The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the

largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion

baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

Catholics

worldwide .

It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a prominent role in the history and development of

Western civilization

human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Clemetino Inv305.jpg, upPlato, arguably the most influential figure in all of Western philosoph ...

.

O'Collins O'Collins is a common anglicized surname of two ancient families of Irish origin: O'Cuilleain and O'Coilean.

Origin of O'Cuilleain

O'Cuilleain or Cuilliaéan is an extremely ancient Irish name from Gaelic ''cuileann'' and primitive Gaelic '' ...

, p. v (preface). The church consists of 24

''sui iuris'' churches, including the

Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Jo ...

and 23

Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, which comprise almost 3,500

diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

s and

eparchies

Eparchy ( gr, ἐπαρχία, la, eparchía / ''overlordship'') is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity, that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. Eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on ...

located

around the world. The

pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, who is the bishop of Rome, is the

chief pastor of the church. The bishopric of Rome, known as the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, is the central governing authority of the church. The administrative body of the Holy See, the

Roman Curia, has its principal offices in

Vatican City

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

, a small enclave of the Italian city of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, of which the pope is

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state (polity), state#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international p ...

.

The core beliefs of Catholicism are found in the

Nicene Creed

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

. The Catholic Church teaches that it is the

one, holy, catholic and apostolic church founded by

Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

in his

Great Commission

In Christianity, the Great Commission is the instruction of the resurrected Jesus Christ to his disciples to spread the gospel to all the nations of the world. The Great Commission is outlined in Matthew 28:16– 20, where on a mountain i ...

,

that its

bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of Episcopal polity, authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or offic ...

are the

successors of Christ's

apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

, and that the pope is the

successor

Successor may refer to:

* An entity that comes after another (see Succession (disambiguation))

Film and TV

* ''The Successor'' (film), a 1996 film including Laura Girling

* ''The Successor'' (TV program), a 2007 Israeli television program Mus ...

to

Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupa ...

, upon whom

primacy

Primacy may refer to:

* an office of the Primate (bishop)

* the supremacy of one bishop or archbishop over others, most notably:

** Primacy of Peter, ecclesiological doctrine on the primacy of Peter the Apostle

** Primacy of the Roman Pontiff ...

was conferred by Jesus Christ. It maintains that it practises the original Christian faith taught by the apostles, preserving the faith

infallibly through

scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pract ...

and

sacred tradition

Sacred tradition is a theological term used in Christian theology. According to the theology of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian churches, sacred tradition is the foundation of the doctrinal and spiritual authority o ...

as authentically interpreted through the

magisterium

The magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and larg ...

of the church.

The

Roman Rite

The Roman Rite ( la, Ritus Romanus) is the primary liturgical rite of the Latin Church, the largest of the '' sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. It developed in the Latin language in the city of Rome and, while d ...

and

others of the Latin Church, the

Eastern Catholic liturgies

The Eastern Catholic Churches of the Catholic Church utilize liturgies originating in Eastern Christianity, distinguishing them from the majority of Catholic liturgies which are celebrated according to the Latin liturgical rites of the Latin Chu ...

, and institutes such as

mendicant orders,

enclosed monastic orders and

third orders reflect a

variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

of

theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

and spiritual emphases in the church.

[Colin Gunton. "Christianity among the Religions in the Encyclopedia of Religion", Religious Studies, Vol. 24, number 1, page 14. In a review of an article from the Encyclopedia of Religion, Gunton writes: " e article ]n Catholicism in the encyclopedia

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

rightly suggests caution, suggesting at the outset that Roman Catholicism is marked by several different doctrinal, theological and liturgical emphases."

Of its

seven sacraments

There are seven sacraments of the Catholic Church, which according to Catholic theology were instituted by Jesus and entrusted to the Church. Sacraments are visible rites seen as signs and efficacious channels of the grace of God to all those ...

, the

Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

is the principal one, celebrated

liturgically in the

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different element ...

. The church teaches that through

consecration by a

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

, the sacrificial

bread and

wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are ...

become the

body and blood of Christ. The

Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

is

venerated

Veneration ( la, veneratio; el, τιμάω ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Etym ...

as the

Perpetual Virgin,

Mother of God

''Theotokos'' (Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are ''Dei Genitrix'' or '' Deipara'' (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are ...

, and

Queen of Heaven

Queen of Heaven ( la, Regina Caeli) is a title given to the Virgin Mary, by Christians mainly of the Catholic Church and, to a lesser extent, in Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and Eastern Orthodoxy.

The Catholic teaching on this subject is express ...

; she is honoured in

dogmas

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

and

devotions.

Catholic social teaching

Catholic social teaching, commonly abbreviated CST, is an area of Catholic doctrine concerning matters of human dignity and the common good in society. The ideas address oppression, the role of the state, subsidiarity, social organization, ...

emphasizes voluntary support for the sick, the poor, and the afflicted through the

corporal and spiritual works of mercy. The Catholic Church operates thousands of

Catholic school

Catholic schools are pre-primary, primary and secondary educational institutions administered under the aegis or in association with the Catholic Church. , the Catholic Church operates the world's largest religious, non-governmental school syst ...

s,

universities and colleges

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after completi ...

,

hospitals

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergenc ...

, and orphanages around the world, and is the largest non-government provider of

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. ...

and health care in the world.

Among its other social services are numerous charitable and humanitarian organizations.

The Catholic Church has profoundly influenced

Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The wo ...

,

culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these grou ...

,

art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

,

music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

and science. Catholics live all over the world through

missions

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

* Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

,

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews afte ...

, and

conversions

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

. Since the 20th century, the majority have resided in the

Southern Hemisphere, partially due to

secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses t ...

in Europe and increased

persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

. The Catholic Church shared

communion

Communion may refer to:

Religion

* The Eucharist (also called the Holy Communion or Lord's Supper), the Christian rite involving the eating of bread and drinking of wine, reenacting the Last Supper

**Communion (chant), the Gregorian chant that ac ...

with the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

until the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, ...

in 1054, disputing particularly the

authority of the pope. Before the

Council of Ephesus in AD 431, the

Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

also shared in this communion, as did the

Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent o ...

before the

Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bi ...

in AD 451; all separated primarily over

differences in Christology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Differ ...

