In

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, many governments, organizations and individuals

collaborated

Collaboration (from Latin ''com-'' "with" + ''laborare'' "to labor", "to work") is the process of two or more people, entities or organizations working together to complete a task or achieve a goal. Collaboration is similar to cooperation. The f ...

with the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

, "out of conviction, desperation, or under coercion".

Nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

s sometimes welcomed German or Italian troops they believed would liberate their countries from colonization. The Danish, Belgian and Vichy French governments attempted to appease and bargain with the invaders in hopes of mitigating harm to their citizens and economies.

Some countries' leaders such as

Henrik Werth of Axis member Hungary, cooperated with Italy and Germany because they wanted to regain territories lost during and after

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, or which their nationalist citizens simply coveted. Others such as France already had their own burgeoning fascist movements and/or

antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

sentiment, which the invaders validated and empowered. Individuals such as

Hendrik Seyffardt in the Netherlands and

Theodoros Pangalos

Theodoros Pangalos (, romanized: ''Theódoros Pángalos''; 11 January 1878 – 26 February 1952) was a Greek general, politician and dictator. A distinguished staff officer and an ardent Venizelist and anti-royalist, Pangalos played a leading r ...

in Greece saw collaboration as a path to personal power in the politics of their country. Others believed that Germany would prevail, and wanted to be on the winning side or feared being on the losing one.

Axis military forces recruited many volunteers, sometimes at gunpoint, more often with promises that they later broke, or from among POWs trying to escape appalling and frequently lethal conditions in their detention camps. Other volunteers willingly enlisted because they shared Nazi or fascist ideologies.

Terminology

Stanley Hoffmann

Stanley Hoffmann (27 November 1928 – 13 September 2015) was a French political scientist and the Paul and Catherine Buttenwieser University Professor at Harvard University, specializing in French politics and society, European politics, U.S ...

in 1968 used the term ''collaborationist'' to describe those who collaborated for ideological reasons.

Bertram Gordon, a professor of modern history, also used the terms ''collaborationist'' and ''collaborator'' for

ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

and non-ideological collaboration. ''Collaboration'' described cooperation, sometimes passive, with a victorious power.

Hoffmann saw collaboration as either involuntary, a reluctant recognition of necessity, or voluntary,

opportunistic

300px, ''Opportunity Seized, Opportunity Missed'', engraving by Theodoor Galle, 1605

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances — with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opport ...

, or greedy. He also categorized collaborationism as "servile", attempting to be useful, or "ideological", full-throated advocacy of the occupier's ideology.

Collaboration in Western Europe

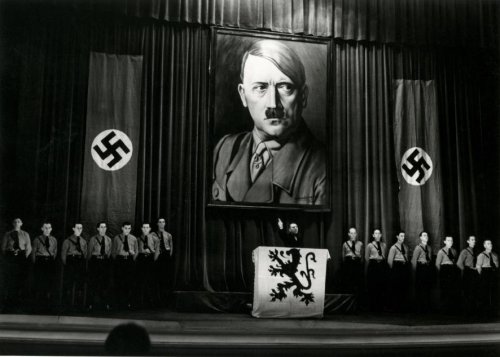

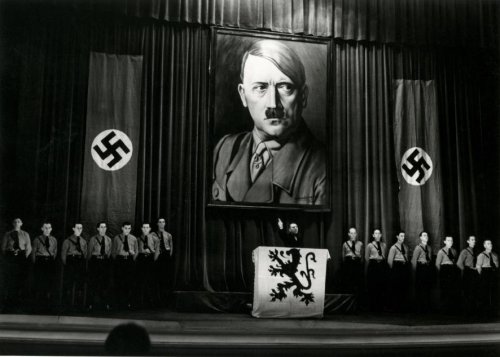

Belgium

Belgium was

invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940 and

occupied until the end of 1944.

Political collaboration took separate forms across the

Belgian language divide. In Dutch-speaking

Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, the

Vlaamsch Nationaal Verbond

The (, "Flemish National Union" or "Flemish National League"), widely known by its acronym VNV, was a Flemish nationalist political party active in Belgium between 1933 and 1945. (Flemish National Union or VNV), clearly authoritarian, anti-democratic and influenced by fascist ideas,

[B. De Wever]

Vlaams Nationaal Verbond (VNV)

at Belgium-WWII, ("Au sein de la direction du parti, on retrouve deux tendances: une aile fasciste et une aile modérée.") became a major player in the German occupation strategy as part of the pre-war

Flemish Movement

The Flemish Movement (, ) is an umbrella term which encompasses various political groups in the Belgium, Belgian region of Flanders and, less commonly, in French Flanders. Ideologically, it encompasses groups which have sought to promote Flemis ...

. VNV politicians were promoted to positions in the Belgian civil administration. VNV and its comparatively moderate stance was increasingly eclipsed later in the war by the more radical and pro-German

DeVlag movement.

In French-speaking

Wallonia

Wallonia ( ; ; or ), officially the Walloon Region ( ; ), is one of the three communities, regions and language areas of Belgium, regions of Belgium—along with Flemish Region, Flanders and Brussels. Covering the southern portion of the c ...

,

Léon Degrelle

Léon Joseph Marie Ignace Degrelle (; 15 June 1906 – 31 March 1994) was a Belgian Walloon politician and Nazi collaborator. He rose to prominence in Belgium in the 1930s as the leader of the Rexist Party (Rex). During the German occupatio ...

's

Rexist Party, a pre-war authoritarian and

Catholic Fascist political party,

became the VNV's Walloon equivalent, although Rex's

Belgian nationalism

Belgian nationalism, sometimes pejoratively referred to as Belgicism (; ), is a nationalism, nationalist ideology. In its modern form it favours the reversal of federalism and the creation of a unitary state in Belgium. The ideology advocates r ...

put it at odds with the Flemish nationalism of VNV and the German ''

Flamenpolitik''. Rex became increasingly radical after 1941 and declared itself part of the ''

Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

''.

Although the

pre-war Belgian government went into exile in 1940, the Belgian civil service remained in place for much of the occupation. The

Committee of Secretaries-General

The Committee of Secretaries-General (; ) was a committee of senior civil service, civil servants and technocracy, technocrats in German occupation of Belgium during World War II, German-occupied Belgium during World War II. It was formed shortly ...

