Douglas Graham (British Army Officer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Following Alamein the brigade had a rest for a few weeks, absorbing replacements after suffering heavy losses, with the division as a whole having sustained some 2,800 casualties, and then, with the rest of the Eighth Army pursuing the retreating Axis forces, seeing light action at

Following Alamein the brigade had a rest for a few weeks, absorbing replacements after suffering heavy losses, with the division as a whole having sustained some 2,800 casualties, and then, with the rest of the Eighth Army pursuing the retreating Axis forces, seeing light action at  In early May 1943 Graham was selected by Montgomery (who, along with Wimberley, thought very highly of the former) to be the new GOC of the

In early May 1943 Graham was selected by Montgomery (who, along with Wimberley, thought very highly of the former) to be the new GOC of the

After being evacuated to hospital in the United Kingdom, by January 1944 Graham, after being

After being evacuated to hospital in the United Kingdom, by January 1944 Graham, after being

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Douglas Alexander Henry Graham, (26 March 1893 – 28 September 1971) was a senior British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer who fought with distinction in both world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

s. He is most notable during the Second World War for commanding the 153rd Brigade of the 51st (Highland) Division

The 51st (Highland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War from 1915 to 1918. The division was raised in 1908, upon the creation of the Territorial Force, as ...

in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

from 1942 to 1943, later being the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 56th (London) Infantry Division

The 56th (London) Infantry Division was a Territorial Army infantry division of the British Army, which served under several different titles and designations. The division served in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War. ...

during the Salerno landings

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, b ...

in Italy in September 1943 and the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division during the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

in France in June 1944.

Early life and First World War

Douglas Graham was born inAngus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* An ...

, Brechin, Scotland

Brechin (; gd, Breichin) is a city and former Royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which continues today ...

, the youngest of three children, on 26 March 1893. He was the son of Mungo MacDougal Graham and Margaret Lyall Murray, Graham, and after attending The Glasgow Academy

The Glasgow Academy is a coeducational independent day school for pupils aged 3–18 in Glasgow, Scotland. In 2016, it had the third-best Higher level exam results in Scotland. Founded in 1845, it is the oldest continuously fully independent s ...

and the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

into the 3rd Lowland Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

The Royal Field Artillery (RFA) of the British Army provided close artillery support for the infantry. It came into being when created as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery on 1 July 1899, serving alongside the other two arms of t ...

, Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry i ...

(TF), on 26 September 1911, but he resigned his commission on 25 September 1912. After attending the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infantry a ...

, he was granted a commission in the Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregulars, irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenary, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the ...

, again with the rank of second lieutenant, on 17 September 1913, in the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) was a rifle regiment of the British Army, the only regiment of rifles amongst the Scottish regiments of infantry. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 26th Cameronian Reg ...

, and was posted to the 1st Battalion.

The outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914 saw Graham serving as a platoon commander

{{unreferenced, date=February 2013

A platoon leader (NATO) or platoon commander (more common in Commonwealth militaries and the US Marine Corps) is the officer in charge of a platoon. This person is usually a junior officer – a second or firs ...

in 'D' Company of the 1st Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Philip Robertson, which soon became part of the 19th Brigade, when it was sent to the Western Front as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Thus Graham's battalion were amongst the first British troops to arrive in France. After participating in the retreat from Mons

The Great Retreat (), also known as the retreat from Mons, was the long withdrawal to the River Marne in August and September 1914 by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army. The Franco-British forces on the Western Fr ...

, on 22 October 1914, during the early stages of the First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres (french: Première Bataille des Flandres; german: Erste Flandernschlacht – was a battle of the First World War, fought on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front around Ypres, in West Flanders, Belgium. Th ...

, Graham was involved in an action that would lead to Rifleman

A rifleman is an infantry soldier armed with a rifling, rifled long gun. Although the rifleman role had its origin with 16th century hand cannoneers and 17th century musketeers, the term originated in the 18th century with the introduction o ...

Henry May Henry May may refer to:

*Henry May (American politician) (1816–1866), U.S. Representative from Maryland

* Henry May (New Zealand politician) (1912–1995), New Zealand politician

* Henry May (VC) (1885–1941), Scottish recipient of the Victoria C ...

, in Graham's platoon, the award of the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

(VC). Whilst in the La Boutillerie area of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Lieutenant Graham was wounded in the leg. Rifleman May, ignoring orders from Graham to leave him, dragged him, under heavy fire, 300 yards to safety. After May arranged for a rescue party for his platoon commander, and after recovering from his wounds, Graham, promoted on 3 November 1914 to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

, was promoted again to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

on 18 June 1916, returned to France and was appointed as a brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

with the 182nd Brigade, part of the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division

The 61st (2nd South Midland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army raised in 1915 during the Great War as a second-line reserve for the first-line battalions of the 48th (South Midland) Division. The division was sent to the W ...

, a Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry i ...

(TF) formation, on 30 April 1917, remaining with the brigade during all of its major battles of the war until 7 June 1919. He was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

(MC) in the 1918 New Year Honours

The 1918 New Year Honours were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by citizens of the British Empire. The appointments were published in ''The London Gazette'' and ''The Times'' in Ja ...

. He finished the war having also been mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

and awarded the French Croix de guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

.

Between the wars

The war came to an end on 11 November 1918 where, just under two weeks before, Graham's first son, Mungo Alan Douglas, was born on 29 October. Graham relinquished his appointment as brigade major on 8 June 1919, and returned to regimental duty on 11 January 1920. From 30 October 1921 he was seconded to theIndian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

as an assistant military secretary. He returned to the United Kingdom and attended the Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, which i ...

from 1924 to 1925 where, among his many fellow students there were Noel Irwin

Lieutenant General Noel Mackintosh Stuart Irwin & Two Bars, MC (24 December 1892 – 21 December 1972) was a senior British Army officer, who played a prominent role in the British Army after the Dunkirk evacuation, and in the Burma campaign ...

, Daril Watson

General Sir Daril Gerard Watson (17 October 1888 − 1 July 1967) was a senior British Army officer who saw service during both World War I and World War II.

Early life and military career

Born on 17 October 1888, Daril Watson was educated at ...

