Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

where

Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

— languages derived from

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

— are predominantly spoken. The term was coined in the nineteenth century, to refer to regions in the Americas that were ruled by the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

,

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

and

French empires. The term does not have a precise definition, but it is "commonly used to describe

South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

,

Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

,

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, and the islands of the

Caribbean." In a narrow sense, it refers to

Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' imperial era between 15th and 19th centuries. To the e ...

plus

Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

(

Portuguese America

Portuguese America ( pt, América Portuguesa), sometimes called or Lusophone America in the English language, in contrast to Anglo-America, French America or Hispanic America, is the Portuguese-speaking community of people and their diaspora, no ...

). The term "Latin America" is broader than categories such as ''

Hispanic America

The region known as Hispanic America (in Spanish called ''Hispanoamérica'' or ''América Hispana'') and historically as Spanish America (''América Española'') is the portion of the Americas comprising the Spanish-speaking countries of North, ...

'', which specifically refers to Spanish-speaking countries; and ''

Ibero-America

Ibero-America ( es, Iberoamérica, pt, Ibero-América) or Iberian America is a region in the Americas comprising countries or territories where Spanish or Portuguese are predominant languages (usually former territories of Portugal or Spain). ...

'', which specifically refers to both Spanish and Portuguese-speaking countries while leaving French and British excolonies aside.

The term ''Latin America'' was first used in an 1856 conference called "Initiative of America: Idea for a Federal Congress of the Republics" (''Iniciativa de la América. Idea de un Congreso Federal de las Repúblicas''),

by the Chilean politician

Francisco Bilbao

Francisco Bilbao Barquín (; 19 January 1823 – 9 February 1865) was a Chilean writer, philosopher and liberal politician.

Early life

Francisco Bilbao Barquin was born in Santiago on 9 January 1823 to Rafael Bilbao Beyne and Argentina Mercedes ...

. The term was further popularized by French emperor

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

's government in the 1860s as to justify France's military involvement in the

Second Mexican Empire and to include

French-speaking territories in the Americas such as

French Canada

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

,

French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

,

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas. ...

or

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, in the larger group of countries where Spanish and Portuguese languages prevailed.

The United Nations has played a role in defining the region, establishing a

geoscheme for the Americas, which divides the region geographically into North America, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. The

, founded in 1948 and initially called the Economic Commission on Latin America

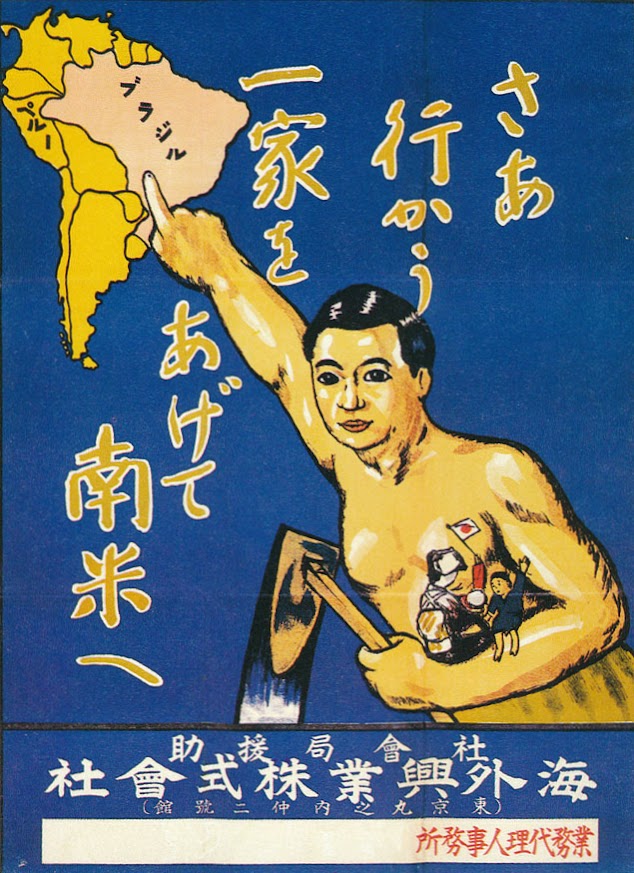

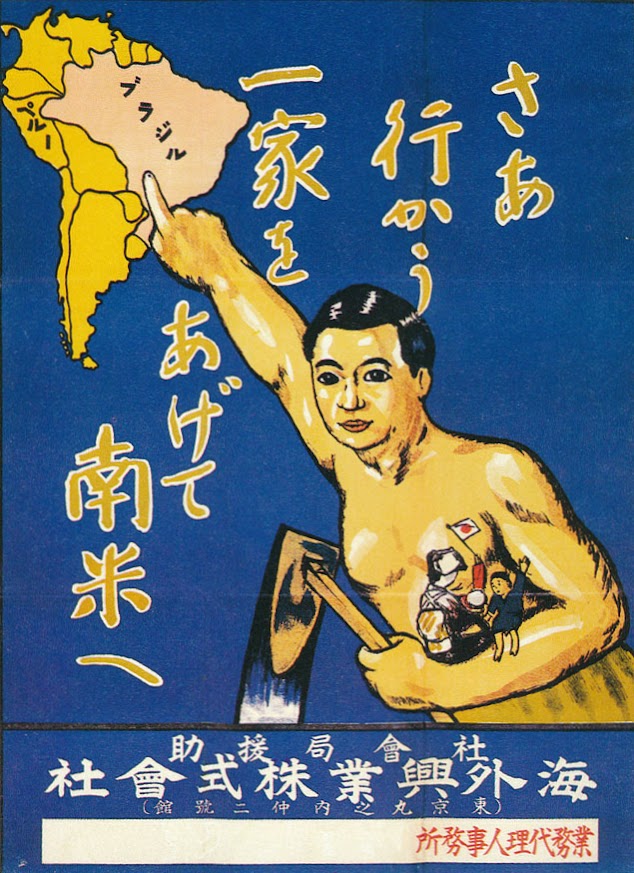

ECLA, comprised Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Chile, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Also included the 1948 establishment were Canada, France, the Netherlands, United Kingdom of Great Britain, and the U.S.A. Obtaining membership later were former colonial powers Spain (1979) and Portugal (1984). In addition, countries not former colonial powers in the region, but many of which had populations immigrate, there are part of ECLAC, including Italy (1990), Germany (2005), Japan (2006), South Korea (2007), Norway (2015), Turkey (2017).

