James Wilkes Maurice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vice-Admiral James Wilkes Maurice (10 February 1775 – 4 September 1857) was an officer of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

during the French Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Unlike his contemporaries who won fame commanding ships, Maurice gained accolades for his command of a number of island fortresses.

Maurice was employed on a number of ships prior to the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, and by 1794 held the position of midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

. He saw action in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

the following year, participating in the Battle of Groix

The Battle of Groix was a large naval engagement which took place near the island of Groix off the Biscay coast of Brittany on 23 June 1795 ( 5 messidor an III) during the French Revolutionary Wars. The battle was fought between elements of the ...

and the Quiberon expedition. Good service in these actions led to his appointment to a number of acting commissions as a lieutenant. His career took a major step forward when Maurice, his lieutenant's commission by now confirmed, went out to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

with Commodore Sir Samuel Hood

Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood (12 December 1724 – 27 January 1816) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. As a junior officer he saw action during the War of the Austrian Succession. While in temporary command of , he drove a French ship ashore i ...

.

Hood had decided to fortify Diamond Rock

Diamond Rock (french: rocher du Diamant) is a 175-metre-high (574 ft)Fort de France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label= Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the Caribbean.

Histo ...

in Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

and Maurice, as first lieutenant of Hood's flagship, began to oversee the arduous task. After work was completed Hood commissioned the Rock and rewarded Maurice's efforts by putting him in command. For seventeen months Maurice and his men raided and interdicted shipping off Martinique, and proved a continual thorn in the side of the French. The arrival of a large fleet under Pierre de Villeneuve in May 1804 during the Trafalgar Campaign gave the French enough resources to assault the Rock. In the subsequent battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

, Maurice held out for several days until the exhaustion of the Rock's supplies of water and ammunition forced him to surrender.

Maurice spent a brief period in command of a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

, before being appointed governor of Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

, tasked with the defence of the island. His next posting was as governor of Anholt during the Gunboat War

The Gunboat War (, ; 1807–1814) was a naval conflict between Denmark–Norway and the British during the Napoleonic Wars. The war's name is derived from the Danish tactic of employing small gunboats against the materially superior Royal Nav ...

. In 1811 he fought off an attack from a much larger Danish force, inflicting heavy casualties. Maurice then returned to Britain and largely retired from active service, though he continued to be promoted. He reached the rank of vice-admiral before his death in 1857.

Family and early life

Wilkes was born on 10 February 1775 in Devonport,Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

. He was nominally entered onto the books of Lieutenant James Glassford's in 1783, but did not actually enter the navy until August 1789, when he became an able seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination ...

aboard Captain Alexander Mackey's 14-gun sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

. He served on ''Inspector'' until joining the 74-gun under Captain Thomas Hicks in December 1792. He visited the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

during his time on ''Powerful'', when the ship escorted a convoy of East Indiamen

East Indiaman was a general name for any sailing ship operating under charter or licence to any of the East India trading companies of the major European trading powers of the 17th through the 19th centuries. The term is used to refer to vesse ...

there. Hicks was replaced by Captain William Albany Otway, and ''Powerful'' was ordered to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, but Maurice left the ship before she sailed, having been subpoena

A subpoena (; also subpœna, supenna or subpena) or witness summons is a writ issued by a government agency, most often a court, to compel testimony by a witness or production of evidence under a penalty for failure. There are two common types of ...

ed to give evidence in a case concerning a warrant officer accused of embezzling stores. By the time his services were no longer required Maurice found himself unable to rejoin his ship and instead joined the 80-gun under Captain Richard Boyer in January 1794. ''Cambridge'' was based at Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

with the Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

, and in May Maurice transferred to another ship on the station, the 32-gun under Captain Sir Richard Strachan.

Maurice remained with ''Concorde'' after Captain Anthony Hunt replaced Strachan and served in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

based out of Falmouth. Maurice saw action at the Battle of Groix

The Battle of Groix was a large naval engagement which took place near the island of Groix off the Biscay coast of Brittany on 23 June 1795 ( 5 messidor an III) during the French Revolutionary Wars. The battle was fought between elements of the ...

on 23 June 1795 and then during the Quiberon expedition under Commodore Sir John Borlase Warren

Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, 1st Baronet (2 September 1753 – 27 February 1822) was a British Royal Navy officer, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1774 and 1807.

Naval career

Born in Stapleford, Nottinghamsh ...

