The Renaissance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the

Humanities in the Western Tradition

Ch. 13 Renaissance humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini sought out in Europe's monastic libraries the Latin literary, historical, and oratorical texts of

Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance

' (Retrieved May 10, 2007) In addition, many Greek Christian works, including the Greek New Testament, were brought back from Byzantium to Western Europe and engaged Western scholars for the first time since late antiquity. This new engagement with Greek Christian works, and particularly the return to the original Greek of the New Testament promoted by humanists

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in

In stark contrast to the

In stark contrast to the

Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob, 2008, pp. 261–262. The movement to reintegrate the regular study of Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts back into the Western European curriculum is usually dated to the 1396 invitation from Coluccio Salutati to the Byzantine diplomat and scholar Manuel Chrysoloras (c. 1355–1415) to teach Greek in Florence. This legacy was continued by a number of expatriate Greek scholars, from Basilios Bessarion to

The unique political structures of

The unique political structures of

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

'', translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878. Likewise, the position of Italian cities such as Venice as great trading centres made them intellectual crossroads.

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

'', translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878. Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of

Applied innovation extended to commerce. At the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli published the first work on

Applied innovation extended to commerce. At the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli published the first work on

During the Renaissance, extending from 1450 to 1650, every continent was visited and mostly mapped by Europeans, except the south polar continent now known as

During the Renaissance, extending from 1450 to 1650, every continent was visited and mostly mapped by Europeans, except the south polar continent now known as

The new ideals of humanism, although more secular in some aspects, developed against a Christian backdrop, especially in the Northern Renaissance. Much, if not most, of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church. However, the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary

The new ideals of humanism, although more secular in some aspects, developed against a Christian backdrop, especially in the Northern Renaissance. Much, if not most, of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church. However, the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary  The Renaissance began in times of religious turmoil. The late

The Renaissance began in times of religious turmoil. The late

By the 15th century, writers, artists, and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place and were using phrases such as ''modi antichi'' (in the antique manner) or ''alle romana et alla antica'' (in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. In the 1330s Petrarch referred to pre-Christian times as ''antiqua'' (ancient) and to the Christian period as ''nova'' (new). From Petrarch's Italian perspective, this new period (which included his own time) was an age of national eclipse.

Leonardo Bruni was the first to use tripartite periodization in his ''History of the Florentine People'' (1442).Leonardo Bruni, James Hankins, ''History of the Florentine people'', Volume 1, Books 1–4 (2001), p. xvii. Bruni's first two periods were based on those of Petrarch, but he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in ''Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire'' (1439–1453).

Humanist historians argued that contemporary scholarship restored direct links to the classical period, thus bypassing the Medieval period, which they then named for the first time the "Middle Ages". The term first appears in Latin in 1469 as ''media tempestas'' (middle times).Albrow, Martin, ''The Global Age: state and society beyond modernity'' (1997), Stanford University Press

By the 15th century, writers, artists, and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place and were using phrases such as ''modi antichi'' (in the antique manner) or ''alle romana et alla antica'' (in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. In the 1330s Petrarch referred to pre-Christian times as ''antiqua'' (ancient) and to the Christian period as ''nova'' (new). From Petrarch's Italian perspective, this new period (which included his own time) was an age of national eclipse.

Leonardo Bruni was the first to use tripartite periodization in his ''History of the Florentine People'' (1442).Leonardo Bruni, James Hankins, ''History of the Florentine people'', Volume 1, Books 1–4 (2001), p. xvii. Bruni's first two periods were based on those of Petrarch, but he added a third period because he believed that Italy was no longer in a state of decline. Flavio Biondo used a similar framework in ''Decades of History from the Deterioration of the Roman Empire'' (1439–1453).

