Archaea Genera on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Archaea ( ) is a domain of

The classification of archaea, and of prokaryotes in general, is a rapidly moving and contentious field. Current classification systems aim to organize archaea into groups of organisms that share structural features and common ancestors. These classifications rely heavily on the use of the sequence of

The classification of archaea, and of prokaryotes in general, is a rapidly moving and contentious field. Current classification systems aim to organize archaea into groups of organisms that share structural features and common ancestors. These classifications rely heavily on the use of the sequence of

The evolutionary relationship between archaea and

The evolutionary relationship between archaea and

Archaeal membranes are made of molecules that are distinctly different from those in all other life forms, showing that archaea are related only distantly to bacteria and eukaryotes. In all organisms,

Archaeal membranes are made of molecules that are distinctly different from those in all other life forms, showing that archaea are related only distantly to bacteria and eukaryotes. In all organisms,

Other archaea use in the

Other archaea use in the

Archaea are genetically distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes, with up to 15% of the proteins encoded by any one archaeal genome being unique to the domain, although most of these unique genes have no known function. Of the remainder of the unique proteins that have an identified function, most belong to the Methanobacteriati and are involved in methanogenesis. The proteins that archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes share form a common core of cell function, relating mostly to transcription,

Archaea are genetically distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes, with up to 15% of the proteins encoded by any one archaeal genome being unique to the domain, although most of these unique genes have no known function. Of the remainder of the unique proteins that have an identified function, most belong to the Methanobacteriati and are involved in methanogenesis. The proteins that archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes share form a common core of cell function, relating mostly to transcription,

Archaea exist in a broad range of

Archaea exist in a broad range of

The well-characterized interactions between archaea and other organisms are either Mutualism (biology), mutual or commensalism, commensal. There are no clear examples of known archaeal

The well-characterized interactions between archaea and other organisms are either Mutualism (biology), mutual or commensalism, commensal. There are no clear examples of known archaeal

Introduction to the Archaea, ecology, systematics and morphology

Oceans of Archaea

nbsp;– E.F. DeLong, ''ASM News'', 2003

NCBI taxonomy page on Archaea

nbsp;– list of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature

Shotgun sequencing finds nanoorganisms

nbsp;– discovery of the ARMAN group of archaea

Browse any completed archaeal genome at UCSC

Comparative Analysis of Archaeal Genomes

(at United States Department of Energy, DOE's Integrated Microbial Genomes System, IMG system) {{Authority control Archaea, Archaea Extremophiles Domains (biology) Systems of bacterial taxonomy Biology terminology

organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s. Traditionally, Archaea only included its prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

, as eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s are known to have evolved from archaea. Even though the domain Archaea cladistically includes eukaryotes, the term "archaea" (: archaeon , from the Greek "ἀρχαῖον", which means ancient) in English still generally refers specifically to prokaryotic members of Archaea. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, receiving the name archaebacteria (, in the Archaebacteria kingdom), but this term has fallen out of use. Archaeal cells have unique properties separating them from Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and Eukaryota

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

. Archaea are further divided into multiple recognized phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

. Classification is difficult because most have not been isolated in a laboratory and have been detected only by their gene sequences in environmental samples. It is unknown if they can produce endospore

An endospore is a dormant, tough, and non-reproductive structure produced by some bacteria in the phylum Bacillota. The name "endospore" is suggestive of a spore or seed-like form (''endo'' means 'within'), but it is not a true spore (i.e., not ...

s.

Archaea are often similar to bacteria in size and shape, although a few have very different shapes, such as the flat, square cells of ''Haloquadratum walsbyi

''Haloquadratum walsbyi'' is a species of Archaea in the genus ''Haloquadratum'', known for its square shape and halophilic nature.

First discovered in a brine pool in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, ''H. walsbyi'' is noted for its flat, square- ...

''. Despite this, archaea possess gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s and several metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably for the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s involved in transcription and translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

. Other aspects of archaeal biochemistry are unique, such as their reliance on ether lipid

In biochemistry, an ether lipid refers to any lipid in which the lipid "tail" group is attached to the glycerol backbone via an ether, ether bond at any position. In contrast, conventional glycerophospholipids and triglycerides are triesters. St ...

s in their cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s, including archaeols. Archaea use more diverse energy sources than eukaryotes, ranging from organic compounds

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

such as sugars, to ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

, metal ions

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against n ...

or even hydrogen gas

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatomi ...

. The salt-tolerant Haloarchaea

Haloarchaea (halophilic archaea, halophilic archaebacteria, halobacteria) are a class of prokaryotic archaea under the phylum Euryarchaeota, found in water saturated or nearly saturated with salt. 'Halobacteria' are now recognized as archaea r ...

use sunlight as an energy source, and other species of archaea fix carbon (autotrophy), but unlike cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, no known species of archaea does both. Archaea reproduce asexually by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical o ...

, fragmentation, or budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is kno ...

