Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of

silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized Sound recording and reproduction, recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) ...

. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona,

the Tramp

The Tramp (''Charlot'' in several languages), also known as the Little Tramp, was English actor Charlie Chaplin's most memorable on-screen character and an icon in world cinema during the era of silent film. '' The Tramp'' is also the title ...

, and is considered one of the film industry's most important figures. His career spanned more than 75 years, from childhood in the Victorian era until a year before his death in 1977, and encompassed both adulation and controversy.

Chaplin's childhood in London was one of poverty and hardship. His father was absent and his mother struggled financially — he was sent to a

workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

twice before age nine. When he was 14, his mother was committed to a

mental asylum. Chaplin began performing at an early age, touring

music halls and later working as a stage actor and comedian. At 19, he was signed to the

Fred Karno

Frederick John Westcott (26 March 1866 – 17 September 1941), best known by his stage name Fred Karno, was an English theatre impresario of the British music hall. As a comedian of slapstick he is credited with popularising the custar ...

company, which took him to the United States. He was scouted for the film industry and began appearing in 1914 for

Keystone Studios

Keystone Studios was an early film studio founded in Edendale, California (which is now a part of Echo Park) on July 4, 1912 as the Keystone Pictures Studio by Mack Sennett with backing from actor-writer Adam Kessel (1866–1946) and Cha ...

. He soon developed the Tramp persona and attracted a large fan base. He directed his own films and continued to hone his craft as he moved to the

Essanay,

Mutual, and

First National corporations. By 1918, he was one of the world's best-known figures.

In 1919, Chaplin co-founded distribution company

United Artists

United Artists Corporation (UA), currently doing business as United Artists Digital Studios, is an American digital production company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the stu ...

, which gave him complete control over his films. His first feature-length film was ''

The Kid'' (1921), followed by ''

A Woman of Paris

''A Woman of Paris'' is a feature-length American silent film that debuted in 1923. The film, an atypical drama film for its creator, was written, directed, produced and later scored by Charlie Chaplin. It is also known as ''A Woman of Paris: A ...

'' (1923), ''

The Gold Rush

''The Gold Rush'' is a 1925 American silent comedy film written, produced, and directed by Charlie Chaplin. The film also stars Chaplin in his Little Tramp persona, Georgia Hale, Mack Swain, Tom Murray, Henry Bergman, and Malcolm Waite.

Ch ...

'' (1925), and ''

The Circus'' (1928). He initially refused to move to sound films in the 1930s, instead producing ''

City Lights'' (1931) and ''

Modern Times'' (1936) without dialogue. His first

sound film

A sound film is a motion picture with synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, but decades passed befo ...

was ''

The Great Dictator

''The Great Dictator'' is a 1940 American anti-war political satire black comedy film written, directed, produced, scored by, and starring British comedian Charlie Chaplin, following the tradition of many of his other films. Having been the ...

'' (1940), which satirised

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. The 1940s were marked with controversy for Chaplin, and his popularity declined rapidly. He was accused of

communist sympathies, and some members of the press and public were scandalised by his involvement in a paternity suit and marriages to much younger women. An

FBI investigation was opened, and Chaplin was forced to leave the U.S. and settle in Switzerland. He abandoned the Tramp in his later films, which include ''

Monsieur Verdoux'' (1947), ''

Limelight

Limelight (also known as Drummond light or calcium light)James R. Smith (2004). ''San Francisco's Lost Landmarks'', Quill Driver Books. is a type of stage lighting once used in theatres and music halls. An intense illumination is created w ...

'' (1952), ''

A King in New York'' (1957), and ''

A Countess from Hong Kong'' (1967).

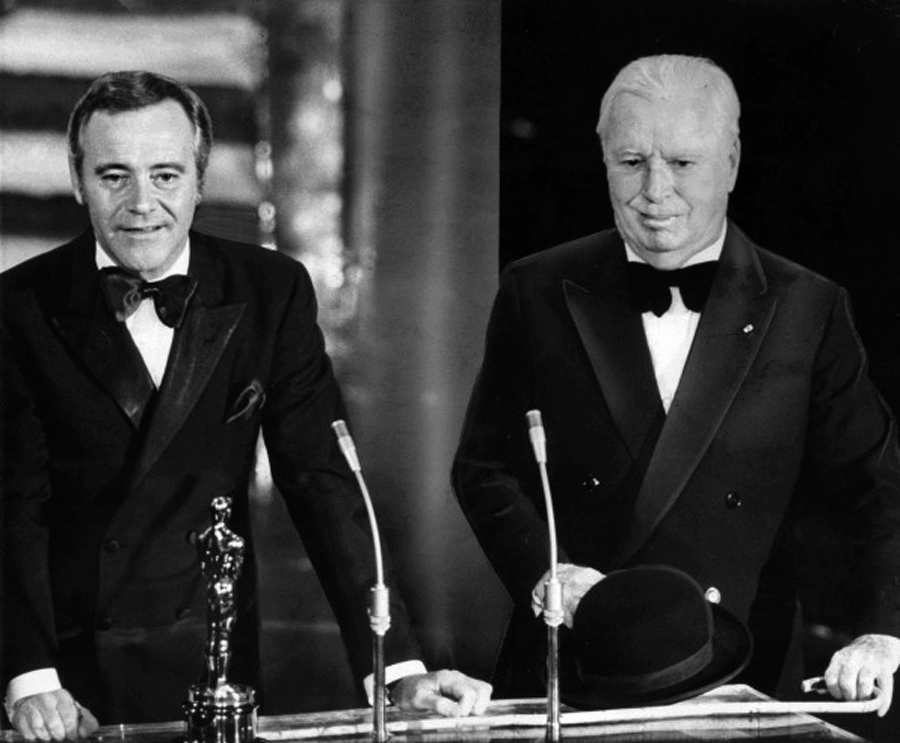

Chaplin wrote, directed, produced, edited, starred in, and composed the music for most of his films. He was a perfectionist, and his financial independence enabled him to spend years on the development and production of a picture. His films are characterised by slapstick combined with pathos, typified in the Tramp's struggles against adversity. Many contain social and political themes, as well as autobiographical elements. He received an Honorary Academy Award for "the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century" in 1972, as part of a renewed appreciation for his work. He continues to be held in high regard, with ''The Gold Rush'', ''City Lights'', ''Modern Times'', and ''The Great Dictator'' often ranked on lists of the

greatest films.

Biography

1889–1913: early years

Background and childhood hardship

Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. was born on 16 April 1889 to

Hannah Chaplin (née Hill) and

Charles Chaplin Sr.

Charles Spencer Chaplin Sr. (18 March 1863 – 9 May 1901) was an English music hall entertainer. He achieved considerable success in the 1890s, and was the father of the actor and filmmaker Sir Charlie Chaplin.

Early years

Chaplin was born ...

His paternal grandmother came from the Smith family, who belonged to

Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

. There is no official record of his birth, although Chaplin believed he was born at

East Street,

Walworth

Walworth () is a district of south London, England, within the London Borough of Southwark. It adjoins Camberwell to the south and Elephant and Castle to the north, and is south-east of Charing Cross.

Major streets in Walworth include the ...

, in

South London

South London is the southern part of London, England, south of the River Thames. The region consists of the boroughs, in whole or in part, of Bexley, Bromley, Croydon, Greenwich, Kingston, Lambeth, Lewisham, Merton, Richmond, Southwark, ...

. His parents had married four years previously, at which time Charles Sr. became the legal guardian of Hannah's first son,

Sydney John Hill. At the time of his birth, Chaplin's parents were both

music hall entertainers. Hannah, the daughter of a shoemaker, had a brief and unsuccessful career under the stage name Lily Harley, while Charles Sr., a butcher's son, was a popular singer. Although they never divorced, Chaplin's parents were estranged by around 1891. The following year, Hannah gave birth to a third son,

George Wheeler Dryden, fathered by the music hall entertainer

Leo Dryden. The child was taken by Dryden at six months old, and did not re-enter Chaplin's life for thirty years.

Chaplin's childhood was fraught with poverty and hardship, making his eventual trajectory "the most dramatic of all the rags to riches stories ever told" according to his authorised biographer

David Robinson. Chaplin's early years were spent with his mother and brother Sydney in the London district of

Kennington

Kennington is a district in south London, England. It is mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth, running along the boundary with the London Borough of Southwark, a boundary which can be discerned from the early medieval period between the ...

. Hannah had no means of income, other than occasional nursing and dressmaking, and Chaplin Sr. provided no financial support. As the situation deteriorated, Chaplin was sent to

Lambeth Workhouse

The Lambeth Workhouse was a workhouse in Lambeth, London. The original workhouse opened in 1726 in Princes Road (later, Black Prince Road). From 1871 to 1873 a new building was constructed in Renfrew Road, Lambeth. The building was eventually turne ...

when he was seven years old. The council housed him at the

Central London District School

Cuckoo Schools was a large school for children of destitute families which was created as the Central London District Poor Law School by the City of London and the East London and St. Saviour Workhouse Unions in 1857. It was built on the land of ...

for

paupers, which Chaplin remembered as "a forlorn existence". He was briefly reunited with his mother 18 months later, before Hannah was forced to readmit her family to the workhouse in July 1898. The boys were promptly sent to

Norwood Schools, another institution for destitute children.

