The Winter of Discontent was the period between November 1978 and February 1979 in the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

characterised by widespread strikes by private, and later public, sector

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (s ...

s demanding pay rises greater than the limits Prime Minister

James Callaghan and his

Labour Party government had been imposing, against

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances O ...

(TUC) opposition, to control inflation. Some of these industrial disputes caused great public inconvenience, exacerbated by the coldest winter

in 16 years, in which severe storms isolated many remote areas of the country.

A strike by workers at

Ford in late 1978 was settled with a pay increase of 17 per cent, well above the 5 per cent limit the government was holding its own workers to with the intent of setting an example for the private sector to follow, after a resolution at the Labour Party's annual conference urging the government not to intervene passed overwhelmingly. At the end of the year a road hauliers' strike began, coupled with a severe storm as 1979 began. Later in the month many public workers followed suit as well. These actions included an unofficial strike by

gravedigger

A gravedigger is a cemetery worker who is responsible for digging a grave prior to a funeral service.

Description

If the grave is in a cemetery on the property of a church or other religious organization (part of, or called, a churchyard), ...

s working in

Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

and

Tameside

The Metropolitan Borough of Tameside is a metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester in England. It is named after the River Tame, which flows through the borough, and includes the towns of Ashton-under-Lyne, Audenshaw, Denton, Droylsden, Duk ...

, and strikes by refuse collectors, leaving uncollected rubbish on streets and in public spaces, including London's

Leicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester ...

. Additionally,

NHS ancillary workers formed picket lines to blockade hospital entrances with the result that many hospitals were reduced to taking emergency patients only.

The unrest had deeper causes besides resentment of the caps on pay rises. Labour's internal divisions over its commitment to socialism, manifested in disputes over labour law reform and macroeconomic strategy during the 1960s and early 1970s, pitted constituency members against the party's establishment. Many of the strikes were initiated at the local level, with national union leaders largely unable to stop them. Union membership, particularly in the public sector, had grown more female and less white, and the growth of the public sector unions had not brought them a commensurate share of power within the TUC.

After Callaghan returned from a summit conference in the tropics at a time when the hauliers' strike and the weather had seriously disrupted the economy, leading thousands to apply for unemployment benefits, his denial that there was "mounting chaos" in the country was paraphrased in a famous ''

Sun'' headline as "Crisis? What Crisis?"

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

leader

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

's acknowledgement of the severity of the situation in a

party political broadcast a week later was seen as instrumental to her victory in the

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

held four months later after

Callaghan's government fell to a no-confidence vote. Once in power, the Conservatives, who under Thatcher's leadership had begun criticising the unions as too powerful, passed legislation, similar to that proposed in a

Labour white paper a decade earlier, that banned many practices, such as

secondary picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pick ...

, that had magnified the effects of the strikes. Thatcher, and later other

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

like

Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (; born 19 June 1964) is a British politician, writer and journalist who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He previously served as F ...

, have continued to invoke the Winter of Discontent in election campaigns; it would be

18 years until another Labour government took power. In the late 2010s, after the more left wing

Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the pol ...

became Labour leader, some British leftists argued that this narrative about the Winter of Discontent was inaccurate, and that policy in subsequent decades was much more harmful to Britain.

The term "Winter of Discontent" is taken from the opening line of

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's play ''

Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

''.

It is credited to

Larry Lamb

Lawrence Douglas Lamb (born 1 October 1947) is an English actor and radio presenter. He played Archie Mitchell in the BBC soap opera ''EastEnders'', Mick Shipman in the BBC comedy series '' Gavin & Stacey'' and Ted Case in the final series ...

, then editor at ''

The Sun'', in an editorial on 3 May 1979.

Background

The Winter of Discontent was driven by a combination of different social, economic and political factors which had been developing for over a decade.

Divisions in Labour Party over macroeconomic strategy

Under the influence of

Anthony Crosland, a member of the more moderate

Gaitskellite wing of the Labour Party in the 1950s, the party establishment came to embrace a more moderate course of action than it had in its earlier years before the war. Crosland had argued in his book ''

The Future of Socialism'' that the government exerted enough control over private industry that it was not necessary to

nationalise it as

the party had long called to do, and that the ultimate goals of

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

could be as readily achieved by assuring long-term economic stability and building out the social

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitab ...