. The Eastern Catholic Churches, who have a combined membership of approximately 18 million, represent a body of

Eastern Christians

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent and ...

who returned or remained in communion with the pope during or following these

schisms for a variety of historical circumstances. In the 16th century, the

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

led to

Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

also breaking away. From the late 20th century, the Catholic Church has been

criticized for its

teachings on sexuality, its

doctrine against ordaining women, and its handling of

sexual abuse cases involving clergy.

Name

Catholic (from el, καθολικός, katholikos, universal) was first used to describe the church in the early 2nd century. The first known use of the phrase "the catholic church" ( el, καθολικὴ ἐκκλησία, he katholike ekklesia) occurred in the letter written about 110 AD from

Saint Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (; Greek: Ἰγνάτιος Ἀντιοχείας, ''Ignátios Antiokheías''; died c. 108/140 AD), also known as Ignatius Theophorus (, ''Ignátios ho Theophóros'', lit. "the God-bearing"), was an early Christian writer ...

to the

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

eans.): "Wheresoever the bishop shall appear, there let the people be, even as where Jesus may be, there is the universal

atholikeChurch."

In the ''Catechetical Lectures'' () of

Saint Cyril of Jerusalem

Cyril of Jerusalem ( el, Κύριλλος Α΄ Ἱεροσολύμων, ''Kýrillos A Ierosolýmon''; la, Cyrillus Hierosolymitanus; 313 386 AD) was a theologian of the early Church. About the end of 350 AD he succeeded Maximus as Bishop of ...

, the name "Catholic Church" was used to distinguish it from other groups that also called themselves "the church".

The "Catholic" notion was further stressed in the edict ''

De fide Catolica'' issued 380 by

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, the last emperor to rule over both the

eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air L ...

and the

western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

halves of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, when establishing the

state church of the Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion ...

.

Since the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, ...

of 1054, the

Eastern Church

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent and ...

has taken the adjective "Orthodox" as its distinctive epithet (however, its official name continues to be the "Orthodox Catholic Church") and the

Western Church

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholic ...

in communion with the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

has similarly taken "Catholic", keeping that description also after the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

of the 16th century, when those who ceased to be in communion became known as "Protestants".

[McBrien, Richard (2008). ''The Church''. Harper Collins. p. xvii. Online version availabl]

Browseinside.harpercollins.com

. Quote: " e use of the adjective 'Catholic' as a modifier of 'Church' became divisive only after the East–West Schism... and the Protestant Reformation. ... In the former case, the Western Church claimed for itself the title ''Catholic'' Church, while the East appropriated the name ''Orthodox'' Church. In the latter case, those in communion with the Bishop of Rome retained the adjective "Catholic", while the churches that broke with the Papacy were called ''Protestant''."

While the "Roman Church" has been used to describe the pope's

Diocese of Rome

The Diocese of Rome ( la, Dioecesis Urbis seu Romana; it, Diocesi di Roma) is the ecclesiastical district under the direct jurisdiction of the Pope, who is Bishop of Rome and hence the supreme pontiff and head of the worldwide Catholic Churc ...

since the

Fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

and into the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the M ...

(6th–10th century), the "Roman Catholic Church" has been applied to the whole church in the English language since the Protestant Reformation in the late 16th century. Further, some will refer to the Latin Church as "Roman Catholic" in distinction from the Eastern Catholic churches. "Roman Catholic" has occasionally appeared also in documents produced both by the Holy See,

[Examples uses of "Roman Catholic" by the Holy See: the encyclical]

''Divini Illius Magistri''

of Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fr ...

an

''Humani generis''

of Pope Pius XII; joint declarations signed by Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

wit

Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams on 23 November 2006

an

/ref> and notably used by certain national episcopal conference

An episcopal conference, sometimes called a conference of bishops, is an official assembly of the bishops of the Catholic Church in a given territory. Episcopal conferences have long existed as informal entities. The first assembly of bishops to ...

s and local dioceses.[Example use of "Roman" Catholic by a bishop's conference: ''The Baltimore Catechism'', an official catechism authorized by the Catholic bishops of the United States, states: "That is why we are called Roman Catholics; to show that we are united to the real successor of St Peter" (Question 118) and refers to the church as the "Roman Catholic Church" under Questions 114 and 131]

Baltimore Catechism).

/ref>

The name "Catholic Church" for the whole church is used in the ''Catechism of the Catholic Church

The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' ( la, Catechismus Catholicae Ecclesiae; commonly called the ''Catechism'' or the ''CCC'') is a catechism promulgated for the Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II in 1992. It aims to summarize, in book ...

'' (1990) and the Code of Canon Law (1983). The name "Catholic Church" is also used in the documents of the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

(1962–1965), the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth e ...

(1869–1870), the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

(1545–1563), and numerous other official documents.

History

The Christian religion is based on the reported teachings of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

, who lived and preached in the 1st century AD in the province of Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. Catholic theology

Catholic theology is the understanding of Catholic doctrine or teachings, and results from the studies of theologians. It is based on canonical scripture, and sacred tradition, as interpreted authoritatively by the magisterium of the Catholic ...

teaches that the contemporary Catholic Church is the continuation of this early Christian community established by Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religi ...

.Emperor Constantine

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

legalized the practice of Christianity in 313, and it became the state religion in 380. Germanic invaders of Roman territory in the 5th and 6th centuries, many of whom had previously adopted Arian Christianity

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

, eventually adopted Catholicism to ally themselves with the papacy and the monasteries.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, expanding Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

following the advent of Islam led to an Arab domination of the Mediterranean that severed political connections between that area and northern Europe, and weakened cultural connections between Rome and the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

. Conflicts involving authority in the church, particularly the authority of the bishop of Rome finally culminated in the East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, ...

in the 11th century, splitting the church into the Catholic and Orthodox churches. Earlier splits within the church occurred after the Council of Ephesus (431) and the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bi ...

