The history of science covers the development of

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

from

ancient times

Ancient history is a time period from the History of writing, beginning of writing and recorded human history through late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the development of Sumerian language, ...

to the

present

The present is the period of time that is occurring now. The present is contrasted with the past, the period of time that has already occurred; and the future, the period of time that has yet to occur.

It is sometimes represented as a hyperplan ...

. It encompasses all three major

branches of science

The branches of science, also referred to as sciences, scientific fields or scientific disciplines, are commonly divided into three major groups:

* Formal sciences: the study of formal systems, such as those under the branches of logic and mat ...

:

natural

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

,

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

, and

formal

Formal, formality, informal or informality imply the complying with, or not complying with, some set of requirements ( forms, in Ancient Greek). They may refer to:

Dress code and events

* Formal wear, attire for formal events

* Semi-formal atti ...

.

Protoscience

In the philosophy of science, protoscience is a research field that has the characteristics of an undeveloped science that may ultimately develop into an established science. Philosophers use protoscience to understand the history of science and d ...

,

early sciences, and natural philosophies such as

alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

and

astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

that existed during the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

,

Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

,

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

and the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, declined during the

early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

after the establishment of formal disciplines of

science in the Age of Enlightenment

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in science and technology during the Age of Enlightenment, Age of Reason, when Enlightenment ideas and ideals were being disseminated across Europe and North America. Gene ...

.

The earliest roots of scientific thinking and practice can be traced to

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

and

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

during the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE.

These civilizations' contributions to

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

,

astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, and

medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

influenced later Greek

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the

physical world

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

based on natural causes.

After the

fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

, knowledge of

Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of

the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

,

but continued to thrive in the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

-speaking

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the

Hellenistic

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

worldview was preserved and absorbed into the

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

-speaking

Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

during the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

.

The recovery and assimilation of

Greek works and

Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West.

Traditions of early science were also developed in

ancient India

Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentism, Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE; ...

and separately in

ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, the

Chinese model having influenced

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

,

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

and

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

before

Western exploration. Among the

Pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

peoples of

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El S ...

, the

Zapotec civilization

The Zapotec civilization ( "The People"; 700 BC–1521 AD) is an Indigenous peoples, indigenous Pre-Columbian era, pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence shows that their cultu ...

established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for

producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the

Maya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

.

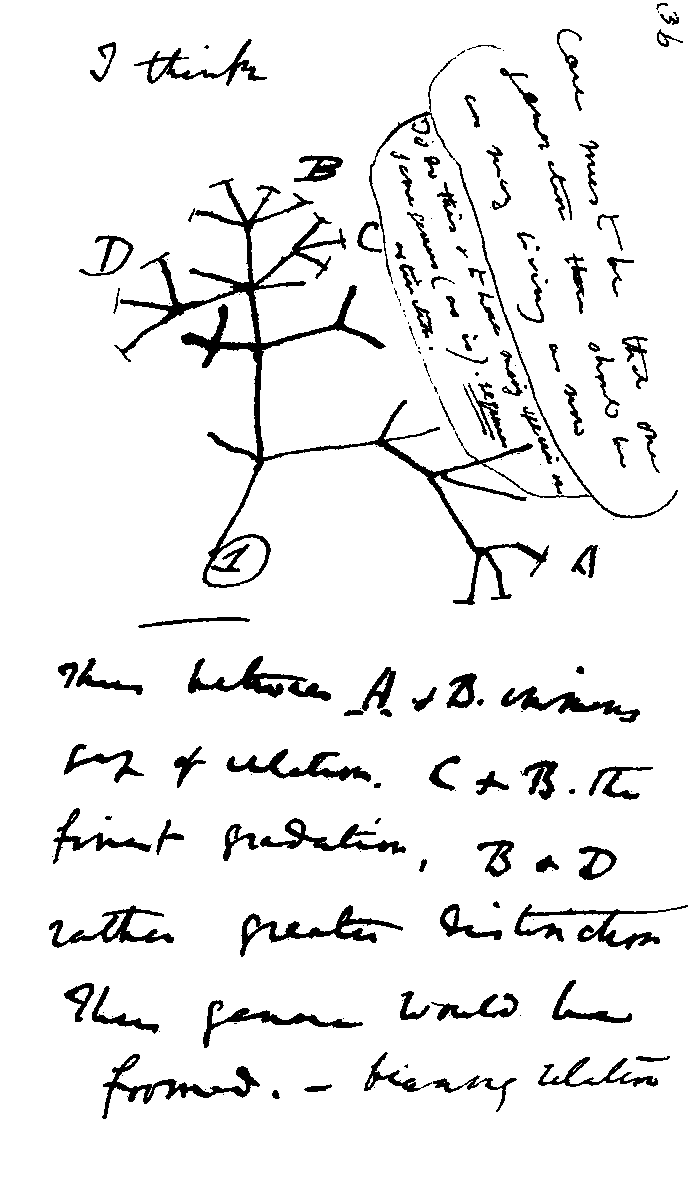

Natural philosophy was transformed by the

Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

that transpired during the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe,

as

new ideas and discoveries departed from

previous Greek conceptions and traditions.

The New Science that emerged was more

mechanistic

Mechanism is the belief that natural wholes (principally living things) are similar to complicated machines or artifacts, composed of parts lacking any intrinsic relationship to each other.

The doctrine of mechanism in philosophy comes in two diff ...

in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined

scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

.

More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The

chemical revolution

In the history of chemistry, the chemical revolution, also called the ''first chemical revolution'', was the reformulation of chemistry during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which culminated in the law of conservation of mass and the ...

of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

.

In the

19th century

The 19th century began on 1 January 1801 (represented by the Roman numerals MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 (MCM). It was the 9th century of the 2nd millennium. It was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was Abolitionism, ...

