Arc Measurement Of Delambre And Méchain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain was a geodetic survey carried out by Jean-Baptiste Delambre and

The arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain was a geodetic survey carried out by Jean-Baptiste Delambre and

Archive.org

an

Forgotten Books

(). In addition the book has been reprinted b

Nabu Press

(), the first chapter covers the history of early surveys. The arc was measured with at least three latitude determinations, so they were able to deduce mean curvatures for the northern and southern halves of the arc, allowing a determination of the overall shape. The results indicated that the Earth was a ''prolate'' spheroid (with an equatorial radius less than the polar radius). To resolve the issue, the

Geodetic surveys found practical applications in French cartography and in the Anglo-French Survey, which aimed to connect

Geodetic surveys found practical applications in French cartography and in the Anglo-French Survey, which aimed to connect

From the French revolution of 1789 came an effort to reform measurement standards, leading ultimately to remeasure the meridian passing through Paris in order to define the

From the French revolution of 1789 came an effort to reform measurement standards, leading ultimately to remeasure the meridian passing through Paris in order to define the  The project was split into two parts – the northern section of 742.7 km from the belfry of the Church of Saint-Éloi, Dunkirk to Rodez Cathedral which was surveyed by Delambre and the southern section of 333.0 km from

The project was split into two parts – the northern section of 742.7 km from the belfry of the Church of Saint-Éloi, Dunkirk to Rodez Cathedral which was surveyed by Delambre and the southern section of 333.0 km from

Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

in 1792–1798 to measure an arc section of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

between Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

. This arc measurement served as the basis for the original definition of the metre

The metre (or meter in US spelling; symbol: m) is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). Since 2019, the metre has been defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of ...

.

Until the French Revolution of 1789, France was particularly affected by the proliferation of length measures; the conflicts related to units helped precipitate the revolution. In addition to rejecting standards inherited from feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

, linking determination of a decimal unit of length with the figure of the Earth

In geodesy, the figure of the Earth is the size and shape used to model planet Earth. The kind of figure depends on application, including the precision needed for the model. A spherical Earth is a well-known historical approximation that is ...

was an explicit goal. This project culminated in an immense effort to measure a meridian passing through Paris in order to define the metre

The metre (or meter in US spelling; symbol: m) is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). Since 2019, the metre has been defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of ...

.

When question of measurement reform was placed in the hands of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

, a commission, whose members included Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

, Joseph-Louis Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi LagrangiaPierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, Gaspard Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Péluse (; 9 May 1746 – 28 July 1818) was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry, (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geometry. Dur ...

and the Marquis de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French Philosophy, philosopher, Political economy, political economist, Politics, politician, and m ...

, decided that the new measure should be equal to one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator (the quadrant of the Earth's circumference), measured along the meridian passing through Paris at the longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

of Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

. Since this survey, the Panthéon

The Panthéon (, ), is a monument in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France. It stands in the Latin Quarter, Paris, Latin Quarter (Quartier latin), atop the , in the centre of the , which was named after it. The edifice was built between 1758 ...

became the central geodetic station in Paris.

In 1791, Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on the ...

and Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

were commissioned to lead an expedition to accurately measure the distance between a belfry in Dunkerque and Montjuïc castle in Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

in order to calculate the length of the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

through the centre of Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

. The official length of the '' Mètre des Archives'' was based on these measurements, but the definitive length of the metre required a value for the non-spherical shape of the Earth, known as the flattening of the Earth. Pierre Méchain's and Jean-Baptiste Delambre's measurements were combined with the results of the French Geodetic Mission to the Equator and a value of was found for the Earth's flattening.

The distance from the North Pole to the Equator was then extrapolated from the measurement of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

arc between Dunkirk and Barcelona and the length of the metre was established, in relation to the also called toise of Peru, which had been constructed in 1735 for the French Geodesic Mission to Peru, as well as to Borda's double-toise N°1, one of the four twelve feet (French: ) long ruler, part of the baseline measuring instrument devised for this survey. When the final result was known, the ''Mètre des Archives'' a platinum bar whose length was closest to the meridional definition of the metre was selected and placed in the National Archives on 22 June 1799 (4 messidor An VII in the Republican calendar) as a permanent record of the result.

Scientific revolution in France and beginning of Greenwich arc measurement

TheFrench Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

, responsible for the concept and definition of the metre, was established in 1666. In the 17th century it had determined the first reasonably accurate distance to the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

and organised important work in geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

and cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

. In the 18th century, in addition to its significance for cartography

Cartography (; from , 'papyrus, sheet of paper, map'; and , 'write') is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an imagined reality) can ...

, geodesy

Geodesy or geodetics is the science of measuring and representing the Figure of the Earth, geometry, Gravity of Earth, gravity, and Earth's rotation, spatial orientation of the Earth in Relative change, temporally varying Three-dimensional spac ...

grew in importance as a means of empirically demonstrating Newton's law of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

, which Émilie du Châtelet

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (; 17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749) was a French mathematician and physicist.