(451). However, a few Eastern Churches remained in communion

Communion may refer to:

Religion

* The Eucharist (also called the Holy Communion or Lord's Supper), the Christian rite involving the eating of bread and drinking of wine, reenacting the Last Supper

**Communion (chant), the Gregorian chant that ac ...

with Rome, and portions of some others established communion in the 15th century and later, forming what are called the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Early monasteries throughout Europe helped preserve Greek and Roman

Early monasteries throughout Europe helped preserve Greek and Roman classical civilization

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. The church eventually became the dominant influence in Western civilization into the modern age. Many Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

figures were sponsored by the church. The 16th century, however, began to see challenges to the church, in particular to its religious authority, by figures in the Protestant Reformation, as well as in the 17th century by secular intellectuals in the Enlightenment. Concurrently, Spanish and Portuguese explorers and missionaries spread the church's influence through Africa, Asia, and the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

.

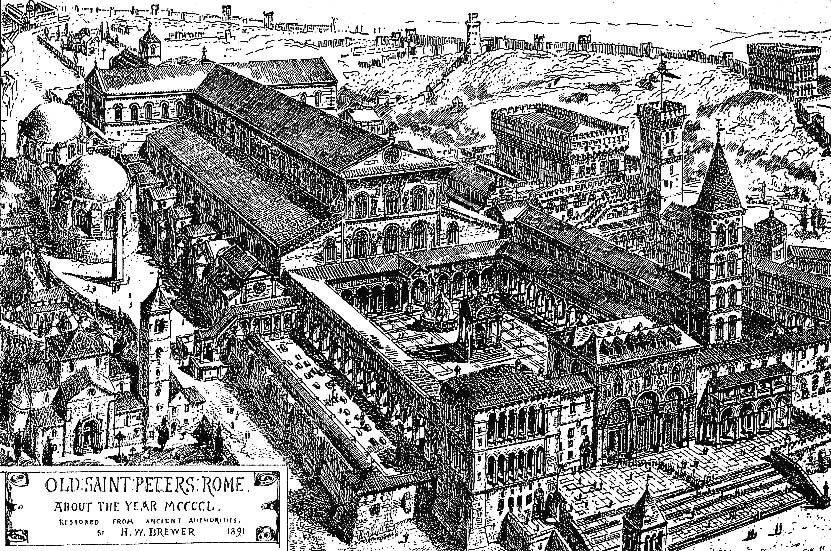

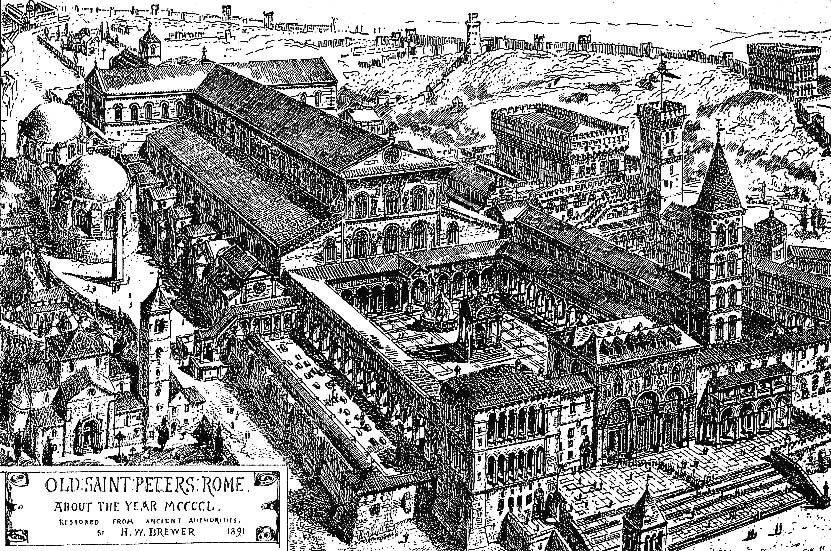

In 1870, the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth e ...

declared the dogma of papal infallibility

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks '' ex cathedra'' is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apos ...

and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and ...

annexed the city of Rome, the last portion of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

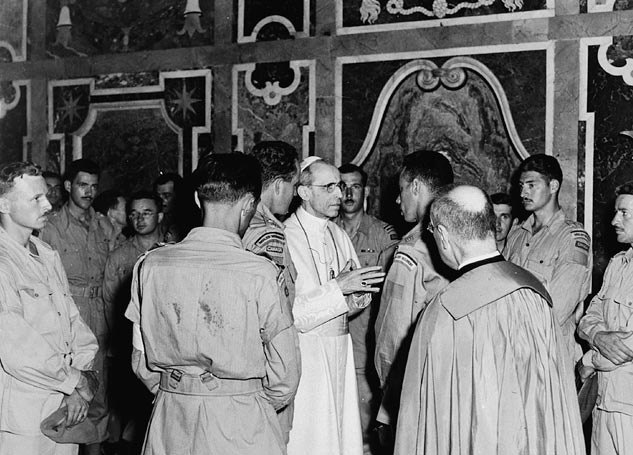

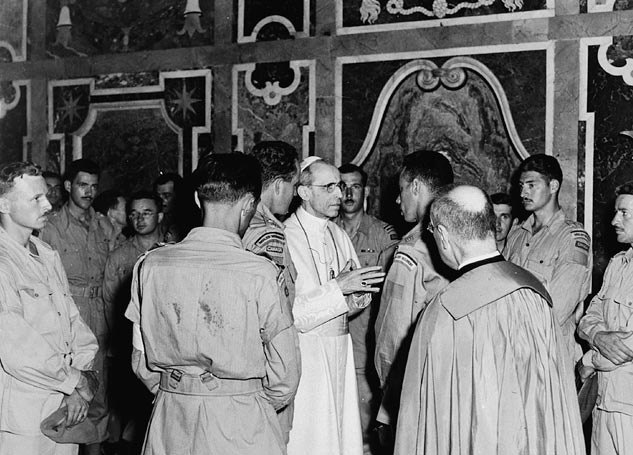

to be incorporated into the new nation. In the 20th century, anti-clerical governments around the world, including Mexico and Spain, persecuted or executed thousands of clerics and laypersons. In the Second World War, the church condemned Nazism, and protected hundreds of thousands of Jews from the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

; its efforts, however, have been criticized as inadequate. After the war, freedom of religion was severely restricted in the communist countries

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Cominte ...

newly aligned with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, several of which had large Catholic populations.