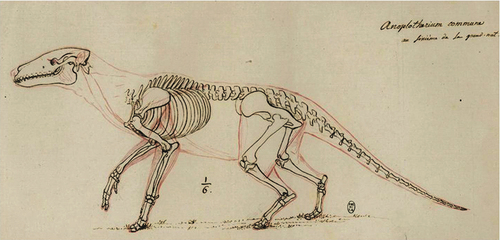

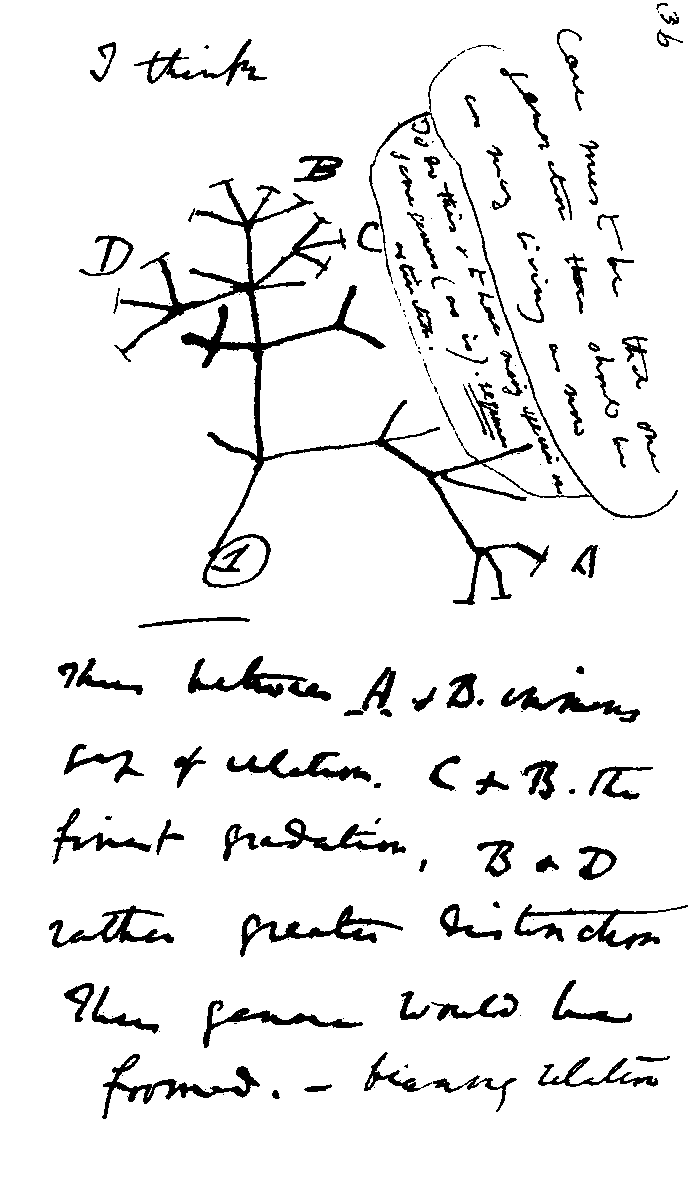

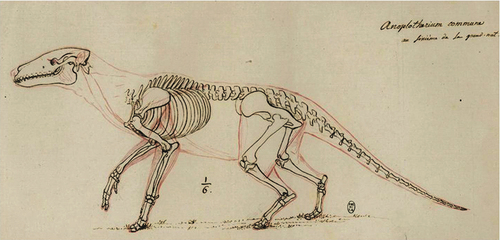

, new perspectives regarding the

conservation of energy

The law of conservation of energy states that the total energy of an isolated system remains constant; it is said to be Conservation law, ''conserved'' over time. In the case of a Closed system#In thermodynamics, closed system, the principle s ...

,

age of Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of ...

, and

evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

came into focus.