, Ivor Thomas, Clifford Malden, Cyril Durnford, Michael Creagh, Thomas Riddell-Webster, James Harter, Sydney Rigby Wason

Lieutenant General Sydney Rigby Wason , and Bar (27 September 1887 – 17 March 1969) was a senior British Army officer in the Second World War. His commands included a corps during the Battle of France and the anti-aircraft defences of Souther ...

, Langley Browning, Frederick Hyland, Otto Lund, Rufus Laurie, Gerald Fitzgerald, Arthur Barstow, John Reeve, Vyvyan Pope

Lieutenant-General Vyvyan Vavasour Pope CBE DSO MC & Bar (30 September 1891 – 5 October 1941) was a senior British Army officer who was prominent in developing ideas about the use of armour in battle in the interwar years, and who briefly ...

, Robert Studdert, Noel Napier-Clavering, Reade Godwin-Austen

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen, (17 April 1889 – 20 March 1963) was a British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who served during the First World War, First and the Second World Wars.

Early life and milit ...

, Gerald Brunskill

Gerald Fitzgibbon Brunskill (1866–1918) was an Irish Unionist Party politician who served briefly as Member of Parliament (MP) for Mid Tyrone. He was elected in the general election of January 1910, but lost the seat 11 months later in the De ...

, Archibald Nye, George Lammie, Noel Beresford-Peirse, Gerald Gartlan

Major-General Gerald Ion Gartlan (24 June 1889 – 15 July 1975) was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War and the Second World War.

Military career

Born in County Down in what is now Northern Ireland, in June 1889, G ...

, Geoffrey Raikes

Major General Sir Geoffrey Taunton Raikes, (7 April 1884 – 27 March 1975) was a British Army general who achieved high office in the 1930s.

Military career

Educated at Radley College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, Raikes was comm ...

, Humfrey Gale

Lieutenant General Sir Humfrey Myddelton Gale, (4 October 1890 – 8 April 1971) was an officer in the British Army who served in the First and Second World War, during which he was Chief Administrative Officer at Allied Forces Headquarters ...

, Guy Robinson

Vice Admiral Guy Antony Robinson, (born 9 April 1967) is a senior Royal Navy officer. Since September 2021, he has served as Chief of Staff of NATO Allied Command Transformation.

Naval career

Robinson joined the Royal Navy in 1986. He has serv ...

and Lionel Finch, along with John Northcott

Lieutenant General Sir John Northcott (24 March 1890 – 4 August 1966) was an Australian Army general who served as Chief of the General Staff during the Second World War, and commanded the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in the Occupa ...

of the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

and Ernest Sansom and Maurice Pope of the Canadian Army

The Canadian Army (french: Armée canadienne) is the command responsible for the operational readiness of the conventional ground forces of the Canadian Armed Forces. It maintains regular forces units at bases across Canada, and is also respo ...

. All of these men would, like Graham, become general officer

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

s in the future. He was then appointed a staff officer

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

with the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division

The 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army that was originally formed as the Lowland Division, in 1908 as part of the Territorial Force. It later became the 52nd (Lowland) Division in 1915. The 52nd (Lowland ...

, a Territorial Army (TA) formation, from 19 February 1928.

He was promoted to major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

on 16 December 1930, and from 31 December 1930 to 18 February 1932 he was Deputy Assistant Adjutant & Quarter-Master General (DAA&QMG), Lowland Area, Scottish Command. From 1 May 1932 to 30 April 1935 he was Officer Commanding

The officer commanding (OC), also known as the officer in command or officer in charge (OiC), is the commander of a sub-unit or minor unit (smaller than battalion size), principally used in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. In other countries, ...

(OC) the Cameronians regimental depot

The regimental depot of a regiment is its home base for recruiting and training. It is also where soldiers and officers awaiting discharge or postings are based and where injured soldiers return to full fitness after discharge from hospital b ...

at Hamilton, South Lanarkshire

Hamilton ( sco, Hamiltoun; gd, Baile Hamaltan ) is a large town in South Lanarkshire, Scotland. It serves as the main administrative centre of the South Lanarkshire council area. It sits south-east of Glasgow, south-west of Edinburgh and nort ...

. In June 1937 he had been promoted lieutenant colonel, and, shortly after the birth of his second son, John Murray Graham, on 7 June, was given command of the 2nd Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). The battalion was then stationed in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

on internal security duties during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

and returned to England in 1938, where it became part of Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

Henry Willcox's 13th Infantry Brigade, part of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Harold Franklyn

General Sir Harold Edmund Franklyn, (28 November 1885 − 31 March 1963) was a British Army officer who fought in both the First and the Second World Wars. He is most notable for his command of the 5th Infantry Division during the Battle of F ...

's 5th Infantry Division at Catterick, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

.

Second World War

Shortly after the outbreak of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939, Graham led his battalion overseas to France, arriving there in mid-September as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).Mead, p. 184 Unlike in the First World War, there was no immediate action and the first few months of the "Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germ ...

" (as this period of time was to become known) were, for the BEF, spent building defensive positions, such as trenches and pillboxes, in expectation of a repeat of the trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. Trench warfare became a ...

of 1914–1918. However, the battalion, along with the rest of the brigade (which was sent to France as an independent formation as the 5th Division was not fully formed by the outbreak of war), were mainly spared these duties, although they were assigned the role of guard duties in the BEF's rear areas, with almost no time devoted to training. In late December the brigade, now commanded by Brigadier Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in north west Europe. A highly professional an ...

(who Graham was to serve with later in the war), was returned to the 5th Division when the division HQ arrived in France and, during the next few months, was involved in numerous training exercises

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic s ...

.

In early April 1940, however, Graham returned to Scotland and was given command of the 27th Infantry Brigade, part of the 9th (Highland) Infantry Division

The 9th (Highland) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army, formed just prior to the start of the Second World War. In March 1939, after the re-emergence of Germany as a significant military power and its occupation of C ...

