Conestoga people on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were

English colonists seldom visited the upper Susquehanna during the early colonial period. When John Smith met the Susquehannock in 1608, they had a large town in the lower river valley at present-day

English colonists seldom visited the upper Susquehanna during the early colonial period. When John Smith met the Susquehannock in 1608, they had a large town in the lower river valley at present-day  During the early Dutch colonization of

During the early Dutch colonization of  In 1638, Swedish settlers established

In 1638, Swedish settlers established

File:Andaste6.jpg, Drawing of a Susquehannock ca. 1675

File:SusquehannockFort_sm.jpg, Susquehannock Fort ca. 1671, in present-day York County, Pennsylvania

A graphic novel, documentary, and teaching material, under the title ''Ghost River'', a project of the Library Company of Philadelphia and supported by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, addresses the Paxton massacres of 1763 and provides "interpreters and new bodies of evidence to highlight the Indigenous victims and their kin.""Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga." https://ghostriver.org/ Accessed April 21, 2022.

Lancaster County Indians: Annals of the Susquehannocks and Other Indian Tribes of the Susquehanna Territory from about the Year 1500 to 1763, the Date of Their Extinction. An Exhaustive and Interesting Series of Historical Papers Descriptive of Lancaster County's Indians

', Express Print Company (Princeton University reprint), 1909. *Guss, A.L.,

Early Indian history on the Susquehanna: Based on rare and original documents

', L.S. Hart printer (Harvard reprint), 1883. * *Illick, Joseph E. ''Colonial Pennsylvania: a History''. New York: Scribner & Sons, 1976. *Jennings, Francis, ''The Ambiguous Iroquois Empire'', New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1984, {{ISBN, 0-393-01719-2

*Kent, Barry C. ''Susquehanna's Indians''. Harrisburg: The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1984.

*Raber, Paul A. ''The Susquehannocks: New Perspectives on Settlement and Cultural Identity'',

Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019 - Excavations (Archaeology)

*{{Cite journal , last=Varga , first=Colin , date=Winter 2007 , title=Susquehannocks: Catholics in Seventeenth Century Pennsylvania , url=http://paheritage.wpengine.com/article/susquehannocks-catholics-in-seventeenth-century-pennsylvania/ , journal=Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine , volume=XXXIII , issue=1 , pages=6–15

*Wallace, Paul A. W. ''Indians in Pennsylvania''. 2nd ed. Harrisburg: The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1981.

*Witthoft, John, ''Susquehannock miscellany'', Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1959.

"Where are the Susquehannock?"

at The Susquehannock Fire Ring

by Lee Sultzman

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Conestoga

{{Native Americans in Maryland {{authority control Iroquoian peoples Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands Native American history of Maryland Native American history of New York (state) Native American history of Pennsylvania Native American history of West Virginia Chesapeake Bay Extinct Native American tribes Potomac River Native American tribes in Maryland Native American tribes in Pennsylvania Native American tribes in West Virginia Algonquian ethnonyms

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were

The Susquehannock people, also called the Conestoga by some English settlers or Andastes were Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

