Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of

belief

A belief is an attitude that something is the case, or that some proposition is true. In epistemology, philosophers use the term "belief" to refer to attitudes about the world which can be either true or false. To believe something is to take i ...

in the existence of

deities

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

.

Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist.

In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no deities.

Atheism is contrasted with

theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

,

which in its most general form is the belief that

at least one deity exists.

The

first individuals to identify themselves as atheists lived in the 18th century during the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

The

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, noted for its "unprecedented atheism", witnessed the first significant political movement in history to advocate for the supremacy of human

reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

.

[Extract of page 22]

In 1967, Albania declared itself the first

official atheist country according to its policy of

state Marxism.

Arguments for atheism range from philosophical to social and historical approaches. Rationales for not believing in deities include the lack of

evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, evidenc ...

,

the

problem of evil

The problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering with an omnipotent, omnibenevolent, and omniscient God.The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,The Problem of Evil, Michael TooleyThe Internet Encyclope ...

, the

argument from inconsistent revelations

Religious pluralism is an attitude or policy regarding the diversity of religious belief systems co-existing in society. It can indicate one or more of the following:

* Recognizing and tolerating the religious diversity of a society or countr ...

, the rejection of concepts that cannot

be falsified, and the

argument from nonbelief

An argument from nonbelief is a philosophical argument that asserts an inconsistency between the existence of God and a world in which people fail to recognize him. It is similar to the classic argument from evil in affirming an inconsistency ...

.

Nonbelievers contend that atheism is a more

parsimonious

Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, or Ocham's razor ( la, novacula Occami), also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony ( la, lex parsimoniae), is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond neces ...

position than theism and that everyone is born without beliefs in deities;

therefore, they argue that the

burden of proof lies not on the atheist to disprove the existence of gods but on the theist to provide a rationale for theism. Although some atheists have adopted

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

philosophies (e.g.

secular humanism

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality an ...

),

there is no ideology or code of conduct to which all atheists adhere.

Since conceptions of atheism vary, accurate estimations of current

numbers of atheists are difficult. Scholars have indicated that

global atheism may be in decline due to irreligious countries having the lowest birth rates in the world and religious countries having higher birth rates in general.

Definitions and types

Writers disagree on how best to define and classify ''atheism'',

contesting what supernatural entities are considered gods, whether atheism is a philosophical position in its own right or merely the absence of one, and whether it requires a conscious, explicit rejection. However the norm is to define atheism in terms of an explicit stance against theism.

Atheism has been regarded as compatible with

agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

,

but has also been contrasted with it.

Range

Some of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining ''atheism'' arises from difficulty in reaching a consensus for the definitions of words like ''deity'' and ''god''. The variety of wildly different

conceptions of God

Conceptions of God in Monotheism, monotheist, Pantheism, pantheist, and Panentheism, panentheist religions – or of the supreme deity in henotheistic religions – can extend to various levels of abstraction:

* as a Omnipotence, powe ...

and deities lead to differing ideas regarding atheism's applicability. The ancient Romans accused Christians of being atheists for not worshiping the

pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

deities. Gradually, this view fell into disfavor as ''theism'' came to be understood as encompassing belief in any divinity.

With respect to the range of phenomena being rejected, atheism may counter anything from the existence of a deity, to the existence of any

spiritual,

supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

, or

transcendental concepts, such as those of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

,

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

,

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

, and

Taoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of Philosophy, philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of China, Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmo ...

.

