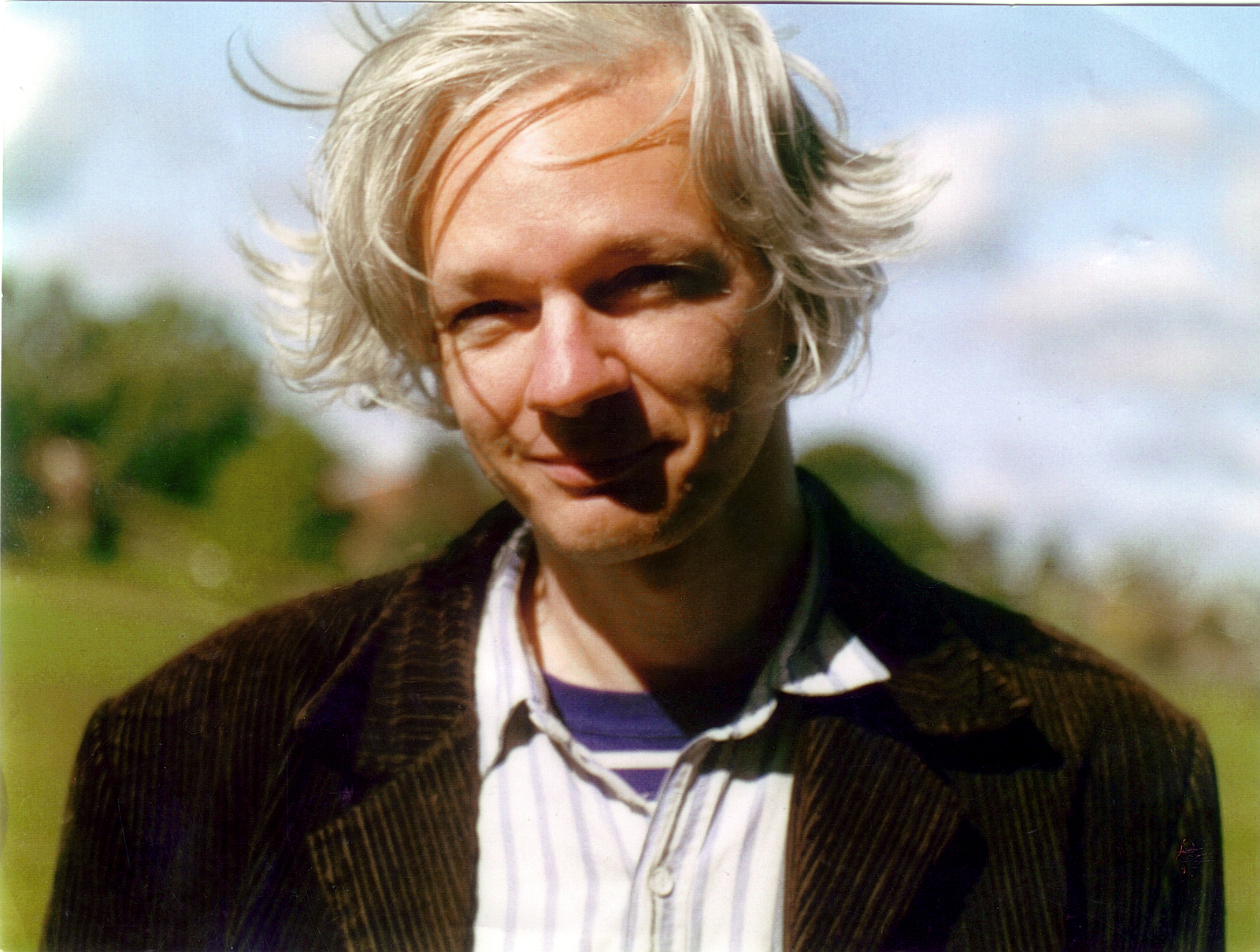

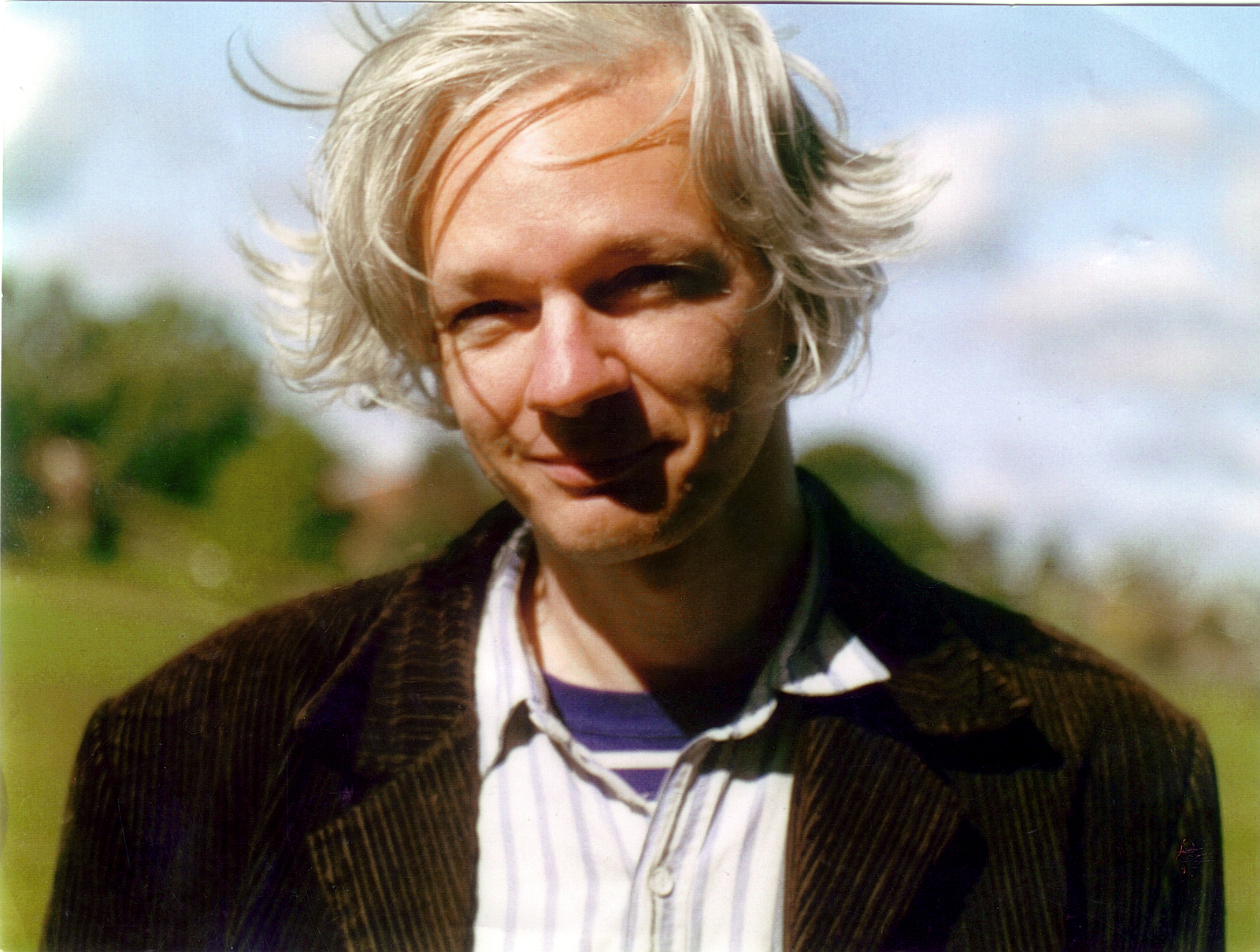

Julian Paul Assange ( ; Hawkins; born 3 July 1971) is an Australian editor, publisher, and activist who founded

