Charles Milles Manson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Milles Manson (; November 12, 1934November 19, 2017) was an American criminal and musician who led the Manson Family, a

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis. Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis. Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. As the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, Manson was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His initial death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder in Los Angeles County Court for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman. He was also convicted of first-degree murder for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea. Following the 1972 decision of ''

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. As the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, Manson was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His initial death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder in Los Angeles County Court for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman. He was also convicted of first-degree murder for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea. Following the 1972 decision of ''

In the 1980s, Manson gave four interviews to the mainstream media. The first, recorded at

In the 1980s, Manson gave four interviews to the mainstream media. The first, recorded at

''Diary of a Mad Saloon Owner''

. April–May 2005. The third, with

On September 5, 2007,

On September 5, 2007,

FBI file on Charles Manson

Cease to Exist: The Saga of Dennis Wilson & Charles Manson

– compendium of first-hand accounts edited by Jason Austin Penick Legal documents

''People v. Manson'', 71 Cal. App. 3d 1 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, June 23, 1977).

''People v. Manson'', 61 Cal. App. 3d 102 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, August 13, 1976). Retrieved June 19, 2007. News articles * – article by co-author of 1970 ''Rolling Stone'' story on Manson. * Linder, Douglas

University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School. 2002. April 7, 2007. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Manson, Charles 1934 births 2017 deaths 20th-century American criminals 20th-century apocalypticists American conspiracy theorists American folk rock musicians American male criminals American mass murderers American neo-Nazis American people convicted of murder American people who died in prison custody American prisoners sentenced to death American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment American rapists American singer-songwriters Anti-black racism in the United States Crime in California Criminals from California Criminals from Ohio Deaths from cancer in California Deaths from colorectal cancer Deaths from respiratory failure American former Scientologists Founders of new religious movements History of Los Angeles Manson Family Outsider musicians People convicted of murder by California People from Cincinnati People with antisocial personality disorder People with schizophrenia Prisoners sentenced to death by California Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by California Prisoners who died in California detention Self-declared messiahs Cult leaders

cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

based in California, in the late 1960s. Some of the members committed a series of nine murders at four locations in July and August 1969. In 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder and conspiracy

A conspiracy, also known as a plot, is a secret plan or agreement between persons (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder or treason, especially with political motivation, while keeping their agree ...

to commit murder for the deaths of seven people, including the film actress Sharon Tate

Sharon Marie Tate Polanski (January 24, 1943 – August 9, 1969) was an American actress and model. During the 1960s, she played small television roles before appearing in films and was regularly featured in fashion magazines as a model and cover ...

. The prosecution contended that, while Manson never directly ordered the murders, his ideology constituted an overt act of conspiracy.

Before the murders, Manson had spent more than half of his life in correctional institutions. While gathering his cult following, Manson was a singer-songwriter on the fringe of the Los Angeles music industry, chiefly through a chance association with Dennis Wilson

Dennis Carl Wilson (December 4, 1944 – December 28, 1983) was an American musician, singer, and songwriter who co-founded the Beach Boys. He is best remembered as their drummer and as the middle brother of bandmates Brian and Carl Wilson. ...

of the Beach Boys

The Beach Boys are an American Rock music, rock band that formed in Hawthorne, California, in 1961. The group's original lineup consisted of brothers Brian Wilson, Brian, Dennis Wilson, Dennis, and Carl Wilson, their cousin Mike Love, and frie ...

, who introduced Manson to record producer Terry Melcher

Terrence Paul Melcher (born Terrence Paul Jorden; February 8, 1942 – November 19, 2004) was an American record producer, singer, and songwriter who was instrumental in shaping the mid-to-late 1960s California Sound and folk rock movements. His ...

. In 1968, the Beach Boys recorded Manson's song "Cease to Exist", renamed "Never Learn Not to Love

"Never Learn Not to Love" is a song recorded by the American rock band the Beach Boys that was issued as the B-side to their "Bluebirds over the Mountain" single on December 2, 1968. Credited to Dennis Wilson, the song was an altered version of ...

" as a single B-side, but without a credit to Manson. Afterward, Manson attempted to secure a record contract through Melcher, but was unsuccessful.

Manson would often talk about the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

, including their eponymous 1968 album. According to Los Angeles County District Attorney

The District Attorney of Los Angeles County is in charge of the office that prosecutes felony and misdemeanor crimes that occur within Los Angeles County, California, United States. The current district attorney (DA) is George Gascón.

Some mi ...

, Vincent Bugliosi

Vincent T. Bugliosi Jr. (; August 18, 1934 – June 6, 2015) was an American prosecutor and author who served as Deputy District Attorney for the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office between 1964 and 1972.

He became best known for s ...

, Manson felt guided by his interpretation of the Beatles' lyrics and adopted the term " Helter Skelter" to describe an impending apocalyptic race war

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positio ...

. During his trial, Bugliosi argued that Manson had intended to start a race war, although Manson and others disputed this. Contemporary interviews and trial witness testimony insisted that the Tate–LaBianca murders were copycat crime

A copycat crime is a criminal act that is modelled after or inspired by a previous crime. It notably occurs after exposure to media content depicted said crimes, and/or a live criminal model.

Copycat effect

The copycat effect is the alleged tende ...

s intended to exonerate Manson's friend Bobby Beausoleil

Robert Kenneth Beausoleil (born November 6, 1947) is an American murderer and associate of Charles Manson and members of his communal Manson Family. He was convicted and sentenced to death for the July 27, 1969 fatal stabbing of Gary Hinman, w ...

.Day, James Buddy (Director). 2017. ''Charles Manson: The Final Words'' (Documentary). Pyramid Productions. Manson himself denied having instructed anyone to murder anyone.

1934–1967: Early life

Childhood

Charles Manson was born on November 12, 1934, to fifteen-year-old Kathleen Manson-Bower-Cavender, née Maddox (1919–1973), in theUniversity of Cincinnati Academic Health Center

The University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center (AHC) is a collection of health colleges and institutions of the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio. It trains health care professionals and provides research and patient care. AHC has st ...

in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. He was named Charles Milles Maddox.

Manson's biological father appears to have been Colonel Walker Henderson Scott Sr. (1910–1954) of Catlettsburg, Kentucky

Catlettsburg is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Boyd County, Kentucky, United States. The city population was 1,856 at the 2010 census. Catlettsburg is a part of the Huntington-Ashland, WV-KY-OH, Metropolitan Statistical Area ...

, against whom Kathleen Maddox filed a paternity

Paternity may refer to:

*Father, the male parent of a (human) child

*Paternity (law), fatherhood as a matter of law

* ''Paternity'' (film), a 1981 comedy film starring Burt Reynolds

* "Paternity" (''House''), a 2004 episode of the television seri ...

suit that resulted in an agreed judgment in 1937. Scott worked intermittently in local mills, and had a local reputation as a con artist

A confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using their credulity, naïveté, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have def ...

