William Branham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Marrion Branham (April 6, 1909 – December 24, 1965) was an American Christian minister and

William M. Branham was born near

William M. Branham was born near

Branham told his audiences that he left home at age 19 in search of a better life, traveling to

Branham told his audiences that he left home at age 19 in search of a better life, traveling to  Besides Roy Davis and the First Pentecostal Baptist Church, Branham reported interaction with other groups during the 1930s who were an influence on his ministry. During the early 1930s, he became acquainted with William Sowders' School of the Prophets, a Pentecostal group in Kentucky and Indiana. Through Sowders' group, he was introduced to the

Besides Roy Davis and the First Pentecostal Baptist Church, Branham reported interaction with other groups during the 1930s who were an influence on his ministry. During the early 1930s, he became acquainted with William Sowders' School of the Prophets, a Pentecostal group in Kentucky and Indiana. Through Sowders' group, he was introduced to the

Branham took over leadership of Roy Davis's Jeffersonville church in 1934, after Davis was arrested again and extradited to stand trial. Sometime during March or April 1934, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church was destroyed by a fire and Branham's supporters at the church helped him organize a new church in Jeffersonville. At first Branham preached out of a tent at 8th and Pratt street, and he also reported temporarily preaching in an orphanage building.

By 1936, the congregation had constructed a new church on the same block as Branham's tent, at the corner of 8th and Penn street. The church was built on the same location reported by the local newspaper as the site of his June 1933 tent campaign. Newspaper articles reported the original name of Branham's new church to be the Pentecostal Tabernacle. The church was officially registered with the City of Jeffersonville as the Billie Branham Pentecostal Tabernacle in November 1936. Newspaper articles continued to refer to his church as the Pentecostal Tabernacle until 1943. Branham served as pastor until 1946, and the church name eventually shortened to the Branham Tabernacle. The church flourished at first, but its growth began to slow. Because of the

Branham took over leadership of Roy Davis's Jeffersonville church in 1934, after Davis was arrested again and extradited to stand trial. Sometime during March or April 1934, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church was destroyed by a fire and Branham's supporters at the church helped him organize a new church in Jeffersonville. At first Branham preached out of a tent at 8th and Pratt street, and he also reported temporarily preaching in an orphanage building.

By 1936, the congregation had constructed a new church on the same block as Branham's tent, at the corner of 8th and Penn street. The church was built on the same location reported by the local newspaper as the site of his June 1933 tent campaign. Newspaper articles reported the original name of Branham's new church to be the Pentecostal Tabernacle. The church was officially registered with the City of Jeffersonville as the Billie Branham Pentecostal Tabernacle in November 1936. Newspaper articles continued to refer to his church as the Pentecostal Tabernacle until 1943. Branham served as pastor until 1946, and the church name eventually shortened to the Branham Tabernacle. The church flourished at first, but its growth began to slow. Because of the

Branham had been traveling and holding revival meetings since at least 1940 before attracting national attention. Branham's popularity began to grow following the 1942 meetings in

Branham had been traveling and holding revival meetings since at least 1940 before attracting national attention. Branham's popularity began to grow following the 1942 meetings in  The first meetings organized by Lindsay were held in northwestern North America during late 1947. At the first of these meetings, held in

The first meetings organized by Lindsay were held in northwestern North America during late 1947. At the first of these meetings, held in

Branham told his audiences that he was able to determine their illness, details of their lives, and pronounce them healed as a result of an angel who was guiding him. Describing Branham's method, Bosworth said "he does not begin to pray for the healing of the afflicted in body in the healing line each night until God anoints him for the operation of the gift, and until he is conscious of the presence of the Angel with him on the platform. Without this consciousness he seems to be perfectly helpless."

Branham explained to his audiences that the angel that commissioned his ministry had given him two signs by which they could prove his commission. He described the first sign as vibrations he felt in his hand when he touched a sick person's hand, which communicated to him the nature of the illness, but did not guarantee healing. Branham's use of what his fellow evangelists called a word of knowledge gift separated him from his contemporaries in the early days of the revival.

This second sign did not appear in his campaigns until after his recovery in 1948, and was used to "amaze tens of thousands" at his meetings. As the revival progressed, his contemporaries began to mirror the practice. According to Bosworth, this gift of knowledge allowed Branham "to see and enable him to tell the many events of eople'slives from their childhood down to the present".

This caused many in the healing revival to view Branham as a "seer like the old testament prophets". Branham amazed even fellow evangelists, which served to further push him into a legendary status in the movement. Branham's audiences were often awestruck by the events during his meetings. At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation".

Branham told his audiences that he was able to determine their illness, details of their lives, and pronounce them healed as a result of an angel who was guiding him. Describing Branham's method, Bosworth said "he does not begin to pray for the healing of the afflicted in body in the healing line each night until God anoints him for the operation of the gift, and until he is conscious of the presence of the Angel with him on the platform. Without this consciousness he seems to be perfectly helpless."

Branham explained to his audiences that the angel that commissioned his ministry had given him two signs by which they could prove his commission. He described the first sign as vibrations he felt in his hand when he touched a sick person's hand, which communicated to him the nature of the illness, but did not guarantee healing. Branham's use of what his fellow evangelists called a word of knowledge gift separated him from his contemporaries in the early days of the revival.

This second sign did not appear in his campaigns until after his recovery in 1948, and was used to "amaze tens of thousands" at his meetings. As the revival progressed, his contemporaries began to mirror the practice. According to Bosworth, this gift of knowledge allowed Branham "to see and enable him to tell the many events of eople'slives from their childhood down to the present".

This caused many in the healing revival to view Branham as a "seer like the old testament prophets". Branham amazed even fellow evangelists, which served to further push him into a legendary status in the movement. Branham's audiences were often awestruck by the events during his meetings. At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation".

In January 1950, Branham's campaign team held their

In January 1950, Branham's campaign team held their

From the early days of the healing revival, Branham received overwhelmingly unfavorable coverage in the news media, which was often quite critical. At his June 1947 revivals in Vandalia, Illinois, the local news reported that Beck Walker, a man who was deaf and mute from birth, was pronounced healed but failed to recover. Branham claimed Walker failed to recover his hearing because he had disobeyed Branham's instruction to stop smoking

From the early days of the healing revival, Branham received overwhelmingly unfavorable coverage in the news media, which was often quite critical. At his June 1947 revivals in Vandalia, Illinois, the local news reported that Beck Walker, a man who was deaf and mute from birth, was pronounced healed but failed to recover. Branham claimed Walker failed to recover his hearing because he had disobeyed Branham's instruction to stop smoking

faith healer

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice. Believers assert that the healing ...

who initiated the post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

healing revival, and claimed to be a prophet with the anointing of Elijah

Elijah ( ; he, אֵלִיָּהוּ, ʾĒlīyyāhū, meaning "My God is Yahweh/YHWH"; Greek form: Elias, ''Elías''; syr, ܐܸܠܝܼܵܐ, ''Elyāe''; Arabic: إلياس or إليا, ''Ilyās'' or ''Ilyā''. ) was, according to the Books of ...

