Carreira Da Índia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Portuguese Indian Armadas (; meaning "Armadas of India") were the fleets of ships funded by the Crown of Portugal, and dispatched on an annual basis from

The India armada typically left

The India armada typically left  Return fleets were a different story. The principal worry of the return fleets was the fast dangerous waters of the inner Mozambican channel, which was particularly precarious for heavily loaded and less maneuverable ships. In the initial decades, the return fleet usually set out from

Return fleets were a different story. The principal worry of the return fleets was the fast dangerous waters of the inner Mozambican channel, which was particularly precarious for heavily loaded and less maneuverable ships. In the initial decades, the return fleet usually set out from

The was usually contrasted to the (Mina route). The latter meant striking ''southeast'' in the doldrums to catch the

The was usually contrasted to the (Mina route). The latter meant striking ''southeast'' in the doldrums to catch the  Nonetheless, if the armada had time, or got into trouble for some reason, the stopping choice was

Nonetheless, if the armada had time, or got into trouble for some reason, the stopping choice was

The ships of an India armada were typically

The ships of an India armada were typically

The admiral of an armada, necessarily a nobleman of some degree, was known as the ''capitão-mor'' (captain-major), with full jurisdiction over the fleet. There was also usually a designated ''soto-capitão'' (vice-admiral), with a commission to assume command should tragedy befall the captain-major. The vice-admirals were also useful if a particular armada needed to be split into separate squadrons. If an armada carried a viceroy or governor of the Indies, he typically assumed the senior position (although in practice many delegated the decision-making during the journey to their flagship's captain).

Each India ship had a ''capitão'' (

The admiral of an armada, necessarily a nobleman of some degree, was known as the ''capitão-mor'' (captain-major), with full jurisdiction over the fleet. There was also usually a designated ''soto-capitão'' (vice-admiral), with a commission to assume command should tragedy befall the captain-major. The vice-admirals were also useful if a particular armada needed to be split into separate squadrons. If an armada carried a viceroy or governor of the Indies, he typically assumed the senior position (although in practice many delegated the decision-making during the journey to their flagship's captain).

Each India ship had a ''capitão'' (

In the early armadas, the captain-major and captains of the carracks were obliged, by King

In the early armadas, the captain-major and captains of the carracks were obliged, by King

The first Portuguese factory in Asia was set up in

The first Portuguese factory in Asia was set up in

While

While

For an entire century, the Portuguese had managed to monopolize the India run. The spice trade itself was not monopolized – through the 16th century, the

For an entire century, the Portuguese had managed to monopolize the India run. The spice trade itself was not monopolized – through the 16th century, the

Vol. 1 (Dec I, Lib. 1–5)Vol. 2 (Dec I, Lib. 6–10)Vol. 3 (Dec II, Lib. 1–5)Vol. 4 (Dec II, Lib. 6–10)

*

Dec X, Pt. 1, Bk. 1, c. 16

* Luís Vaz de Camões (1572) ''Os Lusíadas''. [Eng. trans. by W.J. Mickle, 1776, as ''The Lusiad, or the discovery of India, an epic poem''. trans. by R.F. Burton, 1880, as ''The Lusiads''; trans. by J.J. Aubertin, 1878–1884, ''The Lusiads of Camoens''] * Fernão Lopes de Castanheda (1551–1560) ''História do descobrimento & conquista da Índia pelos portugueses'' 833 edition*

Vol 1Vol. 2Vol 3

artially trans. H.E. Stanley, 1869, as ''The Three Voyages of Vasco de Gama, and his viceroyalty'' London: Hakluyt Society.* Damião de Goes (1566–67) ''Chrónica do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel, da Gloriosa Memoria, Ha qual por mandado do Serenissimo Principe, ho Infante Dom Henrique seu Filho, ho Cardeal de Portugal, do Titulo dos Santos Quatro Coroados, Damiam de Goes collegio & compoz de novo.'' (As reprinted in 1749, Lisbon: M. Manescal da Costa

online

* João de Lisboa (c. 1519) ''Livro de Marinharia: tratado da agulha de marear. Roteiros, sondas, e outros conhecimentos relativos á navegação'', first pub. 1903, Lisbon: Libanio da Silva

online

*Vol. 2

* Duarte Pacheco Pereira (c. 1509) ''Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis'

online

*''Relação das Náos e Armadas da India com os Sucessos dellas que se puderam Saber, para Noticia e Instrucção dos Curiozos, e Amantes da Historia da India'' (Codex Add. 20902 of the British Library), . António de Ataíde, orig. editor.Transcribed and reprinted in 1985, by M.H. Maldonado, Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra

online

*

offprint

* Bouchon, G. (1985) "Glimpses of the Beginnings of the Carreira da India", in T.R. De Souza, editor, ''Indo-Portuguese history: old issues, new questions''. New Delhi: Concept. pp. 40–55. * Castro, Filipe Vieira de (2005) ''The Pepper Wreck: a Portuguese Indiaman at the mouth of the Tagus river''. College Station, TX: Texas A & M Press. * Cipolla, C.M. (1965) ''Guns, Sails and Empires: Technological innovation and the early phases of European Expansion, 1400–1700.'' New York: Minerva. *

internet 2003

* Hornsborough, J. (1852) ''The India directory, or, Directions for sailing to and from the East Indies, China, Australia and the interjacent ports of Africa and South America'' London: Allen. * Hutter, Lucy Maffei (2005) ''Navegação nos séculos XVII e XVIII: rumo: Brasil'' São Paulo: UNESP. * Logan, W. (1887) ''Malabar Manual'', 2004 reprint, New Delhi: Asian Education Services. * Mathew, K.N. (1988) ''History of the Portuguese Navigation in India''. New Delhi: Mittal. * Nair, K.R. (1902) "The Portuguese in Malabar", ''Calcutta Review'', Vol. 115, pp. 210–251 * Newitt, M.D. (2005) ''A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668''. London: Routledge. * Pedroso, S.J. (1881) ''Resumo historico ácerca da antiga India Portugueza, acompanhado de algumas reflexões concernentes ao que ainda possuimos na Asia, Oceania, China e Africa; com um appendice''. Lisbon: Castro Irmão * Pereira, M.S. (1979) "Capitães, naus e caravelas da armada de Cabral", ''Revista da Universidade de Coimbra'', Vol. 27, pp. 31–134 * Pimentel, M. (1746) ''Arte de navegar: em que se ensinam as regras praticas, e os modos de cartear, e de graduar a balestilha por via de numeros, e muitos problemas uteis á navegaçao : e Roteyro das viagens, e costas maritimas de Guiné, Angóla, Brasil, Indias, e Ilhas Occidentaes, e Orientaes''Francisco da Silv