. He allowed Maddox to believe that he was an army colonel, although "Colonel" was merely his given name. When Maddox told Scott that she was pregnant, he told her he had been called away on army business; after several months she realized he had no intention of returning. Manson may never have known his biological father.

In August 1934, before Manson's birth, Maddox married William Eugene Manson (1909–1961), a "laborer" at a dry cleaning business. Maddox often went on drinking sprees with her brother Luther, leaving Charles with multiple babysitters. They divorced on April 30, 1937, after William alleged "gross neglect of duty" by Maddox. Charles retained William's last name, Manson. On August 1, 1939, Luther and Kathleen Maddox were arrested for assault and robbery. Kathleen and Luther were sentenced to five and ten years of imprisonment, respectively.

Manson was placed in the home of an aunt and uncle in McMechen, West Virginia

McMechen is a city in Marshall County, West Virginia, United States, situated along the Ohio River. It is part of the Wheeling, West Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 1,714 at the 2020 census.

History

McMechen is named a ...

. His mother was paroled in 1942. Manson later characterized the first weeks after she returned from prison as the happiest time in his life. Weeks after Maddox's release, Manson's family moved to Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston is the capital and List of cities in West Virginia, most populous city of West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Elk River (West Virginia), Elk and Kanawha River, Kanawha rivers, the city had a population of 48,864 at the 20 ...

, where Manson continually played truant and his mother spent her evenings drinking. She was arrested for grand larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Engla ...

, but not convicted. The family later moved to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, where Maddox met an alcoholic with the last name "Lewis" through Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is an international mutual aid fellowship of alcoholics dedicated to abstinence-based recovery from alcoholism through its spiritually-inclined Twelve Step program. Following its Twelve Traditions, AA is non-professi ...

meetings, and married him in August 1943.

First offenses

In an interview withDiane Sawyer

Lila Diane Sawyer (; born December 22, 1945) is an American television broadcast journalist known for anchoring major programs on two networks including ''ABC World News Tonight'', '' Good Morning America'', ''20/20'', and '' Primetime'' newsmag ...

, Manson said that when he was nine, he set his school on fire. Manson also got in trouble for truancy and petty theft. Although there was a lack of foster home placements, in 1947, at the age of 13, Manson was placed in the Gibault School for Boys in Terre Haute, Indiana

Terre Haute ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, about 5 miles east of the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a ...

, a school for male delinquents run by Catholic priests. Gibault was a strict school, where punishment for even the smallest infraction included beatings with either a wooden paddle or a leather strap. Manson ran away from Gibault and slept in the woods, under bridges, and wherever else he could find shelter.

Manson fled home to his mother, and spent Christmas 1947 in McMechen, at his aunt and uncle's house. His mother returned him to Gibault. Ten months later, he ran away to Indianapolis. In 1948, in Indianapolis, Manson committed his first known crime by robbing a grocery store. At first the robbery was simply to find something to eat. However, Manson found a cigar box containing just over a hundred dollars, and he took the money. He used the money to rent a room on Indianapolis's Skid Row and to buy food.

For a time, Manson had a job delivering messages for Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

in an attempt to live a life free of crime. However, he quickly began to supplement his wages through petty theft. He was eventually caught, and in 1949 a sympathetic judge sent him to Boys Town, a juvenile facility in Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

.Charles Manson – Diane Sawyer Interview. After four days at Boys Town, he and fellow student Blackie Nielson obtained a gun and stole a car. They used it to commit two armed robberies on their way to the home of Nielson's uncle in Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria ...

. Nielson's uncle was a professional thief, and when the boys arrived he allegedly took them on as apprentices. Manson was arrested two weeks later during a nighttime raid on a Peoria store. In the investigation that followed, he was linked to his two earlier armed robberies. He was sent to the Indiana Boys School, a strict reform school.

At the school, other students allegedly raped Manson with the encouragement of a staff member, and he was repeatedly beaten. He ran away from the school eighteen times. While at the school, Manson developed a self-defense technique he later called the "insane game". When he was physically unable to defend himself, he would screech, grimace and wave his arms to convince aggressors that he was insane. After a number of failed attempts, he escaped with two other boys in February 1951. The three escapees were robbing filling stations while attempting to drive to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in stolen cars when they were arrested in Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. For the federal crime

In the United States, a federal crime or federal offense is an act that is made illegal by U.S. federal legislation enacted by both the United States Senate and United States House of Representatives and signed into law by the president. Prosec ...

of driving a stolen car across state lines, Manson was sent to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

's National Training School for Boys The National Training School For Boys, located in what is now known as the Fort Lincoln area of Washington, D.C., was a Federal Government juvenile correctional institution for offenders under the age of seventeen. The school was governed by a boa ...

. On arrival he was given aptitude tests which determined that he was illiterate, but had an above-average IQ of 109. His case worker deemed him aggressively antisocial

Antisocial may refer to:

Sociology, psychiatry and psychology

*Anti-social behaviour

*Antisocial personality disorder

*Psychopathy

*Conduct disorder

Law

*Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003

*Anti-Social Behaviour Order

*Crime and Disorder Act 1998

*P ...

.

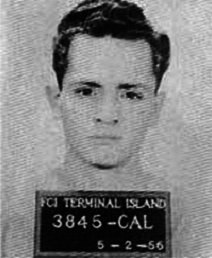

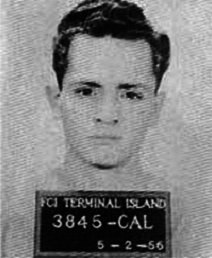

First imprisonment

On a psychiatrist's recommendation, Manson was transferred in October 1951 to Natural Bridge Honor Camp, aminimum security

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correcti ...

institution. His aunt visited him and told administrators she would let him stay at her house and would help him find work. Manson had a parole hearing scheduled for February 1952. However, in January, he was caught raping a boy at knifepoint. Manson was transferred to the Federal Reformatory in Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines Petersburg (along with the city of Colonial Heights) with Din ...

. There he committed a further "eight serious disciplinary offenses, three involving homosexual acts". He was then moved to a maximum security Maximum Security may refer to:

* Supermax, "control-unit" prisons, or units within prisons

* Maximum Security (comics), a comic book miniseries published by Marvel Comics

* ''Maximum Security'' (Tony MacAlpine album), 1987

* ''Maximum Security'' ...

reformatory

A reformatory or reformatory school is a youth detention center or an adult correctional facility popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Western countries. In the United Kingdom and United States, they came out of social concerns ...

at Chillicothe, Ohio

Chillicothe ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Ross County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Scioto River 45 miles (72 km) south of Columbus, Chillicothe was the first and third capital of Ohio. It is the only city in Ross Count ...

