de Havilland DH.88 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The de Havilland DH.88 Comet is a British two-seat, twin-engined aircraft built by the de Havilland Aircraft Company. It was developed specifically to participate in the 1934 England-Australia

The resulting design had a low, tapered high aspect ratio wing and was powered by two Gipsy Six R engines, a specially-tuned version of the new

The resulting design had a low, tapered high aspect ratio wing and was powered by two Gipsy Six R engines, a specially-tuned version of the new  The fuselage was built principally from plywood over spruce

The fuselage was built principally from plywood over spruce

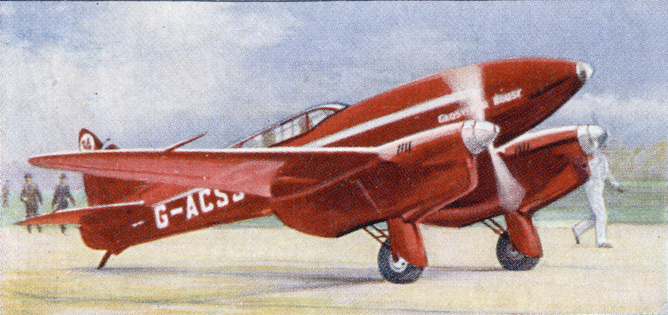

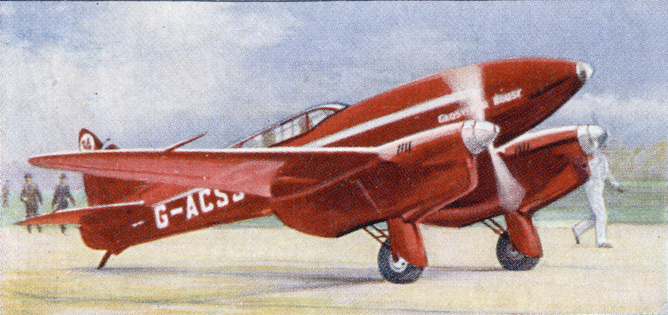

Arthur Edwards named his red Comet G-ACSS after the Grosvenor House Hotel of which he was managing director. He engaged

Arthur Edwards named his red Comet G-ACSS after the Grosvenor House Hotel of which he was managing director. He engaged

''Grosvenor House'' was dismantled and shipped back to England. It was later bought by the Air Ministry, given the military serial K5084, painted silver overall with RAF markings and flown to

''Grosvenor House'' was dismantled and shipped back to England. It was later bought by the Air Ministry, given the military serial K5084, painted silver overall with RAF markings and flown to

G-ACSS was requisitioned for the RAF once again in 1943 but soon passed on to de Havilland. Restored for static display as ''Grosvenor House'', it was put on show for the 1951

G-ACSS was requisitioned for the RAF once again in 1943 but soon passed on to de Havilland. Restored for static display as ''Grosvenor House'', it was put on show for the 1951  CS-AAJ ''Salazar'' was rediscovered in Portugal after being lost for more than 40 years. It was brought back to the UK and re-registered once again as G-ACSP. As of 2020 restoration continues, with a view to it flying again in its original livery as ''Black Magic'', by the Comet Racer Project Group at the Amy Johnson Comet Restoration Centre,

CS-AAJ ''Salazar'' was rediscovered in Portugal after being lost for more than 40 years. It was brought back to the UK and re-registered once again as G-ACSP. As of 2020 restoration continues, with a view to it flying again in its original livery as ''Black Magic'', by the Comet Racer Project Group at the Amy Johnson Comet Restoration Centre,

"Restoration: Black Magic."

''Light Aviation Association'', November 2011. pp. 16–19.

The MacRobertson Air Race was an event of world-wide importance and did much to drive aeroplane design forward. The triumph of the Comet and its high-speed design marked a milestone in aviation.

The Comet Hotel, Hatfield was begun the year before the race, as one of the first modernist inns in England. Located close to the de Havilland factory, when it was finished it was named after the Comet Racer. War artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a carved column in its car park, which was erected in 1936. On its top is mounted a famous model of the Comet, currently in the livery of ''Grosvenor House''.

Full-scale but non-flying replicas of ''Grosvenor House'' and ''Black Magic'' were constructed for the 1990 TV two-part Australian-produced dramatisation ''Half a World Away'', which was also released on DVD as '' The Great Air Race''. The G-ACSS replica was taxi-able and has since been partially restored in the livery of G-ACSR and is on static display at the De Havilland Aircraft Museum,

The MacRobertson Air Race was an event of world-wide importance and did much to drive aeroplane design forward. The triumph of the Comet and its high-speed design marked a milestone in aviation.

