Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

as an organized movement is generally considered to have been founded by

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

in 1897. However, the history of Zionism began earlier and is related to

Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

and

Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, and their nation, religion, and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions, and cultures. Although Judaism as a religion first appears in Greek records during the Hellenisti ...

. The

Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion ( he, חובבי ציון, lit. ''hose who areLovers of Zion''), also known as Hibbat Zion ( he, חיבת ציון), refers to a variety of organizations which were founded in 1881 in response to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian ...

, or the ''Lovers of Zion'', were responsible for the creation of 20 new Jewish towns in Palestine between 1870 and 1897.

The movement's central aim was the re-establishment of a

Jewish national home

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction o ...

and cultural centre in Palestine by facilitating

Jewish return from diaspora, as well as the re-establishment of a

Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland of the Jewish people.

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewish people. ...

(usually defined as a secular state with a Jewish majority), attaining its goal in 1948 with the creation of

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

Since the creation of Israel, the importance of the Zionist movement as an organization has declined, as the Israeli state has grown stronger.

The Zionist movement continues to exist, working to support Israel, assist

persecuted Jews and encourage Jewish

emigration to Israel. Most

Israeli political parties continue to define themselves as Zionist.

The success of Zionism has meant that the percentage of the world's

Jewish population

As of 2020, the world's "core" Jewish population (those identifying as Jews above all else) was estimated at 15 million, 0.2% of the 8 billion worldwide population. This number rises to 18 million with the addition of the "connected" Jewish pop ...

who live in Israel has steadily grown over the years and today 40% of the world's Jews live in Israel. There is no other example in human history of a

nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

being reestablished after such a long period of existence as a

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

.

Background: The historic and religious origins of Zionism

Biblical precedents

The precedence for Jews to return to their ancestral homeland, motivated by strong divine intervention, first appears in the

Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

, and thus later adopted in the

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

. After

Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

and his sons had gone down to Egypt to escape a drought, they were enslaved and became a nation. Later, as commanded by God,

Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

went before Pharaoh, demanded, "Let my people go!" and foretold

severe consequences, if this was not done. Torah describes the story of the plagues and the

Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

from Egypt, which is estimated at about 1400 BCE, and the beginning of the journey of the Jewish People toward the Land of Israel. These are celebrated annually during

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

, and the Passover meal traditionally ends with the words "

Next Year in Jerusalem

''L'Shana Haba'ah B'Yerushalayim'' ( he, לשנה הבאה בירושלים), lit. "Next year in Jerusalem", is a phrase that is often sung at the end of the Passover Seder_and_at_the_end_of_the_'' isan_in_the__Hebrew_..._and_at_the_end_of_the_' ...

."

The theme of return to their traditional homeland came up again after the

Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

ians conquered Judea in 587 BCE and the Judeans were exiled to Babylon. In the book of

Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

(

Psalm 137

Psalm 137 is the 137th psalm of the Book of Psalms in the Tanakh. In English it is generally known as "By the rivers of Babylon", which is how its first words are translated in the King James Version of the Bible. Its Latin title is "Super flum ...

), Jews lamented their exile while Prophets like

Ezekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

foresaw their return. The Bible recounts how, in 538 BCE

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

of

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

conquered Babylon and issued a proclamation granting the people of Judah their freedom. 50,000 Judeans, led by

Zerubbabel

According to the biblical narrative, Zerubbabel, ; la, Zorobabel; Akkadian: 𒆰𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠 ''Zērubābili'' was a governor of the Achaemenid Empire's province Yehud Medinata and the grandson of Jeconiah, penultimate king of Judah. Zerubbab ...

returned. A second group of 5000, led by

Ezra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρας ...

and

Nehemiah

Nehemiah is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period. He was governor of Persian Judea under Artaxerxes I of Persia (465–424 BC). The name is pronounced ...

, returned to

Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous L ...

in 456 BCE.

Precursors

The 613

Jewish revolt against Heraclius

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

is considered the last serious Jewish attempt for gaining autonomy in Palestine in antiquity. In 1160

David Alroy

David Alroy or Alrui ( ar, داود ابن الروحي, , fl. 1160), also known as Ibn ar-Ruhi and David El-David, was a Jewish Messiah claimant born in Amadiya, Iraq under the name Menaḥem ben Solomon (). David Alroy studied Torah and Talmud ...

led a Jewish uprising in

Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, ...

that aimed to reconquer the promised land. In 1648

Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi (; August 1, 1626 – c. September 17, 1676), also spelled Shabbetai Ẓevi, Shabbeṯāy Ṣeḇī, Shabsai Tzvi, Sabbatai Zvi, and ''Sabetay Sevi'' in Turkish, was a Jewish mystic and ordained rabbi from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turk ...

from modern Turkey claimed he would lead the Jews back to Palestine. At the beginning of the 19th century, the

Perushim

The ''perushim'' ( he, פרושים) were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria under Ottoman ...

, disciples of the

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

, left

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

to settle in the

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

in anticipation of the return of the Messiah in 1840. A dispatch from the British Consulate in Jerusalem in 1839 reported that "the Jews of Algiers and its dependencies, are numerous in Palestine..." There was also significant migration from Central Asia (

Bukharan Jews

Bukharan Jews ( Bukharian: יהודיאני בוכארא/яҳудиёни Бухоро, ''Yahudiyoni Bukhoro''; he, יהודי בוכרה, ''Yehudey Bukhara''), in modern times also called Bukharian Jews ( Bukharian: יהודיאני בוכאר ...

). In 1868

Judah ben Shalom

Judah ben Shalom (died ca. 1878) (Hebrew: יהודה בן שלום), also known as Mori (Master) Shooker Kohail II or Shukr Kuhayl II (Hebrew: מרי שכר כחיל), was a Yemenite messianic claimant of the mid-19th century.