[Date of membership of UNECLAC](_blank)

accessed 20 May 2022 The

Latin American Studies Association

The Latin American Studies Association (LASA) is the largest association for scholars of Latin American studies. Founded in 1966, it has over 12,000 members, 45 percent of whom reside outside the United States (36 percent in Latin America and the C ...

was founded in 1966, with its membership open to anyone interested in

Latin American studies

Latin American studies (LAS) is an academic and research field associated with the study of Latin America. The interdisciplinary study is a subfield of area studies, and can be composed of numerous disciplines such as economics, sociology, history ...

.

The region covers an area that stretches from

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

to

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

and includes much of the

Caribbean. It has an area of approximately 19,197,000 km (7,412,000 sq mi),

almost 13% of the Earth's land surface area. As of March 2, 2020, the population of Latin America and the Caribbean was estimated at more than 652 million, and in 2019, Latin America had a combined

nominal GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

of US$5,188,250 trillion

and a

GDP PPP

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is the measurement of prices in different countries that uses the prices of specific goods to compare the absolute purchasing power of the countries' currencies. PPP is effectively the ratio of the price of a basket ...

of US$10,284,588 trillion.

Etymology and definitions

Origins

There is no universal agreement on the origin of the term ''Latin America''. The concept and term came into being in the nineteenth century, following the political independence of countries from the Spanish and Portuguese empires. It was also popularized in 1860s France during the reign of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

. The term ''Latin America'' was a part of its attempt to create a

French empire in the Americas.

Research has shown that the idea that a part of the Americas has a linguistic and cultural affinity with the Romance cultures as a whole can be traced back to the 1830s, in the writing of the French

Saint-Simonian

Saint-Simonianism was a French political, religious and social movement of the first half of the 19th century, inspired by the ideas of Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825).

Saint-Simon's ideas, expressed largely through a ...

Michel Chevalier

Michel Chevalier (; 13 January 1806 – 18 November 1879) was a French engineer, statesman, economist and free market liberal.

Biography

Born in Limoges, Haute-Vienne, Chevalier studied at the ''École Polytechnique'', obtaining an engineerin ...

, who postulated that a part of the Americas was inhabited by people of a "

Latin race", and that it could, therefore, ally itself with "

Latin Europe

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Lati ...

", ultimately overlapping the

Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Joh ...

, in a struggle with "

Teutonic Europe," "

Anglo-Saxon America," and "

Slavic Europe

Slavic, Slav or Slavonic may refer to:

Peoples

* Slavic peoples, an ethno-linguistic group living in Europe and Asia

** East Slavic peoples, eastern group of Slavic peoples

** South Slavic peoples, southern group of Slavic peoples

** West Sla ...

."

Historian

John Leddy Phelan John Leddy Phelan (1924 - 24 July 1976) was a scholar of colonial Spanish America and the Philippines. He spent the bulk of his scholarly career at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Following his death, his notable former graduate student, Ja ...