The Comet Hotel, Hatfield was begun the year before the race, as one of the first modernist inns in England. Located close to the de Havilland factory, when it was finished it was named after the Comet Racer. War artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a carved column in its car park, which was erected in 1936. On its top is mounted a famous model of the Comet, currently in the livery of ''Grosvenor House''.

Full-scale but non-flying replicas of ''Grosvenor House'' and ''Black Magic'' were constructed for the 1990 TV two-part Australian-produced dramatisation ''Half a World Away'', which was also released on DVD as '' The Great Air Race''. The G-ACSS replica was taxi-able and has since been partially restored in the livery of G-ACSR and is on static display at the De Havilland Aircraft Museum, De Havilland DH88 Comet Racer

, De Havilland Aircraft Museum. (Retrieved 15 July 2019). Comets have also appeared in fiction, see Aircraft in fiction#de Havilland DH.88 Comet.

"For the England Australia Air Race: The de Havilland 'Comet'

'' Flight'', Volume 26, No. 1343, 20 September 1934, pp. 968–972. * Jackson, A. J. ''De Havilland Aircraft Since 1909''. London: Putnam, Third edition, 1987. . * Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record Breaking Aircraft''. London: Putnam, 1970. . * * Ogilvy, David. ''DH88: deHavilland's Racing Comets''. Shrewsbury, Airlife, 1988. . * Ramsden, J. M. "The Comet's Tale – Part 2". '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 16, No. 5. May 1988. pp. 279–283. ISSN 0143-7240. * Ricco, Philippe. "La Comète en France, Part 1", '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 35, No. 439. November 2009. * Ricco, Philippe. "La Comète en France, Part 2: The Burden of Proof". '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 38, No. 449. September 2010. * Sharp, C. Martin; ''DH: An Outline of de Havilland History''. London, Faber & Faber, 1960. * Taylor, H. A. "The First "Wooden Wonder"". '' Air Enthusiast'', No. 10, July–September 1979. pp. 51–57.

"The Story of the Australia Race"

'' Flight'', Volume 26, No. 1348, 25 October 1934, pp. 1110–1117.

Sound recording of G-ACSS

Aircraft Sound Recordings.

video of G-ACSS arriving in Australia

{{de Havilland aircraft Racing aircraft 1930s British mailplanes 1930s British sport aircraft DH.088 Low-wing aircraft Aircraft first flown in 1934 Twin piston-engined tractor aircraft

MacRobertson Air Race

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place in October 1934 as part of the Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The race was devised by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir Harold Gengoult Smith, and th ...

from the United Kingdom to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

.

Development of the Comet was seen as both a prestige project and an entry into the use of modern techniques. It was designed around the specific requirements of the race. Despite being made of wood, it was the first British aircraft to incorporate in one airframe all the elements of the modern high speed aircraft - stressed-skin construction, cantilever monoplane flying surfaces, retractable undercarriage, landing flaps, variable-pitch propellers and an enclosed cockpit.

