Synapsid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Synapsida is a diverse group of

Synapsids evolved a temporal fenestra behind each eye

Synapsids evolved a temporal fenestra behind each eye

Synapsids are characterized by having differentiated teeth. These include the canines,

Synapsids are characterized by having differentiated teeth. These include the canines,

In addition to the glandular skin covered in fur found in most modern mammals, modern and extinct synapsids possess a variety of modified skin coverings, including

In addition to the glandular skin covered in fur found in most modern mammals, modern and extinct synapsids possess a variety of modified skin coverings, including

See also the news item at (see below, however). More primitive members of the Cynodontia are also hypothesized to have had fur or a fur-like covering based on their inferred warm-blooded metabolism. While more direct evidence of fur in early cynodonts has been proposed in the form of small pits on the snout possibly associated with whiskers, such pits are also found in some reptiles that lack whiskers. There is evidence that some other non-mammalian cynodonts more basal than ''Castorocauda'', such as ''

Over the course of synapsid evolution, progenitor taxa at the start of adaptive radiations have tended to be derived carnivores. Synapsid adaptive radiations have generally occurred after extinction events that depleted the biosphere and left vacant niches open to be filled by newly evolved taxa. In non-mammaliaform synapsids, those taxa that gave rise to rapidly diversifying lineages have been both small and large in body size, although after the Late Triassic, progenitors of new synapsid lineages have generally been small, unspecialised generalists.

The earliest known synapsid '' Asaphestera'' coexisted with the earliest known sauropsid '' Hylonomus'' which lived during the

Over the course of synapsid evolution, progenitor taxa at the start of adaptive radiations have tended to be derived carnivores. Synapsid adaptive radiations have generally occurred after extinction events that depleted the biosphere and left vacant niches open to be filled by newly evolved taxa. In non-mammaliaform synapsids, those taxa that gave rise to rapidly diversifying lineages have been both small and large in body size, although after the Late Triassic, progenitors of new synapsid lineages have generally been small, unspecialised generalists.

The earliest known synapsid '' Asaphestera'' coexisted with the earliest known sauropsid '' Hylonomus'' which lived during the  The therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids, appeared during the Middle Permian and included the largest terrestrial animals in the Middle and Late Permian. They included herbivores and carnivores, ranging from small animals the size of a rat (e.g.: '' Robertia''), to large, bulky herbivores a ton or more in weight (e.g.: '' Moschops''). After flourishing for many millions of years, these successful animals were all but wiped out by the Permian–Triassic mass extinction about 250 mya, the largest known

The therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids, appeared during the Middle Permian and included the largest terrestrial animals in the Middle and Late Permian. They included herbivores and carnivores, ranging from small animals the size of a rat (e.g.: '' Robertia''), to large, bulky herbivores a ton or more in weight (e.g.: '' Moschops''). After flourishing for many millions of years, these successful animals were all but wiped out by the Permian–Triassic mass extinction about 250 mya, the largest known

Only a few therapsids went on to be successful in the new early

Only a few therapsids went on to be successful in the new early  Unlike the dicynodonts, which were large, the cynodonts became progressively smaller and more mammal-like as the Triassic progressed, though some forms like '' Trucidocynodon'' remained large. The first mammaliaforms evolved from the cynodonts during the early

Unlike the dicynodonts, which were large, the cynodonts became progressively smaller and more mammal-like as the Triassic progressed, though some forms like '' Trucidocynodon'' remained large. The first mammaliaforms evolved from the cynodonts during the early  Whether through climate change, vegetation change, ecological competition, or a combination of factors, most of the remaining large cynodonts (belonging to the Traversodontidae) and dicynodonts (of the family Kannemeyeriidae) had disappeared by the

Whether through climate change, vegetation change, ecological competition, or a combination of factors, most of the remaining large cynodonts (belonging to the Traversodontidae) and dicynodonts (of the family Kannemeyeriidae) had disappeared by the  During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, the remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were small, such as '' Tritylodon''. No cynodont grew larger than a cat. Most Jurassic and Cretaceous cynodonts were herbivorous, though some were

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, the remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were small, such as '' Tritylodon''. No cynodont grew larger than a cat. Most Jurassic and Cretaceous cynodonts were herbivorous, though some were

Synapsida - Pelycosauria

- at Palaeos

- includes description of important transitional genera in the evolutionary sequence linking primitive synapsids to mammals {{Authority control Tetrapod unranked clades Extant Pennsylvanian first appearances Taxa named by Henry Fairfield Osborn

tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s that includes all mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsid

Sauropsida ( Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds (which, as theropod dino ...

a (which includes all extant reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s and therefore, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s). Unlike other amniotes, synapsids have a single temporal fenestra, an opening low in the skull roof behind each eye socket, leaving a bony arch beneath each; this accounts for the name "synapsid". The distinctive temporal fenestra developed about 318 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

period, when synapsids and sauropsids diverged, but was subsequently merged with the orbit in early mammals.

