Cuba Cienfuegos BennyMore (www on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an

Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 12 November 2015 Culturally, Cuba is considered part of

The Caribbean ground sloths, one of the last survivors of the

The Caribbean ground sloths, one of the last survivors of the

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at  By 1570, most residents of Cuba comprised a mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno heritages. Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. Most importantly, the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, there were 50,000 slaves on the island, compared to 60,000 in

By 1570, most residents of Cuba comprised a mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno heritages. Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. Most importantly, the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, there were 50,000 slaves on the island, compared to 60,000 in

''The William and Mary Quarterly'' Vol. 25, No. 2 (Apr. 1968), pp. 307–309, in JSTOR, accessed 1 March 2015 The Though Havana, which had become the third-largest city in the Americas, was to enter an era of sustained development and increasing ties with North America during this period, the British occupation of the city proved short-lived. Pressure from London to sugar merchants, fearing a decline in sugar prices, forced negotiations with the Spanish over the captured territories. Less than a year after Britain captured Havana, it signed the 1763 Treaty of Paris together with France and Spain, ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain

Though Havana, which had become the third-largest city in the Americas, was to enter an era of sustained development and increasing ties with North America during this period, the British occupation of the city proved short-lived. Pressure from London to sugar merchants, fearing a decline in sugar prices, forced negotiations with the Spanish over the captured territories. Less than a year after Britain captured Havana, it signed the 1763 Treaty of Paris together with France and Spain, ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain  Although a smaller proportion of the population of Cuba was enslaved, at times, slaves arose in revolt. In 1812, the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place, but it was ultimately suppressed. The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980 (of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves).

In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, the practice of had developed (or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development"), according to historian Herbert S. Klein. Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers." A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in

Although a smaller proportion of the population of Cuba was enslaved, at times, slaves arose in revolt. In 1812, the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place, but it was ultimately suppressed. The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980 (of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves).

In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, the practice of had developed (or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development"), according to historian Herbert S. Klein. Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers." A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in

Full independence from Spain was the goal of a rebellion in 1868 led by planter

Full independence from Spain was the goal of a rebellion in 1868 led by planter

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and

After the

After the

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change. In 1956,

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change. In 1956,  The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban Revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America. Castro's legalization of the Communist Party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen, and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries. The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations. In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S. In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.

In March 1960, U.S. President

The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban Revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America. Castro's legalization of the Communist Party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen, and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries. The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations. In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S. In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.

In March 1960, U.S. President  In 1963, Cuba sent 686 troops together with 22 tanks and other military equipment to support Algeria in the

In 1963, Cuba sent 686 troops together with 22 tanks and other military equipment to support Algeria in the  Effective 14 January 2013, Cuba ended the requirement established in 1961, that any citizens who wish to travel abroad were required to obtain an expensive government permit and a letter of invitation. In 1961 the Cuban government had imposed broad restrictions on travel to prevent the mass emigration of people after the 1959 revolution; it approved exit visas only on rare occasions. Requirements were simplified: Cubans need only a passport and a national ID card to leave; and they are allowed to take their young children with them for the first time. However, a passport costs on average five months' salary. Observers expect that Cubans with paying relatives abroad are most likely to be able to take advantage of the new policy. In the first year of the program, over 180,000 left Cuba and returned.

, talks with Cuban officials and American officials, including President

Effective 14 January 2013, Cuba ended the requirement established in 1961, that any citizens who wish to travel abroad were required to obtain an expensive government permit and a letter of invitation. In 1961 the Cuban government had imposed broad restrictions on travel to prevent the mass emigration of people after the 1959 revolution; it approved exit visas only on rare occasions. Requirements were simplified: Cubans need only a passport and a national ID card to leave; and they are allowed to take their young children with them for the first time. However, a passport costs on average five months' salary. Observers expect that Cubans with paying relatives abroad are most likely to be able to take advantage of the new policy. In the first year of the program, over 180,000 left Cuba and returned.

, talks with Cuban officials and American officials, including President

island country

An island country, island state or an island nation is a country whose primary territory consists of one or more islands or parts of islands. Approximately 25% of all independent countries are island countries. Island countries are historically ...

comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

s. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

, Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

, and Atlantic Ocean meet. Cuba is located east of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

(Mexico), south of both the American state of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

and the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, west of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

(Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

/Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

), and north of both Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and the Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands () is a self-governing British Overseas Territory—the largest by population in the western Caribbean Sea. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac and Little Cayman, which are located to the ...

. Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

is the largest city and capital; other major cities include Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

and Camagüey

Camagüey () is a city and municipality in central Cuba and is the nation's third-largest city with more than 321,000 inhabitants. It is the capital of the Camagüey Province.

It was founded as Santa María del Puerto del Príncipe in 1514, by S ...

. The official area of the Republic of Cuba is (without the territorial waters) but a total of 350,730 km² (135,418 sq mi) including the exclusive economic zone. Cuba is the second-most populous country in the Caribbean after Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, with over 11 million inhabitants.

The territory that is now Cuba was inhabited by the Ciboney

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Classi ...

people from the 4th millennium BC

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. ...

with the Guanahatabey

The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and cu ...

and Taino peoples until Spanish colonization

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

in the 15th century. From the 15th century, it was a colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, and slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

was abolished in 1886, until the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

of 1898, when Cuba was occupied by the United States and gained independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

in 1902. In 1940, Cuba implemented a new constitution, but mounting political unrest culminated in a coup in 1952 and the subsequent dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

, which was later overthrown in January 1959 by the 26th of July Movement during the Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution ( es, Revolución Cubana) was carried out after the 1952 Cuban coup d'état which placed Fulgencio Batista as head of state and the failed mass strike in opposition that followed. After failing to contest Batista in cou ...

, which afterwards established communist rule under the leadership of Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

. The country was a point of contention during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and the United States, and a nuclear war nearly broke out during the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

of 1962. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba faced a severe economic downturn in the 1990s, known as the Special Period

The Special Period ( es, Período especial, link=no), officially the Special Period in the Time of Peace (), was an extended period of economic crisis in Cuba that began in 1991 primarily due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and, by exten ...

. In 2008, Fidel Castro resigned after 49 years of leadership of Cuba and was replaced by his brother Raúl Castro

Raúl Modesto Castro Ruz (; ; born 3 June 1931) is a retired Cuban politician and general who served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the one-party communist state, from 2011 to 2021, succeedi ...

.

Cuba is one of a few extant Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

one-party

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government ...

socialist states

Several past and present states have declared themselves socialist states or in the process of building socialism. The majority of self-declared socialist countries have been Marxist–Leninist or inspired by it, following the model of the Sovi ...

, in which the role of the vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

Communist Party is enshrined in the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. Cuba has an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

regime where political opposition is not permitted. Censorship of information (including limits to Internet access) is extensive, and independent journalism is repressed in Cuba; Reporters Without Borders has characterized Cuba as one of the worst countries in the world for press freedom."Press Freedom Index 2015"Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 12 November 2015 Culturally, Cuba is considered part of

Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

. It is a multiethnic country whose people

A person (plural, : people) is a being that has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form of social relations such as kinship, ownership of pr ...

, culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

and customs derive from diverse origins, including the Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

Ciboney

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Classi ...

peoples, the long period

Long may refer to:

Measurement

* Long, characteristic of something of great duration

* Long, characteristic of something of great length

* Longitude (abbreviation: long.), a geographic coordinate

* Longa (music), note value in early music mens ...

of Spanish colonialism

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its predece ...

, the introduction of enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

and a close relationship with the Soviet Union in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

.

Cuba is a founding member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

, the G77, the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath o ...

, the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States

The Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS) is a group of countries in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific that was created by the Georgetown Agreement in 1975. Formerly known as African, Caribbean and Pacific Group ...

, ALBA

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scottish people, Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed i ...

, and the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

. It has currently one of the world's few planned economies

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, par ...

, and its economy is dominated by the tourism industry and the exports of skilled labor, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. Cuba has historically—both before and during communist rule—performed better than other countries in the region on several socioeconomic indicators, such as literacy, infant mortality and life expectancy.

Etymology

Historians believe the name ''Cuba'' comes from theTaíno language

Taíno is an extinct Arawakan language that was spoken by the Taíno people of the Caribbean. At the time of Spanish contact, it was the most common language throughout the Caribbean. Classic Taíno (Taíno proper) was the native language of th ...

, however "its exact derivation sunknown". The exact meaning of the name is unclear but it may be translated either as 'where fertile land is abundant' (''cubao''), or 'great place' (''coabana'').

