Iceland Men's National Under-17 Basketball Team on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Iceland is a

The ''Landnámabók'' names Naddodd () as the first

The ''Landnámabók'' names Naddodd () as the first

"Is Iceland Really Green and Greenland Really Icy?"

''

According to both and , monks known as the

According to both and , monks known as the

Around the middle of the 16th century, as part of the

Around the middle of the 16th century, as part of the

On 31 December 1943, the

On 31 December 1943, the

Iceland is at the juncture of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. The main island is entirely south of the

Iceland is at the juncture of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. The main island is entirely south of the  Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island, and Europe's second-largest island after Great Britain and before Ireland. The main island covers , but the entire country is in size, of which 62.7% is

Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island, and Europe's second-largest island after Great Britain and before Ireland. The main island covers , but the entire country is in size, of which 62.7% is

A geologically young land at 16 to 18 million years old, Iceland is the surface expression of the Iceland Plateau, a

A geologically young land at 16 to 18 million years old, Iceland is the surface expression of the Iceland Plateau, a

The only native land mammal when humans arrived was the

The only native land mammal when humans arrived was the

Iceland is a

Iceland is a

Iceland adm location map.svg,

Iceland, which is a member of the UN,

Iceland, which is a member of the UN,

. Oecdbetterlifeindex.org. Retrieved 28 April 2012. 1.7 million people visited Iceland in 2016, 3 times more than the number that came in 2010. Iceland's agriculture industry, accounting for 5.4% of GDP, consists mainly of

