Kingdom Of France (1791–1792) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

For most of the reign of

For most of the reign of

The reign (1715–1774) of

The reign (1715–1774) of

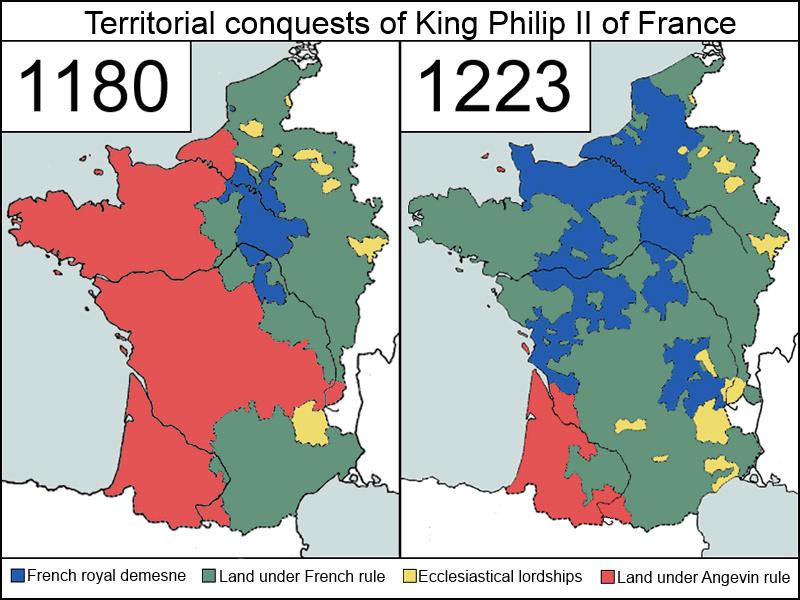

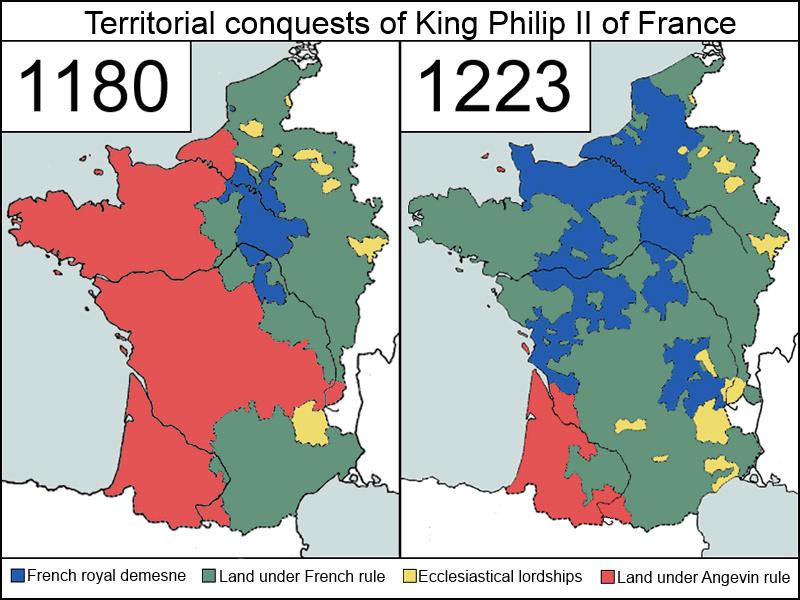

Before the 13th century, only a small part of what is now France was under control of the Frankish king; in the north there were Viking incursions leading to the formation of the

Before the 13th century, only a small part of what is now France was under control of the Frankish king; in the north there were Viking incursions leading to the formation of the

excerpt and text search

* Caron, François. ''An Economic History of Modern France'' (1979

online edition

* Doyle, William. ''Old Regime France: 1648–1788'' (2001

excerpt and text search

* Duby, Georges. ''France in the Middle Ages 987–1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc'' (1993), survey by a leader of the Annales Schoo

excerpt and text search

* Fierro, Alfred. ''Historical Dictionary of Paris'' (1998) 392pp, an abridged translation of his ''Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris'' (1996), 1580pp * Goubert, Pierre. ''The Course of French History'' (1991), standard French textboo

excerpt and text search

als

complete text online

* Goubert, Pierre. ''Louis XIV and Twenty Million Frenchmen'' (1972), social history from Annales School * Haine, W. Scott. ''The History of France'' (2000), 280 pp. textbook

and text search

als

online edition

* * Holt, Mack P. ''Renaissance and Reformation France: 1500–1648'' (2002

excerpt and text search

* Jones, Colin, and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie. ''The Cambridge Illustrated History of France'' (1999

excerpt and text search

* Jones, Colin. ''The Great Nation: France from Louis XV to Napoleon'' (2002

excerpt and text search

* Jones, Colin. ''Paris: Biography of a City'' (2004), 592pp; comprehensive history by a leading British schola

excerpt and text search

* Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. ''The Ancien Régime: A History of France 1610–1774'' (1999), survey by leader of the Annales Schoo