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks () is an international non-profit organisation that published news leaks and classified media provided by anonymous sources. Julian Assange, an Australian Internet activist, is generally described as its founder and director and ...

in 2006. WikiLeaks came to international attention in 2010 when it published a series of

leaks

A leak is a way (usually an opening) for fluid to escape a container or fluid-containing system, such as a tank or a ship's hull, through which the contents of the container can escape or outside matter can enter the container. Leaks are usua ...

provided by

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

intelligence analyst

Intelligence analysis is the application of individual and collective cognitive methods to weigh data and test hypotheses within a secret socio-cultural context. The descriptions are drawn from what may only be available in the form of deliberate ...

Chelsea Manning

Chelsea Elizabeth Manning (born Bradley Edward Manning; December 17, 1987) is an American activist and whistleblower. She is a former United States Army soldier who was convicted by court-martial in July 2013 of violations of the Espionage A ...

. These leaks included the

Baghdad airstrike ''Collateral Murder'' video (April 2010),

[, 5 April 2000. Retrieved 28 March 2014.] the

Afghanistan war logs (July 2010), the

Iraq war logs

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

(October 2010), and

Cablegate

The United States diplomatic cables leak, widely known as Cablegate, began on Sunday, 28 November 2010 when WikiLeaks began releasing classified cables that had been sent to the U.S. State Department by 274 of its consulates, embassies, and ...

(November 2010). After the 2010 leaks, the

United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

launched a criminal investigation into WikiLeaks.

In November 2010, Sweden issued a

European arrest warrant for Assange over allegations of

sexual misconduct

Sexual misconduct is misconduct of a sexual nature which exists on a spectrum that may include a broad range of sexual behaviors considered unwelcome. This includes conduct considered inappropriate on an individual or societal basis of morality, se ...

. Assange said the allegations were a pretext for his

extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

from Sweden to the United States over his role in the publication of secret American documents.

After losing his battle against extradition to Sweden, he breached bail and took refuge in the

Embassy of Ecuador in London in June 2012. He was granted

asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

by

Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

in August 2012 on the grounds of political persecution, with the presumption that if he were extradited to Sweden, he would be eventually extradited to the United States. Swedish prosecutors dropped their investigation in 2019, saying their evidence had "weakened considerably due to the long period of time that has elapsed since the events in question".

During the 2016 U.S. election campaign, WikiLeaks

published

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed works, such as books, news ...

confidential

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

emails, showing that the party's

national committee

The National Committee ( el, Εθνικό Κομιτάτο) was a Greek political party founded by Epameinondas Deligiorgis.

The party was founded in 1865, and was composed by young revolutionaries who helped to overthrow King Otto, ending his ...

favoured

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

over her rival

Bernie Sanders in the

primaries

Primary elections, or direct primary are a voting process by which voters can indicate their preference for their party's candidate, or a candidate in general, in an upcoming general election, local election, or by-election. Depending on the c ...

.

In March 2017, WikiLeaks

published a series of documents which detailed the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

's electronic surveillance and cyber warfare capabilities.

On 11 April 2019, Assange's asylum was withdrawn following a series of disputes with the Ecuadorian authorities. The police were invited into the embassy and he was arrested.

He was found guilty of breaching the

Bail Act and sentenced to 50 weeks in prison.

The United States government unsealed an indictment against Assange related to the leaks provided by Manning. On 23 May 2019, the United States government further charged Assange with violating the

Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

. Editors from newspapers, including ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' and ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', as well as

press freedom organisations, criticised the government's decision to charge Assange under the Espionage Act, characterising it as an attack on the

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents the government from making laws that regulate an establishment of religion, or that prohibit the free exercise of religion, or abridge the freedom of speech, the ...

, which guarantees freedom of the press.

On 4 January 2021,

UK District Judge Vanessa Baraitser ruled against the United States' request to extradite Assange and stated that doing so would be "oppressive" given concerns over Assange's mental health and risk of suicide.

On 6 January 2021, Assange was denied bail, pending an appeal by the United States.

On 10 December 2021, the

High Court in London ruled that Assange could be extradited to the US to face the charges. In March 2022, the

UK Supreme Court refused Assange permission to appeal.

On 17 June 2022,

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

Priti Patel approved the extradition.

On 1 July 2022, it was announced that Assange had formally appealed against the extradition order.

Assange has been confined in

Belmarsh

His Majesty's Prison Belmarsh is a Category-A men's prison in Thamesmead, south-east London, England. The prison is used in high-profile cases, particularly those concerning national security. Within the prison grounds there is a unique unit c ...

, a

category A prison

In the United Kingdom, prisoners are divided into four categories of security. Each adult is assigned a category, depending on the crime committed, the sentence, the risk of escape, and violent tendencies. The categories are single letters, in a ...

, in London since April 2019.

Early life

Assange was born Julian Paul Hawkins on 3 July 1971 in

Townsville

Townsville is a city on the north-eastern coast of Queensland, Australia. With a population of 180,820 as of June 2018, it is the largest settlement in North Queensland; it is unofficially considered its capital. Estimated resident population, 3 ...

,

Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

,

to Christine Ann Hawkins (b. 1951), a

visual artist

The visual arts are art forms such as painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, photography, video, filmmaking, design, crafts and architecture. Many artistic disciplines such as performing arts, conceptual art, and textile arts al ...

,

and John Shipton, an

anti-war activist and builder.

The couple separated before their son was born.

When Julian was a year old, his mother married Brett Assange,

an actor with whom she ran a small theatre company and whom Julian regards as his father (choosing Assange as his surname).

Christine and Brett Assange divorced around 1979. Christine then became involved with Leif Meynell, also known as Leif Hamilton, whom Julian Assange later described as "a member of an Australian cult" called

The Family. They separated in 1982.

Julian had a nomadic childhood, living in more than 30 Australian towns and cities by the time he reached his mid-teens,

when he settled with his mother and half-brother in

Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

.

Assange attended many schools, including

Goolmangar Primary School in

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

(1979–1983)

and

Townsville State High School

Townsville State High School, also known as Town High, is a secondary school in Railway Estate, Townsville, Queensland, Australia.

History

Townsville State High School was established in 1924 as part of the Townsville Technical College at ...

in Queensland as well as being schooled at home.

