Australian Inventions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a timeline of Australian inventions consisting of products and technology invented in Australia from pre-European-settlement in 1788 to the present. The inventions are listed in chronological order based on the date of their introduction.

Australian inventions include the very old, such as woomera, and the very new, such as the

This is a timeline of Australian inventions consisting of products and technology invented in Australia from pre-European-settlement in 1788 to the present. The inventions are listed in chronological order based on the date of their introduction.

Australian inventions include the very old, such as woomera, and the very new, such as the  Many of Australia's inventions were realised by individuals who get little credit or who are often overlooked for more famous Americans or Europeans.

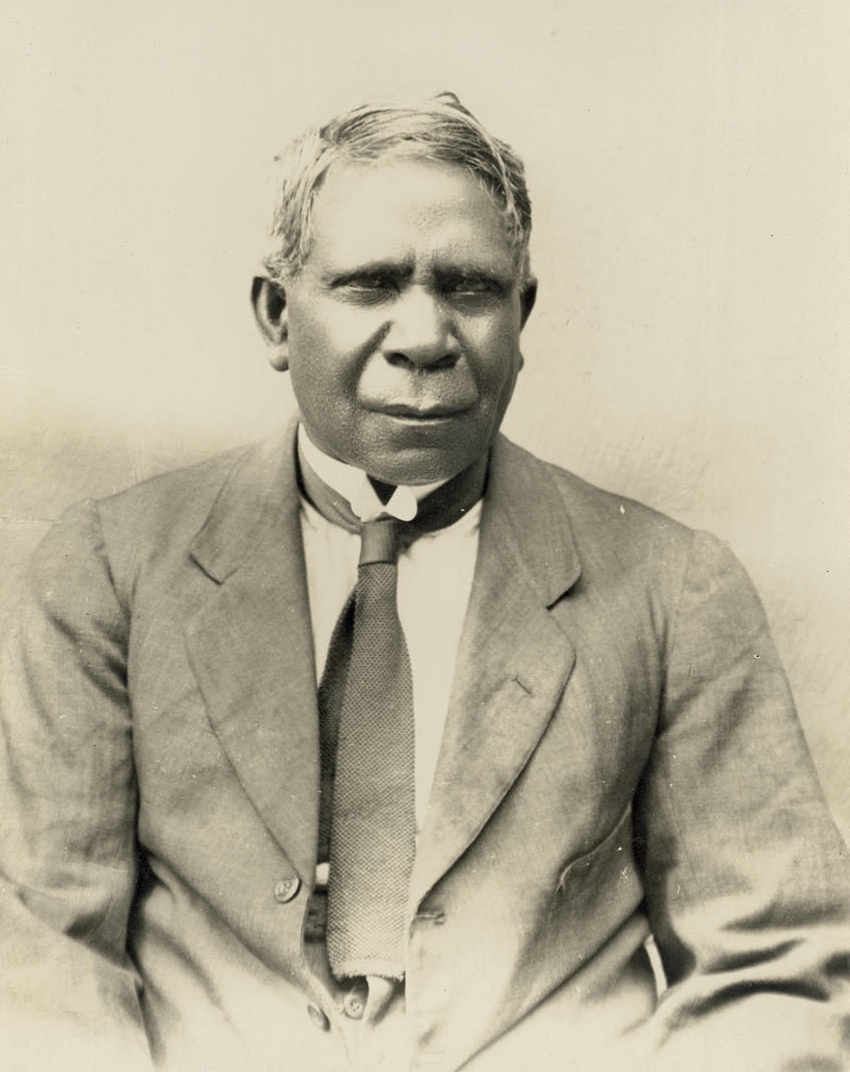

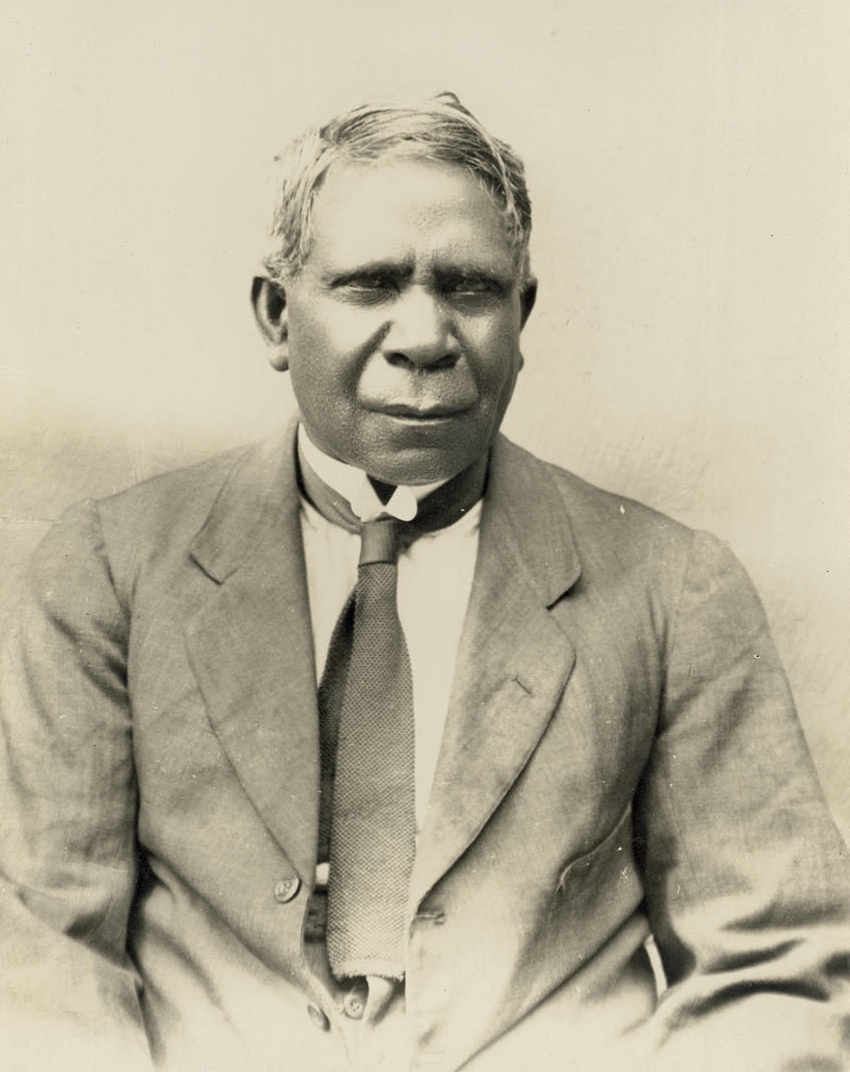

Australian-Aboriginal man David Unaipon is known as "Australia's Leonardo" for his contributions to science and the

Many of Australia's inventions were realised by individuals who get little credit or who are often overlooked for more famous Americans or Europeans.

Australian-Aboriginal man David Unaipon is known as "Australia's Leonardo" for his contributions to science and the

1858 – Australian rules football – began its development when

1858 – Australian rules football – began its development when  1892 – Coolgardie safe – Arthur Patrick McCormick noticed that a wet bag placed over a bottle cooled its contents, and the cooling was more pronounced in a breeze. The Coolgardie safe was a box made of wire and hessian sitting in water, which was placed on a verandah so that any breeze would evaporate the water in the hessian and via the principle of evaporation, cool the air inside the box. The Coolgardie safe was used into the middle of the 20th century as a means of preserving food.

1893 –

1892 – Coolgardie safe – Arthur Patrick McCormick noticed that a wet bag placed over a bottle cooled its contents, and the cooling was more pronounced in a breeze. The Coolgardie safe was a box made of wire and hessian sitting in water, which was placed on a verandah so that any breeze would evaporate the water in the hessian and via the principle of evaporation, cool the air inside the box. The Coolgardie safe was used into the middle of the 20th century as a means of preserving food.