The basal amniotes ( reptiliomorphs) from which synapsids evolved were historically simply called "reptiles". Therefore, stem group synapsids were then described as mammal-like reptiles in classical systematics, and non- therapsid synapsids were also referred to as pelycosaurs or pelycosaur- grade synapsids. These paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

terms have now fallen out of favor and are only used informally (if at all) in modern literature, as it is now known that all ''extant'' reptiles are more closely related to each other and birds than to synapsids, so the word "reptile" has been re-defined to mean only members of Sauropsida or even just an under-clade thereof. In a cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

sense, synapsids are in fact a monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

sister taxon of sauropsids, rather than a part of the sauropsid lineage. Therefore, calling synapsids "mammal-like reptiles" is incorrect under the ''new'' definition of "reptile", so they are now referred to as stem mammals, proto-mammals, paramammals or pan-mammals. Most lineages of pelycosaur-grade synapsids were replaced by the more advanced therapsids, which evolved from sphenacodontoid pelycosaurs, at the end of the Early Permian during the so-called Olson's Extinction

Olson's Extinction was a mass extinction that occurred in the late Cisuralian or early Guadalupian epoch of the Permian period, predating the much larger Permian–Triassic extinction event.

The event is named after American paleontologist E ...

.

Synapsids were the largest terrestrial vertebrates in the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

period (299 to 251 mya), rivalled only by some large pareiasaurian parareptile

Parareptilia ("near-reptiles") is an extinct group of Basal (phylogenetics), basal Sauropsida, sauropsids ("Reptile, reptiles"), traditionally considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia (the group that likely contains all living reptiles and birds ...

s such as '' Scutosaurus''. They were the dominant land predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s of the late Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

and early Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

, with eupelycosaurs such as ''Dimetrodon

''Dimetrodon'' ( or ; ) is an extinct genus of sphenacodontid synapsid that lived during the Cisuralian (Early Permian) Epoch (geology), epoch of the Permian period, around 295–272 million years ago. With most species measuring long and ...

'', '' Titanophoneus'' and '' Inostrancevia'' being the apex predator

An apex predator, also known as a top predator or superpredator, is a predator at the top of a food chain, without natural predators of its own.

Apex predators are usually defined in terms of trophic dynamics, meaning that they occupy the hig ...

s during the Permian, and theriodont

The theriodonts (clade Theriodontia) are a major group of therapsids which appeared during the Middle Permian and which includes the gorgonopsians and the eutheriodonts, itself including the therocephalians and the cynodonts.

Naming

In 1876, ...

s such as '' Moschorhinus'' during the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

. Synapsid population and diversity were severely reduced by the Capitanian mass extinction event and the Permian–Triassic extinction event

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (also known as the P–T extinction event, the Late Permian extinction event, the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian extinction event, and colloquially as the Great Dying,) was an extinction ...

, and only two groups of therapsids, the dicynodonts and eutheriodonts (consisting of therocephalians and cynodont

Cynodontia () is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 Megaannum, mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extin ...

s) are known to have survived into the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

. These therapsids rebounded as disaster taxa during the early Mesozoic, with the dicynodont '' Lystrosaurus'' making up as much as 95% of all land species at one time, but declined again after the Smithian–Spathian boundary event with their dominant niches largely taken over by the rise of archosaurian sauropsids, first by the pseudosuchians and then by the pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s. The cynodont group Probainognathia

Probainognathia is one of the two major subgroups of the clade Eucynodontia, the other being Cynognathia. The earliest forms were carnivorous and insectivorous, though some groups eventually also evolved herbivorous diets. The earliest and most b ...

, which includes the group Mammaliaformes, were the only synapsids to survive beyond the Triassic, and mammals are the only synapsid lineage that have survived past the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, having lived mostly nocturnally to avoid competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indi ...

with dinosaurs. After the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs, synapsids (as mammals) rose to dominance once again during the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

.

Linnaean and cladistic classifications

At the turn of the 20th century, synapsids were thought to be one of the four main subclasses ofreptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s. However, this notion was disproved upon closer inspection of skeletal remains, as synapsids are differentiated from reptiles by their distinctive temporal openings. These openings in the skull

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

bones allowed the attachment of larger jaw muscles, hence a more efficient bite.

Synapsids were subsequently considered to be a later reptilian lineage that became mammals by gradually evolving increasingly mammalian features, hence the name "mammal-like reptiles" (also known as pelycosaurs). These became the traditional terms for all Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

(early) synapsids. More recent studies have debunked this notion as well, and reptiles are now classified within Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

(sauropsids), the sister group to synapsids, thus making synapsids their own taxonomic group.