Assange studied

programming,

mathematics and

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

at

Central Queensland University

Central Queensland University (alternatively known as CQUniversity) is an Australian public university based in central Queensland. CQUniversity is the only Australian university with a campus presence in every mainland state. Its main campus ...

(1994) and the

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb no ...

(2003–2006),

but did not complete a degree.

In 1987, aged 16, Assange began

hacking under the name ''Mendax'',

supposedly taken from

Horace's ''splendide mendax'' (nobly lying). He and two others, known as "Trax" and "Prime Suspect", formed a hacking group they called "the International Subversives".

According to

David Leigh and

Luke Harding

Luke Daniel Harding (born 21 April 1968) is a British journalist who is a foreign correspondent for ''The Guardian''. He was based in Russia for ''The Guardian'' from 2007 until, returning from a stay in the UK on 5 February 2011, he was refus ...

, Assange may have been involved in the

WANK

Wank may refer to:

* WANK (computer worm), a computer worm that attacked DEC VAX/VMS systems through DECnet in 1989

* WXTY, a radio station (99.9 FM) licensed to serve Lafayette, Florida, United States, which held the call sign WANK from 2010 to 2 ...

(Worms Against Nuclear Killers) hack at

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

in 1989, but this has never been proven.

In the spring of 1991, the three hackers began targeting

MILNET

In computer networking, MILNET (fully Military Network) was the name given to the part of the ARPANET internetwork designated for unclassified United States Department of Defense traffic.DEFENSE DATA NETWORK NEWSLETTEDDN-NEWS 26 6 May 1983

MILNE ...

, a secret data network used by the US military.

Assange later said they "had control over it for two years."

The three also regularly hacked into the Australia's National University's systems.

In September 1991, Assange was discovered hacking into the Melbourne master terminal of

Nortel

Nortel Networks Corporation (Nortel), formerly Northern Telecom Limited, was a Canadian multinational telecommunications and data networking equipment manufacturer headquartered in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. It was founded in Montreal, Quebec, ...

, a Canadian

multinational telecommunications corporation.

The

Australian Federal Police tapped Assange's phone line (he was using a

modem

A modulator-demodulator or modem is a computer hardware device that converts data from a digital format into a format suitable for an analog transmission medium such as telephone or radio. A modem transmits data by Modulation#Digital modulati ...

), raided his home at the end of October and eventually charged him in 1994 with 31 counts of hacking and related crimes.

In December 1996, he pleaded guilty to 24 charges (the others were dropped) and was ordered to pay reparations of A$2,100 and released on a

good behaviour bond.

He received a lenient penalty due to the absence of malicious or mercenary intent and his disrupted childhood.

In 1993, Assange used his computing skills to help the Victoria Police Child Exploitation Unit to prosecute individuals responsible for publishing and distributing child pornography.

In the same year, he was involved in starting one of the first public

Internet service provider

An Internet service provider (ISP) is an organization that provides services for accessing, using, or participating in the Internet. ISPs can be organized in various forms, such as commercial, community-owned, non-profit, or otherwise privat ...

s in Australia, Suburbia Public Access Network.

He began programming in 1994, authoring or co-authoring the

TCP port scanner Strobe (1995), patches to the

open-source database management system

PostgreSQL (1996), the

Usenet

Usenet () is a worldwide distributed discussion system available on computers. It was developed from the general-purpose Unix-to-Unix Copy (UUCP) dial-up network architecture. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis conceived the idea in 1979, and it wa ...

caching software NNTPCache (1996), the

Rubberhose deniable encryption

In cryptography and steganography, plausibly deniable encryption describes encryption techniques where the existence of an encrypted file or message is deniable in the sense that an adversary cannot prove that the plaintext data exists.

The users ...

system (1997) (which reflected his growing interest in

cryptography

Cryptography, or cryptology (from grc, , translit=kryptós "hidden, secret"; and ''graphein'', "to write", or ''-logia'', "study", respectively), is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of adver ...

),

and Surfraw, a

command-line interface for web-based

search engines (2000). During this period, he also moderated the AUCRYPTO forum,

ran Best of Security, a website "giving advice on computer security" that had 5,000 subscribers in 1996,

and contributed research to

Suelette Dreyfus's ''

Underground

Underground most commonly refers to:

* Subterranea (geography), the regions beneath the surface of the Earth

Underground may also refer to:

Places

* The Underground (Boston), a music club in the Allston neighborhood of Boston

* The Underground ...

'' (1997), a book about Australian hackers, including the International Subversives.

In 1998, he co-founded the company Earthmen Technology.

Assange stated that he registered the domain leaks.org in 1999, but "didn't do anything with it".

He did publicise a patent granted to the

National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collect ...

in August 1999, for voice-data harvesting technology: "This patent should worry people. Everyone's overseas phone calls are or may soon be tapped, transcribed and archived in the bowels of an unaccountable foreign spy agency."

WikiLeaks

Early publications

Assange, along with a few others, established

WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks () is an international non-profit organisation that published news leaks and classified media provided by anonymous sources. Julian Assange, an Australian Internet activist, is generally described as its founder and director and ...

in Iceland in 2006.

Assange became a member of the organisation's advisory board and described himself as the editor-in-chief. From 2007 to 2010, Assange travelled continuously on WikiLeaks business, visiting Africa, Asia, Europe and North America.

During this time, the organisation published internet censorship lists,

leaks

A leak is a way (usually an opening) for fluid to escape a container or fluid-containing system, such as a tank or a ship's hull, through which the contents of the container can escape or outside matter can enter the container. Leaks are usua ...

, and classified media from anonymous

sources

Source may refer to:

Research

* Historical document

* Historical source

* Source (intelligence) or sub source, typically a confidential provider of non open-source intelligence

* Source (journalism), a person, publication, publishing institute o ...

. These publications including revelations about

drone strikes in Yemen

United States drone strikes in Yemen started after the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, when the US military attacked Islamist militant presence in Yemen, in particular Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula using drone warfare.

Wi ...

, corruption across the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

,

extrajudicial execution

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whether ...

s by Kenyan police,

2008 Tibetan unrest

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number o ...

in China, and the

"Petrogate" oil scandal in Peru.

WikiLeaks' international profile increased in 2008 when a Swiss bank,

Julius Baer, tried unsuccessfully to block the site's publication of bank records. Assange commented that financial institutions ordinarily "operate outside the rule of law", and received extensive legal support from free-speech and civil rights groups.

In September 2008, during the

2008 United States presidential election

The 2008 United States presidential election was the 56th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 2008. The Democratic ticket of Barack Obama, the junior senator from Illinois, and Joe Biden, the senior senator f ...

campaign, the contents of a Yahoo! account belonging to

Sarah Palin (the running mate of Republican presidential nominee

John McCain) were posted on WikiLeaks after being hacked into by members of

Anonymous. After briefly appearing on a blog, the membership list of the far-right

British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

was posted to WikiLeaks on 18 November 2008.