Implicit vs. explicit

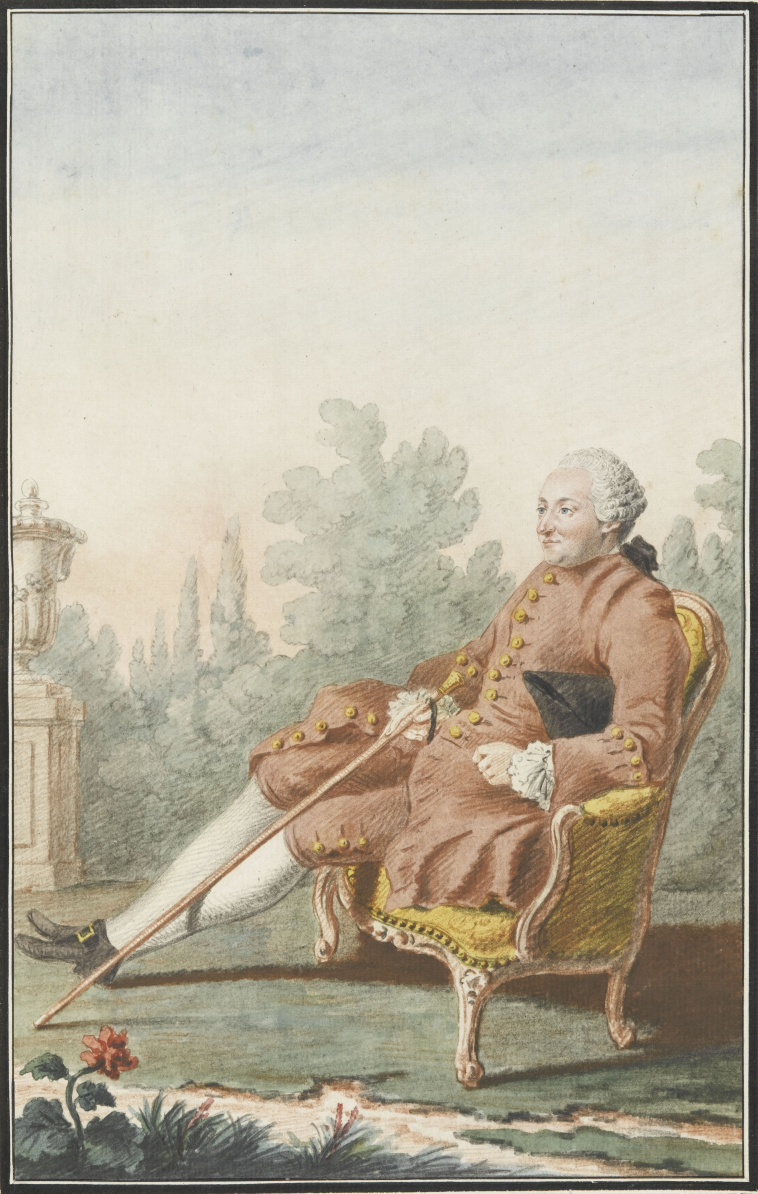

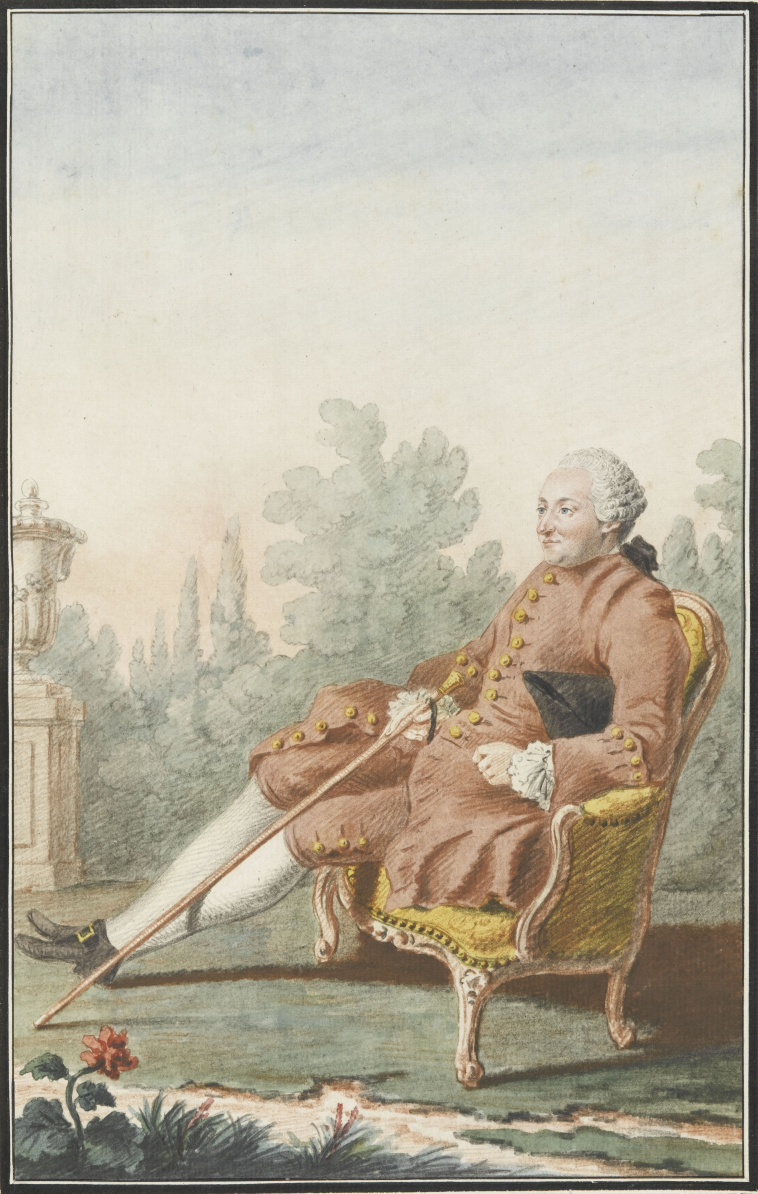

Definitions of atheism also vary in the degree of consideration a person must put to the idea of gods to be considered an atheist. Atheism is commonly defined as the simple absence of belief that any deities exist. This broad definition would include newborns and other people who have not been exposed to theistic ideas. As far back as 1772,

Baron d'Holbach

Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (; 8 December 1723 – 21 January 1789), was a French-German philosopher, encyclopedist, writer, and prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born Paul Heinrich Dietrich in Edesheim, near Land ...

said that "All children are born Atheists; they have no idea of God."

Similarly,

George H. Smith

George Hamilton Smith (February 10, 1949 – April 8, 2022) was an American author, editor, educator, and speaker, known for his writings on atheism and libertarianism.

Biography

Smith grew up mostly in Tucson, Arizona, and attended the Unive ...

suggested that: "The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child with the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist." ''Implicit atheism'' is "the absence of theistic belief without a conscious rejection of it" and ''explicit atheism'' is the conscious rejection of belief.

For the purposes of his paper on "philosophical atheism",

Ernest Nagel

Ernest Nagel (November 16, 1901 – September 20, 1985) was an American philosopher of science. Suppes, Patrick (1999)Biographical memoir of Ernest Nagel In '' American National Biograph''y (Vol. 16, pp. 216-218). New York: Oxford University Pr ...

contested including the mere absence of theistic belief as a type of atheism.

[

]

reprinted in ''Critiques of God'', edited by Peter A. Angeles, Prometheus Books, 1997. Graham Oppy

Graham Robert Oppy (born 1960) is an Australian philosopher whose main area of research is the philosophy of religion. He currently holds the posts of Professor of Philosophy and Associate Dean of Research at Monash University and serves as CEO ...

classifies as ''innocents'' those who never considered the question because they lack any understanding of what a god is. According to Oppy, these could be

one-month-old babies, humans with severe traumatic

brain injuries

Neurotrauma, brain damage or brain injury (BI) is the destruction or degeneration of brain cells. Brain injuries occur due to a wide range of internal and external factors. In general, brain damage refers to significant, undiscriminating t ...

, or patients with

advanced dementia.

Positive vs. negative

Philosophers such as

Antony Flew

Antony Garrard Newton Flew (; 11 February 1923 – 8 April 2010) was a British philosopher. Belonging to the analytic and evidentialist schools of thought, Flew worked on the philosophy of religion. During the course of his career he taught at ...