1893 –

1906 –

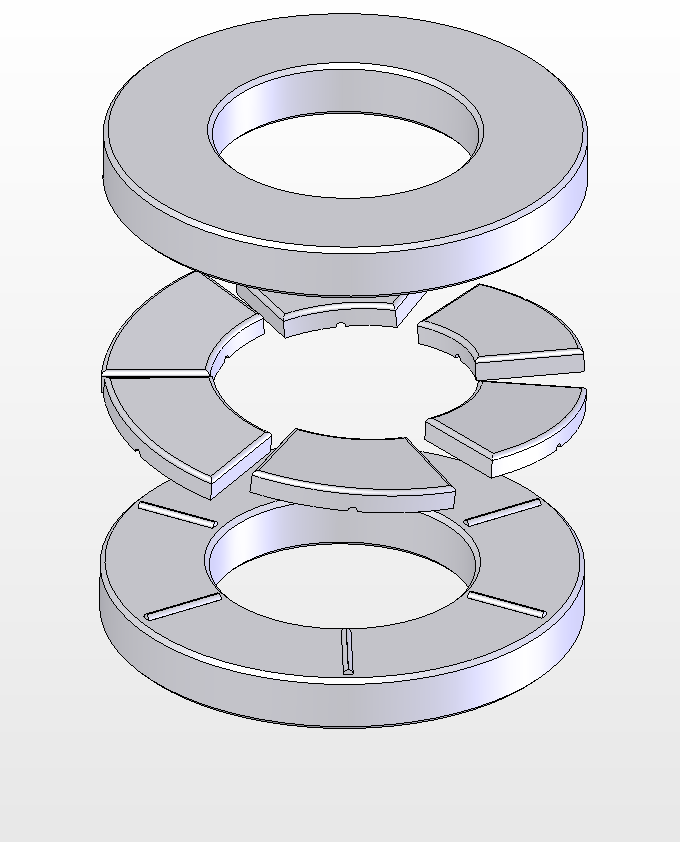

1906 –  1907 – Michell thrust block bearing – Fluid-film thrust bearings were invented by Australian engineer George Michell. Michell bearings contain a number of sector-shaped pads, arranged in a circle around the shaft, and that are free to tilt. These create wedge-shaped regions of oil inside the bearing between the pads and a rotating disk, which support the applied thrust and eliminate metal-on-metal contact. The small size (one-tenth the size of old bearing designs), low friction and long life of Michell's invention made possible the development of larger propellers and engines in ships. They were used extensively in ships built during

1907 – Michell thrust block bearing – Fluid-film thrust bearings were invented by Australian engineer George Michell. Michell bearings contain a number of sector-shaped pads, arranged in a circle around the shaft, and that are free to tilt. These create wedge-shaped regions of oil inside the bearing between the pads and a rotating disk, which support the applied thrust and eliminate metal-on-metal contact. The small size (one-tenth the size of old bearing designs), low friction and long life of Michell's invention made possible the development of larger propellers and engines in ships. They were used extensively in ships built during  1910 – Dethridge wheel – The wheel, used to measure the water flow in an irrigation channel, consisting of a drum on an axle, with eight v-shaped vanes fixed to its outside, was invented by John Dethridge, Commissioner of the Victorian State Rivers and Water Supply Commission.

1910 – Dethridge wheel – The wheel, used to measure the water flow in an irrigation channel, consisting of a drum on an axle, with eight v-shaped vanes fixed to its outside, was invented by John Dethridge, Commissioner of the Victorian State Rivers and Water Supply Commission.

1912 –

1912 –  1930 –

1930 –  1934 –

1934 –  1943 – Splayd – The combination of knife, fork and spoon was invented by William McArthur after seeing ladies struggle to eat at barbecues with standard cutlery from plates on their laps.

1943 – Splayd – The combination of knife, fork and spoon was invented by William McArthur after seeing ladies struggle to eat at barbecues with standard cutlery from plates on their laps.

1952 – Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer – The atomic absorption spectrophotometer is used in chemical analysis to determine low concentrations of metals in gases or vaporized solutions. It was developed by Sir Alan Walsh of the CSIRO using ionization lamps specific to the metal being detected.

1953 –

1952 – Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer – The atomic absorption spectrophotometer is used in chemical analysis to determine low concentrations of metals in gases or vaporized solutions. It was developed by Sir Alan Walsh of the CSIRO using ionization lamps specific to the metal being detected.

1953 –  1958 –

1958 –  1965 – Wine cask – Invented by Thomas Angove of Renmark, South Australia, the wine cask is a cardboard box housing a plastic container which collapses as the wine is drawn off, thus preventing contact with the air. Angroves' original design with a resealable spout was replaced with a tap by the Penfolds wine company in 1972

1970 – Staysharp knife – The self-sharpening knife was developed by Wiltshire.

1971 – Variable

1965 – Wine cask – Invented by Thomas Angove of Renmark, South Australia, the wine cask is a cardboard box housing a plastic container which collapses as the wine is drawn off, thus preventing contact with the air. Angroves' original design with a resealable spout was replaced with a tap by the Penfolds wine company in 1972

1970 – Staysharp knife – The self-sharpening knife was developed by Wiltshire.

1971 – Variable  1972 – Power board – Peter Talbot, working under Frank Bannigan at

1972 – Power board – Peter Talbot, working under Frank Bannigan at  1979 –

1979 –  1979 –

1979 –  1983 – Winged Keel – Ben Lexcen designed a winged keel that helped

1983 – Winged Keel – Ben Lexcen designed a winged keel that helped

2002 –

2002 –

This is a timeline of Australian inventions consisting of products and technology invented in Australia from pre-European-settlement in 1788 to the present. The inventions are listed in chronological order based on the date of their introduction.

Australian inventions include the very old, such as woomera, and the very new, such as the

This is a timeline of Australian inventions consisting of products and technology invented in Australia from pre-European-settlement in 1788 to the present. The inventions are listed in chronological order based on the date of their introduction.

Australian inventions include the very old, such as woomera, and the very new, such as the scramjet

A scramjet (supersonic combustion ramjet) is a variant of a ramjet airbreathing jet engine in which combustion takes place in supersonic airflow. As in ramjets, a scramjet relies on high vehicle speed to compress the incoming air forceful ...

, first fired at the Woomera rocket range. The Australian government has suggested that Australian inventiveness springs from the nation's geography and isolation. Perhaps due to its status as an island continent connected to the rest of the world only via air and sea, Australians have been leaders in inventions relating to both maritime and aeronautical matters, including powered flight

A powered aircraft is an aircraft that uses onboard propulsion with mechanical power generated by an aircraft engine of some kind.

Aircraft propulsion nearly always uses either a type of propeller, or a form of jet propulsion. Other potential ...

, the black box

In science, computing, and engineering, a black box is a system which can be viewed in terms of its inputs and outputs (or transfer characteristics), without any knowledge of its internal workings. Its implementation is "opaque" (black). The te ...

flight recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has ...

, the inflatable escape slide, the surf ski

A surfski (or: "surf ski", "surf-ski") is a type of kayak in the kayaking "family" of paddling craft. It is generally the longest of all kayaks and is a performance oriented kayak designed for speed on open water, most commonly the ocean, althoug ...

and the wave-piercing

A wave-piercing boat hull has a very fine bow, with reduced buoyancy in the forward portions. When a wave is encountered, the lack of buoyancy means the hull pierces through the water rather than riding over the top, resulting in a smoother rid ...

catamaran winged keel

The winged keel is a sailboat keel layout first fitted on the 12-metre class yacht '' Australia II'', 1983 America's Cup winner.

Design

This layout was adopted by Ben Lexcen, designer of '' Australia II''. Although Ben Lexcen "had tried the wing ...

. Since the earliest days of European settlement, Australia's main industries have been agriculture and mining. As a result of this, Australians have made many inventions in these areas, including the grain stripper, the stump jump plough

The stump-jump plough, also known as stump-jumping plough, is a kind of plough invented in South Australia in the late 19th century by Richard Bowyer Smith and Clarence Herbert Smith to solve the particular problem of preparing mallee lands for ...