WikiLeaks released a report disclosing a "serious nuclear accident" at the Iranian

Natanz nuclear facility in 2009. According to media reports, the accident may have been the direct result of a

cyber-attack

A cyberattack is any offensive maneuver that targets computer information systems, computer networks, infrastructures, or personal computer devices. An attacker is a person or process that attempts to access data, functions, or other restricted ...

at

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

's nuclear program, carried out with the

Stuxnet

Stuxnet is a malicious computer worm first uncovered in 2010 and thought to have been in development since at least 2005. Stuxnet targets supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and is believed to be responsible for causing subs ...

computer worm, a

cyber-weapon built jointly by the United States and

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

Iraq and Afghan War logs

The material WikiLeaks published between 2006 and 2009 attracted various degrees of international attention,

but after it began publishing documents supplied by U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning, WikiLeaks became a household name.

In April 2010, WikiLeaks released the ''

Collateral Murder'' video,

which showed United States soldiers fatally shooting 18 civilians from a helicopter in Iraq, including

Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was esta ...

journalists

Namir Noor-Eldeen and his assistant

Saeed Chmagh.

[ Reuters had previously made a request to the US government for the ''Collateral Murder'' video under ]Freedom of Information

Freedom of information is freedom of a person or people to publish and consume information. Access to information is the ability for an individual to seek, receive and impart information effectively. This sometimes includes "scientific, Indigeno ...

but had been denied. Assange and others worked for a week to break the U.S. military's encryption of the video.Iraq War logs

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

, a collection of 391,832 United States Army field reports from the Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق ( Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict and the War on terror

, image ...

covering the period from 2004 to 2009. Assange said that he hoped the publication would "correct some of that attack on the truth that occurred before the war, during the war, and which has continued after the war".

Release of US diplomatic cables

In November 2010, WikiLeaks published a quarter of a million U.S. diplomatic cables, known as the "Cablegate" files. WikiLeaks initially worked with established Western media organisations, and later with smaller regional media organisations, while also publishing the cables upon which their reporting was based.United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

and other world leaders,Arab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econo ...

.

Release of unredacted cables

In 2011 a series of events compromised the security of a WikiLeaks file containing the leaked US diplomatic cables. In August 2010, Assange gave '' Guardian'' journalist David Leigh an encryption key

A key in cryptography is a piece of information, usually a string of numbers or letters that are stored in a file, which, when processed through a cryptographic algorithm, can encode or decode cryptographic data. Based on the used method, the key ...

and a URL where he could locate the full file. In February 2011 David Leigh and Luke Harding

Luke Daniel Harding (born 21 April 1968) is a British journalist who is a foreign correspondent for ''The Guardian''. He was based in Russia for ''The Guardian'' from 2007 until, returning from a stay in the UK on 5 February 2011, he was refus ...

of ''The Guardian'' published the book '' WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy'' containing the encryption key. Leigh said he believed the key was a temporary one that would expire within days. Wikileaks supporters disseminated the encrypted files to mirror site

Mirror sites or mirrors are replicas of other websites or any network node. The concept of mirroring applies to network services accessible through any protocol, such as HTTP or FTP. Such sites have different URLs than the original site, but hos ...

s in December 2010 after Wikileaks experienced cyber-attacks. When Wikileaks learned what had happened it notified the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

. On 25 August 2011, the German magazine ''Der Freitag

''Der Freitag'' (English: ''The Friday'', stylized in its logo as ''der Freitag'') is a German weekly newspaper established in 1990. It is published in Rhenish format. The place of publication is Berlin. Its publisher and editor-in-chief is Jako ...

'' published an article giving details which would enable people to piece the information together. On 2 September 2011 Wikileaks made the cables public as government intelligence agencies then knew the contents but potential targets might not. The ''Guardian'' wrote that the decision to publish the cables was made by Assange alone, a decision that it, and its four previous media partners, condemned. Glenn Greenwald wrote that "WikiLeaks decided -- quite reasonably -- that the best and safest course was to release all the cables in full, so that not only the world's intelligence agencies but everyone had them, so that steps could be taken to protect the sources and so that the information in them was equally available". The unredacted cables were released by Cryptome

Cryptome is an online library and 501(c)(3) private foundation created in 1996 by John Young and Deborah Natsios. The site collects information about freedom of expression, privacy, cryptography, dual-use technologies, national security, intelli ...

on 1 September, a day before Wikileaks did. The US cited the release in the opening of its request for extradition of Assange, saying his actions put lives at risk. The defence gave evidence it said would show that Assange was careful to protect lives.

Later publications

On 24 April 2011, WikiLeaks began publishing the Guantanamo Bay files leak

The Guantánamo Bay files leak (also known as The Guantánamo Files, or colloquially, Gitmo Files) began on 24 April 2011, when WikiLeaks, along with ''The New York Times'', NPR and ''The Guardian'' and other independent news organizations, began ...

, 779 classified reports on prisoners, past and present, held by the U.S. at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba. The documents, dated from 2002 to 2008, revealed prisoners, some of whom were coerced to confess, included children, the elderly and mentally disabled.US National Archives

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

and released them in searchable form.

By 2015, WikiLeaks had published more than ten million documents and associated analyses, and was described by Assange as "a giant library of the world's most persecuted documents".

In June 2015, WikiLeaks began publishing confidential and secret Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

n government documents.

On 25 November 2016, WikiLeaks released emails and internal documents that provided details on U.S. military operations in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

from 2009 to March 2015. In a statement accompanying the release of the "Yemen Files", Assange said about the U.S. involvement in the Yemen war: "The war in Yemen has produced 3.15million internally displaced persons. Although the United States government has provided most of the bombs and is deeply involved in the conduct of the war itself, reportage on the war in English is conspicuously rare."

Legal issues

US criminal investigation

After WikiLeaks released the Manning material, United States authorities began investigating WikiLeaks and Assange personally to prosecute them under the

After WikiLeaks released the Manning material, United States authorities began investigating WikiLeaks and Assange personally to prosecute them under the Espionage Act of 1917

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

.Eric Holder

Eric Himpton Holder Jr. (born January 21, 1951) is an American lawyer who served as the 82nd Attorney General of the United States from 2009 to 2015. Holder, serving in the administration of President Barack Obama, was the first African Amer ...

said there was "an active, ongoing criminal investigation" into WikiLeaks.Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, contacted the FBI and, after presenting a copy of Assange's passport at the American embassy, became the first informant to work for the FBI from inside WikiLeaks, and gave the FBI several hard drives he had copied from Assange and core WikiLeaks members.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' said that court and other documents suggested that Assange was being examined by a grand jury and "several government agencies", including by the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

.National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collect ...

