Balkan War (1912–13) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the

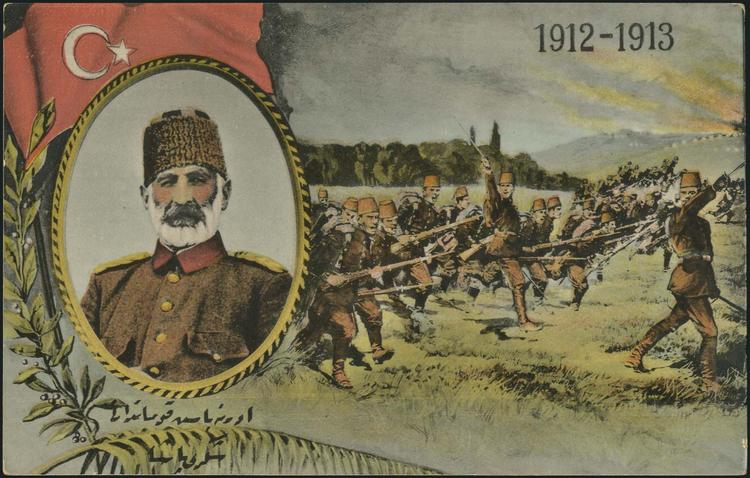

Süleyman Uslu As a result of the war, the League captured and partitioned almost all of the Ottoman Empire's remaining territories in Europe. Ensuing events also led to the creation of an

When the war broke out, the Ottoman

When the war broke out, the Ottoman

Greece, whose population was then 2,666,000,Erickson (2003), p. 70 was considered the weakest of the three main allies since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered a defeat against the Ottomans 16 years earlier, in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. A British consular dispatch from 1910 expressed the common perception of the Greek army's abilities: "if there is war we shall probably see that the only thing Greek officers can do besides talking is to run away".Fotakis (2005), p. 42 However, Greece was the only Balkan country to possess a substantial navy, which was vital to the League to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. That was readily appreciated by the Serbs and the Bulgarians and was the chief factor in initiating the process of Greece's inclusion in the League. As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry into the League, "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between

Greece, whose population was then 2,666,000,Erickson (2003), p. 70 was considered the weakest of the three main allies since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered a defeat against the Ottomans 16 years earlier, in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. A British consular dispatch from 1910 expressed the common perception of the Greek army's abilities: "if there is war we shall probably see that the only thing Greek officers can do besides talking is to run away".Fotakis (2005), p. 42 However, Greece was the only Balkan country to possess a substantial navy, which was vital to the League to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. That was readily appreciated by the Serbs and the Bulgarians and was the chief factor in initiating the process of Greece's inclusion in the League. As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry into the League, "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between

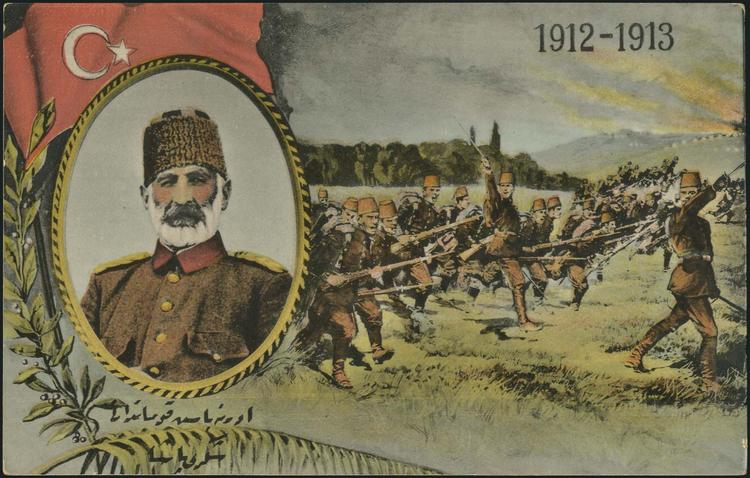

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by a number of factors, such as domestic strife, caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counterrevolutionary coup several months later. That resulted in different groups competing for influence within the military. A German mission had tried to reorganize the army, but its recommendations had not been fully implemented. The Ottoman army was caught in the middle of reform and reorganisation. Also, several of the army's best battalions had been transferred to

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by a number of factors, such as domestic strife, caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counterrevolutionary coup several months later. That resulted in different groups competing for influence within the military. A German mission had tried to reorganize the army, but its recommendations had not been fully implemented. The Ottoman army was caught in the middle of reform and reorganisation. Also, several of the army's best battalions had been transferred to

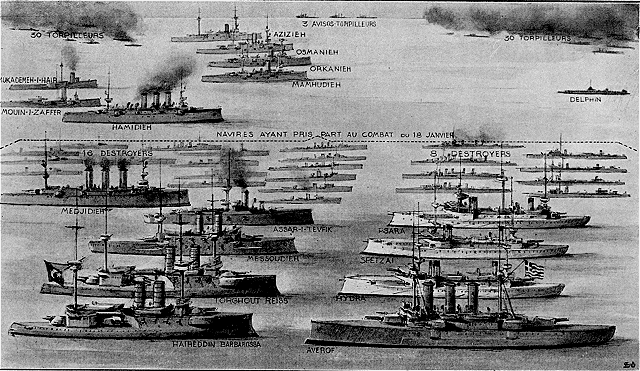

The Ottoman fleet had performed abysmally in the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, forcing the Ottoman government to begin a drastic overhaul. Older ships were retired and newer ones acquired, chiefly from France and Germany. In addition, in 1908, the Ottomans called in a British naval mission to update their training and doctrine. The British mission, headed by Admiral Sir

The Ottoman fleet had performed abysmally in the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, forcing the Ottoman government to begin a drastic overhaul. Older ships were retired and newer ones acquired, chiefly from France and Germany. In addition, in 1908, the Ottomans called in a British naval mission to update their training and doctrine. The British mission, headed by Admiral Sir

Montenegro started the First Balkan War by declaring war against the Ottomans on . The western part of the Balkans, including Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, was less important to the resolution of the war and the survival of the Ottoman Empire than the Thracian theatre, where the Bulgarians fought major battles against the Ottomans. Although geography dictated Thrace would be the major battlefield in a war with the Ottoman Empire, the position of the Ottoman Army there was jeopardized by erroneous intelligence estimates of the opponents' order of battle. Unaware of the secret prewar political and military settlement over Macedonia between Bulgaria and Serbia, the Ottoman leadership assigned the bulk of its forces there. The German ambassador, Hans Baron von Wangenheim, one of the most influential people in the Ottoman capital, had reported to Berlin on 21 October that the Ottoman forces believed that the bulk of the Bulgarian army would be deployed in Macedonia with the Serbs. Then, the Ottoman headquarters, under Abdullah Pasha, expected to meet only three Bulgarian infantry divisions, accompanied by cavalry, east of Adrianople. According to historian E. J. Erickson, that assumption possibly resulted from the analysis of the objectives of the Balkan Pact, but it had deadly consequences for the Ottoman Army in Thrace, which was now required to defend the area from the bulk of the Bulgarian army against impossible odds. The misappraisal was also the reason of the catastrophic aggressive Ottoman strategy at the start of the campaign in Thrace.

Montenegro started the First Balkan War by declaring war against the Ottomans on . The western part of the Balkans, including Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, was less important to the resolution of the war and the survival of the Ottoman Empire than the Thracian theatre, where the Bulgarians fought major battles against the Ottomans. Although geography dictated Thrace would be the major battlefield in a war with the Ottoman Empire, the position of the Ottoman Army there was jeopardized by erroneous intelligence estimates of the opponents' order of battle. Unaware of the secret prewar political and military settlement over Macedonia between Bulgaria and Serbia, the Ottoman leadership assigned the bulk of its forces there. The German ambassador, Hans Baron von Wangenheim, one of the most influential people in the Ottoman capital, had reported to Berlin on 21 October that the Ottoman forces believed that the bulk of the Bulgarian army would be deployed in Macedonia with the Serbs. Then, the Ottoman headquarters, under Abdullah Pasha, expected to meet only three Bulgarian infantry divisions, accompanied by cavalry, east of Adrianople. According to historian E. J. Erickson, that assumption possibly resulted from the analysis of the objectives of the Balkan Pact, but it had deadly consequences for the Ottoman Army in Thrace, which was now required to defend the area from the bulk of the Bulgarian army against impossible odds. The misappraisal was also the reason of the catastrophic aggressive Ottoman strategy at the start of the campaign in Thrace.

In the Thracian Front, the Bulgarian army had placed 346,182 men against the Ottoman First Army, with 105,000 men in eastern Thrace and the Kircaali detachment, of 24,000 men, in western Thrace. The Bulgarian forces were divided into the First, Second and Third Bulgarian Armies of 297,002 men in the eastern part and 49,180 (33,180 regulars and 16,000 irregulars) under the 2nd Bulgarian Division (General Stilian Kovachev) in the western part. The first large-scale battle occurred against the Edirne-Kırklareli defensive line, where the Bulgarian First and Third Armies (a combined 174,254 men) defeated the Ottoman East Army (of 96,273 combatants), near Gechkenli, Seliolu and Petra. The Ottoman XV Corps urgently left the area to defend the

In the Thracian Front, the Bulgarian army had placed 346,182 men against the Ottoman First Army, with 105,000 men in eastern Thrace and the Kircaali detachment, of 24,000 men, in western Thrace. The Bulgarian forces were divided into the First, Second and Third Bulgarian Armies of 297,002 men in the eastern part and 49,180 (33,180 regulars and 16,000 irregulars) under the 2nd Bulgarian Division (General Stilian Kovachev) in the western part. The first large-scale battle occurred against the Edirne-Kırklareli defensive line, where the Bulgarian First and Third Armies (a combined 174,254 men) defeated the Ottoman East Army (of 96,273 combatants), near Gechkenli, Seliolu and Petra. The Ottoman XV Corps urgently left the area to defend the  On , the offensive against the Çatalca Line began, despite clear warnings that if the Bulgarians occupied Constantinople, Russia would attack them. The Bulgarians launched their attack along the defensive line, with 176,351 men and 462 artillery pieces against the Ottomans' 140,571 men and 316 artillery pieces, but despite Bulgarian superiority, the Ottomans succeeded in repulsing them. An armistice was agreed on between the Ottomans and Bulgaria, the latter also representing Serbia and Montenegro, and peace negotiations began in London. Greece also participated in the conference but refused to agree to a truce and continued its operations in the Epirus sector. The negotiations were interrupted on , when a Young Turk coup d'état in Constantinople, under

On , the offensive against the Çatalca Line began, despite clear warnings that if the Bulgarians occupied Constantinople, Russia would attack them. The Bulgarians launched their attack along the defensive line, with 176,351 men and 462 artillery pieces against the Ottomans' 140,571 men and 316 artillery pieces, but despite Bulgarian superiority, the Ottomans succeeded in repulsing them. An armistice was agreed on between the Ottomans and Bulgaria, the latter also representing Serbia and Montenegro, and peace negotiations began in London. Greece also participated in the conference but refused to agree to a truce and continued its operations in the Epirus sector. The negotiations were interrupted on , when a Young Turk coup d'état in Constantinople, under

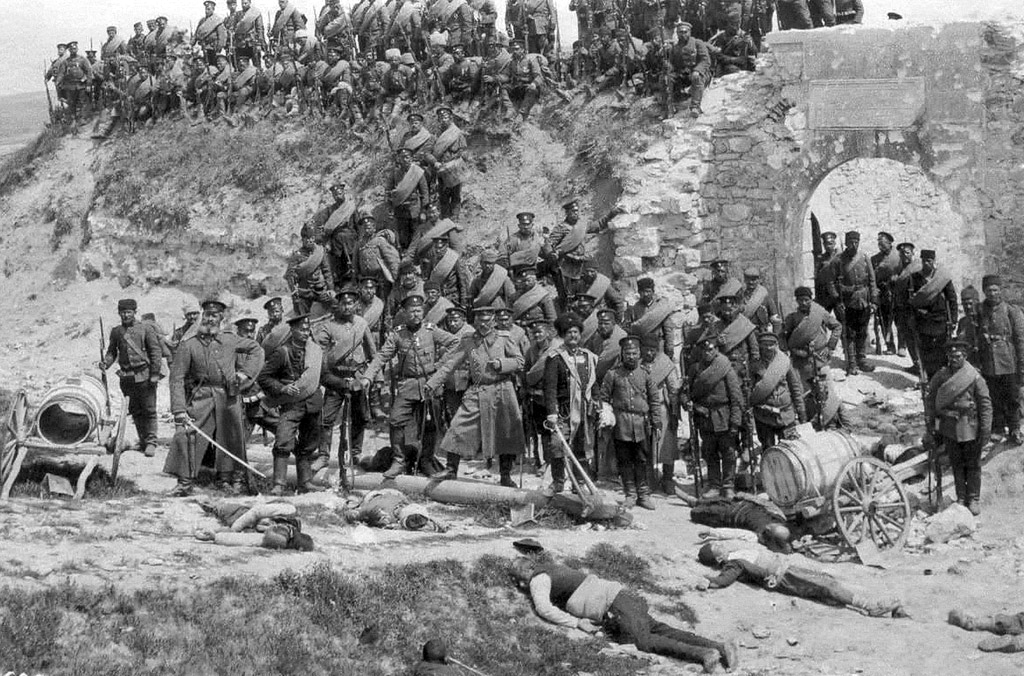

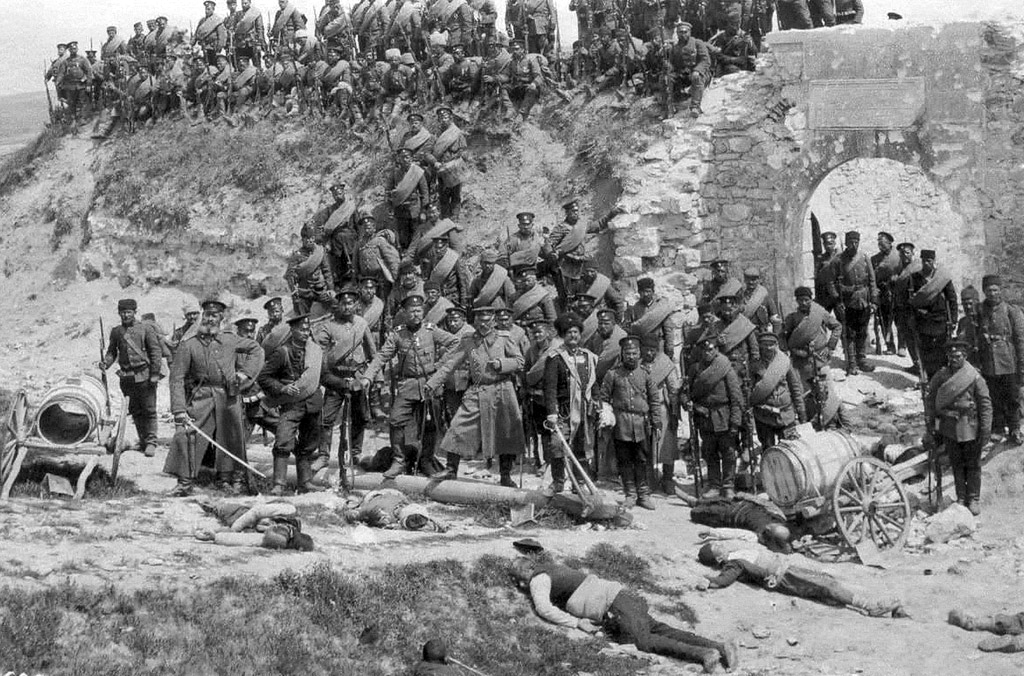

The failure of the Şarköy-Bulair operation and the deployment of the Second Serbian Army, with its much-needed heavy siege artillery, sealed Adrianople's fate. On 11 March, after a two weeks' bombardment, which destroyed many of the fortified structures around the city, the final assault started, with League forces enjoying a crushing superiority over the Ottoman garrison. The Bulgarian Second Army, with 106,425 men and two Serbian divisions with 47,275 men, conquered the city, with the Bulgarians suffering 8,093 and the Serbs 1,462 casualties. The Ottoman casualties for the entire Adrianople campaign reached 23,000 dead. The number of prisoners is less clear. The Ottoman Empire began the war with 61,250 men in the fortress.Erickson (2003), p. 281 Richard Hall noted that 60,000 men were captured. Adding to the 33,000 killed, the modern "Turkish General Staff History" notes that 28,500-man survived captivity leaving 10,000 men unaccounted for as possibly captured (including the unspecified number of wounded). Bulgarian losses for the entire Adrianople campaign amounted to 7,682. That was the last and decisive battle that was necessary for a quick end to the war even though it is speculated that the fortress would have fallen eventually because of starvation. The most important result was that the Ottoman command had lost all hope of regaining the initiative, which made any more fighting pointless.

The failure of the Şarköy-Bulair operation and the deployment of the Second Serbian Army, with its much-needed heavy siege artillery, sealed Adrianople's fate. On 11 March, after a two weeks' bombardment, which destroyed many of the fortified structures around the city, the final assault started, with League forces enjoying a crushing superiority over the Ottoman garrison. The Bulgarian Second Army, with 106,425 men and two Serbian divisions with 47,275 men, conquered the city, with the Bulgarians suffering 8,093 and the Serbs 1,462 casualties. The Ottoman casualties for the entire Adrianople campaign reached 23,000 dead. The number of prisoners is less clear. The Ottoman Empire began the war with 61,250 men in the fortress.Erickson (2003), p. 281 Richard Hall noted that 60,000 men were captured. Adding to the 33,000 killed, the modern "Turkish General Staff History" notes that 28,500-man survived captivity leaving 10,000 men unaccounted for as possibly captured (including the unspecified number of wounded). Bulgarian losses for the entire Adrianople campaign amounted to 7,682. That was the last and decisive battle that was necessary for a quick end to the war even though it is speculated that the fortress would have fallen eventually because of starvation. The most important result was that the Ottoman command had lost all hope of regaining the initiative, which made any more fighting pointless.

The battle had major and key results in Serbian-Bulgarian relations, planting the seeds of the two countries' confrontation some months later. The Bulgarian censor rigorously cut any references to Serbian participation in the operation in the telegrams of foreign correspondents. Public opinion in Sofia thus failed to realize the crucial services of Serbia in the battle. Accordingly, the Serbs claimed that their troops of the 20th Regiment were those who captured the Ottoman commander of the city and that Colonel Gavrilović was the allied commander who had accepted Shukri's official surrender of the garrison, a statement that the Bulgarians disputed. The Serbs officially protested and pointed out that although they had sent their troops to Adrianople to win for Bulgaria territory, whose acquisition had never been foreseen by their mutual treaty,Seton-Watson, pp. 210–238 the Bulgarians had never fulfilled the clause of the treaty for Bulgaria to send 100,000 men to help the Serbians on their Vardar Front. The Bulgarians answered that their staff had informed the Serbs on 23 August. The friction escalated some weeks later, when the Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support for their Adriatic claims. The Serbs angrily replied that to be a clear withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding, according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion, but the Bulgarians insisted that in their view, the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement remained active and the Serbs were still obliged to surrender the area, as had been agreed. The Serbs answered by accusing the Bulgarians of maximalism and pointed out that if they lost both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia, their participation in the common war would have been virtually for nothing. The tension soon was expressed in a series of hostile incidents between both armies on their common line of occupation across the Vardar valley. The developments essentially ended the Serbian-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable.

The battle had major and key results in Serbian-Bulgarian relations, planting the seeds of the two countries' confrontation some months later. The Bulgarian censor rigorously cut any references to Serbian participation in the operation in the telegrams of foreign correspondents. Public opinion in Sofia thus failed to realize the crucial services of Serbia in the battle. Accordingly, the Serbs claimed that their troops of the 20th Regiment were those who captured the Ottoman commander of the city and that Colonel Gavrilović was the allied commander who had accepted Shukri's official surrender of the garrison, a statement that the Bulgarians disputed. The Serbs officially protested and pointed out that although they had sent their troops to Adrianople to win for Bulgaria territory, whose acquisition had never been foreseen by their mutual treaty,Seton-Watson, pp. 210–238 the Bulgarians had never fulfilled the clause of the treaty for Bulgaria to send 100,000 men to help the Serbians on their Vardar Front. The Bulgarians answered that their staff had informed the Serbs on 23 August. The friction escalated some weeks later, when the Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support for their Adriatic claims. The Serbs angrily replied that to be a clear withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding, according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion, but the Bulgarians insisted that in their view, the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement remained active and the Serbs were still obliged to surrender the area, as had been agreed. The Serbs answered by accusing the Bulgarians of maximalism and pointed out that if they lost both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia, their participation in the common war would have been virtually for nothing. The tension soon was expressed in a series of hostile incidents between both armies on their common line of occupation across the Vardar valley. The developments essentially ended the Serbian-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable.

Ottoman intelligence had also disastrously misread Greek military intentions. In retrospect, the Ottoman staffs seemingly believed that the Greek attack would be shared equally between both major avenues of approach: Macedonia and Epirus. That made the Second Army staff evenly balance the combat strength of the seven Ottoman divisions between the Yanya Corps and VIII Corps, in Epirus and southern Macedonia, respectively. The Greek army also fielded seven divisions, but it had the initiative and so concentrated all seven against VIII Corps, leaving only a number of independent battalions of scarcely divisional strength on the Epirus front. That had fatal consequences for the Western Group by leading to the early loss of the city at the strategic centre of all three Macedonian fronts, Thessaloniki, which sealed their fate. In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, the Army of Thessaly seized the city. In the absence of secure sea lines of communications, the retention of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople corridor was essential to the overall strategic posture of the Ottomans in the Balkans. Once that was gone, the defeat of the Ottoman army became inevitable. The Bulgarians and the Serbs also played an important role in the defeat of the main Ottoman armies. Their great victories at Kirkkilise, Lüleburgaz, Kumanovo, and Monastir (Bitola) shattered the Eastern and Vardar Armies. However, the victories were not decisive by ending the war. The Ottoman field armies survived, and in Thrace, they actually grew stronger every day. Strategically, those victories were enabled partially by the weakened condition of the Ottoman armies, which had occurred by the active presence of the Greek army and navy.

With the declaration of war, the Greek Army of Thessaly, under Crown Prince Constantine, advanced to the north and overcame Ottoman opposition in the fortified mountain passes of

Ottoman intelligence had also disastrously misread Greek military intentions. In retrospect, the Ottoman staffs seemingly believed that the Greek attack would be shared equally between both major avenues of approach: Macedonia and Epirus. That made the Second Army staff evenly balance the combat strength of the seven Ottoman divisions between the Yanya Corps and VIII Corps, in Epirus and southern Macedonia, respectively. The Greek army also fielded seven divisions, but it had the initiative and so concentrated all seven against VIII Corps, leaving only a number of independent battalions of scarcely divisional strength on the Epirus front. That had fatal consequences for the Western Group by leading to the early loss of the city at the strategic centre of all three Macedonian fronts, Thessaloniki, which sealed their fate. In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, the Army of Thessaly seized the city. In the absence of secure sea lines of communications, the retention of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople corridor was essential to the overall strategic posture of the Ottomans in the Balkans. Once that was gone, the defeat of the Ottoman army became inevitable. The Bulgarians and the Serbs also played an important role in the defeat of the main Ottoman armies. Their great victories at Kirkkilise, Lüleburgaz, Kumanovo, and Monastir (Bitola) shattered the Eastern and Vardar Armies. However, the victories were not decisive by ending the war. The Ottoman field armies survived, and in Thrace, they actually grew stronger every day. Strategically, those victories were enabled partially by the weakened condition of the Ottoman armies, which had occurred by the active presence of the Greek army and navy.

With the declaration of war, the Greek Army of Thessaly, under Crown Prince Constantine, advanced to the north and overcame Ottoman opposition in the fortified mountain passes of

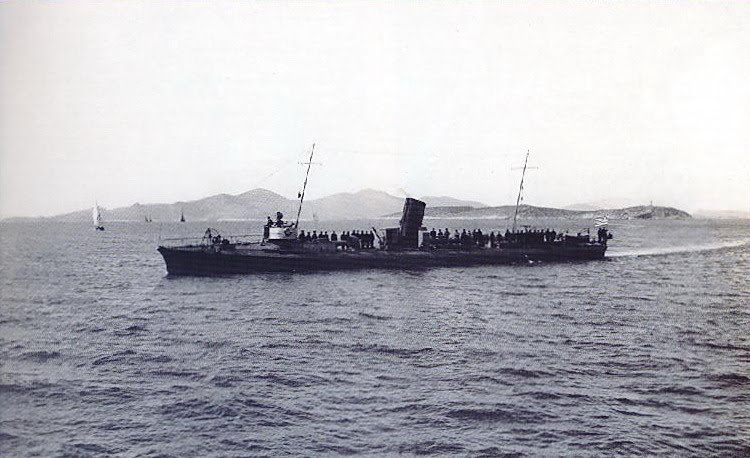

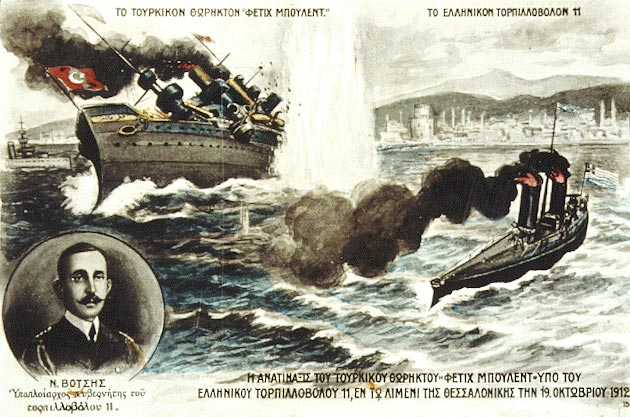

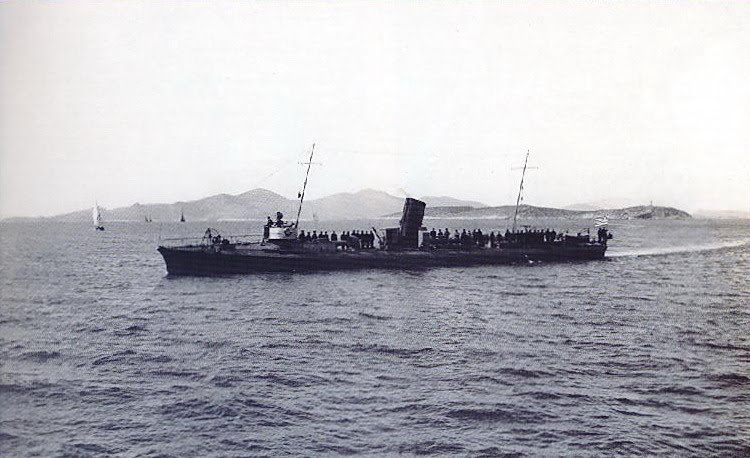

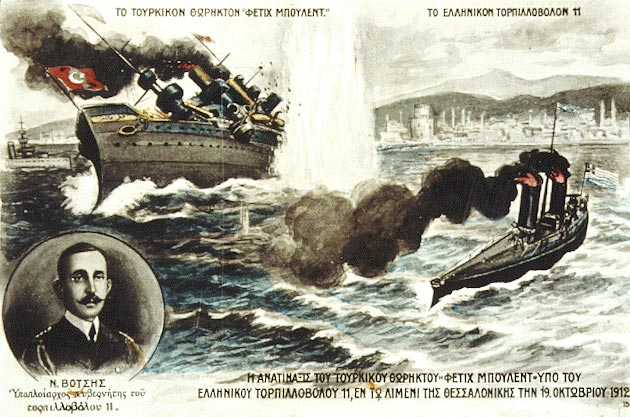

On the outbreak of hostilities on 18 October, the Greek fleet, placed under the newly promoted Rear Admiral

On the outbreak of hostilities on 18 October, the Greek fleet, placed under the newly promoted Rear Admiral  At the same time, with the aid of numerous merchant ships converted to

At the same time, with the aid of numerous merchant ships converted to

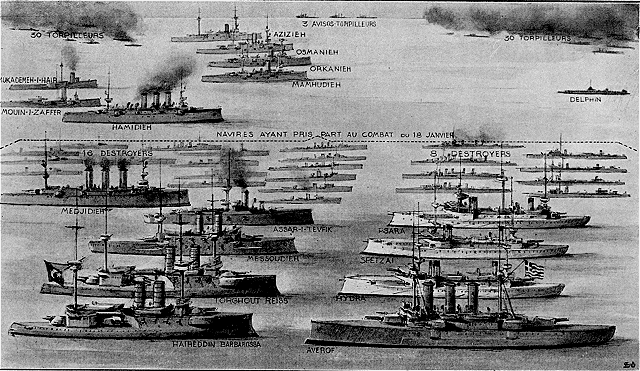

The main Ottoman fleet remained inside the Dardanelles for the early part of the war, and the Greek destroyers continuously patrolled the straits' exit to report on a possible sortie. Kountouriotis suggested

The main Ottoman fleet remained inside the Dardanelles for the early part of the war, and the Greek destroyers continuously patrolled the straits' exit to report on a possible sortie. Kountouriotis suggested  In preparation for the next attempt to break the Greek blockade, the Ottoman Admiralty decided to create a diversion by sending the light cruiser ''Hamidiye'', captained by Rauf Bey, to raid Greek merchant shipping in the Aegean. It was hoped that the ''Georgios Averof'', the only major Greek unit fast enough to catch the ''Hamidiye'', would be drawn into pursuit and leave the remainder of the Greek fleet weakened.Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 26 In the event, ''Hamidiye'' slipped through the Greek patrols on the night of 14–15 January and bombarded the harbor of the Greek island of

In preparation for the next attempt to break the Greek blockade, the Ottoman Admiralty decided to create a diversion by sending the light cruiser ''Hamidiye'', captained by Rauf Bey, to raid Greek merchant shipping in the Aegean. It was hoped that the ''Georgios Averof'', the only major Greek unit fast enough to catch the ''Hamidiye'', would be drawn into pursuit and leave the remainder of the Greek fleet weakened.Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 26 In the event, ''Hamidiye'' slipped through the Greek patrols on the night of 14–15 January and bombarded the harbor of the Greek island of

The Serbian forces operated against the major part of Ottoman Western Army, which was in Novi Pazar, Kosovo and northern and eastern Macedonia. Strategically, the Serbian forces were divided into four independent armies and groups: the Javor brigade and the Ibar Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Novi Pazar; the Third Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Kosovo; the First Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in northern Macedonia; and the Second Army, which operated from Bulgaria against Ottoman forces in eastern Macedonia. The decisive battle was expected to be fought in northern Macedonia, in the plains of Ovče Pole, where the Ottoman Vardar Army's main forces were expected to concentrate.

The plan of the Serbian Supreme Command had three Serbian armies encircle and destroy the Vardar Army in that area, with the First Army advancing from the north (along the line of Vranje-Kumanovo-Ovče Pole), the Second Army advancing from the east (along the line of Kriva Palanka-Kratovo-Ovče Pole) and the Third Army advancing from the northwest (along the line of Priština-Skopje-Ovče Pole). The main role was given to the First Army. The Second Army was expected to cut off the Vardar Army's retreat and, if necessary, to attack its rear and right flank. The Third Army was to take Kosovo and, if necessary, to assist the First Army by attacking the Vardar Army's left flank and rear. The Ibar Army and the Javor brigade had minor roles in the plan and were expected to secure the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and to replace the Third Army in Kosovo after it had advanced south.

The Serbian forces operated against the major part of Ottoman Western Army, which was in Novi Pazar, Kosovo and northern and eastern Macedonia. Strategically, the Serbian forces were divided into four independent armies and groups: the Javor brigade and the Ibar Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Novi Pazar; the Third Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Kosovo; the First Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in northern Macedonia; and the Second Army, which operated from Bulgaria against Ottoman forces in eastern Macedonia. The decisive battle was expected to be fought in northern Macedonia, in the plains of Ovče Pole, where the Ottoman Vardar Army's main forces were expected to concentrate.

The plan of the Serbian Supreme Command had three Serbian armies encircle and destroy the Vardar Army in that area, with the First Army advancing from the north (along the line of Vranje-Kumanovo-Ovče Pole), the Second Army advancing from the east (along the line of Kriva Palanka-Kratovo-Ovče Pole) and the Third Army advancing from the northwest (along the line of Priština-Skopje-Ovče Pole). The main role was given to the First Army. The Second Army was expected to cut off the Vardar Army's retreat and, if necessary, to attack its rear and right flank. The Third Army was to take Kosovo and, if necessary, to assist the First Army by attacking the Vardar Army's left flank and rear. The Ibar Army and the Javor brigade had minor roles in the plan and were expected to secure the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and to replace the Third Army in Kosovo after it had advanced south.

The Serbian army, under General (later Marshal) Putnik, achieved three decisive victories in

The Serbian army, under General (later Marshal) Putnik, achieved three decisive victories in

Massacres of Albanians were perpetrated on several occasions by Serbian and Montenegrin armies and paramilitaries during the Balkan Wars.Leo Freundlich: Albania's Golgotha

Massacres of Albanians were perpetrated on several occasions by Serbian and Montenegrin armies and paramilitaries during the Balkan Wars.Leo Freundlich: Albania's Golgotha

According to contemporary accounts, between 10,000 and 25,000 Albanians were killed or died because of hunger and cold during that period;

many of the victims were children, women and the elderly. According to an Albanian

The

The

online

* Murray, Nicholas (2013). ''The Rocky Road to the Great War: the Evolution of Trench Warfare to 1914.'' Dulles, Virginia, Potomac Books * Pettifer, James. ''War in the Balkans: Conflict and Diplomacy Before World War I'' (IB Tauris, 2015). * * * Trix, Frances. "Peace-mongering in 1913: the Carnegie International Commission of Inquiry and its Report on the Balkan Wars." ''First World War Studies'' 5.2 (2014): 147–162. * * * Further reading * * *

Balkan Wars 1912–1913

, in

1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War

Map of Europe during First Balkan War at omniatlas.com

Films about the Balkan War at europeanfilmgateway.eu

Clemmesen, M. H. Not Just a Prelude: The First Balkan War Crisis as the Catalyst of Final European War Preparations (2012)

Anderson, D. S. The Apple of Discord: The Balkan League and the Military Topography of the First Balkan War (1993)

Major 1914 primary sources from BYU

{{Authority control Wars of independence 1912 in the Ottoman Empire 1913 in the Ottoman Empire Conflicts in 1912 Conflicts in 1913 Wars involving Serbia Wars involving Bulgaria Wars involving Montenegro Wars involving Greece Modern history of Greek Macedonia Wars involving the Ottoman Empire 1912 in Bulgaria 1912 in Serbia 1912 in Greece 1912 in Montenegro 1913 in Bulgaria 1913 in Serbia 1913 in Greece 1913 in Montenegro History of Samos

Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

(the Kingdoms of Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

) against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

states' combined armies overcame the initially numerically inferior (significantly superior by the end of the conflict) and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies, achieving rapid success.

The war was a comprehensive and unmitigated disaster for the Ottomans, who lost 83% of their European territories and 69% of their European population.''Balkan Savaşları ve Balkan Savaşları'nda Bulgaristan''Süleyman Uslu As a result of the war, the League captured and partitioned almost all of the Ottoman Empire's remaining territories in Europe. Ensuing events also led to the creation of an

independent Albania

Independent Albania ( sq, Shqipëria e Pavarur) was a parliamentary state declared in Vlorë (at the time part of Ottoman Empire) on 28 November 1912. Its assembly was constituted on the same day while its government and senate were established o ...

, which angered the Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian ancestry, culture, history and language.

The majority of Serbs live in their ...

. Bulgaria, meanwhile, was dissatisfied over the division of the spoils in Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

, and attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 June 1913 which provoked the start of the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

.

Background

Tensions among theBalkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of Ottoman-controlled Rumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians from the Byzantine rite, was the name of a hi ...

(Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia ( bg, Източна Румелия, Iztochna Rumeliya; ota, , Rumeli-i Şarkî; el, Ανατολική Ρωμυλία, Anatoliki Romylia) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, ''vilayet'' in Turkish) in the Otto ...

, Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

) subsided somewhat after the mid-19th-century intervention by the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

, which aimed to secure both a more complete protection for the provinces' Christian majority as well as to maintain the status quo. By 1867, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hung ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

had both secured their independence, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin (1878)

The Treaty of Berlin (formally the Treaty between Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Great Britain and Ireland, Italy, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire for the Settlement of Affairs in the East) was signed on 13 July 1878. In the aftermath of the ...

. The question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Constit ...

in July 1908, which compelled the Ottoman Sultan to restore the suspended constitution of the empire.

Serbia's aspirations to take over Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and ...

were thwarted by the Bosnian crisis, which led to the Austrian annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then directed their war efforts to the south. After the annexation, the Young Turks tried to induce the Muslim population of Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and H ...

to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. Those who took up the offer were resettled by the Ottoman authorities in districts of northern Macedonia with few Muslims. The experiment proved to be a catastrophe since the immigrants readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims and participated in the series of 1911 Albanian uprisings and the Albanian revolt of 1912. Some Albanian government troops switched sides.

In May 1912, Albanian rebels seeking national autonomy and the re-installment of Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

to power, drove the Young Turkish forces out of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; ...

and pressed south towards Manastir (now Bitola

Bitola (; mk, Битола ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba (North Macedonia), Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, north of th ...

), forcing the Young Turks to grant effective autonomy over large regions in June 1912. Serbia, which had helped the arming of Albanian Catholic and Hamidian rebels and sent secret agents to some of the prominent leaders, took the revolt as a pretext for war. Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria had all been in talks about possible offensives against the Ottoman Empire before the 1912 Albanian revolt had broken out, and a formal agreement between Serbia and Montenegro had been signed on 7 March. On 18 October 1912, King Peter I of Serbia

Peter I ( sr-Cyr, Петар I Карађорђевић, Petar I Кarađorđević; – 16 August 1921) was the last king of Serbia, reigning from 15 June 1903 to 1 December 1918. On 1 December 1918, he became the first king of the Serbs, C ...

issued a declaration, 'To the Serbian People', which appeared to support Albanians as well as Serbs:

In a search for allies, Serbia was ready to negotiate a treaty with Bulgaria. The agreement provided that in the event of victory against the Ottomans, Bulgaria would receive all of Macedonia south of the Kriva Palanka

Kriva Palanka ( mk, Крива Паланка ) is a town located in the northeastern part of North Macedonia. It has 14,558 inhabitants. The town of Kriva Palanka is the seat of Kriva Palanka Municipality which has almost 21,000 inhabitants.

...

–Ohrid

Ohrid ( mk, Охрид ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording a population of over 42,000 inh ...

line. Serbia's expansion was accepted by Bulgaria as being to the north of the Shar Mountains (Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Eur ...

). The intervening area was agreed to be "disputed" and would be arbitrated by the Tsar of Russia

This is a list of all reigning monarchs in the history of Russia. It includes the princes of medieval Rus′ state (both centralised, known as Kievan Rus′ and feudal, when the political center moved northeast to Vladimir and finally to Mosco ...

in the event of a successful war against the Ottoman Empire. During the course of the war, it became apparent that the Albanians did not consider Serbia as a liberator, as had been suggested by King Peter I, and the Serbian forces failed to observe his declaration of amity toward Albanians.

After the successful coup d'état for unification

Unification or unification theory may refer to:

Computer science

* Unification (computer science), the act of identifying two terms with a suitable substitution

* Unification (graph theory), the computation of the most general graph that subs ...

with Eastern Rumelia, Bulgaria began to dream that its national unification would be realized. For that purpose, it developed a large army and identified as the "Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

of the Balkans". However, Bulgaria could not win a war alone against the Ottomans.

In Greece, Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is th ...

officers had rebelled in the Goudi coup

The Goudi coup ( el, κίνημα στο Γουδί) was a military coup d'état that took place in Greece on the night of , starting at the barracks in Goudi, a neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of Athens. The coup was a pivotal event in mo ...

of August 1909 and secured the appointment of a progressive government under Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greeks, Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberati ...

, which they hoped would resolve the Crete question in Greece's favor. They also wanted to reverse their defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1897)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

by the Ottomans. An emergency military reorganization, led by a French military mission, had been started for that purpose, but its work was interrupted by the outbreak of war in the Balkans. In the discussions that led Greece to join the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

, Bulgaria refused to commit to any agreement on the distribution of territorial gains, unlike its deal with Serbia over Macedonia. Bulgaria's diplomatic policy was to push Serbia into an agreement that limited its access to Macedonia but, at the same time, to refuse any such agreement with Greece. Bulgaria believed that its army would be able to occupy the larger part of Aegean Macedonia and the important port city of Salonica (Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

) before the Greeks could do so.

In 1911, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

had launched an invasion of Tripolitania, now in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

, which was quickly followed by the occupation of the Dodecanese Islands

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans an ...

. The Italians' decisive military victories over the Ottoman Empire and the successful 1912 Albanian revolt encouraged the Balkan states to imagine that they might win a war against the Ottomans. By the spring and the summer of 1912, the various Christian Balkan nations had created a network of military alliances, which became known as the Balkan League.

The Great Powers, most notably France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, reacted to the formation of the alliances by trying unsuccessfully to dissuade the Balkan League from going to war. In late September, both the League and the Ottoman Empire mobilized their armies. Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = ...

was the first to declare war, on 25 September ( O.S.)/8 October. After issuing an impossible ultimatum to the Ottoman Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

on 13 October, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece declared war on the Ottomans on 17 October (1912). The declarations of war attracted a large number of war correspondents. An estimated 200 to 300 journalists from around the world covered the war in the Balkans in November 1912.

Order of battle and plans

order of battle

In modern use, the order of battle of an armed force participating in a military operation or campaign shows the hierarchical organization, command structure, strength, disposition of personnel, and equipment of units and formations of the armed ...

had a total of 12,024 officers, 324,718 other ranks, 47,960 animals, 2,318 artillery pieces and 388 machine guns. A total of 920 officers and 42,607 men of them had been assigned in non-divisional units and services, the remaining 293,206 officers and men being assigned into four armies.

Opposing them and continuing their secret prewar settlements for expansion, the three Slavic allies (Bulgarian, Serbs and Montenegrins) had extensive plans to co-ordinate their war efforts: the Serbs and the Montenegrins in the theatre of Sandžak

Sandžak (; sh, / , ; sq, Sanxhaku; ota, سنجاق, Sancak), also known as Sanjak, is a historical geo-political region in Serbia and Montenegro. The name Sandžak derives from the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, a former Ottoman administrative dis ...

and the Bulgarians and the Serbs in the Macedonian and the Bulgarians alone in the Thracia

Thracia or Thrace ( ''Thrakē'') is the ancient name given to the southeastern Balkan region, the land inhabited by the Thracians. Thrace was ruled by the Odrysian kingdom during the Classical and Hellenistic eras, and briefly by the Greek ...

n theater.

The bulk of the Bulgarian forces (346,182 men) was to attack Thrace and to be pitted against the Thracian Ottoman Army of 96,273 men and about 26,000 garrison troops, or about 115,000 in total, according to Hall's, Erickson's and the Turkish General Staff's 1993 studies. The remaining Ottoman army of about 200,000Erickson (2003), p. 170 was in Macedonia, to be pitted against the Serbian (234,000 Serbs and 48,000 Bulgarians under Serbian command) and Greek (115,000 men) armies. It was divided into the Vardar and Macedonian Ottoman armies, with independent static guards around the fortress cities of Ioannina

Ioannina ( el, Ιωάννινα ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus, an administrative region in north-western Greece. According to the 2011 census, the ...

(against the Greeks in Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

) and Shkodër

Shkodër ( , ; sq-definite, Shkodra) is the fifth-most-populous city of the Republic of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. The city sprawls across the Plain of Mbishkodra between the southern part of Lake Sh ...

(against the Montenegrins in northern Albania).

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was militarily the most powerful of the four Balkan states, with a large, well-trained and well-equipped army.Hall (2000), p. 16 Bulgaria mobilized a total of 599,878 men out of a population of 4.3 million.Hall (2000), p. 18 The Bulgarian field army counted for nine infantry divisions, one cavalry division and 1,116 artillery units. The commander-in-chief was TsarFerdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

, and the operating command was in the hands of his deputy, General Mihail Savov

Mihail Georgiev Savov ( bg, Михаил Савов) (14 November 1857 in Stara Zagora - 21 July 1928 in Saint-Vallier-de-Thiey, France) was a Bulgarian general, twice Minister of Defence (1891–1894 and 1903–1907), second in command of the Bul ...

. The Bulgarians also had a small navy of six torpedo boats, which were restricted to operations along the country's Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

coast.Hall (2000), p. 17

Bulgaria was focused on actions in Thrace and Macedonia. It deployed its main force in Thrace by forming three armies. The First Army (79,370 men), under General Vasil Kutinchev

Vasil Ivanov Kutinchev ( bg, Васил Иванов Кутинчев) (born 25 February 1859 in Rusçuk; died 30 March 1941) was a Bulgarian officer. He began his military career in 1879 after graduating from the Military School in Sofia . On 13 ...

, had three infantry divisions and was deployed to the south of Yambol

Yambol ( bg, Ямбол ) is a town in Southeastern Bulgaria and administrative centre of Yambol Province. It lies on both banks of the Tundzha river in the historical region of Thrace. It is occasionally spelled ''Jambol''.

Yambol is the ad ...

and assigned operations along the Tundzha

The Tundzha ( bg, Тунджа , tr, Tunca , el, Τόνζος ) is a river in Bulgaria and Turkey (known in antiquity as the Tonsus) and the most significant tributary of the Maritsa, emptying into it on Turkish territory near Edirne.

The riv ...

River. The Second Army (122,748 men), under General Nikola Ivanov

Nikola Ivanov ( bg, Никола Иванов) (2 March 1861, Kalofer – 10 September 1940, Sofia) was a Bulgarian general and a minister of defence of the Kingdom of Bulgaria.

One of the first graduate of the General Staff Military Academy ...

, with two infantry divisions and one infantry brigade, was deployed west of the First Army and was assigned to capture the strong fortress of Adrianople (Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

). Plans had the Third Army (94,884 men), under General Radko Dimitriev

Radko Dimitriev ( bg, Радко Димитриев) (24 September 1859 in Gradets – 18 October 1918 near Pyatigorsk) was a Bulgarian general, Head of the General Staff of the Bulgarian Army from 1 January 1904 to 28 March 1907, as wel ...

, to be deployed east of and behind the First Army and to be covered by the cavalry division that hid it from the Ottomans' sight. The Third Army had three infantry divisions and was assigned to cross Mount Stranja and to take the fortress of Kirk Kilisse (Kırklareli

Kırklareli () is a city within Kırklareli Province in the European part of Turkey.

Name

It is not clearly known when the city was founded, nor under what name. The Byzantine Greeks called it Sarànta Ekklisiès (''Σαράντα Εκκλησι� ...

). The 2nd (49,180) and 7th (48,523 men) Divisions were assigned independent roles, operating in Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a geographic and historic ...

and Eastern Macedonia, respectively.

Armenian Volunteers

Three hundred Armenians from throughout the Ottoman Empire, Europe, and Russia, a small yet significant number, volunteered to fight on the side of the Balkan League’s 750,000 soldiers. Under the leadership ofAndranik Ozanian

Andranik Ozanian, commonly known as General Andranik or simply Andranik;. Also spelled Antranik or Antranig 25 February 186531 August 1927), was an Armenian military commander and statesman, the best known '' fedayi'' and a key figure of the ...

and Garegin Nzhdeh

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan, better known by his ''nom de guerre'' Garegin Nzhdeh ( hy, Գարեգին Նժդեհ, ; 1 January 1886 – 21 December 1955), was an Armenian statesman, military commander and political thinker. As a member of the Arme ...

, the Armenian detachment was commissioned to fight the Ottomans first at Momchilgrad

Momchilgrad ( bg, Момчилград , , Turkish: Mestanlı); is a town in the very south of Bulgaria, part of Kardzhali Province in the southern part of the Eastern Rhodopes. According to the 2011 census, Momchilgrad is the largest Bulgarian s ...

and Komotini

Komotini ( el, Κομοτηνή, tr, Gümülcine, bg, Комотини) is a city in the region of East Macedonia and Thrace, northeastern Greece. It is the capital of the Rhodope. It was the administrative centre of the Rhodope-Evros super-pr ...

and its environs, and then later İpsala

İpsala (, ) is a town and district of Edirne Province in northwestern Turkey. It is the location of one of the main border checkpoints between Greece and Turkey. (The Greek town opposite İpsala is Kipoi.) The population is 8,332 (the city) an ...

, Keşan

Keşan is the name of a district of Edirne Province, Turkey, and also the name of the largest in the district town of Keşan ( bg, Кешан; gr, Κεσσάνη, Byzantine Greek: Ρουσιον, ''Rusion'') In 2010 Keşan had a permanent popula ...

, and Malkara

Malkara ( el, Μάλγαρα, Malgara) is a town and district of Tekirdağ Province in the Marmara region of Turkey. It is located at 55 km west of Tekirdağ and 190 km from Istanbul. It covers an area of 1,225 km², which makes ...

, and Tekirdağ

Tekirdağ (; see also its other names) is a city in Turkey. It is located on the north coast of the Sea of Marmara, in the region of East Thrace. In 2019 the city's population was 204,001.

Tekirdağ town is a commercial centre with a harbou ...

.

Serbia

Serbia called upon about 255,000 men, out of a population of 2,912,000, with about 228 heavy guns, grouped in ten infantry divisions, two independent brigades and a cavalry division, under the effective command of the former war minister,Radomir Putnik

Radomir Putnik ( sr, Радомир Путник; ; 24 January 1847 – 17 May 1917) was the first Serbian Field Marshal and Chief of the General Staff of the Serbian army in the Balkan Wars and in the First World War. He served in every war in ...

. The Serbian High Command, in its prewar war games, had concluded that the most likely site for the decisive battle against the Ottoman Vardar Army

The Vardar Army of the Ottoman Empire ( Turkish: ''Vardar Ordusu'') was one of the field armies under the command of the Western Army. It was formed during the mobilisation phase of the First Balkan War.

Order of Battle, October 19, 1912

On O ...

would be on the Ovče Pole

Ovče Pole ( mk, Овче Поле, literally 'sheep plain') is a plain near Sveti Nikole's River, which is a tributary of the Bregalnica River in east-central North Macedonia.

History

The Battle of Ovche Pole occurred during the First World Wa ...

Plateau, ahead of Skopje. Thus, the main forces were formed in three armies for the advance towards Skopje and a division and an independent brigade were to co-operate with the Montenegrins in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar ( sh-Latn-Cyrl, Novopazarski sandžak, Новопазарски санџак; tr, Yeni Pazar sancağı) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and ...

.

The First Army (132,000 men), the strongest, was commanded by Crown Prince Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

and Chief of Staff was Colonel Petar Bojović

Petar Bojović (, ; 16 July 1858 – 19 January 1945) was a Serbian military commander who fought in the Serbo-Turkish War, the Serbo-Bulgarian War, the First Balkan War, the Second Balkan War, World War I and World War II. Following the bre ...

. The First Army formed the centre of the drive towards Skopje. The Second Army (74,000 men) was commanded by General Stepa Stepanović

Stepan "Stepa" Stepanović ( sr-cyr, Степан Степа Степановић, ; – 29 April 1929) was a Serbian military commander who fought in the Serbo-Turkish War, the Serbo-Bulgarian War, the First Balkan War, the Second Bal ...

and had one Serbian and one Bulgarian (7th Rila) division. It formed the army's left wing and advanced towards Stracin

Stracin or Stratsin ( mk, Страцин) is a village in the municipality of Kratovo, North Macedonia.

Demographics

According to the 2002 census, the village had a total of 185 inhabitants. Ethnic groups in the village include:Macedonian Census ...

. The inclusion of a Bulgarian division was according to a prewar arrangement between Serbian and Bulgarian armies, but the division ceased to obey the orders of Stepanović as soon as the war began but followed only the orders of the Bulgarian High Command. The Third Army (76,000 men) was commanded by General Božidar Janković

Božidar Janković ( sr-Cyrl, Божидар Јанковић; 7 December 1849 – 7 July 1920) was a Serbian army general commander of the Serbian Third Army during the First Balkan War between the Balkan League and the Ottoman Empire. In 1901 ...

, and since it was on the right wing, had the task to invade Kosovo and then move south to join the other armies in the expected battle at Ovče Polje. There were two other concentrations in northwestern Serbia across the borders between Serbia and Austria-Hungary: the Ibar Army (25,000 men), under General Mihailo Živković

Mihailo Zivković-Gvozdeni (Belgrade, Principality of Serbia 29 August 1856 - Belgrade, Kingdom of Serbia, 28 April 1930) was a Serbian general and a minister of war.

Zivković-Gvozdeni commanded forces in the Serbian-Turkish wars, the Serbo ...

, and the Javor Brigade (12,000 men), under Lieutenant-Colonel Milovoje Anđelković.

Greece

Greece, whose population was then 2,666,000,Erickson (2003), p. 70 was considered the weakest of the three main allies since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered a defeat against the Ottomans 16 years earlier, in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. A British consular dispatch from 1910 expressed the common perception of the Greek army's abilities: "if there is war we shall probably see that the only thing Greek officers can do besides talking is to run away".Fotakis (2005), p. 42 However, Greece was the only Balkan country to possess a substantial navy, which was vital to the League to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. That was readily appreciated by the Serbs and the Bulgarians and was the chief factor in initiating the process of Greece's inclusion in the League. As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry into the League, "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between

Greece, whose population was then 2,666,000,Erickson (2003), p. 70 was considered the weakest of the three main allies since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered a defeat against the Ottomans 16 years earlier, in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. A British consular dispatch from 1910 expressed the common perception of the Greek army's abilities: "if there is war we shall probably see that the only thing Greek officers can do besides talking is to run away".Fotakis (2005), p. 42 However, Greece was the only Balkan country to possess a substantial navy, which was vital to the League to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. That was readily appreciated by the Serbs and the Bulgarians and was the chief factor in initiating the process of Greece's inclusion in the League. As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry into the League, "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between Salonica

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region ...

and Gallipoli."

The Greek army was still undergoing reorganisation by a French military mission, which arrived in early 1911. Under French supervision, the Greeks had adopted the triangular infantry division as their main formation, but more importantly, the overhaul of the mobilization system allowed the country to field and equip a far greater number of troops than had been the case in 1897. Foreign observers estimated Greece would mobilize a force of approximately 50,000 men, but the Greek army fielded 125,000, with another 140,000 in the National Guard and reserves. Upon mobilisation, as in 1897, the force was grouped in two field armies, reflecting the geographic division between the two operational theatres that were open to the Greeks: Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, The ...

and Epirus. The Army of Thessaly

The Army of Thessaly ( el, Στρατιά Θεσσαλίας) was a field army of Greece, activated in Thessaly during the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and the First Balkan War in 1912, both times against the Ottoman Empire and commanded by Crown Pri ...

(Στρατιά Θεσσαλίας) was placed under Crown Prince Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given nam ...

, with Lieutenant-General Panagiotis Danglis

Panagiotis Danglis ( el, Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής; – 9 March 1924) was a Greek Army general and politician. He is particularly notable for his invention of the Schneider-Danglis mountain gun, his service as chief of staff in the Balk ...

as his chief of staff. It fielded the bulk of the Greek forces: seven infantry divisions, a cavalry regiment and four independent Evzones

The Evzones or Evzonoi ( el, Εύζωνες, Εύζωνοι, ) were several historical elite light infantry and mountain units of the Greek Army. Today, they are the members of the Presidential Guard ( el, Προεδρική Φρουρά , tran ...

light mountain infantry battalions, roughly 100,000 men. It was expected to overcome the fortified Ottoman border positions and advance towards southern and central Macedonia, aiming to take Thessaloniki and Bitola. The remaining 10,000 to 13,000 men in eight battalions were assigned to the Army of Epirus The following is the order of battle of the Hellenic Army during the First Balkan War.

Background

Greece, a state of 2,666,000 people in 1912,Erickson (2003), p. 70 was considered the weakest of the three main Balkan allies, since it fielded th ...

() under Lieutenant-General Konstantinos Sapountzakis

Konstantinos Sapountzakis ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Σαπουντζάκης; 1846–1931) was a Hellenic Army officer. He is notable as the first head of the Hellenic Army General Staff and as the first commander of the Army of Epirus during ...

. As it had no hope of capturing Ioannina, the heavily fortified capital of Epirus, the initial mission was to pin down the Ottoman forces there until sufficient reinforcements could be sent from the Army of Thessaly after the successful conclusion of operations.

The Greek navy was relatively modern, strengthened by the recent purchase of numerous new units and undergoing reforms under the supervision of a British mission. Invited by Greek Prime Minister Venizelos in 1910, the mission began its work upon its arrival in May 1911. Granted extraordinary powers and led by Vice Admiral Lionel Grant Tufnell

Lionel Grant Tufnell (27 October 1857 – 11 August 1930) was an officer of the British Royal Navy, where he reached the rank of rear admiral.

In 1911, while commandant of the Royal Naval Engineering College, he was chosen to head the British nav ...

, it thoroughly reorganized the Navy Ministry and dramatically improved the number and the quality of exercises in gunnery and fleet maneuvers.Fotakis (2005), pp. 25–35 In 1912, the core unit of the fleet was the fast armoured cruiser ''Georgios Averof'', which had been completed in 1910 and then was the fastest and the most modern warship in the combatant navies. It was complemented by three rather-antiquated battleships of the . There were also eight destroyers, built in 1906–1907, and six new destroyers, hastily bought in summer 1912 as the imminence of war became apparent.

Nevertheless, at the outbreak of the war, the Greek fleet was far from ready. The Ottoman battlefleet retained a clear advantage in number of ships, speed of the main surface units and, most importantly, number and caliber of the ships' guns. In addition, as the war caught the fleet in the middle of its expansion and reorganization, a full third of the fleet (the six new destroyers and the submarine ) reached Greece only after hostilities had started, forcing the navy to reshuffle crews, who consequently suffered from lacking familiarity and training. Coal stockpiles and other war stores were also in short supply, and the ''Georgios Averof'' had arrived with barely any ammunition and remained so until late November.

Montenegro

Montenegro was the smallest nation in the Balkan Peninsula, but in recent years before the war, with support fromRussia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

, it had improved its military skills. Also, it was the only Balkan country never to be fully conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Montenegro being the smallest member of the League, did not have much influence. However, it was advantageous for Montenegro, since when the Ottoman Empire was trying to counter the actions of Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece, there was enough time for Montenegro to prepare, which helped its successful military campaign.

Ottoman Empire

In 1912, the Ottomans were in a difficult position. They had a large population, 26 million, but just over 6.1 million of them lived in its European part, only 2.3 million being Muslims. The rest were Christians, who were considered unfit for conscription. The very poor transport network, especially in the Asian part, dictated that the only reliable way for a mass transfer of troops to the European theatre was by sea, but that faced the risk of the Greek fleet in the Aegean Sea. In addition, the Ottomans were still engaged in a protracted war against Italy in Libya (and by now in theDodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited ...

islands of the Aegean), which had dominated the Ottoman military effort for over a year. The conflict lasted until 15 October, a few days after the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans. The Ottomans were unable to reinforce their positions in the Balkans significantly as their relations with the Balkan states deteriorated over the course of the year.

Forces in Balkans

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by a number of factors, such as domestic strife, caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counterrevolutionary coup several months later. That resulted in different groups competing for influence within the military. A German mission had tried to reorganize the army, but its recommendations had not been fully implemented. The Ottoman army was caught in the middle of reform and reorganisation. Also, several of the army's best battalions had been transferred to

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by a number of factors, such as domestic strife, caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counterrevolutionary coup several months later. That resulted in different groups competing for influence within the military. A German mission had tried to reorganize the army, but its recommendations had not been fully implemented. The Ottoman army was caught in the middle of reform and reorganisation. Also, several of the army's best battalions had been transferred to Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

to face the ongoing rebellion there. In the summer of 1912, the Ottoman High Command made the disastrous decision to dismiss some 70,000 mobilised troops. The regular army (''Nizam'') was well-equipped and had trained active divisions, but the reserve units (''Redif'') that reinforced it were ill-equipped, especially in artillery, and badly-trained.

The Ottomans' strategic situation was difficult, as their borders were almost impossible to defend against a coordinated attack by the Balkan states. The Ottoman leadership decided to defend all of their territory. As a result, the available forces, which could not be easily reinforced from Asia because of Greek control of the sea and the inadequacy of the Ottoman railway system, were dispersed too thinly across the region. They failed to stand up to the rapidly-mobilized Balkan armies. The Ottomans had three armies in Europe (the Macedonian, Vardar and Thracian Armies), with 1,203 pieces of mobile and 1,115 fixed artillery on fortified areas. The Ottoman High Command repeated its error of previous wars by ignoring the established command structure to create new superior commands, the Eastern Army and Western Army, reflecting the division of the operational theatre between the Thracian (against the Bulgarians) and Macedonian (against the Greeks, Serbs and Montenegrins) fronts.

The Western Army fielded at least 200,000 men, and the Eastern Army fielded 115,000 men against the Bulgarians.Hall (2000), p. 22 The Eastern Army was commanded by Nazim Pasha

Subahdar, also known as Nazim or in English as a "Subah", was one of the designations of a governor of a Subah (province) during the Khalji dynasty of Bengal, Mamluk dynasty (Delhi), Khalji dynasty, Tughlaq dynasty, Mughal era ( of India who was ...

and had seven corps of 11 regular infantry divisions, 13 Redif divisions and at least one cavalry divisions:

* I Corps I Corps, 1st Corps, or First Corps may refer to:

France

* 1st Army Corps (France)

* I Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* I Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Arm ...

with three divisions (2nd Infantry (minus regiment), 3rd Infantry and 1st Provisional divisions).

* II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

with three divisions (4th (minus regiment) and 5th Infantry and Uşak Redif divisions).

* III Corps 3rd Corps, Third Corps, III Corps, or 3rd Army Corps may refer to:

France

* 3rd Army Corps (France)

* III Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* III Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of th ...

with four divisions (7th, 8th and 9th Infantry Divisions, all minus a regiment, and the Afyonkarahisar Redif Division).

* IV Corps with three divisions (12th Infantry Division (minus regiment), İzmit and Bursa Redif divisions).

* XVII Corps with three divisions (Samsun, Ereğli and İzmir Redif divisions).

* Edirne Fortified Area with six-plus divisions (10th and 11th Infantry, Edirne, Babaeski and Gümülcine Redif and the Fortress division, 4th Rifle and 12th Cavalry regiments).

* Kırcaali Detachment

The Kırcaali Detachment of the Ottoman Empire ( Modern Turkish: ''Kırcaali Müfrezesi'' or ''Kırcaali Kolordusu'' ) was one of the Detachments under the command of the Ottoman Eastern Army. It was formed in Kırcaali (present day: Kardzhal ...

with two-plus divisions (Kırcaali Redif, Kırcaali Mustahfız division and 36th Infantry Regiment).

* An independent cavalry division and the 5th Light Cavalry Brigade.

The Western Army (Macedonian and Vardar Army) was composed of ten corps with 32 infantry and two cavalry divisions. Against Serbia, the Ottomans deployed the Vardar Army (HQ in Skopje) under Halepli Zeki Pasha, with five corps of 18 infantry divisions, one cavalry division and two independent cavalry brigades under the:

* V Corps 5th Corps, Fifth Corps, or V Corps may refer to:

France

* 5th Army Corps (France)

* V Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* V Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Ar ...

with four divisions (13th, 15th, 16th Infantry and the İştip Redif divisions)

* VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army dur ...

with four divisions (17th, 18th Infantry and the Manastır and Drama Redif divisions)

* VII Corps 7th Corps, Seventh Corps, or VII Corps may refer to:

* VII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* VII R ...

with three division (19th Infantry and Üsküp and Priştine Redif divisions)

* II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

with three divisions (Uşak, Denizli and İzmir Redif divisions)

* Sandžak Corps with four divisions (20th Infantry (minus regiment), 60th Infantry, Metroviça Redif Division, Taşlıca Redif Regiment, Firzovik and Taslica detachments)

* An independent Cavalry Division and the 7th and 8th Cavalry Brigades.

The Macedonian Army (headquarters in Thessaloniki under Ali Rıza Pasha

Ali Rıza Pasha (1860–1932) was an Ottoman military officer and statesman, who was one of the last Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire, under the reign of the last Ottoman Sultan Mehmed VI, between 14 October 1919 and 2 March 1920.İsmail Hâ ...

) had 14 divisions in five corps, deployed against Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro.

Against Greece, at least seven divisions were deployed:

* VIII Provisional Corps with three divisions (22nd Infantry and Nasliç and Aydın Redif divisions).

* Yanya Corps

The Yanya Corps or Independent Yanya Corps of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Yanya Kolordusu) was one of the major formations under the command of the Ottoman Western Army. It was formed in Yanya (present-day Ioannina) area during the First Balkan War. ...

with three divisions (23rd Infantry, Yanya Redif and Bizani Fortress divisions).

* Selanik Redif division and Karaburun Detachment

Karaburun ( el, Αχιρλί, Achirlí) is a district and the center town of the same district in Turkey's İzmir Province. The district area roughly corresponds to the peninsula of the same name ( Karaburun Peninsula) which spears north of the t ...

as independent units.

Against Bulgaria, in southeastern Macedonia, two divisions, the Struma Corps