Ceratosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Ceratosaurus'' (from

The first specimen, the holotype USNM 4735, was discovered and excavated by farmer Marshall Parker Felch in 1883 and 1884. Found in articulation, with the bones still connected to each other, it was nearly complete, including the skull. Significant missing parts include an unknown number of vertebrae; all but the last ribs of the trunk; the

The first specimen, the holotype USNM 4735, was discovered and excavated by farmer Marshall Parker Felch in 1883 and 1884. Found in articulation, with the bones still connected to each other, it was nearly complete, including the skull. Significant missing parts include an unknown number of vertebrae; all but the last ribs of the trunk; the  In an 1892 paper, Marsh published the first skeletal reconstruction of ''Ceratosaurus'', which depicts the animal at in length and in height. As noted by Gilmore in 1920, the trunk was depicted much too long in this reconstruction, incorporating at least six dorsal vertebrae too many. This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of

In an 1892 paper, Marsh published the first skeletal reconstruction of ''Ceratosaurus'', which depicts the animal at in length and in height. As noted by Gilmore in 1920, the trunk was depicted much too long in this reconstruction, incorporating at least six dorsal vertebrae too many. This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of

In their 2000 monograph, Madsen and Welles confirmed the assignment of these finds to ''Ceratosaurus''. In addition, they ascribed several teeth to the genus, which had originally been described by Janensch as a possible species of '' Labrosaurus'', ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi''. Other authors questioned the assignment of any of the Tendaguru finds to ''Ceratosaurus'', noting that none of these specimens displays features diagnostic for that genus. In 2011, Rauhut found both ''C. roechlingi'' and ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi'' to be possible ceratosaurids, but found them to be not diagnostic at genus level and therefore designated them as ''

In their 2000 monograph, Madsen and Welles confirmed the assignment of these finds to ''Ceratosaurus''. In addition, they ascribed several teeth to the genus, which had originally been described by Janensch as a possible species of '' Labrosaurus'', ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi''. Other authors questioned the assignment of any of the Tendaguru finds to ''Ceratosaurus'', noting that none of these specimens displays features diagnostic for that genus. In 2011, Rauhut found both ''C. roechlingi'' and ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi'' to be possible ceratosaurids, but found them to be not diagnostic at genus level and therefore designated them as ''

''Ceratosaurus'' followed the

''Ceratosaurus'' followed the

The

The

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the spine of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype. At least 20 vertebrae formed the neck and back in front of the

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the spine of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype. At least 20 vertebrae formed the neck and back in front of the  The

The

In his original description of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype and subsequent publications, Marsh noted a number of characteristics that were unknown in all other theropods known at the time. Two of these features, the fused pelvis and fused metatarsus, were known from modern-day birds, and according to Marsh, clearly demonstrate the close relationship between the latter and dinosaurs. To set the genus apart from ''Allosaurus'', ''Megalosaurus'', and

In his original description of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype and subsequent publications, Marsh noted a number of characteristics that were unknown in all other theropods known at the time. Two of these features, the fused pelvis and fused metatarsus, were known from modern-day birds, and according to Marsh, clearly demonstrate the close relationship between the latter and dinosaurs. To set the genus apart from ''Allosaurus'', ''Megalosaurus'', and  The following

The following

Within the Morrison and LourinhĂŁ Formation, ''Ceratosaurus'' fossils are frequently found in association with those of other large theropods, including the megalosaurid ''

Within the Morrison and LourinhĂŁ Formation, ''Ceratosaurus'' fossils are frequently found in association with those of other large theropods, including the megalosaurid '' Furthermore, Henderson suggested that ''Ceratosaurus'' could have avoided competition by preferring different prey items; the evolution of its extremely elongated teeth might have been a direct result of the competition with the long-snouted ''Allosaurus'' morph. Both species could also have preferred different parts of carcasses when acting as scavengers. The elongated teeth of ''Ceratosaurus'' could have served as visual signals facilitating the recognition of members of the same species, or for other social functions. In addition, the large size of these theropods would have tended to decrease competition, as the number of possible prey items increases with size.

Foster and Daniel Chure, in a 2006 study, concurred with Henderson that ''Ceratosaurus'' and ''Allosaurus'' generally shared the same habitats and preyed upon the same types of prey, thus likely had different feeding strategies to avoid competition. According to these researchers, this is also evidenced by different proportions of the skull, teeth, and fore limb. The distinction between the two ''Allosaurus'' morphs, however, was questioned by some later studies.

Furthermore, Henderson suggested that ''Ceratosaurus'' could have avoided competition by preferring different prey items; the evolution of its extremely elongated teeth might have been a direct result of the competition with the long-snouted ''Allosaurus'' morph. Both species could also have preferred different parts of carcasses when acting as scavengers. The elongated teeth of ''Ceratosaurus'' could have served as visual signals facilitating the recognition of members of the same species, or for other social functions. In addition, the large size of these theropods would have tended to decrease competition, as the number of possible prey items increases with size.

Foster and Daniel Chure, in a 2006 study, concurred with Henderson that ''Ceratosaurus'' and ''Allosaurus'' generally shared the same habitats and preyed upon the same types of prey, thus likely had different feeding strategies to avoid competition. According to these researchers, this is also evidenced by different proportions of the skull, teeth, and fore limb. The distinction between the two ''Allosaurus'' morphs, however, was questioned by some later studies.  In his 1986 popular book ''

In his 1986 popular book ''

The strongly shortened metacarpals and phalanges of ''Ceratosaurus'' raise the question whether the manus retained the grasping function assumed for other basal theropods. Within the Ceratosauria, an even more extreme manus reduction can be observed in abelisaurids, where the forelimb lost its original function, and in ''Limusaurus''. In a 2016 paper on the anatomy of the ''Ceratosaurus'' manus, Carrano and Jonah Choiniere stressed the great morphological similarity of the manus with those of other basal theropods, suggesting that it still fulfilled its original grasping function, despite its shortening. Although only the first phalanges are preserved, the second phalanges would have been mobile, as indicated by the well-developed articular surfaces, and the digits would likely have allowed a similar degree of motion as in other basal theropods. As in other theropods other than abelisaurids, digit I would have been slightly turned in when flexed.

The strongly shortened metacarpals and phalanges of ''Ceratosaurus'' raise the question whether the manus retained the grasping function assumed for other basal theropods. Within the Ceratosauria, an even more extreme manus reduction can be observed in abelisaurids, where the forelimb lost its original function, and in ''Limusaurus''. In a 2016 paper on the anatomy of the ''Ceratosaurus'' manus, Carrano and Jonah Choiniere stressed the great morphological similarity of the manus with those of other basal theropods, suggesting that it still fulfilled its original grasping function, despite its shortening. Although only the first phalanges are preserved, the second phalanges would have been mobile, as indicated by the well-developed articular surfaces, and the digits would likely have allowed a similar degree of motion as in other basal theropods. As in other theropods other than abelisaurids, digit I would have been slightly turned in when flexed.

A cast of the brain cavity of the holotype was made under Marsh's supervision, probably during preparation of the skull, allowing Marsh to conclude that the brain "was of medium size, but comparatively much larger than in the herbivorous dinosaurs". The skull bones, however, had been cemented together afterwards, so the accuracy of this cast could not be verified by later studies.