The rise of Shuk ...

led a large movement of

Yemenite Jews

Yemenite Jews or Yemeni Jews or Teimanim (from ''Yehudei Teman''; ar, اليهود اليمنيون) are those Jews who live, or once lived, in Yemen, and their descendants maintaining their customs. Between June 1949 and September 1950, the ...

to Palestine.

In addition to Messianic movements, the population of the Holy Land was slowly bolstered by Jews fleeing

Christian persecution, especially after the so-called ''

Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

'' of ''

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

'' (the Arabic name for the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

).

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

became an important center of

Kabbalah

Kabbalah ( he, קַבָּלָה ''Qabbālā'', literally "reception, tradition") is an esoteric method, discipline and Jewish theology, school of thought in Jewish mysticism. A traditional Kabbalist is called a Mekubbal ( ''Məqūbbāl'' "rece ...

.

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

,

Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

, and

Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Fo ...

also had significant Jewish populations.

Aliyah and the ingathering of the exiles

Among

Jews in the Diaspora,

Eretz Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

was revered in a cultural, national, ethnic, historical, and religious sense. They thought of a return to it in a future messianic age. Return remained a recurring theme among generations, particularly in

Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (; ), is a major Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday that celebrates the The Exodus, Biblical story of the Israelites escape from slavery in Ancient Egypt, Egypt, which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew calendar, He ...

and

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur (; he, יוֹם כִּפּוּר, , , ) is the holiest day in Judaism and Samaritanism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the first month of the Hebrew calendar. Primarily centered on atonement and repentance, the day's ...

prayers, which traditionally concluded with "

Next year in Jerusalem

''L'Shana Haba'ah B'Yerushalayim'' ( he, לשנה הבאה בירושלים), lit. "Next year in Jerusalem", is a phrase that is often sung at the end of the Passover Seder_and_at_the_end_of_the_'' isan_in_the__Hebrew_..._and_at_the_end_of_the_' ...

", and in the thrice-daily

Amidah

The ''Amidah Amuhduh'' ( he, תפילת העמידה, ''Tefilat HaAmidah'', 'The Standing Prayer'), also called the ''Shemoneh Esreh'' ( 'eighteen'), is the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. Observant Jews recite the ''Amidah'' at each o ...

(Standing prayer).

Jewish daily prayers include many references to "your people Israel", "your return to Jerusalem" and associate salvation with a restored presence in the Land of Israel, the Land of Zion and Jerusalem (usually accompanied by a Messiah); for example the prayer

Uva Letzion (Isaiah 59:20): "And a redeemer shall come to Zion..." ''Aliyah'' (return to Israel) has always been considered a praiseworthy act for Jews according to

Jewish law

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws which is derived from the Torah, written and Oral Tora ...

and some Rabbis consider it one of the core

613 commandments in Judaism. From the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and onwards, some famous rabbis (and often their followers) made aliyah to the Land of Israel. These included

Nahmanides

Moses ben Nachman ( he, מֹשֶׁה בֶּן־נָחְמָן ''Mōše ben-Nāḥmān'', "Moses son of Nachman"; 1194–1270), commonly known as Nachmanides (; el, Ναχμανίδης ''Nakhmanídēs''), and also referred to by the acronym Ra ...

,

Yechiel of Paris

Yechiel ben Joseph of Paris or Jehiel of Paris, called Sire Vives in French (Judeo-French: ) and Vivus Meldensis ("Vives of Meaux") in Latin, was a major Talmudic scholar and Tosafist from northern France, father-in-law of Isaac ben Joseph of Cor ...

with several hundred of his students,

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo

Joseph ben Ephraim Karo, also spelled Yosef Caro, or Qaro ( he, יוסף קארו; 1488 – March 24, 1575, 13 Nisan 5335 A.M.), was the author of the last great codification of Jewish law, the '' Beit Yosef'', and its popular analogue, the ''Shu ...

,

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (1730?–1788), also known as Menachem Mendel of Horodok, was an early leader of Hasidic Judaism. Part of the third generation of Hassidic leaders, he was the primary disciple of the Maggid of Mezeritch. From his base i ...

and 300 of his followers, and over 500 disciples (and their families) of the

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

known as

Perushim

The ''perushim'' ( he, פרושים) were Jewish disciples of the Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, who left Lithuania at the beginning of the 19th century to settle in the Land of Israel, which was then part of Ottoman Syria under Ottoman ...

, among others.

Persecution of the Jews

Persecution of Jews played a key role in preserving Jewish identity and keeping Jewish communities transient, it would later provide a key role in inspiring Zionists to reject European forms of identity.

Jews in Catholic states were banned from owning land and from pursuing a variety of professions. From the 13th century Jews were required to wear identifying clothes such as

special hats or

stars on their clothing. This form of persecution originated in tenth century Baghdad and was copied by Christian rulers. Constant expulsions and insecurity led Jews to adopt artisan professions that were easily transferable between locations (such as furniture making or tailoring).

Persecution in Spain and Portugal led large number of Jews there to convert to Christianity, however many continued to

secretly practice Jewish rituals. The Church responded by creating the

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

in 1478 and by expelling all remaining

Jews in 1492. In 1542 the inquisition expanded to include the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

. Inquisitors could arbitrarily torture suspects and many victims were burnt alive.