, a second-line TA formation, with the acting rank

An acting rank is a designation that allows a soldier to assume a military rank—usually higher and usually temporary. They may assume that rank either with or without the pay and allowances appropriate to that grade, depending on the nature of t ...

of brigadier, and the substantive rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. In August 1940 Graham's brigade changed its designation to the 153rd Infantry Brigade when the 9th Division was reformed as the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division

The 51st (Highland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War from 1915 to 1918. The division was raised in 1908, upon the creation of the Territorial Force, as ...

after the original 51st Division was lost in June 1940 during the latter stages of the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

. The new division's first General Officer Commanding (GOC) was Major General Alan Cunningham

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War ...

, who was replaced in October by Major General Neil Ritchie

General Sir Neil Methuen Ritchie, (29 July 1897 – 11 December 1983) was a British Army officer who saw service during both the world wars. He is most notable during the Second World War for commanding the British Eighth Army in the North Af ...

, the latter being succeeded in June 1941 by Major General Douglas Wimberley

Major-General Douglas Neil Wimberley, (15 August 1896 – 26 August 1983) was a British Army officer who, during the Second World War, commanded the 51st (Highland) Division for two years, from 1941 to 1943, notably at the Second Battle of El A ...

, who, being a Cameron Highlander, was determined to keep the division commanded only by Highlanders. Graham, being an officer of a Lowland

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of ...

regiment, was the one exception, with Wimberley believing him to be highly competent and Graham retained his position. The next year was spent training, mainly in Scotland, in preparation for a move overseas.

North Africa

On 11 June 1942, shortly before the division left forNorth Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, Graham was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(CBE) in that year's King's Birthday Honours

The Birthday Honours, in some Commonwealth realms, mark the reigning British monarch's official birthday by granting various individuals appointment into national or dynastic orders or the award of decorations and medals. The honours are present ...

. Departing the United Kingdom three days later, on 13 August Graham's brigade arrived in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, where the British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Forces, ...

, which the 51st Division was to form part of once fully trained and used to desert conditions, had just suffered a major reverse. Thus the division, only recently arrived in the theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

, missed the Battle of Alam el Halfa

The Battle of Alam el Halfa took place between 30 August and 5 September 1942 south of El Alamein during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War. '' Panzerarmee Afrika'' (''Generalfeldmarschall'' Erwin Rommel), attempted an envelopme ...

, but, after a period of training in desert warfare

In desert warfare, the heat and lack of water can sometimes be more dangerous than the enemy. The desert terrain is the second most inhospitable to troops following a cold environment. The lack of water, extremes of heat/cold, and lack of cover ma ...

, was called forward to join the Eighth Army at El Alamein

El Alamein ( ar, العلمين, translit=al-ʿAlamayn, lit=the two flags, ) is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Arab's Gulf, Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. , it had ...

, on the orders of Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

, the new Eighth Army commander, in order to play its part in Montgomery's new offensive.Mead, p. 185 The division was assigned initially to Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks

Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Gwynne Horrocks, (7 September 1895 – 4 January 1985) was a British Army officer, chiefly remembered as the commander of XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden and other operations during the Second World W ...

's XIII Corps, before transferring to Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese's XXX Corps, which was to play a leading role in the forthcoming offensive.

The offensive, the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

, began on the evening of 23 October, and was supported by a huge artillery barrage. Graham's brigade, given an assault role, quickly took their objectives – of advancing through the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

minefields to create a passage and enable the armour of Lieutenant General Herbert Lumsden

Lieutenant-General Herbert William Lumsden, & Bar, MC (8 April 1897 – 6 January 1945) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars. He commanded the 1st Armoured Division in the Western Desert camp ...

's X Corps 10th Corps, Tenth Corps, or X Corps may refer to:

France

* 10th Army Corps (France)

* X Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* X Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army

* ...

to pass through. The advance of Graham's brigade, after quickly overwhelming the defenders who were stunned from the massive artillery barrage, slowed against increasing resistance and the brigade's last objective could not be held, forcing a withdrawal. Consequently, the armour was unable to leave the minefields, and the 51st Division was forced onto the defensive. Montgomery, the army commander, then launched Operation Supercharge on 2 November, although Graham's brigade, given the role of maintaining pressure on the enemy, played a relatively minor role. On 14 January 1943 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

(DSO) for his actions on 2 November 1942 at El Alamein.

Following Alamein the brigade had a rest for a few weeks, absorbing replacements after suffering heavy losses, with the division as a whole having sustained some 2,800 casualties, and then, with the rest of the Eighth Army pursuing the retreating Axis forces, seeing light action at

Following Alamein the brigade had a rest for a few weeks, absorbing replacements after suffering heavy losses, with the division as a whole having sustained some 2,800 casualties, and then, with the rest of the Eighth Army pursuing the retreating Axis forces, seeing light action at El Agheila

El Agheila ( ar, العقيلة, translit=al-ʿUqayla ) is a coastal city at the southern end of the Gulf of Sidra in far western Cyrenaica, Libya. In 1988 it was placed in Ajdabiya District; it was in that district until 1995. It was removed from ...

, followed by Buerat. Graham continued to command his brigade as it joined the campaign in Tunisia, where he was involved in actions leading up to Operation Pugilist

The Battle of the Mareth Line or the Battle of Mareth was an attack in the Second World War by the British Eighth Army (General Bernard Montgomery) in Tunisia, against the Mareth Line held by the Italo-German 1st Army (General Giovanni Messe). I ...

, in particular an attack on outposts of the Mareth Line

The Mareth Line was a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. The line was intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the routes into T ...

on the night of 16/17 March, where his brigade suffered heavy losses due to an anti-tank ditch at Wadi Zigzaou, along with his performance up to the capture of Sfax

Sfax (; ar, صفاقس, Ṣafāqis ) is a city in Tunisia, located southeast of Tunis. The city, founded in AD849 on the ruins of Berber Taparura, is the capital of the Sfax Governorate (about 955,421 inhabitants in 2014), and a Mediterranean ...

, which won him a bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

to his DSO. The Battle of Wadi Akarit

The Battle of Wadi Akarit (Operation Scipio) was an Allied attack from 6 to 7 April 1943, to dislodge Axis forces from positions along the Wadi Akarit in Tunisia during the Tunisia Campaign of the Second World War. The Gabès Gap, north of the tow ...

followed soon afterwards, but Graham's brigade was held in reserve and unused, although it later spearheaded the Eighth Army's advance to Enfidaville, reaching near there on 23 April. Soon afterwards the division, selected by Montgomery (now a full general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

) for participation in the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It bega ...