excerpt and text search

* * Potter, David. ''France in the Later Middle Ages 1200–1500,'' (2003

excerpt and text search

* Potter, David. ''A History of France, 1460–1560: The Emergence of a Nation-State'' (1995) * Price, Roger. ''A Concise History of France'' (1993

excerpt and text search

* Raymond, Gino. ''Historical Dictionary of France'' (2nd ed. 2008) 528pp * Roche, Daniel. ''France in the Enlightenment'' (1998), wide-ranging history 1700–178

excerpt and text search

* Wolf, John B. ''Louis XIV'' (1968), the standard scholarly biograph

online edition

excerpt and text search vol 2 excerptsvol 3 excerpts

* Pinkney, David H. "Two Thousand Years of Paris", ''Journal of Modern History'' (1951) 23#3 pp. 262–26

in JSTOR

* Revel, Jacques, and Lynn Hunt, eds. ''Histories: French Constructions of the Past'' (1995). 654pp, 64 essays; emphasis on

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture (much of it imported from

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture (much of it imported from

. After Henry II's death in a joust, the country was ruled by his widow Catherine de' Medici and her sons Francis II of France, Francis II, Charles IX of France, Charles IX and Henry III of France, Henry III. Renewed Catholic reaction headed by the powerful Counts and dukes of Guise, dukes of Guise culminated in a St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, massacre of Huguenots (1572), starting the first of the umbrella term

Hypernymy and hyponymy are the wikt:Wiktionary:Semantic relations, semantic relations between a generic term (''hypernym'') and a more specific term (''hyponym''). The hypernym is also called a ''supertype'', ''umbrella term'', or ''blanket term ...

given to various political entities of France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in the medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and early modern

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

to 1848 during its dissolution. It was also an early colonial power

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an imperialist project, colonialism can also take ...

, with colonies in Asia and Africa, and the largest being New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

in North America geographically centred around the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

.

The Kingdom of France was descended directly from the western Frankish realm of the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Franks, Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as List of Frankish kings, kings of the Franks since ...

, which was ceded to Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as CharlesII, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), King of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a series of civil wars during t ...

with the Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (; ), agreed to on 10 August 843, ended the Carolingian civil war and divided the Carolingian Empire between Lothair I, Louis the German, Louis II and Charles the Bald, Charles II, the surviving sons of the emperor Louis the ...

(843). A branch of the Carolingian dynasty continued to rule until 987, when Hugh Capet

Hugh Capet (; ; 941 – 24 October 996) was the King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He is the founder of and first king from the House of Capet. The son of the powerful duke Hugh the Great and his wife Hedwige of Saxony, he was elected as t ...

was elected king and founded the Capetian dynasty. The territory remained known as ''Francia'' and its ruler as ('king of the Franks') well into the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

. The first king calling himself ('King of France') was Philip II, in 1190, and officially from 1204. From then, France was continuously ruled by the Capetians and their cadet lines under the Valois and Bourbon until the monarchy was abolished in 1792 during the French Revolution. The Kingdom of France was also ruled in personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

with the Kingdom of Navarre

The Kingdom of Navarre ( ), originally the Kingdom of Pamplona, occupied lands on both sides of the western Pyrenees, with its northernmost areas originally reaching the Atlantic Ocean (Bay of Biscay), between present-day Spain and France.

The me ...

over two time periods, 1284–1328 and 1572–1620, after which the institutions of Navarre were abolished and it was fully annexed by France (though the King of France continued to use the title "King of Navarre" through the end of the monarchy).

France in the Middle Ages

The Kingdom of France in the Middle Ages (roughly, from the 10th century to the middle of the 15th century) was marked by the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and West Francia (843–987); the expansion of royal control by the House of C ...

was a decentralised, feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

monarchy. In Brittany

Brittany ( ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul. It became an Kingdom of Brittany, independent kingdom and then a Duch ...

and Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationalities and regions of Spain, nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 2006, Statute of Autonomy. Most of its territory (except the Val d'Aran) is situate ...

(the latter now a part of Spain), as well as Aquitaine

Aquitaine (, ; ; ; ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne (), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former Regions of France, administrative region. Since 1 January 2016 it has been part of the administ ...

, the authority of the French king was barely felt. Lorraine

Lorraine, also , ; ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; ; ; is a cultural and historical region in Eastern France, now located in the administrative region of Grand Est. Its name stems from the medieval kingdom of ...

, Provence

Provence is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which stretches from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the France–Italy border, Italian border to the east; it is bordered by the Mediterrane ...

and East Burgundy were states of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

and not yet a part of France. West Frankish kings were initially elected by the secular and ecclesiastical magnates, but the regular coronation of the eldest son of the reigning king during his father's lifetime established the principle of male primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

, which became codified in the Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

. During the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

, rivalry between the Capetian dynasty, rulers of the Kingdom of France and their vassals the House of Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet (Help:IPA/English, /plænˈtædʒənət/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''plan-TAJ-ə-nət'') was a royal house which originated from the Medieval France, French county of Anjou. The name Plantagenet is used by mo ...

