Evidence of common descent of living

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s has been discovered by scientists researching in a variety of disciplines over many decades, demonstrating that

all life on Earth comes from a single ancestor. This forms an important part of the

evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, evidenc ...

on which evolutionary theory rests, demonstrates that

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

does occur, and illustrates the processes that created Earth's

biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

. It supports the

modern evolutionary synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

ŌĆöthe current

scientific theory

A scientific theory is an explanation of an aspect of the natural world and universe that has been repeatedly tested and corroborated in accordance with the scientific method, using accepted protocols of observation, measurement, and evaluatio ...

that explains how and why life changes over time. Evolutionary biologists document evidence of common descent, all the way back to the

last universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descentŌĆöthe most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; t ...

, by developing testable predictions, testing hypotheses, and constructing theories that illustrate and describe its causes.

Comparison of the

DNA genetic sequences of organisms has revealed that organisms that are

phylogenetically

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek ŽåŽģ╬╗╬«/ Žåß┐”╬╗╬┐╬Į [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé, ╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

close have a higher degree of DNA sequence similarity than organisms that are phylogenetically distant. Genetic fragments such as

pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Most arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either directly by DNA duplication or indirectly by Reverse transcriptase, reverse transcription of an mRNA trans ...

s, regions of

DNA that are

orthologous

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a spec ...

to a gene in a related

organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

, but are no longer active and appear to be undergoing a steady process of degeneration from cumulative mutations support common descent alongside the universal biochemical organization and molecular variance patterns found in all organisms. Additional genetic information conclusively supports the relatedness of life and has allowed scientists (since the discovery of DNA) to develop phylogenetic trees: a construction of organisms' evolutionary relatedness. It has also led to the development of

molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleoti ...

techniques to date taxon divergence times and to calibrate these with the fossil record.

Fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

are important for estimating when various lineages developed in

geologic time

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochrono ...

. As fossilization is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard body parts and death near a site where

sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

s are being deposited, the fossil record only provides sparse and intermittent information about the evolution of life. Evidence of organisms prior to the development of hard body parts such as shells, bones and teeth is especially scarce, but exists in the form of ancient

microfossil

A microfossil is a fossil that is generally between 0.001 mm and 1 mm in size, the visual study of which requires the use of light or electron microscopy. A fossil which can be studied with the naked eye or low-powered magnification, ...

s, as well as impressions of various soft-bodied organisms. The comparative study of the

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

of groups of animals shows structural features that are fundamentally similar (homologous), demonstrating phylogenetic and ancestral relationships with other organisms, most especially when compared with fossils of ancient

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

organisms.

Vestigial structures

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

and comparisons in

embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

are largely a contributing factor in anatomical resemblance in concordance with common descent. Since

metabolic

Metabolism (, from el, ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬▒╬▓╬┐╬╗╬« ''metabol─ō'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms'

physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

and

biochemistry

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

. Many lineages diverged at different stages of development, so it is possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor.

Evidence from

animal coloration

Animal coloration is the general appearance of an animal resulting from the reflection or emission of light from its surfaces. Some animals are brightly coloured, while others are hard to see. In some species, such as the peafowl, the male h ...

was gathered by some of Darwin's contemporaries;

camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the ...

,

mimicry

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. Often, mimicry f ...

, and

warning coloration

Aposematism is the advertising by an animal to potential predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defences which make the prey difficult to kill and eat, such as toxicity, venom, foul taste or ...

are all readily explained by

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. Special cases like the seasonal changes in the plumage of the

ptarmigan

''Lagopus'' is a small genus of birds in the grouse subfamily commonly known as ptarmigans (). The genus contains three living species with numerous described subspecies, all living in tundra or cold upland areas.

Taxonomy and etymology

The ge ...

, camouflaging it

against snow in winter and

against brown moorland in summer provide compelling evidence that selection is at work. Further evidence comes from the field of

biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

because evolution with common descent provides the best and most thorough explanation for a variety of facts concerning the geographical distribution of plants and animals across the world. This is especially obvious in the field of

insular biogeography Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern of ...

. Combined with the well-established geological theory of

plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, Žä╬Ą╬║Žä╬┐╬Į╬╣╬║ŽīŽé, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

, common descent provides a way to combine facts about the current distribution of species with evidence from the fossil record to provide a logically consistent explanation of how the distribution of living organisms has changed over time.