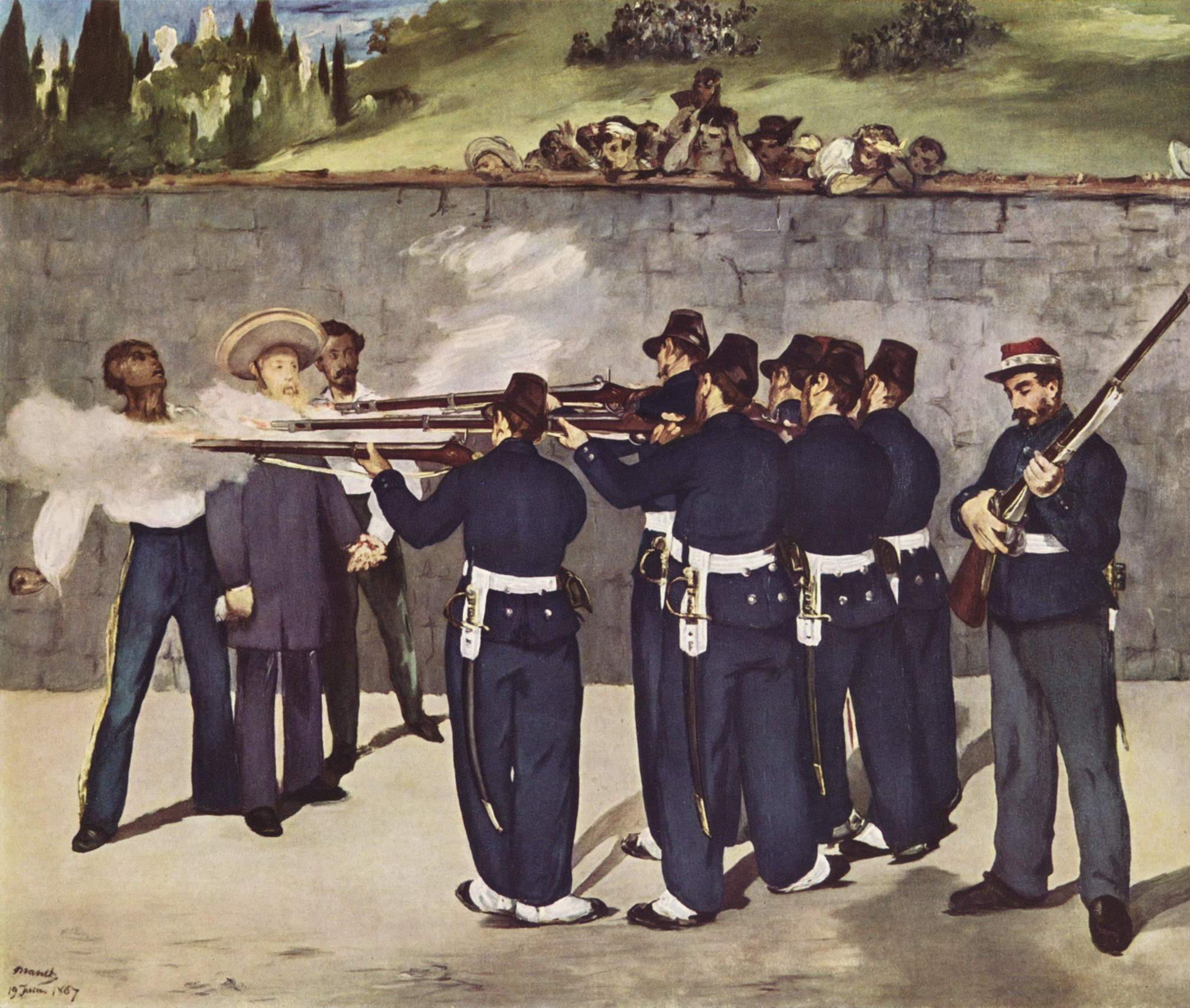

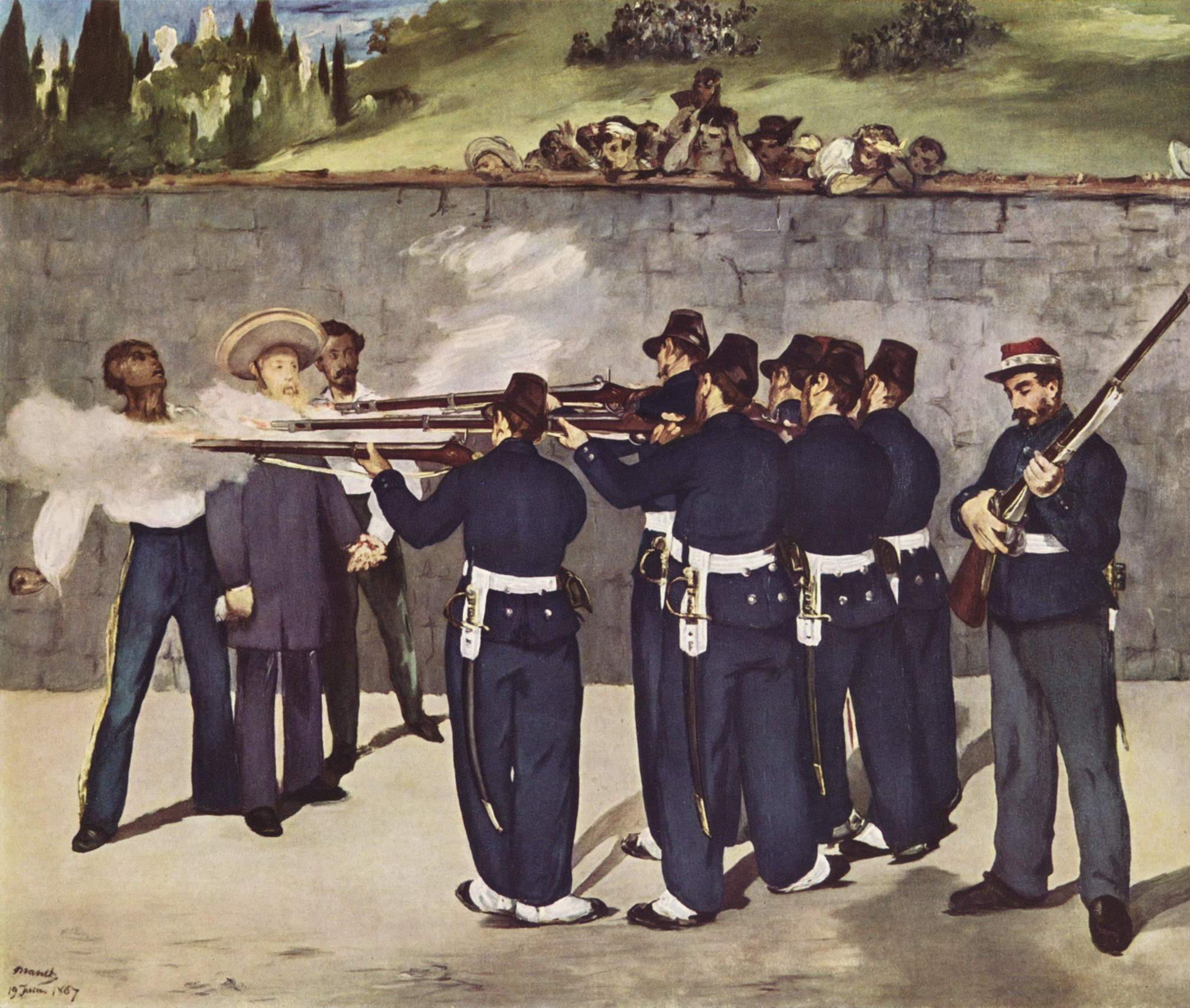

located the origins of the term ''Latin America'' to be from the French occupation of Mexico. His argument is that French imperialists used the concept of "Latin" America as a way to counter British imperialism, as well as to challenge the German threat to France. The idea of a "Latin race" was then taken up by Latin American intellectuals and political leaders of the mid- and late-nineteenth century, who no longer looked to Spain or Portugal as cultural models, but rather to France. French ruler Napoleon III had a strong interest in extending French commercial and political power in the region. He and his business promoter Felix Belly called it "Latin America" to emphasize the shared Latin background of France with the former viceroyalties of Spain and colonies of Portugal. This led to Napoleon III's

failed attempt to take military control of Mexico in the 1860s.

However, though Phelan's thesis is still frequently cited in US academy, further scholarship has shown earlier usage of the term. Two Latin American historians,

Uruguayan

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

Arturo Ardao

Arturo Ardao (Minas, Lavalleja, 27 September 1912 – Montevideo, 22 September 2003) was a Uruguayan philosopher and historian of ideas.

From 1968 to 1972 he was dean of the Faculty of Humanities. Before the Military Coup in 1973, he was forced ...

and

Chilean Miguel Rojas Mix, found evidence that the term "Latin America" was used earlier than Phelan claimed, and the first use of the term was in fact in opposition to imperialist projects in the Americas. Ardao wrote about this subject in his book ''Génesis de la idea y el nombre de América latina'' (Genesis of the Idea and the Name of Latin America, 1980), and Miguel Rojas Mix in his article "Bilbao y el hallazgo de América latina: Unión continental, socialista y libertaria" (Bilbao and the Finding of Latin America: a Continental, Socialist and Libertarian Union, 1986). As Michel Gobat points out in his article "The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism,

Democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, and Race", "Arturo Ardao, Miguel Rojas Mix, and Aims McGuinness have revealed

hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

the term 'Latin America' had already been used in 1856 by Central Americans and South Americans protesting US expansion into the Southern Hemisphere". Edward Shawcross summarizes Ardao's and Rojas Mix's findings in the following way: "Ardao identified the term in a poem by a Colombian diplomat and intellectual resident in France, José María Torres Caicedo, published on 15 February 1857 in a French based Spanish-language newspaper, while Rojas Mix located it in a speech delivered in France by the radical liberal Chilean politician Francisco Bilbao in June 1856".

By the late 1850s, the term was being used in California (which had become a part of the United States), in local newspapers such as ''

El Clamor Público'' by

Californios

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sinc ...

writing about and , and identifying as as the abbreviated term for their "hemispheric membership in ".

The words "Latin" and "America" were first found to be combined in a printed work to produce the term "Latin America" in 1856 in a conference by the Chilean politician

Francisco Bilbao

Francisco Bilbao Barquín (; 19 January 1823 – 9 February 1865) was a Chilean writer, philosopher and liberal politician.