, where he was expected to remain until his release on his 21st birthday in November 1955. Good behavior led to an early release in May 1954, to live with his aunt and uncle in McMechen.

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis. Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis. Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

in a car he had stolen in Ohio, Manson was again charged with a federal crime for taking the vehicle across state lines. After a psychiatric evaluation, he was given five years' probation. Manson's failure to appear at a Los Angeles hearing on an identical charge filed in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

resulted in his March 1956 arrest in Indianapolis. His probation was revoked, and he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment at Terminal Island

Terminal Island, historically known as Isla Raza de Buena Gente, is a largely artificial island located in Los Angeles County, California, between the neighborhoods of Wilmington and San Pedro in the city of Los Angeles, and the city of Long Be ...

in Los Angeles.

While Manson was in prison, Rosalie gave birth to their son, Charles Manson Jr. During his first year at Terminal Island, Manson received visits from Rosalie and his mother, who were now living together in Los Angeles. In March 1957, when the visits from his wife ceased, his mother informed him Rosalie was living with another man. Less than two weeks before a scheduled parole hearing, Manson tried to escape by stealing a car. He was given five years' probation and his parole was denied.

Second imprisonment

Manson received five years' parole in September 1958, the same year in which Rosalie received a decree of divorce. By November, he was pimping a 16-year-old girl and was receiving additional support from a girl with wealthy parents. In September 1959, he pleaded guilty to a charge of attempting to cash a forgedU.S. Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and th ...

check, which he claimed to have stolen from a mailbox; the latter charge was later dropped. He received a 10-year suspended sentence

A suspended sentence is a sentence on conviction for a criminal offence, the serving of which the court orders to be deferred in order to allow the defendant to perform a period of probation. If the defendant does not break the law during that ...

and probation after a young woman named Leona, who had an arrest record for prostitution, made a "tearful plea" before the court that she and Manson were "deeply in love ... and would marry if Charlie were freed". Before the year's end, the woman did marry Manson, possibly so she would not be required to testify against him.

Manson took Leona and another woman to New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

for purposes of prostitution, resulting in him being held and questioned for violating the Mann Act

The White-Slave Traffic Act, also called the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, ; ''codified as amended at'' ). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act mad ...

. Though he was released, Manson correctly suspected that the investigation had not ended. When he disappeared in violation of his probation, a bench warrant

An arrest warrant is a warrant issued by a judge or magistrate on behalf of the state, which authorizes the arrest and detention of an individual, or the search and seizure of an individual's property.

Canada

Arrest warrants are issued by a ju ...

was issued. An indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a legal person, person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felony, felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concep ...

for violation of the Mann Act followed in April 1960. Following the arrest of one of the women for prostitution, Manson was arrested in June in Laredo, Texas

Laredo ( ; ) is a city in and the county seat of Webb County, Texas, United States, on the north bank of the Rio Grande in South Texas, across from Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Laredo has the distinction of flying seven flags (the flag of t ...

, and was returned to Los Angeles. For violating his probation on the check-cashing charge, he was ordered to serve his ten-year sentence.

Manson spent a year trying unsuccessfully to appeal the revocation of his probation. In July 1961, he was transferred from the Los Angeles County Jail

The Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department (LASD), officially the County of Los Angeles Sheriff's Department, is a law enforcement agency serving Los Angeles County, California. LASD is the largest sheriff's department in the United States a ...

to the United States Penitentiary

The Federal Bureau of Prisons classifies prisons into seven categories:

* United States penitentiaries

* Federal correctional institutions

* Private correctional institutions

* Federal prison camps

* Administrative facilities

* Federal correctio ...

at McNeil Island

McNeil Island is an island in the northwest United States in south Puget Sound, located southwest of Tacoma, Washington. With a land area of , it lies just north of Anderson Island; Fox Island is to the north, across Carr Inlet, and to the ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. There, he took guitar lessons from Barker–Karpis gang leader Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and obtained from another inmate a contact name of someone at Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

in Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

, Phil Kaufman. Among his fellow prisoners during this time was Danny Trejo

Danny Trejo ( ; born May 16, 1944) is an American actor. He has appeared in films including ''Desperado'', ''Heat'', and the ''From Dusk Till Dawn'' film series. With frequent collaborator and his second cousin Robert Rodriguez, he portrayed ...

, who participated in several hypnosis sessions. According to Jeff Guinn's 2013 biography of Manson, his mother moved to Washington State to be closer to him during his McNeil Island incarceration, working nearby as a waitress.

Although the Mann Act charge had been dropped, the attempt to cash the Treasury check was still a federal offense. Manson's September 1961 annual review noted he had a "tremendous drive to call attention to himself", an observation echoed in September 1964. In 1963, Leona was granted a divorce. During the process she alleged that she and Manson had a son, Charles Luther. According to a popular urban legend, Manson auditioned unsuccessfully for the Monkees

The Monkees were an American rock and pop band, formed in Los Angeles in 1966, whose lineup consisted of the American actor/musicians Micky Dolenz, Michael Nesmith and Peter Tork alongside English actor/singer Davy Jones. The group was conc ...

in late 1965; this is refuted by the fact that Manson was still incarcerated at McNeil Island at that time.

In June 1966, Manson was sent for the second time to Terminal Island in preparation for early release. By the time of his release day on March 21, 1967, he had spent more than half of his 32 years in prisons and other institutions. This was mainly because he had broken federal laws. Federal sentences were, and remain, much more severe than state sentences for many of the same offenses. Telling the authorities that prison had become his home, he requested permission to stay.

1968: San Francisco and cult formation

Parolee and patient

Less than a month after his 1967 release from prison, Manson moved toBerkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

from Los Angeles, which could have been a probation violation. Instead, after calling the San Francisco probation office upon his arrival, he was transferred to the supervision of criminology

Criminology (from Latin , "accusation", and Ancient Greek , ''-logia'', from λόγος ''logos'' meaning: "word, reason") is the study of crime and deviant behaviour. Criminology is an interdisciplinary field in both the behavioural and so ...

doctoral researcher and federal probation officer Roger Smith. Until the spring of 1968, Smith worked at the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic (HAFMC), which Manson and his family frequented throughout their stay in the Haight. Roger Smith, as well as the HAFMC's founder David E. Smith, received funding from the National Institutes of Health, and reportedly the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

to study the effects of drugs like LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), also known colloquially as acid, is a potent psychedelic drug. Effects typically include intensified thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception. At sufficiently high dosages LSD manifests primarily mental, vi ...

and methamphetamine

Methamphetamine (contracted from ) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is mainly used as a recreational drug and less commonly as a second-line treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obesity. Methamph ...

on the counterculture movement

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon that developed throughout much of the Western world in the 1960s and has been ongoing to the present day. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the civil rights mo ...

in Haight–Ashbury. The patients at the clinic became subjects of their research, including Manson and his expanding group of (mostly) female followers, who came to see Roger Smith regularly.