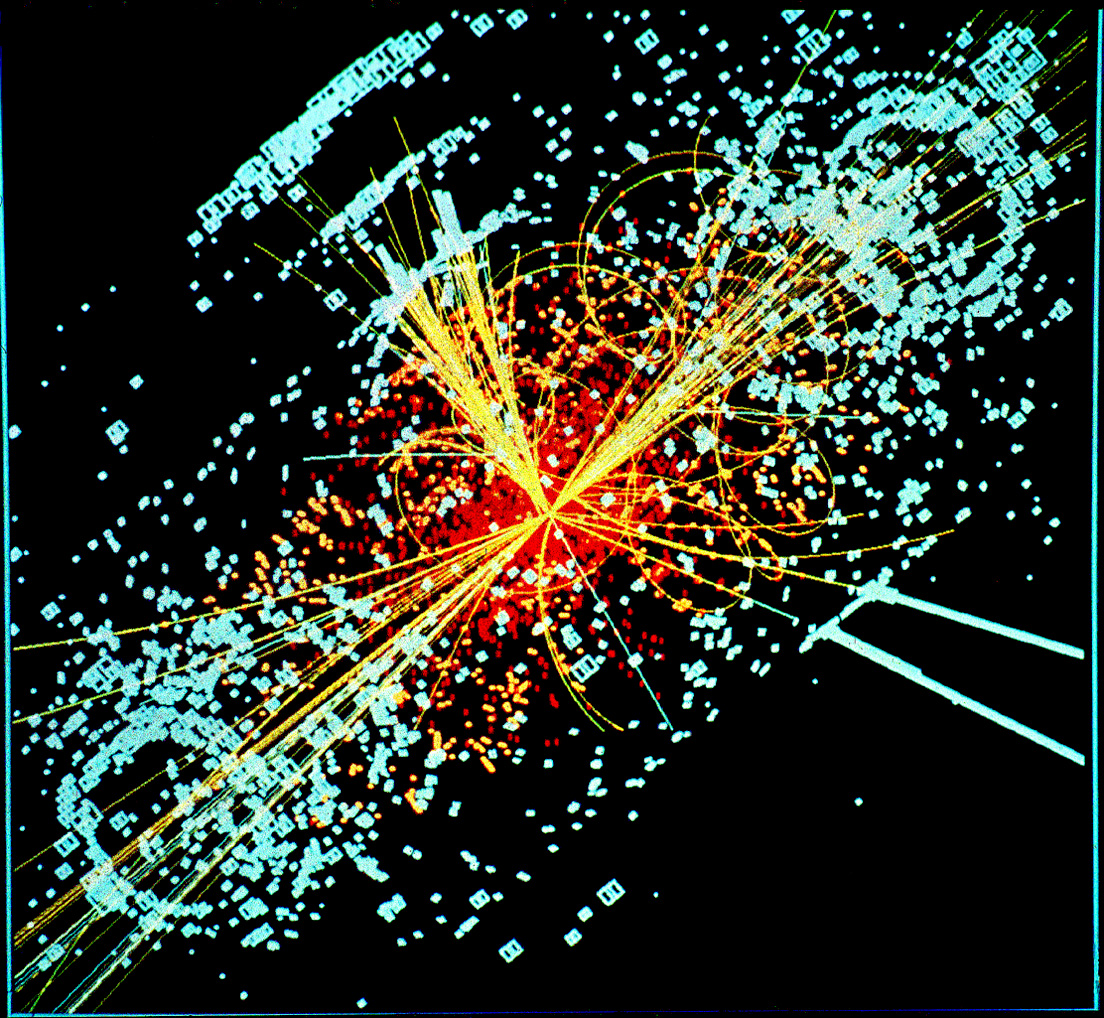

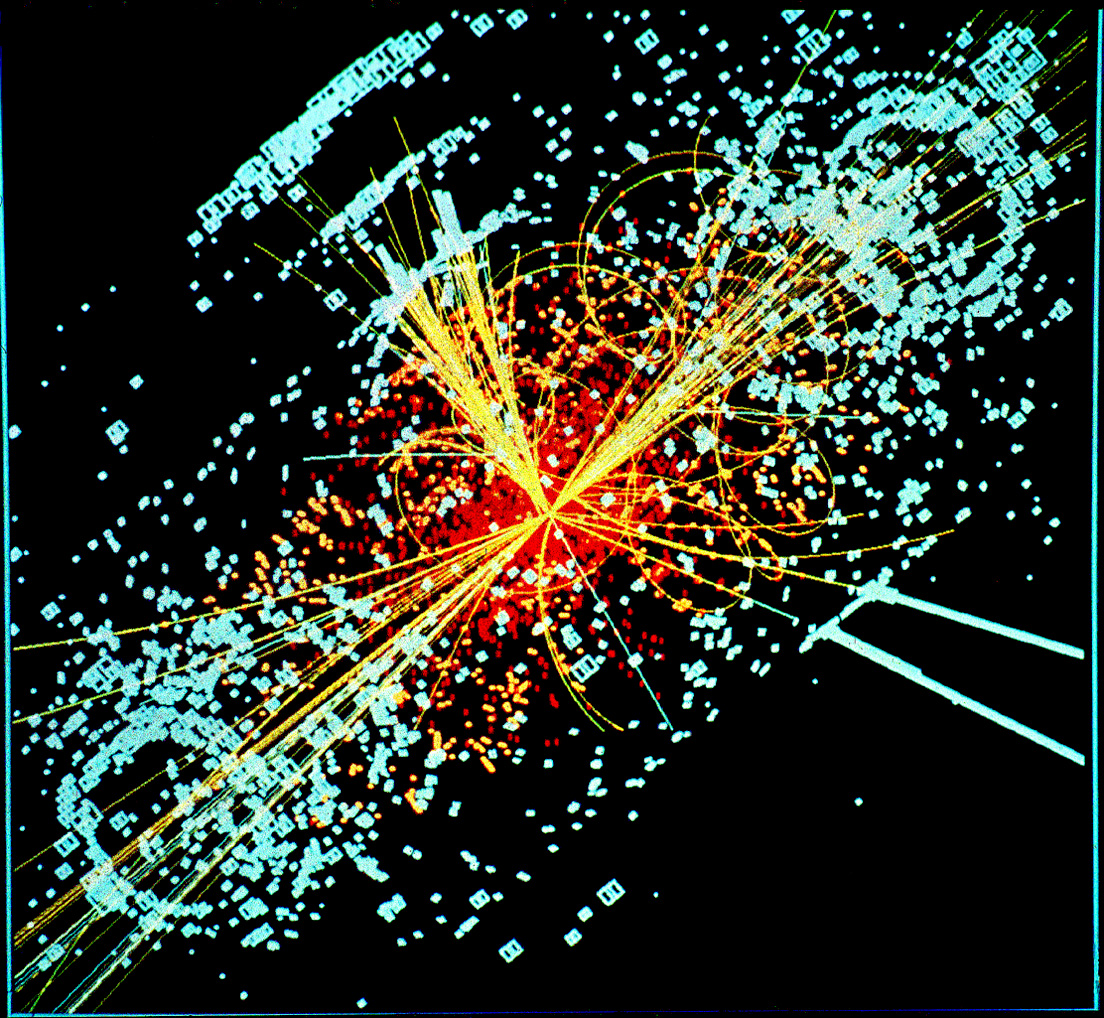

And in the 20th century, new discoveries in

genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

and

physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as

molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

and

particle physics

Particle physics or high-energy physics is the study of Elementary particle, fundamental particles and fundamental interaction, forces that constitute matter and radiation. The field also studies combinations of elementary particles up to the s ...

.

Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "

big science," particularly after

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

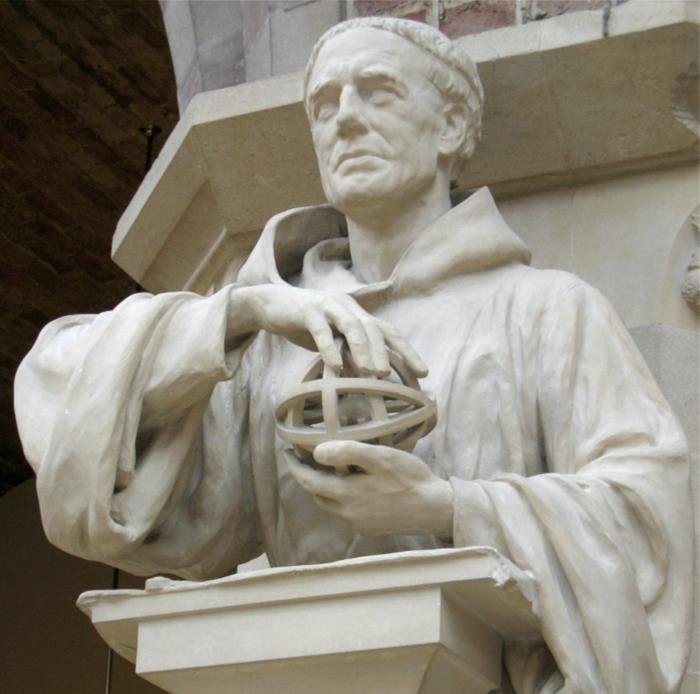

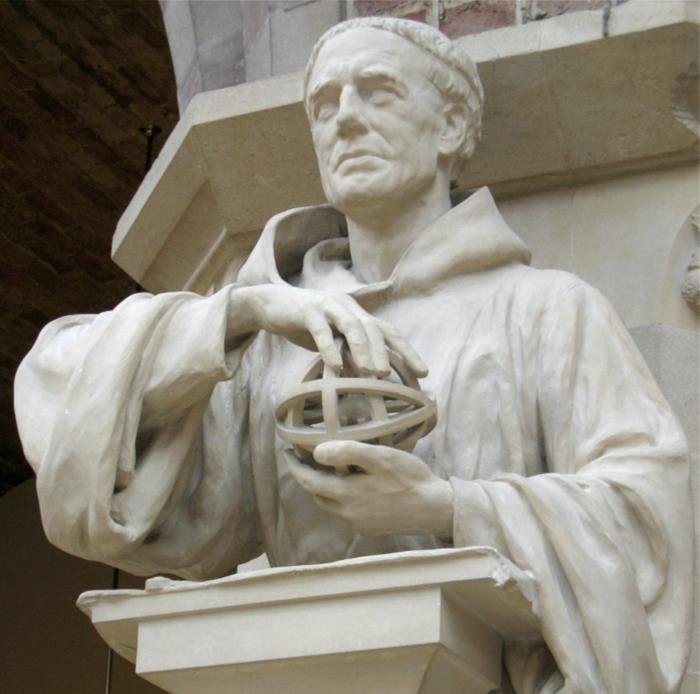

Approaches to history of science

The nature of the history of science is a topic of debate (as is, by implication, the definition of science itself). The history of science is often seen as a linear story of progress,

but historians have come to see the story as more complex.

Alfred Edward Taylor

Alfred Edward Taylor (22 December 1869 – 31 October 1945), usually cited as A. E. Taylor, was a British idealist philosopher most famous for his contributions to the philosophy of idealism in his writings on metaphysics, the philosophy ...

has characterised lean periods in the advance of scientific discovery as "periodical bankruptcies of science".

Science is a human activity, and scientific contributions have come from people from a wide range of different backgrounds and cultures. Historians of science increasingly see their field as part of a global history of exchange, conflict and collaboration.