Iceland was hit especially hard by the

Iceland was hit especially hard by the

The original population of Iceland was of Norse and

The original population of Iceland was of Norse and

Iceland has a

Iceland has a

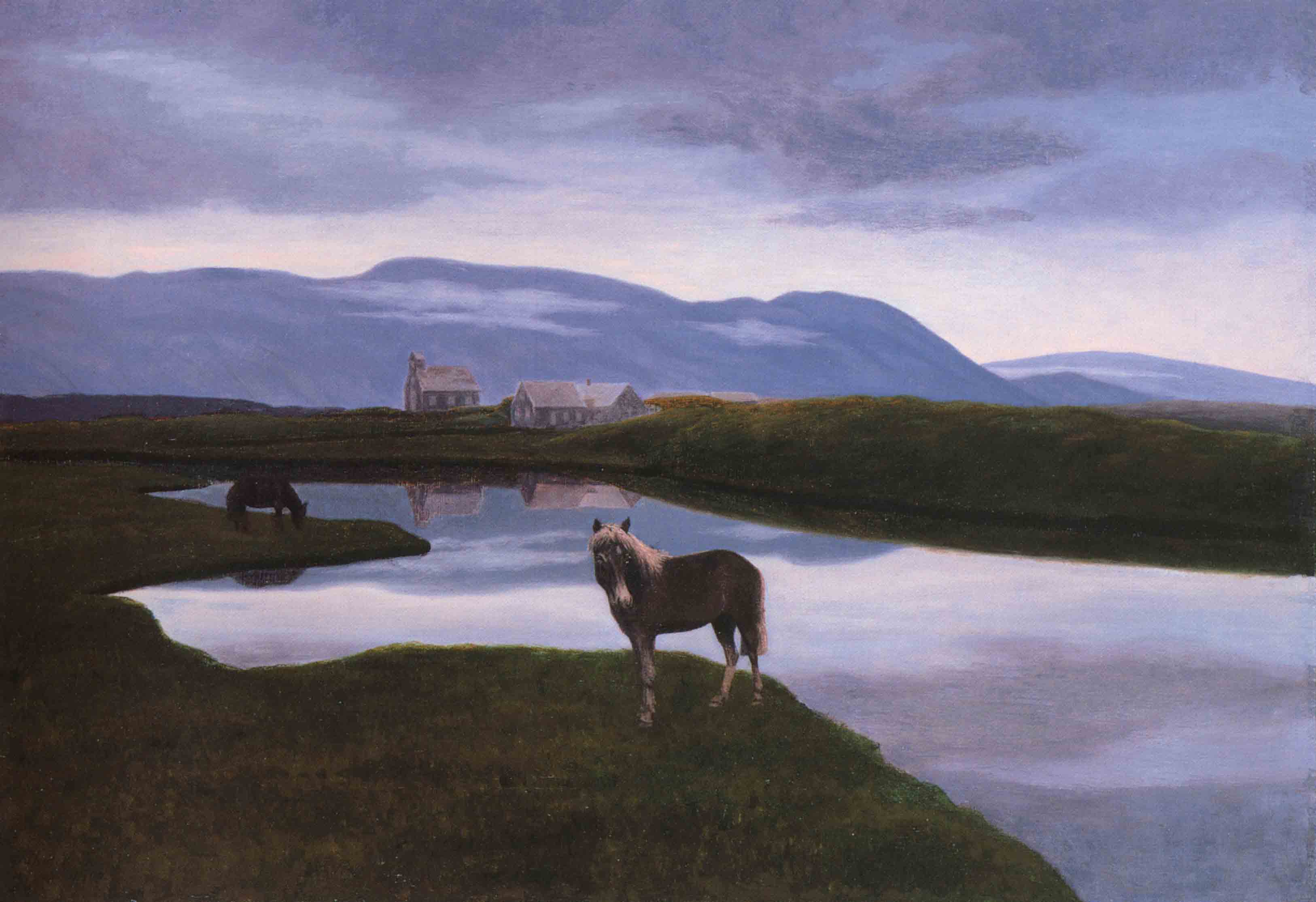

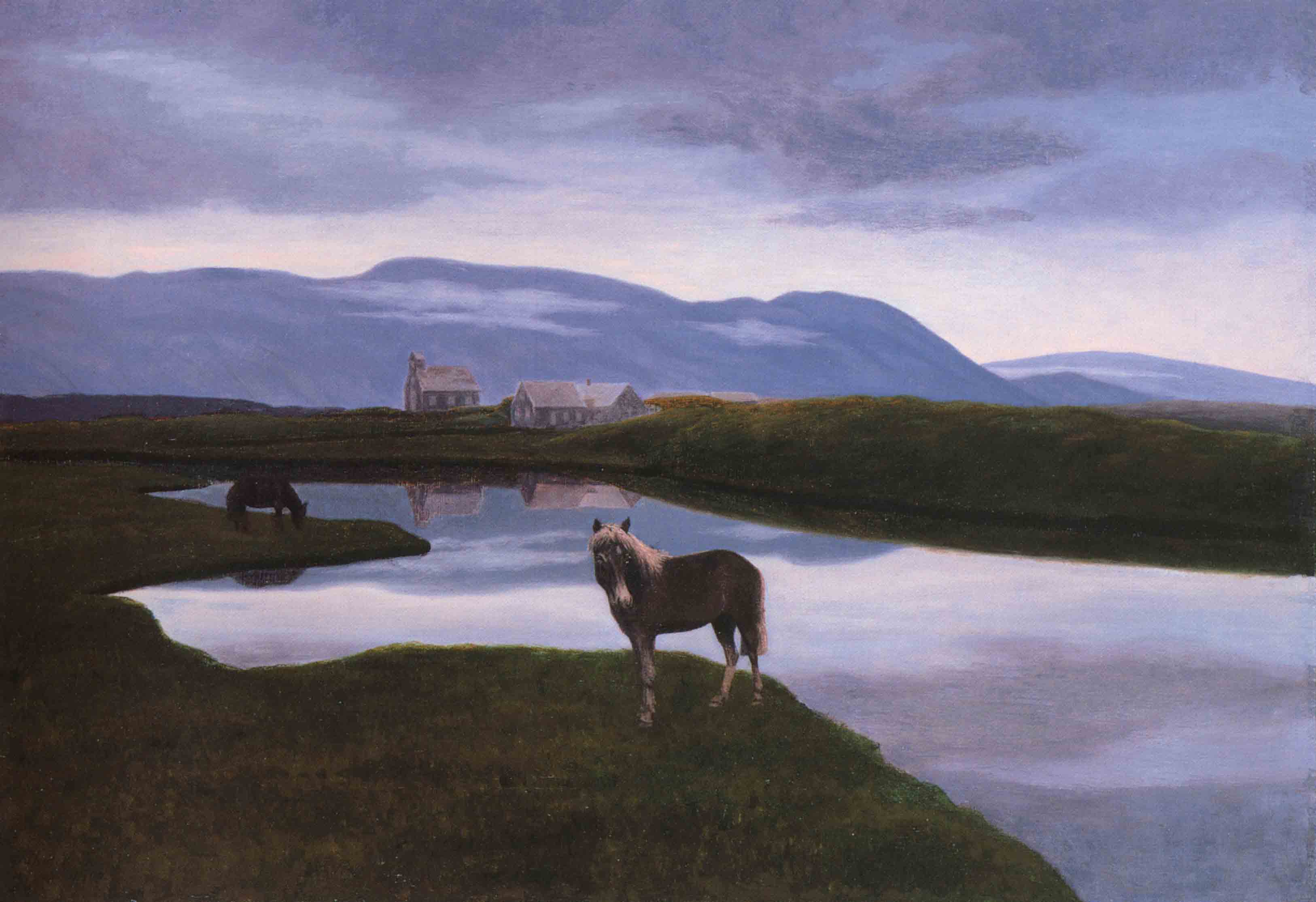

Contemporary Icelandic painting is typically traced to the work of Þórarinn Þorláksson, who, following formal training in art in the 1890s in Copenhagen, returned to Iceland to paint and exhibit works from 1900 to his death in 1924, almost exclusively portraying the Icelandic landscape. Several other Icelandic men and women artists studied at Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts at that time, including Ásgrímur Jónsson, who together with Þórarinn created a distinctive portrayal of Iceland's landscape in a romantic naturalistic style. Other landscape artists quickly followed in the footsteps of Þórarinn and Ásgrímur. These included Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval, Jóhannes Kjarval and Júlíana Sveinsdóttir. Kjarval in particular is noted for the distinct techniques in the application of paint that he developed in a concerted effort to render the characteristic volcanic rock that dominates the Icelandic environment. Einar Hákonarson is an expressionistic and figurative painter who by some is considered to have brought the figure back into Icelandic painting. In the 1980s, many Icelandic artists worked with the subject of the new painting in their work.

In recent years the artistic practice has multiplied, and the Icelandic art scene has become a setting for many large-scale projects and exhibitions. The artist-run gallery space Kling og Bang, members of which later ran the studio complex and exhibition venue Klink og Bank, has been a significant part of the trend of self-organised spaces, exhibitions, and projects. The Living Art Museum, Reykjavík Municipal Art Museum, Reykjavík Art Museum, and the National Gallery of Iceland are the larger, more established institutions, curating shows and festivals.

Contemporary Icelandic painting is typically traced to the work of Þórarinn Þorláksson, who, following formal training in art in the 1890s in Copenhagen, returned to Iceland to paint and exhibit works from 1900 to his death in 1924, almost exclusively portraying the Icelandic landscape. Several other Icelandic men and women artists studied at Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts at that time, including Ásgrímur Jónsson, who together with Þórarinn created a distinctive portrayal of Iceland's landscape in a romantic naturalistic style. Other landscape artists quickly followed in the footsteps of Þórarinn and Ásgrímur. These included Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval, Jóhannes Kjarval and Júlíana Sveinsdóttir. Kjarval in particular is noted for the distinct techniques in the application of paint that he developed in a concerted effort to render the characteristic volcanic rock that dominates the Icelandic environment. Einar Hákonarson is an expressionistic and figurative painter who by some is considered to have brought the figure back into Icelandic painting. In the 1980s, many Icelandic artists worked with the subject of the new painting in their work.

In recent years the artistic practice has multiplied, and the Icelandic art scene has become a setting for many large-scale projects and exhibitions. The artist-run gallery space Kling og Bang, members of which later ran the studio complex and exhibition venue Klink og Bank, has been a significant part of the trend of self-organised spaces, exhibitions, and projects. The Living Art Museum, Reykjavík Municipal Art Museum, Reykjavík Art Museum, and the National Gallery of Iceland are the larger, more established institutions, curating shows and festivals.

Iceland's largest television stations are the state-run Sjónvarpið and the privately owned Stöð 2 and SkjárEinn. Smaller stations exist, many of them local. Radio is broadcast throughout the country, including in some parts of the interior. The main radio stations are Rás 1, Rás 2, X-ið 977, Bylgjan and FM 957 (Icelandic Radio Station), FM957. The daily newspapers are ''Morgunblaðið'' and ''Fréttablaðið''. The most popular websites are the news sites Vísir and Mbl.is.

Iceland is home to ''LazyTown'' (Icelandic: ''Latibær''), a children's educational musical comedy programme created by Magnús Scheving. It has become a very popular programme for children and adults and is shown in over 100 countries, including the Americas, the UK and Sweden. The ''LazyTown'' studios are located in

Iceland's largest television stations are the state-run Sjónvarpið and the privately owned Stöð 2 and SkjárEinn. Smaller stations exist, many of them local. Radio is broadcast throughout the country, including in some parts of the interior. The main radio stations are Rás 1, Rás 2, X-ið 977, Bylgjan and FM 957 (Icelandic Radio Station), FM957. The daily newspapers are ''Morgunblaðið'' and ''Fréttablaðið''. The most popular websites are the news sites Vísir and Mbl.is.

Iceland is home to ''LazyTown'' (Icelandic: ''Latibær''), a children's educational musical comedy programme created by Magnús Scheving. It has become a very popular programme for children and adults and is shown in over 100 countries, including the Americas, the UK and Sweden. The ''LazyTown'' studios are located in

Much of Iceland's cuisine is based on fish, lamb and mutton, lamb, and dairy products, with little to no use of herbs or spices. Due to the island's climate, fruits and vegetables are not generally a component of traditional dishes, although the use of greenhouses has made them more common in contemporary food. Þorramatur is a selection of traditional cuisine consisting of many dishes and is usually consumed around the month of Month#Germanic calendar, Þorri, which begins on the first Friday after 19 January. Traditional dishes also include skyr (a yogurt-like cheese), hákarl (cured shark), cured ram, singed sheep heads, and black pudding, Flatkaka (flatbread), dried fish and dark rye bread traditionally baked in the ground in geothermal areas. Puffin is considered a local delicacy that is often prepared through broiling.