Manson received permission from Roger Smith to move from Berkeley to the Haight-Ashbury District in San Francisco. He first took LSD and would use it frequently during his time there. David Smith, who had studied the effects of LSD and amphetamines in rodents, wrote that the change in Manson's personality during this time "was the most abrupt Roger Smith had observed in his entire professional career." Manson also read the book ''Stranger in a Strange Land

''Stranger in a Strange Land'' is a 1961 science fiction novel by American author Robert A. Heinlein. It tells the story of Valentine Michael Smith, a human who comes to Earth in early adulthood after being born on the planet Mars and raised by ...

'', a science fiction novel by Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

. Inspired by the burgeoning free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

philosophy in Haight–Ashbury during the Summer of Love

The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people, mostly young people sporting hippie fashions of dress and behavior, converged in San Francisco's neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury. ...

, Manson began preaching his own philosophy based on a mixture of ''Stranger in a Strange Land'', the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

, Scientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It has been variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religious movement. The most recent published census data indi ...

, Dale Carnegie

Dale Carnegie (; spelled Carnagey until c. 1922; November 24, 1888 – November 1, 1955) was an American writer and lecturer, and the developer of courses in self-improvement, salesmanship, corporate training, public speaking, and interpersonal ...

and the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

, which quickly earned him a following.

Cult formation

Manson had already gained his first follower at theUC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of Californi ...

campus, librarian Mary Brunner

Mary Theresa Brunner (born December 17, 1943) is a former member of the " Manson Family" who was present during the 1969 murder of Gary Hinman, a California musician and Ph.D. candidate. She was arrested for numerous offenses, including credit c ...

. He talked her into letting him sleep at her house for a few nights, an arrangement that quickly became permanent. He then met Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme

Lynette Alice "Squeaky" Fromme (born October 22, 1948) is an American criminal who was a member of the Manson family, a cult led by Charles Manson. Though not involved in the Tate–LaBianca murders for which the Manson family is best known, ...

, a runaway teen, and convinced her to live with him and Brunner. Manson soon began to attract large crowds of listeners and some dedicated followers. He targeted individuals for manipulation who were emotionally insecure and social outcasts.Smith, p. 259 In his book ''Love Needs Care'' about his time at the HAFMC, David Smith claims that Manson attempted to reprogram their minds to "submit totally to his will" through the use of "LSD and … unconventional sexual practices" that would turn his followers into "empty vessels that would accept anything he poured." Manson Family member Paul Watkins, testified that Manson would encourage group LSD trips and take lower doses himself to "keep his wits about him." Watkins said that "Charlie's trip was to program us all to submit." By the end of his stay in the Haight in April 1968, Manson had attracted 20 or so followers, all under the supervision of his parole officer Roger Smith and many of the staff at the HAFMC.Smith, p. 260

The core members of Manson's following eventually included: Charles 'Tex' Watson, a musician and former actor; Bobby Beausoleil

Robert Kenneth Beausoleil (born November 6, 1947) is an American murderer and associate of Charles Manson and members of his communal Manson Family. He was convicted and sentenced to death for the July 27, 1969 fatal stabbing of Gary Hinman, w ...

, a former musician and pornographic actor

A pornographic film actor or actress, pornographic performer, adult entertainer, or porn star is a person who performs sex acts in video that is usually characterized as a pornographic movie. Such videos tend to be made in a number of dist ...

; Brunner; Susan Atkins

Susan Denise Atkins (May 7, 1948 – September 24, 2009) was an American convicted murderer who was a member of Charles Manson's "Family". Manson's followers committed a series of nine murders at four locations in California, over a perio ...

; Patricia Krenwinkel

Patricia Dianne Krenwinkel (born December 3, 1947) is an American murderer and a former member of the Manson Family. During her time with Manson's group, she was known by various aliases such as Big Patty, Yellow, Marnie Reeves and Mary Ann Sco ...

; and Leslie Van Houten

Leslie Louise Van Houten (born August 23, 1949) is an American convicted murderer and former member of the Manson Family. During her time with Manson's group, she was known by various aliases such as Louella Alexandria, Leslie Marie Sankston, Li ...

.

Further arrests

Supervised by his parole officer Roger Smith, Manson grew his family through drug use and prostitution without interference from the authorities. Manson was arrested on July 31, 1967, for attempting to prevent the arrest of one of his followers,Ruth Ann Moorehouse

Ruth (or its variants) may refer to:

Places

France

* Château de Ruthie, castle in the commune of Aussurucq in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques département of France

Switzerland

* Ruth, a hamlet in Cologny

United States

* Ruth, Alabama

* Ruth, Arka ...

. Instead of Manson being sent back to prison, the charge was reduced to a misdemeanor and Manson was given three additional years of probation. He avoided prosecution again in July 1968, when he and the family were arrested while moving from San Francisco to Los Angeles with the permission of Roger Smith, when his bus crashed into a ditch, where Manson and members of his family, including Brunner and Manson's newborn baby, were found sleeping naked by police. Afterwards, he was again arrested and released only a few days later, this time on a drug charge.

Doomsday beliefs

The Manson Family developed into adoomsday cult

A doomsday cult is a cult, that believes in apocalypticism and millenarianism, including both those that predict disaster and those that attempt to destroy the entire universe. Sociologist John Lofland coined the term ''doomsday cult'' in his ...

when Manson became fixated on the idea of an imminent apocalyptic race war between America's Black population and the larger White population. A white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

, Manson told some of the Manson Family that Black people in America would rise up and kill all white people except for Manson and his "Family", but that they were not intelligent enough to survive on their own; they would need a white man to lead them, and so they would serve Manson as their "master". According to Vincent Bugliosi

Vincent T. Bugliosi Jr. (; August 18, 1934 – June 6, 2015) was an American prosecutor and author who served as Deputy District Attorney for the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office between 1964 and 1972.

He became best known for s ...

, in late 1968, Manson adopted the term "Helter Skelter", taken from a song on the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

' recently released ''White Album

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

'', to refer to this upcoming war.

