Theophrastus Nuremberg Chronicle.jpg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

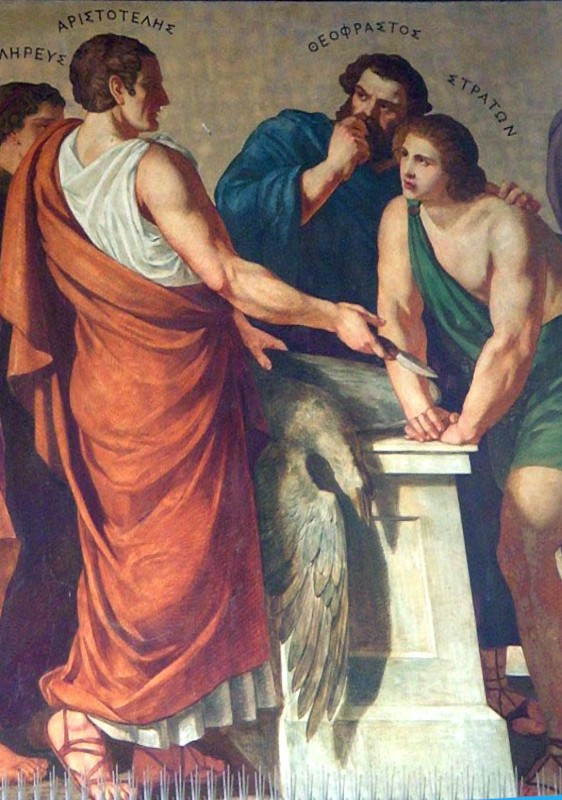

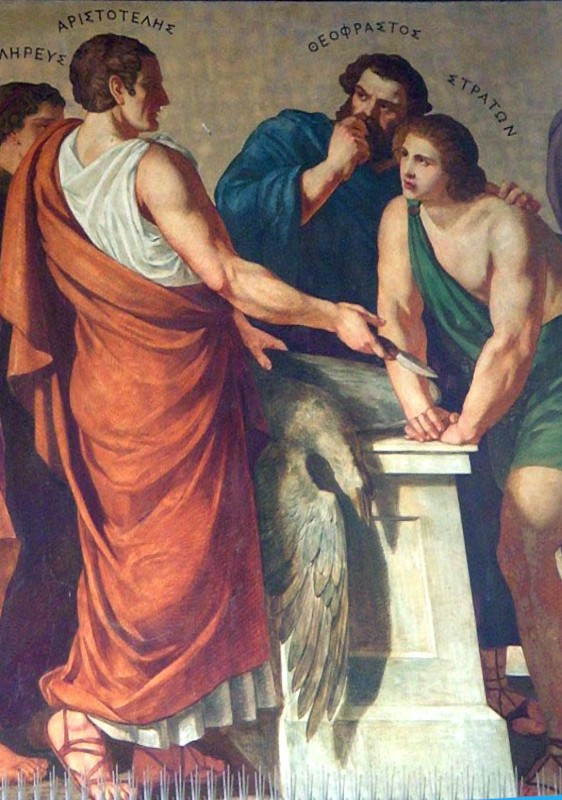

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge, 2015, p. 8. His given name was Tyrtamus (); his nickname (or 'godly phrased') was given by Aristotle, his teacher, for his "divine style of expression".

He came to Athens at a young age and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death, he attached himself to Aristotle who took to Theophrastus in his writings. When Aristotle fled Athens, Theophrastus took over as head of the Lyceum. Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for thirty-six years, during which time the school flourished greatly. He is often considered the father of botany for his works on plants. After his death, the Athenians honoured him with a public funeral. His successor as head of the school was Strato of Lampsacus.

The interests of Theophrastus were wide ranging, including from biology, physics, ethics and metaphysics. His two surviving botanical works, '' Enquiry into Plants (Historia Plantarum)'' and ''On the Causes of Plants'', were an important influence on

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to Athens, where he may have studied under Plato. He became friends with Aristotle, and when Plato died (348/7 BC) Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle in his self-imposed exile from Athens. When Aristotle moved to Mytilene on Lesbos in 345/4, it is very likely that he did so at the urging of Theophrastus. It seems that it was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to Athens, where he may have studied under Plato. He became friends with Aristotle, and when Plato died (348/7 BC) Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle in his self-imposed exile from Athens. When Aristotle moved to Mytilene on Lesbos in 345/4, it is very likely that he did so at the urging of Theophrastus. It seems that it was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

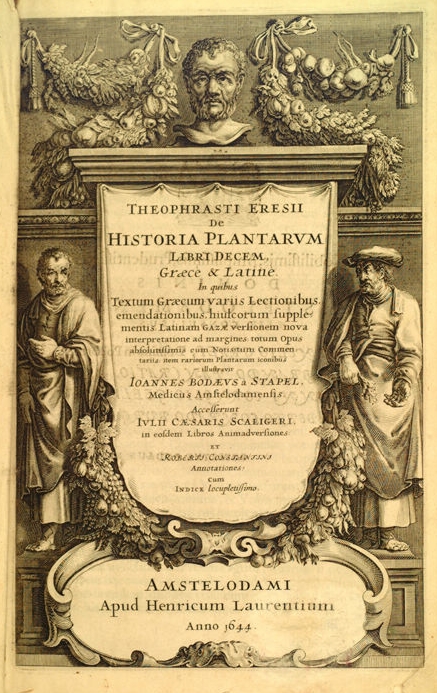

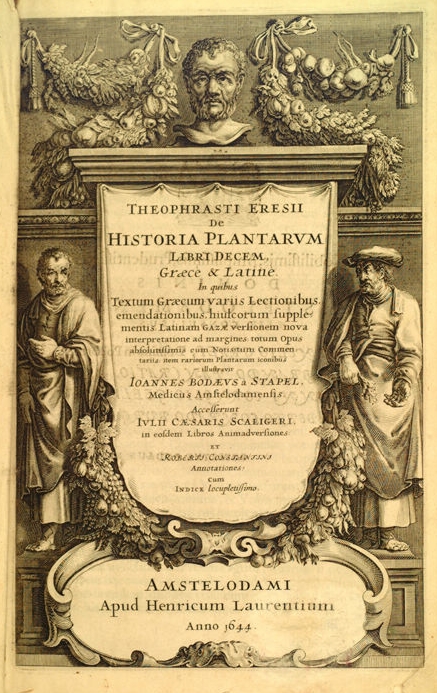

The most important of his books are two large botanical treatises, '' Enquiry into Plants'' (, generally known as ), and ''On the Causes of Plants'' ( Greek: , Latin: ), which constitute the most important contribution to botanical science during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first systemization of the botanical world; on the strength of these works some, following Linnaeus, call him the "father of botany".