Her most recognized achievement is her philosophical magnum opus, ''Institutions de Physique'' ...

promoted in France in combination with Leibniz's mathematical work and because the radius of the Earth was the unit to which all celestial distances were to be referred. Among the results that would impact the definition of the metre: Earth proved to be an oblate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface obtained by rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with two equal semi-diameters. A spheroid has circu ...

through geodetic surveys in Ecuador

Ecuador, officially the Republic of Ecuador, is a country in northwestern South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean on the west. It also includes the Galápagos Province which contain ...

and Lapland.

Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

had discovered gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

explaining the fall of bodies at the surface of the Earth. He had also observed the regularity of the period of swing of the pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

and that this period depended on the length of the pendulum. Marin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, OM (also known as Marinus Mersennus or ''le Père'' Mersenne; ; 8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a French polymath whose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians for ...

was the central figure in the dissemination of Galileo's ideas in France, thanks to his role as a translator and commentator of Galileo's work. In 1645 Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of ...

had been the first to determine the length of a "seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

" (a pendulum

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate i ...

with a half-period of one second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

). In 1656, Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Halen, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , ; ; also spelled Huyghens; ; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution ...

, inspired by Galileo, invented the first pendulum clock

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dep ...

which greatly improved the accuracy of time measurement required for astronomical observations. In 1671, Jean Picard also measured the length of a seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

at Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

and proposed this unit of measurement to be called the astronomical radius (French: ''Rayon Astronomique''). He found the value of 36 ''pouces'' and 8 lignes of the Toise of Châtelet, which had been recently renewed. Proposals for decimal measurement systems from scientists and mathematicians also led to proposals to base units on reproducible natural phenomena, such as the motion of a pendulum or a fraction of the circle of latitude

A circle of latitude or line of latitude on Earth is an abstract east–west small circle connecting all locations around Earth (ignoring elevation) at a given latitude coordinate line.

Circles of latitude are often called parallels because ...

at the Equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

.

The first reasonably accurate distance to the Sun was determined in 1684 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian-French mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the County of Nice, part of the Savoyard sta ...

. Knowing that directly measurements of the solar parallax were difficult he chose to measure the Martian parallax. Having sent Jean Richer to Cayenne, part of French Guiana, for simultaneous measurements, Cassini in Paris determined the parallax of Mars when Mars was at its closest to Earth in 1672. Using the circumference distance between the two observations, Cassini calculated the Earth-Mars distance, then used Kepler's laws

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler in 1609 (except the third law, which was fully published in 1619), describe the orbits of planets around the Sun. These laws replaced circular orbits and epicycles in ...

to determine the Earth-Sun distance. His value, about 10% smaller than modern values, was much larger than all previous estimates.

Although it had been known since classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

that the Earth was spherical, by the 17th century, evidence was accumulating that it was not a perfect sphere. In 1672, Jean Richer found the first evidence that gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

was not constant over the Earth (as it would be if the Earth were a sphere); he took a pendulum clock

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dep ...

to Cayenne

Cayenne (; ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture and capital city of French Guiana, an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in South America. The city stands on a former island at the mouth of the Caye ...

, French Guiana

French Guiana, or Guyane in French, is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas and the West Indies. Bordered by Suriname to the west ...

and found that it lost minutes per day compared to its rate at Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. This indicated the acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the Rate (mathematics), rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are Euclidean vector, vector ...

of gravity was less at Cayenne than at Paris. Pendulum gravimeters began to be taken on voyages to remote parts of the world, and it was slowly discovered that gravity increases smoothly with increasing latitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

, gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

being about 0.5% greater at the geographical pole

A geographical pole or geographic pole is either of the two points on Earth where its axis of rotation intersects its surface. The North Pole lies in the Arctic Ocean while the South Pole is in Antarctica. North and South poles are also defined ...

s than at the Equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

.

In 1687, Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

had published in the '' Principia'' as a proof that the Earth was an oblate spheroid

A spheroid, also known as an ellipsoid of revolution or rotational ellipsoid, is a quadric surface (mathematics), surface obtained by Surface of revolution, rotating an ellipse about one of its principal axes; in other words, an ellipsoid with t ...

of flattening

Flattening is a measure of the compression of a circle or sphere along a diameter to form an ellipse or an ellipsoid of revolution (spheroid) respectively. Other terms used are ellipticity, or oblateness. The usual notation for flattening is f ...

equal to . This was disputed by some, but not all, French scientists. A meridian arc of Jean Picard was extended to a longer arc by Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian-French mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the County of Nice, part of the Savoyard sta ...

and his son Jacques Cassini over the period 1684–1718.. Freely available online aArchive.org

an

Forgotten Books

(). In addition the book has been reprinted b

Nabu Press

(), the first chapter covers the history of early surveys. The arc was measured with at least three latitude determinations, so they were able to deduce mean curvatures for the northern and southern halves of the arc, allowing a determination of the overall shape. The results indicated that the Earth was a ''prolate'' spheroid (with an equatorial radius less than the polar radius). To resolve the issue, the

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

(1735) undertook expeditions to Peru ( Bouguer, Louis Godin, de La Condamine, Antonio de Ulloa, Jorge Juan) and to Lapland ( Maupertuis, Clairaut, Camus, Le Monnier, Abbe Outhier, Anders Celsius

Anders Celsius (; 27 November 170125 April 1744) was a Swedes, Swedish astronomer, physicist and mathematician. He was professor of astronomy at Uppsala University from 1730 to 1744, but traveled from 1732 to 1735 visiting notable observatories ...

