The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the

Playa Girón

:''Note: "Playa Girón" is also the title of a song included in the album "Días y Flores", by Silvio Rodriguez.''

Playa Girón (; "Girón beach") is a beach and village on the east bank of the Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), which is located in ...

) was a failed military

landing operation on the southwestern coast of

Cuba in 1961 by

Cuban exiles, covertly financed and directed by the

United States. It was aimed at overthrowing

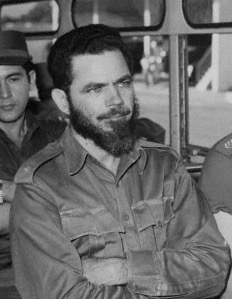

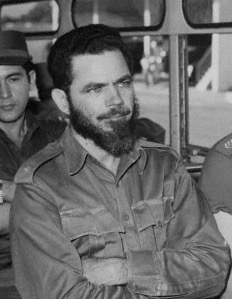

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

's communist government. The operation took place at the height of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, and its failure influenced relations between Cuba, the United States, and the

Soviet Union.

In December 1958, American ally General

Fulgencio Batista was deposed by Castro's

26th of July Movement

The 26th of July Movement ( es, Movimiento 26 de Julio; M-26-7) was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization and later a political party led by Fidel Castro. The movement's name commemorates its 26 July 1953 attack on the army barracks on San ...

during the

Cuban Revolution. Castro nationalized American businesses—including banks, oil refineries, and sugar and coffee plantations—then severed Cuba's formerly close relations with the United States and reached out to its Cold War rival, the Soviet Union. The

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began planning the overthrow of Castro, which U.S. President

Dwight D. Eisenhower approved in March 1960. Cuban exiles who had moved to the U.S. following Castro's takeover had formed the

counter-revolutionary military unit,

Brigade 2506, which was the armed wing of the

Democratic Revolutionary Front (DRF). The CIA funded the brigade, which also included some

U.S. military

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

personnel, and trained the unit in

Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

.

1,500 troops, divided into five infantry

battalions and one paratrooper battalion, assembled and launched from Guatemala and

Nicaragua by boat on 17 April 1961. Two days earlier, eight CIA-supplied

B-26 bombers had attacked Cuban airfields and then returned to the U.S. On the night of 17 April, the main invasion force landed on the beach at

Playa Girón

:''Note: "Playa Girón" is also the title of a song included in the album "Días y Flores", by Silvio Rodriguez.''

Playa Girón (; "Girón beach") is a beach and village on the east bank of the Bahia de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), which is located in ...

in the

Bay of Pigs

The Bay of Pigs ( es, Bahía de los Cochinos) is an inlet of the Gulf of Cazones located on the southern coast of Cuba. By 1910, it was included in Santa Clara Province, and then instead to Las Villas Province by 1961, but in 1976, it was reas ...

, where it overwhelmed a local revolutionary militia. Initially,

José Ramón Fernández led the

Cuban Army counter-offensive; later, Castro took personal control. As the invasion force lost the strategic initiative, U.S. President

John F. Kennedy decided to withhold further air support after the international community became aware of the operation. The plan, devised during Eisenhower's presidency, had required involvement of both air and naval forces. Without further air support, the invasion was being conducted with fewer forces than the CIA had deemed necessary. The invading force was defeated within three days by the

Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces and surrendered on 20 April. Most of the surrendered troops were publicly interrogated and put into Cuban prisons.

The invasion was a

U.S. foreign policy failure. The Cuban government's victory solidified Castro's role as a national hero and widened the political division between the two formerly allied countries. It also pushed Cuba closer to the Soviet Union, setting the stage for the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

in 1962.

Background

United States interventions in Cuba

Since the middle of the 18th century, Cuba had been part of the

Spanish colonial empire. In the late 19th century, Cuban nationalist revolutionaries rebelled against Spanish dominance, resulting in three liberation wars: the

Ten Years' War (1868–1878), the

Little War (1879–1880) and the

Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (), fought from 1895 to 1898, was the last of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Ten Years' War (1868–1878) and the Little War (1879–1880). The final three months ...

(1895–1898). In 1898, the United States government proclaimed war on the Spanish Empire, resulting in the

Spanish–American War. The U.S. subsequently invaded the island and forced the

Spanish army

The Spanish Army ( es, Ejército de Tierra, lit=Land Army) is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies — dating back to the late 15th century.

The ...

out. Of note, a special operations attempt to land a group of at least 375 Cuban soldiers on the island succeeded in the

Battle of Tayacoba

The Battle of Tayacoba, June 30, 1898, (also spelled Tayabacao) was an American special operations effort to land supplies and reinforcements to Cuban rebels fighting for their independence in the Spanish–American War.

Background

On June 25 ...

. On 20 May 1902, a new independent government proclaimed the foundation of the

Republic of Cuba, with U.S. Military Governor

Leonard Wood handing over control to President

Tomás Estrada Palma, a Cuban-born U.S. citizen.

[ Gott 2004. p. 113.] Subsequently, large numbers of U.S. settlers and businessmen arrived in Cuba, and by 1905, 60% of rural properties were owned by non-Cuban-born North American citizens.

[ Gott 2004. p. 115.] Between 1906 and 1909, 5,000 U.S. Marines were stationed across the island, and returned in 1912, 1917 and 1921 to intervene in internal affairs, sometimes at the behest of the Cuban government.

[ Gott 2004. pp. 115–16.]

Cuban Revolution

In March 1952, a Cuban general and politician, Fulgencio Batista, seized power on the island, proclaimed himself president, and deposed the discredited president Carlos Prío Socarrás of the

Partido Auténtico. Batista canceled the planned presidential elections and described his new system as "disciplined democracy." Although Batista gained some popular support, many Cubans saw it as the establishment of a one-man dictatorship. Many opponents of the Batista regime took to armed rebellion in an attempt to oust the government, sparking the Cuban Revolution. One of these groups was the National Revolutionary Movement (''Movimiento Nacional Revolucionario''), a militant organization containing largely middle-class members that had been founded by the Professor of Philosophy

Rafael García Bárcena

Rafael García Bárcena (June 7, 1908 Guines, Cuba - June 13, 1964) was a Cuban philosopher who later took a leading role in the Cuban Revolution against President Fulgencio Batista. A Professor of Philosophy, he founded the National Revolutiona ...

. Another was the

Directorio Revolucionario Estudantil

Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil (abbreviation: DRE; English: Student Revolutionary Directorate) was a Cuban student activist group which in opposition to Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista from 1954 to 1957 played a role in the Cuban Revolut ...

, which had been founded by the Federation of University Students President

José Antonio Echevarría

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

. However, the best known of these anti-Batista groups was the "26th of July Movement" (MR-26-7), founded by Fidel Castro. With Castro as the MR-26-7's head, the organization was based upon a

clandestine cell system

A clandestine cell system is a method for organizing a group of people (such as resistance fighters, sleeper agents, mobsters, or terrorists) such that such people can more effectively resist penetration by an opposing organization (such as l ...

, with each cell containing ten members, none of whom knew the whereabouts or activities of the other cells.

Between December 1956 and 1959, Castro led a guerrilla army against the forces of Batista from his base camp in the

Sierra Maestra mountains. Batista's repression of revolutionaries had earned him widespread unpopularity, and by 1958 his armies were in retreat. On 31 December 1958, Batista resigned and fled into exile, taking with him an amassed fortune of more than US$300,000,000.

[ Coltman 2003. p. 137.] The presidency fell to Castro's chosen candidate, the lawyer

Manuel Urrutia Lleó, while members of the MR-26-7 took control of most positions in the cabinet. On 16 February 1959, Castro took on the role of

Prime Minister. Dismissing the need for elections, Castro proclaimed the new administration an example of

direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate decides on policy initiatives without legislator, elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently establishe ...