In 1516 the Republic of Venice decreed that Jews would only be allowed to reside in a walled-in area of town called the

ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

. Ghetto residents had to pay a daily

poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

and could only stay a limited amount of time. In 1555 the Pope decreed that Jews in Rome were to face similar restrictions. The requirement for Jews to live in Ghettos spread across Europe and Ghettos were frequently highly overcrowded and heavily taxed. They also provided a convenient target for mobs (

pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

). Jews were

expelled from England in 1290. A ban remained in force that was only lifted when

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

overthrew the monarchy in 1649 (see

Resettlement of the Jews in England

The resettlement of the Jews in England was an informal arrangement during the Commonwealth of England in the mid-1650s, which allowed Jews to practise their faith openly. It forms a prominent part of the history of the Jews in England. It h ...

).

Persecution of Jews began to decline following

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's conquest of Europe after the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

although the short lived Nazi Empire resurrected most practices.

In 1965 the Catholic Church

formally excluded the idea of holding Jews collectively responsible for the death of Jesus.

Pre-Zionist Initiatives 1799–1897

The Enlightenment and the Jews

The

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in Europe led to an 18th- and 19th-century Jewish enlightenment movement in Europe, called the

Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

. In 1791, the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

led France to become the first country in Europe to grant Jews legal equality. Britain gave Jews equal rights in 1856, Germany in 1871. The spread of western liberal ideas among newly emancipated Jews created for the first time a class of

secular Jews who absorbed the prevailing ideas of enlightenment, including

rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

,

romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, and

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

.

However, the formation of modern nations in Europe accompanied changes in the prejudices against Jews. What had previously been

religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within soc ...

now became a new phenomenon of

racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from ...

and acquired a new name:

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Antisemites saw Jews as an alien religious, national and racial group and actively tried to prevent Jews from acquiring equal rights and citizenship. The Catholic press was at the forefront of these efforts and was quietly encouraged by the Vatican, which saw its own decline in status as linked to the equality granted to Jews. By the late 19th century, the more extreme nationalist movements in Europe often promoted physical violence against Jews who they regarded as interlopers and exploiters threatening the well-being of their nations.

Persecution in the Russian Empire

Jews in Eastern Europe faced constant

pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s and

persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

in Tsarist Russia. From 1791 they were only allowed to live in the

Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

. In response to the Jewish drive for integration and modern education (

Haskalah

The ''Haskalah'', often termed Jewish Enlightenment ( he, השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with a certain influence on those in Western Euro ...

) and the movement for emancipation, the Tsars imposed

tight quotas on schools, universities and cities to prevent entry by Jews. From 1827 to 1917 Russian Jewish boys were required to serve 25 years in the Russian army, starting at the age of 12. The intention was to forcibly destroy their ethnic identity, however the move severely radicalized Russia's Jews and familiarized them with nationalism and socialism.

The tsar's chief adviser

Konstantin Pobedonostsev

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev ( rus, Константи́н Петро́вич Победоно́сцев, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin pʲɪˈtrovʲɪtɕ pəbʲɪdɐˈnostsɨf; 30 November 1827 – 23 March 1907) was a Russian jurist, statesman, ...

, was reported as saying that one-third of Russia's Jews was expected to emigrate, one-third to accept baptism, and one-third to starve.

Famous incidents includes the 1913

Menahem Mendel Beilis

Menahem Mendel Beilis (sometimes spelled Beiliss; yi, מנחם מענדל בייליס, russian: Менахем Мендель Бейлис; 1874 – 7 July 1934) was a Russian Jew accused of ritual murder in Kiev in the Russian Empire in a no ...

trial (

Blood libel against Jews

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

) and the 1903

Kishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octobe ...

.

Between 1880 and 1928, two million Jews left Russia; most emigrated to the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, a minority chose Palestine.

Proto-Zionism

Proto-Zionists include the (Lithuanian)

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

, (Russian) Rabbi

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk

Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (1730?–1788), also known as Menachem Mendel of Horodok, was an early leader of Hasidic Judaism. Part of the third generation of Hassidic leaders, he was the primary disciple of the Maggid of Mezeritch. From his base i ...

, (Bosnian) Rabbi

Judah Alkalai

Judah ben Solomon Chai Alkalai (1798 – October 1878) was a Sephardic Jewish rabbi, and one of the influential precursors of modern Zionism along with the Prussian Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer. Although he was a Sephardic Jew, he played an import ...

(German) Rabbi

Zvi Hirsch Kalischer

Zvi (Zwi) Hirsch Kalischer (24 March 1795 – 16 October 1874) was an Orthodox German rabbi who expressed views, from a religious perspective, in favour of the Jewish re-settlement of the Land of Israel, which predate Theodor Herzl and the Zionist ...

, and (British) Sir

Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, afte ...

. Other advocates of Jewish independence include (American)

Mordecai Manuel Noah

Mordecai Manuel Noah (July 14, 1785, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – May 22, 1851, New York City, New York) was an American sheriff, playwright, diplomat, journalist, and utopian. He was born in a family of Portuguese people, Portuguese Sephardic ...

, (Russian)

Leon Pinsker

yi, לעאָן פינסקער

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Tomaszów Lubelski, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = Odessa, Russian Empire

, known_for = Zionism

, occupation = Physician, political activ ...

and (German)

Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zion ...

.

The

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

of Lithuania (1720-1797) promoted a teaching from the Zohar (book of Jewish mysticism) that “the gates of wisdom above and the founts of wisdom below will open” would happen after the start of the 6th century of the 6th millennium i.e. after the year 5600 of the Jewish calendar (1839-1840 AD). Many understood this to imply the coming of the Messiah at that time, and thus an early wave of Jewish migration to the Holy Land began in 1808 and grew until the 1840s.

In 1862

Moses Hess

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His socialist theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zion ...