Fringe theory

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint which differs from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such a ...

writers who believe that Christopher Columbus was Portuguese state that ''Cuba'' was named by Columbus for the town of Cuba in the district of Beja in Portugal.

History

Pre-Columbian era

pleistocene megafauna

Pleistocene megafauna is the set of large animals that lived on Earth during the Pleistocene epoch. Pleistocene megafauna became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event resulting in substantial changes to ecosystems globally. The role of ...

, lived in Cuba possibly until 2660 BCE.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, Cuba was inhabited by two distinct tribes of indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

: the Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

(including the Ciboney

The Ciboney, or Siboney, were a Taíno people of western Cuba, Jamaica, and the Tiburon Peninsula of Haiti. A Western Taíno group living in central Cuba during the 15th and 16th centuries, they had a dialect and culture distinct from the Classi ...

people), and the Guanahatabey

The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and cu ...

.

The ancestors of the Taíno migrated from the mainland of South America, with the earliest sites dated to 5,000 BP.

The Taíno arrived from Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

sometime in the 3rd century A.D. When Columbus arrived, they were the dominant culture in Cuba, having an estimated population of 150,000. It is unknown when or how the Guanahatabey

The Guanahatabey (also spelled Guanajatabey) were an indigenous people of western Cuba at the time of European contact. Archaeological and historical studies suggest the Guanahatabey were archaic hunter-gatherers with a distinct language and cu ...

arrived in Cuba, having both a different language and culture than the Taíno; it is inferred that they were a relict population

In biogeography and paleontology, a relict is a population or taxon of organisms that was more widespread or more diverse in the past. A relictual population is a population currently inhabiting a restricted area whose range was far wider during a ...

of pre-Taíno settlers of the Greater Antilles.

The Taíno were farmers, as well as fishers and hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s.

Spanish colonization and rule (1492–1898)

After first landing on an island then calledGuanahani

Guanahaní is an island in the Bahamas that was the first land in the New World sighted and visited by Christopher Columbus' first voyage, on 12 October 1492. It is a bean-shaped island that Columbus changed from its native Taíno name to San Sa ...

, Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, on 12 October 1492, (gives the landing date in Cuba as 27 October) Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

commanded his three ships: '' La Pinta,'' ''La Niña

''La Niña'' ( Spanish for ''The Girl'') was one of the three Spanish ships used by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus in his first voyage to the West Indies in 1492. As was tradition for Spanish ships of the day, she bore a female saint's n ...

'' and the '' Santa María'', discovering Cuba on 27 October 1492, and landing in the northeastern coast on 28 October. (This was near what is now Bariay, Holguín Province

Holguín () is one of the provinces of Cuba, the third most populous after Havana and Santiago de Cuba. It lies in the southeast of the country. Its major cities include Holguín (the capital), Banes, Antilla, Mayarí, and Moa.

The province ...

.) Columbus claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and named it ''Isla Juana'' after John, Prince of Asturias

John, Prince of Asturias and Girona ( es, Juan; 30 June 1478 – 4 October 1497), was the only son of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, and heir-apparent to both their thrones for nearly his entire life.

Early lif ...

.

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa

Baracoa, whose full original name is: ''Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa'' (“Our Lady of the Assumption of Baracoa”), is a municipality and city in Guantánamo Province near the eastern tip of Cuba. It was visited by Admiral Christop ...

. Other settlements soon followed, including San Cristobal de la Habana, founded in 1515, which later became the capital. The indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

were forced to work under the encomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

system, which resembled the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

in medieval Europe. Within a century, the indigenous people were virtually wiped out due to multiple factors, primarily Eurasian infectious diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, to which they had no natural resistance (immunity), aggravated by the harsh conditions of the repressive colonial subjugation. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of those few natives who had previously survived smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

.

On 18 May 1539, conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

departed from Havana with some 600 followers into a vast expedition through the American Southeast

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern por ...

, starting in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, in search of gold, treasure, fame and power. On 1 September 1548, Dr. Gonzalo Perez de Angulo was appointed governor of Cuba. He arrived in Santiago, Cuba, on 4 November 1549, and immediately declared the liberty of all natives. He became Cuba's first permanent governor to reside in Havana instead of Santiago, and he built Havana's first church made of masonry.