(NSA) to designate WikiLeaks a "malicious foreign actor", thus increasing the surveillance against it.[

In January 2015, WikiLeaks issued a statement saying that three members of the organisation had received notice from Google that Google had complied with a federal warrant by a US District Court to turn over their emails and metadata on 5 April 2012. In July 2015, Assange called himself a "wanted journalist" in an open letter to the French president published in ''Le Monde''.]Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

took office, CIA director Mike Pompeo

Michael Richard Pompeo (; born December 30, 1963) is an American politician, diplomat, and businessman who served under President Donald Trump as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 2017 to 2018 and as the 70th United State ...

and Attorney General Jeff Sessions

Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III (born December 24, 1946) is an American politician and attorney who served as the 84th United States Attorney General from 2017 to 2018. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as United States ...

stepped up pursuit of Assange.

In April 2017, US officials were preparing to file formal charges against Assange. Legal scholar Steve Vladeck said prosecutors accelerated the case in 2019 due to the impending statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

on Assange's largest leaks.

Swedish sexual assault allegations

Assange visited Sweden in August 2010. On 20 August, he became the subject of sexual assault allegations from two women.

Assange visited Sweden in August 2010. On 20 August, he became the subject of sexual assault allegations from two women.Marianne Ny

''Assange v Swedish Prosecution Authority'' were the set of legal proceedings in the United Kingdom concerning the requested extradition of Julian Assange to Sweden for a "preliminary investigation" into accusations of sexual offences. The pro ...

decided to resume the preliminary investigation concerning all of the original allegations. Assange left Sweden on 27 September 2010.

On 18 November 2010, the Swedish police issued an international arrest warrant.radical feminist

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other ...

ideology". He commented that, more importantly, his case involved international politics, and that "Sweden is a U.S. satrapy

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with consid ...

."feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

."extradition

Extradition is an action wherein one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, over to the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdi ...

hearing

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is audit ...

, where he was remanded in custody

Remand, also known as pre-trial detention, preventive detention, or provisional detention, is the process of detaining a person until their trial after they have been arrested and charged with an offence. A person who is on remand is held i ...

. On 16 December 2010, at the second hearing, he was granted bail by the High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Senior Courts of England and Wales. Its name is abbreviated as EWHC (Englan ...

and released after his supporters paid £240,000 in cash and sureties. A further hearing on 24 February 2011 ruled that Assange should be extradited to Sweden. This decision was upheld by the High Court on 2 November and by the Supreme Court on 30 May the next year.

After previously stating that she could not question a suspect by video link or in the Swedish embassy, prosecutor Marianne Ny wrote to the English Crown Prosecution Service

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is the principal public agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The main responsibilities of the CPS are to provide legal advi ...

(CPS) in 2013. Her letter advised that she intended to lift the detention order and withdraw the European arrest warrant as the actions were not proportionate to the costs and seriousness of the crime. In response, the CPS tried to dissuade Ny from doing so.

In March 2015, after public criticism from other Swedish law practitioners, Ny changed her mind about interrogating Assange, who had taken refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London

The Embassy of Ecuador in London is the diplomatic mission of Ecuador in the United Kingdom. It is headed by the ambassador of Ecuador to the United Kingdom. It is located in the Knightsbridge area of London, in the Royal Borough of Kensington a ...

. These interviews, which began on 14 November 2016, involved the British police, Swedish prosecutors and Ecuadorian officials, and were eventually published online. By that time, the statute of limitations had expired on all three of the less serious allegations. Since the Swedish prosecutor had not interviewed Assange by 18 August 2015, the questioning pertained only to the open investigation of "lesser degree rape".

Ecuadorian embassy period

Entering the embassy

On 19 June 2012, the Ecuadorian foreign minister,

On 19 June 2012, the Ecuadorian foreign minister, Ricardo Patiño

Ricardo Armando Patiño Aroca (born 16 May 1954) is an Ecuadorian politician who has served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador from 2010 until 2016, under the government of President Rafael Correa. Previously he was Minister of Finance ...

, announced that Assange had applied for political asylum

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another ent ...

, that the Ecuadorian government was considering his request, and that Assange was at the Ecuadorian embassy in London

The Embassy of Ecuador in London is the diplomatic mission of Ecuador in the United Kingdom. It is headed by the ambassador of Ecuador to the United Kingdom. It is located in the Knightsbridge area of London, in the Royal Borough of Kensington a ...

.

Soon after entering the embassy, Assange asked to use the embassy's surveillance equipment to find out who had been harassing him from the street. After he was given permission, a security guard found him using the equipment and tried to stop him. El Pais reported that "they argued and struggled."William Hague

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

gave a news conference in response. He said "We will not allow Mr Assange safe passage out of the United Kingdom, nor is there any legal basis for us to do so," whilst adding, "The United Kingdom does not recognise the principle of diplomatic asylum."

Assange breached his bail conditions by taking up residence in the embassy rather than appearing in court, and faced arrest if he left. Assange's supporters, including journalist Jemima Goldsmith

Jemima Marcelle Goldsmith (born 30 January 1974; known as Jemima Khan for work) is an English screenwriter, television, film and documentary producer and the founder of Instinct Productions, a television production company. She was formerly a j ...

, journalist John Pilger

John Richard Pilger (; born 9 October 1939) is an Australian journalist, writer, scholar, and documentary filmmaker. He has been mainly based in Britain since 1962. He was also once visiting professor at Cornell University in New York.

Pilge ...

, and filmmaker Ken Loach

Kenneth Charles Loach (born 17 June 1936) is a British film director and screenwriter. His socially critical directing style and socialist ideals are evident in his film treatment of social issues such as poverty ('' Poor Cow'', 1967), homelessn ...

, forfeited £200,000 in bail.Nicola Roxon

Nicola Louise Roxon (born 1 April 1967) is a former Australian politician, who was a member of the House Representatives representing the seat of Gellibrand in Victoria for the Australian Labor Party from the 1998 federal election until he ...

, had written to Assange's lawyer, Jennifer Robinson, saying that Australia would not seek to involve itself in any international exchanges about Assange's future. She suggested that if Assange was imprisoned in the US, he could apply for an international prisoner transfer to Australia. Assange's lawyers described the letter as a "declaration of abandonment". On 16 August 2012, Patiño announced that Ecuador was granting Assange political asylum because of the threat represented by the United States secret investigation against him. In its formal statement, Ecuador said that "as a consequence of Assange's determined defense to freedom of expression and freedom of press... in any given moment, a situation may come where his life, safety or personal integrity will be in danger". Latin American states expressed support for Ecuador.

On 16 August 2012, Patiño announced that Ecuador was granting Assange political asylum because of the threat represented by the United States secret investigation against him. In its formal statement, Ecuador said that "as a consequence of Assange's determined defense to freedom of expression and freedom of press... in any given moment, a situation may come where his life, safety or personal integrity will be in danger". Latin American states expressed support for Ecuador.["OAS urges Ecuador, Britain to end row peacefully"](_blank)

. Xinhua News Agency

Xinhua News Agency (English pronunciation: )J. C. Wells: Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 3rd ed., for both British and American English, or New China News Agency, is the official state news agency of the People's Republic of China. Xinhua ...