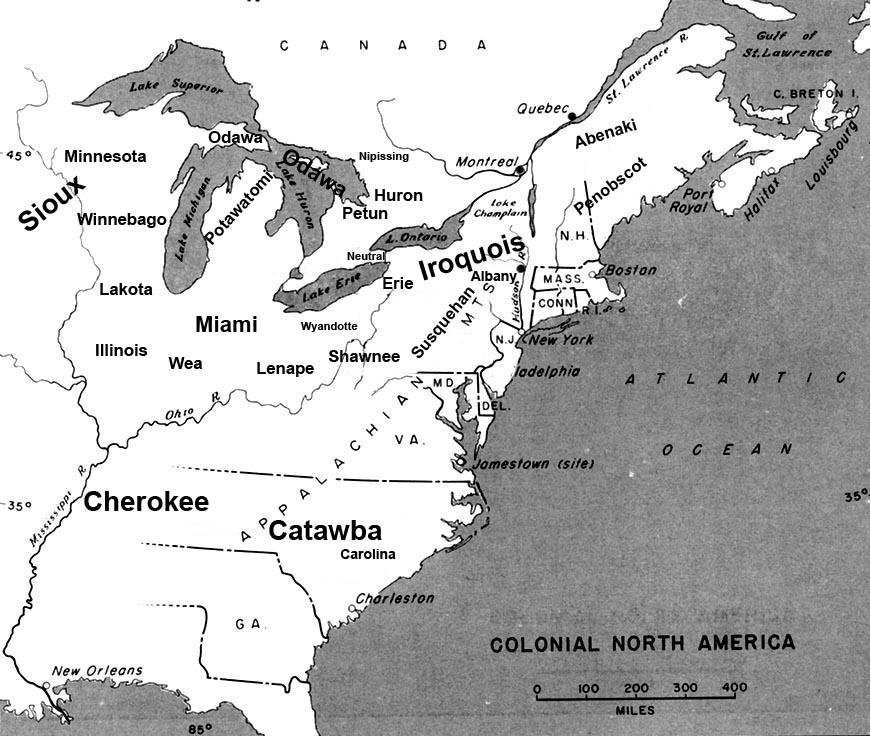

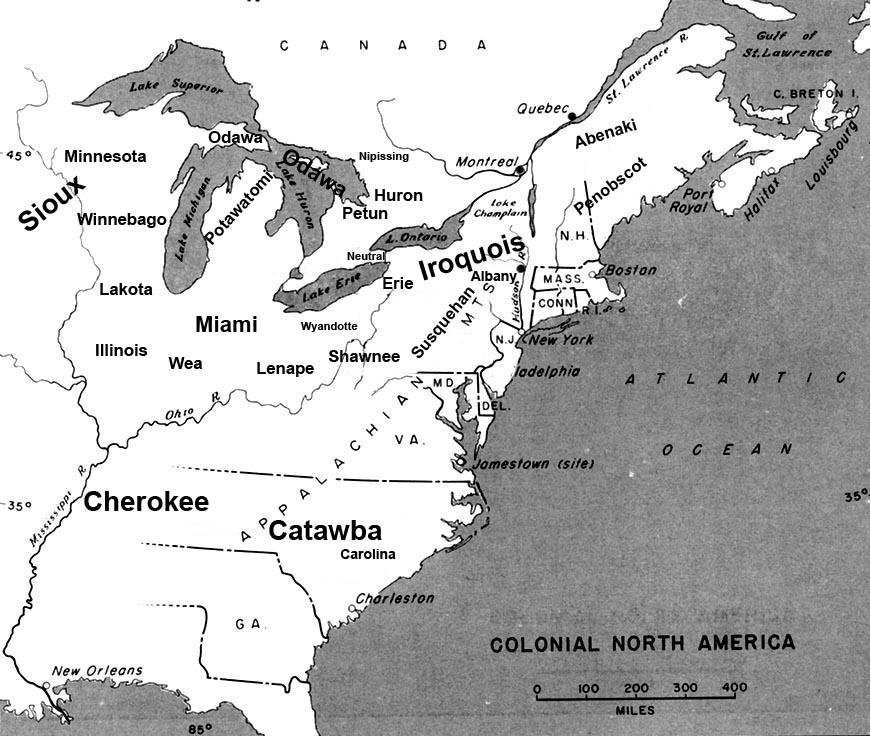

Native Americans who lived in areas adjacent to the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

and its tributaries

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drainage b ...

, ranging from its upper reaches in the southern part of what is now New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

(near the lands of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

), through eastern and central Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

west of the Poconos and the upper Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

(near the lands of the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

), with lands extending beyond the mouth of the Susquehanna in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

along the west bank of the Potomac at the north end of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

.

Evidence of their habitation has also been found in northern West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

and portions of southwestern Pennsylvania, which could be reached via the gaps of the Allegheny

The gaps of the Allegheny,

meaning gaps in the Allegheny Ridge (now given the technical name Allegheny Front) in west-central Pennsylvania, is a series of escarpment eroding water gaps (notches or small valleys) along the saddle between two ...

or several counties to the south, via the Cumberland Narrows

The Cumberland Narrows (or simply The Narrows) is a water gap in western Maryland in the United States, just west of Cumberland. Wills Creek cuts through the central ridge of the Wills Mountain Anticline at a low elevation here between Wills Mou ...

pass which held the Nemacolin Trail

450px, Braddock's Road, General Braddock's March (points 1–10) follows or parallels (and improves upon) Chief Nemacolin's Trail from the Potomac River to the Monogahela. The route from the summit to Redstone Creek, which could be used by wago ...

. Both passes abutted their range and could be reached through connecting valleys from the West Branch Susquehanna

The West Branch Susquehanna River is one of the two principal branches, along with the North Branch, of the Susquehanna River in the Northeastern United States. The North Branch, which rises in upstate New York, is generally regarded as the ex ...

and their large settlement at Conestoga, Pennsylvania

Conestoga is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Conestoga Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. At the 2010 census the population was 1,258. The Conestoga post office serves ZIP code 17516.

...

.

Language

The Susquehannock are anIroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

-speaking people. Little of the Susquehannock language has been preserved in published print. The chief source is a ''Vocabula Mahakuassica'' compiled by the Swedish missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

Johannes Campanius during the 1640s. Campanius' vocabulary contains about 100 words and is sufficient to show that Susquehannock is a Northern Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

language, closely related to those of the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

. The language of the Susquehannock appears to have been closely related to that of the Onondaga Nation

The Onondaga people (Onondaga: , ''Hill Place people'') are one of the original five constituent nations of the Iroquois (''Haudenosaunee'') Confederacy in northeast North America. Their traditional homeland is in and around present-day Onondaga ...