). The resulting measurements at equatorial and polar latitudes confirmed that the Earth was best modelled by an oblate spheroid, supporting Newton. In the 1740s an account was published in the Paris ''Mémoires'', by Cassini de Thury, of a remeasurement by himself and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille of the meridian of Paris. With a view to determine more accurately the variation of the degree along the meridian, they divided the distance from Dunkirk to Collioure into four partial arcs of about two degrees each, by observing the latitude at five stations. The results previously obtained by Giovanni Domenico and Jacques Cassini were not confirmed, but, on the contrary, the length of the degree derived from these partial arcs showed on the whole an increase with increasing latitude.

Geodetic surveys found practical applications in French cartography and in the Anglo-French Survey, which aimed to connect

Geodetic surveys found practical applications in French cartography and in the Anglo-French Survey, which aimed to connect Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

and Greenwich

Greenwich ( , , ) is an List of areas of London, area in south-east London, England, within the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London, east-south-east of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime hi ...

Observatories and led to the Principal Triangulation of Great Britain. The unit of length used by the French was the , while the English one was the yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English units, English unit of length in both the British imperial units, imperial and US United States customary units, customary systems of measurement equalling 3 foot (unit), feet or 36 inches. Sinc ...

, which became the geodetic unit used in the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

.

In 1783 the director of the Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

, César-François Cassini de Thury, addressed a memoir to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in London, in which he expressed grave reservations about the latitude and longitude measurements undertaken at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. He suggested that the correct values might be found by combining the Paris Observatory figures with a precise trigonometric survey between the two observatories. This criticism was roundly rejected by Nevil Maskelyne who was convinced of the accuracy of the Greenwich measurements but, at the same time, he realised that Cassini's memoir provided a means of promoting government funding for a survey which would be valuable in its own right.

For the triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle m ...

of the Anglo-French Survey, César-François Cassini de Thury was assisted by Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

. They used the repeating circle, an instrument for geodetic surveying, developed from the reflecting circle by Étienne Lenoir in 1784. He invented it while an assistant of Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

, who later improved the instrument. It was notable as being the equal of the great theodolite created by the renowned instrument maker, Jesse Ramsden

Jesse Ramsden Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (6 October 1735 – 5 November 1800) was a British mathematician, astronomy, astronomical and scientific instrument maker. His reputation was built on the engraving and design of dividing engine ...

. It would later be used to measure the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve (geometry), curve between two points near the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a arc (geometry), segment of the meridian (geography), meridian, or to its ...

from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

to Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

by Jean Baptiste Delambre and Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

as improvements in the measuring device designed by Borda and used for this survey also raised hopes for a more accurate determination of the length of the French meridian arc.

Invention and international adoption of the metre as scientific unit of length

metre

The metre (or meter in US spelling; symbol: m) is the base unit of length in the International System of Units (SI). Since 2019, the metre has been defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of of ...

.

The question of measurement reform was placed in the hands of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

, who appointed a commission chaired by Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

. Instead of the seconds pendulum method, the commission of the French Academy of Sciences – whose members included Borda, Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi LagrangiaLaplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, Monge

Gaspard Monge, Comte de Pelusium, Péluse (; 9 May 1746 – 28 July 1818) was a French mathematician, commonly presented as the inventor of descriptive geometry, (the mathematical basis of) technical drawing, and the father of differential geom ...

and Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; ; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher, political economist, politician, and mathematician. His ideas, including suppo ...

– decided that the new measure should be equal to one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator (the quadrant of the Earth's circumference), measured along the meridian passing through Paris at the longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east- west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lett ...

of Paris pantheon, which became the central geodetic station in Paris. Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on the ...

obtained the fundamental co-ordinates

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine and standardize the position of the points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as Euclidean space. The coordinates are ...

of the Panthéon by triangulating all the geodetic stations around Paris from the Panthéon's dome.

Apart from the obvious consideration of safe access for French surveyors, the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

was also a sound choice for scientific reasons: a portion of the quadrant from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

to Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

(about 1000 km, or one-tenth of the total) could be surveyed with start- and end-points at sea level, and that portion was roughly in the middle of the quadrant, where the effects of the Earth's oblateness were expected not to have to be accounted for.