The development and spread of

antibiotic resistant

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. P ...

bacteria provides evidence that evolution due to natural selection is an ongoing process in the natural world. Natural selection is ubiquitous in all research pertaining to evolution, taking note of the fact that all of the following examples in each section of the article document the process. Alongside this are observed instances of the separation of populations of species into sets of new species (

speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

). Speciation has been

observed in the lab and in nature. Multiple forms of such have been described and documented as examples for individual modes of speciation. Furthermore, evidence of common descent extends from direct laboratory experimentation with the

selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

of organismsŌĆöhistorically and currentlyŌĆöand other controlled experiments involving many of the topics in the article. This article summarizes the varying disciplines that provide the evidence for evolution and the common descent of all life on Earth, accompanied by numerous and specialized examples, indicating a compelling

consilience of evidence.

Evidence from comparative physiology and biochemistry

Genetics

One of the strongest evidences for common descent comes from gene sequences.

Comparative sequence analysis examines the relationship between the DNA sequences of different species,

producing several lines of evidence that confirm Darwin's original hypothesis of common descent. If the hypothesis of common descent is true, then species that share a common ancestor inherited that ancestor's DNA sequence, as well as mutations unique to that ancestor. More closely related species have a greater fraction of identical sequence and shared substitutions compared to more distantly related species.

The simplest and most powerful evidence is provided by

phylogenetic reconstruction. Such reconstructions, especially when done using slowly evolving protein sequences, are often quite robust and can be used to reconstruct a great deal of the evolutionary history of modern organisms (and even in some instances of the evolutionary history of extinct organisms, such as the recovered gene sequences of

mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

s or

Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

s). These reconstructed phylogenies recapitulate the relationships established through morphological and biochemical studies.

The most detailed reconstructions have been performed on the basis of the mitochondrial genomes shared by all

eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organisms, which are short and easy to sequence; the broadest reconstructions have been performed either using the sequences of a few very ancient proteins or by using

ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

sequence.

Phylogenetic relationships extend to a wide variety of nonfunctional sequence elements, including repeats,

transposon

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transpo ...

s,

pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Most arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either directly by DNA duplication or indirectly by Reverse transcriptase, reverse transcription of an mRNA trans ...

s, and

mutations in protein-coding sequences that do not change the amino-acid sequence. While a minority of these elements might later be found to harbor function, in aggregate they demonstrate that identity must be the product of common descent rather than common function.

Universal biochemical organisation and molecular variance patterns

All known

extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

(surviving) organisms are based on the same biochemical processes: genetic information encoded as nucleic acid (

DNA, or

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

for many viruses), transcribed into

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, then translated into

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s (that is, polymers of

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s) by highly conserved

ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s. Perhaps most tellingly, the

Genetic Code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

(the "translation table" between DNA and amino acids) is the same for almost every organism, meaning that a piece of

DNA in a

bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

codes for the same amino acid as in a human

cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

.

ATP

ATP may refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Association of Tennis Professionals, men's professional tennis governing body

* American Technical Publishers, employee-owned publishing company

* ', a Danish pension

* Armenia Tree Project, non ...

is used as energy currency by all extant life. A deeper understanding of

developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

shows that common morphology is, in fact, the product of shared genetic elements. For example, although camera-like eyes are believed to have evolved independently on many separate occasions, they share a common set of light-sensing proteins (

opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become Retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most pro ...

s), suggesting a common point of origin for all sighted creatures. Another example is the familiar vertebrate body plan, whose structure is controlled by the

homeobox (Hox) family of genes.

DNA sequencing

Comparison of DNA sequences allows organisms to be grouped by sequence similarity, and the resulting

phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek ŽåŽģ╬╗╬«/ Žåß┐”╬╗╬┐╬Į [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé, ╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

trees are typically congruent with traditional

taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, and are often used to strengthen or correct taxonomic classifications. Sequence comparison is considered a measure robust enough to correct erroneous assumptions in the phylogenetic tree in instances where other evidence is scarce. For example, neutral human DNA sequences are approximately 1.2% divergent (based on substitutions) from those of their nearest genetic relative, the

chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

, 1.6% from

gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s, and 6.6% from

baboon

Baboons are primates comprising the genus ''Papio'', one of the 23 genera of Old World monkeys. There are six species of baboon: the hamadryas baboon, the Guinea baboon, the olive baboon, the yellow baboon, the Kinda baboon and the chacma ba ...

s. Genetic sequence evidence thus allows inference and quantification of genetic relatedness between humans and other

ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and as well as Europe in prehistory), which together with its siste ...

s. The sequence of the

16S ribosomal RNA

16 S ribosomal RNA (or 16 S rRNA) is the RNA component of the 30S subunit of a prokaryotic ribosome (SSU rRNA). It binds to the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and provides most of the SSU structure.

