Mesoamerican scripts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mesoamerica is a

Mesoamerica is a

The term was first used by the German

The term was first used by the German

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands,

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands,

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic is marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic is marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and

The Late Classic period (beginning c. 600 CE until 909 CE) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal's socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol,

The Late Classic period (beginning c. 600 CE until 909 CE) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal's socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol,

Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between c. 800/850 and c. 1000 CE. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of

Generally applied to the Maya area, the Terminal Classic roughly spans the time between c. 800/850 and c. 1000 CE. Overall, it generally correlates with the rise to prominence of

By roughly 6000 BCE,

By roughly 6000 BCE,

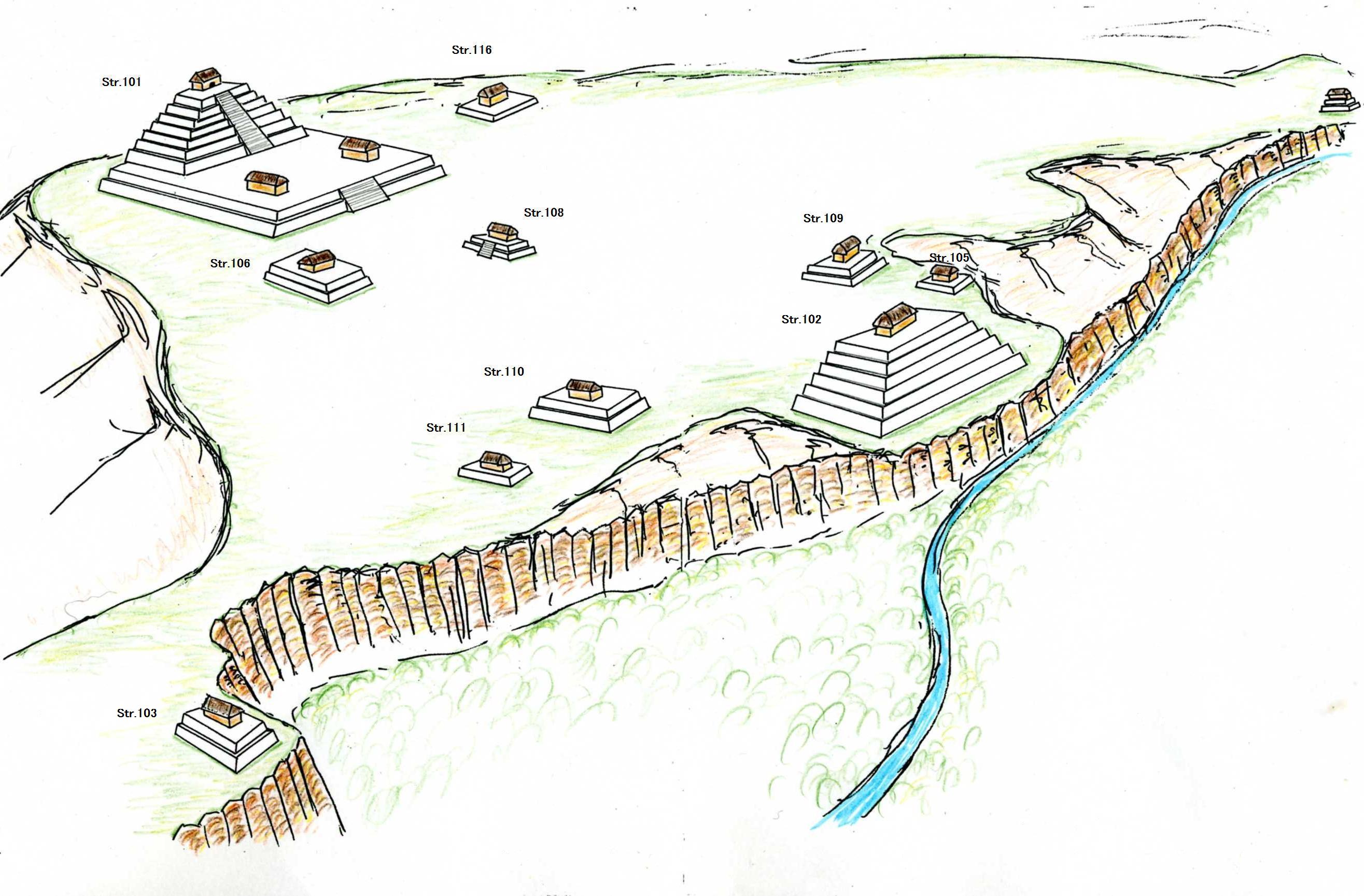

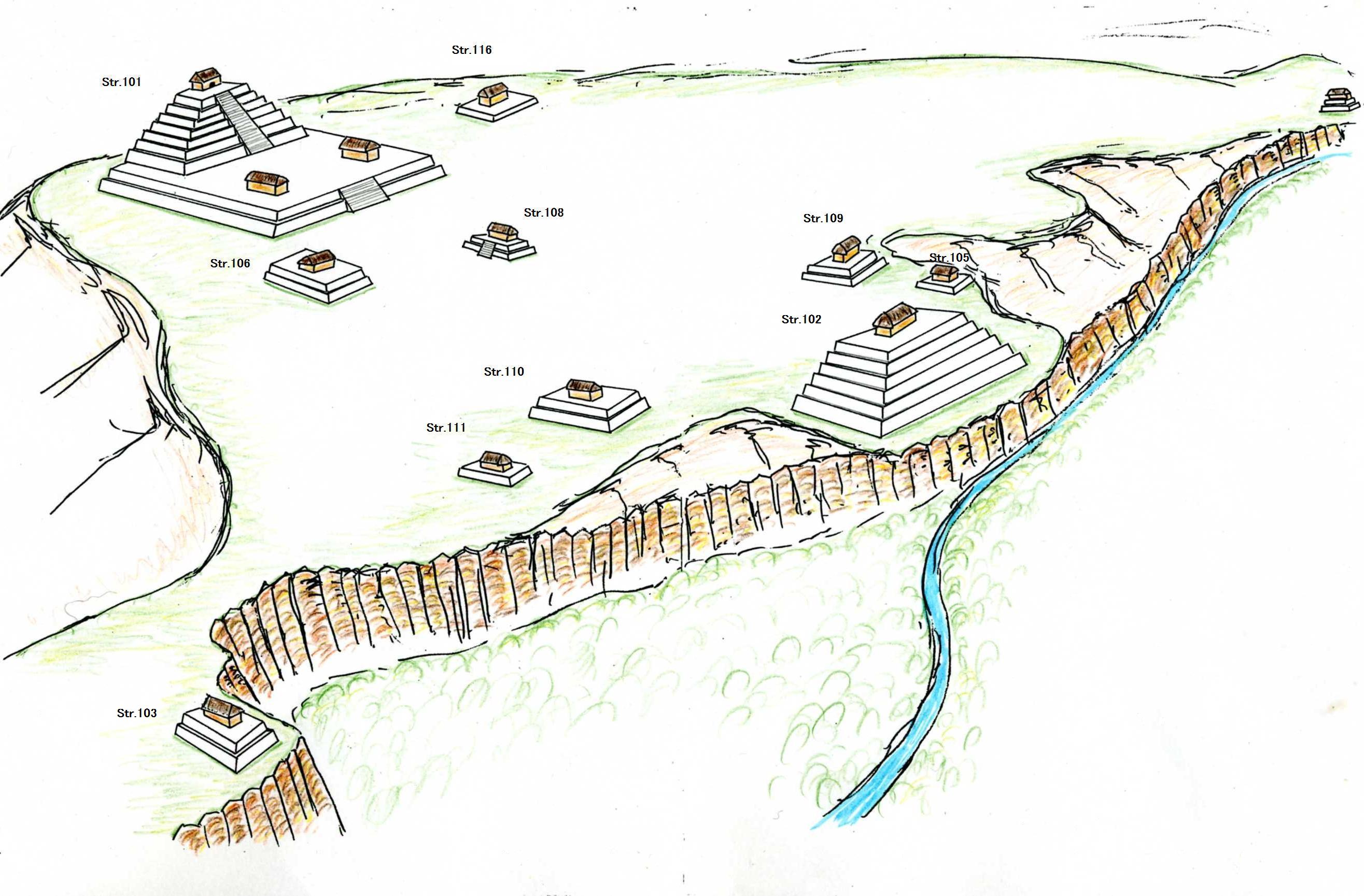

Ceremonial centers were the nuclei of Mesoamerican settlements. The temples provided spatial orientation, which was imparted to the surrounding town. The cities with their commercial and religious centers were always political entities, somewhat similar to the European

Ceremonial centers were the nuclei of Mesoamerican settlements. The temples provided spatial orientation, which was imparted to the surrounding town. The cities with their commercial and religious centers were always political entities, somewhat similar to the European

Mesoamerican architecture is the collective name given to urban, ceremonial and public structures built by pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica. Although very different in styles, all kinds of Mesoamerican architecture show some kind of interrelation, due to very significant cultural exchanges that occurred during thousands of years. Among the most well-known structures in Mesoamerica, the flat-top

Mesoamerican architecture is the collective name given to urban, ceremonial and public structures built by pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica. Although very different in styles, all kinds of Mesoamerican architecture show some kind of interrelation, due to very significant cultural exchanges that occurred during thousands of years. Among the most well-known structures in Mesoamerica, the flat-top

The great breadth of the Mesoamerican pantheon of

The great breadth of the Mesoamerican pantheon of

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played for over 3000 years by nearly all pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game,

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played for over 3000 years by nearly all pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modern version of the game,

It has been argued that among Mesoamerican societies the concepts of

It has been argued that among Mesoamerican societies the concepts of

Mesoamerican

Mesoamerican

*Americas

*Central America

*Hispanic America

*Hispanic and Latino Americans

*Indigenous peoples of Mexico

*Indigenous peoples of the Americas

*Latin America

*Mesoamerican region

*Middle America (Americas)

*Painting in the Americas before European colonization

Maya Culture

Mesoweb.com: a comprehensive site for Mesoamerican civilizations

Museum of the Templo Mayor

(Mexico)

National Museum of Anthropology and History

(Mexico)

concerning war in Mesoamerica

WAYEB: European Association of Mayanists

Open access international scientific journal devoted to the archaeological study of the American and Iberian peoples. It contains research articles on Mesoamerica. *

Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520–1820

' * {{Authority control Classic period in the Americas History of Indigenous peoples of North America History of Central America Indigenous peoples of Central America Indigenous peoples in Mexico Pre-Columbian cultural areas Cultural regions Historical regions Regions of North America