As a result, the paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

terms "mammal-like reptile" and "pelycosaur" are seen as outdated and disfavored in technical literature, and the term stem mammal (or sometimes protomammal or paramammal) is used instead. Phylogenetically

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

, it is now understood that synapsids comprise an independent branch of the tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythology, mythological, religion, religious, and philosophy, philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The ...

. The monophyly

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent comm ...

of Synapsida is not in doubt, and the expressions such as "Synapsida contains the mammals" and "synapsids gave rise to the mammals" both express the same phylogenetic hypothesis. This terminology reflects the modern cladistic

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

approach to animal relationships, according to which the only valid groups are those that include all of the descendants of a common ancestor: these are known as monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

groups, or clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s.

Additionally, Reptilia (reptiles) has been revised into a monophyletic group and is considered entirely distinct from Synapsida, falling within Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, the sister group of Synapsida within Amniota.

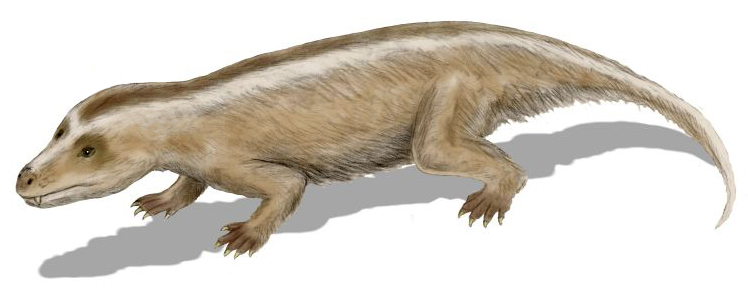

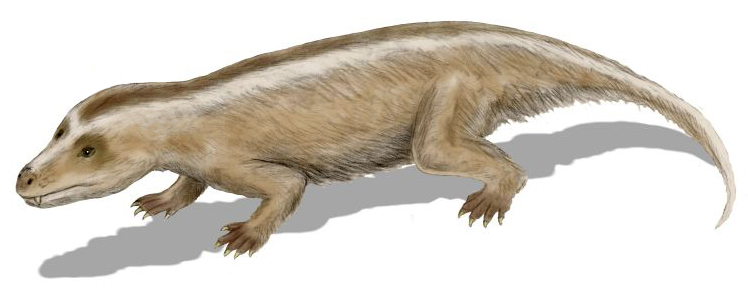

Primitive and advanced synapsids

The synapsids are traditionally divided for convenience, into therapsids, an advanced group of synapsids and the branch within which mammals evolved, and stem mammals, (previously known as pelycosaurs), comprising the other six more primitive families of synapsids. Stem mammals were all rather lizard-like, with sprawling gait and possibly hornyscute

A scute () or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "Scutum (shield), shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of Bird anatomy#Scales, birds. The ter ...

s, while therapsids tended to have a more erect pose and possibly hair, at least in some forms. In traditional taxonomy, the Synapsida encompasses two distinct grades: the low-slung stem mammals have given rise to the more erect therapsids, who in their turn have given rise to the mammals. In traditional vertebrate classification, the stem mammals and therapsids were both considered orders of the subclass Synapsida.

Practical versus phylogenetic usage of "synapsid" and "therapsid"

Inphylogenetic nomenclature

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional method, by which taxon names are defined by a '' type'', which c ...

, the terms are used somewhat differently, as the daughter clades are included. Most papers published during the 21st century have treated "Pelycosaur" as an informal grouping of primitive members. Therapsida has remained in use as a clade containing both the traditional therapsid families and mammals.

Although Synapsida and Therapsida include modern mammals, in practical usage, those two terms are used almost exclusively when referring to the more basal members that lie outside of Mammaliaformes.

Characteristics

Temporal openings

orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

on the lateral surface of the skull. It may have provided new attachment sites for jaw muscles. A similar development took place in the diapsids, which evolved two rather than one opening behind each eye. Originally, the openings in the skull left the inner cranium covered only by the jaw muscles, but in higher therapsids and mammals, the sphenoid bone

The sphenoid bone is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of occipital bone, basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bon ...

has expanded to close the opening. This has left the lower margin of the opening as an arch extending from the lower edges of the braincase.

Teeth

Synapsids are characterized by having differentiated teeth. These include the canines,

Synapsids are characterized by having differentiated teeth. These include the canines, molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

, and incisors. The trend towards differentiation is found in some labyrinthodonts and early anapsid reptilians in the form of enlargement of the first teeth on the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

, forming a sort of protocanines. This trait was subsequently lost in the diapsid line, but developed further in the synapsids. Early synapsids could have two or even three enlarged "canines", but in the therapsids, the pattern had settled to one canine in each upper jaw half. The lower canines developed later.