The genes coding for it are referred to as 16S rRNA ...

gene, a vital gene encoding a part of the

ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

, was used to find the broad phylogenetic relationships between all extant life. The analysis by

Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 ŌĆō December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

resulted in the

three-domain system

The three-domain system is a biological classification introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis in 1990 that divides cellular life forms into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota or Eukarya. The key difference fr ...

, arguing for two major splits in the early evolution of life. The first split led to modern

Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and the subsequent split led to modern

Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

and

Eukaryotes

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

.

Some DNA sequences are shared by very different organisms. It has been predicted by the theory of evolution that the differences in such DNA sequences between two organisms should roughly resemble both the biological difference between them according to their

anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

and the time that had passed since these two organisms have separated in the course of evolution, as seen in

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

evidence. The rate of accumulating such changes should be low for some sequences, namely those that code for critical

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

or

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, and high for others that code for less critical RNA or proteins; but for every specific sequence, the rate of change should be roughly constant over time. These results have been experimentally confirmed. Two examples are DNA sequences coding for

rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosoma ...

, which is highly conserved, and DNA sequences coding for

fibrinopeptide

The fibrinopeptides, fibrinopeptide A (FpA) and fibrinopeptide B (FpB), are peptides which are located in the central region of the fibrous glycoprotein fibrinogen (factor I) and are cleaved by the enzyme thrombin (factor IIa) to convert fibrin ...

s,

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

chains discarded during the formation of

fibrin

Fibrin (also called Factor Ia) is a fibrous, non-globular protein involved in the clotting of blood. It is formed by the action of the protease thrombin on fibrinogen, which causes it to polymerize. The polymerized fibrin, together with platele ...

, which are highly non-conserved.

Proteins

Proteomic

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Proteins are vital parts of living organisms, with many functions such as the formation of structural fibers of muscle tissue, enzymatic digestion of food, or synthesis and replication of DNA. In ...

evidence also supports the universal ancestry of life. Vital

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, such as the

ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

,

DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

, and

RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

, are found in everything from the most primitive bacteria to the most complex mammals. The core part of the protein is conserved across all lineages of life, serving similar functions. Higher organisms have evolved additional

protein subunit

In structural biology, a protein subunit is a polypeptide chain or single protein molecule that assembles (or "''coassembles''") with others to form a protein complex.

Large assemblies of proteins such as viruses often use a small number of ty ...

s, largely affecting the regulation and

protein-protein interaction of the core. Other overarching similarities between all lineages of extant organisms, such as

DNA,

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, amino acids, and the

lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

, give support to the theory of common descent. Phylogenetic analyses of protein sequences from various organisms produce similar trees of relationship between all organisms. The

chirality

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from ...

of DNA, RNA, and amino acids is conserved across all known life. As there is no functional advantage to right- or left-handed molecular chirality, the simplest hypothesis is that the choice was made randomly by early organisms and passed on to all extant life through common descent. Further evidence for reconstructing ancestral lineages comes from

junk DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not genetic code, encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is Transcription (genetics), transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, micro ...

such as

pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Most arise as superfluous copies of functional genes, either directly by DNA duplication or indirectly by Reverse transcriptase, reverse transcription of an mRNA trans ...

s, "dead" genes that steadily accumulate mutations.

Pseudogenes

Pseudogenes, also known as

noncoding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and regul ...

, are extra DNA in a genome that do not get transcribed into RNA to synthesize proteins. Some of this noncoding DNA has known functions, but much of it has no known function and is called "Junk DNA".

This is an example of a vestige since replicating these genes uses energy, making it a waste in many cases. A pseudogene can be produced when a coding gene accumulates mutations that prevent it from being transcribed, making it non-functional.

But since it is not transcribed, it may disappear without affecting fitness, unless it has provided some beneficial function as non-coding DNA. Non-functional pseudogenes may be passed on to later species, thereby labeling the later species as descended from the earlier species.

Other mechanisms

A large body of molecular evidence supports a variety of mechanisms for large evolutionary changes, including:

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

and

gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

, which facilitates rapid evolution by providing substantial quantities of genetic material under weak or no selective constraints;

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

, the process of transferring genetic material to another cell that is not an organism's offspring, allowing for species to acquire beneficial genes from each other; and

recombination, capable of reassorting large numbers of different

allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ß╝ä╬╗╬╗╬┐Žé ''├Īllos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s and of establishing

reproductive isolation

The mechanisms of reproductive isolation are a collection of evolutionary mechanisms, behaviors and physiological processes critical for speciation. They prevent members of different species from producing offspring, or ensure that any offspring ...