. Warren gave Maurice an acting commission as a lieutenant in August aboard the 74-gun under Captain Albemarle Bertie. Maurice returned to ''Concorde'' in January 1796, serving at first under his old captain Hunt, and when he was replaced, under Captain Richard Bagot. He was briefly aboard Lord Bridport's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, the 100-gun for three weeks in February 1797, before taking an acting commission aboard the 80-gun , a commission confirmed by the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

on 3 April 1797.

He was lieutenant aboard the 74-gun between 17 January 1799 and May 1802. The ''Canada'' was at the time the flagship of Commodore Sir John Borlase Warren, and served in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and off Minorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capita ...

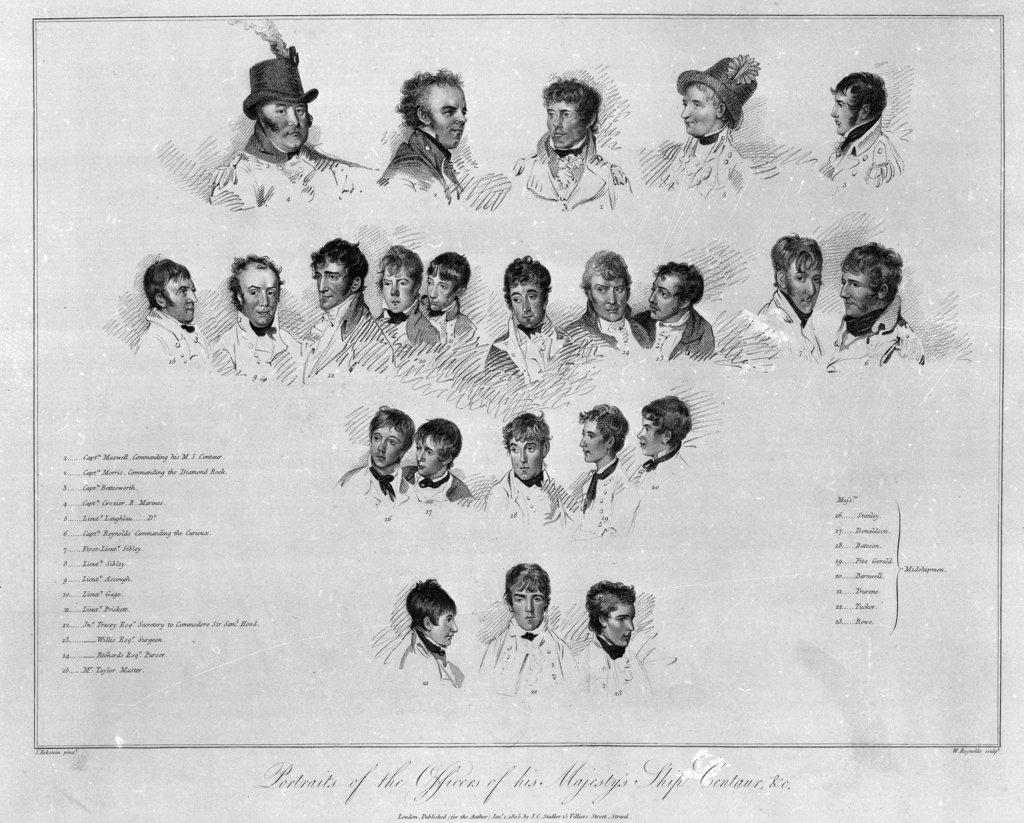

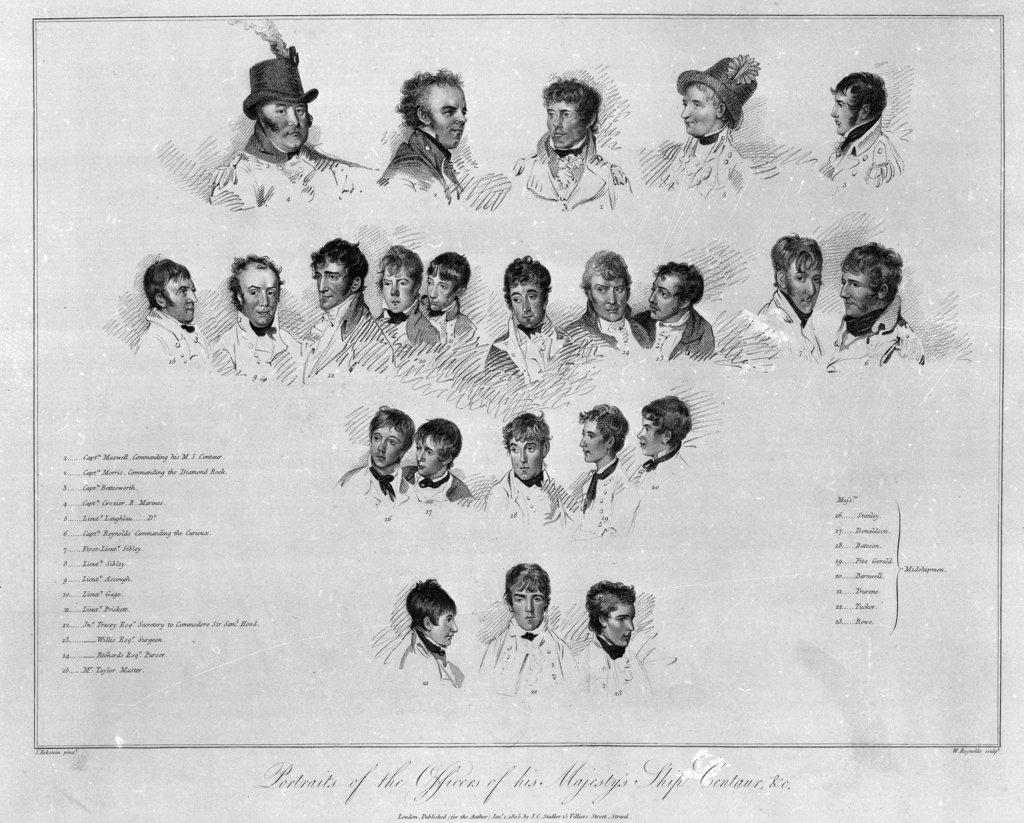

. In late summer 1802 he was moved to become first lieutenant of the 74-gun , captained by Murray Maxwell and the flagship of Commodore Sir Samuel Hood

Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood (12 December 1724 – 27 January 1816) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. As a junior officer he saw action during the War of the Austrian Succession. While in temporary command of , he drove a French ship ashore i ...

. ''Centaur'' went out to the West Indies and aboard her, Maurice was present at the reduction and capture of the French and Dutch possessions of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

, Tobago

Tobago () is an List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, island and Regions and municipalities of Trinidad and Tobago, ward within the Trinidad and Tobago, Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trini ...

, Demerara