By 1570, most residents of Cuba comprised a mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno heritages. Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. Most importantly, the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, there were 50,000 slaves on the island, compared to 60,000 in

By 1570, most residents of Cuba comprised a mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno heritages. Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. Most importantly, the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, there were 50,000 slaves on the island, compared to 60,000 in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

and 300,000 in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

; as well as 450,000 in Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

, all of which had large-scale sugarcane plantations.Melvin Drimmer, "Reviewed Work: ''Slavery in the Americas: A Comparative Study of Virginia and Cuba'' by Herbert S. Klein"''The William and Mary Quarterly'' Vol. 25, No. 2 (Apr. 1968), pp. 307–309, in JSTOR, accessed 1 March 2015 The

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, which erupted in 1754 across three continents, eventually arrived in the Spanish Caribbean

The Spanish West Indies or the Spanish Antilles (also known as "Las Antillas Occidentales" or simply "Las Antillas Españolas" in Spanish) were Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. In terms of governance of the Spanish Empire, The Indies was the de ...

. Spain's alliance with the French pitched them into direct conflict with the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, and in 1762, a British expedition consisting of dozens of ships and thousands of troops set out from Portsmouth to capture Cuba. The British arrived on 6 June, and by August, had placed Havana under siege.Thomas, Hugh. ''Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (2nd edition)''. Chapter One. When Havana surrendered, the admiral of the British fleet, George Pocock

Admiral Sir George Pocock or Pococke, KB (6 March 1706 – 3 April 1792) was a British officer of the Royal Navy.

Family

Pocock was born in Thames Ditton in Surrey, the son of Thomas Pocock, a chaplain in the Royal Navy. His great grandfa ...

and the commander of the land forces George Keppel, the 3rd Earl of Albemarle

Earl of Albemarle is a title created several times from Norman times onwards. The word ''Albemarle'' is derived from the Latinised form of the French county of ''Aumale'' in Normandy (Latin: ''Alba Marla'' meaning "White Marl", marl being a ty ...

, entered the city, and took control of the western part of the island. The British immediately opened up trade with their North American

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Ca ...

and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society.

Though Havana, which had become the third-largest city in the Americas, was to enter an era of sustained development and increasing ties with North America during this period, the British occupation of the city proved short-lived. Pressure from London to sugar merchants, fearing a decline in sugar prices, forced negotiations with the Spanish over the captured territories. Less than a year after Britain captured Havana, it signed the 1763 Treaty of Paris together with France and Spain, ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain

Though Havana, which had become the third-largest city in the Americas, was to enter an era of sustained development and increasing ties with North America during this period, the British occupation of the city proved short-lived. Pressure from London to sugar merchants, fearing a decline in sugar prices, forced negotiations with the Spanish over the captured territories. Less than a year after Britain captured Havana, it signed the 1763 Treaty of Paris together with France and Spain, ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in exchange for Cuba. Cubans constituted one of the many diverse units which fought alongside Spanish forces during the conquest of British West Florida (1779–81).

The largest factor for the growth of Cuba's commerce in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

. When the enslaved peoples of what had been the Caribbean's richest colony freed themselves through violent revolt, Cuban planters perceived the region's changing circumstances with both a sense of fear and opportunity. They were afraid because of the prospect that slaves might revolt in Cuba as well, and numerous prohibitions during the 1790s of the sale of slaves in Cuba who had previously been enslaved in French colonies underscored this anxiety. The planters saw opportunity, however, because they thought that they could exploit the situation by transforming Cuba into the slave society and sugar-producing "pearl of the Antilles" that Haiti had been before the revolution. As the historian Ada Ferrer has written, "At a basic level, liberation in Saint-Domingue helped entrench its denial in Cuba. As slavery and colonialism collapsed in the French colony, the Spanish island underwent transformations that were almost the mirror image of Haiti's." Estimates suggest that between 1790 and 1820 some 325,000 Africans were imported to Cuba as slaves, which was four times the amount that had arrived between 1760 and 1790.

Although a smaller proportion of the population of Cuba was enslaved, at times, slaves arose in revolt. In 1812, the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place, but it was ultimately suppressed. The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980 (of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves).