historical region

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

and cultural area

In anthropology and geography, a cultural area, cultural region, cultural sphere, or culture area refers to a geography with one relatively homogeneous human activity or complex of activities (culture). Such activities are often associa ...

that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, all of Belize

Belize is a country on the north-eastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a maritime boundary with Honduras to the southeast. P ...

, Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador's capital and largest city is S ...

, and parts of Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

, Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and northwestern part of Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

. As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures.

In the pre-Columbian era

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era, also known as the pre-contact era, or as the pre-Cabraline era specifically in Brazil, spans from the initial peopling of the Americas in the Upper Paleolithic to the onset of European col ...

, many indigenous societies flourished in Mesoamerica for more than 3,000 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas

The Spanish colonization of the Americas began in 1493 on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) after the initial 1492 voyage of Genoa, Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus under license from Queen Isabella ...

began on Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ) is an island between Geography of Cuba, Cuba and Geography of Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico in the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the second-largest by List of C ...

in 1493. In world history, Mesoamerica was the site of two historical transformations: (i) primary urban generation, and (ii) the formation of New World cultures from the mixtures of the indigenous Mesoamerican peoples with the European, African, and Asian peoples who were introduced by the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Mesoamerica is one of the six areas in the world where ancient civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

arose independently (see cradle of civilization

A cradle of civilization is a location and a culture where civilization was developed independent of other civilizations in other locations. A civilization is any complex society characterized by the development of the state, social strati ...

), and the second in the Americas, alongside the Caral–Supe in present-day Peru

Peru, officially the Republic of Peru, is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the south and west by the Pac ...

. Mesoamerica is also one of only five regions of the world where writing is known to have independently developed (the others being ancient Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization, located in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (now south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age, early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. ...

, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

).

Beginning as early as 7000 BCE, the domestication of cacao, maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

, beans

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are tradition ...

, tomato

The tomato (, ), ''Solanum lycopersicum'', is a plant whose fruit is an edible Berry (botany), berry that is eaten as a vegetable. The tomato is a member of the nightshade family that includes tobacco, potato, and chili peppers. It originate ...

, avocado

The avocado, alligator pear or avocado pear (''Persea americana'') is an evergreen tree in the laurel family (Lauraceae). It is native to Americas, the Americas and was first domesticated in Mesoamerica more than 5,000 years ago. It was priz ...

, vanilla

Vanilla is a spice derived from orchids of the genus ''Vanilla (genus), Vanilla'', primarily obtained from pods of the flat-leaved vanilla (''Vanilla planifolia, V. planifolia'').

''Vanilla'' is not Autogamy, autogamous, so pollination ...

