teleost on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Teleostei (;

The

The

There are over 26,000 species of teleosts, in about 40

There are over 26,000 species of teleosts, in about 40  Open water fish are usually streamlined like

Open water fish are usually streamlined like

Some teleosts are parasites.

Some teleosts are parasites.  Some species, such as

Some species, such as

Of the major groups of teleosts, the Elopomorpha, Clupeomorpha and Percomorpha (perches, tunas and many others) all have a worldwide distribution and are mainly marine; the Ostariophysi and Osteoglossomorpha are worldwide but mainly freshwater, the latter mainly in the tropics; the Atherinomorpha (guppies, etc.) have a worldwide distribution, both fresh and salt, but are surface-dwellers. In contrast, the Esociformes (pikes) are limited to freshwater in the Northern Hemisphere, while the Salmoniformes (

Of the major groups of teleosts, the Elopomorpha, Clupeomorpha and Percomorpha (perches, tunas and many others) all have a worldwide distribution and are mainly marine; the Ostariophysi and Osteoglossomorpha are worldwide but mainly freshwater, the latter mainly in the tropics; the Atherinomorpha (guppies, etc.) have a worldwide distribution, both fresh and salt, but are surface-dwellers. In contrast, the Esociformes (pikes) are limited to freshwater in the Northern Hemisphere, while the Salmoniformes (

The major means of respiration in teleosts, as in most other fish, is the transfer of gases over the surface of the gills as water is drawn in through the mouth and pumped out through the gills. Apart from the

The major means of respiration in teleosts, as in most other fish, is the transfer of gases over the surface of the gills as water is drawn in through the mouth and pumped out through the gills. Apart from the

Teleosts possess highly developed sensory organs. Nearly all daylight fish have colour vision at least as good as a normal human's. Many fish also have

Teleosts possess highly developed sensory organs. Nearly all daylight fish have colour vision at least as good as a normal human's. Many fish also have

The skin of a teleost is largely impermeable to water, and the main interface between the fish's body and its surroundings is the gills. In freshwater, teleost fish gain water across their gills by

The skin of a teleost is largely impermeable to water, and the main interface between the fish's body and its surroundings is the gills. In freshwater, teleost fish gain water across their gills by

The body of a teleost is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference, or they will sink. Many teleosts have a swim bladder that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases to allow them to stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. In the more primitive groups like some

The body of a teleost is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference, or they will sink. Many teleosts have a swim bladder that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases to allow them to stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. In the more primitive groups like some

A typical teleost fish has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, and locomotion is generally provided by a lateral undulation of the hindmost part of the trunk and the tail, propelling the fish through the water. There are many exceptions to this method of locomotion, especially where speed is not the main objective; among rocks and on

A typical teleost fish has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, and locomotion is generally provided by a lateral undulation of the hindmost part of the trunk and the tail, propelling the fish through the water. There are many exceptions to this method of locomotion, especially where speed is not the main objective; among rocks and on

88 percent of teleost species are

88 percent of teleost species are

Teleosts may spawn in the water column or, more commonly, on the substrate. Water column spawners are mostly limited to coral reefs; the fish will rush towards the surface and release their gametes. This appears to protect the eggs from some predators and allow them to disperse widely via currents. They receive no

Teleosts may spawn in the water column or, more commonly, on the substrate. Water column spawners are mostly limited to coral reefs; the fish will rush towards the surface and release their gametes. This appears to protect the eggs from some predators and allow them to disperse widely via currents. They receive no  Of the oviparous teleosts, most (79 percent) do not provide parental care. Male care is far more common than female care. Male territoriality "preadapts" a species to evolve male parental care. One unusual example of female parental care is in discuses, which provide nutrients for their developing young in the form of mucus. Some teleost species have their eggs or young attached to or carried in their bodies. For

Of the oviparous teleosts, most (79 percent) do not provide parental care. Male care is far more common than female care. Male territoriality "preadapts" a species to evolve male parental care. One unusual example of female parental care is in discuses, which provide nutrients for their developing young in the form of mucus. Some teleost species have their eggs or young attached to or carried in their bodies. For