, an administrative panel of civil servants, although conceived as a purely

technocratic

Technocracy is a form of government in which decision-makers appoint knowledge experts in specific domains to provide them with advice and guidance in various areas of their policy-making responsibilities. Technocracy follows largely in the tra ...

institution, has been accused of helping to implement German occupation policies. Despite its intention of mitigating harm to Belgians, it enabled but could not moderate German policies such as the

persecution of Jews

The persecution of Jews has been a major event in Jewish history prompting shifting waves of refugees and the formation of diaspora communities. As early as 605 BC, Jews who lived in the Neo-Babylonian Empire were persecuted and deported. Antis ...

and

deportation of workers to Germany. It did manage to delay the latter to October 1942.

[Gotovitch, José; Aron, Paul, eds. (2008). Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale en Belgique. Brussels: André Versaille ed. p. 408. .] Encouraging the Germans to delegate tasks to the Committee made their implementation much more efficient than the Germans could have achieved by force. Belgium depended on Germany for food imports, so the committee was always at a disadvantage in negotiations.

The

Belgian government in exile

The Belgian Government in London (; ), also known as the Pierlot IV Government, was the government in exile of Belgium between October 1940 and September 1944 during World War II. The government was wikt:tripartite, tripartite, involving minis ...

criticized the committee for helping the Germans.

The Secretaries-General were also unpopular in Belgium itself. In 1942, journalist

Paul Struye described them as "the object of growing and almost unanimous unpopularity." As the face of the German occupation authority, they became unpopular with the public, which blamed them for the German demands they implemented.

[

After the war, several of the Secretaries-General were tried for collaboration. Most were quickly acquitted. , the former secretary-general for internal affairs, was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment, and Gaston Schuind, Judicial Police of Brussels, was sentenced to five.]senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

from the centre-right Christian Social Party (PSC-CVP) and became president of the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the two legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it ...

.

Belgian police have also been accused of collaborating, especially in the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

.[ Those assassinations included leading figures suspected of resistance involvement or sympathy,]Société Générale

Société Générale S.A. (), colloquially known in English-speaking countries as SocGen (), is a French multinational universal bank and financial services company founded in 1864. It is registered in downtown Paris and headquartered nearby i ...

'', assassinated in February 1944. Among the retaliatory massacres of civilians[ were the Courcelles massacre, in which 20 civilians were killed by the Rexist paramilitary for the assassination of a ]Burgomaster

Burgomaster (alternatively spelled burgermeister, ) is the English form of various terms in or derived from Germanic languages for the chief magistrate or executive of a city or town. The name in English was derived from the Dutch .

In so ...

, and a massacre at Meensel-Kiezegem, where 67 were killed.

Channel Islands

The Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They are divided into two Crown Dependencies: the Jersey, Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, ...

were the only British-controlled territory in Europe to be occupied by Nazi Germany. The policy of the islands' governments was what they called "correct relations" with the German occupiers. There was no armed or violent resistance by islanders to the occupation. After 1945 allegations of collaboration were investigated. In November 1946, the UK Home Secretary informed the UK House of CommonsJersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

and Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, laws

Denmark

When on 9 April 1940, German forces invaded neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

Denmark, they violated a treaty of non-aggression signed the year before, but claimed they would "respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, and neutrality."parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

maintained control over domestic policy.Fall of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg and the Net ...

in June 1940.Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (Com ...

. The Danish government and King Christian X

Christian X (; 26 September 1870 – 20 April 1947) was King of Denmark from 1912 until his death in 1947, and the only King of Iceland as Kristján X, holding the title as a result of the personal union between Denmark and independent Ice ...

repeatedly discouraged sabotage and encouraged informing on the resistance movement. Resistance fighters were imprisoned or executed; after the war informants were sentenced to death.

Prior to, during and after the war, Denmark enforced a restrictive refugee policy; it handed over to German authorities at least 21 Jewish refugees who managed to cross the border;[Rescue, Expulsion, and Collaboration: Denmark's Difficulties with It's World War II Past ]

Vilhjálmur Örn Vilhjálmsson and Bent Blüdnikow, Jewish Political Studies Review Vol. 18, No. 3/4 (Fall 2006), pp. 3–29 (27 pages) Published By: Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, retrieved February 14, 2023 18 of them died in concentration camps, including a woman and her three children. In 2005 prime minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen

Anders Fogh Rasmussen (; born 26 January 1953) is a Danish politician who was the prime minister of Denmark from November 2001 to April 2009 and the Secretary General of NATO, secretary general of NATO from August 2009 to October 2014. He became ...

officially apologized for these policies.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along a ...

on 22 June 1941, German authorities demanded the arrest of Danish communists. The Danish government complied, directing the police to arrest 339 communists listed on secret registers. Of these, 246, including the three communist members of the Danish parliament, were imprisoned in the Horserød camp

Horserød Camp (also Horserød State Prison, Danish: ''Horserødlejren'' or ''Horserød Statsfængsel'') is an open state prison at Horserød, Denmark located in North Zealand, approximately seven kilometers from Helsingør. Built in 1917, Ho ...

, in violation of the Danish constitution. On 22 August 1941, the Danish parliament passed the Communist Law

The Communist Law or The Law on Prohibition Against Communist Associations and Communist Activities was an unconstitutional piece of Danish legislation passed under Nazi occupation on 22 August 1941 which banned the Communist Party of Denmark and ...

, outlawing the Communist Party of Denmark

The Communist Party of Denmark (, DKP) is a communist party in Denmark. The DKP was founded on 9 November 1919 as the Left-Socialist Party of Denmark (, VSP), through a merger of the Socialist Youth League and Socialist Labour Party of Denma ...

and also communist activities, in another violation of the Danish constitution. In 1943, about half of the imprisoned communists were transferred to Stutthof concentration camp

Stutthof was a Nazi concentration camp established by Nazi Germany in a secluded, marshy, and wooded area near the village of Stutthof (now Sztutowo) 34 km (21 mi) east of the city of Danzig (Gdańsk) in the territory of the German-an ...

, where 22 of them died.

Industrial production and trade were, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected towards Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark and feared that higher

Industrial production and trade were, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected towards Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark and feared that higher unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is the proportion of people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work du ...

and poverty could lead to civil unrest, resulting in a crackdown by the Germans.

France

Vichy France

The First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

hero Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Bénoni Omer Joseph Pétain (; 24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), better known as Marshal Pétain (, ), was a French marshal who commanded the French Army in World War I and later became the head of the Collaboration with Nazi Ger ...

became the head of the post-democratic French State

Vichy France (; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was a French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II, established as a result of the French capitulation after the defeat against G ...

''(État Français)'', governed not from Paris but from Vichy

Vichy (, ; ) is a city in the central French department of Allier. Located on the Allier river, it is a major spa and resort town and during World War II was the capital of Vichy France. As of 2021, Vichy has a population of 25,789.

Known f ...

