, which is the copied many times over by bacteria. This recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be foun ...

can then be used to produce viral components without the need for native viruses.

Phage virology

The viruses that reproduce in bacteria, archaea and fungi are informally called "phages", and the ones that infect bacteria –bacteriophages

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacterio ...

– in particular are useful in virology and biology in general. Bacteriophages were some of the first viruses to be discovered, early in the twentieth century, and because they are relatively easy to grow quickly in laboratories, much of our understanding of viruses originated by studying them. Bacteriophages, long known for their positive effects in the environment, are used in phage display

Phage display is a laboratory technique for the study of protein–protein, protein–peptide, and protein– DNA interactions that uses bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) to connect proteins with the genetic information that encodes ...

techniques for screening proteins DNA sequences. They are a powerful tool in molecular biology.

Genetics

All viruses havegene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s which are studied using genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

. All the techniques used in molecular biology, such as cloning, creating mutations RNA silencing

RNA silencing or RNA interference refers to a family of gene silencing effects by which gene expression is negatively regulated by non-coding RNAs such as microRNAs. RNA silencing may also be defined as sequence-specific regulation of gene express ...

are used in viral genetics.

Reassortment

Reassortment

Reassortment is the mixing of the genetic material of a species into new combinations in different individuals. Several different processes contribute to reassortment, including assortment of chromosomes, and chromosomal crossover. It is particula ...

is the switching of genes from different parents and it is particularly useful when studying the genetics of viruses that have segmented genomes (fragmented into two or more nucleic acid molecules) such as influenza virus

''Orthomyxoviridae'' (from Greek ὀρθός, ''orthós'' 'straight' + μύξα, ''mýxa'' 'mucus') is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: ''Alphainfluenzavirus'', ''Betainfluenzavirus'', '' Gammainfluenzavirus'', ...

es and rotavirus

''Rotavirus'' is a genus of double-stranded RNA viruses in the family ''Reoviridae''. Rotaviruses are the most common cause of diarrhoeal disease among infants and young children. Nearly every child in the world is infected with a rotavirus a ...

es. The genes that encode properties such as serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their surface antigens, allowing the epi ...

can be identified in this way.

Recombination

Often confused with reassortment, recombination is also the mixing of genes but the mechanism differs in that ''stretches'' of DNA or RNA molecules, as opposed to the full molecules, are joined together during the RNA or DNA replication cycle. Recombination is not as common as reassortment in nature but it is a powerful tool in laboratories for studying the structure and functions of viral genes.Reverse genetics

Reverse genetics

Reverse genetics is a method in molecular genetics that is used to help understand the function(s) of a gene by analysing the phenotypic effects caused by genetically engineering specific nucleic acid sequences within the gene. The process proce ...

is a powerful research method in virology. In this procedure complimentary DNA (cDNA) copies of virus genomes called "infectious clones" are used to produce genetically modified viruses that can be then tested for changes in say, virulence or transmissibility.

Virus classification

A major branch of virology isvirus classification

Virus classification is the process of naming viruses and placing them into a taxonomic system similar to the classification systems used for cellular organisms.

Viruses are classified by phenotypic characteristics, such as morphology, nucleic ac ...

. It is artificial in that it is not based on evolutionary phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek language, Greek wikt:φυλή, φυλή/wikt:φῦλον, φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary his ...

but it is based shared or distinguishing properties of viruses. It seeks to describe the diversity of viruses by naming and grouping them on the basis of similarities. In 1962, André Lwoff

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French-speaking countries. It is a variation o ...

, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean hierarchical system. This system based classification on phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

, class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

, order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

, family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

, genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

, and species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

. Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes. In 1966, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) authorizes and organizes the taxonomic classification of and the nomenclatures for viruses. The ICTV has developed a universal taxonomic scheme for viruses, and thus has the means to app ...

(ICTV) was formed. The system proposed by Lwoff, Horne and Tournier was initially not accepted by the ICTV because the small genome size of viruses and their high rate of mutation made it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond order. As such, the Baltimore classification

Baltimore classification is a system used to classify viruses based on their manner of messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis. By organizing viruses based on their manner of mRNA production, it is possible to study viruses that behave similarly as a di ...

system has come to be used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy. Starting in 2018, the ICTV began to acknowledge deeper evolutionary relationships between viruses that have been discovered over time and adopted a 15-rank classification system ranging from realm to species. Additionally, some species within the same genus are grouped into a ''genogroup''.

ICTV classification

The ICTV developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. Only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied. As of 2021, 6 realms, 10 kingdoms, 17 phyla, 2 subphyla, 39 classes, 65 orders, 8 suborders, 233 families, 168 subfamilies, 2,606 genera, 84 subgenera, and 10,434 species of viruses have been defined by the ICTV. The general taxonomic structure of taxon ranges and the suffixes used in taxonomic names are shown hereafter. As of 2021, the ranks of subrealm, subkingdom, and subclass are unused, whereas all other ranks are in use. :Realm

A realm is a community or territory over which a sovereign rules. The term is commonly used to describe a monarchical or dynastic state. A realm may also be a subdivision within an empire, if it has its own monarch, e.g. the German Empire.

Etym ...

(''-viria'')

::Subrealm (''-vira'')

:::Kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

(''-virae'')

::::Subkingdom (''-virites'')

:::::Phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

(''-viricota'')

::::::Subphylum (''-viricotina'')

:::::::Class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

(''-viricetes'')

::::::::Subclass (''-viricetidae'')

:::::::::Order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

(''-virales'')

::::::::::Suborder (''-virineae'')

:::::::::::Family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

(''-viridae'')

::::::::::::Subfamily (''-virinae'')

:::::::::::::Genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

(''-virus'')

::::::::::::::Subgenus (''-virus'')

:::::::::::::::Species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

Baltimore classification

David Baltimore

David Baltimore (born March 7, 1938) is an American biologist, university administrator, and 1975 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine. He is President Emeritus and Distinguished Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technolo ...

devised the Baltimore classification

Baltimore classification is a system used to classify viruses based on their manner of messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis. By organizing viruses based on their manner of mRNA production, it is possible to study viruses that behave similarly as a di ...

system.

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

(RT). In addition, ssRNA viruses may be either sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the cen ...

(+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

References

Bibliography

* * *External links

* *ICTVInternational Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

{{Authority control Viruses