In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, the practice of had developed (or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development"), according to historian Herbert S. Klein. Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers." A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in

Although a smaller proportion of the population of Cuba was enslaved, at times, slaves arose in revolt. In 1812, the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place, but it was ultimately suppressed. The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980 (of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves).

In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, the practice of had developed (or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development"), according to historian Herbert S. Klein. Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers." A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal to Spain. Its economy was based on serving the empire. By 1860, Cuba had 213,167 free people of color (39% of its non-white population of 550,000).

Independence movements

Full independence from Spain was the goal of a rebellion in 1868 led by planter

Full independence from Spain was the goal of a rebellion in 1868 led by planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes del Castillo (18 April 1819, Bayamo, Spanish Cuba – 27 February 1874, San Lorenzo, Spanish Cuba) was a Cuban revolutionary hero and First President of Cuba in Arms in 1868. Cespedes, who was a plantation owner ...

. De Céspedes, a sugar planter, freed his slaves to fight with him for an independent Cuba. On 27 December 1868, he issued a decree condemning slavery in theory but accepting it in practice and declaring free any slaves whose masters present them for military service. The 1868 rebellion resulted in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

. A great number of the rebels were volunteers from the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

, and other countries, as well as numerous Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

.

The United States declined to recognize the new Cuban government, although many European and Latin American nations did so. In 1878, the Pact of Zanjón

The Pact of Zanjón ended the armed struggle of Cubans for independence from the Spanish Empire that lasted from 1868 to 1878, the Ten Years' War. On February 10, 1878, a group of negotiators representing the rebels gathered in Zanjón, a village ...

ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. In 1879–80, Cuban patriot Calixto García

Calixto García Íñiguez (August 4, 1839 – December 11, 1898) was a Cuban general in three Cuban uprisings, part of the Cuban War for Independence: the Ten Years' War, the Little War, and the War of 1895, itself sometimes called the Cuban ...

attempted to start another war known as the Little War but failed to receive enough support. Slavery in Cuba

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic Slave Trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practised on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish r ...

was abolished in 1875 but the process was completed only in 1886. An exiled dissident named José Martí

José Julián Martí Pérez (; January 28, 1853 – May 19, 1895) was a Cuban nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, who is considered a Cuban national hero because of his role in the libera ...

founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York in 1892. The aim of the party was to achieve Cuban independence from Spain. In January 1895, Martí traveled to Monte Cristi and Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

in the Dominican Republic to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez

Máximo Gómez y Báez (November 18, 1836 – June 17, 1905) was a Dominican Generalissimo in Cuba's War of Independence (1895–1898). He was known for his controversial scorched-earth policy, which entailed dynamiting passenger trains a ...

. Martí recorded his political views in the '' Manifesto of Montecristi''. Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Martí was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895. Martí was killed in the Battle of Dos Rios

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

on 19 May 1895. His death immortalized him as Cuba's national hero.

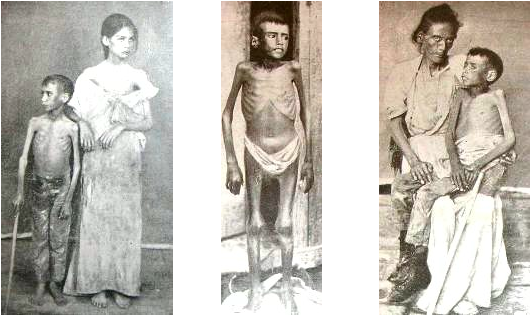

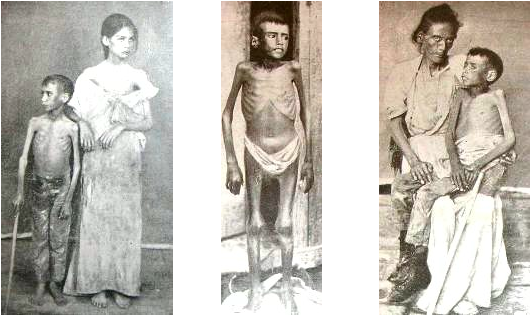

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identitie ...

tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler

Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, 1st Duke of Rubí, 1st Marquess of Tenerife (17 September 1838 – 20 October 1930) was a Spanish general and colonial administrator who served as the Governor-General of the Philippines and Cuba, and later as S ...