, squash and chili, as well as the turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

and dog

The dog (''Canis familiaris'' or ''Canis lupus familiaris'') is a domesticated descendant of the gray wolf. Also called the domestic dog, it was selectively bred from a population of wolves during the Late Pleistocene by hunter-gatherers. ...

, resulted in a transition from paleo-Indian

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

hunter-gatherer tribal groupings to the organization of sedentary agricultural villages. In the subsequent Formative period, agriculture and cultural traits such as a complex mythological and religious tradition, a vigesimal

A vigesimal ( ) or base-20 (base-score) numeral system is based on 20 (number), twenty (in the same way in which the decimal, decimal numeral system is based on 10 (number), ten). ''wikt:vigesimal#English, Vigesimal'' is derived from the Latin a ...

numeric system, a complex calendric system, a tradition of ball playing, and a distinct architectural style

An architectural style is a classification of buildings (and nonbuilding structures) based on a set of characteristics and features, including overall appearance, arrangement of the components, method of construction, building materials used, for ...

, were diffused through the area. Villages began to become socially stratified and develop into chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political organization of people representation (politics), represented or government, governed by a tribal chief, chief. Chiefdoms have been discussed, depending on their scope, as a stateless society, stateless, state (polity) ...

s, and large ceremonial centers were built, interconnected by a network of trade routes for the exchange of luxury goods, such as obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

, jade

Jade is an umbrella term for two different types of decorative rocks used for jewelry or Ornament (art), ornaments. Jade is often referred to by either of two different silicate mineral names: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in t ...

, cacao, cinnabar

Cinnabar (; ), or cinnabarite (), also known as ''mercurblende'' is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and is t ...

, ''Spondylus

''Spondylus'' is a genus of bivalve molluscs, the only genus in the family Spondylidae and subfamily Spondylinae. They are known in English as spiny oysters or thorny oysters (although they are not, in fact, true oysters, but are related to sc ...

'' shells, hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

, and ceramics. While Mesoamerican civilization knew of the wheel

A wheel is a rotating component (typically circular in shape) that is intended to turn on an axle Bearing (mechanical), bearing. The wheel is one of the key components of the wheel and axle which is one of the Simple machine, six simple machin ...

and basic metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

, neither of these became technologically relevant.

Among the earliest complex civilizations was the Olmec

The Olmecs () or Olmec were an early known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing in the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from roughly 1200 to 400 Before the Common Era, BCE during Mesoamerica's Mesoamerican chronolog ...

culture, which inhabited the Gulf Coast of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and extended inland and southwards across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

. Frequent contact and cultural interchange between the early Olmec and other cultures in Chiapas

Chiapas, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas, is one of the states that make up the Political divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises Municipalities of Chiapas, 124 municipalities and its capital and large ...

, Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

, and Guatemala laid the basis for the Mesoamerican cultural area. All this was facilitated by considerable regional communications in ancient Mesoamerica, especially along the Pacific coast.

In the subsequent Preclassic period, complex urban polities began to develop among the Maya

Maya may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Mayan languages, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (East Africa), a p ...

, with the rise of centers such as Aguada Fénix and Calakmul

Calakmul (; also Kalakmul and other less frequent variants) is a Maya civilization, Maya archaeological site in the Mexican state of Campeche, deep in the jungles of the greater Petén Basin region. It is from the Guatemalan border. Calakmul w ...

in Mexico; El Mirador

El Mirador (which translates as "the lookout", "the viewpoint", or "the belvedere") is a large pre-Columbian Middle and Late Preclassic Maya, Preclassic (1000 BC – 250 AD) Maya civilization, Maya settlement, located in the north of the moder ...

, and Tikal

Tikal (; ''Tik'al'' in modern Mayan orthography) is the ruin of an ancient city, which was likely to have been called Yax Mutal, found in a rainforest in Guatemala. It is one of the largest archaeological sites and urban centers of the Pre-Col ...

in Guatemala, and the Zapotec at Monte Albán

Monte Albán is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Municipality in the southern Mexico, Mexican state of Oaxaca (17.043° N, 96.767°W). The site is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain i ...

. During this period, the first true Mesoamerican writing systems

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. Th ...

were developed in the Epi-Olmec and the Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic Maya logosyllabic script.

In Central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan (; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Teotihuacán'', ; ) is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, northeast of modern-day Mexico City.

Teotihuacan is ...

ascended at the height of the Classic period; it formed a military and commercial empire whose political influence stretched south into the Maya area and northward. Upon the collapse of Teotihuacán around 600 CE, competition between several important political centers in central Mexico, such as Xochicalco

Xochicalco () is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Miacatlán in the western part of the Mexican state of Morelos. The name ''Xochicalco'' may be translated from Nahuatl as "in the house of Flowers". The site is located 38 km southwest ...

and Cholula, ensued. At this time during the Epi-Classic period, the Nahua people

The Nahuas ( ) are a Uto-Aztecan languages, Uto-Nahuan ethnicity and one of the Indigenous people of Mexico, with Nahua minorities also in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. They comprise the largest Indigenous group i ...

s began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mexico, as they displaced speakers of Oto-Manguean languages

The Oto-Manguean or Otomanguean () languages are a large family comprising several subfamilies of indigenous languages of the Americas. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but the Manguean branch of th ...

.

During the early post-Classic period, Central Mexico was dominated by the Toltec

The Toltec culture () was a Pre-Columbian era, pre-Columbian Mesoamerican culture that ruled a state centered in Tula (Mesoamerican site), Tula, Hidalgo (state), Hidalgo, Mexico, during the Epiclassic and the early Post-Classic period of Mesoam ...

culture, and Oaxaca by the Mixtec

The Mixtecs (), or Mixtecos, are Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples of Mexico inhabiting the region known as La Mixteca of Oaxaca and Puebla as well as La Montaña Region and Costa Chica of Guerrero, Costa Chica Regions of the state of Guerre ...

. The lowland Maya area had important centers at Chichén Itzá and Mayapán. Towards the end of the post-Classic period, the Aztecs

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the ...

of Central Mexico built a tributary

A tributary, or an ''affluent'', is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream (''main stem'' or ''"parent"''), river, or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries, and the main stem river into which they ...

empire covering most of central Mesoamerica.

The distinct Mesoamerican cultural tradition ended with the Spanish conquest

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It ...

in the 16th century. Eurasian diseases such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, which were endemic among the colonists but new to North America, caused the deaths of upwards of 90% of the indigenous people, resulting in great losses to their societies and cultures. Over the next centuries, Mesoamerican indigenous cultures were gradually subjected to Spanish colonial rule. Aspects of the Mesoamerican cultural heritage still survive among the indigenous peoples who inhabit Mesoamerica. Many continue to speak their ancestral languages and maintain many practices hearkening back to their Mesoamerican roots.