, who had come to prelude Christ's second coming; some of his followers have been labeled a "doomsday cult

A doomsday cult is a cult, that believes in apocalypticism and millenarianism, including both those that predict disaster and those that attempt to destroy the entire universe. Sociologist John Lofland coined the term ''doomsday cult'' in his ...

". He is credited as "a principal architect of restorationist

Restorationism (or Restitutionism or Christian primitivism) is the belief that Christianity has been or should be restored along the lines of what is known about the apostolic early church, which restorationists see as the search for a purer a ...

thought" for charismatics by some Christian historians, and has been called the "leading individual in the Second Wave of Pentecostalism." He made a lasting influence on televangelism

Televangelism ( tele- "distance" and "evangelism," meaning "ministry," sometimes called teleministry) is the use of media, specifically radio and television, to communicate Christianity. Televangelists are ministers, whether official or self-proc ...

and the modern charismatic movement

The charismatic movement in Christianity is a movement within established or mainstream Christian denominations to adopt beliefs and practices of Charismatic Christianity with an emphasis on baptism with the Holy Spirit, and the use of spirit ...

, and his "stage presence remains a legend unparalleled in the history of the Charismatic movement". At the time they were held, his inter-denominational meetings were the largest religious meetings ever held in some American cities. Branham was the first American deliverance minister to successfully campaign in Europe; his ministry reached global audiences with major campaigns held in North America, Europe, Africa, and India.

Branham claimed that he had received an angelic visitation on May 7, 1946, commissioning his worldwide ministry and launching his campaigning career in mid-1946. His fame rapidly spread as crowds were drawn to his stories of angelic visitations and reports of miracles happening at his meetings. His ministry spawned many emulators and set the broader healing revival that later became the modern charismatic movement

The charismatic movement in Christianity is a movement within established or mainstream Christian denominations to adopt beliefs and practices of Charismatic Christianity with an emphasis on baptism with the Holy Spirit, and the use of spirit ...

in motion. At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation". From 1955, Branham's campaigning and popularity began to decline as the Pentecostal

Pentecostalism or classical Pentecostalism is a Protestant Charismatic Christian movement

churches began to withdraw their support from the healing campaigns for primarily financial reasons. By 1960, Branham transitioned into a teaching ministry.

Unlike his contemporaries, who followed doctrinal teachings which are known as the Full Gospel The term Full Gospel or Fourfold Gospel is a theological doctrine used by some evangelical denominations that summarizes the Gospel in four aspects, namely salvation, sanctification, divine healing and second coming of Christ.

Doctrine

This term ...

tradition, Branham developed an alternative theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

which was primarily a mixture of Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

and Arminian

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Re ...

doctrines, and had a heavy focus on dispensationalism

Dispensationalism is a system that was formalized in its entirety by John Nelson Darby. Dispensationalism maintains that history is divided into multiple ages or "dispensations" in which God acts with humanity in different ways. Dispensationali ...

and Branham's own unique eschatological

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that negati ...

views. While widely accepting the restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

doctrine he espoused during the healing revival, his divergent post-revival teachings were deemed increasingly controversial by his charismatic and Pentecostal contemporaries, who subsequently disavowed many of the doctrines as "revelatory madness". His racial teachings on serpent seed

The doctrine of the serpent seed, also known as the dual-seed or the two-seedline doctrine, is a controversial and fringe Christian religious belief which explains the biblical account of the fall of man by stating that the Serpent mated with Eve ...

and his belief that membership in a Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity that comprises all church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadership, theological doctrine, worsh ...

was connected to the mark of the beast

The number of the beast ( grc-koi, Ἀριθμὸς τοῦ θηρίου, ) is associated with the Beast of Revelation in chapter 13, verse 18 of the Book of Revelation. In most manuscripts of the New Testament and in English translations of t ...

alienated many of his former supporters. His closest followers, however, accepted his sermons as oral scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

and refer to his teachings as The Message. Despite Branham's objections, some followers of his teachings placed him at the center of a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

during his final years. Branham claimed that he had converted over one million people during his career. His teachings continue to be promoted by the William Branham Evangelistic Association, which reported that about 2 million people received its material in 2018. Branham died following a car accident in 1965.

Throughout his healing revivals, Branham was accused of committing fraud

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compens ...

by investigative news reporters, fellow ministers, host churches, and governmental agencies. Numerous people pronounced healed died shortly thereafter, investigators discovered evidence suggesting miracles may have been staged, and Branham was found to have significantly embellished and falsified numerous stories he presented to his audiences as fact. Branham faced legal problems as a result of his practices. The governments of South Africa and Norway intervened in order to stop his healing campaigns in their countries. In the United States, Branham was charged with tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the taxp ...

for failing to account for the donations received through his ministry; admitting his liability, he settled the case out of court. The news media has linked Branham to multiple notorious figures. Branham was baptized and ordained a minister by Roy Davis, the National Imperial Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The t ...

(leader) of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

; the two men maintained a lifelong relationship. Branham helped launch and popularize the ministry of Jim Jones

James Warren Jones (May 13, 1931 – November 18, 1978) was an American preacher, political activist and mass murderer. He led the Peoples Temple, a new religious movement, between 1955 and 1978. In what he called "revolutionary suicide", ...

. Paul Schäfer

Paul Schäfer Schneider (4 December 1921 – 24 April 2010) was a Nazi, child rapist, German-Chilean Christian minister and the founder and leader of a sect and agricultural commune of 300 German immigrants called Colonia Dignidad (''Dignity C ...

, Robert Martin Gumbura, Leo Mercer, and other followers of William Branham's teachings have regularly been in the news due to the serious crimes which they committed. Followers of Branham's teachings in Colonia Dignidad

Colonia Dignidad ("Dignity Colony") was an isolated colony of Germans established in post-World War II Chile by emigrant Germans which became notorious for the internment, torture, and murder of dissidents during the military dictatorship of G ...

were portrayed in the 2015 film '' Colonia''.

Early life

Childhood

William M. Branham was born near

William M. Branham was born near Burkesville, Kentucky

Burkesville is a home rule-class city in Cumberland County, Kentucky, in the United States. Nestled among the rolling foothills of Appalachia and bordered by the Cumberland River to the south and east, it is the seat of its county. The population ...

, on April 6, 1909, the son of Charles and Ella Harvey Branham, the oldest of ten children. He claimed that at his birth, a "Light come whirling through the window, about the size of a pillow, and circled around where I was, and went down on the bed". Branham told his publicist Gordon Lindsay

James Gordon Lindsay (June 18, 1906 – April 1, 1973) was a revivalist preacher, author, and founder of Christ for the Nations Institute. Born in Zion, Illinois, Lindsay's parents were disciples of John Alexander Dowie, the father of healing r ...

that he had mystical experiences from an early age; and that at age three he heard a "voice" speaking to him from a tree telling him "he would live near a city called New Albany". According to Branham, that year his family moved to Jeffersonville, Indiana

Jeffersonville is a city and the county seat of Clark County, Indiana, Clark County, Indiana, United States, situated along the Ohio River. Locally, the city is often referred to by the abbreviated name Jeff. It lies directly across the Ohio River ...