. It is considered extinct as of 1763, when the last survivors were killed at Conestoga by the Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were Pennsylvania's most aggressive colonists according to historian Kevin Kenny. While not many specifics are known about the individuals in the group their overall profile is clear. Paxton Boys Lived in hill country northwest of ...

. A couple were elsewhere and lived to natural deaths.

Names

The Europeans who explored the interior of the east coast of North America usually learned the names of the interiornations

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

from the coastal Algonquian-speaking peoples whom they first encountered. The Europeans adapted and transliterated these coastal exonyms

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, o ...

to fit their own languages and spelling systems, and tried to capture the sounds of the names. No Susquehannock endonyms

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, o ...

survive.

* The Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

, another Iroquoian-speaking people, called these people ''Andastoerrhonon'', meaning "people of the blackened ridge pole", related to their building practices. The French adapted the Huron term and called them ''Andaste'' or ''Gandastogue'' ("people of the blackened ridge pole").

* The Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

, an Algonquian-speaking people, referred to them by an exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

, ''Mengwe''. An anonymous Lenâpe-English dictionary published in 1888 said this literally means "glans penis". Wallace gives "treacherous" as the translation of Minquas. Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

colonists derived their term of ''Minquas'' for the people from this term.

* The Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

-speaking peoples of coastal Virginia (also Algonquian) called the tribe the ''Sasquesahanough.'' The English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

settlers in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

transliterated the Powhatan term, referring to the people as the ''Susquehannock.''

* In the late eighteenth century, British colonists in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

called them the Conestoga, derived from a remaining village known as Conestoga Town

Conestoga Town is an historic archaeological site memorializing the Native American tribal village which stood on the site from the late 17th into the mid-18th-century; it is located at what is now Manor Township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania ...

. Its name was based on the Iroquoian term, ''Kanastoge'', possibly meaning "place of the upright pole." Early English and Dutch traders heard and spelled the people's main settlement, fort, or castle, as "Quanestaqua."

History

Before European contact

According to Minderhout, around 1450 the Susquehannock were living on the North Branch of the Susquehanna River. They moved downriver to present-day Lancaster County by 1525, where they lived in denser villages. The Susquehannock told Europeans that they originally came from a large river valley to the west. Europeans who wrote this down seemed to assume that the Mississippi River was meant, although no Iroquoian people have ever been found in the archaeological records of the region. Iroquoian peoples were, however, believed to have held a much larger region of Ohio at some point between the 13th and 16th centuries, when European colonization began. The Susquehannock also, however, claimed to have joined with other peoples once east of the Appalachian Mountains to form their nation. It is most likely that both are correct. Modern estimates of the total Susquehannock population in 1600 range as high as 7,000 people. During the sixteenth century and carrying forward into the first decades of colonization, the Susquehannock were the most numerous people in what is now called the Susquehanna Valley. It is likely that the Susquehannock had occupied the same lands for several thousand years.European Contact

English colonists seldom visited the upper Susquehanna during the early colonial period. When John Smith met the Susquehannock in 1608, they had a large town in the lower river valley at present-day

English colonists seldom visited the upper Susquehanna during the early colonial period. When John Smith met the Susquehannock in 1608, they had a large town in the lower river valley at present-day Washington Boro, Pennsylvania

Washington Boro is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Manor Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States, along the Susquehanna River. The ZIP code is 17582. It is served by the Penn Manor School Distri ...

. Smith wrote of the Susquehannock,

"They can make neere 600 able and mighty men, and are pallisadoed alisadedin their Townes to defend them from the Massawomekes, their mortal enemies." He was astonished to find the Susquehannock were brokering trade with French goods. He estimated the population of their village to be 2,000, although he never visited it.

Similar to the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

, or Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, the Susquehannock consisted of several distinct tribes. Capital towns were named by John Smith as:

* Sasquesahanough (on the east side of the Susquehanna near Conewago Falls),

* Attaock (on the west side of the Susquehanna likely in present-day York County, Pennsylvania

York County ( Pennsylvania Dutch: Yarrick Kaundi) is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 456,438. Its county seat is York. The county was created on August 19, 1749, from part of Lancaster ...

),

* Quadroque (in present-day Northumberland County, Pennsylvania

Northumberland County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is part of Northeastern Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 91,647. Its county seat is Sunbury.

The county was formed in 1772 from parts of Lancas ...

),

* Tesinigh (on the east bank of the Susquehanna in present-day Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County (; Pennsylvania Dutch: Lengeschder Kaundi), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is located in the south central part of Pennsylvania. ...

),

* Utchowig, and

* Cepowig (likely in present-day York County, Pennsylvania "on the east side of the main stream of Willowbye's river").