Early life

Francisco Bilbao Barquin was born in Santiago on 9 January 1823 to Rafael Bilbao Beyne and Argentina Mercedes ...

in Paris. The conference had the title "Initiative of the America. Idea for a Federal Congress of Republics."

The following year, Colombian writer

José María Torres Caicedo also used the term in his poem "The Two Americas". Two events related with the United States played a central role in both works. The first event happened less than a decade before the publication of Bilbao's and Torres Caicedo's works: the Invasion of Mexico or, in USA, the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, after which Mexico lost a third of its territory. The second event, the

Walker affair

The Filibuster War or Walker affair was a military conflict between filibustering multinational troops stationed in Nicaragua and a coalition of Central American armies. An American mercenary William Walker invaded Nicaragua in 1855 with a sma ...

, which happened the same year that both works were written: the decision by US president

Franklin Pierce to recognize the regime recently established in

Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

by American

William Walker and his band of filibusters who ruled Nicaragua for nearly a year (1856–57) and attempted to reinstate slavery there, where it had been already abolished for three decades

In both Bilbao's and Torres Caicedo's works, the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

(1846–48) and William Walker's expedition to Nicaragua are explicitly mentioned as examples of dangers for the region. For Bilbao, "Latin America" was not a geographical concept, as he excluded Brazil, Paraguay, and Mexico. Both authors also asked for the union of all Latin American countries as the only way to defend their territories against further foreign US interventions. Both also rejected European imperialism, claiming that the return of European countries to non-democratic forms of government was another danger for Latin American countries, and used the same word to describe the state of European politics at the time: "despotism." Several years later, during the

French invasion of Mexico, Bilbao wrote another work, "Emancipation of the Spirit in America," where he asked all Latin American countries to support the Mexican cause against France, and rejected French imperialism in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. He asked Latin American intellectuals to search for their "intellectual emancipation" by abandoning all French ideas, claiming that France was: "Hypocrite, because she

rance

Rance may refer to:

Places

* Rance (river), northwestern France

* Rancé, a commune in eastern France, near Lyon

* Ranče, a small settlement in Slovenia

* Rance, Wallonia, part of the municipality of Sivry-Rance

** Rouge de Rance, a Devonian ...

calls herself protector of the Latin race just to subject it to her exploitation regime; treacherous, because she speaks of freedom and nationality, when, unable to conquer freedom for herself, she enslaves others instead!" Therefore, as Michel Gobat puts it, the term Latin America itself had an "anti-imperial genesis," and their creators were far from supporting any form of imperialism in the region, or in any other place of the globe.

In France, the term Latin America was used with the opposite intention. It was employed by the French Empire of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

during the French invasion of Mexico as a way to include France among countries with influence in the Americas and to exclude

Anglophone countries

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the '' Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

. It played a role in his campaign to imply cultural kinship of the region with France, transform France into a cultural and political leader of the area, and install

Maximilian of Habsburg

Maximilian I (german: Ferdinand Maximilian Josef Maria von Habsburg-Lothringen, link=no, es, Fernando Maximiliano José María de Habsburgo-Lorena, link=no; 6 July 1832 – 19 June 1867) was an Austrian archduke who reigned as the only Emperor ...

as emperor of the

Second Mexican Empire. The term was also used in 1861 by French scholars in ''La revue des races Latines,'' a magazine dedicated to the

Pan-Latinism

Pan-Latinism is an ideology that promotes the unification of the Romance-speaking peoples. Pan-Latinism first arose in prominence in France particularly from the influence of Michel Chevalier (1806–1879) who contrasted the "Latin" peoples of the ...

movement.

Contemporary definitions

* ''Latin America'' is often used synonymously with Ibero-America ("Iberian America"), excluding the predominantly Dutch-, French-, and English-speaking territories. Thus, the countries of

Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

,

Guyana and

Suriname, as well as several French overseas departments, are excluded. On the other hand,

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

is then usually included.

* In another definition, which is close to the semantic origin, ''Latin America'' designates the set of countries in the Americas where a Romance language (a language derived from Latin) predominates: Spanish, Portuguese, French, or a

creole language

A creole language, or simply creole, is a stable natural language that develops from the simplifying and mixing of different languages into a new one within a fairly brief period of time: often, a pidgin evolved into a full-fledged language. ...

based upon the three. Thus, it includes Mexico; most of Central and South America; and in the Caribbean, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti. ''Latin America'' then comprises all of the countries in the Americas that were once part of the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

,

Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, and

French Empires.

Puerto Rico, although not a country, may sometimes be included.

* The term is sometimes used more broadly to refer to all of the Americas south of the United States,

thus including

the Guianas

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France

* ...

(

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas. ...

,

Guyana, and

Suriname); the

Anglophone Caribbean (and

Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

); the

Francophone Caribbean; and the

Dutch Caribbean

The Dutch Caribbean (historically known as the Dutch West Indies) are the territories, colonies, and countries, former and current, of the Dutch Empire and the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean Sea. They are in the north and south-wes ...

. This definition emphasizes a similar

socioeconomic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their l ...

history of the region, which was characterized by formal or

informal colonialism, rather than cultural aspects (see, for example,

dependency theory

Dependency theory is the notion that resources flow from a " periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a " core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former. A central contention of dependency theory is that poor ...

). Some sources avoid this simplification by using the alternative phrase "

Latin America and the Caribbean

The term Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is an English-language acronym referring to the Latin American and the Caribbean region. The term LAC covers an extensive region, extending from The Bahamas and Mexico to Argentina and Chile. The ...

", as in the

United Nations geoscheme for the Americas

The following is an alphabetical list of countries in the United Nations geoscheme for the Americas grouped by subregion and (if applicable) intermediate region. Note that the continent of North America comprises the intermediate regions of th ...

.

The distinction between ''Latin America'' and ''

Anglo-America

Anglo-America most often refers to a region in the Americas in which English is the main language and British culture and the British Empire have had significant historical, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural impact."Anglo-America", vol. 1, Micro ...

'' is a convention based on the predominant languages in the Americas by which Romance language- and English-speaking cultures are distinguished. Neither area is culturally or linguistically homogeneous; in substantial portions of Latin America (e.g., highland

Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

,

Bolivia, Mexico,

Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by H ...

),

Native American cultures and, to a lesser extent, Amerindian languages, are predominant, and in other areas, the influence of African cultures is strong (e.g., the Caribbean basinincluding parts of

Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

and

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

).