, in which the Cuban populace could assemble ''en masse'' at demonstrations and express their democratic will to him personally. Critics instead condemned the new regime as undemocratic.

Post-revolutionary government

After the success of the revolution a popular uproar across Cuba demanded that those figures who had been complicit in the widespread torture and killing of civilians be brought to justice. Although he remained a moderating force and tried to prevent the mass reprisal killings of Batistanos advocated by many Cubans, Castro helped to set up trials of many figures involved in the old regime across the country, resulting in hundreds of executions. Critics, in particular from the U.S. press, argued that many of these did not meet the standards of a

fair trial, and condemned Cuba's new government as being more interested in vengeance than justice. Castro retaliated strongly against such accusations, proclaiming that "revolutionary justice is not based on legal precepts, but on moral conviction." In a show of support for this "revolutionary justice," he organized the first

Havana trial to take place before a mass audience of 17,000 at the

Sports Palace stadium. When a group of aviators accused of bombing a village was found not guilty, he ordered a retrial, in which they were instead found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment.

In early January 1959, Fidel Castro appointed various economists such as

Felipe Pazos,

Rufo López-Fresquet, Ernesto Bentacourt, Faustino Pérez, and

Manuel Ray Rivero

Manuel Ray Rivero (1924 – November 12, 2013) was a Cuban born engineer, politician and revolutionary, who was later involved in civic and professional actitivities in Puerto Rico. He received a scholarship from the Cuban Ministry of Public W ...

. By June 1959, these appointed economists would begin to express disillusionment with Castro's proposed economic policies.

In early 1959, the Cuban government began agrarian reforms which redistributed the ownership of Cuba's land. Expropriated lands would be put into state ownership and the newly formed Instituto de la Reforma Agraria (INRA) was to oversee the expropriations and be headed by Fidel Castro. In

Camagüey Province there was growing opposition to the Cuban government due to the resistance of conservative farmers to the agrarian reforms and distaste for

Raul Castro and

Che Guevara's promotion of communist ideals in the local government and military. The anti-communist opposition within the Cuban government assumed that Fidel Castro was unaware of growing communist influence because of Fidel Castro's frequent public disavowals of communism.

On July 17, 1959, Conrado Bécquer, the sugar workers' leader demanded Cuban President Urrutia's resignation. Castro himself resigned as

Prime Minister of Cuba in protest, but later that day appeared on television to deliver a lengthy denouncement of Urrutia, claiming that Urrutia "complicated" government, and that his "fevered anti-Communism" was having a detrimental effect. Castro's sentiments received widespread support as organized crowds surrounded the presidential palace demanding Urrutia's resignation, which was duly received. On July 23, Castro resumed his position as premier and appointed loyalist

Osvaldo Dorticós as the new president.

Prelude

Huber Matos affair

On October 20, 1959, Cuban army commander and veteran of the

Cuban Revolution:

Huber Matos, resigned and accused

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

of "burying the revolution". Fifteen of Matos' officers resigned with him. Immediately after the resignation, Castro critiqued Matos and accused him of disloyalty, then sent

Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 ''Granma (yacht), Granma'' ...

to arrest Matos and his accompanying officers. Matos and the officers were taken to Havana and imprisoned in

La Cabaña. Cuban communists later claimed Matos was helping plan a counter-revolution organized by the American

Central Intelligence Agency and other Castro opponents, an operation that became the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

The scandal is noted for its occurrence alongside a greater trend of removals of Castro's former collaborators in the revolution. It marked a turning point where Castro was beginning to exert more personal control over the new government in Cuba. Matos' arresting officer and former collaborator of Castro,

Camilo Cienfuegos

Camilo Cienfuegos Gorriarán (; 6 February 1932 – 28 October 1959) was a Cuban revolutionary born in Havana. Along with Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Juan Almeida Bosque, and Raúl Castro, he was a member of the 1956 ''Granma (yacht), Granma'' ...

, would soon die in a mysterious plane crash shortly after the incident.

Shortly after Matos' arrest, the prime minister and

Che Guevara made a speech to members of the INRA that Cuba would continue to turn in a socialist direction.

Manuel Artime

Manuel Francisco Artime Buesa, M.D. (29 January 1932 – 18 November 1977) was a Cuban-American who at one time was a member of the rebel army of Fidel Castro but later was the political leader of Brigade 2506 land forces in the abortive Bay of ...

viewed the arrest of Matos and affirmation of socialism in Cuba as precedent for him to resign. On 7 November 1959 his resignation letter from INRA and the revolutionary army was published on the front page of ''Avance'' newspaper, one of the last newspapers not controlled by the government. Artime then entered an underground organization run by Jesuits in Cuba to hide fugitives; it is unclear what exactly made Artime immediately turn to hiding and later defect. While in a Havana safehouse Artime would form the

Movement for Revolutionary Recovery

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

with other dissidents. Artime then contacted the American embassy in Havana, and on 14 December 1959, the CIA arranged for him to travel to the US on a Honduran freighter ship. He became closely involved with

Gerry Droller

Gerard "Gerry" Droller (1905? - 1992) was a German CIA officer involved in the covert 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and the recruitment of Cuban exiles in the preparation of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961.

Biography

Gerard Droller was born ...

(alias ''Frank Bender'', alias "Mr B") of the CIA in recruiting and organizing Cuban exiles in Miami for future actions against the Cuban government. Artime's organization MRR thus grew to become the principal counter-revolutionary movement inside Cuba, with supporting members in Miami, Mexico, Venezuela etc. Involved were

Tony Varona

Manuel Antonio de Varona y Loredo (November 25, 1908 in Camagüey, Cuba – October 29, 1992 in Miami, Florida, United States) was a Cuban lawyer and politician.

Career

Varona is 7th Prime Minister of Cuba in 1948–1950, and served as preside ...

,

José Miró Cardona,

Rafael Quintero

Rafael "Chi Chi" Quintero Ibaria (September 16, 1940 – October 1, 2006) was a CIA operative.

Biography

Quintero was born in Camagüey, Cuba on September 16, 1940. In the 1950s, he joined the resistance movement against Cuban dictator Fulge ...

, Aureliano Arango. Infiltration into Cuba, arms drops, etc. were arranged by the CIA.

[Rodriguez (1999)][Johnson (1964)]Manuel Artime

Manuel Francisco Artime Buesa, M.D. (29 January 1932 – 18 November 1977) was a Cuban-American who at one time was a member of the rebel army of Fidel Castro but later was the political leader of Brigade 2506 land forces in the abortive Bay of ...

became the future leader of

Brigade 2506 in the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He gained this position from the notoriety he gained after defecting and engaging in a tour of Latin America denouncing the new government in Cuba. This notoriety as a Cuban dissident gave him credit to be picked as the leader for the invasion when it was first conceived by the CIA.

[

]

Sanctions and assassination attempts

Castro's Cuban government ordered the country's oil refineries – then controlled by U.S. corporations

Castro's Cuban government ordered the country's oil refineries – then controlled by U.S. corporations Esso

Esso () is a trading name for ExxonMobil. Originally, the name was primarily used by its predecessor Standard Oil of New Jersey after the breakup of the original Standard Oil company in 1911. The company adopted the name "Esso" (the phonetic p ...

, Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

, and Shell – to process crude oil purchased from the Soviet Union, but under pressure from the U.S. government, these companies refused. Castro responded by expropriating the refineries and nationalizing them under state control. In retaliation, the U.S. canceled its import of Cuban sugar, provoking Castro to nationalize most U.S.-owned assets, including banks and sugar mills. Relations between Cuba and the U.S. were further strained following the explosion and sinking of a French vessel, the ''Le Coubre

The French freighter ''La Coubre'' () exploded in the harbour of Havana, Cuba, on 4 March 1960 while it was unloading 76 tons of grenades and munitions. Seventy-five to 100 people were killed, and many were injured. Fidel Castro alleged it w ...