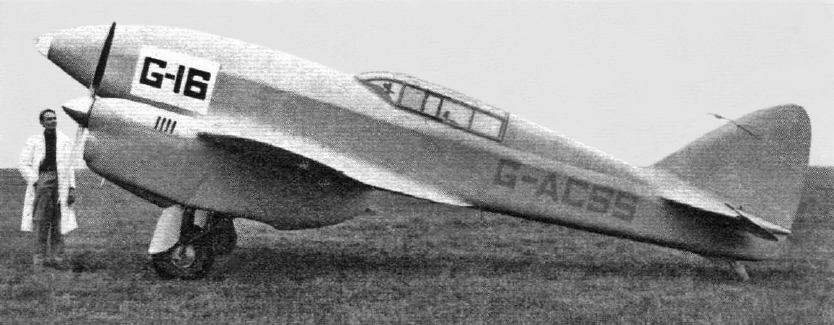

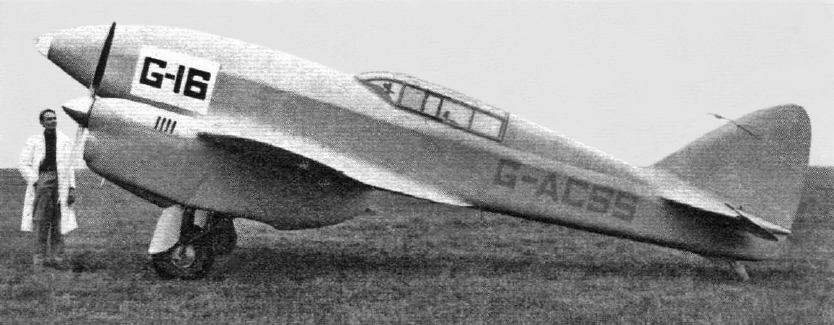

Three Comets were produced for the race, all for private owners at the discounted price of £5,000 per aircraft. The aircraft underwent a rapid development cycle, performing its maiden flight only six weeks prior to the race. Comet G-ACSS ''Grosvenor House'' emerged as the winner. Another two Comets were built after the race. The Comet established many aviation records, both during the race and in its aftermath, as well as participating in further races. Several examples were bought and evaluated by national governments, typically as mail planes. Two Comets, ''G-ACSS'' and ''G-ACSP'', survived into preservation, while a number of full-scale replicas have also been constructed.

Development

Background: The Great Air Race

During 1933, theMacRobertson Air Race

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place in October 1934 as part of the Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The race was devised by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne, Sir Harold Gengoult Smith, and th ...

, a long distance multi-stage journey from the United Kingdom to Australia, was being planned for October 1934, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Australian State of Victoria. Sponsored by Macpherson Robertson, an Australian confectionery manufacturer, the race would be flown in stages from England to Melbourne.Lewis 1970, p. 257.

Despite a number of previous air racing successes by British companies, a new generation of monoplane airliners that were then being developed in America had no viable rival in Britain at the time. Geoffrey de Havilland, a British aviation pioneer and founder of aircraft manufacturing firm de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

, was determined that, for the sake of national prestige, Britain should put up a serious competitor.Ogilvy 1988, p. 16. While the company board recognised that there would be no prospect of recouping the full investment in producing such a machine, they believed that the project would also enhance the company's prestige and, perhaps more importantly, provide much-needed experience in the development of modern fast monoplanes.

Accordingly, they announced in January 1934 that if three orders could be obtained by 28 February, a specialist racer to be named the ''Comet'' would be built and sold for £5,000 each, that would be capable of achieving a guaranteed speed of .''Flight'', 18 Jan 1934, p. 59. ''"...that a limited number of these machines will be built, and that the price will be £5,000. A deposit of 20 per cent. will be demanded with the order, and the company will guarantee a top speed of at least 200 m.p.h. If that speed is not attained, the customer will be at liberty to cancel his order, and all money paid by him will be refunded. In order to ensure ample time for development and tests, it is pointed out that instructions to begin construction should be placed before the end of February."'' This price was estimated as being half of the cost of manufacture. Three orders were indeed received by the deadline; one from Jim Mollison, to be flown by him and his wife Amy (better known as Amy Johnson), one from Arthur Edwards, a hotel owner and manager, and the last from racing motorist Bernard Rubin.Ogilvy 1988.

Design phase

Although designed around the requirements for the MacRobertson race, owing to its unusual requirements the Comet did not fit the standard technical specification for aracing aircraft

Air racing is a type of motorsport that involves airplanes or other types of aircraft that compete over a fixed course, with the winner either returning the shortest time, the one to complete it with the most points, or to come closest to a previ ...

, nevertheless it was classed as a "Special, sub-division (f), Racing or Record". De Havilland paid special attention to the non-stop range necessary for the long official stages. They initially intended to produce a twin-engined two-seat development of the DH.71 experimental monoplane. However it would have insufficient performance so the designer, A. E. Hagg, turned to a more innovative design. He chose a modern cantilever monoplane with enclosed cockpit, retractable undercarriage

Undercarriage is the part of a moving vehicle that is underneath the main body of the vehicle. The term originally applied to this part of a horse-drawn carriage, and usage has since broadened to include:

*The landing gear of an aircraft.

*The ch ...

and flaps. In order to achieve take-off at a reasonable speed and with high all-up weight, combined with a satisfactory high-speed cruise, it would be necessary to fit variable-pitch propellers.