, when the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

collapsed in July 1940 after losing the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

in June. Prime minister Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud (; 15 October 1878 – 21 September 1966) was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his economic liberalism and vocal opposition to Nazi Germany.

Reynaud opposed the Munich Agreement of Septembe ...

had resigned rather than sign the resulting armistice agreement. The National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

then gave Pétain absolute power to call a constituent assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

(constitutional convention) to write a new constitution. Instead Pétain used his plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin language, Latin term .

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary powe ...

s to establish the authoritarian French State.

Pierre Laval

Pierre Jean Marie Laval (; 28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He served as Prime Minister of France three times: 1931–1932 and 1935–1936 during the Third Republic (France), Third Republic, and 1942–1944 during Vich ...

and other Vichy ministers initially prioritized saving French lives and repatriating French prisoners of war. The illusion of autonomy was important to Vichy, which wanted to avoid direct rule by the German military government in Paris. (The Germans allowed several groups based in occupied Paris to organize, operate, publish and criticise the Vichy authorities for insufficiently eager collaboration. By doing so, the Germans implicitly threatened that these groups' leaders might replace any Vichy government that was too reluctant to meet German demands.)

Collaborationist movements

The four main political factions which emerged as leading proponents of radical collaborationism in France were:

* the National Popular Rally (, RNP), led by the neo-Socialist Marcel Déat;

* the

The four main political factions which emerged as leading proponents of radical collaborationism in France were:

* the National Popular Rally (, RNP), led by the neo-Socialist Marcel Déat;

* the French Popular Party

The French Popular Party (, PPF) was a French fascist and anti-semitic political party led by Jacques Doriot before and during World War II. It is generally regarded as the most collaborationist party of France.

Formation and early yea ...

(, PPF), founded by the ex-Communist Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot (; 26 September 1898 – 22 February 1945) was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

In 1936, after his exclusion from the French Communist Party, he founded the French Popular Pa ...

;

* the Revolutionary Social Movement (, MSR), founded by Eugène Deloncle

Eugène Deloncle (20 June 1890 – 17 January 1944) was a French politician and fascist leader who founded the organisation “Secret Committee of Revolutionary Action" (CSAR), better known as . He became a prominent Nazi collaborator during Wo ...

, who had led the pre-war vigilante ''Cagoule

A cagoule (, also spelled cagoul, kagoule or kagool), is the British English term for a lightweight weatherproof raincoat or anorak with a hood (usually without lining), which often comes in knee-length form.The Chambers Dictionary, 1994, The Ca ...

''; and

* Pierre Costantini

Pierre Dominique Costantini (16 February 1889 – 30 June 1986) was a French soldier, journalist, writer.

Life

Costantini fought as an officer in the First World War and as a reserve officer in the armée de l'air during 1939–1940. He founded t ...

's French League

The French League (: "French League for Purge, purging, mutual aid (politics), mutual aid and European integration, European collaboration") was a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, collaborationist French movement founded by Pier ...

().

These groups were small in size: between 1940 and 1944 fewer than 220,000 people in France and French North Africa

French North Africa (, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is a term often applied to the three territories that were controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. In contrast to French ...

joined collaborationist movements.

Uniformed collaboration

The collaboration of the French police

Law enforcement in France is centralized at the national level. Recently, legislation has allowed local governments to hire their own police officers which are called the ''Municipal Police (France), police municipale''.

There are two nation ...

was decisive for the implementation of the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

in occupied France. Germany used French police to maintain order and repress the resistance. The French police were responsible for the census of Jews, their arrest and their assembly in camps from where they were sent abroad to extermination camps. To do this the police requisitioned buses and used the rail network of SNCF

The Société nationale des chemins de fer français (, , SNCF ) is France's national State-owned enterprise, state-owned railway company. Founded in 1938, it operates the Rail transport in France, country's national rail traffic along with th ...

trains.[>] In January 1943, Laval established the Milice, a paramilitary">Milice.html" ;"title="> In January 1943, Laval established the Milice">> In January 1943, Laval established the Milice, a paramilitary police force led by Joseph Darnand that assisted the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

in fighting Resistance during World War II, the Resistance and persecuting Jews, it counted 30,000 members both male and female.

Communist party

Until the German invasion of Russia

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis powers, Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet ...

on 21 June 1941, the national leadership of the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (, , PCF) is a Communism, communist list of political parties in France, party in France. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its Member of the European Parliament, MEPs sit with The Left in the ...

(PCF) remained close to the line defined by the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

and the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, claiming that "the only legitimate struggle is the revolutionary struggle and not the pseudo-resistance of the Gaullists, pawns of British capitalism".German occupation

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the government of Nazi Germany at ...

, the clandestine edition of newspaper ''L'Humanité

(; ) is a French daily newspaper. It was previously an organisation of the SFIO, ''de facto'', and thereafter of the French Communist Party (PCF), and maintains links to the party. Its slogan is "In an ideal world, would not exist."

History ...

'' called on French workers to fraternise with German soldiers, presenting them not as enemies of the nation but as "class brothers".Otto Abetz

Otto Friedrich Abetz (26 March 1903 – 5 May 1958) was a German diplomat, a Nazi official and a convicted war criminal during World War II.

Abetz joined the Nazi Party and the SA in the early 1930s later becoming a member of the SS. Abetz pla ...

, the German ambassador in Paris.de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

as a reactionary and war-mongering soldier.

French workers for Germany

Vichy initially agreed, for every repatriated French prisoner-of-war, to send three French volunteers to work in German factories. When this program (known as la relève) didn't draw enough workers to please the Reich, Vichy began in February 1943 to conscript young Frenchmen, ages 18—20 into the ''Service du travail obligatoire

The ' (STO; ) was the forced enlistment and deportation of hundreds of thousands of French workers to Nazi Germany to work as Forced labor in Germany during World War II, forced labour for the German war effort during World War II.

The STO was ...

'' (STO; English: compulsory labour service), a compulsory two-year labour draft that resulted in the deportation to German labor camps of 800,000 Frenchmen.French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

rather than report for it. People began to disappear into forests and mountain wildernesses to join the '' maquis'' (rural Resistance).

Vichy collaboration in the Holocaust

Long before the Occupation, France had had a history of native anti-Semitism and philo-Semitism

Philosemitism, also called Judeophilia, is "defense, love, or admiration of Jews and Judaism". Such attitudes can be found in Western cultures across the centuries. The term originated in the nineteenth century by self-described German antisemit ...

, as seen in the controversy over the guilt of Alfred Dreyfus (from 1894 to 1906). Historians differ how much of Vichy's anti-Semitic campaigns came from native French roots, how much from willing collaboration with the German occupiers and how much from simple (and sometimes reluctant) cooperation with Nazi instructions.