Humanist historians argued that contemporary scholarship restored direct links to the classical period, thus bypassing the Medieval period, which they then named for the first time the "Middle Ages". The term first appears in Latin in 1469 as ''media tempestas'' (middle times).Albrow, Martin, ''The Global Age: state and society beyond modernity'' (1997), Stanford University Press

p. 205

. The term ''rinascita'' (rebirth) first appeared, however, in its broad sense in

The word "Renaissance" is borrowed from the French language, where it means "re-birth". It was first used in the eighteenth century and was later popularized by French

The word "Renaissance" is borrowed from the French language, where it means "re-birth". It was first used in the eighteenth century and was later popularized by French

In the second half of the 15th century, the Renaissance spirit spread to

In the second half of the 15th century, the Renaissance spirit spread to

The Renaissance in Hungary

(Retrieved May 10, 2007) The most important humanists living in Matthias' court were

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

to modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the "Age of Reas ...

and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas and achievements of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

. It occurred after the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages

The Crisis of the Late Middle Ages was a series of events in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that ended centuries of European stability during the Late Middle Ages. Three major crises led to radical changes in all areas of society: demogr ...

and was associated with great social change. In addition to the standard periodization, proponents of a "long Renaissance" may put its beginning in the 14th century and its end in the 17th century.

The traditional view focuses more on the early modern aspects of the Renaissance and argues that it was a break from the past, but many historians today focus more on its medieval aspects and argue that it was an extension of the Middle Ages. However, the beginnings of the period – the early Renaissance of the 15th century and the Italian Proto-Renaissance from around 1250 or 1300 – overlap considerably with the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

, conventionally dated to , and the Middle Ages themselves were a long period filled with gradual changes, like the modern age; and as a transitional period between both, the Renaissance has close similarities to both, especially the late and early sub-periods of either.

The intellectual basis of the Renaissance was its version of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, derived from the concept of Roman '' humanitas'' and the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy, such as that of Protagoras

Protagoras (; el, Πρωταγόρας; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing t ...

, who said that "man is the measure of all things". This new thinking became manifest in art, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

, science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

. Early examples were the development of perspective in oil painting

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments with a medium of drying oil as the binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on wood panel or canvas for several centuries, spreading from Europe to the rest ...

and the revived knowledge of how to make concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most ...

. Although the invention of metal movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation ...

sped the dissemination of ideas from the later 15th century, the changes of the Renaissance were not uniform across Europe: the first traces appear in Italy as early as the late 13th century, in particular with the writings of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

and the paintings of Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/ Proto-Renaissance period. ...

.

As a cultural movement, the Renaissance encompassed innovative flowering of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

and vernacular literature

Vernacular literature is literature written in the vernacular—the speech of the "common people".

In the European tradition, this effectively means literature not written in Latin nor Koine Greek. In this context, vernacular literature appeare ...

s, beginning with the 14th-century resurgence of learning based on classical sources, which contemporaries credited to Petrarch; the development of linear perspective and other techniques of rendering a more natural reality in painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and ai ...

; and gradual but widespread educational reform. In politics, the Renaissance contributed to the development of the customs and conventions of diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

, and in science to an increased reliance on observation and inductive reasoning. Although the Renaissance saw revolutions in many intellectual and social scientific pursuits, as well as the introduction of modern banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

and the field of accounting, it is perhaps best known for its artistic developments and the contributions of such polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

s as Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

and Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

, who inspired the term "Renaissance man".

The Renaissance began in the Republic of Florence, one of the many states of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Various theories have been proposed to account for its origins and characteristics, focusing on a variety of factors including the social and civic peculiarities of Florence at the time: its political structure, the patronage of its dominant family, the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Muge ...

,Strathern, Paul ''The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance'' (2003) and the migration of Greek scholars and their texts to Italy following the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

to the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

.''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Renaissance", 2008, O.Ed.Norwich, John Julius, ''A Short History of Byzantium'', 1997, Knopf, Other major centers were northern Italian city-states such as Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard language, Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the List of cities in Italy, second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 ...

, Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

during the Renaissance Papacy and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

. From Italy, the Renaissance spread throughout Europe in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, France, Britain, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Poland, Hungary (with Beatrice of Naples) and elsewhere.

The Renaissance has a long and complex historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

, and, in line with general scepticism of discrete periodizations, there has been much debate among historians reacting to the 19th-century glorification of the "Renaissance" and individual cultural heroes as "Renaissance men", questioning the usefulness of ''Renaissance'' as a term and as a historical delineation. Some observers have called into question whether the Renaissance was a cultural "advance" from the Middle Ages, instead seeing it as a period of pessimism and nostalgia for classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

, Huizanga, Johan, ''The Waning of the Middle Ages

''The Autumn of the Middle Ages'', ''The Waning of the Middle Ages'', or ''Autumntide of the Middle Ages'' (published in 1919 as ''Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen'' and translated into English in 1924, German in 1924, and French in 1932), is the best ...

