While the

Tibetan plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the ...

has been inhabited since pre-historic times, most of

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

's history went unrecorded until the introduction of

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

around the 6th century. Tibetan texts refer to the kingdom of

Zhangzhung

Zhangzhung or Shangshung was an ancient culture and kingdom in western and northwestern Tibet, which pre-dates the culture of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. Zhangzhung culture is associated with the Bon religion, which has influenced the philosophie ...

(c. 500 BCE – 625 CE) as the precursor of later Tibetan kingdoms and the originators of the

Bon

''Bon'', also spelled Bön () and also known as Yungdrung Bon (, "eternal Bon"), is a Tibetan religious tradition with many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism and also many unique features.Samuel 2012, pp. 220-221. Bon initially developed in t ...

religion. While mythical accounts of early rulers of the

Yarlung Dynasty exist, historical accounts begin with the introduction of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

from India in the 6th century and the appearance of envoys from the unified Tibetan Empire in the 7th century. Following the dissolution of the empire and a period of fragmentation in the 9th-10th centuries, a Buddhist revival in the 10th–12th centuries saw the development of three of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

After a period of control by the

Mongol Empire and

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

, Tibet became effectively independent in the 14th century and was ruled by a succession of noble houses for the next 300 years. In the 17th century, the senior lama of the

Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous")Kay, David N. (2007). ''Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantati ...

school, the

Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

, became the head of state with the aid of the

Khoshut Khanate

The Khoshut Khanate was a Mongol Oirat khanate based on the Tibetan Plateau from 1642 to 1717. Based in modern Qinghai, it was founded by Güshi Khan in 1642 after defeating the opponents of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. The r ...

. In the early 18th century, the

Dzungar Khanate

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from t ...

occupied Tibet and a

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

expeditionary force attacked them, conquering Tibet in 1720. It remained a Qing territory until the fall of the dynasty. In 1959, the

14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (spiritual name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, known as Tenzin Gyatso (Tibetan: བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: ''bsTan-'dzin rgya-mtsho''); né Lhamo Thondup), known as ...

went into exile in India in response to hostilities with the PRC. The Chinese invasion and flight of the Dalai Lama created several waves of Tibetan refugees and led to the creation of Tibetan diasporas in India, the United States, and Europe.