, who also ruled the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

as part of their so-called competing Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; ) was the collection of territories held by the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly all of present-day England, half of France, and parts of Ireland and Wal ...

, resulted in many armed struggles. The most notorious of them all are the series of conflicts known as the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

(1337–1453) in which the kings of England

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the heptarchy, seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself king of the ...

laid claim to the French throne. Emerging victorious from said conflicts, France subsequently sought to extend its influence into Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, but after initial gains was defeated by Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

and the Holy Roman Empire in the ensuing Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

(1494–1559).

France in the early modern era was increasingly centralised; the French language began to displace other languages from official use, and the monarch expanded his absolute power in an administrative system, known as the ''Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for " ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

'', complicated by historic and regional irregularities in taxation, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions, and local prerogatives. Religiously, France became divided between the Catholic majority and a Protestant minority, the Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

, which led to a series of civil wars, the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Subsequently, France developed its first colonial empire in Asia, Africa, and in the Americas.

In the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over , the second-largest empire in the world at the time behind the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. French intervention in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

helped the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

secure independence from King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

and the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, but was costly and achieved little for France.

France through its French colonial empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas Colony, colonies, protectorates, and League of Nations mandate, mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "Firs ...

, became a superpower from 1643 until 1815; from the reign of King Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

until the defeat of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

in the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. The Spanish Empire lost its superpower status to France after the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees(; ; ) was signed on 7 November 1659 and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa River on ...

(but maintained the status of Great Power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

until the Napoleonic Wars and the Independence of Spanish America). France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

lost its superpower status after Napoleon's defeat against the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, Prussians and Russians

Russians ( ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Eastern Europe. Their mother tongue is Russian language, Russian, the most spoken Slavic languages, Slavic language. The majority of Russians adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church ...

in 1815

Events

January

* January 2 – Lord Byron marries Anna Isabella Milbanke in Seaham, county of Durham, England.

* January 3 – Austria, Britain, and Bourbon-restored France form a secret defensive alliance treaty against Pr ...

.

Following the French Revolution, which began in 1789, the Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted u ...

. The monarchy was restored by the other great powers in 1814 and, with the exception of the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days ( ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition (), marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII o ...

in 1815, lasted until the French Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (), also known as the February Revolution (), was a period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundation of the French Second Republic. It sparked t ...

.

Political history

West Francia

During the later years ofCharlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

's rule, the Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

made advances along the northern and western perimeters of the Kingdom of the Franks

The Kingdom of the Franks (), also known as the Frankish Kingdom, or just Francia, was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties during the Early Middle Ag ...

. After Charlemagne's death in 814 his heirs were incapable of maintaining political unity and the empire began to crumble. The Treaty of Verdun

The Treaty of Verdun (; ), agreed to on 10 August 843, ended the Carolingian civil war and divided the Carolingian Empire between Lothair I, Louis the German, Louis II and Charles the Bald, Charles II, the surviving sons of the emperor Louis the ...

of 843 divided the Carolingian Empire into three parts, with Charles the Bald

Charles the Bald (; 13 June 823 – 6 October 877), also known as CharlesII, was a 9th-century king of West Francia (843–877), King of Italy (875–877) and emperor of the Carolingian Empire (875–877). After a series of civil wars during t ...

ruling over West Francia

In medieval historiography, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () constitutes the initial stage of the Kingdom of France and extends from the year 843, from the Treaty of Verdun, to 987, the beginning of the Capet ...

, the nucleus of what would develop into the kingdom of France. Charles the Bald was also crowned King of Lotharingia after the death of Lothair II

Lothair II (835 – 8 August 869) was a Carolingian king and ruler of northern parts of Middle Francia, that came to be known as Lotharingia, reigning there from 855 until his death in 869. He also ruled over Burgundy, holding from 855 just th ...

in 869, but in the Treaty of Meerssen

The Treaty of Mersen or Meerssen, concluded on 8 August 870, was a treaty to partition the realm of Lothair II, known as Lotharingia, by his uncles Louis the German of East Francia and Charles the Bald of West Francia, the two surviving sons of ...

(870) was forced to cede much of Lotharingia to his brothers, retaining the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; Occitan language, Occitan: ''Ròse''; Franco-Provençal, Arpitan: ''Rôno'') is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and Southeastern France before dischargi ...

and Meuse

The Meuse or Maas is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a total length of .

History

From 1301, the upper ...

basins (including Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

, Vienne and Besançon

Besançon (, ; , ; archaic ; ) is the capital of the Departments of France, department of Doubs in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. The city is located in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerland.

Capi ...

) but leaving the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

with Aachen

Aachen is the List of cities in North Rhine-Westphalia by population, 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia and the List of cities in Germany by population, 27th-largest city of Germany, with around 261,000 inhabitants.

Aachen is locat ...

, Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

, and Trier

Trier ( , ; ), formerly and traditionally known in English as Trèves ( , ) and Triers (see also Names of Trier in different languages, names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle (river), Moselle in Germany. It lies in a v ...

in East Francia

East Francia (Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the East Franks () was a successor state of Charlemagne's empire created in 843 and ruled by the Carolingian dynasty until 911. It was established through the Treaty of Verdun (843) which divided the for ...