Breakfast usually consists of pancakes, cereal, fruit, and coffee, while lunch may take the form of a smörgåsbord. The main meal of the day for most Icelanders is dinner, which usually involves fish or lamb as the main course. Seafood is central to most Icelandic cooking, particularly cod and haddock but also salmon, herring, and halibut. It is often prepared in a wide variety of ways, either smoked, pickled, boiled, or dried. Lamb is by far the most common meat, and it tends to be either smoke-cured (known as ''hangikjöt'') or salt-preserved (''saltkjöt''). Many older dishes make use of every part of the sheep, such as ''slátur'', which consists of offal (internal organs and entrails) minced together with blood and served in sheep stomach. Additionally, boiled or mashed potatoes, pickled cabbage, green beans, and rye bread are prevalent side dishes.

Coffee is a popular beverage in Iceland, with the country being third placed by per capita consumption worldwide in 2016, and is drunk at breakfast, after meals, and with a light snack in mid-afternoon. Coca-Cola is also widely consumed, to the extent that the country is said to have one of the highest per capita consumption rates in the world.

Iceland's signature alcoholic beverage is ''brennivín'' (literally "burnt [i.e., distilled] wine"), which is similar in flavouring to the akvavit variant of Scandinavian brännvin. It is a type of schnapps made from distilled potatoes and flavoured with either caraway seeds or angelica. Its potency has earned it the nickname ''svarti dauði'' ("Black Death"). Modern distilleries on Iceland produce vodka (Reyka), gin (Ísafold), moss schnapps (Fjallagrasa), and a birch-flavoured schnapps and liqueur (Foss Distillery's Birkir and Björk). Martin Miller blends Icelandic water with its England-distilled gin on the island. Strong beer was Prohibition in Iceland, banned until 1989, so ''bjórlíki'', a mixture of legal, low-alcohol pilsner beer and vodka, became popular. Several strong beers are now made by Icelandic breweries.

Much of Iceland's cuisine is based on fish, lamb and mutton, lamb, and dairy products, with little to no use of herbs or spices. Due to the island's climate, fruits and vegetables are not generally a component of traditional dishes, although the use of greenhouses has made them more common in contemporary food. Þorramatur is a selection of traditional cuisine consisting of many dishes and is usually consumed around the month of Month#Germanic calendar, Þorri, which begins on the first Friday after 19 January. Traditional dishes also include skyr (a yogurt-like cheese), hákarl (cured shark), cured ram, singed sheep heads, and black pudding, Flatkaka (flatbread), dried fish and dark rye bread traditionally baked in the ground in geothermal areas. Puffin is considered a local delicacy that is often prepared through broiling.

Breakfast usually consists of pancakes, cereal, fruit, and coffee, while lunch may take the form of a smörgåsbord. The main meal of the day for most Icelanders is dinner, which usually involves fish or lamb as the main course. Seafood is central to most Icelandic cooking, particularly cod and haddock but also salmon, herring, and halibut. It is often prepared in a wide variety of ways, either smoked, pickled, boiled, or dried. Lamb is by far the most common meat, and it tends to be either smoke-cured (known as ''hangikjöt'') or salt-preserved (''saltkjöt''). Many older dishes make use of every part of the sheep, such as ''slátur'', which consists of offal (internal organs and entrails) minced together with blood and served in sheep stomach. Additionally, boiled or mashed potatoes, pickled cabbage, green beans, and rye bread are prevalent side dishes.

Coffee is a popular beverage in Iceland, with the country being third placed by per capita consumption worldwide in 2016, and is drunk at breakfast, after meals, and with a light snack in mid-afternoon. Coca-Cola is also widely consumed, to the extent that the country is said to have one of the highest per capita consumption rates in the world.

Iceland's signature alcoholic beverage is ''brennivín'' (literally "burnt [i.e., distilled] wine"), which is similar in flavouring to the akvavit variant of Scandinavian brännvin. It is a type of schnapps made from distilled potatoes and flavoured with either caraway seeds or angelica. Its potency has earned it the nickname ''svarti dauði'' ("Black Death"). Modern distilleries on Iceland produce vodka (Reyka), gin (Ísafold), moss schnapps (Fjallagrasa), and a birch-flavoured schnapps and liqueur (Foss Distillery's Birkir and Björk). Martin Miller blends Icelandic water with its England-distilled gin on the island. Strong beer was Prohibition in Iceland, banned until 1989, so ''bjórlíki'', a mixture of legal, low-alcohol pilsner beer and vodka, became popular. Several strong beers are now made by Icelandic breweries.

Government Offices of Iceland

Icelandic Government Information Center & Icelandic Embassies

Visit Iceland

– the official Icelandic Tourist Board

Iceland

. ''The World Factbook''. Central Intelligence Agency.

Iceland

entry at ''Encyclopædia Britannica''

Iceland

from BBC News * *

Incredible Iceland: Fire and Ice

nbsp;– slideshow by Life (magazine), ''Life'' magazine

''A Photographer's View of Iceland''

Documentary produced by Prairie Public Television

Arason Steingrimur Writings on Iceland

at Dartmouth College Library {{Coord, 65, N, 18, W, scale:5000000_source:GNS, display = title Iceland, Countries in Europe Former Norwegian colonies Island countries Islands of Iceland Members of the Nordic Council Member states of the European Free Trade Association Member states of NATO Member states of the Council of Europe Member states of the United Nations Nordic countries, - Republics States and territories established in 1944 Christian states Mid-Atlantic Ridge OECD members

Nordic

Nordic most commonly refers to:

* Nordic countries, the northern European countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and their North Atlantic territories

* Scandinavia, a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern ...

island country

An island country, island state, or island nation is a country whose primary territory consists of one or more islands or parts of islands. Approximately 25% of all independent countries are island countries. Island countries are historically ...

between the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

and Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five oceanic divisions. It spans an area of approximately and is the coldest of the world's oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, ...

s, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a Divergent boundary, divergent or constructive Plate tectonics, plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest mountai ...

between North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the region's westernmost and most sparsely populated country. Its capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

and largest city is Reykjavík

Reykjavík is the Capital city, capital and largest city in Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland on the southern shore of Faxaflói, the Faxaflói Bay. With a latitude of 64°08′ N, the city is List of northernmost items, the worl ...

, which is home to about 36% of the country's roughly 380,000 residents (excluding nearby towns/suburbs, which are separate municipalities). The official language of the country is Icelandic.

Iceland is on a rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics. Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben ...

between tectonic plates

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

, and its geologic activity includes geyser

A geyser (, ) is a spring with an intermittent water discharge ejected turbulently and accompanied by steam. The formation of geysers is fairly rare and is caused by particular hydrogeological conditions that exist only in a few places on Ea ...

s and frequent volcanic eruptions

A volcanic eruption occurs when material is expelled from a volcanic vent or fissure. Several types of volcanic eruptions have been distinguished by volcanologists. These are often named after famous volcanoes where that type of behavior h ...

. The interior consists of a volcanic plateau

A volcanic plateau is a plateau produced by volcanic activity. There are two main types: lava plateaus and pyroclastic plateaus.

Lava plateau

Lava plateaus are formed by highly fluid basaltic lava during numerous successive eruptions thro ...

with sand and lava field

A lava field, sometimes called a lava bed, is a large, mostly flat area of lava flows. Such features are generally composed of highly fluid basalt lava, and can extend for tens or hundreds of kilometers across the underlying terrain.