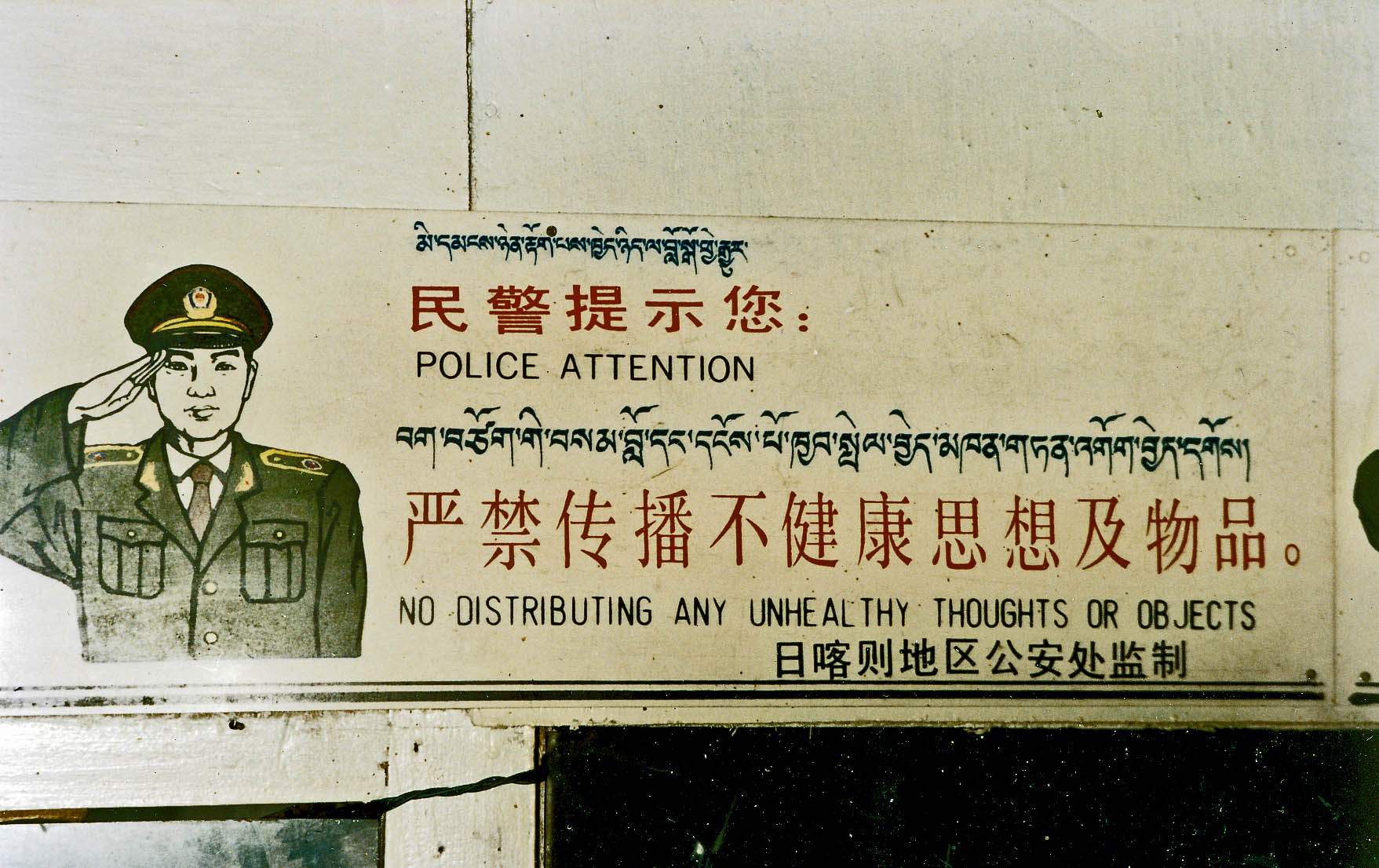

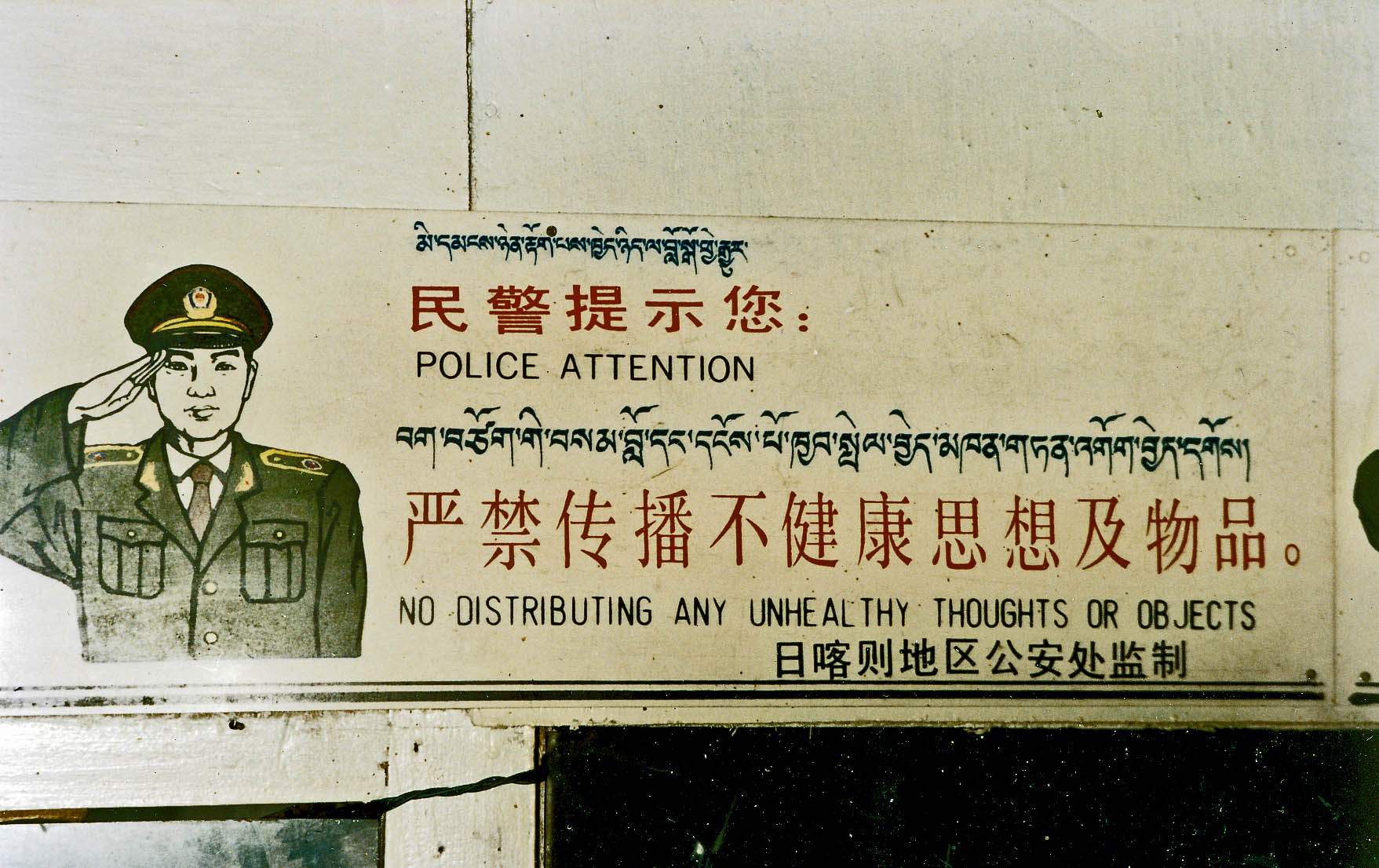

Following the Chinese invasion, Tibetan independence and human rights emerged as international issues, gaining significant visibility alongside the

14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (spiritual name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, known as Tenzin Gyatso (Tibetan: བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: ''bsTan-'dzin rgya-mtsho''); né Lhamo Thondup), known as ...

in the 1980s and 90s. Chinese authorities have sought to assert control over Tibet and has been accused of the destruction of religious sites and banning possession of pictures of the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan religious practices. During the crises created by the

Great Leap Forward, Tibet was subjected to mass starvation, allegedly because of the appropriation of Tibetan crops and foodstuffs by the PRC government. The PRC disputes these claims and points to their investments in Tibetan infrastructure, education, and industrialization as evidence that they have replaced a theocratic feudal government with a modern state.

Geographical setting

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

lies between the civilizations of

China and

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. Extensive mountain ranges to the east of the

Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the ...

mark the border with China, and the

Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

of

Nepal

Nepal (; ne, :ne:नेपाल, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in S ...

and India separate Tibet and India. Tibet has been called the "roof of the world" and "the land of snows".

Linguists classify the

Tibetan language Tibetan language may refer to:

* Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

* Lhasa Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dialect

* Any of the other Tibetic languages

See also

* Old Tibetan, the languag ...

and its dialects as belonging to the

Tibeto-Burman languages

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non- Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the Southeast Asian Massif ("Zomia") as well as parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people sp ...

, the non-

Sinitic

The Sinitic languages (漢語族/汉语族), often synonymous with "Chinese languages", are a group of East Asian analytic languages that constitute the major branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. It is frequently proposed that there is ...

members of the

Sino-Tibetan language family

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ...

.

Prehistory

Some archaeological data suggest

archaic humans passed through Tibet at the time India was first inhabited, half a million years ago.

Impressions of hands and feet suggest

hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The ...

s were present at the above 4,000 meters above sea level high Tibetan Plateau 169,000–226,000 years ago.

Modern human

Early modern human (EMH) or anatomically modern human (AMH) are terms used to distinguish ''Homo sapiens'' (the only extant Hominina species) that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from extin ...

s first inhabited the Tibetan Plateau at least twenty-one thousand years ago.

This population was largely replaced around 3000 years ago by

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

immigrants from

northern China. However, there is a "partial genetic continuity between the Paleolithic inhabitants and the contemporary Tibetan populations". The vast majority of Tibetan maternal mtDNA components can trace their ancestry to both paleolithic and Neolithic during the mid-Holocene.

Megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic monuments dot the Tibetan Plateau and may have been used in ancestor worship.

Prehistoric

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

hillfort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

s and burial complexes have recently been found on the Tibetan Plateau, but the remote high altitude location makes archaeological research difficult.

Early history (c. 500 BC – AD 618)

Zhangzhung kingdom (c. 500 BC – AD 625)

According to

Namkhai Norbu

Namkhai Norbu (; 8 December 1938 – 27 September 2018) was a Tibetan Buddhist master of Dzogchen and a professor of Tibetan and Mongolian language and literature at Naples Eastern University. He was a leading authority on Tibetan culture, par ...

some Tibetan historical texts identify the Zhang Zhung culture as a people who migrated from the

Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the ...

region into what is now the region of

Guge in western Tibet. Zhang Zhung is considered to be the original home of the

Bön religion.

[Helmut Hoffman in ]

By the 1st century BC, a neighboring kingdom arose in the

Yarlung Valley

The Yarlung Valley is formed by Yarlung Chu, a tributary of the Tsangpo River in the Shannan Prefecture in the Tibet region of China. It refers especially to the district where Yarlung Chu joins with the Chongye River, and broadens out into a la ...

, and the Yarlung king,

Drigum Tsenpo Drigum Tsenpo was an emperor of Tibet. According to Tibetan mythology, he was the first king of Tibet to lose his immortality when he angered his stable master, Lo-ngam. Legend states that rulers of Tibet descended from heaven to earth on a cord ...

, attempted to remove the influence of the Zhang Zhung by expelling the Zhang's

Bön priests from Yarlung. Tsenpo was assassinated and Zhang Zhung continued its dominance of the region until it was annexed by Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century.

Tibetan tribes (2nd century AD)

In AD 108, "the Kiang or Tibetans, a nomad from south-west of

Koko-nor, attacked the Chinese posts of

Gansu, threatening to cut the

Dunhuang road. Liang Kin, at the price of some fierce fighting, held them off." Similar incursions were repelled in AD 168–169 by the Chinese general Duan Gong.

Chinese sources of the same era mention of a Fu state () of either Qiang or Tibetan ethnicity "more than two thousand miles northwest of

Shu County". Fu state was pronounced as "bod" or "phyva" in Archaic Chinese. Whether this polity is the precursor of Tufan is still unknown.

First kings of the pre-Imperial Yarlung dynasty (2nd–6th centuries)

The pre-Imperial Yarlung Dynasty rulers are considered mythological because sufficient evidence of their existence has not been found.

Nyatri Tsenpo is considered by traditional histories to have been the first king of the Yarlung Dynasty, named after the river valley where its capital city was located, approximately fifty-five miles south-east from present-day Lhasa. The dates attributed to the first Tibetan king,

Nyatri Tsenpo (), vary. Some Tibetan texts give 126 BC, others 414 BC.

Nyatri Tsenpo is said to have descended from a one-footed creature called the Theurang, having webbed fingers and a tongue so large it could cover his face. Due to his terrifying appearance he was feared in his native Puwo and exiled by the

Bön to Tibet. There he was greeted as a fearsome being, and he became king.

The Tibetan kings were said to remain connected to the heavens via a ''dmu'' cord (''dmu thag'') so that rather than dying, they ascended directly to heaven, when their sons achieved their majority. According to various accounts, king

Drigum Tsenpo Drigum Tsenpo was an emperor of Tibet. According to Tibetan mythology, he was the first king of Tibet to lose his immortality when he angered his stable master, Lo-ngam. Legend states that rulers of Tibet descended from heaven to earth on a cord ...

(''Dri-gum-brtsan-po'') either challenged his clan heads to a fight, or provoked his groom ''Longam'' (''Lo-ngam'') into a duel. During the fight the king's ''dmu'' cord was cut, and he was killed. Thereafter Drigum Tsenpo and subsequent kings left corpses and the Bön conducted funerary rites.

In a later myth, first attested in the ''Maṇi bka' 'bum'', the Tibetan people are the progeny of the union of the monkey

Pha Trelgen Changchup Sempa and rock ogress Ma Drag Sinmo. But the monkey was a manifestation of the

bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva ( ; sa, 𑀩𑁄𑀥𑀺𑀲𑀢𑁆𑀢𑁆𑀯 (Brahmī), translit=bodhisattva, label=Sanskrit) or bodhisatva is a person who is on the path towards bodhi ('awakening') or Buddhahood.

In the Early Buddhist schools ...

Chenresig, or

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

(Tib. ''Spyan-ras-gzigs'') while the ogress in turn incarnated Chenresig's consort

Dolma (Tib. ''

'Grol-ma'').