, the military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called , described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th-century concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

. Between 200,000 and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the Spanish concentration camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

and United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

Redfield Proctor

Redfield Proctor (June 1, 1831March 4, 1908) was a U.S. politician of the Republican Party. He served as the 37th governor of Vermont from 1878 to 1880, as Secretary of War from 1889 to 1891, and as a United States Senator for Vermont from 189 ...

, a former Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

. American and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.

The U.S. battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

USS ''Maine'' was sent to protect American interests, but soon after arrival, it exploded in Havana harbor and sank quickly, killing nearly three-quarters of the crew. The cause and responsibility for the sinking of the ship remained unclear after a board of inquiry. Popular opinion in the U.S., fueled by an active press, concluded that the Spanish were to blame and demanded action. Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April 1898.

Republic (1902–1959)

First years (1902–1925)

After the

After the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898)

The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain, commonly known as the Treaty of Paris of 1898 ( fil, Kasunduan sa Paris ng 1898; es, Tratado de París de 1898), was a treaty signed by Spain and the United Stat ...

, by which Spain ceded Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

to the United States for the sum of and Cuba became a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

of the United States. Cuba gained formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, as the Republic of Cuba. Under Cuba's new constitution, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment

On March 2, 1901, the Platt Amendment was passed as part of the 1901 Army Appropriations Bill.Guantánamo Bay Naval Base

Guantanamo Bay Naval Base ( es, Base Naval de la Bahía de Guantánamo), officially known as Naval Station Guantanamo Bay or NSGB, (also called GTMO, pronounced Gitmo as jargon by members of the United States Armed Forces, U.S. military) is a ...

from Cuba.

Following disputed elections in 1906, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma

Tomás Estrada Palma (c. July 6, 1832 – November 4, 1908) was a Cuban politician, the president of the Cuban Republican in Arms during the Ten Years' War, and the first President of Cuba, between May 20, 1902, and September 28, 1906.

His coll ...

, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces. The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon

Charles Edward Magoon (December 5, 1861 – January 14, 1920) was an American lawyer, judge, diplomat, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor of the Panama Canal Zone; he also served as Minister to Panama at the same time. Hi ...

as Governor for three years. Cuban historians have characterized Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption.. In 1908, self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez

José Miguel Gómez y Arias (6 July 1858 – 13 June 1921) was a Cuban politician and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the rebel forces in the History of Cuba, Cuban War of Independence. He later served as President of Cuba from 1909 ...

was elected president, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912, the Partido Independiente de Color Partido, partidista and partidario may refer to:

* Spanish for a political party, people who share political ideology or who are brought together by common issues

Territorial subdivision

* Partidos of Buenos Aires, the second-level administrative ...

attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province, but was suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

In 1924, Gerardo Machado was elected president. During his administration, tourism increased markedly, and American-owned hotels and restaurants were built to accommodate the influx of tourists. The tourist boom led to increases in gambling and prostitution in Cuba

Prostitution in Cuba is not officially illegal; however, there is legislation against pimps, sexual exploitation of minors, and pornography. Sex tourism has existed in the country, both before and after the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Many Cubans do not ...

. The Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

led to a collapse in the price of sugar, political unrest, and repression. Protesting students, known as the Generation of 1930, turned to violence in opposition to the increasingly unpopular Machado. A general strike (in which the Communist Party sided with Machado), uprisings among sugar workers, and an army revolt forced Machado into exile in August 1933. He was replaced by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada (August 12, 1871 – March 28, 1939) was a Cuban writer, politician, diplomat, and President of Cuba.

Early life and career

He was the son of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and Ana Maria de Quesada y Loinaz. ...

.

Revolution of 1933–1940

In September 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt, led by SergeantFulgencio Batista

Fulgencio Batista y Zaldívar (; ; born Rubén Zaldívar, January 16, 1901 – August 6, 1973) was a Cuban military officer and politician who served as the elected president of Cuba from 1940 to 1944 and as its U.S.-backed military dictator ...