The ''Enquiry into Plants'' was originally ten books, of which nine survive. The work is arranged into a system whereby plants are classified according to their modes of generation, their localities, their sizes, and according to their practical uses such as foods, juices, herbs, etc. The first book deals with the parts of plants; the second book with the reproduction of plants and the times and manner of sowing; the third, fourth, and fifth books are devoted to trees, their types, their locations, and their practical applications; the sixth book deals with shrubs and spiny plants; the seventh book deals with herbs; the eighth book deals with plants that produce edible seeds; and the ninth book deals with plants that produce useful juices, gums, resins, etc.

The most important of his books are two large botanical treatises, '' Enquiry into Plants'' (, generally known as ), and ''On the Causes of Plants'' ( Greek: , Latin: ), which constitute the most important contribution to botanical science during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first systemization of the botanical world; on the strength of these works some, following Linnaeus, call him the "father of botany".

The ''Enquiry into Plants'' was originally ten books, of which nine survive. The work is arranged into a system whereby plants are classified according to their modes of generation, their localities, their sizes, and according to their practical uses such as foods, juices, herbs, etc. The first book deals with the parts of plants; the second book with the reproduction of plants and the times and manner of sowing; the third, fourth, and fifth books are devoted to trees, their types, their locations, and their practical applications; the sixth book deals with shrubs and spiny plants; the seventh book deals with herbs; the eighth book deals with plants that produce edible seeds; and the ninth book deals with plants that produce useful juices, gums, resins, etc.

''On the Causes of Plants'' was originally eight books, of which six survive. It concerns the growth of plants; the influences on their fecundity; the proper times they should be sown and reaped; the methods of preparing the soil, manuring it, and the use of tools; and of the smells, tastes, and properties of many types of plants. The work deals mainly with the economical uses of plants rather than their medicinal uses, although the latter is sometimes mentioned. A book on wines and a book on plant smells may have once been part of the complete work.

Although these works contain many absurd and fabulous statements, they include valuable observations concerning the functions and properties of plants. Theophrastus detected the process of

''On the Causes of Plants'' was originally eight books, of which six survive. It concerns the growth of plants; the influences on their fecundity; the proper times they should be sown and reaped; the methods of preparing the soil, manuring it, and the use of tools; and of the smells, tastes, and properties of many types of plants. The work deals mainly with the economical uses of plants rather than their medicinal uses, although the latter is sometimes mentioned. A book on wines and a book on plant smells may have once been part of the complete work.

Although these works contain many absurd and fabulous statements, they include valuable observations concerning the functions and properties of plants. Theophrastus detected the process of

In his treatise ''On Stones'' (), which would become a source for other

In his treatise ''On Stones'' (), which would become a source for other

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as Alexander of Aphrodisias and Simplicius.

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as Alexander of Aphrodisias and Simplicius.

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only potentially exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:

He recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment () and contemplation to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit entirely independent of organic activity, must therefore have appeared to him very doubtful; yet he appears to have contented himself with developing his doubts and difficulties on the point, without positively rejecting it. Other Peripatetics, like Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and especially Strato, developed further this naturalism in Aristotelian doctrine.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his ''Metaphysics''. He was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:

He did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena. In antiquity, it was a subject of complaint that Theophrastus had not expressed himself with precision and consistency respecting God, and had understood it at one time as

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only potentially exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:

He recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment () and contemplation to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit entirely independent of organic activity, must therefore have appeared to him very doubtful; yet he appears to have contented himself with developing his doubts and difficulties on the point, without positively rejecting it. Other Peripatetics, like Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and especially Strato, developed further this naturalism in Aristotelian doctrine.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his ''Metaphysics''. He was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:

He did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena. In antiquity, it was a subject of complaint that Theophrastus had not expressed himself with precision and consistency respecting God, and had understood it at one time as

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality. He subordinated moral requirements to the advantage at least of a friend, and had allowed in prosperity the existence of an influence injurious to them. In later times, fault was found with his expression in the ''Callisthenes'', "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom" ('). That in the definition of pleasure, likewise, he did not coincide with Aristotle, seems to be indicated by the titles of two of his writings, one of which dealt with pleasure generally, the other with pleasure as Aristotle had defined it. Although, like his teacher, he preferred contemplative (theoretical), to active (practical) life, he preferred to set the latter free from the restraints of family life, etc. in a manner of which Aristotle would not have approved.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.Taylor, Angus. ''Animals and Ethics''. Broadview Press, p. 35.

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality. He subordinated moral requirements to the advantage at least of a friend, and had allowed in prosperity the existence of an influence injurious to them. In later times, fault was found with his expression in the ''Callisthenes'', "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom" ('). That in the definition of pleasure, likewise, he did not coincide with Aristotle, seems to be indicated by the titles of two of his writings, one of which dealt with pleasure generally, the other with pleasure as Aristotle had defined it. Although, like his teacher, he preferred contemplative (theoretical), to active (practical) life, he preferred to set the latter free from the restraints of family life, etc. in a manner of which Aristotle would not have approved.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.Taylor, Angus. ''Animals and Ethics''. Broadview Press, p. 35.

*

*

* '' Metaphysics'' (or ''On First Principles'').