Tibetan Empire (618–842)

The Yarlung kings gradually extended their control, and by the early 6th century most of the Tibetan tribes were under its control, when

Namri Songtsen

Namri Songtsen (), also known as "Namri Löntsen" () (died 618) was according to tradition, the 32nd King of Tibet of the Yarlung Dynasty. (Reign: 570 – 618) During his 48 years of reign, he expanded his kingdom to rule the central part of the ...

(570?–618?/629), the 32nd King of Tibet of the Yarlung Dynasty, gained control of all the area around what is now Lhasa by 630, and conquered Zhangzhung.

With this extent of power the Yarlung kingdom turned into the Tibetan Empire.

The government of Namri Songtsen sent two embassies to China in 608 and 609, marking the appearance of Tibet on the international scene. From the 7th century AD Chinese historians referred to Tibet as

Tubo Tubo may refer to:

* Tibet, called Tubo or Tufan in Chinese historical texts

** Tibetan Empire (618–842)

* Tubo, Abra

Tubo, officially the Municipality of Tubo ( ilo, Ili ti Tubo; tgl, Bayan ng Tubo), is a 4th class municipality in the provin ...

(), though four distinct characters were used. The first externally confirmed contact with the Tibetan kingdom in recorded Tibetan history occurred when King

Namri Löntsän (''Gnam-ri-slon-rtsan'') sent an ambassador to China in the early 7th century.

Traditional Tibetan history preserves a lengthy list of rulers whose exploits become subject to external verification in the Chinese histories by the 7th century. From the 7th to the 11th centuries a series of

emperors

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother (empr ...

ruled Tibet (see

List of emperors of Tibet

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby uni ...

) of whom the three most important in later religious tradition were

Songtsen Gampo

Songtsen Gampo (; 569–649? 650), also Songzan Ganbu (), was the 33rd Tibetan king and founder of the Tibetan Empire, and is traditionally credited with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, influenced by his Nepali consort Bhrikuti, of Nepa ...

,

Trisong Detsen

Tri Songdetsen () was the son of Me Agtsom, the 38th emperor of Tibet. He ruled from AD 755 until 797 or 804. Tri Songdetsen was the second of the Three Dharma Kings of Tibet, playing a pivotal role in the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet and th ...

and

Ralpacan, "the three religious kings" (''mes-dbon gsum''), who were assimilated to the three protectors (''rigs-gsum mgon-po''), respectively,

Avalokiteśvara

In Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर, IPA: ) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He has 108 avatars, one notable avatar being Padmapāṇi (lotus bearer). He is variably depicted, ...

,

Mañjuśrī

Mañjuśrī (Sanskrit: मञ्जुश्री) is a ''bodhisattva'' associated with '' prajñā'' (wisdom) in Mahāyāna Buddhism. His name means "Gentle Glory" in Sanskrit. Mañjuśrī is also known by the fuller name of Mañjuśrīkumārab ...

and

Vajrapāni. Songtsen Gampo (c. 604–650) was the first great emperor who expanded Tibet's power beyond Lhasa and the

Yarlung Valley

The Yarlung Valley is formed by Yarlung Chu, a tributary of the Tsangpo River in the Shannan Prefecture in the Tibet region of China. It refers especially to the district where Yarlung Chu joins with the Chongye River, and broadens out into a la ...

, and is traditionally credited with introducing

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

to Tibet.

Throughout the centuries from the time of the emperor the power of the empire gradually increased over a diverse terrain so that by the reign of the emperor in the opening years of the 9th century, its influence extended as far south as

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

and as far north as

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

. Tibetan records claim that the

Pala Empire

The Pāla Empire (r. 750-1161 CE) was an imperial power during the post-classical period in the Indian subcontinent, which originated in the region of Bengal. It is named after its ruling dynasty, whose rulers bore names ending with the suffi ...

was conquered and that the Pala emperor

Dharmapala

A ''dharmapāla'' (, , ja, 達磨波羅, 護法善神, 護法神, 諸天善神, 諸天鬼神, 諸天善神諸大眷屬) is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism. The name means "'' dharma'' protector" in Sanskrit, and the ''dharmapālas'' are a ...

submitted to Tibet, though no independent evidence confirms this.

The varied terrain of the empire and the difficulty of transportation, coupled with the new ideas that came into the empire as a result of its expansion, helped to create stresses and power blocs that were often in competition with the ruler at the center of the empire. Thus, for example, adherents of the

Bön religion and the supporters of the ancient noble families gradually came to find themselves in competition with the recently introduced

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religions, Indian religion or Indian philosophy#Buddhist philosophy, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha. ...

.

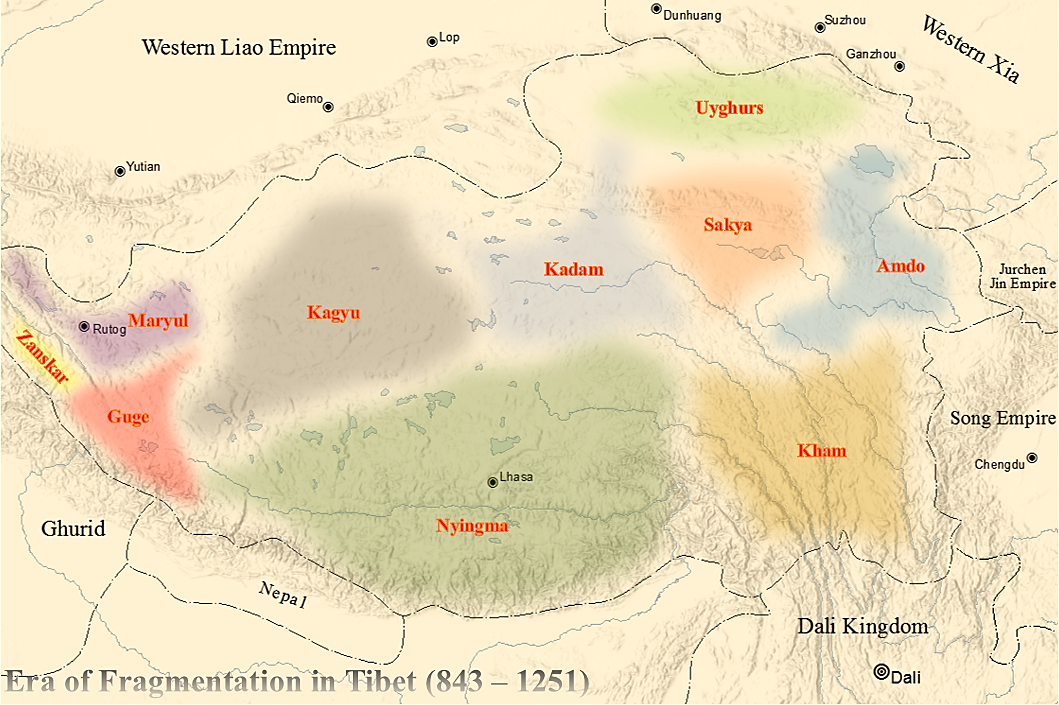

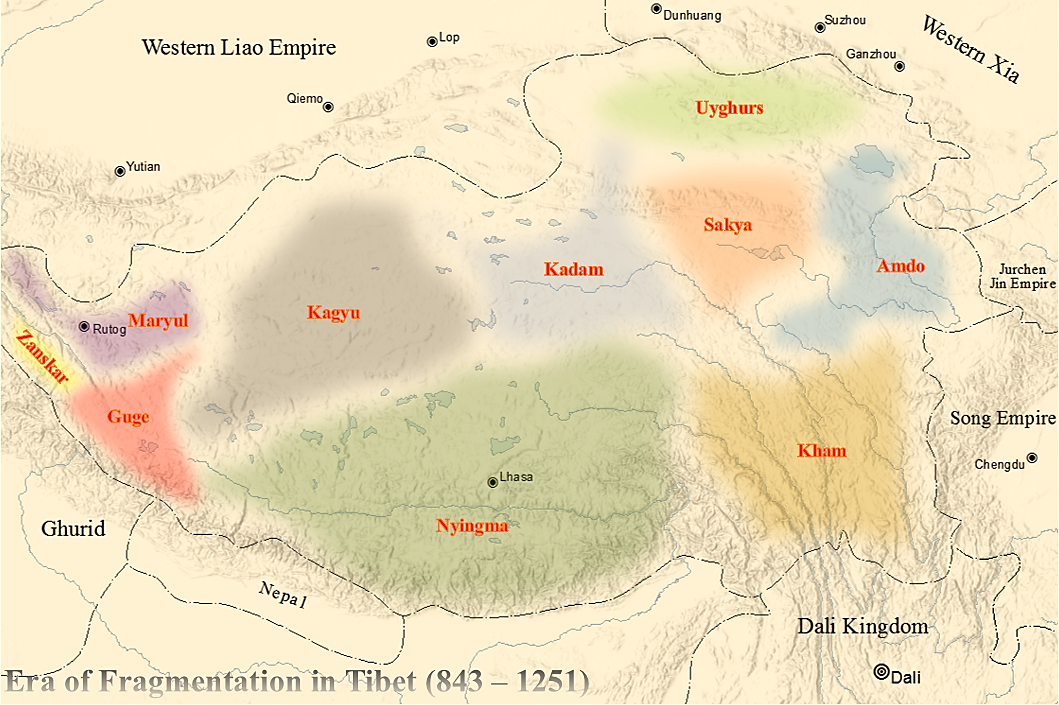

Era of Fragmentation and Cultural Renaissance (9th–12th centuries)