Etymology and definition

The term ''Mesoamerica'' literally means "middle America" in Greek. Middle America often refers to a larger area in the Americas, but it has also previously been used more narrowly to refer to Mesoamerica. An example is the title of the 16 volumes of ''The Handbook of Middle American Indians''. "Mesoamerica" is broadly defined as the area that is home to the Mesoamerican civilization, which comprises a group of peoples with close cultural and historical ties. The exact geographic extent of Mesoamerica has varied through time, as the civilization extended North and South from its heartland in southern Mexico. The term was first used by the German

The term was first used by the German ethnologist

Ethnology (from the , meaning 'nation') is an academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).

Scien ...

Paul Kirchhoff

Paul Kirchhoff (17 August 1900, Halle, Province of Westphalia – 9 December 1972) was a German-Mexican anthropologist, most noted for his seminal work in defining and elaborating the culture area of Mesoamerica, a term he coined.

Early life ...

, who noted that similarities existed among the various pre-Columbian cultures within the region that included southern Mexico, Guatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, Belize

Belize is a country on the north-eastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a maritime boundary with Honduras to the southeast. P ...

, El Salvador

El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south by the Pacific Ocean. El Salvador's capital and largest city is S ...

, western Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

, and the Pacific lowlands of Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and northwestern Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

. In the tradition of cultural history

Cultural history records and interprets past events involving human beings through the social, cultural, and political milieu of or relating to the arts and manners that a group favors. Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897) helped found cultural history ...

, the prevalent archaeological theory

Archaeological theory refers to the various intellectual frameworks through which archaeology, archaeologists interpret archaeological data. Archaeological theory functions as the application of philosophy of science to archaeology, and is occasion ...

of the early to middle 20th century, Kirchhoff defined this zone as a cultural area based on a suite of interrelated cultural similarities brought about by millennia of inter- and intra-regional interaction (i.e., diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

). Mesoamerica is recognized as a near-prototypical cultural area. This term is now fully integrated into the standard terminology of precolumbian anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behaviour, wh ...

studies. Conversely, the sister terms Aridoamerica

Aridoamerica is a cultural and ecological region spanning Northern Mexico and the Southwestern United States, defined by the presence of the drought-resistant, culturally significant staple food, the tepary bean ('' Phaseolus acutifolius'').P ...

and Oasisamerica

Oasisamerica is a cultural region of Indigenous peoples in North America. Their precontact cultures were predominantly agrarian, in contrast with neighboring tribes to the south in Aridoamerica. The region spans parts of Northwestern Mexico an ...

, which refer to northern Mexico and the western United States, respectively, have not entered into widespread usage.

Some of the significant cultural traits defining the Mesoamerican cultural tradition are:

* ''Horticulture and plant use'': sedentism

In anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness; compare sedentarism) is the practice of living in one place for a long time. As of , the large majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and arch ...

based on maize

Maize (; ''Zea mays''), also known as corn in North American English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native American ...

agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

; floating gardens; use of bark paper and agave

''Agave'' (; ; ) is a genus of monocots native to the arid regions of the Americas. The genus is primarily known for its succulent and xerophytic species that typically form large Rosette (botany), rosettes of strong, fleshy leaves.

Many plan ...

(see also maguey) for ritual purposes, as a medium for writing, and the use of agave for cooking and clothing; cultivation of cacao; grinding of corn softened with ashes or lime; harpoon-shaped digging stick

* ''Clothing and personal articles'': lip plugs, mirrors of polished stone, turbans, sandals with heels, textiles adorned with rabbit hair

Rabbit hair (also called rabbit fur, cony, coney, comb or lapin) is the fur of the common rabbit. It is most commonly used in the making of fur hats and coats, and is considered quite valuable today, although it was once a lower-priced commodit ...

* ''Architecture'': construction of stepped pyramids; stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and ...

floors; ball courts with stone rings (see the use of natural rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

and the practice of the ritual Mesoamerican ballgame

The Mesoamerican ballgame (, , ) was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modernized ...

)

* ''Record keeping'': use of two different calendars

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A calendar date, date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is ...

(a 260-day ritual calendar and a 365-day calendar based on the solar year

A tropical year or solar year (or tropical period) is the time that the Sun takes to return to the same position in the sky – as viewed from the Earth or another celestial body of the Solar System – thus completing a full cycle of astronom ...

); use of locally developed pictographic

A pictogram (also pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto) is a graphical symbol that conveys meaning through its visual resemblance to a physical object. Pictograms are used in systems of writing and visual communication. A pictography is a wri ...

and hieroglyph

Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs ( ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined ideographic, logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with more than 1,000 distinct characters. ...

ic (logo-syllabic) writing systems

A writing system comprises a set of symbols, called a ''script'', as well as the rules by which the script represents a particular language. The earliest writing appeared during the late 4th millennium BC. Throughout history, each independe ...

; numbers (see also vigesimal

A vigesimal ( ) or base-20 (base-score) numeral system is based on 20 (number), twenty (in the same way in which the decimal, decimal numeral system is based on 10 (number), ten). ''wikt:vigesimal#English, Vigesimal'' is derived from the Latin a ...

(base 20) number system); "century" of fifty-two years; eighteen-month calendar; screen-fold books

* ''Commerce'': specialized markets, "department store" markets subdivided according to specialty

* ''Weapons and warfare'': wooden swords with stone chips set into the edges (see macuahuitl

A macuahuitl () is a weapon, a wooden sword with several embedded obsidian blades. The name is derived from the Nahuatl language and means "hand-wood". Its sides are embedded with prismatic blades traditionally made from obsidian, which is c ...

), military orders (eagle knights and jaguar knights), clay pellets for blowguns, cotton-pad armor, traveling merchants who act as spies, wars for the purpose of securing sacrificial victims

* ''Ritual and myth'': the practice of various forms of ritual sacrifice

Sacrifice is an act or offering made to a deity. A sacrifice can serve as propitiation, or a sacrifice can be an offering of praise and thanksgiving.

Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Gree ...