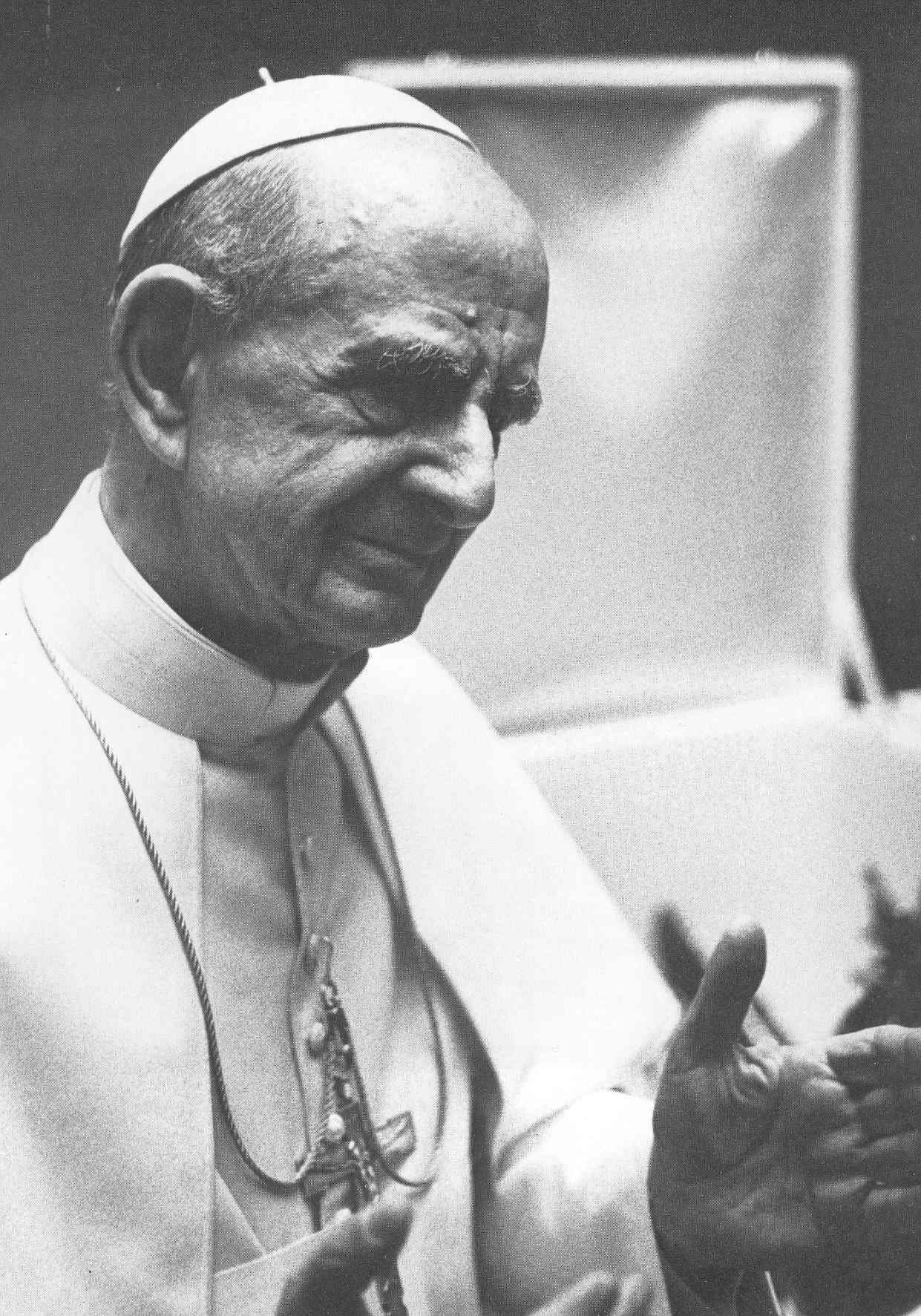

In the 1960s, the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

led to reforms of the church's liturgy and practices, described as "opening the windows" by defenders, but criticized by traditionalist Catholic

Traditionalist Catholicism is the set of beliefs, practices, customs, traditions, liturgical forms, devotions, and presentations of Catholic teaching that existed in the Catholic Church before the liberal reforms of the Second Vatican Council ( ...

s. In the face of increased criticism from both within and without, the church has upheld or reaffirmed at various times controversial doctrinal positions regarding sexuality and gender, including limiting clergy to males, and moral exhortations against abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

, contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, sexual activity

Human sexual activity, human sexual practice or human sexual behaviour is the manner in which humans experience and express their sexuality. People engage in a variety of sexual acts, ranging from activities done alone (e.g., masturbation) ...

outside of marriage, remarriage following divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

without annulment

Annulment is a legal procedure within secular and religious legal systems for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that an annulled marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning almost ...

, and against same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

.

Apostolic era and papacy

The

The New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, in particular the Gospels, records Jesus' activities and teaching, his appointment of the Twelve Apostles and his Great Commission

In Christianity, the Great Commission is the instruction of the resurrected Jesus Christ to his disciples to spread the gospel to all the nations of the world. The Great Commission is outlined in Matthew 28:16– 20, where on a mountain i ...

of the apostles, instructing them to continue his work.[Kreeft, p. 980.] The book Acts of Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

, tells of the founding of the Christian church and the spread of its message to the Roman empire. The Catholic Church teaches that its public ministry began on Pentecost

Pentecost (also called Whit Sunday, Whitsunday or Whitsun) is a Christian holiday which takes place on the 50th day (the seventh Sunday) after Easter Sunday. It commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers o ...