Jaw

The jaw transition is a goodclassification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

tool, as most other fossilized features that make a chronological progression from a reptile-like to a mammalian condition follow the progression of the jaw transition. The mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, or lower jaw, consists of a single, tooth-bearing bone in mammals (the dentary), whereas the lower jaw of modern and prehistoric reptiles consists of a conglomeration of smaller bones (including the dentary, articular, and others). As they evolved in synapsids, these jaw bones were reduced in size and either lost or, in the case of the articular, gradually moved into the ear, forming one of the middle ear bones: while modern mammals possess the malleus

The ''malleus'', or hammer, is a hammer-shaped small bone or ossicle of the middle ear. It connects with the incus, and is attached to the inner surface of the eardrum. The word is Latin for 'hammer' or 'mallet'. It transmits the sound vibra ...

, incus

The ''incus'' (: incudes) or anvil in the ear is one of three small bones (ossicles) in the middle ear. The incus receives vibrations from the malleus, to which it is connected laterally, and transmits these to the stapes medially. The incus i ...

and stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other tetrapods which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the f ...

, basal synapsids (like all other tetrapods) possess only a stapes. The malleus is derived from the articular (a lower jaw bone), while the incus is derived from the quadrate (a cranial bone).Salentijn, L. ''Biology of Mineralized Tissues: Prenatal Skull Development'', Columbia University College of Dental Medicine post-graduate dental lecture series, 2007

Mammalian jaw structures are also set apart by the dentary-squamosal jaw joint. In this form of jaw joint, the dentary forms a connection with a depression in the squamosal known as the glenoid cavity. In contrast, all other jawed vertebrates, including reptiles and nonmammalian synapsids, possess a jaw joint in which one of the smaller bones of the lower jaw, the articular, makes a connection with a bone of the cranium called the quadrate bone to form the articular-quadrate jaw joint. In forms transitional to mammals, the jaw joint is composed of a large, lower jaw bone (similar to the dentary found in mammals) that does not connect to the squamosal, but connects to the quadrate with a receding articular bone.

Palate

Over time, as synapsids became more mammalian and less 'reptilian', they began to develop asecondary palate

The secondary palate is an anatomical structure that divides the nasal cavity from the oral cavity in many vertebrates.

In human embryology, it refers to that portion of the hard palate that is formed by the growth of the two palatine shelves med ...

, separating the mouth and nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nas ...

. In early synapsids, a secondary palate began to form on the sides of the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

, still leaving the mouth and nostril connected.

Eventually, the two sides of the palate began to curve together, forming a U shape instead of a C shape. The palate also began to extend back toward the throat, securing the entire mouth and creating a full palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxilla, they comprise the hard palate.

Stru ...

. The maxilla is also closed completely. In fossils of one of the first eutheriodonts, the beginnings of a palate are clearly visible. The later '' Thrinaxodon'' has a full and completely closed palate, forming a clear progression.

Skin and fur

In addition to the glandular skin covered in fur found in most modern mammals, modern and extinct synapsids possess a variety of modified skin coverings, including

In addition to the glandular skin covered in fur found in most modern mammals, modern and extinct synapsids possess a variety of modified skin coverings, including osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amph ...

s (bony armor embedded in the skin), scute

A scute () or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "Scutum (shield), shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of Bird anatomy#Scales, birds. The ter ...

s (protective structures of the dermis often with a horny covering), hair or fur, and scale-like structures (often formed from modified hair, as in pangolin

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (). The one extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: '' Manis'', '' Phataginus'', and '' Smutsia''. ''Manis'' comprises four species found in Asia, while ' ...

s and some rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s). While the skin of reptiles is rather thin, that of mammals has a thick dermal

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided i ...

layer.

The ancestral skin type of synapsids has been subject to discussion. The type specimen of the oldest known synapsid '' Asaphestera'' preserved scales. Impressions of epidermal scales are preserved in the Early Permian 01 or 01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), ''01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Urban Zakapa album), ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''01011 ...

( Sakmarian) synapsid trace fossil ''Bromackerichnus requiescens'' from the Tambach Formation (Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

), the only known early synapsid body impression most likely belonging to a sphenacodontid based on its association with '' Dimetropus''. Among the early synapsids, only two species of small varanopids have been found to possess osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amph ...

s; fossilized rows of osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amph ...

s indicate bony armour on the neck and back. However, some recent studies have cast doubt on the placement of Varanopidae in Synapsida, while others have countered and lean towards this traditional placement. Skin impressions indicate some early synapsids basal possessed rectangular scutes on their undersides and tails. The pelycosaur scutes probably were nonoverlapping dermal

The dermis or corium is a layer of skin between the epidermis (with which it makes up the cutis) and subcutaneous tissues, that primarily consists of dense irregular connective tissue and cushions the body from stress and strain. It is divided i ...

structures with a horny overlay, like those found in modern crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large, semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term "crocodile" is sometimes used more loosely to include ...

s and turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s. These differed in structure from the scales of lizards and snakes, which are an epidermal feature (like mammalian hair or avian feathers). Recently, skin impressions from the genus '' Ascendonanus'' suggest that at least varanopsids developed scales similar to those of squamate

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

s.