. Branham also said that when he was seven years old, God told him to avoid smoking and drinking alcoholic beverages. Branham stated he never violated the command.

Branham told his audiences that he grew up in "deep poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse social, economic, and political causes and effects. When evaluating poverty in ...

", often not having adequate clothing, and that his family was involved in criminal activities. Branham's neighbors reported him as "someone who always seemed a little different", but said he was a dependable youth. Branham explained that his tendency towards "mystical experiences and moral purity" caused misunderstandings among his friends, family, and other young people; he was a "black sheep

In the English language, black sheep is an idiom that describes a member of a group who is different from the rest, especially a family member who does not fit in. The term stems from sheep whose fleece is colored black rather than the more comm ...

" from an early age. Branham called his childhood "a terrible life."

Branham's father owned a farm near Utica, Indiana

Utica is a town in Utica Township, Clark County, Indiana, United States. The population was 776 at the 2010 census.

History

From 1794 to 1825, Utica was a popular ferry crossing, as ferry crossings were considered too dangerous at Jeffersonvill ...

and took a job working for O.H. Wathen, owner of R.E. Wathen Distilleries in nearby Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

. Wathen was a supplier for Al Capone

Alphonse Gabriel Capone (; January 17, 1899 – January 25, 1947), sometimes known by the nickname "Scarface", was an American gangster and businessman who attained notoriety during the Prohibition era as the co-founder and boss of the ...

's bootlegging operations. Branham told his audiences that he was required to help his father with the illegal production and sale of liquor during prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

. In March 1924, Branham's father was arrested for his criminal activities; he was convicted and sentenced to a prison. The Indiana Ku Klux Klan

The Indiana Klan was a branch of the Ku Klux Klan, a secret society in the United States that organized in 1915 to promote ideas of racial superiority and affect public affairs on issues of Prohibition, education, political corruption, and morali ...

claimed responsibility for attacking and shutting down the Jeffersonville liquor producing ring.

Branham was involved in a firearms incident and was shot in both legs in March 1924, at age 14; he later told his audiences he was involved in a hunting accident. Two of his brothers also suffered life-threatening injuries at the same time. Branham was rushed to the hospital for treatment. His family was unable to pay for his medical bills, but members of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan

The Indiana Klan was a branch of the Ku Klux Klan, a secret society in the United States that organized in 1915 to promote ideas of racial superiority and affect public affairs on issues of Prohibition, education, political corruption, and morali ...

stepped in to cover the expenses. The help of the Klan during his impoverished childhood had a profound impact on Branham throughout his life. As late as 1963, Branham continued to speak highly of the them saying, "the Ku Klux Klan, paid the hospital bill for me, Masons. I can never forget them. See? No matter what they do, or what, I still... there is something, and that stays with me..." Branham would go on to maintain lifelong connections to the KKK.

Conversion and early influences

Branham told his audiences that he left home at age 19 in search of a better life, traveling to

Branham told his audiences that he left home at age 19 in search of a better life, traveling to Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ; nv, Hoozdo; es, Fénix or , yuf-x-wal, Banyà:nyuwá) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities and towns in Arizona#List of cities and towns, most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona, with 1 ...

, where he worked on a ranch for two years and began a successful career in boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

. While Branham was away, his brother Edward aged 18, shot and killed a Jeffersonville man and was charged with murder. Edward died of a sudden illness only a short time later. Branham returned to Jeffersonville in June 1929 to attend the funeral. Branham had no experience with religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

as a child; he said that the first time he heard a prayer was at his brother's funeral.

Soon afterward, while he was working for the Public Service Company of Indiana, Branham was overcome by gas and had to be hospitalized. Branham said that he heard a voice speaking to him while he was recovering from the accident, which led him to begin seeking God. Shortly thereafter, he began attending the First Pentecostal Baptist Church of Jeffersonville, where he converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. The church was pastored by Roy Davis, a founding member of the second Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

and a leading recruiter for the organization. Davis later became the National Imperial Wizard (leader) of the KKK. Davis baptized Branham and six months later, he ordained Branham as an Independent Baptist

Independent Baptist churches (some also called Independent Fundamental Baptist or IFB) are Christian congregations, generally holding to conservative (primarily fundamentalist) Baptist beliefs. Although some Independent Baptist churches refuse af ...

minister and an elder in his church. Supported by the KKK's Imperial Kludd (chaplain) Caleb Ridley, Branham traveled with Davis and they participated together in revivals in other states.

At the time of Branham's conversion, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church of Jeffersonville was a nominally Baptist church which adhered to some Pentecostal doctrines, including divine healing

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice. Believers assert that the healing ...

and speaking in tongues

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is a practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid vocalizing of sp ...

; Branham reported that his baptism at the church was done using the Jesus name formula of Oneness Pentecostalism

Oneness Pentecostalism (also known as Apostolic, Jesus' Name Pentecostalism, or the Jesus Only movement) is a nontrinitarian religious movement within the Protestant Christian family of churches known as Pentecostalism. It derives its distinct ...

. Branham claimed to have been opposed to Pentecostalism during the early years of his ministry. However, according to multiple Branham biographers, like Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

historian Doug Weaver

Douglas W. Weaver (born October 15, 1930) is a former American football player, coach, and college athletics administrator. He served as the head football coach at Kansas State University from 1960 to 1966 and at Southern Illinois University Carb ...

and Pentecostal historian Bernie Wade, Branham was exposed to Pentecostal teachings from his conversion.

Branham claimed to his audiences he was first exposed to a Pentecostal church in 1936, which invited him to join, but he refused. Weaver speculated that Branham may have chosen to hide his early connections to Pentecostalism to make his conversion story more compelling to his Pentecostal audiences during the years of the healing revival. Weaver identified several parts of Branham's reported life story that conflicted with historical documentation and suggested Branham began significantly embellished his early life story to his audiences beginning in the 1940s.

During June 1933, Branham held tent revival meetings that were sponsored by Davis and the First Pentecostal Baptist Church. On June 2 that year, the '' Jeffersonville Evening News'' said the Branham campaign reported 14 converts. His followers believed his ministry was accompanied by miraculous signs from its beginning, and that when he was baptizing converts on June 11, 1933, in the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

near Jeffersonville, a bright light descended over him and that he heard a voice say, "As John the Baptist was sent to forerun the first coming of Jesus Christ, so your message will forerun His second coming".