, including human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

and quail sacrifice; paper and rubber as sacrificial offerings; a pantheon of gods or spirits; acrobatic flier dance (see the Danza de los Voladores

The ''Danza de los Voladores'' (; "Dance of the Flyers"), or ''Palo Volador'' (; "flying pole"), is an ancient Mesoamerican ceremony/ritual still performed today, albeit in modified form, in isolated pockets in Mexico. It is believed to have ...

and the Totonac flier dance; 13 as a ritual number; ritual period of 20 x 13 = 260 days; the mythic concept of one or more afterworlds and the difficult journey in reaching them; good and bad omen days; a religious complex based on a combination of shamanism

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into ...

and natural deities, and a shared system of symbols

* ''Language'': a linguistic area

A sprachbund (, from , 'language federation'), also known as a linguistic area, area of linguistic convergence, or diffusion area, is a group of languages that share areal features resulting from geographical proximity and language contact. The ...

defined by a number of grammatical traits that have spread through the area by diffusion

Geography

Located on the Middle Americanisthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

joining North and South America between ''ca.'' 10° and 22° northern latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

, Mesoamerica possesses a complex combination of ecological systems, topographic zones, and environmental contexts. These different niches are classified into two broad categories: the lowlands (those areas between sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an mean, average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal Body of water, bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical ...

and 1000 meters) and the ''altiplanos'', or highlands (situated between 1,000 and 2,000 meters above sea level). In the low-lying regions, sub-tropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical and climate zones immediately to the north and south of the tropics. Geographically part of the temperate zones of both hemispheres, they cover the middle latitudes from to approximately 3 ...

and tropical climate

Tropical climate is the first of the five major climate groups in the Köppen climate classification identified with the letter A. Tropical climates are defined by a monthly average temperature of or higher in the coolest month, featuring hot te ...

s are most common, as is true for most of the coastline along the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere, located south of the Gulf of Mexico and southwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is bounded by the Greater Antilles to the north from Cuba ...

. The highlands show much more climatic diversity, ranging from dry tropical to cold mountainous climates; the dominant climate is temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ran ...

with warm temperatures and moderate rainfall. The rainfall varies from the dry Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

and north Yucatán

Yucatán, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Yucatán, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It comprises 106 separate municipalities, and its capital city is Mérida.

...

to the humid southern Pacific and Caribbean lowlands.

Cultural sub-areas

Several distinct sub-regions within Mesoamerica are defined by a convergence of geographic and cultural attributes. These sub-regions are more conceptual than culturally meaningful, and the demarcation of their limits is not rigid. The Maya area, for example, can be divided into two general groups: the lowlands and highlands. The lowlands are further divided into the southern and northern Maya lowlands. The southern Maya lowlands are generally regarded as encompassing northernGuatemala

Guatemala, officially the Republic of Guatemala, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically b ...

, southern Campeche

Campeche, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Campeche, is one of the 31 states which, with Mexico City, make up the Administrative divisions of Mexico, 32 federal entities of Mexico. Located in southeast Mexico, it is bordered by the sta ...

and Quintana Roo

Quintana Roo, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Quintana Roo, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, constitute the 32 administrative divisions of Mexico, federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into municipalities of ...

in Mexico, and Belize

Belize is a country on the north-eastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a maritime boundary with Honduras to the southeast. P ...

. The northern lowlands cover the remainder of the northern portion of the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula ( , ; ) is a large peninsula in southeast Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west of the peninsula from the C ...

. Other areas include Central Mexico, West Mexico, the Gulf Coast Lowlands, Oaxaca

Oaxaca, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca, is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of the Mexico, United Mexican States. It is divided into municipalities of Oaxaca, 570 munici ...

, the Southern Pacific Lowlands, and Southeast Mesoamerica (including northern Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

).

Topography

There is extensive topographic variation in Mesoamerica, ranging from the high peaks circumscribing theValley of Mexico

The Valley of Mexico (; ), sometimes also called Basin of Mexico, is a highlands plateau in central Mexico. Surrounded by mountains and volcanoes, the Valley of Mexico was a centre for several pre-Columbian civilizations including Teotihuacan, ...

and within the central Sierra Madre mountains to the low flatlands of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The tallest mountain in Mesoamerica is Pico de Orizaba

Citlaltépetl (from Nahuan languages, Náhuatl = star, and = mountain), otherwise known as Pico de Orizaba, is an active volcano, the highest mountain in Mexico and Table of the highest major summits of North America, third highest in North Ame ...

, a dormant volcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often ...

located on the border of Puebla

Puebla, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Puebla, is one of the 31 states that, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its capital is Puebla City. Part of east-centr ...

and Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

. Its peak elevation is 5,636 m (18,490 ft).

The Sierra Madre mountains, which consist of several smaller ranges, run from northern Mesoamerica south through Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

. The chain is historically volcanic

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often fo ...

. In central and southern Mexico, a portion of the Sierra Madre chain is known as the Eje Volcánico Transversal, or the Trans-Mexican volcanic belt. There are 83 inactive and active volcanoes within the Sierra Madre range, including 11 in Mexico, 37 in Guatemala, 23 in El Salvador, 25 in Nicaragua, and 3 in northwestern Costa Rica. According to the Michigan Technological University, 16 of these are still active. The tallest active volcano is Popocatépetl

Popocatépetl ( , , ; ) is an active stratovolcano located in the states of Puebla, Morelos, and Mexico in central Mexico. It lies in the eastern half of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. At it is the second highest peak in Mexico, after Ci ...

at 5,452 m (17,887 ft). This volcano, which retains its Nahuatl

Nahuatl ( ; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller popul ...

name, is located 70 km (43 mi) southeast of Mexico City. Other volcanoes of note include Tacana on the Mexico–Guatemala border, Tajumulco and Santamaría in Guatemala, Izalco

Izalco () is a town and a municipality in the Sonsonate department of El Salvador.

Volcan Izalco is an icon of the country of El Salvador, a very young volcano on the flank of Santa Ana volcano. From when it was born in 1770 until 1966, it wa ...

in El Salvador, Arenal in Costa Rica, Cerro Negro

Cerro Negro is an active volcano in the Cordillera de los Maribios mountain range in Nicaragua, about from the village of Malpaisillo. It is a very new volcano, the youngest in Central America, having first appeared in April 1850. It consist ...

, along with Concepción and Maderas on Ometepe

Ometepe is an island formed by two volcanoes rising out of Lake Nicaragua, located in the Rivas Department of the Republic of Nicaragua. Its name derives from the Nahuatl words ''ome'' (two) and ''tepetl'' (mountain), meaning "two mountains". It ...

, which is an island formed by both volcanoes rising out of Lake Cocibolca in Nicaragua.

One important topographic feature is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec () is an isthmus in Mexico. It represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, it was a major overland transport route known simply as the T ...

, a low plateau that breaks up the Sierra Madre chain between the Sierra Madre del Sur

The Sierra Madre del Sur is a mountain range in southern Mexico, extending from southern Michoacán east through Guerrero, to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in eastern Oaxaca.