Pierre Laval was an important decision-maker in the extermination of Jews, the Romani Holocaust

The Romani Holocaust was the genocide of European Roma and Sinti people during World War II. Beginning in 1933, Nazi Germany systematically persecuted the European Roma, Sinti and other peoples pejoratively labeled 'Gypsy' through forcible ...

, and of other "undesirables." Following an increasingly restrictive series of anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic measures, such as the Second law on the status of Jews, Vichy opened a series of internment camps in France

Numerous internment camps and concentration camps were located in France before, during and after World War II. Beside the camps created during World War I to intern German, Austrian and Ottoman civilian prisoners, the Third Republic (1871–194 ...

— such as one at Drancy

Drancy () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris in the Seine-Saint-Denis department in northern France. It is located 10.8 km (6.7 mi) from the center of Paris.

History

Toponymy

The name Drancy comes from Medieval Lati ...

— where Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and political opponents were interned. The French police

Law enforcement in France is centralized at the national level. Recently, legislation has allowed local governments to hire their own police officers which are called the ''Municipal Police (France), police municipale''.

There are two nation ...

directed by René Bousquet, under increasing German pressure, helped to deport 76,000 Jews (both directly and via the French camps) to Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

In 1995, President Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac (, ; ; 29 November 193226 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Pari ...

officially recognized the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of Jews during the war, in particular, the more than 13,000 victims, of whom only 2,500 survived, of the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

The Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup ( ; from , an abbreviation of ) was a mass arrest of Jews in Paris on 16–17 July 1942 by Vichy French police at the behest of the German occupational authorities. Occurring during World War II, Jews arrested during ...

of July 1942, in which Laval decided, of his own volition, to deport children along with their parents. Bousquet also organized the French police to work with the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

in the massive Marseille roundup (''rafle'') that decimated a whole neighbourhood in the Old Port.

Estimates of how many of France's Jews (about 300,000 at the start of the Occupation) died in the Holocaust range from about 60,000 (≅ 20%) to about 130,000 (≅ 43%). According to Serge Klarsfeld

Serge Klarsfeld (born 17 September 1935) is a Romanian-born French activist and Nazi hunter known for documenting the Holocaust in order to establish the record and to enable the prosecution of war criminals. Since the 1960s, he has made notable ...

's study of the records kept at the Drancy internment camp

Drancy internment camp () was an assembly and detention camp for confining Jews who were later deported to the extermination camps during the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, German occupation of France duri ...

, out of the 75,721 Jews deported from France to death camps in Poland, only 2,567 survived.

Aftermath

As the Liberation spread across France in 1944–45, so did the so-called Wild Purges ('' Épuration sauvage''). Resistance groups took summary reprisals, especially against suspected informers and members of Vichy's anti-partisan paramilitary, the Milice

The (French Militia), generally called (; ), was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy France, Vichy régime (with Nazi Germany, German aid) to help fight against the French Resistance during World War ...

. Unofficial courts tried and punished thousands of people accused (sometimes unjustly) of collaborating or consorting with the enemy. Estimates of the numbers of victims differ, but historians agree that the number will never be fully known.

As a formal legal order returned to France, the informal purges were replaced by ''l'Épuration légale

The (; French for 'legal purge') was the wave of official trials that followed the Liberation of France and the fall of the Vichy regime. The trials were largely conducted from 1944 to 1949, with subsequent legal action continuing for decade ...

'' (legal purge). The most notable, and most demanded, convictions were those of Pierre Laval, tried and executed in October 1945, and Marshal Philippe Pétain, whose 1945 death sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment in the island fortress of Yeu

Yeu or YEU could refer to:

* Île d'Yeu

Ile or ILE may refer to:

Ile

* Ile, a Puerto Rican singer

* Ile District (disambiguation), multiple places

* Ilé-Ifẹ̀, an ancient Yoruba city in south-western Nigeria

* Interlingue (ISO 639:ile), ...

in Brittany, where he died in 1951. Joseph Darnand

Joseph Darnand (19 March 1897 – 10 October 1945) was a French far-right political figure, Nazi collaborator and convicted war criminal during the Second World War. A decorated veteran of the First World War and the Battle of France in 1940, h ...

, the ''Milice'' leader, was convicted and executed in October 1945.

owever, not every prominent collaborationist had survived to see the Liberation. Pétain's former deputy, Admiral François Darlan, had been assassinated in December 1942 after coming to terms with the Allies invading North Africa. (See #French North Africa below.) Eugène Deloncle

Eugène Deloncle (20 June 1890 – 17 January 1944) was a French politician and fascist leader who founded the organisation “Secret Committee of Revolutionary Action" (CSAR), better known as . He became a prominent Nazi collaborator during Wo ...

, the former ''Cagoule

A cagoule (, also spelled cagoul, kagoule or kagool), is the British English term for a lightweight weatherproof raincoat or anorak with a hood (usually without lining), which often comes in knee-length form.The Chambers Dictionary, 1994, The Ca ...

'' leader, turned towards the German resistance and died in a shoot-out with the German Security Service (SD) in January 1944. In June 1944 (just after D-Day), the Resistance in Paris killed the pro-Axis broadcaster Philippe Henriot in front of his family. In February 1945, near the very end of the European war, the Germans pressed Jacques Doriot

Jacques Doriot (; 26 September 1898 – 22 February 1945) was a French politician, initially communist, later fascist, before and during World War II.

In 1936, after his exclusion from the French Communist Party, he founded the French Popular Pa ...

of the PPF to reconcile with his bitter rival, Marcel Déat

Marcel Déat (; 7 March 1894 – 5 January 1955) was a French politician. Initially a socialist and a member of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), he led a breakaway group of right-wing Neosocialists out of the SFIO in 19 ...

of the RNP, but Doriot died when the car taking him to meet Déat was strafed by Allied aircraft. Déat himself, however, escaped to Italy, where he died in 1955.]

Several decades later, a few surviving ex-collaborators such as Paul Touvier

Paul Claude Marie Touvier (; 3 April 1915 – 17 July 1996) was a French Nazi collaborator and war criminal during World War II in Occupied France. In 1994, he became the first Frenchman ever convicted of crimes against humanity, for his parti ...

were tried for crimes against humanity. René Bousquet was rehabilitated and regained some influence in French politics, finance and journalism, but was nonetheless investigated in 1991 for deporting Jews. He was assassinated in 1993 just before his trial would have begun. Maurice Papon

Maurice Papon (; 3 September 1910 – 17 February 2007) was a French civil servant and Nazi collaborator who was convicted of crimes against humanity committed during the occupation of France. Papon led the police in major prefectures from ...

served as prefect of the Paris police under President de Gaulle (thus bearing ultimate responsibility for the Paris massacre of 1961

The Paris massacre of 1961 (also called the 17 October 1961 massacre in France) was the mass killing of Algerians who were living in Paris by the French National Police. It occurred on 17 October 1961, during the Algerian War (1954–62). Under ...