The French explorer Samuel Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fr ...

noted the Susquehannock in his ''Voyages of Samuel Champlain''. Writing of a 1615 incident, he described a Susquehannock town, Carantouan, as "provided with more than eight hundred warriors, and strongly fortified, . . . ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

high and strong palisades well bound and joined together, the quarters being constructed in a similar fashion." Carantouan was located on the upper Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

near present-day Waverly, Tioga County, New York

Waverly is the largest village in Tioga County, New York, United States. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Waverly had a population of 4,177. It is located southeast of Elmira in the Southern Tier region. This village was incorporated as t ...

. Spanish Hill

Spanish Hill is a hill located in the borough of South Waverly, Pennsylvania. Opinions regarding the origin of structures found on the site vary from embankments created by early farmers, to the remnants of a Native American village and battlem ...

may be the former site of Carantouan.

Estimates of the historic population of the Susquehannock are uncertain due to their lack of contact with the Europeans. The Europeans' best guesses were that the tribe numbered from 5,000 to 7,000 in 1600, and that the Susquehannock were a regional power capable of holding off the Haudenosaunee in the first seven decades of the 17th century, including after the Haudenosaunee began systematic warfare against neighboring ethnic groups to gain territory and power (including firearms) in fur trading. Before that time, the inland Susquehannock had allied with Dutch and Swedish traders (1600 & 1610) and Swedish settlers in New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

around 1640 who had a monopoly on European flintlock

Flintlock is a general term for any firearm that uses a flint-striking lock (firearm), ignition mechanism, the first of which appeared in Western Europe in the early 16th century. The term may also apply to a particular form of the mechanism its ...

firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes c ...

, increasing the tribe's power. They did not supply such firearms to the Haudenosaunee or the Lenape after the English defeated the Dutchand took over New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

in 1667, they gradually incorporated the Atlantic Seaboard, from New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

to Georgia, into the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

(see Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between Kingdom of England, England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas a ...

) Because British traders had established relationships with the Haudenosaunee, they refused to sell firearms to the Lenape, who occupied a broad band of territory along the mid-Atlantic coast.

Prior to 1640, the Susquehannock may have defeated bands of the Lenape in the greater central Delaware Valley region, and made raids across the Delaware River into what is now central New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. Following a war with the fierce Susquehannock before 1640, the Lenape became a tributary nation to them.

The Susquehannock (whose population had been greatly reduced by the time the British tried to assert any significant control over the Susquehannock homeland) had early on allied with the Swedes, who traded Dutch firearms for Susquehannock furs as early as the 1610s. At this point in time, the Susquehannock were generally opposed to the policies of the new European managers of the colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania. Consequently, the Susquehannock defended themselves from attack in a war declared by the Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland ...

from 1642 to the 1650s and won it, with help from their Swedish allies.

During the mid-17th century, the Susquehannock found that the English fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

rs would trade European firearms in exchange for beaver skins. Due to the trade deals that the Susquehannock were getting from the English fur traders, the Haudenosaunee began warring against other Nations in the region in order to monopolize the richest fur- bearing streams. When the Haudenosaunee attempted to impose their will upon the Susquehannock circa 1666, the Susquehannock achieved a great victory against the combined forces of the Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

and Cayuga Cayuga often refers to:

* Cayuga people, a native tribe to North America, part of the Iroquois Confederacy

* Cayuga language, the language of the Cayuga

Cayuga may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Cayuga, Ontario

United States

* Cayuga, Illinois ...

nations, severely damaging the southern populations of both these western Iroquois nations.

Susquehannock authority reached a zenith in the early 1670s, after which they suffered an extremely rapid population and authority decline in the mid-1670s, - presumably from infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. These also decimated other Native American groups such as the Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

*Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

*Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been t ...

and other Iroquoian-speaking nations. By 1678, drastically weakened by their losses, the Susquehannock were overwhelmed by the Haudenosaunee. Some small groups are believed to have fled west via the gaps of the Allegheny

The gaps of the Allegheny,

meaning gaps in the Allegheny Ridge (now given the technical name Allegheny Front) in west-central Pennsylvania, is a series of escarpment eroding water gaps (notches or small valleys) along the saddle between two ...

into land beyond most European influence in the Ohio Country. Some likely were absorbed by the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

.

New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

, the Susquehannock traded furs with the Europeans. As early as 1623, they struggled to go north past the Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

, who occupied territory along the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

, to trade with the Dutch at New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

. In 1634, the Susquehannock defeated the Lenape in that area, who may have become their tributaries

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drainage b ...

.

In 1638, Swedish settlers established

In 1638, Swedish settlers established New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden form ...

in the Delaware Valley

The Delaware Valley is a metropolitan region on the East Coast of the United States that comprises and surrounds Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city in the nation and 68th largest city in the world as of 2020. The toponym Delaware Val ...

near the coast. Their location near the bay enabled them to interrupt the Susquehannock fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

with the Dutch further north along the coast.