Belief in the baptismal story is a critical element of faith among Branham's followers. In his early references to the event during the healing revival, Branham interpreted it to refer to the restoration of the gifts of the spirit

A spiritual gift or charism (plural: charisms or charismata; in Greek singular: χάρισμα

''charisma'', plural: χαρίσματα ''charismata'') is an extraordinary power given by the Holy Spirit."Spiritual gifts". ''A Dictionary of the ...

to the church. In later years, Branham significantly altered how he told the baptismal story, and came to connect the event to his teaching ministry. He claimed reports of the baptismal story were carried in newspapers across the United States and Canada. Because of the way Branham's telling of the baptismal story changed over the years, and because no newspaper actually covered the event, Weaver said Branham may have embellished the story after he began achieving success in the healing revival during the 1940s.

Besides Roy Davis and the First Pentecostal Baptist Church, Branham reported interaction with other groups during the 1930s who were an influence on his ministry. During the early 1930s, he became acquainted with William Sowders' School of the Prophets, a Pentecostal group in Kentucky and Indiana. Through Sowders' group, he was introduced to the

Besides Roy Davis and the First Pentecostal Baptist Church, Branham reported interaction with other groups during the 1930s who were an influence on his ministry. During the early 1930s, he became acquainted with William Sowders' School of the Prophets, a Pentecostal group in Kentucky and Indiana. Through Sowders' group, he was introduced to the British Israelite

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is the British nationalism, British nationalist, Pseudoarchaeology, pseudoarchaeological, Pseudohistory, pseudohistorical and Pseudoreligion, pseudoreligious belief that the people of Great Britai ...

House of David and in the autumn of 1934, Branham traveled to Michigan to meet with members of the group.

Early ministry

Branham took over leadership of Roy Davis's Jeffersonville church in 1934, after Davis was arrested again and extradited to stand trial. Sometime during March or April 1934, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church was destroyed by a fire and Branham's supporters at the church helped him organize a new church in Jeffersonville. At first Branham preached out of a tent at 8th and Pratt street, and he also reported temporarily preaching in an orphanage building.

By 1936, the congregation had constructed a new church on the same block as Branham's tent, at the corner of 8th and Penn street. The church was built on the same location reported by the local newspaper as the site of his June 1933 tent campaign. Newspaper articles reported the original name of Branham's new church to be the Pentecostal Tabernacle. The church was officially registered with the City of Jeffersonville as the Billie Branham Pentecostal Tabernacle in November 1936. Newspaper articles continued to refer to his church as the Pentecostal Tabernacle until 1943. Branham served as pastor until 1946, and the church name eventually shortened to the Branham Tabernacle. The church flourished at first, but its growth began to slow. Because of the

Branham took over leadership of Roy Davis's Jeffersonville church in 1934, after Davis was arrested again and extradited to stand trial. Sometime during March or April 1934, the First Pentecostal Baptist Church was destroyed by a fire and Branham's supporters at the church helped him organize a new church in Jeffersonville. At first Branham preached out of a tent at 8th and Pratt street, and he also reported temporarily preaching in an orphanage building.

By 1936, the congregation had constructed a new church on the same block as Branham's tent, at the corner of 8th and Penn street. The church was built on the same location reported by the local newspaper as the site of his June 1933 tent campaign. Newspaper articles reported the original name of Branham's new church to be the Pentecostal Tabernacle. The church was officially registered with the City of Jeffersonville as the Billie Branham Pentecostal Tabernacle in November 1936. Newspaper articles continued to refer to his church as the Pentecostal Tabernacle until 1943. Branham served as pastor until 1946, and the church name eventually shortened to the Branham Tabernacle. The church flourished at first, but its growth began to slow. Because of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, it was often short of funds, so Branham served without compensation.

Branham continued traveling and preaching among Pentecostal churches while serving as pastor of his new church. Branham obtained a truck and had it painted with advertisements for his healing ministry which he toured in. In September 1934, he traveled to Mishawaka, Indiana where he was invited to speak at the Pentecostal Assemblies of Jesus Christ (PAJC) General Assembly meetings organized by Bishop G. B. Rowe. Branham was "not impressed with the multi-cultural aspects of the PAJC as it was contrary to the dogmas advanced by his friends in the Ku Klux Klan."

Branham and his future wife Amelia Hope Brumbach (b. July 16, 1913) attended the First Pentecostal Baptist Church together beginning in 1929 where Brumbach served as young people's leader. The couple began dating in 1933. Branham married Brumbach in June 1934. Their first child, William "Billy" Paul Branham was born soon after their marriage; the date given for his birth varies by source. In some of Branham's biographies, his first son's birth date is reported as September 13, 1935, but in government records his birth date is reported as September 13, 1934. Branham's wife became ill during the second year of their marriage. According to her death certificate, she was diagnosed with pulmonary

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of th ...

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in January 1936, beginning a period of declining health. Despite her diagnosis, the couple had a second child, Sharon Rose, who was born on October 27, 1936. In September 1936, the local news reported that Branham held a multi-week healing revival at the Pentecostal Tabernacle in which he reported eight healings.

The following year, disaster struck when Jeffersonville was ravaged by the Ohio River flood of 1937

The Ohio River flood of 1937 took place in late January and February 1937. With damage stretching from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Illinois, 385 people died, one million people were left homeless and property losses reached $500 million ($10.2 billion ...

. Branham's congregation was badly impacted by the disaster and his family was displaced from their home. By February 1937, the floodwaters had receded, his church survived intact and Branham resumed holding services at the Pentecostal Tabernacle. Following the January flood, Hope's health continued to decline, and she succumbed to her illness and died on July 22, 1937. Sharon Rose, who had been born with her mother's illness, died four days later (July 26, 1937). Their obituaries reported Branham as pastor of the Pentecostal Tabernacle, the same church where their funerals were held.

Branham frequently related the story of the death of his wife and daughter during his ministry and evoked strong emotional responses from his audiences. Branham told his audiences that his wife and daughter had become suddenly ill and died during the January flood as God's punishment because of his failure to embrace Pentecostalism. Branham said he made several suicide attempts following their deaths. Peter Duyzer noted that Branham's story of the events surrounding the death of his wife and daughter conflicted with historical evidence; they did not die during the flood, he and his wife were both already Pentecostals before they married, and he was pastor of a Pentecostal church at the time of their deaths.

By the summer of 1940, Branham had resumed traveling and held revival meetings in other nearby communities. Branham married his second wife Meda Marie Broy in 1941, and together they had three children; Rebekah (b. 1946), Sarah (b. 1950), and Joseph (b. 1955).

Healing revival

Background

Branham is known for his role in the healing revivals that occurred in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s, and most participants in the movement regarded him as its initiator. Christian writer John Crowder described the period of revivals as "the most extensive public display of miraculous power in modern history". Some, like Christian author and countercult activistHank Hanegraaff

Hendrik "Hank" Hanegraaff (born 1950), also known as the "Bible Answer Man", is an American Christian author and radio talk-show host. Formerly an evangelical Protestant, he joined the Eastern Orthodox Church in 2017. He is an outspoken figure wi ...