In September 1898, Hannah was committed to

Cane Hill mental asylum; she had developed a

psychosis

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior ...

seemingly brought on by an infection of

syphilis and malnutrition. For the two months she was there, Chaplin and his brother Sydney were sent to live with their father, whom the young boys scarcely knew. Charles Sr. was by then a severe alcoholic, and life there was bad enough to provoke a visit from the

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) is a British child protection charity.

History

Victorian era

On a trip to New York in 1881, Liverpudlian businessman Thomas Agnew was inspired by a visit to the New Y ...

. Chaplin's father died two years later, at 38 years old, from

cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, and end-stage liver disease, is the impaired liver function caused by the formation of scar tissue known as fibrosis due to damage caused by liver disease. Damage causes tissue repai ...

of the liver.

Hannah entered a period of remission but, in May 1903, became ill again. Chaplin, then 14, had the task of taking his mother to the infirmary, from where she was sent back to Cane Hill. He lived alone for several days, searching for food and occasionally sleeping rough, until Sydneywho had joined the Navy two years earlierreturned. Hannah was released from the asylum eight months later, but in March 1905, her illness returned, this time permanently. "There was nothing we could do but accept poor mother's fate", Chaplin later wrote, and she remained in care until her death in 1928.

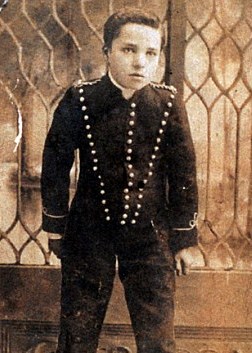

Young performer

Between his time in the poor schools and his mother succumbing to mental illness, Chaplin began to perform on stage. He later recalled making his first amateur appearance at the age of five years, when he took over from Hannah one night in

Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alde ...

. This was an isolated occurrence, but by the time he was nine Chaplin had, with his mother's encouragement, grown interested in performing. He later wrote: "

heimbued me with the feeling that I had some sort of talent". Through his father's connections, Chaplin became a member of the

Eight Lancashire Lads clog-dancing Clog dancing is dancing whilst wearing clogs. The rigid nature of the clogs and their percussive sound when dancing on a hard surface has given rise to a number of distinct styles, including the following: Dance

* Clog dancing, a Welsh and Northern ...

troupe, with whom he toured English music halls throughout 1899 and 1900. Chaplin worked hard, and the act was popular with audiences, but he was not satisfied with dancing and wished to form a comedy act.

In the years Chaplin was touring with the Eight Lancashire Lads, his mother ensured that he still attended school but, by age 13, he had abandoned education. He supported himself with a range of jobs, while nursing his ambition to become an actor. At 14, shortly after his mother's relapse, he registered with a theatrical agency in London's

West End

West End most commonly refers to:

* West End of London, an area of central London, England

* West End theatre, a popular term for mainstream professional theatre staged in the large theatres of London, England

West End may also refer to:

Pl ...

. The manager sensed potential in Chaplin, who was promptly given his first role as a newsboy in

Harry Arthur Saintsbury's ''Jim, a Romance of Cockayne''. It opened in July 1903, but the show was unsuccessful and closed after two weeks. Chaplin's comic performance, however, was singled out for praise in many of the reviews.

Saintsbury secured a role for Chaplin in

Charles Frohman's production of ''

Sherlock Holmes'', where he played Billy the pageboy in three nationwide tours. His performance was so well received that he was called to London to play the role alongside

William Gillette, the original Holmes. "It was like tidings from heaven", Chaplin recalled. At 16 years old, Chaplin starred in the play's West End production at the

Duke of York's Theatre from October to December 1905. He completed one final tour of ''Sherlock Holmes'' in early 1906, before leaving the play after more than two-and-a-half years.

Stage comedy and vaudeville

Chaplin soon found work with a new company and went on tour with his brother, who was also pursuing an acting career, in a

comedy sketch called ''Repairs''. In May 1906, Chaplin joined the juvenile act Casey's Circus, where he developed popular

burlesque

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. pieces and was soon the star of the show. By the time the act finished touring in July 1907, the 18-year-old had become an accomplished comedic performer. He struggled to find more work, however, and a brief attempt at a solo act was a failure.

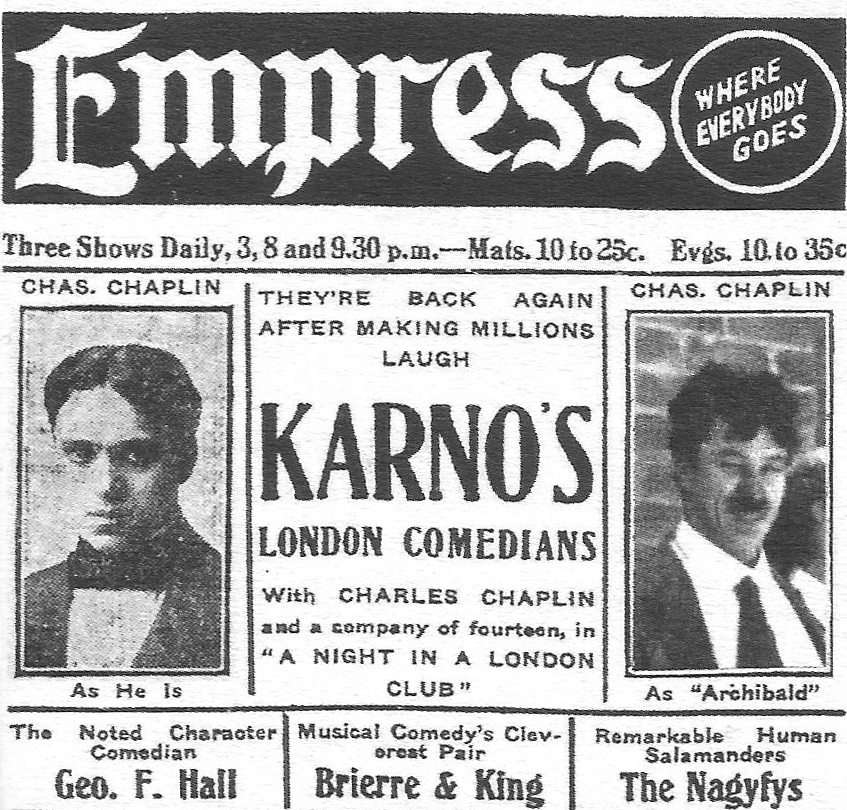

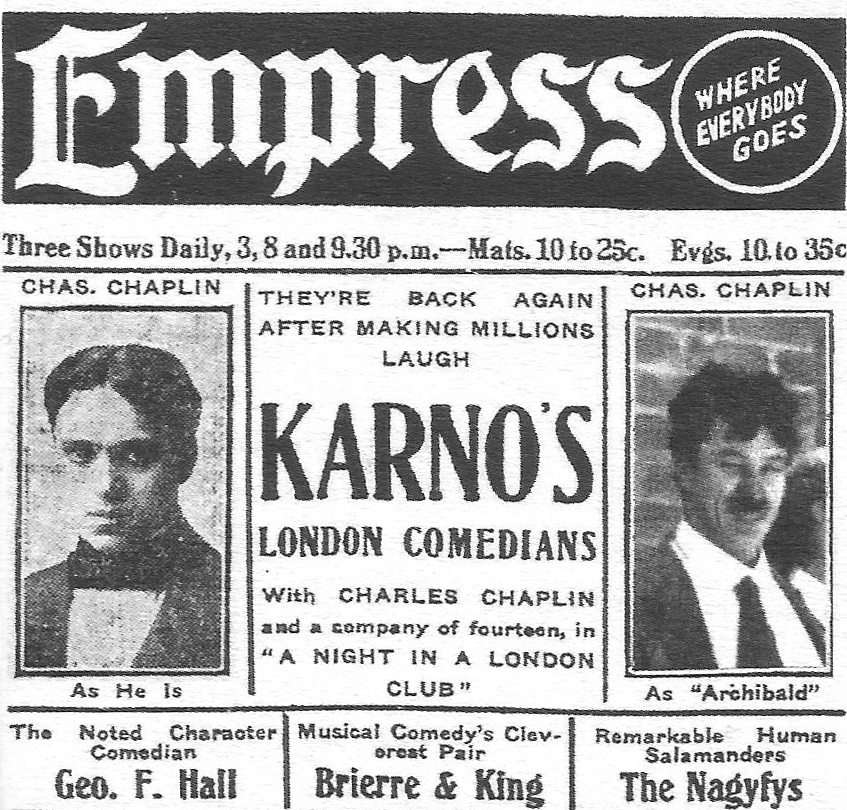

Meanwhile, Sydney Chaplin had joined

Fred Karno

Frederick John Westcott (26 March 1866 – 17 September 1941), best known by his stage name Fred Karno, was an English theatre impresario of the British music hall. As a comedian of slapstick he is credited with popularising the custar ...