; unlike bacteria, no known species of Archaea form endospore

An endospore is a dormant, tough, and non-reproductive structure produced by some bacteria in the phylum Bacillota. The name "endospore" is suggestive of a spore or seed-like form (''endo'' means 'within'), but it is not a true spore (i.e., not ...

s. The first observed archaea were extremophile

An extremophile () is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, press ...

s, living in extreme environments such as hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

s and salt lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per liter). I ...

s with no other organisms. Improved molecular detection tools led to the discovery of archaea in almost every habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

, including soil, oceans, and marshland

In ecology, a marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous plants rather than by woody plants.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p More in general ...

s. Archaea are particularly numerous in the oceans, and the archaea in plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

may be one of the most abundant groups of organisms on the planet.

Archaea are a major part of Earth's life. They are part of the microbiota of all organisms. In the human microbiome

The human microbiome is the aggregate of all microbiota that reside on or within human tissues and biofluids along with the corresponding List of human anatomical features, anatomical sites in which they reside, including the human gastrointes ...

, they are important in the gut, mouth, and on the skin. Their morphological, metabolic, and geographical diversity permits them to play multiple ecological roles: carbon fixation; nitrogen cycling; organic compound turnover; and maintaining microbial symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

and syntrophic communities, for example. No archaea are known to be pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

s or parasite

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives (at least some of the time) on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted str ...

s; many are mutualists or commensals, such as the methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s (methane-producers) that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

in humans and ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s, where their vast numbers facilitate digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

. Methanogens are used in biogas

Biogas is a gaseous renewable energy source produced from raw materials such as agricultural waste, manure, municipal waste, plant material, sewage, green waste, Wastewater treatment, wastewater, and food waste. Biogas is produced by anaerobic ...

production and sewage treatment

Sewage treatment is a type of wastewater treatment which aims to remove contaminants from sewage to produce an effluent that is suitable to discharge to the surrounding environment or an intended reuse application, thereby preventing water p ...

, while biotechnology

Biotechnology is a multidisciplinary field that involves the integration of natural sciences and Engineering Science, engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms and parts thereof for products and services. Specialists ...

exploits enzymes from extremophile archaea that can endure high temperatures and organic solvents

A solvent (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for p ...

.

Discovery and classification

Early concept

For much of the 20th century, prokaryotes were regarded as a single group of organisms and classified based on theirbiochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

, morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

and metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

. Microbiologists tried to classify microorganisms based on the structures of their cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s, their shapes, and the substances they consume. In 1965, Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

instead proposed using the sequences of the gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s in different prokaryotes to work out how they are related to each other. This phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical dat ...

approach is the main method used today.

Archaea were first classified separately from bacteria in 1977 by Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese ( ; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal ...

and George E. Fox, based on their ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

(rRNA) genes. (At that time only the methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s were known). They called these groups the ''Urkingdoms'' of Archaebacteria and Eubacteria, though other researchers treated them as kingdoms

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchic state or realm ruled by a king or queen.

** A monarchic chiefdom, represented or governed by a king or queen.

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and me ...

or subkingdoms. Woese and Fox gave the first evidence for Archaebacteria as a separate "line of descent": 1. lack of peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

in their cell walls, 2. two unusual coenzymes, 3. results of 16S ribosomal RNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16 S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome ( SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as 16S ...

gene sequencing. To emphasize this difference, Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis later proposed reclassifying organisms into three then thought to be natural domains known as the three-domain system

The three-domain system is a taxonomic classification system that groups all cellular life into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya, introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990. The key difference from ea ...

: the Eukarya

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of l ...

, the Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and the Archaea, in what is now known as the Woesian Revolution.

The word ''archaea'' comes from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, meaning "ancient things", as the first representatives of the domain Archaea were methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s and it was assumed that their metabolism reflected Earth's primitive atmosphere and the organisms' antiquity, but as new habitats were studied, more organisms were discovered. Extreme halophilic

A halophile (from the Greek word for 'salt-loving') is an extremophile that thrives in high salt concentrations. In chemical terms, halophile refers to a Lewis acidic species that has some ability to extract halides from other chemical species.

...

and hyperthermophilic microbes were also included in Archaea. For a long time, archaea were seen as extremophiles that exist only in extreme habitats such as hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

s and salt lake

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per liter). I ...

s, but by the end of the 20th century, archaea had been identified in non-extreme environments as well. Today, they are known to be a large and diverse group of organisms abundantly distributed throughout nature. This new appreciation of the importance and ubiquity of archaea came from using polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

(PCR) to detect prokaryotes from environmental samples (such as water or soil) by multiplying their ribosomal genes. This allows the detection and identification of organisms that have not been cultured in the laboratory.

Classification

The classification of archaea, and of prokaryotes in general, is a rapidly moving and contentious field. Current classification systems aim to organize archaea into groups of organisms that share structural features and common ancestors. These classifications rely heavily on the use of the sequence of

The classification of archaea, and of prokaryotes in general, is a rapidly moving and contentious field. Current classification systems aim to organize archaea into groups of organisms that share structural features and common ancestors. These classifications rely heavily on the use of the sequence of ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

genes to reveal relationships among organisms (molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

). Most of the culturable and well-investigated species of archaea are members of two main kingdoms, the Methanobacteriati

Methanobacteriati (formerly "Euryarchaeota", from Ancient Greek ''εὐρύς'' eurús, "broad, wide") is a kingdom of archaea. Methanobacteriati are highly diverse and include methanogens, which produce methane and are often found in intestines ...

and the Thermoproteati

Thermoproteati is a kingdom of archaea. Its synonym, "TACK", is an acronym for Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota), Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and Korarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), the first groups discovered. They a ...