The term is not without controversy. Historian Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo explores at length the "allure and power" of the idea of Latin America. He remarks at the outset, "The idea of 'Latin America' ought to have vanished with the obsolescence of racial theory... But it is not easy to declare something dead when it can hardly be said to have existed," going on to say, "The term is here to stay, and it is important." Following in the tradition of Chilean writer Francisco Bilbao, who excluded Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay from his early conceptualization of Latin America, Chilean historian

Jaime Eyzaguirre

Jaime Eyzaguirre (21 December 1908 – 17 September 1968) was a Chilean lawyer, essayist and historian. He is variously recognized as a writer of Spanish traditionalist or conservative historiography in his country.Góngora ''et al''., pp. 201� ...

has criticized the term Latin America for "disguising" and "diluting" the Spanish character of a region (i.e.

Hispanic America

The region known as Hispanic America (in Spanish called ''Hispanoamérica'' or ''América Hispana'') and historically as Spanish America (''América Española'') is the portion of the Americas comprising the Spanish-speaking countries of North, ...

) with the inclusion of nations that, according to him, do not share the same pattern of

conquest and colonization.

The

Francophone part of North America which includes

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

and

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

is generally excluded from the definition of Latin America.

Subregions and countries

Latin America can be subdivided into several subregions based on geography, politics, demographics and culture. It is defined as all of the Americas south of the United States, the basic geographical subregions are North America, Central America, the

Caribbean and South America; the latter contains further politico-geographical subdivisions such as the

Southern Cone,

The Guianas

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France

* ...

and the

Andean states

The Andean states ( es, Estados Andinos) are a group of countries in western South America connected by the Andes mountain range. The "Andean States" is sometimes used to refer to all seven countries that the Andes runs through, regions with a sh ...

. It may be subdivided on linguistic grounds into

Spanish America

Spanish America refers to the Spanish territories in the Americas during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term "Spanish America" was specifically used during the territories' imperial era between 15th and 19th centuries. To the e ...

,

Portuguese America

Portuguese America ( pt, América Portuguesa), sometimes called or Lusophone America in the English language, in contrast to Anglo-America, French America or Hispanic America, is the Portuguese-speaking community of people and their diaspora, no ...

, and

French America

French America (), sometimes called Franco-America, in contrast to Anglo-America, is the French-speaking community of people and their diaspora, notably those tracing back origins to New France, the early French colonization of the Americas. Th ...

.

: Not a sovereign state

History

Before European Contact in 1492

The earliest known human settlement in the area was identified at

Monte Verde

Monte Verde is an archaeological site in the Llanquihue Province in southern Chile, located near Puerto Montt, Southern Chile, which has been dated to as early as 18,500 cal BP (16,500 BC). Previously, the widely accepted date for early occu ...

, near

Puerto Montt in southern Chile. Its occupation dates to some 14,000 years ago and there is disputed evidence of even earlier occupation. Over the course of millennia, people spread to all parts of the North and South America and the Caribbean islands. Although the region now known as Latin America stretches from northern Mexico to

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

, the diversity of its geography, topography, climate, and cultivable land means that populations were not evenly distributed. Sedentary populations of fixed settlements supported by agriculture gave rise to complex civilizations in

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

(central and southern Mexico and Central America) and the highland Andes populations of

Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

and

Aymara

Aymara may refer to:

Languages and people

* Aymaran languages, the second most widespread Andean language

** Aymara language, the main language within that family

** Central Aymara, the other surviving branch of the Aymara(n) family, which today ...

, as well as

Chibcha

The Muisca (also called Chibcha) are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan lan ...

.

Agricultural surpluses from intensive cultivation of

maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

in Mesoamerica and

potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

es and hardy grains in the Andes were able to support distant populations beyond farmers' households and communities. Surpluses allowed the creation of social, political, religious, and military hierarchies, urbanization with stable village settlements and major cities, specialization of craft work, and the transfer of products via tribute and trade. In the Andes,

llamas

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is s ...

were domesticated and used to transport goods; Mesoamerica had no large domesticated animals to aid human labor or provide meat. Mesoamerican civilizations developed systems of writing; in the Andes, knotted

quipu

''Quipu'' (also spelled ''khipu'') are recording devices fashioned from strings historically used by a number of cultures in the region of Andean South America.

A ''quipu'' usually consisted of cotton or camelid fiber strings. The Inca people ...

s emerged as a system of accounting.

The Caribbean region had sedentary populations settled by

Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

or

Tainos and in what is now Brazil, many

Tupian

The Tupi or Tupian language family comprises some 70 languages spoken in South America, of which the best known are Tupi proper and Guarani.

Homeland and ''urheimat''

Rodrigues (2007) considers the Proto-Tupian urheimat to be somewhere between ...

peoples lived in fixed settlements. Semi-sedentary populations had agriculture and settled villages, but

soil exhaustion required relocation of settlements. Populations were less dense and social and political hierarchies less institutionalized. Non-sedentary peoples lived in small bands, with low population density and without agriculture. They lived in harsh environments. By the first millennium

CE, the Western Hemisphere was the home of tens of millions of people; the exact numbers are a source of ongoing research and controversy.

The last two great

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

s, the

Aztecs and

Incas

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, ( Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The adm ...

, emerged into prominence in the early fourteenth century and mid-fifteenth centuries. Although the Indigenous empires were conquered by Europeans, the sub-imperial organization of the densely populated regions remained in place. The presence or absence of Indigenous populations had an impact on how European imperialism played out in the Americas. The pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica and the highland Andes became sources of pride for American-born Spaniards in the late colonial era and for nationalists in the post-independence era. For some modern Latin American nation-states, the Indigenous roots of national identity are expressed in the ideology of ''

indigenismo

''Indigenismo'' () is a political ideology in several Latin American countries which emphasizes the relationship between the nation state and indigenous nations and indigenous peoples. In some contemporary uses, it refers to the pursuit of great ...

''. These modern constructions of national identity usually critique their colonial past.

Colonial era, 1492-1825

Spanish and Portuguese colonization of the Western Hemisphere laid the basis for societies now seen as characteristic of Latin America. In the fifteenth century, both Portugal and Spain embarked on voyages of overseas exploration, following the Christian

Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

of Iberia from Muslims. Portugal sailed down the west coast of Africa and the

Crown of Castile in central Spain authorized the voyage of

Genoese mariner

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. Portugal's maritime expansion into the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

was initially its main interest; but the off-course voyage of

Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral ( or ; born Pedro Álvares de Gouveia; c. 1467 or 1468 – c. 1520) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil. He was the first human in ...

in 1500 allowed Portugal to claim Brazil. The 1494

line of demarcation

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Emp ...

between Spain and Portugal gave Spain all areas to the west, and Portugal all areas to the east. For Portugal, the riches of Africa, India, and the

Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

were far more important initially than the unknown territory of Brazil. By contrast, having no better prospects, the Spanish crown directed its energies to its

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

territories. Spanish colonists began founding permanent settlements in the circum-Caribbean region, starting in 1493. In these regions of early contact, Spaniards established patterns of interaction with Indigenous peoples that they transferred to the mainland. At the time of European contact, the area was densely populated by Indigenous peoples who had not organized as empires, nor created large physical complexes. With the expedition of

Hernán Cortés from Cuba to Mexico in 1519, Spaniards encountered the Indigenous imperial civilization of the

Aztecs. Using techniques of warfare honed in their early Caribbean settlements, Cortés sought Indigenous allies to topple the superstructure of the

Aztec Empire after a two-year

war of conquest. The Spanish recognized many Indigenous elites as nobles under Spanish rule with continued power and influence over commoners, and used them as intermediaries in the emerging Spanish imperial system.