A second, well preserved braincase had been found with specimen MWC 1 in Fruita, Colorado, and was CT-scanned by paleontologists Kent Sanders and David Smith, allowing for reconstructions of the

A cast of the brain cavity of the holotype was made under Marsh's supervision, probably during preparation of the skull, allowing Marsh to conclude that the brain "was of medium size, but comparatively much larger than in the herbivorous dinosaurs". The skull bones, however, had been cemented together afterwards, so the accuracy of this cast could not be verified by later studies.

A second, well preserved braincase had been found with specimen MWC 1 in Fruita, Colorado, and was CT-scanned by paleontologists Kent Sanders and David Smith, allowing for reconstructions of the

All North American ''Ceratosaurus'' finds come from the Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and

All North American ''Ceratosaurus'' finds come from the Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ÎșÎÏαÏ/ÎșÎÏαÏÎżÏ, ' meaning "horn" and ÏαῊÏÎżÏ ' meaning "lizard") was a carnivorous theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

in the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 163.5 ± 1.0 to 145.0 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

(Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxfordian ...

to Tithonian

In the geological timescale, the Tithonian is the latest age of the Late Jurassic Epoch and the uppermost stage of the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 152.1 ± 4 Ma and 145.0 ± 4 Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the K ...

). The genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

was first described in 1884 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 â March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

based on a nearly complete skeleton discovered in Garden Park, Colorado Garden Park is a paleontological site in Fremont County, Colorado, known for its Jurassic dinosaurs and the role the specimens played in the infamous Bone Wars of the late 19th century. Located north of Cañon City, the name originates from the are ...

, in rocks belonging to the Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

is ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis''.

The Garden Park specimen remains the most complete skeleton known from the genus, and only a handful of additional specimens have been described since. Two additional species, ''Ceratosaurus dentisulcatus'' and ''Ceratosaurus magnicornis'', were described in 2000 from two fragmentary skeletons from the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry of Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and from the vicinity of Fruita, Colorado

The City of Fruita is a home rule municipality located in western Mesa County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 13,395 at the 2020 United States Census. Fruita is a part of the Grand Junction, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area a ...

. The validity

Validity or Valid may refer to:

Science/mathematics/statistics:

* Validity (logic), a property of a logical argument

* Scientific:

** Internal validity, the validity of causal inferences within scientific studies, usually based on experiments

** ...

of these additional species has been questioned, however, and all three skeletons possibly represent different growth stages of the same species. In 1999, the discovery of the first juvenile specimen was reported. In 2000, a partial specimen was excavated and described from the LourinhĂŁ Formation

The LourinhĂŁ Formation () is a fossil rich geological formation in western Portugal, named for the municipality of LourinhĂŁ. The formation is mostly Late Jurassic in age (Kimmeridgian/Tithonian), with the top of the formation extending into the ...

of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, RepĂșblica Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, providing evidence for the presence of the genus outside of North America. Fragmentary remains have also been reported from Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, RepĂșblica Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, NeuchĂątel ...

, although their assignment to ''Ceratosaurus'' is currently not accepted by most paleontologists

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palĂŠontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

.

''Ceratosaurus'' was a medium-sized theropod. The original specimen is estimated to be or long, while the specimen described as ''C. dentisulcatus'' was larger, at around long. ''Ceratosaurus'' was characterized by deep jaws that supported proportionally very long, blade-like teeth, a prominent, ridge-like horn on the midline of the snout, and a pair of horns over the eyes. The forelimbs were very short, but remained fully functional; the hand had four fingers. The tail was deep from top to bottom. A row of small osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amp ...

s (skin bones) was present down the middle of the neck, back, and tail. Additional osteoderms were present at unknown positions on the animal's body.

''Ceratosaurus'' gives its name to the Ceratosauria

Ceratosaurs are members of the clade Ceratosauria, a group of dinosaurs defined as all theropods sharing a more recent common ancestor with ''Ceratosaurus'' than with birds. The oldest known ceratosaur, ''Saltriovenator'', dates to the earliest ...

, a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic â that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants â on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

of theropod dinosaurs that diverged early from the evolutionary lineage leading to modern bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s. Within the Ceratosauria, some paleontologists proposed it to be most closely related to ''Genyodectes

''Genyodectes'' ("jaw bite", from the Ancient Greek, Greek words ''genys'' ("jaw") and ''dektes'' ("bite")) is a genus of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) of South America. The holotype material (MLP 26â39, Mus ...

'' from Argentina, which shares the strongly elongated teeth. The geologically older genus ''Proceratosaurus

''Proceratosaurus'' is a genus of carnivore, carnivorous theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) of England. ''Proceratosaurus'' was a small dinosaur, measuring in length and in body mass.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) ''Dinosaurs: ...

'' from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, although originally described as a presumed antecedent of ''Ceratosaurus'', was later found to be unrelated. ''Ceratosaurus'' shared its habitat with other large theropod genera including ''Torvosaurus

''Torvosaurus'' () is a genus of carnivorous megalosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 165 to 148 million years ago during the late Middle and Late Jurassic period (Callovian to Tithonian stages) in what is now Colorado, Portuga ...

'' and ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alluding to ...

'', and it has been suggested that these theropods occupied different ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s to reduce competition. ''Ceratosaurus'' may have preyed upon plant-eating dinosaurs, although some paleontologists suggested that it hunted aquatic prey such as fish. The nasal horn was probably not used as a weapon as was originally suggested by Marsh, but more likely was used solely for display.

History of discovery

Holotype specimen of ''C. nasicornis''

The first specimen, the holotype USNM 4735, was discovered and excavated by farmer Marshall Parker Felch in 1883 and 1884. Found in articulation, with the bones still connected to each other, it was nearly complete, including the skull. Significant missing parts include an unknown number of vertebrae; all but the last ribs of the trunk; the

The first specimen, the holotype USNM 4735, was discovered and excavated by farmer Marshall Parker Felch in 1883 and 1884. Found in articulation, with the bones still connected to each other, it was nearly complete, including the skull. Significant missing parts include an unknown number of vertebrae; all but the last ribs of the trunk; the humeri

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a round ...

(upper arm bones); the distal finger bones of both hands; most of the right fore limb; most of the left hind limb; and most of the feet. The specimen was found encased in hard sandstone; the skull and spine had been heavily distorted during fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ization. The site of discovery, located in the Garden Park area north of Cañon City, Colorado

Cañon City is a home rule municipality that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Fremont County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 17,141 at the 2020 United States Census. Cañon City is the principal city of t ...

, and known as the Felch Quarry 1, is regarded as one of the richest fossil sites of the Morrison Formation

The Morrison Formation is a distinctive sequence of Late Jurassic, Upper Jurassic sedimentary rock found in the western United States which has been the most fertile source of dinosaur fossils in North America. It is composed of mudstone, sandsto ...

. Numerous dinosaur fossils had been recovered from this quarry even before the discovery of ''Ceratosaurus'', most notably a nearly complete specimen of ''Allosaurus'' (USNM 4734) in 1883 and 1884.