, a former associate of Karl Marx and Frederich Engels, wrote ''

Rome and Jerusalem. The Last National Question'' calling for the Jews to create a socialist state in

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

as a means of settling the

Jewish question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

. Also in 1862, German Orthodox Rabbi Kalischer published his tractate ''Derishat Zion'', arguing that the salvation of the Jews, promised by the Prophets, can come about only by self-help. In 1882, after the

Odessa pogrom

A series of pogroms against Jews in the city of Odessa, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, took place during the 19th and early 20th centuries. They occurred in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881 and 1905.

According to Jarrod Tanny, most historians in ...

,

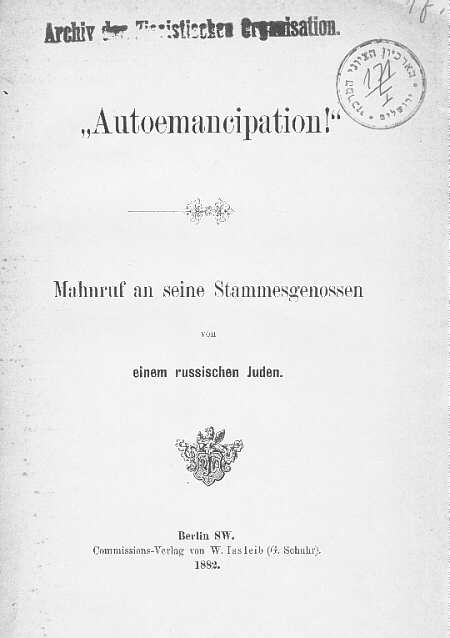

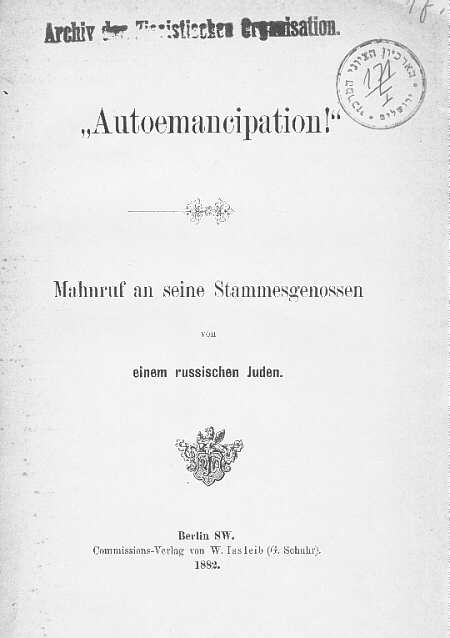

Judah Leib Pinsker published the pamphlet ''

Auto-Emancipation

upThe book "Auto-Emancipation" by Pinsker, 1882

''Auto-Emancipation'' (''Selbstemanzipation'') is a pamphlet written in German by Russian-Polish Jewish doctor and activist Leo Pinsker in 1882. It is considered a founding document of modern Jewis ...

'' (self-emancipation), arguing that Jews could only be truly free in their own country and analyzing the persistent tendency of Europeans to regard Jews as aliens:

"Since the Jew is nowhere at home, nowhere regarded as a native, he remains an alien everywhere. That he himself and his ancestors as well are born in the country does not alter this fact in the least... to the living the Jew is a corpse, to the native a foreigner, to the homesteader a vagrant, to the proprietary a beggar, to the poor an exploiter and a millionaire, to the patriot a man without a country, for all a hated rival."

Pinsker established the

Hibbat Zion movement to actively promote Jewish settlement in Palestine. In 1890, the "Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz Israel" (better known as the

Odessa Committee The Odessa Committee, officially known as the Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Palestine, was a Charitable organization, charitable, pre-Zionism, Zionist organization in the Russian Empire, which supported aliyah, ...

) was officially registered as a

charitable organization

A charitable organization or charity is an organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being (e.g. educational, Religion, religious or other activities serving the public interest or common good).

The legal definitio ...

in the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and by 1897, it counted over 4,000 members.

Early British and American support for Jewish return

Ideas of the restoration of the Jews in the Land of Israel entered

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

public discourse in the early 19th century, at about the same time as the British Protestant Revival.

[British Zionism - Support for Jewish Restoration]

(mideastweb.org)

Not all such attitudes were favorable towards the Jews; they were shaped in part by a variety of

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

beliefs,

[The Untold Story. The Role of Christian Zionists in the Establishment of Modern-day Israel]

by Jamie Cowen (Leadership U), July 13, 2002 or by a streak of

philo-Semitism

Philosemitism is a notable interest in, respect for, and appreciation of the Jewish people, their history, and the influence of Judaism, particularly on the part of a non-Jew. In the aftermath of World War II, the phenomenon of philosemitism saw ...

among the classically educated British elite,

[Rethinking Sir Moses Montefiore: Religion, Nationhood, and International Philanthropy in the Nineteenth Century]

by Abigail Green. (''The American Historical Review''. Vol. 110 No.3.) June 2005 or by hopes to extend the Empire. ''(See

The Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

)''

At the urging of

Lord Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his f ...

, Britain established a consulate in Jerusalem in 1838, the first diplomatic appointment in the city. In 1839, the

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

sent

Andrew Bonar

Andrew Alexander Bonar (29 May 1810 in Edinburgh – 30 December 1892 in Glasgow) was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900), Free Church of Scotland, a contemporary and acquaintance of Robert Murray M'Cheyne and youngest brother ...

and

Robert Murray M'Cheyne

Robert Murray M'Cheyne (21 May 1813 – 25 March 1843) was a minister in the Church of Scotland from 1835 to 1843. He was born at Edinburgh on 21 May 1813, was educated at the university and at the Divinity Hall of his native city, and was ...

to report on the condition of the Jews there. The report was widely published and was followed by ''Memorandum to Protestant Monarchs of Europe for the restoration of the Jews to Palestine''. In August 1840, ''The Times'' reported that the British government was considering Jewish restoration.