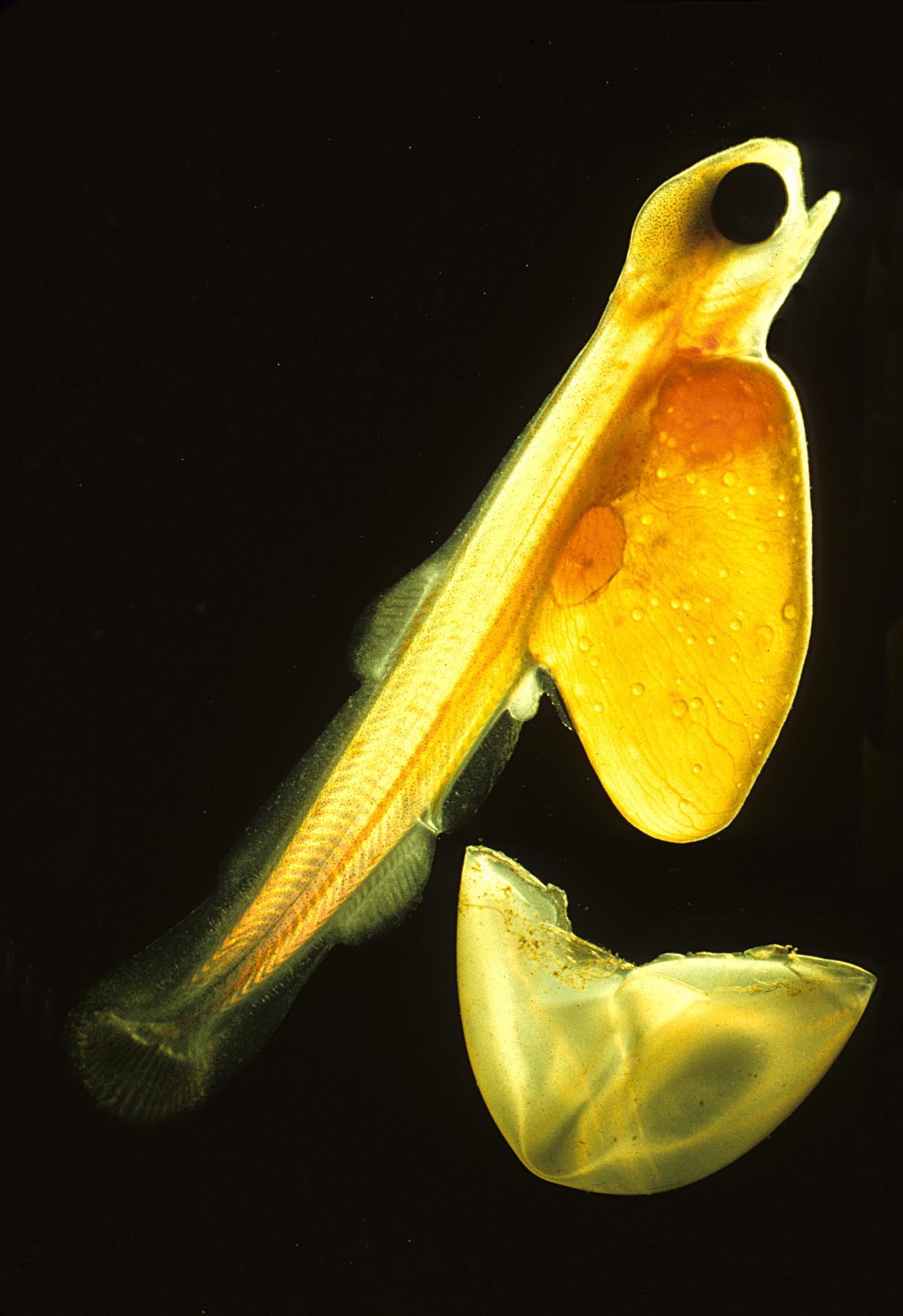

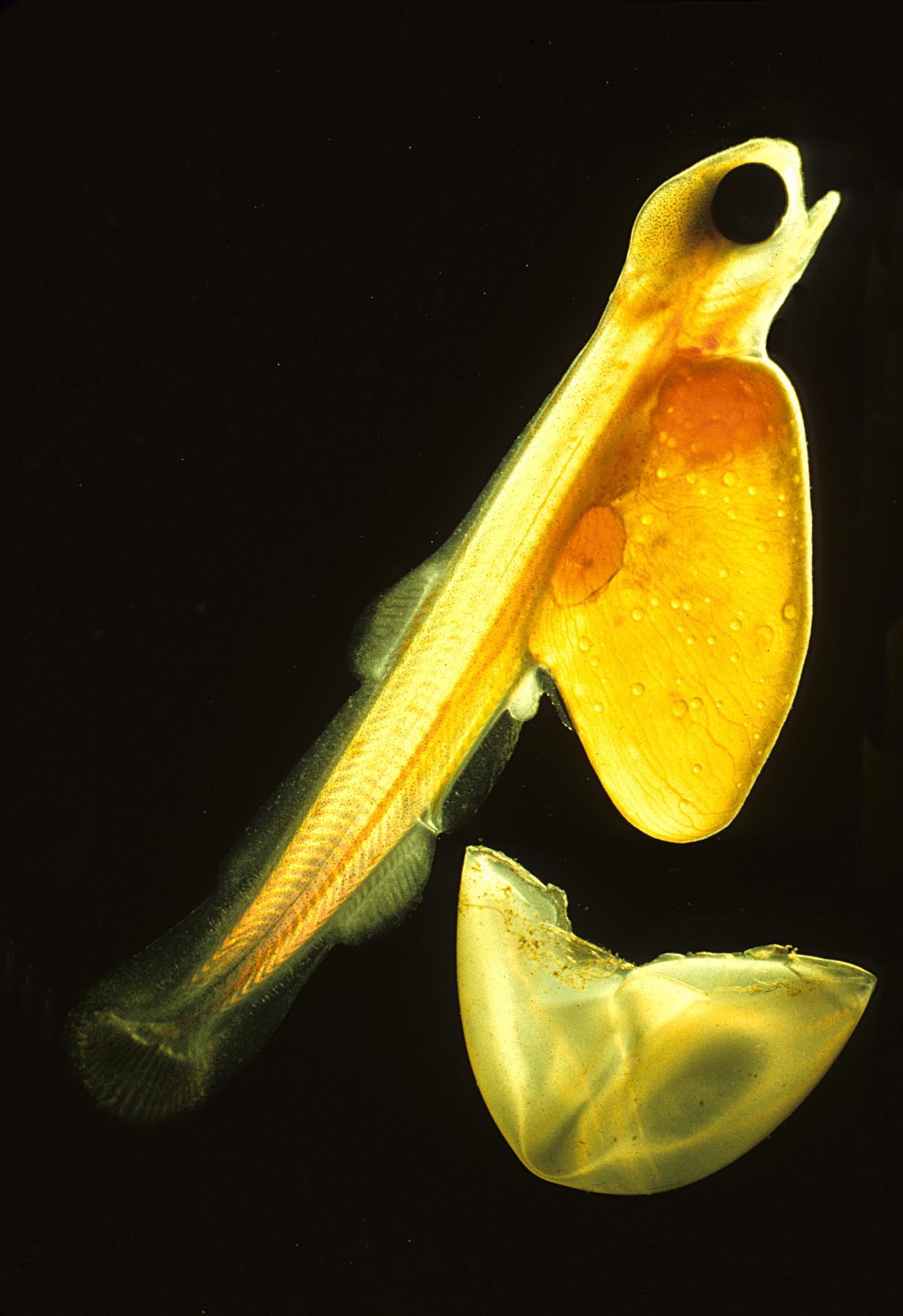

Teleosts have four major life stages: the egg, the larva, the juvenile and the adult. Species may begin life in a pelagic environment or a

Teleosts have four major life stages: the egg, the larva, the juvenile and the adult. Species may begin life in a pelagic environment or a

Many teleosts form

Many teleosts form

Teleosts are economically important in different ways. They are captured for food around the world. A small number of species such as

Teleosts are economically important in different ways. They are captured for food around the world. A small number of species such as

Human activities have affected stocks of many species of teleost, through

Human activities have affected stocks of many species of teleost, through

A few teleosts are dangerous. Some, like eeltail catfish ( Plotosidae), scorpionfish (

A few teleosts are dangerous. Some, like eeltail catfish ( Plotosidae), scorpionfish (

Maler der Grabkammer des Menna 003.jpg, Wall painting of fishing, Tomb of Menna the scribe, Thebes, Ancient Egypt, c. 1422–1411 BC

Antonio tanari, pesci, 1610-30 ca..JPG, Italian Renaissance: ''Fish'', Antonio Tanari, c. 1610–1630, in the Medici Villa, Poggio a Caiano

Willem Ormea & Abraham Willaerts - Vis Stilleven met stormachtige zeeën.jpg, Dutch Golden Age painting: ''Fish Still Life with Stormy Seas'', Willem Ormea and Abraham Willaerts, 1636

Mandarin Fish by Bian Shoumin.jpg, ''Mandarin Fish'' by Bian Shoumin, Qing dynasty, 18th century

Saito Oniwakamaru.jpg, Saito Oniwakamaru fights a giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 19th century

Van Gogh - Stillleben mit Makrelen, Zitronen und Tomaten.jpeg, ''Still Life with Mackerel, Lemons and Tomato'', Vincent van Gogh, 1886

Haeckel Teleostei.jpg, ''Teleostei'' by Ernst Haeckel, 1904. Four species, surrounded by scales

Haeckel Ostraciontes.jpg, ''Ostraciontes'' by Ernst Haeckel, 1904. Ten teleosts, with ''Lactoria cornuta'' in centre.