'' (1919, trans. 1924) while social and economic historians, especially of the '' longue durée'', have instead focused on the continuity between the two eras, which are linked, as Panofsky observed, "by a thousand ties".

The term ''rinascita'' ('rebirth') first appeared in Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari (, also , ; 30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian Renaissance Master, who worked as a painter, architect, engineer, writer, and historian, who is best known for his work '' The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculp ...

's '' Lives of the Artists'' (c. 1550), anglicized as the ''Renaissance'' in the 1830s. The word has also been extended to other historical and cultural movements, such as the Carolingian Renaissance (8th and 9th centuries), Ottonian Renaissance

The Ottonian Renaissance was a renaissance of Byzantine and Late Antique art in Central and Southern Europe that accompanied the reigns of the first three Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (or Saxon) dynasty: Otto I (936–973), Otto II (97 ...

(10th and 11th century), and the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Overview

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period. Beginning in Italy, and spreading to the rest of Europe by the 16th century, its influence was felt in art,architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, philosophy, literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

, music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

, science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

, technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scie ...

, politics, religion, and other aspects of intellectual inquiry. Renaissance scholars employed the humanist method in study, and searched for realism and human emotion in art.Perry, MHumanities in the Western Tradition

Ch. 13 Renaissance humanists such as Poggio Bracciolini sought out in Europe's monastic libraries the Latin literary, historical, and oratorical texts of

antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, while the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

(1453) generated a wave of émigré Greek scholars bringing precious manuscripts in ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

, many of which had fallen into obscurity in the West. It is in their new focus on literary and historical texts that Renaissance scholars differed so markedly from the medieval scholars of the Renaissance of the 12th century, who had focused on studying Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

works of natural sciences, philosophy, and mathematics, rather than on such cultural texts.

In the revival of neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonism, Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and Hellenistic religion, religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of ...

Renaissance humanists did not reject Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

; quite the contrary, many of the greatest works of the Renaissance were devoted to it, and the Church patronized many works of Renaissance art. However, a subtle shift took place in the way that intellectuals approached religion that was reflected in many other areas of cultural life.Open University, Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance

' (Retrieved May 10, 2007) In addition, many Greek Christian works, including the Greek New Testament, were brought back from Byzantium to Western Europe and engaged Western scholars for the first time since late antiquity. This new engagement with Greek Christian works, and particularly the return to the original Greek of the New Testament promoted by humanists

Lorenzo Valla

Lorenzo Valla (; also Latinized as Laurentius; 14071 August 1457) was an Italian Renaissance humanist, rhetorician, educator, scholar, and Catholic priest. He is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis that proved that the '' ...

and Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, would help pave the way for the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

.

Well after the first artistic return to classicism had been exemplified in the sculpture of Nicola Pisano, Florentine painters led by Masaccio strove to portray the human form realistically, developing techniques to render perspective and light more naturally. Political philosophers, most famously Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

, sought to describe political life as it really was, that is to understand it rationally. A critical contribution to Italian Renaissance humanism, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (24 February 1463 – 17 November 1494) was an Italian Renaissance nobleman and philosopher. He is famed for the events of 1486, when, at the age of 23, he proposed to defend 900 theses on religion, philosophy, ...

wrote the famous text '' De hominis dignitate'' (''Oration on the Dignity of Man'', 1486), which consists of a series of theses on philosophy, natural thought, faith, and magic defended against any opponent on the grounds of reason. In addition to studying classical Latin and Greek, Renaissance authors also began increasingly to use vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

languages; combined with the introduction of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, this would allow many more people access to books, especially the Bible.

In all, the Renaissance could be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly, both through the revival of ideas from antiquity, and through novel approaches to thought. Some scholars, such as Rodney Stark, play down the Renaissance in favor of the earlier innovations of the Italian city-states in the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

, which married responsive government, Christianity and the birth of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

. This analysis argues that, whereas the great European states (France and Spain) were absolute monarchies

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

, and others were under direct Church control, the independent city-republics of Italy took over the principles of capitalism invented on monastic estates and set off a vast unprecedented Commercial Revolution that preceded and financed the Renaissance.