After excavation, the specimen was shipped to the Peabody Museum of Natural History

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University is among the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world. It was founded by the philanthropist George Peabody in 1866 at the behest of his nephew Othn ...

in New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, where it was studied by Marsh, who described it as the new genus and species ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' in 1884. The name ''Ceratosaurus'' may be translated as "horn lizard" (from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, '' ''â"horn" and /'â"lizard"), and ''nasicornis'' with "nose horn" (from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''nasus''â"nose" and ''cornu''â"horn"). Given the completeness of the specimen, the newly described genus was at the time the best-known theropod discovered in America. In 1898 and 1899, the specimen was transferred to the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7 ...

in Washington, DC

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

, together with many other fossils originally described by Marsh. Only part of this material was fully prepared when it arrived in Washington; subsequent preparation lasted from 1911 to the end of 1918. Packaging and shipment from New Haven to Washington caused some damage to the ''Ceratosaurus'' specimen. In 1920, Charles Gilmore published an extensive redescription of this and the other theropod specimens received from New Haven, including the nearly complete ''Allosaurus'' specimen recovered from the same quarry.

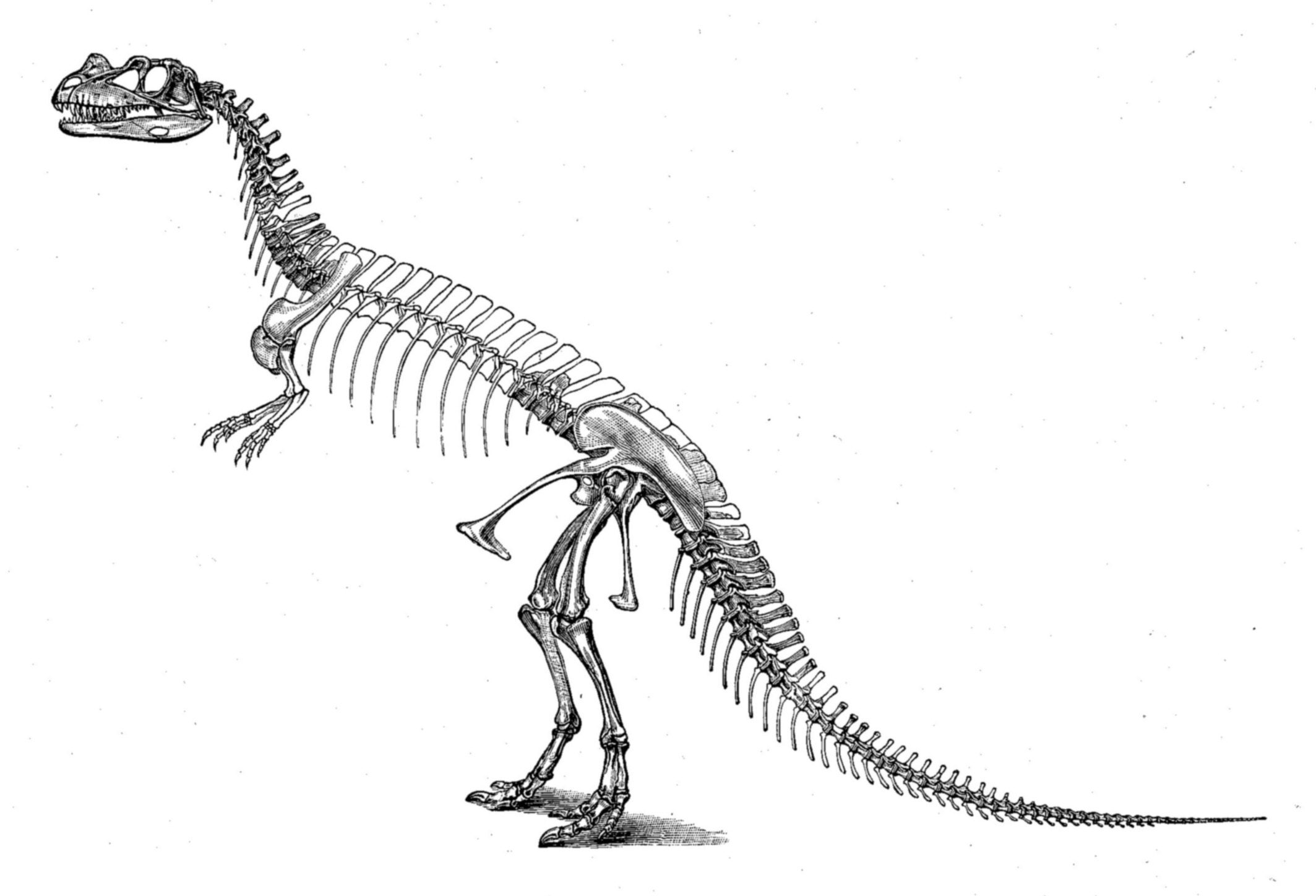

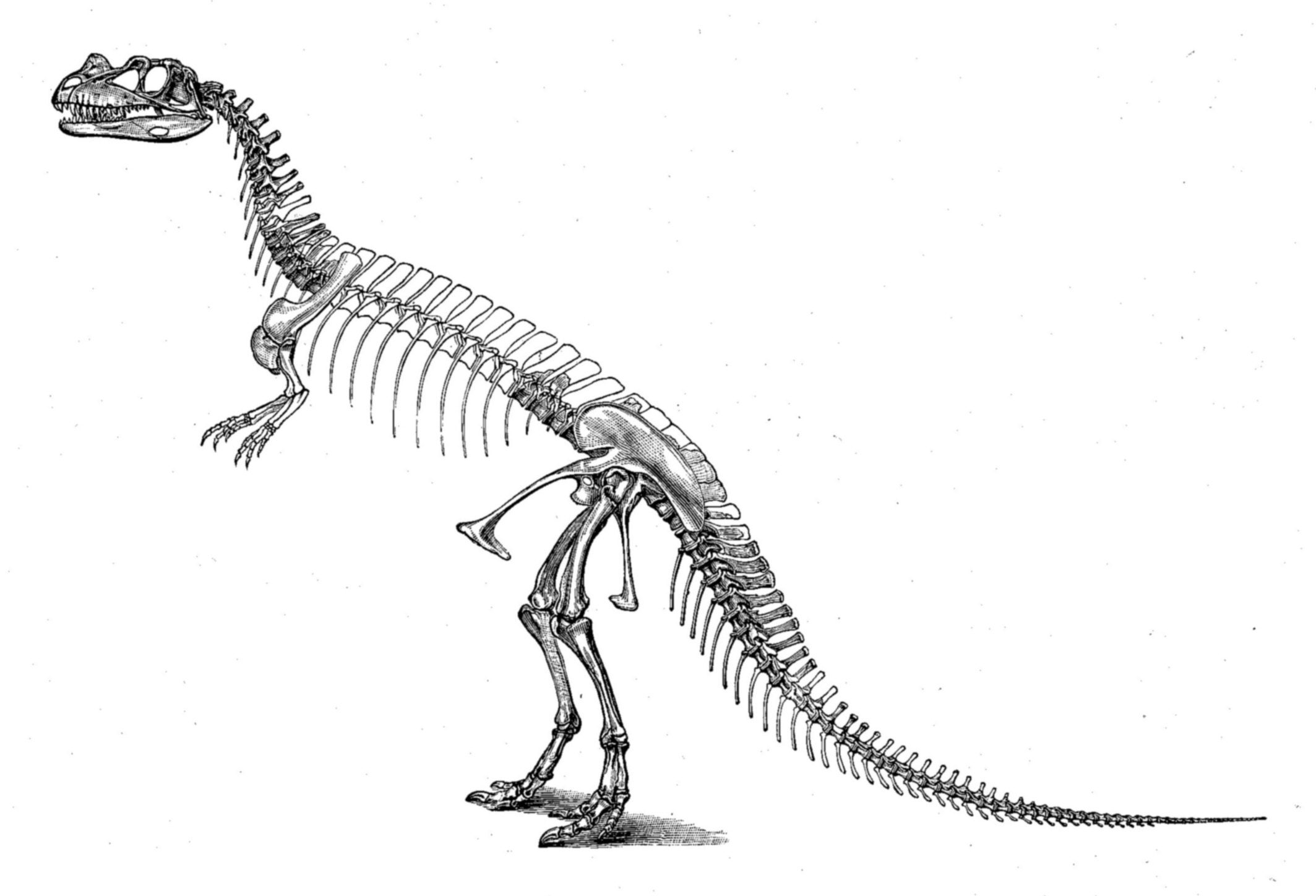

In an 1892 paper, Marsh published the first skeletal reconstruction of ''Ceratosaurus'', which depicts the animal at in length and in height. As noted by Gilmore in 1920, the trunk was depicted much too long in this reconstruction, incorporating at least six dorsal vertebrae too many. This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of