Vol. I – Arte de NavegarVol II – Roterio

spec

India Oriental

* Quintella, Ignaco da Costa (1839–40) ''Annaes da Marinha Portugueza'', 2 vols, Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias. * Rodrigues, J.N. and T. Devezas (2009) ''Portugal: o pioneiro da globalização : a Herança das descobertas''. Lisbon: Centro Atlantico * de Silva, C.R. (1974) "The Portuguese East India Company 1628–1633", ''Luso-Brazilian Review'', Vol. 11 (2), pp. 152–205. * Smith, S.H. (2008) "'Profits sprout like tropical plants': A fresh look at what went wrong with the Eurasian spice trade, c. 1550–1800", ''Journal of Global History'', Vol. 3, pp. 389–418. * Sousa Viterbo, Francisco M. de (1897) ''Trabalhos Náuticos dos Portuguezes nos Seculos XVI e XVII'', Lisbon. * Souza, T.R. de (1977) "Marine Insurance and Indo-Portuguese Trade: An aid to maritime historiography", ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', Vol. 14 (3), pp. 377–84 * Subrahmanyam, S. (1997) ''The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. * Steensgaard, N. (1985) "The Return Cargoes of the Carreira in the 16th and early 17th Century", in T. De Souza, editor, ''Indo-Portuguese history: old issues, new questions''. New Delhi: Concept. pp. 13–31. * Stephens, H.M. (1897) ''Albuquerque''. Oxford: Clarendon. * Theal, George McCall (1898–1903) ''Records of South-eastern Africa collected in various libraries & archive departments in Europe'', 9 vols., London: Clowes for Gov of Cape Colony. * Theal, George McCall (1902) ''The Beginning of South African History''. London: Unwin. * Vila-Santa, Nuno (2020), ''The Portuguese India Run (16th-18th centuries): A Bibliography'

* Waters, D.W. (1988) "Reflections Upon Some Navigational and Hydrographic Problems of the XVIth Century Related to the voyage of Bartolomeu Dias", ''Revista da Universidade de Coimbra'', Vol. 34, pp. 275–347

offprint

* Whiteway, R.S. (1899) ''The Rise of Portuguese Power in India, 1497–1550''. Westminster: Constable. {{Authority control Portuguese India Armadas, Maritime history Maritime history of Portugal History of international trade Trade routes Economic history of Portugal Economic history of India Portuguese India Military history of India History of Portuguese Mozambique Colonial Kerala 15th-century establishments in Portuguese India 1650 disestablishments in Portuguese India Naval warfare Portuguese colonisation in Asia 1497 establishments in Asia

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

to India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. The principal destination was Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

, and previously Cochin

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernaku ...

. These armadas undertook the () from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, following the maritime discovery of the Cape route

The European-Asian sea route, commonly known as the sea route to India or the Cape Route, is a shipping route from the European coast of the Atlantic Ocean to Asia's coast of the Indian Ocean passing by the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas ...

, to the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographic region of Asia below the Himalayas which projects into the Indian Ocean between the Bay of Bengal to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west. It is now divided between Bangladesh, India, and Pakista ...

by Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

in 1497–99.

The annual Portuguese India armada was the main carrier of the spice trade

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in t ...

between Europe and Asia during the 16th Century. The Portuguese monopoly on the Cape route was maintained for a century, until it was breached by Dutch and English competition in the early 1600s. The Portuguese India armadas declined in importance thereafter. During the Dutch occupation of Cochin and the Dutch siege of Goa, the harbour of '' Bom Bahia'', now known as Mumbai (Bombay)

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial capital and the most populous city proper of India with an estimated population of 12.5 ...

, off the coast of the northern Konkan

The Konkan is a stretch of land by the western coast of India, bound by the river Daman Ganga at Damaon in the north, to Anjediva Island next to Karwar town in the south; with the Arabian Sea to the west and the Deccan plateau to the eas ...

region, served as the standard diversion for the armadas.

The India Run

For a long time after its discovery by Vasco da Gama, the sea route to India via theCape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

was dominated by the Portuguese India armada – the annual fleet dispatched from Portugal to India, and after 1505, the Estado da India

The State of India, also known as the Portuguese State of India or Portuguese India, was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded seven years after the discovery of the sea route to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama, a subject of the ...

. Between 1497 and 1650, there were 1033 departures of ships at Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

for the ''Carreira da Índia'' ("India Run").

Timing

Lisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

and each leg of the voyage took approximately six months.Duarte Pacheco Pereira (1509) strongly recommended February as the ideal departure month. Godinho (1963: v. 3, pp. 43–44) calculates that 87% of departures left in March or April, and the 13% outside that range were usually destined for elsewhere (Africa, Arabia). The critical determinant of the timing was the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

winds of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. The monsoon was a southwesterly wind (i.e. blew from East Africa to India) in the summer (between May and September) and then abruptly reversed itself and became a northeasterly (from India to Africa) in the winter (between October and April). The ideal timing was to pass the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

around June–July and get to the East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

n middle coast by August, just in time to catch the summer monsoon winds to India, arriving around early September. The return trip from India would typically begin in January, taking the winter monsoon back to Lisbon along a similar route, arriving by the summer (June–August). Overall, the round trip took a little over a year, minimizing the time at sea.

The critical step was ensuring the armada reached East Africa on time. Ships that failed to reach the equatorial latitude on the East African coast by late August would be stuck in Africa and have to wait until next spring to undertake an Indian Ocean crossing, and would then have to wait in India until the winter to begin their return, so any delay in East Africa during those critical few weeks of August could end up adding an entire extra year to a ship's journey.Godinho (1963: v. 3, p. 44) calculates that around 11% of outgoing ships missed the monsoon and ended up having to winter in East Africa.

The circumnavigation of Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

opened an alternative route to get to India, which gave more flexibility in timing. The rule that quickly emerged was that if an outbound armada doubled the Cape of Good Hope before mid-July, then it should follow the old "inner route" – that is, sail into the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

, up the East African coast until the equatorial latitude (around Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

, in modern-day Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

), then take the southwesterly monsoon across the ocean to India. If, however, the armada doubled the Cape after mid-July, then it was obliged to sail the "outer route" – that is, strike out straight east from South Africa, go under the southern tip of Madagascar, and then turn up from there, taking a northerly path through the Mascarenes

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of Réunion. Their na ...

islands, across the open ocean to India. While the outer route did not have the support of African staging posts and important watering stops, it sidestepped sailing directly against the post-summer monsoon.

Return fleets were a different story. The principal worry of the return fleets was the fast dangerous waters of the inner Mozambican channel, which was particularly precarious for heavily loaded and less maneuverable ships. In the initial decades, the return fleet usually set out from

Return fleets were a different story. The principal worry of the return fleets was the fast dangerous waters of the inner Mozambican channel, which was particularly precarious for heavily loaded and less maneuverable ships. In the initial decades, the return fleet usually set out from Cochin

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernaku ...

in December, although that was eventually pushed forward to January. January 20 was the critical date, after which all return fleets were obliged to follow the outer route (east of Madagascar) which was deemed calmer and safer for their precious cargo. That meant they missed the important watering stop on Mozambique island on the return leg and had to put in elsewhere later, such as Mossel Bay

Mossel Bay () is a harbour town of about 170,000 people on the Garden Route of South Africa. It is an important tourism and farming region of the Western Cape Province. Mossel Bay lies 400 kilometres east of the country's seat of parliament, Ca ...

or St. Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

. Between 1525 and 1579, ''all'' return fleets were ordered to follow the outer route. This rule was temporarily suspended between the 1570s and 1590s. From 1615, a new rule was introduced whereby return fleets from Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

were allowed to use the inner route, but return fleets from Cochin still had to use the outer route. With the entry of Dutch and English competition in the 1590s, the start of the return legs were delayed until February and March, with the predictable upsurge in lost and weather-delayed ships.Godinho (1963: v. 3, p. 46)

Arrival times in Portugal varied, usually between mid-June and late August. It was customary for return fleets to send their fastest ship ahead to announce the results in Lisbon, before the rest of the fleet arrived later that summer.