, overthrew Céspedes. A five-member executive committee (the Pentarchy of 1933) was chosen to head a provisional government. Ramón Grau San Martín Ramón or Ramon may refer to:

People Given name

* Ramon (footballer, born 1998), Brazilian footballer

* Ramón (footballer, born 1990), Brazilian footballer

*Ramón (singer), Spanish singer who represented Spain in the 2004 Eurovision Song Contest ...

was then appointed as provisional president. Grau resigned in 1934, leaving the way clear for Batista, who dominated Cuban politics for the next 25 years, at first through a series of puppet-presidents. The period from 1933 to 1937 was a time of "virtually unremitting social and political warfare". On balance, during the period 1933–1940 Cuba suffered from fragile politic structures, reflected in the fact that it saw three different presidents in two years (1935–1936), and in the militaristic and repressive policies of Batista as Head of the Army.

Constitution of 1940

A new constitution was adopted in 1940, which engineered radical progressive ideas, including the right to labor and health care.. Batista was elected president in the same year, holding the post until 1944. He is so far the only non-white Cuban to win the nation's highest political office. His government carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration.. Cuban armed forces were not greatly involved in combat during World War II—though president Batista did suggest a joint U.S.-Latin American assault onFrancoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

to overthrow its authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

regime. Cuba lost six merchant ships during the war, and the Cuban Navy was credited with sinking the .

Batista adhered to the 1940 constitution's strictures preventing his re-election. Ramon Grau San Martin was the winner of the next election, in 1944. Grau further corroded the base of the already teetering legitimacy of the Cuban political system, in particular by undermining the deeply flawed, though not entirely ineffectual, Congress and Supreme Court. Carlos Prío Socarrás

Carlos Manuel Prío Socarrás (July 14, 1903 – April 5, 1977) was a Cuban politician. He served as the President of Cuba from 1948 until he was deposed by a military coup led by Fulgencio Batista on March 10, 1952, three months before new ele ...

, a protégé of Grau, became president in 1948. The two terms of the Auténtico Party brought an influx of investment, which fueled an economic boom, raised living standards for all segments of society, and created a middle class in most urban areas..

Coup d'état of 1952

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

that preempted the election. Back in power, and receiving financial, military, and logistical support from the United States government, Batista suspended the 1940 Constitution and revoked most political liberties, including the right to strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the In ...

. He then aligned with the wealthiest landowners who owned the largest sugar plantations, and presided over a stagnating economy that widened the gap between rich and poor Cubans. Batista outlawed the Cuban Communist Party in 1952. After the coup, Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios, though about one-third of the population was considered poor and enjoyed relatively little of this consumption. However, in his "History Will Absolve Me

''History Will Absolve Me'' (Spanish: ''La historia me absolverá'') is the title of a two-hour speech made by Fidel Castro on 16 October 1953. Castro made the speech in his own defense in court against the charges brought against him after he led ...

" speech, Fidel Castro mentioned that national issues relating to land, industrialization, housing, unemployment, education, and health were contemporary problems.

In 1958, Cuba was a well-advanced country in comparison to other Latin American regions.. Cuba was also affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities. Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems.. Unemployment became a problem as graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs. The middle class, which was comparable to that of the United States, became increasingly dissatisfied with unemployment and political persecution. The labor unions, manipulated by the previous government since 1948 through union "yellowness", supported Batista until the very end. Batista stayed in power until he resigned in December 1958 under the pressure of the US Embassy and as the revolutionary forces headed by Fidel Castro were winning militarily (Santa Clara city, a strategic point in the middle of the country, fell into the rebels hands on December 31, in a conflict known as the Battle of Santa Clara

The Battle of Santa Clara was a series of events in late December 1958 that led to the capture of the Cuban city of Santa Clara by revolutionaries under the command of Che Guevara.

The battle was a decisive victory for the rebels fighting ag ...

).

Revolution and Communist Party rule (1959–present)

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change. In 1956,

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change. In 1956, Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

and about 80 supporters landed from the yacht ''Granma'' in an attempt to start a rebellion against the Batista government. In 1958, Castro's July 26th Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on Sa ...

emerged as the leading revolutionary group. The U.S. supported Castro by imposing a 1958 arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to "dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintain ...

against Batista's government. Batista evaded the American embargo and acquired weapons from the Dominican Republic, including Dominican-made Cristóbal Carbine

The .30 Kiraly-Cristóbal Carbine, also known as the San Cristóbal or Cristóbal Automatic Rifle was manufactured by the Dominican Republic’s Armería San Cristóbal Weapon Factory.

History and development

Although called a carbine, the gun ma ...

s, hand grenades, and mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a villag ...

.