In 1642, the English colony of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryla ...

declared war on the Susquehannock. With the help of Swedish colonists, the Susquehannock defeated the colony of Maryland in 1644. Maryland was in an intermittent state of war with the Susquehannock until 1652. As a result, the Susquehannock traded almost exclusively with New Sweden to the north.

Alliance with Maryland, 1651–1674

In 1652, six chiefs of the Susquehannock concluded a peace treaty with Maryland. In return for arms and safety on their southern flank, they ceded to Maryland large territories on both shores of theChesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. This decision was also related to the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

of the late 1650s, in which the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

swept south and west against other tribes and territories to expand their hunting grounds for the fur trade. With the help of Maryland's arms, the Susquehannock fought off the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

Confederacy for a time, and a brief peace followed.

In 1658, the Susquehannock used their influence with the Esopus to end the Esopus Wars

The Esopus Wars were two conflicts between the Esopus tribe of Lenape Indians (Delaware) and New Netherlander colonists during the latter half of the 17th century in Ulster County, New York. The first battle was instigated by settlers; the second ...

, because that conflict interfered with important Susquehannock-Dutch trade relations. From 1658 to 1662, the Susquehannock were at war with the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy (based south of the Great Lakes) which was seeking new hunting grounds for the fur trade. By 1661, Maryland colonists and the Susquehannock had expanded their peace treaty into a full alliance against the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Fifty English colonists were assigned to the Susquehannock to guard their fort.

In 1663, the Susquehannock defeated a large Haudenosaunee Confederacy invasion force. In April 1663, the Susquehannock village on the upper Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

was attacked by Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, Cayuga Cayuga often refers to:

* Cayuga people, a native tribe to North America, part of the Iroquois Confederacy

* Cayuga language, the language of the Cayuga

Cayuga may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Cayuga, Ontario

United States

* Cayuga, Illinois ...

, and Onondaga Onondaga may refer to:

Native American/First Nations

* Onondaga people, a Native American/First Nations people and one of the five founding nations of the Iroquois League

* Onondaga (village), Onondaga settlement and traditional Iroquois capita ...

warriors of the western Iroquois. (JR: 48:7-79, NYCD 12:431).

In 1669–70, John Lederer

John Lederer was a 17th-century German physician and an explorer of the Appalachian Mountains. He and the members of his party became the first Europeans to crest the Blue Ridge Mountains (1669) and the first to see the Shenandoah Valley and the ...

was possibly guided by a Susquehannock man on his journey to the southwest Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, though the Indian who travelled with him is never named.

Paul A. W. Wallace writes, "In 1669 Iroquois Indians warned the French that if they tried to descend the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

they would be in danger from the 'Andastes'."

In 1672, the Susquehannock defeated another Haudenosaunee Confederacy war party. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy appealed to the French colonial government for support because the Haudenosaunee Confederacy could not "defend themselves if the others came to attack them in their villages". Some old histories indicate that the Haudenosaunee Confederacy ultimately defeated the Susquehannock, but no record of a defeat has been found. In 1675 the Susquehannock suffered a major defeat by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. English colonists invited the tribe to resettle in the colony of Maryland, where they relocated. It needs to be noted that this territory was familiar to Susquehannock people because this part of the colony of Maryland was actually the Southern area of the Conestoga Homeland.

The Susquehannock suffered from getting caught up in Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Colony of Virginia, Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon (Virginia colonist), Nathaniel Bacon against List of colonial governors of Virginia, Colon ...

the following year. After some Doeg Indians killed some Virginians, surviving colonists crossed into the colony of Maryland and killed Susquehannock in retaliation. A group of Susquehannock moved to a site now known as Susquehannock Fort on Piscataway Creek, below present-day Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

. Problems on the frontiers led to the mobilization of the militias of the colony of Maryland and the colony of Virginia. In confusion, the colonial militias of Maryland and Virginia surrounded the peaceful Susquehannock village. When five Susquehannock Chiefs came out of their village to negotiate with the colonial militias of Maryland and Virginia, the colonial militias murdered the five Susquehannock Chiefs. The Susquehannock left their own village at night and harassed colonists in the colonies of Virginia and Maryland. The Susquehannock from this village eventually returned to the area of the Susquehanna River.

Covenant Chain Treaty

In 1676 the Haudenosaunee made peace with the colonies of Maryland and Virginia, and the Lenape. When the Susquehannock agreed to theCovenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties developed during the seventeenth century, primarily between the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) and the British colonies of North America, with other Native American tribes added. Fi ...

offered by the Haudenosaunee in 1679, they were offered shelter and many other benefits.

