Semitic languages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, the Horn of Africa, and latterly North Africa, Malta, West Africa, Chad, and in large immigrant and expatriate communities in North America,

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages has been accepted by all scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel. Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages. However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".

The term "Semitic" was created by members of the

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages has been accepted by all scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel. Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages. However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".

The term "Semitic" was created by members of the

The Akkadian-influenced

The Akkadian-influenced  With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its

With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its

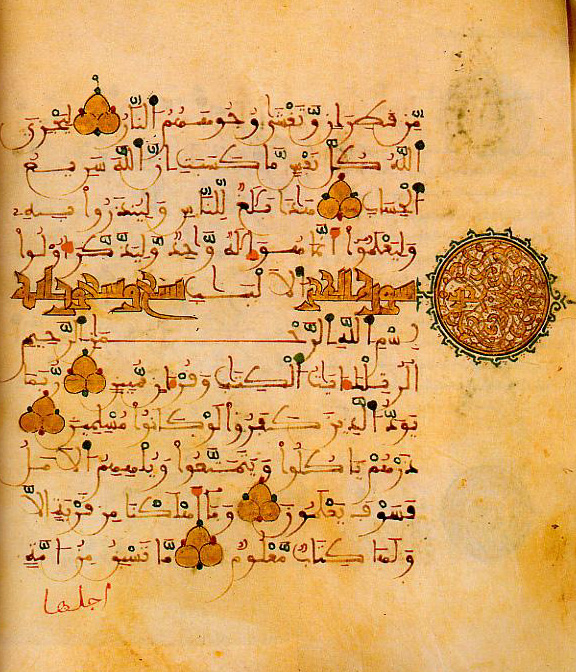

Arabic is currently the native language of majorities from Mauritania to Oman, and from Iraq to the Sudan. Classical Arabic is the language of the Quran. It is also studied widely in the non-Arabic-speaking Muslim world. The

Arabic is currently the native language of majorities from Mauritania to Oman, and from Iraq to the Sudan. Classical Arabic is the language of the Quran. It is also studied widely in the non-Arabic-speaking Muslim world. The

List of Proto-Semitic stems

Swadesh lists for Afro-Asiatic languages

Semitic genealogical tree

(as well as the Afroasiatic one), presented by

short annotations of the talks given there

''Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural''

* [https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02113751 '' Alexis Neme and Sébastien Paumier (2019), Restoring Arabic vowels through omission-tolerant dictionary lookup, Lang Resources & Evaluation, Vol 53, 1–65 pages'']

Swadesh vocabulary lists of Semitic languages

(from Wiktionary'

Swadesh-list appendix

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 Afroasiatic languages Aramaic languages Arabic language Hebrew language Amharic language Ge'ez language Phoenician language Akkadian language

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, and Australasia. The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The or ...

, who derived the name from Shem

Shem (; he, שֵׁם ''Šēm''; ar, سَام, Sām) ''Sḗm''; Ge'ez: ሴም, ''Sēm'' was one of the sons of Noah in the book of Genesis and in the book of Chronicles, and the Quran.

The children of Shem were Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lu ...

, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

Semitic languages occur in written form from a very early historical date in West Asia, with East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced b ...

Akkadian and Eblaite

Eblaite (, also known as Eblan ISO 639-3), or Palaeo-Syrian, is an extinct East Semitic language used during the 3rd millennium BC by the populations of Northern Syria. It was named after the ancient city of Ebla, in modern western Syria. Varian ...

texts (written in a script adapted from Sumerian cuneiform) appearing from the 30th century BCE and the 25th century BCE in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

and the north eastern Levant respectively. The only earlier attested languages are Sumerian and Elamite (2800 BCE to 550 BCE), both language isolates, and Egyptian (a sister branch of the Afroasiatic family, related to the Semitic languages but not part of them). Amorite appeared in Mesopotamia and the northern Levant circa 2000 BC, followed by the mutually intelligible Canaanite languages (including Hebrew, Phoenician, Moabite, Edomite and Ammonite, and perhaps Ekronite, Amalekite and Sutean), the still spoken Aramaic, and Ugaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic language, classified by some as a dialect of the Amorite language and so the only known Amorite dialect preserved in writing. It is known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologist ...

during the 2nd millennium BC.

Most scripts used to write Semitic languages are abjadsa type of alphabetic script that omits some or all of the vowels, which is feasible for these languages because the consonants are the primary carriers of meaning in the Semitic languages. These include the Ugaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic language, classified by some as a dialect of the Amorite language and so the only known Amorite dialect preserved in writing. It is known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologist ...

, Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, Arabic, and ancient South Arabian alphabets. The Geʽez script

Geʽez ( gez, ግዕዝ, Gəʿəz, ) is a script used as an abugida (alphasyllabary) for several Afroasiatic languages, Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan languages, Nilo-Saharan languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It originated as an ''abjad'' (co ...

, used for writing the Semitic languages of Ethiopia and Eritrea, is technically an abugida

An abugida (, from Ge'ez: ), sometimes known as alphasyllabary, neosyllabary or pseudo-alphabet, is a segmental writing system in which consonant-vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel n ...

a modified abjad in which vowels are notated using diacritic marks added to the consonants at all times, in contrast with other Semitic languages which indicate vowels based on need or for introductory purposes. Maltese is the only Semitic language written in the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern I ...

and the only Semitic language to be an official language of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

.

The Semitic languages are notable for their nonconcatenative morphology

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation and inflection in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

Types

Apophon ...

. That is, word roots are not themselves syllables or words, but instead are isolated sets of consonants (usually three, making a so-called '' triliteral root''). Words are composed out of roots not so much by adding prefixes or suffixes, but rather by filling in the vowels ''between'' the root consonants (although prefixes and suffixes are often added as well). For example, in Arabic, the root meaning "write" has the form '' k-t-b''. From this root, words are formed by filling in the vowels and sometimes adding consonants, e.g. كتاب ''kitāb'' "book", كتب ''kutub'' "books", كاتب ''kātib'' "writer", كتّاب ''kuttāb'' "writers", كتب ''kataba'' "he wrote", يكتب ''yaktubu'' "he writes", etc.

Name and identification

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages has been accepted by all scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel. Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages. However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".