Origins

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in

Many argue that the ideas characterizing the Renaissance had their origin in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, in particular with the writings of Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

(1265–1321) and Petrarch (1304–1374), as well as the paintings of Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337). Some writers date the Renaissance quite precisely; one proposed starting point is 1401, when the rival geniuses Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi ( , , also known as Pippo; 1377 – 15 April 1446), considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture, was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor, and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, p ...

competed for the contract to build the bronze doors for the Baptistery

In Christian architecture the baptistery or baptistry ( Old French ''baptisterie''; Latin ''baptisterium''; Greek , 'bathing-place, baptistery', from , baptízein, 'to baptize') is the separate centrally planned structure surrounding the baptisma ...

of the Florence Cathedral (Ghiberti then won). Others see more general competition between artists and polymaths such as Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance st ...

, and Masaccio for artistic commissions as sparking the creativity of the Renaissance. Yet it remains much debated why the Renaissance began in Italy, and why it began when it did. Accordingly, several theories have been put forward to explain its origins.

During the Renaissance, money and art went hand in hand. Artists depended entirely on patrons while the patrons needed money to foster artistic talent. Wealth was brought to Italy in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries by expanding trade into Asia and Europe. Silver mining in Tyrol increased the flow of money. Luxuries from the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

, brought home during the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

, increased the prosperity of Genoa and Venice.

Jules Michelet defined the 16th-century Renaissance in France as a period in Europe's cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages, creating a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.

Latin and Greek phases of Renaissance humanism

In stark contrast to the

In stark contrast to the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

, when Latin scholars focused almost entirely on studying Greek and Arabic works of natural science, philosophy and mathematics, Renaissance scholars were most interested in recovering and studying Latin and Greek literary, historical, and oratorical texts. Broadly speaking, this began in the 14th century with a Latin phase, when Renaissance scholars such as Petrarch, Coluccio Salutati (1331–1406), Niccolò de' Niccoli (1364–1437), and Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) scoured the libraries of Europe in search of works by such Latin authors as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated in ...

, Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, and Seneca. By the early 15th century, the bulk of the surviving such Latin literature had been recovered; the Greek phase of Renaissance humanism was under way, as Western European scholars turned to recovering ancient Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts.

Unlike with Latin texts, which had been preserved and studied in Western Europe since late antiquity, the study of ancient Greek texts was very limited in medieval Western Europe. Ancient Greek works on science, mathematics, and philosophy had been studied since the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

in Western Europe and in the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

(normally in translation), but Greek literary, oratorical and historical works (such as Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the '' Iliad'' and the '' Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of ...

, the Greek dramatists, Demosthenes and Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scient ...

) were not studied in either the Latin or medieval Islamic worlds; in the Middle Ages these sorts of texts were only studied by Byzantine scholars. Some argue that the Timurid Renaissance in Samarkand and Herat, whose magnificence toned with Florence as the center of a cultural rebirth, were linked to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, whose conquests led to the migration of Greek scholars to Italian cities. One of the greatest achievements of Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.

Muslim logicians, most notably Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psych ...

, had inherited Greek ideas after they had invaded and conquered Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

. Their translations and commentaries on these ideas worked their way through the Arab West into Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula

A peninsula (; ) is a la ...

and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, which became important centers for this transmission of ideas. From the 11th to the 13th century, many schools dedicated to the translation of philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic to Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a Literary language, literary standard language, standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used f ...

were established in Iberia, most notably the Toledo School of Translators. This work of translation from Islamic culture, though largely unplanned and disorganized, constituted one of the greatest transmissions of ideas in history.''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society''Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret C. Jacob, James R. Jacob, 2008, pp. 261–262. The movement to reintegrate the regular study of Greek literary, historical, oratorical and theological texts back into the Western European curriculum is usually dated to the 1396 invitation from Coluccio Salutati to the Byzantine diplomat and scholar Manuel Chrysoloras (c. 1355–1415) to teach Greek in Florence. This legacy was continued by a number of expatriate Greek scholars, from Basilios Bessarion to

Leo Allatius

Leo Allatius (Greek: Λέων Αλλάτιος, ''Leon Allatios'', Λιωνής Αλάτζης, ''Lionis Allatzis''; Italian: ''Leone Allacci, Allacio''; Latin: ''Leo Allatius, Allacius''; c. 1586 – January 19, 1669) was a Greek scholar, theolog ...