The resulting design had a low, tapered high aspect ratio wing and was powered by two Gipsy Six R engines, a specially-tuned version of the new

The resulting design had a low, tapered high aspect ratio wing and was powered by two Gipsy Six R engines, a specially-tuned version of the new Gipsy Six

The de Havilland Gipsy Six is a British six-cylinder, air-cooled, inverted inline piston engine developed by the de Havilland Engine Company for aircraft use in the 1930s. It was based on the cylinders of the four-cylinder Gipsy Major and w ...

. The aircraft was composed almost entirely of wood, the limited use of metal being confined to high- stress components, such as the engine bearers and undercarriage

Undercarriage is the part of a moving vehicle that is underneath the main body of the vehicle. The term originally applied to this part of a horse-drawn carriage, and usage has since broadened to include:

*The landing gear of an aircraft.

*The ch ...

, and to complex curved fairings such as the engine cowlings and wing root fairings. The sheet metal parts comprised a lightweight magnesium- aluminium alloy. Manually-actuated split flap

A flap is a high-lift device used to reduce the stalling speed of an aircraft wing at a given weight. Flaps are usually mounted on the wing trailing edges of a fixed-wing aircraft. Flaps are used to reduce the take-off distance and the landing ...

s were fitted beneath the wing's inboard rear sections and lower fuselage, while the Frise ailerons were mass-balanced by lead strips within the aileron's leading edges.NACA 1935, p. 4. Both the rudder and elevators fitted to the conventional tail had horn mass balances. In order to validate the wing design, a half-scale model wing was built and tested to destruction. The exterior skin was treated via a time-consuming and repetitive process of painting and rubbing down to produce a highly smooth surface to reduce air friction and increase overall speed.''Flight'' 20 September 1934, p. 971.

Aerodynamic efficiency was a major design priority and it was therefore decided to use a thin wing of RAF34 section. This was not thick enough to contain spars of sufficient depth to carry the flight loads and so the wing skin would have to carry most of the loads in a "stressed-skin" construction.''Flight'' 20 September 1934, pp. 968, 971. However, the complex curves required for aerodynamic efficiency could not be manufactured using plywood. Hagg, who also had experience as a naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture occupations

Design occupations

Architecture, Occupations ...

, adapted a construction technique previously used for building lifeboats. The majority of the wing was covered using two layers of wide spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

planking laid diagonally across the wing, with the outer layer laid crosswise over the inner. These strips were of variable thickness, according to the loads they carried, reducing over the span of the wing from at the root to towards the tips. It was built as a single assembly around three box-spars located at 21, 40 and 65 percent chord: there was an intermediate spruce stringer between each pair of spars to prevent buckling. The ribs were made of birch ply and spruce. The outboard were skinned with various thicknesses of ply because of the difficulty of machining spruce planking to less than 0.07 in thickness. The leading edge, forward of the front spar, was also ply covered. The centre section was reinforced with two additional layers of 0.07 in spruce. This method of construction had been made possible only by the recent development of high-strength synthetic bonding resins and its success took many in the industry by surprise.

The fuselage was built principally from plywood over spruce

The fuselage was built principally from plywood over spruce longerons

In engineering, a longeron and stringer is the load-bearing component of a framework.

The term is commonly used in connection with aircraft fuselages and automobile chassis. Longerons are used in conjunction with stringers to form structural ...

, while the upper and lower forward section were built up from spruce planking in order to achieve the necessary compound curves. As with the wing, the strength of the structure was dependent upon the skin. Fuel was carried in three fuselage tanks. The two main tanks filled in the nose and centre section in front of the cockpit. A third auxiliary tank, of only 20 gallon capacity, was placed immediately behind it and could be used to adjust the aircraft's trim

Trim or TRIM may refer to:

Cutting

* Cutting or trimming small pieces off something to remove them

** Book trimming, a stage of the publishing process

** Pruning, trimming as a form of pruning often used on trees

Decoration

* Trim (sewing), or ...

. The pilot and navigator were seated in tandem in a cockpit set aft of the wing. While dual flight controls were fitted, only the forward position had a full set of flight instruments. The rear crew member could also see many of the pilot's instruments by craning sideways while seated. The cockpit was set low in order to reduce drag and forward visibility was very poor. The engines were uprated versions of de Havilland's newly developed Gipsy Six

The de Havilland Gipsy Six is a British six-cylinder, air-cooled, inverted inline piston engine developed by the de Havilland Engine Company for aircraft use in the 1930s. It was based on the cylinders of the four-cylinder Gipsy Major and w ...

, race-tuned for optimum performance with a higher compression ratio

The compression ratio is the ratio between the volume of the cylinder and combustion chamber in an internal combustion engine at their maximum and minimum values.

A fundamental specification for such engines, it is measured two ways: the stati ...

and with a reduced frontal area. The DH.88 could maintain altitude up to on one engine. The main undercarriage

Undercarriage is the part of a moving vehicle that is underneath the main body of the vehicle. The term originally applied to this part of a horse-drawn carriage, and usage has since broadened to include:

*The landing gear of an aircraft.

*The ch ...

retracted backwards into the engine nacelles and was operated manually, requiring 14 turns of a large handwheel located on the right hand side of the cockpit.

The challenging production schedule meant that flight tests of the DH.88 began just six weeks prior to the start of the race. Hamilton-Standard

Hamilton Standard was an American aircraft propeller parts supplier. It was formed in 1929 when United Aircraft and Transport Corporation consolidated Hamilton Aero Manufacturing and Standard Steel Propeller into the Hamilton Standard Propeller ...

hydromatic variable-pitch propeller Variable-pitch propeller can refer to:

*Variable-pitch propeller (marine)

*Variable-pitch propeller (aeronautics)

In aeronautics, a variable-pitch propeller is a type of propeller (airscrew) with blades that can be rotated around their long a ...

s were initially fitted. During testing, the propeller blade roots were found to interfere unacceptably with the airflow into the engine. Instead, a French two-position pneumatically actuated Ratier type was substituted. Its blades were manually set to fine pitch before takeoff using a bicycle

A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike or cycle, is a human-powered or motor-powered assisted, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, having two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. A is called a cyclist, or bicyclist.

Bic ...

pump, and in flight they were repositioned automatically to coarse (high-speed) pitch via a pressure sensor. A drawback was that the propellers could not be reset to fine pitch except on the ground. Other changes included the installation of a large landing light fitted in the nose and a revised, higher profile to the cockpit to give the pilot marginally improved visibility.

Operational history

MacRobertson Race

All three Comets lined up for the start of the race at Mildenhall, a newly established airfield inSuffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

shortly to be handed over to the RAF. G-ACSP was painted black and named ''Black Magic'', G-ACSR green and unnamed, G-ACSS red and named ''Grosvenor House''. The three aircraft took their places among 17 other entrants, which ranged from new high-speed Douglas DC-2

The Douglas DC-2 is a 14-passenger, twin-engined airliner that was produced by the American company Douglas Aircraft Company starting in 1934. It competed with the Boeing 247. In 1935, Douglas produced a larger version called the DC-3, which b ...

and Boeing 247 airliners to old Fairey Fox biplanes.Lewis 1970, p. 270.

G-ACSP ''Black Magic''

Jim Mollison and his wife Amy (born Amy Johnson) were both famous aviators in their own right and were the first entrants to take off in their own G-ACSP ''Black Magic''. At 6:30a.m. on 20 October 1934, they began a non-stop leg to the first compulsory staging point at Baghdad, the only crew who managed to fly this first leg non-stop.Taylor 1979, p. 54. Arriving next at Karachi at 4:53a.m they set a new England- India record. They made two attempts to leave Karachi, the first time they returned when their landing gear failed to retract, and the second time they returned after finding they had the wrong map. They finally departed Karachi at 9:05p.m. for Allahabad. After drifting off course, they made an unscheduled stop at Jabalpur to refuel and discover their position. With no aviation fuel available, they had to use motor car fuel provided by a local bus company; apiston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder and is made gas-tig ...

seized and an oil line ruptured. They flew on to Allahabad

Allahabad (), officially known as Prayagraj, also known as Ilahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi (Benares). It is the administrat ...

on one engine but, by now needing completely new engines, were forced to retire.

G-ACSS ''Grosvenor House''

Arthur Edwards named his red Comet G-ACSS after the Grosvenor House Hotel of which he was managing director. He engaged

Arthur Edwards named his red Comet G-ACSS after the Grosvenor House Hotel of which he was managing director. He engaged C. W. A. Scott

Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott, AFC (13 February 1903 – 15 April 1946Dunnell ''Aeroplane'', November 2019, p. 46.) was an English aviator. He won the MacRobertson Air Race, a race from London to Melbourne, in 1934, in a tim ...

and Tom Campbell Black to fly it in the race.Lewis 1970, pp. 269–270.

Having landed at Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, كركوك, ku, کەرکووک, translit=Kerkûk, , tr, Kerkük) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds, ...

to refuel, they arrived at Baghdad after the Mollisons had left but took off again after a half-hour turnaround. Scott and Campbell Black missed out Karachi and flew non-stop to Allahabad where they were told they were the first to arrive, having overtaken the Mollisons. Despite a severe storm over the Bay of Bengal, in which both pilots had to wrestle with the controls together, they reached Singapore safely, eight hours ahead of the DC-2.

They took off for Darwin

Darwin may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charles Darwin (1809–1882), English naturalist and writer, best known as the originator of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection

* Darwin, Northern Territory, a territorial capital city i ...

, losing power in the port engine over the Timor Sea but struggled on to Darwin. Their official time was 70 hours 54 minutes 18 seconds.

G-ACSR

The third Comet, G-ACSR had been painted in British racing green by Bernard Rubin who was a successful motor race driver. He had intended to fly it himself along with Ken Waller but had to pull out at the last minute due to ill health and instead engaged Owen Cathcart Jones to take his place. On reaching Baghdad, they overshot it in the dark, landing by a village when they ran low on fuel. Leaving at first light, they just made it to Baghdad on empty tanks. On taking off again they found that they had a serious oil leak and had to return for repairs. These repairs were carried out by T.J. Holmes RAF (while in Baghdad on RAF secondment. More trouble was encountered on the Darwin leg so they landed atBatavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

, They were the fourth aircraft to reach Melbourne, in a time of 108 h 13 min 30 s. Cathcart Jones and Waller promptly collected film of the Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

n stages of the race and set off the next day to carry it back to Britain. Their return time of 13 days 6 hr 43 min set a new record.Lewis 1970, p. 272.

After the race

The race winner (formerly G-ACSS), as K5084 in RAF livery, 1936 ''Grosvenor House'' was dismantled and shipped back to England. It was later bought by the Air Ministry, given the military serial K5084, painted silver overall with RAF markings and flown to

''Grosvenor House'' was dismantled and shipped back to England. It was later bought by the Air Ministry, given the military serial K5084, painted silver overall with RAF markings and flown to RAF Martlesham Heath

Royal Air Force Martlesham Heath or more simply RAF Martlesham Heath is a former Royal Air Force station located southwest of Woodbridge, Suffolk, England. It was active between 1917 and 1963, and played an important role in the development of ...

for evaluation by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment. It made several flights before being written off in a heavy landing and sold for scrap. It was subsequently sold on, rebuilt by Essex Aero

Essex Aero Ltd. was an aircraft maintenance and component manufacturer, primarily based at Gravesend Airport in Kent, from 1936 to 1953.

Founded by Jack Cross, it is most famous for its rebuilding work on de Havilland DH.88 Comet racer G-ACSS an ...

and fitted with Gipsy Six series II engines and a castoring tailwheel. In this form it made several race and record attempts under various names. It claimed fourth place in the 1937 Istres-Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

- Paris race and 12th in the King's Cup

__NOTOC__

King's Cup (incl. translations), may refer to:

Sports Football

* Copa del Rey, Spanish for "King's Cup," the main national knockout tournament in men's football

* King Cup (sometimes named King's Cup), Saudi Arabian men's football nati ...

the next month. Later in the same year it lowered the out-and-home record to the Cape to 15 days 17 hours. In March 1938, A. E. Clouston

Air Commodore Arthur Edmond Clouston, (7 April 1908 – 1 January 1984) was a New Zealand-born British test pilot and senior officer in the Royal Air Force. He took part in several air races and record-breaking flights in the 1930s.

Early life

...

and Victor Ricketts made a return trip to New Zealand covering in 10 days 21 hours 22 minutes.

In G-ACSR, the day after they finished the race Cathcart Jones and Waller took off on the return journey. Suffering engine trouble, at Allahabad they found the Mollisons still there and were generously given two good pistons from ''Black Magic'' to allow them to continue. Arriving back in England they set a new round-trip record of 13 days, 6 hours and 43 minutes. That December, named ''Reine Astrid'' in honour of the Belgian queen, G-ACSR flew the Christmas mail from Brussels to Leopoldville in the Belgian Congo. It was then sold to the French government and modified as mail plane F-ANPY, its delivery flight setting a Croydon- Le Bourget record on 5 July 1935. It subsequently made Paris–Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

and Paris—Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

high-speed proving flights with the name Cité d'Angoulême IV. Formerly believed destroyed alongside F-ANPZ, F-ANPY was last seen in an unflyable condition at Étampes

Étampes () is a commune in the metropolitan area of Paris, France. It is located south-southwest from the center of Paris (as the crow flies). Étampes is a sub-prefecture of the Essonne department.