It is currently unknown exactly when mammalian characteristics such as body hair and mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland that produces milk in humans and other mammals. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primates (for example, human ...

s first appeared, as the fossils only rarely provide direct evidence for soft tissues. An exceptionally well-preserved skull of '' Estemmenosuchus'', a therapsid from the Upper Permian, preserves smooth skin with what appear to be glandular depressions, an animal noted as being semi- aquatic. The oldest known fossil showing unambiguous imprints of hair is the Callovian (late middle Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

) ''Castorocauda

''Castorocauda'' is an extinct, semi-aquatic, superficially otter-like genus of docodont mammaliaforms with one species, ''C. lutrasimilis''. It is part of the Yanliao Biota, found in the Daohugou Beds of Inner Mongolia, China dating to the ...

'' and several contemporary haramiyida

Haramiyida is a possibly Paraphyly, paraphyletic order of Mammaliaformes, mammaliaform cynodonts or mammals of controversial taxonomic affinites. Their teeth, which are by far the most common remains, resemble those of the multituberculates. Howe ...

ns, both non-mammalian mammaliaform

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a clade of synapsid tetrapods that includes the crown group mammals and their closest extinct relatives; the group radiated from earlier probainognathian cynodonts during the Late Triassic. It is defined a ...

See also the news item at (see below, however). More primitive members of the Cynodontia are also hypothesized to have had fur or a fur-like covering based on their inferred warm-blooded metabolism. While more direct evidence of fur in early cynodonts has been proposed in the form of small pits on the snout possibly associated with whiskers, such pits are also found in some reptiles that lack whiskers. There is evidence that some other non-mammalian cynodonts more basal than ''Castorocauda'', such as ''

Morganucodon

''Morganucodon'' ("Glamorgan tooth") is an early mammaliaform genus that lived from the Late Triassic to the Middle Jurassic. It first appeared about 205 million years ago. Unlike many other early mammaliaforms, ''Morganucodon'' is well represent ...

'', had Harderian glands, which are associated with the grooming and maintenance of fur. The apparent absence of these glands in non-mammaliaformes may suggest that fur did not originate until that point in synapsid evolution. It is possible that fur and associated features of true warm-bloodedness did not appear until some synapsids became extremely small and nocturnal, necessitating a higher metabolism. The oldest examples of nocturnality in synapsids is believed to have been in species that lived more than 300 million years ago.

However, Late Permian coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name ...

s from Russia and possibly South Africa showcase that at least some synapsids did already have pre-mammalian hair in this epoch. These are the oldest impressions of hair-like structures on synapsids.

Mammary glands

Early synapsids, as far back as their known evolutionary debut in the Late Carboniferous period, may have laid parchment-shelled (leathery) eggs, which lacked a calcified layer, as most modern reptiles andmonotreme

Monotremes () are mammals of the order Monotremata. They are the only group of living mammals that lay eggs, rather than bearing live young. The extant monotreme species are the platypus and the four species of echidnas. Monotremes are typified ...

s do. This may also explain why there is no fossil evidence for synapsid eggs to date. Because they were vulnerable to desiccation, secretions from apocrine-like glands may have helped keep the eggs moist.

According to Oftedal, early synapsids may have buried the eggs into moisture laden soil, hydrating them with contact with the moist skin, or may have carried them in a moist pouch, similar to that of monotremes ( echidnas carry their eggs and offspring via a temporary pouch), though this would limit the mobility of the parent. The latter may have been the primitive form of egg care in synapsids rather than simply burying the eggs, and the constraint on the parent's mobility would have been solved by having the eggs "parked" in nests during foraging or other activities and periodically be hydrated, allowing higher clutch sizes than could fit inside a pouch (or pouches) at once, and large eggs, which would be cumbersome to carry in a pouch, would be easier to care for. The basis of Oftedal's speculation is the fact that many species of anurans can carry eggs or tadpoles attached to the skin, or embedded within cutaneous "pouches" and how most salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

s curl around their eggs to keep them moist, both groups also having glandular skin.

The glands involved in this mechanism would later evolve into true mammary glands with multiple modes of secretion in association with hair follicles. Comparative analyses of the evolutionary origin of milk constituents support a scenario in which the secretions from these glands evolved into a complex, nutrient-rich milk long before true mammals arose (with some of the constituents possibly predating the split between the synapsid and sauropsid

Sauropsida ( Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds (which, as theropod dino ...

lines). Cynodont

Cynodontia () is a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 Megaannum, mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Mammals are cynodonts, as are their extin ...

s were almost certainly able to produce this, which allowed a progressive decline of yolk mass and thus egg size, resulting in increasingly altricial

Precocial species in birds and mammals are those in which the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. They are normally nidifugous, meaning that they leave the nest shortly after birth or hatching. Altricial ...

hatchlings as milk became the primary source of nutrition, which is all evidenced by the small body size, the presence of epipubic bones, and limited tooth replacement in advanced cynodonts, as well as in mammaliaforms.