The term "Semitic" was created by members of the

The similarity of the Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic languages has been accepted by all scholars since medieval times. The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel. Almost two centuries later, Hiob Ludolf described the similarities between these three languages and the Ethiopian Semitic languages. However, neither scholar named this grouping as "Semitic".

The term "Semitic" was created by members of the Göttingen School of History

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The or ...

, initially by August Ludwig von Schlözer

August Ludwig von Schlözer (5 July 1735, in Gaggstatt – 9 September 1809, in Göttingen) was a German historian and pedagogist who laid foundations for the critical study of Russian medieval history. He was a member of the Göttingen Scho ...

(1781), to designate the languages closely related to Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew. The choice of name was derived from Shem

Shem (; he, שֵׁם ''Šēm''; ar, سَام, Sām) ''Sḗm''; Ge'ez: ሴም, ''Sēm'' was one of the sons of Noah in the book of Genesis and in the book of Chronicles, and the Quran.

The children of Shem were Elam, Ashur, Arphaxad, Lu ...

, one of the three sons of Noah in the genealogical accounts of the biblical Book of Genesis, or more precisely from the Koine Greek rendering of the name, . Johann Gottfried Eichhorn is credited with popularising the term, particularly via a 1795 article "Semitische Sprachen" (''Semitic languages'') in which he justified the terminology against criticism that Hebrew and Canaanite were the same language despite Canaan being " Hamitic" in the Table of Nations:

Previously these languages had been commonly known as the "" in European literature. In the 19th century, "Semitic" became the conventional name; however, an alternative name, "", was later introduced by James Cowles Prichard

James Cowles Prichard, FRS (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British physician and ethnologist with broad interests in physical anthropology and psychiatry. His influential ''Researches into the Physical History of Mankind'' touched ...

and used by some writers.

History

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples

Semitic languages were spoken and written across much of the Middle East and Asia Minor during theBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

and Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

, the earliest attested being the East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced b ...

Akkadian of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

( Akkad, Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

, Isin, Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

and Babylonia) from the third millennium BC

The 3rd millennium BC spanned the years 3000 through 2001 BC. This period of time corresponds to the Early to Middle Bronze Age, characterized by the early empires in the Ancient Near East. In Ancient Egypt, the Early Dynastic Period is followe ...

.

The origin of Semitic-speaking peoples is still under discussion. Several locations were proposed as possible sites of a prehistoric origin of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, the Levant, Ethiopia the Eastern Mediterranean region, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa. Some claim that the Semitic languages originated in the Levant around 3800 BC, and were introduced to the Horn of Africa at about 800 BC from the southern Arabian peninsula, and to North Africa via Phoenician colonists at approximately the same time. Others assign the arrival of Semitic speakers in the Horn of Africa to a much earlier date and many scholars now think that Semitic originated from an offshoot of a still earlier language in North Africa perhaps in the southeastern Sahara and it might have been the process desertization that forced its inhabitants to migrate in the fourth millennium BC some southeast into what is now Ethiopia, others northwest out of Africa into Canaan, Syria and the Mesopotamian valley

The various extremely closely related and mutually intelligible Canaanite languages, a branch of the Northwest Semitic languages included Amorite, first attested in the 21st century BC, Edomite, Hebrew, Ammonite, Moabite, Phoenician (Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of t ...

/ Carthaginian), Samaritan Hebrew, Ekron

Ekron (Philistine: 𐤏𐤒𐤓𐤍 ''*ʿAqārān'', he, עֶקְרוֹן, translit=ʿEqrōn, ar, عقرون), in the Hellenistic period known as Accaron ( grc-gre, Ακκαρων, Akkarōn}) was a Philistine city, one of the five cities o ...

ite, Amalekite and Sutean

The Suteans (Akkadian: ''Sutī’ū'', possibly from Amorite: ''Šetī’u'') were a Semitic people who lived throughout the Levant, Canaan and Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian period. Unlike Amorites, they were not governed by a king. They ...

. They were spoken in what is today Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, the northern Sinai peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is ...

, some northern and eastern parts of the Arabian peninsula, southwest fringes of Turkey, and in the case of Phoenician, coastal regions of Tunisia ( Carthage), Libya, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

and parts of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and possibly in Malta and other Mediterranean islands. Ugaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic language, classified by some as a dialect of the Amorite language and so the only known Amorite dialect preserved in writing. It is known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologist ...

, a Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze A ...

language closely related to but distinct from the Canaanite group was spoken in the kingdom of Ugarit in north western Syria.

A hybrid Canaano-Akkadian language also emerged in Canaan (Israel, Jordan, Lebanon) during the 14th century BC, incorporating elements of the Mesopotamian East Semitic Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia with the West Semitic Canaanite languages.

Aramaic, a still living ancient Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze A ...

language, first attested in the 12th century BC in the northern Levant, gradually replaced the East Semitic and Canaanite languages across much of the Near East, particularly after being adopted as the lingua franca of the vast Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) by Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, T ...

during the 8th century BC, and being retained by the succeeding Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid Empires.

The ''Chaldean language'' (not to be confused with Aramaic or its Biblical variant, sometimes referred to as ''Chaldean'') was a Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze A ...

language, possibly closely related to Aramaic, but no examples of the language remain, as after settling in south eastern Mesopotamia from the Levant during the 9th century BC, the Chaldeans appear to have rapidly adopted the Akkadian and Aramaic languages of the indigenous Mesopotamians.

Old South Arabian languages (classified as South Semitic and therefore distinct from the Central-Semitic Arabic) were spoken in the kingdoms of Dilmun, Meluhha

or ( sux, ) is the Sumerian language, Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley civilisation.

Etymolo ...

, Sheba

Sheba (; he, ''Šəḇāʾ''; ar, سبأ ''Sabaʾ''; Ge'ez: ሳባ ''Saba'') is a kingdom mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the Quran. Sheba features in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions, particularly the Ethiopian Orth ...

, Ubar, Socotra and Magan

Magan may refer to:

Places

*Magan (civilization), also written Makan or Makkan, an ancient region referred to in Sumerian texts

*Magan, Russia, a rural locality (a ''selo'') in the Sakha Republic, Russia

*Magan Airport, an airport in the Sakha Re ...