Fish Magic.JPG, ''Fish Magic'', Paul Klee, oil and watercolour varnished, 1925

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass

In biological classification, class ( la, classis) is a taxonomic rank, as well as a taxonomic unit, a taxon, in that rank. It is a group of related taxonomic orders. Other well-known ranks in descending order of size are life, domain, kingdo ...

in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. Teleosts are arranged into about 40 orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

and 448 families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

. Over 26,000 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

have been described. Teleosts range from giant oarfish

The giant oarfish (''Regalecus glesne'') is a species of oarfish of the family Regalecidae. It is an oceanodromous species with a worldwide distribution, excluding polar regions. Other common names include Pacific oarfish, king of herrings, ribb ...

measuring or more, and ocean sunfish

The ocean sunfish or common mola (''Mola mola'') is one of the largest bony fish in the world. It was misidentified as the heaviest bony fish, which was actually a different species, ''Mola alexandrini''. Adults typically weigh between . The spe ...

weighing over , to the minute male anglerfish

The anglerfish are fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (). They are bony fish named for their characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified luminescent fin ray (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish. The luminescence ...

''Photocorynus spiniceps

''Photocorynus spiniceps'' is a species of anglerfish in the family Linophrynidae. It is in the monotypic genus ''Photocorynus''.

The known mature male individuals are 6.2–7.3 millimeters (0.25-0.3 inches), smaller than any other m ...

'', just long. Including not only torpedo-shaped fish built for speed, teleosts can be flattened vertically or horizontally, be elongated cylinders or take specialised shapes as in anglerfish and seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or " ...

s.

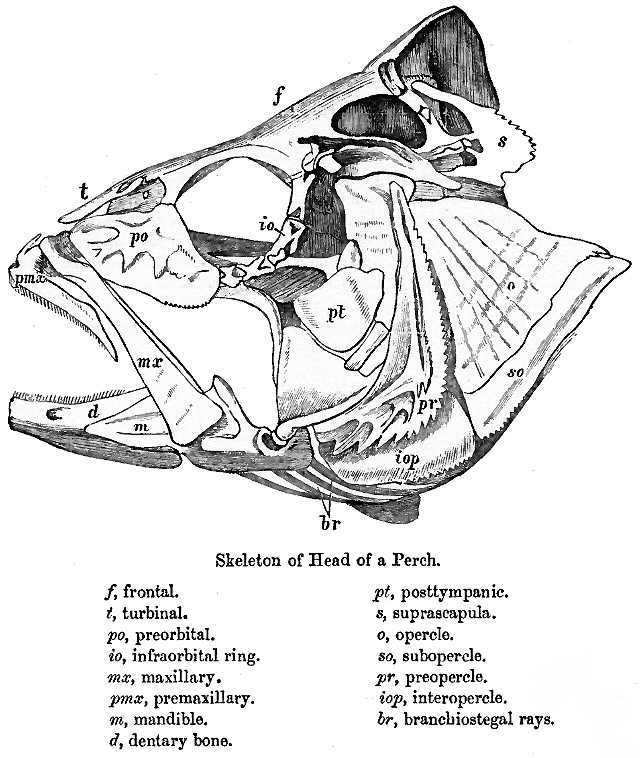

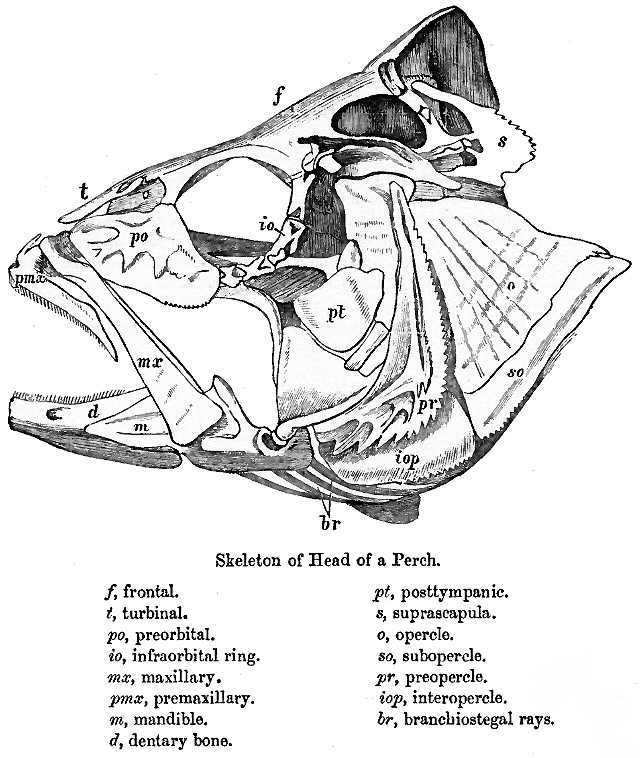

The difference between teleosts and other bony fish lies mainly in their jaw bones; teleosts have a movable premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

and corresponding modifications in the jaw musculature which make it possible for them to protrude their jaws outwards from the mouth. This is of great advantage, enabling them to grab prey and draw it into the mouth. In more derived

Derive may refer to:

* Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguatio ...

teleosts, the enlarged premaxilla is the main tooth-bearing bone, and the maxilla, which is attached to the lower jaw, acts as a lever, pushing and pulling the premaxilla as the mouth is opened and closed. Other bones further back in the mouth serve to grind and swallow food. Another difference is that the upper and lower lobes of the tail (caudal) fin are about equal in size. The spine ends at the caudal peduncle

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

, distinguishing this group from other fish in which the spine extends into the upper lobe of the tail fin.

Teleosts have adopted a range of reproductive strategies. Most use external fertilisation: the female lays a batch of eggs, the male fertilises them and the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e develop without any further parental involvement. A fair proportion of teleosts are sequential hermaphrodite

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrate ...

s, starting life as females and transitioning to males at some stage, with a few species reversing this process. A small percentage of teleosts are viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the m ...

and some provide parental care with typically the male fish guarding a nest and fanning the eggs to keep them well-oxygenated.

Teleosts are economically important to humans, as is shown by their depiction in art over the centuries. The fishing industry

The fishing industry includes any industry or activity concerned with taking, culturing, processing, preserving, storing, transporting, marketing or selling fish or fish products. It is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization as including ...

harvests them for food, and anglers attempt to capture them for sport. Some species are farmed

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

commercially, and this method of production is likely to be increasingly important in the future. Others are kept in aquarium

An aquarium (plural: ''aquariums'' or ''aquaria'') is a vivarium of any size having at least one transparent side in which aquatic plants or animals are kept and displayed. Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, aq ...

s or used in research, especially in the fields of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

and developmental biology

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of Regeneration (biology), regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and di ...

.

Anatomy

Distinguishing

The ruling made by the judge or panel of judges must be based on the evidence at hand and the standard binding precedents covering the subject-matter (they must be ''followed'').

Definition

In law, to distinguish a case means a court decides th ...

features of the teleosts are mobile premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

, elongated neural arch

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

es at the end of the caudal fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

and unpaired basibranchial toothplates. The premaxilla is unattached to the neurocranium

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, or brain-pan is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calvaria (skull), ...