'', in Havana Harbor in March 1960. The cause of the explosion was never determined, but Castro publicly mentioned that the U.S. government was guilty of sabotage. On 13 October 1960, the U.S. government then prohibited the majority of exports to Cuba – the exceptions being medicines and certain foodstuffs – marking the start of an economic embargo. In retaliation, the Cuban National Institute for Agrarian Reform took control of 383 private-run businesses on 14 October, and on 25 October a further 166 U.S. companies operating in Cuba had their premises seized and nationalized, including Coca-Cola and Sears Roebuck.[ Bourne 1986. p. 214.] On 16 December, the U.S. ended its import quota of Cuban sugar.[ Bourne 1986. p. 215.]

The U.S. government was becoming increasingly critical of Castro's revolutionary government. At an August 1960 meeting of the Organization of American States

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

(OAS) held in Costa Rica, U.S. Secretary of State Christian Herter publicly proclaimed that Castro's administration was "following faithfully the Bolshevik pattern" by instituting a single-party political system, taking governmental control of trade unions, suppressing civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

, and removing both the freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

and freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic News media, media, especially publication, published materials, should be conside ...

. He furthermore asserted that international communism was using Cuba as an "operational base" for spreading revolution in the western hemisphere, and called on other OAS members to condemn the Cuban government for its breach of human rights. In turn, Castro lambasted the treatment of black people and the working classes he had witnessed in New York City, which he ridiculed as that "superfree, superdemocratic, superhumane, and supercivilized city." Proclaiming that the U.S. poor were living "in the bowels of the imperialist monster," he attacked the mainstream U.S. media and accused it of being controlled by big business. Superficially the U.S. was trying to improve its relationship with Cuba. Several negotiations between representatives from Cuba and the U.S. took place around this time. Repairing international financial relations was the focal point of these discussions. Political relations were another hot topic of these conferences. The U.S. stated that they would not interfere with Cuba's domestic affairs but that the island should limit its ties with the Soviet Union.

Tensions percolated when the CIA began to act on its desires to snuff out Castro. Efforts to assassinate Castro officially commenced in 1960,Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

, set up to investigate CIA abuses, released a report entitled "Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders".Raúl Castro

Raúl Modesto Castro Ruz (; ; born 3 June 1931) is a retired Cuban politician and general who served as the first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, the most senior position in the one-party communist state, from 2011 to 2021, succeedi ...

, and Che Guevara. In exchange, if the operation were a success and a pro-U.S. government were restored in Cuba, the CIA agreed that the Mafia would get their "monopoly on gaming, prostitution and drugs". In 1963, at the same time the Kennedy administration initiated secret peace overtures to Castro, Cuban revolutionary and undercover CIA agent Rolando Cubela

Rolando Cubela Secades (19 January 1933 – 23 August 2022) was a Cuban revolutionary leader who played a vital part in the Cuban Revolution, having been a founding member of the Directorio Revolucionario Estudiantil and later the military lea ...

was tasked with killing Castro by CIA official Desmond Fitzgerald, who portrayed himself as a personal representative of Robert F. Kennedy.

United States foreign policy debate

The U.S. initially recognized Castro's government after the Cuban Revolution ousted Batista,

The U.S. initially recognized Castro's government after the Cuban Revolution ousted Batista,[ Ambrose 2007. pp. 475.] but the relationship quickly soured as Castro repeatedly condemned the U.S. in his speeches for its misdeeds in Cuba over the previous 60 years.

Internal opposition to Fidel Castro

Soon after the success of the Cuban Revolution, militant counter-revolutionary groups developed in an attempt to overthrow the new regime. Undertaking armed attacks against government forces, some set up guerrilla bases in Cuba's mountainous regions, leading to the six-year Escambray Rebellion. These dissidents were funded and armed by various foreign sources, including the exiled Cuban community, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and

Soon after the success of the Cuban Revolution, militant counter-revolutionary groups developed in an attempt to overthrow the new regime. Undertaking armed attacks against government forces, some set up guerrilla bases in Cuba's mountainous regions, leading to the six-year Escambray Rebellion. These dissidents were funded and armed by various foreign sources, including the exiled Cuban community, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and Rafael Trujillo

Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina ( , ; 24 October 189130 May 1961), nicknamed ''El Jefe'' (, "The Chief" or "The Boss"), was a Dominican dictator who ruled the Dominican Republic from February 1930 until his assassination in May 1961. He ser ...

's regime in the Dominican Republic.[ Ros 2006. pp. 159–201.]

No quarter was given during the suppression of the resistance in the Escambray Mountains

The Escambray Mountains () are a mountain range in the central region of Cuba, in the provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos and Villa Clara.

Overview

The Escambray Mountains are located in the south-central region of the island, extending ab ...

, where former rebels from the war against Batista took different sides. On 3 April 1961, a bomb attack on militia barracks in Bayamo

Bayamo is the capital city of the Granma Province of Cuba and one of the largest cities in the Oriente region.

Overview

The community of Bayamo lies on a plain by the Bayamo River. It is affected by the violent Bayamo wind.

One of the most ...

killed four militia and wounded eight more. On 6 April, the Hershey Sugar factory in Matanzas

Matanzas (Cuban ) is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas. Known for its poets, culture, and Afro-Cuban folklore, it is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Matanzas (Spanish ''Bahia de Matanzas''), east ...

was destroyed by sabotage.[Corzo (2003), pp. 79–90] On 14 April 1961, guerrillas led by Agapito Rivera fought Cuban government forces in Villa Clara Province, where several government troops were killed and others wounded.[Thomas (1971)]

Preparation

Early plans

The idea of overthrowing Castro's government emerged within the CIA in early 1960. Founded in 1947 by the National Security Act, the CIA was "a product of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

", having been designed to counter the espionage activities of the Soviet Union's own national security agency, the KGB. As the perceived threat of international communism grew larger, the CIA expanded its activities to undertake covert economic, political, and military activities that would advance causes favourable to U.S. interests, often resulting in brutal dictatorships that favored U.S. interests.[ Quirk 1993. p. 303.] CIA Director Allen Dulles was responsible for overseeing covert operations across the world, and although widely considered an ineffectual administrator, he was popular among his employees, whom he had protected from the accusations of McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

. Recognizing that Castro and his government were becoming increasingly hostile and openly opposed to the United States, Eisenhower directed the CIA to begin preparations of invading Cuba and overthrow the Castro regime. Richard M. Bissell Jr. was charged with overseeing plans for the Bay of Pigs Invasion. He assembled agents to aid him in the plot, many of whom had worked on the 1954 Guatemalan coup six years before; these included David Philips

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, Gerry Droller

Gerard "Gerry" Droller (1905? - 1992) was a German CIA officer involved in the covert 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and the recruitment of Cuban exiles in the preparation of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961.

Biography

Gerard Droller was born ...

and E. Howard Hunt

Everette Howard Hunt Jr. (October 9, 1918 – January 23, 2007) was an American intelligence officer and author. From 1949 to 1970, Hunt served as an officer in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), particularly in the United States involvem ...

.

Bissell placed Droller in charge of liaising with anti-Castro segments of the Cuban American community living in the United States, and asked Hunt to fashion a government in exile, which the CIA would effectively control. Hunt proceeded to travel to Havana, where he spoke with Cubans from various backgrounds and discovered a brothel through the Mercedes-Benz agency.[ Quirk 1993. p. 308.] Returning to the U.S., he informed the Cuban Americans with whom he was liaising that they would have to move their base of operations from Florida to Mexico City, because the State Department refused to permit the training of a militia on U.S. soil. Although unhappy with the news, they conceded to the order.