, mechanical sheep shears, the Dethridge water wheel, the froth flotation

Froth flotation is a process for selectively separating hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic. This is used in mineral processing, paper recycling and waste-water treatment industries. Historically this was first used in the mining industry, wh ...

ore separation process, the instream ore analysis process and the buffalo fly trap.

Australian inventions also include a number of weapons or weapons systems, including the woomera, the tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful e ...

, and the underwater torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

. In recent years, Australians have been at the forefront of medical technology with inventions including ultrasound

Ultrasound is sound waves with frequencies higher than the upper audible limit of human hearing. Ultrasound is not different from "normal" (audible) sound in its physical properties, except that humans cannot hear it. This limit varies fr ...

, the bionic ear

A cochlear implant (CI) is a surgically implanted neuroprosthesis that provides a person who has moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss with sound perception. With the help of therapy, cochlear implants may allow for improved speech unde ...

, the first plastic spectacle lenses, the electronic pacemaker

An artificial cardiac pacemaker (or artificial pacemaker, so as not to be confused with the natural cardiac pacemaker) or pacemaker is a medical device that generates electrical impulses delivered by electrodes to the chambers of the heart ei ...

, the multi-focal contact lens, spray-on artificial skin and anti-flu medication. Australians also developed a number of useful household items, including Vegemite

Vegemite ( ) is a thick, dark brown Australian food spread made from leftover brewers' yeast extract with various vegetable and spice additives. It was developed by Cyril Callister in Melbourne, Victoria, in 1922.

A spread for sandwiche ...

, and the process for producing permanently creased fabric.

Many of Australia's inventions were realised by individuals who get little credit or who are often overlooked for more famous Americans or Europeans.

Australian-Aboriginal man David Unaipon is known as "Australia's Leonardo" for his contributions to science and the

Many of Australia's inventions were realised by individuals who get little credit or who are often overlooked for more famous Americans or Europeans.

Australian-Aboriginal man David Unaipon is known as "Australia's Leonardo" for his contributions to science and the Aboriginal people

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. His inventions include a tool for sheep-shearing, a centrifugal motor, a multi-radial wheel and mechanical propulsion device. Unaipon appears on Australia's $50 note.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency responsible for scientific research.

CSIRO works with leading organisations around the world. From its headquarters in Canberra, CSIRO ...

(CSIRO) is an Australian-government-funded institution. A number of CSIRO funded scientists and engineers are featured in this list. CSIRO scientists lead Australian research across a number of different fields, and work with industry and government to solve problems such as using insects to tackle weeds, growing more sustainable crops and improving transportation.

Aboriginal technology – before 1788

Didgeridoo

The didgeridoo (; also spelt didjeridu, among other variants) is a wind instrument, played with vibrating lips to produce a continuous drone while using a special breathing technique called circular breathing. The didgeridoo was developed by ...

– The didgeridoo is a wind instrument of northern Australia. It is sometimes described as a "drone

Drone most commonly refers to:

* Drone (bee), a male bee, from an unfertilized egg

* Unmanned aerial vehicle

* Unmanned surface vehicle, watercraft

* Unmanned underwater vehicle or underwater drone

Drone, drones or The Drones may also refer to:

...

pipe," but musicologist

Musicology (from Greek μουσική ''mousikē'' 'music' and -λογια ''-logia'', 'domain of study') is the scholarly analysis and research-based study of music. Musicology departments traditionally belong to the humanities, although some m ...

s classify it as an aerophone

An aerophone () is a musical instrument that produces sound primarily by causing a body of air to vibrate, without the use of strings or membranes (which are respectively chordophones and membranophones), and without the vibration of the instru ...

. Traditionally, a didgeridoo was made by selecting a section of a Eucalyptus branch, then burying it near a termite mound so that the termites would hollow it out, to produce a long, hollow piece of wood suitable for fashioning the instrument.

Woomera – The woomera is a type of spear thrower, adding thrust to a spear as part of a throwing action.

Colonial era – 19th century

1843 – Grain stripper – John Wrathall Bull invented and John Ridley manufactured inSouth Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

the world's first mechanised grain stripper. It utilised a comb to lift the ears of the crop to where revolving beaters deposited the grain into a bin.

1856 – Refrigerator – Using the principle of vapour compression, James Harrison produced the world's first practical ice making machine and refrigerator.

1856 - Secret Ballot voting invented by Henry Chapman and first used in the Victorian election on 23 September 1856. Voters had their names marked off on the electoral roll at the polling place, were presented with a printed ballot paper, and retired to separate compartments to mark their ballot paper in secrecy before depositing it in a locked box watched over by the presiding officer, poll clerks and scrutineers.

1858 – Australian rules football – began its development when

1858 – Australian rules football – began its development when Tom Wills

Thomas Wentworth Wills (19 August 1835 – 2 May 1880) was an Australian sportsman who is credited with being Australia's first cricketer of significance and a founder of Australian rules football. Born in the British penal colony of Ne ...

wrote a letter published in ''Bell's Life in Victoria & Sporting Chronicle'' on 10 July 1858, calling for a "foot-ball club, a rifle club, or other athletic pursuits" to keep cricketers fit during winter. An experimental match was played by Wills and others at the Richmond Paddock, later known as Yarra Park

Yarra Park (35.469 hectares) is part of the Melbourne Sports and Entertainment Precinct, the premier sporting precinct of Victoria, Australia. Located in Yarra Park is the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) and numerous sporting fields and ovals, i ...

next to the Melbourne Cricket Ground

The Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG), also known locally as "The 'G", is an Australian sports stadium located in Yarra Park, Melbourne, Victoria. Founded and managed by the Melbourne Cricket Club, it is the largest stadium in the Southern Hem ...

on 31 July 1858.

The Melbourne Football Club rules of 1859 are the oldest surviving set of laws for Australian football. They were drawn up at the Parade Hotel, East Melbourne

East Melbourne is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, east of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Melbourne local government area. East Melbourne recorded a population of 4,896 at the 2021 ...

, on 17 May, by Wills, W. J. Hammersley, J. B. Thompson and Thomas Smith.

The Melbourne club's game was not immediately adopted by neighbouring clubs. Before each match the rules had to be agreed by the two teams involved. By 1866, several other clubs had agreed to play by an updated version of Melbourne's rules.

1859 – Photolithography

In integrated circuit manufacturing, photolithography or optical lithography is a general term used for techniques that use light to produce minutely patterned thin films of suitable materials over a substrate, such as a silicon wafer (electroni ...

– developed by John Walter Osborne at the Victorian government's Crown Lands Office. During a land boom the Office had trouble producing the many maps and documents required to keep land records updated. Instead of having to copy surveyor's originals, or having to store stone originals, master copies saved were glass slides of around square.Jean Gittins, 'Osborne, John Walter (1828–1902)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/osborne-john-walter-4343/text7051, published first in hardcopy 1974, accessed online 26 June 2016.

1868 - Granny Smith

The Granny Smith, also known as a green apple or sour apple, is an apple cultivar which originated in Australia in 1868. It is named after Maria Ann Smith, who propagated the cultivar from a chance seedling. The tree is thought to be a hybrid ...

Apple - Propagated by Maria Ann Smith in Eastwood, New South Wales

1874 – Underwater torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

– Invented by Louis Brennan, the torpedo had two propellers, rotated by wires which were attached to winding engines on the shore station. By varying the speed at which the two wires were extracted, the torpedo could be steered to the left or right by an operator on the shore.

1876 – Stump jump plough

The stump-jump plough, also known as stump-jumping plough, is a kind of plough invented in South Australia in the late 19th century by Richard Bowyer Smith and Clarence Herbert Smith to solve the particular problem of preparing mallee lands for ...

– Richard and Clarence Bowyer Smith developed a plough which could jump over stumps and stones, enabling newly cleared land to be cultivated.

1877 – Mechanical clippers – Various mechanical shearing patents were registered in Australia before Frederick York Wolseley finally succeeded in developing a practical hand piece with a comb and reciprocating cutter driven by power transmitted from a stationary engine.

1889 – Electric drill – Arthur James Arnot patented the world's first electric drill on 20 August 1889 while working for the Union Electric Company in Melbourne. He designed it primarily to drill rock and to dig coal.