** Translated by M. van Raalte, 1993, Brill.

** ''On First Principles.'' Translated by Dimitri Gutas, 2010, Brill.

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 1-5.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916. Loeb Classical Library.

*

*

* '' Metaphysics'' (or ''On First Principles'').

** Translated by M. van Raalte, 1993, Brill.

** ''On First Principles.'' Translated by Dimitri Gutas, 2010, Brill.

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 1-5.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916. Loeb Classical Library.

Vol 1

�

Vol 2

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 6-9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1926. Loeb Classical Library. ** * . Translated to French by Suzanne Amigues. Paris, Les Belles Lettres. 1988–2006. 5 tomes. Tome 1, Livres I-II. 1988. LVIII-146 p. Tome II, Livres III-IV. 1989. 306 p. Tome III, Livres V-VI. 1993. 212 p. Tome IV, Livres VII-VIII, 2003. 238 p. Tome V, Livres IX. 2006. LXX-400 p. First edition in French. Identifications are up-to-date, and carefully checked with botanists. Greek names with identifications are o

Pl@ntUse

* . Translated by B. Einarson and G. Link, 1989–1990. Loeb Classical Library. 3 volumes: , , .

*

Translated by R. C. Jebb

1870. *

Translated by J. M. Edmonds

1929, with parallel text. ** Translated by J. Rusten, 2003. Loeb Classical Library. * ''On Sweat, On Dizziness and On Fatigue.'' Translated by W. Fortenbaugh, R. Sharples, M. Sollenberger. Brill 2002. * ''On Weather Signs.'' *

Translated by J. G. Wood, G. J. Symons

1894. ** Edited by Sider David and Brunschön Carl Wolfram. Brill 2007. *

On Stones

'

International Theophrastus Project

started by

Works by Theophrastus at Perseus Digital Library

* * * * * —Contains a translation of ''On the Senses'' by Theophrastus. * *

Project ''Theophrastus''

Online Galleries, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Theophrastus of Eresus at the Edward Worth Library, Dublin

Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, Hort's English translation of 1916

as html tagged with geolocated place references, a

ToposText

* * {{Authority control 370s BC births 280s BC deaths 4th-century BC Greek people 4th-century BC philosophers 4th-century BC writers 3rd-century BC Greek people 3rd-century BC philosophers 3rd-century BC writers Ancient Eresians Ancient Greek biologists Ancient Greek botanists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek logicians Ancient Greek metaphilosophers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek philosophers Ancient Greek philosophers of mind Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek science writers Cultural critics Ancient Greek epistemologists Moral philosophers Ontologists Peripatetic philosophers Philosophers of culture Philosophers of education Philosophers of ethics and morality Ancient Greek philosophers of language Philosophers of logic Philosophers of science Philosophy writers Pre-Linnaean botanists Social critics Social philosophers Virtue ethicists

Renaissance science

During the Renaissance, great advances occurred in geography, astronomy, chemistry, physics, mathematics, manufacturing, anatomy and engineering. The collection of ancient scientific texts began in earnest at the start of the 15th century and co ...

. There are also surviving works ''On Moral Characters'', ''On Sense Perception'', and ''On Stones'', as well as fragments on ''Physics'' and ''Metaphysics''. In philosophy, he studied grammar and language and continued Aristotle's work on logic. He also regarded space as the mere arrangement and position of bodies, time as an accident of motion, and motion as a necessary consequence of all activity. In ethics, he regarded happiness as depending on external influences as well as on virtue.

Life

Most of the biographical information about Theophrastus was provided byDiogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

' ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

'', written more than four hundred years after Theophrastus's time. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos. His given name was Tyrtamus (), but he later became known by the nickname "Theophrastus", given to him, it is said, by Aristotle to indicate the grace of his conversation (from Ancient Greek 'god' and 'to phrase', i.e. divine expression).

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to Athens, where he may have studied under Plato. He became friends with Aristotle, and when Plato died (348/7 BC) Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle in his self-imposed exile from Athens. When Aristotle moved to Mytilene on Lesbos in 345/4, it is very likely that he did so at the urging of Theophrastus. It seems that it was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into

After receiving instruction in philosophy on Lesbos from one Alcippus, he moved to Athens, where he may have studied under Plato. He became friends with Aristotle, and when Plato died (348/7 BC) Theophrastus may have joined Aristotle in his self-imposed exile from Athens. When Aristotle moved to Mytilene on Lesbos in 345/4, it is very likely that he did so at the urging of Theophrastus. It seems that it was on Lesbos that Aristotle and Theophrastus began their research into natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

, with Aristotle studying animals and Theophrastus studying plants. Theophrastus probably accompanied Aristotle to Macedonia when Aristotle was appointed tutor to Alexander the Great in 343/2. Around 335 BC, Theophrastus moved with Aristotle to Athens, where Aristotle began teaching in the Lyceum. When, after the death of Alexander, anti-Macedonian feeling forced Aristotle to leave Athens, Theophrastus remained behind as head ('' scholarch'') of the Peripatetic school, a position he continued to hold after Aristotle's death in 322/1.

Aristotle in his will made him guardian of his children, including Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa ( grc-gre, Νικόμαχος; c. 60 – c. 120 AD) was an important ancient mathematician and music theorist, best known for his works ''Introduction to Arithmetic'' and ''Manual of Harmonics'' in Greek. He was born in ...

, with whom he was close. Aristotle likewise bequeathed to him his library and the originals of his works, and designated him as his successor at the Lyceum. Eudemus of Rhodes also had some claims to this position, and Aristoxenus is said to have resented Aristotle's choice.

Theophrastus presided over the Peripatetic school for thirty-five years, and died at the age of eighty-five according to Diogenes.

He is said to have remarked, "We die just when we are beginning to live".