Eisenhower's planning

On 17 March 1960, the CIA put forward their plan for the overthrow of Castro's administration to the U.S. National Security Council, where President Eisenhower lent his support,Eisenhower Library

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum and Boyhood Home is the presidential library and museum of Dwight David Eisenhower, the 34th president of the United States (1953–1961), located in his hometown of Abilene, Kansas. The mu ...

revealed that Eisenhower had not ordered or approved plans for an amphibious assault on Cuba.Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

and John F. Kennedy of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, campaigned on the issue of Cuba, with both candidates taking a hardline stance on Castro. Nixon – who was vice president – insisted that Kennedy should not be informed of the military plans, to which Dulles conceded. To Nixon's chagrin, the Kennedy campaign released a scathing statement on the Eisenhower administration's Cuba policy on 20 October 1960 which said that "we must attempt to strengthen the non-Batista democratic anti-Castro forces ..who offer eventual hope of overthrowing Castro", claiming that "Thus far these fighters for freedom have had virtually no support from our Government."

Kennedy's operational approval

On 28 January 1961, President Kennedy was briefed, together with all the major departments, on the latest plan (code-named ''Operation Pluto''), which involved 1,000 men landed in a ship-borne invasion at Trinidad, Cuba, about 270 km (170 mi) south-east of Havana, at the foothills of the Escambray Mountains in Sancti Spiritus province. Kennedy authorized the active departments to continue and to report progress. Trinidad had good port facilities, it was closer to many existing counter-revolutionary activities, and it offered an escape route into the Escambray Mountains. That scheme was subsequently rejected by the State Department because the airfield there was not large enough for B-26 bombers and, since B-26s were to play a prominent role in the invasion, this would destroy the façade that the invasion was just an uprising with no American involvement. Secretary of State Dean Rusk raised some eyebrows by contemplating airdropping a bulldozer to extend the airfield. Kennedy rejected Trinidad, preferring a more low-key locale. On 4 April 1961, President Kennedy approved the Bay of Pigs plan (also known as ''Operation Zapata''), because it had a sufficiently long airfield, it was farther away from large groups of civilians than the Trinidad plan, and it was less "noisy" militarily, which would make denial of direct U.S. involvement more plausible. The invasion landing area was changed to beaches bordering the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) in Las Villas Province, 150 km southeast of Havana, and east of the Zapata Peninsula

Zapata Peninsula ( es, Península de Zapata) is a large peninsula in Matanzas Province, southern Cuba, at . Ciénaga de Zapata National Park is located on the peninsula.

It is located south of Ensenada de la Broa, east of the gulf of Batabano a ...

. The landings were to take place at Playa Girón (code-named ''Blue Beach''), Playa Larga

Playa (plural playas) may refer to:

Landforms

* Endorheic basin, also known as a sink, alkali flat or sabkha, a desert basin with no outlet which periodically fills with water to form a temporary lake

* Dry lake, often called a ''playa'' in the s ...

(code-named ''Red Beach''), and Caleta Buena Inlet (code-named ''Green Beach'').[Jones (2008)][Higgins (2008)][Faria (2002), pp. 93–98.][Kornbluh (1998)]

Top aides to Kennedy, such as Dean Rusk and both joint chiefs of staff, later said that they had hesitations about the plans but muted their thoughts. Some leaders blamed these problems on the "Cold War mindset" or the determination of the Kennedy brothers to oust Castro and fulfill campaign promises.Cuban Revolutionary Council

The Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC) was a group formed, with CIA assistance, three weeks before the April 17, 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion to "coordinate and direct" the activities of another group known as the Cuban Democratic Revolutionary Front ...

, chaired by José Miró Cardona, former Prime Minister of Cuba. Cardona became the de facto leader-in-waiting of the intended post-invasion Cuban government.

Training

In April 1960, the CIA began to recruit anti-Castro Cuban exiles in the Miami area. Until July 1960, assessment and training was carried out on Useppa Island and at various other facilities in South Florida, such as Homestead Air Force Base. Specialist guerrilla training took place at Fort Gulick and

In April 1960, the CIA began to recruit anti-Castro Cuban exiles in the Miami area. Until July 1960, assessment and training was carried out on Useppa Island and at various other facilities in South Florida, such as Homestead Air Force Base. Specialist guerrilla training took place at Fort Gulick and Fort Clayton

Fort Clayton was a United States Army base in the former Panama Canal Zone, later part of the Republic of Panama.

Base

Fort Clayton was located northwest of Balboa, Panama, with the Panama Canal located nearby. It closed in 1999 pursuant ...

in Panama.[Fernandez (2001)] The force that became Brigade 2506 started with 28 men, who initially were told that their training was being paid for by an anonymous Cuban millionaire émigré, but the recruits soon guessed who was paying the bills, calling their supposed anonymous benefactor "Uncle Sam", and the pretense was dropped. The overall leader was Dr. Manuel Artime

Manuel Francisco Artime Buesa, M.D. (29 January 1932 – 18 November 1977) was a Cuban-American who at one time was a member of the rebel army of Fidel Castro but later was the political leader of Brigade 2506 land forces in the abortive Bay of ...

while the military leader was José "Pepe" Peréz San Román, a former Cuban Army officer imprisoned under both Batista and Castro.

For the increasing number of recruits, infantry training was carried out at a CIA-run base code-named ''JMTrax''. The base was on the Pacific coast of Guatemala between Quetzaltenango and Retalhuleu, in the Helvetia coffee plantation.

For the increasing number of recruits, infantry training was carried out at a CIA-run base code-named ''JMTrax''. The base was on the Pacific coast of Guatemala between Quetzaltenango and Retalhuleu, in the Helvetia coffee plantation.[Hagedorn (2006)] Paratroop training was at a base nicknamed ''Garrapatenango'', near Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. Training for boat handling and amphibious landings took place at Vieques Island, Puerto Rico. Tank training for the Brigade 2506 M41 Walker Bulldog tanks, took place at Fort Knox

Fort Knox is a United States Army installation in Kentucky, south of Louisville and north of Elizabethtown. It is adjacent to the United States Bullion Depository, which is used to house a large portion of the United States' official gold res ...

, Kentucky and Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

, Georgia. Underwater demolition and infiltration training took place at Belle Chasse

Belle Chasse ( ) is a census-designated place (CDP) in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, United States, on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Belle Chasse is part of the Greater New Orleans metropolitan area. The population was 10,579 at the 20 ...

near New Orleans.[ To create a navy, the CIA purchased five cargo ships from the Cuban-owned, Miami-based Garcia Line, thereby giving "]plausible deniability

Plausible deniability is the ability of people, typically senior officials in a formal or informal chain of command, to denial, deny knowledge of or responsibility for any damnable actions committed by members of their organizational hierarchy. Th ...

" as the State Department had insisted no U.S. ships could be involved in the invasion. The first four of the five ships, namely the ''Atlantico'', the ''Caribe'', the ''Houston'' and ''Río Escondido'' were to carry enough supplies and weapons to last thirty days while the ''Lake Charles'' had 15 days of supplies and was intended to land the provisional government of Cuba. The ships were loaded with supplies at New Orleans and sailed to Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua. Additionally, the invasion force had two old Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) ships, the ''Blagar'' and ''Barbara J'' from World War II that were part of the CIA's "ghost ship" fleet and served as command ships for the invasion. The crews of the supply ships were Cuban while the crews of the LCIs were Americans, borrowed by the CIA from the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS). One CIA officer wrote that MSTS sailors were all professional and experienced but not trained for combat. In November 1960, the Retalhuleu recruits took part in quelling an officers' rebellion in Guatemala, in addition to the intervention of the U.S. Navy.[Bay of Pigs, 40 Years After: Chronology](_blank)

. The National Security Archive. The George Washington University. Curtiss C-46

The Curtiss C-46 Commando is a twin-engine transport aircraft derived from the Curtiss CW-20 pressurised high-altitude airliner design. Early press reports used the name "Condor III" but the Commando name was in use by early 1942 in company pub ...

s were also used for transport between Retalhuleu and a CIA base (code-named ''JMTide'', aka ''Happy Valley'') at Puerto Cabezas. Facilities and limited logistical assistance were provided by the governments of General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes

General José Miguel Ramón Ydígoras Fuentes (17 October 1895 – 27 October 1982) was the conservative President of Guatemala from 1958 to March 1963. He was also the main challenger to Jacobo Árbenz during the 1950 presidential election. ...

in Guatemala, and General Luis Somoza Debayle in Nicaragua, but no military personnel or equipment of those nations was directly employed in the conflict.tank destroyer

A tank destroyer, tank hunter, tank killer, or self-propelled anti-tank gun is a type of armoured fighting vehicle, armed with a direct fire artillery gun or missile launcher, designed specifically to engage and destroy enemy tanks, often wi ...

s, 122mm howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

s, other artillery and small arms plus Italian 105mm howitzers. The Cuban air force armed inventory included B-26 Invader light bombers, Hawker Sea Fury fighters and Lockheed T-33 jets, all remaining from the ''Fuerza Aérea del Ejército de Cuba'', the Cuban air force of the Batista government.