(braincase); it plays a role in protruding the mouth and creating a circular opening. This lowers the pressure inside the mouth, sucking the prey inside. The lower jaw and maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

are then pulled back to close the mouth, and the fish is able to grasp the prey. By contrast, mere closure of the jaws would risk pushing food out of the mouth. In more advanced teleosts, the premaxilla is enlarged and has teeth, while the maxilla is toothless. The maxilla functions to push both the premaxilla and the lower jaw forward. To open the mouth, an adductor muscle pulls back the top of the maxilla, pushing the lower jaw forward. In addition, the maxilla rotates slightly, which pushes forward a bony process that interlocks with the premaxilla.

The

The pharyngeal jaw

Pharyngeal jaws are a "second set" of jaws contained within an animal's throat, or pharynx, distinct from the primary or oral jaws. They are believed to have originated as modified gill arches, in much the same way as oral jaws. Originally hypo ...

s of teleosts, a second set of jaws contained within the throat, are composed of five branchial arches, loops of bone which support the gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s. The first three arches include a single basibranchial surrounded by two hypobranchials, ceratobranchials, epibranchials and pharyngobranchials. The median basibranchial is covered by a toothplate. The fourth arch is composed of pairs of ceratobranchials and epibranchials, and sometimes additionally, some pharyngobranchials and a basibranchial. The base of the lower pharyngeal jaws is formed by the fifth ceratobranchials while the second, third and fourth pharyngobranchials create the base of the upper. In the more basal teleosts the pharyngeal jaws consist of well-separated thin parts that attach to the neurocranium, pectoral girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of t ...

, and hyoid bar. Their function is limited to merely transporting food, and they rely mostly on lower pharyngeal jaw activity. In more derived teleosts the jaws are more powerful, with left and right ceratobranchials fusing to become one lower jaw; the pharyngobranchials fuse to create a large upper jaw that articulates with the neurocranium. They have also developed a muscle that allows the pharyngeal jaws to have a role in grinding food in addition to transporting it.

The caudal fin is homocercal

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as see ...

, meaning the upper and lower lobes are about equal in size. The spine ends at the caudal peduncle, the base of the caudal fin, distinguishing this group from those in which the spine extends into the upper lobe of the caudal fin, such as most fish from the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

(541 to 252 million years ago). The neural arches are elongated to form uroneurals which provide support for this upper lobe. In addition, the hypurals, bones that form a flattened plate at the posterior end of the vertebral column, are enlarged providing further support for the caudal fin.

In general, teleosts tend to be quicker and more flexible than more basal bony fishes. Their skeletal structure has evolved towards greater lightness. While teleost bones are well calcified

Calcification is the accumulation of calcium salts in a body tissue. It normally occurs in the formation of bone, but calcium can be deposited abnormally in soft tissue,Miller, J. D. Cardiovascular calcification: Orbicular origins. ''Nature Mat ...

, they are constructed from a scaffolding of struts, rather than the dense cancellous bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, and ...

s of holostean

Holostei is a group of ray-finned bony fish. It is divided into two major clades, the Halecomorphi, represented by a single living species, the bowfin ('' Amia calva''), as well as the Ginglymodi, the sole living representatives being the gars ...

fish. In addition, the lower jaw of the teleost is reduced to just three bones; the dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

, the angular bone The angular is a large bone in the lower jaw (mandible) of amphibians and reptiles (birds included), which is connected to all other lower jaw bones: the dentary (which is the entire lower jaw in mammals), the splenial, the suprangular, and the art ...

and the articular bone

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two ...

.

Evolution and phylogeny

External relationships

The teleosts were first recognised as a distinct group by the Germanichthyologist

Ichthyology is the branch of zoology devoted to the study of fish, including bony fish ( Osteichthyes), cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), and jawless fish (Agnatha). According to FishBase, 33,400 species of fish had been described as of Octobe ...

Johannes Peter Müller

Johannes Peter Müller (14 July 1801 – 28 April 1858) was a German physiologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, ichthyology, ichthyologist, and herpetology, herpetologist, known not only for his discoveries but also for his ability ...

in 1845. The name is from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''teleios'', "complete" + ''osteon'', "bone". Müller based this classification on certain soft tissue characteristics, which would prove to be problematic, as it did not take into account the distinguishing features of fossil teleosts. In 1966, Greenwood et al. provided a more solid classification. The oldest fossils of teleosteomorphs (the stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

from which teleosts later evolved) date back to the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

('' Prohalecites'', '' Pholidophorus''). However, it has been suggested that teleosts probably first evolved already during the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

era

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Comp ...

. During the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

and Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configura ...

eras they diversified widely, and as a result, 96% of all living fish species are teleosts.

The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

below shows the evolutionary relationships

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

of the teleosts to other extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

s of bony fish, and to the four-limbed vertebrates (tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids (pelycosaurs, extinct theraps ...

s) that evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

from a related group of bony fish during the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (or rhetorical period), a concept ...

. Approximate divergence dates (in millions of years, mya) are from Near et al., 2012.

Internal relationships

The phylogeny of the teleosts has been subject to long debate, without consensus on either theirphylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

or the timing of the emergence of the major groups before the application of modern DNA-based cladistic analysis. Near et al. (2012) explored the phylogeny and divergence times of every major lineage, analysing the DNA sequences of 9 unlinked genes in 232 species. They obtained well-resolved phylogenies with strong support for the nodes (so, the pattern of branching shown is likely to be correct). They calibrated (set actual values for) branching times in this tree from 36 reliable measurements of absolute time from the fossil record. The teleosts are divided into the major clades shown on the cladogram, with dates, following Near et al.

The most diverse group of teleost fish today are the Percomorpha, which include, among others, the tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max length: ...

, seahorses

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or " ...

, gobies

Gobiidae or gobies is a family of bony fish in the order Gobiiformes, one of the largest fish families comprising more than 2,000 species in more than 200 genera. Most of gobiid fish are relatively small, typically less than in length, and the ...

, cichlids

Cichlids are fish from the family (biology), family Cichlidae in the order Cichliformes. Cichlids were traditionally classed in a suborder, the Labroidei, along with the wrasses (Labridae), in the order Perciformes, but molecular studies have c ...

, flatfish

A flatfish is a member of the Ray-finned fish, ray-finned demersal fish order (biology), order Pleuronectiformes, also called the Heterosomata, sometimes classified as a suborder of Perciformes. In many species, both eyes lie on one side of the ...

, wrasse

The wrasses are a family, Labridae, of marine fish, many of which are brightly colored. The family is large and diverse, with over 600 species in 81 genera, which are divided into 9 subgroups or tribes.

They are typically small, most of them le ...

, perches

Perch is a common name for fish of the genus ''Perca'', freshwater gamefish belonging to the family Percidae. The perch, of which three species occur in different geographical areas, lend their name to a large order of vertebrates: the Percif ...

, anglerfish

The anglerfish are fish of the teleost order Lophiiformes (). They are bony fish named for their characteristic mode of predation, in which a modified luminescent fin ray (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure for other fish. The luminescence ...