) and, 20 years later, as Budget Minister under President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, ; ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as simply Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Ministry of the Economy ...

, before Papon's 1998 conviction and imprisonment for crimes against humanity in organizing the deportation of 1,560 Jews from the Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

region to the French internment camp at Drancy.

Other collaborators such as Émile Dewoitine

Émile Dewoitine (26 September 1892 – 5 July 1979) was a French aviation industrialist.

Prewar industrial activities

Born in Crépy-en-Laonnais, Émile Dewoitine entered the aviation industry by working at Latécoère during World War I. ...

also managed to have important roles after the war. Dewoitine was eventually named head of Aérospatiale

Aérospatiale () was a major French state-owned aerospace manufacturer, aerospace and arms industry, defence corporation. It was founded in 1970 as () through the merger of three established state-owned companies: Sud Aviation, Nord Aviation ...

, which created the Concorde

Concorde () is a retired Anglo-French supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France and the United Kingdom signed a treaty establishin ...

airplane.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembour ...

was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940 and remained under German occupation until early 1945. Initially, the country was governed as a distinct region as the Germans prepared to assimilate its Germanic population into Germany itself. The ''Volksdeutsche Bewegung

Volksdeutsche Bewegung ( German; literally "Ethnic German Movement") was a Nazi movement in Luxembourg that flourished under the German-occupied Luxembourg during World War II.

Formed by Damian Kratzenberg, a university professor with a Ge ...

'' (VdB) was founded in Luxembourg in 1941 under the leadership of Damian Kratzenberg, a German teacher at the Athénée de Luxembourg.Heim ins Reich

The ''Heim ins Reich'' (; meaning "back home to the Reich") was a foreign policy pursued by Adolf Hitler before and during World War II, beginning in October 1936 ee Nazi Four Year Plan; Grams, 2021; Grams 2025 The aim of Hitler's initiative ...

''. In August 1942, Luxembourg was annexed into Nazi Germany, and Luxembourgish men were drafted into the German military.

Monaco

During the Nazi occupation of Monaco

Monaco, officially the Principality of Monaco, is a Sovereign state, sovereign city-state and European microstates, microstate on the French Riviera a few kilometres west of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria, in Western Europe, ...

, the police arrested and turned over 42 Central European Jewish refugees to the Nazis while also protecting Monaco's own Jews.

Netherlands

The Germans re-organized the pre-war Dutch police and established a new Communal Police, which helped Germans fight the country's resistance and to deport Jews. The

The Germans re-organized the pre-war Dutch police and established a new Communal Police, which helped Germans fight the country's resistance and to deport Jews. The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands

The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (, ; NSB) was a Dutch fascist and later Nazi political organisation that eventually became a political party. As a parliamentary party participating in legislative elections, the NSB had some suc ...

(NSB) had militia units, whose members were transferred to other paramilitaries like the Netherlands Landstorm or the Control Commando. A small number of people greatly assisted the German in their hunt for Jews, including some policemen and the Henneicke Column. Many of them were members of the NSB. The column alone was responsible for the arrest of about 900 Jews.

Norway

In Norway, the national government, headed by Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (; ; 18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer, politician and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, Nazi collaborator who Quisling regime, headed the government of N ...

, was installed by the Germans as a puppet regime during the German occupation, while king Haakon VII

Haakon VII (; 3 August 187221 September 1957) was King of Norway from 18 November 1905 until his death in 1957.

The future Haakon VII was born in Copenhagen as Prince Carl of Denmark. He was the second son of the Crown Prince and Crown Princess ...

and the legally elected Norwegian government fled into exile. Quisling encouraged Norwegians to volunteer for service in the Waffen-SS, collaborated in the deportation of Jews, and was responsible for the executions of members of the Norwegian resistance movement

The Norwegian resistance (Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Motstandsbevegelsen'') to the German occupation of Norway, occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany began after Operation Weserübung in 1940 and ended in 1945. It took several forms:

*As ...

.

About 45,000 Norwegian collaborators joined the fascist party ''Nasjonal Samling

The Nasjonal Samling (, NS; ) was a Norway, Norwegian far-right politics, far-right political party active from 1933 to 1945. It was the only legal party of Norway from 1942 to 1945. It was founded by former minister of defence Vidkun Quisling a ...

'' (National Union), and about 8,500 of them enlisted in the ''Hirden

''Hirden'' (the ''hird'') was a uniformed paramilitary organisation during the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany, modelled the same way as the German Sturmabteilungen.

Overview

Vidkun Quisling's fascist party Nasjonal Samling frequently use ...

'' collaborationist paramilitary organization. About 15,000 Norwegians volunteered on the Nazi side and 6,000 joined the Germanic SS. In addition, Norwegian police units like the Statspolitiet

(; shortened STAPO) was from 1941 to 1945 a National Socialist armed police force that consisted of Norwegian officials after Nazi German pattern. It operated independently of the ordinary Norwegian police. The force was established on 1 June 1 ...

helped arrest many of Jews in Norway

The history of Jews in Norway dates back to the 1400s. Although there were very likely Jewish merchants, sailors and others who entered Norway during the Middle Ages, no efforts were made to establish a Jewish community. Through the early mod ...

. All but 23 of the 742 Jews deported to concentration camps and death camps were murdered or died before the end of the war. Knut Rød, the Norwegian police officer most responsible for the arrest, detention and transfer of Jewish men, women and children to SS troops at Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

harbour, was later acquitted during the legal purge in Norway after World War II

The legal purge in Norway after World War II (; ) took place between May 1945 and August 1948 against anyone who was found to have Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, collaborated with the German occupation of Norway, German occupat ...

in two highly publicized trials that remain controversial.["He didn't mean to harm any good Norwegian" – the acquittal of Knut Rød, one of the organisers of the Norwegian Jew's deportation to Auschwitz, Seventh European Social Science History conference 26 February – 1 March 2008]

retrieved 10 March 2008

''Nasjonal Samling'' had very little support among the population at large and Norway was one of few countries where resistance during World War II

During World War II, resistance movements operated in German-occupied Europe by a variety of means, ranging from non-cooperation to propaganda, hiding crashed pilots and even to outright warfare and the recapturing of towns. In many countries, r ...

was widespread before the turning point of the war in 1942–43.