(formerly TACK). Other groups have been tentatively created, such as the peculiar species '' Nanoarchaeum equitans'' — discovered in 2003 and assigned its own phylum, the " Nanoarchaeota". A new phylum " ''Candidatus'' Korarchaeota" (now Thermoproteota

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum (biology), phylum of the domain Archaea. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic T ...

) has also been proposed, containing a small group of unusual thermophilic species sharing features of both the main phyla. Other detected species of archaea are only distantly related to any of these groups, such as the Archaeal Richmond Mine acidophilic nanoorganisms (ARMAN, comprising Micrarchaeota and Parvarchaeota), which were discovered in 2006 and are some of the smallest organisms known.

A superphylum – "TACK" (now kingdom Thermoproteati

Thermoproteati is a kingdom of archaea. Its synonym, "TACK", is an acronym for Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota), Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and Korarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), the first groups discovered. They a ...

)– which includes the Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota

The Nitrososphaerota (syn. Thaumarchaeota) are a phylum of the Archaea proposed in 2008 after the genome of '' Cenarchaeum symbiosum'' was sequenced and found to differ significantly from other members of the hyperthermophilic phylum Thermopr ...

), " Aigarchaeota", Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and " ''Candidatus'' Korarchaeota" (now Thermoproteota) was proposed in 2011 to be related to the origin of eukaryotes. In 2017, the newly discovered and newly named "Asgard" (now kingdom Promethearchaeati) superphylum was proposed to be more closely related to the original eukaryote and a sister group to Thermoproteati / "TACK".

In 2013, the superphylum "DPANN" (now kingdom Nanobdellati) was proposed to group " Nanoarchaeota", " Nanohaloarchaeota", Archaeal Richmond Mine acidophilic nanoorganisms (ARMAN, comprising " Micrarchaeota" and " Parvarchaeota"), and other similar archaea. This archaeal superphylum encompasses at least 10 different lineages and includes organisms with extremely small cell and genome sizes and limited metabolic capabilities. Therefore, Nanobdellati/"DPANN" may include members obligately dependent on symbiotic interactions, and may even include novel parasites. However, other phylogenetic analyses found that Nanobdellati/"DPANN" does not form a monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

group, and that the apparent grouping is caused by long branch attraction

In phylogenetics, long branch attraction (LBA) is a form of systematic error whereby distantly related lineages are incorrectly inferred to be closely related. LBA arises when the amount of molecular or morphological change accumulated within a lin ...

(LBA), suggesting that all these lineages belong to Methanobacteriati.

Phylogeny

According to Tom A. Williams ''et al.'' 2017, Castelle & Banfield (2018) and GTDB release 10-RS226 (16th April 2025).Concept of species

The classification of archaea into species is also controversial.Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr ( ; ; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was a German-American evolutionary biologist. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher of biology, and ...

's species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

definition — a reproductively isolated group of interbreeding organisms — does not apply, as archaea reproduce only asexually.

Archaea show high levels of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

between lineages. Some researchers suggest that individuals can be grouped into species-like populations given highly similar genomes and infrequent gene transfer to/from cells with less-related genomes, as in the genus ''Ferroplasma

''Ferroplasma'' is a genus of Archaea that belong to the family Ferroplasmaceae. Members of the ''Ferroplasma'' are typically acidophilic, pleomorphic, irregularly shaped cocci.

The archaean family Ferroplasmaceae was first described in the earl ...

''. On the other hand, studies in ''Halorubrum

''Halorubrum'' is a genus in the family Halorubraceae. ''Halorubrum'' species are usually halophilic and can be found in waters with high salt concentration such as the Dead Sea or Lake Zabuye.

Genetic exchange

A population of the haloarchaea '' ...

'' found significant genetic transfer to/from less-related populations, limiting the criterion's applicability. Some researchers question whether such species designations have practical meaning.

Current knowledge on genetic diversity in archaeans is fragmentary, so the total number of species cannot be estimated with any accuracy. Estimates of the number of phyla range from 18 to 23, of which only 8 have representatives that have been cultured and studied directly. Many of these hypothesized groups are known from a single rRNA sequence, so the level of diversity remains obscure. This situation is also seen in the Bacteria; many uncultured microbes present similar issues with characterization.

Prokaryotic phyla

Valid phyla

The following phyla have been validly published according to the Prokaryotic Code; belonging to the four kingdoms of archaea: * Methanobacteriota * Microcaldota * Nanobdellota * Promethearchaeota *Thermoproteota

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum (biology), phylum of the domain Archaea. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic T ...