The

relationship between science and religion has been variously characterized in terms of "conflict", "harmony", "complexity", and "mutual independence", among others. Events in Europe such as the

Galileo affair

The Galileo affair was an early 17th century political, religious, and scientific controversy regarding the astronomer Galileo Galilei's defence of heliocentrism, the idea that the Earth revolves around the Sun. It pitted supporters and opponent ...

of the early 17th century – associated with the scientific revolution and the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

– led scholars such as

John William Draper

John William Draper (May 5, 1811 – January 4, 1882) was an English polymath: a scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian and photographer. He is credited with pioneering portrait photography (1839–40) and producing the first deta ...

to postulate () a

conflict thesis

The conflict thesis is a historiographical approach in the history of science that originated in the 19th century with John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White. It maintains that there is an intrinsic intellectual conflict between religion an ...

, suggesting that religion and science have been in conflict methodologically, factually and politically throughout history. The "conflict thesis" has since lost favor among the majority of contemporary scientists and historians of science.

However, some contemporary philosophers and scientists, such as

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, zoologist, science communicator and author. He is an Oxford fellow, emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford, and was Simonyi Professor for the Publ ...

, still subscribe to this thesis.

Historians have emphasized that trust is necessary for agreement on claims about nature. In this light, the 1660 establishment of the

Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and its code of experiment – trustworthy because witnessed by its members – has become an

important chapter in the

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term ":wikt:historiography, historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiog ...

of science. Many people in modern history (typically

women

A woman is an adult female human. Before adulthood, a female child or adolescent is referred to as a girl.

Typically, women are of the female sex and inherit a pair of X chromosomes, one from each parent, and women with functional u ...

and persons of color) were excluded from elite scientific communities and

characterized by the science establishment as inferior. Historians in the 1980s and 1990s described the structural barriers to participation and began to recover the contributions of overlooked individuals. Historians have also investigated the mundane practices of science such as fieldwork and specimen collection, correspondence, drawing, record-keeping, and the use of laboratory and field equipment.

Prehistory

In

prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

times, knowledge and technique were passed from generation to generation in an

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

. For instance, the domestication of

maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

for agriculture has been dated to about 9,000 years ago in southern

Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, before the development of

writing system

A writing system comprises a set of symbols, called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. The earliest writing appeared during the late 4th millennium BC. Throughout history, each independen ...

s. Similarly,

archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

evidence indicates the development of

astronomical

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest include ...

knowledge in preliterate societies.

The oral tradition of preliterate societies had several features, the first of which was its fluidity.

New information was constantly absorbed and adjusted to new circumstances or community needs. There were no archives or reports. This fluidity was closely related to the practical need to explain and justify a present state of affairs.

Another feature was the tendency to describe the universe as just sky and earth, with a potential

underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

. They were also prone to identify causes with beginnings, thereby providing a historical origin with an explanation. There was also a reliance on a "

medicine man

A medicine man (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwinini'') or medicine woman (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwininiikwe'') is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Each culture has its own name i ...

" or "

wise woman" for healing, knowledge of divine or demonic causes of diseases, and in more extreme cases, for rituals such as

exorcism

Exorcism () is the religious or spiritual practice of evicting demons, jinns, or other malevolent spiritual entities from a person, or an area, that is believed to be possessed. Depending on the spiritual beliefs of the exorcist, this may be do ...

,

divination

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

, songs, and

incantation

An incantation, spell, charm, enchantment, or bewitchery is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung, or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial ri ...

s.

Finally, there was an inclination to unquestioningly accept explanations that might be deemed implausible in more modern times while at the same time not being aware that such credulous behaviors could have posed problems.

The development of writing enabled humans to store and communicate knowledge across generations with much greater accuracy. Its invention was a prerequisite for the development of philosophy and later

science in ancient times.

Moreover, the extent to which philosophy and science would flourish in ancient times depended on the efficiency of a writing system (e.g., use of alphabets).

Ancient Near East

The earliest roots of science can be traced to the

Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

in particular to

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

and

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

.

Ancient Egypt

Number system and geometry

Starting , the ancient Egyptians developed a numbering system that was decimal in character and had oriented their knowledge of geometry to solving practical problems such as those of surveyors and builders.

Their development of

geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

was itself a necessary development of

surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the land, terrestrial Plane (mathematics), two-dimensional or Three-dimensional space#In Euclidean geometry, three-dimensional positions of Point (geom ...

to preserve the layout and ownership of farmland, which was flooded annually by the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

. The 3-4-5

right triangle

A right triangle or right-angled triangle, sometimes called an orthogonal triangle or rectangular triangle, is a triangle in which two sides are perpendicular, forming a right angle ( turn or 90 degrees).

The side opposite to the right angle i ...

and other rules of geometry were used to build rectilinear structures, and the post and lintel architecture of Egypt.

Disease and healing

Egypt was also a center of

alchemy

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

research for much of the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

. According to the

medical papyri

Egyptian medical papyri are ancient Egyptian texts written on papyrus which permit a glimpse at medical procedures and practices in ancient Egypt. These papyri give details on disease, diagnosis, and remedies of disease, which include herbal reme ...

(written ), the ancient Egyptians believed that disease was mainly caused by the invasion of bodies by evil forces or spirits.

Thus, in addition to

medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, therapies included prayer,

incantation

An incantation, spell, charm, enchantment, or bewitchery is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung, or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial ri ...

, and ritual.

The

Ebers Papyrus

The Ebers Papyrus, also known as Papyrus Ebers, is an Egyptian medical papyrus of herbal knowledge dating to (the late Second Intermediate Period or early New Kingdom). Among the oldest and most important medical papyri of Ancient Egypt, it ...

, written , contains medical recipes for treating diseases related to the eyes, mouth, skin, internal organs, and extremities, as well as abscesses, wounds, burns, ulcers, swollen glands, tumors, headaches, and bad breath. The

Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical manual, medical text, named after Edwin Smith (Egyptologist), Edwin Smith who bought it in 1862, and the oldest known surgical treatise on trauma (medicine), trauma.

This document, which ma ...

, written at about the same time, contains a surgical manual for treating wounds, fractures, and dislocations. The Egyptians believed that the effectiveness of their medicines depended on the preparation and administration under appropriate rituals.

Medical historians believe that ancient Egyptian pharmacology, for example, was largely ineffective.

Both the Ebers and Edwin Smith papyri applied the following components to the treatment of disease: examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, which display strong parallels to the basic

empirical method

Empirical research is research using empirical evidence. It is also a way of gaining knowledge by means of direct and indirect observation or experience. Empiricism values some research more than other kinds. Empirical evidence (the record of one ...

of science and, according to G. E. R. Lloyd, played a significant role in the development of this methodology.

Calendar

The ancient Egyptians even developed an official calendar that contained twelve months, thirty days each, and five days at the end of the year.

Unlike the Babylonian calendar or the ones used in Greek city-states at the time, the official Egyptian calendar was much simpler as it was fixed and did not take

lunar

Lunar most commonly means "of or relating to the Moon".