Geography

The Sierra Madre del Sur joins with the Eje Volcánico Transv ...

to the north and the Sierra Madre de Chiapas

The Sierra Madre is a major mountain range in Central America. It is known as the Sierra Madre de Chiapas in Mexico. It crosses El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Honduras. The Sierra Madre is part of the American Cordillera, a chain of mountain ...

to the south. At its highest point, the Isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

is 224 m (735 ft) above mean sea level. This area also represents the shortest distance between the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and the Pacific Ocean in Mexico. The distance between the two coasts is roughly 200 km (120 mi). The northern side of the Isthmus is swampy and covered in dense jungle—but the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, as the lowest and most level point within the Sierra Madre mountain chain, was nonetheless a main transportation, communication, and economic route within Mesoamerica.

Bodies of water

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands,

Outside of the northern Maya lowlands, river

A river is a natural stream of fresh water that flows on land or inside Subterranean river, caves towards another body of water at a lower elevation, such as an ocean, lake, or another river. A river may run dry before reaching the end of ...

s are common throughout Mesoamerica. Some of the more important ones served as loci of human occupation in the area. The longest river in Mesoamerica is the Usumacinta, which forms in Guatemala at the convergence of the Salinas or Chixoy and La Pasión River

The Pasión River (, ) is a river located in the northern lowlands region of Guatemala. The river is fed by a number of upstream tributaries whose sources lie in the hills of Alta Verapaz. These flow in a general northerly direction to form the Pa ...

and runs north for 970 km (600 mi)—480 km (300 mi) of which are navigable—eventually draining into the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

. Other rivers of note include the Río Grande de Santiago

The Río Grande de Santiago, or Santiago River, is a river in western Mexico. It flows westwards from Lake Chapala via Ocotlán through the states of Jalisco and Nayarit to empty into the Pacific Ocean. It is one of the longest rivers in Mexic ...

, the Grijalva River

Grijalva River, formerly known as Tabasco River (, known locally also as Río Grande de Chiapas, Río Grande and Mezcalapa River), is a long river in southeastern Mexico."Grijalva." '' Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary'', 3rd ed. 2001. ...

, the Motagua River

The Motagua River () is a river in Guatemala. It rises in the Western Highlands of Guatemala and runs in an easterly direction to the Gulf of Honduras. The Motagua River basin covers an area of and is the largest in Guatemala.

The Motagua Riv ...

, the Ulúa River

The Ulúa River (, ) is a river in western Honduras. It rises in the central mountainous area of the country close to La Paz and runs approximately due northwards to the east end of the Gulf of Honduras at . En route, it is joined by the Sula ...

, and the Hondo River. The northern Maya lowlands, especially the northern portion of the Yucatán peninsula, are notable for their nearly complete lack of rivers (largely due to the absolute lack of topographic variation). Additionally, no lakes exist in the northern peninsula. The main source of water in this area is aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing material, consisting of permeability (Earth sciences), permeable or fractured rock, or of unconsolidated materials (gravel, sand, or silt). Aquifers vary greatly in their characteristics. The s ...

s that are accessed through natural surface openings called cenote

A cenote ( or ; ) is a natural pit, or sinkhole, resulting when a collapse of limestone bedrock exposes groundwater. The term originated on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, where the ancient Maya commonly used cenotes for water supplies, and ...

s.

With an area of 8,264 km2 (3,191 sq mi), Lake Cocibolca in Nicaragua is the largest lake in Mesoamerica, and second largest in all Latin America. Lake Chapala

Lake Chapala (, ) has been Mexico's largest freshwater lake since the desiccation of Lake Texcoco in the early 17th century.

It borders both the states of Jalisco and Michoacán, being located within the municipalities of Ocotlán, Jalisco, ...

is Mexico's largest freshwater lake, but Lake Texcoco

Lake Texcoco (; ) was a natural saline lake within the ''Anahuac'' or Valley of Mexico. Lake Texcoco is best known for an island situated on the western side of the lake where the Mexica built the city of Mēxihco Tenōchtitlan, which would la ...

is perhaps most well known as the location upon which Tenochtitlan

, also known as Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was a large Mexican in what is now the historic center of Mexico City. The exact date of the founding of the city is unclear, but the date 13 March 1325 was chosen in 1925 to celebrate the 600th annivers ...

, capital of the Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

Empire, was founded. Lake Petén Itzá, in northern Guatemala, is notable as where the last independent Maya city, Tayasal (or Noh Petén), held out against the Spanish until 1697. Other large lakes include Lake Atitlán, Lake Izabal

Lake Izabal (), also known as the Golfo Dulce, is the largest lake in Guatemala with a surface area of and a maximum depth of . The Polochic River is the largest river that drains into the lake. The lake, which is only a metre above sea level, ...

, Lake Güija, Lemoa and Lake Xolotlan.

Biodiversity

Almost allecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s are present in Mesoamerica; the more well known are the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System

The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (MBRS), also popularly known as the Great Mayan Reef or Great Maya Reef, is a marine region that stretches over along the coasts of four countries – Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras – from Isla Co ...

, the second largest in the world, and La Mosquitia (consisting of the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, Tawahka Asangni, Patuca National Park, and Bosawás Biosphere Reserve) a rainforest

Rainforests are forests characterized by a closed and continuous tree Canopy (biology), canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforests can be generally classified as tropi ...

second in size in the Americas only to the Amazonas. The highlands present mixed and coniferous

Conifers () are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a sin ...

forest. The biodiversity is among the richest in the world, though the number of species in the red list of the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

grows every year.

Chronology, culture and history

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the

The history of human occupation in Mesoamerica is divided into stages or periods. These are known, with slight variation depending on region, as the Paleo-Indian

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

, the Archaic, the Preclassic (or Formative), the Classic

A classic is an outstanding example of a particular style; something of Masterpiece, lasting worth or with a timeless quality; of the first or Literary merit, highest quality, class, or rank – something that Exemplification, exemplifies its ...

, and the Postclassic. The last three periods, representing the core of Mesoamerican cultural fluorescence, are further divided into two or three sub-phases. Most of the time following the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century is classified as the Colonial period.

The differentiation of early periods (i.e., up through the end of the Late Preclassic) generally reflects different configurations of socio-cultural organization that are characterized by increasing socio-political complexity, the adoption of new and different subsistence strategies, and changes in economic organization (including increased interregional interaction). The Classic

A classic is an outstanding example of a particular style; something of Masterpiece, lasting worth or with a timeless quality; of the first or Literary merit, highest quality, class, or rank – something that Exemplification, exemplifies its ...

period through the Postclassic are differentiated by the cyclical crystallization and fragmentation of the various political entities throughout Mesoamerica.