, was withdrawn from the front lines into reserve.

In early May 1943 Graham was selected by Montgomery (who, along with Wimberley, thought very highly of the former) to be the new GOC of the

In early May 1943 Graham was selected by Montgomery (who, along with Wimberley, thought very highly of the former) to be the new GOC of the 56th (London) Infantry Division

The 56th (London) Infantry Division was a Territorial Army infantry division of the British Army, which served under several different titles and designations. The division served in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War. ...

, another TA formation, with the rank of acting major general, after the division's former GOC, Major General Eric Miles

Major-General Eric Grant Miles CB DSO MC (11 August 1891 – 3 November 1977) was a senior British Army officer who saw active service during both World War I and World War II, where he commanded the 126th Infantry Brigade in the Battle of F ...

, was severely wounded. The division, with only the 167th and 169th Infantry Brigades and supporting divisional troops under command, had only recently arrived in Tunisia, after travelling some 3,200 miles from Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and was assigned to X Corps, with Brigadier Lewis Lyne

Major-General Lewis Owen Lyne CB DSO (21 August 1899 – 4 November 1970) was a British Army officer who served before and during the Second World War. He saw distinguished active service in command of the 169th Brigade in action in North Afri ...

's 169th Brigade suffering heavy casualties in an attack on two hills, Points 141 and 130, on 28 April. On the night of 10 May the 167th Brigade was ordered to attack the Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

defenders on the hills north of Takrouna, which, although supported by artillery, failed, due to a combination of tenacious enemy resistance and very heavy shell and mortar fire, the defenders inflicting nearly 400 casualties upon the inexperienced brigade. However, the fighting in Tunisia ceased just three days later, with the surrender of some 238,000 Axis soldiers, many thousands surrendering to Graham's division alone.

Italy

Graham, along with his division (nicknamed "The Black Cats" due to its divisional insignia), was sent toLibya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

towards the end of May, where it began training in amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

, in preparation for the Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allied amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign (World War II), Italian campaign of World War II. The operation was undertaken by General (Unit ...

and, due to its casualties, was unable for participation in the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It bega ...

. Still with only two brigades (as the 168th Brigade, detached from the 56th Division in April, was temporarily serving with the 50th Division, which Graham would later command, in Sicily), in late July the division was reinforced with the veteran 201st Guards Brigade, under Brigadier Julian Gascoigne

Major-General Sir Julian Alvery Gascoigne, (25 October 1903 – 26 February 1990) was a senior British Army officer who served in the Second World War and became Major-General commanding the Household Brigade and General Officer Commanding Lon ...

, thus bringing the division up to strength with three brigades again. The division was assigned to Lieutenant General Brian Horrock's X Corps, then part of the American Fifth Army

The United States Army North (ARNORTH) is a formation of the United States Army. An Army Service Component Command (ASCC) subordinate to United States Northern Command (NORTHCOM), ARNORTH is the joint force land component of NORTHCOM.

under Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (May 1, 1896 – April 17, 1984) was a United States Army officer who saw service during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the US Army during World War II.

During World War I ...

and, although unavailable for Sicily, had been selected for participation in the Allied invasion of Italy

The Allied invasion of Italy was the Allied amphibious landing on mainland Italy that took place from 3 September 1943, during the Italian campaign (World War II), Italian campaign of World War II. The operation was undertaken by General (Unit ...

and commenced intensive training in amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducte ...

. Three weeks before the invasion the X Corps commander, Brian Horrocks, was severely injured by a lone German aircraft and was replaced soon after by Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery.

The 56th Division, supported by Sherman tank

}

The M4 Sherman, officially Medium Tank, M4, was the most widely used medium tank by the United States and Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman proved to be reliable, relatively cheap to produce, and available in great numbers. It w ...

s of the Royal Scots Greys

The Royal Scots Greys was a Cavalry regiments of the British Army, cavalry regiment of the British Army from 1707 until 1971, when they amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards) to form the Royal Scots Dragoon Guard ...

(with a squadron attached to each of the division's three brigades), came ashore at Salerno on 9 September 1943, facing light resistance, at least initially. The day before, news was received of the armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...

, the Italian surrender, and the Allies hoped resistance at Salerno would be light, although the severity of the fighting over the subsequent days would put paid to that theory. Despite this, the landings themselves had, for the most part, gone smoothly, and only the 16th Panzer Division

The 16th Panzer Division (german: 16. Panzer-Division) was a formation of the German Army in World War II. It was formed in November 1940 from the 16th Infantry Division. It took part in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union in ...

was nearby, although several other German formations were arriving.Mead, p. 185–186

The 56th Division's task was to capture, in addition to Montecorvino airfield, the road between Bellizi and Battipaglia

Battipaglia () is a municipality (''comune'') in the province of Salerno, Campania, south-western Italy.

Famed as a production place of buffalo mozzarella, Battipaglia is the economic hub of the Sele plain.

History

Formerly part of the ancien ...

, where it was to link up with Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Fred L. Walker

Major General Fred Livingood Walker (June 11, 1887 – October 6, 1969) was a highly decorated senior United States Army officer who served in both World War I and World War II and was awarded with the second highest military decorations in both ...

's US 36th Division to the division's right.Mead, p. 186 However, a huge gap seven-mile gap had emerged between Graham's division and Major General Ernest J. Dawley

Major General Ernest Joseph "Mike" Dawley (17 February 1886 – 10 December 1973) was a senior officer of the United States Army, best known during World War II for commanding the VI Corps during Operation Avalanche, the Allied landings at Sal ...

's US VI Corps (of which the US 36th Division formed part), with the River Sele

The Sele is a river in southwestern Italy. Originating from the Monti Picentini in Caposele,Meaning "top of the Sele" it flows through the region of Campania, in the provinces of Salerno and Avellino. Its mouth is in the Gulf of Salerno, on the ...

flowing through.