By late 1958, the rebels had broken out of the Sierra Maestra

The Sierra Maestra is a mountain range that runs westward across the south of the old Oriente Province in southeast Cuba, rising abruptly from the coast. The range falls mainly within the Santiago de Cuba and in Granma Provinces. Some view it a ...

and launched a general popular insurrection. After Castro's fighters captured Santa Clara, Batista fled with his family to the Dominican Republic on 1 January 1959. Later he went into exile on the Portuguese island of Madeira and finally settled in Estoril, near Lisbon. Fidel Castro's forces entered the capital on 8 January 1959. The liberal Manuel Urrutia Lleó

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (December 8, 1901 – 5 July 1981) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. He campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president ...

became the provisional president.

According to Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

, official death sentences from 1959 to 1987 numbered 237 of which all but 21 were actually carried out. Other estimates for the total number of political executions go up to as many as 4,000. The vast majority of those executed directly following the 1959 Revolution were policemen, politicians, and informers of the Batista regime accused of crimes such as torture and murder, and their public trials and executions had widespread popular support among the Cuban population.

The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban Revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America. Castro's legalization of the Communist Party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen, and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries. The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations. In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S. In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.

In March 1960, U.S. President

The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban Revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America. Castro's legalization of the Communist Party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen, and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries. The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations. In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S. In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.

In March 1960, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

gave his approval to a CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

plan to arm and train a group of Cuban refugees to overthrow the Castro government. The invasion (known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fina ...

) took place on 14 April 1961, during the term of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

. About 1,400 Cuban exiles disembarked at the Bay of Pigs. Cuban troops and local militias defeated the invasion, killing over 100 invaders and taking the remainder prisoner. In January 1962, Cuba was suspended from the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

(OAS), and later the same year the OAS started to impose sanctions against Cuba of similar nature to the U.S. sanctions. The Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

of October 1962 almost sparked World War III

World War III or the Third World War, often abbreviated as WWIII or WW3, are names given to a hypothetical World war, worldwide large-scale military conflict subsequent to World War I and World War II. The term has been in use ...

. By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged communist system modeled on the USSR.

In 1963, Cuba sent 686 troops together with 22 tanks and other military equipment to support Algeria in the

In 1963, Cuba sent 686 troops together with 22 tanks and other military equipment to support Algeria in the Sand War

The Sand War or the Sands War () was a border conflict between Algeria and Morocco in October 1963. It resulted largely from the Moroccan government's claim to portions of Algeria's Tindouf and Béchar provinces. The Sand War led to heighten ...

against Morocco. In 1964, Cuba organized a meeting of Latin American communists in Havana and stoked a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in the capital of the Dominican Republic in 1965, which prompted the U.S. military to intervene there. Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

engaged in guerrilla activities in Africa and was killed in 1967 while attempting to start a revolution in Bolivia. During the 1970s, Fidel Castro dispatched tens of thousands of troops in support of Soviet-supported wars in Africa. He supported the MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wing, social d ...

in Angola (Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war was ...

) and Mengistu Haile Mariam

Mengistu Haile Mariam ( am, መንግሥቱ ኀይለ ማሪያም, pronunciation: ; born 21 May 1937) is an Ethiopian politician and former army officer who was the head of state of Ethiopia from 1977 to 1991 and General Secretary of the Wor ...

in Ethiopia (Ogaden War

The Ogaden War, or the Ethio-Somali War (, am, የኢትዮጵያ ሶማሊያ ጦርነት, ye’ītiyop’iya somalīya t’orineti), was a military conflict fought between Somalia and Ethiopia from July 1977 to March 1978 over the Ethiopi ...

)..

In November 1975, Cuba poured more than 65,000 troops and 400 Soviet-made tanks into Angola in one of the fastest military mobilizations in history. South Africa developed nuclear weapons due to the threat to its security posed by the presence of large numbers of Cuban troops in Angola. In 1976 and again in 1988 at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale was fought intermittently between 14 August 1987 and 23 March 1988, south and east of the town of Cuito Cuanavale, Angola, by the People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and advisors and soldie ...

, the Cubans alongside their MPLA allies defeated UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola ( pt, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, abbr. UNITA) is the second-largest political party in Angola. Founded in 1966, UNITA fought alongside the Popular Movement for ...

rebels and apartheid