Because of the timing, an armada had to leave Lisbon (February–April) before the previous year's armada returned (June–August). To get news of the latest developments in India, the outgoing armada relied on notes and reports left along the way at various African staging posts by the returning fleet.

Outward voyage

Portuguese India armadas tended to follow the same outward route. There were several staging posts along the route of the India Run that were repeatedly used.For old '' roteiro''s of the India Run, see Duarte Pacheco Pereira (1509), João de Lisboa (1519: pp. 69ff) and Manuel Pimentel (1746: pp. 381ff) Setting out fromLisbon

Lisbon ( ; ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 567,131, as of 2023, within its administrative limits and 3,028,000 within the Lisbon Metropolitan Area, metropolis, as of 2025. Lisbon is mainlan ...

(February–April), India-bound naus took the Canary Current

The Canary Current is a wind-driven surface current that is part of the North Atlantic Gyre. This eastern boundary current branches south from the North Atlantic Current and flows southwest about as far as Senegal where it turns west and later jo ...

straight southwest to the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

. The islands were owned by Castile and so this was not a usual watering stop for the Portuguese India armadas, except in emergencies.

The first real obstacle on the route was the Cape Verde

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

peninsula (Cap-Vert, Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

), around which the Canary Current ends and the equatorial drift begins. Although not difficult to double, it was a concentration point of sudden storms and Cape Verde-type hurricanes, so ships were frequently damaged.

The Cape Verde islands

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

, to the west of the Cape Verde peninsula, were the usual first stop for India-bound ships. Relative scarcity of water and supplies on the islands made this a sub-optimal stop, but the islands (especially Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile (), is the capital and largest city of Chile and one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is located in the country's central valley and is the center of the Santiago Metropolitan Regi ...

) served as a harbor against storms and were frequently a pre-arranged point for the collection and repair of damaged ships.

The (Bay of Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

, Senegal) was a common watering stop for ships after doubling Cape Verde. The shores were controlled by Wolof

Wolof or Wollof may refer to:

* Wolof people, an ethnic group found in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* Wolof language, a language spoken in Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania

* The Wolof or Jolof Empire, a medieval West African successor of the Mal ...

and Serer kingdoms, whose relations with the Portuguese were ambivalent, so a warm reception on the mainland could not always be counted on. In the middle of the bay was the island of Gorée

(; "Gorée Island"; ) is one of the 19 (i.e. districts) of the city of Dakar, Senegal. It is an island located at sea from the main harbour of Dakar (), famous as a destination for people interested in the Atlantic slave trade.

Its populatio ...

(), a safe anchoring spot, but the island itself lacked drinkable water. As a result, ships frequently watered and repaired at certain mainland points along the Petite Côte

The Petite Côte is a stretch of coast in Senegal, running south from the Cap-Vert peninsula to the Saloum Delta, near the border with the Gambia.

The northern section near Dakar contains seaside resorts such as Saly Portudal, Rufisque, Nian ...

of Senegal such as (now Rufisque

Rufisque (; Wolof: Tëngeéj) is a city in the Dakar region of western Senegal, at the base of the Cap-Vert Peninsula east of Dakar, the capital. It has a population of 295,459 (2023 census).

) and (now Saly-Portudal). It was not unheard of for India naus to water much further south, among the many inlets and islands (e.g. Bissagos) along the African coast to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

.

Below Cape Verde, around the latitudes of Sierra Leone, began the Atlantic doldrums, a calm low pressure region on either side of the equator with little or no winds. At this time of year, the doldrums belt usually ranged between 5° N and 5° S. The exact latitude where the doldrums lay varies because of the "Atlantic mini-monsoon" phenomenon. During the summer months, the heating of West African mainland pulls winds up from the equator, shunting the doldrums belt further north. In the southern hemisphere, below the doldrums, the counter-clockwise gyre

In oceanography, a gyre () is any large system of ocean surface currents moving in a circular fashion driven by wind movements. Gyres are caused by the Coriolis effect; planetary vorticity, horizontal friction and vertical friction determine the ...

of the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

and the southeasterly trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, ...

s, prevented sailing directly southeast to the Cape.

Passing the doldrums was a navigational challenge, and pilots had to avail themselves deftly of the currents and every little breeze they could get to stay on course. The usual tactic was to proceed south or even southeast along the West African coast as long as possible, until the doldrums hit (usually around Sierra Leone), then to strike southwest sharply, drift over the doldrums and then catch the South Equatorial Current

The South Equatorial Current are ocean currents in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Ocean that flow east-to-west between the equator and about 20 degrees south. In the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, it extends across the equator to about 5 degre ...

(the top arm of the South Atlantic gyre) towards the coast of Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

. This was usually referred to as following the (literally, 'turn of the sea', i.e. the South Atlantic gyre).

The was usually contrasted to the (Mina route). The latter meant striking ''southeast'' in the doldrums to catch the

The was usually contrasted to the (Mina route). The latter meant striking ''southeast'' in the doldrums to catch the Equatorial Counter Current

The Equatorial Counter Current is an eastward flowing, wind-driven current which extends to depths of in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. More often called the North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC), this current flows west-to-east at ...

(or Guinea Current) east into the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea (French language, French: ''Golfe de Guinée''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Golfo de Guinea''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Golfo da Guiné'') is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez i ...

. This was the usual route to the fort of São Jorge da Mina on the Portuguese Gold Coast

The Portuguese Gold Coast was a Portuguese colony on the West African Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) along the Gulf of Guinea.

From their seat of power at the fortress of São Jorge da Mina (established in 1482 and located in modern Elmina) ...

. This was ''not'' part of the India run. The route from Mina down to South Africa involved tacking ''against'' the southeasterly trade winds and the contrary Benguela Current

The Benguela Current is the broad, northward flowing ocean current that forms the eastern portion of the South Atlantic Ocean gyre. The current extends from roughly Cape Point in the south, to the position of the Angola-Benguela Front in the no ...

, a particularly tiresome task for heavy square rig

Square rig is a generic type of sail plan, sail and rigging arrangement in which a sailing ship, sailing vessel's primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spar (sailing), spars that are perpendicular (or wikt:square#Adjective, square) to t ...

ged carrack

A carrack (; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for Europea ...

s. However, it sometimes happened that by poor piloting, India naus would be inadvertently caught by the Guinea counter-current and forced to take that route, but such ships would not be likely to reach India that year.The had been the usual route used by all Portuguese explorers to Africa until the end of the 15th century. The first fleet to sail the was Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

's first fleet in 1497. However, credit for the discovery of the as a route to the Cape ought to be given to Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the Cape Agulhas, southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lies ...

, who in 1488–89, first discovered the westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes (about ...

below 30°S and the South Atlantic Current, from which was deduced the probable existence of the quicker and easier route to the Cape. See Coutinho (1951–5: 319–63) and Waters (1988)

Assuming the India armada successfully caught the south equatorial current of the , the armada would drift southwest through the doldrums and reach the southbound Brazil Current

The Brazil Current is a warm water current that flows south along the Brazilian south coast to the mouth of the Río de la Plata.

Description

This current is caused by diversion of a portion of the Atlantic South Equatorial Current from where ...

off the coast of Brazil (around Pernambuco

Pernambuco ( , , ) is a States of Brazil, state of Brazil located in the Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast region of the country. With an estimated population of 9.5 million people as of 2024, it is the List of Brazilian states by population, ...

). Although India naus did not usually stop in Brazil, it was not unheard of to put in a brief watering stop at Cape Santo Agostinho (Pernambuco, Brazil), especially if the southeasterly trade winds were particularly strong (pilots had to be careful not to allow themselves to be caught and driven backwards).

From the environs of Pernambuco, the India naus sailed straight south along the Brazil Current, until about the latitude of the Tropic of Capricorn

The Tropic of Capricorn (or the Southern Tropic) is the circle of latitude that contains the subsolar point at the December (or southern) solstice. It is thus the southernmost latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. It also reach ...

, visibly the Abrolhos islands or the Trindade and Martim Vaz

Trindade and Martim Vaz (, ) is an archipelago located in the South Atlantic Ocean about east off the coast of the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo, of which it forms a part. The archipelago has a total area of and a navy-supported research ...

islands, where they began to catch more favorable prevailing westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes (about ...

. These would take them quickly straight east, across the South Atlantic, to South Africa.

The Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

–once aptly named the "cape of storms"–was a very challenging headland on the India Run. The outbound crossing was always difficult, and many a ship was lost here. Larger armadas often broke up into smaller squadrons to attempt the crossing, and would re-collect only on the other side – indeed quite far on the other side. There was usually no stop or collection point after the Cape crossing until well inside the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

. The reason for this is that outbound ships tried to steer clear from the South African coast, to avoid the rushing waters of the contrary Agulhas Current.

The exception was the (Mossel Bay

Mossel Bay () is a harbour town of about 170,000 people on the Garden Route of South Africa. It is an important tourism and farming region of the Western Cape Province. Mossel Bay lies 400 kilometres east of the country's seat of parliament, Ca ...

, South Africa), a watering stop after the Cape. It was not always used on the outbound journey since individual ships often charted wide routes around the Cape, and sighted coast again only well after this point. However, ships damaged during the crossing frequently had no choice but to put in there for emergency repairs. Trade for food supplies with the pastoral Khoikhoi

Khoikhoi (Help:IPA/English, /ˈkɔɪkɔɪ/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''KOY-koy'') (or Khoekhoe in Namibian orthography) are the traditionally Nomad, nomadic pastoralist Indigenous peoples, indigenous population of South Africa. They ...

peoples that lived in the area was frequent (although there were also occasional skirmishes). São Brás was a more frequent stop on the return journey, as a place to repair the ships before doubling the Cape the other way. As a result, particularly in early years, São Brás was used as a postal station, where messages from the returning armadas would be left for the outward armadas, reporting on the latest conditions in India.

If the armada went by the inner route, then the next daunting obstacle was Cape Correntes

Cape Correntes (sometimes also called "Cape Corrientes" in English) ( Port.: "Cabo das Correntes") is a cape or headland in the Inhambane Province in Mozambique. It sits at the southern entry of the Mozambique Channel.•

Cape Correntes wa ...

, at the entrance of the Mozambique Channel. Treacherously fast waters, light winds alternating with unpredictably violent gusts, and dangerous shoals and rocks made this cape particularly dangerous. It is estimated that of all the ships lost on the India Run, nearly 30% of them capsized or ran aground around here - more than any other place.

The ideal passage through the Mozambique Channel would be to sail straight north through the middle of the channel, where a steady favorable wind could be relied upon at this season, but this was a particularly hard task in an era where longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

was determined largely by dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

. If a pilot miscalculated and charted a course too close to the African coast, the current ran south, the winds were light or non-existent, subject to arbitrary gusts from strange directions, and the coasts were littered with shoals

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body of water close to the surface or ...

.Indeed, another reason ships steered clear away from the South African coast after crossing the Cape of Good Hope was precisely that the contrary Agulhas current threw off the dead reckoning calculations, and often misled pilots into turning too soon into the Mozambique channel, forcing them on a dangerous too-western route up the channel. Into this dreaded mix, Cape Correntes added its own special terror to the experience. The Cape was not only a confluence point of opposing winds, which created unpredictable whirlwinds, it also produced a strange and extraordinarily fast southerly current, violent enough to break a badly-sewn ship, and confusing enough to throw all reckoning out the window and lure pilots into grievous errors.

The temptation would be to err in the opposite direction, and keep on pushing east until the island of Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

was sighted, then move up the channel (the current here ran north), keeping the Madagascar coast in sight at all times. Although a Madagascar-hugging route cleared up the longitude problem, it was also abundant in fearful obstacles – coral islets, atolls, shoals, protruding rocks, submerged reefs, made for a particularly nerve-wracking experience to navigate, especially at night or in bad weather.

To avoid the worst consequences of doubling Cape Correntes, India ships stayed as far from the African coast as possible but not so close to Madagascar to run into its traps. To find the ideal middle route through the channel, pilots tended to rely on two dangerous longitude markers – the Bassas da India

Bassas da India (; ) is an uninhabited, roughly circular atoll located in the southern Mozambique Channel, about halfway between Mozambique and Madagascar (about further east) and around northwest of Europa Island. It is administered by F ...

and the Europa rocks. Although conveniently situated in the middle of the channel, they were not always visible above the waves, so sailors often watched for hovering clusters of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

s, which colonized these rocks, as an indicator of their location. Unfortunately, this was not a reliable method, and many an India ship ended up crashing on those rocks.

If they succeeded sailing up the middle channel, the India naus usually saw African coast again only around the bend of Angoche

Angoche is a district, city and municipality located in Nampula Province in north-eastern Mozambique. The district has limits in the North with Mogincual District, in the South with Larde District, to the east with the Indian Ocean and to the west ...

. If the ships were in a bad shape, they could stop at the Primeiras Islands (off Angoche) for urgent repairs. The Primeiras are a long row of uninhabited low coral islets – not much more than mounds above the waves – but they form a channel of calm waters between themselves and the mainland, a useful shelter for troubled ships.

The scheduled stop was a little further north on Mozambique Island, a coral island off the coast, with two outlying smaller islands ( Goa Island, known as ''São Jorge'', and the island of Sena). Mozambique's main attribute was its splendid harbor, which served as the usual first stop and collection point of Portuguese India armadas after the crossing of the Cape of Good Hope. The island had a town and a fortress, so some stock of supplies was usually at hand.

The conditions of the ships by the time they reached Mozambique was often woeful. With the occasional exception of Cape Santo Agostinho and Mossel Bay, there were no stops between Cape Verde and Mozambique Island, an extraordinarily long time for 16th-century ships to remain at sea without repairs, watering, or resupply. Already before the Cape, provisions had grown stale, scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease (state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum d ...

and dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

had often set in, and deaths of crews and passengers from disease had begun. The ship itself, so long at sea without re-caulking or re-painting, was in a fragile state. To then force the miserable ship through the mast-cracking tempests of Cape of Good Hope, the seam-ripping violent waters of Cape Correntes and the treacherous rocks of the channel, turned this final stage into a veritable hell for all aboard.

Mozambique Island was originally an outpost of the Kilwa Sultanate

The Kilwa Sultanate was a sultanate, centered at Kilwa (an island off modern-day, Kilwa District in Lindi Region of Tanzania), whose authority, at its height, stretched over the entire length of the Swahili Coast. According to the legend, it wa ...

, a collection of Muslim Swahili cities along the East African coast, centered at Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani ('Kilwa Island') is an island, national historic site, and Hamlet (place), hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region, Lindi in southern Ta ...

, that formed a medieval commercial empire from Cape Correntes in the south to the Somali borderlands in the north, what is sometimes called the "Swahili Coast

The Swahili coast () is a coastal area of East Africa, bordered by the Indian Ocean and inhabited by the Swahili people. It includes Sofala (located in Mozambique); Mombasa, Gede, Kenya, Gede, Pate Island, Lamu, and Malindi (in Kenya); and Dar es ...

". The Kilwa Sultanate began disintegrating into independent city-states around the time of the Portuguese arrival (1500), a process speeded along by the intrigues and interventions of Portuguese captains.

The original object of Portuguese attentions had been the southerly Swahili city of Sofala

Sofala , at present known as Nova Sofala , used to be the chief seaport of the Mwenemutapa Kingdom, whose capital was at Mount Fura. It is located on the Sofala Bank in Sofala Province of Mozambique. The first recorded use of this port town w ...

, the main outlet of the Monomatapa gold trade, and the first Portuguese fortress in East Africa was erected there in 1505 ( Fort São Caetano de Sofala). But Sofala's harbor was marred by a long moving sandbank and hazardous shoals, making it quite unsuitable as a stop for the India armadas. So in 1507, the 9th Portuguese India Armada (Mello, 1507) seized Mozambique Island and erected a fortress there (Fort São Gabriel, later replaced by Fort São Sebastião in 1558), to use its spacious and well-sheltered harbor.

The principal drawback was that Mozambique Island was parched and infertile. It produced practically nothing locally, and even had to ferry drinkable water by boat from elsewhere. Replenishing the islands was not a simple matter. Although Mozambique islanders had established watering holes, gardens and coconut palm groves (essential for timber) just across on the mainland (at ''Cabaceira'' inlet), the Bantu inhabitants of the area were generally hostile to both the Swahili and the Portuguese, and often prevented the collection of supplies. So ensuring Mozambique had sufficient supplies presented its own challenges. The Portuguese factor

Factor (Latin, ) may refer to:

Commerce

* Factor (agent), a person who acts for, notably a mercantile and colonial agent

* Factor (Scotland), a person or firm managing a Scottish estate

* Factors of production, such a factor is a resource used ...

s in Mozambique had to ensure enough supplies were shipped in from other points on the East African coast to Mozambique Island before the armada's scheduled arrival. The Mozambican factor also collected East African trade goods that could be picked up by the armadas and sold profitably in Indian markets – notably gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

, ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

, pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living Exoskeleton, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pear ...

s and coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

.

After Mozambique, the rule for the India armadas was generally to continue sailing north until they reached the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

latitude (the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (; Seychellois Creole: ), is an island country and archipelagic state consisting of 155 islands (as per the Constitution) in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, Victoria, ...

islands, at 4ºS, were a common reference point). It was around here that the all-important southwesterly monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

winds began to pick up. The armada would then sail east, and let the monsoon carry them headlong across the Indian Ocean until India, presuming the armada arrived at the equator sometime in August.

In Pimentel's (1746) estimation, ships had to leave Mozambique before August 25 to avail themselves of the summer monsoon. If, however, the armada arrived in the latter part of the season, say September, turning at the equator was a risky route. The southwesterly monsoon might be blowing in the right direction at the moment, but the ship ran the risk of not reaching a safe Indian port before the monsoon reversed direction (usually around late September to early October, when it became a northeasterly). So a late season ship was usually stuck in Africa until next April.

Notice that the trajectory, as described, skips over nearly all the towns on the East African coast north of Mozambique – Kilwa

Kilwa Kisiwani ('Kilwa Island') is an island, national historic site, and Hamlet (place), hamlet community located in the township of Kilwa Masoko, the district seat of Kilwa District in the Tanzanian region of Lindi Region, Lindi in southern Ta ...

(''Quíloa''), Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

, Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

(''Mombaça''), Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

(''Melinde''), Barawa

Barawa ( ''Barāwe'', , ''Baraawe'', ''Barāwa'', Italian language, Italian: ''Brava''), also known as Barawe and Brava, is the capital city, capital of the South West State of Somalia, South West State of Somalia.Pelizzari, Elisa. "Guerre civ ...

(''Brava''), Mogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

(''Magadoxo''), etc. This is not to say Portuguese did not visit those locations – indeed, some even had Portuguese factories and forts (e.g. Fort Santiago in Kilwa, held from 1505 to 1512). But Portuguese armadas on their way to India did not have to stop at those locations, and so usually did not. The stop on Mozambique island was usually the only necessary one.

Nonetheless, if the armada had time, or got into trouble for some reason, the stopping choice was

Nonetheless, if the armada had time, or got into trouble for some reason, the stopping choice was Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

. A Portuguese ally since the earliest trip of Vasco da Gama in 1498, Malindi could usually be counted on to give a warm reception and had plenty of supplies. Unlike most other Swahili towns, Malindi was on the mainland and had an ample hinterlands with fertile cultivated fields, including groves of oranges and lemons (critical to combat scurvy). However, it had a poor harbor; although waters were kept calm by an offshore reef, the anchorage area was littered with shoals. It did, however, have a peculiar protruding rock that served as a decent natural pier

A pier is a raised structure that rises above a body of water and usually juts out from its shore, typically supported by piling, piles or column, pillars, and provides above-water access to offshore areas. Frequent pier uses include fishing, b ...

for loading and unloading goods.

Malindi's other advantage was that, at 3º15'S, it was practically at exactly the right latitude to catch the southwesterly monsoon for an Indian Ocean crossing. Plenty of experienced Indian Ocean pilots – Swahili, Arab or Gujarati – could be found in the city, and Malindi was likely to have the latest news from across the sea, so it was a very convenient stop for the Portuguese before a crossing. However, stops take time, which, given the imminent monsoon reversal, was a scarce commodity. If the armada had been decently equipped enough at Mozambique island, a stop at Malindi, however delightful or useful, was an unnecessary and risky expenditure of time.

With the monsoon, Portuguese India armadas usually arrived in India in early September (sometimes late August). Because of the wind pattern, they usually made landfall around Anjediva island (''Angediva''). From there, the armada furled their square sails and proceed with lateen sails south along the Malabar coast of India to the city of Cochin

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernaku ...

(''Cochim'', Kochi) in Kerala

Kerala ( , ) is a States and union territories of India, state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile ...

. Cochin was the principal spice port accessible to the Portuguese, it had the earliest Portuguese factory and fort in India, and served as the headquarters of Portuguese government and operations in India for the first decades. However, this changed after the Portuguese conquest of Goa

The Portuguese conquest of Goa occurred when the governor Afonso de Albuquerque captured the city in 1510 from the Sultanate of Bijapur. Old Goa became the capital of Portuguese India, which included territories such as Fort Manuel of Cochin, ...

in 1510. The capture of Goa had been largely motivated by the desire to find a replacement for Anjediva as the first anchoring point for the armadas. Anjediva had proven itself to be far from ideal. The island was generally undersupplied – it contained only a few fishing villages – but the armada ships were often forced to sojourn there for long periods, usually for repair or to await for better winds to carry them down to Cochin. Anjediva island also lay in precarious pirate-infested waters, on the warring frontier between Muslim Bijapur and Hindu Vijaynagar, which frequently threatened it. The same winds which carried the armada down to Cochin prevented Portuguese squads from Cochin racing up to rescue it. The Portuguese had tried setting up a fort in Anjediva, but it was captured and dismantled by forces on behalf of Bijapur. As a result, the Portuguese governor Afonso de Albuquerque

Afonso de Albuquerque, 1st Duke of Goa ( – 16 December 1515), was a Portuguese general, admiral, statesman and ''conquistador''. He served as viceroy of Portuguese India from 1509 to 1515, during which he expanded Portuguese influence across ...

decided the nearby island-city of Goa

Goa (; ; ) is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is bound by the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north, and Karnataka to the ...

was preferable and forcibly seized it in 1510. Thereafter Goa, with its better harbor and greater supply base, served as the first anchorage point of Portuguese armadas upon arriving in India. Although Cochin, with its important spice markets, remained the ultimate destination, and was still the official Portuguese headquarters in India until the 1530s, Goa was more favorably located relative to Indian Ocean wind patterns and served as its military-naval center. The docks of Goa were soon producing their own carracks for the India run back to Portugal and for runs to further points east.

Return voyage

The return voyage was shorter than the outbound. The fleet left India in December, picking up thenortheast monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscill ...

towards the African coast. Passing through the Mozambique Channel, the fleet kept close to land to avoid the westerlies and catch the Agulhas Current to round the Cape of Good Hope. Once in the Atlantic, it caught the southeast trade winds and sailed to the west of Ascension and Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

as far as the doldrums. The fleet then sailed almost straight north to the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

, where it caught the prevailing westerlies and sailed due east into Lisbon.

Logistics of the Armadas

Organization

The size of the armada varied, from enormous fleets of over twenty ships to small ones of as few as four. This changed over time. In the first decade (1500–1510), when the Portuguese were establishing themselves in India, the armadas averaged around fifteen ships per year. This declined to around ten from 1510–1525. From 1526 to the 1540s, the armadas declined further to 7-8 ships per year — with a few exceptional cases of large armadas (e.g. 1533, 1537, 1547) brought about by military exigency, but also several years of exceptionally small fleets. In the second half of the 16th century, the Portuguese India armada stabilized at 5-6 ships annually, with very few exceptions (above seven in 1551 and 1590, below 4 in 1594 and 1597).Guinote (1999) Organization was principally in the hands of theCasa da Índia

The Casa da Índia (; English language, English: ''India House'' or ''House of India'') was a Portuguese state-run enterprise, state-run commercial organization during the Age of Discovery. It regulated international trade and the Portuguese Emp ...

, the royal trading house established around 1500 by King Manuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate (), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portugal, as monarch. Manu ...

. The Casa was in charge of monitoring the crown monopoly on India trade – receiving goods, collecting duties

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; , past participle of ; , whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may arise from a system of ethics or morality, e ...

, assembling, maintaining and scheduling the fleets, contracting private merchants, correspondence with the ''feitorias'' (overseas factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. Th ...

), drafting documents and handling legal matters.

Separately from the Casa, but working in coordination with it, was the ''Armazém das Índias'', the royal agency in charge of nautical outfitting, that oversaw the Lisbon docks and naval arsenal. The Armazém was responsible for the training of pilots and sailors, ship construction and repair, and the procurement and provision of naval equipment – sails, ropes, guns, instruments and, most importantly, maps. The ''piloto-mor'' ('chief pilot') of the Armazém, in charge of pilot-training, was, up until 1548, also the keeper of the '' Padrão Real'', the secret royal master map, incorporating all the cartographic details reported by Portuguese captains and explorers, and upon which all official nautical charts were based. The screening and hiring of crews was the function of the ''provedor'' of the Armazém.

From at least 1511 (perhaps earlier), the offices of the Casa da India were based in the ground floor of the royal Ribeira Palace, by the Terreiro do Paço in Lisbon, with the Armazém nearby. (Neither the Casa nor the Armazem should be confused with the Estado da Índia

The State of India, also known as the Portuguese State of India or Portuguese India, was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded seven years after the discovery of the sea route to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama, a subject of the ...

, the Portuguese colonial government in India, which was separate and reported directly to the monarch.)

Ships could be and sometimes were owned and outfitted by private merchants, and these were incorporated into the India armada. However, the expenses of outfitting a ship were immense, and few native Portuguese merchants had the wherewithal to finance one, despite eager government encouragement. In the early India runs, there are several ships organized by private consortiums, often with foreign capital provided by wealthy Italian and German trading houses. This fluctuated over time, as the royal duties, costs of outfitting and rate of attrition and risk of loss on India runs were sometimes too high for private houses to bear. Private Portuguese merchants did, however, routinely contract for cargo, carried aboard crown ships for freight charges.

Marine insurance

Marine insurance covers the physical loss or damage of ships, cargo, terminals, and any transport by which the property is transferred, acquired, or held between the points of origin and the final destination. Cargo insurance a sub-branch of mari ...

was still underdeveloped, although the Portuguese had helped pioneer its development and its practice seemed already customary.In May, 1293, King Denis of Portugal

Denis (, ; 9 October 1261 – 7 January 1325), called the Farmer King (''Rei Lavrador'') and the Poet King (''Rei Poeta''), was King of Portugal from 1279 until his death in 1325.

Dinis was the eldest son of Afonso III of Portugal by his second ...

had established the ''Sociedade de Mercadores Portugueses'' (Society of Portuguese Merchants), with mutual help clauses that formed the kernel of marine insurance contracts, similar to those in practice in Italian ports such as Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

and Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

. In 1380 Ferdinand I established a shipping company ('' Companhia das Naus''), with a compulsory insurance scheme, whereby member-merchants (essentially all shipowners and merchants outfitting ships above 50t) to contribute a fixed rate of 2% of freight revenue as a premium to a central fund (''Bolsa de Seguros''), from which claim payouts would be redistributed. Around 1488, Pedro de Santarém

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

(''Petrus Santerna''), a Portuguese consul in Italy, wrote perhaps the first treatise, ''De assecurationibus'' (published 1552–53), outlining the theory and principles behind marine insurance. Around 1578, Cardinal-King Henry established the ''Consulado'', a tribunal explicitly dedicated to decide marine insurance cases (initially suppressed by the Iberian Union

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the period in which the Habsburg Spain, Monarchy of Spain under Habsburg dynasty, until then the personal union of the crowns of Crown of Castile, Castile and Crown of Aragon, Aragon ...

of 1580, the tribunal was resurrected by Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

in 1593, with the modification that a private marine insurance contract had to have the signature of a royal official (''comissário de seguros''), to be valid in the law courts). This formed the framework for marine insurance in which the India Armadas operated. Later developments include the establishment of an insurance house (''Casa de Seguros'') as an organ of the ''Junta do Comércio Geral'' (Board of General Trade) by regent-prince Peter II of Portugal

'' Dom'' Pedro II (Peter II; 26 April 1648 – 9 December 1706), nicknamed the Pacific (''Português:'' O Pacífico) was King of Portugal from 1683 until his death, previously serving as regent for his brother Afonso VI from 1668 until his own ...

in 1668, subsequently replaced by the ''Mesa do Bem Comum do Comércio (''Board of Common Trade Welfare) in 1720. Around 1750, the Marquis de Pombal persuaded the monarch to fold the older house into a new entity, the ''Real Junta do Comércio'' (Royal Board of Trade). (DeSouza, 1977).

Ships

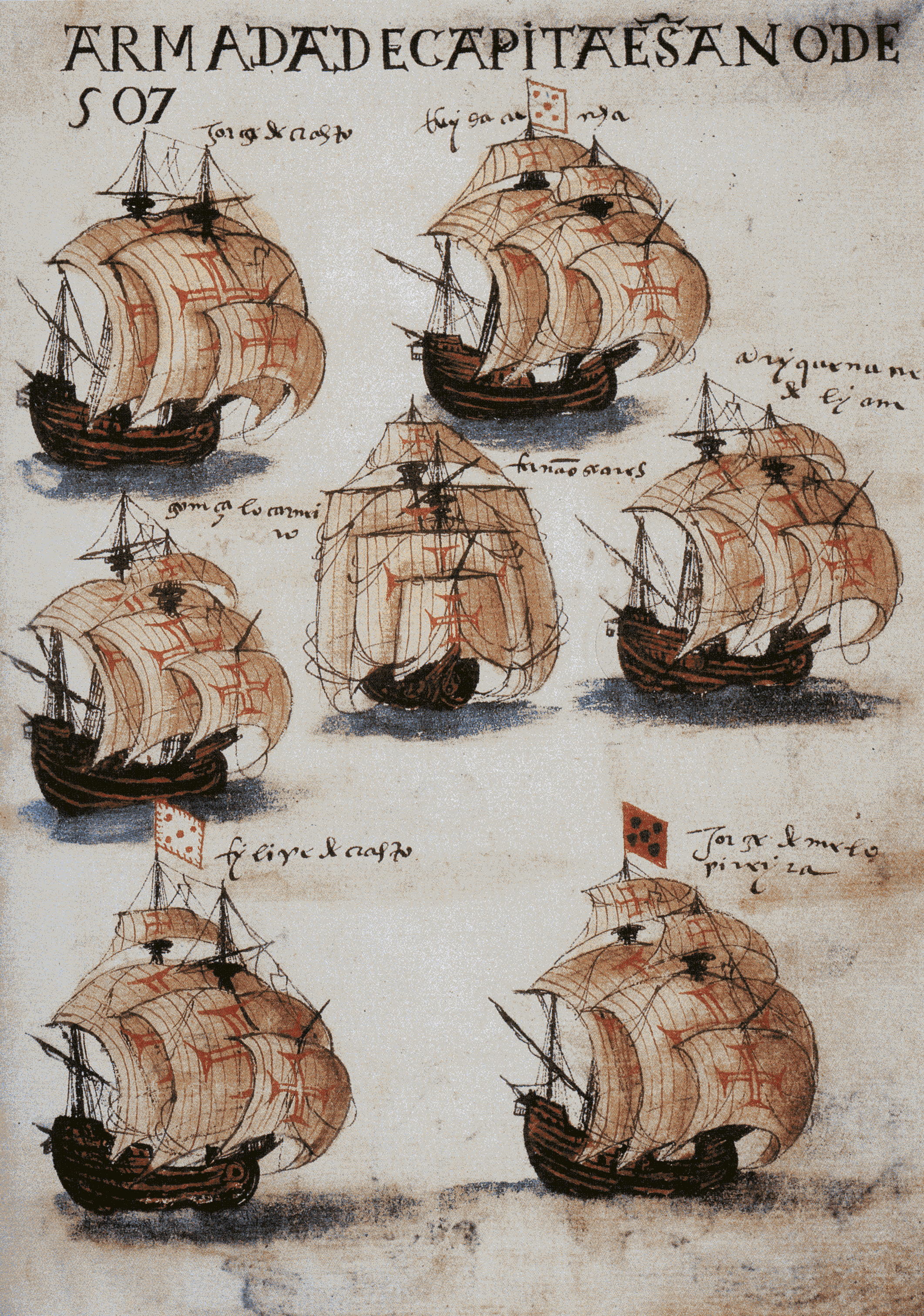

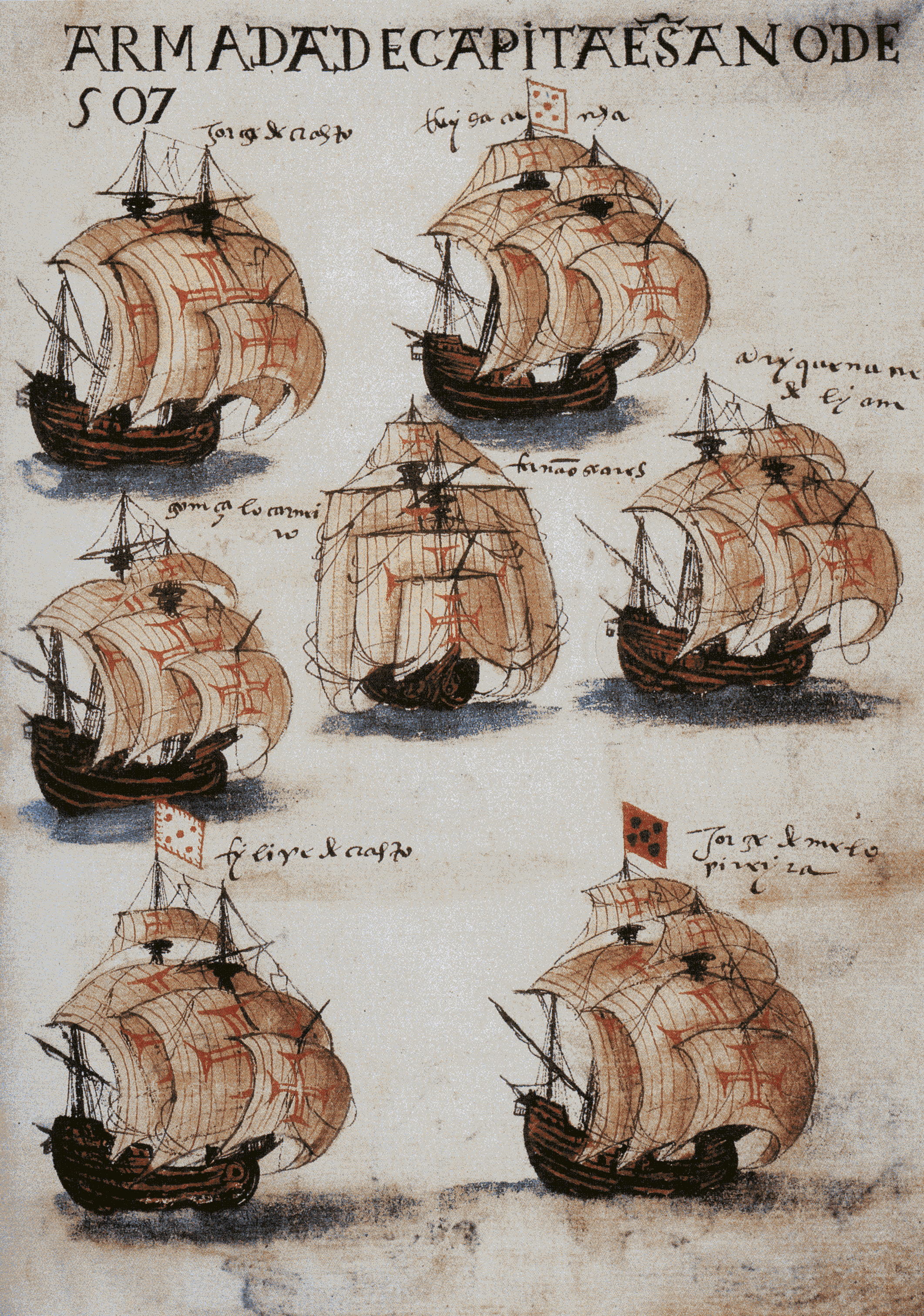

The ships of an India armada were typically

The ships of an India armada were typically carracks

A carrack (; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for Europea ...

(''naus''), with sizes that grew over time. The first carracks were modest ships, rarely exceeding 100 tons, carrying only up to 40–60 men; for example, the ''São Gabriel'' of Gama's 1497 fleet, one of the largest of the time, was only 120 tons. But this was quickly increased as the India run got underway. In the 1500 Cabral armada, the largest carracks, Cabral's flagship and the ''El-Rei'', are reported to have been somewhere between 240 and 300 tons. The '' Flor de la Mar'', built in 1502, was a 400-ton nau, while at least one of the naus of the Albuquerque

Albuquerque ( ; ), also known as ABQ, Burque, the Duke City, and in the past 'the Q', is the List of municipalities in New Mexico, most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico, and the county seat of Bernalillo County, New Mexico, Bernal ...

armada of 1503 is reported to have been as large as 600 tons. The rapid doubling and tripling of the size of Portuguese carracks in a few years reflected the needs of the India runs. The rate of increase tapered off thereafter. For much of the remainder of the 16th century, the average carrack on the India run was probably around 400 tons.

In the 1550s, during the reign of John III, a few 900-ton behemoths were built for India runs, in the hope that larger ships would provide economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of Productivity, output produced per unit of cost (production cost). A decrease in ...

. The experiment turned out poorly. Not only was the cost of outfitting such a large ship disproportionately high, they proved unmaneuverable and unseaworthy, particularly in the treacherous waters of the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

. Three of the new behemoths were quickly lost on the southern African coast – the ''São João'' (900 tons, built 1550, wrecked 1552), the ''São Bento'' (900 tons, built 1551, wrecked 1554) and the largest of them all, the ''Nossa Senhora da Graça'' (1,000 tons, built 1556, wrecked 1559).

These kind of losses prompted King Sebastian to issue an ordinance in 1570 setting the upper limit to the size of India naus at 450 tons. Nonetheless, after the Iberian Union

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the period in which the Habsburg Spain, Monarchy of Spain under Habsburg dynasty, until then the personal union of the crowns of Crown of Castile, Castile and Crown of Aragon, Aragon ...

of 1580, this regulation would be ignored and shipbuilders, probably urged on by merchants hoping to turn around more cargo on every trip, pushed for larger ships. The size of India naus accelerated again, averaging 600 tons in the 1580–1600 period, with several spectacularly large naus of 1500 tons or greater making their appearance in the 1590s.

If the lesson was not quite learned then, it was certainly learned in August, 1592, when English privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

Sir John Burroughs (alt. Burrows, Burgh) captured the ''Madre de Deus

''Madre de Deus'' (''Mother of God''; also called ''Mãe de Deus'' and ''Madre de Dios'', referring to Mary) was a Portuguese ocean-going carrack, renowned for her capacious cargo and provisions for long voyages. She was returning from her ...

'' in the waters around the Azores

The Azores ( , , ; , ), officially the Autonomous Region of the Azores (), is one of the two autonomous regions of Portugal (along with Madeira). It is an archipelago composed of nine volcanic islands in the Macaronesia region of the North Atl ...

islands (see Battle of Flores). The ''Madre de Deus'', built in 1589, was a 1600-ton carrack, with seven decks and a crew of around 600. It was the largest Portuguese ship to go on an India run. The great carrack, under the command of Fernão de Mendonça Furtado, was returning from Cochin

Kochi ( , ), formerly known as Cochin ( ), is a major port city along the Malabar Coast of India bordering the Laccadive Sea. It is part of the district of Ernakulam in the state of Kerala. The city is also commonly referred to as Ernaku ...

with a full cargo when it was captured by Burrough. The value of the treasure and cargo taken on this single ship is estimated to have been equivalent to half the entire treasury of the English crown. The loss of so much cargo in one swoop confirmed, once again, the folly of building such gigantic ships. The carracks built for the India run returned to their smaller size after the turn of the century.

In the early ''Carreira da India'', the carracks were usually accompanied by smaller caravels (''caravelas''), averaging 50–70 tons (rarely reaching 100), and capable of holding 20–30 men at most. Whether lateen-rigged (') or square-rigged

Square rig is a generic type of sail and rigging arrangement in which a sailing vessel's primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spars that are perpendicular (or square) to the median plane of the keel and masts of the vessel. These sp ...

(''redonda

Redonda is an List of uninhabited regions, uninhabited Caribbean island which is a dependency of Saint John, Antigua and Barbuda, in the Leeward Islands, West Indies. The island is about long, wide, and is high at its highest point.

It lie ...

''), these shallow-drafted, nimble vessels had a myriad of uses. Caravels served as forward lamp, scouts and fighting ships of the convoy. Caravels on the India run were often destined to remain overseas for coastal patrol duty, rather than return with the main fleet.

In the course of the 16th century, caravels were gradually phased out in favor of a new escort/fighting ship, the galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships developed in Spain and Portugal.

They were first used as armed cargo carriers by Europe, Europeans from the 16th to 18th centuries during the Age of Sail, and they were the principal vessels dr ...

(''galeão''), which could range anywhere between 100 and 1000 tons. Based on the design of the carrack

A carrack (; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal and Spain. Evolving from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for Europea ...

, but slenderer and lower, with forecastle diminished or removed to make way for its famous 'beak', the galleon became the principal fighting ship of the India fleet. It was not as nimble as the caravel, but could be mounted with much more cannon. With the introduction of the galleon, carracks became almost exclusively cargo ships (which is why they were pushed to such large sizes), leaving any fighting to be done to the galleons. One of the largest and most famous of Portuguese galleons was the '' São João Baptista'' (nicknamed ''Botafogo'', 'spitfire'), a 1,000-ton galleon built in 1534, said to have carried 366 guns.

Many fleets also brought small supply ships on outward voyage. These were destined to be scuttled along the way once the supplies were consumed. The crews were redistributed and the abandoned ships usually burned to recover their iron nails and fittings.

The average speed of an India Armada was around 2.5 knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot or knots may also refer to:

Other common meanings

* Knot (unit), of speed

* Knot (wood), a timber imperfection

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Knots'' (film), a 2004 film

* ''Kn ...

, but some ships could achieve speeds of between 8 and 10 for some stretches.

Seaworthiness

Portuguese India ships distinguished themselves from the ships of other navies (especially those of rival powers in the Indian Ocean) on two principal accounts: their seaworthiness (durability at sea) and their artillery. With a few exceptions (e.g. '' Flor de la Mar'', ''Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai

''Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai'' was a higher-castled Portuguese carrack with 140 guns, launched down in 1520 (800 t, length 38 m, width 13 m, draft 4–4.5 m). Built in Kochi, India around 1512 it had two square rig masts and is depicted on a ...

''), Portuguese India naus were not typically built to last longer than four or five years of useful service. That a nau managed to survive a single India run was already an achievement, given that few ships of any nation at the time were able to stay at sea for even a quarter as long without breaking apart at the seams.