Under his guidance the school flourished greatly—there were at one period more than 2000 students, Diogenes affirms—and at his death, according to the terms of his will preserved by Diogenes, he bequeathed to it his garden with house and colonnades as a permanent seat of instruction. The comic poet Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

was among his pupils. His popularity was shown in the regard paid to him by Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, Cassander, and Ptolemy, and by the complete failure of a charge of impiety brought against him. He was honored with a public funeral, and "the whole population of Athens, honouring him greatly, followed him to the grave." He was succeeded as head of the Lyceum by Strato of Lampsacus.

Writings

From the lists of Diogenes, giving 227 titles, it appears that the activity of Theophrastus extended over the whole field of contemporary knowledge. His writing probably differed little from Aristotle's treatment of the same themes, though supplementary in details. Like Aristotle, most of his writings arelost work

A lost work is a document, literary work, or piece of multimedia produced some time in the past, of which no surviving copies are known to exist. It can only be known through reference. This term most commonly applies to works from the classical ...

s. Thus Theophrastus, like Aristotle, had composed a first and second ''Analytic'' ( and ). He had also written books on ''Topics'' (, and ); on the ''Analysis of Syllogisms'' ( and ), on ''Sophisms'' () and on ''Affirmation and Denial'' () as well as on the ''Natural Philosophy'' (, , and others), on ''Heaven'' (), and on ''Meteorological Phenomena'' ( and ).

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes,

In addition, Theophrastus wrote on the ''Warm and the Cold'' (), on ''Water'' (), ''Fire'' (), the ''Sea'' (), on ''Coagulation and Melting'' (), on various phenomena of organic and spiritual life, and on the ''Soul'' (), on ''Experience'' () and ''On Sense Perception'' (also known as ''On the Senses''; ). Likewise, we find mention of monographs of Theophrastus on the early Greek philosophers Anaximenes, Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; grc-gre, Ἀναξαγόρας, ''Anaxagóras'', "lord of the assembly"; 500 – 428 BC) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, ...

, Empedocles, Archelaus, Diogenes of Apollonia

Diogenes of Apollonia ( ; grc, Διογένης ὁ Ἀπολλωνιάτης, Diogénēs ho Apollōniátēs; 5th century BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher, and was a native of the Milesian colony Apollonia in Thrace. He lived for some ti ...

, Democritus, which were made use of by Simplicius; and also on Xenocrates, against the Academics, and a sketch of the political doctrine of Plato.

He studied general history, as we know from Plutarch's lives of Lycurgus

Lycurgus or Lykourgos () may refer to:

People

* Lycurgus (king of Sparta) (third century BC)

* Lycurgus (lawgiver) (eighth century BC), creator of constitution of Sparta

* Lycurgus of Athens (fourth century BC), one of the 'ten notable orators' ...

, Solon, Aristides, Pericles, Nicias, Alcibiades

Alcibiades ( ; grc-gre, Ἀλκιβιάδης; 450 – 404 BC) was a prominent Athenian statesman, orator, and general. He was the last of the Alcmaeonidae, which fell from prominence after the Peloponnesian War. He played a major role in t ...

, Lysander, Agesilaus, and Demosthenes, which were probably borrowed from the work on ''Lives'' (). But his main efforts were to continue the labours of Aristotle in natural history. This is testified to not only by a number of treatises on individual subjects of zoology, of which, besides the titles, only fragments remain, but also by his books ''On Stones'', his ''Enquiry into Plants'', and ''On the Causes of Plants'' (see below), which have come down to us entire. In politics, also, he seems to have trodden in the footsteps of Aristotle. Besides his books on the ''State'' ( and ), we find quoted various treatises on ''Education'' ( and ), on ''Royalty'' (, and ), on the ''Best State'' (), on ''Political Morals'' (), and particularly his works on the ''Laws'' (, and ), one of which, containing a recapitulation of the laws of various barbarian

A barbarian (or savage) is someone who is perceived to be either Civilization, uncivilized or primitive. The designation is usually applied as a generalization based on a popular stereotype; barbarians can be members of any nation judged by som ...

as well as Greek states, was intended to be a companion to Aristotle's outline of ''Politics'', and must have been similar to it. He also wrote on oratory and poetry. Theophrastus, without doubt, departed further from Aristotle in his ethical writings, as also in his metaphysical investigations of motion, the soul, and God.

Besides these writings, Theophrastus wrote several collections of problems, out of which some things at least have passed into the '' Problems'' that have come down to us under the name of Aristotle, and commentaries, partly dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is c ...

, to which probably belonged the ''Erotikos'' (), ''Megacles'' (), ''Callisthenes'' (), and ''Megarikos'' (), and letters, partly books on mathematical sciences and their history.

Many of his surviving works exist only in fragmentary form. "The style of these works, as of the botanical books, suggests that, as in the case of Aristotle, what we possess consists of notes for lectures or notes taken of lectures," his translator Arthur F. Hort remarks. "There is no literary charm; the sentences are mostly compressed and highly elliptical, to the point sometimes of obscurity". The text of these fragments and extracts is often so corrupt that there is a certain plausibility to the well-known story that the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus were allowed to languish in the cellar of Neleus of Scepsis

Neleus of Scepsis (; el, Νηλεύς), was the son of Coriscus of Scepsis. He was a disciple of Aristotle and Theophrastus, the latter of whom bequeathed to him his library, and appointed him one of his executors. Neleus supposedly took the writi ...

and his descendants.

On plants

The most important of his books are two large botanical treatises, '' Enquiry into Plants'' (, generally known as ), and ''On the Causes of Plants'' ( Greek: , Latin: ), which constitute the most important contribution to botanical science during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first systemization of the botanical world; on the strength of these works some, following Linnaeus, call him the "father of botany".

The ''Enquiry into Plants'' was originally ten books, of which nine survive. The work is arranged into a system whereby plants are classified according to their modes of generation, their localities, their sizes, and according to their practical uses such as foods, juices, herbs, etc. The first book deals with the parts of plants; the second book with the reproduction of plants and the times and manner of sowing; the third, fourth, and fifth books are devoted to trees, their types, their locations, and their practical applications; the sixth book deals with shrubs and spiny plants; the seventh book deals with herbs; the eighth book deals with plants that produce edible seeds; and the ninth book deals with plants that produce useful juices, gums, resins, etc.