Étampes, together with the neighboring c ...

in France in 1940.Ricco 2010, p. 34.

''Black Magic'' was sold to Portugal for a projected flight from Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

to Rio de Janeiro. Re-registered CS-AAJ and renamed '' Salazar'' it was damaged on its attempted takeoff at Sintra Air Base

Sintra Air Base ( pt, Base Aérea de Sintra) , officially designated as Air Base No. 1 ( pt, Base Aérea Nº 1, BA1), is a Portuguese Air Force base located in the Sintra Municipality, Portugal. The base is home to a flight training squadron an ...

for the Atlantic crossing. On a later return flight from Hatfield it made a record flight from London to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, setting a time of 5 hr, 17 min in July 1937.

Other Comets

Following theFrench

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

government's acquisition of F-ANPY (see above), they ordered a fourth Comet, F-ANPZ, with a mail compartment in the nose. It was later taken on charge by the French Air Force before being destroyed in a hangar fire at Istres in France in June 1940.

The fifth and last Comet, registered G-ADEF and named ''Boomerang,'' was built for Cyril Nicholson. It was piloted by Tom Campbell Black and J. C. McArthur in an attempt on the London- Cape Town record. It reached Cairo in a record 11 hr, 18 min, but the next leg of the journey was cut short due to oil trouble while in flight over Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

.Lewis 1970, pp. 277–278. On 21 September 1935, Campbell Black and McArthur took off in "Boomerang" from Hatfield in another attempt at the Cape record. The aircraft crashed while flying over Sudan on 22 September 1935 due to propeller problems, the crew escaping by parachute.Lewis 1970, p. 280.

Record flights

The de Havilland Comets set many record times for long-distance flights during the 1930s, both during races and on special record-breaking flights. Some flights set multiple point-to-point records.Surviving aircraft

G-ACSS was requisitioned for the RAF once again in 1943 but soon passed on to de Havilland. Restored for static display as ''Grosvenor House'', it was put on show for the 1951

G-ACSS was requisitioned for the RAF once again in 1943 but soon passed on to de Havilland. Restored for static display as ''Grosvenor House'', it was put on show for the 1951 Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition and fair that reached millions of visitors throughout the United Kingdom in the summer of 1951. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" during which people:

...

. The Shuttleworth Collection

The Shuttleworth Collection is a working aeronautical and automotive collection located at the Old Warden Aerodrome, Old Warden in Bedfordshire, England. It is the oldest in the world and one of the most prestigious, due to the variety of old a ...

at Old Warden

Old Warden is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Central Bedfordshire district of the county of Bedfordshire, England, about south-east of the county town of Bedford.

The 2011 census shows its population as 328.

The ...

acquired it in 1965 and then in 1972 re-registered it under its original identity for restoration to flying condition, finally achieved in 1987. It is regarded as "one of the most significant British aircraft still flying."

CS-AAJ ''Salazar'' was rediscovered in Portugal after being lost for more than 40 years. It was brought back to the UK and re-registered once again as G-ACSP. As of 2020 restoration continues, with a view to it flying again in its original livery as ''Black Magic'', by the Comet Racer Project Group at the Amy Johnson Comet Restoration Centre,

CS-AAJ ''Salazar'' was rediscovered in Portugal after being lost for more than 40 years. It was brought back to the UK and re-registered once again as G-ACSP. As of 2020 restoration continues, with a view to it flying again in its original livery as ''Black Magic'', by the Comet Racer Project Group at the Amy Johnson Comet Restoration Centre, Derby Airfield

Derby Airfield is a small privately owned grass airfield situated between the Derbyshire villages of Egginton and Hilton, in the East Midlands of England. The airfield is 7 miles southwest of Derby, and 11 miles northeast of Tatenhill Airfiel ...

.Hope, Brian"Restoration: Black Magic."

''Light Aviation Association'', November 2011. pp. 16–19.