1969–1971: Murders and trial

Murders

In early August 1969, some Manson Family members committed murders in Los Angeles. The Manson Family gained national notoriety after the murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others in her home on August 8 and 9, 1969, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca the next day.Tex Watson

Charles Denton "Tex" Watson (born December 2, 1945) is an American murderer who was a central member of the " Manson Family" led by Charles Manson. On August 9, 1969, Watson, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Susan Atkins murdered pregnant actress Sharon ...

and three other members of the Family committed the Tate–LaBianca murders, allegedly under Manson's instructions. While it was later accepted at trial that Manson never expressly ordered the murders, his behavior was deemed to warrant a conviction of first degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Evidence pointed to Manson's obsession with inciting a race war by killing those he thought were "pigs" and his belief that this would show the "nigger" how to do the same. Family members were also responsible for other assaults, thefts, crimes, and the attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

in Sacramento by Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme

Lynette Alice "Squeaky" Fromme (born October 22, 1948) is an American criminal who was a member of the Manson family, a cult led by Charles Manson. Though not involved in the Tate–LaBianca murders for which the Manson family is best known, ...

.

While it is often thought that Manson never murdered or attempted to murder anyone himself, true crime

True crime is a nonfiction literary, podcast, and film genre in which the author examines an actual crime and details the actions of real people associated with and affected by criminal events.

The crimes most commonly include murder; about 40 per ...

writer James Buddy Day, in his book ''Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson'', claimed that Manson shot drug dealer Bernard Crowe on July 1, 1969. Crowe survived.

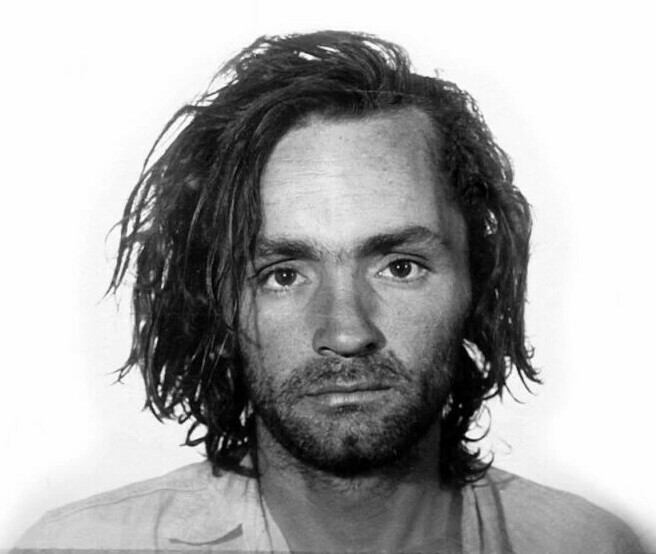

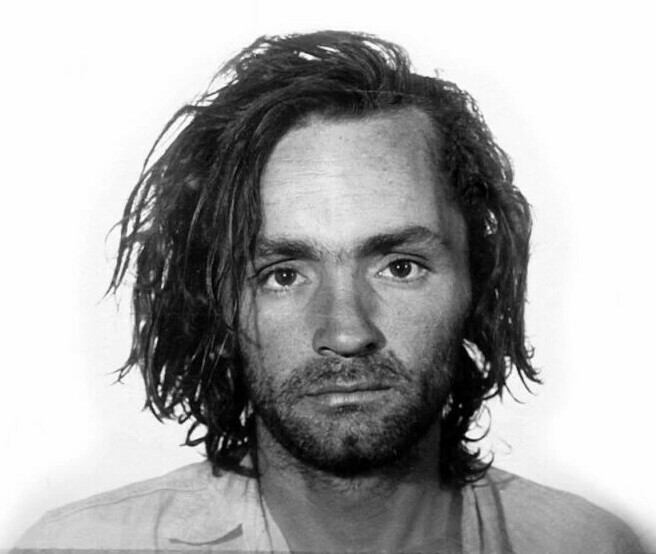

Trial

The State of California tried Manson for the Tate and LaBianca murders with co-defendants,Leslie Van Houten

Leslie Louise Van Houten (born August 23, 1949) is an American convicted murderer and former member of the Manson Family. During her time with Manson's group, she was known by various aliases such as Louella Alexandria, Leslie Marie Sankston, Li ...

, Susan Atkins

Susan Denise Atkins (May 7, 1948 – September 24, 2009) was an American convicted murderer who was a member of Charles Manson's "Family". Manson's followers committed a series of nine murders at four locations in California, over a perio ...

, and Patricia Krenwinkel

Patricia Dianne Krenwinkel (born December 3, 1947) is an American murderer and a former member of the Manson Family. During her time with Manson's group, she was known by various aliases such as Big Patty, Yellow, Marnie Reeves and Mary Ann Sco ...

. Co-defendant Tex Watson was tried at a later date after being extradited from Texas. The trial began on July 15, 1970. Manson appeared wearing fringed buckskins

Buckskins are clothing, usually consisting of a jacket and leggings, made from buckskin, a soft sueded leather from the hide of deer. Buckskins are often trimmed with a fringe – originally a functional detail, to allow the garment to shed ...

, his typical clothing at Spahn Ranch

Spahn Ranch, also known as the Spahn Movie Ranch, was a 55-acre (22.3 ha) movie ranch in Los Angeles, California. For a period it was used as a ranch, dairy farm and later movie set during the era of westerns. After a decline in use for filming b ...

.Linda Deutch, "'This is crazy': Former AP reporter remembers Manson trial", AP, November 20, 2017.

On July 24, 1970 – the first day of testimony – Manson appeared in court with an "X" carved into his forehead. His followers issued a statement from Manson saying "I have "X'd myself from your world". The following day, Manson's co-defendants, Van Houten, Atkins, and Krenwinkel, also appeared in court, with an "X" carved in their foreheads.

Members of the Manson Family camped outside of the courthouse, and held a vigil on a street corner, because they were excluded from the courtroom for being disruptive. Other members of the Manson Family also carved crosses into their heads. One day some members of the Manson Family wore saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of ''Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma and styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly as a seasoning and colouring agent i ...

robes to the trial, saying if Manson was convicted they would immolate

Immolation may refer to:

*Death by burning

*Self-immolation, the act of burning oneself

*Immolation (band), a death metal band from Yonkers, New York

*'' The Immolation'', a 1977 novel by Goh Poh Seng

*''Dance Dance Immolation'', an interactive pe ...

themselves – a reference to monks and nuns in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

who set fire to themselves to protest the Vietnam war

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

.

The State presented dozens of witnesses during the trial. However, its primary witness was Linda Kasabian

Linda Darlene Kasabian (born Drouin; June 21, 1949) is a former member of the Manson Family. Even though she was present at both the Tate and LaBianca murders, because she was the key witness in District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi's prosecuti ...

, who was present during the Tate murders on August 8–9, 1969. Kasabian provided graphic testimony of the Tate murders, which she observed from outside the house. She was also in the car with Manson on the following evening, when, according to her testimony, he ordered the LaBianca killings. Kasabian spent days on the witness stand, being cross-examined by the defendants' lawyers. After testifying, Kasabian went into hiding for the next forty years.