Around 1679, most of the remaining Susquehannock moved to New York, joining mostly with the Seneca and Onondaga nations, who also spoke Iroquoian languages. The Haudenosaunee had a long tradition of adopting defeated enemies into their tribes. Governor Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

of the colony/Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the Uni ...

told the Susquehannock that they would be welcome in the lands of the Haudenosaunee and protected from the colonies of Maryland and Virginia.

Some Susquehannock returned to their homeland on the southern shores of the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

, keeping their distance from the center of Iroquois territory. Others moved to the upper Delaware River into the somewhat depopulated Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

lands where they lived under the protection of the colony of New York.

The Iroquois took control over most of the territory along the Susquehanna River above the Fall Line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is typically prominent where rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the coa ...

. Some of the Susquehannock survivors merged with the Meherrin

The Meherrin Nation (autonym: Kauwets'a:ka, "People of the Water") is one of seven state-recognized nations of Native Americans in North Carolina. They reside in rural northeastern North Carolina, near the river of the same name on the Virgini ...

, and allied Nottoway or Mangoac, Iroquoian-speaking tribes located in what were then the colonies of Virginia and North Carolina. The new group called themselves "Chiroenhaka," according to the 20th-century ethnologist James Mooney

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man", he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Gr ...

.

Writing in 2009, Bryan Ward, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, said archeological "sites such as the Mouth of the Seneca (46Pd1) and Pancake Island (46Hm73) have produced evidence of Susquehannock movement into and habitation in the astern part of West Virginia

This list of ship directions provides succinct definitions for terms applying to spatial orientation in a marine environment or location on a vessel, such as ''fore'', ''aft'', ''astern'', ''aboard'', or ''topside''.

Terms

* Abaft (preposition ...

"

The Susquehannock negotiated a treaty with English colonists to enable their settlement in the Conestoga homeland. The Susquehannock chiefs never ceded these lands to Europeans or Americans. According to the Covenant Chain, the Susquehannock were prevented from making any such treaty of cession.

Conestoga Town

The Susquehannock population in theirSusquehanna Valley

The Susquehanna Valley is a region of low-lying land that borders the Susquehanna River in the United States, U.S. states of New York (state), New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The valley consists of areas that lie along the main branch o ...

homeland may have declined to as few as about 300 counted persons in 1700. Another remnant group lived to the west in the Allegheny settlement near what is now Conestoga, Pennsylvania

Conestoga is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Conestoga Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. At the 2010 census the population was 1,258. The Conestoga post office serves ZIP code 17516.

...

; the English colonists called them the Conestoga people.

The Conestoga population had been devastated by high fatalities from new Eurasian infectious diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, to which they had no immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

, followed by warfare. About 1697, a few hundred Conestoga people settled in a new village called Conestoga Town

Conestoga Town is an historic archaeological site memorializing the Native American tribal village which stood on the site from the late 17th into the mid-18th-century; it is located at what is now Manor Township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania ...

in what is now known as Lancaster County, Pennsylvania

Lancaster County (; Pennsylvania Dutch: Lengeschder Kaundi), sometimes nicknamed the Garden Spot of America or Pennsylvania Dutch Country, is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. It is located in the south central part of Pennsylvania. ...

. The river was at that point named the Conestoga River

The Conestoga River, also referred to as Conestoga Creek, is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed August 8, 2011 tributary of the Susquehanna River flowing through the cente ...

under the colonial governor of the colony of Pennsylvania, Governor William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

. A type of wagon was named the Conestoga wagon for them; it was later used by pioneers migrating west. Hardware kits for the wagons were made on the east side of the Allegheny Mountains. In the early 1700s, some Conestoga migrated to Ohio, where they merged with other tribes, becoming known as the Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

.

The Conestoga people at Conestoga Town lived under the protection of the provincial Pennsylvania government, but their population declined steadily. In 1763, a census counted twenty-two people in Conestoga Town. That year the Paxton Boys

The Paxton Boys were Pennsylvania's most aggressive colonists according to historian Kevin Kenny. While not many specifics are known about the individuals in the group their overall profile is clear. Paxton Boys Lived in hill country northwest of ...

, in response to Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

on the western side of the Allegheny Mountains, attacked Conestoga Town (which was located on the eastern side of the Allegheny Mountains and had nothing to do with Pontiac's war of resistance to European colonial encroachment). They killed six people.

The remaining Conestoga inhabitants of Conestoga Town were sheltered in a Lancaster workhouse by the colonial government of Pennsylvania. The colonial governor discouraged further violence, but two weeks later, the Paxton Boys raided the town and killed the 14 Conestoga people staying at the workhouse. The tribe and their language were considered extinct.

The last two known Conestoga from Conestoga Town, a couple named Michael and Mary, were sheltered from the massacre on a farm near Manheim, Pennsylvania

Manheim is a borough in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 5,064 at the 2020 census. The borough was named after Kerpen- Manheim, Germany.