Graham ordered Brigadier Lyne, the 169th Brigade commander, to seize Montecorvino airfield, but, due to stubborn German resistance, and despite support from the Royal Scots Greys, the airfield remained in enemy hands for the next few days. However, the brigade managed to destroy a large number of German aircraft on the ground. The 167th Brigade captured Battipaglia but was repelled by a ferocious German counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

, in which flamethrower tank

A flame tank is a type of tank equipped with a flamethrower, most commonly used to supplement combined arms attacks against fortifications, confined spaces, or other obstacles. The type only reached significant use in the Second World War, dur ...

s were used, and horrendous losses were sustained, in particular to the 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in continuous existence for 283 years. It was known as the 7th Regiment of Foot until the Childers Reforms of 1881.

The regiment served in many wars ...

, with many men being captured. On 11 September, two days after the landings, Graham ordered Brigadier Gascoigne's 201st Brigade to capture the road west of Battipaglia and the tobacco factory to the north of Battipaglia, but the attack failed and the Guardsmen fell back to better defensive positions.

On 13 September the Germans, now with four divisions facing the Allies in the Salerno beachhead, launched a massive counterattack all across the beachhead, although it was focused mainly on the large gap between the Americans and the British. Graham, after consultation with Clark, the army commander, was allowed to retire to good defensive positions, thereby being able to repel the Germans with concentrated artillery fire. It was around this time that the crisis and the danger of the Allies being pushed into the sea being to slacken, and, after further heavy fighting, Battipaglia was taken by the 201st Guards Brigade on 18 September.

The division then cleared the Germans from their positions to the north of Salerno, while the 46th Division and the newly arrived 7th Armoured Division under Major General George Erskine

General Sir George Watkin Eben James Erskine (23 August 1899 – 29 August 1965) was a senior British Army officer who is most notable for having commanded the 7th Armoured Division from 1943 to 1944 during World War II, and leading major cou ...

took part in the capture of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. It was during this period that Company Sergeant Major Peter Wright of the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards

The Coldstream Guards is the oldest continuously serving regular regiment in the British Army. As part of the Household Division, one of its principal roles is the protection of the monarchy; due to this, it often participates in state ceremonia ...

, part of the 201st Brigade, was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

(VC). After this the division (which by now had sustained some 3,000 casualties at Salerno) advanced on the Fifth Army's left flank, eventually reaching the Volturno River

The Volturno (ancient Latin name Volturnus, from ''volvere'', to roll) is a river in south-central Italy.

Geography

It rises in the Abruzzese central Apennines of Samnium near Castel San Vincenzo (province of Isernia, Molise) and flows southea ...

, where the Germans had built up a defensive line

In gridiron football, a lineman is a player who specializes in play at the line of scrimmage. The linemen of the team currently in possession of the ball are the offensive line, while linemen on the opposing team are the defensive line. A numbe ...

. However, before the division could cross the river, Graham was injured, via a broken shoulder, on 10 October when his jeep tumbled into a shell crater after visiting his units in the front line

A front line (alternatively front-line or frontline) in military terminology is the position(s) closest to the area of conflict of an armed force's personnel and equipment, usually referring to land forces. When a front (an intentional or uninte ...

. As a result of his performance he was later appointed a U.S. Commander of the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight u ...

. He became a temporary major general on 14 May 1944. His Italian service also led to him being appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

(CB) on 24 August 1944. Command of the 56th Division passed temporarily to Brigadier Lyne, the 169th Brigade commander, before Major General Gerald Templer

Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer, (11 September 1898 – 25 October 1979) was a senior British Army officer. He fought in both the world wars and took part in the crushing of the Arab Revolt in Palestine. As Chief of the Imperia ...

arrived in Italy and became GOC on 15 October.

Northwest Europe

After being evacuated to hospital in the United Kingdom, by January 1944 Graham, after being

After being evacuated to hospital in the United Kingdom, by January 1944 Graham, after being mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

for his service in North Africa and Italy, was judged to be sufficiently recovered from his injuries to be given command of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, a highly experienced first-line TA formation which had served with distinction in North Africa and Sicily, in place of Major General Sidney Kirkman

General Sir Sidney Chevalier Kirkman, (29 July 1895 – 29 October 1982) was a British Army officer, who served in both the First World War and Second World War. During the latter he commanded the artillery of the Eighth Army during the Second B ...

, who was being given command of XIII Corps on the Italian front. Even at this stage of the war division GOCs with Graham's extensive battle experience were scarce. Comprising the 69th, 151st and 231st Infantry Brigade

The 231st Brigade was an infantry brigade of the British Army that saw active service in both the First and the Second World Wars. In each case it was formed by redesignation of existing formations. In the First World War, it fought in Palestine ...

s along with divisional troops, the 50th Division, with its considerable fighting experience, was brought back from Sicily in November 1943 to spearhead the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

, codenamed Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The operat ...

. However, after so much time spent fighting overseas, and, after being informed that the division was to play a leading role in the invasion, (replacing Major General Evelyn Barker

General Sir Evelyn Hugh Barker (22 May 1894 – 23 November 1983) was a British Army officer who saw service in both the First World War and the Second World War. During the latter, he commanded the 10th Brigade during the Battle of France in ...

's 49th Division, the initial choice) morale in the 50th Division was not high, with many veterans believing they had done more than fair share of the fighting, although morale later improved, due to Graham's leadership. The division was assigned to XXX Corps, under Lieutenant General Gerard Bucknall

Lieutenant General Gerard Corfield Bucknall, (14 September 1894 – 7 December 1980) was a senior British Army officer who served in both the First and Second World Wars. He is most notable for being the commander of XXX Corps during the Norman ...

, which itself was part of the British Second Army

The British Second Army was a field army active during the First and Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front throughout most of the war and later active in Italy. During the Second World War the army ...

, commanded by Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in north west Europe. A highly professional an ...

(Graham's brigade commander in France from 1939 to 1940), and, supported by the 56th Independent Infantry Brigade and the 8th Armoured Brigade, was to land at Gold Beach

Gold, commonly known as Gold Beach, was the code name for one of the five areas of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, during the Second World War. Gold, the central of the five areas, was lo ...

on D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as D ...

. For the invasion itself Graham had some 38,000 troops, more than twice the average strength of a division, under his command.