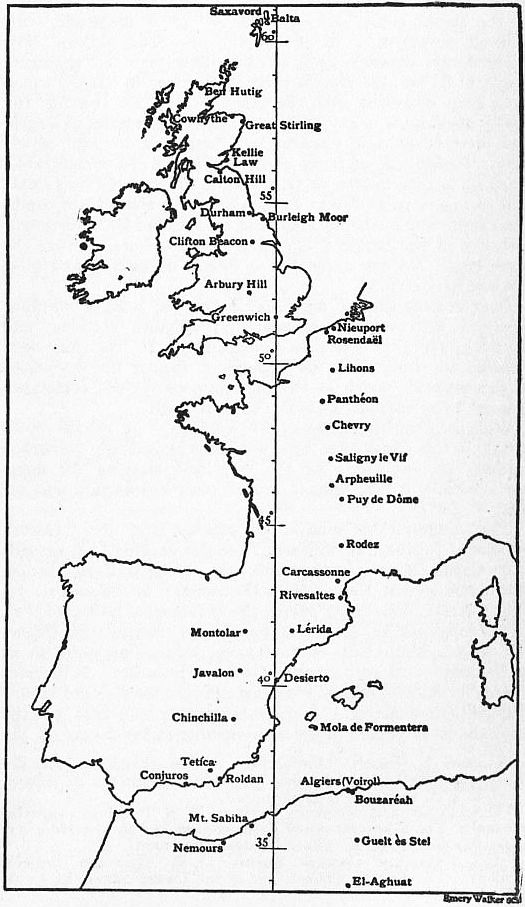

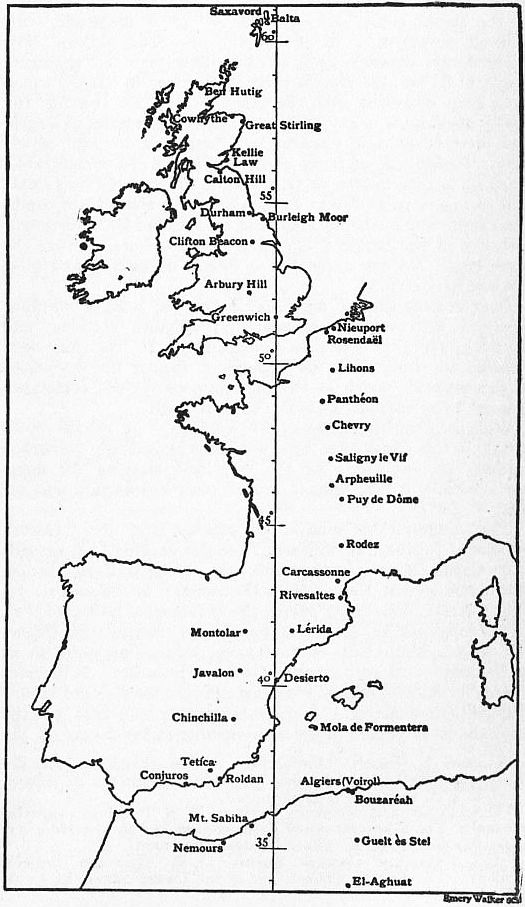

The expedition would take place after the Anglo-French Survey, thus the French meridian arc, which would extend northwards across the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, would also extend southwards to Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, later to Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands are an archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago forms a Provinces of Spain, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain, ...

. Jean-Baptiste Biot

Jean-Baptiste Biot (; ; 21 April 1774 – 3 February 1862) was a French people, French physicist, astronomer, and mathematician who co-discovered the Biot–Savart law of magnetostatics with Félix Savart, established the reality of meteorites, ma ...

and François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

would publish in 1821 their observations completing those of Delambre and Mechain. It was an account of the length's variations of portions of one degree of amplitude of the meridian arc along the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

as well as the account of the variation of the seconds pendulum

A seconds pendulum is a pendulum whose period is precisely two seconds; one second for a swing in one direction and one second for the return swing, a frequency of 0.5 Hz.

Principles

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so tha ...

's length along the same meridian between Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and the Balearc Islands.

The task of surveying the meridian arc fell to Pierre Méchain

Pierre François André Méchain (; 16 August 1744 – 20 September 1804) was a French astronomer and surveyor who, with Charles Messier, was a major contributor to the early study of deep-sky objects and comets.

Life

Pierre Méchain was bo ...

and Jean-Baptiste Delambre, and took more than six years (1792–1798). The technical difficulties were not the only problems the surveyors had to face in the convulsed period of the aftermath of the Revolution: Méchain and Delambre, and later François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago (), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: , ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries and politician.

Early l ...

, were imprisoned several times during their surveys, and Méchain died in 1804 of yellow fever, which he contracted while trying to improve his original results in northern Spain.

Rodez

Rodez (, , ; , ) is a small city and commune in the South of France, about 150 km northeast of Toulouse. It is the prefecture of the department of Aveyron, region of Occitania (formerly Midi-Pyrénées). Rodez is the seat of the communau ...

to the Montjuïc Fortress, Barcelona which was surveyed by Méchain. Although Méchain's sector was half the length of Delambre, it included the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

and hitherto unsurveyed parts of Spain.

Delambre measured a baseline of about 10 km (6,075.90 ) in length along a straight road between Melun

Melun () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region, north-central France. It is located on the southeastern outskirts of Paris, about from the centre of the capital. Melun is the prefecture of Seine-et-Marne, ...

and Lieusaint. In an operation taking six weeks, the baseline was accurately measured using four platinum rods, each of length two (a being about 1.949 m). These measuring devices consisted of bimetallic rulers in platinum and brass fixed together at one extremity to assess the variations in length produced by any change in temperature. Borda's double-toise N°1 became the main reference for measuring all geodetic bases in France. Intercomparisons of baseline measuring devices were essential, because of thermal expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to increase in length, area, or volume, changing its size and density, in response to an increase in temperature (usually excluding phase transitions).

Substances usually contract with decreasing temp ...