, which in modern terms encompassed part of the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, Qatar, Oman and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

. South Semitic languages are thought to have spread to the Horn of Africa circa 8th century BC where the Ge'ez language emerged (though the direction of influence remains uncertain).

Common Era

Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, a 5th-century BC Mesopotamian ( Assyrian) descendant of Aramaic used in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

, northeastern Syria, and south east Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

, rose to importance as a literary language of early Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

in the third to fifth centuries and continued into the early Islamic era.

The Arabic language, although originating in the Arabian Peninsula, first emerged in written form in the 1st to 4th centuries CE in the southern regions of The Levant. With the advent of the early Arab conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries, Classical Arabic eventually replaced many (but not all) of the indigenous Semitic languages and cultures of the Near East. Both the Near East and North Africa saw an influx of Muslim Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula, followed later by non-Semitic Muslim Iranian and Turkic peoples. The previously dominant Aramaic dialects maintained by the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians gradually began to be sidelined, however descendant dialects of Eastern Aramaic

The Eastern Aramaic languages have developed from the varieties of Aramaic that developed in and around Mesopotamia (Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and northwest and southwest Iran), as opposed to western varieties of the Levant (modern ...

(including the Akkadian influenced Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo

Turoyo ( syr, ܛܘܪܝܐ) (''Ṭūr ‘Abdinian Aramaic''), also referred to as modern Surayt ( syr, ܣܘܪܝܬ), or modern Suryoyo ( syr, ܣܘܪܝܝܐ), is a Central Neo-Aramaic language traditionally spoken in the Tur Abdin region in southeas ...

and Mandaic) survive to this day among the Assyrians and Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. ...

of northern and southern Iraq, northwestern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, with up to a million fluent speakers. Eastern Aramic is a recognized language in Iraq, furthermore, Mesopotamian Arabic is the most Aramaic-Syriac influenced dialect of Arabic, due to Aramaic-Syriac having originated in Mesopotamia. Meanwhile Western Aramaic is now only spoken by a few thousand Aramean Syriac Christians in western Syria. The Arabs spread their Central Semitic language to North Africa (Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria t ...

and northern Sudan and Mauritania), where it gradually replaced Egyptian Coptic and many Berber languages (although Berber is still largely extant in many areas), and for a time to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

) and Malta.

liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

status, Arabic rapidly became one of the world's main literary languages. Its spread among the masses took much longer, however, as many (although not all) of the native populations outside the Arabian Peninsula only gradually abandoned their languages in favour of Arabic. As Bedouin tribes settled in conquered areas, it became the main language of not only central Arabia, but also Yemen, the Fertile Crescent, and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

. Most of the Maghreb followed, specifically in the wake of the Banu Hilal's incursion in the 11th century, and Arabic became the native language of many inhabitants of al-Andalus. After the collapse of the Nubian kingdom of Dongola in the 14th century, Arabic began to spread south of Egypt into modern Sudan; soon after, the Beni Ḥassān

Beni Ḥassan ( ar, بني حسان "Children of Ḥassān") is a nomadic group of Arabian origin, one of the four sub-tribes of the Maqil Arab tribes who emigrated in the 10th century to the Maghreb with the Bani Hilal and Banu Sulaym tribes.

...

brought Arabization to Mauritania. A number of Modern South Arabian languages distinct from Arabic still survive, such as Soqotri, Mehri and Shehri which are mainly spoken in Socotra, Yemen and Oman.

Meanwhile, the Semitic languages that had arrived from southern Arabia in the 8th century BC were diversifying in Ethiopia and Eritrea, where, under heavy Cushitic influence, they split into a number of languages, including Amharic and Tigrinya

(; also spelled Tigrigna) is an Ethio-Semitic language commonly spoken Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia's Tigray Region by the Tigrinya and Tigrayan peoples. It is also spoken by the global diaspora of these regions.

History and literatur ...

. With the expansion of Ethiopia under the Solomonic dynasty, Amharic, previously a minor local language, spread throughout much of the country, replacing both Semitic (such as Gafat) and non-Semitic (such as Weyto) languages, and replacing Ge'ez as the principal literary language (though Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for Christians in the region); this spread continues to this day, with Qimant set to disappear in another generation.

Present situation

Maltese language

Maltese ( mt, Malti, links=no, also ''L-Ilsien Malti'' or '), is a Semitic language derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance superstrata spoken by the Maltese people. It is the national language of Malta and the only offic ...

is genetically a descendant of the extinct Siculo-Arabic, a variety of Maghrebi Arabic formerly spoken in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. The modern Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as Roman script, is an alphabetic writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae, in southern I ...

with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. Maltese is the only Semitic official language within the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

.

Successful as second languages far beyond their numbers of contemporary first-language speakers, a few Semitic languages today are the base of the sacred literature of some of the world's major religions, including Islam (Arabic), Judaism (Hebrew and Aramaic), churches of Syriac Christianity (Syriac) and Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Christianity (Ge'ez). Millions learn these as a second language (or an archaic version of their modern tongues): many Muslims learn to read and recite the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

and Jews speak and study Biblical Hebrew, the language of the Torah, Midrash, and other Jewish scriptures. Ethnic Assyrian followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Ancient Church of the East

The Ancient Church of the East is an Eastern Christian denomination. It branched from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964, under the leadership of Mar Thoma Darmo (d. 1969). It is one of three Assyrian Churches that claim continuity with t ...

, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church

The Assyrian Evangelical Church is a Presbyterian church in the Middle East that attained a status of ecclesiastical independence from the Presbyterian mission in Iran in 1870.

Members

Its members are predominantly ethnic Assyrians, an Eastern ...

and Assyrian members of the Syriac Orthodox Church both speak Mesopotamian eastern Aramaic and use it also as a liturgical tongue. The language is also used liturgically by the primarily Arabic-speaking followers of the Maronite, Syriac Catholic Church and some Melkite Christians. Greek and Arabic are the main liturgical languages of Oriental Orthodox Christians in the Middle East, who compose the patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. Mandaic is both spoken and used as a liturgical language by the Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. ...

.

Despite the ascendancy of Arabic in the Middle East, other Semitic languages still exist. Biblical Hebrew, long extinct as a colloquial language and in use only in Jewish literary, intellectual, and liturgical activity, was revived in spoken form at the end of the 19th century. Modern Hebrew is the main language of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, with Biblical Hebrew remaining as the language of liturgy and religious scholarship of Jews worldwide.