[ Correspondence in 1841–42 between ]Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, afte ...

, the President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews

The Board of Deputies of British Jews, commonly referred to as the Board of Deputies, is the largest and second oldest Jewish communal organisation in the United Kingdom, after only the Initiation Society which was founded in 1745. Established ...

and Charles Henry Churchill

Colonel Charles Henry Churchill (1807–1869), also known as "Churchill Bey", was a British army officer and diplomat. He was a British consul in Ottoman Syria, and proposed one of the first political plans for Zionism and the creation of an Is ...

, the British consul in Damascus, is seen as the first recorded plan proposed for political Zionism.[''Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish Question with texts of protocols, treaty stipulations and other public acts and official documents'', Lucien Wolf, published by the Jewish Historical Society of England, 191]

/ref>

Lord Lindsay wrote in 1847: "The soil of Palestine still enjoys her sabbaths, and only waits for the return of her banished children, and the application of industry, commensurate with her agricultural capabilities, to burst once more into universal luxuriance, and be all that she ever was in the days of Solomon."

In 1851, correspondence between Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby, Lord Stanley, whose father became British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

the following year, and Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

alongside him, records Disraeli's proto-Zionist views: "He then unfolded a plan of restoring the nation to Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

—said the country was admirably suited for them—the financiers all over Europe might help—the Porte

Porte may refer to:

*Sublime Porte, the central government of the Ottoman empire

*Porte, Piedmont, a municipality in the Piedmont region of Italy

*John Cyril Porte, British/Irish aviator

*Richie Porte, Australian professional cyclist who competes ...

is weak—the Turks/holders of property could be bought out—this, he said, was the object of his life..." ''Coningsby

Coningsby is a village and civil parish in the East Lindsey district in Lincolnshire, England, it is situated on the A153 road, adjoining Tattershall on its western side, 13 miles (22 km) north west of Boston and 8 miles (13 km) so ...

'' was merely a feelermy views were not fully developed at that time—since then all I have written has been for one purpose. The man who should restore the Hebrew race to their country would be the Messiah—the real saviour of prophecy!" He did not add formally that he aspired to play this part, but it was evidently implied. He thought very highly of the capabilities of the country, and hinted that his chief object in acquiring power here would be to promote the return". 26 years later, Disraeli wrote in his article entitled "The Jewish Question is the Oriental Quest" (1877) that within fifty years, a nation of one million Jews would reside in Palestine under the guidance of the British.

Sir Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, philanthropist and Sheriff of London. Born to an Italian Sephardic Jewish family based in London, afte ...

visited the Land of Israel seven times and fostered its development.[

In 1842, ]Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

, founder of the Latter Day Saints movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

, sent a representative, Orson Hyde

Orson Hyde (January 8, 1805 – November 28, 1878) was a leader in the early Latter Day Saint movement and a member of the first Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus ...

, to dedicate the land of Israel for the return of the Jews. Protestant theologian William Eugene Blackstone

William Eugene Blackstone (October 6, 1841 – November 7, 1935) was an American evangelist and Christian Zionist. He was the author of the Blackstone Memorial of 1891, a petition which called upon America to actively return the Holy Land to th ...

submitted a petition to the US president in 1891; the Blackstone Memorial The Blackstone Memorial of 1891 was a petition written by William Eugene Blackstone, a Christian Restorationist, in favor of the delivery of Palestine to the Jews. It was signed by many leading American citizens and presented to President Benjami ...

called for the return of Palestine to the Jews.

The first aliya

In the late 1870s, Jewish philanthropists such as the Montefiores and the Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

s responded to the persecution of Jews in Eastern Europe by sponsoring agricultural settlements for Russian Jews in Palestine. The Jews who migrated in this period are known as the First Aliyah

The First Aliyah (Hebrew: העלייה הראשונה, ''HaAliyah HaRishona''), also known as the agriculture Aliyah, was a major wave of Jewish immigration ('' aliyah'') to Ottoman Syria between 1881 and 1903. Jews who migrated in this wave ca ...

. ''Aliyah'' is a Hebrew word meaning "ascent", referring to the act of spiritually "ascending" to the Holy Land and a basic tenet of Zionism.

The movement of Jews to Palestine was opposed by the Haredi

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

communities who lived in the Four Holy Cities

The Four Holy Cities of Judaism are the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias which were the four main centers of Jewish life after the Ottoman conquest of Palestine.

According to the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: "Since the sixteenth cen ...

, since they were very poor and lived off charitable donations from Europe, which they feared would be used by the newcomers. However, from 1800 there was a movement of Sephardi businessmen from North Africa and the Balkans to Jaffa and the growing community there perceived modernity and Aliyah as the key to salvation. Unlike the Haredi communities, the Jaffa community did not maintain separate Ashkenazi and Sephardi institutions and functioned as a single unified community.

Founded in 1878, Rosh Pinna

Rosh Pina or Rosh Pinna ( he, רֹאשׁ פִּנָּה, lit. ''Cornerstone'') is a local council in the Korazim Plateau in the Upper Galilee on the eastern slopes of Mount Kna'an in the Northern District of Israel. It was established as Gei ...

and Petah Tikva

Petah Tikva ( he, פֶּתַח תִּקְוָה, , ), also known as ''Em HaMoshavot'' (), is a city in the Central District (Israel), Central District of Israel, east of Tel Aviv. It was founded in 1878, mainly by Haredi Judaism, Haredi Jews of ...

were the first modern Jewish settlements.