The division fought during the initial beach assault on Gold Beach, where Graham was again mentioned in despatches for his contributions to the campaign, and later was made an Officer of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

. Graham's rank of major general was made substantive on 6 October 1944 (with seniority from 1 February). Landing in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

in the early hours of 6 June 1944, the division initially met light resistance on the beaches, and, by the end of D-Day, had penetrated inland as far as Bayeux

Bayeux () is a Communes of France, commune in the Calvados (department), Calvados Departments of France, department in Normandy (administrative region), Normandy in northwestern France.

Bayeux is the home of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts ...

, the division's main objective, which was occupied the following day. The division also gained, on D-Day, the first and only VC to be awarded to be British or Commonwealth servicemen on the day, belonging to Company Sergeant Major Stanley Hollis

Stanley Elton Hollis VC (21 September 1912 – 8 February 1972) was a British recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces ...

of the 6th Battalion, Green Howards

The Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment), frequently known as the Yorkshire Regiment until the 1920s, was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, in the King's Division. Raised in 1688, it served under vario ...

. Thereafter resistance stiffened as the 50th advanced to Tilly-sur-Seulles

Tilly-sur-Seulles (, literally ''Tilly on Seulles'') is a commune in the Calvados department in the Normandy region in northwestern France.

Population

Events

Each year, the international motocross takes place.

See also

*Communes of the Cal ...

, to be halted by the Panzer Lehr Division

The Panzer-Lehr-Division (in the meaning of: Armoured training division) was an elite German armoured division during World War II. It was formed in 1943 onwards from training and demonstration troops (''Lehr'' = "teach") stationed in Germany, ...

, and, after further fierce fighting around Tilly-sur Seulles, the rest of the month for the 50th Division, on the boundary with Lieutenant General Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893April 8, 1981) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. Bradley ...

's U.S. First Army

First Army is the oldest and longest-established field army of the United States Army. It served as a theater army, having seen service in both World War I and World War II, and supplied the US army with soldiers and equipment during the Kore ...

, was spent mainly in holding the line, with most of the fighting being centred to the east around the city of Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,

Progress for the Allied armies in Normandy remained slow, and the 50th Division, towards the end of July, took part in

Graham retired from the army on 6 February 1947. Between 22 August 1954 and 26 March 1958 he was the Colonel of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He also served as Deputy Lieutenant of the

Graham retired from the army on 6 February 1947. Between 22 August 1954 and 26 March 1958 he was the Colonel of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He also served as Deputy Lieutenant of the

British Army Officers 1939−1945

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Graham, Douglas 1893 births 1971 deaths Alumni of the University of Glasgow Burials at the Glasgow Necropolis British Army major generals British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I British military personnel of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine Cameronians officers Commanders of the Legion of Merit Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of the Bath Deputy Lieutenants of Ross and Cromarty Foreign recipients of the Legion of Merit Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Officiers of the Légion d'honneur People educated at the Glasgow Academy People from Angus, Scotland People from Brechin Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Field Artillery officers Scottish generals Scottish soldiers Military personnel from Angus, Scotland

Operation Bluecoat

Operation Bluecoat was a British offensive in the Battle of Normandy, from 30 July until 7 August 1944, during the Second World War. The geographical objectives of the attack, undertaken by VIII Corps and XXX Corps of the British Second Army (L ...

, an attack on Mont Pinçon

Mont Pinçon is the highest point of the department of Calvados, in Normandy, with an elevation of . It is in the west of Norman Switzerland about to the south-west of Caen, near the village of Plessis-Grimoult.

It was the site of many strateg ...

, which was launched at around the same time as the Americans launched Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was the codename for an Offensive (military), offensive launched by the United States First United States Army, First Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Invasion of Norman ...

.Mead, p. 187 After heavy fighting at Amaye-sur-Suelles, the division then captured Villers-Bocage, earning praise from the new XXX Corps commander, Lieutenant General Horrocks (who described Graham in his autobiography as "an old war horse never far from the scene of battle"), and eventually found itself lined up along the northern flank of the Falaise Pocket, where the Germans were now retreating to, and where the Battle of Normandy was, after months of severe fighting, was finally won and thousands of Germans were captured. During the campaign in Normandy the 50th "Tyne Tees" Division (so nicknamed because of its division insignia, representing the division's pre-war recruiting area) had suffered almost 6,000 casualties, the second highest of any British division in France (the British 3rd Division under Major General "Bolo" Whistler gaining the dubious honour of having suffered the most, with over 7,100 casualties being sustained). However, of the three veteran divisions returned from the Mediterranean in late 1943, the 50th had, in the opinions of Montgomery, Dempsey and Horrocks, performed the best and this was due largely to Graham's leadership.

In the aftermath of the destruction of a large part of the German Army in the West, the Allies began their pursuit of the Germans through France and Belgium to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

itself (see Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine

The Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine, also known as the Siegfried Line campaign, was a phase in the Western European campaign of World War II.

This phase spans from the end of the Battle of Normandy, or Operation Overlord, (25 August 194 ...

). 50th Division, however, played a relatively minor role in the pursuit, but, after a brief rest, was ordered to the front once again in early September, where it fought in the Battle of Geel

The Battle of Geel, also known as the Battle of the Geel Bridgehead, was a battle between British and German troops near Geel (Gheel) in Belgium. It occurred between 8 and 23 September 1944 and was one of the largest and bloodiest battles to occu ...

. Again playing only a minor role in Operation Market Garden

Operation Market Garden was an Allies of World War II, Allied military operation during the World War II, Second World War fought in the Netherlands from 17 to 27 September 1944. Its objective was to create a Salient (military), salient into G ...

− Montgomery's attempt to cross the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

and end the war before Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

− the division instead spent the next few weeks garrisoning "The Island", the area between the River Waal

The Waal (Dutch name, ) is the main distributary branch of the river Rhine flowing approximately through the Netherlands. It is the major waterway connecting the port of Rotterdam to Germany. Before it reaches Rotterdam, it joins with the Afg ...

and the Lower Rhine

The Lower Rhine (german: Niederrhein; kilometres 660 to 1,033 of the river Rhine) flows from Bonn, Germany, to the North Sea at Hook of Holland, Netherlands (including the Nederrijn or "Nether Rhine" within the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta); al ...