.

Viking incursions up the Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

, the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

, and other inland waterways increased. During the reign of Charles the Simple

Charles III (17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin ''Carolus Simplex''), was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–923. He was a memb ...

(898–922), Vikings under Rollo

Rollo (, ''Rolloun''; ; ; – 933), also known with his epithet, Rollo "the Walker", was a Viking who, as Count of Rouen, became the first ruler of Normandy, a region in today's northern France. He was prominent among the Vikings who Siege o ...

from Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

settled along the Seine, downstream from Paris, in a region that came to be known as Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

.

High Middle Ages

TheCarolingians

The Carolingian dynasty ( ; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charles Martel and his grandson Charlemagne, descendants of the Arnulfing and Pippinid ...

were to share the fate of their predecessors: after an intermittent power struggle between the two dynasties, the accession in 987 of Hugh Capet

Hugh Capet (; ; 941 – 24 October 996) was the King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He is the founder of and first king from the House of Capet. The son of the powerful duke Hugh the Great and his wife Hedwige of Saxony, he was elected as t ...

, Duke of France and Count of Paris, established the Capetian dynasty on the throne. With its offshoots, the houses of Valois and Bourbon, it was to rule France for more than 800 years.

The old order left the new dynasty in immediate control of little beyond the middle Seine and adjacent territories, while powerful territorial lords such as the 10th- and 11th-century counts of Blois

During the Middle Ages, the counts of Blois were among the most powerful vassals of the King of France.

This title of nobility seems to have been created in 832 by Emperor Louis the Pious for William, the youngest son of Adrian, Count of Orléa ...

accumulated large domains of their own through marriage and through private arrangements with lesser nobles for protection and support.

The area around the lower Seine became a source of particular concern when Duke William

William is a masculine given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman Conquest, Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle ...

of Normandy took possession of the Kingdom of England by the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, French people, French, Flemish people, Flemish, and Bretons, Breton troops, all led by the Du ...

of 1066, making himself and his heirs the king's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

inherited the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple, King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a r ...

and the County of Anjou

The County of Anjou (, ; ; ) was a French county that was the predecessor to the Duchy of Anjou. Its capital was Angers, and its area was roughly co-extensive with the diocese of Angers. Anjou was bordered by Brittany to the west, Maine, France, ...

, and married France's newly single ex-queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor of Aquitaine ( or ; ; , or ; – 1 April 1204) was Duchess of Aquitaine from 1137 to 1204, Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, and Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II. As ...

, who ruled much of southwest France, in 1152. After defeating a revolt

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

led by Eleanor and three of their four sons, Henry had Eleanor imprisoned, made the Duke of Brittany

This is a list of rulers of Brittany. In different epochs the rulers of Brittany were kings, princes, and dukes. The Breton ruler was sometimes elected, sometimes attained the position by conquest or intrigue, or by hereditary right. Hereditary ...

his vassal, and in effect ruled the western half of France as a greater power than the French throne. However, disputes among Henry's descendants over the division of his French territories, coupled with John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Empi ...

's lengthy quarrel with Philip II, allowed Philip to recover influence over most of this territory. After the French victory at the Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines took place on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War (1213–14), Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troo ...

in 1214, the English monarchs maintained power only in southwestern Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine (, ; , ) was a historical fiefdom located in the western, central, and southern areas of present-day France, south of the river Loire. The full extent of the duchy, as well as its name, fluctuated greatly over the centuries ...

.

Late Middle Ages and the Hundred Years' War

The death ofCharles IV of France

Charles IV (18/19 June 1294 – 1 February 1328), called the Fair (''le Bel'') in France and the Bald (''el Calvo'') in Navarre, was the last king of the direct line of the House of Capet, List of French monarchs, King of France and List of Nav ...

in 1328 without male heirs ended the main Capetian line. Under Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

the crown could not pass through a woman (Philip IV's daughter was Isabella, whose son was Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

), so the throne passed to Philip VI, son of Charles of Valois

Charles, Count of Valois (12 March 1270 – 16 December 1325), was a member of the House of Capet and founder of the House of Valois, which ruled over France from 1328. He was the fourth son of King Philip III of France and Isabella o ...

. This, in addition to a long-standing dispute over the rights to Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

in the south of France, and the relationship between England and the Flemish cloth towns, led to the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

of 1337–1453. The following century was to see devastating warfare, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War

The Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War was a conflict between two cadet branches of the French royal family: the House of Orléans ( Armagnac faction) and the House of Burgundy ( Burgundian faction) from 1407 to 1435. It began during a lull in t ...

, peasant revolts (the English peasants' revolt of 1381 and the ''Jacquerie

The Jacquerie () was a popular revolt by peasants that took place in northern France in the early summer of 1358 during the Hundred Years' War. The revolt was centred in the valley of the Oise north of Paris and was suppressed after over tw ...

'' of 1358 in France) and the growth of nationalism in both countries.

The losses of the century of war were enormous, particularly owing to the plague (the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

, usually considered an outbreak of bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of Plague (disease), plague caused by the Bacteria, bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and ...

), which arrived from Italy in 1348, spreading rapidly up the Rhône valley and thence across most of the country: it is estimated that a population of some 18–20 million in modern-day France at the time of the 1328 hearth tax

A hearth tax was a property tax in certain countries during the medieval and early modern period, levied on each hearth, thus by proxy on wealth. It was calculated based on the number of hearths, or fireplaces, within a municipal area and is con ...

returns had been reduced 150 years later by 50 percent or more.

Renaissance and Reformation

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture (much of it imported from

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture (much of it imported from Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

). The kings built a strong fiscal system, which heightened the power of the king to raise armies that overawed the local nobility. In Paris especially there emerged strong traditions in literature, art and music. The prevailing style was classical.

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (, ) is an extensive piece of reform legislation signed into law by Francis I of France on August 10, 1539, in the city of Villers-Cotterêts and the oldest French legislation still used partly by French court ...

was signed into law by Francis I in 1539.

Largely the work of Chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

Guillaume Poyet, it dealt with a number of government, judicial and ecclesiastical matters. Articles 110 and 111, the most famous, called for the use of the French language in all legal acts, notarised contracts and official legislation.

Italian Wars

After the Hundred Years' War,Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13. His elder sister Anne acted as regent jointly with her husband Peter II, Du ...

signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509), also known as Henry Tudor, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henr ...

, Emperor Maximilian I, and Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II, also known as Ferdinand I, Ferdinand III, and Ferdinand V (10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), called Ferdinand the Catholic, was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of ...

respectively at Étaples

Étaples or Étaples-sur-Mer (; or ; formerly ; ) is a communes of France, commune in the departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, northern France. It is a fishing and leisure port on the Canche river.

History

Étapl ...

(1492), Senlis

Senlis () is a commune in the northern French department of Oise, Hauts-de-France.

The monarchs of the early French dynasties lived in Senlis, attracted by the proximity of the Chantilly forest. It is known for its Gothic cathedral and other ...

(1493) and Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

(1493). These three treaties cleared the way for France to undertake the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. French efforts to gain dominance resulted only in the increased power of the House of Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful Dynasty, dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout ...

.

Wars of Religion

Barely were the Italian Wars over, when France was plunged into a domestic crisis with far-reaching consequences. Despite the conclusion of aConcordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 ...

between France and the Papacy (1516), granting the crown unrivalled power in senior ecclesiastical appointments, France was deeply affected by the Protestant Reformation's attempt to break the hegemony of Catholic Europe. A growing urban-based Protestant minority (later dubbed ''Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

'') faced ever harsher repression under the rule of Francis I's son King Henry II of France">Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

, during which English, German and Spanish forces intervened on the side of rival Protestant and Catholic forces. Opposed to absolute monarchy, the Huguenot Monarchomachs

The Monarchomachs () were originally French Huguenot theorists who opposed monarchy at the end of the 16th century, known in particular for having theoretically justified tyrannicide. The term was originally a pejorative word coined in 1600 by ...

theorized during this time the right of rebellion and the legitimacy of tyrannicide

Tyrannicide is the killing or assassination of a tyrant or unjust ruler, purportedly for the common good, and usually by one of the tyrant's subjects. Tyrannicide was legally permitted and encouraged in Classical Athens. Often, the term "tyrant ...

.

The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys in which Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic League, and the king was murdered in return. After the assassination of both Henry of Guise (1588) and Henry III (1589), the conflict was ended by the accession of the Protestant king of Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

as Henry IV (first king of the Bourbon dynasty

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Kingdom of Navarre, Navarre in the 16th century. A br ...

) and his subsequent abandonment of Protestantism (Expedient of 1592) effective in 1593, his acceptance by most of the Catholic establishment (1594) and by the Pope (1595), and his issue of the toleration decree known as the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

(1598), which guaranteed freedom of private worship and civil equality.

Early modern period

Colonial France

France's pacification under Henry IV laid much of the ground for the beginnings of France's rise to European hegemony. France was expansive during all but the end of the seventeenth century: the French began trading in India andMadagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, founded Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

and penetrated the North American Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, established plantation economies in the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

and extended their trade contacts in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

and enlarged their merchant marine.

Thirty Years' War

Henry IV's sonLouis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

, elaborated a policy against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

(1618–1648) which had broken out in Germany. After the death of both king and cardinal, the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought peace to the Holy Roman Empire ...

(1648) secured universal acceptance of Germany's political and religious fragmentation, but the Regency of Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (; ; born Ana María Mauricia; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was Queen of France from 1615 to 1643 by marriage to King Louis XIII. She was also Queen of Navarre until the kingdom's annexation into the French crown ...

and her minister Cardinal Mazarin

Jules Mazarin (born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino or Mazarini; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), from 1641 known as Cardinal Mazarin, was an Italian Catholic prelate, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Lou ...

experienced a civil uprising known as the Fronde

The Fronde () was a series of civil wars in the Kingdom of France between 1648 and 1653, occurring in the midst of the Franco-Spanish War, which had begun in 1635. The government of the young King Louis XIV confronted the combined opposition ...

(1648–1653) which expanded into a Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659)

The Franco-Spanish War , May 1635 to November 1659, was fought between Kingdom of France, France and Habsburg Spain, Spain, each supported by various allies at different points. The first phase, beginning in May 1635 and ending with the 1648 Peac ...

. The Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees(; ; ) was signed on 7 November 1659 and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa River on ...

(1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon

Roussillon ( , , ; , ; ) was a historical province of France that largely corresponded to the County of Roussillon and French Cerdagne, part of the County of Cerdagne of the former Principality of Catalonia. It is part of the region of ' ...

after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.

Administrative structures

The ''Ancien Régime'', a French term rendered in English as "Old Rule", or simply "Former Regime", refers primarily to the aristocratic, social and political system of early modern France under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime were the result of years of state-building, legislative acts (like theOrdinance of Villers-Cotterêts

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts (, ) is an extensive piece of reform legislation signed into law by Francis I of France on August 10, 1539, in the city of Villers-Cotterêts and the oldest French legislation still used partly by French court ...

), internal conflicts and civil wars, but they remained a confusing patchwork of local privilege and historic differences until the French Revolution brought about a radical suppression of administrative incoherence.

Louis XIV, the Sun King

For most of the reign of

For most of the reign of Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

(1643–1715), ("The Sun King"), France was the dominant power in Europe, aided by the diplomacy of Cardinal Richelieu's successor as the King's chief minister, (1642–61) Cardinal Jules Mazarin, (1602–1661). Cardinal Mazarin oversaw the creation of a French Royal Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in the world recognised as being a blue- ...

that rivalled England's, expanding it from 25 ships to almost 200. The size of the French Royal Army

The French Royal Army () was the principal land force of the Kingdom of France. It served the Bourbon dynasty from the reign of Louis XIV in the mid-17th century to that of Charles X in the 19th, with an interlude from 1792 to 1814 and another du ...

was also considerably increased. Renewed wars (the War of Devolution

The War of Devolution took place from May 1667 to May 1668. In the course of the war, Kingdom of France, France occupied large parts of the Spanish Netherlands and County of Burgundy, Franche-Comté, both then provinces of the Holy Roman Empire ...

, 1667–1668 and the Franco-Dutch War

The Franco-Dutch War, 1672 to 1678, was primarily fought by Kingdom of France, France and the Dutch Republic, with both sides backed at different times by a variety of allies. Related conflicts include the 1672 to 1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War and ...

, 1672–1678) brought further territorial gains (Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities include Arras (Dutch: ...

and western Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

and the free County of Burgundy

The Free County of Burgundy (; ) was a medieval and early modern feudal polity ruled by a count from 982 to 1678. It became known as Franche-Comté (the ''Free County''), and was located in the modern region of Franche-Comté. It belonged to th ...

, previously left to the Empire in 1482), but at the cost of the increasingly concerted opposition of rival royal powers, and a legacy of an increasingly enormous national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occ ...

. An adherent of the theory of the "Divine Right of Kings", which advocates the divine origin of temporal power and any lack of earthly restraint of monarchical rule, Louis XIV continued his predecessors' work of creating a centralized state

A unitary state is a (sovereign) state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create or abolish administrative divisions (sub-national or sub-state units). Such units exer ...

governed from the capital of Paris. He sought to eliminate the remnants of feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

still persisting in parts of France and, by compelling the noble elite to regularly inhabit his lavish Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

, built on the outskirts of Paris, succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in the earlier "Fronde

The Fronde () was a series of civil wars in the Kingdom of France between 1648 and 1653, occurring in the midst of the Franco-Spanish War, which had begun in 1635. The government of the young King Louis XIV confronted the combined opposition ...

" rebellion during Louis' minority. By these means he consolidated a system of absolute monarchy in France that endured 150 years until the French Revolution. McCabe says critics used fiction to portray the degraded Turkish court, using "the harem, the Sultan court, oriental despotism, luxury, gems and spices, carpets, and silk cushions" as an unfavorable analogy to the corruption of the French royal court.

The king sought to impose total religious uniformity on the country, repealing the Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes () was an edict signed in April 1598 by Henry IV of France, King Henry IV and granted the minority Calvinism, Calvinist Protestants of France, also known as Huguenots, substantial rights in the nation, which was predominantl ...

in 1685. It is estimated that anywhere between 150,000 and 300,000 Protestants fled France during the wave of persecution that followed the repeal, (following "Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

" beginning a hundred and fifty years earlier until the end of the 18th century) costing the country a great many intellectuals, artisans, and other valuable people. Persecution extended to unorthodox Roman Catholics like the Jansenists, a group that denied free will and had already been condemned by the popes. In this, he garnered the friendship of the papacy, which had previously been hostile to France because of its policy of putting all church property in the country under the jurisdiction of the state rather than that of Rome.

In November 1700, King Charles II of Spain

Charles II (6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700) was King of Spain from 1665 to 1700. The last monarch from the House of Habsburg, which had ruled Spain since 1516, he died without an heir, leading to a European Great Power conflict over the succ ...

died, ending the Habsburg line in that country. Louis had long planned for this moment, but these plans were thrown into disarray by the will of King Charles, which left the entire Spanish Empire to Louis's grandson Philip, Duke of Anjou, (1683–1746). Essentially, Spain was to become a perpetual ally and even obedient satellite of France, ruled by a king who would carry out orders from Versailles. Realizing how this would upset the balance of power, the other European rulers were outraged. However, most of the alternatives were equally undesirable. For example, putting another Habsburg on the throne would end up recreating the grand multi-national Empire of Charles V; of the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and the Spanish territories in Italy, which would also grossly upset the power balance. However, the rest of Europe would not stand for his ambitions in Spain, and so the long War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

began (1701–1714), a mere three years after the War of the Grand Alliance

The Nine Years' War was a European great power conflict from 1688 to 1697 between Kingdom of France, France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Grand Alliance. Although largely concentrated in Europe, fighting spread to colonial poss ...

(1688–1697, "War of the League of Augsburg") had just concluded.Daniel Roche, France in the Enlightenment (1998)

Dissent and revolution

The reign (1715–1774) of

The reign (1715–1774) of Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

saw an initial return to peace and prosperity under the regency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

(1715–1723) of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans

Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (Philippe Charles; 2 August 1674 – 2 December 1723), who was known as the Regent, was a French prince, soldier, and statesman who served as Regent of the Kingdom of France from 1715 to 1723. He is referred to i ...

, whose policies were largely continued (1726–1743) by Cardinal Fleury, prime minister in all but name. The exhaustion of Europe after two major wars resulted in a long period of peace, only interrupted by minor conflicts like the War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession (; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a civil war in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth over the succession to Augustus II the Strong, which the other European powers widened in pursuit of ...

from 1733 to 1735. Large-scale warfare resumed with the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict fought between 1740 and 1748, primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italian Peninsula, Italy, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Related conflicts include King Ge ...

(1740–1748). But alliance with the traditional Habsburg enemy (the " Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756) against the rising power of Britain and Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

led to costly failure in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

(1756–63) and the loss of France's North American colonies.

On the whole, the 18th century saw growing discontent with the monarchy and the established order. Louis XV was a highly unpopular king for his sexual excesses, overall weakness, and for losing New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

to the British. The writings of the philosophes

The were the intellectuals of the 18th-century European Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophers; rathe ...

such as Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

were a clear sign of discontent, but the king chose to ignore them. He died of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

in 1774, and the French people shed few tears at his death. While France had not yet experienced the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

that was beginning in Britain, the rising middle class of the cities felt increasingly frustrated with a system and rulers that seemed silly, frivolous, aloof, and antiquated, even if true feudalism no longer existed in France.

Upon Louis XV's death, his grandson Louis XVI

Louis XVI (Louis-Auguste; ; 23 August 1754 – 21 January 1793) was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. The son of Louis, Dauphin of France (1729–1765), Louis, Dauphin of France (son and heir- ...

became king. Initially popular, he too came to be widely detested by the 1780s. He was married to an Austrian archduchess, Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

. French intervention in the American War of Independence was also very expensive.

With the country deeply in debt, Louis XVI permitted the radical reforms of Turgot and Malesherbes, but noble disaffection led to Turgot's dismissal and Malesherbes' resignation in 1776. They were replaced by Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker (; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan banker and statesman who served as List of Finance Ministers of France, finance minister for Louis XVI of France, Louis XVI. He was a reformer, but his innov ...

. Necker had resigned in 1781 to be replaced by Calonne and Brienne, before being restored in 1788. A harsh winter that year led to widespread food shortages, and by then France was a powder keg ready to explode. On the eve of the French Revolution of July 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.

Limited monarchy

On September 3, 1791, the absolute monarchy which had governed France for 948 years was forced to limit its power and become a provisional constitutional monarchy. However, this too would not last very long and on September 21, 1792, the French monarchy was effectively abolished by the proclamation of theFrench First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (), was founded on 21 September 1792 during the French Revolution. The First Republic lasted un ...

. The role of the King in France was finally ended with the execution of Louis XVI

Louis XVI, former Bourbon King of France since the Proclamation of the abolition of the monarchy, abolition of the monarchy, was publicly executed on 21 January 1793 during the French Revolution at the ''Place de la Révolution'' in Paris. At Tr ...

by guillotine

A guillotine ( ) is an apparatus designed for effectively carrying out executions by Decapitation, beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secur ...

on Monday, January 21, 1793, followed by the "Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

", mass executions and the provisional " Directory" form of republican government, and the eventual beginnings of twenty-five years of reform, upheaval, dictatorship, wars and renewal, with the various Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

.

Restoration

Following the French Revolution (1789–99) and theFirst French Empire

The First French Empire or French Empire (; ), also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. It lasted from ...

under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

(1804–1814), the monarchy was restored when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the House of Bourbon in 1814. However the deposed Emperor Napoleon I returned triumphantly to Paris from his exile in Elba

Elba (, ; ) is a Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National Park, a ...

and ruled France for a short period known as the Hundred Days

The Hundred Days ( ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition (), marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII o ...

.

When a Seventh European Coalition again deposed Napoleon after the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium), marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The French Imperial Army (1804–1815), Frenc ...

in 1815, the Bourbon monarchy was once again restored.

The Count of Provence - brother of Louis XVI, who was guillotined in 1793 - was crowned as Louis XVIII

Louis XVIII (Louis Stanislas Xavier; 17 November 1755 – 16 September 1824), known as the Desired (), was King of France from 1814 to 1824, except for a brief interruption during the Hundred Days in 1815. Before his reign, he spent 23 y ...

, nicknamed "The Desired". Louis XVIII tried to conciliate the legacies of the Revolution and the Ancien Régime, by permitting the formation of a Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and a constitutional Charter, usually known as the "''Charte octroyée''" ("Granted Charter"). His reign was characterized by disagreements between the Doctrinaires

During the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830) and the July Monarchy (1830–1848), the Doctrinals () were a group of Monarchism in France, French royalists who hoped to reconcile the monarchy with the French Revoluti ...

, liberal thinkers who supported the Charter and the rising bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

, and the Ultra-royalist

The Ultra-royalists (, collectively Ultras) were a Politics of France, French political faction from 1815 to 1830 under the Bourbon Restoration in France, Bourbon Restoration. An Ultra was usually a member of the nobility of high society who str ...

s, aristocrats and clergymen who totally refused the Revolution's heritage. Peace was maintained by statesmen like Talleyrand and the Duke of Richelieu, as well as the King's moderation and prudent intervention. In 1823, the Trienio Liberal

The , () or Three Liberal Years, was a period of three years in Spain between 1820 and 1823 when a liberal government ruled Spain after a military uprising in January 1820 by the lieutenant-colonel Rafael del Riego against the absolutist rule ...

revolt in Spain led to a French intervention on the royalists' side, which permitted King Ferdinand VII of Spain

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was Monarchy of Spain, King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (t ...

to abolish the Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz () and nicknamed ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest codified constitutions in world history. The Constitution w ...

.

However, the work of Louis XVIII was frustrated when, after his death on 16 September 1824, his brother the Count of Artois became king under the name of Charles X Charles X may refer to:

* Charles X of France (1757–1836)

* Charles X Gustav (1622–1660), King of Sweden

* Charles, Cardinal de Bourbon (1523–1590), recognized as Charles X of France but renounced the royal title

See also

*

* King Charle ...

. Charles X was a strong reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

who supported the ultra-royalists and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Under his reign, the censorship of newspapers was reinforced, the Anti-Sacrilege Act passed, and compensations to Émigrés were increased. However, the reign also witnessed the French intervention in the Greek Revolution in favour of the Greek rebels, and the first phase of the conquest of Algeria.

The absolutist tendencies of the King were disliked by the Doctrinaire majority in the Chamber of Deputies

The chamber of deputies is the lower house in many bicameral legislatures and the sole house in some unicameral legislatures.

Description

Historically, French Chamber of Deputies was the lower house of the French Parliament during the Bourb ...

, that on 18 March 1830 sent an address to the King, upholding the rights of the Chamber and in effect supporting a transition to a full parliamentary system. Charles X received this address as a veiled threat, and in 25 July of the same year, he issued the St. Cloud Ordinances, in an attempt to reduce Parliament's powers and re-establish absolute rule. The opposition reacted with riots in Parliament and barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denotes ...

s in Paris, that resulted in the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Cha ...

. The King abdicated, as did his son the Dauphin Louis Antoine, in favour of his grandson Henri, Count of Chambord

Henri, Count of Chambord and Duke of Bordeaux (; 29 September 1820 – 24 August 1883), was the Legitimist pretender to the throne of France as Henri V from 1844 until his death in 1883.

Henri was the only son of Charles Ferdinand, Duke ...

, nominating his cousin the Duke of Orléans

Duke of Orléans () was a French royal title usually granted by the King of France to one of his close relatives (usually a younger brother or son), or otherwise inherited through the male line. First created in 1344 by King Philip VI for his yo ...

as regent. However, it was too late, and the liberal opposition won out over the monarchy.

Aftermath and July Monarchy

On 9 August 1830, the Chamber of Deputies elected Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans as "King of the French": for the first time since French Revolution, the King was designated as the ruler of the French people and not the country. The Bourbonwhite flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire and for negotiation. It is also used to symboliz ...

was substituted with the French tricolour, and a new charter was introduced in August 1830.

The conquest of Algeria continued, and new settlements were established in the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea (French language, French: ''Golfe de Guinée''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Golfo de Guinea''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Golfo da Guiné'') is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez i ...

, Gabon