In an 1892 paper, Marsh published the first skeletal reconstruction of ''Ceratosaurus'', which depicts the animal at in length and in height. As noted by Gilmore in 1920, the trunk was depicted much too long in this reconstruction, incorporating at least six dorsal vertebrae too many. This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of Charles R. Knight

Charles Robert Knight (October 21, 1874 â April 15, 1953) was an American wildlife and paleoartist best known for his detailed paintings of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. His works have been reproduced in many books and are currently ...

, but not published until 1920. A more accurate life reconstruction, published in 1901, was produced by Joseph M. Gleeson, again under Knight's supervision. The holotype was mounted by Gilmore in 1910 and 1911, and since then was exhibited at the National Museum of Natural History. Most early reconstructions show ''Ceratosaurus'' in an upright posture, with the tail dragging on the ground. Gilmore's mount of the holotype, in contrast, was ahead of its time: Inspired by the upper thigh bones, which were found angled against the lower leg, he depicted the mount as a running animal with a horizontal rather than upright posture and a tail that did not make contact with the ground. Because of the strong flattening of the fossils, Gilmore mounted the specimen not as a free-standing skeleton, but as a bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the ...

within an artificial wall. With the bones being partly embedded in a plaque, scientific access was limited. In the course of the renovation of the museum's dinosaur exhibition between 2014 and 2019, the specimen was dismantled and freed from the encasing plaque. In the new exhibition, which is set to open in 2019, the mount is planned to be replaced by a free-standing cast, and the original bones to be stored in the museum collection to allow full access for scientists.

Additional finds in North America

After the discovery of the holotype of ''C. nasicornis'', a significant ''Ceratosaurus'' find was not made until the early 1960s, when paleontologist James Madsen and his team unearthed a fragmentary, disarticulated skeleton including the skull (UMNH VP 5278) in the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry in Utah. This find represents one of the largest-known ''Ceratosaurus'' specimens. A second, articulated specimen including the skull (MWC 1) was discovered in 1976 by Thor Erikson, the son of paleontologist Lance Erikson, nearFruita, Colorado

The City of Fruita is a home rule municipality located in western Mesa County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 13,395 at the 2020 United States Census. Fruita is a part of the Grand Junction, CO Metropolitan Statistical Area a ...

. A fairly complete specimen, it lacks lower jaws, forearms and gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these ...

. The skull, although reasonably complete, was found disarticulated and is strongly flattened sidewards. Although a large individual, it had not yet reached adult size, as indicated by open sutures between the skull bones. Scientifically accurate three-dimensional reconstructions of the skull for use in museum exhibits were produced using a complicated process including molding and casting of the individual original bones, correction of deformities, reconstruction of missing parts, assembly of the bone casts into their proper position, and painting to match the original color of the bones.

Both the Fruita and Cleveland-Lloyd specimens were described by Madsen and Samuel Paul Welles

Samuel Paul Welles (November 9, 1907 â August 6, 1997) was an American palaeontologist. Welles was a research associate at the Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, Berkeley. He took part in excavations at the Placerias Quarry in ...

in a 2000 monograph, with the Utah specimen being assigned to the new species ''C. dentisulcatus'' and the Colorado specimen to the new species ''C. magnicornis''. The name ''dentisulcatus'' refers to the parallel grooves present on the inner sides of the premaxillary teeth and the first three teeth of the lower jaw in that specimen; ''magnicornis'' points to the larger nasal horn. The validity

Validity or Valid may refer to:

Science/mathematics/statistics:

* Validity (logic), a property of a logical argument

* Scientific:

** Internal validity, the validity of causal inferences within scientific studies, usually based on experiments

** ...

of both species, however, was questioned in subsequent publications. Brooks Britt and colleagues, in 2000, claimed that the ''C. nasicornis'' holotype was in fact a juvenile individual, with the two larger species representing the adult state of a single species. Oliver Rauhut, in 2003, and Matthew Carrano and Scott Sampson, in 2008, considered the anatomical differences cited by Madsen and Welles to support these additional species to represent ontogenetic

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the st ...

(age-related) or individual variation.

A further specimen (BYUVP 12893) was discovered in 1992 in the Agate Basin Quarry southeast of Moore, Utah

Moore is an unincorporated community in west central Emery County, Utah, United States, at the edge of the San Rafael Swell.

Description

Moore is an unincorporated community or populated place (Class Code U6) located in Emery County at latitude ...

, but still awaits description. The specimen, considered the largest known from the genus, includes the front half of a skull, seven fragmentary pelvic dorsal vertebrae, and an articulated pelvis and sacrum. In 1999, Britt reported the discovery of a ''Ceratosaurus'' skeleton belonging to a juvenile individual. Discovered in Bone Cabin Quarry

Bone Cabin Quarry is a dinosaur quarry that lay approximately northwest of Laramie, Wyoming near historic Como Bluff. During the summer of 1897 Walter Granger, a paleontologist from the American Museum of Natural History, came upon a hillside li ...

in Wyoming, it is 34% smaller than the ''C. nasicornis'' holotype and consists of a complete skull as well as 30% of the remainder of the skeleton including a complete pelvis.

Besides these five skeletal finds, fragmentary ''Ceratosaurus'' remains have been reported from various localities from stratigraphic zones 2 and 4-6 of the Morrison Formation, including some of the major fossil sites of the formation. Dinosaur National Monument

Dinosaur National Monument is an American national monument located on the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains on the border between Colorado and Utah at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Although most of the monument area is in ...

, Utah, yielded an isolated right premaxilla (specimen number DNM 972); a large shoulder blade (scapulocoracoid) was reported from Como Bluff

Como Bluff is a long ridge extending eastâwest, located between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow, Wyoming. The ridge is an anticline, formed as a result of compressional geological folding. Three geological formations, the Sundance, t ...

in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. Another specimen stems from the Dry Mesa Quarry

The Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry is situated in southwestern Colorado, United States, near the town of Delta. Its geology forms a part of the Morrison Formation and has famously yielded a great diversity of animal remains from the Jurassic Period, amon ...

, Colorado, and includes a left scapulocoracoid, as well as fragments of vertebrae and limb bones. In Mygatt Moore Quarry, Colorado, the genus is known from teeth.