Ethnic groups, in particular the Assyrians, Kurdish Jews, and Gnostic Mandeans, continue to speak and write Mesopotamian Aramaic languages, particularly Neo-Aramaic languages

The Neo-Aramaic or Modern Aramaic languages are varieties of Aramaic that evolved during the late medieval and early modern periods, and continue to the present day as vernacular (spoken) languages of modern Aramaic-speaking communities. Within ...

descended from Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, in those areas roughly corresponding to Kurdistan ( northern Iraq, northeast Syria, south eastern Turkey and northwestern Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

). Syriac language itself, a descendant of Eastern Aramaic languages

The Eastern Aramaic languages have developed from the varieties of Aramaic that developed in and around Mesopotamia (Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and northwest and southwest Iran), as opposed to western varieties of the Levant (modern ...

(Mesopotamian Old Aramaic), is used also liturgically by the Syriac Christians throughout the area. Although the majority of Neo-Aramaic dialects spoken today are descended from Eastern varieties, Western Neo-Aramaic

Western Neo-Aramaic (), more commonly referred to as Siryon ( "Syrian"), is a modern Western Aramaic language. Today, it is only spoken in three villages – Maaloula, Bakhah and Jubb'adin – in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains of western Syria. W ...

is still spoken in 3 villages in Syria.

In Arab-dominated Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and Oman, on the southern rim of the Arabian Peninsula, a few tribes continue to speak Modern South Arabian languages such as Mahri and Soqotri. These languages differ greatly from both the surrounding Arabic dialects and from the (unrelated but previously thought to be related) languages of the Old South Arabian

Old South Arabian (or Ṣayhadic or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages spoken in the far southern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. They were written in the Ancient South Arabian script.

There were a number of othe ...

inscriptions.

Historically linked to the peninsular homeland of Old South Arabian, of which only one language, Razihi, remains, Ethiopia and Eritrea contain a substantial number of Semitic languages; the most widely spoken are Amharic in Ethiopia, Tigre in Eritrea, and Tigrinya

(; also spelled Tigrigna) is an Ethio-Semitic language commonly spoken Eritrea and in northern Ethiopia's Tigray Region by the Tigrinya and Tigrayan peoples. It is also spoken by the global diaspora of these regions.

History and literatur ...

in both. Amharic is the official language of Ethiopia. Tigrinya is a working language in Eritrea. Tigre is spoken by over one million people in the northern and central Eritrean lowlands and parts of eastern Sudan. A number of Gurage languages are spoken by populations in the semi-mountainous region of central Ethiopia, while Harari is restricted to the city of Harar. Ge'ez remains the liturgical language for certain groups of Christians in Ethiopia and in Eritrea.

Phonology

The phonologies of the attested Semitic languages are presented here from acomparative

general linguistics, the comparative is a syntactic construction that serves to express a comparison between two (or more) entities or groups of entities in quality or degree - see also comparison (grammar) for an overview of comparison, as well ...

point of view. See Proto-Semitic language#Phonology for details on the phonological reconstruction of Proto-Semitic used in this article. The reconstruction of Proto-Semitic (PS) was originally based primarily on Arabic, whose phonology and morphology (particularly in Classical Arabic) is very conservative, and which preserves as contrastive 28 out of the evident 29 consonantal phonemes. with and merging into Arabic and becoming Arabic .

Note: the fricatives *s, *z, *ṣ, *ś, *ṣ́, *ṱ may also be interpreted as affricates (/t͡s/, /d͡z/, /t͡sʼ/, /t͡ɬ/, /t͡ɬʼ/, /t͡θʼ/), as discussed in .

This comparative approach is natural for the consonants, as sound correspondences among the consonants of the Semitic languages are very straightforward for a family of its time depth. Sound shifts affecting the vowels are more numerous and, at times, less regular.

Consonants

Each Proto-Semitic phoneme was reconstructed to explain a certain regular sound correspondence between various Semitic languages. Note that Latin letter values (''italicized'') for extinct languages are a question of transcription; the exact pronunciation is not recorded. Most of the attested languages have merged a number of the reconstructed original fricatives, though South Arabian retains all fourteen (and has added a fifteenth from *p > f). In Aramaic and Hebrew, all non-emphatic stops occurring singly after a vowel were softened to fricatives, leading to an alternation that was often later phonemicized as a result of the loss of gemination. In languages exhibiting pharyngealization of emphatics, the original velar emphatic has rather developed to auvular

Uvulars are consonants articulated with the back of the tongue against or near the uvula, that is, further back in the mouth than velar consonants. Uvulars may be stops, fricatives, nasals, trills, or approximants, though the IPA does not prov ...

stop .

Note: the fricatives *s, *z, *ṣ, *ś, *ṣ́, *ṱ may also be interpreted as affricates (/t͡s/, /d͡z/, /t͡sʼ/, /t͡ɬ/, /t͡ɬʼ/, /t͡θʼ/).Notes: # Proto-Semitic was still pronounced as in Biblical Hebrew, but no letter was available in the Early Linear Script, so the letter ש did double duty, representing both and . Later on, however, merged with , but the old spelling was largely retained, and the two pronunciations of ש were distinguished graphically in

Tiberian Hebrew

Tiberian Hebrew is the canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) committed to writing by Masoretic scholars living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee under the Abbasid Caliphate. They wrote in the form of Tiberian ...

as שׁ vs. שׂ < .

# Biblical Hebrew as of the 3rd century BCE apparently still distinguished the phonemes and from and , respectively, based on transcriptions in the Septuagint. As in the case of , no letters were available to represent these sounds, and existing letters did double duty: ח and ע . In both of these cases, however, the two sounds represented by the same letter eventually merged, leaving no evidence (other than early transcriptions) of the former distinctions.

# Although early Aramaic (pre-7th century BCE) had only 22 consonants in its alphabet, it apparently distinguished all of the original 29 Proto-Semitic phonemes, including , , , , , and although by Middle Aramaic times, these had all merged with other sounds. This conclusion is mainly based on the shifting representation of words etymologically containing these sounds; in early Aramaic writing, the first five are merged with , , , , , respectively, but later with , , , , . (Also note that due to begadkefat spirantization, which occurred after this merger, OAm. t > ṯ and d > ḏ in some positions, so that PS *t,ṯ and *d, ḏ may be realized as either of t, ṯ and d, ḏ respectively.) The sounds and were always represented using the pharyngeal letters , but they are distinguished from the pharyngeals in the Demotic-script papyrus Amherst 63, written about 200 BCE. This suggests that these sounds, too, were distinguished in Old Aramaic language, but written using the same letters as they later merged with.