1892 – Coolgardie safe – Arthur Patrick McCormick noticed that a wet bag placed over a bottle cooled its contents, and the cooling was more pronounced in a breeze. The Coolgardie safe was a box made of wire and hessian sitting in water, which was placed on a verandah so that any breeze would evaporate the water in the hessian and via the principle of evaporation, cool the air inside the box. The Coolgardie safe was used into the middle of the 20th century as a means of preserving food.

1893 –

1892 – Coolgardie safe – Arthur Patrick McCormick noticed that a wet bag placed over a bottle cooled its contents, and the cooling was more pronounced in a breeze. The Coolgardie safe was a box made of wire and hessian sitting in water, which was placed on a verandah so that any breeze would evaporate the water in the hessian and via the principle of evaporation, cool the air inside the box. The Coolgardie safe was used into the middle of the 20th century as a means of preserving food.

1893 – Box kite

A box kite is a high performance kite, noted for developing relatively high lift; it is a type within the family of cellular kites. The typical design has four parallel struts. The box is made rigid with diagonal crossed struts. There are two s ...

– Invented by Lawrence Hargrave

Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS, (29 January 18506 July 1915) was a British-born Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer.

Biography

Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England, the second son of John Flet ...

, the box kite is a high performance kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. ...

, noted for developing relatively high lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

; it was used as part of his attempt to develop a manned flying machine. Having added a seat to four connected box kites, he flew with the kites 16 feet (4.8 metres) off the ground, proving to the world that it was possible to build a safe, heavier-than-air flying machine. Hargrave’s designs were quickly taken up by other inventors, including the American Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute (February 18, 1832 – November 23, 1910) was a French-American civil engineer and aviation pioneer. He provided many budding enthusiasts, including the Wright brothers, with help and advice, and helped to publicize their flying ...

with whom he was corresponding, and whose designs were later incorporated by the Wright brothers into their Wright Flyer

The ''Wright Flyer'' (also known as the ''Kitty Hawk'', ''Flyer'' I or the 1903 ''Flyer'') made the first sustained flight by a manned heavier-than-air powered and controlled aircraft—an airplane—on December 17, 1903. Invented and flown ...

, the first aircraft to achieve powered flight

A powered aircraft is an aircraft that uses onboard propulsion with mechanical power generated by an aircraft engine of some kind.

Aircraft propulsion nearly always uses either a type of propeller, or a form of jet propulsion. Other potential ...

with a pilot on board in December 1903.

20th century Post-Federation – 1901–1945

1902 –Notepad

A notebook (also known as a notepad, writing pad, drawing pad, or legal pad) is a book or stack of paper pages that are often ruled and used for purposes such as note-taking, journaling or other writing, drawing, or scrapbooking.

History

...

– For 500 years, paper had been supplied in loose sheets. Launceston stationer J. A. Birchall decided that it would be a good idea to cut the sheets in half, back them with cardboard and glue them together at the top.

1903 – Froth flotation

Froth flotation is a process for selectively separating hydrophobic materials from hydrophilic. This is used in mineral processing, paper recycling and waste-water treatment industries. Historically this was first used in the mining industry, wh ...

– The process of separating minerals from rock by flotation was developed by Charles Potter and Guillaume Delprat

Guillaume Daniel Delprat CBE (1 September 1856 – 15 March 1937) was a Dutch-Australian metallurgist, mining engineer, and businessman. He was a developer of the froth flotation process for separating minerals.

Delprat was born in Delft, ...

in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. Both worked independently at the same time on different parts of the process for the mining company BHP

1906 –

1906 – Feature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

– The world's first feature-length film, '' The Story of the Kelly Gang'', was a little over one hour long.

1906 – Surf life-saving reel – The first surf life-saving reel in the world was demonstrated at Bondi Beach

Bondi Beach is a popular beach and the name of the surrounding suburb in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Bondi Beach is located east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of Waverley Council, in the Eas ...

on 23 December 1906 by its designer, surfer Lester Ormsby.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and have become the standard bearing used on turbine shafts in ships and power plants worldwide.

1910 – Humespun pipe-making process – The Humespun process was developed by Walter Hume of Humes Ltd for making concrete pipes of high strength and low permeability. The process used centrifugal force to evenly distribute concrete onto wire reinforcing, revolutionising pipe manufacture.

1910 – Dethridge wheel – The wheel, used to measure the water flow in an irrigation channel, consisting of a drum on an axle, with eight v-shaped vanes fixed to its outside, was invented by John Dethridge, Commissioner of the Victorian State Rivers and Water Supply Commission.

1910 – Dethridge wheel – The wheel, used to measure the water flow in an irrigation channel, consisting of a drum on an axle, with eight v-shaped vanes fixed to its outside, was invented by John Dethridge, Commissioner of the Victorian State Rivers and Water Supply Commission.

1912 –

1912 – Surf ski

A surfski (or: "surf ski", "surf-ski") is a type of kayak in the kayaking "family" of paddling craft. It is generally the longest of all kayaks and is a performance oriented kayak designed for speed on open water, most commonly the ocean, althoug ...

– Harry McLaren and his brother Jack used an early version of the surf ski for use around the family's oyster beds on Lake Innes, near Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie is a coastal town in the local government area of Port Macquarie-Hastings. It is located on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia, about north of Sydney, and south of Brisbane. The town is located on the Tasman Sea ...

, and the brothers used them in the surf on Port Macquarie's beaches. The board was propelled in a sitting position with two small hand blades, which was probably not a highly efficient method to negotiate the surf. The deck is flat with a bung plug at the rear and a nose ring with a leash, possibly originally required for mooring. The rails are square and there is pronounced rocker. The boards' obvious buoyancy indicates hollow construction, with thin boards of cedar fixed longitudinally down the board.

1912 – Tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful e ...

– South Australian Lance de Mole submitted a proposal to the British War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence (MoD ...

, for a 'chain-rail vehicle which could be easily steered and carry heavy loads over rough ground and trenches,' complete with extensive drawings. The British war office rejected the idea at the time, but De Mole made several more proposals to the British War Office in 1914 and 1916, and formally requested he be recognised as the inventor of the Mark I tank

British heavy tanks were a series of related armoured fighting vehicles developed by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, UK during the First World War. The Mark I was the world's first tank, a tracked, armed, and armoured vehicle, ...

. The British Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors eventually made a payment of £987 to De Mole to cover his expenses and promoted him to an honorary corporal.

1912 – Self-Propelled Rotary Hoe

A cultivator is a piece of agricultural equipment used for secondary tillage. One sense of the name refers to frames with ''teeth'' (also called ''shanks'') that pierce the soil as they are dragged through it linearly. It also refers to mac ...

– At the age of 16 Cliff Howard of Gilgandra invented a machine with rotating hoe blades on an axle that simultaneously hoed the ground and pulled the machine forward.

1913 – Automatic totalisator

A tote board (or totalisator/totalizator) is a numeric or alphanumeric display used to convey information, typically at a race track (to display the odds or payoffs for each horse) or at a telethon (to display the total amount donated to the char ...

– The world's first automatic totalisator for calculating horse-racing bets was made by Sir George Julius

Sir George Alfred Julius (29 April 187328 June 1946) was an English-born Australian inventor and entrepreneur. He was the founder of Julius Poole & Gibson Pty Ltd and Automatic Totalisators Ltd, and invented the world's first automatic totalis ...

.

1915 – Periscope rifle

A periscope rifle is a rifle that has been adapted to enable it to be sighted by the use of a periscope. This enables the shooter to remain concealed below cover. The device was independently invented by a number of individuals in response to the t ...

– A periscope rifle is a rifle that has been adapted to enable it to be sighted by the use of a periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

, it was invented by Lance-Corporal W C Beech at Gallipoli. The device allowed a soldier to aim and fire a rifle from a trench

A trench is a type of excavation or in the ground that is generally deeper than it is wide (as opposed to a wider gully, or ditch), and narrow compared with its length (as opposed to a simple hole or pit).

