The 1984–1985 United Kingdom miners' strike was a major

industrial action

Industrial action (British English) or job action (American English) is a temporary show of dissatisfaction by employees—especially a strike action, strike or slowdown or working to rule—to protest against bad working conditions or low pay a ...

within the British

coal industry

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when de ...

in an attempt to prevent closures of pits that the government deemed "uneconomic" in the coal industry, which had been nationalised in 1947. It was led by

Arthur Scargill of the

National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) against the

National Coal Board (NCB), a government agency. Opposition to the strike was led by the

Conservative government of

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, who wanted to reduce the power of the

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

s.

The NUM was divided over the action, which began in

Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, and some mineworkers, especially in the

Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

, worked through the dispute. Few major trade unions supported the NUM, primarily using the argument of the absence of a vote at national level. Violent confrontations between

flying pickets

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in ("Strikebreaker, cro ...

and police characterised the year-long strike, which ended in a decisive victory for the

Conservative government Conservative or Tory government may refer to:

Canada

In Canadian politics, a Conservative government may refer to the following governments administered by the Conservative Party of Canada or one of its historical predecessors:

* 1st Canadian Min ...

and allowed the closure of most of Britain's collieries. Many observers regard the strike as "the most bitter industrial dispute in British history".

The number of person-days of work lost to the strike was over 26 million, making it the largest since the

1926 General Strike

The 1926 general strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British governm ...

.

The journalist

Seumas Milne

Seumas Patrick Charles Milne (born 5 September 1958)Winchester College: A Register. Edited by P.S.W.K. McClure and R.P. Stevens, on behalf of the Wardens and Fellows of Winchester College. 7th edition, 2014. pp. 582 (Short Half 1971 list heading) ...

said of the strike that "it has no real parallel – in size, duration and impact – anywhere in the world".

The NCB was encouraged to gear itself towards reduced subsidies in the early 1980s. After a strike was narrowly averted in February 1981, pit closures and pay restraint led to unofficial strikes. The main strike started on 6 March 1984 with a walkout at

Cortonwood Colliery, which led to the NUM's Yorkshire Area's sanctioning of a strike on the grounds of a ballot result from 1981 in the Yorkshire Area, which was later challenged in court. The NUM President,

Arthur Scargill, made the strike official across Britain on 12 March 1984, but the lack of a national ballot beforehand caused controversy. The NUM strategy was to cause a severe energy shortage of the sort that had won victory in the

1972 strike. The government strategy, designed by

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, was threefold: to build up ample coal stocks, to keep as many miners at work as possible, and to use police to break up attacks by pickets on working miners. The critical element was the NUM's failure to hold a national strike ballot.

[Geoffrey Goodman, ''The miners' strike'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1985), p. 48.]

The strike was ruled illegal in September 1984, as no national ballot of NUM members had been held. It ended on 3 March 1985. It was a defining moment in British industrial relations, the NUM's defeat significantly weakening the

trade union movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

. It was a major victory for Thatcher and the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, with the Thatcher government able to consolidate their economic programme. The number of strikes fell sharply in 1985 as a result of the "

demonstration effect" and trade union power in general diminished.

Three deaths resulted from events related to the strike.

The much-reduced coal industry was privatised in December 1994, ultimately becoming

UK Coal

UK Coal Production Ltd, formerly UK Coal plc, was the largest coal mining business in the United Kingdom. The company was based in Harworth, in Nottinghamshire. The company was a constituent of the FTSE 250 Index. The successor company that con ...

. In 1983, Britain had 175 working pits, all of which had closed by the end of 2015. Poverty increased in former coal mining areas, and in 1994

Grimethorpe in

South Yorkshire

South Yorkshire is a ceremonial and metropolitan county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. The county has four council areas which are the cities of Doncaster and Sheffield as well as the boroughs of Barnsley and Rotherham.

In N ...

was the poorest settlement in the country.

Background

While more than 1,000 collieries were working in the UK during the first half of the 20th century, by 1984 only 173 were still operating and employment had dropped from its peak of 1 million in 1922, down to 231,000 for the decade to 1982. This long-term decline in coal employment was common across the developed world; in the United States, employment in the coal-mining industry continued to fall from 180,000 in 1985 to 70,000 in the year 2000.

Coal mining,

nationalised

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

by

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

's

Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government in 1947, was managed by the

National Coal Board (NCB) under

Ian MacGregor in 1984. As in most of Europe, the industry was heavily subsidised. In 1982–1983, the operating loss per tonne was £3.05, and international market prices for coal were about 25% cheaper than that charged by the NCB. The calculation of these operating losses was disputed, with the Marxist historian

John Saville declaring costs other than operating losses were included in the data as part of a scheme to undermine trade unions.

By 1984, the richest seams of coal had been increasingly worked out and the remaining coal was more and more expensive to reach. The solution was mechanisation and greater efficiency per worker, making many miners redundant due to overcapacity of production.

The industry was restructured between 1958 and 1967 in cooperation with the unions, with a halving of the workforce; offset by government and industry initiatives to provide alternative employment. Stabilisation occurred between 1968 and 1977, when closures were minimised with the support of the unions even though the broader economy slowed. The accelerated contraction imposed by Thatcher after 1979 was strenuously opposed by the unions. In the

post-war consensus

The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in 1945 to the ...

, policy allowed for closures only where agreed to by the workers, who in turn received guaranteed economic security. Consensus did not apply when closures were enforced and redundant miners had severely limited employment alternatives.

The NUM's

strike in 1974 played a major role in bringing down

Edward Heath's Conservative government. The party's response was the

Ridley Plan The Ridley Plan (also known as the Ridley Report) was a 1977 report on the nationalised industries in the UK. The report was produced in the aftermath of the Heath government's being brought down by the 1973–74 coal strike.

It was drawn up by ...

, an internal report that was leaked to ''

The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

'' magazine and appeared in its 27 May 1978 issue. Ridley described how a future Conservative government could resist and defeat a major strike in a nationalised industry. In Ridley's opinion, trade union power in the UK was interfering with market forces, pushing up inflation, and the unions' undue political power had to be curbed to restore the UK's economy.

National Union of Mineworkers

The mining industry was effectively a

closed shop

A pre-entry closed shop (or simply closed shop) is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times to remain employed. This is different fro ...

. Although not official policy, employment of non-unionised labour would have led to a mass walkout of mineworkers.

The

National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) came into being in 1945 and in 1947 most collieries in Britain were nationalised (958 nationalised, 400 private).

Demand for coal was high in the years following the Second World War, and Polish refugees were drafted to work in the pits.

Over time, coal's share in the energy market declined relative to oil and nuclear.

Large-scale closures of collieries occurred in the 1960s, which led to migration of miners from the run-down coalfields (Scotland, Wales, Lancashire, the north-east of England) to Yorkshire and the Midlands coalfields.