Finds outside North America

From 1909 to 1913, German expeditions of theBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

Museum fĂŒr Naturkunde

The Natural History Museum (german: Museum fĂŒr Naturkunde) is a natural history museum located in Berlin, Germany. It exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history and in such domain it is one of three major muse ...

uncovered a diverse dinosaur fauna from the Tendaguru Formation

The Tendaguru Formation, or Tendaguru Beds are a highly fossiliferous formation and LagerstÀtte located in the Lindi Region of southeastern Tanzania. The formation represents the oldest sedimentary unit of the Mandawa Basin, overlying Neoproter ...

in German East Africa

German East Africa (GEA; german: Deutsch-Ostafrika) was a German colony in the African Great Lakes region, which included present-day Burundi, Rwanda, the Tanzania mainland, and the Kionga Triangle, a small region later incorporated into Mozam ...

, in what is now Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

. Although commonly considered the most important African dinosaur locality, large theropod dinosaurs are only known through few and very fragmentary remains. In 1920, German paleontologist Werner Janensch

Werner Ernst Martin Janensch (11 November 1878 – 20 October 1969) was a German paleontologist and geologist.

Biography

Janensch was born at Herzberg (Elster).

In addition to Friedrich von Huene, Janensch was probably Germany's most imp ...

assigned several dorsal vertebrae from the quarry "TL" to ''Ceratosaurus'', as ''Ceratosaurus'' sp. (of uncertain species). In 1925, Janensch named a new species of ''Ceratosaurus'', ''C. roechlingi'', based on fragmentary remains from the quarry "Mw" encompassing a quadrate bone, a fibula, fragmentary caudal vertebrae, and other fragments. This specimen stems from an individual substantially larger than the ''C. nasicornis'' holotype.

In their 2000 monograph, Madsen and Welles confirmed the assignment of these finds to ''Ceratosaurus''. In addition, they ascribed several teeth to the genus, which had originally been described by Janensch as a possible species of '' Labrosaurus'', ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi''. Other authors questioned the assignment of any of the Tendaguru finds to ''Ceratosaurus'', noting that none of these specimens displays features diagnostic for that genus. In 2011, Rauhut found both ''C. roechlingi'' and ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi'' to be possible ceratosaurids, but found them to be not diagnostic at genus level and therefore designated them as ''

In their 2000 monograph, Madsen and Welles confirmed the assignment of these finds to ''Ceratosaurus''. In addition, they ascribed several teeth to the genus, which had originally been described by Janensch as a possible species of '' Labrosaurus'', ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi''. Other authors questioned the assignment of any of the Tendaguru finds to ''Ceratosaurus'', noting that none of these specimens displays features diagnostic for that genus. In 2011, Rauhut found both ''C. roechlingi'' and ''Labrosaurus'' (?) ''stechowi'' to be possible ceratosaurids, but found them to be not diagnostic at genus level and therefore designated them as ''nomina dubia

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium'' it may be impossible to determine whether a s ...

'' (doubtful names). In 1990, Timothy Rowe and Jacques Gauthier

Jacques Armand Gauthier (born June 7, 1948 in New York City) is an American vertebrate paleontologist, comparative morphologist, and systematist, and one of the founders of the use of cladistics in biology.

Life and career

Gauthier is the so ...

mentioned yet another ''Ceratosaurus'' species from Tendaguru, ''Ceratosaurus ingens'', which purportedly was erected by Janensch in 1920 and was based on 25 isolated, very large teeth up to in length. However, Janensch assigned this species to ''Megalosaurus

''Megalosaurus'' (meaning "great lizard", from Greek , ', meaning 'big', 'tall' or 'great' and , ', meaning 'lizard') is an extinct genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaurs of the Middle Jurassic period (Bathonian stage, 166 million years a ...

'', not to ''Ceratosaurus''; therefore, this name might be a simple copying error. Rauhut, in 2011, showed that ''Megalosaurus ingens'' was not closely related to either ''Megalosaurus'' or ''Ceratosaurus'', but possibly represents a carcharodontosaurid

Carcharodontosauridae (carcharodontosaurids; from the Greek ÎșαÏÏαÏÎżÎŽÎżÎœÏÏÏαÏ

ÏÎżÏ, ''carcharodontĂłsauros'': "shark-toothed lizards") is a group of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. In 1931, Ernst Stromer named Carcharodontosauridae ...

, instead.

In 2000 and 2006, paleontologists led by OctĂĄvio Mateus

OctĂĄvio Mateus (born 1975) is a Portuguese dinosaur paleontologist and biologist Professor of Paleontology at the Faculdade de CiĂȘncias e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He graduated in Universidade de Ăvora and received his PhD at U ...

described a find from the LourinhĂŁ Formation

The LourinhĂŁ Formation () is a fossil rich geological formation in western Portugal, named for the municipality of LourinhĂŁ. The formation is mostly Late Jurassic in age (Kimmeridgian/Tithonian), with the top of the formation extending into the ...

in central-west Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, RepĂșblica Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

(ML 352) as a new specimen of ''Ceratosaurus'', consisting of a right femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

(upper thigh bone), a left tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

(shin bone), and several isolated teeth recovered from the cliffs of ValmitĂŁo beach, between the municipalities LourinhĂŁ

LourinhĂŁ () is a municipality in the District of Lisbon, in the Oeste Subregion of Portugal. The population in 2011 was 25,735, in an area of 147.17 kmÂČ. The seat of the municipality is the town of LourinhĂŁ, with a population of 8,800 inhab ...

and Torres Vedras

Torres Vedras () is a municipality in the Portuguese district of Lisbon, approximately north of the capital Lisbon in the Oeste region, in the Centro of Portugal. The population was 83,075, in an area of .

History

In 1148, Afonso I took th ...

. The bones were found embedded in yellow to brown, fine-grained sandstones, which were deposited by rivers as floodplain deposits and belong to the lower levels of the Porto Novo Member, which is thought to be late Kimmeridgian

In the geologic timescale, the Kimmeridgian is an age in the Late Jurassic Epoch and a stage in the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 157.3 ± 1.0 Ma and 152.1 ± 0.9 Ma (million years ago). The Kimmeridgian follows the Oxfordian ...

in age. Additional bones of this individual (SHN (JJS)-65), including a left femur, a right tibia, and a partial left fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is ...

(calf bone), were since exposed due to progressing cliff erosion. Although initially part of a private collection, these additional elements became officially curated after the private collection was donated to the Sociedade de HistĂłria Natural in Torres Vedras, and were described in detail in 2015. The specimen was ascribed to the species ''Ceratosaurus dentisulcatus'' by Mateus and colleagues in 2006. A 2008 review by Carrano and Sampson confirmed the assignment to ''Ceratosaurus'', but concluded that the assignment to any specific species is not possible at present. In 2015, Elisabete Malafaia and colleagues, who questioned the validity of ''C. dentisulcatus'', assigned the specimen to ''Ceratosaurus'' aff. ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis''.

Other reports include a single tooth found in Moutier

Moutier () is a municipality in Switzerland. Currently, the town belongs to the Jura bernois administrative district of the canton of Bern. On 28 March 2021, the population voted to secede from the canton of Bern and join the Canton of Jura; the ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, NeuchĂątel ...