In geology, trenches result from ero ...

, without being exposed to enemy fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition ...

. Beech modified a standard Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield or Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed repeating rifle that served as the main firearm of the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century, and was the British Army's s ...

.303 .303 may refer to:

* .303 British, a rifle cartridge

* .303 Savage, a rifle cartridge

* Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield or Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed repeating rifle that served as the main firearm of the military forces of the B ...

rifle by cutting the stock in half. The two halves were re-connected with a board and mirror periscope

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with ...

, horizontally aligned to the sights of the rifle, as well as a string to pull the trigger, which allowed the rifle to be fired from beneath the line of fire.

1917 – Aspro – Aspro was invented by the chemist George Nicholas as a form of aspirin in a tablet.

1919 – Non-perishable Anthrax vaccine – Metallurgist

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sci ...

and bacteriologist

A bacteriologist is a microbiologist, or similarly trained professional, in bacteriology -- a subdivision of microbiology that studies bacteria, typically pathogenic ones. Bacteriologists are interested in studying and learning about bacteria, as ...

John McGarvie Smith

John McGarvie Smith (8 February 1844 – 6 September 1918) was an Australian metallurgist, bacteriologist and benefactor.

Biography

Smith was born in Sydney, the eldest surviving of thirteen children of Scots parents David Milne Smith, tail ...

after long experimenting found an effective Anthrax vaccine which would keep for an indefinite period. Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named after ...

had originally discovered a vaccine, which, however, would not keep.

1920 – Crankless engine– Engines that eliminated the need for a crankshaft found in most automotive and stationary engines was invented by Anthony Michell

Anthony George Maldon Michell FRS (21 June 1870 – 17 February 1959) was an Australian mechanical engineer of the early 20th century.

Early life

Michell was born in London while his parents were on a visit to England from Australia to which th ...

. The engines did not require connecting rod

A connecting rod, also called a 'con rod', is the part of a piston engine which connects the piston to the crankshaft. Together with the crank, the connecting rod converts the reciprocating motion of the piston into the rotation of the cranksha ...

and bearings found in most engines and as such could be lighter and more compact.

1924 – Car radio – The first car radio was fitted to an Australian car built by Kellys Motors in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

1924 – Stobie pole

A Stobie pole is a power line pole made of two steel joists held apart by a slab of concrete. It was invented by Adelaide Electric Supply Company engineer James Cyril Stobie (1895–1953). Stobie used readily available materials due to the ...

– A power line pole made of two steel joists held apart by a slab of concrete. It was invented by Adelaide Electric Supply Company engineer James Cyril Stobie.

1925 – Record changer – Invented by Eric Waterworth, a record changer (also called an autochanger) is a device that plays several phonograph records in sequence without user intervention. Record changers were common until the 1980s.

1927 – The Pedal Wireless – A pedal-operated two-way radio

A two-way radio is a radio that can both transmit and receive radio waves (a transceiver), unlike a radio broadcasting, broadcast receiver which only receives content. It is an audio (sound) transceiver, a transmitter and radio receiver, receive ...

invented by Alfred_Traeger.

1928 – Electronic Pacemaker

An artificial cardiac pacemaker (or artificial pacemaker, so as not to be confused with the natural cardiac pacemaker) or pacemaker is a medical device that generates electrical impulses delivered by electrodes to the chambers of the heart ei ...

– Developed by Edgar H Booth and Mark C Liddell, the heart pacemaker had a portable apparatus which 'plugged into a lighting point. One pole was applied to a skin pad soaked in strong salt solution' while the other pole 'consisted of a needle insulated except at its point, and was plunged into the appropriate cardiac chamber'. 'The pacemaker rate was not good from about 80 to 120 pulses per minute, and likewise the voltage variable from 1.5 to 120 volts.' The apparatus was used to revive a potentially stillborn infant at Crown Street Women's Hospital, Sydney whose heart continued 'to beat on its own accord', 'at the end of 10 minutes' of stimulation.

1929 – Starting blocks

Starting blocks are a device used in the sport of track and field by sprint athletes to brace their feet against at the start of a race so they do not slip as they stride forward at the sound of the starter's pistol. The blocks also enable the sp ...

– Athlete Charlie Booth and his father are credited with the invention of the starting block. Starting blocks are a device used in the sport of track and field

Track and field is a sport that includes athletic contests based on running, jumping, and throwing skills. The name is derived from where the sport takes place, a running track and a grass field for the throwing and some of the jumping eve ...

by sprint

Sprint may refer to:

Aerospace

*Spring WS202 Sprint, a Canadian aircraft design

*Sprint (missile), an anti-ballistic missile

Automotive and motorcycle

*Alfa Romeo Sprint, automobile produced by Alfa Romeo between 1976 and 1989

*Chevrolet Sprint, ...

athletes to brace their feet against at the start of a race so they do not slip as they stride forward at the sound of the starter's pistol

A starting pistol or starter pistol is a blank handgun that is fired to start track and field races, as well as competitive swimming races at some meets. Starter guns cannot fire real ammunition without first being extensively modified: Blank ...

. The blocks also enable the sprinters to adopt a more efficient starting posture and isometrically preload their muscles in an enhanced manner. This allows them to start more powerfully and increases their overall sprint speed capability. For most levels of competition, including the whole of high-level international competition, starting blocks are now mandatory equipment for the start of sprint races. IAAF Rule 161

1930 – Letter Sorting Machine – ( Sydney's General Post Office (GPO)) was the site for the first mechanised letter sorter which was developed by an engineer with the Postmaster-General's Department

The Postmaster-General's Department (PMG) was a department of the Australian federal government, established at Federation in 1901, whose responsibilities included the provision of postal and telegraphic services throughout Australia. It was ...

.

1930 –

1930 – Clapperboard

A clapperboard (also known by various other names including dumb slate) is a device used in filmmaking and video production to assist in synchronizing of picture and sound, and to designate and mark the various scenes and takes as they are f ...

– The wooden marker used to synchronise sound and film was invented by Frank Thring Sr of Efftee Studios in Melbourne.

1932 – Sunscreen

Sunscreen, also known as sunblock or sun cream, is a photoprotective topical product for the skin that mainly absorbs, or to a much lesser extent reflects, some of the sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation and thus helps protect against sunbu ...

–

1934 –

1934 – Coupé utility

A coupé utility is a vehicle with a passenger compartment at the front and an integrated cargo tray at the rear, with the front of the cargo bed doubling as the rear of the passenger compartment.

The term originated in the 1930s, where it wa ...

– The car body style, known colloquially as the ute in Australia and New Zealand, combines a two-door "coupé" cabin with an integral cargo bed behind the cabin—using a light-duty passenger vehicle-derived platform. It was designed by Lewis Bandt at Ford Australia

Ford Motor Company of Australia Limited (known by its trading name Ford Australia) is the Australian subsidiary of United States-based automaker Ford Motor Company. It was founded in Geelong, Victoria, in 1925 as an outpost of Ford Motor Comp ...

in Geelong

Geelong ( ) ( Wathawurrung: ''Djilang''/''Djalang'') is a port city in the south eastern Australian state of Victoria, located at the eastern end of Corio Bay (the smaller western portion of Port Phillip Bay) and the left bank of Barwon ...

, Victoria. The first ute rolled off the Ford production lines in 1934. The idea came from a Geelong farmer's wife who wrote to Ford in 1933 advising the need for a new sort of vehicle to take her 'to church on Sundays and pigs to market on Mondays.'

1937 – Both respirator – Also known as the ''Both Portable Cabinet Respirator'', was a negative pressure ventilator (more commonly known as an "iron lung

An iron lung is a type of negative pressure ventilator (NPV), a mechanical respirator which encloses most of a person's body, and varies the air pressure in the enclosed space, to stimulate breathing.Shneerson, Dr. John M., Newmarket General ...

") invented by Edward Both

Edward Thomas Both, OBE (26 April 1908 – 18 November 1987) was an Australian inventor credited with the development of a number of medical, military and general-purpose inventions. These included a low-cost "iron lung", a humidicrib, the fi ...