History

Manheim was laid out by Henry William Stiegel in 1762 on a land ...

. After their natural deaths, they were buried on the property.

20th century

In 1941 a bill was introduced by Ray E. Taylor and William E. Habbyshaw to provide a reservation for the remaining Susquehannock in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. It made arrangements for tribal members to lease land for a nominal fee and establish a central community in their historic homelands. Under the provisions of the bill, the tract of land would have been called "The Susquehannock Indian Reservation". While this appropriation bill for $20,000 was passed unopposed in the state legislature, it would be later vetoed by Governer Arthur James, who believed the last Susquehannock tribal member had died 168 earlier.21st century

Descendants of partial Susquehannock ancestry "may be included among today's Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma."Society

The Susquehannock society was a confederacy of up to 20 smaller tribes, who occupied scattered villages along the Susquehanna River. They likely hadclan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

s, as did other Iroquoian-speaking tribes, as the basis for their societies, and were a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's Lineage (anthropology), lineage – and which can in ...

kinship culture. Children were considered born to the mother's family and gained social status from her clan. Property and inherited positions passed through her line.

The Susquehannock remained independent and not part of any other confederacy into the 1670s. Ultimately, they were not strong enough to withstand the competition from colonists and other nations in their piece of the so-called Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

of that century. About 1677 many Susquehannock people, decimated by new infectious diseases and warfare, assimilated with their former enemies, the Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

(Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

), who were also Iroquoian speaking. They primarily occupied territory south of the Great Lakes in what is now New York State. In effect, the Haudenosaunee became the successor government to the Susquehannock. They took over the latter's territory.

Susquehannock people lived in longhouses as did the Haudenosaunee. The Susquehannock villages were palisaded so that enemies could not easily attack the village longhouses. Corn was such an important crop that John Campanius Holm recorded the Susquehannock word for it. The Susquehannock kept dogs, as indicated by Holm's record. Other important animals for the Susquehannock were turkey, deer, bear, beaver, otter, foxes, and elk. As is seen in the depiction of the Susquehannock man above, men went to war with bows and arrows, and war clubs. The vocabulary written by Holm includes words specifically meaning "smoking tobacco", as well as the word for "pipe for smoking tobacco". These indicate that tobacco smoking was an important part of Susquehannock ritual. The cut of the hair of the Susquehannock man pictured shows a hairstyle similar but different from that of the Haudenosaunee.

Travel was both on water and on land. On the water, it was via canoe. Several place names indicate locations where a portage was needed between river or stream sections. The main thoroughfare would have been what is today called the Susquehanna River. The length and navigability of this river via canoe would have allowed the Susquehannock to be a powerful regional force and to have strong internal trade routes between sub-tribes and clans. The Susquehanna River is navigable by canoe from near its source in what is now New York to its mouth in the Chesapeake Bay. The location of the Conestoga Homeland indicates that the Susquehannock language likely contained words for mountains, river features, land animals, plants, fish, coastal species, as well as for the land that was flat. The Pennsylvania Bison was likely hunted by the Susquehannock. Breaks in the mountain range would have allowed for over-land travel via well-worn trails. Most travel would likely have been inside of the valleys between the ridges. This would have meant that the Susquehannock had access to trade from what is now the Southeast of the United States via the valley systems. This would mean that the Susquehannock could have traded with the Cherokee directly since the Cherokee were directly South of the Conestoga Homeland. The Cherokee are another Iroquoian people and it is possible that the languages were not hard for one or the other Nation to learn.

Susquehannock society would have been affected and defined by its location. When viewed in a pre-Colonial context, the homelands of the Nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy are directly to the North of the Conestoga Homeland. To the South in the Appalachian mountain and valley ranges were the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, another Iroquoian-speaking people.

Susquehannock villages were likely traditionally built on top of ridges of the Appalachian Mountains when such ridges were available. The Susquehannock site in what is now Sayre, Pennsylvania is evidence for this. At this site was likely a religious complex, known currently as Spanish Hill. Spanish Hill is possibly an artificial hill, and possibly natural. Research is still being conducted regarding this issue. Building on the ridges would have allowed the Susquehannock to view from the safety of their villages the surrounding area, which was likely used for farming of corn, beans, and squash. This pattern of using the land near the rivers and streams for farming has been found in many Native American societies in the East of Turtle Island (North America). Building villages on ridge tops would have allowed the Susquehannock to observe advancing enemy movements and to be safe in times of flood. The Susquehannock lived in settled villages and were not known to be nomadic. The Conestoga Homeland is the most flood-prone area of the East of Turtle Island, owing to the number of rivers and their tributaries. The Susquehannock likely practiced sylvan agriculture like the other Native Nations of the East of Turtle Island. Nuts and berries would have been harvested from the forest and mushrooms would probably have been harvested as well. Harvest time for many berries and nuts can be ascertained from the current wild availability of the berries and nuts in the Conestoga Homeland. Harvest time for corn, beans, and squash was likely late Summer until early Fall. Following the normal seasonal festival/religious patterns of other Iroquois people, the Susquehannock most likely followed a seasonal calendar of planting, harvest, and Winter festivals.