. The

endosymbiotic theory

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibl ...

explains the origin of

mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

and

plastid

The plastid (Greek: ŽĆ╬╗╬▒ŽāŽäŽīŽé; plast├│s: formed, molded ŌĆō plural plastids) is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. They are considered to be intracellular endosy ...

s (including

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s), which are

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s of eukaryotic cells, as the incorporation of an ancient

prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:ŽĆŽüŽī#Ancient Greek, ŽĆŽüŽī (, 'before') a ...

cell into ancient

eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

cell. Rather than evolving

eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s slowly, this theory offers a mechanism for a sudden evolutionary leap by incorporating the genetic material and biochemical composition of a separate species. Evidence supporting this mechanism has been found in the

protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

''

Hatena'': as a

predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

it engulfs a

green alga

The green algae (singular: green alga) are a group consisting of the Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister which contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/Streptophyta. The land plants (Embryophytes) have emerged deep in the Charophyte alga as ...

l cell, which subsequently behaves as an

endosymbiont

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ß╝ö╬Į╬┤╬┐╬Į ''endon'' "within" ...

, nourishing ''Hatena'', which in turn loses its feeding apparatus and behaves as an

autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

.

Since

metabolic

Metabolism (, from el, ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬▒╬▓╬┐╬╗╬« ''metabol─ō'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms. Many lineages diverged when new metabolic processes appeared, and it is theoretically possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor or by detecting their physical manifestations. As an example, the appearance of

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

in the

earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

is linked to the evolution of

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

.

Specific examples from comparative physiology and biochemistry

Chromosome 2 in humans

Evidence for the evolution of ''

Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' from a common ancestor with chimpanzees is found in the number of chromosomes in humans as compared to all other members of

Hominidae

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ea ...

. All hominidae have 24 pairs of chromosomes, except humans, who have only 23 pairs. Human chromosome 2 is a result of an end-to-end fusion of two ancestral chromosomes.

[MacAndrew, Alec]

Human Chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral chromosomes

Accessed 18 May 2006.

The evidence for this includes:

* The correspondence of chromosome 2 to two ape chromosomes. The closest human relative, the

chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

, has near-identical DNA sequences to human chromosome 2, but they are found in two separate chromosomes. The same is true of the more distant

gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

and

orangutan

Orangutans are great apes native to the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They are now found only in parts of Borneo and Sumatra, but during the Pleistocene they ranged throughout Southeast Asia and South China. Classified in the genus ...

.

[Human and Ape Chromosomes](_blank)

; accessed 8 September 2007.

* The presence of a

vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers a ...

. Normally a chromosome has just one centromere, but in chromosome 2 there are remnants of a second centromere.

* The presence of vestigial

telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mos ...

s. These are normally found only at the ends of a chromosome, but in chromosome 2 there are additional telomere sequences in the middle.

Chromosome 2 thus presents strong evidence in favour of the common descent of humans and other

ape

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and as well as Europe in prehistory), which together with its siste ...

s. According to J. W. Ijdo, "We conclude that the locus cloned in cosmids c8.1 and c29B is the relic of an ancient telomere-telomere fusion and marks the point at which two ancestral ape chromosomes fused to give rise to human chromosome 2."

Cytochrome c and b

A classic example of biochemical evidence for evolution is the variance of the ubiquitous (i.e. all living organisms have it, because it performs very basic life functions)

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

Cytochrome c

The cytochrome complex, or cyt ''c'', is a small hemeprotein found loosely associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. It belongs to the cytochrome c family of proteins and plays a major role in cell apoptosis. Cytochrome c is hig ...

in living cells. The variance of cytochrome c of different organisms is measured in the number of differing amino acids, each differing amino acid being a result of a

base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

substitution, a

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

. If each differing amino acid is assumed the result of one base pair substitution, it can be calculated how long ago the two species diverged by multiplying the number of base pair substitutions by the estimated time it takes for a substituted base pair of the cytochrome c gene to be successfully passed on. For example, if the average time it takes for a base pair of the cytochrome c gene to mutate is N years, the number of amino acids making up the cytochrome c protein in monkeys differ by one from that of humans, this leads to the conclusion that the two species diverged N years ago.

The primary structure of cytochrome c consists of a chain of about 100

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. Many higher order organisms possess a chain of 104 amino acids.

[Amino acid sequences in cytochrome c proteins from different species](_blank)

adapted from Strahler, Arthur; Science and Earth History, 1997. page 348.