[: "In this interpretation, an atheist becomes: not someone who positively asserts the non-existence of God; but someone who is simply not a theist. Let us, for future-ready reference, introduce the labels 'positive atheist' for the former and 'negative atheist' for the latter."] and

Michael Martin have contrasted positive (strong/hard) atheism with negative (weak/soft) atheism. Positive atheism is the explicit affirmation that gods do not exist. Negative atheism includes all other forms of non-theism. According to this categorization, anyone who is not a theist is either a negative or a positive atheist.

The terms ''weak'' and ''strong'' are relatively recent, while the terms ''negative'' and ''positive'' atheism are of older origin, having been used (in slightly different ways) in the philosophical literature

and in Catholic apologetics.

While Martin, for example, asserts that agnosticism

entails negative atheism,

many agnostics see their view as distinct from atheism,

which they may consider no more justified than theism or requiring an equal conviction.

The assertion of unattainability of knowledge for or against the existence of gods is sometimes seen as an indication that atheism requires a

leap of faith

A leap of faith, in its most commonly used meaning, is the act of believing in or accepting something outside the boundaries of reason.

Overview

The phrase is commonly attributed to Søren Kierkegaard; however, he never used the term, as he ...

.

Common atheist responses to this argument include that unproven ''

religious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

'' propositions deserve as much disbelief as all ''other'' unproven propositions,

and that the unprovability of a god's existence does not imply an equal probability of either possibility.

Australian philosopher

J.J.C. Smart even argues that "sometimes a person who is really an atheist may describe herself, even passionately, as an agnostic because of unreasonable generalized

philosophical skepticism

Philosophical skepticism ( UK spelling: scepticism; from Greek σκέψις ''skepsis'', "inquiry") is a family of philosophical views that question the possibility of knowledge. It differs from other forms of skepticism in that it even reject ...

which would preclude us from saying that we know anything whatever, except perhaps the truths of mathematics and formal logic."

Consequently, some atheist authors, such as

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ath ...

, prefer distinguishing theist, agnostic, and atheist positions along a

spectrum of theistic probability

Popularized by Richard Dawkins in ''The God Delusion,'' the spectrum of theistic probability is a way of categorizing one's belief regarding the probability of the existence of a deity.

Atheism, theism, and agnosticism

J. J. C. Smart argues ...

—the likelihood that each assigns to the statement "God exists".

Definition as impossible or impermanent

Before the 18th century, the existence of God was so accepted in the Western world that even the possibility of true atheism was questioned. This is called ''theistic

innatism

Innatism is a philosophical and epistemological doctrine that the mind is born with ideas, knowledge, and beliefs. Therefore, the mind is not a ''tabula rasa'' (blank slate) at birth, which contrasts with the views of early empiricists such as ...

''—the notion that all people believe in God from birth; within this view was the connotation that atheists are in denial. There is also a position claiming that atheists are quick to believe in God in times of crisis, that atheists make

deathbed conversion

A deathbed conversion is the adoption of a particular religious faith shortly before dying. Making a conversion on one's deathbed may reflect an immediate change of belief, a desire to formalize longer-term beliefs, or a desire to complete a ...

s, or that "

there are no atheists in foxholes

"There are no atheists in foxholes" is an aphorism used to suggest that times of extreme stress or fear can prompt belief in a higher power. In the context of actual warfare, such a sudden change in belief has been called a foxhole conversion. The ...

". There have, however, been examples to the contrary, among them examples of literal "atheists in foxholes". Some atheists have challenged the need for the term "atheism". In his book ''

Letter to a Christian Nation

''Letter to a Christian Nation'' is a 2006 book by Sam Harris, written in response to feedback he received following the publication of his first book ''The End of Faith''. The book is written in the form of an open letter to a Christian in the U ...

'',

Sam Harris

Samuel Benjamin Harris (born April 9, 1967) is an American philosopher, neuroscientist, author, and podcast host. His work touches on a range of topics, including rationality, religion, ethics, free will, neuroscience, meditation, psychedelics ...

wrote:

In fact, "atheism" is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a "non-astrologer

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Dif ...

" or a "non-alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscience, protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in Chinese alchemy, C ...

". We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.

Etymology

In early

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

, the adjective (, from the

privative ἀ- + "god") meant "godless". It was first used as a term of censure roughly meaning "ungodly" or "impious". In the 5th century BCE, the word began to indicate more deliberate and active godlessness in the sense of "severing relations with the gods" or "denying the gods". The term () then came to be applied against those who impiously denied or disrespected the local gods, even if they believed in other gods. Modern translations of classical texts sometimes render as "atheistic". As an abstract noun, there was also (), "atheism".

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

transliterated the Greek word into the

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. The term found frequent use in the debate between

early Christians

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

and

Hellenists

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 31 ...

, with each side attributing it, in the pejorative sense, to the other.

The term ''atheist'' (from the French ), in the sense of "one who ... denies the existence of God or gods", predates ''atheism'' in English, being first found as early as 1566, and again in 1571. ''Atheist'' as a label of practical godlessness was used at least as early as 1577.

The term ''atheism'' was derived from the

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

,

and appears in English about 1587.

[Rendered as ''Athisme'': ] An earlier work, from about 1534, used the term ''atheonism''.

Related words emerged later: ''deist'' in 1621,

''theist'' in 1662, ''

deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the Philosophy, philosophical position and Rationalism, rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that Empirical evi ...

'' in 1675,

and ''

theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

'' in 1678.

''Deism'' and ''theism'' changed meanings slightly around 1700 due to the influence of ''atheism''; ''deism'' was originally used as a synonym for today's ''theism'' but came to denote a separate philosophical doctrine.

Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong (born 14 November 1944) is a British author and commentator of Irish Catholic descent known for her books on comparative religion. A former Roman Catholic religious sister, she went from a conservative to a more liberal and m ...

writes that "During the 16th and 17th centuries, the word 'atheist' was still reserved exclusively for

polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topics ...

... The term 'atheist' was an insult. Nobody would have dreamed of calling an atheist."

''Atheism'' was first used to describe a self-avowed belief in late 18th-century Europe, specifically denoting disbelief in the

monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford ...