Participants

U.S. Government personnel

In April 1960, FRD (''Frente Revolucionario Democratico'' – Democratic Revolutionary Front) rebels were taken to Useppa Island, Florida, which was covertly leased by the CIA at the time. Once the rebels had arrived, they were greeted by instructors from U.S. Army special forces groups, members from the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard

The Air National Guard (ANG), also known as the Air Guard, is a federal military reserve force of the United States Air Force, as well as the air militia of each U.S. state, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the ter ...

, and members of the CIA. The rebels were trained in amphibious assault tactics, guerrilla warfare, infantry and weapons training, unit tactics and land navigation. At the head of the operation was Joaquin Sanjenis Perdomo, former police chief in Cuba, and intelligence officer Rafael De Jesus Gutierrez. The group included David Atlee Philips, Howard Hunt and David Sánchez Morales. The recruiting of Cuban exiles in Miami was organized by CIA staff officers E. Howard Hunt and Gerry Droller

Gerard "Gerry" Droller (1905? - 1992) was a German CIA officer involved in the covert 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état and the recruitment of Cuban exiles in the preparation of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961.

Biography

Gerard Droller was born ...

. Detailed planning, training and military operations were conducted by Jacob Esterline

Jacob Donald Esterline (April 26, 1920 in Lewistown, Pennsylvania – October 16, 1999) was the CIA project director for the Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Early life

Jacob was the son of John Newton Esterline (May 13, 1893 - ?) and Elisabeth Showers ( ...

, Colonel Jack Hawkins, Félix Rodríguez, Rafael De Jesus Gutierrez and Colonel Stanley W. Beerli under the direction of Richard Bissell and his deputy Tracy Barnes.

Cuban government personnel

Already, Fidel Castro was known as, and addressed as, the commander-in-chief of Cuban armed forces, with a nominal base at "Point One" in Havana. In early April 1961, his brother Raúl Castro was assigned command of forces in the east, based in Santiago de Cuba. Che Guevara commanded western forces, based in Pinar del Río. Major Juan Almeida Bosque commanded forces in the central provinces, based in Santa Clara. Raúl Curbelo Morales was head of the Cuban Air Force. Sergio del Valle Jiménez

Sergio del Valle Jiménez (15 April 1927—15 November 2007) was a high-ranking Cuban military and government official who served as army chief of staff during the 1962 Missile Crisis and headed various cabinet ministries during the 1960s, 19 ...

was Director of Headquarters Operations at Point One. Efigenio Ameijeiras was the Head of the Revolutionary National Police. Ramiro Valdés Menéndez

Ramiro Valdés Menéndez (born 28 April 1932) is a Cuban politician. He became a Government Vice President in the 2009 shake-up by Raúl Castro.

Biography

A veteran of the Cuban Revolution, Valdés fought alongside Fidel Castro at the attack on ...

was Minister of the Interior and head of G-2 (Seguridad del Estado, or state security). His deputy was Comandante Manuel Piñeiro Losada, also known as 'Barba Roja'. Captain José Ramón Fernández was head of the School of Militia Leaders (Cadets) at Matanzas

Matanzas (Cuban ) is the capital of the Cuban province of Matanzas. Known for its poets, culture, and Afro-Cuban folklore, it is located on the northern shore of the island of Cuba, on the Bay of Matanzas (Spanish ''Bahia de Matanzas''), east ...

.[Wyden (1979)][ Kellner 1989, p. 69.]

Other commanders of units during the conflict included Major Raúl Menéndez Tomassevich, Major Filiberto Olivera Moya, Major René de los Santos, Major Augusto Martínez Sánchez, Major Félix Duque, Major Pedro Miret, Major Flavio Bravo, Major Antonio Lussón

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

, Captain Orlando Pupo Peña, Captain Victor Dreke, Captain Emilio Aragonés, Captain Ángel Fernández Vila, Arnaldo Ochoa

Arnaldo Tomás Ochoa Sánchez (1930 – July 13, 1989) was a Cuban general who was executed by the government of Fidel Castro after being found guilty of a variety of crimes including drug smuggling and treason. Allegations from a former Castro ...

, and Orlando Rodríguez Puerta.[Dreke (2002)] Soviet-trained Spanish advisors were brought to Cuba from Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

countries. These advisors had held high staff positions in the Soviet armies during World War II and became known as "Hispano-Soviets," having long resided in the Soviet Union. The most senior of these was the Spanish communist veterans of the Spanish Civil War, Francisco Ciutat de Miguel, Enrique Líster and Cuban-born Alberto Bayo. Ciutat de Miguel (Cuban alias: Ángel Martínez Riosola, commonly referred to as "Angelito"), was an advisor to forces in the central provinces. The role of other Soviet agents at the time is uncertain, but some of them acquired greater fame later. For example, two KGB colonels, Vadim Kochergin and Victor Simanov were first sighted in Cuba in about September 1959.

Prior warnings of invasion

The Cuban security apparatus knew the invasion was coming, in part due to indiscreet talk by members of the brigade, some of which was heard in Miami and repeated in U.S. and foreign newspaper reports. Nevertheless, days before the invasion, multiple acts of sabotage were carried out, such as the El Encanto fire

The El Encanto fire was a terrorist arson attack that destroyed a department store in central Havana on 13 April 1961.

History

El Encanto was the largest department store in Cuba, with five retail storeys, originally built in 1888, and situated on ...

, an arson attack in a department store in Havana on 13 April that killed one shop worker.[ The Cuban government also had been warned by senior KGB agents Osvaldo Sánchez Cabrera and 'Aragon', who died violently before and after the invasion, respectively. The general Cuban population was not well informed of intelligence matters, which the US sought to exploit with propaganda through CIA-funded Radio Swan. As of May 1960, almost all means of public communication were under public ownership.

On 29 April 2000, a '' Washington Post'' article, "Soviets Knew Date of Cuba Attack", reported that the CIA had information indicating that the Soviet Union knew the invasion was going to take place and did not inform Kennedy. On 13 April 1961, Radio Moscow broadcast an English-language newscast, predicting the invasion "in a plot hatched by the CIA" using paid "criminals" within a week. The invasion took place four days later.

David Ormsby-Gore, the British ambassador to the U.S., stated that British intelligence analysis made available to the CIA indicated that the Cuban people were overwhelmingly behind Castro and that there was no likelihood of mass defections or insurrections.