Patagia

Aerial locomotion first began in non-mammalianharamiyida

Haramiyida is a possibly Paraphyly, paraphyletic order of Mammaliaformes, mammaliaform cynodonts or mammals of controversial taxonomic affinites. Their teeth, which are by far the most common remains, resemble those of the multituberculates. Howe ...

n cynodonts, with ''Arboroharamiya

''Arboroharamiya'' is an extinct genus of mammaliaform from the Late Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Inner Mongolia, China. ''Arboroharamiya'' belongs to a group of mammaliaforms called Haramiyida. The genus contains three species: ''A. jenkins ...

'', '' Xianshou'', ''Maiopatagium

''Maiopatagium'' is an extinct genus of gliding euharamiyida, euharamiyids which existed in Asia during the Jurassic period. It possessed a patagium between its limbs and presumably had similar lifestyle to living Flying squirrel, flying squirrel ...

'' and ''Vilevolodon

''Vilevolodon'' is an extinct, monotypic genus of volant, arboreal euharamiyids from the Oxfordian age of the Late Jurassic of China. The type species is ''Vilevolodon diplomylos''. The genus name ''Vilevolodon'' references its gliding capabili ...

'' bearing exquisitely preserved, fur-covered wing membranes that stretch across the limbs and tail. Their fingers are elongated, similar to those of bats and colugos and likely sharing similar roles both as wing supports and to hang on tree branches.

Within true mammals, aerial locomotion first occurs in volaticotherian eutriconodont

Eutriconodonta is an order (biology), order of early mammals. Eutriconodonts existed in Asia (including Insular India, pre-contact India), Africa, Europe, North America, North and South America during the Jurassic and the Cretaceous periods. The ...

s. A fossil '' Volaticotherium'' has an exquisitely preserved furry patagium

The patagium (: patagia) is a membranous body part that assists an animal in obtaining lift when gliding or flying. The structure is found in extant and extinct groups of flying and gliding animals including bats, theropod dinosaurs (inclu ...

with delicate wrinkles and that is very extensive, "sandwiching" the poorly preserved hands and feet and extending to the base of the tail. '' Argentoconodon'', a close relative, shares a similar femur adapted for flight stresses, indicating a similar lifestyle.

Theria

Theria ( or ; ) is a scientific classification, subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the Placentalia, placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-lay ...

n mammals would only achieve powered flight and gliding long after these early aeronauts became extinct, with the earliest-known gliding metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

ns and bats evolving in the Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

.

Metabolism

Recently, it has been found that endothermy was developed as early as '' Ophiacodon'' in the late Carboniferous. The presence of fibrolamellar, a specialised type of bone that can grow quickly while maintaining a stable structure, shows that Ophiacodon would have used its high internal body temperature to fuel a fast growth comparable to modern endotherms.Evolutionary history

Over the course of synapsid evolution, progenitor taxa at the start of adaptive radiations have tended to be derived carnivores. Synapsid adaptive radiations have generally occurred after extinction events that depleted the biosphere and left vacant niches open to be filled by newly evolved taxa. In non-mammaliaform synapsids, those taxa that gave rise to rapidly diversifying lineages have been both small and large in body size, although after the Late Triassic, progenitors of new synapsid lineages have generally been small, unspecialised generalists.

The earliest known synapsid '' Asaphestera'' coexisted with the earliest known sauropsid '' Hylonomus'' which lived during the

Over the course of synapsid evolution, progenitor taxa at the start of adaptive radiations have tended to be derived carnivores. Synapsid adaptive radiations have generally occurred after extinction events that depleted the biosphere and left vacant niches open to be filled by newly evolved taxa. In non-mammaliaform synapsids, those taxa that gave rise to rapidly diversifying lineages have been both small and large in body size, although after the Late Triassic, progenitors of new synapsid lineages have generally been small, unspecialised generalists.

The earliest known synapsid '' Asaphestera'' coexisted with the earliest known sauropsid '' Hylonomus'' which lived during the Bashkirian

The Bashkirian is in the International Commission on Stratigraphy geologic timescale the lowest stage (stratigraphy), stage or oldest age (geology), age of the Pennsylvanian (geology), Pennsylvanian. The Bashkirian age lasted from to Mega annu ...

age of the Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

. It was one of many types of primitive synapsids that are now informally grouped together as stem mammals or sometimes as protomammals (previously known as pelycosaurs). The early synapsids spread and diversified, becoming the largest terrestrial animals in the latest Carboniferous and Early Permian 01 or 01 may refer to:

* The year 2001, or any year ending with 01

* The month of January

* 1 (number)

Music

* '01 (Richard Müller album), ''01'' (Richard Müller album), 2001

* 01 (Urban Zakapa album), ''01'' (Urban Zakapa album), 2011

* ''01011 ...

periods, ranging up to in length. They were sprawling, bulky, possibly cold-blooded, and had small brains. Some, such as ''Dimetrodon'', had large sails that might have helped raise their body temperature. A few relict groups lasted into the later Permian but, by the middle of the Late Permian, all had either died off or evolved into their successors, the therapsids.

The therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids, appeared during the Middle Permian and included the largest terrestrial animals in the Middle and Late Permian. They included herbivores and carnivores, ranging from small animals the size of a rat (e.g.: '' Robertia''), to large, bulky herbivores a ton or more in weight (e.g.: '' Moschops''). After flourishing for many millions of years, these successful animals were all but wiped out by the Permian–Triassic mass extinction about 250 mya, the largest known

The therapsids, a more advanced group of synapsids, appeared during the Middle Permian and included the largest terrestrial animals in the Middle and Late Permian. They included herbivores and carnivores, ranging from small animals the size of a rat (e.g.: '' Robertia''), to large, bulky herbivores a ton or more in weight (e.g.: '' Moschops''). After flourishing for many millions of years, these successful animals were all but wiped out by the Permian–Triassic mass extinction about 250 mya, the largest known extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

in Earth's history

The natural history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by consta ...

, possibly related to the Siberian Traps volcanic event.

Only a few therapsids went on to be successful in the new early

Only a few therapsids went on to be successful in the new early Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

landscape; they include '' Lystrosaurus'' and '' Cynognathus'', the latter of which appeared later in the Early Triassic. However, they were accompanied by the early archosaur

Archosauria () or archosaurs () is a clade of diapsid sauropsid tetrapods, with birds and crocodilians being the only extant taxon, extant representatives. Although broadly classified as reptiles, which traditionally exclude birds, the cladistics ...

s (soon to give rise to the dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s). Some of these archosaurs, such as '' Euparkeria'', were small and lightly built, while others, such as '' Erythrosuchus'', were as big as or bigger than the largest therapsids.

After the Permian extinction, the synapsids did not count more than three surviving clades. The first comprised the therocephalia

Therocephalia is an extinct clade of therapsids (mammals and their close extinct relatives) from the Permian and Triassic periods. The therocephalians ("beast-heads") are named after their large skulls, which, along with the structure of their te ...

ns, which only lasted the first 20 million years of the Triassic period. The second were specialised, beaked herbivores known as dicynodonts (such as the Kannemeyeriidae), which contained some members that reached large size (up to a tonne or more). And finally there were the increasingly mammal-like carnivorous, herbivorous, and insectivorous cynodonts, including the eucynodonts from the Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age (geology), age in the Early Triassic epoch (geology), epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the Lower Triassic series (stratigraphy), series. It spans the time betw ...

age, an early representative of which was ''Cynognathus''.

Unlike the dicynodonts, which were large, the cynodonts became progressively smaller and more mammal-like as the Triassic progressed, though some forms like '' Trucidocynodon'' remained large. The first mammaliaforms evolved from the cynodonts during the early

Unlike the dicynodonts, which were large, the cynodonts became progressively smaller and more mammal-like as the Triassic progressed, though some forms like '' Trucidocynodon'' remained large. The first mammaliaforms evolved from the cynodonts during the early Norian

The Norian is a division of the Triassic geological period, Period. It has the rank of an age (geology), age (geochronology) or stage (stratigraphy), stage (chronostratigraphy). It lasted from ~227.3 to Mya (unit), million years ago. It was prec ...

age of the Late Triassic, about 225 mya.

During the evolutionary succession from early therapsid to cynodont to eucynodont to mammal, the main lower jaw bone, the dentary, replaced the adjacent bones. Thus, the lower jaw gradually became just one large bone, with several of the smaller jaw bones migrating into the inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in the ...

and allowing sophisticated hearing.

Whether through climate change, vegetation change, ecological competition, or a combination of factors, most of the remaining large cynodonts (belonging to the Traversodontidae) and dicynodonts (of the family Kannemeyeriidae) had disappeared by the

Whether through climate change, vegetation change, ecological competition, or a combination of factors, most of the remaining large cynodonts (belonging to the Traversodontidae) and dicynodonts (of the family Kannemeyeriidae) had disappeared by the Rhaetian

The Rhaetian is the latest age (geology), age of the Triassic period (geology), Period (in geochronology) or the uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Triassic system (stratigraphy), System (in chronostratigraphy). It was preceded by the N ...

age, even before the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event

The Triassic–Jurassic (Tr-J) extinction event (TJME), often called the end-Triassic extinction, marks the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, . It represents one of five major extinction events during the Phanerozoic, profoundly ...

that killed off most of the large non-dinosaurian archosaurs. The remaining Mesozoic synapsids were small, ranging from the size of a shrew to the badger-like mammal '' Repenomamus''.