The most important of his books are two large botanical treatises, '' Enquiry into Plants'' (, generally known as ), and ''On the Causes of Plants'' ( Greek: , Latin: ), which constitute the most important contribution to botanical science during antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first systemization of the botanical world; on the strength of these works some, following Linnaeus, call him the "father of botany".

The ''Enquiry into Plants'' was originally ten books, of which nine survive. The work is arranged into a system whereby plants are classified according to their modes of generation, their localities, their sizes, and according to their practical uses such as foods, juices, herbs, etc. The first book deals with the parts of plants; the second book with the reproduction of plants and the times and manner of sowing; the third, fourth, and fifth books are devoted to trees, their types, their locations, and their practical applications; the sixth book deals with shrubs and spiny plants; the seventh book deals with herbs; the eighth book deals with plants that produce edible seeds; and the ninth book deals with plants that produce useful juices, gums, resins, etc.

''On the Causes of Plants'' was originally eight books, of which six survive. It concerns the growth of plants; the influences on their fecundity; the proper times they should be sown and reaped; the methods of preparing the soil, manuring it, and the use of tools; and of the smells, tastes, and properties of many types of plants. The work deals mainly with the economical uses of plants rather than their medicinal uses, although the latter is sometimes mentioned. A book on wines and a book on plant smells may have once been part of the complete work.

Although these works contain many absurd and fabulous statements, they include valuable observations concerning the functions and properties of plants. Theophrastus detected the process of

''On the Causes of Plants'' was originally eight books, of which six survive. It concerns the growth of plants; the influences on their fecundity; the proper times they should be sown and reaped; the methods of preparing the soil, manuring it, and the use of tools; and of the smells, tastes, and properties of many types of plants. The work deals mainly with the economical uses of plants rather than their medicinal uses, although the latter is sometimes mentioned. A book on wines and a book on plant smells may have once been part of the complete work.

Although these works contain many absurd and fabulous statements, they include valuable observations concerning the functions and properties of plants. Theophrastus detected the process of germination

Germination is the process by which an organism grows from a seed or spore. The term is applied to the sprouting of a seedling from a seed of an angiosperm or gymnosperm, the growth of a sporeling from a spore, such as the spores of fungi, fer ...

and realized the importance of climate and soil to plants. Much of the information on the Greek plants may have come from his own observations, as he is known to have travelled throughout Greece, and to have had a botanical garden of his own; but the works also profit from the reports on plants of Asia brought back from those who followed Alexander the Great:

Theophrastus's ''Enquiry into Plants'' was first published in a Latin translation by Theodore Gaza, at Treviso, 1483; in its original Greek it first appeared from the press of Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; it, Aldo Pio Manuzio; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preserv ...

at Venice, 1495–98, from a third-rate manuscript, which, like the majority of the manuscripts that were sent to printers' workshops in the fifteenth and sixteenth century, has disappeared. Christian Wimmer identified two manuscripts of first quality, the ''Codex Urbinas'' in the Vatican Library, which was not made known to J. G. Schneider, who made the first modern critical edition, 1818–21, and the excerpts in the ''Codex Parisiensis'' in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository ...

.

On moral characters

His book ''Characters'' () contains thirty brief outlines of moral types. They are the first recorded attempt at systematic character writing. The book has been regarded by some as an independent work; others incline to the view that the sketches were written from time to time by Theophrastus, and collected and edited after his death; others, again, regard the ''Characters'' as part of a larger systematic work, but the style of the book is against this. Theophrastus has found many imitators in this kind of writing, notably Joseph Hall (1608), Sir Thomas Overbury (1614–16), Bishop Earle (1628), andJean de La Bruyère

Jean de La Bruyère (, , ; 16 August 1645 – 11 May 1696) was a French philosopher and moralist, who was noted for his satire.

Early years

Jean de La Bruyère was born in Paris, in today's Essonne ''département'', in 1645. His family was mid ...

(1688), who also translated the ''Characters''. George Eliot also took inspiration from Theophrastus's ''Characters'', most notably in her book of caricatures, '' Impressions of Theophrastus Such''. Writing the "character sketch" as a scholastic exercise also originated in Theophrastus's typology.

On sensation

A treatise ''On Sense Perception'' () and its objects is important for a knowledge of the doctrines of the more ancient Greek philosophers regarding the subject. A paraphrase and commentary on this work was written by Priscian of Lydia in the sixth century. With this type of work we may connect the fragments on ''Smells'', on ''Fatigue'', on ''Dizziness'', on ''Sweat'', on ''Swooning'', on ''Palsy'', and on ''Honey''.Physics

Fragments of a ''History of Physics'' () are extant. To this class of work belong the still extant sections on ''Fire'', on the ''Winds'', and on the signs of ''Waters'', ''Winds'', and ''Storms''. Various smaller scientific fragments have been collected in the editions of Johann Gottlob Schneider (1818–21) and Friedrich Wimmer (1842–62) and inHermann Usener

Hermann Karl Usener (23 October 1834 – 21 October 1905) was a German scholar in the fields of philology and comparative religion.

Life

Hermann Usener was born at Weilburg and educated at its Gymnasium. From 1853 he studied at Heidelberg, ...

's ''Analecta Theophrastea''.

Metaphysics

The ''Metaphysics'' (anachronistic Greek title: ), in nine chapters (also known as ''On First Principles''), was considered a fragment of a larger work by Usener in his edition (Theophrastos, ''Metaphysica'', Bonn, 1890), but according to Ross and Fobes in their edition (Theophrastus, ''Metaphysica'', Oxford, 1929), the treatise is complete (p. X) and this opinion is now widely accepted. There is no reason for assigning this work to some other author because it is not noticed in Hermippus and Andronicus, especially as Nicolaus of Damascus had already mentioned it.On stones

lapidaries

Lapidary (from the Latin ) is the practice of shaping stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as cabochons, engraved gems (including cameos), and faceted designs. A person who practices lapidary is known as a lapidarist. A la ...

until at least the Renaissance, Theophrastus classified rocks and gems based on their behavior when heated, further grouping minerals by common properties, such as amber and magnetite, which both have the power of attraction..