]

Prelude to invasion

Acquisition of aircraft

From June to September 1960, the most time-consuming task was the acquisition of the aircraft to be used in the invasion. The anti-Castro effort depended on the success of these aircraft. Although models such as the Curtiss C-46 Commando

The Curtiss C-46 Commando is a twin-engine transport aircraft derived from the Curtiss CW-20 pressurised high-altitude airliner design. Early press reports used the name "Condor III" but the Commando name was in use by early 1942 in company pub ...

and Douglas C-54 Skymaster were to be used for airdrops and bomb drops as well as for infiltration and exfiltration, they were looking for an aircraft that could perform tactical strikes. The two models that were going to be decided on were the Navy's Douglas AD-5 Skyraider or the Air Force's light bomber, the Douglas B-26 Invader. The AD-5 was readily available and ready for the Navy to train pilots, and in a meeting among a special group in the office of the Deputy Director of the CIA

The Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (DD/CIA) is a statutory office () and the second-highest official of the Central Intelligence Agency. The DD/CIA assists the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (D/CIA) and is author ...

, the AD-5 was approved and decided upon. After a cost-benefit analysis, word was sent that the AD-5 plan would be abandoned and the B-26 would take its place.

Fleet sets sail

Under cover of darkness, the invasion fleet set sail from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua and headed towards the Bay of Pigs on the night of 14 April. After on-loading the attack planes in Norfolk Naval Base and taking on prodigious quantities of food and supplies sufficient for the seven weeks at-sea to come, the crew knew from the hasty camouflage of the ship's and aircraft identifying numbers that a secret mission was on hand. Combatants were supplied with forged Cuban local currency, in the form of 20 Peso bills, identifiable by the serial numbers F69 and F70. The aircraft carrier group of the had been at sea for nearly a month before the invasion; its crew was well aware of the impending battle. En route, ''Essex'' had made a night time stop at a Navy arms depot in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, to load tactical nuclear weapons to be held ready during the cruise. The afternoon of the invasion, one accompanying destroyer rendezvoused with ''Essex'' to have a gun mount repaired and put back into action; the ship displayed numerous shell casings on deck from its shore bombardment actions. On 16 April ''Essex'' was at general quarters for most of a day; Soviet MiG-15s made feints and close range fly overs that night.

Air attacks on airfields

During the night of 14/15 April, a diversionary landing was planned near Baracoa, Oriente Province

Oriente (, "East") was the easternmost province of Cuba until 1976. The term "Oriente" is still used to refer to the eastern part of the country, which currently is divided into five different provinces. Fidel and Raúl Castro were born in a sm ...

, by about 164 Cuban exiles commanded by Higinio 'Nino' Diaz. Their mother ship, named ''La Playa'' or ''Santa Ana'', had sailed from Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

under a Costa Rican ensign. Several U.S. Navy destroyers were stationed offshore near Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay ( es, Bahía de Guantánamo) is a bay in Guantánamo Province at the southeastern end of Cuba. It is the largest harbor on the south side of the island and it is surrounded by steep hills which create an enclave that is cut off ...

to give the appearance of an impending invasion fleet. The reconnaissance boats turned back to the ship after their crews detected activities by Cuban militia forces along the coastline.[Triay (2001), pp. 83–113] As a result of those activities, at daybreak, a reconnaissance sortie over the Baracoa area was launched from Santiago de Cuba by an FAR Lockheed T-33, piloted by Lt. Orestes Acosta and it crashed fatally into the sea. On 17 April, his name was falsely quoted as a defector among the disinformation circulating in Miami.Jacobo Arbenz

Jacobo is both a surname and a given name of Spanish origin. Based on the name Jacob. Notable people with the name include:

Surname:

*Alfredo Jacobo (born 1982), Olympic breaststroke swimmer from Mexico

*Cesar Chavez Jacobo, Dominican professional ...

in Guatemala in 1954. The point was to create confusion in Havana and have it be a distraction to Castro if they could "break all the windows in town."false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

markings of the FAR. Each came armed with bombs, rockets, and machine guns. They had flown from Puerto Cabezas in Nicaragua and were crewed by exiled Cuban pilots and navigators of the self-styled ''Fuerza Aérea de Liberación'' (FAL). The purpose of the action (code-named ''Operation Puma'') was reportedly to destroy most or all of the armed aircraft of the FAR in preparation for the main invasion. At Santiago, the two attackers destroyed a C-47

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (Royal Air Force, RAF, Royal Australian Air Force, RAAF, Royal Canadian Air Force, RCAF, Royal New Zealand Air Force, RNZAF, and South African Air Force, SAAF designation) is a airlift, military transport ai ...

transport, a PBY Catalina flying boat, two B-26s and a civilian Douglas DC-3

The Douglas DC-3 is a propeller-driven airliner

manufactured by Douglas Aircraft Company, which had a lasting effect on the airline industry in the 1930s to 1940s and World War II.

It was developed as a larger, improved 14-bed sleeper version ...

plus various other civilian aircraft. At San Antonio, the three attackers destroyed three FAR B-26s, one Hawker Sea Fury and one T-33, and one attacker diverted to Grand Cayman because of low fuel. Aircraft that diverted to the Caymans were seized by the United Kingdom since they were suspicious that the Cayman Islands might be perceived as a launch site for the invasion.Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. It was a successful high-altitude fighter and it also served as the foremost American fighter-bombe ...

s. One of those attackers was damaged by anti-aircraft fire and ditched about north of Cuba,[Shono (2012) p]

67

/ref> with the loss of its crew Daniel Fernández Mon and Gaston Pérez. Its companion B-26, also damaged, continued north and landed at Boca Chica Field, Florida. The crew, José Crespo and Lorenzo Pérez-Lorenzo, were granted political asylum, and made their way back to Nicaragua the next day via Miami and the daily CIA C-54 flight from Opa-Iocka Airport to Puerto Cabezas Airport. Their B-26, purposely numbered 933, the same as at least two other B-26s that day for disinformation reasons, was held until late on 17 April.[Ferrer (1975)]

Deception flight

About 90 minutes after the eight B-26s had taken off from Puerto Cabezas to attack Cuban airfields, another B-26 departed on a deception flight that took it close to Cuba but headed north towards Florida. Like the bomber groups, it carried false FAR markings and the same number 933 as painted on at least two of the others. Before departure, the cowling from one of the aircraft's two engines was removed by CIA personnel, fired upon, then re-installed to give the false appearance that the aircraft had taken ground fire at some point during its flight. At a safe distance north of Cuba, the pilot feathered the engine with the pre-installed bullet holes in the cowling, radioed a mayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiza ...

call, and requested immediate permission to land at Miami International airport. He landed and taxied to the military area of the airport near an Air Force C-47 and was met by several government cars. The pilot was Mario Zúñiga, formerly of the FAEC (Cuban Air Force under Batista), and after landing, he masqueraded as 'Juan Garcia' and publicly claimed that three colleagues had also defected from the FAR. The next day he was granted political asylum, and that night he returned to Puerto Cabezas via Opa-Locka.[ This deception operation was successful at the time in convincing much of the world media that the attacks on the FAR bases were the work of an internal anti-Communist faction and did not involve outside actors.

]

Reactions

At 10:30 am on 15 April at the United Nations, Cuban Foreign Minister Raúl Roa

Raul, Raúl and Raül are the Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish, Galician, Asturian, Basque, Aragonese, and Catalan forms of the Anglo-Germanic given name Ralph or Rudolph. They are cognates of the French Raoul.

Raul, Raúl or Raül may re ...

accused the U.S. of aggressive air attacks against Cuba and that afternoon formally tabled a motion to the Political (First) Committee of the UN General Assembly. Only days earlier, the CIA had unsuccessfully attempted to entice Raúl Roa into defecting.United States Ambassador to the United Nations

The United States ambassador to the United Nations is the leader of the U.S. delegation, the U.S. Mission to the United Nations. The position is formally known as the permanent representative of the United States of America to the United Nations ...