Lunar may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lunar'' (series), a series of video games

* "Lunar" (song), by David Guetta

* "Lunar", a song by Priestess from the 2009 album ''Prior t ...

and solar cycles into consideration.

Mesopotamia

The ancient Mesopotamians had extensive knowledge about the

chemical properties

A chemical property is any of a material property, material's properties that becomes evident during, or after, a chemical reaction; that is, any attribute that can be established only by changing a substance's chemical substance, chemical identit ...

of clay, sand, metal ore,

bitumen

Bitumen ( , ) is an immensely viscosity, viscous constituent of petroleum. Depending on its exact composition, it can be a sticky, black liquid or an apparently solid mass that behaves as a liquid over very large time scales. In American Engl ...

, stone, and other natural materials, and applied this knowledge to practical use in manufacturing

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

,

faience

Faience or faïence (; ) is the general English language term for fine tin-glazed pottery. The invention of a white Ceramic glaze, pottery glaze suitable for painted decoration, by the addition of an stannous oxide, oxide of tin to the Slip (c ...

, glass, soap, metals,

lime plaster

Lime plaster is a type of plaster composed of sand, water, and lime, usually non-hydraulic hydrated lime (also known as slaked lime, high calcium lime or air lime). Ancient lime plaster often contained horse hair for reinforcement and pozzolan ...

, and waterproofing.

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

required knowledge about the properties of metals. Nonetheless, the Mesopotamians seem to have had little interest in gathering information about the natural world for the mere sake of gathering information and were far more interested in studying the manner in which the gods had ordered the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

. Biology of non-human organisms was generally only written about in the context of mainstream academic disciplines.

Animal physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

was studied extensively for the purpose of

divination

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

; the anatomy of the

liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

, which was seen as an important organ in

haruspicy

In the religion of ancient Rome, a haruspex was a person trained to practise a form of divination called haruspicy, the inspection of the entrails of sacrificed animals, especially the livers of sacrificed sheep and poultry.

Various ancient ...

, was studied in particularly intensive detail.

Animal behavior

Ethology is a branch of zoology that studies the behaviour of non-human animals. It has its scientific roots in the work of Charles Darwin and of American and German ornithologists of the late 19th and early 20th century, including Charle ...

was also studied for divinatory purposes. Most information about the training and domestication of animals was probably transmitted orally without being written down, but one text dealing with the training of horses has survived.

Mesopotamian medicine

The ancient

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

ns had no distinction between "rational science" and

magic

Magic or magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

** ''Magick'' (with ''-ck'') can specifically refer to ceremonial magic

* Magic (illusion), also known as sta ...

.

When a person became ill, doctors prescribed magical formulas to be recited as well as medicinal treatments.

The earliest medical prescriptions appear in

Sumerian during the

Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur or Ur III was a Sumerian dynasty based in the city of Ur in the 22nd and 21st centuries BC ( middle chronology). For a short period they were the preeminent power in Mesopotamia and their realm is sometimes referred to by ...

( 2112 BCE – 2004 BCE). The most extensive

Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

n medical text, however, is the ''Diagnostic Handbook'' written by the ''ummânū'', or chief scholar,

Esagil-kin-apli

Esagil-kin-apli, was the ''ummânū'', or chief scholar, of Babylonian king Adad-apla-iddina, 1067–1046 BCE, as he appears on the Uruk ''List of Sages and Scholars'' (165 BCE)W 20030,7 the Seleucid ''List of Sages and Scholars'', obverse line 16 ...

of

Borsippa

Borsippa (Sumerian language, Sumerian: BAD.SI.(A).AB.BAKI or Birs Nimrud, having been identified with Nimrod) is an archeological site in Babylon Governorate, Iraq, built on both sides of a lake about southwest of Babylon on the east bank of th ...

,

during the reign of the Babylonian king

Adad-apla-iddina

Adad-apla-iddina, typically inscribed in cuneiform mdIM- DUMU.UŠ-SUM''-na'', mdIM-A-SUM''-na'' or dIM''-ap-lam-i-din-'' 'nam''meaning the storm god “Adad has given me an heir”, was the 8th king of the 2nd Dynasty of Isin and the 4th Dynasty ...

(1069–1046 BCE). In

East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced ...

cultures, the main medicinal authority was a kind of exorcist-healer known as an ''

āšipu''.

The profession was generally passed down from father to son and was held in extremely high regard.

Of less frequent recourse was another kind of healer known as an ''asu'', who corresponds more closely to a modern physician and treated physical symptoms using primarily

folk remedies

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) refers to the knowledge, skills, and practices rooted in the cultural beliefs of various societies, especially Indigenous groups, used for maintaining health and treatin ...

composed of various herbs, animal products, and minerals, as well as potions, enemas, and ointments or

poultices. These physicians, who could be either male or female, also dressed wounds, set limbs, and performed simple surgeries. The ancient Mesopotamians also practiced

prophylaxis

Preventive healthcare, or prophylaxis, is the application of healthcare measures to prevent diseases.Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark as "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical and mental health a ...

and took measures to prevent the spread of disease.

Astronomy and celestial divination

In

Babylonian astronomy

Babylonian astronomy was the study or recording of celestial objects during the early history of Mesopotamia. The numeral system used, sexagesimal, was based on 60, as opposed to ten in the modern decimal system. This system simplified the ca ...

, records of the motions of the

star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s,

planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

s, and the

moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

are left on thousands of

clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian language, Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay t ...

s created by

scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of Printing press, automatic printing.

The work of scribes can involve copying manuscripts and other texts as well as ...

s. Even today, astronomical periods identified by Mesopotamian proto-scientists are still widely used in

Western calendars such as the

solar year

A tropical year or solar year (or tropical period) is the time that the Sun takes to return to the same position in the sky – as viewed from the Earth or another celestial body of the Solar System – thus completing a full cycle of astronom ...

and the

lunar month

In lunar calendars, a lunar month is the time between two successive syzygies of the same type: new moons or full moons. The precise definition varies, especially for the beginning of the month.

Variations

In Shona, Middle Eastern, and Euro ...

. Using this data, they developed mathematical methods to compute the changing length of daylight in the course of the year, predict the appearances and disappearances of the Moon and planets, and eclipses of the Sun and Moon. Only a few astronomers' names are known, such as that of

Kidinnu

Kidinnu (also ''Kidunnu''; possibly fl. 4th century BC; possibly died 14 August 330 BC) was a Chaldean astronomer and mathematician. Strabo of Amaseia called him Kidenas, Pliny the Elder called him Cidenas, and Vettius Valens called him Ki ...