Candidate phyla

The following phyla have been proposed, but have not been validly published according to the Prokaryotic Code; phyla that do not belong to any kingdom are shown in bold: *" ''Ca.'' Aenigmatarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Altarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Augarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Freyrarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Geoarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Hadarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Hodarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Huberarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Hydrothermarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Iainarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Kariarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Micrarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Nanohalarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Nezhaarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Parvarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Poseidoniota" *" ''Ca.'' Undinarchaeota" *" ''Ca.'' Sigynarchaeota"Origin and evolution

Theage of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

is about 4.54 billion years. Scientific evidence suggests that life began on Earth at least 3.5 billion years ago

bya or b.y.a. is an abbreviation for " billion years ago". It is commonly used as a unit of time to denote length of time before the present in 109 years. This initialism is often used in the sciences of astronomy, geology, and paleontology.

The ...

. The earliest evidence for life on Earth is graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

found to be biogenic

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

in 3.7-billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks discovered in Western Greenland and microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few surviv ...

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

found in 3.48-billion-year-old sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

discovered in Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

. In 2015, possible remains of biotic matter were found in 4.1-billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.

Although probable prokaryotic cell fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

date to almost 3.5 billion years ago

bya or b.y.a. is an abbreviation for " billion years ago". It is commonly used as a unit of time to denote length of time before the present in 109 years. This initialism is often used in the sciences of astronomy, geology, and paleontology.

The ...

, most prokaryotes do not have distinctive morphologies, and fossil shapes cannot be used to identify them as archaea. Instead, chemical fossils of unique lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s are more informative because such compounds do not occur in other organisms. Some publications suggest that archaeal or eukaryotic lipid remains are present in shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s dating from 2.7 billion years ago, though such data have since been questioned. These lipids have also been detected in even older rocks from west Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

. The oldest such traces come from the Isua district, which includes Earth's oldest known sediments, formed 3.8 billion years ago. The archaeal lineage may be the most ancient that exists on Earth.

Woese argued that the bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes represent separate lines of descent that diverged early on from an ancestral colony of organisms. One possibility is that this occurred before the evolution of cells, when the lack of a typical cell membrane allowed unrestricted lateral gene transfer, and that the common ancestors of the three domains arose by fixation of specific subsets of genes. It is possible that the last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of bacteria and archaea was a thermophile

A thermophile is a type of extremophile that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though some of them are bacteria and fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earliest bacte ...

, which raises the possibility that lower temperatures are "extreme environments" for archaea, and organisms that live in cooler environments appeared only later. Since archaea and bacteria are no more related to each other than they are to eukaryotes, the term ''prokaryote'' may suggest a false similarity between them. However, structural and functional similarities between lineages often occur because of shared ancestral traits or evolutionary convergence. These similarities are known as a ''grade'', and prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s are best thought of as a grade of life, characterized by such features as an absence of membrane-bound organelles.

Comparison with other domains

The following table compares some major characteristics of the three domains, to illustrate their similarities and differences. Archaea were split off as a third domain because of the large differences in their ribosomal RNA structure. The particular molecule16S rRNA

16S ribosomal RNA (or 16Svedberg, S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as ...

is key to the production of proteins in all organisms. Because this function is so central to life, organisms with mutations in their 16S rRNA are unlikely to survive, leading to great (but not absolute) stability in the structure of this polynucleotide over generations. 16S rRNA is large enough to show organism-specific variations, but still small enough to be compared quickly. In 1977, Carl Woese, a microbiologist studying the genetic sequences of organisms, developed a new comparison method that involved splitting the RNA into fragments that could be sorted and compared with other fragments from other organisms. The more similar the patterns between species, the more closely they are related.

Woese used his new rRNA comparison method to categorize and contrast different organisms. He compared a variety of species and happened upon a group of methanogens with rRNA vastly different from any known prokaryotes or eukaryotes. These methanogens were much more similar to each other than to other organisms, leading Woese to propose the new domain of Archaea. His experiments showed that the archaea were genetically more similar to eukaryotes than prokaryotes, even though they were more similar to prokaryotes in structure. This led to the conclusion that Archaea and Eukarya shared a common ancestor more recent than Eukarya and Bacteria. The development of the nucleus occurred after the split between Bacteria and this common ancestor.

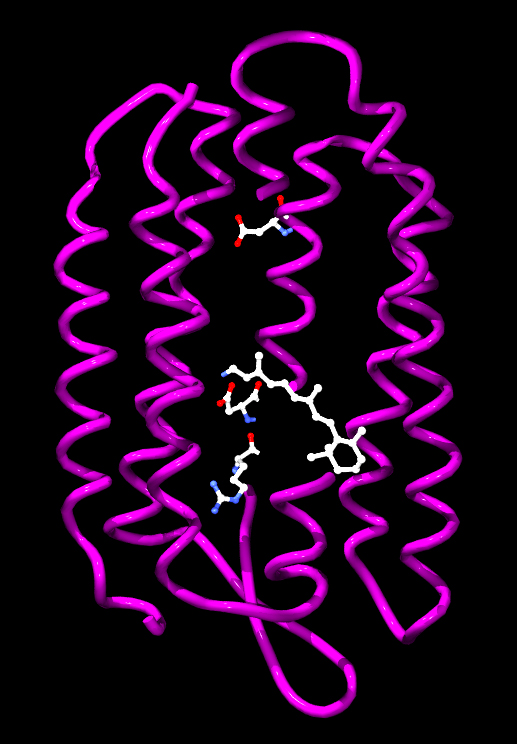

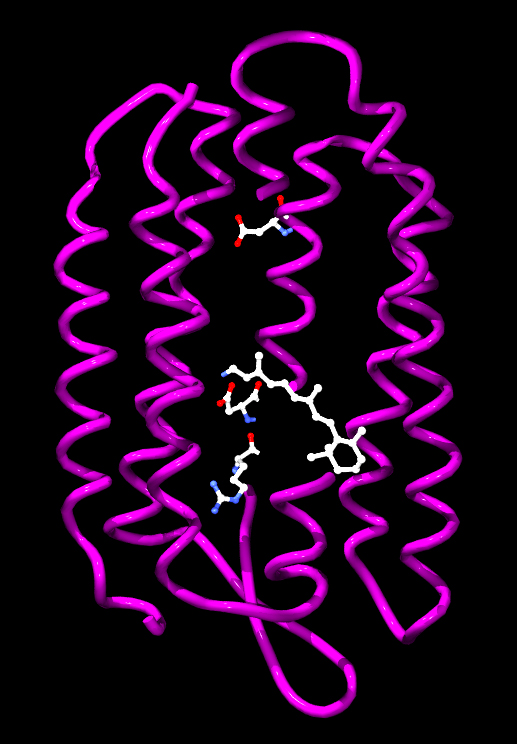

One property unique to archaea is the abundant use of ether-linked lipids in their cell membranes. Ether linkages are more chemically stable than the ester linkages found in bacteria and eukarya, which may be a contributing factor to the ability of many archaea to survive in extreme environments that place heavy stress on cell membranes, such as extreme heat and salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

. Comparative analysis of archaeal genomes has also identified several molecular conserved signature indels and signature proteins uniquely present in either all archaea or different main groups within archaea. Another unique feature of archaea, found in no other organisms, is methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. It is the fourth and final stage of anaerobic digestion. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation h ...

(the metabolic production of methane). Methanogenic archaea play a pivotal role in ecosystems with organisms that derive energy from oxidation of methane, many of which are bacteria, as they are often a major source of methane in such environments and can play a role as primary producers. Methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s also play a critical role in the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is a part of the biogeochemical cycle where carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of Earth. Other major biogeochemical cycles include the nitrogen cycle and the water cycl ...

, breaking down organic carbon into methane, which is also a major greenhouse gas.

This difference in the biochemical structure of Bacteria and Archaea has been explained by researchers through evolutionary processes. It is theorized that both domains originated at deep sea alkaline hydrothermal vents. At least twice, microbes evolved lipid biosynthesis and cell wall biochemistry. It has been suggested that the last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the hypothesized common ancestral cell from which the three domains of life, the Bacteria, the Archaea, and the Eukarya originated. The cell had a lipid bilayer; it possessed the genetic code a ...

was a non-free-living organism. It may have had a permeable membrane composed of bacterial simple chain amphiphiles (fatty acids), including archaeal simple chain amphiphiles (isoprenoids). These stabilize fatty acid membranes in seawater; this property may have driven the divergence of bacterial and archaeal membranes, "with the later biosynthesis of phospholipids giving rise to the unique G1P and G3P headgroups of archaea and bacteria respectively. If so, the properties conferred by membrane isoprenoids place the lipid divide as early as the origin of life".

Relationship to bacteria

The relationships among the three domains are of central importance for understanding the origin of life. Most of themetabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s, which are the object of the majority of an organism's genes, are common between Archaea and Bacteria, while most genes involved in gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

are common between Archaea and Eukarya. Within prokaryotes, archaeal cell structure is most similar to that of Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain is ...

bacteria, largely because both have a single lipid bilayer and usually contain a thick sacculus (exoskeleton) of varying chemical composition. In some phylogenetic trees based upon different gene / protein sequences of prokaryotic homologs, the archaeal homologs are more closely related to those of gram-positive bacteria. Archaea and gram-positive bacteria also share conserved indels

Indel (insertion-deletion) is a molecular biology term for an insertion or deletion of bases in the genome of an organism. Indels ≥ 50 bases in length are classified as structural variants.

In coding regions of the genome, unless the lengt ...

in a number of important proteins, such as Hsp70 and glutamine synthetase

Glutamine synthetase (GS) () is an enzyme that catalyzes the condensation of glutamate and ammonia to form glutamine:

Glutamate + ATP + NH3 → Glutamine + ADP + phosphate

Glutamine synthetase uses ammonia produced by nitrate reduction ...

I; but the phylogeny of these genes was interpreted to reveal inter-domain gene transfer, and might not reflect the organismal relationship(s).

It has been proposed that the archaea evolved from Gram-positive bacteria in response to antibiotic selection pressure. This is suggested by the observation that archaea are resistant to a wide variety of antibiotics that are produced primarily by Gram-positive bacteria, and that these antibiotics act primarily on the genes that distinguish archaea from bacteria. The proposal is that the selective pressure towards resistance generated by the gram-positive antibiotics was eventually sufficient to cause extensive changes in many of the antibiotics' target genes, and that these strains represented the common ancestors of present-day Archaea. The evolution of Archaea in response to antibiotic selection, or any other competitive selective pressure, could also explain their adaptation to extreme environments (such as high temperature or acidity) as the result of a search for unoccupied niches to escape from antibiotic-producing organisms; Cavalier-Smith

Thomas (Tom) Cavalier-Smith, Royal Society, FRS, Royal Society of Canada, FRSC, Natural Environment Research Council, NERC Professorial Fellow (21 October 1942 – 19 March 2021), was a professor of evolutionary biology in the Departme ...

has made a similar suggestion, the Neomura Neomura (from Ancient Greek ''neo-'' "new", and Latin ''-murus'' "wall") is a proposed clade of life composed of the two domains Archaea and Eukaryota, coined by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. Its name reflects the hypothesis that both archaea and ...

hypothesis. This proposal is also supported by other work investigating protein structural relationships and studies that suggest that gram-positive bacteria may constitute the earliest branching lineages within the prokaryotes.

Relation to eukaryotes

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s remains unclear. Aside from the similarities in cell structure and function that are discussed below, many genetic trees group the two.

Complicating factors include claims that the relationship between eukaryotes and the archaeal phylum Thermoproteota

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum (biology), phylum of the domain Archaea. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic T ...

is closer than the relationship between the Methanobacteriati

Methanobacteriati (formerly "Euryarchaeota", from Ancient Greek ''εὐρύς'' eurús, "broad, wide") is a kingdom of archaea. Methanobacteriati are highly diverse and include methanogens, which produce methane and are often found in intestines ...

and the phylum Thermoproteota and the presence of archaea-like genes in certain bacteria, such as '' Thermotoga maritima'', from horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

. The standard hypothesis states that the ancestor of the eukaryotes diverged early from the Archaea, and that eukaryotes arose through symbiogenesis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibl ...

, the fusion of an archaean and a eubacterium, which formed the mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

; this hypothesis explains the genetic similarities between the groups. The eocyte hypothesis instead posits that Eukaryota

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

emerged relatively late from the Archaea.

A lineage of archaea discovered in 2015, '' Lokiarchaeum'' (of the proposed new phylum " Lokiarchaeota"), named for a hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

called Loki's Castle

Loki's Castle is a field of five active hydrothermal vents in the Atlantic, mid-Atlantic Ocean, located at 73rd parallel north, 73 degrees north on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between Iceland and Svalbard at a depth of . When they were discovered in m ...

in the Arctic Ocean, was found to be the most closely related to eukaryotes known at that time. It has been called a transitional organism between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Several sister phyla of "Lokiarchaeota" have since been found (" Thorarchaeota", " Odinarchaeota", " Heimdallarchaeota"), all together comprising a newly proposed supergroup "Asgard".

Details of the relation of Promethearchaeati / "Asgard" members and eukaryotes are still under consideration, although, in January 2020, scientists reported that '' Candidatus Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum'', a type of Promethearchaeati / "Asgard" archaea, may be a possible link between simple prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

and complex eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

microorganisms about two billion years ago.

Morphology

Individual archaea range from 0.1 micrometers (μm) to over 15 μm in diameter, and occur in various shapes, commonly as spheres, rods, spirals or plates. Other morphologies in theThermoproteota

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum (biology), phylum of the domain Archaea. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic T ...

include irregularly shaped lobed cells in ''Sulfolobus

''Sulfolobus'' is a genus of microorganism in the family Sulfolobaceae. It belongs to the kingdom Thermoproteati of the Archaea domain.

''Sulfolobus'' species grow in volcanic springs with optimal growth occurring at pH 2–3 and temperatu ...

'', needle-like filaments that are less than half a micrometer in diameter in '' Thermofilum'', and almost perfectly rectangular rods in '' Thermoproteus'' and '' Pyrobaculum''. Archaea in the genus '' Haloquadratum'' such as ''Haloquadratum walsbyi

''Haloquadratum walsbyi'' is a species of Archaea in the genus ''Haloquadratum'', known for its square shape and halophilic nature.

First discovered in a brine pool in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, ''H. walsbyi'' is noted for its flat, square- ...

'' are flat, square specimens that live in hypersaline pools. These unusual shapes are probably maintained by both their cell walls and a prokaryotic cytoskeleton. Proteins related to the cytoskeleton components of other organisms exist in archaea, and filaments form within their cells, but in contrast with other organisms, these cellular structures are poorly understood. In ''Thermoplasma

''Thermoplasma'' is a genus of archaeans.See the NCBIbr>webpage on Thermoplasma Data extracted from the It belongs to the class Thermoplasmata, which thrive in acidic and high-temperature environments. ''Thermoplasma'' are facultative anaer ...

'' and ''Ferroplasma

''Ferroplasma'' is a genus of Archaea that belong to the family Ferroplasmaceae. Members of the ''Ferroplasma'' are typically acidophilic, pleomorphic, irregularly shaped cocci.

The archaean family Ferroplasmaceae was first described in the earl ...

'' the lack of a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

means that the cells have irregular shapes, and can resemble amoebae.

Some species form aggregates or filaments of cells up to 200 μm long. These organisms can be prominent in biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s. Notably, aggregates of '' Thermococcus coalescens'' cells fuse together in culture, forming single giant cells. Archaea in the genus '' Pyrodictium'' produce an elaborate multicell colony involving arrays of long, thin hollow tubes called ''cannulae'' that stick out from the cells' surfaces and connect them into a dense bush-like agglomeration. The function of these cannulae is not settled, but they may allow communication or nutrient exchange with neighbors. Multi-species colonies exist, such as the "string-of-pearls" community that was discovered in 2001 in a German swamp. Round whitish colonies of a novel Methanobacteriati species are spaced along thin filaments that can range up to long; these filaments are made of a particular bacteria species.

Structure, composition development, and operation

Archaea and bacteria have generally similar cell structure, but cell composition and organization set the archaea apart. Like bacteria, archaea lack interior membranes andorganelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s. Like bacteria, the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s of archaea are usually bounded by a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

and they swim using one or more flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

. Structurally, archaea are most similar to gram-positive bacteria

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain ...

. Most have a single plasma membrane and cell wall, and lack a periplasmic space; the exception to this general rule is '' Ignicoccus'', which possess a particularly large periplasm that contains membrane-bound vesicles and is enclosed by an outer membrane.

Cell wall and archaella

Most archaea (but not ''Thermoplasma

''Thermoplasma'' is a genus of archaeans.See the NCBIbr>webpage on Thermoplasma Data extracted from the It belongs to the class Thermoplasmata, which thrive in acidic and high-temperature environments. ''Thermoplasma'' are facultative anaer ...

'' and ''Ferroplasma

''Ferroplasma'' is a genus of Archaea that belong to the family Ferroplasmaceae. Members of the ''Ferroplasma'' are typically acidophilic, pleomorphic, irregularly shaped cocci.

The archaean family Ferroplasmaceae was first described in the earl ...

'') possess a cell wall. In most archaea, the wall is assembled from surface-layer proteins, which form an S-layer

An S-layer (surface layer) is a part of the cell envelope found in almost all archaea, as well as in many types of bacteria.

The S-layers of both archaea and bacteria consists of a Monolayer, monomolecular layer composed of only one (or, in a few c ...

. An S-layer is a rigid array of protein molecules that cover the outside of the cell (like chain mail

Mail (sometimes spelled maille and, since the 18th century, colloquially referred to as chain mail, chainmail or chain-mail) is a type of armour consisting of small metal rings linked together in a pattern to form a mesh. It was in common milita ...

). This layer provides both chemical and physical protection, and can prevent macromolecule

A macromolecule is a "molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass." Polymers are physi ...

s from contacting the cell membrane. Unlike bacteria, archaea lack peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

in their cell walls. Methanobacteriales do have cell walls containing pseudopeptidoglycan, which resembles eubacterial peptidoglycan in morphology, function, and physical structure, but pseudopeptidoglycan is distinct in chemical structure; it lacks D-amino acids and N-acetylmuramic acid

''N''-Acetylmuramic acid (NAM or MurNAc) is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is a monomer of peptidoglycan in most bacterial cell walls, which is built from alternating units of ''N''-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and ''N''-acet ...

, substituting the latter with N-Acetyltalosaminuronic acid.

Archaeal flagella are known as archaella, that operate like bacterial flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

– their long stalks are driven by rotatory motors at the base. These motors are powered by a proton gradient across the membrane, but archaella are notably different in composition and development. The two types of flagella evolved from different ancestors. The bacterial flagellum shares a common ancestor with the type III secretion system, while archaeal flagella appear to have evolved from bacterial type IV pili. In contrast with the bacterial flagellum, which is hollow and assembled by subunits moving up the central pore to the tip of the flagella, archaeal flagella are synthesized by adding subunits at the base.

Membranes

cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s are made of molecules known as phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s. These molecules possess both a polar part that dissolves in water (the phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

"head"), and a "greasy" non-polar part that does not (the lipid tail). These dissimilar parts are connected by a glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

moiety. In water, phospholipids cluster, with the heads facing the water and the tails facing away from it. The major structure in cell membranes is a double layer of these phospholipids, which is called a lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cell (biology), cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses a ...

.

The phospholipids of archaea are unusual in four ways:

* They have membranes composed of glycerol-ether lipid

In biochemistry, an ether lipid refers to any lipid in which the lipid "tail" group is attached to the glycerol backbone via an ether, ether bond at any position. In contrast, conventional glycerophospholipids and triglycerides are triesters. St ...

s, whereas bacteria and eukaryotes have membranes composed mainly of glycerol-ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s. The difference is the type of bond that joins the lipids to the glycerol moiety; the two types are shown in yellow in the figure at the right. In ester lipids, this is an ester bond, whereas in ether lipids this is an ether bond

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group, a single oxygen atom bonded to two separate carbon atoms, each part of an organyl group (e.g., alkyl or aryl). They have the general formula , where R and R′ ...

.

* The stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, studies the spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which are defined ...

of the archaeal glycerol moiety is the mirror image of that found in other organisms. The glycerol moiety can occur in two forms that are mirror images of one another, called ''enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer (Help:IPA/English, /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''), also known as an optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode, is one of a pair of molecular entities whi ...

s''. Just as a right hand does not fit easily into a left-handed glove, enantiomers of one type generally cannot be used or made by enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s adapted for the other. The archaeal phospholipids are built on a backbone of ''sn''-glycerol-1-phosphate, which is an enantiomer of ''sn''-glycerol-3-phosphate, the phospholipid backbone found in bacteria and eukaryotes. This suggests that archaea use entirely different enzymes for synthesizing phospholipids as compared to bacteria and eukaryotes. Such enzymes developed very early in life's history, indicating an early split from the other two domains.

* Archaeal lipid tails differ from those of other organisms in that they are based upon long isoprenoid chains with multiple side-branches, sometimes with cyclopropane

Cyclopropane is the cycloalkane with the molecular formula (CH2)3, consisting of three methylene groups (CH2) linked to each other to form a triangular ring. The small size of the ring creates substantial ring strain in the structure. Cyclopropane ...

or cyclohexane

Cyclohexane is a cycloalkane with the molecular formula . Cyclohexane is non-polar. Cyclohexane is a colourless, flammable liquid with a distinctive detergent-like odor, reminiscent of cleaning products (in which it is sometimes used). Cyclohexan ...

rings. By contrast, the fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s in the membranes of other organisms have straight chains without side branches or rings. Although isoprenoids play an important role in the biochemistry of many organisms, only the archaea use them to make phospholipids. These branched chains may help prevent archaeal membranes from leaking at high temperatures.

* In some archaea, the lipid bilayer is replaced by a monolayer. In effect, the archaea fuse the tails of two phospholipid molecules into a single molecule with two polar heads (a bolaamphiphile

In chemistry, bolaamphiphiles (also known as bolaform surfactants, bolaphiles, or alpha-omega-type surfactants) are amphiphilic molecules that have hydrophilic groups at both ends of a sufficiently long hydrophobic hydrocarbon chain. Compared to s ...

); this fusion may make their membranes more rigid and better able to resist harsh environments. For example, the lipids in ''Ferroplasma

''Ferroplasma'' is a genus of Archaea that belong to the family Ferroplasmaceae. Members of the ''Ferroplasma'' are typically acidophilic, pleomorphic, irregularly shaped cocci.

The archaean family Ferroplasmaceae was first described in the earl ...

'' are of this type, which is thought to aid this organism's survival in its highly acidic habitat.

Metabolism

Archaea exhibit a great variety of chemical reactions in theirmetabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

and use many sources of energy. These reactions are classified into nutritional groups, depending on energy and carbon sources. Some archaea obtain energy from inorganic compound

An inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bondsthat is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemistry''.

Inorgan ...

s such as sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

or ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

(they are chemotroph

A chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic ( chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic ( chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phot ...

s). These include nitrifiers, methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s and anaerobic methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

oxidisers. In these reactions, one compound passes electrons to another (in a redox

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is t ...

reaction), releasing energy to fuel the cell's activities. One compound acts as an electron donor

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that transfers electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process. An obsolete definition equated an electron dono ...

and one as an electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. Electron acceptors are oxidizing agents.

The electron accepting power of an electron acceptor is measured by its redox potential.

In the ...

. The energy released is used to generate adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a nucleoside triphosphate that provides energy to drive and support many processes in living cell (biology), cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known ...

(ATP) through chemiosmosis

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ion ...

, the same basic process that happens in the mitochondrion

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cell (biology), cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine tri ...

of eukaryotic cells.

Other groups of archaea use sunlight as a source of energy (they are phototroph

Phototrophs () are organisms that carry out photon capture to produce complex organic compounds (e.g. carbohydrates) and acquire energy. They use the energy from light to carry out various cellular metabolic processes. It is a list of common m ...

s), but oxygen–generating photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

does not occur in any of these organisms. Many basic metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s are shared among all forms of life; for example, archaea use a modified form of glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells (the cytosol). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form ...

(the Entner–Doudoroff pathway) and either a complete or partial citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

. These similarities to other organisms probably reflect both early origins in the history of life and their high level of efficiency.

Some Methanobacteriati are methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s (archaea that produce methane as a result of metabolism) living in anaerobic environment

Hypoxia (''hypo'': 'below', ''oxia'': 'oxygenated') refers to low oxygen conditions. Hypoxia is problematic for Aerobic organism, air-breathing organisms, yet it is essential for many Anaerobic organism, anaerobic organisms. Hypoxia applies to m ...

s, such as swamps. This form of metabolism evolved early, and it is even possible that the first free-living organism was a methanogen. A common reaction involves the use of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

as an electron acceptor to oxidize hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

. Methanogenesis involves a range of coenzyme

A cofactor is a non-protein chemical compound or Metal ions in aqueous solution, metallic ion that is required for an enzyme's role as a catalysis, catalyst (a catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction). Cofactors can ...