. The respirator was an affordable alternative to the more expensive designs that had been used prior to its development (such as "Drinker's" by Philip Drinker

Philip Drinker (December 12, 1894 – October 19, 1972) was an industrial hygienist. With Louis Agassiz Shaw, he invented the first widely used iron lung in 1928.

Family and early life

Drinker's father was railroad man and Lehigh University ...

and Louis Agassiz Shaw in 1928), and accordingly came into common usage in Australia. More widespread use emerged during the 1940s and 1950s, when the Both respirator was offered free of charge to Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

hospitals by William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

.

1938 – Polocrosse

Polocrosse is a team sport that is a combination of polo and lacrosse. It is played outside, on a field (the pitch), on horseback. Each rider uses a cane or fibreglass stick to which is attached a racquet head with a loose, thread net, in wh ...

– Inspired by a training exercise witnessed at the National School of Equitation at Kingston Vale near London, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Hirst of Sydney invented the combination polo and lacrosse sport which was first played at Ingleburn near Sydney in 1939.

1939 – Degaussing

Degaussing is the process of decreasing or eliminating a remnant magnetic field. It is named after the gauss, a unit of magnetism, which in turn was named after Carl Friedrich Gauss. Due to magnetic hysteresis, it is generally not possible to red ...

– The degaussing of ships to counter the threat of magnetic mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any ...

s in the early days of World War II was invented and patented by mining engineer Franklin George Barnes, son of Australian politician George Barnes. Barnes' invention was later developed further by Charles F. Goodeve of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

.

1940 – Zinc Cream – This white sun block made from zinc oxide was developed by the Fauldings pharmaceutical company.

1943 – Splayd – The combination of knife, fork and spoon was invented by William McArthur after seeing ladies struggle to eat at barbecues with standard cutlery from plates on their laps.

1943 – Splayd – The combination of knife, fork and spoon was invented by William McArthur after seeing ladies struggle to eat at barbecues with standard cutlery from plates on their laps.

20th century Post-World War II

1945 – Hills Hoist – The famous Hills Hoist rotary clothes line with a winding mechanism allowing the frame to be lowered and raised with ease was developed by Lance Hill in 1945, although the clothes line design itself was originally patented by Gilbert Toyne in Adelaide in 1926. 1952 – Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer – The atomic absorption spectrophotometer is used in chemical analysis to determine low concentrations of metals in gases or vaporized solutions. It was developed by Sir Alan Walsh of the CSIRO using ionization lamps specific to the metal being detected.

1953 –

1952 – Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer – The atomic absorption spectrophotometer is used in chemical analysis to determine low concentrations of metals in gases or vaporized solutions. It was developed by Sir Alan Walsh of the CSIRO using ionization lamps specific to the metal being detected.

1953 – Solar hot water

Solar water heating (SWH) is heating water by sunlight, using a solar thermal collector

A solar thermal collector collects heat by absorbing sunlight. The term "solar collector" commonly refers to a device for solar hot water heating, bu ...

– Developed by a team at the CSIRO led by Roger N Morse

1953 – Mills Cross Telescope – a two-dimensional radio telescope designed and invented by Bernard Yarnton Mills at the CSIRO.

1955 – Distance Measuring Equipment (DME) – Invented and developed by Edward George Bowen of the CSIRO, the first DME network, operating in the 200 MHz band, became operational in Australia. Distance measuring equipment is a radio navigation

Radio navigation or radionavigation is the application of radio frequencies to determine a position of an object on the Earth, either the vessel or an obstruction. Like radiolocation, it is a type of radiodetermination.

The basic principles ...

technology that measures the slant range

In radio electronics, especially radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacec ...

(distance) between an aircraft and a ground station by timing the propagation delay

Propagation delay is the time duration taken for a signal to reach its destination. It can relate to networking, electronics or physics. ''Hold time'' is the minimum interval required for the logic level to remain on the input after triggering ed ...

of radio signals

1956 – Pneumatic broadacre air seeder – lightweight air seeder uses a spinning distributor, blew the seeds through a pipe into the plating tynes.

1956 – Stainless Steel Braces – Percy Raymond Begg of Adelaide collaborated with metallurgist Arthur Wilcock to develop a gentler, stainless steel system in 1956 involving gradual adjustments rather than earlier brute force methods used to straighten teeth.

1957 – Flame ionisation detector – The flame ionisation detector is one of the most accurate instruments ever developed for the detection of emissions. It was invented by Ian McWilliam. The instrument, which can measure one part in 10 million, has been used in chemical analysis in the petrochemical industry, medical and biochemical research, and in the monitoring of the environment.

1957 – Wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

...

clothing with a permanent crease – "SiroSet," the process for producing permanently creased fabric, was invented by Dr Arthur Farnworth of the CSIRO.

1958 –

1958 – Black box

In science, computing, and engineering, a black box is a system which can be viewed in terms of its inputs and outputs (or transfer characteristics), without any knowledge of its internal workings. Its implementation is "opaque" (black). The te ...

flight recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has ...

– The 'black box' voice and instrument data recorder was invented by Dr David Warren in Melbourne.

1960s – Self constructing tower crane – Eric Favelle created the self-construct tower crane (also known as the kangaroo crane, self erecting crane or leaping crane). The crane hydraulically raises the tower, allowing another piece to be installed. It has been involved in the construction of many of the tallest building in Australia and Dubai

Dubai (, ; ar, دبي, translit=Dubayy, , ) is the most populous city in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the capital of the Emirate of Dubai, the most populated of the 7 emirates of the United Arab Emirates.The Government and Politics ...

including the Burj Khalifa

The Burj Khalifa (; ar, برج خليفة, , Khalifa Tower), known as the Burj Dubai prior to its inauguration in 2010, is a skyscraper in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. It is known for being the world’s tallest building. With a total height ...

and in many of the world's tallest buildings, including the World Trade Centre and its replacement the One World Trade Center

One World Trade Center (also known as One World Trade, One WTC, and formerly Freedom Tower) is the main building of the rebuilt World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan, New York City. Designed by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Me ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

and the Petronas Towers

The Petronas Towers, also known as the Petronas Twin Towers or KLCC Twin Towers, ( Malay: ''Menara Berkembar Petronas'') are 88-storey supertall skyscrapers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, standing at . From 1998 to 2003, they were officially desig ...

in Kuala Lumpur

, anthem = ''Maju dan Sejahtera''

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Malaysia#Southeast Asia#Asia

, pushpin_map_caption =

, coordinates =

, sub ...

.

1960 – Plastic spectacle lenses – The world's first plastic spectacle lenses, 60 per cent lighter than glass lenses, were designed by Scientific Optical Laboratories in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the list of cities in Australia by population, fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater A ...

.

1961 – Medical ultrasound

Medical ultrasound includes diagnostic techniques (mainly imaging techniques) using ultrasound, as well as therapeutic applications of ultrasound. In diagnosis, it is used to create an image of internal body structures such as tendons, muscl ...

– David Robinson and George Kossoff's work at the Australian Department of Health, resulted in the first commercially practical water path ultrasonic scanner in 1961.

1963 – Rostrum camera – The first animation rostrum was commissioned by Graphik Animation, later known as Raymond Lea Animation in 1963. Designed and constructed by Jack Kennedy with the assistance of Jim Lynich, it was in operation by 1964.

1964 – Latex gloves

Latex is an emulsion (stable dispersion) of polymer microparticles in water. Latexes are found in nature, but synthetic latexes are common as well.

In nature, latex is found as a milky fluid found in 10% of all flowering plants (angiospe ...

– The Ansell company developed the worlds first latex gloves.

1965 – Inflatable escape slide – invented by Jack Grant of Qantas

Qantas Airways Limited ( ) is the flag carrier of Australia and the country's largest airline by fleet size, international flights, and international destinations. It is the List of airlines by foundation date, world's third-oldest airline sti ...

.