, after the operation failed, in turn relieving the 43rd Division, commanded by Major General Ivor Thomas, who had been one of Graham's fellow students at the Staff College in the mid-1920s. On "The Island" static warfare replaced the fast and mobile warfare of the previous few weeks.

In early October Graham received a leg injury and returned to England for recovery, his place as GOC being taken over by Major General Lyne, formerly Graham's senior brigade commander in the 56th Division before taking over the 59th (Staffordshire) Infantry Division. Graham returned to the 50th Division as GOC once again in late November, by which time the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

had decided to break up the division, although, because of its distinguished history it was reduced to the role of a reserve division. The British Army was, by this stage of the war, suffering from a very severe shortage of manpower, and there simply were not enough men to keep all the active divisions up to strength and this, combined with Montgomery's belief that the division was no longer combat-worthy (and his sudden and harsh assessment of Graham, who he had previously thought very highly of, as being too old and only fit for a training command), was the main reason why the 50th Division was chosen for disbandment. Returning to England in December, the division became a reserve training formation, keeping its three infantry brigades but losing most of its supporting artillery and engineer units, and was given the role of training soldiers who had completed their basic training before being sent to an overseas unit. Graham received a further mention in despatches for "gallant and distinguished services in North West Europe" on 22 March 1945.

In August 1945, with the war in Europe now over, the 50th Division HQ ceased to exist and, upon moving to Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, was redesignated HQ British Land Forces Norway, with Graham as its GOC. In Norway he was GOC British Land Forces Norway where he convened the trial for war crimes of 10 German soldiers by a Military Court

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

held at the law courts, Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, Norway. The accused were charged with committing a war crime, in that they at Ulven, Norway, in or about the month of July 1943, in violation of the laws and usages of war, were concerned in the killing of Lieutenant A. H. Andresen, Petty Officer B. Kleppe, Leading Stoker A. Bigseth, Able Seaman J. Klipper, Able Seaman G. B. Hansen, and Able Seaman K. Hals, Royal Norwegian Navy, and Leading Telegraphist R. Hull, Royal Navy, prisoners of war. For his services to Norway, he was made a Commander of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav.

Postwar and later life

Graham retired from the army on 6 February 1947. Between 22 August 1954 and 26 March 1958 he was the Colonel of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He also served as Deputy Lieutenant of the

Graham retired from the army on 6 February 1947. Between 22 August 1954 and 26 March 1958 he was the Colonel of the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). He also served as Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Ross and Cromarty

Ross and Cromarty ( gd, Ros agus Cromba), sometimes referred to as Ross-shire and Cromartyshire, is a variously defined area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. There is a registration county and a lieutenancy area in current use, the latt ...

from 11 June 1956 until his resignation on 15 March 1960.