Abrahamic god

The concept of God in Abrahamic religions is centred on monotheism. The three major monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, alongside the Baháʼí Faith, Samaritanism, Druze, and Rastafari, are all regarded as Abrahamic reli ...

.

In the 20th century,

globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

contributed to the expansion of the term to refer to disbelief in all deities, though it remains common in Western society to describe atheism as "disbelief in God".

Arguments

Epistemological arguments

Skepticism

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the pe ...

, based on the ideas of

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

, asserts that certainty about anything is impossible, so one can never know for sure whether or not a god exists. Hume, however, held that such unobservable metaphysical concepts should be rejected as "sophistry and illusion".

The allocation of agnosticism to atheism is disputed; it can also be regarded as an independent, basic worldview.

[.]

There are three main conditions of epistemology: truth, belief and justification.

Michael Martin argues that atheism is a justified and rational true belief, but offers no extended epistemological justification because current theories are in a state of controversy. Martin instead argues for "mid-level principles of justification that are in accord with our ordinary and scientific rational practice."

Other arguments for atheism that can be classified as epistemological or

ontological

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

, including

ignosticism

Ignosticism or igtheism is the idea that the question of the existence of God is meaningless because the word "God" has no coherent and unambiguous definition.

Terminology

The term ''ignosticism'' was coined in 1964 by Sherwin Wine, a rabbi and ...

, assert the meaninglessness or unintelligibility of basic terms such as "God" and statements such as "God is all-powerful."

Theological noncognitivism

Theological noncognitivism is the non-theist position that religious language, particularly theological terminology such as "God", is not intelligible or meaningful, and thus sentences like "God exists" are cognitively meaningless. It may be co ...

holds that the statement "God exists" does not express a proposition, but is nonsensical or cognitively meaningless. It has been argued both ways as to whether such individuals can be classified into some form of atheism or agnosticism. Philosophers

A. J. Ayer

Sir Alfred Jules "Freddie" Ayer (; 29 October 1910 – 27 June 1989), usually cited as A. J. Ayer, was an English philosopher known for his promotion of logical positivism, particularly in his books '' Language, Truth, and Logic'' (1936) ...

and

Theodore M. Drange

Theodore "Ted" Michael Drange (born 1934) is a philosopher of religion and Professor Emeritus at West Virginia University, where he taught philosophy from 1966 to 2001.

Life

After graduating from Fort Hamilton High School, he received a B.A. ...

reject both categories, stating that both camps accept "God exists" as a proposition; they instead place noncognitivism in its own category.

Metaphysical arguments

Philosopher,

Zofia Zdybicka Zofia Józefa Zdybicka (born 5 August 1928 in Kraśnik) is a nun and philosopher. She has been a professor at the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin since 1978. Her order name is Maria Józefa in the Congregation of the Ursulines of the Ag ...

writes:

Most atheists lean toward metaphysical monism: the belief that there is only one kind of ultimate substance. Historically, metaphysical monism took the form of philosophical

materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

, the view that matter formed the basis of all reality; this naturally omitted the possibility of a non-material divine being.

Describing the world as "basically matter" in the twenty-first century would be contrary to modern physics, so it is generally seen as an older term that is sometimes mistakenly used interchangeably with

physicalism

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substanc ...

. Physicalism can incorporate the non-matter based physical phenomena, such as light and energy, into its view that only physical entities with physical powers exist, and that science defines and explains what those are.

Physicalism is a monistic ontology: one ultimate substance exists, and it exists as a physical reality.

Physicalism opposes dualism (the view that there's physical substance and separate mental activities): there is no such thing as a soul, or any other abstract object (such as a mind or a self) that exists independently of physicality. It also opposes neutral monism, which holds to one kind of substance for the universe but makes no claim about its nature, holding to the view that the physical and the mental are both just differing kinds of the same fundamental substance that is in itself neither mental nor physical.

Physicalism also opposes

idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ide ...

(the view that everything known is based on human mental perception).

is also used by atheists to describe the metaphysical view that everything that exists is fundamentally natural, and that there are no supernatural phenomena.

Naturalism focuses on how science can explain the world fully with physical laws and through natural phenomena. It's about the idea that the universe is a closed system. Naturalism can be interpreted to allow for a dualist ontology of the mental and physical.

Philosopher

Graham Oppy

Graham Robert Oppy (born 1960) is an Australian philosopher whose main area of research is the philosophy of religion. He currently holds the posts of Professor of Philosophy and Associate Dean of Research at Monash University and serves as CEO ...

references a PhilPapers survey that says 56.5% of philosophers in academics lean toward physicalism; 49.8% lean toward naturalism.

According to Graham Oppy, direct arguments for atheism aim at showing theism fails on its own terms, while indirect arguments are those inferred from direct arguments in favor of something else that is inconsistent with theism. For example, Oppy says arguing for naturalism is an argument for atheism since naturalism and theism "cannot both be true".

Fiona Ellis says that while Oppy's view is common, it is dependent on a narrow view of naturalism. She describes the "expansive naturalism" of

John McDowell

John Henry McDowell, FBA (born 7 March 1942) is a South African philosopher, formerly a fellow of University College, Oxford, and now university professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Although he has written on metaphysics, epistemology, ...

,

James Griffin and

David Wiggins

David Wiggins (born 1933) is an English moral philosopher, metaphysician, and philosophical logician working especially on identity and issues in meta-ethics.

Biography

David Wiggins was born on 8 March 1933 in London, the son of Norman and D ...

as giving "due respect to scientific findings" while also asserting there are things in human experience which cannot be explained in such terms, such as the concept of value, leaving room for theism.

Christopher C. Knight asserts a

theistic naturalism that relies on what he terms an "incarnational naturalism" (the doctrine of

immanence

The doctrine or theory of immanence holds that the divine encompasses or is manifested in the material world. It is held by some philosophical and metaphysical theories of divine presence. Immanence is usually applied in monotheistic, pantheis ...

) and does not require any special mode of divine action that would put it outside nature.