. Indeed, geodesists tried to accurately assess temperature of standards in the field in order to avoid temperature systematic errors

Observational error (or measurement error) is the difference between a measurement, measured value of a physical quantity, quantity and its unknown true value.Dodge, Y. (2003) ''The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms'', OUP. Such errors are ...

. Thereafter he used, where possible, the triangulation points used by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in his 1739-1740 arc measurement. Méchain's baseline was of a similar length (6,006.25 ), and also on a straight section of road between Vernet (in the Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

area) and Salces (now Salses-le-Chateau).

To put into practice the decision taken by the National Convention

The National Convention () was the constituent assembly of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for its first three years during the French Revolution, following the two-year National Constituent Assembly and the ...

, on 1 August 1793, to disseminate the new units of the decimal metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that standardization, standardizes a set of base units and a nomenclature for describing relatively large and small quantities via decimal-based multiplicative unit prefixes. Though the rules gover ...

, it was decided to establish the length of the metre based on a fraction of the meridian in the process of being measured. The decision was taken to fix the length of a provisional metre (French: ''mètre provisoire'') determined by the French meridian arc measurement, which had been carried out from Dunkirk

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

to Perpignan

Perpignan (, , ; ; ) is the prefectures in France, prefecture of the Pyrénées-Orientales departments of France, department in Southern France, in the heart of the plain of Roussillon, at the foot of the Pyrenees a few kilometres from the Me ...

by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille and Cesar-François Cassini de Thury and published by the latter in 1744. The length of the metre was established, in relation to the toise of the academy also called toise of Peru, at 3 feet 11.44 lines, taken at 13 degrees of the temperature scale of René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur in use at the time. This value was set by legislation on 7 April 1795. It was therefore metal bars of 443.44 that were distributed in France in 1795–1796. This was the metre installed under the arcades of the rue de Vaugirard

''Ruta graveolens'', commonly known as rue, common rue or herb-of-grace, is a species of the genus '' Ruta'' grown as an ornamental plant and herb. It is native to the Mediterranean. It is grown throughout the world in gardens, especially fo ...

, almost opposite the entrance to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

End of November 1798, Delambre and Méchain returned to Paris with their data, having completed the survey to meet a foreign commission composed of representatives of Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic (; ) was the Succession of states, successor state to the Dutch Republic, Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 after the Batavian Revolution and ended on 5 June 1806, with the acce ...

: Henricus Aeneae and Jean Henri van Swinden, Cisalpine Republic

The Cisalpine Republic (; ) was a sister republic or a client state of France in Northern Italy that existed from 1797 to 1799, with a second version until 1802.

Creation

After the Battle of Lodi in May 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte organized two ...

: Lorenzo Mascheroni, Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm, officially the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply Denmark, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united by the Constitution of Denmark, Constitutional Act, which applies to the entire territor ...

: Thomas Bugge, Kingdom of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

: Gabriel Císcar and Agustín de Pedrayes, Helvetic Republic: Johann Georg Tralles, Ligurian Republic: Ambrogio Multedo, Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

: Prospero Balbo, Antonio Vassali Eandi, Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

: Pietro Franchini, Tuscan Republic: Giovanni Fabbroni who had been invited by Talleyrand. The French commission comprised Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

, Barnabé Brisson, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb

Charles-Augustin de Coulomb ( ; ; 14 June 1736 – 23 August 1806) was a French officer, engineer, and physicist. He is best known as the eponymous discoverer of what is now called Coulomb's law, the description of the electrostatic force of att ...

, Jean Darcet, René Just Haüy

René Just Haüy () FRS MWS FRSE (28 February 1743 – 1 June 1822) was a French priest and mineralogist, commonly styled the Abbé Haüy after he was made an honorary canon of Notre-Dame de Paris, Notre Dame. Due to his innovative work on cryst ...

, Joseph-Louis Lagrange

Joseph-Louis Lagrange (born Giuseppe Luigi LagrangiaPierre- Simon Laplace, Louis Lefèvre-Ginneau, Pierre Méchain and Gaspar de Prony.

In 1799, a commission including Johann Georg Tralles, Jean Henri van Swinden,

In 1870, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute which he then directed until 1889. At the time it was the world's biggest geographic institute. It encompassed geodesy, general topography, leveling, cartography, statistics and the general service of weights and measures. Spain had adopted the metric system in 1849. The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of

In 1870, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute which he then directed until 1889. At the time it was the world's biggest geographic institute. It encompassed geodesy, general topography, leveling, cartography, statistics and the general service of weights and measures. Spain had adopted the metric system in 1849. The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of

Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French people, French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transforma ...

, Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

, Gabriel Císcar, Pierre Méchain and Jean-Baptiste Delambre calculated the distance from Dunkirk to Barcelona using the data of the triangulation

In trigonometry and geometry, triangulation is the process of determining the location of a point by forming triangles to the point from known points.