# The earlier pharyngeals can be distinguished in Akkadian from the zero reflexes of *ḥ, *ʕ by e-coloring adjacent *a, e.g. pS ''*ˈbaʕal-um'' 'owner, lord' > Akk. ''bēlu(m)''.

# Hebrew and Aramaic underwent begadkefat spirantization at a certain point, whereby the stop sounds were softened to the corresponding fricatives (written ''ḇ ḡ ḏ ḵ p̄ ṯ'') when occurring after a vowel and not geminated. This change probably happened after the original Old Aramaic phonemes disappeared in the 7th century BCE, and most likely occurred after the loss of Hebrew c. 200 BCE. It is known to have occurred in Hebrew by the 2nd century CE. After a certain point this alternation became contrastive in word-medial and final position (though bearing low functional load), but in word-initial position they remained allophonic. In Modern Hebrew, the distinction has a higher functional load due to the loss of gemination, although only the three fricatives are still preserved (the fricative is pronounced in modern Hebrew).

# In the Northwest Semitic languages, became at the beginning of a word, e.g. Hebrew ''yeled'' "boy" < ''*wald'' (cf. Arabic ''walad'').

# There is evidence of a rule of assimilation of /j/ to the following coronal consonant in pre-tonic position, shared by Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic.

# In Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, is nonexistent. In general cases, the language would lack pharyngeal fricative (as heard in ''Ayin

''Ayin'' (also ''ayn'' or ''ain''; transliterated ) is the sixteenth letter of the Semitic scripts, including Phoenician , Hebrew , Aramaic , Syriac ܥ, and Arabic (where it is sixteenth in abjadi order only).

The letter represen ...

''). However, /ʕ/ is retained in educational speech, especially among Assyrian priests.

#The palatalization of Proto-Semitic gīm to Arabic jīm, is most probably connected to the pronunciation of qāf as a gāf (this sound change also occurred in Yemenite Hebrew

Yemenite Hebrew ( ''ʿĪvrīṯ Tēmŏnīṯ''), also referred to as Temani Hebrew, is the pronunciation system for Hebrew traditionally used by Yemenite Jews. Yemenite Hebrew has been studied by language scholars, many of whom believe it to retai ...

), hence in most of the Arabian peninsula (which is the homeland of the Arabic language) is jīm and is gāf , except in western and southern Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

and parts of Oman where is gīm and is qāf .

# Ugaritic orthography indicated the vowel after the glottal stop.

#The Arabic letter ' () has three main pronunciations in Modern Standard Arabic. in north Algeria, Iraq, also in most of the Arabian peninsula and as the predominant pronunciation of Literary Arabic outside the Arab world, occurs in most of the Levant and most North Africa; and is used in northern Egypt and some regions in Yemen and Oman. In addition to other minor allophones.

#The Arabic letter ' () has three main pronunciations in spoken varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

. in most of the Arabian Peninsula, Northern and Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

Yemen and parts of Oman, Southern Iraq, Upper Egypt, Sudan, Libya, some parts of the Levant and to lesser extent in some parts (mostly rural) of Maghreb. in most of Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, Southern and Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

Yemen and parts of Oman, Northern Iraq, parts of the Levant especially Druze dialects. in most of the Levant and Lower Egypt, as well as some North African towns such as Tlemcen and Fez. In addition to other minor allophones.

#' can be written ', and always is in the Ugaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic language, classified by some as a dialect of the Amorite language and so the only known Amorite dialect preserved in writing. It is known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologist ...

and Arabic contexts. In Ugaritic, sometimes assimilates to ', as in ''ġmʔ'' 'thirsty' (Arabic ''ẓmʔ'', Hebrew ''ṣmʔ'', but Ugaritic ''mẓmủ'' 'thirsty', root ''ẓmʔ'', is also attested).

#Early Amharic might have had a different phonology.

#The pronunciations /ʕ/ and /ħ/ for ''ʿAyin'' and ''Ḥet'', respectively, still occur among some older Mizrahi speakers, but for most modern Israelis, ''ʿAyin'' and ''Ḥet'' are realized as /ʔ, -/ and /χ ~ x/, respectively.

The following table shows the development of the various fricatives in Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic through cognate words:

# possibly affricated (/dz/ /tɬʼ/ /ʦʼ/ /tθʼ/ /tɬ/)

Vowels

Proto-Semitic vowels are, in general, harder to deduce due to thenonconcatenative morphology

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation and inflection in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

Types

Apophon ...

of Semitic languages. The history of vowel changes in the languages makes drawing up a complete table of correspondences impossible, so only the most common reflexes can be given:

# in a stressed open syllable

# in a stressed closed syllable before a geminate

# in a stressed closed syllable before a consonant cluster

# when the proto-Semitic stressed vowel remained stressed

# pS *a,*ā > Akk. e,ē in the neighborhood of pS *ʕ,*ħ and before r.

# i.e. pS *g,*k,*ḳ,*χ > Ge'ez gʷ, kʷ,ḳʷ,χʷ / _u

Grammar

The Semitic languages share a number of grammatical features, although variation — both between separate languages, and within the languages themselves — has naturally occurred over time.Word order

The reconstructed default word order in Proto-Semitic is verb–subject–object (VSO), possessed–possessor (NG), and noun–adjective (NA). This was still the case in Classical Arabic and Biblical Hebrew, e.g. Classical Arabic رأى محمد فريدا ''ra'ā muħammadun farīdan.'' (literally "saw Muhammad Farid", ''Muhammad saw Farid''). In the modern Arabic vernaculars, however, as well as sometimes in Modern Standard Arabic (the modern literary language based on Classical Arabic) and Modern Hebrew, the classical VSO order has given way to SVO. Modern Ethiopian Semitic languages follow a different word order: SOV, possessor–possessed, and adjective–noun; however, the oldest attested Ethiopian Semitic language, Ge'ez, was VSO, possessed–possessor, and noun–adjective. Akkadian was also predominantly SOV.Cases in nouns and adjectives

The proto-Semitic three-case system ( nominative, accusative and genitive) with differing vowel endings (-u, -a -i), fully preserved in Qur'anic Arabic (seeʾIʿrab

(, ) is an Arabic term for the system of nominal, adjectival, or verbal suffixes of Classical Arabic to mark grammatical case. These suffixes are written in fully vocalized Arabic texts, notably the '' '' or texts written for children or Arabic ...