Adlai Stevenson Adlai Stevenson may refer to:

* Adlai Stevenson I (1835–1914), U.S. Vice President (1893–1897) and Congressman (1879–1881)

* Adlai Stevenson II (1900–1965), Governor of Illinois (1949–1953), U.S. presidential candida ...

stated that U.S. armed forces would not "under any conditions" intervene in Cuba and that the U.S. would do everything in its power to ensure that no U.S. citizens would participate in actions against Cuba. He also stated that Cuban defectors had carried out the attacks that day, and he presented a UPI wire photo of Zúñiga's B-26 in Cuban markings at Miami airport.[ Stevenson was later embarrassed to realize that the CIA had lied to him.][

President Kennedy supported the statement made by Stevenson: "I have emphasized before that this was a struggle of Cuban patriots against a Cuban dictator. While we could not be expected to hide our sympathies, we made it repeatedly clear that the armed forces of this country would not intervene in any way".

On 15 April, the Cuban national police, led by Efigenio Ameijeiras, started the process of arresting thousands of suspected anti-revolutionary individuals and detaining them in provisional locations such as the Karl Marx Theatre, the moat of Fortaleza de la Cabana, and the Principe Castle, all in Havana, and the baseball park in Matanzas.][ In total, between 20,000 and 100,000 people would be arrested.

]

Phony war

On the night of 15/16 April, the Nino Diaz group failed in a second attempted diversionary landing at a different location near Baracoa.[ On 16 April, Merardo Leon, Jose Leon, and 14 others staged an armed uprising at Las Delicias Estate in Las Villas, with only four surviving.][MacPhall, Doug & Acree, Chuck (2003)]

"Bay of Pigs: The Men and Aircraft of the Cuban Revolutionary Air Force"

.

No additional airstrikes against Cuban airfields and aircraft were specifically planned before 17 April, because B-26 pilots' exaggerated claims gave the CIA false confidence in the success of 15 April attacks, until U-2 reconnaissance photos taken on 16 April showed otherwise. Late on 16 April, President Kennedy ordered the cancellation of further airfield strikes planned for dawn on 17 April, to attempt plausible deniability of direct U.S. involvement.

Invasion

Invasion day (17 April)

During the night of 16/17 April, a mock diversionary landing was organized by CIA operatives near Bahía Honda, Pinar del Río Province. A flotilla containing equipment that broadcast sounds and other effects of a shipborne invasion landing provided the source of Cuban reports that briefly lured Fidel Castro away from the Bay of Pigs battlefront area.

During the night of 16/17 April, a mock diversionary landing was organized by CIA operatives near Bahía Honda, Pinar del Río Province. A flotilla containing equipment that broadcast sounds and other effects of a shipborne invasion landing provided the source of Cuban reports that briefly lured Fidel Castro away from the Bay of Pigs battlefront area.[

At about 00:00 on 17 April 1961, the two LCIs ''Blagar'' and ''Barbara J'', each with a CIA 'operations officer' and an Underwater Demolition Team of five frogmen, entered the Bay of Pigs ''(Bahía de Cochinos)'' on the southern coast of Cuba. They headed a force of four transport ships (''Houston'', ''Río Escondido'', ''Caribe'' and ''Atlántico'') carrying about 1,400 Cuban exile ground troops of Brigade 2506, plus the brigade's M41 tanks and other vehicles in the landing craft. At about 01:00, ''Blagar'', as the battlefield command ship, directed the principal landing at Playa Girón (code-named ''Blue Beach''), led by the frogmen in rubber boats followed by troops from ''Caribe'' in small aluminum boats, then the LCVPs and LCUs with the M41 tanks. ''Barbara J'', leading ''Houston'', similarly landed troops 35 km further northwest at Playa Larga (code-named ''Red Beach''), using small fiberglass boats. The unloading of troops at night was delayed, because of engine failures and boats damaged by unseen coral reefs; the CIA had originally believed that the coral reef was seaweed. As the frogmen came in, they were shocked to discover that the Red Beach was lit with floodlights, which led to the location of the landing being hastily changed. As the frogmen landed, a firefight broke out when a jeep carrying Cuban militia happened by. The few militias in the area succeeded in warning Cuban armed forces via radio soon after the first landing, before the invaders overcame their token resistance.][ Castro was awakened at about 3:15 am to be informed of the landings, which led him to put all militia units in the area on the highest state of alert and to order airstrikes. The Cuban regime planned to strike the ''brigadistas'' at Playa Larga first as they were inland before turning on the ''brigadistas'' at Girón at sea. ''El Comandante'' departed personally to lead his forces into battle against the ''brigadistas''.

At daybreak around 6:30 am, three FAR Sea Furies, one B-26 bomber and two T-33s started attacking those CEF ships still unloading troops. At about 6:50, south of Playa Larga, ''Houston'' was damaged by several bombs and rockets from a Sea Fury and a T-33, and about two hours later Captain Luis Morse intentionally beached it on the western side of the bay. About 270 troops had been unloaded, but about 180 survivors who struggled ashore were incapable of taking part in further action because of the loss of most of their weapons and equipment. The loss of ''Houston'' was a great blow to the ''brigadistas'' as that ship was carrying much of the medical supplies, which meant that wounded ''brigadistas'' had to make do with inadequate medical care. At about 7:00, two FAL B-26s attacked and sank the Cuban Navy Patrol Escort ship ''El Baire'' at Nueva Gerona on the Isle of Pines.][ They then proceeded to Girón to join two other B-26s to attack Cuban ground troops and provide distraction air cover for the paratroop C-46s and the CEF ships under air attack. The M41 tanks had all landed by 7:30 am at Blue Beach and all of the troops by 8:30 am. Neither San Román at Blue Beach nor Erneido Oliva at Red Beach could communicate as all of the radios had been soaked in the water during the landings.

] At about 7:30, five C-46 and one C-54 transport aircraft dropped 177 paratroops from the parachute battalion in an action code-named ''Operation Falcon''.

At about 7:30, five C-46 and one C-54 transport aircraft dropped 177 paratroops from the parachute battalion in an action code-named ''Operation Falcon''.[Cooper, Tom (2003]

"Clandestine US Operations: Cuba, 1961, Bay of Pigs"

About 30 men, plus heavy equipment, were dropped south of the Central Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

sugar mill on the road to Palpite and Playa Larga, but the equipment was lost in the swamps, and the troops failed to block the road. Other troops were dropped at San Blas, at Jocuma between Covadonga and San Blas, and at Horquitas between Yaguaramas and San Blas. Those positions to block the roads were maintained for two days, reinforced by ground troops from Playa Girón and tanks. The paratroopers had landed amid a collection of militia, but their training allowed them to hold their own against the ill-trained militiamen. However, the dispersal of the paratroopers as they landed meant they were unable to take the road from the sugar mill down to Playa Larga, which allowed the government to continue to send troops down to resist the invasion.

At about 8:30, a FAR Sea Fury piloted by Carlos Ulloa Arauz crashed in the bay after encountering a FAL C-46 returning south after dropping paratroops. By 9:00, Cuban troops and militia from outside the area had started arriving at the sugar mill, Covadonga and Yaguaramas. Throughout the day they were reinforced by more troops, heavy armour and T-34 tanks typically carried on flat-bed trucks. At about 9:30, FAR Sea Furies and T-33s fired rockets at ''Rio Escondido'', which then 'blew up' and sank about south of Girón.[ ''Rio Escondido'' was loaded with aviation fuel, and as the ship started to burn, the captain gave the order to abandon ship with the ship being destroyed in three explosions shortly afterward . ''Rio Escondido'' carried fuel along with enough ammunition, food, and medical supplies to last ten days and the radio that allowed the brigade to communicate with the FAL. The loss of the communications ship ''Rio Escondido'' meant that San Román was only able to issue orders to the forces at Blue Beach, and he had no idea of what was happening at Red Beach or with the paratroopers. A messenger from Red Beach arrived at about 10:00 am asking San Román to send tank and infantry to block the road from the sugar mill, a request that he agreed to. It was not expected that government forces would be counter-attacking from this direction.

At about 11:00, Castro issued a statement over Cuba's nationwide network saying that the invaders, members of the exiled Cuban revolutionary front, have come to destroy the revolution and take away the dignity and rights of men. At about 11:00, a FAR T-33 attacked and shot down a FAL B-26 (serial number 935) piloted by Matias Farias, who then survived a crash landing on the Girón airfield, his navigator Eduardo González already killed by gunfire. His companion B-26 suffered damage and diverted to Grand Cayman Island; pilot Mario Zúñiga (the 'defector') and navigator Oscar Vega returned to Puerto Cabezas via CIA C-54 on 18 April. By about 11:00, the two remaining freighters ''Caribe'' and ''Atlántico'', and the LCIs and LCUs, started retreating south to international waters, but still pursued by FAR aircraft. At about noon, a FAR B-26 exploded from heavy anti-aircraft fire from ''Blagar'', and pilot Luis Silva Tablada (on his second sortie) and his crew of three were lost.][ At 2:30 pm a group of militiamen from the 339th Battalion set up a position, which came under attack from the ''brigadista'' M41 tanks, which inflicted heavy losses on the defenders. This action is remembered in Cuba as the "Slaughter of the Lost Battalion" as most of the militiamen perished.

Three FAL B-26s were shot down by FAR T-33s, with the loss of pilots Raúl Vianello, José Crespo, Osvaldo Piedra and navigators Lorenzo Pérez-Lorenzo and José Fernández. Vianello's navigator Demetrio Pérez bailed out and was picked up by USS ''Murray''. Pilot Crispín García Fernández and navigator Juan González Romero, in B-26 serial 940, diverted to Boca Chica, but late that night they attempted to fly back to Puerto Cabezas in B-26 serial 933 that Crespo had flown to Boca Chica on 15 April. In October 1961, the remains of the B-26 and its two crew were found in the dense jungle in Nicaragua.][ One FAL B-26 diverted to Grand Cayman with engine failure. By 4:00, Castro had arrived at the Central Australia sugar mill, joining José Ramón Fernández whom he had appointed as battlefield commander before dawn that day.

At about 5:00, a night air strike by three FAL B-26s on San Antonio de Los Baños airfield failed, reportedly because of incompetence and bad weather. Two other B-26s had aborted the mission after take-off.]

Invasion day plus one (D+1) 18 April

During the night of 17–18 April, the force at Red Beach came under repeated counter-attacks from the Cuban Army and militia. As casualties mounted and ammunition was used up, the ''brigadistas'' steadily gave way. Airdrops from four C-54s and 2 C-46s had only limited success in landing more ammunition. Both the ''Blagar'' and ''Barbara J'' returned at midnight to land more ammunition, which proved insufficient for the ''brigadistas''. Following desperate appeals for help from Oliva, San Román ordered all of his M41 tanks to assist in the defense. During the night fighting, a tank battle broke out when the ''brigadista'' M41 tanks clashed with the T-34 tanks of the Cuban Army. This sharp action forced back the ''brigadistas.'' At 10:00 pm, the Cuban Army opened fire with its 76.2mm and 122mm artillery guns on the ''brigadista'' forces at Playa Larga, which was followed by an attack by T-34 tanks at about midnight. The 2,000 artillery rounds fired by the Cuban Army had mostly missed the ''brigadista'' defense positions, and the T-34 tanks rode into an ambush when they came under fire from the ''brigadista'' M41 tanks and mortar fire, and a number of T-34 tanks were destroyed or knocked out. At 1:00 am, Cuban Army infantrymen and militiamen started an offensive. Despite heavy losses on the part of the Cuban forces, the shortage of ammunition forced the ''brigadistas'' back and the T-34 tanks continued to force their way past the wreckage of the battlefield to press on the assault. The Cuban forces in the assault numbered about 2,100 men, consisting of about 300 FAR soldiers, 1,600 militiamen and 200 local policemen supported by at least 20 T-34 tanks who were faced by 370 ''brigadistas''. By 5:00 am, Oliva started to order his men to retreat as he had almost no ammunition or mortar rounds left. By about 10:30 am, Cuban troops and militia, supported by the T-34 tanks and 122mm artillery, took Playa Larga after Brigade forces had fled towards Girón in the early hours. During the day, Brigade forces retreated to San Blas along the two roads from Covadonga and Yaguaramas. By then, both Castro and Fernández had relocated to that battlefront area.

As the men from Red Beach arrived at Girón, San Román and Oliva met to discuss the situation. With ammunition running low, Oliva suggested that the brigade retreat into the Escambray Mountains to wage guerilla warfare, but San Román decided to hold the beachhead. At about 11:00 am, the Cuban Army began an offensive to take San Blas. San Román ordered all of the paratroopers back in order to hold San Blas, and they halted the offensive. During the afternoon, Castro kept the ''brigadistas'' under steady air attack and artillery fire but did not order any new major attacks.

At 2:00 pm, President Kennedy received a telegram from Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow, stating the Russians would not allow the U.S. to enter Cuba and implied swift nuclear retribution to the United States heartland if their warnings were not heeded.

At about 5:00 pm, FAL B-26s attacked a Cuban column of 12 private buses leading trucks carrying tanks and other armor, moving southeast between Playa Larga and Punta Perdiz. The vehicles, loaded with civilians, militia, police, and soldiers, were attacked with bombs, napalm, and rockets, suffering heavy casualties. The six attacking FAL B-26s were piloted by two CIA contract pilots plus four pilots and six navigators from the FAL.[ The column later re-formed and advanced to Punta Perdiz, about 11 km northwest of Girón.

]

Invasion day plus two (D+2) 19 April

During the night of 18 April, a FAL C-46 delivered arms and equipment to the Girón airstrip occupied by brigade ground forces and took off before daybreak on 19 April.

During the night of 18 April, a FAL C-46 delivered arms and equipment to the Girón airstrip occupied by brigade ground forces and took off before daybreak on 19 April.[FRUS X]

document 110

The C-46 also evacuated Matias Farias, the pilot of B-26 serial '935' (code-named ''Chico Two'') that had been shot down and crash-landed at Girón on 17 April.[ The crews of the ''Barbara J'' and ''Blagar'' had done their best to land what ammunition they had left onto the beachhead, but without air support the captains of both ships reported that it was too dangerous to be operating off the Cuban coast by day.

The final air attack mission (code-named ''Mad Dog Flight'') comprised five B-26s, four of which were manned by American CIA contract aircrews and volunteer pilots from the Alabama Air Guard. One FAR Sea Fury (piloted by Douglas Rudd) and two FAR T-33s (piloted by Rafael del Pino and Alvaro Prendes) shot down two of these B-26s, killing four American airmen.][ Combat air patrols were flown by Douglas A4D-2N Skyhawk jets of VA-34 squadron operating from USS ''Essex'', with nationality and other markings removed. Sorties were flown to reassure brigade soldiers and pilots and to intimidate Cuban government forces without directly engaging in combat.][ At 10 am, a tank battle broke out, with the ''brigadista'' holding their line until about 2 pm, which led Olvia to order a retreat into Girón. After the last air attacks, San Román ordered his paratroopers and the men of the 3rd Battalion to launch a surprise attack, which was initially successful but soon failed. With the ''brigadistas'' in disorganized retreat, the Cuban Army and militiamen started to advance rapidly, taking San Blas only to be stopped outside of Girón at about 11 am. Later that afternoon, San Román heard the rumbling of the advancing T-34s and reported that with no more mortar rounds and bazooka rounds, he could not stop the tanks and ordered his men to fall back to the beach. Oliva arrived afterward to find that the ''brigadistas'' were all heading out to the beach or retreating into the jungle or swamps. Without direct air support, and short of ammunition, Brigade 2506 ground forces retreated to the beaches in the face of the onslaught from Cuban government artillery, tanks, and infantry.][

]

Invasion day plus three (D+3) 20 April