Applications

In surveying

Specifically in surveying, triangulation involves only angle m ...

between these two towns and determined the portion of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator it represented. Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

originally hoped to figure out the Earth ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

problem from the sole measurement of the arc from Dunkirk to Barcelona. However, when, about 1804, he would calculate it using the least squares

The method of least squares is a mathematical optimization technique that aims to determine the best fit function by minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed values and the predicted values of the model. The me ...

method, this portion of the meridian arc led for the flattening to the value of considered as unacceptable. This value was the result of a conjecture based on too limited data. Another flattening of the Earth would be calculated by Delambre, who would exclude the results of the French Geodetic Mission to Lapland and would found a value close to combining the results of Delambre and Méchain arc measurement with those of the Spanish-French Geodetic Mission taking in account a correction of the astronomic arc.

Eventually, the distance from the North Pole to the Equator was extrapolated from the measurement of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

arc between Dunkirk and Barcelona and was determined as toises assuming an Earth flattening

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the figure of the Earth, Earth's form, used as a frame of reference, reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ell ...

of . The Weights and Measures Commission adopted, in 1799, this value for the flattening based on an analysis by Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

who combined the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator and the data of the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain. Combining these two data sets Laplace succeeded to estimate the flattening

Flattening is a measure of the compression of a circle or sphere along a diameter to form an ellipse or an ellipsoid of revolution (spheroid) respectively. Other terms used are ellipticity, or oblateness. The usual notation for flattening is f ...

of the Earth ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

and was happy to find that it also fitted well with his estimate based on 15 pendulum measurements.

As the length of the metre had been set by legislation to be equal to one ten-millionth of this distance, it was defined as 0.513074 toise or 3 feet and 11.296 lines of the Toise of Peru, which had been constructed in 1735 for the French Geodesic Mission to Peru. When the final result was known, a bar whose length was closest to the definition of the legal metre was selected and placed in the National Archives on 22 June 1799 (4 messidor An VII in the Republican calendar) as a permanent record of the result. Another platinum metre, calibrated against the , and twelve iron ones were made as secondary standards. One of the iron metre standards was brought to the United States in 1805. It became known as the Committee Meter in the United States and served as a standard of length in the United States Coast Survey until 1890.

However, Louis Puissant declared in 1836 to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

that Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on the ...

and Pierre Méchain had made errors in the triangulation of the meridian arc, which had been used for determining the length of the metre. This is why Antoine Yvon Villarceau verified the geodetic operations at eight points of the Paris meridian

The Paris meridian is a meridian line running through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France – now longitude 2°20′14.02500″ East. It was a long-standing rival to the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world. The "Paris meri ...

arc from 1861 to 1866. Some of the errors in the operations of Delambre and Méchain were then corrected.

In his 2002 book ''The measure of all things'', Ken Alder recalled that the legal metre is about 0.2 millimetres shorter than it should be according to its original proposed definition. Since long, the length of the legal metre has been questioned because of an uncertainty in Méchain's determination of the latitude of the southern end of the arc measurement besides other problems in the publication of his results. This 2 km error in the Earth quadrant appeared to Adrien-Marie Legendre

Adrien-Marie Legendre (; ; 18 September 1752 – 9 January 1833) was a French people, French mathematician who made numerous contributions to mathematics. Well-known and important concepts such as the Legendre polynomials and Legendre transforma ...

when he compared toises obtained for the length of the definitive metre with toises deduced from the distance measured by Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a kingdom of France, French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the IAU designated constellations, 88 constellations. From 1750 ...

of a meridian arc of one degree at 45° of latitude which was used to fix the length of the provisional metre. He suspected a deviation of plumb-line due to gravity anomaly that geodesists now call vertical deflection. Indeed, 95% of the missing length of the legal metre was due to not taking the effect of vertical deflection into account, while wrong assumption of flattening of the Earth ellipsoid accounted for 3% of the error and the length of the meridian arc as measured by Delambre and Méchain contributed for less than 2% of the total error. Despite the precision of their survey, the definition of the metre was beyond Delambre and Méchain's reach as gravity anomalies had not yet been studied. Indeed, the geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

is a ball wich can be approximately assimilated to an ellipsoid, however meridians have such differencies from one another in shape and length that any extrapolation is impossible from only one arc measurement.

Nevertheless, in 1855, the Dufour map (French: ''Carte Dufour''), the first topographic map of Switzerland for which the metre was adopted as the unit of length, won the gold medal at the Exposition Universelle. On the sidelines of the Exposition Universelle (1855) and the second Congress of Statistics held in Paris, an association with a view to obtaining a uniform decimal system of measures, weights and currencies was created. At the initiative of this association, a Committee for Weights and Measures and Monies (French: ''Comité des poids, mesures et monnaies'') was created during the Exposition Universelle (1867)

The of 1867 (), better known in English as the 1867 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, Second French Empire, France, from 1 April to 3 November 1867. It was the List of world expositions, second of ten major expositions held i ...

in Paris and called for the international adoption of the metric system. In the United States, the Metric Act of 1866 allowed the use of the metre, and in 1867 the General Conference of the European Arc Measurement (German: ''Europäische Gradmessung'') proposed the establishment of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

.

In 1875 a number of American, Asian, African and European states concluded the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

, and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) was established at the Pavillon de Breteuil

The Pavillon de Breteuil () is a building in the southeastern section of the Parc de Saint-Cloud in Saint-Cloud, France, to the southwest of Paris. It is listed in France as a Monument historique, historic monument. Since 1875 it has been the head ...