, and pufferfish. The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

below, which is based on Betancur-R ''et al.'', 2017, shows the relationships between extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

percomorphs. Teleosts, and percomorphs in particular, thrived during the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configura ...

era

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Comp ...

. Fossil evidence shows that there was a major increase in size and abundance of teleosts immediately after the mass extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. It ...

at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary ca. 66 mya.

Evolutionary trends

The first fossils assignable to this diverse group appear in theEarly Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which is a un ...

, after which teleosts accumulated novel body shapes predominantly gradually for the first 150 million years of their evolution (Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which is a un ...

through early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pro ...

).

The most basal of the living teleosts are the Elopomorpha

The superorder Elopomorpha contains a variety of types of fishes that range from typical silvery-colored species, such as the tarpons and ladyfishes of the Elopiformes and the bonefishes of the Albuliformes, to the long and slender, smooth-bodi ...

(eels and allies) and the Osteoglossomorpha

Osteoglossomorpha is a group of bony fish in the Teleostei.

Notable members

A notable member is the arapaima (''Arapaima gigas''), the largest freshwater fish in South America and one of the largest bony fishes alive. Other notable members incl ...

(elephantfishes and allies). There are 800 species of elopomorphs. They have thin leaf-shaped larvae known as leptocephali

Leptocephalus (meaning "slim head") is the flat and transparent larva of the eel, marine eels, and other members of the superorder Elopomorpha. This is one of the most diverse groups of teleosts, containing 801 species in 4 orders, 24 famili ...

, specialised for a marine environment. Among the elopomorphs, eels have elongated bodies with lost pelvic girdles and ribs and fused elements in the upper jaw. The 200 species of osteoglossomorphs are defined by a bony element in the tongue. This element has a basibranchial behind it, and both structures have large teeth which are paired with the teeth on the parasphenoid in the roof of the mouth. The clade Otocephala

Otocephala is a clade of ray-finned fishes within the infraclass Teleostei that evolved some 230 million years ago. It is named for the presence of a hearing (otophysic) link from the swimbladder to the inner ear. Other names proposed for the gro ...

includes the Clupeiformes

Clupeiformes is the order of Actinopterygii, ray-finned fish that includes the herring family, Clupeidae, and the anchovy family, Engraulidae. The group includes many of the most important Forage fish, forage and food fish.

Clupeiformes are phy ...

(herrings) and Ostariophysi

Ostariophysi is the second-largest superorder of fish. Members of this superorder are called ostariophysians. This diverse group contains 10,758 species, about 28% of known fish species in the world and 68% of freshwater species, and are present ...

(carps, catfishes and allies). Clupeiformes consists of 350 living species of herring and herring-like fishes. This group is characterised by an unusual abdominal scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

and a different arrangement of the hypurals. In most species, the swim bladder extends to the braincase and plays a role in hearing. Ostariophysi, which includes most freshwater fishes, includes species that have developed some unique adaptations. One is the Weberian apparatus

The Weberian apparatus is an anatomical structure that connects the swim bladder to the auditory system in fishes belonging to the superorder Ostariophysi. When it is fully developed in adult fish, the elements of the apparatus are sometimes col ...

, an arrangement of bones (Weberian ossicles) connecting the swim bladder to the inner ear. This enhances their hearing, as sound waves make the bladder vibrate, and the bones transport the vibrations to the inner ear. They also have a chemical alarm system; when a fish is injured, the warning substance gets in the water, alarming nearby fish.Helfman, Collette, Facey and Bowen pp. 268–274

The majority of teleost species belong to the clade Euteleostei

Euteleostei, whose members are known as euteleosts, is a clade of bony fishes within Teleostei that evolved some 240 million years ago. It is divided into Protacanthopterygii (including the salmon and dragonfish) and Neoteleostei (including t ...

, which consists of 17,419 species classified in 2,935 genera and 346 families. Shared traits of the euteleosts include similarities in the embryonic development of the bony or cartilaginous structures located between the head and dorsal fin (supraneural bones), an outgrowth on the stegural bone (a bone located near the neural arches of the tail), and caudal median cartilages located between hypurals of the caudal base. The majority of euteleosts are in the clade Neoteleostei

The Neoteleostei is a large clade of bony fish that includes the Ateleopodidae (jellynoses), Aulopiformes (lizardfish), Myctophiformes (lanternfish), Polymixiiformes (beardfish), Percopsiformes (Troutperches), Gadiformes (cods), Zeiformes (dorie ...

. A derived trait of neoteleosts is a muscle that controls the pharyngeal jaws, giving them a role in grinding food. Within neoteleosts, members of the Acanthopterygii

Acanthopterygii (meaning "spiny finned one") is a superorder of bony fishes in the class Actinopterygii. Members of this superorder are sometimes called ray-finned fishes for the characteristic sharp, bony rays in their fins; however this name i ...

have a spiny dorsal fin which is in front of the soft-rayed dorsal fin. This fin helps provide thrust in locomotion and may also play a role in defense. Acanthomorphs have developed spiny ctenoid scales (as opposed to the cycloid scales of other groups), tooth-bearing premaxilla and greater adaptations to high speed swimming.

The adipose fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as s ...

, which is present in over 6,000 teleost species, is often thought to have evolved once in the lineage and to have been lost multiple times due to its limited function. A 2014 study challenges this idea and suggests that the adipose fin is an example of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

. In Characiformes

Characiformes is an order of ray-finned fish, comprising the characins and their allies. Grouped in 18 recognized families, more than 2000 different species are described, including the well-known piranha and tetras.; Buckup P.A.: "Relationshi ...

, the adipose fin develops from an outgrowth after the reduction of the larval fin fold, while in Salmoniformes

Salmonidae is a family of ray-finned fish that constitutes the only currently extant family in the order Salmoniformes . It includes salmon (both Atlantic and Pacific species), trout (both ocean-going and landlocked), chars, freshwater whitefis ...

, the fin appears to be a remnant of the fold.

Diversity

There are over 26,000 species of teleosts, in about 40

There are over 26,000 species of teleosts, in about 40 orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

and 448 families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

, making up 96% of all extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

species of fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

. Approximately 12,000 of the total 26,000 species are found in freshwater habitats. Teleosts are found in almost every aquatic environment and have developed specializations to feed in a variety of ways as carnivores, herbivores, filter feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

s and parasites

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted structurally to this way of lif ...

. The longest teleost is the giant oarfish

The giant oarfish (''Regalecus glesne'') is a species of oarfish of the family Regalecidae. It is an oceanodromous species with a worldwide distribution, excluding polar regions. Other common names include Pacific oarfish, king of herrings, ribb ...

, reported at and more, but this is dwarfed by the extinct ''Leedsichthys

''Leedsichthys'' is an extinct genus of pachycormid fish that lived in the oceans of the Middle to Late Jurassic.Liston, JJ (2004). An overview of the pachycormiform ''Leedsichthys''. In: Arratia G and Tintori A (eds) Mesozoic Fishes 3 - System ...