, rejected the entire healing revival as a hoax and condemned the movement as cult in his 1997 book ''Counterfeit Revival''.

Divine healing is a tradition and belief that was historically held by a majority of Christians but it became increasingly associated with Evangelical Protestantism. The fascination of most of American Christianity with divine healing played a significant role in the popularity and inter-denominational nature of the revival movement.

Branham held massive inter-denominational meetings, from which came reports of hundreds of miracles. Historian David Harrell described Branham and Oral Roberts

Granville Oral Roberts (January 24, 1918 – December 15, 2009) was an American Charismatic Christianity, Charismatic Christianity, Christian televangelist, ordained in both the International Pentecostal Holiness Church, Pentecostal Holin ...

as the two giants of the movement and called Branham its "unlikely leader."

Early campaigns

Branham had been traveling and holding revival meetings since at least 1940 before attracting national attention. Branham's popularity began to grow following the 1942 meetings in

Branham had been traveling and holding revival meetings since at least 1940 before attracting national attention. Branham's popularity began to grow following the 1942 meetings in Milltown, Indiana

Milltown is a town in Blue River Township, Harrison County, Indiana, Blue River and Spencer Township, Harrison County, Indiana, Spencer townships in Harrison County, Indiana, Harrison County and Whiskey Run Township, Crawford County, Indiana, Whisk ...

where it was reported that a young girl had been healed of tuberculosis. The news of the reported healing was slow to spread, but was eventually reported to a family in Missouri who in 1945 invited Branham to pray for their child who was suffering from a similar illness; Branham reported that the child recovered after his prayers.

News of two events eventually reached W. E. Kidston. Kidston was intrigued by the reported miracles and invited Branham to participate in revival meetings that he was organizing. W. E. Kidston, was editor of ''The Apostolic Herald'' and had many contacts in the Pentecostal movement. Kidston served as Branham's first campaign manager and was instrumental in helping organize Branham's early revival meetings.

Branham held his first large meetings as a faith healer

Faith healing is the practice of prayer and gestures (such as laying on of hands) that are believed by some to elicit divine intervention in spiritual and physical healing, especially the Christian practice. Believers assert that the healing ...

in 1946. His healing services are well documented, and he is regarded as the pacesetter for those who followed him. At the time they were held, Branham's revival meetings were the largest religious meetings some American cities he visited had ever seen; reports of 1,000 to 1,500 converts per meeting were common.

Historians name his June 1946 St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

meetings as the inauguration of the healing revival period. Branham said he had received an angelic visitation on May 7, 1946, commissioning his worldwide ministry. In his later years, he also connected the angelic visitation with the establishment of the nation of Israel, at one point mistakenly stating the vision occurred on the same day.

His first reported revival meetings of the period were held over 12 days during June 1946 in St. Louis. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine reported on his St. Louis campaign meetings, and according to the article, Branham drew a crowd of over 4,000 sick people who desired healing and recorded him diligently praying for each. Branham's fame began to grow as a result of the publicity and reports covering his meetings.

''Herald of Faith'' magazine which was edited by prominent Pentecostal minister Joseph Mattsson-Boze

Joseph D. Mattsson-Boze (died January 1989) was a Swedish-American minister and pastor of Chicago's Philadelphia Church from 1933 to 1958, with the exception of 1939-1941 when he pastored the Rock Church in New York. He was publisher and editor ...

and published by Philadelphia Pentecostal Church in Chicago also began following and exclusively publishing stories from the Branham campaigns, giving Branham wide exposure to the Pentecostal movement. Following the St. Louis meetings, Branham launched a tour of small Oneness Pentecostal churches across the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

and southern United States, from which stemmed reports of healing and one report of a resurrection. By August his fame had spread widely. He held meetings that month in Jonesboro, Arkansas

Jonesboro is a city located on Crowley's Ridge in the northeastern corner of the U.S. State of Arkansas. Jonesboro is one of two county seats of Craighead County. According to the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 78,576 and is the f ...

, and drew a crowd of 25,000 with attendees from 28 different states. The size of the crowds presented a problem for Branham's team as they found it difficult to find venues that could seat large numbers of attendees.

Branham's revivals were interracial from their inception and were noted for their "racial openness" during the period of widespread racial unrest. An African American minister participating in the St. Louis meetings claimed to be healed during the revival, helping to bring Branham a sizable African American following from the early days of the revival. Branham held interracial meetings even in the southern states. To satisfy segregation laws when ministering in the south, Branham's team would use a rope to divide the crowd by race.

Author and researcher Patsy Sims noted that venues used to host campaign meetings also hosted KKK rallies just days prior to the revival meetings, which sometimes led to racial tensions. Sims, who attended both the KKK rallies and the healing revivals, was surprised to see some of the same groups of people at both events. According to Steven Hassan

Steven Alan Hassan (pronounced ; born 1953) is an American author, educator and mental health counselor specializing in destructive cults (sometimes called exit counseling). He has been described by media as "one of the world's foremost experts ...

, KKK recruitment was covertly conducted through Branham's ministry.

After holding a very successful revival meeting in Shreveport

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population o ...

during mid-1947, Branham began assembling an evangelical team that stayed with him for most of the revival period. The first addition to the team was Jack Moore and Young Brown, who periodically assisted him in managing his meetings. Following the Shreveport meetings, Branham held a series of meetings in San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= U.S. state, State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, s ...

, Phoenix, and at various locations in California. Moore invited his friend Gordon Lindsay to join the campaign team, which he did beginning at a meeting in Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

, in late 1947.

Lindsay was a successful publicist and manager for Branham, and played a key role in helping him gain national and international recognition. In 1948, Branham and Lindsay founded ''Voice of Healing

James Gordon Lindsay (June 18, 1906 – April 1, 1973) was a revivalist preacher, author, and founder of Christ for the Nations Institute. Born in Zion, Illinois, Lindsay's parents were disciples of John Alexander Dowie, the father of healing r ...

'' magazine, which was originally aimed at reporting Branham's healing campaigns. The story of Samuel the Prophet, who heard a voice speak to him in the night, inspired Branham's name for the publication. Lindsay was impressed with Branham's focus on humility and unity, and was instrumental in helping him gain acceptance among Trinitarian

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the Fa ...

and Oneness Pentecostal groups by expanding his revival meetings beyond the United Pentecostal Church

The United Pentecostal Church International (UPCI) is a Oneness Pentecostal denomination headquartered in Weldon Spring, Missouri, United States. The United Pentecostal Church International was formed in 1945 by a merger of the former Pentecostal C ...

to include all of the major Pentecostal groups.

The first meetings organized by Lindsay were held in northwestern North America during late 1947. At the first of these meetings, held in

The first meetings organized by Lindsay were held in northwestern North America during late 1947. At the first of these meetings, held in Vancouver, British Columbia

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

, Canadian minister Ern Baxter

William John Ernest (Ern) Baxter (1914–1993) was a Canadian Pentecostal evangelist.