The cytochrome c molecule has been extensively studied for the glimpse it gives into evolutionary biology. Both

chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster or cock is a term for an adult m ...

and

turkey

Turkey ( tr, T├╝rkiye ), officially the Republic of T├╝rkiye ( tr, T├╝rkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

s have identical sequence homology (amino acid for amino acid), as do

pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus s ...

s,

cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

s and

sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

. Both humans and chimpanzees share the identical molecule, while

rhesus monkey

The rhesus macaque (''Macaca mulatta''), colloquially rhesus monkey, is a species of Old World monkey. There are between six and nine recognised subspecies that are split between two groups, the Chinese-derived and the Indian-derived. Generally b ...

s share all but one of the amino acids: the 66th amino acid is

isoleucine

Isoleucine (symbol Ile or I) is an ╬▒-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an ╬▒-amino group (which is in the protonated ŌłÆNH form under biological conditions), an ╬▒-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprot ...

in the former and

threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an ╬▒-amino group (which is in the protonated ŌłÆNH form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated ŌłÆCOOŌ ...

in the latter.

What makes these homologous similarities particularly suggestive of common ancestry in the case of cytochrome c, in addition to the fact that the phylogenies derived from them match other phylogenies very well, is the high degree of functional redundancy of the cytochrome c molecule. The different existing configurations of amino acids do not significantly affect the functionality of the protein, which indicates that the base pair substitutions are not part of a directed design, but the result of random mutations that are not subject to selection.

In addition, Cytochrome b is commonly used as a region of

mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

to determine

phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek ŽåŽģ╬╗╬«/ Žåß┐”╬╗╬┐╬Į [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé, ╬│╬Ą╬Į╬ĄŽä╬╣╬║ŽīŽé [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

relationships between organisms due to its sequence variability. It is considered most useful in determining relationships within

families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

and

genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

. Comparative studies involving cytochrome b have resulted in new classification schemes and have been used to assign newly described species to a genus, as well as deepen the understanding of evolutionary relationships.

Endogenous retroviruses

Endogenous retrovirus

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are endogenous viral elements in the genome that closely resemble and can be derived from retroviruses. They are abundant in the genomes of jawed vertebrates, and they comprise up to 5ŌĆō8% of the human genome (l ...

es (or ERVs) are remnant sequences in the genome left from ancient viral infections in an organism. The retroviruses (or virogenes) are always

passed on to the next generation of that organism that received the infection. This leaves the virogene left in the genome. Because this event is rare and random, finding identical chromosomal positions of a virogene in two different species suggests common ancestry.

Cats (

Felidae

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the ...

) present a notable instance of virogene sequences demonstrating common descent. The standard phylogenetic tree for Felidae have smaller cats (''

Felis chaus

The jungle cat (''Felis chaus''), also called reed cat, swamp cat and jungle lynx, is a medium-sized cat native to the Middle East, the Caucasus, South and Southeast Asia and southern China. It inhabits foremost wetlands like swamps, littoral a ...

'', ''

Felis silvestris

The European wildcat (''Felis silvestris'') is a small wildcat species native to continental Europe, Scotland, Turkey and the Caucasus. It inhabits forests from the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, Central and Eastern Europe to the Caucasus. Its fur is ...

'', ''

Felis nigripes'', and ''

Felis catus

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of t ...

'') diverging from larger cats such as the subfamily

Pantherinae

Pantherinae is a subfamily within the family Felidae; it was named and first described by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1917 as only including the ''Panthera'' species. The Pantherinae genetically diverged from a common ancestor between and .

Char ...

and other

carnivores

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

. The fact that small cats have an ERV where the larger cats do not suggests that the gene was inserted into the ancestor of the small cats after the larger cats had diverged. Another example of this is with humans and chimps. Humans contain numerous ERVs that comprise a considerable percentage of the genome. Sources vary, but 1% to 8% has been proposed. Humans and chimps share seven different occurrences of virogenes, while all primates share similar retroviruses congruent with phylogeny.

Recent African origin of modern humans

Mathematical models of evolution, pioneered by the likes of

Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright FRS(For) Honorary FRSE (December 21, 1889March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. He was a founder of population genetics alongsi ...

,

Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 ŌĆō 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

and

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

and extended via

diffusion theory Photon transport in biological tissue can be equivalently modeled numerically with Monte Carlo simulations or analytically by the radiative transfer equation (RTE). However, the RTE is difficult to solve without introducing approximations. A common ...

by

Motoo Kimura

(November 13, 1924 ŌĆō November 13, 1994) was a Japanese biologist best known for introducing the neutral theory of molecular evolution in 1968. He became one of the most influential theoretical population geneticists. He is remembered in geneti ...