), Akkadian and Ugaritic

Ugaritic () is an extinct Northwest Semitic language, classified by some as a dialect of the Amorite language and so the only known Amorite dialect preserved in writing. It is known through the Ugaritic texts discovered by French archaeologist ...

, has disappeared everywhere in the many colloquial forms of Semitic languages. Modern Standard Arabic maintains such case distinctions, although they are typically lost in free speech due to colloquial influence. An accusative ending -n is preserved in Ethiopian Semitic. In the northwest, the scarcely attested Samalian reflects a case distinction in the plural between nominative ''-ū'' and oblique ''-ī'' (compare the same distinction in Classical Arabic). Additionally, Semitic nouns and adjectives had a category of state, the indefinite state being expressed by nunation

Nunation ( ar, تَنوِين, ' ), in some Semitic languages such as Literary Arabic, is the addition of one of three vowel diacritics (''ḥarakāt'') to a noun or adjective.

This is used to indicate the word ends in an alveolar nasal without ...

.

Number in nouns

Semitic languages originally had three grammatical numbers: singular, dual, andplural

The plural (sometimes abbreviated pl., pl, or ), in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the default quantity represented by that noun. This de ...

. Classical Arabic still has a mandatory dual (i.e. it must be used in all circumstances when referring to two entities), marked on nouns, verbs, adjectives and pronouns. Many contemporary dialects of Arabic still have a dual, as in the name for the nation of Bahrain (''baħr'' "sea" + ''-ayn'' "two"), although it is marked only on nouns. It also occurs in Hebrew in a few nouns (''šana'' means "one year", ''šnatayim'' means "two years", and ''šanim'' means "years"), but for those it is obligatory. The curious phenomenon of broken plurals – e.g. in Arabic, ''sadd'' "one dam" vs. ''sudūd'' "dams" found most profusely in the languages of Arabia and Ethiopia, may be partly of proto-Semitic origin, and partly elaborated from simpler origins.

Verb aspect and tense

All Semitic languages show two quite distinct styles of morphology used for conjugating verbs. ''Suffix conjugations'' take suffixes indicating the person, number and gender of the subject, which bear some resemblance to the pronominal suffixes used to indicate direct objects on verbs ("I saw him") and possession on nouns ("his dog"). So-called ''prefix conjugations'' actually takes both prefixes and suffixes, with the prefixes primarily indicating person (and sometimes number or gender), while the suffixes (which are completely different from those used in the suffix conjugation) indicate number and gender whenever the prefix does not mark this. The prefix conjugation is noted for a particular pattern of ' prefixes where (1) a ''t-'' prefix is used in the singular to mark the second person and third-person feminine, while a ''y-'' prefix marks the third-person masculine; and (2) identical words are used for second-person masculine and third-person feminine singular. The prefix conjugation is extremely old, with clear analogues in nearly all the families of Afroasiatic languages (i.e. at least 10,000 years old). The table on the right shows examples of the prefix and suffix conjugations in Classical Arabic, which has forms that are close to Proto-Semitic. In Proto-Semitic, as still largely reflected in East Semitic, prefix conjugations are used both for the past and the non-past, with different vocalizations. Cf. Akkadian ''niprus'' "we decided" (preterite), ''niptaras'' "we have decided" (perfect), ''niparras'' "we decide" (non-past or imperfect), vs. suffix-conjugated ''parsānu'' "we are/were/will be deciding" (stative). Some of these features, e.g. gemination indicating the non-past/imperfect, are generally attributed to Afroasiatic. Proto-Semitic had an additional form, the jussive, which was distinguished from the preterite only by the position of stress: the jussive had final stress while the preterite had non-final (retracted) stress. The West Semitic languages significantly reshaped the system. The most substantial changes occurred in the Central Semitic languages (the ancestors of modern Hebrew, Arabic and Aramaic). Essentially, the old prefix-conjugated jussive or preterite became a new non-past (or imperfect), while the stative became a new past (or perfect), and the old prefix-conjugated non-past (or imperfect) with gemination was discarded. New suffixes were used to mark different moods in the non-past, e.g. Classical Arabic ''-u'' (indicative), ''-a'' (subjunctive), vs no suffix (jussive). (It is not generally agreed whether the systems of the various Semitic languages are better interpreted in terms of tense, i.e. past vs. non-past, or aspect, i.e. perfect vs. imperfect.) A special feature in classical Hebrew is the waw-consecutive, prefixing a verb form with the letter waw in order to change its tense oraspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

. The South Semitic languages show a system somewhere between the East and Central Semitic languages.

Later languages show further developments. In the modern varieties of Arabic, for example, the old mood suffixes were dropped, and new mood prefixes developed (e.g. ''bi-'' for indicative vs. no prefix for subjunctive in many varieties). In the extreme case of Neo-Aramaic, the verb conjugations have been entirely reworked under Iranian influence.

Morphology: triliteral roots

All Semitic languages exhibit a unique pattern of stems called Semitic roots consisting typically of triliteral, or three-consonant consonantal roots (two- and four-consonant roots also exist), from which nouns, adjectives, and verbs are formed in various ways (e.g., by inserting vowels, doubling consonants, lengthening vowels or by adding prefixes, suffixes, or infixes). For instance, the root k-t-b, (dealing with "writing" generally) yields in Arabic: :''katabtu'' كَتَبْتُ or كتبت "I wrote" (f and m) :''yuktab(u)'' يُكْتَبُ or يكتب "being written" (masculine) :''tuktab(u)'' تُكتَبُ or تكتب "being written" (feminine) :''yatakātabūn(a)'' يَتَكَاتَبُونَ or يتكاتبون "they write to each other" (masculine) :''istiktāb'' اِسْتِكْتابَ or استكتاب "causing to write" :''kitāb'' كِتابٌ or كتاب "book" (the hyphen shows end of stem before various case endings) :''kutayyib'' كُتَيِّبٌ or كتيب "booklet" (diminutive) :''kitābah'' كِتابةٌ or كتابة "writing" :''kuttāb'' كُتّابٌ or كتاب "writers" (broken plural) :''katabah'' كَتَبةٌ or كتبة "clerks" (broken plural) :''maktab'' مَكْتَبٌ or مكتب "desk" or "office" :''maktabah'' مَكْتَبةٌ or مكتبة "library" or "bookshop" :''maktūb'' مَكْتُوبٌ or مكتوب "written" (participle) or "postal letter" (noun) :''katībah'' كَتِيبةٌ or كتيبة "squadron" or "document" :''iktitāb'' اِكْتِتابٌ or اكتتاب "registration" or "contribution of funds" :''muktatib'' مُكتَتِبٌ or مكتتب "subscription" and the same root in Hebrew: (A line under k and b mean a fricative, x for k and v for b.) :''kāṯaḇti'' כָּתַבְתִּי or כתבתי "I wrote" :''kattāḇ'' כַּתָּב or כתב "reporter" (''m'') :''katteḇeṯ'' כַּתָּבֶת or כתבת "reporter" (''f'') :''kattāḇā'' כַּתָּבָה or כתבה "article" :''miḵtāḇ'' מִכְתָּב or מכתב "postal letter" :''miḵtāḇā'' מִכְתָבָה or מכתבה "writing desk" :''kəṯōḇeṯ'' כְּתֹבֶת or כתבת "address" :''kəṯāḇ'' כְּתָב or כתב "handwriting" :''kāṯūḇ'' כָּתוּב or כתוב "written" :''hiḵtīḇ'' הִכְתִּיב or הכתיב "he dictated" :''hiṯkattēḇ'' הִתְכַּתֵּב or התכתב "he corresponded :''niḵtaḇ'' נִכְתָּב or נכתב "it was written" (''m'') :''kəṯīḇ'' כְּתִיב or כתיב "spelling" (''m'') :''taḵtīḇ'' תַּכְתִּיב or תכתיב "prescript" (''m'') :''m''ə''ḵuttāḇ'' מְכוּתָּב or מכותב "addressee" :''kəṯubbā'' כְּתֻבָּה or כתבה "ketubah (a Jewish marriage contract)" (''f'') In Tigrinya and Amharic, this root was used widely but is now seen as an archaic form. Ethiopic-derived languages use different roots for things that have to do with writing (and in some cases counting). The primitive root ṣ-f and the trilateral root stems m-ṣ-f, ṣ-h-f, and ṣ-f-r are used. This root also exists in other Semitic languages, such as Hebrew: ''sep̄er'' "book", '' sōp̄er'' "scribe", ''mispār'' "number" and ''sippūr'' "story". This root also exists in Arabic and is used to form words with a close meaning to "writing", such as ''ṣaḥāfa'' "journalism", and ''ṣaḥīfa'' "newspaper" or "parchment". Verbs in other non-Semitic Afroasiatic languages show similar radical patterns, but more usually with biconsonantal roots; e.g. Kabyle ''afeg'' means "fly!", while ''affug'' means "flight", and ''yufeg'' means "he flew" (compare with Hebrew, where ''hap̄lēḡ'' means "set sail!", ''hap̄lāḡā'' means "a sailing trip", and ''hip̄līḡ'' means "he sailed", while the unrelated ''ʕūp̄'', ''təʕūp̄ā'' and ''ʕāp̄'' pertain to flight).Independent personal pronouns

Cardinal numerals

These are the basic numeral stems without feminine suffixes. Note that in most older Semitic languages, the forms of the numerals from 3 to 10 exhibit polarity of gender (also called "chiastic concord" or "reverse agreement"), i.e. if the counted noun is masculine, the numeral would be feminine and vice versa.Typology

Some early Semitic languages are speculated to have had weak ergative features.Common vocabulary

Due to the Semitic languages' common origin, they share some words and roots. Others differ. For example: Terms given in brackets are not derived from the respective Proto-Semitic roots, though they may also derive from Proto-Semitic (as does e.g. Arabic ''dār'', cf. Biblical Hebrew ''dōr'' "dwelling"). Sometimes, certain roots differ in meaning from one Semitic language to another. For example, the root ''b-y-ḍ'' in Arabic has the meaning of "white" as well as "egg", whereas in Hebrew it only means "egg". The root ''l-b-n'' means "milk" in Arabic, but the color "white" in Hebrew. The root ''l-ḥ-m'' means "meat" in Arabic, but "bread" in Hebrew and "cow" in Ethiopian Semitic; the original meaning was most probably "food". The word ''medina'' (root: d-y-n/d-w-n) has the meaning of "metropolis" in Amharic, "city" in Arabic and Ancient Hebrew, and "State" in Modern Hebrew. Of course, there is sometimes no relation between the roots. For example, "knowledge" is represented in Hebrew by the root ''y-d-ʿ'', but in Arabic by the roots ''ʿ-r-f'' and ''ʿ-l-m'' and in Ethiosemitic by the roots ''ʿ-w-q'' and ''f-l-ṭ''. For more comparative vocabulary lists, see Wiktionary appendices:List of Proto-Semitic stems

Swadesh lists for Afro-Asiatic languages

Classification

There are six fairly uncontroversial nodes within the Semitic languages:East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced b ...

, Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze A ...

, North Arabian, Old South Arabian

Old South Arabian (or Ṣayhadic or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages spoken in the far southern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. They were written in the Ancient South Arabian script.

There were a number of othe ...

(also known as Sayhadic), Modern South Arabian, and Ethiopian Semitic. These are generally grouped further, but there is ongoing debate as to which belong together. The classification based on shared innovations given below, established by Robert Hetzron in 1976 and with later emendations by John Huehnergard and Rodgers as summarized in Hetzron 1997, is the most widely accepted today. In particular, several Semiticists still argue for the traditional (partially nonlinguistic) view of Arabic as part of South Semitic, and a few (e.g. Alexander Militarev or the German-Egyptian professor Arafa Hussein Mustafa,) see the South Arabian languages, as a third branch of Semitic alongside East and West Semitic, rather than as a subgroup of South Semitic. However, a new classification groups Old South Arabian as Central Semitic instead.