With the example of the conquest of central Mexico, Spaniards sought similar great empires to conquer, and expanded into other regions of Mexico and Central America, and then the Inca empire, by

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

. By the end of the sixteenth century Spain and Portugal claimed territory extending from Alaska to the southern tip of

Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

. They founded cities that remain important centers. In Spanish America, these include

Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is locat ...

(1519),

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

(1521)

Guadalajara (1531–42),

Cartagena (1532),

Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

(1534),

Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

(1535), and

Quito (1534).

In Brazil, coastal cities were founded:

Olinda (1537),

Salvador de Bahia

Salvador (English: ''Savior'') is a Brazilian municipality and capital city of the state of Bahia. Situated in the Zona da Mata in the Northeast Region of Brazil, Salvador is recognized throughout the country and internationally for its cuisine ...

(1549),

São Paulo

São Paulo (, ; Portuguese for 'Saint Paul') is the most populous city in Brazil, and is the capital of the state of São Paulo, the most populous and wealthiest Brazilian state, located in the country's Southeast Region. Listed by the GaWC a ...

(1554), and

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a ...

(1565).

Spaniards explored extensively in the mainland territories they claimed, but they settled in great numbers in areas with dense and hierarchically organized Indigenous populations and exploitable resources, especially

silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

. Early Spanish conquerors saw the Indigenous themselves as an exploitable resource for tribute and labor, and individual

Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both in ...

were awarded grants of

encomienda forced labor as reward for participation in the conquest. Throughout most of Spanish America, Indigenous populations were the largest component, with some black slaves serving in auxiliary positions. The three main racial groups during the colonial era were European whites, black Africans, and Indigenous. Over time, these populations intermixed, resulting in

castas

() is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas it also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical f ...

. In most of Spanish America, the Indigenous were the majority population.

Both dense Indigenous populations and silver were found in

New Spain (colonial Mexico) and Peru, and the now-countries became centers of the Spanish empire. The

Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

, centered in

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

, was established in 1535 and the

Viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed fro ...

, centered in

Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

, in 1542. The Viceroyalty of New Spain also had

jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

J ...

over the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, once the Spanish established themselves there in the late sixteenth century. The

viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

was the direct representative of the king.

The

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, as an institution, launched a "spiritual conquest" to convert Indigenous populations to

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, incorporating them into

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

, with no other religion permitted. Pope

Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 – 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

in 1493 had bestowed on the

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

over ecclesiastical appointments and the functioning of the church in overseas possessions. The monarch was the patron of the institutional church. The state and the Catholic church were the institutional pillars of Spanish colonial rule. In the late eighteenth century, the crown also established a royal military to defend its possessions against foreign incursions, especially by the British. It also increased the number of viceroyalties in Spanish South America.

Portugal did not establish firm institutional rule in Brazil until the 1530s, but it paralleled many patterns of colonization in Spanish America. The

Brazilian Indigenous peoples were initially dense, but were

semi-sedentary and lacked the organization that allowed Spaniards to more easily incorporate the Indigenous into the colonial order. The Portuguese used Indigenous laborers to extract the valuable commodity known as

brazilwood, which gave its name to the colony. Portugal took greater control of the region to prevent other European powers, particularly France, from threatening its claims.

Europeans sought wealth in the form of high-value, low-bulk products exported to Europe. The Spanish Empire established institutions to secure wealth for itself and protect its empire in the Americas from rivals. In trade it followed principles of

mercantilism, where its overseas possessions were to enrich the center of power in Iberia. Trade was regulated through the royal

House of Trade in Seville, Spain, with the main export from Spanish America to Spain being silver, later followed by the red dye

cochineal

The cochineal ( , ; ''Dactylopius coccus'') is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America through North Americ ...

. Silver was found in the Andes, in particular the silver mountain of

Potosí, (now in

Bolivia) in the region where Indigenous men were

forced to labor in the mines. In New Spain, rich deposits of silver were found in northern Mexico, in

Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

and

Guanajuato, outside areas of dense Indigenous settlement. Labor was attracted from elsewhere for mining and landed estates were established to raise wheat, range cattle and sheep.

Mules were bred for transportation and to replace of human labor in refining silver.

In Brazil and some Spanish Caribbean islands,

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

for sugar cultivation developed on a large scale for the export market. For Brazil, the development of the plantation complex transformed the colony from a backwater of the Portuguese empire to a major asset. The Portuguese transported enslaved laborers from their African territories and the seventeenth-century "age of sugar" was transformational, seeing Brazil becoming a major economic component of the Portuguese empire. The population increase exponentially, with the majority being enslaved Africans. Settlement and economic development was largely coastal, the goal of sugar export to European markets. With competition from other sugar producers, Brazil's fortunes based on sugar declined, but in the eighteenth century, diamonds and gold were found in the southern interior, fueling a new wave of economic activity. As the economic center of the colony shifted from the sugar-producing northeast to the southern region of gold and diamond mines, the capital was transferred from Salvador de Bahia to Rio de Janeiro in 1763. During the colonial era, Brazil was also the manufacturing center for Portugal's ships. As a global maritime empire, Portugal created a vital industry in Brazil. Once Brazil achieved its independence, this industry languished.

In Spanish America, manufactured and luxury goods were sent from Spain and entered Spanish America legally only through the Caribbean ports of

Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

,

Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. , and

Cartagena, as well as the Pacific port of

Callao, in Peru.

Trans-Pacific trade was established in the late sixteenth century from

Acapulco to the Philippines via the

Manila Galleon

fil, Galyon ng Maynila

, english_name = Manila Galleon

, duration = From 1565 to 1815 (250 years)

, venue = Between Manila and Acapulco

, location = New Spain (Spanish Empire ...