1965 – Wine cask – Invented by Thomas Angove of Renmark, South Australia, the wine cask is a cardboard box housing a plastic container which collapses as the wine is drawn off, thus preventing contact with the air. Angroves' original design with a resealable spout was replaced with a tap by the Penfolds wine company in 1972

1970 – Staysharp knife – The self-sharpening knife was developed by Wiltshire.

1971 – Variable

1965 – Wine cask – Invented by Thomas Angove of Renmark, South Australia, the wine cask is a cardboard box housing a plastic container which collapses as the wine is drawn off, thus preventing contact with the air. Angroves' original design with a resealable spout was replaced with a tap by the Penfolds wine company in 1972

1970 – Staysharp knife – The self-sharpening knife was developed by Wiltshire.

1971 – Variable rack and pinion

A rack and pinion is a type of linear actuator that comprises a circular gear (the '' pinion'') engaging a linear gear (the ''rack''). Together, they convert rotational motion into linear motion. Rotating the pinion causes the rack to be driven ...

steering – The variable ratio rack and pinion steering in motor vehicles allowing smooth steering with minimal feedback was invented by Australian engineer, Arthur Bishop.

1971 – Microwave Landing System – An all-weather, precision radio guidance system intended to be installed at large airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport. Airports usually consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surfa ...

s to assist aircraft in landing, including 'blind landings'. Microwave landing system (MLS) employs 5 GHz transmitters at the landing place which use passive electronically scanned arrays to send scanning beams towards approaching aircraft. An aircraft that enters the scanned volume uses a special receiver that calculates its position by measuring the arrival times of the beams. The project was called INTERSCAN and was developed by the Radio Physics Division of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency responsible for scientific research.

CSIRO works with leading organisations around the world. From its headquarters in Canberra, CSIRO ...

). It has since been accepted as the world standard technology for assisted landing since 1978 and is still being installed and used in airports around the world such as Heathrow Airport.

1972 – Orbital engine – The orbital internal combustion process engine was invented by engineer Ralph Sarich of Perth, Western Australia. The system uses a single piston to directly inject fuel into 5 orbiting chambers. It has never challenged the dominance of four-stroke combustion engines but has replaced many two-stroke engines with a more efficient, powerful and cleaner system. Orbital engines now appear in boats, motorcycles and small cars.

1972 – Instream analysis – To speed-up analysis of metals during the recovery process, which used to take up to 24 hours, Amdel Limited developed an on-the-spot analysis equipment called the In-Stream Analysis System, for the processing of copper, zinc, lead and platinum – and the washing of coal. This computerised system allowed continuous analysis of key metals and meant greater productivity for the mineral industry worldwide.

1972 – Power board – Peter Talbot, working under Frank Bannigan at

1972 – Power board – Peter Talbot, working under Frank Bannigan at Kambrook

Breville Group Limited or simply Breville is an Australian multinational manufacturer and marketer of home appliances, headquartered in the inner suburb of Alexandria, Sydney. The company's brands include Breville, Kambrook and Ronson (outside ...

, invented the power board. This allows multiple electrical devices to be powered where only a single wall socket is available. This is a well-known example of failing to protect intellectual property. Kambrook was more interested in immediate commercial release than patenting its idea and has never received any royalties from this now ubiquitous product.

1973 – Sirosmelt lance and the ISASMELT process – The Sirosmelt lance was invented Dr Bill Denholm and Dr John Floyd at the CSIRO and by Mount Isa Mines

Mount Isa Mines Limited ("MIM") operates the Mount Isa copper, lead, zinc and silver mines near Mount Isa, Queensland, Australia as part of the Glencore group of companies. For a brief period in 1980, MIM was Australia's largest company. It ha ...

(a subsidiary of MIM Holdings. The lance was developed to be an energy-efficient smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ...

process and improve the tin-smelting processes with the final process being called the ISASMELT process.J H Fewings, "Management of Innovation – The ISASMELT process," Presented at the AMIRA ''Innovation in Metal Production'' technical meeting at Mount Isa, Queensland, 3–4 October 1988J M Floyd and D S Conochie, SIROSMELT – The first ten years, in ''Extractive Metallurgy Symposium'', pp 1–8, The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Melbourne Branch, 1984.

1974 – Super Sopper – Gordon Withnall at the age of 56 invented the Super Sopper, a giant rolling sponge used to quickly soak up water from sporting grounds so that play can continue.

1975 – Instant Boiling Water Heater – designed and patented by engineers at Zip Industries.

1976 – logMAR chart – The logMAR (Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution) chart was developed at the National Vision Research Institute of Australia

The Australian College of Optometry (ACO) is a not-for-profit organisation in Australia committed to improving the eye health and well-being of Australian communities. Established in 1940, the ACO delivers public health optometry, vision resear ...

and consists of rows of letters that is used by ophthalmologists

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a medic ...

, orthoptists, optometrists

Optometry is a specialized health care profession that involves examining the eyes and related structures for defects or abnormalities. Optometrists are health care professionals who typically provide comprehensive primary eye care.

In the Un ...

, and vision scientists to estimate visual acuity

Visual acuity (VA) commonly refers to the clarity of vision, but technically rates an examinee's ability to recognize small details with precision. Visual acuity is dependent on optical and neural factors, i.e. (1) the sharpness of the retinal ...

. It was designed to enable a more accurate estimate of acuity than other charts (e.g., the Snellen chart

A Snellen chart is an eye chart that can be used to measure visual acuity. Snellen charts are named after the Dutch ophthalmologist Herman Snellen, who developed the chart in 1862. Many ophthalmologists and vision scientists now use an improv ...

) and is recommended particularly in a research setting.Bailey IL, Lovie JE. I (1976.) ''New design principles for visual acuity letter charts''. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 53 (11): pp. 740–745.

1977 – Laser airborne depth sounder (LADS) – The Laser airborne depth sounder is an aircraft-based hydrographic surveying

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/ offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

system used by the Australian Hydrographic Service

The Australian Hydrographic Service (formerly known as the Royal Australian Navy Hydrographic Service) is the Australian Commonwealth Government agency responsible for providing hydrographic services that meet Australia's obligations under the SO ...

(AHS).Slade, in Oldham, ''100 Years of the Royal Australian Navy'', p. 171 The system uses the difference between the sea surface and the sea floor as calculated from the aircraft's altitude to generate hydrographic data. The Defence Science and Technology Organisation

The Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG) is part of the Australian Department of Defence dedicated to providing science and technology support to safeguard Australia and its national interests. The agency's name was changed from Defenc ...

developed the LADS system.

1978 – Synroc Synroc, a portmanteau of "synthetic rock", is a means of safely storing radioactive waste. It was pioneered in 1978 by a team led by Professor Ted Ringwood at the Australian National University, with further research undertaken in collaboration with ...

– The synthetic ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelai ...

Synroc that incorporates radioactive waste into its crystal structure was invented in 1978 by a team led by Dr Ted Ringwood at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

.

1979 –

1979 – Digital sampler

A sampler is an electronic or digital musical instrument which uses sound recordings (or " samples") of real instrument sounds (e.g., a piano, violin, trumpet, or other synthesizer), excerpts from recorded songs (e.g., a five-second bass guitar ...

– The Fairlight CMI (Computer Musical Instrument) was the first polyphonic digital sampling synthesizer. It was designed in 1979 by the founders of Fairlight Fairlight may refer to:

In places:

* Fairlight, East Sussex, a village east of Hastings in southern England, UK

* Fairlight, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Fairlight, Saskatchewan, Canada

In other uses:

* Fairlight (company), an ...

, Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie in Sydney, Australia.

1979 – RaceCam – Race Cam was developed by Geoff Healey, an engineer with the Australian Television Network now the Seven Network

The Seven Network (commonly known as Channel Seven or simply Seven) is a major Australian commercial free-to-air television network. It is owned by Seven West Media Limited, and is one of five main free-to-air television networks in Australi ...

in Sydney. The tiny lightweight camera is used in sports broadcasts and provides viewers with spectacular views of events such as motor racing, which are impossible with conventional cameras.

1979 –

1979 – Bionic ear

A cochlear implant (CI) is a surgically implanted neuroprosthesis that provides a person who has moderate-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss with sound perception. With the help of therapy, cochlear implants may allow for improved speech unde ...