After a period of inaction from the NUM leadership over employment cuts, there was an

unofficial strike in 1969, after which many more militant candidates were elected to NUM leadership.

The threshold for endorsement of strike action in a national ballot was reduced from two-thirds in favour to 55% in 1971.

There was then success in the

national strike in 1972, an overtime ban, and the subsequent

strike in 1974 (which led to the

Three-Day Week

The Three-Day Week was one of several measures introduced in the United Kingdom in 1973–1974 by Edward Heath's Conservative government to conserve electricity, the generation of which was severely restricted owing to industrial action by coal ...

).

The NUM's success in bringing down the Heath government demonstrated its power, but it caused resentment at their demand to be treated as a special case in wage negotiations.

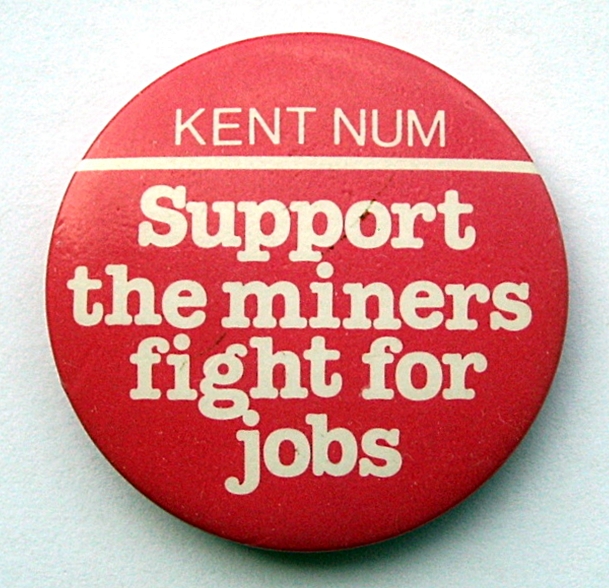

The NUM had a decentralised regional structure and certain regions were seen as more militant than others. Scotland, South Wales and Kent were militant and had some communist officials, whereas the Midlands were much less militant.

The only nationally coordinated actions in the 1984–1985 strike were the mass pickets at

Orgreave.

In the more militant mining areas, strikebreakers were reviled and never forgiven for betraying the community. In 1984, some

pit villages had no other industries for many miles around.

In

South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, miners showed a high degree of solidarity, as they came from isolated villages where most workers were employed in the pits, had similar lifestyles, and had an evangelical religious style based on Methodism that led to an ideology of egalitarianism. The dominance of mining in these local economies led Oxford professor

Andrew Glyn

Hon. Andrew John Glyn (30 June 1943 – 22 December 2007) was an English economist, University Lecturer in Economics at the University of Oxford and Fellow and Tutor in Economics in Corpus Christi College. A Marxian economist, his research int ...

to conclude that no pit closure could be beneficial for government revenue.

From 1981, the NUM was led by

Arthur Scargill, a militant trade unionist and socialist, with strong leanings towards communism.

[:: Q: could you tell us how you became a militant trade unionist?: A: Well, my initiation wasn't in the trade union at all. It was in the political movement ..So that was my initial introduction into socialism and into political militancy."] Scargill was a vocal opponent of Thatcher's government. In March 1983, he stated "The policies of this government are clear – to destroy the coal industry and the NUM". Scargill wrote in the NUM journal ''The Miner'': "Waiting in the wings, wishing to chop us to pieces, is Yankee steel butcher MacGregor. This 70-year-old multi-millionaire import, who massacred half the steel workforce in less than three years, is almost certainly brought in to wield the axe on pits. It's now or never for Britain's mineworkers. This is the final chance – while we still have the strength – to save our industry". On 12 May 1983, in response to being questioned on how he would respond if the Conservatives were re-elected in the

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

, Scargill replied: "My attitude would be the same as the attitude of the working class in Germany when the Nazis came to power. It does not mean that because at some stage you elect a government that you tolerate its existence. You oppose it".

[Paul Routledge, "Tories likened to Nazis", ''The Times'' (13 May 1983), p. 1.] He also said he would oppose a second-term Thatcher government "as vigorously as I possibly can".

After the election, Scargill called for

extra-parliamentary action against the Conservative government in a speech to the NUM conference in Perth on 4 July 1983:

"A fight back against this Government's policies will inevitably take place outside rather than inside Parliament. When I talk about 'extra-parliamentary action' there is a great outcry in the press and from leading Tories about my refusal to accept the democratic will of the people. I am not prepared to accept policies elected by a minority of the British electorate. I am not prepared quietly to accept the destruction of the coal industry, nor am I willing to see our social services decimated. This totally undemocratic Government can now easily push through whatever laws it chooses. Faced with possible parliamentary destruction of all that is good and compassionate in our society, extra-parliamentary action will be the only course open to the working class and the Labour movement."

Scargill also rejected the idea that pits that did not make a profit were "uneconomic": he claimed there was no such thing as an uneconomic pit and argued that no pits should close except due to geological exhaustion or safety.

National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers

No mining could legally be done without being overseen by an overman or deputy.

Their union, the

National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS) with 17,000 members in 1984, was less willing to take industrial action.

Its constitution required a two-thirds majority for a national strike.

During the 1972 strike, violent confrontations between striking NUM and non-striking NACODS members led to an agreement that NACODS members could stay off work without loss of pay if they were faced with aggressive picketing.

Thus solidarity with striking NUM members could be shown by claims of violence preventing the crossing of picket lines even without a NACODS union vote for strike action. Initially the threshold for striking was not met; although a majority had voted for strike action, it was not enough. However, later during the strike 82% did vote for strike action.

Sequence of events

Calls for action

In January 1981, the Yorkshire area of the NUM held a successful ballot to approve strike action over any pit threatened with closure on economic grounds.

This led to a two-week local strike over the closure of

Orgreave Colliery

Orgreave Colliery was a coal mine situated adjacent to the main line of the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway

about east of Sheffield and south west of Rotherham. The colliery is within the parish of Orgreave, from which it takes ...

, but the ballot result was later invoked to justify strikes over other closures, including

Cortonwood

Cortonwood was a colliery near Rotherham, South Yorkshire, England. The colliery's proposed closure was a tipping point in the 1984-85 miners' strike. The site is now a shopping and leisure centre.

History

Cortonwood colliery was sunk in 1873 ...

in 1984.

In February 1981, the government announced plans to close 23 pits across the country but the threat of a national strike was enough to force a back down. Coal stocks would last only six weeks, after which Britain would shut down and people would demand concessions. Thatcher realised she needed at least a six-month supply of coal to win a strike.

In 1982, NUM members accepted a 9.3% pay rise, rejecting their leaders' call for a strike.

Most pits proposed for closure in 1981 were closed on a case-by-case basis by the colliery review procedure, and the NCB cut employment by 41,000 between March 1981 and March 1984.

The effect of closures was lessened by transfers to other pits and the opening up of the

Selby Coalfield

Selby coalfield (also known as the Selby complex, or Selby 'superpit') was a large-scale deep underground mine complex based around Selby, North Yorkshire, England, with pitheads at ''Wistow Mine'', ''Stillingfleet Mine'', ''Riccall Mine'', ''Nor ...

where working conditions and wages were relatively favourable.

Localised strikes occurred at Kinneil Colliery in Scotland and

Lewis Merthyr Colliery

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...

in Wales.

The industry's Select Committee heard that 36,040 of the 39,685 redundancies between 1973 and 1982 were of men aged 55 and over, and redundancy pay was increased substantially in 1981 and 1983.

The NUM balloted its members for national strikes in January 1982, October 1982 and March 1983 regarding pit closures and restrained wages and each time a minority voted in favour, well short of the required 55% majority.

In protest at a pay offer of 5.2%, the NUM instituted an overtime ban in November 1983, which remained in place at the onset of the strike.

Thatcher's strategy

Thatcher expected Scargill to force a confrontation, and in response she set up a defence in depth.

She believed that the excessive costs of increasingly inefficient collieries had to end in order to grow the economy. She planned to close inefficient pits and depend more on imported coal, oil, gas and nuclear. She appointed hardliners to key positions, set up a high level planning committee, and allocated funds from the highly profitable electrical supply system to stockpile at least six months’ worth of coal. Thatcher's team set up mobile police units so that forces from outside the strike areas could neutralise efforts by flying pickets to stop the transport of coal to power stations. It used the National Recording Centre (NRC), set up in 1972 by the Association of Chief Police Officers for England and Wales linking 43 police forces to enable police forces to travel to assist in major disturbances. Scargill played into her hands by ignoring the buildup of coal stocks and calling the strike at the end of winter when demand for coal was declining.

In 1983, Thatcher appointed Ian MacGregor to head the National Coal Board. He had turned the

British Steel Corporation from one of the least efficient steel-makers in Europe to one of the most efficient, bringing the company into near profit.

Success was achieved at the expense of halving the workforce in two years and he had overseen a 14-week national strike in 1980. His tough reputation raised expectations that coal jobs would be cut on a similar scale and confrontations between MacGregor and Scargill seemed inevitable.

Debate over a national ballot

On 19 April 1984 a Special National Delegate Conference was held where there was a vote on whether to hold a national ballot or not. The NUM delegates voted 69–54 not to have a national ballot,

a position argued for by Arthur Scargill. Scargill states: "Our special conference was held on 19 April.

McGahey,

Heathfield and I were aware from feedback that a slight majority of areas favoured the demand for a national strike ballot; therefore, we were expecting and had prepared for that course of action with posters, ballot papers and leaflets. A major campaign was ready to go for a "Yes" vote in a national strike ballot."

McGahey said: "We shall not be constitutionalised out of a strike...Area by area will decide and there will be a domino effect".

Without a national ballot, most miners in

Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

,

Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

,

South Derbyshire

South Derbyshire is a local government district in Derbyshire, England. The population of the local authority at the 2011 Census was 94,611. It contains a third of the National Forest, and the council offices are in Swadlincote. The district a ...

,

North Wales

, area_land_km2 = 6,172

, postal_code_type = Postcode

, postal_code = LL, CH, SY

, image_map1 = Wales North Wales locator map.svg

, map_caption1 = Six principal areas of Wales common ...

and the

West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

kept on working during the strike, along with a sizeable minority in

Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

. The police provided protection for working miners from aggressive picketing.

Pit closures announced

On 6 March 1984, the NCB announced that the agreement reached after the 1974 strike was obsolete, and that to reduce government subsidies, 20 collieries would close with a loss of 20,000 jobs. Many communities in

Northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, Scotland and Wales would lose their primary source of employment.

Scargill said the government had a long-term strategy to close more than 70 pits. The government denied the claim and MacGregor wrote to every NUM member claiming Scargill was deceiving them and there were no plans to close any more pits than had already been announced. Cabinet papers released in 2014 indicate that MacGregor wished to close 75 pits over a three-year period. Meanwhile, the Thatcher government had prepared against a repeat of the effective 1974 industrial action by stockpiling coal, converting some power stations to burn heavy fuel oil, and recruiting fleets of road hauliers to transport coal in case sympathetic railwaymen went on strike to support the miners.

Action begins

Sensitive to the impact of proposed closures, miners in various coalfields began strike action. In

Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, miners at

Manvers

Manvers is a suburb of Wath upon Dearne in the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, England. It lies across the border with the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster, whilst Mexborough is part of Doncaster. It is situated between Mexb ...

,

,

Silverwood

Silverwood Theme Park is an amusement park located in the city of Athol in northern Idaho, United States, near the town of Coeur d'Alene, approximately from Spokane, Washington on US 95. Owner Gary Norton opened the park on June 20, 198 ...

,

Kiveton Park

Kiveton Park is a village within the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham, in South Yorkshire, England. Historically a part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, from the Norman conquest to 1868, Kiveton was a hamlet of the parish of Harthill-with- ...

and

Yorkshire Main were on unofficial strike for other issues before official action was called. More than 6,000 miners were on strike from 5 March at

Cortonwood

Cortonwood was a colliery near Rotherham, South Yorkshire, England. The colliery's proposed closure was a tipping point in the 1984-85 miners' strike. The site is now a shopping and leisure centre.

History

Cortonwood colliery was sunk in 1873 ...

and Bullcliffe Wood, near Wakefield.

Neither pit's reserves were exhausted. Bullcliffe Wood had been under threat, but Cortonwood had been considered safe. Action was prompted on 5 March by the NCB's announcement that five pits would be subject to "accelerated closure" in just five weeks; the other three were

Herrington

Herrington is an area in the south of Sunderland, lying within historic County Durham in North East England.

''The Herringtons'' are split into ''East & Middle'' and ''West'' and ''New'' villages. East and Middle Herrington is now a largely re ...

in County Durham,

Snowdown

Snowdown is a hamlet near Dover in Kent, England. It was the location of one of the four chief collieries of the Kent coalfield, which closed in 1987.

The population of the village is included in the civil parish of Aylesham, Kent. As a result, ...

in Kent and

Polmaise

Fallin () is a village in the Stirling council area of Scotland. It lies on the A905 road 3 miles east of Stirling on a bend in the River Forth. The United Kingdom Census 2001 recorded the population as 2,710.

It was formerly a pit village ...

in Scotland. The next day, pickets from Yorkshire appeared at pits in Nottinghamshire and

Harworth Colliery

Harworth Colliery was a colliery near the town of Harworth Bircotes in Bassetlaw, Nottinghamshire, England.

It was abandoned in 2006 due to troubles at the seam. UK Coal, who owned and maintained the mine, were waiting for a contract to make ...

closed after a mass influx of pickets amid claims that Nottinghamshire was "

scabland in 1926".

On 12 March 1984, Scargill declared the NUM's support for the regional strikes in Yorkshire and Scotland, and called for action from NUM members in all other areas but decided not to hold a nationwide vote which was used by his opponents to delegitimise the strike.

Picketing

The strike was almost universally observed in

South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

,

Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

,

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

,

North East England

North East England is one of nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. The region has three current administrative levels below the region level in the region; combined authority, unitary authorit ...

and

Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, but there was less support across the

Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

and in North Wales. Nottinghamshire became a target for aggressive and sometimes violent picketing as Scargill's pickets tried to stop local miners from working.

Lancashire miners were reluctant to strike, but most refused to cross picket lines formed by the Yorkshire NUM.

Picketing in Lancashire was less aggressive and is credited with a more sympathetic response from the local miners.

The '

Battle of Orgreave' took place on 18 June 1984 at the Orgreave Coking Plant near

Rotherham

Rotherham () is a large minster and market town in South Yorkshire, England. The town takes its name from the River Rother which then merges with the River Don. The River Don then flows through the town centre. It is the main settlement of ...

, which striking miners were attempting to blockade. The confrontation, between about 5,000 miners and the same number of police, broke into violence after police on

horseback

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, driving, and vaulting. This broad description includes the ...

charged with

truncheons drawn – 51 picketers and 72 policemen were injured. Other less well known, but bloody, battles between pickets and police took place, for example, in

Maltby, South Yorkshire.

During the strike, 11,291 people were arrested, mostly for breach of the peace or obstructing roads whilst picketing, of whom 8,392 were charged and between 150 and 200 were imprisoned.

At least 9,000 mineworkers were dismissed after being arrested whilst picketing even when no charges were brought.

After the 1980 steel strike, many hauliers

blacklisted

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

drivers who refused to cross picket lines to prevent them obtaining work, and so more drivers crossed picket lines in 1984–1985 than in previous disputes.

Picketing failed to have the widespread impact of earlier stoppages that led to

blackouts and power cuts in the 1970s and electricity companies maintained supplies throughout the winter, the time of biggest demand.

From September, some miners returned to work even where the strike had been universally observed. It led to an escalation of tension, and riots in

Easington in Durham

and

Brampton Bierlow in Yorkshire.

Strike ballots by NACODS

In April 1984, NACODS voted to strike but was short of the two-thirds majority that their constitution required.

In areas where the strike was observed, most NACODS members did not cross picket lines and, under an agreement from the 1972 strike, stayed off work on full pay.

When the number of strikebreakers increased in August, Merrick Spanton, the NCB personnel director, said he expected NACODS members to cross picket lines to supervise their work threatening the 1972 agreement which led to a second ballot.

MacGregor suggested that deputies could be replaced by outsiders as

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

had done during the

1981 airline strike. In September, for the first time, NACODS voted to strike with a vote of 81% in favour.

The government then made concessions over the review procedure for unprofitable collieries, much to the anger of MacGregor, and a deal negotiated by North Yorkshire NCB Director Michael Eaton persuaded NACODS to call off the strike action.

The results of the review procedure were not binding on the NCB, and the NUM rejected the agreement.

Reviews for Cadeby in Yorkshire and Bates in Northumberland concluded that the pits could stay open but the NCB overruled and closed them.

The abandonment of strike plans when most of their demands had not been met led to conspiracy theories on the motives of NACODS leaders.

MacGregor later admitted that if NACODS had gone ahead with a strike, a compromise would probably have been forced on the NCB. Files later made public showed that the government had an informant inside the

Trades Union Congress (TUC), passing information about negotiations.

In 2009, Scargill wrote that the settlement agreed with NACODS and the NCB would have ended the strike and said, "The monumental betrayal by NACODS has never been explained in a way that makes sense."

Court judgments on legality of strike

In the first month of the strike, the NCB secured a court injunction to restrict picketing in Nottinghamshire, but the

Energy Minister,

Peter Walker forbade MacGregor from invoking it as the government considered it would antagonise the miners and unite them behind the NUM.

Legal challenges were brought by groups of working miners, who subsequently organised as the Working Miners' Committee.

David Hart, a farmer and property developer with libertarian political beliefs, did much to organise and fund working miners.

On 25 May, a writ issued in the High Court by Colin Clark from Pye Hill Colliery, sponsored by Hart, was successful in forbidding the Nottinghamshire area from instructing that the strike was official and to be obeyed.

Similar actions were successful in Lancashire and South Wales.

In September,

Lord Justice Nicholls heard two cases, in the first, North Derbyshire miners argued that the strike was illegal both at area level, as a majority of its miners had voted against, and at national level, as there had been no ballot. In the second, two miners from

Manton Colliery, in the Yorkshire area but geographically in North Nottinghamshire, argued that the area-level strike in Yorkshire was illegal. Miners at Manton had overwhelmingly voted against the strike, but police had advised that their safety could not be guaranteed.

The NUM was not represented at the hearing.

The

High Court ruled that the NUM had breached its constitution by calling a strike without holding a ballot.

Although Nicholls did not order the NUM to hold a ballot, he forbade the union from disciplining members who crossed picket lines.

The strike in Yorkshire relied on a ballot from January 1981, in which 85.6% of the members voted to strike if any pit was threatened with closure on economic grounds.

The motion was passed with regard to the closure of Orgreave Colliery, which prompted a two-week strike.

The NUM executive approved the decision in Yorkshire to invoke the ballot result as binding on 8 March 1984.

Nicholls ruled that the 1981 ballot result was "too remote in time

ith.. too much change in the branch membership of the Area since then for that ballot to be capable of justifying a call to strike action two and a half years later."

He ruled that the Yorkshire area could not refer to the strike as "official", although he did not condemn the strike as "illegal" as he did in the case of the national strike and the North Derbyshire strike.

Scargill referred to the ruling as "another attempt by an unelected judge to interfere in the union's affairs."

He was fined £1,000 (paid by an anonymous businessman), and the NUM was fined £200,000. When the union refused to pay, an order was made to

sequester the union's assets, but they had been transferred abroad.

In October 1984, the NUM executive voted to cooperate with the court to recover the funds, despite opposition from Scargill, who stated in court that he was only apologising for his contempt of court because the executive voted for him to do so.

By the end of January 1985, around £5 million of NUM assets had been recovered.

A

Court of Session

The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland and constitutes part of the College of Justice; the supreme criminal court of Scotland is the High Court of Justiciary. The Court of Session sits in Parliament House in Edinburgh ...

decision in Edinburgh ruled that Scottish miners had acted within their rights by taking local ballots on a show of hands and so union funds in Scotland could not be sequestered. "During the strike, the one area they couldn't touch was Scotland. They were sequestering the NUM funds, except in Scotland, because the judges deemed that the Scottish area had acted within the rules of the Union" –

David Hamilton MP, Midlothian.

Scargill claims "It was essential to present a united response to the NCB and we agreed that, if the coal board planned to force pit closures on an area by area basis, then we must respond at least initially on that same basis. The NUM's rules permitted areas to take official strike action if authorised by our national executive committee in accordance with Rule 41."

Breakaway union

The Nottinghamshire NUM supported the strike, but most of its members continued to work and many considered the strike unconstitutional given their majority vote against a strike and absence of a ballot for a national strike.

As many working miners felt the NUM was not doing enough to protect them from intimidation from pickets, a demonstration was organised on May Day in

Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market tow ...

, in which the representative Ray Chadburn was shouted down, and fighting ensued between protesters for and against the strike.

In NUM elections in summer 1984, members in Nottinghamshire voted out most of the leaders who had supported the strike, so that 27 of 31 newly elected were opposed to the strike.

The Nottinghamshire NUM then opposed the strike openly and stopped payments to local strikers.

The national NUM attempted to introduce "Rule 51", to discipline area leaders who were working against national policy.

The action was nicknamed the "star chamber court" by working miners (in reference to the

Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judic ...

in English history).

It was prevented by an injunction from the High Court.

Working miners in Nottinghamshire and South Derbyshire set up a new union: the

Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM).

It attracted members from many isolated pits in England – including

Agecroft

Agecroft is a suburban area of Pendlebury, within the City of Salford, Greater Manchester, England. It lies within the Irwell Valley, on the west bank of the River Irwell and along the course of the Manchester, Bolton & Bury Canal. It compris ...

and

Parsonage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically own ...

in Lancashire, Chase Terrace and Trenton Workshops in Staffordshire, and

Daw Mill in Warwickshire.

Although most Leicestershire miners continued working, they voted to stay in the NUM.

Unlike Nottinghamshire, the leadership in Leicestershire never attempted to enforce the strike,

and an official, Jack Jones, had publicly criticised Scargill.

At some pits in Nottinghamshire – Ollerton, Welbeck and Clipstone – roughly half the workforce stayed in the NUM.

The TUC neither recognised nor condemned the new union.

The UDM was eventually ''de facto'' recognised when the NCB included it in wage negotiations.

MacGregor strongly encouraged the UDM.

He announced that NUM membership was no longer a prerequisite for mineworkers' employment, ending the closed shop.

The formal end

The number of strikebreakers, sometimes referred to pejoratively as ''scabs'', increased from the start of January, as the strikers struggled to pay for food as union pay ran out.

They were not treated with the same contempt by strikers as those who had returned to work earlier, but in some collieries, fights broke out between hunger scabs who had been active pickets, and those who had broken the strike earlier.

The strike ended on 3 March 1985, nearly a year after it had begun. The South Wales area called for a return to work on condition that men sacked during the strike would be reinstated, but the NCB rejected the proposal when its bargaining position was improved by miners returning to work.

Only the Yorkshire and Kent regions voted against ending the strike.

One of the few concessions made by the NCB was to postpone the closure of the five pits: Cortonwood, Bullcliffe Wood,

Herrington

Herrington is an area in the south of Sunderland, lying within historic County Durham in North East England.

''The Herringtons'' are split into ''East & Middle'' and ''West'' and ''New'' villages. East and Middle Herrington is now a largely re ...

, Polmaise and Snowdown.

The issue of sacked miners was important in Kent, where several men had been sacked for a sit-in at

Betteshanger Colliery. Kent NUM leader Jack Collins said after the decision to go back without any agreement of amnesty for the sacked men, "The people who have decided to go back to work and leave men on the sidelines are traitors to the trade-union movement."

The Kent NUM continued picketing across the country, delaying the return to work at many pits for two weeks.

Some sources claim that the Scottish NUM continued the strike alongside Kent.

At several pits, miners' wives groups organised the distribution of

carnations, the flower that symbolises the hero, at the pit gates on the day the miners went back. Many pits marched back to work behind

brass bands, in processions dubbed "loyalty parades". Scargill led a procession accompanied by a Scots piper, back to work at

Barrow Colliery in

Worsborough

Worsbrough is an area about two miles south of Barnsley in the metropolitan borough of Barnsley, South Yorkshire, England. Before 1974, Worsbrough had its own urban district council in the West Riding of the historic county of Yorkshire and i ...

but then it was stopped by a picket of Kent miners. Scargill said, "I never cross a picket line," and turned the procession away.

Issues

Ballots

The role of ballots in NUM policy had been disputed over a number of years, and a series of legal disputes in 1977 left their status unclear. In 1977, the implementation of an incentive scheme proved controversial, as different areas would receive different pay rates. After the NUM's National Executive Conference rejected the scheme, NUM leader

Joe Gormley arranged a national ballot. The Kent area who opposed the scheme sought a court injunction to prevent it, but

Lord Denning ruled that "the conference might not have spoken with the true voice of all the members and in his view a ballot was a reasonable and democratic proposal". The scheme was rejected by 110,634 votes to 87,901. The Nottinghamshire, South Derbyshire and Leicestershire areas resolved to adopt the incentive scheme as their members would benefit from increased pay. The Yorkshire, Kent and South Wales areas sought an injunction to prevent these actions on the grounds of the ballot result.

Mr. Justice Watkins ruled that, "The result of a ballot, nationally conducted, is not binding upon the National Executive Committee in using its powers in between conferences. It may serve to persuade the committee to take one action or another, or to refrain from action, but it has no great force or significance."

Scargill did not call a ballot for national strike action, perhaps due to uncertainty over the outcome. Instead, he started the strike by allowing each region to call its own strikes, imitating Gormley's strategy over wage reforms; it was argued that 'safe' regions should not be allowed to ballot other regions out of jobs. The decision was upheld by a vote by the NUM executive five weeks into the strike.

The NUM had held three ballots on national strikes: 55% voted against in January 1982, and 61% voted against in October 1982 and March 1983.

Before the March 1983 vote, the Kent area, one of the most militant, argued for national strikes to be called by conferences of delegates rather than by ballot, but the proposal was rejected.

As the strike began in 1984 with unofficial action in Yorkshire, there was pressure from strikers to make it official, and NUM executives who insisted on a ballot were attacked by pickets at an executive meeting in Sheffield in April.

In contrast, a sit-in down the pit was held by supporters of a ballot at

Hem Heath

Hem Heath is a village in Stoke-on-Trent just south of the Bet365 Stadium.

The nature reserve Hem Heath Woods

Hem Heath Woods is a nature reserve of the Staffordshire Wildlife Trust.

It is on the southern fringe of Stoke-on-Trent, England. Its ...

in

Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

.

Although the Yorkshire area had a policy of opposing a national ballot, there was support for a ballot expressed by Yorkshire branches at

Glasshoughton

Glasshoughton is a neighbourhood of Castleford in West Yorkshire, England, that borders on Pontefract. The appropriate Wakefield ward is called Castleford Central and Glasshoughton. It is home to the Xscape leisure centre and ski slope, the J ...

,

,

Shireoaks

Shireoaks is a former pit village and civil parish in Nottinghamshire, located between Worksop and Thorpe Salvin on the border with South Yorkshire. The population of the civil parish was 1,432 at the 2011 census. Shireoaks colliery was opene ...

and

Kinsley.

Two polls by

MORI in April 1984 found that the majority of miners supported a strike.

Ken Livingstone

Kenneth Robert Livingstone (born 17 June 1945) is an English politician who served as the Leader of the Greater London Council (GLC) from 1981 until the council was abolished in 1986, and as Mayor of London from the creation of the office i ...

wrote in his memoirs that Scargill had interpreted a ''

Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' poll that suggested a comfortable majority of miners favoured a national strike to be a trick and that he would actually lose a national ballot.

In ballots in South Wales on 10 March 1984, only 10 of the 28 pits voted in favour of striking, but the arrival of pickets from Yorkshire the next day led to virtually all miners in South Wales going on strike in solidarity.

The initial vote against strike action by most lodges in South Wales was interpreted as an act of retaliation for a lack of support from Yorkshire in years when numerous pits in Wales were closing, especially following the closure of the Lewis Merthyr colliery in March 1983 and only 54% of Yorkshire miners voting for a national strike that month, a full 14% below the vote for a national strike in both South Wales and Kent.

Area ballots on 15 and 16 March 1984 saw verdicts against a strike in Cumberland, Midlands, North Derbyshire (narrowly), South Derbyshire, Lancashire, Leicestershire (with around 90% against), Nottinghamshire and North Wales.

The Northumberland NUM voted by a small majority in favour, but below the 55% needed for official approval.

NUM leaders in Lancashire argued that, as 41% had voted in favour of a strike, all its members should strike "in order to maintain unity".

The Conservative government under Thatcher enforced a law that required unions to ballot members on strike action. On 19 July 1984, Thatcher said in the

House of Commons that giving in to the miners would be surrendering the rule of

parliamentary democracy to the

rule of the mob

Mob rule or ochlocracy ( el, ὀχλοκρατία, translit=okhlokratía; la, ochlocratia) is the rule of government by a mob or mass of people and the intimidation of legitimate authorities. Insofar as it represents a pejorative for majorit ...

. She referred to union leaders as "the enemy within" and claimed they did not share the values of other British people; advocates of the strike misinterpreted the quote to suggest that Thatcher had used it as a reference to all miners.

Thatcher on 19 July 1984 delivered a speech in which she spoke to backbench MPs and compared the

Falklands War

The Falklands War ( es, link=no, Guerra de las Malvinas) was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its territorial de ...

to the strike:

She claimed that the miners' leader was making the country witness an attempt at preventing democracy.

On the day after the Orgreave picket of 18 June, which saw five thousand pickets clash violently with police, she remarked:

I must tell you... that what we have got is an attempt to substitute the rule of the mob for the rule of law, and ''it must not succeed''. ''heering

Heering Cherry Liqueur is a Danish liqueur flavored with cherries. It is often referred to simply as ''Peter Heering'' or ''Cherry Heering'' in cocktail recipes. Heering Cherry Liqueur has been produced since 1818, and the company is purveyor t ...

' It must not succeed. There are those who are using violence and intimidation to impose their will on others who do not want it.... The rule of law must prevail over the rule of the mob.

Neil Kinnock supported the call for a national ballot in April 1984.

Scargill's response to the Orgreave incident was:

We've had riot shields, we've had riot gear, we've had police on horseback charging into our people, we've had people hit with truncheons and people kicked to the ground.... The intimidation and the brutality that has been displayed are something reminiscent of a Latin American state.

At the Battle of Orgreave on 18 June 1984, the NUM pickets failed to stop the movement of lorries amid police violence and subsequent retaliation by the pickets, with the footage controversially reversed by the BBC on their news broadcast. The violence was costing the NUM public support in the country as a whole, as a Gallup poll showed 79% disapproval of NUM methods. While it was now clear that the government had the equipment, the forces, the organisation, and the will to prevail against pickets, the strong pro-strike solidarity outside of the Midlands and the possibility of extended strike action by other trade unions, especially the NACODS which could shut down every pit in the country if NACODS members went on strike, was a constant threat for the government and had the outcome of who would be likely to win the miners' strike dispute hanging in the balance for many months.

The number of miners at work grew to 53,000 by late June.

Votes for strike action by area

The table shows a breakdown by area of the results of strike ballots of January 1982, October 1982 and March 1983, and the results of area ballots in March 1984. The table is taken from Callinicos & Simons (1985).

Cases from 1984 where lodges voted separately (as in South Wales and Scotland) are not shown.

Mobilisation of police

The government mobilised police forces from around Britain including the

Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

in an attempt to stop pickets preventing strikebreakers from working. They attempted to stop pickets travelling from Yorkshire to Nottinghamshire which led to many protests.

On 26 March 1984, pickets protested against the police powers by driving very slowly on the M1 and the A1 around Doncaster.

The government claimed the actions were to uphold the law and safeguard individual

civil rights. The police were given powers to halt and reroute traffic away from collieries, and some areas of Nottinghamshire became difficult to reach by road.

In the first 27 weeks of the strike, 164,508 "presumed pickets" were prevented from entering the county.

When pickets from Kent were stopped at the

Dartford Tunnel

The Dartford-Thurrock River Crossing, commonly known as the Dartford Crossing and until 1991 the Dartford Tunnel, is a major road crossing of the River Thames in England, carrying the A282 road between Dartford in Kent in the south and Thurro ...

and preventing from travelling to the Midlands, the Kent NUM applied for an injunction against use of this power.

Sir

Michael Havers

Robert Michael Oldfield Havers, Baron Havers (10 March 1923 – 1 April 1992), was a British barrister and Conservative politician. From his knighthood in 1972 until becoming a peer in 1987 he was known as Sir Michael Havers.

Early life and m ...

initially denied the application outright, but Mr Justice Skinner later ruled that the power may only be used if the anticipated breach of the peace were "in close proximity both in time and place".

On 16 July 1984, Thatcher convened a ministerial meeting to consider declaring a

state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

, with the option to use 4,500 military drivers and 1,650

tipper trucks to keep coal supplies available. This backup plan was not needed and was not implemented.

During the strike 11,291 people were arrested and 8,392 were charged with

breach of the peace or obstructing the highway. In many former mining areas antipathy towards the police remained strong for many years.

Bail forms for picketing offences set restrictions on residence and movement in relation to NCB property.

compared the powers to the racial

pass laws in South Africa.

No welfare benefit payments

Welfare benefits had never been available to strikers but their dependents had been entitled to make claims in previous disputes. Clause 6 of the

Social Security Act 1980 banned the dependents of strikers from receiving "urgent needs" payments and applied a compulsory deduction from the benefits of strikers' dependents. The government viewed the legislation not as concerned with saving public funds but "to restore a fairer bargaining balance between employers and trade unions" by increasing the necessity to return to work.

The Department of Social Security assumed that striking miners were receiving £15 per week from the union (equivalent to £49 in 2019), based on payments early in the strike that were not made in the later months when funds had become exhausted.

MI5 "counter-subversion"

The

Director General of MI5 from 1992 to 1996, Dame

Stella Rimington

Dame Stella Rimington (born 13 May 1935) is a British author and former Director General of MI5, a position she held from 1992 to 1996. She was the first female DG of MI5, and the first DG whose name was publicised on appointment. In 1993, Rimi ...

, wrote in her autobiography in 2001 that MI5 'counter-subversion' exercises against the NUM and striking miners included

tapping union leaders' phones. She denied the agency had

informers

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informan ...

in the NUM, specifically denying its chief executive

Roger Windsor

Roger Windsor was chief executive of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) between 1983 and 1989, including during the 1984 miners' strike. He later moved to France and then to Herefordshire.

Windsor was accused of damaging the image of the u ...

had been an agent.

Public opinion and the media

According to

John Campbell "though there was widespread sympathy for the miners, faced with the loss of their livelihoods, there was remarkably little public support for the strike, because of Scargill's methods".

When asked in a

Gallup poll in July 1984 whether their sympathies lay mainly with the employers or the miners, 40% said employers; 33% were for the miners; 19% were for neither and 8% did not know. When asked the same question during 5–10 December 1984, 51% had most sympathy for the employers; 26% for the miners; 18% for neither and 5% did not know.

When asked in July 1984 whether they approved or disapproved of the methods used by the miners, 15% approved; 79% disapproved and 6% did not know. When asked the same question during 5–10 December 1984, 7% approved; 88% disapproved and 5% did not know.

In July 1984, when asked whether they thought the miners were using responsible or irresponsible methods, 12% said responsible; 78% said irresponsible and 10% did not know. When asked the same question in August 1984, 9% said responsible; 84% said irresponsible and 7% did not know.

''

The Sun'' newspaper took a very anti-strike position, as did the ''

Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'', and even the Labour Party-supporting ''

Daily Mirror'' and ''

The Guardian'' became hostile as the strike became increasingly violent.

The ''

Morning Star

Morning Star, morning star, or Morningstar may refer to:

Astronomy

* Morning star, most commonly used as a name for the planet Venus when it appears in the east before sunrise

** See also Venus in culture

* Morning star, a name for the star Siri ...

'' was the only national daily newspaper that consistently supported the striking miners and the NUM.

Socialist groups saw the mainstream media as deliberately misrepresenting the miners' strike, with Mick Duncan of the

Alliance for Workers' Liberty saying of ''The Sun''s reporting of the strike: "The day-to-day reporting involved more subtle attacks, or a biased selection of facts and a lack of alternative points of view. These things arguably had a far bigger negative effect on the miners' cause".

Writing in the ''Industrial Relations Journal'' immediately after the strike in 1985, Professor Brian Towers of the

University of Nottingham commented on the way the media had portrayed strikers, stating that there had been "the obsessive reporting of the 'violence' of generally relatively unarmed men and some women who, in the end, offered no serious challenge to the truncheons, shields and horses of a well-organised, optimally deployed police force."

The stance of the ''Daily Mirror'' varied. Having initially been uninterested in the dispute, the paper's owner Robert Maxwell took a supportive stance in July 1984 by organising a seaside trip for striking miners and meeting with NUM officials to discuss tactics.

However, Maxwell insisted that Scargill should condemn the violence directed against strike-breakers, which he was unwilling to do.

The ''Daily Mirror'' then adopted a more critical stance, and journalist

John Pilger published several articles on the violence directed against strike-breakers.

NUM links with Libya and the Soviet Union

As the courts seized the NUM's assets, it began to look abroad for money, and found supplies in the Soviet bloc and, it was mistakenly thought, also from Libya. These countries were highly unpopular with the British public. The Soviet Union's official trade union federation donated £1.5 million to the NUM.

Media reports alleged that senior NUM officials were personally keeping some of the funds. In November 1984, it was alleged that senior NUM officials had travelled to Libya for money. Cash from the Libyan government was particularly damaging coming seven months after the murder of policewoman

Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan embassy in London by Libyan agents. In 1990, the ''Daily Mirror'' and TV programme ''

The Cook Report'' claimed that Scargill and the NUM had received money from the Libyan government. The allegations were based on allegations by Roger Windsor, who was the NUM official who had spoken to Libyan officials.

Roy Greenslade, the editor of the ''Mirror'', said 18 years later he was "now convinced that Scargill didn't misuse strike funds and that the union didn't get money from Libya." This was long after an investigation by

Seumas Milne

Seumas Patrick Charles Milne (born 5 September 1958)Winchester College: A Register. Edited by P.S.W.K. McClure and R.P. Stevens, on behalf of the Wardens and Fellows of Winchester College. 7th edition, 2014. pp. 582 (Short Half 1971 list heading) ...

described the allegations as wholly without substance and a "classic smear campaign".

MI5 surveillance on NUM vice-president

Mick McGahey

Michael McGahey (29 May 1925 – 30 January 1999) was a Scottish miners' leader and Communist. He had a distinctive gravelly voice, and described himself as "a product of my class and my movement".

Early life

His father, John McGahey, worked ...

found he was "extremely angry and embarrassed" about Scargill's links with the Libyan regime, but did not express his concerns publicly;

however he was happy to take money from the Soviet Union.

Stella Rimington, wrote, "We in MI5 limited our investigations to those who were using the strike for subversive purposes."

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

trade union

Solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

criticised Scargill for "going too far and threatening the elected government", which influenced some Polish miners in Britain to oppose the strike.

Scargill opposed Solidarity as an "anti-socialist organisation which desires the overthrow of a socialist state". The supply of Polish coal to British power stations during the strike led to a brief picket of the embassy of Poland in London.

Violence

The strike was the most violent industrial dispute in Britain of the 20th century.

Strikes in the British coal industry had a history of violence, but the 1984–1985 strike exceeded even the 1926 strike in the levels of violence.

Nevertheless, the majority of pickets lines were non-violent.

Instances of violence directed against working miners were reported from the start. The BBC reported that pickets from Polmaise Colliery had punched miners at

Bilston Glen Colliery who were trying to enter their workplace on 12 March. Property, families and pets belonging to working miners were also attacked.

Ted McKay, the North Wales secretary who supported a national ballot before strike action, said he had received death threats and threats to kidnap his children. The intimidation of working miners in Nottinghamshire, vandalism to cars and pelting them with stones, paint or brake fluid, was a major factor in the formation of the breakaway UDM.

Occasionally, attacks were made on working members of NACODS and administrative staff. In March 1984 the NCB announced it would abandon Yorkshire Main Colliery after a deputy engineer suffered a split chin from being stoned and administrative staff had to be escorted out by the police.

Some pits continued working without significant disruption. In Leicestershire only 31 miners went on strike for the full 12 months

and in South Derbyshire only 17, but these areas were not targeted by pickets in the same way as Nottinghamshire.

On 9 July 1984 pickets at

Rossington

Rossington is a civil parish and former mining village in the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster in South Yorkshire, England and is surrounded by countryside and the market towns of Bawtry and Tickhill.

Geography

Historically part of the West R ...

Colliery attempted to trap 11 NCB safety inspectors inside the colliery. Camera teams were present as two police vans arrived to assist the safety inspectors and were attacked by missiles from the pickets.

Following the breakdown of relations between the NUM and the ISTC (

Iron and Steel Trades Confederation), NUM pickets threw bricks, concrete and eggs full of paint at lorries transporting coal and iron ore to South Wales.

In September 1984, Viv Brook, assistant chief constable of South Wales Police, warned that throwing concrete from motorway bridges was likely to kill someone. Taxi driver,

David Wilkie, was killed on 30 November 1984 while driving a non-striking miner to

Merthyr Vale Colliery, in South Wales. Two striking miners dropped a concrete post onto his car from a road bridge and he died at the scene. The miners served a prison sentence for

manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th cen ...

. Police reported that the incident had a sobering effect on many of the pickets and led to a decrease in aggression.

In

Airedale, Castleford

Airedale is a suburb in the town of Castleford, West Yorkshire, England. It consists mainly of Local Authority Housing. It borders with Ferry Fryston. The ward of the City of Wakefield called Airedale and Ferry Fryston had a population of 14,81 ...

where most miners were on strike, a working miner, Michael Fletcher, was savagely beaten in November 1984.

A masked gang waving baseball bats invaded his house and beat him for five minutes, whilst his pregnant wife and children hid upstairs.

Fletcher suffered a broken shoulder blade, dislocated elbow and two broken ribs. Two miners from Wakefield were convicted of causing grievous bodily harm and four others were acquitted of riot and assault.

Scargill said in December 1984 that those who returned to work after taking the NCB's incentives for strikebreaking should be treated as "lost lambs" rather than traitors.

When questioned by the media, Scargill refused to condemn the violence, which he attributed to the hardship and frustration of pickets,

with the one exception being the killing of David Wilkie.

There was criticism of picket-line violence from lodges at striking pits, such as the resolution by the Grimethorpe and Kellingley lodges in Yorkshire that condemned throwing bricks.

Even amongst supporters, picketing steel plants to prevent deliveries of coal and coke caused great divisions. Local branches agreed to deals with local steel plants on the amounts to be delivered. In June 1984, the NUM area leader for South Wales, Emlyn Williams, defied orders from Scargill to stop deliveries of coal by rail to steel plants, but he capitulated after a vote by the national executive to end dispensations.

Violence in Nottinghamshire was directed towards strikers and supporters of the NUM national line. NUM secretary Jimmy Hood reported his car was vandalised and his garage set on fire.

In Leicestershire, ''scab'' was chanted by the working majority against the few who went on strike, on the grounds that they had betrayed their area's union.

Two pickets, David Jones and Joe Green, were killed in separate incidents, and three teenagers (Darren Holmes, aged 15, and Paul Holmes and Paul Womersley, both aged 14) died picking coal from a colliery waste heap in the winter. The NUM names its memorial lectures after the pickets. Jones's death raised tensions between strikers and those who continued to work. On 15 March 1984, he was hit in the chest by a half-brick thrown by a youth who opposed the strike when he confronted him for vandalising his car, but the post-mortem ruled that this had not caused his death and it was more likely to have been caused by being pressed against the pit gates earlier in the day.

News of his death led to hundreds of pickets staying in Ollerton town centre overnight.

At the request of Nottinghamshire Police, Scargill appeared and called for calm in the wake of the tragedy.

Several working miners in Ollerton reported that their gardens and cars had been vandalised during the night.

Ollerton Colliery closed for a few days as a mark of respect for Jones.

Policing was extensive from the start, a policy to avoid the problems of 1972, when the police were overwhelmed by the number of pickets at the

Battle of Saltley Gate.

Many families in South Yorkshire complained that the police were abusive and damaged property needlessly whilst pursuing pickets.

During the Battle of Orgreave, television cameras caught a policeman repeatedly lashing out at a picket on his head with a truncheon but no charges were made against the officer, identified as a member of

Northumbria Police.

The heavy-handed policing at Orgreave, including from some senior officers was criticised.

At the 1985

Police Federation conference, Ronald Carroll from West Yorkshire Police argued that, "The police were used by the Coal Board to do all their dirty work. Instead of seeking the civil remedies under the existing civil law, they relied completely on the police to solve their problems by implementing the criminal law."

A motion at the 1984 Labour Party conference won heavy support for blaming all the violence in the strike on the police, despite opposition from Kinnock.

Fundraising

Union funds struggled to cover the year-long strike, so strikers had to raise their own funds. The Kent area's effective fundraising from sympathisers in London and in continental Europe was resented by other areas.

The Yorkshire area's reliance on mass picketing led to a neglect of fundraising, and many Yorkshire strikers were living in poverty by the winter of 1984.

A soup kitchen opened in Yorkshire in April 1984, for the first time since the 1920s.

Wakefield Council provided free meals for children during school holidays.

The Labour-dominated councils of Barnsley, Doncaster, Rotherham and Wakefield reduced council-house rents and local tax rates for striking miners, but the Conservative Selby Council refused any assistance, although the Selby pits had higher numbers of commuters.

In Leicestershire, the area's NUM made no payments to the few who went on strike, on the grounds that the area had voted against industrial action.

[BBC Leicester – History – On Strike in Leicestershire](_blank)

, published 24 February 2009. Fundraising for the so-called "Dirty Thirty" striking Leicestershire miners was extensive and they redirected some of their excess aid to other parts of the NUM.

Many local businesses in pit villages donated money to NUM funds, although some claimed they were threatened with boycotts or vandalism if they did not contribute.

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) was an alliance of lesbians and gay men who supported the National Union of Mineworkers during the year-long strike of 1984–1985. By the end of the strike, eleven LGSM groups had emerged in the UK ...

held "Pits and Perverts" concerts to raise money which led the NUM to become supportive of

gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

in subsequent years.

Some groups prioritised aid to pits in South Wales, as they felt that Scargill was distributing donations to his most favoured pits in Kent and Yorkshire. The ISTC donated food parcels and toys during the summer, but gave no money as they did not want to be accused of financing the aggressive picketing.

Chesterfield FC