After the war, Quisling was executed by firing squad. His name became an international eponym

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

for "traitor

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

".

Collaboration in Eastern Europe

Albania

After the Italian invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania was a brief military campaign which was launched by Fascist Italy, Italy against Albanian Kingdom (1928–1939), Albania in 1939. The conflict was a result of the imperialistic policies of the Italian prime m ...

, the Royal Albanian Army, police and gendarmerie

A gendarmerie () is a paramilitary or military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (). In France and so ...

were amalgamated into the Italian armed forces in the newly created Italian protectorate of Albania.

The Albanian Fascist Militia

The Albanian Fascist Militia (MFSH) (') was an Albanian fascist paramilitary group formed in 1939, following the Italian invasion of Albania. As a wing of the Italian Blackshirts (MVSN), the militia initially consisted of Italian colonists in Al ...

formed after the Italian invasion of Albania in April 1939. In the Yugoslav part of Kosovo, it established the Vulnetari (or Kosovars), a volunteer militia of Kosovo Albanians

The Albanians of Kosovo (, ), also commonly called Kosovo Albanians, Kosovan Albanians or Kosovars (), constitute the largest ethnic group in Kosovo.

Kosovo Albanians belong to the Albanians, ethnic Albanian sub-group of Ghegs, who inhabit the ...

. Vulnetari units often attacked ethnic Serbs and carried out raids against civilian targets.Kosovo

Kosovo, officially the Republic of Kosovo, is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe with International recognition of Kosovo, partial diplomatic recognition. It is bordered by Albania to the southwest, Montenegro to the west, Serbia to the ...

and neighboring regions.

Baltic states

The three Baltic republics of Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

, Latvia

Latvia, officially the Republic of Latvia, is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is one of the three Baltic states, along with Estonia to the north and Lithuania to the south. It borders Russia to the east and Belarus to t ...

and Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, first invaded by the Soviet Union, were later occupied by Germany and incorporated, together with what had been the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, Byelorussian SSR or Byelorussia; ; ), also known as Soviet Belarus or simply Belarus, was a Republics of the Soviet Union, republic of the Soviet Union (USSR). It existed between 1920 and 19 ...

of the U.S.S.R.

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until it dissolved in 1991. During its existence, it was the largest country by are ...

(Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

, see below), into Reichskommissariat Ostland

The (RKO; ) was an Administrative division, administrative entity of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories of Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1945. It served as the German Civil authority, civilian occupation regime in Lithuania, La ...

.

Estonia

In German plans, Estonia was to become an area for future German settlements, as Estonians themselves were considered high on the Nazi racial scale, with potential for Germanization. Unlike the other Baltic states, the seizure of Estonian territory by German troops was relatively long, from July 7 to December 2, 1941. This period was used by the Soviets to carry out a wave of repression against Estonians. It is estimated that the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

's subordinate Destruction battalions killed some 2,000 Estonian civilians, and 50–60,000 people were deported deep into the USSR. 10,000 of them died in the GULAG system within a year. Many Estonians fought against Soviet troops on the German side, hoping to liberate their country. Some 12,000 Estonian partisans took part in the fighting. Of great importance were the 57 Finnish-trained members of the Erna group, who operated behind enemy lines.

Resistance groups were organised by Germans in August 1941 into the Omakaitse (), which had between 34,000 and 40,000 members, mainly based on the Kaitseliit, dissolved by the Soviets. Omakaitse was in charge of clearing the German army's rear of Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

soldiers, NKVD members, and Communist activists. Within a year its members killed 5,500 Estonian residents. Later, they performed guard duty and fought Soviet partisans flown into Estonia. From among Omakaitse members were recruited Estonian policemen, members of the Estonian Auxiliary Police

Estonian Auxiliary Police (, ) was Estonian auxiliary police forces unit that were trained to be capable of being paramilitary police for bandenbekämpfung, combat operations, counterinsurgency, crowd control, internal security, rear security (r ...

and officers of the Estonian 20th Waffen-SS Division.

The Germans formed a puppet government, the Estonian Self-Administration

Estonian Self-Administration (, ), also known as the ''Directorate'', was the puppet government set up in Estonia during the occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany. It was headed by Hjalmar Mäe. The Estonian Self-Administration was subordinated ...

, headed by Hjalmar Mäe

Hjalmar-Johannes Mäe ( in Tuhala, Kreis Harrien, Governorate of Estonia, Russian Empire – 10 April 1978 in Graz, Austria) was an Estonian politician.

Mäe was twice a candidate to the Riigikogu, in the 1929 Estonian parliamentary election as a ...

. This government had considerable autonomy in internal affairs, such as filling police posts. The Security Police in Estonia ( SiPo) had a mixed Estonian-German structure (139 Germans and 873 Estonians) and was formally under the Estonian Self-Administration. Estonian police cooperated with Germans in rounding up Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, Roma

Roma or ROMA may refer to:

People, characters, figures, names

* Roma or Romani people, an ethnic group living mostly in Europe and the Americas.

* Roma called Roy, ancient Egyptian High Priest of Amun

* Roma (footballer, born 1979), born ''Paul ...

, communists and those deemed enemies of existing order or asocial elements. The police also helped to conscript

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

Estonians for forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

and military service

Military service is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, air forces, and naval forces, whether as a chosen job (volunteer military, volunteer) or as a result of an involuntary draft (conscription).

Few nations, such ...

under German command. Most of the small population of Estonian Jews fled before the Germans arrived, with only about a thousand remaining. All of them were arrested by Estonian police and executed by Omakaitse. Members of the Estonian Auxiliary Police

Estonian Auxiliary Police (, ) was Estonian auxiliary police forces unit that were trained to be capable of being paramilitary police for bandenbekämpfung, combat operations, counterinsurgency, crowd control, internal security, rear security (r ...

and 20th Waffen-SS Division also executed Jewish prisoners sent to concentration and labor camps established by the Germans on Estonian territory.

Immediately after entering Estonia, the Germans began forming volunteer Estonian units the size of a battalion. By January 1942, six Security Groups (battalions No. 181-186, about 4,000 men) had been formed and were subordinate to the Wehrmacht 18th Army. After the one-year contract expired, some volunteers transferred to the Waffen-SS or returned to civilian life, and three Eastern Battalions (No. 658-660) were formed from those who remained. They fought until early 1944, after which their members transferred to the 20th Waffen-SS Division.

Beginning in September 1941, the SS and police command created four Infantry Defence Battalions (No. 37-40) and a reserve and sapper battalion (No. 41-42), which were operationally subordinate to the Wehrmacht. From 1943 they were called Police Battalions, with 3,000 serving in them. In 1944 they were transformed into two infantry battalions and evacuated to Germany in the fall of 1944, where they were incorporated into the 20th Waffen-SS Division.