, occurring fifty days following the date Christ is believed to have resurrected.college of bishops

College of Bishops, also known as the Ordo of Bishops, is a term used in the Catholic Church to denote the collection of those bishops who are in communion with the Pope. Under Canon Law, a college is a collection (Latin collegium) of person ...

, led by the bishop of Rome

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop i ...

are the successors to the Apostles.

In the account of the Confession of Peter

In Christianity, the Confession of Peter (translated from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ''Confessio Petri'') refers to an episode in the New Testament in which the Apostle Peter proclaims Jesus to be the Christ ( Jewish Messiah ...

found in the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and ...

, Christ designates Peter as the "rock" upon which Christ's church will be built. The Catholic Church considers the bishop of Rome, the pope, to be the successor to Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupa ...

. Some scholars state Peter was the first bishop of Rome.[ and that later writers retrospectively applied the term "bishop of Rome" to the most prominent members of the clergy in the earlier period and also to Peter himself.][ On this basis, ]Oscar Cullmann

Oscar Cullmann (25 February 1902, Strasbourg – 16 January 1999, Chamonix) was a French Lutheran theologian. He is best known for his work in the ecumenical movement and was partly responsible for the establishment of dialogue between the Luthe ...

, Henry Chadwick, and Bart D. Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books, includin ...

question whether there was a formal link between Peter and the modern papacy. Raymond E. Brown

Raymond Edward Brown (May 22, 1928 – August 8, 1998) was an American Sulpician priest and prominent biblical scholar. He was regarded as a specialist concerning the hypothetical " Johannine community", which he speculated contributed to the ...

also says that it is anachronistic to speak of Peter in terms of local bishop of Rome, but that Christians of that period would have looked on Peter as having "roles that would contribute in an essential way to the development of the role of the papacy in the subsequent church". These roles, Brown says, "contributed enormously to seeing the bishop of Rome, the bishop of the city where Peter died and where Paul witnessed the truth of Christ, as the successor of Peter in care for the church universal".

Antiquity and Roman Empire

Conditions in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

facilitated the spread of new ideas. The empire's network of roads and waterways facilitated travel, and the ''Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a period and as a golden age of increased as well as sustained Roman imperialism, relative peace and order, prosperous stability ...

'' made travelling safe. The empire encouraged the spread of a common culture with Greek roots, which allowed ideas to be more easily expressed and understood.

Unlike most religions in the Roman Empire, however, Christianity required its adherents to renounce all other gods, a practice adopted from Judaism (see Idolatry). The Christians' refusal to join pagan celebrations meant they were unable to participate in much of public life, which caused non-Christians—including government authorities—to fear that the Christians were angering the gods and thereby threatening the peace and prosperity of the Empire. The resulting persecutions were a defining feature of Christian self-understanding until Christianity was legalized in the 4th century.[MacCulloch, ''Christianity'', pp. 155–159, 164.]

In 313,

In 313, Emperor Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterranea ...

's Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

legalized Christianity, and in 330 Constantine moved the imperial capital to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, modern Istanbul, Turkey

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_in ...

. In 380 the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds such as Arianism a ...

made Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

the state church of the Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion ...

, a position that within the diminishing territory of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

would persist until the empire itself ended in the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

in 1453, while elsewhere the church was independent of the empire, as became particularly clear with the East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, ...

. During the period of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, five primary sees emerged, an arrangement formalized in the mid-6th century by Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

as the pentarchy

Pentarchy (from the Greek , ''Pentarchía'', from πέντε ''pénte'', "five", and ἄρχειν ''archein'', "to rule") is a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I (527–565) of the Roman Empire. In this ...

of Rome, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

.Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bi ...

, in a canon of disputed validity,see of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

to a position "second in eminence and power to the bishop of Rome".[Noble, p. 214.] From c. 350 to c. 500, the bishops, or popes, of Rome, steadily increased in authority through their consistent intervening in support of orthodox leaders in theological disputes, which encouraged appeals to them.["Rome (early Christian)". Cross, F. L., ed., ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005] Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renova ...

, who in the areas under his control definitively established a form of caesaropapism

Caesaropapism is the idea of combining the social and political power of secular government with religious power, or of making secular authority superior to the spiritual authority of the Church; especially concerning the connection of the Chu ...

, in which "he had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church", re-established imperial power over Rome and other parts of the West, initiating the period termed the Byzantine Papacy

The Byzantine Papacy was a period of Byzantine domination of the Roman papacy from 537 to 752, when popes required the approval of the Byzantine Emperor for episcopal consecration, and many popes were chosen from the '' apocrisiarii'' (liaisons ...

(537–752), during which the bishops of Rome, or popes, required approval from the emperor in Constantinople or from his representative in Ravenna for consecration, and most were selected by the emperor from his Greek-speaking subjects, resulting in a "melting pot" of Western and Eastern Christian traditions in art as well as liturgy.

Most of the Germanic tribes who in the following centuries invaded the Roman Empire had adopted Christianity in its Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by G ...

form, which the Catholic Church declared heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. The resulting religious discord between Germanic rulers and Catholic subjects was avoided when, in 497, Clovis I, the Frankish ruler, converted to orthodox Catholicism, allying himself with the papacy and the monasteries. The Visigoths in Spain followed his lead in 589, and the Lombards in Italy in the course of the 7th century.

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Y� ...

, particularly through its monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone ( hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

, was a major factor in preserving classical civilization

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, with its art (see Illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, th ...

) and literacy.Rule

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Education

* Royal University of Law and Economics (RULE), a university in Cambodia

Human activity

* The exercise of political or personal control by someone with authority or power

* Business rule, a rule pert ...