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, the remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were small, such as '' Tritylodon''. No cynodont grew larger than a cat. Most Jurassic and Cretaceous cynodonts were herbivorous, though some were

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, the remaining non-mammalian cynodonts were small, such as '' Tritylodon''. No cynodont grew larger than a cat. Most Jurassic and Cretaceous cynodonts were herbivorous, though some were carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose nutrition and energy requirements are met by consumption of animal tissues (mainly mu ...

. The family Tritheledontidae, which first appeared near the end of the Triassic, was carnivorous and persisted well into the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

. The other, Tritylodontidae, first appeared at the same time as the tritheledonts, but was herbivorous. This group became extinct at the end of the Early Cretaceous epoch. Dicynodonts are generally thought to have become extinct near the end of the Triassic period, but there was evidence this group survived, in the form of six fragments of fossil bone that were found in Cretaceous rocks of Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

, Australia. If true, it would mean there is a significant ghost lineage of Dicynodonts in Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

. However, these fossils were re-described in 2019 as being Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

in age, and possibly belonging to a diprotodontid marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

.

Today, the 5,500 species of living synapsids, known as the mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, include both aquatic (cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s) and flying ( bats) species, and the largest animal ever known to have existed (the blue whale

The blue whale (''Balaenoptera musculus'') is a marine mammal and a baleen whale. Reaching a maximum confirmed length of and weighing up to , it is the largest animal known ever to have existed. The blue whale's long and slender body can ...

). Humans are synapsids, as well. Most mammals are viviparous and give birth to live young rather than laying eggs with the exception being the monotreme

Monotremes () are mammals of the order Monotremata. They are the only group of living mammals that lay eggs, rather than bearing live young. The extant monotreme species are the platypus and the four species of echidnas. Monotremes are typified ...

s.

Triassic and Jurassic ancestors of living mammals, along with their close relatives, had high metabolic rates. This meant consuming food (generally thought to be insects) in much greater quantity. To facilitate rapid digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

, these synapsids evolved mastication

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is comminution, crushed and ground by the teeth. It is the first step in the process of digestion, allowing a greater surface area for digestive enzymes to break down the foods.

During the mast ...

(chewing) and specialized teeth that aided chewing. Limbs also evolved to move under the body instead of to the side, allowing them to breathe more efficiently during locomotion.

This helped make it possible to support their higher metabolic demands.

Relationships

Below is acladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

of the most commonly accepted phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

of synapsids, showing a long stem lineage including Mammalia and successively more basal clades such as Theriodontia, Therapsida and Sphenacodontia:

Most uncertainty in the phylogeny of synapsids lies among the earliest members of the group, including forms traditionally placed within Pelycosauria. As one of the earliest phylogenetic analyses, Brinkman & Eberth (1983) placed the family Varanopidae

Varanopidae is an extinct family (biology), family of amniotes known from the Late Carboniferous to Middle Permian that resembled monitor lizards (with the name of the group deriving from the monitor lizard genus ''Varanus'') and may have filled ...

with Caseasauria

Caseasauria is one of the two main clades of early synapsids, the other being the Eupelycosauria. Caseasaurs are currently known only from the Late Carboniferous and the Permian, and include two superficially different families, the small insect ...

as the most basal offshoot of the synapsid lineage. Reisz (1986) removed Varanopidae from Caseasauria, placing it in a more derived position on the stem. While most analyses find Caseasauria to be the most basal synapsid clade, Benson's analysis (2012) placed a clade containing Ophiacodontidae and Varanopidae as the most basal synapsids, with Caseasauria occupying a more derived position. Benson attributed this revised phylogeny to the inclusion of postcranial characteristics, or features of the skeleton other than the skull, in his analysis. When only cranial or skull features were included, Caseasauria remained the most basal synapsid clade. Below is a cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

modified from Benson's analysis (2012):

However, more recent examination of the phylogeny of basal synapsids, incorporating newly described basal caseids and eothyridids, returned Caseasauria to its position as the sister to all other synapsids. Brocklehurst et al. (2016) demonstrated that many of the postcranial characters used by Benson (2012) to unite Caseasauria with Sphenacodontidae and Edaphosauridae were absent in the newly discovered postcranial material of eothyridids, and were therefore acquired convergently.

See also

* Anapsid * Diapsid * Euryapsida * List of prehistoric mammals * Lists of synapsids * Mammal classification * Timeline of the evolutionary history of life *Vertebrate paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct vertebrates (animals with vertebrae and their descendants). It also t ...

Notes

References

Further reading

*External links

Synapsida - Pelycosauria

- at Palaeos

- includes description of important transitional genera in the evolutionary sequence linking primitive synapsids to mammals {{Authority control Tetrapod unranked clades Extant Pennsylvanian first appearances Taxa named by Henry Fairfield Osborn