's prestigious comedy company in 1906 and, by 1908, he was one of their key performers. In February, he managed to secure a two-week trial for his younger brother. Karno was initially wary, and considered Chaplin a "pale, puny, sullen-looking youngster" who "looked much too shy to do any good in the theatre". However, the teenager made an impact on his first night at the

London Coliseum

The London Coliseum (also known as the Coliseum Theatre) is a theatre in St Martin's Lane, Westminster, built as one of London's largest and most luxurious "family" variety theatres. Opened on 24 December 1904 as the London Coliseum Theatre ...

and he was quickly signed to a contract. Chaplin began by playing a series of minor parts, eventually progressing to starring roles in 1909. In April 1910, he was given the lead in a new sketch, ''Jimmy the Fearless''. It was a big success, and Chaplin received considerable press attention.

Karno selected his new star to join the section of the company, one that also included

Stan Laurel

Stan Laurel (born Arthur Stanley Jefferson; 16 June 1890 – 23 February 1965) was an English comic actor, writer, and film director who was one half of the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy. He appeared with his comedy partner Oliver Hardy in 107 s ...

, that toured North America's

vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic compositio ...

circuit.

The young comedian headed the show and impressed reviewers, being described as "one of the best pantomime artists ever seen here". His most successful role was a drunk called the "Inebriate Swell", which drew him significant recognition. The tour lasted 21 months, and the troupe returned to England in June 1912. Chaplin recalled that he "had a disquieting feeling of sinking back into a depressing commonplaceness" and was, therefore, delighted when a new tour began in October.

1914–1917: entering films

Keystone

Six months into the second American tour, Chaplin was invited to join the New York Motion Picture Company. A representative who had seen his performances thought he could replace

Fred Mace, a star of their

Keystone Studios

Keystone Studios was an early film studio founded in Edendale, California (which is now a part of Echo Park) on July 4, 1912 as the Keystone Pictures Studio by Mack Sennett with backing from actor-writer Adam Kessel (1866–1946) and Cha ...

who intended to leave. Chaplin thought the Keystone comedies "a crude mélange of rough and rumble", but liked the idea of working in films and rationalised: "Besides, it would mean a new life." He met with the company and signed a $150-per-week contract in September 1913. Chaplin arrived in Los Angeles in early December, and began working for the Keystone studio on 5January 1914.

Chaplin's boss was

Mack Sennett

Mack Sennett (born Michael Sinnott; January 17, 1880 – November 5, 1960) was a Canadian-American film actor, director, and producer, and studio head, known as the 'King of Comedy'.

Born in Danville, Quebec, in 1880, he started in films in th ...

, who initially expressed concern that the 24-year-old looked too young. He was not used in a picture until late January, during which time Chaplin attempted to learn the processes of filmmaking. The

one-reeler ''

Making a Living'' marked his film acting debut and was released on 2February 1914. Chaplin strongly disliked the picture, but one review picked him out as "a comedian of the first water". For his second appearance in front of the camera, Chaplin selected the costume with which he became identified. He described the process in his autobiography:

The film was ''

Mabel's Strange Predicament'', but "

the Tramp

The Tramp (''Charlot'' in several languages), also known as the Little Tramp, was English actor Charlie Chaplin's most memorable on-screen character and an icon in world cinema during the era of silent film. '' The Tramp'' is also the title ...

" character, as it became known, debuted to audiences in ''

Kid Auto Races at Venice

''Kid Auto Races at Venice'' (also known as ''The Pest'') is a 1914 American film starring Charles Chaplin. It is the first film in which his "Little Tramp" character makes an appearance before the public. The first film to be produced that featur ...

''shot later than ''Mabel's Strange Predicament'' but released two days earlier on 7February 1914.

Chaplin adopted the character as his screen persona and attempted to make suggestions for the films he appeared in. These ideas were dismissed by his directors. During the filming of his 11th picture, ''

Mabel at the Wheel'', he clashed with director

Mabel Normand

Amabel Ethelreid Normand (November 9, 1893 – February 23, 1930), better known as Mabel Normand, was an American silent film actress, screenwriter, director, and producer. She was a popular star and collaborator of Mack Sennett in their K ...

and was almost released from his contract. Sennett kept him on, however, when he received orders from exhibitors for more Chaplin films. Sennett also allowed Chaplin to direct his next film himself after Chaplin promised to pay $1,500 ($ in dollars) if the film was unsuccessful.

''

Caught in the Rain'', issued 4May 1914, was Chaplin's directorial debut and was highly successful. Thereafter he directed almost every short film in which he appeared for Keystone, at the rate of approximately one per week, a period which he later remembered as the most exciting time of his career. Chaplin's films introduced a slower form of comedy than the typical Keystone farce, and he developed a large fan base. In November 1914, he had a supporting role in the first

feature length

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

comedy film, ''

Tillie's Punctured Romance'', directed by Sennett and starring

Marie Dressler

Marie Dressler (born Leila Marie Koerber, November 9, 1868 – July 28, 1934) was a Canadian stage and screen actress, comedian, and early silent film and Great Depression, Depression-era film star. In 1914, she was in the first full-lengt ...

, which was a commercial success and increased his popularity. When Chaplin's contract came up for renewal at the end of the year, he asked for $1,000 a week an amount Sennett refused as too large.

Essanay

The

Essanay Film Manufacturing Company

The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company was an early American motion picture studio. The studio was founded in 1907 in Chicago, and later developed an additional film lot in Niles Canyon, California. Its various stars included Francis X. Bushman, ...

of Chicago sent Chaplin an offer of $1,250 a week with a signing bonus of $10,000. He joined the studio in late December 1914, where he began forming a stock company of regular players, actors he worked with again and again, including

Ben Turpin

Bernard "Ben" Turpin (September 19, 1869 – July 1, 1940) was an American comedian and actor, best remembered for his work in silent films. His trademarks were his cross-eyed appearance and adeptness at vigorous physical comedy. Turpin wo ...

,

Leo White

Leo White (November 10, 1882 – September 20, 1948), Leo Weiss, was a German-born British-American film and stage actor who appeared as a character actor in many Charlie Chaplin films.

Biography

Born in Germany, White grew up in England where ...

,

Bud Jamison,

Paddy McGuire

Paddy McGuire (né McQuire, 1884 - November 16, 1923) was an Irish actor and comedian.

Biography

Paddy McQuire was born in Ireland in 1884 or 1885. A burlesque comedian with a rubber face, McQuire was a regular supporting player in the films ...

,

Fred Goodwins

Fred Goodwins (26 February 1891 – April 1923) was an English actor, film director and screenwriter of the silent era. He appeared in 24 films between 1915 and 1921.He most notably worked with Charlie Chaplin during Chaplin's mutual perio ...

, and

Billy Armstrong. He soon recruited a leading lady,

Edna Purviance, whom Chaplin met in a café and hired on account of her beauty. She went on to appear in 35 films with Chaplin over eight years; the pair also formed a romantic relationship that lasted into 1917.

Chaplin asserted a high level of control over his pictures and started to put more time and care into each film. There was a month-long interval between the release of his second production, ''

A Night Out'', and his third, ''

The Champion

A champion is a first-place winner in a competition, along with other definitions discussed in the article.

Champion or Champions may also refer to:

Brands and enterprises

* Champion (sportswear), a clothing manufacturer

* Champion (spark p ...

''. The final seven of Chaplin's 14 Essanay films were all produced at this slower pace. Chaplin also began to alter his screen persona, which had attracted some criticism at Keystone for its "mean, crude, and brutish" nature. The character became more gentle and romantic; ''

The Tramp

The Tramp (''Charlot'' in several languages), also known as the Little Tramp, was English actor Charlie Chaplin's most memorable on-screen character and an icon in world cinema during the era of silent film. '' The Tramp'' is also the title ...

'' (April 1915) was considered a particular turning point in his development. The use of pathos was developed further with ''

The Bank'', in which Chaplin created a sad ending. Robinson notes that this was an innovation in comedy films, and marked the time when serious critics began to appreciate Chaplin's work. At Essanay, writes film scholar

Simon Louvish

Simon Louvish (born 6 April 1947, Glasgow, Scotland) is a Scots-born Israeli author, writer and filmmaker. He has written many books about ''Avram Blok'', a fictional Israeli caught up between wars, espionage, prophets, revolutions, loves, and ...

, Chaplin "found the themes and the settings that would define the Tramp's world".

During 1915, Chaplin became a cultural phenomenon. Shops were stocked with Chaplin merchandise, he was featured in cartoons and

comic strips

A comic strip is a Comics, sequence of drawings, often cartoons, arranged in interrelated panels to display brief humor or form a narrative, often Serial (literature), serialized, with text in Speech balloon, balloons and Glossary of comics ter ...

, and several songs were written about him. In July, a journalist for ''

Motion Picture Magazine

''Motion Picture'' was an American monthly fan magazine about film, published from 1911 to 1977.Fuller, Kathryn H. “Motion Picture Story Magazine and the Gendered Construction of the Movie Fan.” ''At the Picture Show: Small-Town Audiences ...

'' wrote that "Chaplinitis" had spread across America. As his fame grew worldwide, he became the film industry's first international star. When the Essanay contract ended in December 1915, Chaplin, fully aware of his popularity, requested a $150,000 signing bonus from his next studio. He received several offers, including

Universal,

Fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelv ...

, and

Vitagraph

Vitagraph Studios, also known as the Vitagraph Company of America, was a United States motion picture studio. It was founded by J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith in 1897 in Brooklyn, New York, as the American Vitagraph Company. By 1907 ...