Demerara ( nl, Demerary, ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state fro ...

and Essequibo. He was landed with a party at Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

on 26 November 1803 with orders to destroy the battery at Petite Anse d'Arlet, but was badly wounded when the battery's magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

exploded. The Lloyd's Patriotic Fund Lloyd's Patriotic Fund was founded on 28 July 1803 at Lloyd's Coffee House, and continues to the present day. Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund now works closely with armed forces charities to identify the individuals and their families who are in urgent ne ...

awarded him a sword valued at £50 as a reward for his services.

Maurice on Diamond Rock

Hood had by late 1803 decided to move against the two last remaining French naval bases in the Caribbean, atGuadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

and Martinique. Large numbers of privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s used the ports on the islands as a base from which to operate against British merchant shipping in the Caribbean. They had captured a number of valuable cargoes and were diverting British warships to protect the merchant fleets. Hood decided to blockade Martinique, and thus curtail the privateers and intercept supplies destined for the French garrison. Patrolling off the bay at the southern end of the island, in which one of Martinique's two main ports, Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a Communes of France, commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the ...

, was located, Hood saw that if the British could occupy Diamond Rock

Diamond Rock (french: rocher du Diamant) is a 175-metre-high (574 ft) Maurice volunteered to lead a party of men to prepare the fortifications.