, allow predictions about the genetic structure of evolving populations. Direct examination of the genetic structure of modern populations via DNA sequencing has allowed verification of many of these predictions. For example, the

Out of Africa

''Out of Africa'' is a memoir by the Danish people, Danish author Karen Blixen. The book, first published in 1937, recounts events of the seventeen years when Blixen made her home in Kenya, then called East Africa Protectorate, British East Afr ...

theory of human origins, which states that modern humans developed in Africa and a small sub-population migrated out (undergoing a

population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

), implies that modern populations should show the signatures of this migration pattern. Specifically, post-bottleneck populations (Europeans and Asians) should show lower overall genetic diversity and a more uniform distribution of allele frequencies compared to the African population. Both of these predictions are borne out by actual data from a number of studies.

Evidence from comparative anatomy

Comparative study of the anatomy of groups of animals or plants reveals that certain structural features are basically similar. For example, the basic structure of all

flower

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechani ...

s consists of

sepal

A sepal () is a part of the flower of angiosperms (flowering plants). Usually green, sepals typically function as protection for the flower in bud, and often as support for the petals when in bloom., p. 106 The term ''sepalum'' was coined b ...

s,

petal

Petals are modified Leaf, leaves that surround the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often advertising coloration, brightly colored or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. All of the petals of a flower are collectively known as the ''c ...

s,

stigma, style and ovary; yet the size,

colour

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associ ...

,

number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers c ...

of parts and specific structure are different for each individual species. The neural anatomy of fossilized remains may also be compared using advanced imaging techniques.

Atavisms

Once thought of as a refutation to evolutionary theory, atavisms are "now seen as potent evidence of how much genetic potential is retained...after a particular structure has disappeared from a species".

"Atavisms are the reappearance of a lost character typical of remote ancestors and not seen in the parents or recent ancestors..."

and are an "

ndicationof the developmental plasticity that exists within embryos..."

Atavisms occur because genes for previously existing phenotypical features are often preserved in DNA, even though the genes are not expressed in some or most of the organisms possessing them. Numerous examples have documented the occurrence of atavisms alongside experimental research triggering their formation. Due to the complexity and interrelatedness of the factors involved in the development of atavisms, both biologists and medical professionals find it "difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish

hem

A hem in sewing is a garment finishing method, where the edge of a piece of cloth is folded and sewn to prevent unravelling of the fabric and to adjust the length of the piece in garments, such as at the end of the sleeve or the bottom of the ga ...

from malformations."

Some examples of atavisms found in the scientific literature include:

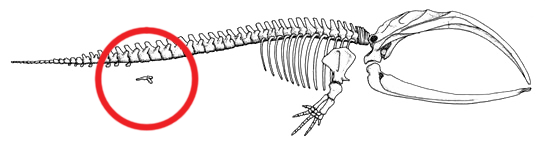

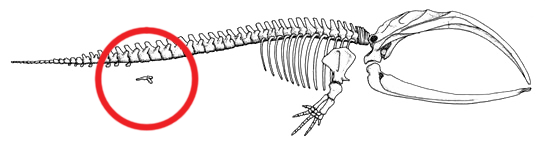

*Hind limbs in

whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s.

(see figure 2a)

*Reappearance of limbs in

limbless vertebrate

Many vertebrates have evolved limbless, limb-reduced, or apodous forms. Reptiles have on a number of occasions evolved into limbless forms ŌĆō snakes, amphisbaenia, and legless lizards (limb loss in lizards has evolved independently several time ...

s.

*Back pair of flippers on a

bottlenose dolphin

Bottlenose dolphins are aquatic mammals in the genus ''Tursiops.'' They are common, cosmopolitan members of the family Delphinidae, the family of oceanic dolphins. Molecular studies show the genus definitively contains two species: the common ...

.

*Extra toes of the modern horse.

*

Human tails (not pseudo-tails)

and extra nipples in humans.

*Re-evolution of sexuality from parthenogenesis in

orbitid mites.

*Teeth in chickens.

*

Dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit ŌĆō vestigial in some animals ŌĆō on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

s in dogs.

*Reappearance of wings on wingless stick insects and earwigs.

*Atavistic muscles in several birds

and mammals such as the

beagle

The beagle is a breed of small scent hound, similar in appearance to the much larger foxhound. The beagle was developed primarily for hunting hare, known as beagling. Possessing a great sense of smell and superior tracking instincts, the ...

and the

jerboa

Jerboas (from ar, ž¼ž▒ž©┘łž╣ ') are hopping desert rodents found throughout North Africa and Asia, and are members of the family Dipodidae. They tend to live in hot deserts.