. Originally named by Janensch in 1920 as ''Labrosaurus meriani'', the tooth was later assigned ''Ceratosaurus'' sp. (of unknown species) by Madsen and Welles. In 2008, MatĂas Soto and Daniel Perea described teeth from the TacuarembĂł Formation

The TacuarembĂł Formation is a Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) geologic formation of the eponymous department in northern Uruguay. The fluvial to lacustrine sandstones, siltstones and mudstones preserve ichnofossils, turtles, crocodylomorphs, fish a ...

in Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, RepĂșblica Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, including a presumed premaxillary tooth crown. This shows vertical striations on its inner side and lacks denticles on its front edge; these features are, in this combination, only known from ''Ceratosaurus''. The authors, however, stressed that an assignment to ''Ceratosaurus'' is infeasible as the remains are scant, and furthermore note that the assignment of the European and African material to ''Ceratosaurus'' has to be viewed with caution. In 2020, Soto and colleagues described additional ''Ceratosaurus'' teeth from the same formation that further support their earlier interpretation.

Description

body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

typical for large theropod dinosaurs. A biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' a ...

, it moved on powerful hind legs, while its arms were reduced in size. Specimen USNM 4735, the first discovered skeleton and holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

of ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'', was an individual or in length according to separate sources. Whether this animal was fully grown is not clear. Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 â March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

, in 1884, suggested that this specimen weighed about half as much as the contemporary ''Allosaurus

''Allosaurus'' () is a genus of large carnosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 145 million years ago during the Late Jurassic epoch (Kimmeridgian to late Tithonian). The name "''Allosaurus''" means "different lizard" alluding to ...

''. In more recent accounts, this was revised to , , or . Three additional skeletons discovered in the latter half of the 20th century were substantially larger. The first of these, UMNH VP 5278, was informally estimated by James Madsen to have been around long, but was later estimated at in length. Its weight was calculated at , , and in separate works. The second skeleton, MWC 1, was somewhat smaller than UMNH VP 5278 and might have been in weight. The third, yet undescribed, specimen BYUVP 12893 was claimed to be the largest yet discovered, although estimates have not been published. Another specimen (ML 352), discovered in Portugal in 2000, was estimated at in length and in body mass, which is also estimated as the maximum adult size of ''C. nasicornis''.

Skull

file:Osteology of the carnivorous Dinosauria in the United States National museum BHL40623209 edited.jpg, left, alt=Charles Gilmore's reconstruction of the skull in side and top view , Diagram of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype skull in top and side view by Charles Gilmore, 1920: This reconstruction is now thought to be too wide in top view. The skull was quite large in proportion to the rest of its body. It measures in length in the ''C. nasicornis'' holotype, measured from the tip of the snout to the , which connects to the first cervical vertebra. The width of this skull is difficult to reconstruct, as it is heavily distorted, and Gilmore's 1920 reconstruction was later found to be too wide. The fairly complete skull of specimen MWC 1 was estimated to have been in length and in width; this skull was somewhat more elongated than that of the holotype. The back of the skull was more lightly built than in some other larger theropods due to extensive skull openings, yet the jaws were deep to support the proportionally large teeth. Thelacrimal bone

The lacrimal bone is a small and fragile bone of the facial skeleton; it is roughly the size of the little fingernail. It is situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. It has two surfaces and four borders. Several bony landmarks of ...

formed not only the back margin of the antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among extant archosaurs, birds ...

, a large opening between eye and , but also part of its upper margin, unlike in members of the related Abelisauridae

Abelisauridae (meaning "Abel's lizards") is a family (or clade) of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Abelisaurids thrived during the Cretaceous period, on the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana, and today their fossil remains are found ...

. The quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms upper ...

, which was connected to the lower jaw at its bottom end to form the jaw joint, was inclined so that the jaw joint was displaced backwards in relation to the occipital condyle. This also led to a broadening of the base of the lateral temporal fenestra, a large opening behind the eyes.

The most distinctive feature was a prominent horn situated on the skull midline behind the bony nostrils, which was formed from fused protuberances of the left and right nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

s. Only the bony horn core is known from fossilsâin the living animal, this core would have supported a keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

ous sheath. While the base of the horn core was smooth, its upper two-thirds were wrinkled and lined with groves that would have contained blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

s when alive. In the holotype, the horn core is long and wide at its base, but quickly narrows to only further up; it is in height. It is longer and lower in the skull of MWC 1. In the living animal, the horn would likely have been more elongated due to its keratinous sheath. Behind the nasal horn, the nasal bones formed an oval groove; both this groove and the nasal horn serve as features to distinguish ''Ceratosaurus'' from related genera. In addition to the large nasal horn, ''Ceratosaurus'' possessed smaller, semicircular, bony ridges in front of each eye, similar to those of ''Allosaurus''. These ridges were formed by the lacrimal bones. In juveniles, all three horns were smaller than in adults, and the two halves of the nasal horn core were not yet fused.

premaxillary bone

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

s, which formed the tip of the snout, contained merely three teeth on each side, less than in most other theropods. The of the upper jaw were lined with 15 blade-like teeth on each side in the holotype. The first eight of these teeth were very long and robust, but from the ninth tooth onward they gradually decrease in size. As typical for theropods, they featured finely edges, which in the holotype contained some 10 denticles per . Specimen MWC 1 merely showed 11 to 12, and specimen UMNH VP 5278 12 teeth in each maxilla; the teeth were more robust and more recurved in the latter specimen. In all specimens, the tooth crown

In dentistry, crown refers to the anatomical area of teeth, usually covered by tooth enamel, enamel. The crown is usually visible in the mouth after tooth development, developing below the gingiva and then tooth eruption, erupting into place. ...

s of the upper jaws were exceptionally long. In specimen UMNH VP 5278, they measured up to in length, which is equal to the minimum height of the lower jaw. In the holotype, they are in length, which even surpasses the minimum height of the lower jaw. In other theropods, a comparable tooth length is only known from the possibly closely related ''Genyodectes

''Genyodectes'' ("jaw bite", from the Ancient Greek, Greek words ''genys'' ("jaw") and ''dektes'' ("bite")) is a genus of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) of South America. The holotype material (MLP 26â39, Mus ...

''. In contrast, several members of the Abelisauridae feature very short tooth crowns. In the holotype, each half of the , the tooth-bearing bone of the , was equipped with 15 teeth, which are, however, poorly preserved. Both specimens MWC 1 and UMNH VP 5278 show only 11 teeth in each dentary, which were, as shown by the latter specimen, slightly straighter and less sturdy than those of the upper jaw.

Postcranial skeleton

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the spine of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype. At least 20 vertebrae formed the neck and back in front of the

The exact number of vertebrae is unknown due to several gaps in the spine of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype. At least 20 vertebrae formed the neck and back in front of the sacrum

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

. In the middle portion of the neck, the (bodies) of the vertebrae were as long as they were tall, while in the front and rear portions of the neck, the centra were shorter than their height. The upwards projecting were comparatively large, and in the dorsal (back) vertebrae, were as tall as the vertebral centra were long. The sacrum, consisting of six fused , was arched upwards, with its vertebral centra strongly reduced in height in its middle portion, as is the case in some other ceratosauria

Ceratosaurs are members of the clade Ceratosauria, a group of dinosaurs defined as all theropods sharing a more recent common ancestor with ''Ceratosaurus'' than with birds. The oldest known ceratosaur, ''Saltriovenator'', dates to the earliest ...

ns. The tail comprised around 50 and was about half of the animal's total length; in the holotype, it was estimated at . The tail was deep from top to bottom due to its high neural spines and elongated chevrons

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* ''Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock lay ...