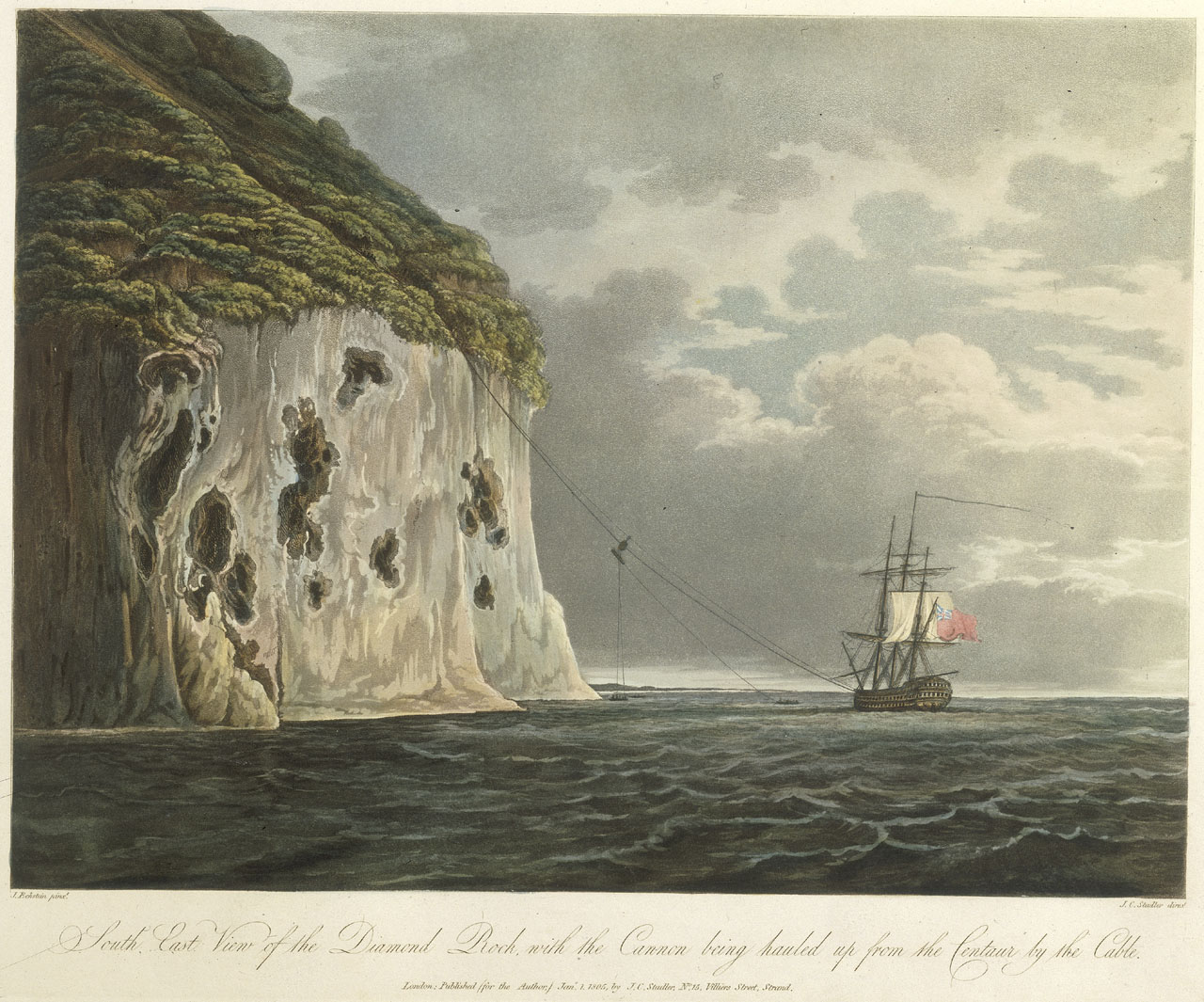

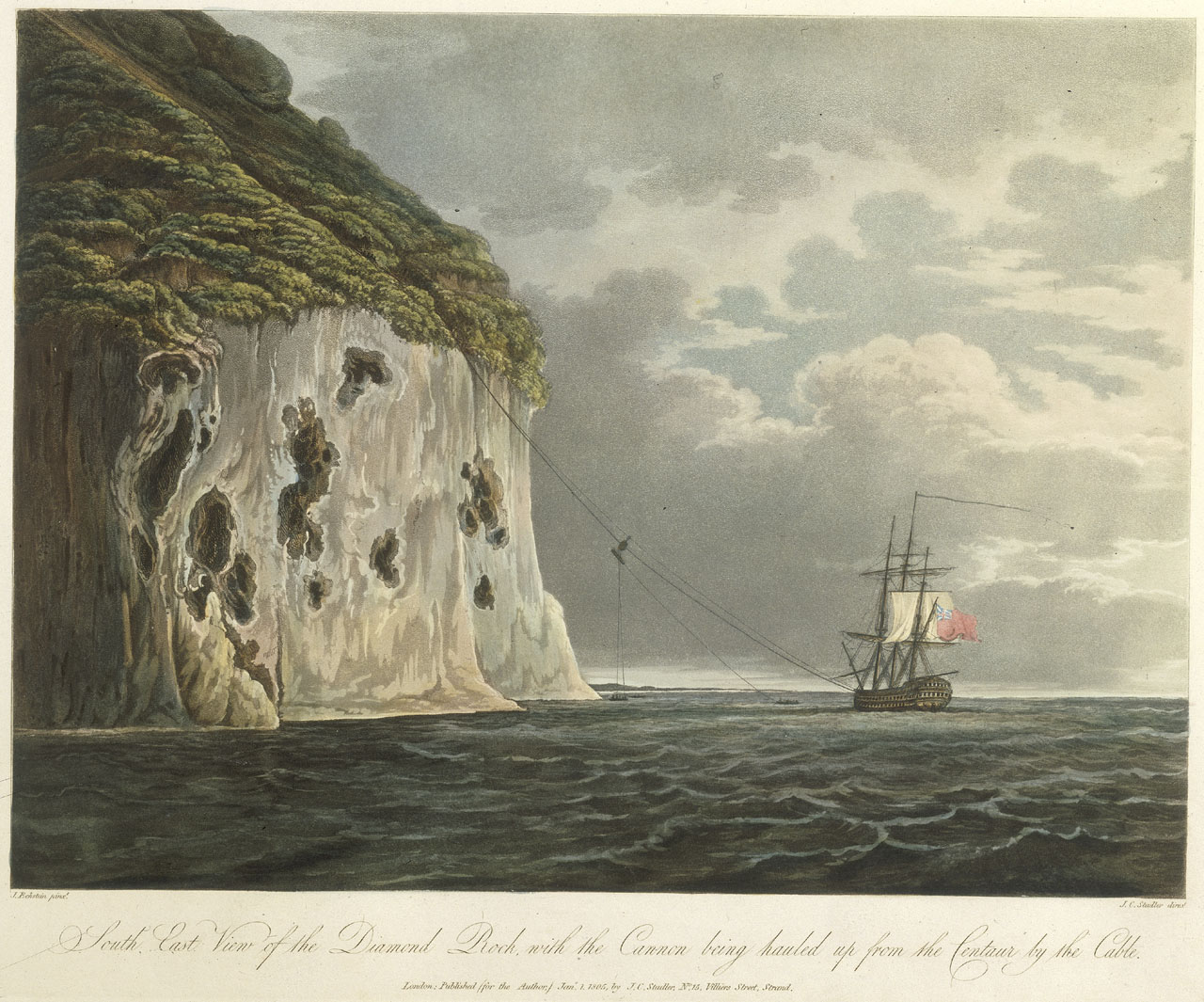

Maurice led a party of men onto the rock on 7 January 1804, and work immediately began on fortifying the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and establishing forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery.

In February a number of guns were transferred over from ''Centaur'', with two 24-pounders being installed in separate batteries at sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder

Maurice led a party of men onto the rock on 7 January 1804, and work immediately began on fortifying the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and establishing forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery.

In February a number of guns were transferred over from ''Centaur'', with two 24-pounders being installed in separate batteries at sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder

For seventeen months Maurice held the rock, foiling several attempts by the French at Martinique to oust them. He reported the movements of Rear-Admiral Missiessy's fleet which arrived in the area during the Trafalgar Campaign, but in May 1805 a fleet under Pierre de Villeneuve arrived in Fort de France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. Shortly after their arrival Maurice discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

For seventeen months Maurice held the rock, foiling several attempts by the French at Martinique to oust them. He reported the movements of Rear-Admiral Missiessy's fleet which arrived in the area during the Trafalgar Campaign, but in May 1805 a fleet under Pierre de Villeneuve arrived in Fort de France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. Shortly after their arrival Maurice discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

Fortifying the rock

Maurice led a party of men onto the rock on 7 January 1804, and work immediately began on fortifying the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and establishing forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery.