. Until this time the metre was determined by the end-surfaces of a platinum rod (''Mètre des archives''); subsequently, rods of platinum-iridium, of cross-section X, were constructed, having engraved lines at both ends of the bridge, which determined the distance of a metre. The representation of the unit of length by means of the distance between two fine lines on the surface of a bar of metal at a certain temperature is never itself free from uncertainty and probable error, owing to the difficulty of knowing at any moment the precise temperature of the bar; and the transference of this unit, or a multiple of it, to a measuring bar will be affected not only with errors of observation, but with errors arising from uncertainty of temperature of both bars. If the measuring bar be not self-compensating for temperature, its expansion must be determined by very careful experiments. The thermometers required for this purpose must be very carefully studied, and their errors of division and index error determined.

In 1886, Adolphe Hisch, secretary of the International Committee for Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

(CIPM) and of the International Geodetic Association, proposed that all the toises that had served as geodetic standards in Europe during the 19th century be compared at the BIPM with the Toise of Peru and with the new international metre so that the measurements made until then could be used to measure the Earth. The result of these comparisons made it possible to reduce the arcs measured in Germany to the metre. The discordance of which remained between the triangles common to the German and French networks could be reduced to which was at the limit of accuracy

Accuracy and precision are two measures of ''observational error''.

''Accuracy'' is how close a given set of measurements (observations or readings) are to their ''true value''.

''Precision'' is how close the measurements are to each other.

The ...

of geodetic surveys at the time. In fact, the length of Bessel's Toise, which according to the then legal ratio between the metre and the Toise of Peru, should be equal to 1.9490348 m, would be found to be 26.2·10−6 m greater during measurements carried out by Jean-René Benoît at the BIPM. It was the consideration of the divergences between the different toises used by geodesists that led the European Arc Measurement ( ) to consider, at the meeting of its Permanent Commission in Neuchâtel

Neuchâtel (, ; ; ) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital (political), capital of the cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (canton), Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel ...

in 1866, the founding of a World Institute for the Comparison of Geodetic Standards, the first step towards the creation of the BIPM. Careful comparisons with several standard toises showed that the international metre calibrated on the '' Mètre des Archives'' was not exactly equal to the legal metre or 443.296 lines of the toise, but, in round numbers, of the length smaller, or approximately 0.013 millimetres.

In 1901, thanks to the improved accuracy of the international prototype metre

During the French Revolution, the traditional units of measure were to be replaced by consistent measures based on natural phenomena. As a base unit of length, scientists had favoured the seconds pendulum (a pendulum with a half-period of o ...

and to the work initiated in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

by Émile Plantamour under the auspices of the International Geodetic Association, Friedrich Robert Helmert would find, essentially through gravimetry

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest. The study of gravity c ...

, parameters of the Earth ellipsoid

An Earth ellipsoid or Earth spheroid is a mathematical figure approximating the Earth's form, used as a reference frame for computations in geodesy, astronomy, and the geosciences. Various different ellipsoids have been used as approximation ...

remarkably close to reality, namely a semi-major axis

In geometry, the major axis of an ellipse is its longest diameter: a line segment that runs through the center and both foci, with ends at the two most widely separated points of the perimeter. The semi-major axis (major semiaxis) is the longe ...

equal to 6 378 200 metres and a flattening of . This last value would be set at by the analysis of the first results from satellite measurements. At the Exposition Universelle (1889)

The of 1889 (), better known in English as the 1889 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 6 May to 31 October 1889. It was the fifth of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. It attracted more t ...

, The Brunner frères company exhibited a reversible pendulum designed by Gilbert Étienne Defforges. In 1892, he measured the value of gravitational acceleration

In physics, gravitational acceleration is the acceleration of an object in free fall within a vacuum (and thus without experiencing drag (physics), drag). This is the steady gain in speed caused exclusively by gravitational attraction. All bodi ...

at the BIPM. In 1901, the third General Conference on Weights and Measures

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre C ...

(CGPM) confirmed a value of 980.665 cm/s2 for the standard gravity

The standard acceleration of gravity or standard acceleration of free fall, often called simply standard gravity and denoted by or , is the nominal gravitational acceleration of an object in a vacuum near the surface of the Earth. It is a constant ...

.

The BIPM, based in Sèvres, not far from Paris, was originally responsible, under the supervision of the CIPM

The General Conference on Weights and Measures (abbreviated CGPM from the ) is the supreme authority of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the intergovernmental organization established in 1875 under the terms of the Metre ...

, for the conservation of international prototypes of measurement standards, as well as their comparison and calibration with national prototypes. However, the BIPM gradually reoriented itself towards the study of physical constant

A physical constant, sometimes fundamental physical constant or universal constant, is a physical quantity that cannot be explained by a theory and therefore must be measured experimentally. It is distinct from a mathematical constant, which has a ...

s, which are the basis of 2019 revision of the SI

In 2019, four of the seven SI base units specified in the International System of Quantities were redefined in terms of natural physical constants, rather than human artefacts such as the standard kilogram.

Effective 20 May 2019, the 144th ...

.