In early August 1970, President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

told reporters that he believed that Manson was guilty of the murders, "either directly or indirectly". Manson obtained a copy of the newspaper and held up the headline to the jury. The defendants' attorneys then called for a mistrial, arguing that their clients had allegedly killed far fewer people than "Nixon's war machine in Vietnam". Judge Charles H. Older polled each member of the jury, to determine whether each juror saw the headline and whether it affected his or her ability to make an independent decision. All of the jurors affirmed that they could still decide independently. Shortly after, the female defendants – Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten – were removed from the room for chanting, "Nixon says we are guilty. So why go on?"

On October 5, 1970, Manson attempted to attack Judge Older while the jury was present in the room. Manson first threatened Older, and then jumped over his lawyer's table with a sharpened pencil, in the direction of Older. Manson was restrained before reaching the judge. While being led out of the courtroom, Manson screamed at Older, "In the name of Christian justice, someone should cut your head off!" Meanwhile, the female defendants began chanting something in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. Judge Older began wearing a .38 caliber

.38 caliber is a frequently used name for the caliber of firearms and firearm cartridges.

The .38 is considered a large firearm cartridge; anything larger than .32 is considered a large caliber.Wright, James D.; Rossi, Peter H.; Daly, Kathleen ...

pistol to the trial afterwards.

On November 16, 1970, the State of California rested its case after presenting twenty-two weeks worth of evidence. The defendants then stunned the courtroom by announcing that they had no witnesses to present, and rested their case.

Manson's testimony

Immediately after defendants' counsel rested their case, the three female defendants shouted that they wanted to testify. Their attorneys advised the court, in chambers, that they opposed their clients testifying. Apparently, the female defendants wanted to testify that Manson had had nothing to do with the murders. The following day, Manson himself announced that he too wanted to testify. The judge allowed Manson to testify outside the presence of the jury. He stated as follows: Manson continued, equating his actions to those of society at large: Manson concluded, claiming that he too was a creation of a system that he viewed as fundamentally violent and unjust: After Manson finished speaking, Judge Older offered to let him testify before the jury. Manson replied that it was not necessary. Manson then told the female defendants that they no longer needed to testify. On November 30, 1970, Leslie Van Houten's attorney, Ronald Hughes, failed to appear for the closing arguments in the trial. He was later found dead in a California state park. His body was badly decomposed, and it was impossible to tell the cause of death. Hughes had disagreed with Manson during the trial, taking the position that his client, Van Houten, should not testify to claim that Manson had no involvement with the murders. Some have alleged that Hughes was murdered by the Manson Family. On January 25, 1971, the jury found Manson, Krenwinkel and Atkins guilty of first degree murder in all seven of the Tate and LaBianca killings. The jury found Van Houten guilty of murder in the first degree in the LaBianca killings.Sentencing

After the convictions, the court held a separate hearing before the same jury to determine if the defendants should receive the death sentence. Each of the three female defendants – Atkins, Van Houten, and Krenwinkel – took the stand. They provided graphic details of the murders and testified that Manson was not involved. According to the female defendants, they had committed the crimes in order to help fellow Manson Family memberBobby Beausoleil

Robert Kenneth Beausoleil (born November 6, 1947) is an American murderer and associate of Charles Manson and members of his communal Manson Family. He was convicted and sentenced to death for the July 27, 1969 fatal stabbing of Gary Hinman, w ...

get out of jail, where he was being held for the murder of Gary Hinman. The female defendants testified that the Tate-LaBianca murders were intended to be copycat crime

A copycat crime is a criminal act that is modelled after or inspired by a previous crime. It notably occurs after exposure to media content depicted said crimes, and/or a live criminal model.

Copycat effect

The copycat effect is the alleged tende ...

s, similar to the Hinman killing. Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten claimed they did this under the direction of the state's prime witness, Linda Kasabian

Linda Darlene Kasabian (born Drouin; June 21, 1949) is a former member of the Manson Family. Even though she was present at both the Tate and LaBianca murders, because she was the key witness in District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi's prosecuti ...

. The defendants did not express remorse for the killings.

On March 4, 1971, during the sentencing hearings, Manson trimmed his beard to a fork and shaved his head, telling the media, "I am the Devil, and the Devil always has a bald head!" However, the female defendants did not immediately shave their own heads. The state prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, later speculated in his book, ''Helter Skelter'', that they refrained from doing so, in order to not appear to be completely controlled by Manson (as they had when they each carved an "X" in their foreheads, earlier in the trial).

On March 29, 1971, the jury sentenced all four defendants to death. When the female defendants were led into the courtroom, each of them had shaved their heads, as had Manson. After hearing the sentence, Atkins shouted to the jury, "Better lock your doors and watch your kids."

The Manson murder trial was the longest murder trial in American history when it occurred, lasting nine and a half months. The trial was among the most publicized American criminal cases of the twentieth century and was dubbed the "trial of the century

__NOTOC__

Trial of the century is an idiomatic phrase used to describe certain well-known court cases, especially of the 19th, 20th and 21st century. It is often used popularly as a rhetorical device to attach importance to a trial and as such i ...

". The jury had been sequestered for 225 days, longer than any jury before it. The trial transcript alone ran to 209 volumes or 31,716 pages.

1971–2017: Third imprisonment

Post-trial events

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. As the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, Manson was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His initial death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder in Los Angeles County Court for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman. He was also convicted of first-degree murder for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea. Following the 1972 decision of ''

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. As the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, Manson was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His initial death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder in Los Angeles County Court for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman. He was also convicted of first-degree murder for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea. Following the 1972 decision of ''California v. Anderson

''The People of the State of California v. Robert Page Anderson'', 493 P.2d 880, 6 Cal. 3d 628 ( Cal. 1972), was a landmark case in the state of California that outlawed capital punishment for nine months until the enactment of a constitutional ...

'', California's death sentences were ruled unconstitutional and that "any prisoner now under a sentence of death ... may file a petition for writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' in the superior court inviting that court to modify its judgment to provide for the appropriate alternative punishment of life imprisonment or life imprisonment without possibility of parole specified by statute for the crime for which he was sentenced to death." Manson was thus eligible to apply for parole after seven years' incarceration. His first parole hearing took place on November 16, 1978, at California Medical Facility in Vacaville, where his petition was rejected.

1980s–1990s

In the 1980s, Manson gave four interviews to the mainstream media. The first, recorded at

In the 1980s, Manson gave four interviews to the mainstream media. The first, recorded at California Medical Facility

California Medical Facility (CMF) is a male-only state prison medical facility located in the city of Vacaville, Solano County, California. It is older than California State Prison, Solano, the other state prison in Vacaville.