Roger Blench notes, that the Gurage languages are highly divergent and wonders whether they might not be a primary branch, reflecting an origin of Afroasiatic in or near Ethiopia. At a lower level, there is still no general agreement on where to draw the line between "languages" and "dialects" an issue particularly relevant in Arabic, Aramaic and Gurage and the strong mutual influences between Arabic dialects render a genetic subclassification of them particularly difficult.

A computational phylogenetic analysis by Kitchen et al. (2009), considers the Semitic languages to have originated in the Levant about 5,750 years ago during the Early Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

, with early Ethiosemitic originating from southern Arabia approximately 2,800 years ago. Evidence for gene movements consistent with this were found in Almarri et al. (2021).

The Himyaritic and Sutean languages appear to have been Semitic, but are unclassified due to insufficient data.

* East Semitic

The East Semitic languages are one of three divisions of the Semitic languages. The East Semitic group is attested by three distinct languages, Akkadian, Eblaite and possibly Kishite, all of which have been long extinct. They were influenced b ...

(†)

* West Semitic

** Central Semitic

*** Northwest Semitic

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze A ...

*** Arabic

** South Semitic

South Semitic is a putative branch of the Semitic languages, which form a branch of the larger Afro-Asiatic language family, found in (North and East) Africa and Western Asia.

History

The "homeland" of the South Semitic languages is widely ...

*** Western: Ethiopian Semitic and Old South Arabian

Old South Arabian (or Ṣayhadic or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages spoken in the far southern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. They were written in the Ancient South Arabian script.

There were a number of othe ...

*** Eastern: Modern South Arabian

Semitic-speaking peoples

The following is a list of some modern and ancient Semitic-speaking peoples and nations:Central Semitic

* Ammonite speakers of Ammon * Amorites 20th century BC * Arabs * Ancient North Arabian-speaking bedouins * Arameans 16th to 8th centuries BC / Akhlames (Ahlamu) 14th century BC. * Canaanite-speaking nations of the early Iron Age: * Chaldea appeared in southern Mesopotamia c. 1000 BC and eventually disappeared into the general Babylonian population. *Edom

Edom (; Edomite: ; he, אֱדוֹם , lit.: "red"; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom in Transjordan, located between Moab to the northeast, the Arabah to the west, and the Arabian Desert to the south and east.N ...

ites

* Hebrews/ Israelites founded the nation of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

which later split into the Kingdoms of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Judah. The remnants of these people became the Jews and the Samaritans.

* Maltese

* Mandaeans

Mandaeans ( ar, المندائيون ), also known as Mandaean Sabians ( ) or simply as Sabians ( ), are an ethnoreligious group who are followers of Mandaeism. They believe that John the Baptist was the final and most important prophet. ...

* Moab

* Nabataeans

* Phoenicia founded Mediterranean colonies including Tyre, Sidon and ancient Carthage. The remnants of these people became the modern inhabitants of Lebanon.

* Ugarit, 14th to 12th centuries BC

* Nasrani (Syrian Christian)

East Semitic

* Akkadian Empire ancient Semitic speakers moved into Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium BC and settled among the local peoples of Sumer. *Babylonian Empire

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

*Assyrian Empire

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyr ...

* Ebla 23rd century BC

South Semitic

* Kingdom of Aksum 4th century BC to 7th century AD * Amhara people * Argobba people * Dahalik people *Gurage people

The Gurage (, Gurage: ጉራጌ) are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia.G. W. E. Huntingford, "William A. Shack: The Gurage: a people of the ensete culture" They inhabit the Gurage Zone, a fertile, semi-mountainous region in ce ...

* Harari people

* Mehri people

* Old South Arabian

Old South Arabian (or Ṣayhadic or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages spoken in the far southern portion of the Arabian Peninsula. They were written in the Ancient South Arabian script.

There were a number of othe ...

-speaking peoples

* Sabaeans of Yemen 9th to 1st centuries BC

* Silt'e people

* Tigrigna People

* Tigray people

Tigrayans ( ti, ተጋሩ) are a Semitic-speaking ethnic group indigenous to the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia. They speak the Tigrinya language, an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Ethiopian Semitic branch.

The daily life of Tigra ...

* Tigre people

* Zay people

Unknown

* Suteans 14th century BC *Thamud

The Thamud ( ar, ثَمُوْد, translit=Ṯamūd) were an ancient Arabian tribe or tribal confederation that occupied the northwestern Arabian peninsula between the late-eighth century BCE, when they are attested in Assyrian sources, and the ...

2nd to 5th centuries AD

See also

* Proto-Semitic language * Middle Bronze Age alphabetsNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Mustafa, Arafa Hussein. 1974. ''Analytical study of phrases and sentences in epic texts of Ugarit.'' (German title: Untersuchungen zu Satztypen in den epischen Texten von Ugarit). Dissertation. Halle-Wittenberg: Martin-Luther-University. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * 002 edition:External links

Semitic genealogical tree

(as well as the Afroasiatic one), presented by

Alexander Militarev

Alexander Militarev (russian: link=no, Алекса́ндр Ю́рьевич Милитарёв; born January 14, 1943) is a Russian scholar of Semitic, Berber, Canarian and Afroasiatic (Afrasian, Semito-Hamitic) languages, comparative-histori ...

at his talk "Genealogical classification of Afro-Asiatic languages according to the latest data" (at the conference on the 70th anniversary of Vladislav Illich-Svitych

Vladislav Markovich Illich-Svitych (russian: Владисла́в Ма́ркович И́ллич-Сви́тыч, also transliterated as Illič-Svityč; September 12, 1934 – August 22, 1966) was a Soviet linguist and accentologist. He was a fo ...

, Moscow, 2004short annotations of the talks given there

''Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural''

* [https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02113751 '' Alexis Neme and Sébastien Paumier (2019), Restoring Arabic vowels through omission-tolerant dictionary lookup, Lang Resources & Evaluation, Vol 53, 1–65 pages'']

Swadesh vocabulary lists of Semitic languages

(from Wiktionary'

Swadesh-list appendix

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 Afroasiatic languages Aramaic languages Arabic language Hebrew language Amharic language Ge'ez language Phoenician language Akkadian language