Theophrastus describes different marbles; mentions coal, which he says is used for heating by metal-workers; describes the various metal ores; and knew that pumice stones had a volcanic origin. He also deals with precious stones, emeralds

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991) ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, p. ...

, amethysts, onyx, jasper, etc., and describes a variety of "sapphire" that was blue with veins of gold, and thus was presumably lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines, ...

.

He knew that pearls

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle (mollusc), mantle) of a living animal shell, shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pea ...

came from shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

, that coral came from India, and speaks of the fossilized remains of organic life. Theophrastus made the first known reference to the phenomenon, now known to be caused by pyroelectricity, that the mineral lyngurium

Lyngurium or Ligurium is the name of a mythical gemstone believed to be formed of the solidified urine of the lynx (the best ones coming from wild males). It was included in classical and "almost every medieval lapidary" or book of gems until it gr ...

(probably tourmaline) attracts straws and bits of wood when heated. He also considers the practical uses of various stones, such as the minerals necessary for the manufacture of glass; for the production of various pigments of paint such as ochre

Ochre ( ; , ), or ocher in American English, is a natural clay earth pigment, a mixture of ferric oxide and varying amounts of clay and sand. It ranges in colour from yellow to deep orange or brown. It is also the name of the colours produced ...

; and for the manufacture of plaster.

Many of the rarer minerals were found in mines, and Theophrastus mentions the famous copper mines of Cyprus and the even more famous silver mine

Silver mining is the extraction of silver from minerals, starting with mining. Because silver is often found in intimate combination with other metals, its extraction requires elaborate technologies. In 2008, ca.25,900 metric tons were consumed ...

s, presumably of Laurium near Athens – the basis of the wealth of the city – as well as referring to gold mines. The Laurium silver mines, which were the property of the state, were usually leased for a fixed sum and a percentage on the working. Towards the end of the fifth century BCE the output fell, partly owing to the Spartan occupation of Decelea from BCE. But the mines continued to be worked, though Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

( BCE to CE) records that in his time the tailings were being worked over, and Pausanias ( to ) speaks of the mines as a thing of the past. The ancient workings, consisting of shafts and galleries for excavating the ore, and washing tables for extracting the metal, may still be seen. Theophrastus wrote a separate work ''On Mining'', which – like most of his writings – is a lost work

A lost work is a document, literary work, or piece of multimedia produced some time in the past, of which no surviving copies are known to exist. It can only be known through reference. This term most commonly applies to works from the classical ...

.

Pliny the Elder makes clear references to his use of ''On Stones'' in his '' Naturalis Historia'' of 77 AD, while updating and making much new information available on minerals himself. Although Pliny's treatment of the subject is more extensive, Theophrastus is more systematic and his work is comparatively free from fable and magic, although he did describe lyngurium

Lyngurium or Ligurium is the name of a mythical gemstone believed to be formed of the solidified urine of the lynx (the best ones coming from wild males). It was included in classical and "almost every medieval lapidary" or book of gems until it gr ...

, a gemstone supposedly formed of the solidified urine of the lynx

A lynx is a type of wild cat.

Lynx may also refer to:

Astronomy

* Lynx (constellation)

* Lynx (Chinese astronomy)

* Lynx X-ray Observatory, a NASA-funded mission concept for a next-generation X-ray space observatory

Places Canada

* Lynx, Ontar ...

(the best ones coming from wild males), which featured in many lapidaries until it gradually disappeared from view in the 17th century.

Philosophy

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as Alexander of Aphrodisias and Simplicius.

The extent to which Theophrastus followed Aristotle's doctrines, or defined them more accurately, or conceived them in a different form, and what additional structures of thought he placed upon them, can only be partially determined because of the loss of so many of his writings. Many of his opinions have to be reconstructed from the works of later writers such as Alexander of Aphrodisias and Simplicius.

Logic

Theophrastus seems to have carried out still further thegrammatical

In linguistics, grammaticality is determined by the conformity to language usage as derived by the grammar of a particular variety (linguistics), speech variety. The notion of grammaticality rose alongside the theory of generative grammar, the go ...

foundation of logic and rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

, since in his book on the elements of speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses Phonetics, phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if ...

, he distinguished the main parts of speech from the subordinate parts, and also direct expressions ( ) from metaphorical expressions, and dealt with the emotions ( ) of speech. He further distinguished a twofold reference of speech ( ) to things ( ) and to the hearers, and referred poetry and rhetoric to the latter.

He wrote at length on the unity of judgment, on the different kinds of negation, and on the difference between unconditional and conditional necessity. In his doctrine of syllogisms he brought forward the proof for the conversion of universal affirmative judgments, differed from Aristotle here and there in the laying down and arranging the ''modi'' of the syllogisms, partly in the proof of them, partly in the doctrine of mixture, i.e. of the influence of the modality of the premises upon the modality of the conclusion. Then, in two separate works, he dealt with the reduction of arguments to the syllogistic form and on the resolution of them; and further, with hypothetical conclusions. For the doctrine of proof

Proof most often refers to:

* Proof (truth), argument or sufficient evidence for the truth of a proposition

* Alcohol proof, a measure of an alcoholic drink's strength

Proof may also refer to:

Mathematics and formal logic

* Formal proof, a con ...

, Galen quotes the second ''Analytic'' of Theophrastus, in conjunction with that of Aristotle, as the best treatises on that doctrine. In different monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

s he seems to have tried to expand it into a general theory of science. To this, too, may have belonged the proposition quoted from his ''Topics'', that the ''principles of opposites'' are themselves opposed, and cannot be deduced from one and the same higher genus. For the rest, some minor deviations from the Aristotelian definitions are quoted from the ''Topica'' of Theophrastus. Closely connected with this treatise was that upon ambiguous words or ideas, which, without doubt, corresponded to book Ε of Aristotle's ''Metaphysics''.