, Benedict of Nursia

Benedict of Nursia ( la, Benedictus Nursiae; it, Benedetto da Norcia; 2 March AD 480 – 21 March AD 548) was an Italian Christian monk, writer, and theologian who is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Ori ...

(–543), one of the founders of Western monasticism

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural e ...

, exerted an enormous influence on European culture through the appropriation of the monastic spiritual heritage of the early Catholic Church and, with the spread of the Benedictine tradition, through the preservation and transmission of ancient culture. During this period, monastic Ireland became a centre of learning and early Irish missionaries such as Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

and Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is tod ...

spread Christianity and established monasteries across continental Europe.[

]

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The Catholic Church was the dominant influence on Western civilization from

The Catholic Church was the dominant influence on Western civilization from Late Antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English has ...

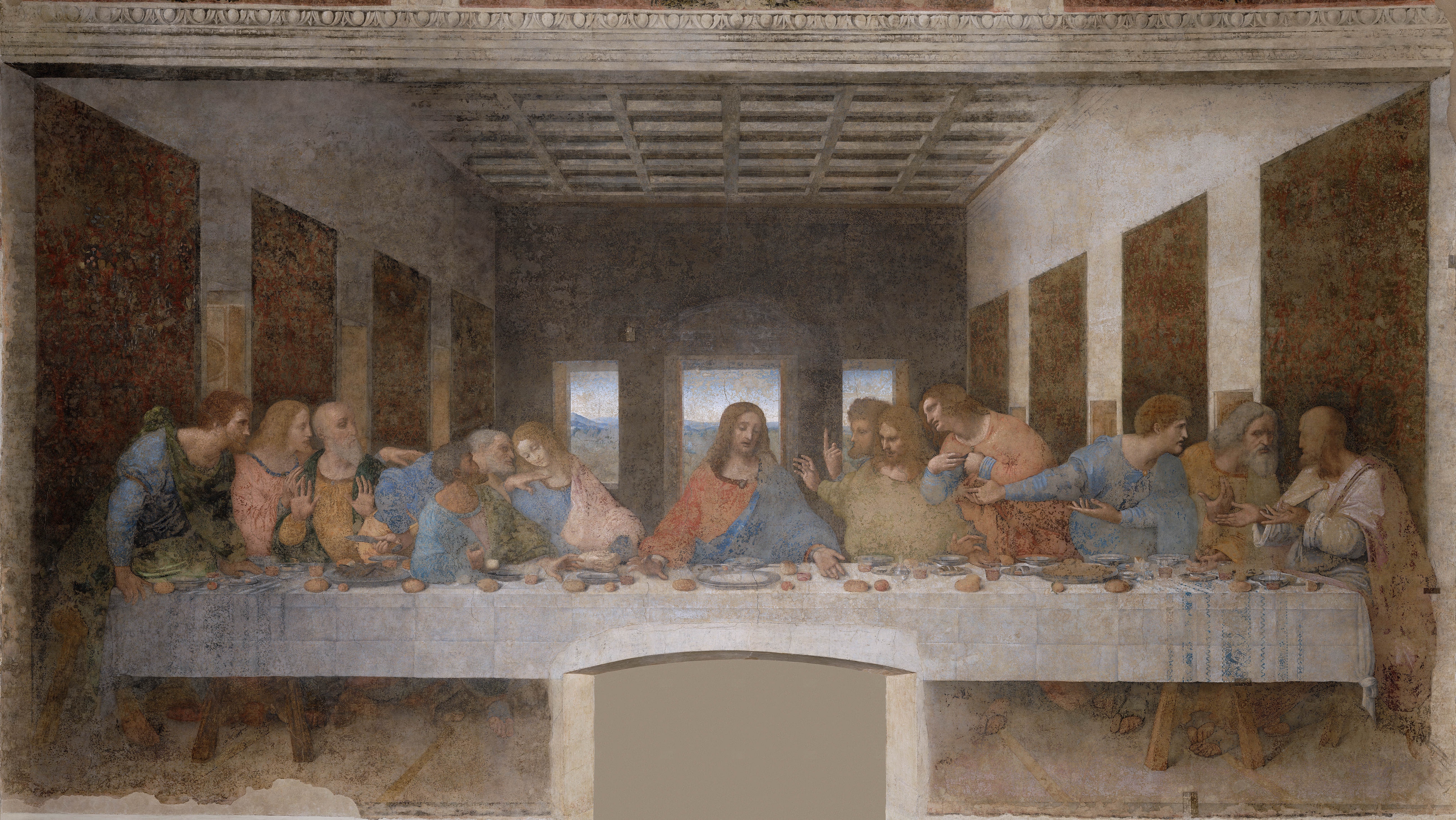

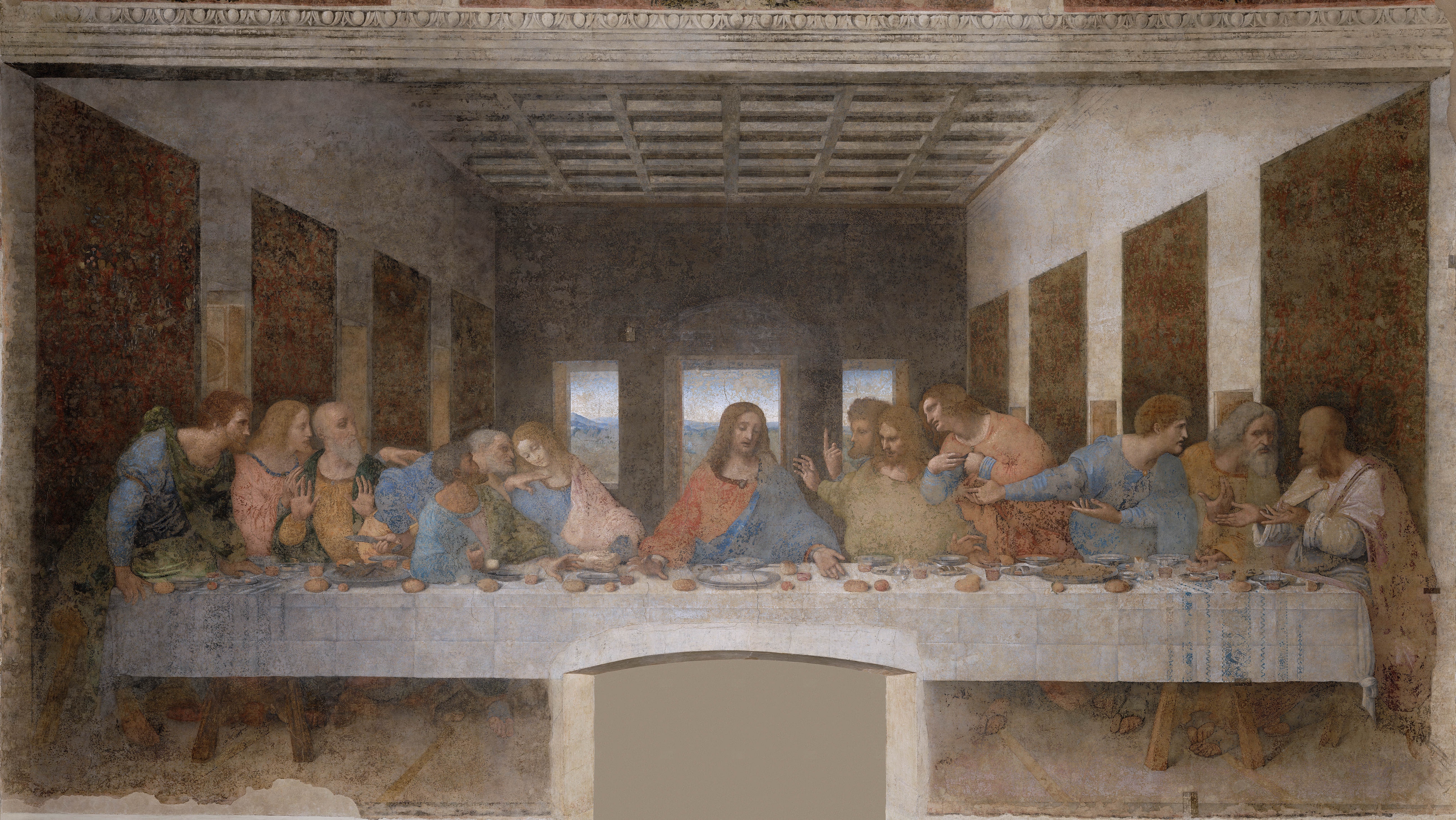

to the dawn of the modern age.Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

, Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

, Botticelli

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi ( – May 17, 1510), known as Sandro Botticelli (, ), was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli's posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered ...

, Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico (born Guido di Pietro; February 18, 1455) was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, described by Vasari in his '' Lives of the Artists'' as having "a rare and perfect talent".Giorgio Vasari, ''Lives of the Artists''. Pengu ...

, Tintoretto

Tintoretto ( , , ; born Jacopo Robusti; late September or early October 1518Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.31 May 1594) was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed wit ...

, Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian (Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, n ...

, Bernini

Gian Lorenzo (or Gianlorenzo) Bernini (, , ; Italian Giovanni Lorenzo; 7 December 159828 November 1680) was an Italian sculptor and architect. While a major figure in the world of architecture, he was more prominently the leading sculptor of his ...

and Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio, known as simply Caravaggio (, , ; 29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610), was an Italian painter active in Rome for most of his artistic life. During the final four years of hi ...

are examples of the numerous visual artists sponsored by the church. Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization

human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Clemetino Inv305.jpg, upPlato, arguably the most influential figure in all of Western philosoph ...

".

The massive Islamic invasions of the mid-7th century began a long struggle between Christianity and Islam

Christianity and Islam are the two largest religions in the world, with 2.8 billion and 1.9 billion adherents, respectively. Both religions are considered as Abrahamic, and are monotheistic, originating in the Middle East.

Christianity de ...

throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

soon lost the lands of the eastern patriarchate

Patriarchate ( grc, πατριαρχεῖον, ''patriarcheîon'') is an ecclesiological term in Christianity, designating the office and jurisdiction of an ecclesiastical patriarch.

According to Christian tradition three patriarchates were est ...

s of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

and Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and was reduced to that of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, the empire's capital. As a result of Islamic domination of the Mediterranean, the Frankish state, centred away from that sea, was able to evolve as the dominant power that shaped the Western Europe of the Middle Ages. The battles of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger Regions of France, region of Occitania (administrative region), Occitania. The city is on t ...

and Poitiers

Poitiers (, , , ; Poitevin: ''Poetàe'') is a city on the River Clain in west-central France. It is a commune and the capital of the Vienne department and the historical centre of Poitou. In 2017 it had a population of 88,291. Its agglome ...

halted the Islamic advance in the West and the failed siege of Constantinople

The following is a list of sieges of Constantinople, a historic city located in an area which is today part of Istanbul, Turkey. The city was built on the land that links Europe to Asia through Bosporus and connects the Sea of Marmara and the Bl ...

halted it in the East. Two or three decades later, in 751, the Byzantine Empire lost to the Lombards the city of Ravenna from which it governed the small fragments of Italy, including Rome, that acknowledged its sovereignty. The fall of Ravenna meant that confirmation by a no longer existent exarch was not asked for during the election in 752 of Pope Stephen II

Pope Stephen II ( la, Stephanus II; 714 – 26 April 757) was born a Roman aristocrat and member of the Orsini family. Stephen was the bishop of Rome from 26 March 752 to his death. Stephen II marks the historical delineation between the Byzant ...

and that the papacy was forced to look elsewhere for a civil power to protect it. In 754, at the urgent request of Pope Stephen, the Frankish king Pepin the Short

the Short (french: Pépin le Bref; – 24 September 768), also called the Younger (german: Pippin der Jüngere), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian to become king.