Nevertheless, Oppy argues that a strong naturalism favors atheism, though he finds the best direct arguments against theism to be the evidential problem of evil, and arguments concerning the contradictory nature of God were He to exist.

Logical arguments

Some atheists hold the view that the various

conceptions of gods, such as the

personal god

A personal god, or personal goddess, is a deity who can be related to as a person, instead of as an impersonal force, such as the Absolute, "the All", or the "Ground of Being".

In the scriptures of the Abrahamic religions, God is described as b ...

of Christianity, are ascribed logically inconsistent qualities. Such atheists present

deductive arguments against the existence of God, which assert the incompatibility between certain traits, such as perfection, creator-status,

immutability

In object-oriented and functional programming, an immutable object (unchangeable object) is an object whose state cannot be modified after it is created.Goetz et al. ''Java Concurrency in Practice''. Addison Wesley Professional, 2006, Section 3.4 ...

,

omniscience

Omniscience () is the capacity to know everything. In Hinduism, Sikhism and the Abrahamic religions, this is an God#General conceptions, attribute of God. In Jainism, omniscience is an attribute that any individual can eventually attain. In B ...

,

omnipresence

Omnipresence or ubiquity is the property of being present anywhere and everywhere. The term omnipresence is most often used in a religious context as an attribute of a deity or supreme being, while the term ubiquity is generally used to describe ...

,

omnipotence

Omnipotence is the quality of having unlimited power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as one o ...

,

omnibenevolence

Omnibenevolence (from Latin ''omni-'' meaning "all", ''bene-'' meaning "good" and ''volens'' meaning "willing") is defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' as "unlimited or infinite benevolence". Some philosophers have argued that it is impo ...

,

transcendence, personhood (a personal being), non-physicality,

justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

, and

mercy

Mercy (Middle English, from Anglo-French ''merci'', from Medieval Latin ''merced-'', ''merces'', from Latin, "price paid, wages", from ''merc-'', ''merxi'' "merchandise") is benevolence, forgiveness, and kindness in a variety of ethical, relig ...

.

atheists believe that the world as they experience it cannot be reconciled with the qualities commonly ascribed to God and gods by theologians. They argue that an

omniscient

Omniscience () is the capacity to know everything. In Hinduism, Sikhism and the Abrahamic religions, this is an attribute of God. In Jainism, omniscience is an attribute that any individual can eventually attain. In Buddhism, there are diffe ...

,

omnipotent

Omnipotence is the quality of having unlimited power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as one of ...

, and

omnibenevolent

Omnibenevolence (from Latin ''omni-'' meaning "all", ''bene-'' meaning "good" and ''volens'' meaning "willing") is defined by the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' as "unlimited or infinite benevolence". Some philosophers have argued that it is impo ...

God is not compatible with a world where there is

evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

and

suffering

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual. Suffering is the basic element that makes up the negative valence of a ...

, and where divine love is

hidden from many people.

A similar argument is attributed to

Siddhartha Gautama

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

, the founder of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. The medieval

Buddhist philosopher Vasubandhu

Vasubandhu (; Tibetan: དབྱིག་གཉེན་ ; floruit, fl. 4th to 5th century CE) was an influential bhikkhu, Buddhist monk and scholar from ''Puruṣapura'' in ancient India, modern day Peshawar, Pakistan. He was a philosopher who ...

(4/5th century) who outlined

numerous Buddhist arguments against God, wrote in his ''Sheath of

Abhidharma

The Abhidharma are ancient (third century BCE and later) Buddhist texts which contain detailed scholastic presentations of doctrinal material appearing in the Buddhist ''sutras''. It also refers to the scholastic method itself as well as the f ...

(

Abhidharmakosha):''

Besides, do you say that God finds joy in seeing the creatures which he has created in the prey of all the distress of existence, including the tortures of the hells? Homage to this kind of God! The profane stanza expresses it well: "One calls him Rudra because he burns, because he is sharp, fierce, redoubtable, an eater of flesh, blood and marrow.

Reductionary accounts of religion

Philosopher

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Andreas von Feuerbach (; 28 July 1804 – 13 September 1872) was a German anthropologist and philosopher, best known for his book ''The Essence of Christianity'', which provided a critique of Christianity that strongly influenced gener ...

and psychoanalyst

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

have argued that God and other religious beliefs are human inventions, created to fulfill various psychological and emotional wants or needs, or a projection mechanism from the 'Id' omnipotence; for

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, in 'Materialism and Empirio-criticism', against the

Russian Machism Russian Machism (//) was a term applied to a variety political/philosophical viewpoints which emerged in Imperial Russia in the beginning of the twentieth century before the Russian Revolution. They shared an interest in the scientific and philosoph ...

, the followers of

Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( , ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was a Moravian-born Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the physics of shock waves. The ratio of one's speed to that of sound is named the Mach ...

, Feuerbach was the final argument against belief in a god. This is also a view of many

Buddhists

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

.

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,["Engels"](_blank)

'' Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (; 1814–1876) was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary ...

, "the idea of God implies the abdication of human reason and justice; it is the most decisive negation of human liberty, and necessarily ends in the enslavement of mankind, in theory, and practice." He reversed

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

's aphorism that if God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him, writing instead that "if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him."

Atheism, religions and spirituality

Atheism is not mutually exclusive with respect to some religious and spiritual belief systems, including

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

,

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

,

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

,

Syntheism

Syntheism is a new religious movement that is focused on how atheists and pantheists can achieve the same feelings of community and awe experienced in traditional theistic religions..

The Syntheist Movement sees itself as the practical realisati ...

,

Raëlism

Raëlism, also known as Raëlianism or Raelian Movement is a UFO religion founded in 1970s France by Claude Vorilhon, now known as Raël. Scholars of religion classify Raëlism as a new religious movement. The group is formalised as the Inte ...

, and

Neopagan

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of North Afric ...

movements

Movement may refer to:

Common uses

* Movement (clockwork), the internal mechanism of a timepiece

* Motion, commonly referred to as movement

Arts, entertainment, and media

Literature

* "Movement" (short story), a short story by Nancy Fu ...

such as

Wicca

Wicca () is a modern Pagan religion. Scholars of religion categorise it as both a new religious movement and as part of the occultist stream of Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was ...

.

schools in

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

hold atheism to be a valid path to

moksha

''Moksha'' (; sa, मोक्ष, '), also called ''vimoksha'', ''vimukti'' and ''mukti'', is a term in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism for various forms of emancipation, enlightenment, liberation, and release. In its soteriology, ...

, but extremely difficult, for the atheist cannot expect any help from

the divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.[divine](_blank) on their journey.

Jainism believes the universe is eternal and has no need for a creator deity, however

Tirthankaras

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English language, English: literally a 'Ford (crossing), ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''Dharma (Jainism), dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the ...

are revered beings who can transcend space and time

and have more power than the god

Indra

Indra (; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is the king of the devas (god-like deities) and Svarga (heaven) in Hindu mythology. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. volumes/ref> I ...

.

Secular Buddhism

Secular Buddhism—sometimes also referred to as agnostic Buddhism, Buddhist agnosticism, ignostic Buddhism, atheistic Buddhism, pragmatic Buddhism, Buddhist atheism, or Buddhist secularism—is a broad term for a form of Buddhism based on hum ...

does not advocate belief in gods. Early Buddhism was atheistic as

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

's path involved no mention of gods.

Later conceptions of Buddhism consider Buddha himself a god, suggest adherents can attain godhood, and revere

Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

s.

Atheism and negative theology

Apophatic theology

Apophatic theology, also known as negative theology, is a form of theology, theological thinking and religious practice which attempts to Problem of religious language, approach God, the Divine, by negation, to speak only in terms of what may no ...

is often assessed as being a version of atheism or agnosticism, since it cannot say truly that God exists. "The comparison is crude, however, for conventional atheism treats the existence of God as a predicate that can be denied ("God is nonexistent"), whereas negative theology denies that God has predicates". "God or the Divine is" without being able to attribute qualities about "what He is" would be the prerequisite of

positive theology

Cataphatic theology or kataphatic theology is theology that uses "positive" terminology to describe or refer to the divine – specifically, God – i.e. terminology that describes or refers to what the divine is believed to be, in cont ...

in negative theology that distinguishes theism from atheism. "Negative theology is a complement to, not the enemy of, positive theology".

Atheistic philosophies

Axiological

Axiology (from Greek , ''axia'': "value, worth"; and , ''-logia'': "study of") is the philosophical study of value. It includes questions about the nature and classification of values and about what kinds of things have value. It is intimately co ...

, or constructive, atheism rejects the existence of gods in favor of a "higher absolute", such as

humanity

Humanity most commonly refers to:

* Humankind the total population of humans

* Humanity (virtue)

Humanity may also refer to:

Literature

* Humanity (journal), ''Humanity'' (journal), an academic journal that focuses on human rights

* ''Humanity: A ...

. This form of atheism favors humanity as the absolute source of ethics and values, and permits individuals to resolve moral problems without resorting to God. Marx and Freud used this argument to convey messages of liberation, full-development, and unfettered happiness.

One of the most common

criticisms of atheism has been to the contrary: that denying the existence of a god either leads to

moral relativism

Moral relativism or ethical relativism (often reformulated as relativist ethics or relativist morality) is used to describe several philosophical positions concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different peoples and cultures. ...

and leaves one with no moral or ethical foundation,

or renders life

meaningless and miserable.

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal ( , , ; ; 19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic Church, Catholic writer.

He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. Pa ...

argued this view in his ''

Pensées

The ''Pensées'' ("Thoughts") is a collection of fragments written by the French 17th-century philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal. Pascal's religious conversion led him into a life of asceticism, and the ''Pensées'' was in many ways his ...

''.

French philosopher

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

identified himself as a representative of an "

atheist existentialism

Atheistic existentialism is a kind of existentialism which strongly diverged from the Christian existentialism, Christian existential works of Søren Kierkegaard and developed within the context of an Atheism, atheistic world view. The philosophi ...

"

concerned less with denying the existence of God than with establishing that "man needs ... to find himself again and to understand that nothing can save him from himself, not even a valid proof of the existence of God."

Sartre said a corollary of his atheism was that "if God does not exist, there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being who exists before he can be defined by any concept, and ... this being is man."

Sartre described the practical consequence of this atheism as meaning that there are no ''a priori'' rules or absolute values that can be invoked to govern human conduct, and that humans are "condemned" to invent these for themselves, making "man" absolutely "responsible for everything he does".

Religion and morality

Joseph Baker and Buster Smith assert that one of the common themes of atheism is that most atheists "typically construe atheism as more moral than religion".

Association with world views and social behaviors

Sociologist

Phil Zuckerman

Philip Joseph Zuckerman (born June 26, 1969) is a professor of sociology and secular studies at Pitzer College in Claremont, California. He specializes in the sociology of substantial secularity. He is the author of several books, including ''Livi ...

analyzed previous social science research on secularity and non-belief and concluded that societal well-being is positively correlated with irreligion. He found that there are much lower concentrations of atheism and secularity in poorer, less developed nations (particularly in Africa and South America) than in the richer industrialized democracies.

His findings relating specifically to atheism in the US were that compared to religious people in the US, "atheists and secular people" are less

nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

,

prejudiced

Prejudice can be an affect (psychology), affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification (disambiguation), classi ...

,

antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

,

racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

,

dogmatic

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Isla ...

,

ethnocentric

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

, closed-minded, and authoritarian, and in US states with the highest percentages of atheists, the murder rate is lower than average. In the most religious states, the murder rate is higher than average.

Irreligion

People who self-identify as atheists are often assumed to be

irreligious

Irreligion or nonreligion is the absence or rejection of religion, or indifference to it. Irreligion takes many forms, ranging from the casual and unaware to full-fledged philosophies such as atheism and agnosticism, secular humanism and ant ...

, but some sects within major religions reject the existence of a personal,

creator deity

A creator deity or creator god (often called the Creator) is a deity responsible for the creation of the Earth, world, and universe in human religion and mythology. In monotheism, the single God is often also the creator. A number of monolatris ...

.

In recent years, certain religious denominations have accumulated a number of openly atheistic followers, such as

atheistic

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

or

humanistic Judaism

Humanistic Judaism ( ''Yahadut Humanistit'') is a Jewish movement that offers a nontheistic alternative to contemporary branches of Judaism. It defines Judaism as the cultural and historical experience of the Jewish people rather than a religio ...

and

Christian atheists. The strictest sense of positive atheism does not entail any specific beliefs outside of disbelief in any deity; as such, atheists can hold any number of spiritual beliefs. For the same reason, atheists can hold a wide variety of ethical beliefs, ranging from the

moral universalism

Moral universalism (also called moral objectivism) is the meta-ethical position that some system of ethics, or a universal ethic, applies universally, that is, for "all similarly situated individuals", regardless of culture, race, sex, religio ...

of

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

, which holds that a moral code should be applied consistently to all humans, to

moral nihilism

Moral nihilism (also known as ethical nihilism) is the meta-ethical view that nothing is morally right or wrong.

Moral nihilism is distinct from moral relativism, which allows for actions to be wrong relative to a particular culture or individ ...

, which holds that morality is meaningless. Atheism is accepted as a valid philosophical position within some varieties of

Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or '' dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global p ...

,

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

, and

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

. Philosophers such as

Alain de Botton

Alain de Botton (; born 20 December 1969) is a Swiss-born British author and philosopher. His books discuss various contemporary subjects and themes, emphasizing philosophy's relevance to everyday life. He published ''Essays in Love'' (1993), w ...

and

Alexander Bard

Alexander Bengt Magnus Bard (born 17 March 1961) is a Swedish musician, author, lecturer, artist, songwriter, music producer, TV personality, religious and political activist, and one of the founders of the Syntheist religious movement alongside ...

and

Jan Söderqvist

Jan Söderqvist (born 1961) is an author, lecturer, writer and consultant, and among other things also working as a literary and film critic for the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet.

Söderqvist has written three books on the Internet revolut ...

, have argued that atheists should reclaim useful components of religion in secular society.

Divine command

According to Plato's

Euthyphro dilemma

The Euthyphro dilemma is found in Plato's dialogue ''Euthyphro'', in which Socrates asks Euthyphro, "Is the pious ( τὸ ὅσιον) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" ( 10a)

Although it ...

, the role of the gods in determining right from wrong is either unnecessary or arbitrary.

The argument that morality must be derived from God, and cannot exist without a wise creator, has been a persistent feature of political if not so much philosophical debate.

[For ]Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemolo ...

, the presupposition of God, soul, and freedom was a practical concern, for "Morality, by itself, constitutes a system, but happiness does not, unless it is distributed in exact proportion to morality. This, however, is possible in an intelligible world only under a wise author and ruler. Reason compels us to admit such a ruler, together with life in such a world, which we must consider as future life, or else all moral laws are to be considered as idle dreams" (''Critique of Pure Reason'', A811).

Moral precepts such as "murder is wrong" are seen as

divine law

Divine law is any body of law that is perceived as deriving from a transcendent source, such as the will of God or godsin contrast to man-made law or to secular law. According to Angelos Chaniotis and Rudolph F. Peters, divine laws are typically ...

s, requiring a divine lawmaker and judge. However, many atheists argue that treating morality legalistically involves a

false analogy

Argument from analogy or false analogy is a special type of inductive argument, whereby perceived similarities are used as a basis to infer some further similarity that has yet to be observed. Analogical reasoning is one of the most common metho ...

, and that morality does not depend on a lawmaker in the same way that laws do.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

believed in a morality independent of theistic belief, and stated that morality based upon God "has truth only if God is truth—it stands or falls with faith in God".

There exist

normative ethical systems that do not require principles and rules to be given by a deity. Some include

virtue ethics

Virtue ethics (also aretaic ethics, from Greek ἀρετή arete_(moral_virtue).html"_;"title="'arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''_is_an_approach_to_ethics_that_treats_the_concept_of_virtue.html" ;"title="arete_(moral_virtue)">aretḗ''.html" ;" ...

,

social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

,

Kantian ethics

Kantian ethics refers to a Deontology, deontological ethical theory developed by Germans, German philosopher Immanuel Kant that is based on the notion that: "It is impossible to think of anything at all in the world, or indeed even beyond it, t ...

,

utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

, and

Objectivism

Objectivism is a philosophical system developed by Russian Americans, Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with prod ...

. Sam Harris has proposed that moral prescription (ethical rule making) is not just an issue to be explored by philosophy, but that we can meaningfully practice a

science of morality

The science of morality may refer to various forms of ethical naturalism grounding morality in rational, empirical consideration of the natural world. It is sometimes framed as using the scientific approach to determine what is right and wrong, i ...

. Any such scientific system must, nevertheless, respond to the criticism embodied in the

naturalistic fallacy

In philosophical ethics, the naturalistic fallacy is the claim that any reductive explanation of good, in terms of natural properties such as ''pleasant'' or ''desirable'', is false. The term was introduced by British philosopher G. E. Moore in hi ...

.

Philosophers

Susan Neiman

Susan Neiman (; born March 27, 1955) is an American moral philosopher, cultural commentator, and essayist. She has written extensively on the juncture between Enlightenment moral philosophy, metaphysics, and politics, both for scholarly audiences ...

and

Julian Baggini

Julian Baggini (; born 1968) is a philosopher, journalist and the author of over 20 books about philosophy written for a general audience. He is co-founder of ''The Philosophers' Magazine'' and has written for numerous international newspapers ...

(among others) assert that behaving ethically only because of a divine mandate is not true ethical behavior but merely blind obedience. Baggini argues that atheism is a superior basis for ethics, claiming that a moral basis external to religious imperatives is necessary to evaluate the morality of the imperatives themselves—to be able to discern, for example, that "thou shalt steal" is immoral even if one's religion instructs it—and that atheists, therefore, have the advantage of being more inclined to make such evaluations.

The contemporary British political philosopher

Martin Cohen has offered the more historically telling example of Biblical injunctions in favor of torture and slavery as evidence of how religious injunctions follow political and social customs, rather than vice versa, but also noted that the same tendency seems to be true of supposedly dispassionate and objective philosophers. Cohen extends this argument in more detail in ''Political Philosophy from Plato to Mao'', where he argues that the

Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

played a role in perpetuating social codes from the early 7th century despite changes in secular society.

Criticism of religion

Some prominent atheists—most recently

Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

,

Daniel Dennett

Daniel Clement Dennett III (born March 28, 1942) is an American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relat ...

,

Sam Harris

Samuel Benjamin Harris (born April 9, 1967) is an American philosopher, neuroscientist, author, and podcast host. His work touches on a range of topics, including rationality, religion, ethics, free will, neuroscience, meditation, psychedelics ...

, and

Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ath ...

, and following such thinkers as

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

,

Robert G. Ingersoll

Robert Green Ingersoll (; August 11, 1833 – July 21, 1899), nicknamed "the Great Agnostic", was an American lawyer, writer, and orator during the Golden Age of Free Thought, who campaigned in defense of agnosticism.

Personal life

Robert Inge ...

,

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

, and novelist

José Saramago

José de Sousa Saramago, GColSE ComSE GColCa (; 16 November 1922 – 18 June 2010), was a Portuguese writer and recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Literature for his "parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony ith which heco ...

—have criticized religions, citing harmful aspects of religious practices and doctrines.

The 19th-century German political theorist and sociologist

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

called religion "the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the

opium of the people

The opium of the people (or opium of the masses) (german: Opium des Volkes) is a dictum used in reference to religion, derived from a frequently paraphrased statement of German sociologist and economic theorist Karl Marx: "Religion is the opium o ...

". He goes on to say, "The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo."

Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

said that "every religious idea and every idea of God is unutterable vileness ... of the most dangerous kind, 'contagion' of the most abominable kind. Millions of sins, filthy deeds, acts of violence and physical contagions ... are far less dangerous than the subtle, spiritual idea of God decked out in the smartest ideological costumes".

[Martin Amis(2003). ''Koba the Dread''; London: Vintage Books; ; pp. 30–31.]

Sam Harris criticizes Western religion's reliance on divine authority as lending itself to

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political '' status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

and

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

tism.

There is a correlation between

religious fundamentalism

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishing ...

and

extrinsic religion (when religion is held because it serves ulterior interests)

and authoritarianism, dogmatism, and prejudice.

These arguments—combined with historical events that are argued to demonstrate the dangers of religion, such as the

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

,

inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

s,

witch trials

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern per ...

, and

terrorist attacks

The following is a list of terrorist incidents that have not been carried out by a state or its forces (see state terrorism and state-sponsored terrorism). Assassinations are listed at List of assassinated people.

Definitions of terrori ...

—have been used in response to claims of beneficial effects of belief in religion.

Believers counter-argue that some

regimes that espouse atheism, such as the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, have also been guilty of mass murder.

In response to those claims, atheists such as Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins have stated that Stalin's atrocities were influenced not by atheism but by dogmatic

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, and that while Stalin and Mao happened to be atheists, they did not do their deeds in the name of atheism.

History

While the earliest-found usage of the term ''atheism'' is in 16th-century

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

ideas that would be recognized today as atheistic are documented from the

Vedic period

The Vedic period, or the Vedic age (), is the period in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age of the history of India when the Vedic literature, including the Vedas (ca. 1300–900 BCE), was composed in the northern Indian subcontinent, betw ...

and the

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

.

Early Indian religions

Atheistic schools are found in early Indian thought and have existed from the times of the

historical Vedic religion

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

.

Among the six

orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

schools of Hindu philosophy,

Samkhya

''Samkhya'' or ''Sankya'' (; Sanskrit सांख्य), IAST: ') is a Dualism (Indian philosophy), dualistic Āstika and nāstika, school of Indian philosophy. It views reality as composed of two independent principles, ''purusha, puruṣa' ...

, the oldest philosophical school of thought, does not accept God, and the early

Mimamsa also rejected the notion of God.

The thoroughly materialistic and anti-theistic philosophical

Cārvāka

Charvaka ( sa, चार्वाक; IAST: ''Cārvāka''), also known as ''Lokāyata'', is an ancient school of Indian materialism. Charvaka holds direct perception, empiricism, and conditional inference as proper sources of knowledge, embrace ...

(or ''Lokāyata'') school that originated in

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

around the 6th century BCE is probably the most explicitly atheistic school of philosophy in India, similar to the Greek

Cyrenaic school

The Cyrenaics or Kyrenaics ( grc, Κυρηναϊκοί, Kyrēnaïkoí), were a sensual hedonist Greek school of philosophy founded in the 4th century BCE, supposedly by Aristippus of Cyrene, although many of the principles of the school are belie ...

. This branch of Indian philosophy is classified as

heterodox

In religion, heterodoxy (from Ancient Greek: , "other, another, different" + , "popular belief") means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". Under this definition, heterodoxy is similar to unorthodoxy, w ...

due to its rejection of the authority of

Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

and hence is not considered part of the six orthodox schools of

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Veda ...

. It is noteworthy as evidence of a materialistic movement in ancient India.

Chatterjee and Datta explain that our understanding of Cārvāka philosophy is fragmentary, based largely on criticism of the ideas by other schools, and that it is not a living tradition:

Other Indian philosophies generally regarded as atheistic include

Classical Samkhya and

Purva Mimamsa

The Fourteen Purva translated as ancient or prior knowledge, are a large body of Jain scriptures that was preached by all Tirthankaras (omniscient teachers) of Jainism encompassing the entire gamut of knowledge available in this universe. The pers ...

. The rejection of a personal creator "God" is also seen in

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current ...

and

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

in India.

Classical antiquity

Western atheism has its roots in

pre-Socratic