In the fall of 1941, the Germans also formed eight police battalions (No. 29-36), of which only Battalion No. 36 had a typically military purpose. However, due to shortages, most of them were sent to the front near Leningrad, and were mostly disbanded in 1943. That same year, the SS and police command created five new Security and Defense Battalions (they inherited No. 29-33 and had more than 2,600 men). In the spring of 1943, five Defence Battalions (No. 286-290) were established as compulsory military service units. The 290th Battalion consisted of Estonian Russians. Battalions No. 286, 288 and 289 were used to fight partisans in Belarus. On Aug. 28, 1942, the Germans formed the volunteer Estonian Waffen-SS Legion. Of the approximately 1,000 volunteers, 800 were incorporated into Battalion Narva and sent to Ukraine in the spring of 1943. Due to the shrinking number of volunteers, in February 1943 the Germans introduced compulsory conscription in Estonia. Born between 1919 and 1924 faced the choice of going to work in Germany, joining the Waffen-SS or Estonian auxiliary battalions. 5,000 joined the Estonian Waffen-SS Legion, which was reorganized into the 3rd Estonian Waffen-SS Brigade.

As the Red Army advanced, a general mobilization was announced, officially supported by Estonia's last Prime Minister

On Aug. 28, 1942, the Germans formed the volunteer Estonian Waffen-SS Legion. Of the approximately 1,000 volunteers, 800 were incorporated into Battalion Narva and sent to Ukraine in the spring of 1943. Due to the shrinking number of volunteers, in February 1943 the Germans introduced compulsory conscription in Estonia. Born between 1919 and 1924 faced the choice of going to work in Germany, joining the Waffen-SS or Estonian auxiliary battalions. 5,000 joined the Estonian Waffen-SS Legion, which was reorganized into the 3rd Estonian Waffen-SS Brigade.

As the Red Army advanced, a general mobilization was announced, officially supported by Estonia's last Prime Minister Jüri Uluots

Jüri Uluots (13 January 1890 – 9 January 1945) was an Estonian prime minister, journalist, prominent attorney and distinguished Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Tartu.

Early life

Uluots was born in Kirbla Pari ...

. By April 1944, 38,000 Estonians had been drafted. Some went into the 3rd Waffen-SS Brigade, which was enlarged to division size ( 20th Waffen-SS Division: 10 battalions, more than 15,000 men in the summer of 1944) and also incorporated most of the already existing Estonian units (mostly Eastern Battalions). Younger men were conscripted into other Waffen-SS units. From the rest, six Border Defense Regiments and four Police Fusilier Battalions (Nos. 286, 288, 291, and 292).

The Estonian Security Police and SD, the 286th, 287th and 288th Estonian Auxiliary Police

Estonian Auxiliary Police (, ) was Estonian auxiliary police forces unit that were trained to be capable of being paramilitary police for bandenbekämpfung, combat operations, counterinsurgency, crowd control, internal security, rear security (r ...

battalions, and 2.5–3% of the Estonian Omakaitse (Home Guard) militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

units (between 1,000 and 1,200 men) took part in rounding up, guarding or killing of 400–1,000 Roma and 6,000 Jews in concentration camps in the Pskov region of Russia and the Jägala, Vaivara, Klooga and Lagedi

Lagedi () is a small borough () in Rae Parish, Harju County, northern Estonia. As of 2022, the settlement's population was 1,083.

Lagedi has a station on the Elron's eastern route.

Lagedi was the site of a slave-labor camp during German occupa ...

concentration camps in Estonia.

Guarded by these units, 15,000 Soviet POWs died in Estonia: some through neglect and mistreatment and some by execution.

Latvia

Deportations and murders of Latvians by the Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

reached their peak in the days before the capture of Soviet-occupied Riga

Riga ( ) is the capital, Primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Latvia, largest city of Latvia. Home to 591,882 inhabitants (as of 2025), the city accounts for a third of Latvia's total population. The population of Riga Planni ...

by German forces. Those that the NKVD could not deport before the Germans arrived were shot at the Central Prison. The RSHA

The Reich Security Main Office ( , RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and , the head of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS). The organization's stat ...

's instructions to their agents to unleash pogroms fell on fertile ground. After the Einsatzkommando

During World War II, the Nazi German ' were a sub-group of the ' (mobile killing squads) – up to 3,000 men total – usually composed of 500–1,000 functionaries of the SS and Gestapo, whose mission was to exterminate Jews, Polish intellect ...

1a and part of Einsatzkommando 2 entered the Latvian capital, Einsatzgruppe A

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the impl ...

's commander Franz Walter Stahlecker

Franz Walter Stahlecker (10 October 1900 – 23 March 1942) was commander of the SS security forces (''Sicherheitspolizei'' (SiPo) and the ''Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) for the ''Reichskommissariat Ostland'' in 1941–42. Stahlecker commanded ''Ein ...

made contact with Viktors Arājs

Viktors Arājs (13 January 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a Latvian/Baltic German collaborator and Nazi SS SD officer who took part in the Holocaust during the German occupation of Latvia and Belarus as the leader of the Arajs Kommando, a col ...

on 1 July and instructed him to set up a commando unit. It was later named Latvian Auxiliary Police

Latvian Auxiliary Police was a paramilitary force created from Latvian volunteers and conscripts by the Nazi German authorities who occupied the country in June/July 1941. It was part of the '' Schutzmannschaft'' (Shuma), native police forces o ...

or ''Arajs Kommando

The Arajs ''Kommando'' (; ) was a paramilitary unit of the ''Sicherheitsdienst'' (SD) active in German-occupied Latvia from 1941 to 1943. It was led by SS commander and Nazi collaborator Viktors Arājs and composed of ethnic Latvian volunte ...

s''. The members, far-right students and former officers were all volunteers, and free to leave at any time.

The next day, 2 July, Stahlecker instructed Arājs to have the Arājs Kommandos unleash pogroms

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century attacks on Jews i ...

that looked spontaneous, before the German occupation authorities were properly established. Einsatzkommando-influenced mobs of former members of Pērkonkrusts

Pērkonkrusts (, "Thunder Cross") was a Latvian ultranationalist, Anti-German sentiment, anti-German, anti-Slavic, and antisemitic political party founded in 1933 by Gustavs Celmiņš, borrowing elements of German nationalism—but being unsym ...

and other extreme right-wing groups began pillaging and making mass arrests, and killed 300 to 400 Riga Jews. Killings continued under the supervision of SS ''Brigadeführer

''Brigadeführer'' (, ) was a paramilitary rank of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that was used between 1932 and 1945. It was mainly known for its use as an SS rank. As an SA rank, it was used after briefly being known as '' Untergruppenführer'' in ...