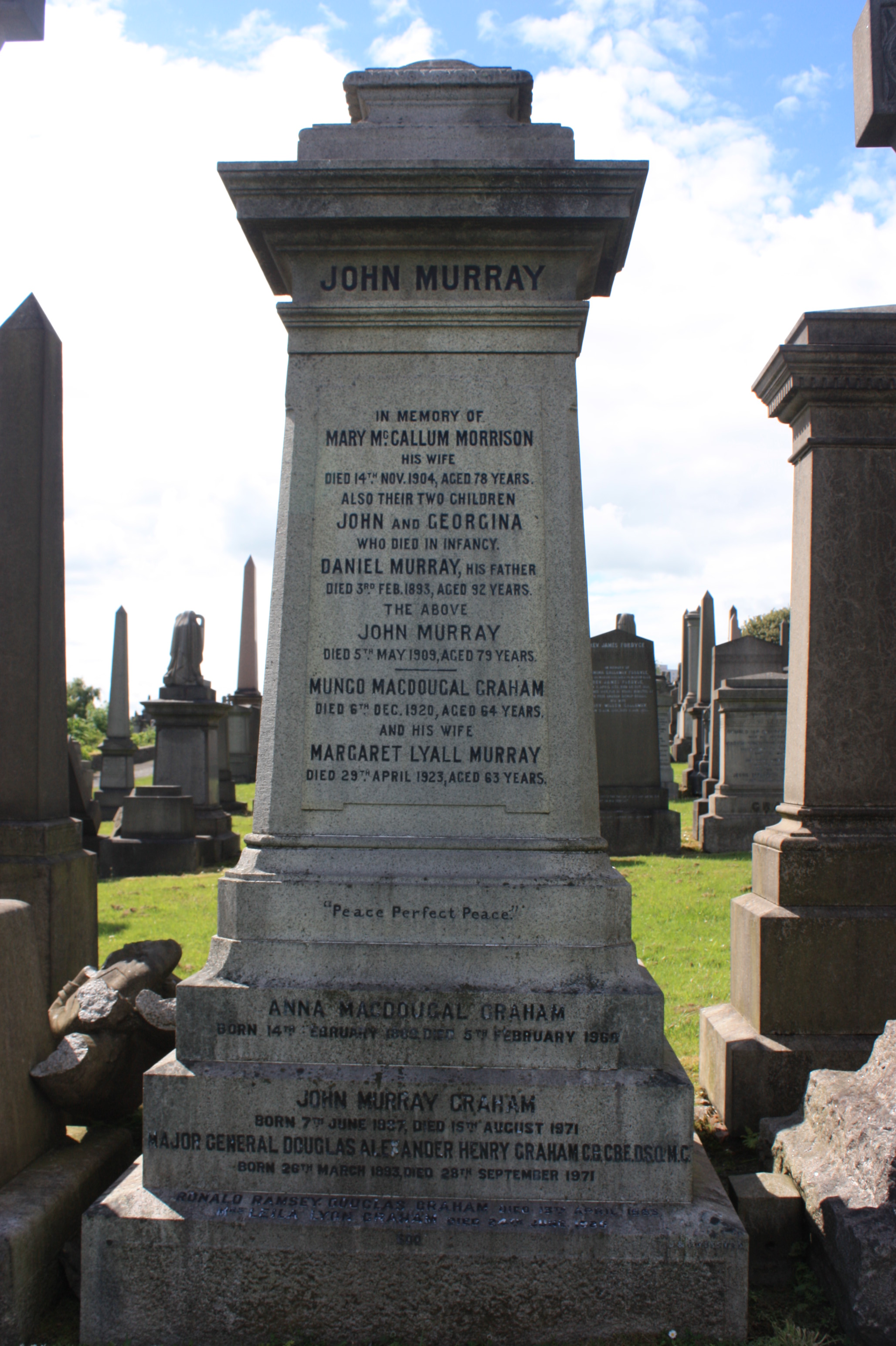

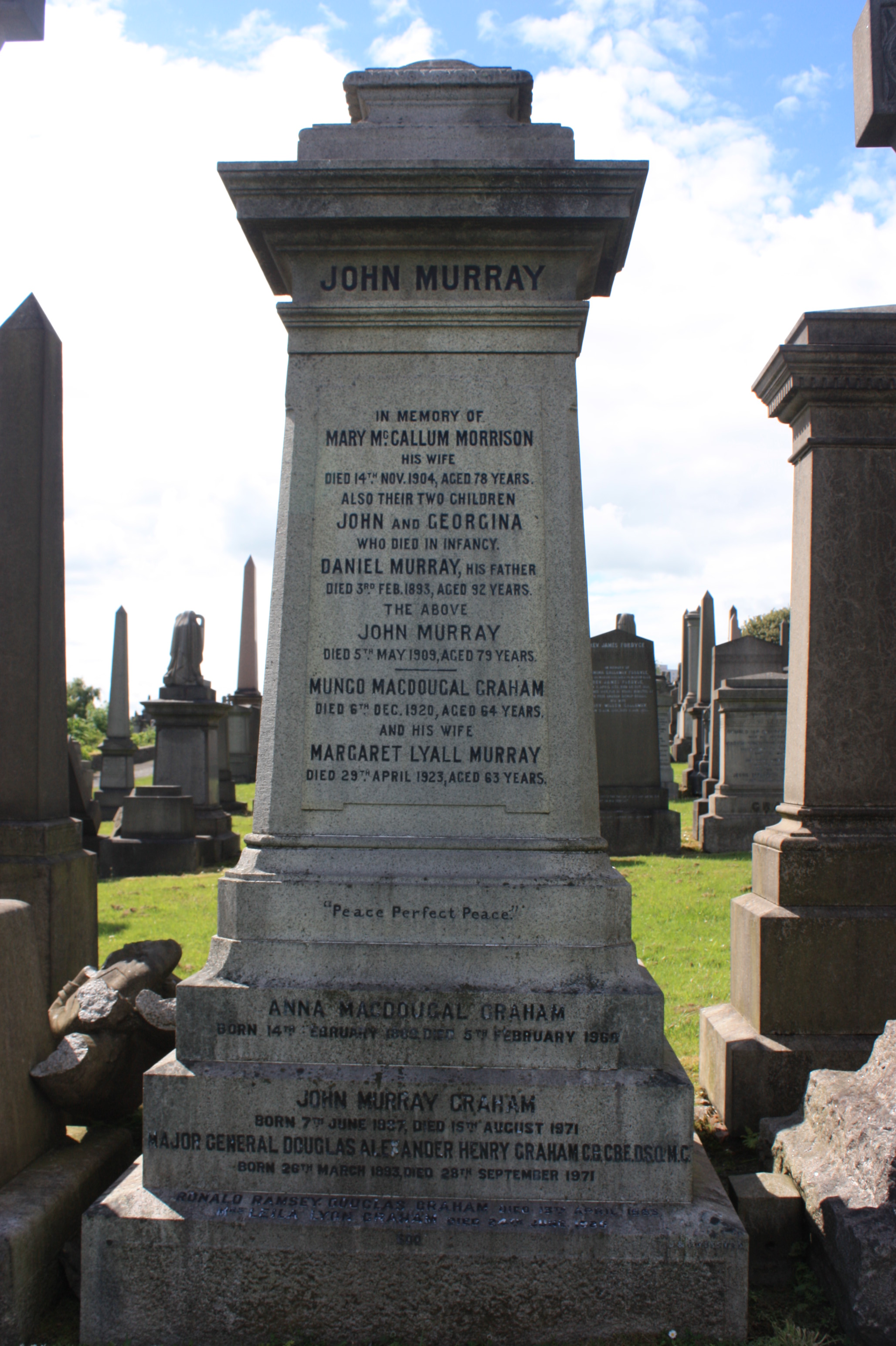

He died on 28 September 1971, a few weeks after the early death of his second son, John Murray Graham. He is buried in the John Murray plot at the top of Glasgow Necropolis

The Glasgow Necropolis is a Victorian cemetery in Glasgow, Scotland. It is on a low but very prominent hill to the east of Glasgow Cathedral (St. Mungo's Cathedral). Fifty thousand individuals have been buried here. Typical for the period, only ...

.

"Highly respected by his colleagues and subordinates for his positive disposition − in "Gertie" Tuker's words "He seemed in all battles to share with Freyberg of the New Zealanders

New Zealanders ( mi, Tāngata Aotearoa), colloquially known as Kiwis (), are people associated with New Zealand, sharing a common history, culture, and language (New Zealand English). People of various ethnicities and national origins are citiz ...

a cheerful spirit of optimism, so estimable a virtue in a battle commander" − he was a most competent soldier", possessing "firm religious convictions" and "indomitable courage".

References

Bibliography

* * * * Williams, David. ''The Black Cats at War: The Story of the 56th (London) Division T.A., 1939–1945'' . *''The D-Day Encyclopedia''. (ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: .External links

British Army Officers 1939−1945

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Graham, Douglas 1893 births 1971 deaths Alumni of the University of Glasgow Burials at the Glasgow Necropolis British Army major generals British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I British military personnel of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine Cameronians officers Commanders of the Legion of Merit Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Companions of the Order of the Bath Deputy Lieutenants of Ross and Cromarty Foreign recipients of the Legion of Merit Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Officiers of the Légion d'honneur People educated at the Glasgow Academy People from Angus, Scotland People from Brechin Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the Military Cross Royal Field Artillery officers Scottish generals Scottish soldiers Military personnel from Angus, Scotland