, the best of which came from the

Mutual Film

Mutual Film Corporation was an early American film conglomerate that produced some of Charlie Chaplin's greatest comedies. Founded in 1912, it was absorbed by Film Booking Offices of America, which evolved into RKO Pictures.

Founding

Mutua ...

Corporation at $10,000 a week.

Mutual

A contract was negotiated with Mutual that amounted to $670,000 a year, which Robinson says made Chaplinat 26 years oldone of the highest paid people in the world. The high salary shocked the public and was widely reported in the press. John R. Freuler, the studio president, explained: "We can afford to pay Mr. Chaplin this large sum annually because the public wants Chaplin and will pay for him."

Mutual gave Chaplin his own Los Angeles studio to work in, which opened in March 1916. He added two key members to his stock company,

Albert Austin and

Eric Campbell, and produced a series of elaborate two-reelers: ''

The Floorwalker'', ''

The Fireman'', ''

The Vagabond'', ''

One A.M.'', and ''

The Count

Count (or Countess) is a title of nobility.

Count or The Count may also refer to:

People

''Used as a nickname, not denoting nobility'' Music

* The Count, a performance name for English deejay Hervé

* Count Basie (1904–1984), American jazz mus ...

''. For ''

The Pawnshop'', he recruited the actor

Henry Bergman

Henry Bergman (February 23, 1868 – October 22, 1946) was an American actor of stage and film, known for his long association with Charlie Chaplin.

Biography

Born in San Francisco, California, Bergman acted in live theatre, appearing in ''Hen ...

, who was to work with Chaplin for 30 years. ''

Behind the Screen'' and ''

The Rink'' completed Chaplin's releases for 1916. The Mutual contract stipulated that he release a two-reel film every four weeks, which he had managed to achieve. With the new year, however, Chaplin began to demand more time. He made only four more films for Mutual over the first ten months of 1917: ''

Easy Street

Easy Street may refer to:

Film

* ''Easy Street'' (1917 film), a Charlie Chaplin comedy

* Easy Street (1930 film), by Oscar Micheaux, US

* ''Easy Street'' (TV series), 1986–87 US sitcom

Music

*Easy Street (band), UK, 1970s

**''Easy Street'', ...

'', ''

The Cure

The Cure are an English rock band formed in 1978 in Crawley, West Sussex. Throughout numerous lineup changes since the band's formation, guitarist, lead vocalist, and songwriter Robert Smith has remained the only constant member. The band's ...

'', ''

The Immigrant'', and ''

The Adventurer''. With their careful construction, these films are considered by Chaplin scholars to be among his finest work. Later in life, Chaplin referred to his Mutual years as the happiest period of his career. However, Chaplin also felt that those films became increasingly formulaic over the period of the contract, and he was increasingly dissatisfied with the working conditions encouraging that.

Chaplin was attacked in the British media for not fighting in the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

. He defended himself, claiming that he would fight for Britain if called and had registered for the American draft, but he was not summoned by either country. Despite this criticism Chaplin was a favourite with the troops, and his popularity continued to grow worldwide. ''

Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' reported that the name of Charlie Chaplin was "a part of the common language of almost every country", and that the Tramp image was "universally familiar". In 1917, professional Chaplin imitators were so widespread that he took legal action, and it was reported that nine out of ten men who attended costume parties, did so dressed as the Tramp. The same year, a study by the

Boston Society for Psychical Research concluded that Chaplin was "an American obsession". The actress

Minnie Maddern Fiske wrote that "a constantly increasing body of cultured, artistic people are beginning to regard the young English buffoon, Charles Chaplin, as an extraordinary artist, as well as a comic genius".

1918–1922: First National

In January 1918, Chaplin was visited by leading British singer and comedian

Harry Lauder, and the two acted in a short film together.

Mutual was patient with Chaplin's decreased rate of output, and the contract ended amicably. With his aforementioned concern about the declining quality of his films because of contract scheduling stipulations, Chaplin's primary concern in finding a new distributor was independence; Sydney Chaplin, then his business manager, told the press, "Charlie

ustbe allowed all the time he needs and all the money for producing

ilmsthe way he wants... It is quality, not quantity, we are after." In June 1917, Chaplin signed to complete eight films for

First National Exhibitors' Circuit in return for $1million. He chose to build his own studio, situated on five acres of land off

Sunset Boulevard, with production facilities of the highest order. It was completed in January 1918, and Chaplin was given freedom over the making of his pictures.

''

A Dog's Life'', released April 1918, was the first film under the new contract. In it, Chaplin demonstrated his increasing concern with story construction and his treatment of the Tramp as "a sort of

Pierrot

Pierrot ( , , ) is a stock character of pantomime and ''commedia dell'arte'', whose origins are in the late seventeenth-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne. The name is a diminutive of ''P ...

". The film was described by

Louis Delluc as "cinema's first total work of art". Chaplin then embarked on the

Third Liberty Bond campaign, touring the United States for one month to raise money for the Allies of the First World War. He also produced a short propaganda film at his own expense, donated to the government for fund-raising, called ''

The Bond''. Chaplin's next release was war-based, placing the Tramp in the trenches for ''

Shoulder Arms''. Associates warned him against making a comedy about the war but, as he later recalled: "Dangerous or not, the idea excited me." He spent four months filming the picture, which was released in October 1918 with great success.

United Artists, Mildred Harris, and ''The Kid''

After the release of ''Shoulder Arms'', Chaplin requested more money from First National, which was refused. Frustrated with their lack of concern for quality, and worried about rumours of a possible merger between the company and

Famous Players-Lasky

Famous Players-Lasky Corporation was an American motion picture and distribution company formed on June 28, 1916, from the merger of Adolph Zukor's Famous Players Film Company—originally formed by Zukor as Famous Players in Famous Plays—and t ...

, Chaplin joined forces with

Douglas Fairbanks

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Sr. (born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman; May 23, 1883 – December 12, 1939) was an American actor, screenwriter, director, and producer. He was best known for his swashbuckling roles in silent films including '' The Thi ...

,

Mary Pickford

Gladys Marie Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian-American stage and screen actress and producer with a career that spanned five decades. A pioneer in the US film industry, she co-founde ...

, and

D. W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the na ...

to form a new distribution company,

United Artists

United Artists Corporation (UA), currently doing business as United Artists Digital Studios, is an American digital production company. Founded in 1919 by D. W. Griffith, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks, the stu ...

, in January 1919. The arrangement was revolutionary in the film industry, as it enabled the four partnersall creative artiststo personally fund their pictures and have complete control. Chaplin was eager to start with the new company and offered to buy out his contract with First National. They refused and insisted that he complete the final six films owed.

Before the creation of United Artists, Chaplin married for the first time. The 16-year-old actress

Mildred Harris had revealed that she was pregnant with his child, and in September 1918, he married her quietly in Los Angeles to avoid controversy. Soon after, the pregnancy was found to be false. Chaplin was unhappy with the union and, feeling that marriage stunted his creativity, struggled over the production of his film ''

Sunnyside''. Harris was by then legitimately pregnant, and on 7July 1919, gave birth to a son. Norman Spencer Chaplin was born malformed and died three days later. The marriage ended in April 1920, with Chaplin explaining in his autobiography that they were "irreconcilably mismated".

Losing the child, plus his own childhood experiences, are thought to have influenced Chaplin's next film, which turned the Tramp into the caretaker of a young boy.

For this new venture, Chaplin also wished to do more than comedy and, according to Louvish, "make his mark on a changed world". Filming on ''

The Kid'' began in August 1919, with four-year-old

Jackie Coogan his co-star. ''The Kid'' was in production for nine months until May 1920 and, at 68 minutes, it was Chaplin's longest picture to date. Dealing with issues of poverty and parent–child separation, ''The Kid'' was one of the earliest films to combine comedy and drama. It was released in January 1921 with instant success, and, by 1924, had been screened in over 50 countries.

Chaplin spent five months on his next film, the two-reeler ''

The Idle Class''. Work on the picture was for a time delayed by more turmoil in his personal life. First National had on 12 April announced Chaplin's engagement to the actress

May Collins, whom he had hired to be his secretary at the studio. By early June, however, Chaplin "suddenly decided he could scarcely stand to be in the same room" as Collins, but instead of breaking off the engagement directly, he "stopped coming in to work, sending word that he was suffering from a bad case of influenza, which May knew to be a lie."

Ultimately work on the film resumed, and following its September 1921 release, Chaplin chose to return to England for the first time in almost a decade. He wrote a book about his journey, titled ''My Wonderful Visit''. He then worked to fulfil his First National contract, releasing ''

Pay Day'' in February 1922. ''

The Pilgrim

A pilgrim is one who undertakes a religious journey or pilgrimage.

Pilgrim(s) or The Pilgrim(s) may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film, television, radio and the stage

* The Pilgrim (1923 film), ''The Pilgrim'' (1923 film), a si ...

'', his final short film, was delayed by distribution disagreements with the studio and released a year later.

1923–1938: silent features

''A Woman of Paris'' and ''The Gold Rush''

Having fulfilled his First National contract, Chaplin was free to make his first picture as an independent producer. In November 1922, he began filming ''

A Woman of Paris

''A Woman of Paris'' is a feature-length American silent film that debuted in 1923. The film, an atypical drama film for its creator, was written, directed, produced and later scored by Charlie Chaplin. It is also known as ''A Woman of Paris: A ...