Airworthy reproductions and replicas

N88XD is a full-scale flying replica Comet. Built in 1993 for Thomas W. Wathen of Santa Barbara, CA by Bill Turner of Repeat Aircraft at Flabob Airport in Rubidoux, California, it wears the livery of G-ACSS ''Grosvenor House''. A replica, originally started by George Lemay in Canada, was acquired by the Croydon Aircraft Company based at Old Mandeville Airfield, near Gore, New Zealand, where it is currently still under construction. G-RCSR is a reproduction Comet based on the original construction drawings, being built by Ken Fern in parallel with the restoration of ''Black Magic'' at Derby.Operators

; :* Armée de l'Air ; :*Portuguese Government ; :* Air Ministry (for evaluation) :*Shuttleworth Collection

The Shuttleworth Collection is a working aeronautical and automotive collection located at the Old Warden Aerodrome, Old Warden in Bedfordshire, England. It is the oldest in the world and one of the most prestigious, due to the variety of old a ...

Specifications

Cultural influence

The MacRobertson Air Race was an event of world-wide importance and did much to drive aeroplane design forward. The triumph of the Comet and its high-speed design marked a milestone in aviation.

The Comet Hotel, Hatfield was begun the year before the race, as one of the first modernist inns in England. Located close to the de Havilland factory, when it was finished it was named after the Comet Racer. War artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a carved column in its car park, which was erected in 1936. On its top is mounted a famous model of the Comet, currently in the livery of ''Grosvenor House''.

Full-scale but non-flying replicas of ''Grosvenor House'' and ''Black Magic'' were constructed for the 1990 TV two-part Australian-produced dramatisation ''Half a World Away'', which was also released on DVD as '' The Great Air Race''. The G-ACSS replica was taxi-able and has since been partially restored in the livery of G-ACSR and is on static display at the De Havilland Aircraft Museum,

The MacRobertson Air Race was an event of world-wide importance and did much to drive aeroplane design forward. The triumph of the Comet and its high-speed design marked a milestone in aviation.

The Comet Hotel, Hatfield was begun the year before the race, as one of the first modernist inns in England. Located close to the de Havilland factory, when it was finished it was named after the Comet Racer. War artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a carved column in its car park, which was erected in 1936. On its top is mounted a famous model of the Comet, currently in the livery of ''Grosvenor House''.

Full-scale but non-flying replicas of ''Grosvenor House'' and ''Black Magic'' were constructed for the 1990 TV two-part Australian-produced dramatisation ''Half a World Away'', which was also released on DVD as '' The Great Air Race''. The G-ACSS replica was taxi-able and has since been partially restored in the livery of G-ACSR and is on static display at the De Havilland Aircraft Museum, Salisbury Hall

The de Havilland Aircraft Museum, formerly the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, is a volunteer-run aviation museum in London Colney, Hertfordshire, England. The collection is built around the definitive prototype and restoration shops fo ...

, UK., De Havilland Aircraft Museum. (Retrieved 15 July 2019). Comets have also appeared in fiction, see Aircraft in fiction#de Havilland DH.88 Comet.

See also

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

"For the England Australia Air Race: The de Havilland 'Comet'

'' Flight'', Volume 26, No. 1343, 20 September 1934, pp. 968–972. * Jackson, A. J. ''De Havilland Aircraft Since 1909''. London: Putnam, Third edition, 1987. . * Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record Breaking Aircraft''. London: Putnam, 1970. . * * Ogilvy, David. ''DH88: deHavilland's Racing Comets''. Shrewsbury, Airlife, 1988. . * Ramsden, J. M. "The Comet's Tale – Part 2". '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 16, No. 5. May 1988. pp. 279–283. ISSN 0143-7240. * Ricco, Philippe. "La Comète en France, Part 1", '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 35, No. 439. November 2009. * Ricco, Philippe. "La Comète en France, Part 2: The Burden of Proof". '' Aeroplane Monthly'', Vol. 38, No. 449. September 2010. * Sharp, C. Martin; ''DH: An Outline of de Havilland History''. London, Faber & Faber, 1960. * Taylor, H. A. "The First "Wooden Wonder"". '' Air Enthusiast'', No. 10, July–September 1979. pp. 51–57.

"The Story of the Australia Race"

'' Flight'', Volume 26, No. 1348, 25 October 1934, pp. 1110–1117.

External links

Sound recording of G-ACSS

Aircraft Sound Recordings.

video of G-ACSS arriving in Australia

{{de Havilland aircraft Racing aircraft 1930s British mailplanes 1930s British sport aircraft DH.088 Low-wing aircraft Aircraft first flown in 1934 Twin piston-engined tractor aircraft