When chased, jerboas can run at up to . Some species are preyed on b ...

.

*Extra toes in

guinea pigs

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy (), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'' in the family Caviidae. Breeders tend to use the word ''cavy'' to describe the ani ...

.

Evolutionary developmental biology and embryonic development

Evolutionary developmental biology is the biological field that compares the developmental process of different organisms to determine ancestral relationships between species. A large variety of organism's genomes contain a

small fraction of genes that control the organisms development.

Hox genes

Hox genes, a subset of homeobox genes, are a group of related genes that specify regions of the body plan of an embryo along the head-tail axis of animals. Hox proteins encode and specify the characteristics of 'position', ensuring that the cor ...

are an example of these types of nearly universal genes in organisms pointing to an origin of common ancestry. Embryological evidence comes from the development of organisms at the embryological level with the comparison of different organisms embryos similarity. Remains of ancestral traits often appear and disappear in different stages of the embryological development process.

Some examples include:

* Hair growth and loss (

lanugo

Lanugo is very thin, soft, usually unpigmented, downy hair that is sometimes found on the body of a fetus or newborn. It is the first hair to be produced by the fetal hair follicles, and it usually appears around sixteen weeks of gestation and is ...

) during human development.

* Development and degeneration of a

yolk sac

The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though ''yolk sac'' is far ...

.

* Terrestrial frogs and

salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All ten ...

s passing through the larval stage within the eggŌĆöwith features of typically aquatic larvaeŌĆöbut hatch ready for life on land;

* The appearance of gill-like structures (

pharyngeal arch

The pharyngeal arches, also known as visceral arches'','' are structures seen in the embryonic development of vertebrates that are recognisable precursors for many structures. In fish, the arches are known as the branchial arches, or gill arch ...

) in vertebrate embryo development. Note that in fish, the arches continue to develop as

branchial arch

Branchial arches, or gill arches, are a series of bony "loops" present in fish, which support the gills. As gills are the primitive condition of vertebrates, all vertebrate embryos develop pharyngeal arches, though the eventual fate of these arc ...

es while in humans, for example, they give rise to a

variety of structures within the head and neck.

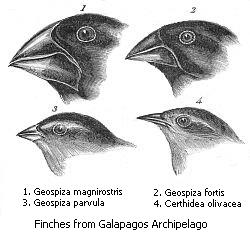

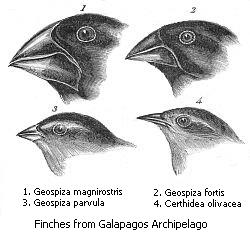

Homologous structures and divergent (adaptive) evolution

If widely separated groups of organisms are originated from a common ancestry, they are expected to have certain basic features in common. The degree of resemblance between two organisms should indicate how closely related they are in evolution:

* Groups with little in common are assumed to have diverged from a

common ancestor

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

much earlier in geological history than groups with a lot in common;

* In deciding how closely related two animals are, a comparative anatomist looks for

structure

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

s that are fundamentally similar, even though they may serve different functions in the

adult

An adult is a human or other animal that has reached full growth. In human context, the term ''adult'' has meanings associated with social and legal concepts. In contrast to a " minor", a legal adult is a person who has attained the age of major ...

. Such structures are described as

homologous and suggest a common origin.

* In cases where the similar structures serve different functions in adults, it may be necessary to trace their origin and

embryonic development

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sperm ...

. A similar developmental origin suggests they are the same structure, and thus likely derived from a common ancestor.

When a group of organisms share a homologous structure that is specialized to perform a variety of functions to adapt different environmental conditions and modes of life, it is called

adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

. The gradual spreading of organisms with adaptive radiation is known as

divergent evolution

Divergent evolution or divergent selection is the accumulation of differences between closely related populations within a species, leading to speciation. Divergent evolution is typically exhibited when two populations become separated by a geog ...

.

Nested hierarchies and classification

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

is based on the fact that all organisms are related to each other in nested hierarchies based on shared characteristics. Most existing species can be organized rather easily in a nested

hierarchical classification

Hierarchical classification is a system of grouping things according to a hierarchy.

In the field of machine learning, hierarchical classification is sometimes referred to as instance space decomposition, which splits a complete multi-class pro ...

. This is evident from the Linnaean classification scheme. Based on shared derived characters, closely related organisms can be placed in one group (such as a genus), several genera can be grouped together into one family, several families can be grouped together into an order, etc.