.

Social and political structures in Italy

The unique political structures of

The unique political structures of Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

have led some to theorize that its unusual social climate allowed the emergence of a rare cultural efflorescence. Italy did not exist as a political entity in the early modern period. Instead, it was divided into smaller city-states and territories: the Kingdom of Naples controlled the south, the Republic of Florence and the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct Sovereignty, sovereign rule of ...

at the center, the Milanese and the Genoese

Genoese may refer to:

* a person from Genoa

* Genoese dialect, a dialect of the Ligurian language

* Republic of Genoa (–1805), a former state in Liguria

See also

* Genovese, a surname

* Genovesi, a surname

*

*

*

*

* Genova (disambiguati ...

to the north and west respectively, and the Venetians to the east. Fifteenth-century Italy was one of the most urbanized

''Urbanized'' is a documentary film directed by Gary Hustwit and released on 26 October 2011. It is considered the third of a three-part series on design known as the Design Trilogy; the first being '' Helvetica'', about the typeface, and the s ...

areas in Europe. Many of its cities stood among the ruins of ancient Roman buildings; it seems likely that the classical nature of the Renaissance was linked to its origin in the Roman Empire's heartland.

Historian and political philosopher Quentin Skinner points out that Otto of Freising (c. 1114–1158), a German bishop visiting north Italy during the 12th century, noticed a widespread new form of political and social organization, observing that Italy appeared to have exited from feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

so that its society was based on merchants and commerce. Linked to this was anti-monarchical thinking, represented in the famous early Renaissance fresco cycle '' The Allegory of Good and Bad Government'' by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (painted 1338–1340), whose strong message is about the virtues of fairness, justice, republicanism and good administration. Holding both Church and Empire at bay, these city republics were devoted to notions of liberty. Skinner reports that there were many defences of liberty such as the Matteo Palmieri (1406–1475) celebration of Florentine genius not only in art, sculpture and architecture, but "the remarkable efflorescence of moral, social and political philosophy that occurred in Florence at the same time".Skinner, Quentin, ''The Foundations of Modern Political Thought'', vol I: ''The Renaissance''; vol II: ''The Age of Reformation'', Cambridge University Press, p. 69

Even cities and states beyond central Italy, such as the Republic of Florence at this time, were also notable for their merchant republics, especially the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

. Although in practice these were oligarchical

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

, and bore little resemblance to a modern democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, they did have democratic features and were responsive states, with forms of participation in governance and belief in liberty. The relative political freedom they afforded was conducive to academic and artistic advancement.Burckhardt, Jacob, ''The Republics: Venice and Florence'', The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

'', translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878. Likewise, the position of Italian cities such as Venice as great trading centres made them intellectual crossroads.

Merchant

A merchant is a person who trades in commodities produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Historically, a merchant is anyone who is involved in business or trade. Merchants have operated for as long as indust ...

s brought with them ideas from far corners of the globe, particularly the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

. Venice was Europe's gateway to trade with the East, and a producer of fine glass, while Florence was a capital of textiles. The wealth such business brought to Italy meant large public and private artistic projects could be commissioned and individuals had more leisure time for study.

Black Death

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in

One theory that has been advanced is that the devastation in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

caused by the Black Death, which hit Europe between 1348 and 1350, resulted in a shift in the world view of people in 14th century Italy. Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

was particularly badly hit by the plague, and it has been speculated that the resulting familiarity with death caused thinkers to dwell more on their lives on Earth, rather than on spirituality and the afterlife. It has also been argued that the Black Death prompted a new wave of piety, manifested in the sponsorship of religious works of art. However, this does not fully explain why the Renaissance occurred specifically in Italy in the 14th century. The Black Death was a pandemic that affected all of Europe in the ways described, not only Italy. The Renaissance's emergence in Italy was most likely the result of the complex interaction of the above factors.Brotton, J., ''The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction'', OUP, 2006 .

The plague was carried by fleas on sailing vessels returning from the ports of Asia, spreading quickly due to lack of proper sanitation: the population of England, then about 4.2 million, lost 1.4 million people to the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium ('' Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as ...