, bones located below the vertebral centra. As in other dinosaurs, it counterbalanced the body and contained the massive caudofemoralis The caudofemoralis (from the Latin ''cauda'', tail and ''femur'', thighbone) is a muscle found in the pelvic limb of mostly all animals possessing a tail. It is thus found in nearly all tetrapods.

Location

The caudofemoralis spans plesiomorphi ...

muscle, which was responsible for forward thrust during locomotion, pulling the upper thigh backwards when contracted.

The

The scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eithe ...

(shoulder blade) was fused with the coracoid

A coracoid (from Greek ÎșÏÏαΟ, ''koraks'', raven) is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is prese ...

, forming a single bone without any visible demarcation between the two original elements. The ''C. nasicornis'' holotype was found with an articulated left fore limb including an incomplete (hand). Although during preparation, a cast had been made of the fossil beforehand to document the original relative positions of the bones. Carpal bones

The carpal bones are the eight small bones that make up the wrist (or carpus) that connects the hand to the forearm. The term "carpus" is derived from the Latin carpus and the Greek ÎșαÏÏÏÏ (karpĂłs), meaning "wrist". In human anatomy, th ...

were not known from any specimen, leading some authors to suggest that they were lost in the genus. In a 2016 paper, Matthew Carrano and Jonah Choiniere suggested that one or more cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck and ...

(not bony) carpals were probably present, as indicated by a gap present between the forearm bones and the metacarpals, as well as by the surface texture within this gap seen in the cast. In contrast to most more-derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''DĂ©rive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*DĂ©rive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

theropods, which showed only three digits on each manus (digits IâIII), ''Ceratosaurus'' retained four digits, with digit IV reduced in size. The first and fourth metacarpals

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus form the intermediate part of the skeleton, skeletal hand located between the phalanges of the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist, which forms the connection to the forearm. The metacarpa ...

were short, while the second was slightly longer than the third. The metacarpus and especially the first phalanges

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

were proportionally very short, unlike in most other basal theropods. Only the first phalanges of digits II, III, and IV are preserved in the holotype; the total number of phalanges and ungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropods and horned dinosaurs. A claw is a highly modified ungual ...

s (claw bones) is unknown. The anatomy of metacarpal I indicates that phalanges had originally been present on this digit, as well. The pes

Pes (Latin for "foot") or the acronym PES may refer to:

Pes

* Pes (unit), a Roman unit of length measurement roughly corresponding with a foot

* Pes or podatus, a

* Pes (rural locality), several rural localities in Russia

* Pes (river), a river ...

(foot) consisted of three weight-bearing digits, numbered IIâIV. Digit I, which in theropods is usually reduced to a dewclaw

A dewclaw is a digit â vestigial in some animals â on the foot of many mammals, birds, and reptiles (including some extinct orders, like certain theropods). It commonly grows higher on the leg than the rest of the foot, such that in digit ...

that does not touch the ground, is not preserved in the holotype. Marsh, in his original 1884 description, assumed that this digit was lost in ''Ceratosaurus'', but Charles Gilmore, in his 1920 monograph, noted an attachment area on the second metatarsal

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the med ...

demonstrating the presence of this digit.

Uniquely among theropods, ''Ceratosaurus'' possessed small, elongated, and irregularly formed osteoderm

Osteoderms are bony deposits forming scales, plates, or other structures based in the dermis. Osteoderms are found in many groups of extant and extinct reptiles and amphibians, including lizards, crocodilians, frogs, temnospondyls (extinct amp ...

s (skin bones) along the midline of its body. Such osteoderms have been found above the neural spines of cervical vertebrae 4 and 5, as well as caudal vertebrae 4 to 10, and probably formed a continuous row that might have extended from the base of the skull to most of the tail. As suggested by Gilmore in 1920, their position in the rock matrix likely reflects their exact position in the living animal. The osteoderms above the tail were found separated from the neural spines by to , possibly accounting for skin and muscles present in between, while those of the neck were much closer to the neural spines. Apart from the body midline, the skin contained additional osteoderms, as indicated by a by large, roughly quadrangular plate found together with the holotype; the position of this plate on the body is unknown. Specimen UMNH VP 5278 was also found with a number of osteoderms, which have been described as amorphous in shape. Although most of these were found at most 5 m apart from the skeleton, they were not directly associated with any vertebrae, unlike in the ''C. nasicornis'' holotype, so their original position on the body cannot be inferred from this specimen.

Classification

In his original description of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype and subsequent publications, Marsh noted a number of characteristics that were unknown in all other theropods known at the time. Two of these features, the fused pelvis and fused metatarsus, were known from modern-day birds, and according to Marsh, clearly demonstrate the close relationship between the latter and dinosaurs. To set the genus apart from ''Allosaurus'', ''Megalosaurus'', and

In his original description of the ''Ceratosaurus nasicornis'' holotype and subsequent publications, Marsh noted a number of characteristics that were unknown in all other theropods known at the time. Two of these features, the fused pelvis and fused metatarsus, were known from modern-day birds, and according to Marsh, clearly demonstrate the close relationship between the latter and dinosaurs. To set the genus apart from ''Allosaurus'', ''Megalosaurus'', and coelurosaurs

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, tyrann ...

, Marsh made ''Ceratosaurus'' the only member of both a new family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

, the Ceratosauridae

Ceratosauridae is an extinct family of theropod dinosaurs belonging to the infraorder Ceratosauria. The family's type genus, ''Ceratosaurus'', was first found in Jurassic rocks from North America. Ceratosauridae is made up of the genera ''Cerat ...

, and a new infraorder

Order ( la, ordo) is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and ...

, the Ceratosauria. This was questioned in 1892 by Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 â April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested ...

, Marsh's rival in the Bone Wars

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Acade ...

, who argued that distinctive features such as the nasal horn merely showed that ''C. nasicornis'' was a distinct species, but were insufficient to justify a distinct genus. Consequently, he assigned ''C. nasicornis'' to the genus ''Megalosaurus'', creating the new combination ''Megalosaurus nasicornis''.

Although ''Ceratosaurus'' was retained as a distinct genus in all subsequent analyses, its relationships remained controversial during the following century. Both the Ceratosauridae and Ceratosauria were not widely accepted, with only few and poorly known additional members identified. Over the years, separate authors classified ''Ceratosaurus'' within the Deinodontidae

Tyrannosauridae (or tyrannosaurids, meaning "tyrant lizards") is a family (biology), family of coelurosaurian Theropoda, theropod dinosaurs that comprises two subfamilies containing up to thirteen genus, genera, including the eponymous ''Tyrannos ...

, the Megalosauridae

Megalosauridae is a monophyletic family of carnivorous theropod dinosaurs within the group Megalosauroidea. Appearing in the Middle Jurassic, megalosaurids were among the first major radiation of large theropod dinosaurs. They were a relatively ...

, the Coelurosauria

Coelurosauria (; from Greek, meaning "hollow tailed lizards") is the clade containing all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to carnosaurs.

Coelurosauria is a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs that includes compsognathids, tyrann ...

, the Carnosauria

Carnosauria is an extinct large group of predatory dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Starting from the 1990s, scientists have discovered some very large carnosaurs in the carcharodontosaurid family, such as ''Gig ...