'', one individual of which has been estimated to have a length of . The heaviest teleost is believed to be the ocean sunfish

The ocean sunfish or common mola (''Mola mola'') is one of the largest bony fish in the world. It was misidentified as the heaviest bony fish, which was actually a different species, ''Mola alexandrini''. Adults typically weigh between . The spe ...

, with a specimen landed in 2003 having an estimated weight of , while the smallest fully mature adult is the male anglerfish ''Photocorynus spiniceps

''Photocorynus spiniceps'' is a species of anglerfish in the family Linophrynidae. It is in the monotypic genus ''Photocorynus''.

The known mature male individuals are 6.2–7.3 millimeters (0.25-0.3 inches), smaller than any other m ...

'' which can measure just , though the female at is much larger. The stout infantfish is the smallest and lightest adult fish and is in fact the smallest vertebrate in the world; the females measures and the male just .

Open water fish are usually streamlined like

Open water fish are usually streamlined like torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

es to minimize turbulence as they move through the water. Reef fish live in a complex, relatively confined underwater landscape and for them, manoeuvrability is more important than speed, and many of them have developed bodies which optimize their ability to dart and change direction. Many have laterally compressed bodies (flattened from side to side) allowing them to fit into fissures and swim through narrow gaps; some use their pectoral fins

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

for locomotion and others undulate their dorsal and anal fins. Some fish have grown dermal (skin) appendages for camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the ...

; the prickly leather-jacket is almost invisible among the seaweed it resembles and the tasselled scorpionfish invisibly lurks on the seabed ready to ambush prey. Some like the foureye butterflyfish

The foureye butterflyfish (''Chaetodon capistratus'') is a butterflyfish (family Chaetodontidae). It is alternatively called the four-eyed butterflyfish. This species is found in the Western Atlantic from Massachusetts, USA and Bermuda to the Wes ...

have eyespots to startle or deceive, while others such as lionfish

''Pterois'' is a genus of venomous marine fish, commonly known as lionfish, native to the Indo-Pacific. Also called firefish, turkeyfish, tastyfish, or butterfly-cod, it is characterized by conspicuous warning coloration with red, white, crea ...

have aposematic coloration

Aposematism is the advertising by an animal to potential predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defences which make the prey difficult to kill and eat, such as toxicity, venom, foul taste o ...

to warn that they are toxic or have venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

ous spines.

Flatfish are demersal fish

Demersal fish, also known as groundfish, live and feed on or near the bottom of seas or lakes (the demersal zone).Walrond Carl . "Coastal fish - Fish of the open sea floor"Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009 They occ ...

(bottom-feeding fish) that show a greater degree of asymmetry than any other vertebrates. The larvae are at first bilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

but they undergo metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some inse ...

during the course of their development, with one eye migrating to the other side of the head, and they simultaneously start swimming on their side. This has the advantage that, when they lie on the seabed, both eyes are on top, giving them a broad field of view. The upper side is usually speckled and mottled for camouflage, while the underside is pale.

Some teleosts are parasites.

Some teleosts are parasites. Remora

The remora (), sometimes called suckerfish, is any of a family (Echeneidae) of ray-finned fish in the order Carangiformes. Depending on species, they grow to long. Their distinctive first dorsal fins take the form of a modified oval, sucker-li ...

s have their front dorsal fins modified into large suckers with which they cling onto a host animal such as a whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

, sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerhead, ...

, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

or ray, but this is probably a commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit fro ...

rather than parasitic arrangement because both remora and host benefit from the removal of ectoparasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

and loose flakes of skin. More harmful are the catfish

Catfish (or catfishes; order Siluriformes or Nematognathi) are a diverse group of ray-finned fish. Named for their prominent barbels, which resemble a cat's whiskers, catfish range in size and behavior from the three largest species alive, ...

that enter the gill chambers of fish and feed on their blood and tissues. The snubnosed eel, though usually a scavenger

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding b ...

, sometimes bores into the flesh of a fish, and has been found inside the heart of a shortfin mako shark

The shortfin mako shark (; ; ''Isurus oxyrinchus''), also known as the blue pointer or bonito shark, is a large mackerel shark. It is commonly referred to as the mako shark, as is the longfin mako shark (''Isurus paucus''). The shortfin mako can ...

.

electric eel

The electric eels are a genus, ''Electrophorus'', of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae. They are known for their ability to stun their prey by generating electricity, delivering shocks at up to 860 volts ...

s, can produce powerful electric currents, strong enough to stun prey. Other fish, such as knifefish, generate and sense weak electric fields to detect their prey; they swim with straight backs to avoid distorting their electric fields. These currents are produced by modified muscle or nerve cells.

Distribution

Teleosts are found worldwide and in most aquatic environments, including warm and cold seas, flowing and stillfreshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

, and even, in the case of the desert pupfish

The desert pupfish (''Cyprinodon macularius'') is a rare species of bony fish in the family Cyprinodontidae. It is a small fish, typically less than 7.62 cm (3 in) in length. Males are generally larger than females, and have bright-blue ...

, isolated and sometimes hot and saline bodies of water in deserts. Teleost diversity becomes low at extremely high latitudes; at Franz Josef Land

, native_name =

, image_name = Map of Franz Josef Land-en.svg

, image_caption = Map of Franz Josef Land

, image_size =

, map_image = Franz Josef Land location-en.svg

, map_caption = Location of Franz Josef ...

, up to 82°N, ice cover and water temperatures below for a large part of the year limit the number of species; 75 percent of the species found there are endemic to the Arctic.

Of the major groups of teleosts, the Elopomorpha, Clupeomorpha and Percomorpha (perches, tunas and many others) all have a worldwide distribution and are mainly marine; the Ostariophysi and Osteoglossomorpha are worldwide but mainly freshwater, the latter mainly in the tropics; the Atherinomorpha (guppies, etc.) have a worldwide distribution, both fresh and salt, but are surface-dwellers. In contrast, the Esociformes (pikes) are limited to freshwater in the Northern Hemisphere, while the Salmoniformes (

Of the major groups of teleosts, the Elopomorpha, Clupeomorpha and Percomorpha (perches, tunas and many others) all have a worldwide distribution and are mainly marine; the Ostariophysi and Osteoglossomorpha are worldwide but mainly freshwater, the latter mainly in the tropics; the Atherinomorpha (guppies, etc.) have a worldwide distribution, both fresh and salt, but are surface-dwellers. In contrast, the Esociformes (pikes) are limited to freshwater in the Northern Hemisphere, while the Salmoniformes (salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family (biology), family Salmonidae, which are native to tributary, tributaries of the ...

, trout) are found in both Northern and Southern temperate zones in freshwater, some species migrating to and from the sea. The Paracanthopterygii (cods, etc.) are Northern Hemisphere fish, with both salt and freshwater species.