. Florence's population was nearly halved in the year 1347. As a result of the decimation in the populace the value of the working class increased, and commoners came to enjoy more freedom. To answer the increased need for labor, workers traveled in search of the most favorable position economically.

The demographic decline due to the plague had economic consequences: the prices of food dropped and land values declined by 30–40% in most parts of Europe between 1350 and 1400. Landholders faced a great loss, but for ordinary men and women it was a windfall. The survivors of the plague found not only that the prices of food were cheaper but also that lands were more abundant, and many of them inherited property from their dead relatives.

The spread of disease was significantly more rampant in areas of poverty. Epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

s ravaged cities, particularly children. Plagues were easily spread by lice, unsanitary drinking water, armies, or by poor sanitation. Children were hit the hardest because many diseases, such as typhus and congenital syphilis, target the immune system, leaving young children without a fighting chance. Children in city dwellings were more affected by the spread of disease than the children of the wealthy.

The Black Death caused greater upheaval to Florence's social and political structure than later epidemics. Despite a significant number of deaths among members of the ruling classes, the government of Florence continued to function during this period. Formal meetings of elected representatives were suspended during the height of the epidemic due to the chaotic conditions in the city, but a small group of officials was appointed to conduct the affairs of the city, which ensured continuity of government.

Cultural conditions in Florence

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life that may have caused such a cultural movement. Many have emphasized the role played by the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Muge ...

, a banking family and later ducal ruling house, in patronizing and stimulating the arts. Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (; 1 January 1449 – 8 April 1492) was an Italian statesman, banker, ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic and the most powerful and enthusiastic patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Also known as Lorenzo ...

(1449–1492) was the catalyst for an enormous amount of arts patronage, encouraging his countrymen to commission works from the leading artists of Florence, including Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was insp ...

. Works by Neri di Bicci, Botticelli, da Vinci, and Filippino Lippi

Filippino Lippi (April 1457 – 18 April 1504) was an Italian painter working in Florence, Italy during the later years of the Early Renaissance and first few years of the High Renaissance.

Biography

Filippino Lippi was born in Prato, Tu ...

had been commissioned additionally by the Convent of San Donato in Scopeto in Florence.

The Renaissance was certainly underway before Lorenzo de' Medici came to power – indeed, before the Medici family itself achieved hegemony in Florentine society. Some historians have postulated that Florence was the birthplace of the Renaissance as a result of luck, i.e., because " Great Men" were born there by chance:Burckhardt, Jacob, ''The Development of the Individual'', The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

'', translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878. Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in

Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

. Arguing that such chance seems improbable, other historians have contended that these "Great Men" were only able to rise to prominence because of the prevailing cultural conditions at the time.

Characteristics

Humanism

In some ways,Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

was not a philosophy but a method of learning. In contrast to the medieval scholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

mode, which focused on resolving contradictions between authors, Renaissance humanists would study ancient texts in the original and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences ...

. Humanist education was based on the programme of ''Studia Humanitatis'', the study of five humanities: poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings ...

, grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structure, structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clause (linguistics), clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraint ...

, history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

, moral philosophy, and rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

. Although historians have sometimes struggled to define humanism precisely, most have settled on "a middle of the road definition... the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome". Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man ... the unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind".

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

and Thomas More revived the ideas of Greek and Roman thinkers and applied them in critiques of contemporary government, following the Islamic steps of Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, o ...

. Pico della Mirandola wrote the "manifesto" of the Renaissance, the '' Oration on the Dignity of Man'', a vibrant defence of thinking. Matteo Palmieri (1406–1475), another humanist, is most known for his work ''Della vita civile'' ("On Civic Life"; printed 1528), which advocated civic humanism, and for his influence in refining the Tuscan vernacular to the same level as Latin. Palmieri drew on Roman philosophers and theorists, especially Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, who, like Palmieri, lived an active public life as a citizen and official, as well as a theorist and philosopher and also Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintili ...

. Perhaps the most succinct expression of his perspective on humanism is in a 1465 poetic work ''La città di vita'', but an earlier work, ''Della vita civile'', is more wide-ranging. Composed as a series of dialogues set in a country house in the Mugello countryside outside Florence during the plague of 1430, Palmieri expounds on the qualities of the ideal citizen. The dialogues include ideas about how children develop mentally and physically, how citizens can conduct themselves morally, how citizens and states can ensure probity in public life, and an important debate on the difference between that which is pragmatically useful and that which is honest.