In 1881–1882 the Tsar sponsored a huge wave of pogroms in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and a massive wave of Jews began leaving, mainly for America. So many Russian Jews arrived in Jaffa that the town ran out of accommodation and the local Jews began forming communities outside the Jaffa city walls. However, the migrants faced difficulty finding work (the new settlements mainly needed farmers and builders) and 70% ultimately left, mostly moving on to America. One of the migrants in this period, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda

Eliezer Ben‑Yehuda ( he, אֱלִיעֶזֶר בֵּן־יְהוּדָה}; ; born Eliezer Yitzhak Perlman, 7 January 1858 – 16 December 1922) was a Russian–Jewish linguist, grammarian, and journalist, renowned as the lexicographer of ...

set about modernizing Hebrew so that it could be used as a national language.

Rishon LeZion

Rishon LeZion ( he, רִאשׁוֹן לְצִיּוֹן , ''lit.'' First to Zion, Arabic: راشون لتسيون) is a city in Israel, located along the central Israeli coastal plain south of Tel Aviv. It is part of the Gush Dan metropolitan ar ...

was founded on 31 July 1882 by a group of ten members of Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion ( he, חובבי ציון, lit. ''hose who areLovers of Zion''), also known as Hibbat Zion ( he, חיבת ציון), refers to a variety of organizations which were founded in 1881 in response to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian ...

from Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine. (today's Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

). Zikhron Ya'akov was founded in December 1882 by Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion ( he, חובבי ציון, lit. ''hose who areLovers of Zion''), also known as Hibbat Zion ( he, חיבת ציון), refers to a variety of organizations which were founded in 1881 in response to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian ...

pioneers from Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

. In 1887 Neve Tzedek

Neve Tzedek ( he, נְוֵה צֶדֶק, נווה צדק, ''lit.'' Abode of Justice) is a neighborhood located in southwestern Tel Aviv, Israel. It was the first Judaism, Jewish neighborhood to be built outside the old city of the ancient port of ...

was built just outside Jaffa. Over 50 Jewish settlements were established in this period.

In 1890, Palestine, which was part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, was inhabited by about half a million people, mostly Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

and Christian Arabs

Arab Christians ( ar, ﺍَﻟْﻤَﺴِﻴﺤِﻴُّﻮﻥ ﺍﻟْﻌَﺮَﺏ, translit=al-Masīḥīyyūn al-ʿArab) are ethnic Arabs, Arab nationals, or Arabic-speakers who adhere to Christianity. The number of Arab Christians who ...

, but also some dozens of thousands Jews.

Establishment of the Zionist movement 1897–1917

Formation

In 1883, Nathan Birnbaum

Nathan Birnbaum ( he, נתן בירנבוים; pseudonyms: "Mathias Acher", "Dr. N. Birner", "Mathias Palme", "Anton Skart", "Theodor Schwarz", and "Pantarhei"; 16 May 1864 – 2 April 1937) was an Austrian writer and journalist, Jewish thinker a ...

, 19 years old, founded ''Kadimah'', the first Jewish student association in Vienna and printed Pinsker's pamphlet Auto-Emancipation

upThe book "Auto-Emancipation" by Pinsker, 1882

''Auto-Emancipation'' (''Selbstemanzipation'') is a pamphlet written in German by Russian-Polish Jewish doctor and activist Leo Pinsker in 1882. It is considered a founding document of modern Jewis ...

.

The Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

, which erupted in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in 1894, profoundly shocked emancipated Jews. The depth of antisemitism in the first country to grant Jews equal rights led many to question their future prospects among Christians. Among those who witnessed the Affair was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist, Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

. Herzl was born in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

and lived in Vienna (Jews were only allowed to live in Vienna from 1848), who published his pamphlet ''Der Judenstaat

''Der Judenstaat'' (German, literally ''The State of the Jews'', commonly rendered as ''The Jewish State'') is a pamphlet written by Theodor Herzl and published in February 1896 in Leipzig and Vienna by M. Breitenstein's Verlags-Buchhandlung. It ...

'' ("The Jewish State") in 1896 and ''Altneuland

''The Old New Land'' (german: Altneuland; he, תֵּל־אָבִיב ''Tel Aviv'', " Tel of spring"; yi, אַלטנײַלאַנד) is a utopian novel published by Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, in 1902. It was published six ye ...

'' ("The Old New Land") in 1902. He described the Affair as a personal turning point. Seeing Dreyfus's Jewishness used so successfully as a scapegoat by the monarchist propagandists disillusioned Herzl. Dreyfus's guilt was deemed indisputable simply because Jewish stereotypes of nefariousness prevented a fair trial from occurring. Herzl outright denied that any such Jewish stereotypes were rooted in reality in any way. However, he believed that anti-semitism was so deeply ingrained in European society that only the creation of a Jewish state would enable the Jews to join the family of nations and escape antisemitism.

Herzl Herzl is both a given name and a surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name:

*Herzl Berger

*Herzl Bodinger

*Herzl Rosenblum

*Herzl Yankl Tsam

Surname:

*Theodor Herzl

See also

*Mount Herzl

*''Herzl (play)

''Herzl'' is a 1976 play w ...

infused political Zionism with a new and practical urgency. He brought the World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

into being and, together with Nathan Birnbaum, planned its First Congress at Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

in 1897.

The objectives of Zionism

During the First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress ( he, הקונגרס הציוני הראשון) was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization (ZO) held in Basel (Basle), from August 29 to August 31, 1897. 208 delegates and 26 press correspondents attende ...

, the following agreement, commonly known as the Basel Program

The Basel Program was the first manifesto of the Zionist movement, drafted between 27-30 August 1897 and adopted unanimously at the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland on 30 August 1897.