Fragmentation of political power (9th–10th centuries)

The Era of Fragmentation was a period of Tibetan history in the 9th and 10th centuries. During this era, the political centralization of the earlier

Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (, ; ) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 3 ...

collapsed. The period was dominated by rebellions against the remnants of imperial Tibet and the rise of regional warlords. Upon the death of

Langdarma

Darma Udumtsen (), better known by his nickname Langdarma (, "Mature Bull" or "Dharma the Bull") was most likely the last Tibetan Emperor who most likely reigned from 838 to 841 CE. Early sources call him Tri Darma "King Dharma". His domain e ...

, the last emperor of a unified Tibetan empire, there was a controversy over whether he would be succeeded by his alleged heir Yumtän (''Yum brtan''), or by another son (or nephew) Ösung (''Od-srung'') (either 843–905 or 847–885). A civil war ensued, which effectively ended centralized Tibetan administration until the Sa-skya period. Ösung's allies managed to keep control of Lhasa, and Yumtän was forced to go to Yalung, where he established a separate line of kings. In 910, the tombs of the emperors were defiled.

The son of Ösung was Pälkhortsän (''Dpal 'khor brtsan'') (865–895 or 893–923). The latter apparently maintained control over much of central Tibet for a time, and sired two sons, Trashi Tsentsän (''Bkra shis brtsen brtsan'') and Thrikhyiding (''Khri khyi lding''), also called

Kyide Nyimagön (''Skyid lde nyi ma mgon'') in some sources. Thrikhyiding migrated to the western Tibetan region of

upper Ngari (''Stod Mnga ris'') and married a woman of high central Tibetan nobility, with whom he founded a local dynasty.

After the breakup of the Tibetan empire in 842, Nyima-Gon, a representative of the ancient Tibetan royal house, founded the

first Ladakh dynasty. Nyima-Gon's kingdom had its centre well to the east of present-day

Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu ...

. Kyide Nyigön's eldest son became ruler of the

Maryul (Ladakh region), and his two younger sons ruled western Tibet, founding the Kingdom of

Guge–

Purang and

Zanskar

Zanskar, Zahar (locally) or Zangskar, is a tehsil of Kargil district, in the Indian union territory of Ladakh. The administrative centre is Padum (former Capital of Zanskar). Zanskar, together with the neighboring region of Ladakh, was brie ...

–

Spiti

Spiti (pronounced as Piti in Bhoti language) is a high-altitude region of the Himalayas, located in the north-eastern part of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. The name "Spiti" means "The middle land", i.e. the land between Tib ...

. Later the king of Guge's eldest son, Kor-re, also called Jangchub

Yeshe-Ö (''Byang Chub Ye shes' Od''), became a Buddhist monk. He sent young scholars to

Kashmir for training and was responsible for inviting

Atiśa

( bn, অতীশ দীপংকর শ্রীজ্ঞান, ôtiś dīpôṅkôr śrigyen; 982–1054) was a Buddhist religious leader and master. He is generally associated with his work carried out at the Vikramashila monastery in Biha ...

to Tibet in 1040, thus ushering in the Chidar (''Phyi dar'') phase of Buddhism in Tibet. The younger son, Srong-nge, administered day-to-day governmental affairs; it was his sons who carried on the royal line.

Tibetan Renaissance (10th–12th centuries)

According to traditional accounts, Buddhism had survived surreptitiously in the region of

Kham. The late 10th century and 11th century saw a revival of Buddhism in Tibet. Coinciding with the early discoveries of "hidden treasures" (

''terma''),

[Berzin, Alexander. ''The Four Traditions of Tibetan Buddhism: Personal Experience, History, and Comparisons''](_blank)

/ref> the 11th century saw a revival of Buddhist influence originating in the far east and far west of Tibet.

Muzu Saelbar (''Mu-zu gSal-'bar''), later known as the scholar Gongpa Rabsal (''bla chen dgongs pa rab gsal'') (832–915), was responsible for the renewal of Buddhism in northeastern Tibet, and is counted as the progenitor of the Nyingma

Nyingma (literally 'old school') is the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It is also often referred to as ''Ngangyur'' (, ), "order of the ancient translations". The Nyingma school is founded on the first lineages and transl ...

(''Rnying ma pa'') school of Tibetan Buddhism. In the west, Rinchen Zangpo

__NOTOC__

Lochen Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055; ), also known as Mahaguru, was a principal lotsawa or translator of Sanskrit Buddhist texts into Tibetan during the second diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet, variously called the New Translation School, ...

(958–1055) was active as a translator and founded temples and monasteries. Prominent scholars and teachers were again invited from India.

In 1042 Atiśa

( bn, অতীশ দীপংকর শ্রীজ্ঞান, ôtiś dīpôṅkôr śrigyen; 982–1054) was a Buddhist religious leader and master. He is generally associated with his work carried out at the Vikramashila monastery in Biha ...

(982–1054 CE) arrived in Tibet at the invitation of a west Tibetan king. This renowned exponent of the Pāla form of Buddhism from the Indian university of Vikramashila

Vikramashila (Sanskrit: विक्रमशिला, IAST: , Bengali:- বিক্রমশিলা, Romanisation:- Bikrômôśilā ) was one of the three most important Buddhist monasteries in India during the Pala Empire, along wit ...

later moved to central Tibet. There his chief disciple, Dromtonpa, founded the Kadampa

300px, Tibetan Portrait of Atiśa

The Kadam school () of Tibetan Buddhism was an 11th century Buddhist tradition founded by the great Bengali master Atiśa (982-1054) and his students like Dromtön (1005–1064), a Tibetan Buddhist lay master. ...

school of Tibetan Buddhism under whose influence the New Translation schools of today evolved.

The Sakya

The ''Sakya'' (, 'pale earth') school is one of four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the others being the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Gelug. It is one of the Red Hat Orders along with the Nyingma and Kagyu.

Origins

Virūpa, 16th century. It depic ...

, the ''Grey Earth'' school, was founded by Khön Könchok Gyelpo (, 1034–1102), a disciple of the great Lotsawa

Lotsawa () is a Tibetan word used as a title to refer to the native Tibetan translators, such as Vairotsana, Rinchen Zangpo, Marpa Lotsawa, Tropu Lotsawa Jampa Pel and others, who worked alongside Indian scholars or panditas to translate Budd ...

, Drogmi Shākya (). It is headed by the Sakya Trizin

Sakya Trizin ( "Sakya Throne-Holder") is the traditional title of the head of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism.''Holy Biographies of the Great Founders of the Glorious Sakya Order'', translated by Venerable Lama Kalsang Gyaltsen, Ani Kunga ...

, traces its lineage to the mahasiddha

Mahasiddha ( Sanskrit: ''mahāsiddha'' "great adept; ) is a term for someone who embodies and cultivates the "siddhi of perfection". A siddha is an individual who, through the practice of sādhanā, attains the realization of siddhis, psychic ...

Virūpa,[Berzin. Alexander (2000). ''How Did Tibetan Buddhism Develop?'']

StudyBuddhism.com

/ref> and represents the scholarly tradition. A renowned exponent, Sakya Pandita

Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyeltsen (Tibetan: ས་སྐྱ་པཎ་ཌི་ཏ་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་མཚན, ) (1182 – 28 November 1251) was a Tibetan spiritual leader and Buddhist scholar and the fourth of the Five S ...

(1182–1251CE), was the great-grandson of Khön Könchok Gyelpo.