(Beijing). 25 August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2014. Ecuadorian President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Rafael Correa

Rafael Vicente Correa Delgado (; born 6 April 1963), known as Rafael Correa, is an Ecuadorian politician and economist who served as President of Ecuador from 2007 to 2017. The leader of the PAIS Alliance political movement from its foundation ...

confirmed on 18 August that Assange could stay at the embassy indefinitely, and the following day Assange gave his first speech from the balcony. An office converted into a studio apartment, equipped with a bed, telephone, sun lamp, computer, shower, treadmill, and kitchenette

A kitchenette is a small cooking area, which usually has a refrigerator and a microwave, but may have other appliances. In some motel and hotel rooms, small apartments, college dormitories, or office buildings, a kitchenette consists of a small ref ...

, became his home until 11 April 2019.

Public positions

;WikiLeaks Party

Assange stood for the Australian Senate in the 2013 Australian federal election

The 2013 Australian federal election to elect the members of the 44th Parliament of Australia took place on 7 September 2013. The centre-right Liberal/National Coalition opposition led by Opposition leader Tony Abbott of the Liberal Party of A ...

for the newly formed WikiLeaks Party but failed to win a seat. The party experienced internal dissent over its governance and electoral tactics and was deregistered due to low membership numbers in 2015.

;Edward Snowden

In 2013, Assange and others in WikiLeaks helped whistleblower

A whistleblower (also written as whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person, often an employee, who reveals information about activity within a private or public organization that is deemed illegal, immoral, illicit, unsafe or fraudulent. Whi ...

Edward Snowden flee from US law enforcement. After the United States cancelled Snowden's passport, stranding him in Russia, they considered transporting him to Latin America on the presidential jet of a sympathetic Latin American leader. In order to throw the US off the scent, they spoke about the jet of the Bolivian president Evo Morales

Juan Evo Morales Ayma (; born 26 October 1959) is a Bolivian politician, trade union organizer, and former cocalero activist who served as the 65th president of Bolivia from 2006 to 2019. Widely regarded as the country's first president to c ...

, instead of the jet they were considering.Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

to deny the jet access to their airspace over false rumours Snowden was on board. Assange said the grounding "reveals the true nature of the relationship between Western Europe and the United States" as "a phone call from U.S. intelligence was enough to close the airspace to a booked presidential flight, which has immunity". Assange advised Snowden that he would be safest in Russia which was better able to protect its borders than Venezuela, Brazil or Ecuador.New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

government worked to establish a secret mass surveillance programme which it called "Operation Speargun". On 15 September 2014 while campaigning for Kim Dotcom

Kim Dotcom (born Kim Schmitz; 21 January 1974), also known as Kimble and Kim Tim Jim Vestor, is a German-Finnish Internet entrepreneur and political activist who resides in Glenorchy, New Zealand.

He first rose to fame in Germany in the 1990s ...

, Assange appeared via remote video link on his ''Moment of Truth'' town hall meeting held in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

, which discussed the programme. Assange said the Snowden documents showed that he had been a target of the programme and that "Operation Speargun" represented "an extreme, bizarre, Orwellian future that is being constructed secretly in New Zealand".

On 3 July 2015, Paris newspaper ''Le Monde

''Le Monde'' (; ) is a French daily afternoon newspaper. It is the main publication of Le Monde Group and reported an average circulation of 323,039 copies per issue in 2009, about 40,000 of which were sold abroad. It has had its own website si ...

'' published an open letter from Assange to French President François Hollande in which Assange urged the French government to grant him refugee status.

Other developments

In 2014, the company hired to monitor Assange warned Ecuador's government that he was "intercepting and gathering information from the embassy and the people who worked there" and that he had compromised the embassy's communications system, which WikiLeaks denied. According to El Pais, a November 2014 UC Global report said that a briefcase with a listening device was found in a room occupied by Assange. The UC Global report said that proved "the suspicion that he is listening in on diplomatic personnel, in this case against the ambassador and the people around him, in an effort to obtain privileged information that could be used to maintain his status in the embassy." According to ambassador Falconí, Assange was evasive when asked about the briefcase.Crown Prosecution Service

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is the principal public agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The main responsibilities of the CPS are to provide legal advi ...

dissuaded them from doing so.

Assange's lawyers invited the Swedish prosecutor four times to come and question him at the embassy, but the offer was refused. In March 2015, faced with the prospect of the Swedish statute of limitations expiring for some of the allegations, the prosecutor relented and agreed to question Assange in the Ecuadorean embassy. The UK agreed to the interview in May awaiting Ecuadorean approval. In 2015, ''La Repubblica

''la Repubblica'' (; the Republic) is an Italian daily general-interest newspaper. It was founded in 1976 in Rome by Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso (now known as GEDI Gruppo Editoriale) and led by Eugenio Scalfari, Carlo Caracciolo and Arnol ...

'' stated that it had evidence of the UK's role via the English Crown Prosecution Service

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is the principal public agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. It is headed by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The main responsibilities of the CPS are to provide legal advi ...

(CPS) in creating the "legal and diplomatic quagmire" which prevented Assange from leaving the Ecuadorian embassy. ''La Repubblica'' sued the CPS in 2017 to obtain further information but its case was rejected with the judge saying "the need for the British authorities to protect the confidentiality of the extradition process outweighs the public interest of the press to know".Working Group on Arbitrary Detention The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) is a body of independent human rights experts that investigate cases of arbitrary arrest and detention. Arbitrary arrest and detention is the imprisonment or detainment of an individual, by a State, wi ...

concluded that Assange had been subject to arbitrary detention

Arbitrary arrest and arbitrary detention are the arrest or detention of an individual in a case in which there is no likelihood or evidence that they committed a crime against legal statute, or in which there has been no proper due process of law ...

by the UK and Swedish Governments since 7 December 2010, including his time in prison, on conditional bail and in the Ecuadorian embassy. The Working Group said Assange should be allowed to walk free and be given compensation. The UK and Swedish governments denied the charge of detaining Assange arbitrarily. The UK Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond

Philip Hammond, Baron Hammond of Runnymede (born 4 December 1955) is a British politician and life peer who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2016 to 2019, Foreign Secretary from 2014 to 2016, and Defence Secretary from 2011 to 2014. ...

, said the charge was "ridiculous" and that the group was "made up of lay people", and called Assange a "fugitive from justice

A fugitive (or runaway) is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also kno ...

" who "can come out any time he chooses", and called the panel's ruling "flawed in law". Swedish prosecutors called the group's charge irrelevant. The UK said it would arrest Assange should he leave the embassy. Mark Ellis, executive director of the International Bar Association

The International Bar Association (IBA), founded in 1947, is a bar association of international legal practitioners, bar associations and law societies. The IBA currently has a membership of more than 80,000 individual lawyers and 190 bar associa ...

, stated that the finding is "not binding on British law". US legal scholar Noah Feldman

Noah R. Feldman (born May 22, 1970) is an American academic and legal scholar. He is the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and chairman of the Society of Fellows at Harvard University. He is the author of 10 books, host of ...

described the Working Group's conclusion as astonishing, summarising it as "Assange might be charged with a crime in the US. Ecuador thinks charging him with violating national security law would amount to 'political persecution' or worse. Therefore, Sweden must give up on its claims to try him for rape, and Britain must ignore the Swedes' arrest warrant and let him leave the country."