American cartography and the metre

In 1834, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler measured atFire Island

Fire Island is the large center island of the outer barrier islands parallel to the South Shore of Long Island in the U.S. state of New York.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy once again divided Fire Island into two islands. Together, these two isl ...

the first baseline of the Survey of the Coast. Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler's use of the metre and the creation of the Office of Standard Weights and Measures as an office within the Coast Survey contributed to the introduction of the Metric Act of 1866 allowing the use of the metre in the United States, and preceded the choice of the metre as international scientific unit of length and the proposal by the 1867 General Conference of the European Arc Measurement (German: ''Europäische Gradmessung'') to establish the International Bureau of Weights and Measures

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (, BIPM) is an List of intergovernmental organizations, intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radi ...

.

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler was a Swiss-American surveyor who is considered the forefather of both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA ) is an American scientific and regulatory agency charged with Weather forecasting, forecasting weather, monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions, Hydrography, charting the seas, ...

(NOAA) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into Outline of p ...

(NIST) for his achievements as the first Superintendent of the U.S. Survey of the Coast and the first U.S. Superintendent of Weights and Measures. The foundation of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

led to the actual definition of the metre, with Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

being the first to experimentally link the metre to the wavelength of a spectral line.

Where older traditional length measures are still used, they are now defined in terms of the metre – for example the yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English units, English unit of length in both the British imperial units, imperial and US United States customary units, customary systems of measurement equalling 3 foot (unit), feet or 36 inches. Sinc ...

has since 1959 officially been defined as exactly 0.9144 metre.

Extension of Greenwich meridian arc

In 1870, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute which he then directed until 1889. At the time it was the world's biggest geographic institute. It encompassed geodesy, general topography, leveling, cartography, statistics and the general service of weights and measures. Spain had adopted the metric system in 1849. The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of

In 1870, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero founded the Spanish National Geographic Institute which he then directed until 1889. At the time it was the world's biggest geographic institute. It encompassed geodesy, general topography, leveling, cartography, statistics and the general service of weights and measures. Spain had adopted the metric system in 1849. The Government was urged by the Spanish Royal Academy of Sciences to approve the creation of a large-scale map of Spain in 1852.

In 1865 the triangulation of Spain was connected with that of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

and France. In 1866 at the conference of the Association of Geodesy in Neuchâtel

Neuchâtel (, ; ; ) is a list of towns in Switzerland, town, a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality, and the capital (political), capital of the cantons of Switzerland, Swiss canton of Neuchâtel (canton), Neuchâtel on Lake Neuchâtel ...

, Ibáñez announced that Spain would collaborate in remeasuring and extending the French meridian arc. From 1870 to 1894, François Perrier, then Jean-Antonin-Léon Bassot proceeded to a new survey. In 1879 Ibáñez and François Perrier completed the junction between the geodetic networks of Spain and Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

and thus completed the measurement of a meridian arc which extended from Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

to the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

. This connection was a remarkable enterprise where triangles with a maximum length of 270 km were observed from mountain stations ( Mulhacén, Tetica, Filahoussen, M'Sabiha) over the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

This meridian arc was named West Europe-Africa Meridian-arc by Alexander Ross Clarke

Alexander Ross Clarke Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (1828–1914) was a British geodesist, primarily remembered for his calculation of the Principal Triangulation of Britain (1858), the calculation of the Figure of the Earth (1858, 1860, ...

and Friedrich Robert Helmert. It yielded a value for the equatorial radius of the earth ''a'' = 6 377 935 metres, the ellipticity being assumed as according to Bessel ellipsoid. The radius of curvature of this arc is not uniform, being, in the mean, about 600 metres greater in the northern than in the southern part. According to the calculations made at the central bureau of the International Geodetic Association, the net does not follow the meridian exactly, but deviates both to the west and to the east; actually, the meridian of Greenwich is nearer the mean than that of Paris.

In the 19th century, astronomers and geodesists were concerned with questions of longitude and time, because they were responsible for determining them scientifically and used them continually in their studies. The International Geodetic Association, which had covered Europe with a network of fundamental longitudes, took an interest in the question of an internationally accepted prime meridian at its seventh general conference in Rome in 1883. Indeed, the Association was already providing administrations with the bases for topographical surveys, and engineers with the fundamental benchmarks for their levelling. It seemed natural that it should contribute to the achievement of significant progress in navigation, cartography and geography, as well as in the service of major communications institutions, railways and telegraphs. From a scientific point of view, to be a candidate for the status of international prime meridian, the proponent needed to satisfy three important criteria. According to the report by Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, it must have a first-rate astronomical observatory, be directly linked by astronomical observations to other nearby observatories, and be attached to a network of first-rate triangles in the surrounding country. Four major observatories could satisfy these requirements: Greenwich, Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

and Washington. The conference concluded that Greenwich Observatory best corresponded to the geographical, nautical, astronomical and cartographic conditions that guided the choice of an international prime meridian, and recommended the governments should adopt it as the world standard. The Conference further hoped that, if the whole world agreed on the unification of longitudes and times by the Association's choosing the Greenwich meridian, Great Britain might respond in favour of the unification of weights and measures, by adhering to the Metre Convention

The Metre Convention (), also known as the Treaty of the Metre, is an international treaty that was signed in Paris on 20 May 1875 by representatives of 17 nations: Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, German Empire, Ge ...

.

See also