'', a romantic drama about ill-fated lovers. Chaplin intended it to be a star-making vehicle for Edna Purviance, and did not appear in the picture himself other than in a brief, uncredited cameo. He wished the film to have a realistic feel and directed his cast to give restrained performances. In real life, he explained, "men and women try to hide their emotions rather than seek to express them". ''A Woman of Paris'' premiered in September 1923 and was acclaimed for its innovative, subtle approach. The public, however, seemed to have little interest in a Chaplin film without Chaplin, and it was a

box office disappointment. The filmmaker was hurt by this failurehe had long wanted to produce a dramatic film and was proud of the resultand soon withdrew ''A Woman of Paris'' from circulation.

Chaplin returned to comedy for his next project. Setting his standards high, he told himself "This next film must be an epic! The Greatest!" Inspired by a photograph of the 1898

Klondike Gold Rush, and later the story of the

Donner Party of 1846–1847, he made what Geoffrey Macnab calls "an epic comedy out of grim subject matter". In ''

The Gold Rush

''The Gold Rush'' is a 1925 American silent comedy film written, produced, and directed by Charlie Chaplin. The film also stars Chaplin in his Little Tramp persona, Georgia Hale, Mack Swain, Tom Murray, Henry Bergman, and Malcolm Waite.

Ch ...

'', the Tramp is a lonely

prospector fighting adversity and looking for love. With

Georgia Hale

Georgia Theodora Hale (June 25, 1900 — June 17, 1985) was an actress of the silent movie era.

Career

Hale was Miss Chicago 1922 and competed in the Miss America Pageant. She began acting in the early 1920s, and achieved one of her most not ...

as his leading lady, Chaplin began filming the picture in February 1924. Its elaborate production, costing almost $1million, included

location shooting

Location shooting is the shooting of a film or television production in a real-world setting rather than a sound stage or backlot. The location may be interior or exterior.

The filming location may be the same in which the story is set (for e ...

in the

Truckee mountains in

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a state in the Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the 7th-most extensive, ...

with 600 extras, extravagant sets, and

special effect

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual w ...

s. The last scene was shot in May 1925 after 15 months of filming.

Chaplin felt ''The Gold Rush'' was the best film he had made. It opened in August 1925 and became one of the highest-grossing films of the silent era with a U.S. box-office of $5million. The comedy contains some of Chaplin's most famous sequences, such as the Tramp eating his shoe and the "Dance of the Rolls". Macnab has called it "the quintessential Chaplin film". Chaplin stated at its release, "This is the picture that I want to be remembered by".

Lita Grey and ''The Circus''

While making ''The Gold Rush'', Chaplin married for the second time. Mirroring the circumstances of his first union,

Lita Grey was a teenage actress, originally set to star in the film, whose surprise announcement of pregnancy forced Chaplin into marriage. She was 16 and he was 35, meaning Chaplin could have been charged with

statutory rape

In common law jurisdictions, statutory rape is nonforcible sexual activity in which one of the individuals is below the age of consent (the age required to legally consent to the behavior). Although it usually refers to adults engaging in sexual ...

under California law. He therefore arranged a discreet marriage in Mexico on 25 November 1924. They originally met during her childhood and she had previously appeared in his works ''The Kid'' and ''The Idle Class''. Their first son,

Charles Spencer Chaplin III

Charles Spencer Chaplin III (May 5, 1925 – March 20, 1968), known professionally as Charles Chaplin Jr., was an American actor. He was the elder son of Charlie Chaplin and Lita Grey, and is known for appearing in 1950s films such as ''The Beat ...

, was born on 5May 1925, followed by

Sydney Earl Chaplin on 30 March 1926. On 6 July 1925, Chaplin became the first movie star to be featured on a ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

'' magazine

cover.

It was an unhappy marriage, and Chaplin spent long hours at the studio to avoid seeing his wife. In November 1926, Grey took the children and left the family home. A bitter divorce followed, in which Grey's applicationaccusing Chaplin of infidelity, abuse, and of harbouring "perverted sexual desires"was leaked to the press. Chaplin was reported to be in a state of nervous breakdown, as the story became headline news and groups formed across America calling for his films to be banned. Eager to end the case without further scandal, Chaplin's lawyers agreed to a cash settlement of $600,000the largest awarded by American courts at that time. His fan base was strong enough to survive the incident, and it was soon forgotten, but Chaplin was deeply affected by it.

Before the divorce suit was filed, Chaplin had begun work on a new film, ''

The Circus''. He built a story around the idea of walking a tightrope while besieged by monkeys, and turned the Tramp into the accidental star of a circus. Filming was suspended for ten months while he dealt with the divorce scandal, and it was generally a trouble-ridden production. Finally completed in October 1927, ''The Circus'' was released in January 1928 to a positive reception. At the

1st Academy Awards

The 1st Academy Awards ceremony, presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) and hosted by AMPAS president Douglas Fairbanks, honored the best films from 1 August 1927 to 31 July 1928 and took place on May ...

, Chaplin was given a special trophy "For versatility and genius in acting, writing, directing and producing ''The Circus''".

Despite its success, he permanently associated the film with the stress of its production; Chaplin omitted ''The Circus'' from his autobiography, and struggled to work on it when he recorded the score in his later years.

''City Lights''

By the time ''The Circus'' was released, Hollywood had witnessed the introduction of

sound film

A sound film is a motion picture with synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, but decades passed befo ...

s. Chaplin was cynical about this new medium and the technical shortcomings it presented, believing that "talkies" lacked the artistry of silent films. He was also hesitant to change the formula that had brought him such success, and feared that giving the Tramp a voice would limit his international appeal. He, therefore, rejected the new Hollywood craze and began work on a new silent film. Chaplin was nonetheless anxious about this decision and remained so throughout the film's production.

When filming began at the end of 1928, Chaplin had been working on the story for almost a year. ''

City Lights'' followed the Tramp's love for a blind flower girl (played by

Virginia Cherrill) and his efforts to raise money for her sight-saving operation. It was a challenging production that lasted 21 months, with Chaplin later confessing that he "had worked himself into a neurotic state of wanting perfection". One advantage Chaplin found in sound technology was the opportunity to record a musical score for the film, which he composed himself.

Chaplin finished editing ''City Lights'' in December 1930, by which time silent films were an anachronism. A preview before an unsuspecting public audience was not a success, but a showing for the press produced positive reviews. One journalist wrote, "Nobody in the world but Charlie Chaplin could have done it. He is the only person that has that peculiar something called 'audience appeal' in sufficient quality to defy the popular penchant for movies that talk." Given its general release in January 1931, ''City Lights'' proved to be a popular and financial success, eventually grossing over $3million. The

British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

cites it as Chaplin's finest accomplishment, and the critic

James Agee

James Rufus Agee ( ; November 27, 1909 – May 16, 1955) was an American novelist, journalist, poet, screenwriter and film critic. In the 1940s, writing for ''Time Magazine'', he was one of the most influential film critics in the United States. ...

hails the closing scene as "the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies".

''City Lights'' became Chaplin's personal favourite of his films and remained so throughout his life.

Travels, Paulette Goddard, and ''Modern Times''

''City Lights'' had been a success, but Chaplin was unsure if he could make another picture without dialogue. He remained convinced that sound would not work in his films, but was also "obsessed by a depressing fear of being old-fashioned". In this state of uncertainty, early in 1931, the comedian decided to take a holiday and ended up travelling for 16 months. He spent months travelling Western Europe, including extended stays in France and Switzerland, and spontaneously decided to visit Japan. The day after he arrived in Japan, Prime Minister

Inukai Tsuyoshi was assassinated by ultra-nationalists in the

May 15 Incident. The group's original plan had been to provoke a war with the United States by assassinating Chaplin at a welcome reception organised by the prime minister, but the plan had been foiled due to delayed public announcement of the event's date.

In his autobiography, Chaplin recalled that on his return to Los Angeles, "I was confused and without plan, restless and conscious of an extreme loneliness". He briefly considered retiring and moving to China. Chaplin's loneliness was relieved when he met 21-year-old actress

Paulette Goddard

Paulette Goddard (born Marion Levy; June 3, 1910 – April 23, 1990) was an American actress notable for her film career in the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Born in Manhattan and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, Goddard initially began her career ...

in July 1932, and the pair began a relationship. He was not ready to commit to a film, however, and focused on writing a

serial about his travels (published in ''

Woman's Home Companion

''Woman's Home Companion'' was an American monthly magazine, published from 1873 to 1957. It was highly successful, climbing to a circulation peak of more than four million during the 1930s and 1940s. The magazine, headquartered in Springfield, O ...

''). The trip had been a stimulating experience for Chaplin, including meetings with several prominent thinkers, and he became increasingly interested in world affairs. The state of labour in America troubled him, and he feared that capitalism and machinery in the workplace would increase unemployment levels. It was these concerns that stimulated Chaplin to develop his new film.