, transporting silver from Mexico and Peru to Asia; Chinese

silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

s and

porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

s were sent first to Mexico and then re-exported to Spain. This system of commerce was in theory was tightly controlled, but was increasingly undermined by other European powers. The English, French, and Dutch seized Caribbean islands claimed by the Spanish and established their own sugar plantations. The islands also became hubs for

contraband trade with Spanish America. Many regions of Spanish America that were not well supplied by Spanish merchants, such as Central America, participated in contraband trade with foreign merchants. The eighteenth-century

Bourbon reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Monarchy, Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of ...

sought to modernize the mercantile system to stimulate greater trade exchanges between Spain and Spanish America in a system known as ''comercio libre''. It was not

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

in the modern sense, but rather free commerce within the Spanish empire. Liberalization of trade and limited deregulation sought to break the

monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

of merchants based in the Spanish port of

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

. Administrative reforms created the system of districts known as

intendancies, modeled on those in France. Their creation was aimed at strengthening crown control over its possessions and sparking

economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and ...

.

Both Spain and Portugal restricted foreign powers from trading in their American colonies or entering coastal waters it had claimed. Other European powers challenged the exclusive rights claimed by the Iberian powers. The English, Dutch, and French permanently seized islands in the Caribbean and created sugar plantations on the model developed in Brazil. In Brazil, the Dutch seized the sugar-producing area of the

northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

, but after 30 years they were expelled.

Colonial legacies

More than three centuries of direct Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule left lasting imprints on Latin America. Spanish and Portuguese are the dominant languages of the region, and Roman Catholicism is the dominant religion. Diseases to which Indigenous peoples had no

immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

devastated their populations, although populations still exist in many places. The forced transportation of African slaves transformed major regions where they labored to produce the export products, especially sugar. In regions with dense Indigenous populations, they remained the largest percentage of the population; sugar-producing regions had the largest percentage of blacks. European whites in both Spanish America and Brazil were a small percentage of the population, but they were also the wealthiest and most socially elite; and the racial hierarchies they established in the colonial era have persisted. Cities founded by Europeans in the colonial era remain major centers of power. In the modern era, Latin American governments have worked to designate many colonial cities as

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

World Heritage Sites

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

.

Exports of metals and agricultural products to Europe dominate Latin American economies, with the manufacturing sector deliberately suppressed; the development of modern, industrial economies of Europe depended on the underdevelopment of Latin America.

Despite the many commonalities of colonial Spanish America and Brazil, they did not think of themselves as being part of a particular region; that was a development of the post-independence period beginning in the nineteenth century. The imprint of Christopher Columbus and Iberian colonialism in Latin America began shifting in the twentieth century. "Discovery" by Europeans was reframed as "encounter" between the

Old World and the

New

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

. An example of the new consciousness was the dismantling of the Christopher Columbus monument in

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, one of many in the hemisphere, mandated by leftist President

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

Cristina Elisabet Fernández de Kirchner (; born 19 February 1953), often referred to by her initials CFK, is an Argentine lawyer and politician who has served as the Vice President of Argentina since 2019. She also served as the President o ...

. Its replacement was a statue to a

mestiza

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also refer to people who are culturally European even though thei ...

fighter for independence,

Juana Azurduy de Padilla

Juana Azurduy de Padilla (July 12, 1780 – May 25, 1862) was a guerrilla military leader from Chuquisaca, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Sucre, Bolivia).Pallis, Michael “Slaves of Slaves: The Challenge of Latin American Women” (Lon ...

, provoking a major controversy in Argentina over historical and national identity.

Independence era (1776–1825)

Independence in the Americas was not inevitable or uniform in the Americas. Events in Europe had a profound impact on the colonial empires of Spain, Portugal, and France in the Americas. France and Spain had supported the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

that saw the independence of the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

from Britain, which had defeated them in the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

(1757–63). The outbreak of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

in 1789, a political and social uprising toppling the Bourbon monarchy and overturning the established order, precipitated events in France's rich Caribbean sugar colony of

Saint-Domingue, whose black population rose up, led by

Toussaint L'ouverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture ...

. The

Haitian Revolution had far-reaching consequences. Britain declared war on France and attacked ports in Saint-Domingue. Haiti gained independence in 1804, led by ex-slave

Jean-Jacques Dessalines following many years of violent struggle, with huge atrocities on both sides. Haitian independence affected colonial empires in the Americas, as well as the United States. Many white, slave-owning sugar planters of Saint-Domingue fled to the Spanish island of Cuba, where they established sugar plantations that became the basis of Cuba's economy. Uniquely in the hemisphere, the black victors in Haiti abolished slavery at independence. Many thousands of remaining whites were executed on the orders of Dessalines. For other regions with large enslaved populations, the Haitian Revolution was a cautionary tale for the white slave-owning planters. Despite Spain and Britain's satisfaction with France's defeat, they "were obsessed by the possible impact of the slave uprising on Cuba, Santo Domingo, and Jamaica", by then a British sugar colony. US President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

, a wealthy slave owner, refused to recognize Haiti's independence. Recognition only came in 1862 from President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. Given France's failure to defeat the slave insurgency and since needing money for the war with Britain,

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

sold France's remaining mainland holdings in North America to the United States in the 1803

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's invasion of the Iberian peninsula in 1807-1808 was a major change in the world order, with the stability of both the metropoles and their overseas possessions upended. It resulted in the movement, with British help, of the

Portuguese royal court to Brazil, its richest colony. In Spain, France forced abdication of the Spanish Bourbon monarchs and their replacement with Napoleon's brother

Joseph Bonaparte

it, Giuseppe-Napoleone Buonaparte es, José Napoleón Bonaparte

, house = Bonaparte

, father = Carlo Buonaparte

, mother = Letizia Ramolino

, birth_date = 7 January 1768

, birth_place = Corte, Corsica, Republic of ...

as king. The period from 1808 to the restoration in 1814 of the Bourbon monarchy saw new political experiments. In Spanish America, the question of the legitimacy of the new foreign monarch's right to rule set off fierce debate and in many regions to

wars of independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against for ...

. The conflicts were regional and usually quite complex. Chronologically, the Spanish American independence wars were the conquest in reverse, with the areas most recently incorporated into the Spanish empire, such as Argentina and Chile, becoming the first to achieve independence, while the colonial strongholds of Mexico and Peru were the last to achieve independence in the early nineteenth century. Cuba and Puerto Rico, both old Caribbean sugar-producing areas, did not achieve independence from Spain until the 1898

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, with US intervention.

In Spain, a

bloody war against the French invaders broke out and regional juntas were established to rule in the name of the deposed Bourbon king,

Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

. In Spanish America, local juntas also rejected Napoleon's brother as their monarch. Spanish Liberals re-imagined the Spanish Empire as equally being Iberia and the overseas territories. Liberals sought a new model of government, a constitutional monarchy, with limits on the power of the king as well as on the Catholic Church. Ruling in the name of the deposed Bourbon monarch Ferdinand VII, representatives of the Spanish empire, both from the peninsula and Spanish America, convened a convention in the port of Cadiz. For Spanish American elites who had been shut out of official positions in the late eighteenth century in favor of peninsular-born appointees, this was a major recognition of their role in the empire. These empire-wide representatives drafted and ratified the

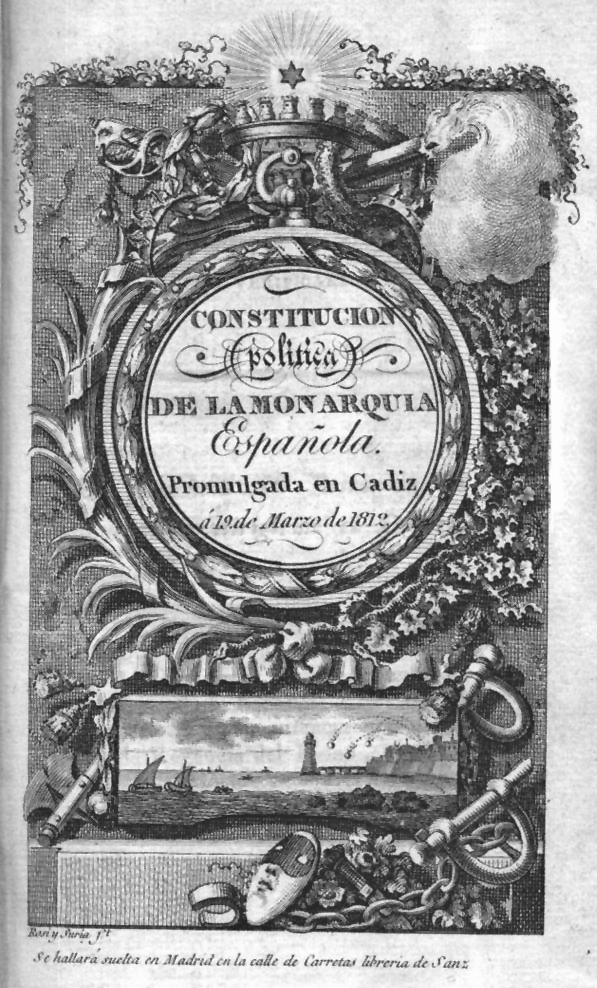

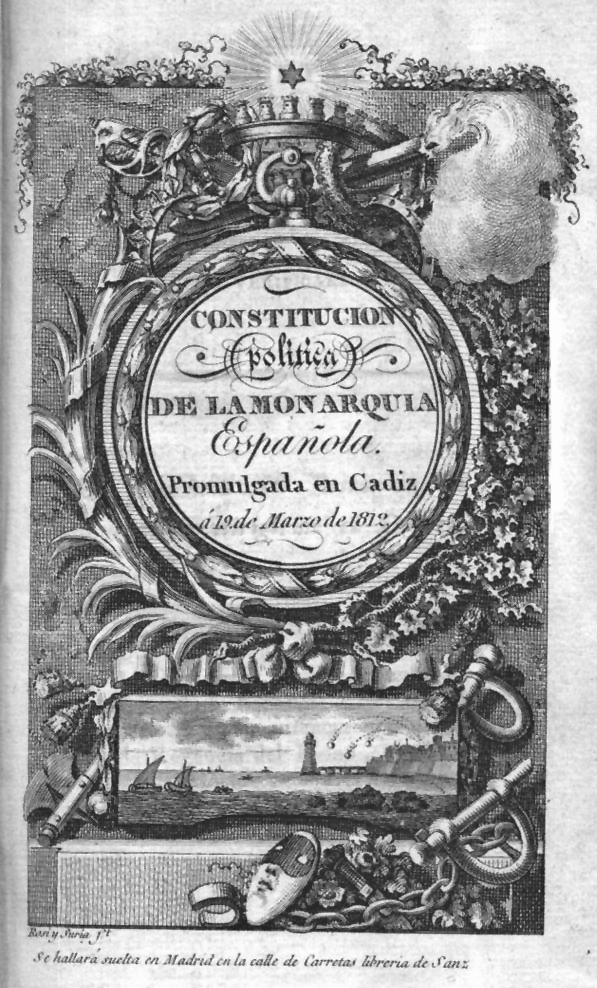

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitut ...

, establishing a constitutional monarchy and set down other rules of governance, including citizenship and limitations on the Catholic Church. Constitutional rule was a break from

absolutist monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

and gave Spanish America a starting point for constitutional governance. So long as Napoleon controlled Spain, the liberal constitution was the governing document.

When Napoleon was defeated and the Bourbon monarchy was restored in 1814,

Ferdinand VII

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles IV of Spain

, mother = Maria Luisa of Parma

, birth_date = 14 October 1784

, birth_place = El Escorial, Spain

, death_date =

, death_place = Madrid, Spain

, burial_plac ...

and his conservative supporters immediately reasserted absolutist monarchy, ending the liberal

interregnum. In Spanish America, it set off a new wave of struggles for independence.

In South America,

Simón Bolívar of Venezuela,

José de San Martín

José Francisco de San Martín y Matorras (25 February 177817 August 1850), known simply as José de San Martín () or '' the Liberator of Argentina, Chile and Peru'', was an Argentine general and the primary leader of the southern and centr ...

of Argentina, and

Bernardo O'Higgins

Bernardo O'Higgins Riquelme (; August 20, 1778 – October 24, 1842) was a Chilean independence leader who freed Chile from Spanish rule in the Chilean War of Independence. He was a wealthy landowner of Basque-Spanish and Irish ancestry. Alth ...

in Chile led armies who fought for independence. In Mexico, which had seen the initial insurgency led by Hidalgo and

José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

,

royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

forces maintained control. In 1820, when military officers in Spain restored the liberal

Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

, conservatives in Mexico saw independence as a better option. Royalist military officer

Agustín de Iturbide changed sides and forged an alliance with insurgent leader

Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

, and together they brought about Mexico's independence in 1821.

For Portugal and Brazil, Napoleon's defeat did not immediately result in the return of the Portuguese monarch to Portugal, as Brazil was the richest part of the Portuguese empire. As with Spain in 1820,

Portuguese liberals threatened the power of the monarchy and compelled

John VI to return in April 1821, leaving his son Pedro to rule Brazil as regent. In Brazil, Pedro contended with revolutionaries and insubordination by Portuguese troops, all of whom he subdued. The Portuguese government threatened to revoke the political autonomy that Brazil had enjoyed since 1808, provoking widespread opposition in Brazil. Pedro declared