Facilities

CMF ...

and aired on June 13, 1981, was by Tom Snyder

Thomas James Snyder (May 12, 1936 – July 29, 2007) was an American television personality, news anchor, and radio personality best known for his late night talk shows '' Tomorrow'', on the NBC television network in the 1970s and 1980s, and '' ...

for NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an Television in the United States, American English-language Commercial broadcasting, commercial television network, broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Enterta ...

's ''The Tomorrow Show

''The Tomorrow Show'' (also known as ''Tomorrow with Tom Snyder'' or ''Tomorrow'' and, after 1980, ''Tomorrow Coast to Coast'') is an American late-night television talk show hosted by Tom Snyder which aired on NBC in first run form from October ...

''. The second, recorded at San Quentin State Prison

San Quentin State Prison (SQ) is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated place of San Quentin in Marin County.

Opened in July 1852, San Quentin is the ...

and aired on March 7, 1986, was by Charlie Rose

Charles Peete Rose Jr. (born January 5, 1942) is an American former television journalist and talk show host. From 1991 to 2017, he was the host and executive producer of the talk show '' Charlie Rose'' on PBS and Bloomberg LP.

Rose also co-an ...

for ''CBS News Nightwatch'', and it won the national news Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

for Best Interview in 1987.Joynt, Carol''Diary of a Mad Saloon Owner''

. April–May 2005. The third, with

Geraldo Rivera

Geraldo Rivera (born Gerald Riviera; July 4, 1943) is an American journalist, attorney, author, political commentator, and former television host. He hosted the tabloid talk show '' Geraldo'' from 1987 to 1998. He gained publicity with the liv ...

in 1988, was part of the journalist's prime-time special on Satanism

Satanism is a group of ideological and philosophical beliefs based on Satan. Contemporary religious practice of Satanism began with the founding of the atheistic Church of Satan by Anton LaVey in the United States in 1966, although a few hi ...

. At least as early as the Snyder interview, Manson's forehead bore a swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

in the spot where the X carved during his trial had been.

Nikolas Schreck

Nikolas Schreck is an American singer-songwriter, musician, author, film-maker and Tantric Buddhist religious teacher based in Berlin, Germany.

Now a solo artist, Schreck founded the musical magical recording and performance collective Radio ...

conducted an interview with Manson for his documentary ''Charles Manson Superstar

''Charles Manson Superstar'' is a documentary film about Charles Manson, directed by Nikolas Schreck in 1989.

Most of the documentary (the entire interview) was filmed inside San Quentin Prison. Nikolas and Zeena Schreck narrated the segments whil ...

'' (1989). Schreck concluded that Manson was not insane but merely acting that way out of frustration.

On September 25, 1984, Manson was imprisoned in the California Medical Facility

California Medical Facility (CMF) is a male-only state prison medical facility located in the city of Vacaville, Solano County, California. It is older than California State Prison, Solano, the other state prison in Vacaville.

Facilities

CMF ...

at Vacaville

Vacaville is a city located in Solano County in Northern California. Sitting approximately from Sacramento and from San Francisco, it is within the Sacramento Valley. As of the 2020 census, Vacaville had a population of 102,386, making it th ...

when inmate Jan Holmstrom poured paint thinner

A paint thinner is a solvent used to thin oil-based paints. Solvents labeled "paint thinner" are usually mineral spirits having a flash point at about 40 °C (104 °F), the same as some popular brands of charcoal starter.

Common solven ...

on him and set him on fire, causing second and third degree burns on over 20 percent of his body. Holmstrom explained that Manson had objected to his Hare Krishna

Hare Krishna may refer to:

* International Society for Krishna Consciousness

The International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), known Colloquialism, colloquially as the Hare Krishna movement or Hare Krishnas, is a Gaudiya Vaishnav ...

chants and verbally threatened him.

After 1989, Manson was housed in the Protective Housing Unit at California State Prison, Corcoran, in Kings County. The unit housed inmates whose safety would be endangered by general-population housing. He had also been housed at San Quentin State Prison, California Medical Facility in Vacaville, Folsom State Prison and Pelican Bay State Prison.

In June 1997, a prison disciplinary committee found that Manson had been trafficking drugs. He was moved from Corcoran State Prison to Pelican Bay State Prison

Pelican Bay State Prison (PBSP) is a supermax prison facility in Crescent City, California. The prison takes its name from a shallow bay on the Pacific coast, about to the west.

Facilities

The prison is located in a detached section of Cre ...

a month later.

2000s–2017

On September 5, 2007,

On September 5, 2007, MSNBC

MSNBC (originally the Microsoft National Broadcasting Company) is an American news-based pay television cable channel. It is owned by NBCUniversala subsidiary of Comcast. Headquartered in New York City, it provides news coverage and political ...

aired ''The Mind of Manson'', a complete version of a 1987 interview at California's San Quentin State Prison

San Quentin State Prison (SQ) is a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison for men, located north of San Francisco in the unincorporated place of San Quentin in Marin County.

Opened in July 1852, San Quentin is the ...

. The footage of the "unshackled, unapologetic, and unruly" Manson had been considered "so unbelievable" that only seven minutes of it had originally been broadcast on ''Today

Today (archaically to-day) may refer to:

* Day of the present, the time that is perceived directly, often called ''now''

* Current era, present

* The current calendar date

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Today'' (1930 film), a 1930 A ...

'', for which it had been recorded.

In March 2009, a photograph of Manson showing a receding hairline, grizzled gray beard and hair, and the swastika tattoo still prominent on his forehead was released to the public by California corrections officials.

In 2010, the ''Los Angeles Times'' reported that Manson was caught with a cell phone in 2009 and had contacted people in California, New Jersey, Florida and British Columbia. A spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections stated that it was not known if Manson had used the phone for criminal purposes. Manson also recorded an album of acoustic pop songs with additional production by Henry Rollins

Henry Lawrence Garfield (born February 13, 1961), known professionally as Henry Rollins, is an American singer, writer, spoken word artist, actor, and presenter. After performing in the short-lived hardcore punk band State of Alert in 1980, Rolli ...

, titled ''Completion''. Only five copies were pressed: two belong to Rollins, while the other three are presumed to have been with Manson. The album remains unreleased.

Illness and death

On January 1, 2017, Manson was being held at Corcoran Prison, when he was rushed to Mercy Hospital in downtown Bakersfield, because he had gastrointestinal bleeding. A source told the ''Los Angeles Times'' that Manson was very ill, and TMZ reported that his doctors considered him "too weak" for surgery that normally would be performed in cases such as his. He was returned to prison on January 6, and the nature of his treatment was not disclosed. On November 15, 2017, an unauthorized source said that Manson had returned to a hospital in Bakersfield, but the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation did not confirm this in conformity with state and federal medical privacy laws. He died from cardiac arrest resulting from respiratory failure, brought on bycolon cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel mo ...