, a

Chaldea

Chaldea () refers to a region probably located in the marshy land of southern Mesopotamia. It is mentioned, with varying meaning, in Neo-Assyrian cuneiform, the Hebrew Bible, and in classical Greek texts. The Hebrew Bible uses the term (''Ka� ...

n astronomer and mathematician. Kiddinu's value for the solar year is in use for today's calendars. Babylonian astronomy was "the first and highly successful attempt at giving a refined mathematical description of astronomical phenomena." According to the historian A. Aaboe, "all subsequent varieties of scientific astronomy, in the Hellenistic world, in India, in Islam, and in the West—if not indeed all subsequent endeavour in the exact sciences—depend upon Babylonian astronomy in decisive and fundamental ways."

To the

Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

ians and other

Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

ern cultures, messages from the gods or omens were concealed in all natural phenomena that could be deciphered and interpreted by those who are adept.

Hence, it was believed that the gods could speak through all terrestrial objects (e.g., animal entrails, dreams, malformed births, or even the color of a dog urinating on a person) and celestial phenomena.

Moreover, Babylonian astrology was inseparable from Babylonian astronomy.

Mathematics

The Mesopotamian

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

tablet

Plimpton 322

Plimpton 322 is a Babylonian clay tablet, believed to have been written around 1800 BC, that contains a mathematical table written in cuneiform script. Each row of the table relates to a Pythagorean triple, that is, a triple of integers (s ...

, dating to the 18th century BCE, records a number of

Pythagorean triple

A Pythagorean triple consists of three positive integers , , and , such that . Such a triple is commonly written , a well-known example is . If is a Pythagorean triple, then so is for any positive integer . A triangle whose side lengths are a Py ...

ts (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13) ..., hinting that the ancient Mesopotamians might have been aware of the

Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite t ...

over a millennium before Pythagoras.

Ancient and medieval South Asia and East Asia

Mathematical achievements from Mesopotamia had some influence on the development of mathematics in India, and there were confirmed transmissions of mathematical ideas between India and China, which were bidirectional.

Nevertheless, the mathematical and scientific achievements in India and particularly in China occurred largely independently

from those of Europe and the confirmed early influences that these two civilizations had on the development of science in Europe in the pre-modern era were indirect, with Mesopotamia and later the Islamic World acting as intermediaries.

[ The arrival of modern science, which grew out of the ]Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

, in India and China and the greater Asian region in general can be traced to the scientific activities of Jesuit missionaries who were interested in studying the region's flora

Flora (: floras or florae) is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. The corresponding term for animals is ''fauna'', and for f ...

and fauna

Fauna (: faunae or faunas) is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding terms for plants and fungi are ''flora'' and '' funga'', respectively. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively ...

during the 16th to 17th century.

India

Mathematics

The earliest traces of mathematical knowledge in the Indian subcontinent appear with the

The earliest traces of mathematical knowledge in the Indian subcontinent appear with the Indus Valley Civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation, was a Bronze Age civilisation in the Northwestern South Asia, northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 Common Era, BCE to 1300 BCE, and in i ...

(). The people of this civilization made bricks whose dimensions were in the proportion 4:2:1, which is favorable for the stability of a brick structure. They also tried to standardize measurement of length to a high degree of accuracy. They designed a ruler—the ''Mohenjo-daro ruler''—whose length of approximately was divided into ten equal parts. Bricks manufactured in ancient Mohenjo-daro often had dimensions that were integral multiples of this unit of length.

The Bakhshali manuscript contains problems involving arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

, algebra

Algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with abstract systems, known as algebraic structures, and the manipulation of expressions within those systems. It is a generalization of arithmetic that introduces variables and algebraic ope ...

and geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

, including mensuration. The topics covered include fractions, square roots, arithmetic

Arithmetic is an elementary branch of mathematics that deals with numerical operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In a wider sense, it also includes exponentiation, extraction of roots, and taking logarithms.

...

and geometric progression

A geometric progression, also known as a geometric sequence, is a mathematical sequence of non-zero numbers where each term after the first is found by multiplying the previous one by a fixed number called the ''common ratio''. For example, the s ...

s, solutions of simple equations, simultaneous linear equations

In mathematics, a system of linear equations (or linear system) is a collection of two or more linear equations involving the same variables.

For example,

: \begin

3x+2y-z=1\\

2x-2y+4z=-2\\

-x+\fracy-z=0

\end

is a system of three equations in ...

, quadratic equations

In mathematics, a quadratic equation () is an equation that can be rearranged in standard form as

ax^2 + bx + c = 0\,,

where the variable (mathematics), variable represents an unknown number, and , , and represent known numbers, where . (If and ...

and indeterminate equations

In mathematics, particularly in number theory, an indeterminate system has fewer equations than unknowns but an additional a set of constraints on the unknowns, such as restrictions that the values be integers. In modern times indeterminate equati ...

of the second degree.Pingala

Acharya Pingala (; c. 3rd2nd century BCE) was an ancient Indian poet and mathematician, and the author of the ' (), also called the ''Pingala-sutras'' (), the earliest known treatise on Sanskrit prosody.

The ' is a work of eight chapters in the ...

presents the ''Pingala-sutras'', the earliest known treatise on Sanskrit prosody

Sanskrit prosody or Chandas refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies.James Lochtefeld (2002), "Chandas" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing, , page 140 It is the study of poetic met ...

. He also presents a numerical system by adding one to the sum of place value

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** O ...

s. Pingala's work also includes material related to the Fibonacci numbers

In mathematics, the Fibonacci sequence is a sequence in which each element is the sum of the two elements that precede it. Numbers that are part of the Fibonacci sequence are known as Fibonacci numbers, commonly denoted . Many writers begin the s ...

, called '.

Indian astronomer and mathematician Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was the first of the major mathematician-astronomers from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. His works include the '' Āryabhaṭīya'' (which mentions that in 3600 ' ...

(476–550), in his ''Aryabhatiya

''Aryabhatiya'' (IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Indian astronomy, Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the ''Masterpiece, magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematics, Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philos ...

'' (499) introduced the sine

In mathematics, sine and cosine are trigonometric functions of an angle. The sine and cosine of an acute angle are defined in the context of a right triangle: for the specified angle, its sine is the ratio of the length of the side opposite th ...

function in trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics concerned with relationships between angles and side lengths of triangles. In particular, the trigonometric functions relate the angles of a right triangle with ratios of its side lengths. The fiel ...

and the number 0. In 628, Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian Indian mathematics, mathematician and Indian astronomy, astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the ''Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established Siddhanta, do ...

suggested that gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

was a force of attraction. He also lucidly explained the use of zero

0 (zero) is a number representing an empty quantity. Adding (or subtracting) 0 to any number leaves that number unchanged; in mathematical terminology, 0 is the additive identity of the integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and compl ...

as both a placeholder and a decimal digit

A numerical digit (often shortened to just digit) or numeral is a single symbol used alone (such as "1"), or in combinations (such as "15"), to represent numbers in positional notation, such as the common base 10. The name "digit" originate ...