[29+ Evidences for Macroevolution: Part 1](_blank)

Talkorigins.org. Retrieved on 6 December 2011. The existence of these nested hierarchies was recognized by many biologists before Darwin, but he showed that his theory of evolution with its branching pattern of common descent could explain them.

Darwin described how common descent could provide a logical basis for classification:

Evolutionary trees

An

evolutionary tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

(of Amniota, for example, the last common ancestor of mammals and reptiles, and all its descendants) illustrates the initial conditions causing evolutionary patterns of similarity (e.g., all Amniotes produce an egg that possesses the

amnios) and the patterns of divergence amongst lineages (e.g., mammals and reptiles branching from the common ancestry in Amniota). Evolutionary trees provide conceptual models of evolving systems once thought limited in the domain of making predictions out of the theory.

However, the method of

phylogenetic bracketing

Phylogenetic bracketing is a method of inference used in biological sciences. It is used to infer the likelihood of unknown traits in organisms based on their position in a phylogenetic tree. One of the main applications of phylogenetic bracketing ...

is used to infer predictions with far greater probability than raw speculation. For example, paleontologists use this technique to make predictions about nonpreservable traits in fossil organisms, such as feathered dinosaurs, and molecular biologists use the technique to posit predictions about RNA metabolism and protein functions.

Thus evolutionary trees are evolutionary hypotheses that refer to specific facts, such as the characteristics of organisms (e.g., scales, feathers, fur), providing evidence for the patterns of descent, and a causal explanation for modification (i.e., natural selection or neutral drift) in any given lineage (e.g., Amniota). Evolutionary biologists test evolutionary theory using phylogenetic systematic methods that measure how much the hypothesis (a particular branching pattern in an evolutionary tree) increases the likelihood of the evidence (the distribution of characters among lineages). The severity of tests for a theory increases if the predictions "are the least probable of being observed if the causal event did not occur." "Testability is a measure of how much the hypothesis increases the likelihood of the evidence."

Vestigial structures

Evidence for common descent comes from the existence of vestigial structures.

These rudimentary structures are often homologous to structures that correspond in related or ancestral species. A wide range of structures exist such as mutated and non-functioning genes, parts of a flower, muscles, organs, and even behaviors. This variety can be found across many different groups of species. In many cases they are degenerated or underdeveloped. The existence of vestigial organs can be explained in terms of changes in the environment or modes of life of the species. Those organs are typically functional in the ancestral species but are now either semi-functional, nonfunctional, or re-purposed.

Scientific literature concerning vestigial structures abounds. One study compiled 64 examples of vestigial structures found in the literature across a wide range of disciplines within the 21st century. The following non-exhaustive list summarizes Senter et al. alongside various other examples:

* The presence of remnant

mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

(

mitosomes

A mitosome is an organelle found in some unicellular eukaryotic organisms, like in members of the supergroup Excavata. The mitosome was found and named in 1999, and its function has not yet been well characterized. It was termed a ''crypton'' by o ...

) that have lost the ability to synthesize

ATP

ATP may refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Association of Tennis Professionals, men's professional tennis governing body

* American Technical Publishers, employee-owned publishing company

* ', a Danish pension

* Armenia Tree Project, non ...

in ''

Entamoeba histolytica

''Entamoeba histolytica'' is an anaerobic parasitic amoebozoan, part of the genus ''Entamoeba''. Predominantly infecting humans and other primates causing amoebiasis, ''E. histolytica'' is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people worldwid ...

,

Trachipleistophora hominis,

Cryptosporidium parvum

''Cryptosporidium parvum'' is one of several species that cause cryptosporidiosis, a parasitic disease of the mammalian intestinal tract.

Primary symptoms of ''C. parvum'' infection are acute, watery, and nonbloody diarrhea. ''C. parvum'' infect ...

,

Blastocystis hominis

''Blastocystis'' is a genus of single-celled heterokont parasites belonging to a group of organisms that are known as the Stramenopiles (also called Heterokonts) that includes algae, diatoms, and water molds. Blastocystis consists of several ...

'', and ''

Giardia intestinalis

''Giardia duodenalis'', also known as ''Giardia intestinalis'' and ''Giardia lamblia'', is a flagellated parasitic microorganism of the genus ''Giardia'' that colonizes the small intestine, causing a diarrheal condition known as giardiasis. The ...

''.

* Remnant

chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

organelles (

leucoplasts) in non-photosynthetic algae species (''

Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a Unicellular organism, unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female ''Anopheles'' mosqu ...

'', ''

Toxoplasma gondii