The humanists believed that it is important to transcend to the afterlife with a perfect mind and body, which could be attained with education. The purpose of humanism was to create a universal man whose person combined intellectual and physical excellence and who was capable of functioning honorably in virtually any situation. This ideology was referred to as the '' uomo universale'', an ancient Greco-Roman ideal. Education during the Renaissance was mainly composed of ancient literature and history as it was thought that the classics provided moral instruction and an intensive understanding of human behavior.

Humanism and libraries

A unique characteristic of some Renaissance libraries is that they were open to the public. These libraries were places where ideas were exchanged and where scholarship and reading were considered both pleasurable and beneficial to the mind and soul. As freethinking was a hallmark of the age, many libraries contained a wide range of writers. Classical texts could be found alongside humanist writings. These informal associations of intellectuals profoundly influenced Renaissance culture. Some of the richest "bibliophiles" built libraries as temples to books and knowledge. A number of libraries appeared as manifestations of immense wealth joined with a love of books. In some cases, cultivated library builders were also committed to offering others the opportunity to use their collections. Prominent aristocrats and princes of the Church created great libraries for the use of their courts, called "court libraries", and were housed in lavishly designed monumental buildings decorated with ornate woodwork, and the walls adorned with frescoes (Murray, Stuart A.P.).Art

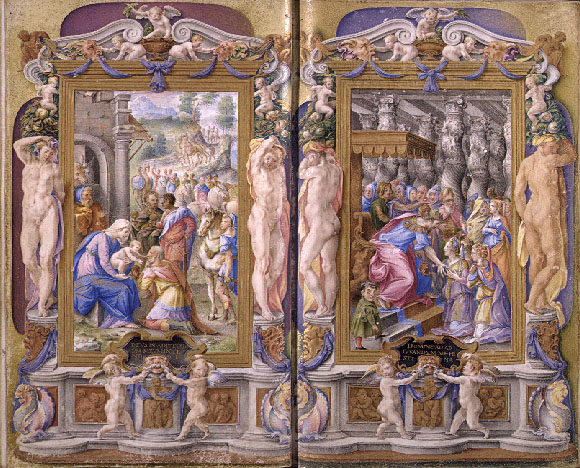

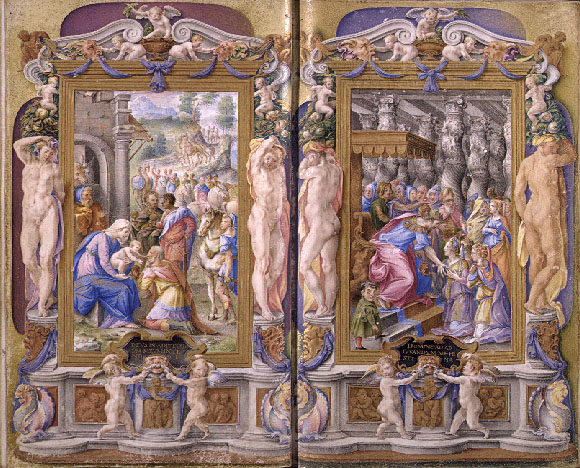

Renaissance art marks a cultural rebirth at the close of the Middle Ages and rise of the Modern world. One of the distinguishing features of Renaissance art was its development of highly realistic linear perspective. Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337) is credited with first treating a painting as a window into space, but it was not until the demonstrations of architectFilippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi ( , , also known as Pippo; 1377 – 15 April 1446), considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture, was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor, and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, p ...

(1377–1446) and the subsequent writings of Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) that perspective was formalized as an artistic technique.

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of

The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts. Painters developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially re ...

, human anatomy. Underlying these changes in artistic method was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, Epistemology, knowledge, Ethics, values, Philosophy of ...

, with the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

and Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

representing artistic pinnacles that were much imitated by other artists. Other notable artists include Sandro Botticelli, working for the Medici in Florence, Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), better known as Donatello ( ), was a Florentine sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used this to develop a complete Renaissance st ...

, another Florentine, and Titian

Tiziano Vecelli or Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian (Venetian) painter of the Renaissance, considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, n ...

in Venice, among others.