Dreams were likely important to Susquehannock people. All other Iroquoian peoples put great stock in dreams and the Susquehannock are likely to have thought dreams to be important too.

Archeological materials have been found in Pennsylvania and Maryland's Allegany County at the Barton (18AG3) and Llewellyn (18AG26) sites. West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

's Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

and Hardy counties region (Brashler 1987) also have archaeological sites where Susquehannock ceramics have been found.

Archeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

have also found evidence of Susquehannock people along the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

and its tributaries. They have classified these artifacts as the "late Susquehannock sequence". A Contact Period (1550~1630) Susquehanna site, (46Hy89), is located in the Eastern Panhandle

The Eastern Panhandle is the eastern of the two panhandles in the U.S. state of West Virginia; the other is the Northern Panhandle. It is a small stretch of territory in the northeast of the state, bordering Maryland and Virginia. Some sources a ...

at Moorefield, West Virginia

Moorefield is a town and the county seat of Hardy County, West Virginia, United States. It is located at the confluence of the South Branch Potomac River and the South Fork South Branch Potomac River. Moorefield was originally chartered in 1777; ...

.

Legacy

Places have been named for the historic tribe: *Susquehannock State Park in Pennsylvania *Susquehannock High School

Susquehannock High School is a mid-sized suburban public high school in Glen Rock, Pennsylvania. It is the sole high school operated by the Southern York County School District. In 2014, enrollment was reported as 946 pupils in 9th through 12th gr ...

of Southern York, Pennsylvania.

*Toponyms of the Conestoga homeland reflect place names from the Susquehannock/Conestoga language.

Iroquoian Peoples

* Susquehannock **Akhrakouaeronon

The Akhrakouaeronon or Atrakouaehronon were a subtribe of the Susquehannock. They lived in present-day Northumberland County, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state s ...

* Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

* Chonnonton

* Erie

Erie (; ) is a city on the south shore of Lake Erie and the county seat of Erie County, Pennsylvania, United States. Erie is the fifth largest city in Pennsylvania and the largest city in Northwestern Pennsylvania with a population of 94,831 a ...

* Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

* Haudenosaunee Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

/Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

* Meherrin

The Meherrin Nation (autonym: Kauwets'a:ka, "People of the Water") is one of seven state-recognized nations of Native Americans in North Carolina. They reside in rural northeastern North Carolina, near the river of the same name on the Virgini ...

* Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

*Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

*Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been t ...

* Petun

The Petun (from french: pétun), also known as the Tobacco people or Tionontati ("People Among the Hills/Mountains"), were an indigenous Iroquoian people of the woodlands of eastern North America. Their last known traditional homeland was sout ...

(See also Protohistory of West Virginia

The protohistory, protohistoric period of the state of West Virginia in the United States began in the mid-sixteenth century with the arrival of European trade goods. Explorers and colonists brought these goods to the eastern and southern coas ...

)

* Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

(Also Nottoway )

Important Treaties

Covenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties developed during the seventeenth century, primarily between the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) and the British colonies of North America, with other Native American tribes added. Fi ...

Footnotes

References

*Brinton, Daniel G. and the Rev. Albert S. Anthony. ''Lenâpe-English Dictionary. From an Anonymous MS. in the Archives of the Moravian Church at Bethlehem, PA''. Philadelphia, PA: The Historical Society of PA, 1888. *Eshleman, H.F.,Lancaster County Indians: Annals of the Susquehannocks and Other Indian Tribes of the Susquehanna Territory from about the Year 1500 to 1763, the Date of Their Extinction. An Exhaustive and Interesting Series of Historical Papers Descriptive of Lancaster County's Indians

', Express Print Company (Princeton University reprint), 1909. *Guss, A.L.,

Early Indian history on the Susquehanna: Based on rare and original documents

', L.S. Hart printer (Harvard reprint), 1883. * *Illick, Joseph E. ''Colonial Pennsylvania: a History''. New York: Scribner & Sons, 1976. *Jennings, Francis, ''The Ambiguous Iroquois Empire''

External links

{{Portal, United States *{{commons category-inline"Where are the Susquehannock?"

at The Susquehannock Fire Ring

by Lee Sultzman

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture - Conestoga

{{Native Americans in Maryland {{authority control Iroquoian peoples Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands Native American history of Maryland Native American history of New York (state) Native American history of Pennsylvania Native American history of West Virginia Chesapeake Bay Extinct Native American tribes Potomac River Native American tribes in Maryland Native American tribes in Pennsylvania Native American tribes in West Virginia Algonquian ethnonyms