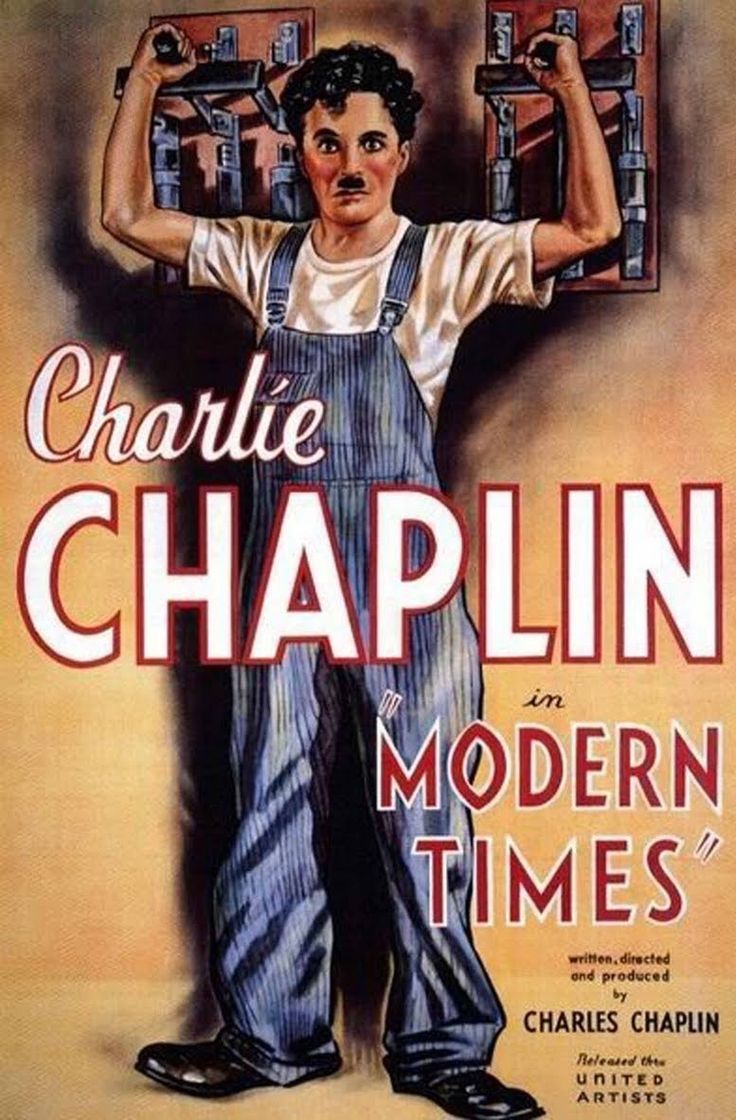

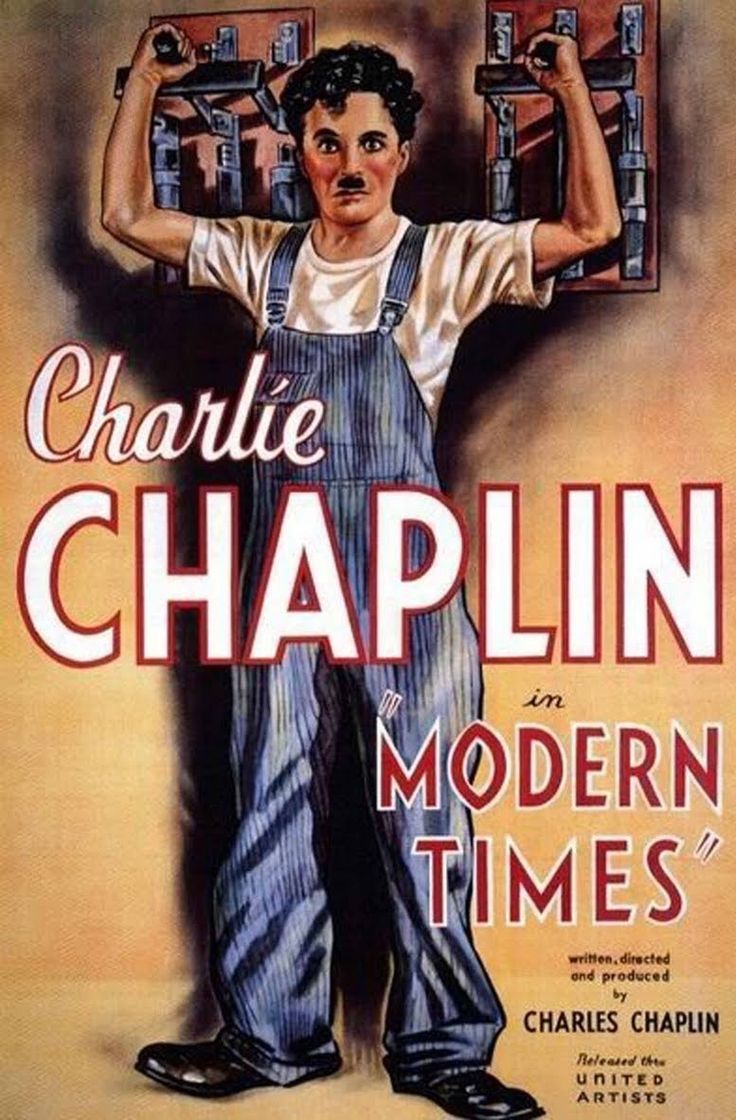

''

Modern Times'' was announced by Chaplin as "a satire on certain phases of our industrial life". Featuring the Tramp and Goddard as they endure the

Great Depression, it took ten and a half months to film. Chaplin intended to use spoken dialogue but changed his mind during rehearsals. Like its predecessor, ''Modern Times'' employed sound effects but almost no speaking. Chaplin's performance of a gibberish song did, however, give the Tramp a voice for the only time on film. After recording the music, Chaplin released ''Modern Times'' in February 1936. It was his first feature in 15 years to adopt political references and social realism, a factor that attracted considerable press coverage despite Chaplin's attempts to downplay the issue. The film earned less at the box-office than his previous features and received mixed reviews, as some viewers disliked the politicising. Today, ''Modern Times'' is seen by the British Film Institute as one of Chaplin's "great features",

while David Robinson says it shows the filmmaker at "his unrivalled peak as a creator of visual comedy".

Following the release of ''Modern Times'', Chaplin left with Goddard for a trip to the Far East. The couple had refused to comment on the nature of their relationship, and it was not known whether they were married or not. Sometime later, Chaplin revealed that they married in

Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ent ...

during this trip. By 1938, the couple had drifted apart, as both focused heavily on their work, although Goddard was again his leading lady in his next feature film, ''The Great Dictator''. She eventually divorced Chaplin in Mexico in 1942, citing incompatibility and separation for more than a year.

1939–1952: controversies and fading popularity

''The Great Dictator''

The 1940s saw Chaplin face a series of controversies, both in his work and in his personal life, which changed his fortunes and severely affected his popularity in the United States. The first of these was his growing boldness in expressing his political beliefs. Deeply disturbed by the

surge of militaristic nationalism in 1930s world politics, Chaplin found that he could not keep these issues out of his work. Parallels between himself and

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

had been widely noted: the pair were born four days apart, both had risen from poverty to world prominence, and Hitler wore

the same moustache style as Chaplin. It was this physical resemblance that supplied the plot for Chaplin's next film, ''

The Great Dictator

''The Great Dictator'' is a 1940 American anti-war political satire black comedy film written, directed, produced, scored by, and starring British comedian Charlie Chaplin, following the tradition of many of his other films. Having been the ...

'', which directly satirised Hitler and attacked fascism.

Chaplin spent two years developing the script and began filming in September 1939, six days after Britain declared war on Germany. He had submitted to using spoken dialogue, partly out of acceptance that he had no other choice, but also because he recognised it as a better method for delivering a political message. Making a comedy about Hitler was seen as highly controversial, but Chaplin's financial independence allowed him to take the risk. "I was determined to go ahead", he later wrote, "for Hitler must be laughed at." Chaplin replaced the Tramp (while wearing similar attire) with "A Jewish Barber", a reference to the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

's belief that he was Jewish. In a dual performance, he also played the dictator "Adenoid Hynkel", a parody of Hitler.

''The Great Dictator'' spent a year in production and was released in October 1940. The film generated a vast amount of publicity, with a critic for ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' calling it "the most eagerly awaited picture of the year", and it was one of the biggest money-makers of the era. The ending was unpopular, however, and generated controversy. Chaplin concluded the film with a five-minute speech in which he abandoned his barber character, looked directly into the camera, and pleaded against war and fascism. Charles J. Maland has identified this overt preaching as triggering a decline in Chaplin's popularity, and writes, "Henceforth, no movie fan would ever be able to separate the dimension of politics from

isstar image". Nevertheless, both

Winston Churchill and

Franklin D. Roosevelt liked the film, which they saw at private screenings before its release. Roosevelt subsequently invited Chaplin to read the film's final speech over the radio during his January 1941 inauguration, with the speech becoming a "hit" of the celebration. Chaplin was often invited to other patriotic functions to read the speech to audiences during the years of the war. ''The Great Dictator'' received five Academy Award nominations, including

Best Picture

This is a list of categories of awards commonly awarded through organizations that bestow film awards, including those presented by various film, festivals, and people's awards.

Best Actor/Best Actress

*See Best Actor#Film awards, Best Actress#F ...

,

Best Original Screenplay and

Best Actor

Best Actor is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organizations, festivals, and people's awards to leading actors in a film, television series, television film or play.

The term most often refers to th ...

.