Other seminal Indian teachers were Tilopa

Tilopa (Prakrit; Sanskrit: Talika or Tilopadā; 988–1069) was an Indian Buddhist monk in the tantric Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

He lived along the Ganges River, with wild ladies as a tantric practitioner and mahasiddha. He practic ...

(988–1069) and his student Naropa (probably died ca. 1040 CE). The Kagyu, the ''Lineage of the (Buddha's) Word'', is an oral tradition which is very much concerned with the experiential dimension of meditation. Its most famous exponent was Milarepa

Jetsun Milarepa (, 1028/40–1111/23) was a Tibetan siddha, who was famously known as a murderer when he was a young man, before turning to Buddhism and becoming a highly accomplished Buddhist disciple. He is generally considered one of Tibet's m ...

, an 11th-century mystic. It contains one major and one minor subsect. The first, the Dagpo Kagyu, encompasses those Kagyu schools that trace back to the Indian master Naropa via Marpa Lotsawa

Marpa Lotsāwa (, 1012–1097), sometimes known fully as Marpa Chökyi Lodrö ( Wylie: mar pa chos kyi blo gros) or commonly as Marpa the Translator (Marpa Lotsāwa), was a Tibetan Buddhist teacher credited with the transmission of many Vajraya ...

, Milarepa and Gampopa

Gampopa Sönam Rinchen (, 1079–1153) was the main student of Milarepa, and a Tibetan Buddhist master who codified his own master's ascetic teachings, which form the foundation of the Kagyu educational tradition. Gampopa was also a doctor and ...

.

Mongol conquest and Yuan administrative rule (1240–1354)

During this era, the region was dominated by the Sakya lama with the

During this era, the region was dominated by the Sakya lama with the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

' support, so it is also called the Sakya dynasty. The first documented contact between the Tibetans and the Mongols occurred when the missionary Tsang-pa Dung-khur (''gTsang-pa Dung-khur-ba'') and six disciples met Genghis Khan, probably on the Tangut border where he may have been taken captive, around 1221–22. He left Mongolia as the Quanzhen sect

The Quanzhen School (全真: ''Quánzhēn''), also known as Completion of Authenticity, Complete Reality, and Complete Perfection is currently one of the two dominant denominations of Taoism in mainland China. It originated in Northern China in ...

of Daoism

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the ''Tao'' ...

gained the upper hand, but remet Genghis Khan when Mongols conquered Tangut shortly before the Khan's death. Closer contacts ensued when the Mongols successively sought to move through the Sino-Tibetan borderlands to attack the Jin dynasty and then the Southern Song

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

, with incursions on outlying areas. One traditional Tibetan account claims that there was a plot to invade Tibet by Genghis Khan in 1206, which is considered anachronistic as there is no evidence of Mongol-Tibetan encounters prior to the military campaign in 1240. The mistake may have arisen from Genghis's real campaign against the Tangut Xixia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut people, Tangut-led Chinese Buddhism, Buddhis ...

.

The Mongols invaded Tibet in 1240 with a small campaign led by the Mongol general Doorda Darkhan that consisted of 30,000 troops. The battle resulted in Darkhan's troops suffering 500 casualties. The Mongols withdrew their soldiers from Tibet in 1241, as all the Mongol princes were recalled back to Mongolia in preparation for the appointment of a successor to Ögedei Khan. They returned to the region in 1244, when Köten

Köten (russian: Котян, hu, Kötöny, ar, Kutan, later Jonas; 1205–1241) was a Cuman–Kipchak chieftain (''khan'') and military commander active in the mid-13th century. He forged an important alliance with the Kievan Rus' against the ...

delivered an ultimatum, summoning the abbot of Sakya (''Kun-dga' rGyal-mtshan'') to be his personal chaplain, on pains of a larger invasion were he to refuse. Sakya Paṇḍita took almost 3 years to obey the summons and arrive in Kokonor in 1246, and met Prince Köten in Lanzhou the following year. The Mongols had annexed Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the ...

and Kham to the east, and appointed Sakya Paṇḍita Viceroy of Central Tibet by the Mongol court in 1249.

Tibet was incorporated into the Mongol Empire, retaining nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols managed a structural and administrative rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. This existed as a " diarchic structure" under the Mongol emperor, with power primarily in favor of the Mongols.Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fift ...

, Tibet was managed by the Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs or Xuanzheng Yuan, separate from other Yuan provinces such as those governed the former Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

of China. One of the department's purposes was to select a dpon-chen

The ''dpon-chen'' or ''pönchen'' (), literally the "great authority" or "great administrator", was the chief administrator or governor of Tibet located at Sakya Monastery during the Yuan administrative rule of Tibet in the 13th and 14th centuries ...

, usually appointed by the lama and confirmed by the Yuan emperor in Beijing.Imperial Preceptor

The Imperial Preceptor, or Dishi (, lit. "Teacher of the Emperor") was a high title and powerful post created by Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty. It was established as part of Mongol patronage of Tibetan Buddhism and the Yuan administra ...

(originally State Preceptor) in 1260, the year when he became Khagan. Phagpa developed the priest-patron concept that characterized Tibeto-Mongolian relations from that point forward.[ F. W. Mote. ''Imperial China 900-1800''. Harvard University Press, 1999. p.501.] With the support of Kublai Khan, Phagpa established himself and his sect as the preeminent political power in Tibet. Through their influence with the Mongol rulers, Tibetan lamas gained considerable influence in various Mongol clans, not only with Kublai, but, for example, also with the Il-Khan

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm ...

ids.

In 1265, Chögyal Phagpa returned to Tibet and for the first time made an attempt to impose Sakya hegemony with the appointment of Shakya Bzang-po, a longtime servant and ally of the Sakyas, as the dpon-chen ('great administrator') over Tibet in 1267. A census was conducted in 1268 and Tibet was divided into thirteen myriarchies (administrative districts, nominally containing 10,000 households). By the end of the century, Western Tibet lay under the effective control of imperial officials (almost certainly Tibetans) dependent on the 'Great Administrator', while the kingdoms of Guge and Pu-ran retained their internal autonomy.

The Sakya hegemony over Tibet continued into the mid-14th century, although it was challenged by a revolt of the Drikung

Drikung Kagyü or Drigung Kagyü ( Wylie: 'bri-gung bka'-brgyud) is one of the eight "minor" lineages of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. "Major" here refers to those Kagyü lineages founded by the immediate disciples of Gampopa (1079-1153) w ...

Kagyu sect with the assistance of Duwa Khan

Duwa (; died 1307), also known as Du'a, was khan of the Chagatai Khanate (1282–1307). He was the second son of Baraq. He was the longest reigning monarch of the Chagatayid Khanate and accepted the nominal supremacy of the Yuan dynasty as G ...

of the Chagatai Khanate

The Chagatai Khanate, or Chagatai Ulus ( xng, , translit=Čaɣatay-yin Ulus; mn, Цагаадайн улс, translit=Tsagaadain Uls; chg, , translit=Čağatāy Ulusi; fa, , translit=Xânât-e Joghatây) was a Mongol and later Turkicized kh ...

in 1285. The revolt was suppressed in 1290 when the Sakyas and eastern Mongols burned Drikung Monastery and killed 10,000 people.

Between 1346 and 1354, towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, the House of Pagmodru would topple the Sakya. The rule over Tibet by a succession of Sakya lamas came to a definite end in 1358, when central Tibet came under control of the Kagyu sect. "By the 1370s, the lines between the schools of Buddhism were clear."

The following 80-or-so years were a period of relative stability. They also saw the birth of the Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous")Kay, David N. (2007). ''Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantati ...

pa school (also known as ''Yellow Hats'') by the disciples of Tsongkhapa Lobsang Dragpa, and the founding of the Ganden

Ganden Monastery (also Gaden or Gandain) or Ganden Namgyeling or Monastery of Gahlden is one of the "great three" Gelug university monasteries of Tibet. It is in Dagzê County, Lhasa. The other two are Sera Monastery and Drepung Monastery. Gand ...

, Drepung

Drepung Monastery (, "Rice Heap Monastery"), located at the foot of Mount Gephel, is one of the "great three" Gelug university gompas (monasteries) of Tibet. The other two are Ganden Monastery and Sera Monastery.

Drepung is the largest of all ...

, and Sera monasteries near Lhasa. After the 1430s, the country entered another period of internal power struggles.