Morp ...

s, mountains and glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s, and many glacial rivers flow to the sea through the lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of a ...

. Iceland is warmed by the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

and has a temperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (approximately 23.5° to 66.5° N/S of the Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ra ...

, despite being a latitude just south of the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

. Its latitude and marine influence keep summers chilly, and most of its islands

This is a list of the lists of islands in the world grouped by country, by continent, by body of water, and by other classifications. For rank-order lists, see the #Other lists of islands, other lists of islands below.

Lists of islands by count ...

have a polar climate

The polar climate regions are characterized by a lack of warm summers but with varying winters. Every month a polar climate has an average temperature of less than . Regions with a polar climate cover more than 20% of the Earth's area. Most of ...

.

According to the ancient manuscript , the settlement of Iceland

The settlement of Iceland ( ) is generally believed to have begun in the second half of the ninth century, when Norsemen, Norse settlers migrated across the North Atlantic. The reasons for the migration are uncertain: later in the Middle Ages Icel ...

began in 874 AD, when the Norwegian chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson

Ingolfr Arnarson, in some sources named Bjǫrnolfsson, ( – )

is commonly recognized as the first permanent Norse settler of Iceland, together with his wife Hallveig Fróðadóttir and foster brother Hjǫrleifr Hróðmarsson. According to t ...

became the island's first permanent settler. In the following centuries, Norwegians

Norwegians () are an ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians are descended from the Norsemen, Norse of the Early ...

, and to a lesser extent other Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

ns, immigrated to Iceland, bringing with them thrall

A thrall was a slave or Serfdom, serf in Scandinavia, Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The status of slave (, ) contrasts with that of the Franklin (class), freeman (, ) and the nobleman (, ).

Etymology

Thrall is from the Old Norse ...

s (i.e., slaves or serfs) of Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

origin. The island was governed as an independent commonwealth under the native parliament, the Althing

The (; ), anglicised as Althingi or Althing, is the Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme Parliament, national parliament of Iceland. It is the oldest surviving parliament in the world. The Althing was founded in 930 at ('Thing (assembly), thing ...

, one of the world's oldest functioning legislative assemblies. After a period of civil strife, Iceland acceded to Norwegian rule in the 13th century. In 1397, Iceland followed Norway's integration into the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden as designed by Queen Margaret I of Denmark, Margaret of Denmark. From 1397 to 1523, it joined under a single monarch the three kingdoms of Denmark, Sweden (then in ...

along with the kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden, coming under ''de facto'' Danish rule upon its dissolution in 1523. The Danish kingdom introduced Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

by force in 1550, and the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel () or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 ...

formally ceded Iceland to Denmark in 1814.

Influenced by ideals of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

after the French Revolution, Iceland's struggle for independence took form and culminated in the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union

The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, an agreement signed by Iceland and Denmark on 1 December 1918, recognized Iceland as a fully independent and sovereign state, known as the Kingdom of Iceland, which was freely associated to Denmark in a pers ...

in 1918, with the establishment of the Kingdom of Iceland

The Kingdom of Iceland (; ) was a sovereign and independent country under a constitutional and hereditary monarchy that was established by the Act of Union with Denmark signed on 1 December 1918. It lasted until 17 June 1944 when a national ...

, sharing through a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

the incumbent monarch of Denmark

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority a ...

. During the occupation of Denmark

At the outset of World War II in September 1939, Denmark declared itself Neutral countries in World War II, neutral, but that neutrality did not prevent Nazi Germany from Military occupation, occupying the country soon after the outbreak of ...

in World War II, Iceland voted overwhelmingly to become a republic in 1944, ending the remaining formal ties to Denmark. Although the Althing was suspended from 1799 to 1845, Iceland nevertheless has a claim to sustaining one of the world's longest-running parliaments. Until the 20th century, Iceland relied largely on subsistence fishing

Artisanal, subsistence, or traditional fishing consists of various small-scale, low-technology, fishing practices undertaken by individual fishermen (as opposed to commercial fishing). Many of these households are of coastal or island ethnic grou ...

and agriculture. Industrialization of the fisheries and Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

aid after World War II brought prosperity, and Iceland became one of the world's wealthiest and most developed nations. In 1950, Iceland joined the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; , CdE) is an international organisation with the goal of upholding human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. Founded in 1949, it is Europe's oldest intergovernmental organisation, represe ...

. In 1994 it became a part of the European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade Asso ...

, further diversifying its economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

into sectors such as finance, biotechnology, and manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of the

secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer ...

.

Iceland has a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

with relatively low taxes

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

, compared to other OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; , OCDE) is an international organization, intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate economic progress and international trade, wor ...

countries, as well as the highest trade union membership in the world. It maintains a Nordic social welfare system that provides universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized a ...

and tertiary education

Tertiary education (higher education, or post-secondary education) is the educational level following the completion of secondary education.

The World Bank defines tertiary education as including universities, colleges, and vocational schools ...

. Iceland ranks highly in international comparisons of national performance, such as quality of life, education, protection of civil liberties, government transparency, and economic freedom. It has the smallest population of any NATO member and is the only one with no standing army, possessing only a lightly armed coast guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a Maritime Security Regimes, maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with cust ...

.

Etymology

The ''Landnámabók'' names Naddodd () as the first

The ''Landnámabók'' names Naddodd () as the first Norseman

The Norsemen (or Northmen) were a cultural group in the Early Middle Ages, originating among speakers of Old Norse in Scandinavia. During the late eighth century, Scandinavians embarked on a large-scale expansion in all directions, giving ris ...

to reach Iceland in the ninth century, having gotten lost while sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

. He gave the island its first name of ''Snæland'' (); the second one to arrive was the Swedish Garðar Svavarsson

Garðarr Svavarsson (Old Norse: ; Modern Icelandic: ; Modern Swedish: ) was a Swede who briefly resided in Iceland, according to the Sagas. He is said to be the second Scandinavian to reach the island of Iceland after Naddodd. He and his family ...

, who circumnavigated the island and named it ''Garðarshólmur'' () after himself.

The island's present name came from Flóki Vilgerðarson, who was the first Norseman to intentionally travel to Iceland. According to the Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders (, ), also known as family sagas, are a subgenre, or text group, of Icelandic Saga, sagas. They are prose narratives primarily based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and earl ...

, Flóki coined the name after he climbed a mountain, despondent after a harsh winter in present-day Vatnsfjörður

Vatnsfjörður () is a nature reserve located north-west of Breiðafjörður on the Hjarðarnes coast of northwestern Iceland.

External links and sourcesThe Environment Agency of Iceland ''(Umhverfisstofnun)'': Vatnsfjörður

National p ...

, and saw an National p ...

ice cap

In glaciology, an ice cap is a mass of ice that covers less than of land area (usually covering a highland area). Larger ice masses covering more than are termed ice sheets.

Description

By definition, ice caps are not constrained by topogra ...

.Evans, Andrew"Is Iceland Really Green and Greenland Really Icy?"

''

National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly ''The National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as ''Nat Geo'') is an American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. The magazine was founded in 1888 as a scholarly journal, nine ...

'' (30 June 2016). The notion that Iceland's settlers chose that name to discourage competing settlement is most likely a myth.

History

874–1262: settlement and Commonwealth

According to both and , monks known as the

According to both and , monks known as the Papar

The ''Papar'' (; from Latin , via Old Irish, meaning "father" or "pope") were Irish monks who took eremitic residence in parts of Iceland before that island's habitation by the Norsemen of Scandinavia. Their existence is attested by the early ...

lived in Iceland before Scandinavian settlers arrived, possibly members of a Hiberno-Scottish mission

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaels, Gaelic Missionary, missionaries originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales, History of Anglo-Saxon England, England a ...

. An archaeological excavation has revealed the ruins of a cabin in Hafnir

Hafnir () is a town in southwestern Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and p ...

on the Reykjanes peninsula

Southern Peninsula (, ) is an administrative unit and part of Reykjanesskagi (pronounced ), or Reykjanes Peninsula, a region in southwest Iceland. It was named after Reykjanes, the southwestern tip of Reykjanesskagi.

The region has a populatio ...

. Carbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was ...

indicates that it was abandoned sometime between 770 and 880. In 2016, archaeologists uncovered a longhouse

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from lumber, timber and ...

in Stöðvarfjörður

Stöðvarfjörður (; formerly Kirkjuból ) is a village in east Iceland. It sits on the Northern shore of the fjord of the same name, is part of the municipality of Fjarðabyggð and has less than 200 inhabitants.

History

Stöðvarfjörður is r ...

that may date to as early as 800.

Swedish Viking explorer Garðar Svavarsson

Garðarr Svavarsson (Old Norse: ; Modern Icelandic: ; Modern Swedish: ) was a Swede who briefly resided in Iceland, according to the Sagas. He is said to be the second Scandinavian to reach the island of Iceland after Naddodd. He and his family ...

was the first to circumnavigate Iceland in 870 and establish that it was an island. He stayed during the winter and built a house in Húsavík

Húsavík () is a town in Norðurþing municipality on the northeast coast of Iceland on the shores of Skjálfandi bay with 2,485 inhabitants. The most famous landmark of the town is the wooden church Húsavíkurkirkja, built in 1907. Húsav� ...

. Garðar departed the following summer, but one of his men, Náttfari Náttfari (Old Norse: ; Modern Icelandic: ; fl. 835–870) was a crew member who escaped his master, Garðar Svavarsson, and may have become the first permanent resident of Iceland in the 9th century. The earliest account of his story is found in ...

, decided to stay behind with two slaves. Náttfari settled in what is now known as Náttfaravík, and he and his slaves became the first permanent residents of Iceland to be documented.

The Norwegian-Norse chieftain Ingólfr Arnarson

Ingolfr Arnarson, in some sources named Bjǫrnolfsson, ( – )

is commonly recognized as the first permanent Norse settler of Iceland, together with his wife Hallveig Fróðadóttir and foster brother Hjǫrleifr Hróðmarsson. According to t ...

built his homestead in present-day Reykjavík

Reykjavík is the Capital city, capital and largest city in Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland on the southern shore of Faxaflói, the Faxaflói Bay. With a latitude of 64°08′ N, the city is List of northernmost items, the worl ...

in 874. Ingólfr was followed by many other emigrant settlers, largely Scandinavians and their thrall

A thrall was a slave or Serfdom, serf in Scandinavia, Scandinavian lands during the Viking Age. The status of slave (, ) contrasts with that of the Franklin (class), freeman (, ) and the nobleman (, ).

Etymology

Thrall is from the Old Norse ...

s, many of whom were Irish or Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

. By 930, most arable land

Arable land (from the , "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the purposes of a ...

on the island had been claimed; the Althing

The (; ), anglicised as Althingi or Althing, is the Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme Parliament, national parliament of Iceland. It is the oldest surviving parliament in the world. The Althing was founded in 930 at ('Thing (assembly), thing ...

, a legislative and judicial assembly was initiated to regulate the Icelandic Commonwealth

The Icelandic Commonwealth, also known as the Icelandic Free State, was the political unit existing in Iceland between the establishment of the Althing () in 930 and the pledge of fealty to the Norwegian king with the Old Covenant in 1262. W ...

. The lack of arable land also served as an impetus to the settlement of Greenland starting in 986. The period of these early settlements coincided with the Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from about to about . Climate proxy records show peak warmth occu ...

, when temperatures were similar to those of the early 20th century. At this time about 25% of Iceland was covered with forest, compared to 1% in the present day. Christianity was adopted by consensus around 999–1000, although Norse paganism

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is a branch of Germanic paganism, Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse language, Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into Germanic peoples, distinc ...

persisted among segments of the population for some years afterward.

Iceland as a possession

The Middle Ages

TheIcelandic Commonwealth

The Icelandic Commonwealth, also known as the Icelandic Free State, was the political unit existing in Iceland between the establishment of the Althing () in 930 and the pledge of fealty to the Norwegian king with the Old Covenant in 1262. W ...

, established in the 10th century, faced internal strife during the Age of the Sturlungs

The Age of the Sturlungs or the Sturlung Era ( ) was a 42-/44-year period of violent internal strife in mid-13th-century Iceland. It is documented in the '' Sturlunga saga''. This period is marked by the conflicts of local chieftains, '' goðar'' ...

(c. 1220–1264). This period was marked by violent conflicts among chieftains, notably the Sturlung family, leading to the weakening of the Commonwealth's political structure. The culmination of these struggles resulted in the signing of the Old Covenant (Gamli sáttmáli

The Old Covenant (Modern Icelandic: ; Old Norse: ) was the name of the agreement which effected the union of Iceland and Norway. It is also known as ''Gissurarsáttmáli'', named after Gissur Þorvaldsson, the Icelandic chieftain who worked t ...

) in 1262–1264, bringing Iceland under Norwegian rule.

Environmental challenges further impacted medieval Icelandic society. Upon settlement, approximately 25-40% of Iceland was forested. However, extensive deforestation occurred as forests were cleared for timber, firewood, and to create grazing land for livestock. This led to significant soil erosion and a decline in arable land, exacerbating the difficulties of sustaining agriculture in Iceland's harsh climate.

Agriculture during this period was predominantly pastoral, focusing on livestock such as sheep, cattle, and horses. While early settlers cultivated barley, the cooling climate from the 12th century onwards made grain cultivation increasingly difficult. The Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

, beginning around 1300, brought colder and more unpredictable weather, further shortening growing seasons and making farming more challenging.

The Black Death reached Iceland in 1402–1404 and again in 1494–1495, with devastating effects. he first outbreak is estimated to have killed 50-60% of the population, while the second resulted in a 30-50% mortality rate. These pandemics significantly reduced the population, leading to social and economic disruptions.

Reformation and the Early Modern period

Around the middle of the 16th century, as part of the

Around the middle of the 16th century, as part of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, King Christian III of Denmark

Christian III (12 August 1503 – 1 January 1559) reigned as King of Denmark from 1534 and King of Norway from 1537 until his death in 1559. During his reign, Christian formed close ties between the church and the crown. He established ...

began to impose Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

on all his subjects. Jón Arason

Jón Arason (1484 – November 7, 1550) was an Icelandic Roman Catholic bishop and poet, who was executed in his struggle against the Reformation in Iceland.

Background

Jón Arason was born in Gryta, educated at Munkaþverá, the Benedictine ...

, the last Catholic bishop of Hólar

Hólar (; also Hólar í Hjaltadal ) is a small community in the Skagafjörður district of northern Iceland.

Location

Hólar is in the valley Hjaltadalur, some from the national capital of Reykjavík. It has a population of around 100. It is t ...

, was beheaded in 1550 along with two of his sons. The country subsequently became officially Lutheran, and Lutheranism has since remained the dominant religion.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Denmark imposed harsh trade restrictions on Iceland. Natural disasters, including volcanic eruptions and disease, contributed to a decreasing population. In the summer of 1627, Barbary Pirates

The Barbary corsairs, Barbary pirates, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen (in Muslim sources) were mainly Muslim corsairs and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barba ...

committed the events known locally as the Turkish Abductions

The Turkish Abductions ( ) were a series of slave raids by pirates from Algier and Salé that took place in Iceland in the summer of 1627.

The adjectival label "''Turkish''" () does not refer to ethnic Turks, country of Turkey or Turkic peop ...

, in which hundreds of residents were taken into slavery in North Africa and dozens killed; this was the only invasion in Icelandic history to have casualties. The 1707–08 Iceland smallpox epidemic is estimated to have killed a quarter to a third of the population. In 1783 the Laki

Laki () or Lakagígar (, ''Craters of Laki'') is a volcanic fissure in the western part of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, not far from the volcanic fissure of Eldgjá and the small village of Kirkjubæjarklaustur. The fissure is proper ...

volcano erupted, with devastating effects. In the years following the eruption, known as the Mist Hardships

Laki () or Lakagígar (, ''Craters of Laki'') is a volcanic fissure in the western part of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland, not far from the volcanic fissure of Eldgjá and the small village of Kirkjubæjarklaustur. The fissure is proper ...

(), over half of all livestock in the country died. Around a quarter of the population starved to death in the ensuing famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

.

1814–1918: independence movement

In 1814, following theNapoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, Denmark-Norway was broken up into two separate kingdoms via the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel () or Peace of Kiel ( Swedish and or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the other side on 14 January 1814 ...

, but Iceland remained a Danish dependency. Throughout the 19th century, the country's climate continued to grow colder, resulting in mass emigration to the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, particularly to the region of Gimli, Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

in Canada, which was sometimes referred to as New Iceland

New Iceland ( ) is the name of a region on Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba founded by Icelandic settlers in 1875.

The community of Gimli, which is home to the largest concentration of Icelanders outside of Iceland, is seen as the core of New Icela ...

. About 15,000 people emigrated, out of a total population of 70,000.

A national consciousness arose in the first half of the 19th century, inspired by romantic and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

ideas from mainland Europe. An Icelandic independence movement took shape in the 1850s under the leadership of Jón Sigurðsson

Jón Sigurðsson (17 June 1811 – 7 December 1879) was the leader of the 19th century icelandic nationalism, Icelandic independence movement.

Biography

Born at Hrafnseyri, in Arnarfjörður in the Westfjords area of Iceland, he was the son of ...

, based on the burgeoning Icelandic nationalism inspired by the '' Fjölnismenn'' and other Danish-educated Icelandic intellectuals. In 1874, Denmark granted Iceland a constitution and limited home rule. This was expanded in 1904, and Hannes Hafstein

Hannes Þórður Pétursson Hafstein (4 December 1861 – 13 December 1922) was an Icelandic politician and poet. In 1904 he became the first Icelander to be appointed to the Cabinets of Denmark, Danish Cabinet as the minister for Iceland in the ...

served as the first Minister for Iceland

Minister for Iceland (, ; ) was a post in the Danish cabinet for Icelandic affairs.

History

The post was established on 5 January 1874 as, according to the Constitution of Iceland, the executive power rested in the king of Denmark through the D ...

in the Danish cabinet.

1918–1944: independence and the Kingdom of Iceland

TheDanish–Icelandic Act of Union

The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, an agreement signed by Iceland and Denmark on 1 December 1918, recognized Iceland as a fully independent and sovereign state, known as the Kingdom of Iceland, which was freely associated to Denmark in a pers ...

, an agreement with Denmark signed on 1 December 1918 and valid for 25 years, recognised Iceland as a fully sovereign and independent state in a personal union

A personal union is a combination of two or more monarchical states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, involves the constituent states being to some extent in ...

with Denmark. The Government of Iceland established an embassy in Copenhagen and requested that Denmark carry out on its behalf certain defence and foreign affairs matters, subject to consultation with the Althing. Danish embassies around the world displayed two coats of arms and two flags: those of the Kingdom of Denmark and those of the Kingdom of Iceland

The Kingdom of Iceland (; ) was a sovereign and independent country under a constitutional and hereditary monarchy that was established by the Act of Union with Denmark signed on 1 December 1918. It lasted until 17 June 1944 when a national ...

. Iceland's legal position became comparable to those of countries belonging to the Commonwealth of Nations, such as Canada, whose sovereign is King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

.

During World War II, Iceland joined Denmark in asserting neutrality. After the German occupation of Denmark

At the outset of World War II in September 1939, Denmark declared itself neutral, but that neutrality did not prevent Nazi Germany from occupying the country soon after the outbreak of war; the occupation lasted until Germany's defeat. The ...

on 9 April 1940, the Althing replaced the King with a regent and declared that the Icelandic government would take control of its own defence and foreign affairs. A month later, British armed forces conducted Operation Fork

The United Kingdom invaded Iceland on 10 May 1940, during World War II using its Royal Navy and Royal Marines forces. The operation, codenamed Operation Fork, occurred because the British government feared that Iceland would be used militarily ...

, the invasion and occupation of the country, violating Icelandic neutrality. In 1941, the Government of Iceland, friendly to Britain, invited the then-neutral United States to take over its defence so that Britain could use its troops elsewhere.

1944–present: Republic of Iceland

On 31 December 1943, the

On 31 December 1943, the Danish–Icelandic Act of Union

The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union, an agreement signed by Iceland and Denmark on 1 December 1918, recognized Iceland as a fully independent and sovereign state, known as the Kingdom of Iceland, which was freely associated to Denmark in a pers ...

expired after 25 years. Beginning on 20 May 1944, Icelanders voted in a four-day plebiscite on whether to terminate the personal union with Denmark, abolish the monarchy, and establish a republic. The vote was 97% to end the union, and 95% in favour of the new republican constitution. Iceland formally became a republic on 17 June 1944, with Sveinn Björnsson

Sveinn Björnsson (; 27 February 1881 – 25 January 1952) was the first president of Iceland, serving from 1944 to 1952.

Background, education and legal career

Sveinn was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, as the son of Björn Jónsson (editor and ...

as its first president.

In 1946, the US Defence Force Allied left Iceland. The nation formally became a member of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

on 30 March 1949, amid domestic controversy and riots. On 5 May 1951, a defence agreement was signed with the United States. American troops returned to Iceland as the Iceland Defence Force and remained throughout the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

. The US withdrew the last of its forces on 30 September 2006.

Iceland prospered during the Second World War. The immediate post-war period was followed by substantial economic growth

In economics, economic growth is an increase in the quantity and quality of the economic goods and Service (economics), services that a society Production (economics), produces. It can be measured as the increase in the inflation-adjusted Outp ...

, driven by the industrialisation of the fishing industry and the US Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred $13.3 billion (equivalent to $ in ) in economic recovery pr ...

programme, through which Icelanders received the most aid per capita of any European country (at US$209, with the war-ravaged Netherlands a distant second at US$109).

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir (; born 15 April 1930) is an Icelandic politician who served as the fourth president of Iceland from 1980 to 1996, the first woman to hold the position and the first in the world to be democratically elected president of ...

assumed Iceland's presidency on 1 August 1980, making her the first elected female head of state in the world.

The 1970s were marked by the Cod Wars

The Cod Wars (; also known as , ; ) were a series of 20th-century confrontations between the United Kingdom (with aid from West Germany) and Iceland about Exclusive economic zone, fishing rights in the North Atlantic. Each of the disputes ended ...

—several disputes with the United Kingdom over Iceland's extension of its fishing limits to offshore. Iceland hosted a summit in Reykjavík in 1986 between United States President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, during which they took significant steps towards nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament is the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons. Its end state can also be a nuclear-weapons-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated. The term ''denuclearization'' is also used to describe the pro ...

. A few years later, Iceland became the first country to recognise the independence of Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

, and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

as they broke away from the USSR. Throughout the 1990s, the country expanded its international role and developed a foreign policy orientated towards humanitarian and peacekeeping causes. To that end, Iceland provided aid and expertise to various NATO-led interventions in Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

, and Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

.

Iceland joined the European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade Asso ...

in 1994, after which the economy was greatly diversified and liberalised. International economic relations increased further after 2001 when Iceland's newly deregulated banks began to raise great amounts of external debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be government, governments, corporation, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or f ...

, contributing to a 32 percent increase in Iceland's gross national income

The gross national income (GNI), previously known as gross national product (GNP), is the total amount of factor incomes earned by the residents of a country. It is equal to gross domestic product (GDP), plus factor incomes received from ...

between 2002 and 2007.

Economic boom and crisis

In 2003–2007, following the privatisation of the banking sector under the government ofDavíð Oddsson

Davíð Oddsson (pronounced ; born 17 January 1948) is an Icelandic politician, and the longest-serving prime minister of Iceland, in office from 1991 to 2004. From 2004 to 2005 he served as Ministry for Foreign Affairs (Iceland), foreign minis ...

, Iceland moved towards having an economy based on international investment banking and financial services. It was quickly becoming one of the most prosperous countries in the world, but was hit hard by a major financial crisis. The crisis resulted in the greatest migration from Iceland since 1887, with a net emigration of 5,000 people in 2009.

Since 2012

Iceland's economy stabilised under the government ofJóhanna Sigurðardóttir

Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir (; born 4 October 1942) is an Icelandic politician, who served as prime minister of Iceland from 2009 to 2013.

Elected as an MP from 1978 to 2013, she was appointed as Iceland's Minister of Social Affairs and Social ...

and grew by 1.6% in 2012. The centre-right Independence Party was returned to power in coalition with the Progressive Party in the 2013 election. In the following years, Iceland saw a surge in tourism as the country became a popular holiday destination. In 2016, Prime Minister Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson

Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson (; born 12 March 1975) is an Icelandic politician who was the prime minister of Iceland from May 2013 until April 2016. He was also chairman of the Progressive Party from 2009 to October 2016. He was elected to t ...

resigned after being implicated in the Panama Papers

The Panama Papers () are 11.5 million leaked documents (or 2.6 terabytes of data) published beginning April 3, 2016. The papers detail financial and attorney–client information for more than 214,488 offshore entities. These document ...

scandal. Early elections in 2016 resulted in a right-wing coalition government of the Independence Party, Viðreisn

Viðreisn (), officially known in English as the Liberal Reform Party, is a Liberalism, liberal political party political parties in Iceland, in Iceland positioned on the Centrism, centre to Centre-right politics, centre-right of the political spe ...

and Bright Future. This government fell when Bright Future quit the coalition due to a scandal involving then-Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson's father's letter of support for a convicted child sex offender. Snap elections in October 2017 brought to power a new coalition consisting of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party, and the Left-Green Movement

The Left-Green Movement (, ), also known by its short-form name Vinstri græn (VG), is an eco-socialist political party in Iceland.

Since the 2024 Icelandic parliamentary election, the party has had no members in the Althing. The party chairper ...

, headed by Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Katrín Jakobsdóttir (; born 1 February 1976) is an Icelandic former politician who served as the prime minister of Iceland from December 2017 to April 2024 and was a member of the Althing for the Reykjavík North constituency from 2007 to 202 ...

.

After the 2021 parliamentary election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

, the new government was, just like the previous government, a tri-party coalition of the Independence Party, the Progressive Party, and the Left-Green Movement, headed by Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir. In April 2024, Bjarni Benediktsson of the Independence party succeeded Katrín Jakobsdóttir as prime minister. In November 2024, centre-left Social Democratic Alliance

The Social Democratic Alliance (, ) is a Social democracy, social democratic List of political parties in Iceland, political party in Iceland. The party is positioned on the Centre-left politics, centre-left of the political spectrum and their ...

became the biggest party in a snap election

A snap election is an election that is called earlier than the one that has been scheduled. Snap elections in parliamentary systems are often called to resolve a political impasse such as a hung parliament where no single political party has a ma ...

, meaning Social Democratic Kristrun Frostadottir became the next Prime Minister of Iceland.

Geography

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

, which passes through the small Icelandic island of Grímsey

Grímsey () is a small Icelandic island, off the north coast of the main island of Iceland, where it straddles the Arctic Circle. Grímsey is also known for the puffins and other sea birds which visit the island for breeding.

The island is a ...

off the main island's northern coast. The country lies between latitudes 63 and 68°N, and longitudes 25 and 13°W.

Iceland is closer to continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

than to mainland North America, although it is closest to Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

(), an island of North America. Iceland is generally included in Europe for geographical, historical, political, cultural, linguistic and practical reasons. Geologically, the island includes parts of both continental plates. The closest bodies of land in Europe are the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

(); Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norway, Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: la ...

Island (); Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and the Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an Archipelago, island chain off the west coast of mainland Scotland.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islan ...

, both about ; and the Scottish mainland and Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, both about . The nearest part of Continental Europe is mainland Norway, about away, while mainland North America is away, at the northern tip of Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

.

Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island, and Europe's second-largest island after Great Britain and before Ireland. The main island covers , but the entire country is in size, of which 62.7% is

Iceland is the world's 18th-largest island, and Europe's second-largest island after Great Britain and before Ireland. The main island covers , but the entire country is in size, of which 62.7% is tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

. Iceland contains about 30 minor islands, including the lightly populated Grímsey and the Vestmannaeyjar

Vestmannaeyjar (, sometimes anglicized as Westman Islands) is a municipality and archipelago off the south coast of Iceland.

The largest island, Heimaey, has a population of 4,414, most of whom live in the archipelago's main town, Vestmannaeyja ...

archipelago. Lakes and glaciers cover 14.3% of its surface; only 23% is vegetated. The largest lakes are Þórisvatn

Þórisvatn (; sometimes anglicized to Thorisvatn) is the largest lake of Iceland, situated at the south end of the Sprengisandur plateau within the highlands of Iceland.

It is a reservoir with a surface area of about and is fed by the river ...

reservoir: and Þingvallavatn

Þingvallavatn (, ), anglicised as Thingvallavatn, is a rift valley lake in southwestern Iceland. With a surface of 84 km2 it is the largest natural lake in Iceland. Its greatest depth is 114 m. At the northern shore of the lake, at Þingvellir ( ...

: ; other important lakes include Lagarfljót

Lagarfljót () also called Fljótið is a river situated in the east of Iceland near Egilsstaðir. Its surface measures and it is long; its greatest width is and its greatest depth . The 27 MW Lagarfossvirkjun hydropower station is located at ...

and Mývatn

Mývatn () is a shallow lake situated in an area of active volcanism in the north of Iceland, near Krafla volcano. It has a high amount of biological activity. The lake and the surrounding wetlands provides a habitat for a number of waterbirds, ...

. Jökulsárlón

Jökulsárlón (; translates to "glacial river lagoon") is a large glacial lake in southern part of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. Situated at the head of the Breiðamerkurjökull glacier, it developed into a lake after the glacier started r ...

is the deepest lake, at .

Geologically, Iceland is part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a Divergent boundary, divergent or constructive Plate tectonics, plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest mountai ...

, a ridge along which the oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramaf ...

spreads and forms new crust. This part of the mid-ocean ridge is located above a mantle plume, causing Iceland to be subaerial

In natural science, subaerial (literally "under the air") has been used since 1833,Subaerial

in the Merriam- ...

(above the surface of the sea). The ridge marks the boundary between the in the Merriam- ...

Eurasian

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents dates back to antiq ...

and North American Plates, and Iceland was created by rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics. Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben ...

ing and accretion through volcanism along the ridge.

Many fjord

In physical geography, a fjord (also spelled fiord in New Zealand English; ) is a long, narrow sea inlet with steep sides or cliffs, created by a glacier. Fjords exist on the coasts of Antarctica, the Arctic, and surrounding landmasses of the n ...

s punctuate Iceland's coastline, which is also where most settlements are situated. The island's interior, the Highlands of Iceland

The Highland (Icelandic language, Icelandic: ''Hálendið)'' or The Central Highland is an area that comprises much of the interior land of Iceland. The Highland is situated above and is mostly uninhabitable. The soil is primarily volcanic as ...

, is a cold and uninhabitable combination of sand, mountains, and lava field

A lava field, sometimes called a lava bed, is a large, mostly flat area of lava flows. Such features are generally composed of highly fluid basalt lava, and can extend for tens or hundreds of kilometers across the underlying terrain.

Morp ...

s. The major towns are the capital city of Reykjavík

Reykjavík is the Capital city, capital and largest city in Iceland. It is located in southwestern Iceland on the southern shore of Faxaflói, the Faxaflói Bay. With a latitude of 64°08′ N, the city is List of northernmost items, the worl ...

, along with its outlying towns of Kópavogur

Kópavogur () is a town in Iceland that is the country's second-largest municipality by population.

It lies immediately south of Reykjavík and is part of the Capital Region (Iceland), Capital Region. The name literally means ''seal pup inlet''. ...

, Hafnarfjörður

Hafnarfjörður, officially Hafnarfjarðarkaupstaður, is a port town and municipality in Iceland, located about south of Reykjavík. The municipality consists of two non-contiguous areas in the Capital Region (Iceland), Capital Region, on the s ...

, and Garðabær

Garðabær () is a town and municipality in the Capital Region of Iceland.

History

Garðabær is a growing town in the Capital Region. It is the fifth largest municipality in Iceland with a population of 20,116 (1 January 2025).

The site of Gar ...

, nearby Reykjanesbær

Reykjanesbær () is a municipality on the Southern Peninsula (''Suðurnes'') in Iceland, though the name is also used by locals to refer to the suburban region of Keflavík and Njarðvík which have grown together over the years. The municipality ...

where the international airport is located, and the town of Akureyri

Akureyri (, ) is a town in northern Iceland, the country's fifth most populous Municipalities of Iceland, municipality (under the official name of Akureyrarbær , 'town of Akureyri') and the largest outside the Capital Region (Iceland), Capital R ...

in northern Iceland. The island of Grímsey on the Arctic Circle contains the northernmost habitation of Iceland, whereas Kolbeinsey

Kolbeinsey (; also known as Kolbeinn's Isle, Seagull Rock, Mevenklint, Mevenklip, or Meeuw Steen) is a small Icelandic islet in the Greenland Sea located off the northern coast of Iceland, north-northwest of the island of Grímsey. It is the n ...

contains the northernmost point of Iceland. Iceland has three national parks: Vatnajökull National Park

Vatnajökull National Park ( ) is one of three national parks in Iceland, and is the largest one. It encompasses all of Vatnajökull glacier and extensive surrounding areas. These include the national parks previously existing at Skaftafell in th ...

, Snæfellsjökull National Park

Snæfellsjökull (, ''snow-fell glacier'') is a 700,000-year-old glacier-capped stratovolcano in western Iceland. It is situated on the westernmost part of the Snæfellsnes peninsula. Sometimes it may be seen from the city of Reykjavík over Fax ...

, and Þingvellir National Park

Þingvellir (, anglicised as ThingvellirThe spelling ''Pingvellir'' is sometimes seen, although the letter "p" is unrelated to the letter "þ" (thorn), which is pronounced as "th".) was the site of the Alþing, the annual parliament of Iceland f ...

. The country is considered a "strong performer" in environmental protection.

Geology

A geologically young land at 16 to 18 million years old, Iceland is the surface expression of the Iceland Plateau, a

A geologically young land at 16 to 18 million years old, Iceland is the surface expression of the Iceland Plateau, a large igneous province

A large igneous province (LIP) is an extremely large accumulation of igneous rocks, including intrusive ( sills, dikes) and extrusive (lava flows, tephra deposits), arising when magma travels through the crust towards the surface. The format ...

forming as a result of volcanism from the Iceland hotspot

The Iceland hotspot is a hotspot that is partly responsible for the high volcanic activity that has formed the Iceland Plateau and the island of Iceland. It contributes to understanding the geological deformation of Iceland.

Iceland is one ...

and along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a Divergent boundary, divergent or constructive Plate tectonics, plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the List of longest mountain chains on Earth, longest mountai ...

, the latter of which runs right through it. This means that the island is highly geologically active with many volcanoes including Hekla

Hekla (), or Hecla, is an active stratovolcano in the south of Iceland with a height of . Hekla is one of Iceland's most active volcanoes; over 20 eruptions have occurred in and around the volcano since the year 1210. During the Middle Ages, th ...

, Eldgjá

Eldgjá (, "fire canyon") is a volcano and a canyon in Iceland. Eldgjá is part of the Katla volcano; it is a segment of a long chain of volcanic craters and fissure vents that extends northeast away from Katla volcano almost to the Vatnajök ...

, Herðubreið

Herðubreið (, ''broad-shouldered'') is a tuya in the northern part of Vatnajökull National Park, Iceland. It is situated in the Highlands of Iceland at the east side of the Ódáðahraun () desert and close to Askja volcano. The desert is a ...

, and Eldfell

Eldfell is a volcanic cone just over high on the Icelandic island of Heimaey in the Westman Islands. It formed in a volcanic eruption that began without warning on the eastern side of Heimaey on 23 January 1973. The name means ''Hill of Fire ...

. The volcanic eruption of Laki