Legal troubles and Oona O'Neill

In the mid-1940s, Chaplin was involved in a series of trials that occupied most of his time and significantly affected his public image. The troubles stemmed from his affair with an aspiring actress named

Joan Barry, with whom he was involved intermittently between June 1941 and the autumn of 1942. Barry, who displayed obsessive behaviour and was twice arrested after they separated, reappeared the following year and announced that she was pregnant with Chaplin's child. As Chaplin denied the claim, Barry filed a

paternity suit against him.

The director of the

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI),

J. Edgar Hoover, who had long been suspicious of Chaplin's political leanings, used the opportunity to generate negative publicity about him. As part of a

smear campaign

A smear campaign, also referred to as a smear tactic or simply a smear, is an effort to damage or call into question someone's reputation, by propounding negative propaganda. It makes use of discrediting tactics.

It can be applied to individual ...

to damage Chaplin's image, the FBI named him in four indictments related to the Barry case. Most serious of these was an alleged violation of the

Mann Act

The White-Slave Traffic Act, also called the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, ; ''codified as amended at'' ). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act made ...

, which prohibits the transportation of women across state boundaries for sexual purposes. Historian

Otto Friedrich called this an "absurd prosecution" of an "ancient statute", yet if Chaplin was found guilty, he faced 23 years in jail. Three charges lacked sufficient evidence to proceed to court, but the Mann Act trial began on 21 March 1944. Chaplin was acquitted two weeks later, on4 April. The case was frequently headline news, with ''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' calling it the "biggest public relations scandal since the

Fatty Arbuckle murder trial in 1921".

Barry's child, Carol Ann, was born in October 1943, and the paternity suit went to court in December 1944. After two arduous trials, in which the prosecuting lawyer accused him of "

moral turpitude", Chaplin was declared to be the father. Evidence from blood tests that indicated otherwise were not admissible, and the judge ordered Chaplin to pay child support until Carol Ann turned 21. Media coverage of the suit was influenced by the FBI, which fed information to gossip columnist

Hedda Hopper, and Chaplin was portrayed in an overwhelmingly critical light.

The controversy surrounding Chaplin increased whentwo weeks after the paternity suit was filedit was announced that he had married his newest

protégée, 18-year-old

Oona O'Neill, the daughter of American playwright

Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in Nobel Prize in Literature, literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama tech ...

. Chaplin, then 54, had been introduced to her by a film agent seven months earlier. In his autobiography, Chaplin described meeting O'Neill as "the happiest event of my life", and claimed to have found "perfect love". Chaplin's son, Charles III, reported that Oona "worshipped" his father. The couple remained married until Chaplin's death, and had eight children over 18 years:

Geraldine Leigh (b. July 1944),

Michael John (b. March 1946),

Josephine Hannah (b. March 1949),

Victoria Agnes (b. May 1951),

Eugene Anthony (b. August 1953), Jane Cecil (b. May 1957), Annette Emily (b. December 1959), and

Christopher James (b. July 1962).

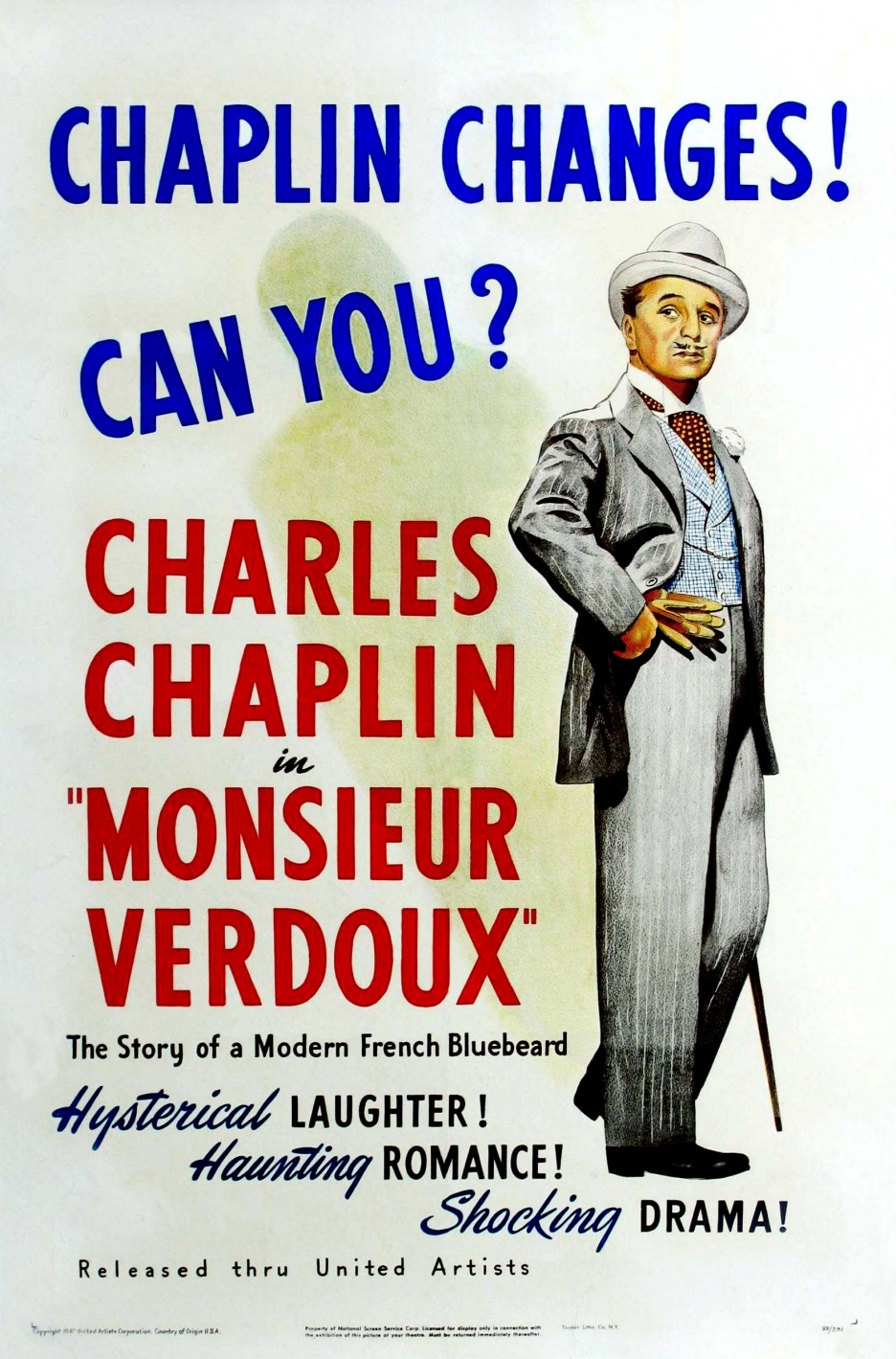

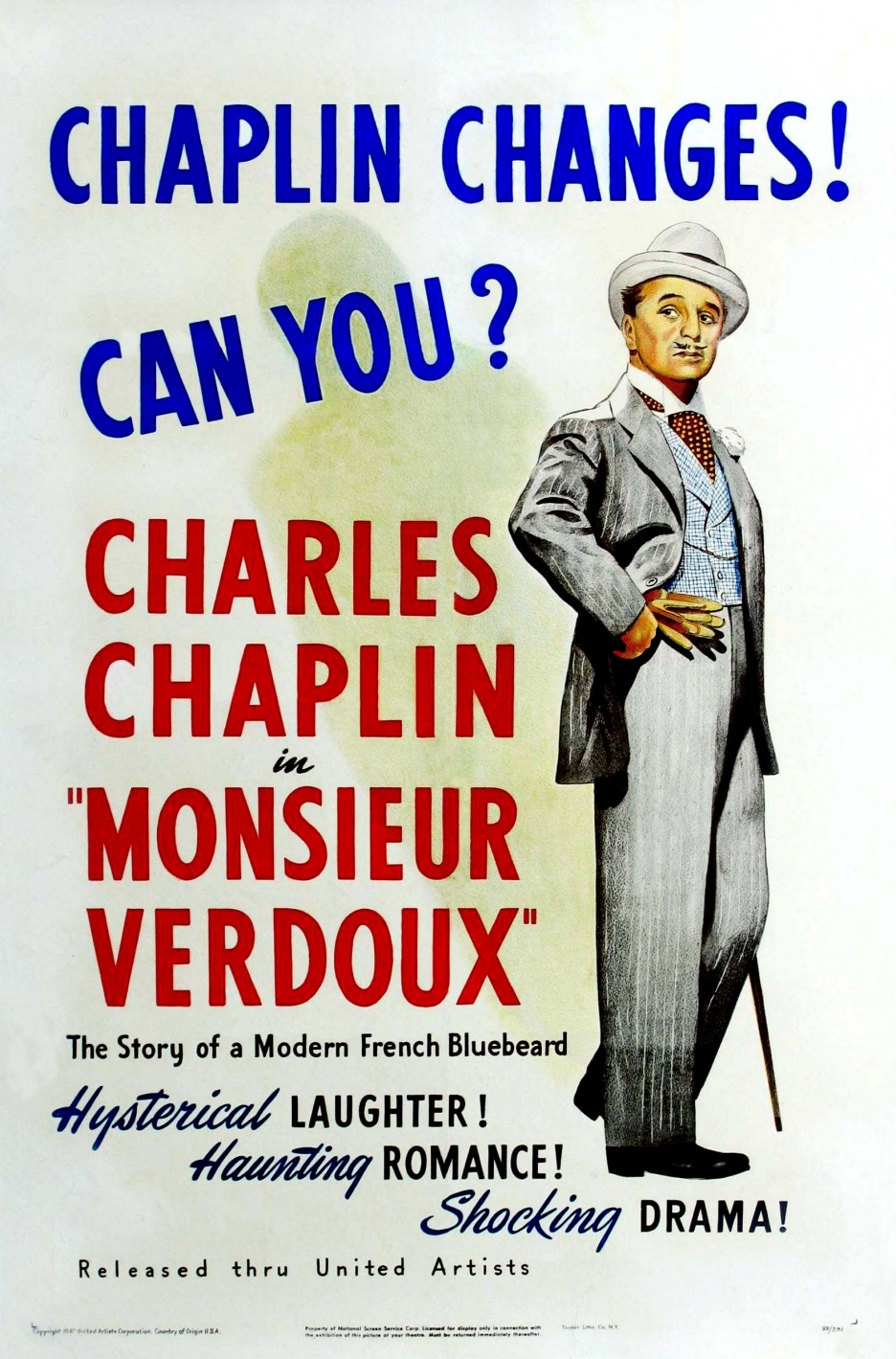

''Monsieur Verdoux'' and communist accusations

Chaplin claimed that the Barry trials had "crippled

iscreativeness", and it was some time before he began working again. In April 1946, he finally began filming a project that had been in development since 1942. ''

Monsieur Verdoux'' was a

black comedy

Black comedy, also known as dark comedy, morbid humor, or gallows humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally considered serious or painful to discus ...

, the story of a French bank clerk, Verdoux (Chaplin), who loses his job and begins marrying and murdering wealthy widows to support his family. Chaplin's inspiration for the project came from

Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

, who wanted him to star in a film about the French

serial killer

A serial killer is typically a person who murders three or more persons,A

*

*

*

* with the murders taking place over more than a month and including a significant period of time between them. While most authorities set a threshold of three ...

Henri Désiré Landru. Chaplin decided that the concept would "make a wonderful comedy", and paid Welles $5,000 for the idea.

Chaplin again vocalised his political views in ''Monsieur Verdoux'', criticising

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and arguing that the world encourages mass killing through wars and

weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natur ...

. Because of this, the film met with controversy when it was released in April 1947; Chaplin was booed at the premiere, and there were calls for a boycott. ''Monsieur Verdoux'' was the first Chaplin release that failed both critically and commercially in the United States. It was more successful abroad, and Chaplin's screenplay was nominated at the

Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

. He was proud of the film, writing in his autobiography, "''Monsieur Verdoux'' is the cleverest and most brilliant film I have yet made."

The negative reaction to ''Monsieur Verdoux'' was largely the result of changes in Chaplin's public image. Along with the damage of the Joan Barry scandal, he was publicly accused of being a

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

. His political activity had heightened during World War II, when he campaigned for the opening of a Second Front to help the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and supported various Soviet–American friendship groups. He was also friendly with several suspected communists, and attended functions given by Soviet diplomats in Los Angeles. In the political climate of 1940s America, such activities meant Chaplin was considered, as Larcher writes, "dangerously

progressive

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

and amoral". The FBI wanted him out of the country, and launched an official investigation in early 1947.

Chaplin denied being a communist, instead calling himself a "peacemonger", but felt the government's effort to suppress the ideology was an unacceptable infringement of

civil liberties. Unwilling to be quiet about the issue, he openly protested against the trials of

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

members and the activities of the

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

. Chaplin received a

subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

to appear before HUAC but was not called to testify. As his activities were widely reported in the press, and

Cold War fears grew, questions were raised over his failure to take American citizenship. Calls were made for him to be deported; in one extreme and widely published example, Representative

John E. Rankin, who helped establish HUAC, told

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

in June 1947: "

haplin'svery life in Hollywood is detrimental to the moral fabric of America.

f he is deported

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

.. his loathsome pictures can be kept from before the eyes of the American youth. He should be deported and gotten rid of at once."

In 2003, declassified British archives belonging to the

British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreig ...

revealed that

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalita ...

secretly accused Chaplin of being a secret communist and a friend of the USSR.

Chaplin's name was one of 35 Orwell gave to the

Information Research Department (IRD), a secret British Cold War propaganda department which worked closely with the CIA, according to a 1949 document known as

Orwell's list.

Chaplin was not the only actor in America Orwell accused of being a secret communist. He also described American civil-rights leader and actor

Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, professional football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for his ...

as being "anti-white".

''Limelight'' and banning from the United States

Although Chaplin remained politically active in the years following the failure of ''Monsieur Verdoux'', his next film, about a forgotten music hall comedian and a young ballerina in

Edwardian

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

London, was devoid of political themes. ''

Limelight

Limelight (also known as Drummond light or calcium light)James R. Smith (2004). ''San Francisco's Lost Landmarks'', Quill Driver Books. is a type of stage lighting once used in theatres and music halls. An intense illumination is created w ...

'' was heavily autobiographical, alluding not only to Chaplin's childhood and the lives of his parents, but also to his loss of popularity in the United States. The cast included various members of his family, including his five oldest children and his half-brother, Wheeler Dryden.

Filming began in November 1951, by which time Chaplin had spent three years working on the story. He aimed for a more serious tone than any of his previous films, regularly using the word "melancholy" when explaining his plans to his co-star

Claire Bloom. ''Limelight'' featured a cameo appearance from

Buster Keaton, whom Chaplin cast as his stage partner in a pantomime scene. This marked the only time the comedians worked together in a feature film.

Chaplin decided to hold the world premiere of ''Limelight'' in London, since it was the setting of the film. As he left Los Angeles, he expressed a premonition that he would not be returning. At New York, he boarded the with his family on 18 September 1952. The next day,

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

James P. McGranery

James Patrick McGranery (July 8, 1895 – December 23, 1962) was a United States representative from Pennsylvania, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and Attorney General of ...

revoked Chaplin's

re-entry permit A re-entry permit is required by some countries, for their citizens or tourists who leave the country for an extended period of time. For example, the United States issues a re-entry permit to a resident alien who plans to travel abroad for an exten ...

and stated that he would have to submit to an interview concerning his political views and moral behaviour to re-enter the US. Although McGranery told the press that he had "a pretty good case against Chaplin", Maland has concluded, on the basis of the FBI files that were released in the 1980s, that the US government had no real evidence to prevent Chaplin's re-entry. It is likely that he would have gained entry if he had applied for it. However, when Chaplin received a cablegram informing him of the news, he privately decided to cut his ties with the United States:

Because all of his property remained in America, Chaplin refrained from saying anything negative about the incident to the press. The scandal attracted vast attention, but Chaplin and his film were warmly received in Europe. In America, the hostility towards him continued, and, although it received some positive reviews, ''Limelight'' was subjected to a wide-scale boycott. Reflecting on this, Maland writes that Chaplin's fall, from an "unprecedented" level of popularity, "may be the most dramatic in the history of stardom in America".

1953–1977: European years

Move to Switzerland and ''A King in New York''

Chaplin did not attempt to return to the United States after his re-entry permit was revoked, and instead sent his wife to settle his affairs. The couple decided to settle in Switzerland and, in January 1953, the family moved into their permanent home:

Manoir de Ban, a estate overlooking

Lake Geneva

, image = Lake Geneva by Sentinel-2.jpg

, caption = Satellite image

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = Switzerland, France

, coords =

, lake_type = Glacial la ...

in

Corsier-sur-Vevey. Chaplin put his Beverly Hills house and studio up for sale in March, and surrendered his re-entry permit in April. The next year, his wife renounced her US citizenship and became a British citizen. Chaplin severed the last of his professional ties with the United States in 1955, when he sold the remainder of his stock in United Artists, which had been in financial difficulty since the early 1940s.

Chaplin remained a controversial figure throughout the 1950s, especially after he was awarded the

International Peace Prize by the communist-led

World Peace Council, and after his meetings with

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 January 1976. Zhou served under Chairman Ma ...

and

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev ...

. He began developing his first European film, ''

A King in New York'', in 1954. Casting himself as an exiled king who seeks asylum in the United States, Chaplin included several of his recent experiences in the screenplay. His son, Michael, was cast as a boy whose parents are targeted by the FBI, while Chaplin's character faces accusations of communism. The political satire parodied HUAC and attacked elements of 1950s cultureincluding consumerism, plastic surgery, and wide-screen cinema. In a review, the playwright

John Osborne

John James Osborne (12 December 1929 – 24 December 1994) was an English playwright, screenwriter and actor, known for his prose that criticized established social and political norms. The success of his 1956 play '' Look Back in Anger'' tr ...

called it Chaplin's "most bitter" and "most openly personal" film. In a 1957 interview, when asked to clarify his political views, Chaplin stated "As for politics, I am an anarchist. I hate government and rulesand fetters... People must be free."

Chaplin founded a new production company, Attica, and used

Shepperton Studios

Shepperton Studios is a film studio located in Shepperton, Surrey, England, with a history dating back to 1931. It is now part of the Pinewood Studios Group. During its early existence, the studio was branded as Sound City (not to be confused ...