Early life

Born in Saskatchewan, Canada, he was baptised into a Presbyterian family. His mother was involved with a holiness church and following his father’ ...

joined Branham's team. Lindsay reported 70,000 attendees to the 14 days of meetings and long prayer lines as Branham prayed for the sick. William Hawtin, a Canadian Pentecostal minister, attended one of Branham's Vancouver meetings in November 1947 and was impressed by Branham's healings. Branham was an important influence on the Latter Rain revival movement, which Hawtin helped initiate.

In January 1948, meetings were held in Florida; F. F. Bosworth met Branham at the meetings and also joined his team. Bosworth was among the pre-eminent ministers of the Pentecostal movement and a founding ministers of the Assemblies of God

The Assemblies of God (AG), officially the World Assemblies of God Fellowship, is a group of over 144 autonomous self-governing national groupings of churches that together form the world's largest Pentecostal denomination."Assemblies of God". ...

; Bosworth lent great weight to Branham's campaign team. He remained a strong Branham supporter until his death in 1958. Bosworth endorsed Branham as "the most sensitive person to the presence and working of the Holy Spirit" he had ever met.

During early 1947, a major campaign was held in Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more ...

, where Branham and Lindsay first met Oral Roberts. Roberts and Branham had contact at different points during the revival. Roberts said Branham was "set apart, just like Moses".

Branham spent many hours ministering and praying for the sick during his campaigns, and like many other leading evangelists of the time he suffered exhaustion

Fatigue describes a state of tiredness that does not resolve with rest or sleep. In general usage, fatigue is synonymous with extreme tiredness or exhaustion that normally follows prolonged physical or mental activity. When it does not resolve ...

. After one year of campaigning, his exhaustion began leading to health issues. Branham reported to his audiences that he suffered a nervous breakdown and required treatment by the Mayo Clinic

The Mayo Clinic () is a nonprofit American academic medical center focused on integrated health care, education, and research. It employs over 4,500 physicians and scientists, along with another 58,400 administrative and allied health staff, ...

. Branham's illness coincided with a series of allegations of fraud in his healing revivals. Attendees reported seeing him "staggering from intense fatigue" during his last meetings.

Just as Branham began to attract international attention in May 1948, he announced that due to illness he would have to halt his campaign. His illness shocked the growing movement, and his abrupt departure from the field caused a rift between him and Lindsay over the ''Voice of Healing'' magazine. Branham insisted that Lindsay take over complete management of the publication. With the main subject of the magazine no longer actively campaigning, Lindsay was forced to seek other ministers to promote. He decided to publicize Oral Roberts during Branham's absence, and Roberts quickly rose to prominence, in large part due to Lindsay's coverage.

Branham partially recovered from his illness and resumed holding meetings in October 1948; in that month he held a series of meetings around the United States without Lindsay's support. Branham's return to the movement led to his resumed leadership of it. In November 1948, he met with Lindsay and Moore and told them he had received another angelic visitation, instructing him to hold a series of meetings across the United States and then to begin holding meetings internationally. As a result of the meeting, Lindsay rejoined Branham's campaigning team.

Style

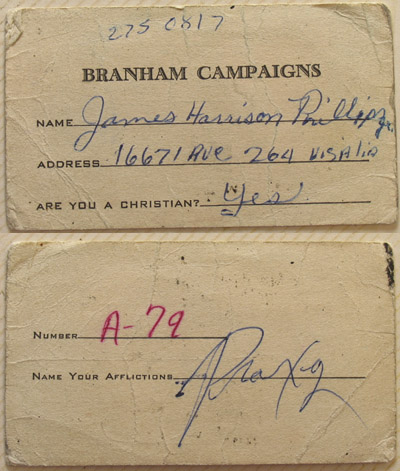

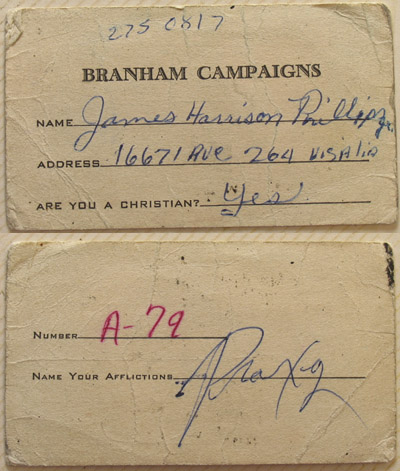

Most revivalists of the era were flamboyant but Branham was usually calm and spoke quietly, only occasionally raising his voice. His preaching style was described as "halting and simple", and crowds were drawn to his stories of angelic visitation and "constant communication with God". Branham tailored his language usage to best connect to his audiences. When speaking to poor and working-class audiences, he tended to use poor grammar and folksy language; when speaking to more educated audiences and ministerial associations, he generally spoke using perfect grammar and avoided slang usage. He refused to discuss controversial doctrinal issues during the healing campaigns, and issued a policy statement that he would only minister on the "great evangelical truths". He insisted his calling was to bring unity among the different churches he was ministering to and to urge the churches to return to the roots of early Christianity. In the first part of his meetings, one of Branham's companion evangelists would preach a sermon. Ern Baxter or F. F. Bosworth usually filled this role, but other ministers like Paul Cain also participated in Branham's campaigns in later years. Baxter generally focused on bible teaching; Bosworth counseled supplicants on the need for faith and the doctrine of divine healing. Following their build-up, Branham would take the podium and deliver a short sermon, in which he usually related stories about his personal life experiences. Branham would often request God to "confirm his message with two-or-three faith inspired miracles". Supplicants seeking healing submitted prayer cards to Branham's campaign team stating their name, address, and condition; Branham's team would select a number of submissions to be prayed for personally by Branham and organized a prayer line. After completing his sermon, he would proceed with the prayer line where he would pray for the sick. Branham would often tell supplicants what they suffered from, their name, and their address. He would pray for each of them, pronouncing some or all healed. Branham generally prayed for a few people each night and believed witnessing the results on the stage would inspire faith in the audience and permit them to experience similar results without having to be personally prayed for. Branham would also call out a few members still in the audience, who had not been accepted into the prayer line, stating their illness and pronouncing them healed. Branham told his audiences that he was able to determine their illness, details of their lives, and pronounce them healed as a result of an angel who was guiding him. Describing Branham's method, Bosworth said "he does not begin to pray for the healing of the afflicted in body in the healing line each night until God anoints him for the operation of the gift, and until he is conscious of the presence of the Angel with him on the platform. Without this consciousness he seems to be perfectly helpless."

Branham explained to his audiences that the angel that commissioned his ministry had given him two signs by which they could prove his commission. He described the first sign as vibrations he felt in his hand when he touched a sick person's hand, which communicated to him the nature of the illness, but did not guarantee healing. Branham's use of what his fellow evangelists called a word of knowledge gift separated him from his contemporaries in the early days of the revival.