Paleo-Indian

The Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian period precedes the advent of agriculture and is characterized by a nomadichunting and gathering

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, especially wi ...

subsistence strategy. Big-game hunting, similar to that seen in contemporaneous North America, was a large component of the subsistence strategy of the Mesoamerican Paleo-Indian. These sites had obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

blades and Clovis

Clovis may refer to:

People

* Clovis (given name), the early medieval (Frankish) form of the name Louis

** Clovis I (c. 466 – 511), the first king of the Franks to unite all the Frankish tribes under one ruler

** Clovis II (c. 634 – c. 657), ...

-style fluted projectile point

In archaeological terminology, a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a weapon that was capable of being thrown or projected, such as a javelin, dart, or arrow. They are thus different from weapons presumed to have been kept in the ...

s.

Archaic

The Archaic period (8000–2000 BCE) is characterized by the rise of incipient agriculture in Mesoamerica. The initial phases of the Archaic involved the cultivation of wild plants, transitioning into informal domestication and culminating withsedentism

In anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness; compare sedentarism) is the practice of living in one place for a long time. As of , the large majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and arch ...

and agricultural production by the close of the period. Transformations of natural environments have been a common feature at least since the mid Holocene. Archaic sites include '' Sipacate'' in Escuintla

Escuintla () is an industrial city in Guatemala, its land extension is 4,384 km2, and it is nationally known for its sugar agribusiness. Its capital is a municipality with the same name. Citizens celebrate from December 6 to 9 with a small f ...

, Guatemala, where maize pollen samples date to c. 3500 BCE.

Preclassic/Formative

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the

The first complex civilization to develop in Mesoamerica was that of the Olmec

The Olmecs () or Olmec were an early known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing in the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from roughly 1200 to 400 Before the Common Era, BCE during Mesoamerica's Mesoamerican chronolog ...

, who inhabited the Gulf Coast region of Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

throughout the Preclassic period. The main sites of the Olmec include San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán or San Lorenzo is the collective name for three related archaeological sites—San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlán and Potrero Nuevo—located in the southeast portion of the Mexican state of Veracruz. Along with La Venta and Tre ...

, La Venta

La Venta is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Olmec civilization located in the present-day Mexican state of Tabasco. Some of the artifacts have been moved to the museum "Parque - Museo de La Venta", which is in nearby Villaherm ...

, and Tres Zapotes

Tres Zapotes is a Mesoamerican archaeological site located in the south-central Gulf Lowlands of Mexico in the Papaloapan River plain. Tres Zapotes is sometimes referred to as the third major Olmec capital (after San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La ...

. Specific dates vary, but these sites were occupied from roughly 1200 to 400 BCE. Remains of other early cultures interacting with the Olmec have been found at Takalik Abaj

Tak'alik Ab'aj (; ; ) is a pre-Columbian archaeological site in Guatemala. It was formerly known as Abaj Takalik; its ancient name may have been Kooja. It is one of several Mesoamerican sites with both Olmec and Maya features. The site flourishe ...

, Izapa

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it is best known for its occupation during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, ...

, and Teopantecuanitlan

Teopantecuanitlan is an archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero that represents an unexpectedly early development of complex society for the region. The site dates to the Early to Middle Formative Periods, with the archaeological ...

, and as far south as in Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

. Research in the Pacific Lowlands of Chiapas and Guatemala suggest that Izapa

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it is best known for its occupation during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, ...

and the Monte Alto Culture

Monte Alto is an archaeological site on the Pacific Coast in what is now Guatemala.

History

Located 20 km southeast from Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa in Escuintla, Monte Alto was occupied as early as 1800 BC, but has a fairly light presen ...

may have preceded the Olmec. Radiocarbon samples associated with various sculptures found at the Late Preclassic site of Izapa

Izapa is a very large pre-Columbian archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Chiapas; it is best known for its occupation during the Late Formative period. The site is situated on the Izapa River, a tributary of the Suchiate River, ...

suggest a date of between 1800 and 1500 BCE.

During the Middle and Late Preclassic period, the Maya civilization

The Maya civilization () was a Mesoamerican civilization that existed from antiquity to the early modern period. It is known by its ancient temples and glyphs (script). The Maya script is the most sophisticated and highly developed writin ...

developed in the southern Maya highlands and lowlands, and at a few sites in the northern Maya lowlands. The earliest Maya sites coalesced after 1000 BCE, and include Nakbe, El Mirador

El Mirador (which translates as "the lookout", "the viewpoint", or "the belvedere") is a large pre-Columbian Middle and Late Preclassic Maya, Preclassic (1000 BC – 250 AD) Maya civilization, Maya settlement, located in the north of the moder ...

, and Cerros. Middle to Late Preclassic Maya sites include Kaminaljuyú

Kaminaljuyu (pronounced ; from Kʼicheʼ language, Kʼicheʼʼ, "The Hill of the Dead") is a Pre-Columbian site of the Maya civilization located in History of Guatemala City, Guatemala City. Primarily occupied from 1500 BC to 1200 AD, it has been ...

, Cival, Edzná

Edzná ("House of the Itzaes") is a Mayan archaeological site in the north of the Mexican state of Campeche. The site has been open to visitors since the 1970s.

The most remarkable building at the site is the main temple located at the plaza. ...

, Cobá, Lamanai, Komchen, Dzibilchaltun, and San Bartolo, among others.

The Preclassic in the central Mexican highlands is represented by such sites as Tlapacoya, Tlatilco

Tlatilco was a large pre-Columbian village in the Valley of Mexico situated near the modern-day town of the same name in the Mexican Federal District. It was one of the first chiefdom centers to arise in the Valley, flourishing on the western sho ...

, and Cuicuilco

Cuicuilco is an important archaeological site located on the southern shore of Lake Texcoco in the southeastern Valley of Mexico, in what is today the borough of Tlalpan in Mexico City.

Construction of the Cuicuilco pyramid began a few centuri ...

. These sites were eventually superseded by Teotihuacán

Teotihuacan (; Spanish: ''Teotihuacán'', ; ) is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, northeast of modern-day Mexico City.

Teotihuacan is known today as ...

, an important Classic-era site that eventually dominated economic and interaction spheres throughout Mesoamerica. The settlement of Teotihuacan is dated to the later portion of the Late Preclassic, or roughly 50 CE.

In the Valley of Oaxaca

The Central Valleys () of Oaxaca, also simply known as the Oaxaca Valley, is a geographic region located within the modern-day state of Oaxaca in southeastern Mexico. In an administrative context, it has been defined as comprising the districts of ...

, San José Mogote

San José Mogote is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Zapotec civilization, Zapotec, a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in the region of what is now the Mexico, Mexican States of Mexico, state of Oaxaca. A forerunner to the better- ...

represents one of the oldest permanent agricultural villages in the area, and one of the first to use pottery. During the Early and Middle Preclassic, the site developed some of the earliest examples of defensive palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a row of closely placed, high vertical standing tree trunks or wooden or iron stakes used as a fence for enclosure or as a defensive wall. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymo ...

s, ceremonial structures, the use of adobe

Adobe (from arabic: الطوب Attub ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for mudbrick. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is use ...

, and hieroglyphic writing. Also of importance, the site was one of the first to demonstrate inherited status, signifying a radical shift in socio-cultural and political structure. San José Mogote was eventually overtaken by Monte Albán

Monte Albán is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Municipality in the southern Mexico, Mexican state of Oaxaca (17.043° N, 96.767°W). The site is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain i ...

, the subsequent capital of the Zapotec empire, during the Late Preclassic.

The Preclassic in western Mexico, in the states of Nayarit

Nayarit, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Nayarit, is one of the 31 states that, along with Mexico City, comprise the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in Municipalities of Nayarit, 20 municipalit ...

, Jalisco

Jalisco, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. It is located in western Mexico and is bordered by s ...

, Colima

Colima, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Colima, is among the 31 states that make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It shares its name with its capital and main city, Colima.

Colima is a small state of western Mexico on the cen ...

, and Michoacán

Michoacán, formally Michoacán de Ocampo, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Michoacán de Ocampo, is one of the 31 states which, together with Mexico City, compose the Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entities of Mexico. The stat ...

also known as the Occidente, is poorly understood. This period is best represented by the thousands of figurines recovered by looters and ascribed to the " shaft tomb tradition".

Classic

Early Classic

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic is marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and

The Classic period is marked by the rise and dominance of several polities. The traditional distinction between the Early and Late Classic is marked by their changing fortune and their ability to maintain regional primacy. Of paramount importance are Teotihuacán in central Mexico and Tikal

Tikal (; ''Tik'al'' in modern Mayan orthography) is the ruin of an ancient city, which was likely to have been called Yax Mutal, found in a rainforest in Guatemala. It is one of the largest archaeological sites and urban centers of the Pre-Col ...

in Guatemala; the Early Classic's temporal limits generally correlate to the main periods of these sites. Monte Albán in Oaxaca is another Classic-period polity that expanded and flourished during this period, but the Zapotec capital exerted less interregional influence than the other two sites.

During the Early Classic, Teotihuacan participated in and perhaps dominated a far-reaching macro-regional interaction network. Architectural and artifact styles (talud-tablero, tripod slab-footed ceramic vessels) epitomized at Teotihuacan were mimicked and adopted at many distant settlements. Pachuca

Pachuca (; ), formally known as Pachuca de Soto, is the capital and largest city of the east-central Mexico, Mexican States of Mexico, state of Hidalgo (state), Hidalgo, located in the south-central part of the state. Pachuca Municipality, Pach ...

obsidian, whose trade and distribution is argued to have been economically controlled by Teotihuacan, is found throughout Mesoamerica.

Tikal came to dominate much of the southern Maya lowlands politically, economically, and militarily during the Early Classic. An exchange network centered at Tikal distributed a variety of goods and commodities throughout southeast Mesoamerica, such as obsidian imported from central Mexico (e.g., Pachuca) and highland Guatemala (e.g., El Chayal, which was predominantly used by the Maya during the Early Classic), and jade

Jade is an umbrella term for two different types of decorative rocks used for jewelry or Ornament (art), ornaments. Jade is often referred to by either of two different silicate mineral names: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in t ...

from the Motagua valley in Guatemala. Tikal was often in conflict with other polities in the Petén Basin

The Petén Basin is a geographical subregion of the Maya Lowlands, primarily located in northern Guatemala within the Department of El Petén, and into the state of Campeche in southeastern Mexico.

During the Late Preclassic and Classic periods ...

, as well as with others outside of it, including Uaxactun

Uaxactun (pronounced ) is an ancient sacred place of the Maya civilization, located in the Petén Basin region of the Maya lowlands, in the present-day department of Petén, Guatemala. The site lies some north of the major center of Tikal. Th ...

, Caracol

Caracol is a large ancient Maya archaeological site, located in what is now the Cayo District of Belize. It is situated approximately south of Xunantunich, and the town of San Ignacio, and from the Macal River. It rests on the Vaca Plateau, ...

, Dos Pilas

Dos Pilas is a Pre-Columbian site of the Maya civilization located in what is now the department of Petén, Guatemala. It dates to the Late Classic Period, and was founded by an offshoot of the dynasty of the great city of Tikal in AD 6 ...

, Naranjo

Naranjo (Wak Kab'nal in Mayan) is a Pre-Columbian Maya city in the Petén Basin region of Guatemala. It was occupied from about 500 BC to 950 AD, with its height in the Late Classic Period. The site is part of Yaxha-Nakum-Naranjo National Park. ...

, and Calakmul

Calakmul (; also Kalakmul and other less frequent variants) is a Maya civilization, Maya archaeological site in the Mexican state of Campeche, deep in the jungles of the greater Petén Basin region. It is from the Guatemalan border. Calakmul w ...

. Towards the end of the Early Classic, this conflict lead to Tikal's military defeat at the hands of Caracol in 562, and a period commonly known as the Tikal Hiatus.

Late Classic

The Late Classic period (beginning c. 600 CE until 909 CE) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal's socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol,

The Late Classic period (beginning c. 600 CE until 909 CE) is characterized as a period of interregional competition and factionalization among the numerous regional polities in the Maya area. This largely resulted from the decrease in Tikal's socio-political and economic power at the beginning of the period. It was therefore during this time that other sites rose to regional prominence and were able to exert greater interregional influence, including Caracol, Copán

Copán is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization in the Copán Department of western Honduras, not far from the border with Guatemala. It is one of the most important sites of the Maya civilization, which was not excavated until the ...

, Palenque

Palenque (; Yucatec Maya: ), also anciently known in the Itza Language as Lakamha ("big water" or "big waters"), was a Maya city-state in southern Mexico that perished in the 8th century. The Palenque ruins date from ca. 226 BC to ca. 799 AD ...

, and Calakmul (which was allied with Caracol and may have assisted in the defeat of Tikal), and Dos Pilas

Dos Pilas is a Pre-Columbian site of the Maya civilization located in what is now the department of Petén, Guatemala. It dates to the Late Classic Period, and was founded by an offshoot of the dynasty of the great city of Tikal in AD 6 ...

Aguateca

Aguateca is a Maya site located in northern Guatemala's Petexbatun Basin, in the department of Petén. The first settlements at Aguateca date to the Late Preclassic period (300 BC - AD 350). The center was occupied from about 200 B.C. unti ...