Tibetan independence (14th-18th century)

With the decline of the Yuan dynasty, Central Tibet was ruled by successive families from the 14th to the 17th centuries, to be succeeded by the Dalai Lama's rule in the 17th and 18th centuries. Tibet would be de facto independent from the mid-14th century on, for nearly 400 years. In spite of the weakening of central authority, the neighbouring Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last orthodox dynasty of China ruled by the Han peo ...

of China made little effort to impose direct rule, although it had nominal claims of the Tibetan territory by establishing the U-Tsang Regional Military Commission and Do-Kham Regional Military Commission in 1370s. They also kept friendly relations with some of the Buddhism religious leaders known as Princes of Dharma and granted some other titles to local leaders including the Grand Imperial Tutor.

Family rule (14th–17th centuries)

Phagmodrupa (14th–15th centuries)

The Phagmodru (Phag mo gru) myriarchy centered at Neudong (Sne'u gdong) was granted as an appanage to Hülegü in 1251. The area had already been associated with the Lang (Rlang) family, and with the waning of Ilkhanate influence it was ruled by this family, within the Mongol-Sakya framework headed by the Mongol appointed Pönchen (dpon-chen) at Sakya. The areas under Lang administration were continually encroached upon during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Jangchub Gyaltsän (Byang chub rgyal mtshan, 1302–1364) saw these encroachments as illegal and sought the restoration of Phagmodru lands after his appointment as the Myriarch in 1322. After prolonged legal struggles, the struggle became violent when Phagmodru was attacked by its neighbours in 1346. Jangchub Gyaltsän was arrested and released in 1347. When he later refused to appear for trial, his domains were attacked by the Pönchen in 1348. Janchung Gyaltsän was able to defend Phagmodru, and continued to have military successes, until by 1351 he was the strongest political figure in the country. Military hostilities ended in 1354 with Jangchub Gyaltsän as the unquestioned victor, who established the Phagmodrupa dynasty

The Phagmodrupa dynasty or Pagmodru (, ; ) was a dynastic regime that held sway over Tibet or parts thereof from 1354 to the early 17th century. It was established by Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen of the Lang () family at the end of the Yuan dynas ...

in that year. He continued to rule central Tibet until his death in 1364, although he left all Mongol institutions in place as hollow formalities. Power remained in the hands of the Phagmodru family until 1434.

The rule of Jangchub Gyaltsän and his successors implied a new cultural self-awareness where models were sought in the age of the ancient Tibetan Kingdom. The relatively peaceful conditions favoured the literary and artistic development. During this period the reformist scholar Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) founded the Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous")Kay, David N. (2007). ''Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantati ...

sect which would have a decisive influence on Tibet's history.

Rinpungpa family (15th–16th centuries)

Internal strife within the Phagmodrupa dynasty and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family Rinpungpa

Rinpungpa (; ) was a Tibetan dynastic regime that dominated much of Western Tibet and part of Ü-Tsang between 1435 and 1565. During one period around 1500 the Rinpungpa lords came close to assemble the Tibetan lands around the Yarlung Tsangpo R ...

, based in Tsang (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435.

Tsangpa dynasty (16th–17th centuries)

In 1565 they were overthrown by the Tsangpa

Tsangpa (; ) was a dynasty that dominated large parts of Tibet from 1565 to 1642. It was the last Tibetan royal dynasty to rule in their own name. The regime was founded by Karma Tseten, a low-born retainer of the prince of the Rinpungpa Dynasty ...

Dynasty of Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the Karma Kagyu

Karma Kagyu (), or Kamtsang Kagyu (), is a widely practiced and probably the second-largest lineage within the Kagyu school, one of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The lineage has long-standing monasteries in Tibet, China, Russia, ...

sect. They would play a pivotal role in the events which led to the rise of power of the Dalai Lama's in the 1640s.

Ganden Phodrang government (17th–18th centuries)

The ''Ganden Phodrang'' was the Tibetan government established in 1642 by the

The ''Ganden Phodrang'' was the Tibetan government established in 1642 by the 5th Dalai Lama

Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (; ; 1617–1682) was the 5th Dalai Lama and the first Dalai Lama to wield effective temporal and spiritual power over all Tibet. He is often referred to simply as the Great Fifth, being a key religious and temporal leader ...

with the military assistance of Güshi Khan

Güshi Khan (1582 – 14 January 1655; ) was a Khoshut prince and founder of the Khoshut Khanate, who supplanted the Tumed descendants of Altan Khan as the main benefactor of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1637, Güshi ...

of the Khoshut Khanate

The Khoshut Khanate was a Mongol Oirat khanate based on the Tibetan Plateau from 1642 to 1717. Based in modern Qinghai, it was founded by Güshi Khan in 1642 after defeating the opponents of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. The r ...

. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet in the beginning of this period, with all temporal power being conferred to the 5th Dalai Lama by Güshi Khan in Shigatse.

Rise of the Gelugpa school and the Dalai Lama

The rise of the Dalai Lamas was intimately connected with the military power of Mongolian clans. Altan Khan, the king of the Tümed

The Tümed (Tumad, ; "The many or ten thousands" derived from Tumen) are a Mongol subgroup. They live in Tumed Left Banner, district of Hohhot and Tumed Right Banner, district of Baotou in China. Most engage in sedentary agriculture, living in ...

Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

, first invited Sonam Gyatso, the head of the Gelugpa

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous")Kay, David N. (2007). ''Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantati ...

school of Tibetan Buddhism (later known as the third Dalai Lama), to Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

in 1569 and again in 1578, during the reign of the Tsangpa family. Gyatso accepted the second invitation. They met at the site of Altan Khan's new capital, Koko Khotan (Hohhot), and the Dalai Lama taught a large crowd there.

Sonam Gyatso publicly announced that he was a reincarnation of the Tibetan Sakya

The ''Sakya'' (, 'pale earth') school is one of four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the others being the Nyingma, Kagyu, and Gelug. It is one of the Red Hat Orders along with the Nyingma and Kagyu.

Origins

Virūpa, 16th century. It depic ...

monk Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) who converted Kublai Khan, while Altan Khan was a reincarnation of Kublai Khan (1215–1294), the famous ruler of the Mongols and Emperor of China, and that they had come together again to cooperate in propagating the Buddhist religion. While this did not immediately lead to a massive conversion of Mongols to Buddhism (this would only happen in the 1630s), it did lead to the widespread use of Buddhist ideology for the legitimation of power among the Mongol nobility. Last but not least, Yonten Gyatso

Yonten Gyatso or Yon-tan-rgya-mtsho (1589–1617), was the 4th Dalai Lama, born in Mongolia on the 30th day of the 12th month of the Earth-Ox year of the Tibetan calendar.Thubten Samphel and Tendar (2004), p.87. Other sources, however, say he wa ...

, the fourth Dalai Lama, was a grandson of Altan Khan.

Khoshut-Gelugpa alliance

Yonten Gyatso

Yonten Gyatso or Yon-tan-rgya-mtsho (1589–1617), was the 4th Dalai Lama, born in Mongolia on the 30th day of the 12th month of the Earth-Ox year of the Tibetan calendar.Thubten Samphel and Tendar (2004), p.87. Other sources, however, say he wa ...

(1589–1616), the fourth Dalai Lama and a non-Tibetan, was the grandson of Altan Khan. He died in 1616 in his mid-twenties. Some people say he was poisoned but there is no real evidence one way or the other.

Lobsang Gyatso (Wylie transliteration

Wylie transliteration is a method for transliterating Tibetan script using only the letters available on a typical English-language typewriter. The system is named for the American scholar Turrell V. Wylie, who created the system and published ...

: Blo-bzang Rgya-mtsho), the Great Fifth Dalai Lama (1617–1682), was the first Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

to wield effective political power over central Tibet

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

.

The Fifth Dalai Lama's first regent Sonam Rapten

Sönam Rapten (''bsod nams rab brtan''; 1595–1658), initially known as Gyalé Chödze and later on as Sönam Chöpel, was born in the Tholung valley in the Central Tibetan province of Ü. He started off as a monk-administrator (''las sne, lené ...

is known for unifying the Tibetan heartland under the control of the Gelug

240px, The 14th Dalai Lama (center), the most influential figure of the contemporary Gelug tradition, at the 2003 Bodhgaya (India).

The Gelug (, also Geluk; "virtuous")Kay, David N. (2007). ''Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: Transplantati ...

school of Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in majo ...