– The cochlear implant was invented by Professor Graeme Clark of the University of Melbourne.

1980 – Dual flush toilet – Bruce Thompson, working for Caroma

Caroma (Caroma Dorf) is an Australian designer and distributor of bathroom products. Caroma was established in 1941 by Hungarian-born Charles Rothauser, and since closing its last factory in 2017 now sources all products from third-party overseas ...

in Australia, developed the Duoset cistern, with two buttons, and two flush volumes as a water-saving measure, now responsible for savings in excess of 32000 litres of water per household per year.

1980 – Sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe

The sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (also sensitive high mass-resolution ion microprobe or SHRIMP) is a large-diameter, double-focusing secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) sector instrument produced by Australian Scientific Instrumen ...

– The sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe (also sensitive high mass-resolution ion microprobe or SHRIMP) is a large-diameter, double-focusing secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS) sector instrument

A sector instrument is a general term for a class of mass spectrometer that uses a static electric (E) or magnetic (B) sector or some combination of the two (separately in space) as a mass analyzer. Popular combinations of these sectors have been ...

created at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

in Canberra.

1980 – Wave-piercing

A wave-piercing boat hull has a very fine bow, with reduced buoyancy in the forward portions. When a wave is encountered, the lack of buoyancy means the hull pierces through the water rather than riding over the top, resulting in a smoother rid ...

catamaran – The first high speed, stable catamarans were developed by Phillip Hercus and Robert Clifford of Incat in Tasmania.

1981 – Hovering rocket –The Hoveroc rocket was first flown on 2 May 1981 as a project carried out by Defence Science and Technology Group

The Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG) is part of the Australian Department of Defence dedicated to providing science and technology support to safeguard Australia and its national interests. The agency's name was changed from Defenc ...

. It was the world's first practical hovering rocket.

1981 – CPAP mask – Professor Colin Sullivan of Sydney University

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

developed the Continuous Positive Airflow Pressure (CPAP) mask. The CPAP system first developed by Sullivan has become the most common treatment for sleep disordered breathing

When we sleep, our breathing changes due to normal biological processes that affect both our respiratory and muscular systems.

Physiology

Sleep Onset

Breathing changes as we transition from wakefulness to sleep. These changes arise due to biolog ...

. The invention was commercialised in 1989 by Australian firm ResMed

ResMed Inc. is a San Diego, California-based medical equipment company. It primarily provides cloud-connectable medical devices for the treatment of sleep apnea (such as CPAP devices and masks), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an ...

, which is currently one of the world's two largest suppliers of CPAP technology.

Australia II

''Australia II'' (KA 6) is an Australian 12-metre-class America's Cup challenge racing yacht that was launched in 1982 and won the 1983 America's Cup for the Royal Perth Yacht Club. Skippered by John Bertrand, she was the first successful Cu ...

end the New York Yacht Club

The New York Yacht Club (NYYC) is a private social club and yacht club based in New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. It was founded in 1844 by nine prominent sportsmen. The members have contributed to the sport of yachting and yacht design. ...

's 132-year ownership of the America's Cup

The America's Cup, informally known as the Auld Mug, is a trophy awarded in the sport of sailing. It is the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one ...

. The keel gave the yacht better steering and manoeuvrability in heavy winds.

1983 – Foot rot vaccine – CSIRO produced the first vaccine against foot rot using genetic engineering techniques.

1984 – Frozen embryo baby- The world's first frozen embryo baby was born in Melbourne on 28 March 1984

1984 – Baby Safety Capsule – In 1984, for the first time babies had a bassinette with an air bubble in the base and a harness that distributed forces across the bassinette protecting the baby. New South Wales public hospitals now refuse to allow parents to take a baby home by car without one.

1984 - PB/5 ATPD - Audio-Tactile Pedestrian Detector, combining a two-rhythm buzzer, a vibrating touch panel, and braille direction arrow for safe pedestrian road crossing.

1985 – Technegas – Technegas is an inhalable aerosol radioactively labelled with the isotope 99mTc, and is employed in nuclear medicine imaging for lung ventilation scanning. Technegas lung scans in conjunction with lung perfusion scans demonstrate the presence of the life-threatening condition of pulmonary embolism. Technegas was invented in Australia by Dr Richard Fawdry and Dr Bill Burch.

1985 – Bronchitis vaccine – An oral vaccine (called ''Broncostat'') to prevent bronchitis was developed by Professor Dr Robert Clancy at the University of Newcastle. It reduces attacks of acute bronchitis

Acute bronchitis, also known as a chest cold, is short-term bronchitis – inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) of the lungs. The most common symptom is a cough. Other symptoms include coughing up mucus, wheezing, sho ...

by up to 90%.

1986 – Gene shears – The discovery of gene shears was made by CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency responsible for scientific research.

CSIRO works with leading organisations around the world. From its headquarters in Canberra, CSIRO ...

scientists, Wayne Gerlach and Jim Haseloff. So-called hammerhead ribozyme

The hammerhead ribozyme is an RNA motif that catalyzes reversible cleavage and ligation reactions at a specific site within an RNA molecule. It is one of several catalytic RNAs (ribozymes) known to occur in nature. It serves as a model system for ...

s are bits of genetic material that interrupt a DNA code at a particular point, and can be used to cut out genes that cause disease or harmful proteins.

1988 – Polymer banknote

Polymer banknotes are banknotes made from a synthetic polymer such as biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP). Such notes incorporate many security features not available in paper banknotes, including the use of metameric inks. Polymer banknote ...

– The development of the polymer bank note was made by CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency responsible for scientific research.

CSIRO works with leading organisations around the world. From its headquarters in Canberra, CSIRO ...

scientists led by Dr. David Solomon. Securency Pty Ltd, a joint venture between the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and UCB, brought the note into full production and polymer bank notes are now used in 30 countries besides Australia. The chief advantages are high counterfeiting resistance and longer circulation lifetimes.

1988 – Non-chemical biological pesticide – The world's first non-chemical biological pesticide was invented at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on ...

.

1989 – Polilight The Polilight is a portable, high-intensity, filtered light source used by forensic scientists and others to detect fingerprints, bodily fluids and other evidence from crime scenes and other places.

Similar products to the Polilight Hola include ...

forensic lamp – Ron Warrender and Milutin Stoilovic, forensic scientists at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

in Canberra, developed Unilite which could be set to just the right wavelength to show fingerprints up well against any background. Rofin Australia Pty Ltd, developed this product into the portable Polilight which shows up invisible clues such as fingerprints and writing that has been scribbled over, as well as reworked sections on paintings.

1991 – Buffalo fly trap – In 1991 the CSIRO developed a low-tech translucent plastic tent with a dark inner tunnel lined with brushes. When a cow walks through, the brushed flies fly upwards toward the light and become trapped in the solar-heated plastic dome where they quickly die from desiccation (drying out) and fall to the ground, where ants eat them.

1991 – Plastic rod bone repair – The technique of using plastic rods in place of metal pins and screws was developed by Dr Michael Ryan and Dr Stephen Ruff at Sydney's North Shore Hospital. Repairing bones with plastic rods stops interference with MRI and CAT scans

A computed tomography scan (CT scan; formerly called computed axial tomography scan or CAT scan) is a medical imaging technique used to obtain detailed internal images of the body. The personnel that perform CT scans are called radiographers ...

. Several types of plastic screws are now used in orthopaedic surgery

Orthopedic surgery or orthopedics ( alternatively spelt orthopaedics), is the branch of surgery concerned with conditions involving the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedic surgeons use both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal ...

. Some are absorbed into the body, unlike metal screws, which often have to be surgically removed.

1991 – St Vincents heart valve – An artificial heart valve

An artificial heart valve is a one-way valve implanted into a person's heart to replace a heart valve that is not functioning properly ( valvular heart disease). Artificial heart valves can be separated into three broad classes: mechanical ...

designed by Dr Victor Chang for the replacement of dysfunctional ventricle heart valves in people with chronic heart diseases at St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney