Zen (; from Chinese: ''

Chán

Chan (; of ), from Sanskrit '' dhyāna'' (meaning "meditation" or "meditative state"), is a Chinese school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. It developed in China from the 6th century CE onwards, becoming especially popular during the Tang and Song d ...

''; in Korean: ''Sŏn'', and Vietnamese: ''Thiền'') is a Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

during the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

by blending Indian

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism, the others being Thera ...

, particularly Yogacara and Madhyamaka philosophies, with Chinese Taoist thought, especially

Neo-Daoist. Zen originated as the

Chan School (禪宗, ''chánzōng'', 'meditation school') or the

Buddha-mind school (佛心宗'', fóxīnzōng''), and later developed into various sub-schools and branches.

Chan is traditionally believed to have been brought to China by the semi-legendary figure

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and is regarded as its first Chinese Lineage (Buddhism), patriarch. ...

, an Indian (or Central Asian) monk who is said to have introduced dhyana teachings to China. From China, Chán spread south to

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

and became

Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to

Korea

Korea is a peninsular region in East Asia consisting of the Korean Peninsula, Jeju Island, and smaller islands. Since the end of World War II in 1945, it has been politically Division of Korea, divided at or near the 38th parallel north, 3 ...

to become

Seon Buddhism, and east to

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, becoming

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

.

Zen emphasizes

meditation practice, direct insight into one's own

Buddha nature

In Buddhist philosophy and Buddhist paths to liberation, soteriology, Buddha-nature (Chinese language, Chinese: , Japanese language, Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all Sentient beings (Buddhism), sentient beings to bec ...

(見性, Ch. ''jiànxìng,'' Jp. ''

kenshō

Kenshō (Rōmaji; Japanese and classical Chinese: 見性, Pinyin: ''jianxing'', Sanskrit: dṛṣṭi- svabhāva) is an East Asian Buddhist term from the Chan / Zen tradition which means "seeing" or "perceiving" ( 見) "nature" or "essence" ...

''), and the personal expression of this insight in daily life for

the benefit of others. Some Zen sources de-emphasize doctrinal study and traditional practices, favoring direct understanding through

zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

and interaction with a master (Jp:

rōshi

(Japanese language, Japanese: "old teacher"; "old master") is a title in Zen Buddhism with different usages depending on sect and country. In Rinzai Zen, the term is reserved only for individuals who have received ''inka shōmei'', meaning the ...

, Ch:

shīfu) who may be depicted as an iconoclastic and unconventional figure. In spite of this, most Zen schools also promote traditional Buddhist practices like chanting,

precepts,

walking meditation

Walking meditation ( Chinese: 經行; Pinyin: ''jīngxíng''; Romaji: ''kinhin'' or ''kyōgyō''; Korean: ''gyeonghyaeng''; Vietnamese: ''kinh hành'') is a meditation practice done while walking common in Buddhism. It can be done as a standalo ...

, rituals,

monasticism

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Chr ...

and scriptural study.

With an emphasis on

Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

thought,

intrinsic enlightenment and

sudden awakening

Sudden awakening or Sudden enlightenment (), also known as subitism, is a Buddhist idea which holds that practitioners can achieve an instantaneous insight into ultimate reality (Buddha-nature, or the nature of mind). This awakening is describe ...

, Zen teaching draws from numerous Buddhist sources, including

Sarvāstivāda

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (; ;) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (third century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy in the First Millennium CE, 2018, p. 60. It was particularl ...

meditation, the Mahayana teachings on the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person who has attained, or is striving towards, '' bodhi'' ('awakening', 'enlightenment') or Buddhahood. Often, the term specifically refers to a person who forgoes or delays personal nirvana or ''bodhi'' in ...

,

Yogachara

Yogachara (, IAST: ') is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation, as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). ...

and

Tathāgatagarbha texts (like the

Laṅkāvatāra), and the

Huayan school

The Huayan school of Buddhism (, Wade–Giles: ''Hua-Yen,'' "Flower Garland," from the Sanskrit "''Avataṃsaka''") is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist tradition that developed in China during the Tang dynasty, Tang dynasty (618-907).Yü, Chün-fan ...

. The

Prajñāpāramitā

A Tibetan painting with a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra at the center of the mandala

Prajñāpāramitā means "the Perfection of Wisdom" or "Transcendental Knowledge" in Mahāyāna. Prajñāpāramitā refers to a perfected way of seeing the natu ...

literature, as well as

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

thought, have also been influential in the shaping of the

apophatic and sometimes

iconoclastic

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

nature of Zen

rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

.

Etymology

The word ''Zen'' is derived from the

Japanese pronunciation (

kana

are syllabary, syllabaries used to write Japanese phonology, Japanese phonological units, Mora (linguistics), morae. In current usage, ''kana'' most commonly refers to ''hiragana'' and ''katakana''. It can also refer to their ancestor , wh ...

: ぜん) of the

Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese language, Chinese recorded in the ''Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expande ...

word 禪 (

Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese language, Chinese recorded in the ''Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expande ...

:

ʑian zh, p=Chán), which in turn is derived from the

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

word ''

dhyāna'' (ध्यान), which can be approximately translated as 'contemplation', 'absorption', or '

meditative state'.

The actual Chinese term for the "Zen school" is 禪宗 ( zh, p=Chánzōng), while "Chan" just refers to the practice of meditation itself ( zh, s=習禪, p=xíchán) or the study of meditation ( zh, s=禪學, p=chánxué) though it is often used as an abbreviated form of ''Chánzong''.

Zen is also called 佛心宗, ''fóxīnzōng'' (Chinese) or ''busshin-shū'' (Japanese), the "Buddha-mind school", from ''fó-xīn'', 'Buddha-mind';

"this term can refer either to the (or a)

Buddha's compassionate and enlightened mind, or to the originally

clear and pure mind inherent in all beings to which they must awaken."

''Busshin'' may also refer to ''

Buddhakaya'', the Buddha-body,

"an embodiment of awakened activity".

"Zen" is traditionally a proper noun as it usually describes a particular Buddhist sect. In more recent times, the lowercase "zen" is used when discussing a worldview or attitude that is "peaceful and calm". It was officially added to the

Merriam-Webster

Merriam-Webster, Incorporated is an list of companies of the United States by state, American company that publishes reference work, reference books and is mostly known for Webster's Dictionary, its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary pub ...

dictionary in 2018.

Practice

Meditation

The practice of

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

(Ch: chán, Skt:

dhyāna), especially sitting meditation (坐禪, zh, p=zuòchán, ) is a central part of Zen Buddhism.

Meditation in Chinese Buddhism

The practice of

Buddhist meditation

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are ''bhavana, bhāvanā'' ("mental development") and ''Dhyāna in Buddhism, jhāna/dhyāna'' (a state of me ...

originated in India and first entered

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

through the translations of

An Shigao (fl. c. 148–180 CE), and

Kumārajīva

Kumārajīva (Sanskrit: कुमारजीव; , 344–413 CE) was a bhikkhu, Buddhist monk, scholar, missionary and translator from Kucha (present-day Aksu City, Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China). Kumārajīva is seen as one of the great ...

(334–413 CE). Both of these figures translated various ''

Dhyāna sutras''. These were influential meditation texts which were mostly based on the meditation teachings of the

Kashmiri Sarvāstivāda

The ''Sarvāstivāda'' (; ;) was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Ashoka (third century BCE).Westerhoff, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy in the First Millennium CE, 2018, p. 60. It was particularl ...

school (circa 1st–4th centuries CE).

Among the most influential early Chinese meditation texts are the ''

Anban Shouyi Jing'' (安般守意經, Sutra on

''ānāpānasmṛti''), the ''Zuochan Sanmei Jing'' (坐禪三昧經,Sutra of sitting

dhyānasamādhi

Statue of a meditating Rishikesh.html" ;"title="Shiva, Rishikesh">Shiva, Rishikesh

''Samādhi'' (Pali and ), in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, is a state of meditative consciousness. In many Indian religious traditions, the cultivati ...

) and the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' (達摩多羅禪經,

Dharmatrata dhyāna sutra).

These early Chinese meditation works continued to exert influence on Zen practice well into the modern era. For example, the 18th century Rinzai Zen master

Tōrei Enji wrote a commentary on the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' and used the ''Zuochan Sanmei Jing'' as a source in the writing of this commentary.

Tōrei believed that the ''Damoduoluo Chan Jing'' had been authored by

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and is regarded as its first Chinese Lineage (Buddhism), patriarch. ...

.

While ''

dhyāna'' in a strict sense refers to the classic four ''dhyānas'', in

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, first=t, poj=Hàn-thoân Hu̍t-kàu, j=Hon3 Cyun4 Fat6 Gaau3, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism. The Chinese Buddhist canonJiang Wu, "The Chin ...

, ''chán'' may refer to

various kinds of meditation techniques and their preparatory practices, which are necessary to practice ''dhyāna''. The five main types of meditation in the ''Dhyāna sutras'' are

''ānāpānasmṛti'' (mindfulness of breathing);

''paṭikūlamanasikāra'' meditation (mindfulness of the impurities of the body);

''maitrī'' meditation (loving-kindness); the contemplation on the twelve links of ''

pratītyasamutpāda

''Pratītyasamutpāda'' (Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद, Pāli: ''paṭiccasamuppāda''), commonly translated as dependent origination, or dependent arising, is a key doctrine in Buddhism shared by all schools of B ...

''; and

contemplation on the Buddha. According to the modern Chan master

Sheng Yen, these practices are termed the "five methods for stilling or pacifying the mind" and serve to focus and purify the mind, and support the development of the stages of ''dhyana''. Chan Buddhists may also use other classic Buddhist practices like the

four foundations of mindfulness and the Three Gates of Liberation (

emptiness or ''śūnyatā'', signlessness or ''animitta'', and

wishlessness or ''apraṇihita'').

Early Chan texts also teach forms of meditation that are unique to

Mahāyāna

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main ex ...

Buddhism. For example, the ''Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind'', which depicts the teachings of the 7th-century

East Mountain school, teaches a visualization of a sun disk, similar to that taught in the ''

Contemplation Sutra''.

According to

Charles Luk, there was no single fixed method in early Chan (Zen). All the various Buddhist meditation methods were simply

skillful means which could lead a meditator to the buddha-mind within.

Zen's sudden method

Modern scholars like Robert Sharf argue that early Chan, while having unique teachings and myths, also made use of classic Buddhist meditation methods, and this is why it is hard to find many uniquely "Chan" meditation instructions in some of the earliest sources. However, Sharf also notes there was a unique kind of Chan meditation taught in some early sources which also tend to deprecate the traditional Buddhist meditations. This uniquely Zen approach goes by various names like “maintaining mind” (shouxin 守心), “maintaining unity” (shouyi 守一), “discerning the mind” (guanxin 觀心), “viewing the mind” (kanxin 看心), and “pacifying the mind” (anxin 安心). A traditional phrase that describes this practice states that "Chán points directly to the human mind, to enable people to see their true nature and become buddhas."

According to McRae the "first explicit statement of the sudden and direct approach that was to become the hallmark of Ch'an religious practice" is associated with the

East Mountain School. It is a method named "maintaining the one without wavering" (守一不移, shǒu yī bù yí), ''the one'' being the true nature of mind or

Suchness, which is equated with buddha-nature. Sharf writes that in this practice, one turns the attention from the objects of experience to "the nature of conscious awareness itself", the innately pure

buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

, which was compared to a clear mirror or to the sun (which is always shining but may be covered by clouds). This type of meditation is based on classic Mahāyāna ideas which are not uniquely "Chan", but according to McRae it differs from traditional practice in that "no preparatory requirements, no moral prerequisites or preliminary exercises are given," and is "without steps or gradations. One concentrates, understands, and is enlightened, all in one undifferentiated practice."

Zen sources also use the term "

tracing back the radiance" or "turning one's light around" (Ch. fǎn zhào, 返照) to describe seeing the inherent radiant source of the mind itself, the "numinous awareness",

luminosity

Luminosity is an absolute measure of radiated electromagnetic radiation, electromagnetic energy per unit time, and is synonymous with the radiant power emitted by a light-emitting object. In astronomy, luminosity is the total amount of electroma ...

, or buddha-nature. The ''Platform Sutra'' mentions this term and connects it with seeing one's "original face". The ''

Record of Linji'' states that all that is needed to obtain the Dharma is to "turn your own light in upon yourselves and never seek elsewhere". The Japanese Zen master

Dōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

describes it as follows: “You should stop the intellectual practice of pursuing words and learn the ‘stepping back’ of ‘turning the light around and shining back’ (Jp: ekō henshō); mind and body will naturally ‘drop off,’ and the ‘original face’ will appear.” Similarly, the Korean Seon master Yŏndam Yuil states: "to use one's own mind to trace the radiance back to the numinous awareness of one's own mind...It is like seeing the radiance of the sun's rays and following it back until you see the orb of the sun itself."

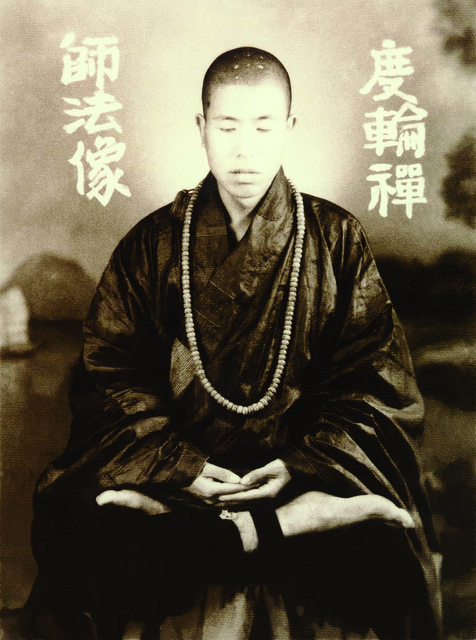

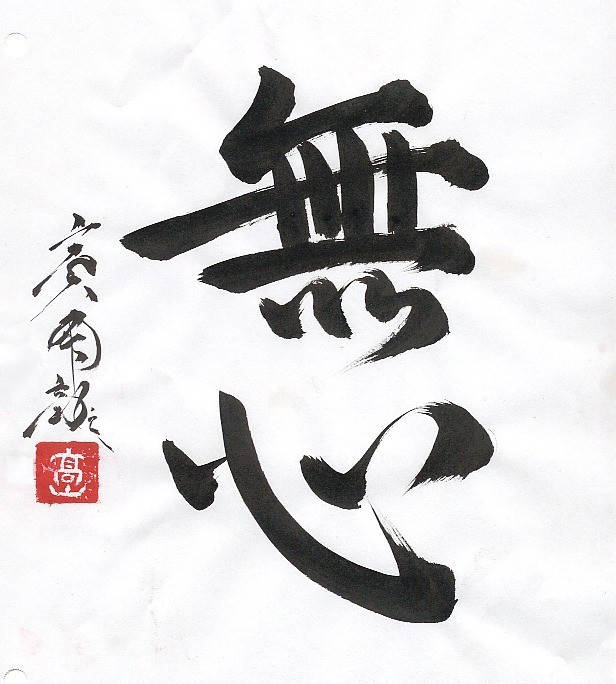

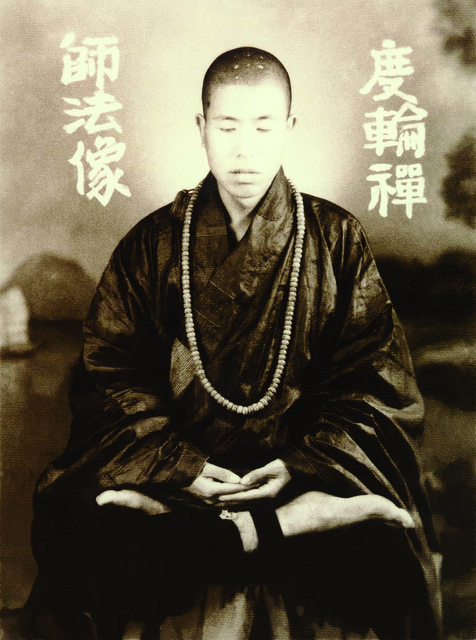

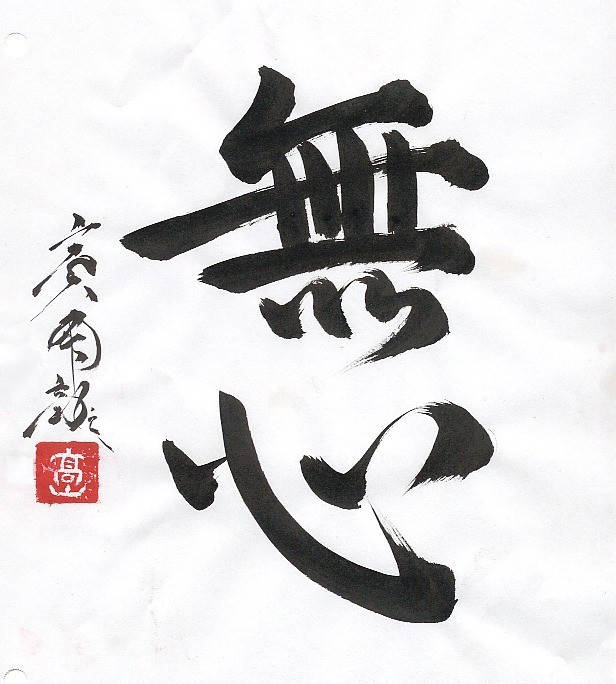

Sharf also notes that the early notion of contemplating a pure Buddha "Mind" was tempered and balanced by other Zen sources with terms like "

no-mind" (wuxin), and "no-mindfulness" (wunian), to avoid any metaphysical

reification of mind, and any clinging to mind or language. This kind of negative

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

style dialectic is found in early Zen sources like the ''Treatise on No Mind'' (''Wuxin lun'' 無心論) of the

Oxhead School and the ''

Platform Sutra

Double page from the Korean woodblock print of "''The Sixth Patriarch's Dharma Jewel Platform Sutra''", Bibliothèque_Nationale_de_France.html" ;"title="Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque Nationale de France">Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque National ...

''. These sources tend to emphasize

emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation, nihilism, and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression (mood), depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

wiktionary:despair, despair, or o ...

, negation, and absence (wusuo 無所) as the main theme of contemplation. These two contemplative themes (the buddha mind and no-mind, positive and the negative rhetoric) continued to shape the development of Zen theory and practice throughout its history.

Later Chinese Chan Buddhists developed their own meditation ("chan") manuals which taught their unique method of direct and sudden contemplation. The earliest of these is the widely imitated and influential ''

Zuòchán Yí'' (c. turn of the 12th century), which recommends a simple contemplative practice which is said to lead to the discovery of

inherent wisdom already present in the mind. This work also shows the influence of the earlier meditation manuals composed by

Tiantai

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai () is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. Drawing from earlier Mahāyāna sources such as Madhyamaka, founded by Nāgārjuna, who is traditionally regarded as the f ...

patriarch

Zhiyi

Zhiyi (; 538–597 CE) also called Dashi Tiantai (天台大師) and Zhizhe (智者, "Wise One"), was a Chinese Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk, Buddhist philosophy, philosopher, meditation teacher, and Exegesis, exegete. He is considered to be the foun ...

.

However, other Zen sources de-emphasize traditional practices like sitting meditation, and instead focus on effortlessness and on ordinary daily activities. One example of this is found in the ''

Record of Linji'' which states: "Followers of the Way, as to buddhadharma, no effort is necessary. You have only to be ordinary, with nothing to do—defecating, urinating, wearing clothes, eating food, and lying down when tired." Similarly, some Zen sources also emphasize non-action or having no concerns (wushi 無事). For example, Chan master

Huangbo states that nothing compares with non-seeking, describing the Zen adept as follows: "the person of the Way is the one who has nothing to do

u-shih who has no mind at all and no doctrine to preach. Having nothing to do, such a person lives at ease."

Likewise, John McRae notes that a major development in early Ch'an was the rejection of traditional meditation techniques in favor of a uniquely Zen direct approach. Early Chan sources like the ''Long Scroll'' (dubbed the ''Bodhidharma Anthology'' by Jeffrey Broughton), the ''

Platform Sutra

Double page from the Korean woodblock print of "''The Sixth Patriarch's Dharma Jewel Platform Sutra''", Bibliothèque_Nationale_de_France.html" ;"title="Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque Nationale de France">Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque National ...

'' and the works of

Shenhui question such things as mindfulness and concentration, and instead state that insight can be attained directly and suddenly. For example, Record I of the ''Long Scroll'' states: "The man of sharp abilities hears of the path without producing a covetous mind. He does not even produce right mindfulness and right reflection," and the iconoclastic

Master Yüan states in Record III of the same text, "If mind is not produced, what need is there for cross-legged sitting dhyana?" Similarly, the ''Platform Sutra'' criticizes the practice of sitting samādhi: "One is enlightened to the Way through the mind. How could it depend on sitting?", while Shenhui's four pronouncements criticize the "freezing", "stopping", "activating", and "concentrating" of the mind.

Zen sources which focus on the sudden teaching can sometimes be quite radical in their rejection of the importance of traditional Buddhist ideas and practices. The ''Record of the Dharma-Jewel Through the Ages'' (''Lidai Fabao Ji'') for example states "better that one should destroy

śīla thics and not destroy true seeing. Śīla

ausesrebirth in Heaven, adding more

armicbonds, while true seeing attains nirvāṇa." Similarly the ''Bloodstream Sermon'' states that it doesn't matter whether one is a butcher or not, if one sees one's true nature, then one will not be affected by

karma

Karma (, from , ; ) is an ancient Indian concept that refers to an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively called ...

. The ''Bloodstream Sermon'' also rejects the worshiping of buddhas and bodhisattvas, stating that "Those who hold onto appearances are devils. They fall from the Path. Why worship illusions born of the mind? Those who worship don't know, and those who know don't worship." Similarly, in the ''Lidai Fabao Ji'',

Wuzhu

Jin Wuzhu (金兀朮, died 1148), also known by his sinicised name Wanyan Zongbi (完顏宗弼), was a prince, military general and civil minister of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty of China. He was the fourth son of Aguda (Emperor Taizu), the ...

states that "No-thought is none other than seeing the Buddha" and rejects the practice of worship and recitation. Most famously, the ''

Record of Linji'' has the master state that "if you meet a buddha, kill the buddha" (as well as patriarchs, arhats, parents, and kinfolk), further claiming that through this "you will gain emancipation, will not be entangled with things."

Common contemporary meditation forms

Mindfulness of breathing

During sitting meditation (坐禅,

Ch. ''zuòchán,''

Jp. ''

zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

'',

Ko. ''jwaseon''), practitioners usually assume a sitting position such as the

lotus position

Lotus position or Padmasana () is a cross-legged sitting meditation posture, meditation pose from History of India, ancient India, in which each foot is placed on the opposite thigh. It is an ancient asana in yoga, predating hatha yoga, and ...

,

half-lotus,

Burmese, or

seiza

'' Seiza '' ( or ; ; ) is the formal, traditional way of sitting in Japan. It involves a specific positioning and posture in a Kneeling, kneeled position so as to convey respect, particularly toward elders. It developed among samurai during t ...

. Their hands often placed in a specific gesture or

mudrā. Often, a square or round cushion placed on a padded mat is used to sit on; in some other cases, a chair may be used.

To regulate the mind, Zen students are often directed towards

counting breaths. Either both exhalations and inhalations are counted, or one of them only. The count can be up to ten, and then this process is repeated until the mind is calmed. Zen teachers like

Omori Sogen

was a Japanese Rinzai Rōshi, a successor in the Tenryū-ji line of Rinzai Zen, and former president of Hanazono University, the Rinzai university in Kyoto, Japan. He became a priest in 1945.

Biography

Ōmori Sōgen was a teacher of Kashi ...

teach a series of long and deep exhalations and inhalations as a way to prepare for regular breath meditation. Attention is often placed on the energy center (''

dantian

Dantian is a concept in traditional Chinese medicine loosely translated as "elixir field", "sea of '' qi''", or simply "energy center." Dantian are the "''qi'' focus flow centers," important focal points for meditative and exercise techniques s ...

'') below the navel. Zen teachers often promote

diaphragmatic breathing

Diaphragmatic breathing, abdominal breathing, belly breathing, or deep breathing, is a breathing technique that is done by contracting the Thoracic diaphragm, diaphragm, a muscle located horizontally between the thoracic cavity and abdominal cav ...

, stating that the breath must come from the lower abdomen (known as

hara or tanden in Japanese), and that this part of the body should expand forward slightly as one breathes. Over time the breathing should become smoother, deeper and slower. When the counting becomes an encumbrance, the practice of simply following the natural rhythm of breathing with concentrated attention is recommended. While some teachers such as

Dainin Katagiri Roshi taught watching the breath, and

Shunryū Suzuki taught counting the breath, others such as

Kōshō Uchiyama

was a Sōtō Zen monk, origami master, and abbot of Antai-ji near Kyoto, Japan.

Uchiyama was author of more than twenty books on Zen Buddhism and origami, of which ''Opening the Hand of Thought: Foundations of Zen Buddhist Practice'' is bes ...

and

Shohaku Okumura taught neither counting nor watching the breath.

Silent illumination and Shikantaza

A common form of sitting meditation is called "Silent illumination" (Ch. ''mòzhào'' 默照, Jp''. mokushō''). This practice was traditionally promoted by the

Caodong school of

Chinese Chan and is associated with

Hongzhi Zhengjue

Hongzhi Zhengjue (, ), also sometimes called Tiantong Zhengjue (; ) (1091–1157), was an influential Chinese Chan Buddhism, Chan Buddhist monk who authored or compiled several influential texts. Hongzhi's conception of ''shikantaza, silent illu ...

(1091–1157) who wrote various works on the practice. This method derives from the Indian Buddhist practice of the union (

Skt. ''yuganaddha'') of ''

śamatha'' and ''

vipaśyanā''.

Hongzhi's practice of silent illumination does not depend on concentration on particular objects, "such as visual images, sounds, breathing, concepts, stories, or deities." Instead, it is a

non-dual

Nondualism includes a number of philosophical and spiritual traditions that emphasize the absence of fundamental duality or separation in existence. This viewpoint questions the boundaries conventionally imposed between self and other, min ...

"objectless" meditation, involving "withdrawal from exclusive focus on a particular sensory or mental object." This practice allows the meditator to be aware of "all phenomena as a unified totality," without any

conceptualizing,

grasping

A grasp is an act of taking, holding or seizing firmly with (or as if with) the hand. An example of a grasp is the handshake, wherein two people grasp one of each other's like hands.

In zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of an ...

,

goal seeking

In computing, goal seeking is the ability to calculate backward to obtain an input that would result in a given output. This can also be called what-if analysis or backsolving. It can either be attempted through trial and improvement or more log ...

, or

subject-object duality. According to

Leighton, this method "rests on the faith, verified in experience, that the field of vast brightness is ours from the outset." This "vast luminous buddha field" is our immanent "inalienable endowment of wisdom" which cannot be cultivated or enhanced. Instead, one just has to recognize this radiant clarity without any interference.

A similar practice is taught in the major schools of

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

, but is especially emphasized by

Sōtō

Sōtō Zen or is the largest of the three traditional sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism (the others being Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku). It is the Japanese line of the Chinese Caodong school, Cáodòng school, which was founded during the ...

, where it is more widely known as ''

shikantaza'' (Ch. ''zhǐguǎn dǎzuò,'' "just sitting"). For instance, the modern Sōtō Zen teacher

Shohaku Okumura says: "We don’t set our mind on any particular object, visualization, mantra, or even our breath itself. When we just sit, our mind is nowhere and everywhere." This method is discussed in the works of the Japanese Sōtō Zen thinker

Dōgen

was a Japanese people, Japanese Zen Buddhism, Buddhist Bhikkhu, monk, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. He is also known as Dōgen Kigen (), Eihei Dōgen (), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (), and Busshō Dent� ...

, especially in his ''

Shōbōgenzō

is the title most commonly used to refer to the collection of works written in Japan by the 13th-century Buddhist monk and founder of the Sōtō Zen school, Eihei Dōgen. Several other works exist with the same title (see above), and it is som ...

'' and his ''

Fukanzazengi''. For Dōgen, shikantaza is characterized by ''hishiryō'' ("non-thinking", "without thinking", "beyond thinking"), which according to Kasulis is "a state of

no-mind in which one is simply aware of things as they are, beyond thinking and not-thinking".

While the Japanese and the Chinese forms of these simple methods are similar, they are considered distinct approaches.

Huatou and Kōan Contemplation

During the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

, ''gōng'àn (''

Jp. ''

kōan

A ( ; ; zh, c=公案, p=gōng'àn ; ; ) is a narrative, story, dialogue, question, or statement from Chan Buddhism, Chinese Chan Buddhist lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen Buddhism, Buddhist practice in different way ...

)'' literature became popular. Literally meaning "public case", they were stories or dialogues describing teachings and interactions between

Zen masters and their students. Kōans are meant to illustrate Zen's non-conceptual insight (''

prajña''). During the Song, a new meditation method was developed by Linji school figures such as

Dahui (1089–1163) called ''kanhua chan'' ("observing the phrase" meditation) which referred to contemplation on a single word or phrase (called the ''

huatou'', "critical phrase") of a ''gōng'àn''. Dahui famously criticised Caodong's "silent illumination." While the two methods of Caodong and Linji are sometimes seen as competing with each other, Schlütter writes that Dahui himself "did not completely condemn quiet-sitting; in fact, he seems to have recommended it, at least to his monastic disciples."

In

Chinese Chan and

Korean Seon

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism (; ) is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan, () an abbreviation of 禪那 (''chánnà''), which is a ...

, the practice of "observing the

''huatou''" (''hwadu'' in Korean) is a widely practiced method. It was taught by Seon masters like

Chinul (1158–1210) and

Seongcheol (1912–1993), and modern Chinese masters like

Sheng Yen and

Xuyun.

In the Japanese

Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

school, ''

kōan

A ( ; ; zh, c=公案, p=gōng'àn ; ; ) is a narrative, story, dialogue, question, or statement from Chan Buddhism, Chinese Chan Buddhist lore, supplemented with commentaries, that is used in Zen Buddhism, Buddhist practice in different way ...

'' introspection developed its own formalized style, with a standardized curriculum of ''kōans'', which must be studied, meditated on and "passed" in sequence. Monks are instructed to "become one" with their koan by repeating the koan's key phrase constantly. They are also advised not to attempt to answer it intellectually, since the goal of the practice is a non-conceptual insight into non-duality. The Zen student's mastery of a given kōan is presented to the teacher in a private interview (referred to in Japanese as ''dokusan'', ''daisan'', or ''sanzen''). The process includes standardized answers, "checking questions" (''sassho'' 拶所) and common sets of "capping phrase" (''

jakugo'') poetry, all which must be memorized by students. While there are standardized answers to a kōan, practitioners are also expected to demonstrate their spiritual understanding through their responses. The teacher may approve or disapprove of the answer based on their behavior, and guide the student in the right direction. According to Hori, the traditional Japanese Rinzai koan curriculum can take 15 years to complete for a full-time monk. The interaction with a teacher is often presented as central in Zen, but also makes Zen practice vulnerable to misunderstanding and exploitation.

Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during ''

zazen

''Zazen'' is a meditative discipline that is typically the primary practice of the Zen Buddhist tradition.

The generalized Japanese term for meditation is 瞑想 (''meisō''); however, ''zazen'' has been used informally to include all forms ...

'' (sitting meditation)'',

kinhin

Walking meditation (Chinese language, Chinese: 經行; Pinyin: ''jīngxíng''; Romanization of Japanese, Romaji: ''kinhin'' or ''kyōgyō''; Korean language, Korean: ''gyeonghyaeng''; Vietnamese language, Vietnamese: ''kinh hành'') is a meditati ...

'' (walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. The goal of the practice is often termed ''

kensho'' (seeing one's true nature), and is to be followed by further practice to attain a natural, effortless, down-to-earth state of being, the "ultimate liberation", "knowing without any kind of defilement". This style of kōan practice is particularly emphasized in modern

Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.

In the Caodong and Sōtō traditions, koans were studied and commented on, for example

Hongzhi published a collection of koans and Dogen discussed koans extensively. However, they were not traditionally used in sitting meditation. Some Zen masters have also critiqued the practice of using koans for meditation. According to Haskel,

Bankei called kōans "old wastepaper" and saw the kōan method as hopelessly contrived. Similarly, the Song era master

Foyan Qingyuan (1067–1120) was critical of the use of koans (public cases) and similar stories, arguing that they did not exist during the time of

Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Bhikkhu, Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century CE. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and is regarded as its first Chinese Lineage (Buddhism), patriarch. ...

. He said, "In other places they like to have people look at model case stories, but here we have the model case story of what is presently coming into being; you should look at it, but no one can make you see all the way through such an immense affair."

Nianfo chan

''

Nianfo

250px, Chinese Nianfo carving

The Nianfo ( zh, t= 念佛, p=niànfó, alternatively in Japanese ; ; or ) is a Buddhist practice central to East Asian Buddhism. The Chinese term ''nianfo'' is a translation of Sanskrit '' '' ("recollection of th ...

'' (Jp. ''nembutsu,'' from Skt. ''

buddhānusmṛti

Buddhānusmṛti (Sanskrit; Pali: Buddhānussati), meaning "Buddha-mindfulness", is a common Buddhist meditation practice in all Buddhist traditions which involves meditating on a Buddha. The term can be translated as "remembrance, commemoration, ...

'' "recollection of the Buddha") refers to the recitation of the Buddha's name, in most cases the Buddha

Amitabha. In Chinese Chan, the

Pure Land

Pure Land is a Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist concept referring to a transcendent realm emanated by a buddhahood, buddha or bodhisattva which has been purified by their activity and Other power, sustaining power. Pure lands are said to be places ...

practice of ''nianfo'' based on the phrase ''Nāmó Āmítuófó'' (Homage to Amitabha) is a widely practiced form of Zen meditation which came to be known as "Nianfo Chan" (念佛禪). Nianfo was practiced and taught by early Chan masters, like

Daoxin (580-651), who taught that one should "bind the mind to one buddha and exclusively invoke his name".

[Sharf, Robert H. ''On Pure Land Buddhism and Ch'an/Pure Land Syncretism in Medieval China.'' T'oung Pao Second Series, Vol. 88, Fasc. 4/5 (2002), pp. 282-331, Brill.] The practice is also taught in

Shenxiu's ''Guanxin lun'' (觀心論).

Likewise, the ''Chuan fabao qi'' (傳法寶紀, Taisho # 2838, ca. 713), one of the earliest Chan histories, shows this practice was widespread in the early Chan generation of

Hung-jen,

Fa-ju and Ta-tung who are said to have "invoked the name of the Buddha so as to purify the mind."

Evidence for the practice of nianfo chan can also be found in

Changlu Zongze's (died c. 1107) ''

Chanyuan qinggui (The Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery),'' perhaps the most influential Ch’an monastic code in East Asia.

Nianfo continued to be taught as a form of Chan meditation by later Chinese figures such as

Yongming Yanshou,

Zhongfen Mingben, and

Tianru Weize. During the

late Ming, the tradition of Nianfo Chan meditation was continued by figures such as

Yunqi Zhuhong and

Hanshan Deqing. Chan figures like

Yongming Yanshou generally advocated a view called "mind-only Pure Land" (wei-hsin ching-t’u), which held that the Buddha and the Pure Land are just mind.

The practice of nianfo, as well as its adaptation into the "''

nembutsu kōan''" ('who is reciting?') is a major practice in the Japanese

Ōbaku school of Zen. The recitation of a Buddha's name was also practiced in the

Soto school at different times throughout its history. During the

Meiji period

The was an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868, to July 30, 1912. The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonizatio ...

for example, both Shaka nembutsu (reciting the name of Shakyamuni Buddha: ''namu Shakamuni Butsu'') and Amida nembutsu were promoted by Soto school priests as easy practices for laypersons.

Nianfo chan is also widely practiced in

Vietnamese Thien.

Bodhisattva virtues and vows

Since Zen is a form of

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism, the others being Thera ...

, it is grounded on the schema of the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person who has attained, or is striving towards, '' bodhi'' ('awakening', 'enlightenment') or Buddhahood. Often, the term specifically refers to a person who forgoes or delays personal nirvana or ''bodhi'' in ...

path, which is based on the practice of the "transcendent virtues" or "perfections" (

Skt. ''

pāramitā

''Pāramitā'' (Sanskrit, Pali: पारमिता) or ''pāramī'' (Pāli: पारमी) is a Buddhist term often translated as "perfection". It is described in Buddhist commentaries as a noble character quality generally associated with ...

'', Ch. ''bōluómì'', Jp. ''baramitsu'') as well as the taking of the

bodhisattva vow

Gandharan relief depicting the ascetic Megha ( Shakyamuni in a past life) prostrating before the past Buddha Dīpaṅkara, c. 2nd century CE ( Swat_District.html" ;"title="Gandhara, Swat District">Swat Valley)

The Bodhisattva vow is a vow (Sans ...

s. The most widely used list of six virtues is:

generosity

Generosity (also called largesse) is the virtue of being liberal in charity (practice), giving, often as gifts. Generosity is regarded as a virtue by various world religions and List of philosophies, philosophies and is often celebrated in cultur ...

,

moral training (incl.

five precepts),

patient endurance,

energy or effort,

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

(''

dhyana

Dhyana may refer to:

Meditative practices in Indian religions

* Dhyana in Buddhism (Pāli: ''jhāna'')

* Dhyana in Hinduism

* Jain Dhyāna, see Jain meditation

Other

*''Dhyana'', a work by British composer John Tavener

Sir John Kenneth ...

''),

wisdom

Wisdom, also known as sapience, is the ability to apply knowledge, experience, and good judgment to navigate life’s complexities. It is often associated with insight, discernment, and ethics in decision-making. Throughout history, wisdom ha ...

. An important source for these teachings is the

''Avatamsaka sutra'', which also outlines the grounds (''

bhumis'') or levels of the bodhisattva path. The

''pāramitās'' are mentioned in early Chan works such as Bodhidharma's ''

Two entrances and four practices'' and are seen as an important part of gradual cultivation (''jianxiu'') by later Chan figures like

Zongmi.

An important element of this practice is the formal and ceremonial taking of

refuge in the three jewels,

bodhisattva vow

Gandharan relief depicting the ascetic Megha ( Shakyamuni in a past life) prostrating before the past Buddha Dīpaṅkara, c. 2nd century CE ( Swat_District.html" ;"title="Gandhara, Swat District">Swat Valley)

The Bodhisattva vow is a vow (Sans ...

s and

precepts. Various sets of precepts are taken in Zen including the

five precepts,

"ten essential precepts", and the

sixteen bodhisattva precepts. This is commonly done in an

initiation ritual

Initiation is a rite of passage marking entrance or acceptance into a group or society. It could also be a formal admission to adulthood in a community or one of its formal components. In an extended sense, it can also signify a transformatio ...

(

Ch. ''shòu jiè'' 受戒,

Jp. ''Jukai'',

Ko. ''sugye,'' "receiving the precepts"'')'', which is also undertaken by

lay followers and marks a layperson as a formal Buddhist.

The

Chinese Buddhist practice of fasting (''zhai''), especially during the

uposatha

An Uposatha () day is a Buddhism, Buddhist day of observance, in existence since the Buddha's time (600 BCE), and still being kept today by Buddhist practitioners. The Buddha taught that the Uposatha day is for "the cleansing of the defiled mind, ...

days (Ch. ''zhairi,'' "days of fasting") can also be an element of Chan training. Chan masters may go on extended absolute fasts, as exemplified by

master Hsuan Hua's 35 day fast, which he undertook during the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis () in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of Nuclear weapons d ...

for the generation of merit.

Monasticism

''Bonzes dans un réfectoire à Canton'' (''Monastics in a Cantonese dining hall''), Félix Régamey, c. before 1888

Zen developed in a

Buddhist monastic context and throughout its history, most Zen masters have been Buddhist monastics (

bhiksus) ordained in the Buddhist monastic code (

Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali and Sanskrit: विनय) refers to numerous monastic rules and ethical precepts for fully ordained monks and nuns of Buddhist Sanghas (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). These sets of ethical rules and guidelines devel ...

) living in

Buddhist monasteries.

[Buswell Jr., Robert E. ''The Zen Monastic Experience: Buddhist Practice in Contemporary Korea,'' pp. 1-9. Princeton University Press, Jul 21, 2020.] East Asian Buddhist monasticism differs in various respects from traditional Buddhist monasticism however, emphasizing

self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person, being, or system needs little or no help from, or interaction with others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a sel ...

. For example, Zen monks do not live by begging, but store and cook their own food in the monastery and may even farm and grow their own food.

Zen Monastics in Japan are particularly exceptional in the Buddhist tradition because the monks and nuns can marry after receiving their ordination. This is because they follow the practice of ordaining under the

bodhisattva vows

file:Sumedha and Dīpankara, 2nd century, Swat Valley, Gandhāra.jpg, Gandharan relief depicting the ascetic Megha (The Buddha, Shakyamuni in a past life) prostrating before the past Buddha Dipankara, Dīpaṅkara, c. 2nd century CE (Gandhara, Swa ...

instead of the traditional monastic Vinaya.

Zen monasteries (伽藍, pinyin: qiélán, Jp: garan, Skt. ''

saṃghārāma'') will often rely on Zen monastic codes like the ''

Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery'' and Dogen's ''Pure Standards for the Zen Community'' (''Eihei Shingi'') which regulate life and behavior in the monastery. Zen monasteries often have a specific building or hall for meditation, the

zendō (禅堂, Chinese: chántáng), as well as a "buddha hall" (佛殿, Ch:, Jp: ''

butsuden'') used for ritual purposes which houses the "

main object of veneration" (本尊, Ch: běnzūn, Jp: honzon), usually a Buddha image. Life in a Zen monastery is often guided by a daily schedule which includes periods of work, group meditation, rituals, and

formal meals.

Intensive group practice

Intensive group meditation may be practiced by serious Zen practitioners. In the Japanese language, this practice is called ''

sesshin

A ''sesshin'' (接心, or also 摂心/攝心 literally "touching the heart-mind") is a period of intensive meditation (zazen) retreat in a Japanese Zen monastery, or in a Zen monastery or Zen center that belongs to one of the Japanese Zen trad ...

''. While the daily routine may require monks to meditate for several hours each day, during the intensive period they devote themselves almost exclusively to zen practice. The numerous 30–50 minute long sitting meditation (''zazen'') periods are interwoven with rest breaks, ritualized formal meals (Jp. ''

oryoki''), and short periods of work (Jp. ''

samu'') that are to be performed with the same state of mindfulness. In modern Buddhist practice in Japan,

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

, and the West, lay students often attend these intensive practice sessions or retreats. These are held at many Zen centers or temples.

Chanting and rituals

Most Zen monasteries, temples and centers perform various

ritual

A ritual is a repeated, structured sequence of actions or behaviors that alters the internal or external state of an individual, group, or environment, regardless of conscious understanding, emotional context, or symbolic meaning. Traditionally ...

s, services and

ceremonies

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan origin, via the Latin .

Religious and civil (secular) ceremoni ...

(such as initiation ceremonies and

funerals), which are always accompanied by the chanting of verses, poems or

sutras. There are also ceremonies that are specifically for the purpose of sutra recitation (Ch. ''niansong'', Jp. ''nenju'') itself. Zen schools may have an official sutra book that collects these writings (in Japanese, these are called ''kyohon''). Practitioners may chant major

Mahayana sutras

The Mahayana sutras are Buddhist texts that are accepted as wikt:canon, canonical and authentic Buddhist texts, ''buddhavacana'' in Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist sanghas. These include three types of sutras: Those spoken by the Buddha; those spoke ...

such as the ''

Heart Sutra

The ''Heart Sūtra'', ) is a popular sutra in Mahayana, Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Sanskrit, the title ' translates as "The Heart of the Prajnaparamita, Perfection of Wisdom".

The Sutra famously states, "Form is emptiness (''śūnyatā''), em ...

'' and chapter 25 of the ''

Lotus Sutra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' (Sanskrit: ''Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram'', ''Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma'', zh, p=Fǎhuá jīng, l=Dharma Flower Sutra) is one of the most influential and venerated Buddhist Mahāyāna sūtras. ...

'' (often called the "

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (meaning "the lord who looks down", International Phonetic Alphabet, IPA: ), also known as Lokeśvara ("Lord of the World") and Chenrezig (in Tibetan), is a Bodhisattva#Bhūmis (stages), tenth-level bodhisattva associ ...

Sutra").

Dhāraṇīs and Zen poems may also be part of a Zen temple

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

, including texts like the ''

Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi'', the ''

Sandokai'', the ''

Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī'', and the ''

Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra

The ushnisha (, Pali: ''uṇhīsa'') is a protuberance on top of the head of a Buddha. In Buddhist literature, it is sometimes said to represent the "crown" of a Buddha, a symbol of Enlightenment and status the King of the Dharma.

Descrip ...

''.

The ''

butsudan'' is the altar in a monastery, temple or a lay person's home, where offerings are made to the images of the Buddha,

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person who has attained, or is striving towards, '' bodhi'' ('awakening', 'enlightenment') or Buddhahood. Often, the term specifically refers to a person who forgoes or delays personal nirvana or ''bodhi'' in ...

s and deceased family members and ancestors. Rituals usually center on major Buddhas or bodhisattvas like

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (meaning "the lord who looks down", International Phonetic Alphabet, IPA: ), also known as Lokeśvara ("Lord of the World") and Chenrezig (in Tibetan), is a Bodhisattva#Bhūmis (stages), tenth-level bodhisattva associ ...

(see

Guanyin

Guanyin () is a common Chinese name of the bodhisattva associated with Karuṇā, compassion known as Avalokiteśvara (). Guanyin is short for Guanshiyin, which means " he One WhoPerceives the Sounds of the World". Originally regarded as m ...

),

Kṣitigarbha and

Manjushri. An important element in Zen ritual practice is the performance of ritual

prostrations (Jp. ''raihai'') or bows, usually done in front of a butsudan.

A widely practiced ritual in

Chinese Chan is the tantric

Yujia Yankou rite that is practiced with the aim of facilitating the spiritual nourishment of all

sentient beings

Sentience is the ability to experience feelings and sensations. It may not necessarily imply higher cognitive functions such as awareness, reasoning, or complex thought processes. Some writers define sentience exclusively as the capacity for ''v ...

.

The Chinese holiday of the

Ghost Festival

The Ghost Festival or Hungry Ghost Festival, also known as the Zhongyuan Festival in Taoism and the Yulanpen Festival in Buddhism, is a traditional festival held in certain East Asia, East and Southeast Asian countries. According to the Lunar c ...

might also be celebrated with similar rituals for the dead.

are also an important ritual and are a common point of contact between Zen monastics and the laity. Statistics published by the Sōtō school state that 80 percent of Sōtō laymen visit their temple only for reasons having to do with funerals and death. Seventeen percent visit for spiritual reasons and 3 percent visit a Zen priest at a time of personal trouble or crisis.

Another important type of ritual practiced in Zen are various

repentance

Repentance is reviewing one's actions and feeling contrition or regret for past or present wrongdoings, which is accompanied by commitment to and actual actions that show and prove a change for the better.

In modern times, it is generally seen ...

or confession rituals (懺悔, Ch. ''Chànhǔi,'' Jp. ''Zange'') that were widely practiced in all forms of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. One popular type of such a ritual in Chan Buddhism is the

Liang Emperor Repentance Ritual, composed by Chan master Baozhi.

Dogen also wrote a treatise on repentance, the ''Shushogi''.

Other rituals could include rites dealing with

local deities (''

kami

are the Deity, deities, Divinity, divinities, Spirit (supernatural entity), spirits, mythological, spiritual, or natural phenomena that are venerated in the traditional Shinto religion of Japan. ''Kami'' can be elements of the landscape, forc ...

'' in Japan), and ceremonies on Buddhist holidays such as Buddha's Birthday. Another popular form of ritual in Japanese Zen is ''Mizuko kuyō'' (Water child) ceremonies, which are performed for those who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion. These ceremonies are also performed in American Zen Buddhism.

Esoteric practices

Depending on the tradition, Vajrayana, esoteric methods such as Mantras, mantra and Dharani, dhāraṇī may also be used for different purposes including meditation practice, protection from evil, invoking great compassion, invoking the power of certain bodhisattvas, and are chanted during ceremonies and rituals. In the Kwan Um School of Zen, Kwan Um school of Zen for example, a mantra of

Guanyin

Guanyin () is a common Chinese name of the bodhisattva associated with Karuṇā, compassion known as Avalokiteśvara (). Guanyin is short for Guanshiyin, which means " he One WhoPerceives the Sounds of the World". Originally regarded as m ...

("''Kwanseum Bosal''") may be used during sitting meditation. The Heart Sutra#Mantra, Heart Sutra Mantra is also another mantra that is used in Zen during various rituals. Another example is the Mantra of Light, which is common in both the Chinese

Chan tradition (where it is mostly used during the Shuilu Fahui ceremony) as well as the Japanese Sōtō, Soto Zen and (where its usage derives from the Shingon Buddhism, Shingon sect).

In

Chinese Chan, the usage of esoteric mantras in Zen goes back to the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

. There is evidence that Chan Buddhism, Chan Buddhists adopted practices from Chinese Esoteric Buddhism in Dunhuang manuscripts, findings from Dunhuang. According to Henrik Sørensen, several successors of Yuquan Shenxiu, Shenxiu (such as Jingxian and Yixing) were also students of the Chinese Esoteric Buddhism, Zhenyan (Mantra) school. Influential esoteric Dharani, dhāraṇī, such as the ''

Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra

The ushnisha (, Pali: ''uṇhīsa'') is a protuberance on top of the head of a Buddha. In Buddhist literature, it is sometimes said to represent the "crown" of a Buddha, a symbol of Enlightenment and status the King of the Dharma.

Descrip ...

'' and the ''

Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī'', also begin to be cited in the literature of the Baotang school during the Tang dynasty. The eighth century Chan monks of Shaolin Monastery, Shaolin temple also performed esoteric practices such as mantras and dharanis. Many mantras have been preserved since the Tang period and continue to be practiced in modern monasteries. One common example is the Shurangama Mantra, ''Śūraṅgama Mantra'', which is commonly chanted by monastics as part of the morning liturgy (朝誦 ''Cháosòng'') and evening liturgy (暮誦 ''Mùsòng'') in temples. Various rituals that continue to be practiced by Chan monastics, such as the tantric

Yujia Yankou rite and the extensive Shuilu Fahui ceremony, also involve esoteric aspects, including Mandala, maṇḍala offerings, deity yoga and the invocation of esoteric deities such as the Five Wisdom Buddhas and the Wisdom King#The Ten Wisdom Kings, Ten Wisdom Kings.

In Japan, Zen schools also adopted esoteric rites and continue to perform them. These include the ambrosia gate (甘露門 ''kanro mon'') Ghost Festival, ghost festival ritual which includes esoteric elements, the secret Dharma transmission (嗣法 ''shihō'') rituals and in some cases the Homa (ritual)#Buddhism, homa ritual.

During the Joseon Dynasty, the Korean Zen (Seon) was highly inclusive and ecumenical. This extended to Esoteric Buddhist lore and rituals (that appear in Seon literature from the 15th century onwards). According to Sørensen, the writings of several Seon masters (such as Hyujeong) reveal they were esoteric adepts. In

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

, the use of esoteric practices within Zen is sometimes termed "mixed Zen" (兼修禪 ''kenshū zen''), and the influential Soto monk Keizan, Keizan Jōkin (1264–1325) was major promoter of esoteric methods. Keizan was heavily influenced by Shingon Buddhism, Shingon and Shugendō, Shugendo, and is known for introducing numerous esoteric ritual forms into the

Soto school. Another influential Soto figure, Menzan Zuihō (1683-1769), was also a practitioner of Shingon, having received esoteric initiation under a Shingon figure named Kisan Biku (義燦比丘). Similarly, numerous Rinzai figures were also esoteric practitioners, such as the Rinzai founder Eisai, Myōan Eisai (1141–1215) and Enni, Enni Ben'en (1202–1280). Under Enni Ben'en's abbotship, Fumon-in (the future Tōfuku-ji) held Shingon and Tendai rituals. He also lectured on the esoteric ''Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra, Mahavairocana sutra''.

The arts

Certain The arts, arts such as Buddhist art in Japan, painting, calligraphy, Chinese poetry, poetry, Japanese garden, gardening, Ikebana, flower arrangement, tea ceremony and others have also been used as part of zen training and practice. Classical Chinese arts like Ink wash painting, brush painting and Chinese calligraphy, calligraphy were used by Chan monk painters such as Guanxiu and Muqi Fachang to communicate their spiritual understanding in unique ways to their students. Some Zen writers even argued that "devotion to an art" (Japanese: suki) could be a spiritual practice that leads to enlightenment, as the Japanese monk poet Kamo no Chōmei, Chōmei writes in his ''Hosshinshū''.

Zen paintings are sometimes termed ''zenga'' in Japanese. Hakuin Ekaku, Hakuin is one Japanese Zen master who was known to create a large corpus of unique Ink wash painting, ''sumi-e'' (ink and wash paintings) and Japanese calligraphy to communicate zen in a visual way. His work and that of his disciples were widely influential in

Japanese Zen

:''See also Zen for an overview of Zen, Chan Buddhism for the Chinese origins, and Sōtō, Rinzai school, Rinzai and Ōbaku for the three main schools of Zen in Japan''

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen, Zen Buddhism, an orig ...

. Another example of Zen arts can be seen in the short lived Fuke-shū, Fuke sect of Japanese Zen, which practiced a unique form of "blowing zen" (''suizen'' 吹禅) by playing the ''shakuhachi'' bamboo flute.

Physical cultivation

Traditional martial arts, like Chinese martial arts, Kyūdō, Japanese archery, other forms of Japanese ''budō'' have also been seen as forms of zen praxis by some Zen schools. In China, this trend goes back to the influential Shaolin Monastery in Henan, which developed the first institutionalized form of ''gōngfu''. By the

late Ming, Shaolin ''gōngfu'' was very popular and widespread, as evidenced by mentions in various forms of Ming literature (featuring staff wielding fighting monks like Sun Wukong) and historical sources, which also speak of Shaolin's impressive monastic army that rendered military service to the state in return for patronage.

These Shaolin Kung Fu, Shaolin practices, which began to develop around the 12th century, were also traditionally seen as a form of Chan Buddhist inner cultivation (today called ''wuchan'', "martial chan"). The Shaolin arts also made use of Taoist physical exercises (''daoyin'') breathing and ''qi'' cultivation (qigong) practices. They were seen as therapeutic practices, which improved "internal strength" (''neili''), health and longevity (lit. "nourishing life" ''yangsheng''), as well as means to spiritual liberation. The influence of these Taoist practices can be seen in the work of Wang Zuyuan (ca. 1820–after 1882), whose ''Illustrated Exposition of Internal Techniques'' (''Neigong tushuo'') shows how Shaolin monks drew on Taoist methods like those of the ''Yijin Jing'' and Baduanjin qigong, Eight pieces of brocade. According to the modern Chan master Sheng Yen,

Chinese Buddhism

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, first=t, poj=Hàn-thoân Hu̍t-kàu, j=Hon3 Cyun4 Fat6 Gaau3, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism. The Chinese Buddhist canonJiang Wu, "The Chin ...

has adopted Neijia, internal cultivation exercises from the Shaolin tradition as ways to "harmonize the body and develop concentration in the midst of activity." This is because, "techniques for harmonizing the Qi, vital energy are powerful assistants to the cultivation of ''samadhi'' and Prajnaparamita, spiritual insight."

Korean Seon

Seon or Sŏn Buddhism (; ) is the Korean name for Chan Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism commonly known in English as Zen Buddhism. Seon is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Chan, () an abbreviation of 禪那 (''chánnà''), which is a ...

also has developed a similar form of active physical training, termed ''Sunmudo''.

In

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, the classic combat arts (''budō'') and zen practice have been in contact since the embrace of

Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

Zen by the Hōjō clan in the 13th century, who applied zen discipline to their martial practice. One influential figure in this relationship was the Rinzai priest Takuan Sōhō who was well known for his writings on zen and ''budō'' addressed to the samurai class (especially his ''The Unfettered Mind'') .

The

Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

school also adopted certain Chinese practices which work with qi (which are also common in Taoism). They were introduced by Hakuin Ekaku, Hakuin (1686–1769) who learned various techniques from a hermit named Hakuyu who helped Hakuin cure his "Zen sickness" (a condition of physical and mental exhaustion). These energetic practices, known as ''naikan'', are based on focusing the mind and one's vital energy (''ki'') on the ''dantian, tanden'' (a spot slightly below the navel).

Doctrine

Zen is grounded in the rich doctrinal background of East Asian Buddhism, East Asian Mahayana Buddhism. Zen doctrinal teaching is thoroughly influenced by the Mahayana, Mahayana Buddhist teachings on the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is a person who has attained, or is striving towards, '' bodhi'' ('awakening', 'enlightenment') or Buddhahood. Often, the term specifically refers to a person who forgoes or delays personal nirvana or ''bodhi'' in ...

path, Chinese

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

(''East Asian Mādhyamaka, Sānlùn''), Yogachara, Yogacara (''East Asian Yogācāra, Wéishí''), the ''Prajnaparamita, Prajñaparamita'' literature, and

Buddha nature

In Buddhist philosophy and Buddhist paths to liberation, soteriology, Buddha-nature (Chinese language, Chinese: , Japanese language, Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all Sentient beings (Buddhism), sentient beings to bec ...

texts like the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra'' and the ''Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, Nirvana sutra''.

Some Zen traditions (especially Linji school, Linji /

Rinzai

The Rinzai school (, zh, t=臨濟宗, s=临济宗, p=Línjì zōng), named after Linji Yixuan (Romaji: Rinzai Gigen, died 866 CE) is one of three sects of Zen in Japanese Buddhism, along with Sōtō and Ōbaku. The Chinese Linji school of ...

focused traditions) stress a narrative which sees Zen as a "special transmission outside scriptures", which does not "stand upon words". Nevertheless, Mahayana Buddhist doctrine and East Asian Buddhist teachings remain an essential part of Zen Buddhism. Various Zen masters throughout the history of Zen, like Guifeng Zongmi, Jinul, and

Yongming Yanshou, have instead promoted the "correspondence of the teachings and Zen", which argues for the unity of Zen and the Buddhist teachings.

In Zen, doctrinal teaching is often compared to "the finger pointing at the moon". While Zen doctrines point to the moon (Enlightenment in Buddhism, awakening, the Dharmadhatu, Dharma-realm, the originally enlightened mind), one should not mistake fixating on the finger (the teachings) to be Zen, instead one must look at the moon (reality). As such, doctrinal teachings are just another

skillful means (upaya) which can help one attain awakening. They are not the goal of Zen, nor are they held as fixed dogmas to be attached to (since ultimate reality transcends all concepts), but are nevertheless seen as useful (as long as one does not Reification (fallacy), reify them or cling to them).

Buddha-nature and innate enlightenment

The complex Mahayana Buddhist notion of

Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

(Sanskrit: buddhadhātu, Chinese: 佛性 fóxìng, Japanese: busshō) was a key idea in the doctrinal development of Zen and remains central to Zen Buddhism. In China, this doctrine developed to encompass the related teaching of original enlightenment (本覺 Ch: ''běnjué''; Jp: ''hongaku''), which held that the awakened mind of a Buddha is already present in each sentient being and that enlightenment is "inherent from the outset" and "accessible in the present."

Drawing on sources like the ''Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, Lankavatara sutra'', the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras, buddha-nature sutras, the ''Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana, Awakening of Faith,'' and the ''Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment,'' Chan masters championed the view that the innately awakened buddha-mind was immanently present within all beings. Following the view of the ''Awakening of Faith'', this awakened buddha-nature is seen in Zen as the empty source of all things, the ultimate principle (li) out of which all phenomena (Ch: shi, i.e. all dharmas) arise.

[Muller, Charles]

"Innate Enlightenment and No-thought: A Response to the Critical Buddhist Position on Zen".

Toyo Gakuen University, A paper delivered to the International Conference on Sôn at Paekyang-sa, Kwangju, Korea, August 22, 1998.

Thus, the Zen path is one of recognizing the inherently enlightened source that is already here. Indeed, the Zen insight and the Zen path are based on that very innate awakening. By the time of the codification of the ''

Platform Sutra

Double page from the Korean woodblock print of "''The Sixth Patriarch's Dharma Jewel Platform Sutra''", Bibliothèque_Nationale_de_France.html" ;"title="Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque Nationale de France">Goryeo, c. 1310. Bibliothèque National ...

'' (c. 8th to 13th century), the Zen scripture par excellence, original enlightenment had become a central teaching of the Zen tradition.

Historically influential Chan schools like East Mountain Teaching, East Mountain and Hongzhou school, Hongzhou drew on the ''Awakening of Faith'' in its teachings on the buddha-mind, "the true mind as

Suchness", which Hongzhou compared to a clear mirror. Similarly, the Tang master Guifeng Zongmi draws on the ''Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment'' when he writes that "all sentient beings without exception have the intrinsically enlightened true mind", which is a "clear and bright ever-present awareness" that gets covered over by deluded thoughts. The importance of the concept of the innately awakened mind for Zen is such that it even became an alternative name for Zen, the "Buddha-mind school".

Emptiness and negative dialectic

The influence of Madhyamaka and ''Prajñaparamita'' on Zen can be discerned in the Zen stress on

emptiness

Emptiness as a human condition is a sense of generalized boredom, social alienation, nihilism, and apathy. Feelings of emptiness often accompany dysthymia, depression (mood), depression, loneliness, anhedonia,

wiktionary:despair, despair, or o ...

(空 kōng), non-conceptual wisdom (Skt: nirvikalpa-Jñāna, jñana), the teaching of

no-mind, and the

apophatic and sometimes paradoxical language of Zen literature.

Zen masters and texts took great pains to avoid the

reification of doctrinal concepts and terms, including important terms like buddha-nature and enlightenment. This is because Zen affirms the Mahayana view of emptiness, which states that all phenomena lack a fixed and independent essence (Madhyamaka#Svabhāva, what madhyamaka denies, svabhava). To avoid any reification which grasps at essences, Zen sources often make use of a negative dialectic influenced by

Madhyamaka

Madhyamaka ("middle way" or "centrism"; ; ; Tibetic languages, Tibetan: དབུ་མ་པ་ ; ''dbu ma pa''), otherwise known as Śūnyavāda ("the Śūnyatā, emptiness doctrine") and Niḥsvabhāvavāda ("the no Svabhava, ''svabhāva'' d ...

philosophy. As Kasulis writes, since all things are empty, "the Zen student must learn not to think of linguistic distinctions as always referring to ontically distinct realities." Indeed, all doctrines, distinctions and words are relative and deceptive in some way, and thus they must be transcended. This apophatic element of Zen teaching is sometimes described as Mu (negative), Mu (無, Ch: ''wú'', "no"), which appears in the famous Zhaozhou's Dog koan: A monk asked, "Does a dog have a Buddha-nature or not?"; The master said, "Not [''wú'']!".

Zen teachings also often include a seemingly paradoxical use of both negation and affirmation. For example, the teachings of the influential

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, c=唐朝), or the Tang Empire, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an Wu Zhou, interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed ...

master Mazu Daoyi, founder of the Hongzhou school, could include affirmative phrases like "Mind is Buddha" as well as negative ones like "it is neither mind nor Buddha". Since no concepts or differentiations can capture the true nature of things, Zen affirms the importance of the non-conceptual and non-differentiating perfection of wisdom (Prajnaparamita, prajñaparamita), which transcends all relative and conventional language (even the language of negation itself). According to Kasulis, this is the basis of much apophatic rhetoric found in Zen which often seems paradoxical or contradictory.

The importance of negation is also seen in the key Zen teaching of