, at the hospital on November 19.

Three people stated their intention to claim Manson's estate and body. Manson's grandson Jason Freeman stated his intent to take possession of Manson's remains and personal effects. Manson's pen-pal Michael Channels claimed to have a Manson will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

dated February 14, 2002, which left Manson's entire estate and Manson's body to Channels. Manson's friend Ben Gurecki claimed to have a Manson will dated January 2017 which gives the estate and Manson's body to Matthew Roberts, another alleged son of Manson. In 2012, CNN ran a DNA match to see if Freeman and Roberts were related to each other and found that they were not. According to CNN, two prior attempts to DNA match Roberts with genetic material from Manson failed, but the results were reportedly contaminated. On March 12, 2018, the Kern County Superior Court in California decided in favor of Freeman in regard to Manson's body. Freeman had Manson cremated on March 20, 2018. As of February 7, 2020, Channels and Freeman still had petitions to California courts attempting to establish the heir of Manson's estate. At that time, Channels was attempting to force Freeman to submit DNA to the court for testing.

Personal life

Involvement with Scientology

Manson began studying Scientology while incarcerated with the help of fellow inmate Lanier Rayner, and in July 1961, Manson listed his religion asScientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It has been variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religious movement. The most recent published census data indi ...

. A September 1961 prison report argues that Manson "appears to have developed a certain amount of insight into his problems through his study of this discipline". Upon his release in 1967, Manson traveled to Los Angeles where he reportedly "met local Scientologists and attended several parties for movie stars". Manson completed 150 hours of auditing

An audit is an "independent examination of financial information of any entity, whether profit oriented or not, irrespective of its size or legal form when such an examination is conducted with a view to express an opinion thereon.” Auditing ...

. Manson's "right hand man", Bruce M. Davis

Bruce McGregor Davis (born October 5, 1942) is a former member of the Manson Family who has been described as Charles Manson's "right-hand man".

Early life

Bruce Davis was born on October 5, 1942, in Monroe, Louisiana. Davis was editor of his ...

, worked at the Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is a group of interconnected corporate entities and other organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, which is variously defined as a cult, a scientology as a business, bu ...

headquarters in London from November 1968 to April 1969."

Relationships and alleged child

In 2009, Los Angeles disc jockey Matthew Roberts released correspondence and other evidence indicating that he might be Manson's biological son. Roberts' biological mother claims that she was a member of the Manson Family who left in mid-1967 after being raped by Manson; she returned to her parents' home to complete the pregnancy, gave birth on March 22, 1968, and put Roberts up for adoption. CNN conducted a DNA test between Matthew Roberts and Manson's known biological grandson Jason Freeman in 2012, showing that Roberts and Freeman did not share DNA. Roberts subsequently attempted to establish that Manson was his father through a direct DNA test which proved definitively that Roberts and Manson were not related. In 2014, the imprisoned Manson became engaged to 26-year-old Afton Elaine Burton and obtained a marriage license on November 7. Manson gave Burton the nickname "Star". She had been visiting him in prison for at least nine years and maintained several websites that proclaimed his innocence. The wedding license expired on February 5, 2015, without a marriage ceremony taking place. Journalist Daniel Simone reported that the wedding was canceled after Manson discovered that Burton wanted to marry him only so that she and friend Craig Hammond could use his corpse as a tourist attraction after his death. According to Simone, Manson believed that he would never die and may simply have used the possibility of marriage as a way to encourage Burton and Hammond to continue visiting him and bringing him gifts. Burton said on her website that the reason that the marriage did not take place was merely logistical. Manson had an infection and had been in a prison medical facility for two months and could not receive visitors. She said that she still hoped that the marriage license would be renewed and the marriage would take place.Psychology

On April 11, 2012, Manson was denied release at his 12th parole hearing, which he did not attend. After his March 27, 1997, parole hearing, Manson refused to attend any of his later hearings. The panel at that hearing noted that Manson had a "history ofcontrolling behavior

Control may refer to:

Basic meanings Economics and business

* Control (management), an element of management

* Control, an element of management accounting

* Comptroller (or controller), a senior financial officer in an organization

* Controlling ...

" and "mental health issues" including schizophrenia and paranoid delusional disorder, and was too great a danger to be released. The panel also noted that Manson had received 108 rules violation reports, had no indication of remorse, no insight into the causative factors of the crimes, lacked understanding of the magnitude of the crimes, had an exceptional, callous disregard for human suffering and had no parole plans. At the April 11, 2012, parole hearing, it was determined that Manson would not be reconsidered for parole for another 15 years, i.e. not before 2027, at which time he would have been 92 years old.

Legacy

Cultural impact

In June 1970, ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner, and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason. It was first kno ...

'' made Manson their cover story. Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Rae Dohrn (née Ohrnstein; born January 12, 1942) is a retired law professor and a former leader of the left-wing radical group Weather Underground in the United States. As a leader of the Weather Underground in the early 1970s, Dohrn w ...

of the Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a Far-left politics, far-left militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor, Michigan, Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, the group was organiz ...

reportedly said of the Tate murders: "Dig it, first they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, then they even shoved a fork into a victim's stomach. Wild!" Manson fanatic James Mason

James Neville Mason (; 15 May 190927 July 1984) was an English actor. He achieved considerable success in British cinema before becoming a star in Hollywood. He was the top box-office attraction in the UK in 1944 and 1945; his British films inc ...

claimed to be acting on a suggestion from Charles Manson based on his interpretation of something Manson said in a televised interview, when Mason founded the Universal Order, a neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

group that has influenced other movements such as the terrorist group the Atomwaffen Division

The Atomwaffen Division (''Atomwaffen'' meaning "nuclear weapons" in German), also known as the National Socialist Resistance Front, is an international far right-wing extremist and neo-Nazi terrorist network. Formed in 2013 and based in the ...

. Bugliosi quoted a BBC employee's assertion that a "neo-Manson cult" existed in Europe, represented by approximately 70 rock bands playing songs by Manson and "songs in support of him".

Music

Manson was a struggling musician, seeking to make it big in Hollywood between 1967 and 1969. TheBeach Boys

A beach is a landform alongside a body of water which consists of loose particles. The particles composing a beach are typically made from rock, such as sand, gravel, shingle, pebbles, etc., or biological sources, such as mollusc shell ...

did a cover of one of his songs. Other songs were publicly released only after the trial for the Tate murders started. On March 6, 1970, ''LIE

A lie is an assertion that is believed to be false, typically used with the purpose of deceiving or misleading someone. The practice of communicating lies is called lying. A person who communicates a lie may be termed a liar. Lies can be inter ...