Some teleosts are migratory; certain freshwater species move within river systems on an annual basis; other species are anadromous, spending their lives at sea and moving inland to spawn

Spawn or spawning may refer to:

* Spawn (biology), the eggs and sperm of aquatic animals

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Spawn (character), a fictional character in the comic series of the same name and in the associated franchise

** '' Spawn: ...

, salmon and striped bass

The striped bass (''Morone saxatilis''), also called the Atlantic striped bass, striper, linesider, rock, or rockfish, is an anadromous perciform fish of the family Moronidae found primarily along the Atlantic coast of North America. It has al ...

being examples. Others, exemplified by the eel

Eels are ray-finned fish belonging to the order Anguilliformes (), which consists of eight suborders, 19 families, 111 genera, and about 800 species. Eels undergo considerable development from the early larval stage to the eventual adult stage ...

, are catadromous

Fish migration is mass relocation by fish from one area or body of water to another. Many types of fish migrate on a regular basis, on time scales ranging from daily to annually or longer, and over distances ranging from a few metres to thousan ...

, doing the reverse. The fresh water European eel

The European eel (''Anguilla anguilla'') is a species of eel, a snake-like, catadromous fish. They are normally around and rarely reach more than , but can reach a length of up to in exceptional cases.

Eels have been important sources of fo ...

migrates across the Atlantic Ocean as an adult to breed in floating seaweed in the Sargasso Sea

The Sargasso Sea () is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre. Unlike all other regions called seas, it has no land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Ocean by its charac ...

. The adults spawn here and then die, but the developing young are swept by the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Current, North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida a ...

towards Europe. By the time they arrive, they are small fish and enter estuaries and ascend rivers, overcoming obstacles in their path to reach the streams and ponds where they spend their adult lives.

Teleosts including the brown trout

The brown trout (''Salmo trutta'') is a European species of salmonid fish that has been widely introduced into suitable environments globally. It includes purely freshwater populations, referred to as the riverine ecotype, ''Salmo trutta'' morph ...

and the scaly osman

The scaly osman (''Diptychus maculatus'') is a species of cyprinid freshwater fish. It is native to Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau of China, India, Nepal and Pakistan, ranging west to the Tien Shan Mountains and Central Asia

Central Asi ...

are found in mountain lakes in Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

at altitudes as high as . Teleosts are found at extreme depths in the oceans; the hadal snailfish has been seen at a depth of , and a related (unnamed) species has been seen at .

Physiology

Respiration

The major means of respiration in teleosts, as in most other fish, is the transfer of gases over the surface of the gills as water is drawn in through the mouth and pumped out through the gills. Apart from the

The major means of respiration in teleosts, as in most other fish, is the transfer of gases over the surface of the gills as water is drawn in through the mouth and pumped out through the gills. Apart from the swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled Organ (anatomy), organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their curren ...

, which contains a small amount of air, the body does not have oxygen reserves, and respiration needs to be continuous over the fish's life. Some teleosts exploit habitats where the oxygen availability is low, such as stagnant water or wet mud; they have developed accessory tissues and organs to support gas exchange in these habitats.

Several genera of teleosts have independently developed air-breathing capabilities, and some have become amphibious. Some combtooth blennies emerge to feed on land, and freshwater eels are able to absorb oxygen through damp skin. Mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestrial locomotion and ...

s can remain out of water for considerable periods, exchanging gases through skin and mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

s in the mouth and pharynx. Swamp eel

The swamp eels (also written "swamp-eels") are a family (Synbranchidae) of freshwater eel-like fishes of the tropics and subtropics. Most species are able to breathe air and typically live in marshes, ponds and damp places, sometimes burying the ...

s have similar well-vascularised mouth-linings, and can remain out of water for days and go into a resting state (aestivation

Aestivation ( la, aestas (summer); also spelled estivation in American English) is a state of animal dormancy, similar to hibernation, although taking place in the summer rather than the winter. Aestivation is characterized by inactivity and ...

) in mud. The anabantoids have developed an accessory breathing structure known as the labyrinth organ

The Anabantoidei are a suborder of anabantiform ray-finned freshwater fish distinguished by their possession of a lung-like labyrinth organ, which enables them to breathe air. The fish in the Anabantoidei suborder are known as anabantoids or lab ...

on the first gill arch and this is used for respiration in air, and airbreathing catfish

Airbreathing catfish comprise the family Clariidae of the order Siluriformes. Sixteen genera and about 116 species of clariid fishes are described; all are freshwater species. Other groups of catfish also breathe air, such as the Callichthyidae ...

have a similar suprabranchial organ. Certain other catfish, such as the Loricariidae

The Loricariidae is the largest family of catfish (order Siluriformes), with 92 genera and just over 680 species. Loricariids originate from freshwater habitats of Costa Rica, Panama, and tropical and subtropical South America. These fish are not ...

, are able to respire through air held in their digestive tracts.

Sensory systems

Teleosts possess highly developed sensory organs. Nearly all daylight fish have colour vision at least as good as a normal human's. Many fish also have

Teleosts possess highly developed sensory organs. Nearly all daylight fish have colour vision at least as good as a normal human's. Many fish also have chemoreceptor

A chemoreceptor, also known as chemosensor, is a specialized sensory receptor which transduces a chemical substance (endogenous or induced) to generate a biological signal. This signal may be in the form of an action potential, if the chemorecept ...

s responsible for acute senses of taste and smell. Most fish have sensitive receptors that form the lateral line system

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

, which detects gentle currents and vibrations, and senses the motion of nearby fish and prey. Fish sense sounds in a variety of ways, using the lateral line, the swim bladder, and in some species the Weberian apparatus. Fish orient themselves using landmarks, and may use mental maps based on multiple landmarks or symbols. Experiments with mazes show that fish possess the spatial memory

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, spatial memory is a form of memory responsible for the recording and recovery of information needed to plan a course to a location and to recall the location of an object or the occurrence of an event. Sp ...

needed to make such a mental map.

Osmoregulation

The skin of a teleost is largely impermeable to water, and the main interface between the fish's body and its surroundings is the gills. In freshwater, teleost fish gain water across their gills by

The skin of a teleost is largely impermeable to water, and the main interface between the fish's body and its surroundings is the gills. In freshwater, teleost fish gain water across their gills by osmosis

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region of ...

, while in seawater they lose it. Similarly, salts diffuse

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

outwards across the gills in freshwater and inwards in salt water. The European flounder

The European flounder (''Platichthys flesus'') is a flatfish of European coastal waters from the White Sea in the north to the Mediterranean and the Black Sea in the south. It has been introduced into the United States and Canada accidentally th ...

spends most of its life in the sea but often migrates into estuaries and rivers. In the sea in one hour, it can gain Na+ ions equivalent to forty percent of its total free sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable iso ...

content, with 75 percent of this entering through the gills and the remainder through drinking. By contrast, in rivers there is an exchange of just two percent of the body Na+ content per hour. As well as being able to selectively limit salt and water exchanged by diffusion, there is an active mechanism across the gills for the elimination of salt in sea water and its uptake in fresh water.