In September 2016

2016 U.S. presidential election

During the 2016 US Democratic Party

The Democratic Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States. Founded in 1828, it was predominantly built by Martin Van Buren, who assembled a wide cadre of politicians in every state behind war hero Andre ...

presidential primaries, WikiLeaks hosted a searchable database of emails

Electronic mail (email or e-mail) is a method of exchanging messages ("mail") between people using electronic devices. Email was thus conceived as the electronic ( digital) version of, or counterpart to, mail, at a time when "mail" mean ...

sent or received by presidential candidate Hillary Clinton while she was Secretary of State. The emails had been previously released by the US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

under a Freedom of information

Freedom of information is freedom of a person or people to publish and consume information. Access to information is the ability for an individual to seek, receive and impart information effectively. This sometimes includes "scientific, Indigeno ...

request in February 2016.FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

investigation of Clinton for using a private email server for classified documents while she was US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

.Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

is like choosing between cholera or gonorrhoea. "Personally, I would prefer neither."Election Day

Election day or polling day is the day on which general elections are held. In many countries, general elections are always held on a Saturday or Sunday, to enable as many voters as possible to participate; while in other countries elections a ...

statement, Assange criticised both Clinton and Trump, saying that "The Democratic and Republican candidates have both expressed hostility towards whistleblowers."

On 22 July 2016, WikiLeaks released emails and documents from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in which the DNC seemingly presented ways of undercutting Clinton's competitor Bernie Sanders and showed apparent favouritism towards Clinton. The release led to the resignation of DNC chairwoman

On 22 July 2016, WikiLeaks released emails and documents from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in which the DNC seemingly presented ways of undercutting Clinton's competitor Bernie Sanders and showed apparent favouritism towards Clinton. The release led to the resignation of DNC chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz

Deborah Wasserman Schultz (née Wasserman; born September 27, 1966) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative from , first elected to Congress in 2004. A member of the Democratic Party, she is a former chair of the Democrat ...

and an apology to Sanders from the DNC. ''The New York Times'' wrote that Assange had timed the release to coincide with the 2016 Democratic National Convention

The 2016 Democratic National Convention was a presidential nominating convention, held at the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from July 25 to 28, 2016. The convention gathered delegates of the Democratic Party, the majo ...

because he believed Clinton had pushed for his indictment and he regarded her as a "liberal war hawk

In politics, a war hawk, or simply hawk, is someone who favors war or continuing to escalate an existing conflict as opposed to other solutions. War hawks are the opposite of doves. The terms are derived by analogy with the birds of the same name ...

".John Podesta

John David Podesta Jr. (born January 8, 1949) is an American Political consulting, political consultant who has served as Senior Advisor to the President of the United States, Senior Advisor to President Joe Biden for clean energy innovation an ...

.The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' reported that former WikiLeaks insiders said Assange wasn't bluffing and had damaging information about Ecuador.Donald Trump Jr.

Donald John Trump Jr. (born December 31, 1977) is an American political activist, businessman, author, and former television presenter. He is the eldest child of Donald Trump, 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021, and his firs ...

provided evidence of correspondence with WikiLeaks' Twitter account during the 2016 presidential election to congressional investigators looking into Russian interference in the election. Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

, together with several other agencies, concluded that Russian intelligence agencies hacked the DNC servers, as well as Podesta's email account, and provided the information to WikiLeaks to bolster Trump's election campaign.Jill Stein

Jill Ellen Stein (born May 14, 1950) is an American physician, activist, and former political candidate. She was the Green Party's nominee for President of the United States in the 2012 and 2016 elections and the Green-Rainbow Party's candidat ...

, or Gary Johnson's campaign.[

In April 2018, the DNC sued WikiLeaks for the theft of the DNC's information under various ]Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and US federal statutes. It accused WikiLeaks and Russia of a "brazen attack on American democracy". The Committee to Protect Journalists

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is an American independent non-profit, non-governmental organization, based in New York City, New York, with correspondents around the world. CPJ promotes press freedom and defends the rights of journ ...

said that the lawsuit raised several important press freedom questions.with prejudice

Prejudice is a legal term with different meanings, which depend on whether it is used in criminal, civil, or common law. In legal context, "prejudice" differs from the more common use of the word and so the term has specific technical meanings. ...

in July 2019. Judge John Koeltl

John George Koeltl (; born October 25, 1945) is a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in Manhattan.

Education

Koeltl was born in New York City. He graduated from Regis High Scho ...

said that WikiLeaks "did not participate in any wrongdoing in obtaining the materials in the first place" and were therefore within the law in publishing the information.

Seth Rich

In a July 2016 interview on Dutch television, Assange hinted that DNC staffer Seth Rich

Seth,; el, Σήθ ''Sḗth''; ; "placed", "appointed") in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Mandaeism, and Sethianism, was the third son of Adam and Eve and brother of Cain and Abel, their only other child mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible. A ...

was the source of the DNC emails and that Rich had been killed as a result. Seeking clarification, the interviewer asked Assange whether Rich's killing was "simply a murder," to which Assange answered, "No. There's no finding. So, I'm suggesting that our sources take risks, and they become concerned to see things occurring like that." WikiLeaks offered a $20,000 reward for information about his murder and wrote: "We treat threats toward any suspected source of WikiLeaks with extreme gravity. This should not be taken to imply that Seth Rich was a source to WikiLeaks or to imply that his murder is connected to our publications."Fox News

The Fox News Channel, abbreviated FNC, commonly known as Fox News, and stylized in all caps, is an American multinational conservative cable news television channel based in New York City. It is owned by Fox News Media, which itself is owne ...

, ''The Washington Times

''The Washington Times'' is an American conservative daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., that covers general interest topics with a particular emphasis on national politics. Its broadsheet daily edition is distributed throughou ...

'' and conspiracy website ''InfoWars

''InfoWars'' is an American far-right conspiracy theory and fake news website owned by Alex Jones. It was founded in 1999, and operates under Free Speech Systems LLC.

Talk shows and other content for the site are created primarily in stud ...

''

Later years in the embassy

In March 2017, WikiLeaks began releasing the largest leak of CIA documents in history, codenamed

In March 2017, WikiLeaks began releasing the largest leak of CIA documents in history, codenamed Vault 7

Vault 7 is a series of documents that WikiLeaks began to publish on 7 March 2017, detailing the activities and capabilities of the United States Central Intelligence Agency to perform electronic surveillance and cyber warfare. The files, dating fr ...

. The documents included details of the CIA's hacking capabilities and software tools used to break into smartphones, computers and other Internet-connected devices.Mike Pompeo

Michael Richard Pompeo (; born December 30, 1963) is an American politician, diplomat, and businessman who served under President Donald Trump as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 2017 to 2018 and as the 70th United State ...

called WikiLeaks "a non-state hostile intelligence service

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement, national security, military, public safety, and foreign policy objectives.