'' Walter Stahlecker, until more than 2,700 Jews had died.

The activities of the Einsatzkommando were constrained after the full establishment of the German occupation authority, after which the SS made use of select units of native recruits. German General Wilhelm Ullersperger and Voldemārs Veiss

__NOTOC__

Voldemārs Veiss (7 November 1899 – 17 April 1944) was a Latvian officer and prominent Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, Nazi collaborator, who served in the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany.

When Riga, the capital of Latvia ...

, a well known Latvian nationalist, appealed to the population in a radio address to attack "internal enemies". During the next few months, the Latvian Auxiliary Security Police primarily focused on killing Jews, Communists and Red Army stragglers in Latvia and in neighbouring Byelorussia.

In February–March 1943, eight Latvian battalions took part in the punitive anti-partisan Operation Winterzauber near the Belarus–Latvia border

The Belarus–Latvia border is of length. It spans from the tripoint with Lithuania to the tripoint with Russia. It is an external border of the European Union.

The current border between the republics of Belarus (CIS member) and Latvia (E ...

, which resulted in 439 burned villages, 10,000 to 12,000 deaths, and over 7,000 taken for forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

or imprisoned at the Salaspils concentration camp. This group alone killed almost half of Latvia's Jewish population,[Andrew Ezergailis. The Holocaust in Latvia, 1941–1944: the missing center. Historical Institute of Latvia, 1996. , pp. 182–189] about 26,000 Jews, mainly in November and December 1941.Aizsargi

Aizsargi (; officially – , or LAO) was a volunteer paramilitary organization, militia with some characteristics of a military reserve force in Latvia during the interbellum period (1918–1939).

The Aizsargi was created on March 30, 1919, b ...

). This helped with a chronic German personnel shortage and provided the Germans with relief from the psychological stress of routinely murdering civilians. By the autumn of 1941, the SS had deployed the Latvian Auxiliary Police

Latvian Auxiliary Police was a paramilitary force created from Latvian volunteers and conscripts by the Nazi German authorities who occupied the country in June/July 1941. It was part of the '' Schutzmannschaft'' (Shuma), native police forces o ...

battalions to Leningrad, where they were consolidated into the 2nd Latvian SS Infantry Brigade

The 2nd SS Infantry Brigade (mot.) () was formed on the 15 May 1941, under the command of Karl Fischer von Treuenfeld with the 4th and 5th SS Infantry (formerly ''Totenkopf'') Regiments and began its operational service in September in the Arm ...

.[Valdis O. Lumans. Book Review: Symposium of the Commission of the Historians of Latvia, The Hidden and Forbidden History of Latvia under Soviet and Nazi Occupations, 1940–1991: Selected Research of the Commission of the Historians of Latvia, Vol. 14, Institute of the History of Latvia Publications:European History Quarterly 2009 39: 184] In 1943, this brigade, which later became the 19th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (2nd Latvian)

__NOTOC__

The 19th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (2nd Latvian) (, ) was an infantry division of the Waffen-SS during World War II. It was the second Latvian division formed in January 1944, after its sister unit, the 15th Waffen Grenadi ...

, was consolidated with the 15th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Latvian) to become the Latvian Legion

The Latvian Legion () was a formation of the Nazi German Waffen-SS during World War II. Created in 1943, it consisted primarily of ethnic Latvians.Gerhard P. Bassler, ''Alfred Valdmanis and the politics of survival'', 2000, p150 Mirdza Kate Balta ...

.Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

unit, it was voluntary only in name; approximately 80–85% of its men were conscripts.

Lithuania

Prior to the German invasion, some leaders in Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

and in exile believed Germany would grant the country autonomy, as they had the Slovak Republic

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's ...

. The German intelligence service Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

believed that it controlled the Lithuanian Activist Front

The Lithuanian Activist Front or LAF () was a Lithuanian underground resistance organization established in 1940 after the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states (1940), Soviets occupied Lithuania. Its goal was to free Lithuanian Soviet Socialist ...

, a pro-German organization based at the Lithuanian embassy in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

.[ Tadeusz Piotrowski, ''Poland's Holocaust'', McFarland & Company, 1997, ]

Google Print, pp. 163–68

/ref> Lithuanians formed the Provisional Government of Lithuania

The Provisional Government of Lithuania () was an attempted temporary government, provisional government to form an independent Lithuanian state in June Uprising in Lithuania, the last days of the Soviet occupation of Lithuania (1940), first Sovi ...

on their own initiative, but Germany did not recognize it diplomatically, or allow Lithuanian ambassador Kazys Škirpa

Kazys Škirpa (18 February 1895 – 18 August 1979) was a Lithuanian military officer and diplomat. He founded the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF), which attempted to establish Lithuanian independence in June 1941.

Army career

In World W ...

to become prime minister, instead actively thwarting his activities. The provisional government disbanded, since it had no power and it had become clear that the Germans came as occupiers not liberators from Soviet occupation, as initially thought. By 1943, the German opinion of Lithuanians was that they had failed to show allegiance to them.Kaunas

Kaunas (; ) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius, the fourth largest List of cities in the Baltic states by population, city in the Baltic States and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaun ...

on 25 June 1941.Gypsies

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Romani people

, image =

, image_caption =

, flag = Roma flag.svg

, flag_caption = Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted at the 1971 World Romani Congress

, ...

.Lithuanian Security Police

The Lithuanian Security Police (LSP), also known as ''Saugumas'' (), was a local police force that operated in German-occupied Lithuania from 1941 to 1944, in collaboration with the occupational authorities. Collaborating with the Nazi Sipo (sec ...

was created, subordinate to Nazi Germany's Security Police and Criminal Police.Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions

The Lithuanian Auxiliary Police was a Schutzmannschaft formation formed during the German occupation of Lithuania between 1941 and 1944, with the first battalions originating from the most reliable freedom fighters, disbanded following the 194 ...

, 10 were involved in the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

. On August 16, the head of the Lithuanian police, , ordered the arrest of Jewish men and women with Bolshevik activities: "In reality, it was a sign to kill everyone." The Special SD and German Security Police Squad in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

killed 70,000 Jews in Paneriai and other places.Minsk

Minsk (, ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administra ...

, the 2nd Battalion shot about 9,000 Soviet prisoners of war, and in Slutsk

Slutsk is a town in Minsk Region, in central Belarus. It serves as the administrative center of Slutsk District, and is located on the Sluch (Belarus), Sluch River south of the capital Minsk. As of 2025, it has a population of 59,450.

Geography ...