, and the Deinodontoidea. In his 1920 revision, Gilmore argued that the genus was the most basal theropod known from after the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

, so not closely related to any other contemporary theropod known at that time; it thus warrants its own family, the Ceratosauridae. It was not until the establishment of cladistic analysis

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived chara ...

in the 1980s, however, that Marsh's original claim of the Ceratosauria as a distinct group gained ground. In 1985, the newly discovered South American genera ''Abelisaurus

''Abelisaurus'' (; "Abel's lizard") is a genus of predatory abelisaurid theropod dinosaur alive during the Late Cretaceous Period (Campanian) of what is now South America. It was a bipedal carnivore that probably reached about in length, althou ...

'' and ''Carnotaurus

''Carnotaurus'' (; ) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous period, probably sometime between 71 and 69 million years ago. The only species is ''Carnotaurus sastrei''. Known from a single well-p ...

'' were found to be closely related to ''Ceratosaurus''. Gauthier, in 1986, recognized the Coelophysoidea

Coelophysoidea were common dinosaurs of the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods. They were widespread geographically, probably living on all continents. Coelophysoids were all slender, carnivorous forms with a superficial similarity to the ...

to be closely related to ''Ceratosaurus'', although this clade falls outside of Ceratosauria in most recent analyses. Many additional members of the Ceratosauria have been recognized since.

The Ceratosauria split off early from the evolutionary line leading to modern birds, thus is considered basal within theropods. Ceratosauria itself contains a group of derived (nonbasal) members of the families Noasauridae

Noasauridae is an extinct family of theropod dinosaurs belonging to the group Ceratosauria. They were closely related to the short-armed abelisaurids, although most noasaurids had much more traditional body types generally similar to other ther ...

and Abelisauridae

Abelisauridae (meaning "Abel's lizards") is a family (or clade) of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaurs. Abelisaurids thrived during the Cretaceous period, on the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana, and today their fossil remains are found ...

, which are bracketed within the clade Abelisauroidea

Abelisauroidea is typically regarded as a Cretaceous group, though the earliest abelisauridae remains are known from the Middle Jurassic of Argentina (classified as the species Eoabelisaurus mefi) and possibly Madagascar (fragmentary remains of ...

, as well as a number of basal members, such as ''Elaphrosaurus

''Elaphrosaurus'' ( ) is a genus of ceratosaurian theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 154 to 150 million years ago during the Late Jurassic Period in what is now Tanzania in Africa. ''Elaphrosaurus'' was a medium-sized but lightly built m ...

'', ''Deltadromeus

''Deltadromeus'' (meaning "delta runner") is a genus of theropod dinosaur from Northern Africa. It had long, unusually slender hind limbs for its size, suggesting that it was a swift runner. The skull is not known. One fossil specimen of a sin ...

'', and ''Ceratosaurus''. The position of ''Ceratosaurus'' within basal ceratosaurians is under debate. Some analyses considered ''Ceratosaurus'' as the most derived of the basal members, forming the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

of the Abelisauroidea. Oliver Rauhut, in 2004, proposed ''Genyodectes'' as the sister taxon of ''Ceratosaurus'', as both genera are characterized by exceptionally long teeth in the upper jaw. Rauhut grouped ''Ceratosaurus'' and ''Genyodectes'' within the family Ceratosauridae, which was followed by several later accounts.

Shuo Wang and colleagues, in 2017, concluded that the Noasauridae were not nested within the Abelisauroidea as was previously assumed, but instead were more basal than ''Ceratosaurus''. Because noasaurids had been used as a fix point to define the clades Abelisauroidea and Abelisauridae, these clades would consequently include many more taxa per definition, including ''Ceratosaurus''. In a subsequent 2018 study, Rafael Delcourt accepted these results, but pointed out that, as a consequence, the Abelisauroidea would need to be replaced by the older synonym Ceratosauroidea, which was hitherto rarely used. For the Abelisauridae, Delcourt proposed a new definition that excludes ''Ceratosaurus'', allowing for using the name its traditional sense. Wang and colleagues furthermore found that ''Ceratosaurus'' and ''Genyodectes'' form a clade with the Argentinian genus ''Eoabelisaurus

''Eoabelisaurus'' () is a genus of abelisaurid theropod dinosaur from the Lower Jurassic CañadĂłn Asfalto Formation of the CañadĂłn Asfalto Basin in Argentina, South America. The generic name combines a Greek ጠÏÏ, (''eos''), "dawn", with th ...

''. Delcourt used the name Ceratosauridae to refer to this same clade, and suggested to define the Ceratosauridae as containing all taxa that are more closely related to ''Ceratosaurus'' than to the abelisaurid ''Carnotaurus

''Carnotaurus'' (; ) is a genus of theropod dinosaur that lived in South America during the Late Cretaceous period, probably sometime between 71 and 69 million years ago. The only species is ''Carnotaurus sastrei''. Known from a single well-p ...

''.

The following

The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

showing the relationships of ''Ceratosaurus'' is based on the phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek ÏÏ

λΟ/ ÏáżŠÎ»ÎżÎœ [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:ÎłÎ”ÎœÎ”ÏÎčÎșÏÏ, ÎłÎ”ÎœÎ”ÏÎčÎșÏÏ [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis conducted by Diego Pol and Oliver Rauhut in 2012:

A skull from the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second epoch of the Jurassic Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relatively rare, but geological formations co ...

of England apparently displays a nasal horn similar to that of ''Ceratosaurus''. In 1926, Friedrich von Huene

Friedrich von Huene, born Friedrich Richard von Hoinigen, (March 22, 1875 – April 4, 1969) was a German paleontologist who renamed more dinosaurs in the early 20th century than anyone else in Europe. He also made key contributions about v ...

described this skull as ''Proceratosaurus

''Proceratosaurus'' is a genus of carnivore, carnivorous theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) of England. ''Proceratosaurus'' was a small dinosaur, measuring in length and in body mass.Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) ''Dinosaurs: ...

'' (meaning "before ''Ceratosaurus''"), assuming that it was an antecedent of the Late Jurassic ''Ceratosaurus''. Today, ''Proceratosaurus'' is considered a basal member of the Tyrannosauroidea

Tyrannosauroidea (meaning 'tyrant lizard forms') is a superfamily (or clade) of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs that includes the family Tyrannosauridae as well as more basal relatives. Tyrannosauroids lived on the Laurasian supercontinent b ...

, a much more derived clade of theropod dinosaurs; the nasal horn therefore would have had evolved independently in both genera. Oliver Rauhut and colleagues, in 2010, grouped ''Proceratosaurus'' within its own family, the Proceratosauridae

Proceratosauridae is a Family (biology), family or clade of Tyrannosauroidea, tyrannosauroid theropod dinosaurs from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous.

Distinguishing features

Unlike the advanced Tyrannosauridae, tyrannosaurids but s ...

. These authors also noted that the nasal horn is incompletely preserved, opening the possibility that it represented the foremost portion of a more extensive head crest, as seen in some other proceratosaurids such as ''Guanlong

''Guanlong'' (ć éŸ) is a genus of extinct proceratosaurid tyrannosauroid from the Late Jurassic of China. The taxon was first described in 2006 by Xu Xing ''et al.'', who found it to represent a new taxon related to ''Tyrannosaurus''. The na ...

''.

Paleobiology

Ecology and feeding

Torvosaurus

''Torvosaurus'' () is a genus of carnivorous megalosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 165 to 148 million years ago during the late Middle and Late Jurassic period (Callovian to Tithonian stages) in what is now Colorado, Portuga ...