Physics and metaphysics

Theophrastus introduced his Physics with the proof that all natural existence, being corporeal and composite, requires ''principles'', and first and foremost, motion, as the basis of all change. Denying the substance of space, he seems to have regarded it, in opposition to Aristotle, as the mere arrangement and position ( and ) of bodies. Time he called an accident of motion, without, it seems, viewing it, with Aristotle, as the numerical determinant of motion. He attacked the doctrine of the four classical elements and challenged whether fire could be called a primary element when it appears to be compound, requiring, as it does, another material for its own nutriment. He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only potentially exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:

He recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment () and contemplation to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit entirely independent of organic activity, must therefore have appeared to him very doubtful; yet he appears to have contented himself with developing his doubts and difficulties on the point, without positively rejecting it. Other Peripatetics, like Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and especially Strato, developed further this naturalism in Aristotelian doctrine.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his ''Metaphysics''. He was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:

He did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena. In antiquity, it was a subject of complaint that Theophrastus had not expressed himself with precision and consistency respecting God, and had understood it at one time as

He departed more widely from Aristotle in his doctrine of motion, since on the one hand he extended it over all categories, and did not limit it to those laid down by Aristotle. He viewed motion, with Aristotle, as an activity, not carrying its own goal in itself (), of that which only potentially exists, but he opposed Aristotle's view that motion required a special explanation, and he regarded it as something proper both to nature in general and the celestial system in particular:

He recognised no activity without motion, and so referred all activities of the soul to motion: the desires and emotions to corporeal motion, judgment () and contemplation to spiritual motion. The idea of a spirit entirely independent of organic activity, must therefore have appeared to him very doubtful; yet he appears to have contented himself with developing his doubts and difficulties on the point, without positively rejecting it. Other Peripatetics, like Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus, and especially Strato, developed further this naturalism in Aristotelian doctrine.

Theophrastus seems, generally speaking, where the investigation overstepped the limits of experience, to have preferred to develop the difficulties rather than solve them, as is especially apparent in his ''Metaphysics''. He was doubtful of Aristotle's teleology and recommended that such ideas be used with caution:

He did not follow the incessant attempts by Aristotle to refer phenomena to their ultimate foundations, or his attempts to unfold the internal connections between the latter, and between them and phenomena. In antiquity, it was a subject of complaint that Theophrastus had not expressed himself with precision and consistency respecting God, and had understood it at one time as Heaven

Heaven or the heavens, is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the belie ...

, at another an (enlivening) breath ('' pneuma'').

Ethics

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality. He subordinated moral requirements to the advantage at least of a friend, and had allowed in prosperity the existence of an influence injurious to them. In later times, fault was found with his expression in the ''Callisthenes'', "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom" ('). That in the definition of pleasure, likewise, he did not coincide with Aristotle, seems to be indicated by the titles of two of his writings, one of which dealt with pleasure generally, the other with pleasure as Aristotle had defined it. Although, like his teacher, he preferred contemplative (theoretical), to active (practical) life, he preferred to set the latter free from the restraints of family life, etc. in a manner of which Aristotle would not have approved.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.Taylor, Angus. ''Animals and Ethics''. Broadview Press, p. 35.

Theophrastus did not allow a happiness resting merely upon virtue, or, consequently, to hold fast by the unconditional value of morality. He subordinated moral requirements to the advantage at least of a friend, and had allowed in prosperity the existence of an influence injurious to them. In later times, fault was found with his expression in the ''Callisthenes'', "life is ruled by fortune, not wisdom" ('). That in the definition of pleasure, likewise, he did not coincide with Aristotle, seems to be indicated by the titles of two of his writings, one of which dealt with pleasure generally, the other with pleasure as Aristotle had defined it. Although, like his teacher, he preferred contemplative (theoretical), to active (practical) life, he preferred to set the latter free from the restraints of family life, etc. in a manner of which Aristotle would not have approved.

Theophrastus was opposed to eating meat on the grounds that it robbed animals of life and was therefore unjust. Non-human animals, he said, can reason, sense, and feel just as human beings do.Taylor, Angus. ''Animals and Ethics''. Broadview Press, p. 35.

The "portrait" of Theophrastus

The marble herm figure with the bearded head of philosopher type, bearing the explicit inscription, must be taken as purely conventional. Unidentified portrait heads did not find a ready market in post-Renaissance Rome. This bust was formerly in the collection of marchese Pietro Massimi at Palazzo Massimi and belonged to marchese L. Massimi at the time the engraving was made. It is now in the Villa Albani, Rome (inv. 1034). The inscribed bust has often been illustrated in engravings and photographs: a photograph of it forms the frontispiece to theLoeb Classical Library

The Loeb Classical Library (LCL; named after James Loeb; , ) is a series of books originally published by Heinemann in London, but is currently published by Harvard University Press. The library contains important works of ancient Greek and L ...

''Theophrastus: Enquiry into Plants'' vol. I, 1916. André Thevet illustrated in his iconographic compendium, (Paris, 1584), an alleged portrait plagiarized from the bust, supporting his fraud with the invented tale that he had obtained it from the library of a Greek in Cyprus and that he had seen a confirming bust in the ruins of Antioch.

In popular culture

A world is named Theophrastus in the 2014 ''Firefly'' graphic novel '' Serenity: Leaves on the Wind''. Theodor Geisel used the name "Theophrastus" as the given name of his pen-name alter ego, Dr. Seuss. A board game named Theophrastus was released in 2001. Players compete through a series of Alchemy experiments in order to become Theophrastus's apprentice.Works

*

*

* '' Metaphysics'' (or ''On First Principles'').