In 1951 it was replaced by the Jerusalem Progra ...

, was reached:

Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

secured under public law. The Congress contemplates the following means to the attainment of this end:

#The promotion by appropriate means of the settlement in Palestine of Jewish farmers, artisans, and manufacturers.

#The organization and uniting of the whole of Jewry by means of appropriate institutions, both local and international, in accordance with the laws of each country.

#The strengthening and fostering of Jewish national sentiment and national consciousness.

#Preparatory steps toward obtaining the consent of governments, where necessary, in order to reach the goals of Zionism.

"Under public law" is generally understood to mean seeking legal permission from the Ottoman rulers for Jewish migration. In this text the word "home" was substituted for "state" and "public law" for "international law" so as not to alarm the Ottoman Sultan.

The organizational structure of the Zionist movement

For the first four years, the

For the first four years, the World Zionist Organization

The World Zionist Organization ( he, הַהִסְתַּדְּרוּת הַצִּיּוֹנִית הָעוֹלָמִית; ''HaHistadrut HaTzionit Ha'Olamit''), or WZO, is a non-governmental organization that promotes Zionism. It was founded as the ...

(WZO) met every year, then, up to the Second World War, they gathered every second year. Since the creation of Israel, the Congress has met every four years.

Congress delegates were elected by the membership. Members were required to pay dues known as a "shekel". At the congress, delegates elected a 30-man executive council, which in turn elected the movement's leader. The movement was democratic and women had the right to vote, which was still absent in Great Britain in 1914.

The WZO's initial strategy was to obtain permission from the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

to allow systematic Jewish settlement in Palestine. The support of the German Emperor, Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

, was sought, but unsuccessfully. Instead, the WZO pursued a strategy of building a homeland through persistent small-scale immigration and the founding of such bodies as the Jewish National Fund

Jewish National Fund ( he, קֶרֶן קַיֶּימֶת לְיִשְׂרָאֵל, ''Keren Kayemet LeYisrael'', previously , ''Ha Fund HaLeumi'') was founded in 1901 to buy and develop land in Ottoman Syria (later Mandatory Palestine, and subseq ...

(1901—a charity that bought land for Jewish settlement) and the Anglo-Palestine Bank

Bank Leumi ( he, בנק לאומי, lit. ''National Bank''; ar, بنك لئومي) is an Israeli bank. It was founded on February 27, 1902, in Jaffa as the ''Anglo Palestine Company'' as subsidiary of the Jewish Colonial Trust (Jüdische Kolonia ...

(1903—provided loans for Jewish businesses and farmers).

Cultural Zionism and opposition to Herzl

Herzl's strategy relied on winning support from foreign rulers, in particular the Ottoman Sultan

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı padişahları), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to its dissolution in 1922. At its hei ...

. He also made efforts to cultivate Orthodox rabbinical support. Rabbinical support depended on the Zionist movement making no challenges to existing Jewish tradition. However, an opposition movement arose that emphasized the need for a revolution in Jewish thought. While Herzl believed that the Jews needed to return to their historic homeland as a refuge from antisemitism, the opposition, led by Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, believed that the Jews must revive and foster a Jewish national culture and, in particular strove to revive the Hebrew language. Many also adopted Hebraized surnames. The opposition became known as Cultural Zionists. Important Cultural Zionists include Ahad Ha'am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

, Nahum Sokolow

Nahum ben Joseph Samuel Sokolow ( he, נחום ט' סוקולוב ''Nachum ben Yosef Shmuel Soqolov'', yi, סאָקאָלאָוו; ) was a Zionist leader, author, translator, and a pioneer of Hebrew journalism.

Biography

Nahum Sokolow was born ...

and Menachem Ussishkin

Menachem Ussishkin (russian: Авраам Менахем Мендл Усышкин ''Avraham Menachem Mendel Ussishkin'', he, מנחם אוסישקין) (August 14, 1863 – October 2, 1941) was a Russian-born Zionism, Zionist leader and head ...

.

The "Uganda" proposal

In 1903, the British Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

, suggested the British Uganda Programme

The Uganda Scheme was a proposal presented at the Sixth World Zionist Congress in Basel in 1903 by Zionism founder Theodor Herzl to create a Jewish homeland in a portion of British East Africa. He presented it as a temporary refuge for Jews to ...

, land for a Jewish state in "Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

" (in today's Uasin Gishu District, Eldoret

Eldoret is a principal town in the Rift Valley region of Kenya and serves as the capital of Uasin Gishu County. The town was referred to by white settlers as Farm 64, 64 and colloquially by locals as 'Sisibo'. As per the 2019 Kenya Population ...

, Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

). Herzl initially rejected the idea, preferring Palestine, but after the April 1903 Kishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octobe ...

, Herzl introduced a controversial proposal to the Sixth Zionist Congress

The Sixth Zionist Congress was held in Basel, opening on August 23, 1903. Theodor Herzl caused great division amongst the delegates when he presented the " Uganda Scheme", a proposed Jewish colony in what is now part of Kenya. Herzl died the follo ...

to investigate the offer as a temporary measure for Russian Jews in danger. Despite its emergency and temporary nature, the proposal proved very divisive, and widespread opposition to the plan was fueled by a walkout led by the Russian Jewish delegation to the Congress. Nevertheless, a committee was established to investigate the possibility, which was eventually dismissed in the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905. After that, Palestine became the sole focus of Zionist aspirations.

Israel Zangwill

Israel Zangwill (21 January 18641 August 1926) was a British author at the forefront of cultural Zionism during the 19th century, and was a close associate of Theodor Herzl. He later rejected the search for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and be ...

left the main Zionist movement over this decision and founded the Jewish Territorialist Organization

The Jewish Territorial Organisation, known as the ITO, was a Jewish political movement which first arose in 1903 in response to the British Uganda Offer, but which was institutionalized in 1905. Its main goal was to find an alternative territory ...

(ITO). The territorialists were willing to establish a Jewish homeland anywhere, but failed to attract significant support and were dissolved in 1925.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

In 1903, following the Kishinev Pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octobe ...

, a variety of Russian antisemities, including the Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

and the Tsarist Secret Police, began combining earlier works alleging a Jewish plot to take control of the world into new formats. One particular version of these allegations, "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

" (subtitle "Protocols extracted from the secret archives of the central chancery of Zion"), arranged by Sergei Nilus

Sergei Aleksandrovich Nilus (also ''Sergius'', and variants; russian: Серге́й Алекса́ндрович Ни́лус; – 14 January 1929) was a Russian religious writer and self-described mystic.

His book ''Velikoe v malom i antik ...

, achieved global notability. In 1903, the editor claimed that the protocols revealed the menace of Zionism:

The book contains fictional minutes of an imaginary meeting in which alleged Jewish leaders plotted to take over the world. Nilus later claimed they were presented to the elders by Herzl (the "Prince of Exile") at the first Zionist congress. A Polish edition claimed they were taken from Herzl's flat in Austria and a 1920 German version renamed them "The Zionist Protocols

''The Protocols of the Elders of Zion'' () or ''The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion'' is a fabricated antisemitic text purporting to describe a Jewish plan for global domination. The hoax was plagiarized from several ...

".

The death of Herzl

By 1904, cultural Zionism was accepted by most Zionists and a schism was beginning to develop between the Zionist movement and Orthodox Judaism. In 1904, Herzl died unexpectedly at the age of 44 and the leadership was taken over by David Wolffsohn

David Wolffsohn ( yi, דוד וואלפסאן; he, דוד וולפסון; 9 October 1855 in Darbėnai, Kovno Governorate – 15 September 1914) was a Lithuanian-Jewish businessman, prominent early Zionist and second president of the Zion ...

, who led the movement until 1911. During this period, the movement was based in Berlin (Germany's Jews were the most assimilated) and made little progress, failing to win support among the Young Turks after the collapse of the Ottoman Regime. From 1911 to 1921, the movement was led by Dr. Otto Warburg Otto Warburg may refer to:

*Otto Warburg (botanist) (1859–1938), German botanist

*Otto Heinrich Warburg

Otto Heinrich Warburg (, ; 8 October 1883 – 1 August 1970), son of physicist Emil Warburg, was a German physiologist, medical doctor, and ...

.

Zionism breaks with Orthodox Judaism and moves towards Communism

Jewish Orthodox and Reform opposition

Under Herzl's leadership, Zionism relied on Orthodox Jews

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Jewish theology, Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Torah, Written and Oral Torah, Or ...

for religious support, with the main party being the orthodox Mizrachi. However, as the cultural and socialist Zionists increasingly broke with tradition and used language contrary to the outlook of most religious Jewish communities, many orthodox religious organizations began opposing Zionism. Their opposition was based on its secularism and on the grounds that only the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

could re-establish Jewish rule in Israel. Therefore, most Orthodox Jews maintained the traditional Jewish belief that while the Land of Israel was given to the ancient Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

by God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

, and the right of the Jews to that land was permanent and inalienable, the Messiah must appear before the land could return to Jewish control.

Prior to the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

rejected Zionism as inconsistent with the requirements of Jewish citizenship in the diaspora. The opposition of Reform Judaism was expressed in the Pittsburgh Platform The Pittsburgh Platform is a pivotal 1885 document in the history of the American Reform Movement in Judaism that called for Jews to adopt a modern approach to the practice of their faith. While it was never formally adopted by the Union of America ...

, adopted by the Central Conference of American Rabbis in 1885: "We consider ourselves no longer a nation but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the administration of the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state."

The second aliya

Widespread pogroms accompanied the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, inspired by the Pro-Tsarist Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

. In Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

provided arms so the Zionists could protect the Jewish community and this prevented a pogrom. Zionist leader Jabotinsky eventually led the Jewish resistance in Odessa. During his subsequent trial Trotsky produced evidence that the police had organized the effort to create a pogrom in Odessa.

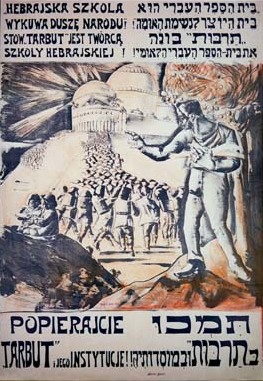

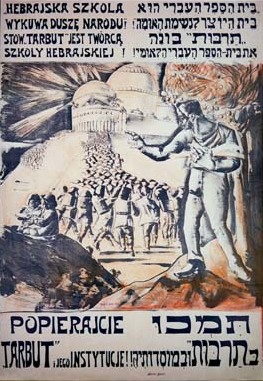

The vicious pogroms led to a wave of immigrants to Palestine. This new wave expanded the Revival of the Hebrew language

The revival of the Hebrew language took place in Europe and Palestine toward the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, through which the language's usage changed from the sacred language of Judaism to a spoken and written language ...

. In 1909 a group of 65 Zionists laid the foundations for a modern city in Palestine. The city was named after the Hebrew title of Herzl's book "The Old New Land

''The Old New Land'' (german: Altneuland; he, תֵּל־אָבִיב ''Tel Aviv'', " Tel of spring"; yi, אַלטנײַלאַנד) is a utopian novel published by Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, in 1902. It was published six ye ...

" - Tel-Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the ...

.

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

had a modern "scientific" school, the Herzliya Hebrew High School