, after defeating the rival Kagyu and Jonang

The Jonang () is one of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Its origins in Tibet can be traced to early 12th century master Yumo Mikyo Dorje, but became much wider known with the help of Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, a monk originally trained in the ...

sects and the secular ruler, the Tsangpa

Tsangpa (; ) was a dynasty that dominated large parts of Tibet from 1565 to 1642. It was the last Tibetan royal dynasty to rule in their own name. The regime was founded by Karma Tseten, a low-born retainer of the prince of the Rinpungpa Dynasty ...

prince, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were in large part successful due to the military aid contributed by Güshi Khan

Güshi Khan (1582 – 14 January 1655; ) was a Khoshut prince and founder of the Khoshut Khanate, who supplanted the Tumed descendants of Altan Khan as the main benefactor of the Dalai Lama and the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. In 1637, Güshi ...

, the Oirat Khoshut leader of the Khoshut Khanate

The Khoshut Khanate was a Mongol Oirat khanate based on the Tibetan Plateau from 1642 to 1717. Based in modern Qinghai, it was founded by Güshi Khan in 1642 after defeating the opponents of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet. The r ...

. The positions of the Dalai Lama, Sonam Rapten, and the khans have been subject to various interpretations. Some sources claim the khan appointed Sonam Rapten as ''de facto'' administrator of civil affairs while the Dalai Lama was relegated to religious matters. Other sources claim that Güshi Khan was largely uninvolved in the administration of Tibet and remained in Kokonor after defeating the enemies of the Gelugpa school.

The 5th Dalai Lama and his intimates, especially Sonam Rapten (until his death in 1658), established a civil administration referred to by historians as the ''Lhasa state''. This Tibetan administration is also referred to as the Ganden Phodrang

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang (; ) was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642; it operated in Tibet until the 1950s. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet again early in this period, after the Oirat lo ...

, named after the 5th Dalai Lama's residence in Drepung Monastery

Drepung Monastery (, "Rice Heap Monastery"), located at the foot of Mount Gephel, is one of the "great three" Gelug university gompas (monasteries) of Tibet. The other two are Ganden Monastery and Sera Monastery.

Drepung is the largest of all ...

.

Sonam Rapten was a fanatical and militant proponent of the Gelugpa. Under his administration, the other schools were persecuted. Jonang sources today claim that the Jonang monasteries were either closed or forcibly converted, and that school remained in hiding until the latter part of the 20th century. However, before leaving Tibet for China in 1652 the Dalai Lama issued a proclamation or decree to Sonam Rapten banning all such sectarian policies that had been implemented by his administration after the 1642 civil war, and ordered their reversal. According to FitzHerbert and, there was an increase in the 5th Dalai Lama's "day-to-day control of ... his government" after the deaths of Sonam Rapten and Güshi Khan in the 1650s.

The 5th Dalai Lama initiated the construction of the Potala Palace

The Potala Palace is a ''dzong'' fortress in Lhasa, Tibet. It was the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from 1649 to 1959, has been a museum since then, and a World Heritage Site since 1994.

The palace is named after Mount Potalaka, the mythic ...

in Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhas ...

in 1645. During the rule of the Great Fifth, two Jesuit missionaries, the German Johannes Gruber and Belgian Albert Dorville, stayed in Lhasa for two months, October and November, 1661 on their way from Peking to Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

, in India.[

] In 1652, the 5th Dalai Lama visited the Shunzhi Emperor of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

. He was not required to kowtow

A kowtow is the act of deep respect shown by prostration, that is, kneeling and bowing so low as to have one's head touching the ground. In Sinospheric culture, the kowtow is the highest sign of reverence. It was widely used to show reverenc ...

like other visitors, but still had to kneel before the Emperor; and he was later sent an official seal.

The death of the 5th Dalai Lama in 1682 was kept hidden for fifteen years by his assistant confidant, Desi Sangye Gyatso

Desi Sangye Gyatso (1653–1705) was the sixth regent (''desi'') of the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682) in the Ganden Phodrang government. He founded the School of Medicine and Astrology called Men-Tsee-Khang on Chagpori (Iron Mountain) in 1694 an ...

. The 6th Dalai Lama

Tsangyang Gyatso (; born 1 March 1683, died after 1706) was the 6th Dalai Lama. He was an unconventional Dalai Lama that preferred the lifestyle of a crazy wisdom yogi to that of an ordained monk. His regent was killed before he was kidnapped ...

, Tsangyang Gyatso, was enthroned in the Potala on 7 or 8 December 1697. In 1705-6, conflict between the 6th Dalai Lama's regent and the Khoshut Khanate led to the seizure of Lhasa by Lha-bzang Khan

Lha-bzang Khan (; Mongolian: ''Lazang Haan''; alternatively, Lhazang or Lapsangn or Lajang; d.1717) was the ruler of the Khoshut (also spelled Qoshot, Qośot, or Qosot) tribe of the Oirats. He was the son of Tenzin Dalai Khan (1668–1701) and g ...

, who murdered the regent and deposed the 6th Dalai Lama. A pretender, Yeshe Gyatso Yeshe Gyatso'' () (1686–1725) was a pretender for the position of the 6th Dalai Lama of Tibet. Declared by Lha-bzang Khan of the Khoshut Khanate on June 28, 1707, he was the only unofficial Dalai Lama. While praised for his personal moral qualiti ...

, was installed by Lha-bzang until the Dzungar Khanate

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from t ...

invaded in 1717 and removed the Khoshut khan and pretender from power. The 7th Dalai Lama

Kelzang Gyatso (; 1708–1757), also spelled Kalzang Gyatso, Kelsang Gyatso and Kezang Gyatso, was the 7th Dalai Lama of Tibet, recognized as the true incarnation of the 6th Dalai Lama, and enthroned after a pretender was deposed.

The Seventh ...

was installed but the Dzungars terrorized the people, leading to loss of goodwill from the Tibetans. The Dzungars were ousted in 1720 by the Qing dynasty.

Qing conquest and administrative rule (1720–1912)

The Qing rule over Tibet was established after a Qing expedition force defeated the Dzungars

The Dzungar people (also written as Zunghar; from the Mongolian words , meaning 'left hand') were the many Mongol Oirat tribes who formed and maintained the Dzungar Khanate in the 17th and 18th centuries. Historically they were one of major tr ...

who occupied Tibet in 1720, and lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912. The Qing emperors appointed imperial residents known as the Ambans to Tibet, who commanded over 2,000 troops stationed in Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhas ...

and reported to the Lifan Yuan The Lifan Yuan (; ; Mongolian: Гадаад Монголын төрийг засах явдлын яам, ''γadaγadu mongγul un törü-yi jasaqu yabudal-un yamun'') was an agency in the government of the Qing dynasty of China which administered ...

, a Qing government agency that oversaw the region during this period. During this era, the region was dominated by the Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama (, ; ) is a title given by the Tibetan people to the foremost spiritual leader of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism, the newest and most dominant of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The 14th and current D ...

s with the support from the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-spea ...

established by the Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and ...

in China.

Qing rule

Qing conquest

The Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

of the Qing dynasty sent an expedition army to Tibet in response to the occupation of Tibet by the forces of the Dzungar Khanate

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from t ...

, together with Tibetan forces under Polhanas (also spelled Polhaney) of Tsang and Kangchennas (also spelled Gangchenney), the governor of Western Tibet, they expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720. They brought Kelzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum

A Kumbum ( "one hundred thousand holy images") is a multi-storied aggregate of Buddhist chapels in Tibetan Buddhism. The most famous Kumbum forms part of Palcho Monastery.

The first Kumbum was founded in the fire sheep year 1427 by a Gyantse p ...

to Lhasa and he was installed as the 7th Dalai Lama. Qing protectorate over Tibet was established at this time, with a garrison at Lhasa, and Kham was annexed to Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of the ...

. In 1721, the Qing established a government in Lhasa consisting of a council (the ''Kashag

The Kashag (; ), was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721, and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for ...

'') of three Tibetan ministers, headed by Kangchennas. The Dalai Lama's role at this time was purely symbolic, but still highly influential because of the Mongols' religious beliefs.

After the succession of the Yongzheng Emperor

The Yongzheng Emperor (13 December 1678 – 8 October 1735), also known by his temple name Emperor Shizong of Qing, born Yinzhen, was the fourth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the third Qing emperor to rule over China proper. He reigned from ...

in 1722, a series of reductions of Qing forces in Tibet occurred. However, Lhasa nobility who had been allied with the Dzungars killed Kangchennas and took control of Lhasa in 1727, and Polhanas fled to his native Ngari

Ngari Prefecture () or Ali Prefecture () is a prefecture of China's Tibet Autonomous Region covering Western Tibet, whose traditional name is Ngari Khorsum. Its administrative centre and largest settlement is the town of Shiquanhe.

History

Ngar ...