In the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, a particularly vibrant artistic culture developed. The work of Hugo van der Goes

Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440 – 1482) was one of the most significant and original Flemish painters of the late 15th century. Van der Goes was an important painter of altarpieces as well as portraits. He introduced important innovations in pai ...

and Jan van Eyck was particularly influential on the development of painting in Italy, both technically with the introduction of oil paint and canvas, and stylistically in terms of naturalism in representation. Later, the work of Pieter Brueghel the Elder would inspire artists to depict themes of everyday life.

In architecture, Filippo Brunelleschi was foremost in studying the remains of ancient classical buildings. With rediscovered knowledge from the 1st-century writer Vitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

and the flourishing discipline of mathematics, Brunelleschi formulated the Renaissance style that emulated and improved on classical forms. His major feat of engineering was building the dome of the Florence Cathedral. Another building demonstrating this style is the church of St. Andrew in Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

, built by Alberti. The outstanding architectural work of the High Renaissance was the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica, combining the skills of Bramante, Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was in ...

, Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

, Sangallo and Maderno.

During the Renaissance, architects aimed to use columns, pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

s, and entablatures as an integrated system. The Roman orders types of columns are used: Tuscan and Composite. These can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the Old Sacristy (1421–1440) by Brunelleschi. Arches, semi-circular or (in the Mannerist style) segmental, are often used in arcades, supported on piers or columns with capitals. There may be a section of entablature between the capital and the springing of the arch. Alberti was one of the first to use the arch on a monumental. Renaissance vaults do not have ribs; they are semi-circular or segmental and on a square plan, unlike the Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

vault, which is frequently rectangular.

Renaissance artists were not pagans, although they admired antiquity and kept some ideas and symbols of the medieval past. Nicola Pisano (c. 1220 – c. 1278) imitated classical forms by portraying scenes from the Bible. His ''Annunciation'', from the Baptistry at Pisa, demonstrates that classical models influenced Italian art before the Renaissance took root as a literary movement.

Science

Applied innovation extended to commerce. At the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli published the first work on

Applied innovation extended to commerce. At the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli published the first work on bookkeeping

Bookkeeping is the recording of financial transactions, and is part of the process of accounting in business and other organizations. It involves preparing source documents for all transactions, operations, and other events of a business. ...

, making him the founder of accounting.

The rediscovery of ancient texts and the invention of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

in about 1440 democratized learning and allowed a faster propagation of more widely distributed ideas. In the first period of the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the tra ...

, humanists favored the study of humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

over natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

or applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathemat ...

, and their reverence for classical sources further enshrined the Aristotelian and Ptolemaic views of the universe. Writing around 1450, Nicholas Cusanus

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (), was a German Catholic cardinal, philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renai ...

anticipated the heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

worldview of Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formula ...

, but in a philosophical fashion.

Science and art were intermingled in the early Renaissance, with polymath artists such as Leonardo da Vinci making observational drawings of anatomy and nature. Da Vinci set up controlled experiments in water flow, medical dissection, and systematic study of movement and aerodynamics, and he devised principles of research method that led Fritjof Capra to classify him as the "father of modern science". Other examples of Da Vinci's contribution during this period include machines designed to saw marbles and lift monoliths, and new discoveries in acoustics, botany, geology, anatomy, and mechanics.

A suitable environment had developed to question classical scientific doctrine. The discovery in 1492 of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

challenged the classical worldview. The works of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

(in geography) and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

(in medicine) were found to not always match everyday observations. As the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

and Counter-Reformation clashed, the Northern Renaissance showed a decisive shift in focus from Aristotelean natural philosophy to chemistry and the biological sciences (botany, anatomy, and medicine). The willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers resulted in a period of major scientific advancements.

Some view this as a "scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed ...

", heralding the beginning of the modern age, others as an acceleration of a continuous process stretching from the ancient world to the present day. Significant scientific advances were made during this time by Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He w ...

, Tycho Brahe, and Johannes Kepler. Copernicus, in ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The boo ...

'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), posited that the Earth moved around the Sun. '' De humani corporis fabrica'' (''On the Workings of the Human Body'') by Andreas Vesalius, gave a new confidence to the role of dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause ...

, observation, and the mechanistic view of anatomy.Brotton, J., "Science and Philosophy", ''The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction'' Oxford University Press