Thermoregulation

Fish are cold-blooded, and in general their body temperature is the same as that of their surroundings. They gain and lose heat through their skin, and regulate their circulation in response to changes in water temperature by increasing or reducing the blood flow to the gills. Metabolic heat generated in the muscles or gut is quickly dissipated through the gills, with blood being diverted away from the gills during exposure to cold. Because of their relative inability to control their blood temperature, most teleosts can only survive in a small range of water temperatures. Teleost species that inhabit colder waters have a higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in brain cell membranes compared to fish from warmer waters, which allows them to maintain appropriatemembrane fluidity

In biology, membrane fluidity refers to the viscosity of the lipid bilayer of a cell membrane or a synthetic lipid membrane. Lipid packing can influence the fluidity of the membrane. Viscosity of the membrane can affect the rotation and diffusion ...

in the environments in which they live. When cold acclimated, teleost fish show physiological changes in skeletal muscle that include increased mitochondrial and capillary density. This reduces diffusion distances and aids in the production of aerobic ATP, which helps to compensate for the drop in metabolic rate

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

associated with colder temperatures.

Tuna

A tuna is a saltwater fish that belongs to the tribe Thunnini, a subgrouping of the Scombridae (mackerel) family. The Thunnini comprise 15 species across five genera, the sizes of which vary greatly, ranging from the bullet tuna (max length: ...

and other fast-swimming ocean-going fish maintain their muscles at higher temperatures than their environment for efficient locomotion. Tuna achieve muscle temperatures or even higher above the surroundings by having a counterflow system in which the metabolic heat produced by the muscles and present in the venous blood, pre-warms the arterial blood before it reaches the muscles. Other adaptations of tuna for speed include a streamlined, spindle-shaped body, fins designed to reduce drag, and muscles with a raised myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compared to hemoglobin, myoglobi ...

content, which gives these a reddish colour and makes for a more efficient use of oxygen. In polar regions

The polar regions, also called the frigid zones or polar zones, of Earth are the regions of the planet that surround its geographical poles (the North and South Poles), lying within the polar circles. These high latitudes are dominated by float ...

and in the deep ocean

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of 200 metres (656 feet) or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combin ...

, where the temperature is a few degrees above freezing point, some large fish, such as the swordfish

Swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as broadbills in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are a popular sport fish of the billfish category, though elusive. Swordfis ...

, marlin

Marlins are fish from the family Istiophoridae, which includes about 10 species. A marlin has an elongated body, a spear-like snout or bill, and a long, rigid dorsal fin which extends forward to form a crest. Its common name is thought to deri ...

and tuna, have a heating mechanism which raises the temperature of the brain and eye, allowing them significantly better vision than their cold-blooded prey.

Buoyancy

The body of a teleost is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference, or they will sink. Many teleosts have a swim bladder that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases to allow them to stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. In the more primitive groups like some

The body of a teleost is denser than water, so fish must compensate for the difference, or they will sink. Many teleosts have a swim bladder that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases to allow them to stay at the current water depth, or ascend or descend without having to waste energy in swimming. In the more primitive groups like some minnows

Minnow is the common name for a number of species of small freshwater fish, belonging to several genera of the families Cyprinidae and Leuciscidae. They are also known in Ireland as pinkeens.

Smaller fish in the subfamily Leusciscidae are co ...

, the swim bladder is open to the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

and doubles as a lung

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of t ...

. It is often absent in fast-swimming fishes such as the tuna and mackerel

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

...

. In fish where the swim bladder is closed, the gas content is controlled through the rete mirabilis, a network of blood vessels serving as a countercurrent gas exchanger between the swim bladder and the blood. The Chondrostei such as sturgeons also have a swim bladder, but this appears to have evolved separately: other Actinopterygii such as the bowfin and the bichir do not have one, so swim bladders appear to have arisen twice, and the teleost swim bladder is not homologous with the chondrostean one.

Locomotion

A typical teleost fish has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, and locomotion is generally provided by a lateral undulation of the hindmost part of the trunk and the tail, propelling the fish through the water. There are many exceptions to this method of locomotion, especially where speed is not the main objective; among rocks and on

A typical teleost fish has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, and locomotion is generally provided by a lateral undulation of the hindmost part of the trunk and the tail, propelling the fish through the water. There are many exceptions to this method of locomotion, especially where speed is not the main objective; among rocks and on coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

s, slow swimming with great manoeuvrability may be a desirable attribute. Eels locomote by wiggling their entire bodies. Living among seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the orde ...

es and algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

, the seahorse

A seahorse (also written ''sea-horse'' and ''sea horse'') is any of 46 species of small marine fish in the genus ''Hippocampus''. "Hippocampus" comes from the Ancient Greek (), itself from () meaning "horse" and () meaning "sea monster" or " ...

adopts an upright posture and moves by fluttering its pectoral fins, and the closely related pipefish

Pipefishes or pipe-fishes (Syngnathinae) are a subfamily of small fishes, which, together with the seahorses and seadragons (''Phycodurus'' and ''Phyllopteryx''), form the family Syngnathidae.

Description

Pipefish look like straight-bodied seah ...

moves by rippling its elongated dorsal fin. Gobies

Gobiidae or gobies is a family of bony fish in the order Gobiiformes, one of the largest fish families comprising more than 2,000 species in more than 200 genera. Most of gobiid fish are relatively small, typically less than in length, and the ...

"hop" along the substrate, propping themselves up and propelling themselves with their pectoral fins. Mudskippers move in much the same way on terrestrial ground. In some species, a pelvic sucker allows them to climb, and the Hawaiian freshwater goby climbs waterfalls while migrating. Gurnards have three pairs of free rays on their pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as ...

s which have a sensory function but on which they can walk along the substrate. Flying fish

The Exocoetidae are a family of marine fish in the order Beloniformes class Actinopterygii, known colloquially as flying fish or flying cod. About 64 species are grouped in seven to nine genera. While they cannot fly in the same way a bird do ...

launch themselves into the air and can glide

Glide may refer to:

* Gliding flight, to fly without thrust

Computing

*Glide API, a 3D graphics interface

*Glide OS, a web desktop

*Glide (software), an instant video messenger

*Glide, a molecular docking software by Schrödinger (company), Schr� ...

on their enlarged pectoral fins for hundreds of metres.

Sound production

To attract mates, some teleosts produce sounds, either bystridulation

Stridulation is the act of producing sound by rubbing together certain body parts. This behavior is mostly associated with insects, but other animals are known to do this as well, such as a number of species of fish, snakes and spiders. The mech ...

or by vibrating the swim bladder. In the Sciaenidae

Sciaenidae are a family of fish in the order Acanthuriformes. They are commonly called drums or croakers in reference to the repetitive throbbing or drumming sounds they make. The family consists of about 286 to 298 species in about 66 to 70 gen ...

, the muscles that attach to the swim bladder cause it to oscillate rapidly, creating drumming sounds. Marine catfishes, sea horses and grunts stridulate by rubbing together skeletal parts, teeth or spines. In these fish, the swim bladder may act as a resonator