. Qing troops arrived in Lhasa in September, and punished the anti-Qing faction by executing entire families, including women and children. The Dalai Lama was sent to Lithang Monastery in Kham. The Panchen Lama was brought to Lhasa and was given temporal authority over Tsang and Ngari, creating a territorial division between the two high lamas that was to be a long lasting feature of Chinese policy toward Tibet. Two '' ambans'' were established in Lhasa, with increased numbers of Qing troops. Over the 1730s, Qing troops were again reduced, and Polhanas gained more power and authority. The Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in 1735, temporal power remained with Polhanas. The Qing found Polhanas to be a loyal agent and an effective ruler over a stable Tibet, so he remained dominant until his death in 1747.

At multiple places such as Lhasa, Batang, Dartsendo, Lhari, Chamdo, and Litang, Green Standard Army

The Green Standard Army (; Manchu: ''niowanggiyan turun i kūwaran'') was the name of a category of military units under the control of Qing dynasty in China. It was made up mostly of ethnic Han soldiers and operated concurrently with the Manchu ...

troops were garrisoned throughout the Dzungar war. Green Standard Army troops and Manchu Bannermen were both part of the Qing force who fought in Tibet in the war against the Dzungars. It was said that the Sichuan commander Yue Zhongqi (a descendant of Yue Fei

Yue Fei ( zh, t=岳飛; March 24, 1103 – January 28, 1142), courtesy name Pengju (), was a Chinese military general who lived during the Southern Song dynasty and a national hero of China, known for leading Southern Song forces in the wa ...

) entered Lhasa first when the 2,000 Green Standard soldiers and 1,000 Manchu soldiers of the "Sichuan route" seized Lhasa. According to Mark C. Elliott, after 1728 the Qing used Green Standard Army troops to man the garrison in Lhasa rather than Bannermen

Bannerman is a name of Scottish origin (see Clan Bannerman) and may refer to

Places

;Canada

* Bannerman, Edmonton, a neighbourhood in Edmonton, Canada

;United States

* Bannerman, Wisconsin, an unincorporated community

* Bannerman's Castle, an a ...

. According to Evelyn S. Rawski both Green Standard Army and Bannermen made up the Qing garrison in Tibet. According to Sabine Dabringhaus, Green Standard Chinese soldiers numbering more than 1,300 were stationed by the Qing in Tibet to support the 3,000-strong Tibetan army.

The Qing had made the region of Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the ...

and Kham into the province of Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

in 1724, and incorporated eastern Kham into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.Wang Lixiong

Wang Lixiong (, born 2 May 1953) is a Chinese writer and scholar, best known for his political prophecy fiction, ''Yellow Peril'', and for his writings on Tibet and provocative analysis of China's western region of Xinjiang.

Wang is regarded as ...

"Reflections on Tibet"

, ''New Left Review'' 14, March–April 2002:'"Tibetan local affairs were left to the willful actions of the Dalai Lama and the shapes ashag members, he said. "The Commissioners were not only unable to take charge, they were also kept uninformed. This reduced the post of the Residential Commissioner in Tibet to name only.'Gyurme Namgyal

Gyurme Namgyal (; ) (died 11 November 1750) was a ruling prince of Tibet of the Pholha family. He was the son and successor of Polhané Sönam Topgyé and ruled from 1747 to 1750 during the period of Qing rule of Tibet. Gyurme Namgyal was murdere ...

took over upon his father's death in 1747. The ''ambans'' became convinced that he was going to lead a rebellion, so they killed him. News of the incident leaked out and a riot broke out in the city, the mob avenged the regent's death by killing the ''ambans''. The Dalai Lama stepped in and restored order in Lhasa. The Qianlong Emperor (Yongzheng's successor) sent Qing forces to execute Gyurme Namgyal's family and seven members of the group that killed the ''ambans''. The Emperor re-organized the Tibetan government (''Kashag

The Kashag (; ), was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721, and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for ...

'') again, nominally restoring temporal power to the Dalai Lama, but in fact consolidating power in the hands of the (new) ''ambans''.

Expansion of control over Tibet

The defeat of the 1791 Nepalese invasion increased the Qing's control over Tibet. From that moment, all important matters were to be submitted to the ''ambans''. It strengthened the powers of the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' were elevated above the Kashag and the regents in responsibility for Tibetan political affairs. The Dalai and Panchen Lamas were no longer allowed to petition the Qing Emperor directly but could only do so through the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' took control of Tibetan frontier defense and foreign affairs. The ''ambans'' were put in command of the Qing garrison and the Tibetan army (whose strength was set at 3,000 men). Trade was also restricted and travel could be undertaken only with documents issued by the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' were to review all judicial decisions. However, according to Warren Smith, these directives were either never fully implemented, or quickly discarded, as the Qing were more interested in a symbolic gesture of authority than actual sovereignty. In 1841, the

The defeat of the 1791 Nepalese invasion increased the Qing's control over Tibet. From that moment, all important matters were to be submitted to the ''ambans''. It strengthened the powers of the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' were elevated above the Kashag and the regents in responsibility for Tibetan political affairs. The Dalai and Panchen Lamas were no longer allowed to petition the Qing Emperor directly but could only do so through the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' took control of Tibetan frontier defense and foreign affairs. The ''ambans'' were put in command of the Qing garrison and the Tibetan army (whose strength was set at 3,000 men). Trade was also restricted and travel could be undertaken only with documents issued by the ''ambans''. The ''ambans'' were to review all judicial decisions. However, according to Warren Smith, these directives were either never fully implemented, or quickly discarded, as the Qing were more interested in a symbolic gesture of authority than actual sovereignty. In 1841, the Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

Dogra dynasty

The Dogra dynasty of Dogra Rajputs from the Shiwalik Himalayas created Jammu and Kashmir when all dynastic kingdoms in India were being absorbed by the East India Company. Events led the Sikh Empire to recognise Jammu as a vassal state in 1820 ...

attempted to establish their authority on Ü-Tsang

Ü-Tsang is one of the three traditional provinces of Tibet, the others being Amdo in the north-east, and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Geographically Ü-Tsang covered ...

but were defeated in the Sino-Sikh War (1841–1842).

In the mid-19th century, arriving with an Amban, a community of Chinese troops from Sichuan who married Tibetan women settled down in the Lubu neighborhood of Lhasa, where their descendants established a community and assimilated into Tibetan culture. Hebalin was the location of where Chinese Muslim troops and their offspring lived, while Lubu was the place where Han Chinese troops and their offspring lived.

European influences in Tibet

The first Europeans to arrive in Tibet were

The first Europeans to arrive in Tibet were Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

missionaries who first arrived in 1624 led by António de Andrade. They were welcomed by the Tibetans who allowed them to build a church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

. The 18th century brought more Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

and Capuchins

Capuchin can refer to:

*Order of Friars Minor Capuchin

The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (; postnominal abbr. O.F.M. Cap.) is a religious order of Franciscan friars within the Catholic Church, one of Three " First Orders" that reformed from t ...

from Europe. They gradually met opposition from Tibetan lamas who finally expelled them from Tibet in 1745. Other visitors included, in 1774 a Scottish nobleman, George Bogle, who came to Shigatse

Shigatse, officially known as Xigazê (; Nepali: ''सिगात्से''), is a prefecture-level city of the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Its area of jurisdiction, with an area of , corresponds to the histor ...

to investigate trade for the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, introducing the first potatoes into Tibet.

After 1792 Tibet, under Chinese influence, closed its borders to Europeans and during the 19th century only 3 Westerners, the Englishman Thomas Manning and 2 French missionaries Huc and Gabet, reached Lhasa, although a number were able to travel in the Tibetan periphery.

During the 19th century the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

was encroaching from northern India into the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

of the tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

s was expanding south into Central Asia. Each power became suspicious of intent in Tibet. But Tibet attracted the attention of many explorers. In 1840, Sándor Kőrösi Csoma

Sándor Csoma de Kőrös (; born Sándor Csoma; 27 March 1784/811 April 1842) was a Hungarian philologist and Orientalist, author of the first Tibetan–English dictionary and grammar book. He was called Phyi-glin-gi-grwa-pa in Tibetan, meaning ...

arrived in Darjeeling, hoping that he would be able to trace the origin of the Magyar ethnic group, but died before he was able to enter Tibet.

In 1865 Great Britain secretly began mapping Tibet. Trained Indian surveyor-spies disguised as pilgrim

A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journey (often on foot) to some place of special significance to the adherent of ...

s or traders, called pundits

A pundit is a person who offers mass media opinion or commentary on a particular subject area (most typically politics, the social sciences, technology or sport).