** Translated by M. van Raalte, 1993, Brill.

** ''On First Principles.'' Translated by Dimitri Gutas, 2010, Brill.

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 1-5.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916. Loeb Classical Library.

*

*

* '' Metaphysics'' (or ''On First Principles'').

** Translated by M. van Raalte, 1993, Brill.

** ''On First Principles.'' Translated by Dimitri Gutas, 2010, Brill.

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 1-5.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1916. Loeb Classical Library.Vol 1

�

Vol 2

* ''Enquiry into Plants: Books 6-9; Treatise on Odours; Concerning Weather Signs.'' Translated by A. F. Hort, 1926. Loeb Classical Library. ** * . Translated to French by Suzanne Amigues. Paris, Les Belles Lettres. 1988–2006. 5 tomes. Tome 1, Livres I-II. 1988. LVIII-146 p. Tome II, Livres III-IV. 1989. 306 p. Tome III, Livres V-VI. 1993. 212 p. Tome IV, Livres VII-VIII, 2003. 238 p. Tome V, Livres IX. 2006. LXX-400 p. First edition in French. Identifications are up-to-date, and carefully checked with botanists. Greek names with identifications are o

Pl@ntUse

* . Translated by B. Einarson and G. Link, 1989–1990. Loeb Classical Library. 3 volumes: , , .

*

Translated by R. C. Jebb

1870. *

Translated by J. M. Edmonds

1929, with parallel text. ** Translated by J. Rusten, 2003. Loeb Classical Library. * ''On Sweat, On Dizziness and On Fatigue.'' Translated by W. Fortenbaugh, R. Sharples, M. Sollenberger. Brill 2002. * ''On Weather Signs.'' *

Translated by J. G. Wood, G. J. Symons

1894. ** Edited by Sider David and Brunschön Carl Wolfram. Brill 2007. *

On Stones

'

Modern editions

* ''Theophrastus' Characters: An Ancient Take on Bad Behavior'' by James Romm (author), Pamela Mensch (translator), and André Carrilho (illustrator), Callaway Arts & Entertainment, 2018.Brill

ThInternational Theophrastus Project

started by

Brill Publishers

Brill Academic Publishers (known as E. J. Brill, Koninklijke Brill, Brill ()) is a Dutch international academic publisher founded in 1683 in Leiden, Netherlands. With offices in Leiden, Boston, Paderborn and Singapore, Brill today publishes 27 ...

in 1992.

* 1. ''Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence'' (two volumes), edited by William Fortenbaugh ''et al.'', Leiden: Brill, 1992.

** 1.1. ''Life, Writings, Various Reports, Logic, Physics, Metaphysics, Theology, Mathematics'' exts 1–264

** 1.2. ''Psychology, Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany, Ethics, Religion, Politics, Rhetoric and Poetics, Music, Miscellanea'' exts 265–741

* ff. 9 volumes are planned; the published volumes are:

** ''1. Theophrastus of Eresus: Sources for His Life, Writings, Thought and Influence — Commentary'', Leiden: Brill, 1994

** ''2. Logic'' exts 68–136 by Pamela Huby (2007); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas.

** ''3.1. Sources on Physics (Texts 137-223)'', by R. W. Sharples (1998).

** ''4. Psychology (Texts 265-327)'', by Pamela Huby (1999); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas.

** ''5. Sources on Biology (Human Physiology, Living Creatures, Botany: Texts 328-435''), by R. W. Sharples (1994).

** ''6.1. Sources on Ethics'' exts 436–579B by William W. Fortenbaugh; with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas (2011).

** ''8. Sources on Rhetoric and Poetics (Texts 666-713)'', by William W. Fortenbaugh (2005); with contributions on the Arabic material by Dimitri Gutas.

** ''9.1. Sources On Music (Texts 714-726C)'', by Massimo Raffa (2018).

** ''9.2. Sources on Discoveries and Beginnings, Proverbs et al. (Texts 727-741)'', by William W. Fortenbaugh (2014).

Explanatory notes

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Attribution: * *Further reading

* Baltussen, H. 2016. ''The Peripatetics: Aristotle's Heirs 322 BCE–200 CE.'' London: Routledge. * Fortenbaugh, W. W., and D. Gutas, eds. 1992. ''Theophrastus: His Psychological, Doxographical and Scientific Writings.'' Rutgers University Studies in Classical Humanities 5. New Brunswick, NJ, and London: Transaction Books. * Mejer, J. 1998. "A Life in Fragments: The Vita Theophrasti." In ''Theophrastus: Reappraising the Sources.'' Edited by J. van Ophuijsen and M. van Raalte, 1–28. Rutgers University Studies in Classical Humanities 8. New Brunswick, NJ, and London: Transaction Books. * Pertsinidis, S. 2018. ''Theophrastus' Characters: A new introduction.'' London: Routledge. * Van Raalte, M. 1993. ''Theophrastus' Metaphysics.'' Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill.External links

Works by Theophrastus at Perseus Digital Library

* * * * * —Contains a translation of ''On the Senses'' by Theophrastus. * *

Project ''Theophrastus''

Online Galleries, University of Oklahoma Libraries

Theophrastus of Eresus at the Edward Worth Library, Dublin

Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants, Hort's English translation of 1916

as html tagged with geolocated place references, a

ToposText

* * {{Authority control 370s BC births 280s BC deaths 4th-century BC Greek people 4th-century BC philosophers 4th-century BC writers 3rd-century BC Greek people 3rd-century BC philosophers 3rd-century BC writers Ancient Eresians Ancient Greek biologists Ancient Greek botanists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek logicians Ancient Greek metaphilosophers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek philosophers Ancient Greek philosophers of mind Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek science writers Cultural critics Ancient Greek epistemologists Moral philosophers Ontologists Peripatetic philosophers Philosophers of culture Philosophers of education Philosophers of ethics and morality Ancient Greek philosophers of language Philosophers of logic Philosophers of science Philosophy writers Pre-Linnaean botanists Social critics Social philosophers Virtue ethicists