This second sign did not appear in his campaigns until after his recovery in 1948, and was used to "amaze tens of thousands" at his meetings. As the revival progressed, his contemporaries began to mirror the practice. According to Bosworth, this gift of knowledge allowed Branham "to see and enable him to tell the many events of eople'slives from their childhood down to the present".

This caused many in the healing revival to view Branham as a "seer like the old testament prophets". Branham amazed even fellow evangelists, which served to further push him into a legendary status in the movement. Branham's audiences were often awestruck by the events during his meetings. At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation".

Branham told his audiences that he was able to determine their illness, details of their lives, and pronounce them healed as a result of an angel who was guiding him. Describing Branham's method, Bosworth said "he does not begin to pray for the healing of the afflicted in body in the healing line each night until God anoints him for the operation of the gift, and until he is conscious of the presence of the Angel with him on the platform. Without this consciousness he seems to be perfectly helpless."

Branham explained to his audiences that the angel that commissioned his ministry had given him two signs by which they could prove his commission. He described the first sign as vibrations he felt in his hand when he touched a sick person's hand, which communicated to him the nature of the illness, but did not guarantee healing. Branham's use of what his fellow evangelists called a word of knowledge gift separated him from his contemporaries in the early days of the revival.

This second sign did not appear in his campaigns until after his recovery in 1948, and was used to "amaze tens of thousands" at his meetings. As the revival progressed, his contemporaries began to mirror the practice. According to Bosworth, this gift of knowledge allowed Branham "to see and enable him to tell the many events of eople'slives from their childhood down to the present".

This caused many in the healing revival to view Branham as a "seer like the old testament prophets". Branham amazed even fellow evangelists, which served to further push him into a legendary status in the movement. Branham's audiences were often awestruck by the events during his meetings. At the peak of his popularity in the 1950s, Branham was widely adored and "the neo-Pentecostal world believed Branham to be a prophet to their generation".

Growing fame and international campaigns

In January 1950, Branham's campaign team held their

In January 1950, Branham's campaign team held their Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

campaign, one of the most significant series of meetings of the revival. The location of their first meeting was too small to accommodate the approximately 8,000 attendees, and they had to relocate to the Sam Houston Coliseum

Sam Houston Coliseum was an indoor arena located in Houston, Texas.

Early years

Located at 801 Bagby Street in Downtown Houston, the Coliseum and Music Hall complex replaced the Sam Houston Hall, which was a wooden structure that had been erected ...

. On the night of January 24, 1950, Branham was photographed during a debate between Bosworth and local Baptist minister W. E. Best regarding the theology of divine healing.

Bosworth argued in favor, while Best argued against. The photograph showed a light above Branham's head, which he and his associates believed to be supernatural. The photograph became well-known in the revival movement and is regarded by Branham's followers as an iconic relic. Branham believed the light was a divine vindication of his ministry; others believed it was a glare from the venue's overhead lighting.

In January 1951, former US Congressman William Upshaw

William David Upshaw (October 15, 1866 – November 21, 1952) served eight years in Congress (1919–1927), where he was such a strong proponent of the temperance movement that he became known as the "driest of the drys." In Congress, Upshaw ...

was sent by Roy Davis to a Branham campaign meeting in California. Upshaw had limited mobility for 59 years as the result of an accident, and said he was miraculously healed in the meeting. The publicity of the event took Branham's fame to a new level. Upshaw sent a letter describing his healing claim to each member of Congress. The ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

'' reported on the healing in an article titled "Ex-Rep. Upshaw Discards Crutches After 59 Years". Upshaw explained to reporters that he had already been able to walk without the aid of his crutches prior to attending Branham's meeting, but following Branham's prayer his strength increased so that he could walk much longer distances unaided. Upshaw died in November 1952, at the age of 86.

According to Pentecostal historian Rev. Walter Hollenweger

Walter Jacob Hollenweger (born 1927 in Antwerp; died 10 August 2016) was a Swiss theologian, recognized as an expert on worldwide Pentecostalism. His two best known books are ''The Pentecostals'' (1972) and ''Pentecostalism: Origins and Development ...

, "Branham filled the largest stadiums and meeting halls in the world" during his five major international campaigns. Branham held his first series of campaigns in Europe during April 1950 with meetings in Finland, Sweden, and Norway. Attendance at the meetings generally exceeded 7,000 despite resistance to his meetings by the state churches. Branham was the first American deliverance minister to successfully tour in Europe.

A 1952 campaign in South Africa had the largest attendance in Branham's career, with an estimated 200,000 attendees. According to Lindsay, the altar call at his Durban meeting received 30,000 converts. During international campaigns in 1954, Branham visited Portugal, Italy, and India. Branham's final major overseas tour in 1955 included visits to Switzerland and Germany.

Branham's meetings were regularly attended by journalists, who wrote articles about the miracles reported by Branham and his team throughout the years of his revivals, and claimed patients were cured of various ailments after attending prayer meetings with Branham. ''Durban Sunday Tribune'' and ''The Natal Mercury

''The Mercury'', formerly ''The Natal Mercury'', is an English-language newspaper owned by Independent Media (Pty) Ltd, a subsidiary of Iqbal Survé’s Sekunjalo Investments and published in Durban, South Africa.

Content

The paper focus ...

'' reported wheelchair-bound people rising and walking. ''Winnipeg Free Press

The ''Winnipeg Free Press'' (or WFP; founded as the ''Manitoba Free Press'') is a daily (excluding Sunday) broadsheet newspaper in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. It provides coverage of local, provincial, national, and international news, as well as ...

'' reported a girl was cured of deafness. ''El Paso Herald-Post

The ''El Paso Herald-Post'' was an afternoon daily newspaper in El Paso, Texas, USA. It was the successor to the El Paso Herald, first published in 1881, and the El Paso Post, founded by the E. W. Scripps Company in 1922. The papers merged in 19 ...

'' reported hundreds of attendees at one meeting seeking divine healing. Despite such occasional glowing reports, most of the press coverage Branham received was negative.

Allegations of fraud

To his American audiences, Branham claimed several high profile events occurred during his international tours. Branham claimed to visit and pray forKing George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Ind ...

while en route to Finland in 1950. He claimed the king was healed through his prayers. Researchers found no evidence that Branham ever met King George; King George was chronically ill and died about a year after Branham claimed to heal him.

Branham also claimed to pray for and heal the granddaughter of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

at a London airport. Branham's campaign produced photos of an emaciated

Emaciation is defined as the state of extreme thinness from absence of body fat and muscle wasting usually resulting from malnutrition.

Characteristics

In humans, the physical appearance of emaciation includes thinned limbs, pronounced and protrud ...

woman who they claimed to be Nightingale's granddaughter. However, Florence Nightingale never married and had no children or grandchildren. Investigators of Branham's claim were unable to identify the woman in the photograph.