Means of informatio ...

often abetted by state actors like Russia". Assange accused the CIA of trying to "subvert" his right to freedom of speech. According to former intelligence officials, in the wake of the Vault7 leaks, the CIA plotted to kidnap

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the p ...

Assange from Ecuador's London embassy, and some senior officials discussed his potential assassination. Yahoo! News

Yahoo! News is a news website that originated as an internet-based news aggregator by Yahoo!. The site was created by a Yahoo! software engineer named Brad Clawsie in August 1996. Articles originally came from news services such as the Associate ...

found "no indication that the most extreme measures targeting Assange were ever approved." Some of its sources stated that they had alerted House and Senate intelligence committees to the plans that Pompeo was suggesting.High Court of Justice

The High Court of Justice in London, known properly as His Majesty's High Court of Justice in England, together with the Court of Appeal and the Crown Court, are the Senior Courts of England and Wales. Its name is abbreviated as EWHC (Englan ...

in London as it considered the U.S. appeal of a lower court's ruling that Assange could not be extradited to face charges in the U.S.

On 6 June 2017, Assange tweeted his support for NSA leaker Reality Winner

Reality Leigh Winner (born December 4, 1991) is an American former enlisted US Air Force member and NSA translator. In 2018, she was given the longest prison sentence ever imposed for unauthorized release of government information to the media a ...

, who had been arrested three days earlier. Winner had been identified in part because a reporter from ''The Intercept

''The Intercept'' is an American left-wing news website founded by Glenn Greenwald, Jeremy Scahill, Laura Poitras and funded by billionaire eBay co-founder Pierre Omidyar. Its current editor is Betsy Reed. The publication initially reporte ...

'' showed a leaked document to the government without removing possibly incriminating evidence about its leaker. WikiLeaks later offered a $10,000 reward for information about the reporter responsible.

On 16 August 2017, US Republican congressman Dana Rohrabacher

Dana Tyrone Rohrabacher (; born June 21, 1947) is a former American politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1989 to 2019. A Republican, he represented for the last three terms of his House tenure.

Rohrabacher ran for r ...

visited Assange and told him that Trump would pardon him on condition that he would agree to say that Russia was not involved in the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak

The 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak is a collection of Democratic National Committee (DNC) emails stolen by one or more hackers operating under the pseudonym " Guccifer 2.0" who are alleged to be Russian intelligence agency hacker ...

s.Qatar diplomatic crisis

The Qatar diplomatic crisis was a diplomatic incident in the Middle East that began on 5 June 2017 when Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt severed diplomatic relations with Qatar and banned Qatar-registered planes and ship ...

, Dubai-based ''Al Arabiya

Arabiya ( ar, العربية, transliterated: '; meaning "The Arabic One" or "The Arab One") is an international Arabic news television channel, currently based in Dubai, that is operated by the media conglomerate MBC.

The channel is a fl ...

'' said Assange had refrained from publishing two cables about Qatar after negotiations between WikiLeaks and Qatar. Assange said ''Al Arabiya'' had been publishing "increasingly absurd fabrications" during the dispute.

Ecuador granted Assange citizenship in December 2017, and on the 19th approved a "special designation in favor of Mr. Julian Assange so that he can carry out functions at the Ecuadorean Embassy in Russia." On the 21st, Britain’s Foreign Office wrote that it did not recognise Assange as a diplomat, and that he did not have "any type of privileges and immunities under the Vienna Convention." The citizenship was later revoked over unpaid fees and problems in the naturalisation papers, which allegedly had multiple inconsistencies, different signatures, and the possible alteration of documents. Assange's lawyer said the decision had been made without due process, but Ecuador's Foreign Ministry said the Pichincha Court for Contentious Administrative Matters had "acted independently and followed due process in a case that took place during the previous government and that was raised by the same previous government."Emma Arbuthnot

Emma Louise Arbuthnot, Baroness Arbuthnot of Edrom (née Broadbent), known professionally as Mrs Justice Arbuthnot, is a British High Court judge (England and Wales), High Court judge.

Early life and education

Emma Louise Broadbent, daughter o ...

ruled that the arrest warrant should remain in place.Carles Puigdemont

Carles Puigdemont i Casamajó (; born 29 December 1962) is a Catalan politician and journalist from Spain. Since 2019 he has served as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP). A former mayor of Girona, Puigdemont served as President of Catalo ...

. On 28 March 2018, Ecuador responded by cutting Assange's internet connection because his social media posts put at risk Ecuador's relations with European nations. In May 2018, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' reported that over five years Ecuador had spent at least $5million (£3.7m) to protect Assange, employing a security company and undercover agents to monitor his visitors, embassy staff and the British police. Ecuador reportedly devised plans to help Assange escape should British police forcibly enter the embassy to seize him. ''The Guardian'' reported that by 2014 Assange had compromised the embassy's communications system. WikiLeaks described the allegation as "an anonymous libel aligned with the current UK-US government onslaught against Mr Assange". In July 2018, President Moreno said that he wanted Assange out of the embassy provided that Assange's life was not in danger. By October 2018, Assange's communications were partially restored.

On 16 October 2018, members of Congress from the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs

The United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, also known as the House Foreign Affairs Committee, is a standing committee of the U.S. House of Representatives with jurisdiction over bills and investigations concerning the foreign affairs ...

wrote an open letter to President Moreno, which described Assange as a dangerous criminal. It stated that progress between the US and Ecuador in economic cooperation, counter-narcotics assistance, and the return of a USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is an independent agency of the U.S. federal government that is primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance. With a budget of over $27 bi ...

mission to Ecuador depended on Assange being handed over to the authorities.

In October 2018, Assange sued the government of Ecuador for violating his "fundamental rights and freedoms" by threatening to remove his protection and cut off his access to the outside world, refusing him visits from journalists and human rights organisations and installing signal jammers to prevent phone calls and internet access.Pamela Anderson

Pamela Denise Anderson (born July 1, 1967) is a Canadian-American actress and model. She is best known for her glamour modeling work in ''Playboy'' magazine and for her appearances on the television series ''Baywatch'' (1992–1997).

Anders ...

, a close friend and regular visitor of Assange, gave an interview in which she asked the Australian prime minister, Scott Morrison

Scott John Morrison (; born 13 May 1968) is an Australian politician. He served as the 30th prime minister of Australia and as Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia from 2018 to 2022, and is currently the member of parliament (MP) for th ...

, to defend Assange. Morrison rejected the request with a response Anderson considered "smutty". Anderson responded that " ther than making lewd suggestions about me, perhaps you should instead think about what you are going to say to millions of Australians when one of their own is marched in an orange jumpsuit to Guantanamo Bay – for publishing the truth. You can prevent this."

On 21 December 2018, the UN's Working Group on Arbitrary Detention The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) is a body of independent human rights experts that investigate cases of arbitrary arrest and detention. Arbitrary arrest and detention is the imprisonment or detainment of an individual, by a State, wi ...