, along with the Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system (also known as the Indo-Arabic numeral system, Hindu numeral system, and Arabic numeral system) is a positional notation, positional Decimal, base-ten numeral system for representing integers; its extension t ...

now used universally throughout the world. Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

translations of the two astronomers' texts were soon available in the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, introducing what would become Arabic numerals

The ten Arabic numerals (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) are the most commonly used symbols for writing numbers. The term often also implies a positional notation number with a decimal base, in particular when contrasted with Roman numera ...

to the Islamic world by the 9th century.[Ifrah, Georges. 1999. ''The Universal History of Numbers : From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer'', Wiley. .][O'Connor, J. J. and E. F. Robertson. 2000]

'Indian Numerals'

, ''MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive'', School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

Narayana Pandita (1340–1400) was an Indian mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

. Plofker writes that his texts were the most significant Sanskrit mathematics treatises after those of Bhaskara II, other than the Kerala school. He wrote the '' Ganita Kaumudi'' (lit. "Moonlight of mathematics") in 1356 about mathematical operations. The work anticipated many developments in combinatorics

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and as an end to obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many ...

.

Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics or the Kerala school was a school of Indian mathematics, mathematics and Indian astronomy, astronomy founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama in Kingdom of Tanur, Tirur, Malappuram district, Malappuram, K ...

made significant advances in astronomy and especially mathematics, including fields such as trigonometry and analysis. In particular, Madhava of Sangamagrama

Mādhava of Sangamagrāma (Mādhavan) Availabl/ref> () was an Indian mathematician and astronomer who is considered to be the founder of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics in the Late Middle Ages. Madhava made pioneering contributio ...

led advancement in analysis

Analysis (: analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (38 ...

by providing the infinite and taylor series expansion of some trigonometric functions and pi approximation.Parameshvara

Vatasseri Parameshvara Nambudiri ( 1380–1460) was a major Indian mathematician and astronomer of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama. He was also an astrologer. Parameshvara was a proponent of ...

(1380–1460), presents a case of the Mean Value theorem in his commentaries on Govindasvāmi

Govindasvāmi (or Govindasvāmin, Govindaswami) (c. 800 – c. 860) was an Indian mathematical astronomer most famous for his ''Bhashya'', a commentary on the ''Mahābhāskarīya'' of Bhāskara I, written around 830. The commentary contains many ...

and Bhāskara II

Bhāskara II ('; 1114–1185), also known as Bhāskarāchārya (), was an Indian people, Indian polymath, Indian mathematicians, mathematician, astronomer and engineer. From verses in his main work, Siddhānta Śiromaṇi, it can be inferre ...

. The ''Yuktibhāṣā

''Yuktibhāṣā'' (), also known as Gaṇita-yukti-bhāṣā and ( English: ''Compendium of Astronomical Rationale''), is a major treatise on mathematics and astronomy, written by the Indian astronomer Jyesthadeva of the Kerala school of mat ...

'' was written by Jyeshtadeva in 1530.

Astronomy

The first textual mention of astronomical concepts comes from the Veda

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

s, religious literature of India.Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' (, , from wikt:ऋच्, ऋच्, "praise" and wikt:वेद, वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian Miscellany, collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canoni ...

intelligent speculations about the genesis of the universe from nonexistence, the configuration of the universe, the spherical self-supporting earth, and the year of 360 days divided into 12 equal parts of 30 days each with a periodical intercalary month.".Tantrasangraha

Tantrasamgraha, or Tantrasangraha, (literally, ''A Compilation of the System'') is an important astronomical treatise written by Nilakantha Somayaji, an astronomer/mathematician belonging to the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.

The t ...

'' treatise, Nilakantha Somayaji

Keļallur Nīlakaṇṭha Somayāji (14 June 1444 – 1544), also referred to as Keļallur Comatiri, was a mathematician and astronomer of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. One of his most influential works was the comprehens ...

's updated the Aryabhatan model for the interior planets, Mercury, and Venus and the equation that he specified for the center of these planets was more accurate than the ones in European or Islamic astronomy until the time of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

in the 17th century.Jai Singh II

Sawai Jai Singh II (3 November 1688 – 21 September 1743), was the 30th Kachwaha Rajput ruler of the Kingdom of Amber, who later founded the fortified city of Jaipur and made it his capital. He became the ruler of Amber at the age of 11, after ...

of Jaipur

Jaipur (; , ) is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the List of cities and towns in Rajasthan, largest city of the north-western States and union territories of India, Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had ...

constructed five observatories

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial, marine, or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geophysics, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed.

Th ...

called Jantar Mantars in total, in New Delhi

New Delhi (; ) is the Capital city, capital of India and a part of the Delhi, National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the Government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Parliament ...

, Jaipur

Jaipur (; , ) is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the List of cities and towns in Rajasthan, largest city of the north-western States and union territories of India, Indian state of Rajasthan. , the city had ...

, Ujjain

Ujjain (, , old name Avantika, ) or Ujjayinī is a city in Ujjain district of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It is the fifth-largest city in Madhya Pradesh by population and is the administrative as well as religious centre of Ujjain ...

, Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the states and union territories of India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located south-east of Delhi; and about from the town of Vrindavan. In ancient ti ...

and Varanasi

Varanasi (, also Benares, Banaras ) or Kashi, is a city on the Ganges river in northern India that has a central place in the traditions of pilgrimage, death, and mourning in the Hindu world.*

*

*

* The city has a syncretic tradition of I ...

; they were completed between 1724 and 1735.

Grammar

Some of the earliest linguistic activities can be found in Iron Age India

In the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent, the Iron Age succeeded Bronze Age India and partly corresponds with the megalithic cultures of South India. Other Iron Age archaeological cultures of north India were the Painted Grey Ware cultu ...

(1st millennium BCE) with the analysis of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

for the purpose of the correct recitation and interpretation of Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed ...

texts. The most notable grammarian of Sanskrit was (c. 520–460 BCE), whose grammar formulates close to 4,000 rules for Sanskrit. Inherent in his analytic approach are the concepts of the phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

, the morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

and the root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

. The Tolkāppiyam

''Tolkāppiyam'', also romanised as ''Tholkaappiyam'' ( , ''lit.'' "ancient poem"), is the oldest extant Tamil grammar text and the oldest extant long work of Tamil literature. It is the earliest Tamil text mentioning Gods, perhaps linked to ...

text, composed in the early centuries of the common era,

Medicine

Findings from Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

graveyards in what is now Pakistan show evidence of proto-dentistry among an early farming culture. The ancient text Suśrutasamhitā of Suśruta

The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (, ) is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and one of the most important such treatises on this subject to survive from the ancient world. The ''Compendium of Suśruta'' is one of the foundational texts of Ayurveda ...

describes procedures on various forms of surgery, including rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty (, nose + , to shape), commonly called nose job, medically called nasal reconstruction, is a plastic surgery procedure for altering and reconstructing the human nose, nose. There are two types of plastic surgery used – plastic sur ...

, the repair of torn ear lobes, perineal lithotomy

Lithotomy from Greek for "lithos" (stone) and "tomos" ( cut), is a surgical method for removal of calculi, stones formed inside certain organs, such as the urinary tract (kidney stones), bladder (bladder stones), and gallbladder (gallstones), t ...