In February a number of guns were transferred over from ''Centaur'', with two 24-pounders being installed in separate batteries at sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder

Maurice led a party of men onto the rock on 7 January 1804, and work immediately began on fortifying the small cove they had landed at with their launch's 24-pounder, and establishing forges and artificers' workshops in a cave at the base of the rock. After fixing ladders and ropes to scale the sheer sides of the rock, they were able to access the summit and began to establish messes and sleeping areas in a number of small caves. Bats were driven out by burning bales of hay, and a space was cleared by blasting at the top of the rock in order to establish a battery.

In February a number of guns were transferred over from ''Centaur'', with two 24-pounders being installed in separate batteries at sea level, another 24-pounder halfway up the rock, and two 18-pounders in the battery at the top. In addition to this the men had use of a number of boats, with one armed with a 24-pounder carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century. Its main func ...

, which were used to intercept enemy ships. Marshall's ''Naval Biography'', when describing the process of hauling the guns to the summit, recorded that

Commander Maurice, of Diamond Rock

By early February the guns had been installed and tested. The 18-pounders were able to command completely the passage between the rock and the island, forcing ships to avoid the channel. The winds and currents meant that these ships were then unable to enter the bay. With work complete by 7 February Hood decided to formalise the administration of the island, and wrote to theAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, announcing that he had commissioned the rock as a sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

, under the name ''Fort Diamond''. Lieutenant Maurice, who had impressed Hood with his efforts while establishing the position, was rewarded by being made commander. Diamond Rock was to be considered a captured enemy ship, and was technically treated as a tender to one of the boats stationed there, commissioned by the Admiralty as the sloop ''Diamond Rock'', superseding Hood's use of ''Fort Diamond''.

Maurice had a party of around 100 men under his command on the rock, with the usual officers found on a British warship, including a surgeon, purser, and a junior lieutenant to command the small supply vessel. A hospital was established, and food, gunpowder and ammunition were brought to the rock in boats, at first from ''Centaur'', and then from Martinique, where it was purchased from sympathetic inhabitants. Water also had to be brought from the island, and large cisterns were built to store it.

For seventeen months Maurice held the rock, foiling several attempts by the French at Martinique to oust them. He reported the movements of Rear-Admiral Missiessy's fleet which arrived in the area during the Trafalgar Campaign, but in May 1805 a fleet under Pierre de Villeneuve arrived in Fort de France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. Shortly after their arrival Maurice discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

For seventeen months Maurice held the rock, foiling several attempts by the French at Martinique to oust them. He reported the movements of Rear-Admiral Missiessy's fleet which arrived in the area during the Trafalgar Campaign, but in May 1805 a fleet under Pierre de Villeneuve arrived in Fort de France Bay, having briefly exchanged fire with the British on Diamond Rock as they did so. Shortly after their arrival Maurice discovered that the main cistern, holding a month's supply of water, had cracked in some earth tremors, and the leak had been made worse by the vibration from the guns. There was barely two weeks left, but fresh supplies were now unobtainable as a blockade of the rock began by a number of schooners, brigs and frigates.

The fight for Diamond Rock

Villeneuve despatched a flotilla consisting of the 74-gun ''Pluton'' and ''Berwick'', the 36-gun ''Sirène'', acorvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

, schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

, eleven gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s, and between three and four hundred men, under Captain Julien Cosmao

Julien Marie Cosmao-Kerjulien (Châteaulin, Finistère, 27 November 1761 – Brest, 17 February 1825) was a French Navy officer, admiral, best remembered for his role in the Battle of Trafalgar.

Career

Early career

Completing his stud ...

, to retake the rock. A French force landed unopposed on 31 May, Maurice having assessed the overwhelming strength of the French, and having decided that it would be impossible to hold the lower stages withdrew his forces to defend the upper levels. Cosmao began an intense bombardment while the infantry forced their way onto the landing stage, losing three gunboats and two rowing boats full of soldiers as they did so. The attacking force had however neglected to bring any scaling ladders, and could not assault the sheer rock sides. Instead they were forced to besiege the British forces in the upper levels. By 2 June, with his ammunition almost exhausted and water supplies running critically short, Maurice opened negotiations.

At five o'clock Maurice agreed to surrender Diamond Rock. The British had two men killed and one man wounded in the battle. French casualties were harder to judge, Maurice estimated they amounted to seventy, the French commander of the landing force made a 'hasty calculation' of fifty. Maurice and his men were taken off the rock on the morning of 6 June and put on board the ''Pluton'' and ''Berwick''.

They were returned to Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

by 6 June. As Diamond Rock was legally considered a Royal Navy vessel, and the commander was legally "captain" of it, he was tried by court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

on 28 June (as the law dictated in any case where a captain loses his ship, regardless of the cause) for its loss. The court unanimously acquitted him, noting

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

, who had arrived in the West Indies in pursuit of Villeneuve's fleet, apologised to Maurice for having arrived too late to prevent the fall of Diamond Rock. Maurice returned to England in August and Nelson arranged for him to take command of the 18-gun brig-sloop

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

on 20 August. Maurice was to join Nelson off Cadiz, but she could not be manned in time, and Maurice missed reuniting with Nelson prior to Nelson's death at Trafalgar Trafalgar most often refers to:

* Battle of Trafalgar (1805), fought near Cape Trafalgar, Spain

* Trafalgar Square, a public space and tourist attraction in London, England

It may also refer to:

Music

* ''Trafalgar'' (album), by the Bee Gees

Pl ...

.

After two years in the Channel, Maurice and ''Savage'' sailed to the West Indies. While in command of ''Savage'', in early December 1807 Maurice captured the Spanish privateer ''Quixote'' of Port Cavallo. ''Quixote'' was armed with eight guns and had a crew of 99 men. She was a "Vessel of a large Class, and fitted out for the Annoyance of the Trade to amaica.

Command in the West Indies

Maurice again returned to the West Indies in July 1808, joining the fleet at Barbados underSir Alexander Cochrane

Admiral of the Blue Sir Alexander Inglis Cochrane (born Alexander Forrester Cochrane; 23 April 1758 – 26 January 1832) was a senior Royal Navy commander during the Napoleonic Wars and achieved the rank of admiral.

He had previously captai ...

. He carried with him a letter of recommendation from the Admiralty, and Cochrane appointed him governor of Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

, a commission confirmed by the Admiralty on 18 January 1809 with a promotion to post-captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of Captain (Royal Navy), captain in the Royal Navy.

The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:

* Officers in command of a naval vessel, who were (and still are) ...

. Marie-Galante had not been long in British possession, and there was the risk of an uprising. Maurice had only 400 soldiers under his command, many of whom were seriously ill. A regiment was raised from the black population, but its loyalty was suspect. The issue became moot as the French never attacked the island. When Maurice became ill he resigned his commission to return to Britain.

Governor of Anholt

Maurice was made Governor of Anholt in August 1810, a Danish island in theKattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

captured in May the previous year during the Gunboat War

The Gunboat War (, ; 1807–1814) was a naval conflict between Denmark–Norway and the British during the Napoleonic Wars. The war's name is derived from the Danish tactic of employing small gunboats against the materially superior Royal Nav ...

. He had a force of 400 marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

under his command, while British frigates patrolled the approaches to the island. These patrols prevented any Danish attack, except possible for a few weeks during the beginning and end of the winter freeze, when the supporting ships would be off station. It was expected that the Danes or French would attempt to recapture it, and Maurice was forewarned of a Danish attack that began on 27 March 1811. Maurice recorded that the enemy force attacked the British in their well prepared positions, but were driven off after four and a half hours of fighting. The ''Naval Chronicle'' recorded

Though this account was probably exaggerated, the battle remained a crushing defeat for the Danes, who were unaware of the presence of the two frigates, and , when they made their attack. Maurice was presented with a sword by the garrison, and continued at Anholt until September 1812.

Later years

Maurice then returned to Britain and saw no more active service. He married Sarah Lyne of Plymouth on 5 October 1814, but she died oftyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

in June the following year at the age of 21. Maurice never remarried. He was promoted to rear-admiral on the retired list on 1 October 1846, and to vice-admiral on 28 May 1853. He died at East Emma Place, East Stonehouse

East Stonehouse was one of three towns that were amalgamated into modern-day Plymouth. West Stonehouse was a village that is within the current Mount Edgcumbe Country Park in Cornwall. It was destroyed by the French in 1350.

The terminology use ...

, Plymouth, on 4 September 1857 at the age of 82.

Notes

References

* * ** * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Maurice, James Wilkes 1775 births 1857 deaths Royal Navy vice admirals Royal Navy personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars Royal Navy personnel of the Napoleonic Wars Royal Navy officers who were court-martialled