Branham similarly claimed to pray for King Gustaf V

Gustaf V (Oscar Gustaf Adolf; 16 June 1858 – 29 October 1950) was King of Sweden from 8 December 1907 until his death in 1950. He was the eldest son of King Oscar II of Sweden and Sophia of Nassau, a half-sister of Adolphe, Grand Duke of Luxem ...

while in Sweden in April 1950. Investigators found no evidence for the meeting; King Gustaf V died in October 1950. Branham claimed to stop in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

in 1954 while en route to India to meet with King Farouk

Farouk I (; ar, فاروق الأول ''Fārūq al-Awwal''; 11 February 1920 – 18 March 1965) was the tenth ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty and the penultimate King of Egypt and the Sudan, succeeding his father, Fuad I, in 193 ...

; however Farouk had been deposed in 1952 and was not living in Egypt at the time. Branham claimed to visit the grave of Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

while in India, however Buddha was cremated and has no grave. In total, critics of Branham identified many claims which appeared to be false when investigated. Weaver accused Branham of major embellishments.

Branham faced criticism and opposition from the early days of the healing revival, and he was repeatedly accused of fraud throughout his ministry. According to historian Ronald Kydd, Branham evoked strong opinions from people with whom he came into contact; "most people either loved him or hated him". Kydd stated that it "is impossible to get even an approximate number of people healed in Branham's ministry." No consistent record of follow-ups of the healing claims were made, making analysis of many claims difficult to subsequent researchers. Additionally, Branham's procedures made verification difficult at the time of his revivals. Branham believed in positive confession. He required supplicants to claim to be healed to demonstrate their faith, even if they were still experiencing symptoms. He frequently told supplicants to expect their symptoms to remain for several days after their healing. This led to people professing to be healed at the meetings, while still suffering from the condition. Only follow up after Branham's waiting period had passed could ascertain the result of the healing.

From the early days of the healing revival, Branham received overwhelmingly unfavorable coverage in the news media, which was often quite critical. At his June 1947 revivals in Vandalia, Illinois, the local news reported that Beck Walker, a man who was deaf and mute from birth, was pronounced healed but failed to recover. Branham claimed Walker failed to recover his hearing because he had disobeyed Branham's instruction to stop smoking

From the early days of the healing revival, Branham received overwhelmingly unfavorable coverage in the news media, which was often quite critical. At his June 1947 revivals in Vandalia, Illinois, the local news reported that Beck Walker, a man who was deaf and mute from birth, was pronounced healed but failed to recover. Branham claimed Walker failed to recover his hearing because he had disobeyed Branham's instruction to stop smoking cigarette

A cigarette is a narrow cylinder containing a combustible material, typically tobacco, that is rolled into thin paper for smoking. The cigarette is ignited at one end, causing it to smolder; the resulting smoke is orally inhaled via the opp ...

s. Branham was lambasted by critics who asked how it was possible the deaf man could have heard his command to stop smoking.

At his 1947 meetings in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749,6 ...

, Branham claimed to have raised a young man from the dead at a Jeffersonville funeral parlor. Branham's sensational claim was reported in the news in the United States and Canada, leading to a news media investigation to identify the funeral home and the individual raised from the dead. Reporters subsequently found no evidence of a resurrection; no funeral parlor in the city corroborated the story. The same year the news media in Winnipeg publicized Branham's cases of failed healing. In response, the churches which hosted Branham's campaign conducted independent follow-up interviews with people Branham pronounced healed to gather testimonies which they could use to counter the negative press. To their surprise, their investigation failed to confirm any cases of actual healing; every person they interviewed had failed to recover.

At meetings in Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

during 1947, newspaper reporters discovered that one young girl had been in Branham's prayer lines in multiple cities posing as a cripple, but rising to walk after Branham pronounced her healed each time. An investigative reporter suspected Branham had staged the miracle. Reporters at the meeting also attempted to follow up on the case of a Calgary woman pronounced healed by Branham who had died shortly after he left the city. Reporters attempted to confront Branham over these issues, but Branham refused to be interviewed.

Branham was also accused of fraud by fellow ministers and churches that hosted his meetings. In 1947, Rev. Alfred Pohl, the Missionary-Secretary of Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada

The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada (PAOC) (french: Les Assemblées de la Pentecôte du Canada) is a Pentecostal Christian denomination and the largest evangelical church in Canada.Regina, Branham pronounced the wife of a prominent minister healed of cancer. The minister and his wife were overjoyed, and the minister excitedly shared the details of the healing with his radio audience in

Annihilationism, the doctrine that the damned will be totally destroyed after the final judgment so as to not exist, was introduced to Pentecostalism in the teachings of

Annihilationism, the doctrine that the damned will be totally destroyed after the final judgment so as to not exist, was introduced to Pentecostalism in the teachings of

His most significant prophecies were a series of prophetic visions he claimed to have in June 1933. The first time he published any information about the visions were in 1953. Branham reported that in his visions he saw seven major events would occur before the

His most significant prophecies were a series of prophetic visions he claimed to have in June 1933. The first time he published any information about the visions were in 1953. Branham reported that in his visions he saw seven major events would occur before the

Branham continued to travel to churches and preach his doctrine across Canada, the United States, and Mexico during the 1960s. His only overseas trip during the 1960s proved a disappointment. Branham reported a vision of himself preaching before large crowds and hoped for its fulfillment on the trip, but the South African government prevented him from holding revivals when he traveled to the country in 1965. Branham was saddened that his teaching ministry was rejected by all but his closest followers.

Pentecostal churches which once welcomed Branham refused to permit him to preach during the 1960s, and those who were still sympathetic to him were threatened with excommunication by their superiors if they did so. He held his final set of revival meetings in Shreveport at the church of his early campaign manager Jack Moore in November 1965. Although he had hinted at it many times, Branham publicly stated for the first time that he was the return of Elijah the prophet in his final meetings in Shreveport.

On December 18, 1965, Branham and his familyexcept his daughter Rebekahwere returning to Jeffersonville, Indiana, from Tucson for the Christmas holiday. About east of

Branham continued to travel to churches and preach his doctrine across Canada, the United States, and Mexico during the 1960s. His only overseas trip during the 1960s proved a disappointment. Branham reported a vision of himself preaching before large crowds and hoped for its fulfillment on the trip, but the South African government prevented him from holding revivals when he traveled to the country in 1965. Branham was saddened that his teaching ministry was rejected by all but his closest followers.

Pentecostal churches which once welcomed Branham refused to permit him to preach during the 1960s, and those who were still sympathetic to him were threatened with excommunication by their superiors if they did so. He held his final set of revival meetings in Shreveport at the church of his early campaign manager Jack Moore in November 1965. Although he had hinted at it many times, Branham publicly stated for the first time that he was the return of Elijah the prophet in his final meetings in Shreveport.