, cataract surgery, and several other excisions and other surgical procedures. The ''Charaka Samhita

The ''Charaka Samhita'' () is a Sanskrit text on Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine). Along with the '' Sushruta Samhita'', it is one of the two foundational texts of this field that have survived from ancient India. It is one of the three w ...

'' of Charaka

Charaka was one of the principal contributors to Ayurveda, a system of medicine and lifestyle developed in ancient India. He is known as a physician who edited the medical treatise entitled ''Charaka Samhita'', one of the foundational texts of ...

describes ancient theories on human body, etiology

Etiology (; alternatively spelled aetiology or ætiology) is the study of causation or origination. The word is derived from the Greek word ''()'', meaning "giving a reason for" (). More completely, etiology is the study of the causes, origins ...

, symptomology and therapeutics

A therapy or medical treatment is the attempted remediation of a health problem, usually following a medical diagnosis. Both words, ''treatment'' and ''therapy'', are often abbreviated tx, Tx, or Tx.

As a rule, each therapy has indications an ...

for a wide range of diseases.[MS Valiathan (2009), An Ayurvedic view of life, Current Science, Volume 96, Issue 9, pages 1186-1192]

Politics and state

An ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

policy and military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired Strategic goal (military), strategic goals. Derived from the Greek language, Greek word ''strategos'', the term strategy, when first used during the 18th ...

by Kautilya and , who are traditionally identified with (c. 350–283 BCE). In this treatise, the behaviors and relationships of the people, the King, the State, the Government Superintendents, Courtiers, Enemies, Invaders, and Corporations are analyzed and documented. Roger Boesche describes the ''Arthaśāstra

''Kautilya's Arthashastra'' (, ; ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, politics, economic policy and military strategy. The text is likely the work of several authors over centuries, starting as a compilation of ''Arthashas ...

'' as "a book of political realism, a book analyzing how the political world does work and not very often stating how it ought to work, a book that frequently discloses to a king what calculating and sometimes brutal measures he must carry out to preserve the state and the common good."

Logic

The development of Indian logic dates back to the Chandahsutra of Pingala and ''anviksiki Ānvīkṣikī is a term in Sanskrit denoting roughly the "science of inquiry" and it should have been recognized in India as a distinct branch of learning as early as 650 BCE. However, over the centuries its meaning and importance have undergone co ...

'' of Medhatithi Gautama (c. 6th century BCE); the Sanskrit grammar

The grammar of the Sanskrit language has a complex verbal system, rich nominal declension, and extensive use of compound nouns. It was studied and codified by Sanskrit grammarians from the later Vedic period (roughly 8th century BCE), culminatin ...

rules of Pāṇini

(; , ) was a Sanskrit grammarian, logician, philologist, and revered scholar in ancient India during the mid-1st millennium BCE, dated variously by most scholars between the 6th–5th and 4th century BCE.

The historical facts of his life ar ...

(c. 5th century BCE); the Vaisheshika

Vaisheshika (IAST: Vaiśeṣika; ; ) is one of the six schools of Hindu philosophy from ancient India. In its early stages, Vaiśeṣika was an independent philosophy with its own metaphysics, epistemology, logic, ethics, and soteriology. Over t ...

school's analysis of atomism

Atomism () is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its Atom, atoms appeared in both Ancient Greek philosophy, ancien ...

(c. 6th century BCE to 2nd century BCE); the analysis of inference

Inferences are steps in logical reasoning, moving from premises to logical consequences; etymologically, the word '' infer'' means to "carry forward". Inference is theoretically traditionally divided into deduction and induction, a distinct ...

by Gotama (c. 6th century BCE to 2nd century CE), founder of the Nyaya

Nyāya (Sanskrit: न्यायः, IAST: nyāyaḥ), literally meaning "justice", "rules", "method" or "judgment", is one of the six orthodox (Āstika) schools of Hindu philosophy. Nyāya's most significant contributions to Indian philosophy ...

school of Hindu philosophy

Hindu philosophy or Vedic philosophy is the set of philosophical systems that developed in tandem with the first Hinduism, Hindu religious traditions during the Iron Age in India, iron and Classical India, classical ages of India. In Indian ...

; and the tetralemma

The tetralemma is a figure that features prominently in the logic of India.

Definition

It states that with reference to any a logical proposition (or axiom) X, there are four possibilities:

: X (affirmation)

: \neg X (negation)

: X \land\neg X ...

of Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna (Sanskrit: नागार्जुन, ''Nāgārjuna''; ) was an Indian monk and Mahayana, Mahāyāna Buddhist Philosophy, philosopher of the Madhyamaka (Centrism, Middle Way) school. He is widely considered one of the most importa ...

(c. 2nd century CE).

Indian logic stands as one of the three original traditions of logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, alongside the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and the Chinese logic. The Indian tradition continued to develop through early to modern times, in the form of the Navya-Nyāya

The Navya-Nyāya (sanskrit: नव्य-न्याय) or Neo-Logical '' darśana'' (view, system, or school) of Indian logic and Indian philosophy was founded in the 13th century CE by the philosopher Gangeśa Upādhyāya of Mithila and co ...

school of logic.

In the 2nd century, the Buddhist

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

philosopher Nagarjuna

Nāgārjuna (Sanskrit: नागार्जुन, ''Nāgārjuna''; ) was an Indian monk and Mahayana, Mahāyāna Buddhist Philosophy, philosopher of the Madhyamaka (Centrism, Middle Way) school. He is widely considered one of the most importa ...

refined the ''Catuskoti'' form of logic. The Catuskoti is also often glossed ''Tetralemma

The tetralemma is a figure that features prominently in the logic of India.

Definition

It states that with reference to any a logical proposition (or axiom) X, there are four possibilities:

: X (affirmation)

: \neg X (negation)

: X \land\neg X ...

'' (Greek) which is the name for a largely comparable, but not equatable, 'four corner argument' within the tradition of Classical logic

Classical logic (or standard logic) or Frege–Russell logic is the intensively studied and most widely used class of deductive logic. Classical logic has had much influence on analytic philosophy.

Characteristics

Each logical system in this c ...

.

Navya-Nyāya developed a sophisticated language and conceptual scheme that allowed it to raise, analyse, and solve problems in logic and epistemology. It systematised all the Nyāya concepts into four main categories: sense or perception (pratyakşa), inference (anumāna), comparison or similarity (upamāna

''Pramana'' (; IAST: Pramāṇa) literally means "proof" and "means of knowledge". ), and testimony (sound or word; śabda).

China

Chinese mathematics

From the earliest the Chinese used a positional decimal system on counting boards in order to calculate. To express 10, a single rod is placed in the second box from the right. The spoken language uses a similar system to English: e.g. four thousand two hundred and seven. No symbol was used for zero. By the 1st century BCE, negative numbers and decimal fractions were in use and ''The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art

''The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art'' is a Chinese mathematics book, composed by several generations of scholars from the 10th–2nd century BCE, its latest stage being from the 1st century CE. This book is one of the earliest surviving ...