The younger was the son of ...

conquered the Lombards. He then gifted

Intellectual giftedness is an intellectual ability significantly higher than average. It is a characteristic of children, variously defined, that motivates differences in school programming. It is thought to persist as a trait into adult life, wit ...

the lands of the former exarchate to the pope, thus initiating the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

. Rome and the Byzantine East would delve into further conflict during the Photian schism

The Photian Schism was a four-year (863–867) schism between the episcopal sees of Rome and Constantinople. The issue centred on the right of the Byzantine Emperor to depose and appoint a patriarch without approval from the papacy.

In 857, ...

of the 860s, when Photius

Photios I ( el, Φώτιος, ''Phōtios''; c. 810/820 – 6 February 893), also spelled PhotiusFr. Justin Taylor, essay "Canon Law in the Age of the Fathers" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materia ...

criticized the Latin west of adding of the ''filioque

( ; ) is a Latin term ("and from the Son") added to the original Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (commonly known as the Nicene Creed), and which has been the subject of great controversy between Eastern and Western Christianity. It is a t ...

'' clause after being excommunicated by Nicholas I. Though the schism was reconciled, unresolved issues would lead to further division.

In the 11th century, the efforts of Hildebrand of Sovana

Pope Gregory VII ( la, Gregorius VII; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana ( it, Ildebrando di Soana), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint ...

led to the creation of the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appo ...

to elect new popes, starting with Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform ...

in the papal election of 1061. When Alexander II died, Hildebrand was elected to succeed him, as Pope Gregory VII. The basic election system of the College of Cardinals which Gregory VII helped establish has continued to function into the 21st century. Pope Gregory VII further initiated the Gregorian Reforms

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be nam ...

regarding the independence of the clergy from secular authority. This led to the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest ( German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monas ...

between the church and the Holy Roman Emperors, over which had the authority to appoint bishops and popes.[Vidmar, ''The Catholic Church Through the Ages'' (2005), pp. 107–11][Duffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), p. 78, quote: "By contrast, Paschal's successor Eugenius II (824–7), elected with imperial influence, gave away most of these papal gains. He acknowledged the Emperor's sovereignty in the papal state, and he accepted a constitution imposed by Lothair which established imperial supervision of the administration of Rome, imposed an oath to the Emperor on all citizens, and required the pope–elect to swear fealty before he could be consecrated. Under Sergius II (844–7) it was even agreed that the pope could not be consecrated without an imperial mandate and that the ceremony must be in the presence of his representative, a revival of some of the more galling restrictions of Byzantine rule."]

In 1095, Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

emperor Alexius I

Alexios I Komnenos ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξιος Κομνηνός, 1057 – 15 August 1118; Latinized Alexius I Comnenus) was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during ...

appealed to Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

for help against renewed Muslim invasions in the Byzantine–Seljuk Wars

The Byzantine–Seljuk wars were a series of decisive battles that shifted the balance of power in Asia Minor and Syria from the Byzantine Empire to the Seljuks. Riding from the steppes of Central Asia, the Seljuks replicated tactics practiced ...

,[Riley-Smith, p. 8] which caused Urban to launch the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

aimed at aiding the Byzantine Empire and returning the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Ho ...

to Christian control. In the 11th century

The 11th century is the period from 1001 ( MI) through 1100 ( MC) in accordance with the Julian calendar, and the 1st century of the 2nd millennium.

In the history of Europe, this period is considered the early part of the High Middle Ages. ...

, strained relations between the primarily Greek church and the Latin Church separated them in the East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, ...

, partially due to conflicts over papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

authority. The Fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople by renegade crusaders proved the final breach. In this age great gothic cathedrals in France were an expression of popular pride in the Christian faith.

In the early 13th century mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christiani ...

and Dominic de Guzmán

Saint Dominic ( es, Santo Domingo; 8 August 1170 – 6 August 1221), also known as Dominic de Guzmán (), was a Castilian Catholic priest, mystic, the founder of the Dominican Order and is the patron saint of astronomers and natural scientis ...

. The ''studia conventualia'' and '' studia generalia'' of the mendicant orders played a large role in the transformation of Church-sponsored cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

s and palace schools, such as that of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Em ...

at Aachen, into the prominent universities of Europe. Scholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

theologians and philosophers such as the Dominican priest Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

studied and taught at these studia. Aquinas' ''Summa Theologica'' was an intellectual milestone in its synthesis of the legacy of ancient Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

such as Plato and Aristotle with the content of Christian revelation.

A growing sense of church-state conflicts marked the 14th century. To escape instability in Rome, Clement V

Pope Clement V ( la, Clemens Quintus; c. 1264 – 20 April 1314), born Raymond Bertrand de Got (also occasionally spelled ''de Guoth'' and ''de Goth''), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 5 June 1305 to his de ...

in 1309 became the first of seven popes to reside in the fortified city of Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label=Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune ha ...

in southern France[Duffy, ''Saints and Sinners'' (1997), p. 122] during a period known as the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon – at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire; now part of France – rather than in Rome. The situation arose ...

. The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376 when the pope returned to Rome,[Morris, p. 232] but was followed in 1378 by the 38-year-long Western schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

, with claimants to the papacy in Rome, Avignon and (after 1409) Pisa.Council of Constance

The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...

, with the claimants in Rome and Pisa agreeing to resign and the third claimant excommunicated by the cardinals, who held a new election naming Martin V

Pope Martin V ( la, Martinus V; it, Martino V; January/February 1369 – 20 February 1431), born Otto (or Oddone) Colonna, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 11 November 1417 to his death in February 1431. Hi ...

pope.[McManners, p. 240]

In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focussed on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches. Several eastern churches reunited, forming the majority of the

In 1438, the Council of Florence convened, which featured a strong dialogue focussed on understanding the theological differences between the East and West, with the hope of reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox churches. Several eastern churches reunited, forming the majority of the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

.

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery