The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous

military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from th ...

in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, ran from 1939 to the

defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the

naval history of World War II

At the start of World War II, the Royal Navy was the strongest navy in the world, with the largest number of warships built and with naval bases across the globe. It had over 15 battleships and battlecruisers, 7 aircraft carriers, 66 cruisers, 16 ...

. At its core was the

Allied naval

blockade of Germany Blockade of Germany may refer to:

*Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)

The Blockade of Germany, or the Blockade of Europe, occurred from 1914 to 1919. The prolonged naval blockade was conducted by the Allies of World War I, Allies during and afte ...

, announced the day after the declaration of war, and Germany's subsequent counter-blockade. The campaign peaked from mid-1940 to the end of 1943.

The Battle of the Atlantic pitted

U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

s and other warships of the German (navy) and aircraft of the (air force) against the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

,

Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; , ''MRC'') is the Navy, naval force of Canada. The navy is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of February 2024, the RCN operates 12 s, 12 s, 4 s, 4 s, 8 s, and several auxiliary ...

,

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, and

Allied merchant shipping.

Convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s, coming mainly from North America and predominantly going to the United Kingdom and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, were protected for the most part by the British and Canadian navies and air forces. These forces were aided by ships and aircraft of the United States beginning on 13 September 1941.

[ Carney, Robert B., Admiral, USN. "Comment and Discussion" ''United States Naval Institute Proceedings'' January 1976, p. 74] The Germans were joined by

submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s of the Italian (royal navy) after Germany's

Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

ally Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940.

As an island country, the United Kingdom was highly dependent on imported goods. Britain required more than a million tons of imported material per week in order to survive and fight. The Battle of the Atlantic involved a

tonnage war

A tonnage war is a military strategy aimed at merchant shipping. The premise is that the enemy has a finite number of ships and a finite capacity to build replacements. The concept was made famous by German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, who wrote: ...

: the Allied struggle to supply Britain while the Axis targeted merchant shipping critical to the British war effort.

Rationing in the United Kingdom

Rationing was introduced temporarily by the British government several times during the 20th century, during and immediately after a war.

At the start of the Second World War in 1939, the United Kingdom was importing 20 million long tons ...

was also used with the aim of reducing demand, by reducing wastage and increasing domestic production and equality of distribution. From 1942 onwards, the Axis also sought to prevent the build-up of Allied supplies and equipment in the UK in preparation for the

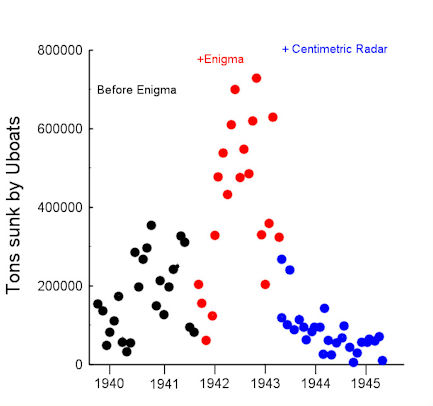

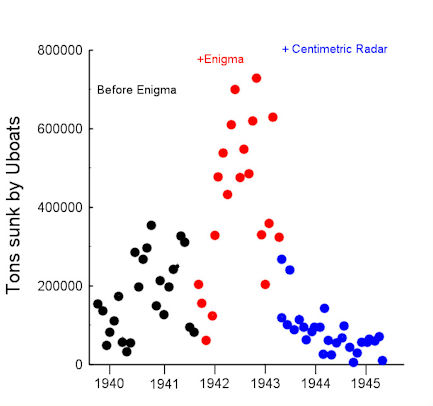

invasion of occupied Europe. The defeat of the U-boat threat was a prerequisite for pushing back the Axis in western Europe. The outcome of the battle was a strategic victory for the Allies—the German tonnage war failed—but at great cost: 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships were sunk in the Atlantic for the loss of 783 U-boats and 47 German surface warships, including 4 battleships (, , , and ), 9 cruisers, 7 raiders, and 27 destroyers. This front was a main consumer of the German war effort: Germany spent more money to produce naval vessels than every type of ground vehicle combined, including tanks.

Although the GRT (gross registered tonnage) was used by all engaged in the “tonnage war,” the values, recorded as GRT or sometimes “tons,” should not be confused with the weight of the cargo a ship might have carried. GRT is a volume, 100 cubic feet per “ton”, not a weight.

[Simplified Measurement, US Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, Tonnage Guide 1, CH-3, March 24, 2022 p3ff] A ton of water, for example, has a volume of 32 cubic feet. A load of 2,125 tons of water would have occupied 1,000 "tons" of a ship’s total GRT (100,000 cubic feet). During the Second World War the term GRT included almost all of the enclosed space. In addition, the Germans attributed GRTs sunk to passenger, troop ships and warships regardless of their actual cargo. Thus, measurements of GRT sunk each month had no relationship to shipments and was not limited to merchant freighters.

The Battle of the Atlantic has been called the "longest, largest, and most complex" naval battle in history. Starting immediately after the European war began, during the

Phoney War

The Phoney War (; ; ) was an eight-month period at the outset of World War II during which there were virtually no Allied military land operations on the Western Front from roughly September 1939 to May 1940. World War II began on 3 Septembe ...

, the Battle lasted over five years before the

German surrender

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ger ...

in May 1945. It involved thousands of ships in a theatre covering millions of square miles of ocean. The situation changed constantly, with one side or the other gaining advantage, as participating countries surrendered, joined and even changed sides in the war, and as new weapons, tactics, counter-measures and equipment were developed. The Allies gradually gained the upper hand, overcoming German surface-raiders by the end of 1942 and defeating the U-boats by mid-1943, though losses due to U-boats continued until the war's end. British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

later wrote, "The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril. I was even more anxious about this battle than I had been about the glorious air fight called the '

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain () was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended the United Kingdom (UK) against large-scale attacks by Nazi Germany's air force ...

'."

Name

On 5 March 1941, the

First Lord of the Admiralty

First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the title of the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible f ...

,

A. V. Alexander, asked

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

for "many more ships and great numbers of men" to fight "the Battle of the Atlantic", which he compared to the

Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

fought the previous summer. The first meeting of the

Cabinet's "Battle of the Atlantic Committee" was on 19 March. Churchill claimed to have coined the phrase "Battle of the Atlantic" shortly before Alexander's speech, but there are several examples of earlier usage.

Background

Following the use of

unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning. The use of unrestricted submarine warfare has had significant impacts on international relations in ...

by Germany in the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, countries tried to limit or abolish submarines. The effort failed. Instead, the

London Naval Treaty

The London Naval Treaty, officially the Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament, was an agreement between the United Kingdom, Empire of Japan, Japan, French Third Republic, France, Kingdom of Italy, Italy, and the United Stat ...

required submarines to abide by "

cruiser rules", which demanded they surface, search and place ship crews in "a place of safety" (for which lifeboats did not qualify, except under particular circumstances) before sinking them, unless the ship in question showed "persistent refusal to stop...or active resistance to visit or search". These regulations did not prohibit arming merchantmen, but doing so, or having them report contact with submarines (or

raiders), made them ''de facto'' naval auxiliaries and removed the protection of the cruiser rules.

The

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace ...

forbade the Germans to operate U-boats and reduced the German surface fleet to a few obsolete ships. When three of these obsolete ships had to be replaced, the Germans opted to construct the

Deutschland-class of (armoured ships) or "pocket battleships" as they were nicknamed by foreign navies. These ships were designed for commerce raiding on distant seas, to operate as a raider hunting for independently sailing ships, and to avoid combat with superior forces.

The

Anglo-German Naval Agreement

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the ''Kriegsmarine'' in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio where ...

of 1935 allowed Hitler to renounce the Treaty of Versailles, and to build a fleet 35% the size of Britain's. A building programme for four battleships, two aircraft carriers, five heavy cruisers, destroyers and U-boats was immediately initiated. After the agreement, Hitler thought conflict with the UK very unlikely; consequently, the fleet was designed for commerce raiding against the French, not to challenge command of the sea. The commander of the German U-boats, Karl Dönitz, had his own opinions. In contrast with Hitler and

Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II and was convicted of war crimes after the war. He attained the highest possible naval rank, that of ...

, chief of the German navy, he considered war with the UK inevitable and that a large surface fleet was not needed, believing U-boats could defeat the British. According to his calculations, a fleet of 300 medium

Type VII

Type VII U-boats were the most common type of German World War II U-boat. 704 boats were built by the end of the war. The type had several modifications. The Type VII was the most numerous U-boat type to be involved in the Battle of the Atlanti ...

U-boats could sink a million tons of ships a month and within a year sink enough of the about 3,000 British merchant ships (comprising 17.5 million tons) to strangle the British economy. In the First World War, U-boats had been defeated mainly by the

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

system, but Dönitz thought this could be overcome with the , wherein a patrol line of U-boats would search for a convoy before converging and attacking together at night from the surface. Neither aircraft nor early forms of

sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

(called ASDIC by the British) were then considered serious threats. ASDIC could not detect a surfaced submarine and its range was less than that of an

electric torpedo, aircraft could not operate at night and, during the day, an alert U-boat could dive before the aircraft attacked. Dönitz failed to persuade Raeder, so each time the U-boat fleet was expanded, Raeder opt to build a mix of coastal, medium and large submarines, even minelayers and U-cruisers. Even when in 1938 Hitler realised he would sooner or later have to oppose the UK and launched his

Plan Z

Plan Z was the re-equipment and expansion of the ''Kriegsmarine'' (German navy) ordered by Adolf Hitler in early 1939. The fleet was meant to challenge the naval power of the United Kingdom, and was to be completed by 1948. Development of the plan ...

, only a minority of the planned 239 U-boats were medium U-boats.

Anti-submarine warfare

With the introduction of ASDIC, the British Admiralty believed the submarine threat effectively neutralized. Consequently, the number of destroyers and convoy escorts was reduced and the anti-submarine branch seen as third rate. Destroyers were also equipped with ASDIC, but it was expected that these ships would be used in fleet actions rather than anti-submarine warfare, so they were not extensively trained in their use. Trials with ASDIC were usually conducted in ideal conditions and the Admiralty failed to appreciate ASDIC's flaws. Its range was limited, worked poorly at speeds above eight knots, was hampered by rough weather and required a very skilled operator to distinguish echoes from

thermocline

A thermocline (also known as the thermal layer or the metalimnion in lakes) is

a distinct layer based on temperature within a large body of fluid (e.g. water, as in an ocean or lake; or air, e.g. an atmosphere) with a high gradient of distinct te ...

s, whales, shoals of fish and wrecks. Early versions could not look directly down, so contact would be lost during the final stages of a depth charge attack. The basic set could detect range and bearing, but target depth could only be estimated from the range at which contact was lost.

An escort swept its ASDIC beam in an arc from one side of its course to the other, stopping the transducer every few degrees to send out a signal. On detection of a submarine, the escort would close in at moderate speed and increase its speed to attack. The intention was to pass over the submarine, rolling depth charges from chutes at the stern, while throwers fired further charges to either side, laying a pattern of depth charges. To disable a submarine, a depth charge had to explode within about . Since early ASDIC equipment was poor at determining depth, it was usual to vary the depth settings on part of the pattern.

As the threat of war loomed in early 1939, Britain realised it could not rely on the London Naval Treaty, which outlawed unrestricted submarine warfare. The organisational infrastructure for convoys had been maintained since World War I, with a thorough and systematic upgrade in the second half of the 1930s, but not enough escorts were available for convoy escorting, and a crash programme for building

Tree-class trawler

Tree-class trawlers were a class of anti-submarine naval trawlers which served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. They were nearly identical to the s, of which they are usually considered a subclass.

Six Tree-class trawlers were los ...

s,

Flower-class corvette

The Flower-class corvetteGardiner and Chesneau 1980, p. 62. (also referred to as the ''Gladiolus'' class after the lead ship) was a British class of 294 corvettes used during World War II by the Allied navies particularly as anti-submarine ...

s and

Hunt-class destroyer

The Hunt class was a class of escort destroyer of the Royal Navy. The first vessels were ordered early in 1939, and the class saw extensive service in the Second World War, particularly on the British east coast and Mediterranean convoys. Th ...

s was initiated. Merchant ships that were either too fast or too slow for convoys, were to be equipped with a

self-defence gun against surfaced submarine attacks, thus forcing an attacking U-boat to spend its precious torpedoes. This removed these ships from the protection of the cruiser rules under the

prize law

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements. .

Despite this lack of readiness, in 1939 the Royal Navy probably had as many ASDIC equipped warships in service as all the other navies of the world combined.

Similarly the role of aircraft had been neglected; the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

had organised a

Coastal Command

RAF Coastal Command was a formation within the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was founded in 1936, when the RAF was restructured into Fighter, Bomber and Coastal commands and played an important role during the Second World War. Maritime Aviation ...

to support the Royal Navy, but it possessed insufficient aircraft, had no long range aircraft nor were aircraft crew trained in anti-submarine warfare. The only weapon against submarines was inadequate bombs. Finally, it was not forgotten that in World War I, mines had sunk more U-boats than any other weapon. Plans were drafted for mine fields in the Channel and along the east coast in defence of shipping lanes, and also offensive mine barrages on the German U-boat lanes towards the Atlantic Ocean.

Early skirmishes (September 1939 – May 1940)

In 1939, the lacked the strength to challenge the combined British Royal Navy and

French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

() for command of the sea. Instead, German naval strategy relied on commerce raiding using

capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s,

armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

s, submarines and aircraft. Many German warships were already at sea when war was declared in September 1939, including most of the available U-boats and the "pocket battleships" and which had sortied into the Atlantic in August. These ships immediately attacked British and French shipping. sank the

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a type of passenger ship primarily used for transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships). The ...

within hours of the declaration of war—in breach of her orders not to sink passenger ships. The U-boat fleet, which was to dominate so much of the Battle of the Atlantic, was small at the beginning of the war; many of the 57 available U-boats were the small and short-range

Type IIs, useful primarily for

minelaying

A minelayer is any warship, submarine, military aircraft or land vehicle deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for ins ...

and operations in British coastal waters. Much of the early German anti-shipping activity involved minelaying by

destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s, aircraft and U-boats off British ports.

With the outbreak of war, the British and French immediately began a

blockade of Germany Blockade of Germany may refer to:

*Blockade of Germany (1914–1919)

The Blockade of Germany, or the Blockade of Europe, occurred from 1914 to 1919. The prolonged naval blockade was conducted by the Allies of World War I, Allies during and afte ...

, with little immediate effect on German industry. The Royal Navy quickly introduced a convoy system for the protection of trade that gradually extended out from the British Isles, eventually reaching as far as

Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

,

Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

and

Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

. Convoys allowed the Royal Navy to concentrate its escorts near the one place the U-boats were guaranteed to be found, the convoys. Each convoy consisted of between 30 and 70 mostly unarmed merchant ships.

Some British naval officials, particularly the First Lord of the Admiralty,

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, sought a more offensive strategy. The Royal Navy formed anti-submarine hunting groups based on

aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

s to patrol the shipping lanes in the

Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

and hunt for German U-boats. This strategy was deeply flawed because a U-boat, with its tiny silhouette, was likely to spot the surface warships and submerge long before it was sighted. The carrier aircraft were little help; although they could spot submarines on the surface, at this stage of the war they had no adequate weapons to attack them, and any submarine found by an aircraft was long gone by the time surface warships arrived. The hunting group strategy proved a disaster within days. On 14 September 1939, Britain's most modern carrier, , narrowly avoided being sunk when three torpedoes from exploded prematurely. ''U-39'' was forced to surface and scuttle by the escorting destroyers, becoming the first U-boat loss of the war. Another carrier, , was sunk three days later by .

German success in sinking ''Courageous'' was surpassed a month later when

Günther Prien

Günther Prien (16 January 1908 – presumed 8 March 1941) was a German U-boat commander during World War II. He was the first U-boat commander to receive the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and the first member of the ''Kriegsmarine'' to r ...

in penetrated the British base at

Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

and sank the old battleship at anchor immediately becoming a hero in Germany.

In the South Atlantic, British forces were stretched by the cruise of ''Admiral Graf Spee'', which sank nine merchant ships of in the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean during the first three months of war. The British and French formed hunting groups including three

battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s, three aircraft carriers, and 15 cruisers to seek the raider and her sister ''Deutschland'', which was operating in the North Atlantic. These hunting groups had no success until ''Admiral Graf Spee'' was

caught off the mouth of the River Plate between Argentina and Uruguay by an inferior British force. After suffering damage in the subsequent action, she took shelter in neutral

Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

harbour and was

scuttled

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vesse ...

on 17 December 1939.

After this initial burst of activity, the Atlantic campaign quietened. Admiral

Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German grand admiral and convicted war criminal who, following Adolf Hitler's Death of Adolf Hitler, suicide, succeeded him as head of state of Nazi Germany during the Second World ...

, commander of the U-boat fleet, had planned a maximum submarine effort for the first month of the war, with almost all the available U-boats out on patrol in September. That level of deployment could not be sustained; the boats needed to return to harbour to refuel, re-arm, re-stock supplies, and refit. The harsh winter of 1939–40 froze many of the Baltic ports, seriously hampering the German offensive by trapping several new U-boats in the ice.

Hitler's plans to invade Norway and Denmark in early 1940 led to the withdrawal of the fleet's surface warships and most of the ocean-going U-boats for fleet operations in

Operation Weserübung

Operation Weserübung ( , , 9 April – 10 June 1940) was the invasion of Denmark and Norway by Nazi Germany during World War II. It was the opening operation of the Norwegian Campaign.

In the early morning of 9 April 1940 (, "Weser Day"), Ge ...

.

The resulting

Norwegian campaign revealed serious flaws in the German U-boat

torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es: both the impact pistol and the

magnetic influence pistol (detonation mechanism) were defective, and the torpedoes did not run at the proper depth, often undershooting targets. Only one British warship was sunk by U-boats in more than 38 attacks. The news spread through the U-boat fleet and

undermined morale. Since the effectiveness of the magnetic pistol was already reduced by the

degaussing

Degaussing, or deperming, is the process of decreasing or eliminating a remnant magnetic field. It is named after the gauss, a unit of magnetism, which in turn was named after Carl Friedrich Gauss. Due to magnetic hysteresis, it is generally not ...

of Allied ships, Dönitz decided to use new contact pistols copied from British torpedoes found in the captured submarine . The depth setting mechanism was improved but only in January 1942 were the last complications with that mechanism discovered and fixed, making the torpedo more reliable.

British situation

The German occupation of Norway in April 1940, the rapid conquest of the

Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

and France in May and June, and the Italian entry into the war on the Axis side in June transformed the war at sea in general and the Atlantic campaign in particular in three main ways:

* Britain lost its biggest ally. In 1940, the French Navy was the fourth largest in the world. Only a handful of French ships joined the

Free French Forces

__NOTOC__

The French Liberation Army ( ; AFL) was the reunified French Army that arose from the merging of the Armée d'Afrique with the prior Free French Forces (; FFL) during World War II. The military force of Free France, it participated ...

and fought against Germany, though these were later joined by a few Canadian

destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

s. With the French fleet removed from the campaign, the Royal Navy was stretched even further. Italy's declaration of war meant that Britain also had to reinforce the

Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

and establish a new group at

Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

,

Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in late-June 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place ...

, to replace the French fleet in the Western Mediterranean.

* The U-boats gained direct access to the Atlantic. Since the

English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

was relatively shallow, and was partially blocked with minefields by mid-1940, U-boats were ordered not to negotiate it and instead travel around the British Isles to reach the most profitable spot to hunt ships. The German bases in France at

Brest,

Lorient

Lorient (; ) is a town (''Communes of France, commune'') and Port, seaport in the Morbihan Departments of France, department of Brittany (administrative region), Brittany in western France.

History

Prehistory and classical antiquity

Beginn ...

, and

La Pallice

La Pallice (also known as ''grand port maritime de La Rochelle'') is the commercial deep-water port of La Rochelle, France.

During the Fall of France, on 19 June 1940, approximately 6,000 Polish soldiers in exile under the command of Stanisła ...

near

La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle'') is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime Departments of France, department. Wi ...

, were about closer to the Atlantic than the bases on the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. This greatly improved the situation for U-boats in the Atlantic, enabling them to attack convoys further west and letting them spend longer on patrol, doubling the effective size of the U-boat force. The Germans later built huge fortified concrete

submarine pen

A submarine pen (''U-Boot-Bunker'' in German) is a type of submarine base that acts as a bunker to protect submarines from air attack.

The term is generally applied to submarine bases constructed during World War II, particularly in Germany and ...

s for the U-boats in the French Atlantic bases, impervious to Allied bombing until mid-1944 with the advent of the

Tallboy bomb

Tallboy or Bomb, Medium Capacity, 12,000 lb was an earthquake bomb developed by the British aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis and used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War."Medium capacity" refers to the ratio of bomb ...

. From early July, U-boats returned to the new French bases when they had completed their Atlantic patrols, the first being at Lorient.

* British destroyers were diverted from the Atlantic. The

Norwegian campaign and the

German invasion of the Low Countries and France strained the Royal Navy's destroyer flotillas. Many older destroyers were withdrawn from convoy routes to support the Norwegian campaign in April and May and then diverted to the English Channel to support the withdrawal from Dunkirk. By mid-1940, Britain faced a serious threat of invasion. Many destroyers were held in the Channel to repel a German invasion. They suffered heavily under air attack by the . Seven destroyers were lost in the Norwegian campaign, another six in the

Battle of Dunkirk

The Battle of Dunkirk () was fought around the French Third Republic, French port of Dunkirk, Dunkirk (Dunkerque) during the Second World War, between the Allies of World War II, Allies and Nazi Germany. As the Allies were losing the Battle ...

and a further 10 in the Channel and North Sea between May and July, many to air attack because they lacked an adequate anti-aircraft armament. Dozens of others were damaged.

Completion of Hitler's campaign in Western Europe meant U-boats withdrawn from the Atlantic for the Norwegian campaign could return to the war on trade. Therefore, the number of U-boats in the Atlantic began to rise while the availability of convoy escorts greatly decreased. The only consolation for the British was that the large merchant fleets of occupied countries like Norway and the Netherlands came under British control. After the German occupation of Denmark and Norway, Britain

occupied Iceland and the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

, establishing bases and preventing a German takeover.

It was in these circumstances that Winston Churchill, who had become

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

on 10 May 1940, first wrote to

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

to request the loan of fifty obsolescent US Navy destroyers. This led to the "

Destroyers for Bases Agreement

The destroyers-for-bases deal was an agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom on 2 September 1940, according to which 50 , , and -class US Navy destroyers were transferred to the Royal Navy from the US Navy in exchange for lan ...

", effectively a sale portrayed as a loan for political reasons, which operated in exchange for 99-year leases on certain British bases in

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

,

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

and the

West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. This was a profitable bargain for the United States and militarily beneficial for Britain, freeing up British military assets to return to Europe. A significant percentage of the US population opposed entering the war, and some American politicians (including the US Ambassador to Britain,

Joseph P. Kennedy

Joseph Patrick Kennedy Sr. (September 6, 1888 – November 18, 1969) was an American businessman, investor, philanthropist, and politician. He is known for his own political prominence as well as that of his children and was the ambitious patri ...

) believed Britain and its allies might lose. The first of these destroyers were only taken over by their British and Canadian crews in September, and all needed to be rearmed and fitted with ASDIC. It was many months before these ships contributed to the campaign.

'The Happy Time' (June 1940 – February 1941)

The early U-boat operations from the French bases were spectacularly successful. This was the heyday of the great U-boat aces like Günther Prien of ''U-47'',

Otto Kretschmer

Otto Kretschmer (1 May 1912 – 5 August 1998) was a German naval officer and submariner in World War II and the Cold War.

From September 1939 until his capture in March 1941 he sank 44 ships, including one warship, a total of 274,333 tons. For t ...

(),

Joachim Schepke

Joachim Schepke (8 March 1912 – 17 March 1941) was a German U-boat commander during World War II. He was the seventh recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves.

Schepke is credited with having sunk 36 Allied ships. Durin ...

(),

Engelbert Endrass

Engelbert Endrass () (2 March 1911 – 21 December 1941) was a German U-boat commander in World War II. He commanded the and the , being credited with sinking 22 ships on ten patrols, for a total of of Allied shipping, to purportedly become th ...

(),

Victor Oehrn () and

Heinrich Bleichrodt

Heinrich Bleichrodt (21 October 1909 – 9 January 1977) was a German U-boat commander during the World War II, Second World War. From October 1939 until retiring from front line service in December 1943, he was credited with sinking 25 ships for ...

(). U-boat crews became heroes in Germany. From June until October 1940, over 270 Allied ships were sunk; this period was referred to by U-boat crews as "the Happy Time" (""). Churchill would later write: "...the only thing that ever frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril".

The biggest challenge for U-boats was to find the convoys in the vastness of the ocean. The Germans had a handful of very long-range

Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor

The Focke-Wulf Fw 200 ''Condor'', also known as ''Kurier'' (German for ''courier'') to the Allies, is an all-metal four-engined monoplane designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Focke-Wulf. It was the first heavier-than-air craf ...

aircraft based at

Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

and

Stavanger

Stavanger, officially the Stavanger Municipality, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the third largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the ...

, which were used for reconnaissance. The Condor was a converted civilian airliner—a stop-gap solution for . Due to ongoing friction between the and , the primary source of convoy sightings was the U-boats themselves. Since a submarine's bridge was very close to the water, their range of visual detection was short.

The best source proved to be the codebreakers of who had succeeded in deciphering the British Naval Cypher No. 3, allowing the Germans to estimate where and when convoys could be expected.

In response, the British applied the techniques of

operations research

Operations research () (U.S. Air Force Specialty Code: Operations Analysis), often shortened to the initialism OR, is a branch of applied mathematics that deals with the development and application of analytical methods to improve management and ...

and developed some counter-intuitive solutions for protecting convoys. Realising the area of a convoy increased by the square of its perimeter, they determined that the same number of ships and escorts would be better protected in a single convoy than two. A large convoy was as difficult to locate as a small one. Reduced frequency also reduced the chances of detection, as fewer large convoys could carry the same amount of cargo, while large convoys take longer to assemble. Therefore, a few large convoys with apparently few escorts were safer than many small convoys with a higher ratio of escorts to merchantmen.

Instead of attacking the Allied convoys singly, U-boats were directed to work in wolf packs () coordinated by radio. The boats spread out into a long patrol line that bisected the path of the Allied convoy routes. Once in position, the crew studied the horizon through

binoculars

Binoculars or field glasses are two refracting telescopes mounted side-by-side and aligned to point in the same direction, allowing the viewer to use both eyes (binocular vision) when viewing distant objects. Most binoculars are sized to be held ...

looking for masts or smoke, or used hydrophones to pick up propeller noises. When one boat sighted a convoy, it would report the sighting to

U-boat headquarters, shadowing and continuing to report as needed until other boats arrived, typically at night. Instead of being faced by single submarines, the convoy escorts then had to cope with groups of up to half a dozen U-boats attacking simultaneously. The most daring commanders, such as Kretschmer, penetrated the escort screen and attacked from within the columns of merchantmen. The escort vessels, which were too few in number and often lacking in endurance, had no answer to multiple submarines attacking on the surface at night, as their ASDIC worked well only against underwater targets.

Early British marine radar, working in the

metric bands, lacked target discrimination and range. Corvettes were too slow to catch a surfaced U-boat.

Pack tactics were first used successfully in September and October 1940 to devastating effect, in a series of convoy battles. On 21 September,

convoy HX 72 of 42 merchantmen was attacked by a pack of four U-boats, which sank eleven ships and damaged two over the course of two nights. In October, the slow

convoy SC 7

Convoy SC 7 was the name of a large Allied convoy in the Second World War comprising 35 merchant ships and six escorts. The convoy sailed eastwards from Sydney, Nova Scotia, for Liverpool and other British ports on 5 October 1940. While cro ...

, with an escort of two

sloops and two corvettes, was overwhelmed, losing 59% of its ships. The battle for

HX 79 in the following days was in many ways worse for the escorts than for SC 7. The loss of a quarter of the convoy without any loss to the U-boats, despite a very strong escort (two destroyers, four corvettes, three trawlers, and a minesweeper) demonstrated the effectiveness of the German tactics against the inadequate British anti-submarine methods. On 1 December, seven German and three Italian submarines caught

HX 90, sinking 10 ships and damaging three others.

At the end of 1940, the Admiralty viewed the number of ships sunk with growing alarm. Damaged ships might survive but could be out of commission for long periods. Two million gross tons of merchant shipping—13% of the fleet available to the British—were under repair and unavailable, which had the same effect in slowing down cross-Atlantic supplies.

Nor were the U-boats the only threat. Following some early experience in support of the war at sea during Operation Weserübung, the began to take a toll of merchant ships.

Martin Harlinghausen and his recently established command——contributed small numbers of aircraft to the Battle of the Atlantic from 1941 onwards. These were primarily Fw 200 Condors. The Condors also bombed convoys that were beyond land-based fighter cover and thus defenceless. Initially, the Condors were very successful, claiming 365,000 tons of shipping in early 1941. These aircraft were few in number, and directly under control; the pilots had little specialised training for anti-shipping warfare, limiting their effectiveness.

Italian submarines in the Atlantic

The Germans received help from their allies. From August 1940, a flotilla of 27 Italian submarines operated from the

BETASOM

BETASOM (an Italian language acronym of ''Bordeaux Sommergibile'' or ''Sommergibili'') was a submarine base established at Bordeaux, France by the '' Regia Marina'' during the Second World War. From this base, Italian submarines participated in t ...

base in Bordeaux to attack Allied shipping in the Atlantic, initially under the command of Rear Admiral

Angelo Parona, then of Rear Admiral

Romolo Polacchini and finally of ship-of-the-line captain

Enzo Grossi. The Italian submarines had been designed to operate in a different way than U-boats, and they had flaws that needed to be corrected (for example huge conning towers, slow speed when surfaced, lack of modern torpedo fire control), which meant that they were ill-suited for convoy attacks, and performed better when hunting down isolated merchantmen on distant seas, taking advantage of their superior range and living standards. Initial operation met with little success (only 65343 GRT sunk between August and December 1940), but the situation improved gradually, and up to August 1943 the 32 Italian submarines that operated there sank 109 ships of 593,864 tons, for 17 subs lost in return, giving them a subs-lost-to-tonnage sunk ratio similar to Germany's in the same period, and higher overall. The Italians were also successful with their use of "

human torpedo

Human torpedoes or manned torpedoes are a type of diver propulsion vehicle on which the diver rides, generally in a seated position behind a fairing. They were used as secret naval weapons in World War II. The basic concept is still in use.

...

" chariots, disabling several British ships in Gibraltar.

Despite these successes, the Italian intervention was not favourably regarded by Dönitz, who characterised Italians as "inadequately disciplined" and "unable to remain calm in the face of the enemy". They were unable to co-operate in wolf pack tactics or even reliably report contacts or weather conditions, and their area of operation was moved away from that of the Germans.

Amongst the more successful Italian submarine commanders who operated in the Atlantic were

Carlo Fecia di Cossato, commander of the , and

Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia, commander of and then of .

Great surface raiders

Despite their success, U-boats were still not recognised as the foremost threat to the North Atlantic convoys. With the exception of men like Dönitz, most naval officers on both sides regarded surface warships as the ultimate commerce destroyers.

For the first half of 1940, there were no German surface raiders in the Atlantic because the German Fleet had been concentrated for the invasion of Norway. The sole pocket battleship raider, ''Admiral Graf Spee'', had been stopped at the Battle of the River Plate by an inferior and outgunned British squadron. From mid-1940 a small but steady stream of warships and

armed merchant raiders set sail from Germany for the Atlantic.

The power of a raider against a convoy was demonstrated by the fate of

convoy HX 84

Convoy HX 84 was the 84th of the numbered series of Allied North Atlantic HX convoys of merchant ships from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Bermuda to Liverpool, England, during the Battle of the Atlantic. Thirty-eight ships escorted by the armed m ...

, attacked by the pocket battleship on 5 November 1940. ''Admiral Scheer'' quickly sank five ships and damaged several others as the convoy scattered. Only the sacrifice of the escorting armed merchant cruiser (whose commander,

Edward Fegen, was awarded a posthumous

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious decoration of the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British decorations system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British ...

) and failing light allowed the other merchantmen to escape. The British suspended North Atlantic convoys and the

Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

put to sea in an unsuccessful attempt to intercept ''Admiral Scheer,'' which disappeared into the South Atlantic. She reappeared in the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

the following month.

Other German surface raiders now began to make their presence felt. On Christmas Day 1940, the cruiser attacked the troop convoy WS 5A, but was driven off by the escorting cruisers. ''Admiral Hipper'' had more success two months later, on 12 February 1941, when she found the unescorted

convoy SLS 64 of 19 ships, sinking seven. In January 1941, the battleships and put to sea from Germany to raid the shipping lanes in

Operation Berlin. With so many German raiders at large in the Atlantic, the British were forced to provide battleship escorts to as many convoys as possible. This twice saved convoys from slaughter by the German battleships. In February, the old battleship deterred an attack on

HX 106. A month later,

SL 67 was saved by the presence of .

In May, the Germans mounted the most ambitious raid of all:

Operation Rheinübung

Operation Rheinübung () was the last sortie into the Atlantic by the new German battleship and heavy cruiser on 18–27 May 1941, during World War II. This operation aimed to disrupt Allied shipping to the United Kingdom as the previously ...

. The new battleship and the cruiser put to sea to attack convoys. A British fleet intercepted the raiders off Iceland. In the

Battle of the Denmark Strait

The Battle of the Denmark Strait was a naval engagement in the Second World War, which took place on 24 May 1941 between ships of the Royal Navy and the ''Kriegsmarine''. The British battleship and the battlecruiser fought the German battlesh ...

, the battlecruiser was blown up and sunk, but ''Bismarck'' was damaged and had to run to France. ''Bismarck'' nearly reached her destination, but was disabled by an airstrike from the carrier ''Ark Royal'', and then sunk by the Home Fleet the next day. Her sinking marked the end of the warship raids. The advent of long-range search aircraft, notably the unglamorous but versatile

PBY Catalina

The Consolidated Model 28, more commonly known as the PBY Catalina (U.S. Navy designation), is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft designed by Consolidated Aircraft in the 1930s and 1940s. In U.S. Army service, it was designated as the O ...

, largely neutralised surface raiders.

In February 1942, ''Scharnhorst'', ''Gneisenau'' and ''Prinz Eugen'' moved from Brest back to Germany in the "

Channel Dash

The Channel Dash (, Operation Cerberus) was a German naval operation during the Second World War. A (German Navy) squadron comprising two s, and , the heavy cruiser and their escorts was evacuated from Brest in Brittany to German ports. '' ...

". While this was an embarrassment for the British, it was the end of the German surface threat in the Atlantic. The loss of ''Bismarck'', the destruction of the network of supply ships that supported surface raiders, the repeated damage to the three ships by air raids, the entry of the United States into the war,

Arctic convoys

The Arctic convoys of World War II were oceangoing convoys which sailed from the United Kingdom, Iceland, and North America to northern ports in the Soviet Union – primarily Arkhangelsk (Archangel) and Murmansk in Russia. There were 78 convoys ...

, and the perceived invasion threat to Norway had persuaded Hitler and the naval staff to withdraw.

Escort groups (March–May 1941)

The disastrous convoy battles of October 1940 forced a change in British tactics. The most important of these was the introduction of permanent escort groups to improve the coordination and effectiveness of ships and men in battle. British efforts were helped by a gradual increase in the number of escort vessels available as the old

ex-American destroyers and the new British- and Canadian-built s were now coming into service in numbers. Many of these ships became part of the huge expansion of the Royal Canadian Navy, which grew from a handful of destroyers at the outbreak of war to take an increasing share of convoy escort duty. Others of the new ships were crewed by Free French, Norwegian and Dutch, but these were a tiny minority of the total number, and directly under British command. By 1941 American public opinion had begun to swing against Germany, but the war was still essentially Great Britain and the Empire against Germany.

Initially, the new escort groups consisted of two or three destroyers and half a dozen corvettes. Since two or three of the group would usually be in dock repairing weather or battle damage, the groups typically sailed with about six ships. The training of the escorts also improved as the realities of the battle became obvious. A new base was set up at

Tobermory in the

Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

to prepare the new escort ships and their crews for the demands of battle under the strict regime of Vice-Admiral

Gilbert O. Stephenson.

In February 1941, the Admiralty moved the headquarters of Western Approaches Command from

Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

to

Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, where much closer contact with, and control of, the Atlantic convoys was possible. Greater cooperation with supporting aircraft was also achieved. In April, the Admiralty took over operational control of Coastal Command aircraft. Tactically, new short-wave radar sets that could detect surfaced U-boats and were suitable for both small ships and aircraft began to arrive during 1941.

The impact of these changes first began to be felt in the battles in early 1941. In early March, Prien in ''U-47'' failed to return from patrol. Two weeks later, in the battle of

Convoy HX 112

HX 112 was a North Atlantic convoy of the HX series which ran during the battle of the Atlantic in the Second World War. It saw the loss of U-boats commanded by two of the Kriegsmarine's most celebrated commanders and propaganda heroes: under ...

, the newly formed 3rd Escort Group of four destroyers and two corvettes held off the U-boat pack. ''U-100'' was detected by the primitive radar on the destroyer , rammed and sunk. Shortly afterwards ''U-99'' was also caught and sunk, its crew captured. Dönitz had lost his three leading aces: Kretschmer, Prien, and Schepke.

Dönitz now moved his wolf packs further west, in order to catch the convoys before the anti-submarine escort joined. This new strategy was rewarded at the beginning of April when the pack found

Convoy SC 26 before its anti-submarine escort had joined. Ten ships were sunk, but another U-boat was lost.

The field of battle widens (June–December 1941)

Growing American activity

In June 1941, the British decided to provide convoy escort for the full length of the North Atlantic crossing. To this end, the Admiralty asked the Royal Canadian Navy on 23 May, to assume the responsibility for protecting convoys in the western zone and to establish the base for its escort force at

St. John's, Newfoundland. On 13 June 1941, Commodore

Leonard Murray, Royal Canadian Navy, assumed his post as Commodore Commanding

Newfoundland Escort Force, under the overall authority of the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, at Liverpool. Six Canadian destroyers and 17 corvettes, reinforced by seven destroyers, three sloops, and five corvettes of the Royal Navy, were assembled for duty in the force, which escorted the convoys from Canadian ports to Newfoundland and then on to a meeting point south of Iceland, where the British escort groups took over.

By 1941, the United States was taking an increasing part in the war, despite its nominal neutrality. In April 1941 President Roosevelt extended the

Pan-American Security Zone

During the early years of World War II before the United States became a formal belligerent, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a region of the Atlantic, adjacent to the Americas, as the Pan-American Security Zone. Within this zone, United St ...

east almost as far as Iceland. British forces occupied Iceland when Denmark fell to the Germans in 1940; the US was persuaded to provide forces to relieve British troops on the island. American warships began escorting Allied convoys in the western Atlantic as far as Iceland, and had several hostile encounters with U-boats.

In June 1941, the US realised the tropical Atlantic had become dangerous for unescorted American as well as British ships. On 21 May, , an American vessel carrying no military supplies, was sunk by west of

Freetown, Sierra Leone

Freetown () is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational an ...

. When news of the sinking reached the US, few shipping companies felt truly safe anywhere. As ''Time'' magazine noted in June 1941, "if such sinkings continue, U.S. ships bound for other places remote from fighting fronts, will be in danger. Henceforth the U.S. would either have to recall its ships from the ocean or enforce its right to the free use of the seas."

A

Mid-Ocean Escort Force of British, Canadian, and American destroyers and corvettes was organised following the declaration of war by the United States in December 1941.

At the same time, the British were working on technical developments to address the German submarine superiority. Though these were British inventions, the critical technologies were provided freely to the US, which then renamed and manufactured them. Likewise, the US provided the British with Catalina flying boats and

Liberator bombers that were important contributions to the war effort.

Catapult aircraft merchantmen

Aircraft ranges were constantly improving, but the Atlantic was far too large to be covered completely by land-based types. A stop-gap measure was instituted by fitting ramps to the front of some of the cargo ships known as ''catapult aircraft merchantmen'' (

CAM ship

CAM ships were World War II–era British merchant ships used in convoys as an emergency stop-gap until sufficient escort carriers became available. ''CAM ship'' is an acronym for catapult aircraft merchant ship.Wise, pp. 70–77

They wer ...

s), equipped with a lone expendable

Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

fighter aircraft. When a German bomber approached, the fighter was launched off the end of the ramp

with a large rocket to shoot down or drive off the German aircraft, the pilot then

ditching

In aviation, a water landing is, in the broadest sense, an aircraft landing on a body of water. Seaplanes, such as floatplanes and flying boats, land on water as a normal operation. Ditching is a controlled emergency landing on the water sur ...

in the water and—in the best case—recovered by ship. Nine combat launches were made, resulting in the destruction of eight Axis aircraft for the loss of one Allied pilot.

Although CAM ships and their Hurricanes did not down a great number of enemy aircraft, such aircraft were mostly Fw 200 Condors that would often shadow the convoy out of range of the convoy's guns, reporting back the convoy's course and position so that U-boats could then be directed on to the convoy. The CAM ships and their Hurricanes thus justified the cost in fewer ship losses overall.

High-frequency direction-finding

One of the more important developments was ship-borne direction-finding radio equipment, known as HF/DF (high-frequency direction-finding, or

Huff-Duff

High-frequency direction finding, usually known by its abbreviation HF/DF or nickname huff-duff, is a type of radio direction finder (RDF) introduced in World War II. High frequency (HF) refers to a radio band that can effectively communicate ove ...

), which started to be fitted to escorts from February 1942. These sets were common items of equipment by early 1943.

HF/DF let an operator determine the direction of a radio signal, regardless of whether the content could be read. Since the wolf pack relied on U-boats reporting convoy positions by radio, there was a steady stream of messages to intercept. An escort could then run in the direction of the signal and attack the U-boat, or at least force it to submerge (causing it to lose contact), which might prevent an attack on the convoy. When two ships fitted with HF/DF accompanied a convoy, a fix on the transmitter's position, not just direction, could be determined. The standard approach of anti-submarine warships was immediately to "run-down" the bearing of a detected signal, hoping to spot the U-boat on the surface and make an immediate attack. Range could be estimated by an experienced operator from the signal strength. Usually the target was found visually. If the submarine was slow to dive, the guns were used; otherwise an ASDIC search was started where the swirl of water of a crash-diving submarine was observed. In good visibility a U-boat might try and outrun an escort on the surface whilst out of gun range.

The British also made extensive use of shore HF/DF stations, to keep convoys updated with positions of U-boats. HF/DF was also installed on American ships.

The radio technology behind direction finding was simple and well understood by both sides, but the technology commonly used before the war used a manually-rotated aerial to fix the direction of the transmitter. This was delicate work, took quite a time to accomplish to any degree of accuracy, and since it only revealed the line along which the transmission originated a single set could not determine if the transmission was from the true direction or its reciprocal 180 degrees in the opposite direction. Two sets were required to fix the position. Believing this to still be the case, German U-boat radio operators considered themselves fairly safe if they kept messages short. The British developed an oscilloscope-based indicator which instantly fixed the direction and its reciprocal the moment a radio operator touched his

Morse

Morse may refer to:

People

* Morse (surname)

* Morse Goodman (1917-1993), Anglican Bishop of Calgary, Canada

* Morse Robb (1902–1992), Canadian inventor and entrepreneur

Geography Antarctica

* Cape Morse, Wilkes Land

* Mount Morse, Churchi ...

key. It worked simply with a crossed pair of conventional and fixed directional aerials, the oscilloscope display showing the relative received strength from each aerial as an elongated ellipse showing the line relative to the ship. The innovation was a 'sense' aerial, which, when switched in, suppressed the ellipse in the 'wrong' direction leaving only the correct bearing. With this there was hardly any need to triangulate—the escort could just run down the precise bearing provided, estimating range from the signal strength, and use look-outs or radar for final positioning. Many U-boat attacks were suppressed and submarines sunk in this way.

Enigma cipher

The way Dönitz conducted the U-boat campaign required relatively large volumes of radio traffic between U-boats and headquarters. This was thought to be safe, as the radio messages were encrypted using the

Enigma cipher machine

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

, which the Germans considered unbreakable. In addition, the used much more secure operating procedures than the (Army) or (Air Force). The machine's three rotors were chosen from a set of eight (rather than the other services' five). The rotors were changed every other day using a system of

key sheets and the message settings were different for every message and determined from

"bigram tables" that were issued to operators. In 1939, it was generally believed at the British

Government Code and Cypher School

The Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) was a British signals intelligence agency set up in 1919. During the First World War, the British Army and Royal Navy had separate signals intelligence agencies, MI1b and NID25 (initially known as R ...

at

Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and Bletchley Park estate, estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire), that became the principal centre of Allies of World War II, Allied World War II cryptography, code-breaking during the S ...

that naval Enigma could not be broken. Only the head of the German Naval Section,

Frank Birch, and the mathematician

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing (; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954) was an English mathematician, computer scientist, logician, cryptanalyst, philosopher and theoretical biologist. He was highly influential in the development of theoretical computer ...

believed otherwise.

The British codebreakers needed to know the wiring of the special naval Enigma rotors. The capture of several Enigma rotors during the sinking of by in February 1940 provided this information. In early 1941, the Royal Navy made a concerted effort to assist the codebreakers, and on 9 May crew members of the destroyer boarded and recovered cryptologic material, including bigram tables and current Enigma keys. The captured material allowed all U-boat traffic to be read for several weeks, until the keys ran out; the familiarity codebreakers gained with the usual content of messages helped in breaking new keys.

In August 1940, the British began use of their "

bombe

The bombe () was an Electromechanics, electro-mechanical device used by British cryptologists to help decipher German Enigma machine, Enigma-machine-encrypted secret messages during World War II. The United States Navy, US Navy and United Sta ...

" computer which, when presented with an intercepted German Enigma message, suggested possible settings with which the Enigma cipher machine had been programmed. A reverse-engineered Enigma machine in British hands could then be programmed with each set of suggested settings in turn until the message was successfully deciphered.

Throughout late 1941, Enigma intercepts (combined with HF/DF) enabled the British to plot the positions of U-boat patrol lines and route convoys around them. Merchant ship losses dropped by over two-thirds in July 1941, and losses remained low until November.

This Allied advantage was offset by the growing numbers of U-boats coming into service. The

Type VIIC

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

began reaching the Atlantic in large numbers in 1941; by the end of 1945, 568 had been

commissioned. Although the Allies could protect their convoys in late 1941, they were not sinking many U-boats. The Flower-class corvette escorts could detect and defend, but were not fast enough to attack effectively.

U-boat captured by an aircraft

A Coastal Command

Hudson

Hudson may refer to:

People

* Hudson (given name)

* Hudson (surname)

* Hudson (footballer, born 1986), Hudson Fernando Tobias de Carvalho, Brazilian football right-back

* Hudson (footballer, born 1988), Hudson Rodrigues dos Santos, Brazilian f ...

of

No. 209 Squadron RAF

Number 209 Squadron of the British Royal Air Force was originally formed from a nucleus of "Naval Eight" on 1 February 1917 at Saint-Pol-sur-Mer, France, as No. 9 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS)Rawlings 1978, p. 324. and saw active servi ...

captured ''U-570'' on 27 August 1941 about south of Iceland. Squadron Leader J. Thompson sighted the U-boat on the surface, immediately dived at his target, and released four depth charges as the submarine crash dived. The U-boat surfaced again, crewmen appeared on deck, and Thompson engaged them with his aircraft's guns. The crewmen returned to the conning tower under fire. A few moments later, a white flag and a similarly coloured board were displayed. Thompson called for assistance and circled the German vessel. A Catalina from 209 Squadron took over watching the damaged U-boat until the arrival of the armed trawler ''Kingston Agate'' under Lt Henry Owen L'Estrange. The following day the U-boat was beached in an Icelandic cove. No codes or secret papers were recovered, but the British now possessed a complete U-boat. After a refit, ''U-570'' was commissioned into the Royal Navy as .

Mediterranean diversion

In October 1941, Hitler ordered Dönitz to move U-boats into the Mediterranean Sea to support German operations in that theatre. The resulting concentration near Gibraltar produced a series of battles around the Gibraltar and Sierra Leone convoys. In December 1941,

Convoy HG 76 sailed, escorted by the 36th Escort Group of two sloops and six corvettes under Captain

Frederic John Walker, reinforced by the first of the new

escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slower type of aircraf ...

s, , and three destroyers from Gibraltar. The convoy was immediately intercepted by the waiting U-boat pack, resulting in a brutal five-day battle. Walker was a tactical innovator and his ships' crews were highly trained. The presence of an escort carrier meant U-boats were frequently sighted and forced to dive before they could get close to the convoy, at least until ''Audacity'' was sunk after two days. The five-day battle cost the Germans five U-boats (four sunk by Walker's group), while the British lost ''Audacity'', a destroyer, and only two merchant ships. The battle was the first clear Allied convoy victory.

Through dogged effort, the Allies slowly gained the upper hand until the end of 1941. Although Allied warships failed to sink U-boats in large numbers, most convoys evaded attack completely. Shipping losses were high, but manageable.

Operation Drumbeat (January–June 1942)

The

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

and the subsequent German declaration of war on the United States had an immediate effect on the campaign. Dönitz planned to attack shipping off the

American East Coast. He had only five

Type IX boats able to reach US waters for

Operation Drumbeat

The Second Happy Time (; officially (), and also known among German submarine commanders as the "American Shooting Season") was a phase in the Battle of the Atlantic during which Axis submarines attacked merchant shipping and Allied naval v ...

(''Paukenschlag''), sometimes called the "second happy time" by the Germans.