. His "

revisionist" views became Labour's perspective on the

post-war consensus, in which both they and the

Conservative Party agreed in principle on a strong government role in the economy, strong unions and a welfare state as foundational to Britain's prosperity.

In the 1970s, following the surge in radical left-wing politics of the late 1960s, that view was challenged in another Labour figure's book,

Stuart Holland's ''The Socialist Challenge''. He argued that contrary to Crosland's assertions, the government could exercise little control over Britain's largest companies, which were likely to continue consolidating into an

oligopoly

An oligopoly (from Greek ὀλίγος, ''oligos'' "few" and πωλεῖν, ''polein'' "to sell") is a market structure in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of large sellers or producers. Oligopolies often result fr ...

that, by the 1980s, could raise prices high enough that governments following

Keynesian economics

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output ...

would be unable to ensure their citizens the opportunity for

full employment

Full employment is a situation in which there is no cyclical or deficient-demand unemployment. Full employment does not entail the disappearance of all unemployment, as other kinds of unemployment, namely structural and frictional, may remain. Fo ...

that they had been able to since the war, and exploit

transfer pricing to avoid paying British taxes. Holland called for returning to nationalisation, arguing that taking control of the top 25 companies that way would result in a market with more competition and less inflation.

Holland's ideas formed the basis of the

Alternative Economic Strategy

The Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) is the name of an economic programme proposed by Tony Benn, a dissident member of the British Labour Party, during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Secretary of State for Industry in the Labour government, Tony ...

(AES) promoted by

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

, then

Secretary of State for Industry in the Labour governments of

Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

and

James Callaghan as they considered responses to

the sterling crisis in 1976. The AES called on Britain to adopt a

protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations ...

stance in international trade, including reversing

its recent decision to join the European Common Market, and impose no incomes policies to combat inflation. Benn believed that this approach was more in keeping with Labour's traditional policies and would have its strongest supporters in the unions, with them vigorously supporting the government against opposition from the financial sector and "commanding heights" of industry. It was ultimately rejected in favour of the

social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Social ...

and extensive cuts in public spending as the condition of an

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster gl ...

loan that supported the pound after the

1976 sterling crisis.

The left wing of the Labour Party, while critical of the revisionist approach and the Social Contract, was not universally supportive of the AES either. Many thought it did not go far enough, or avoided the issue of nationalisation.

Feminists in particular criticised it for its focus on traditionally male-dominated manufacturing jobs and ignoring the broader issues that the increasing number of women in the workforce faced, preferring a focus on broader social issues rather than just working conditions and pay, the traditional areas unions had negotiated with employers.

1960s–70s labour law reforms

In 1968 Wilson's government appointed the

Donovan Commission to review

British labour law

United Kingdom labour law regulates the relations between workers, employers and trade unions. People at work in the UK can rely upon a minimum charter of employment rights, which are found in Acts of Parliament, Regulations, common law and equit ...

with an eye toward reducing the days lost to strikes every year; many Britons had come to believe the unions were too powerful despite the country's economic growth since the war. It found much of the problem to lie in a parallel system of 'official' signed agreements between unions and employers, and

'unofficial', often unwritten ones at the local level, between

shop steward

A union representative, union steward, or shop steward is an employee of an organization or company who represents and defends the interests of their fellow employees as a labor union member and official. Rank-and-file members of the union hold ...

s and managers, which often took precedence in practice over the official ones. The government responded with ''

In Place of Strife'', a

white paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white pape ...

by

Secretary of State for Employment Barbara Castle

Barbara Anne Castle, Baroness Castle of Blackburn, (''née'' Betts; 6 October 1910 – 3 May 2002), was a British Labour Party politician who was a Member of Parliament from 1945 to 1979, making her one of the longest-serving female MPs in B ...

, which recommended restrictions on unions' ability to strike, such as requiring strikes take place after a member vote and fining unions for unofficial strikes.

The

Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances O ...

(TUC) vigorously opposed making Castle's recommendations law, and Callaghan, then

Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, led a cabinet revolt which led to its abandonment. Callaghan did not believe it would be effective in curtailing unofficial strikes, that the proposals could not pass, and the effort would create unnecessary tension between the government and the unions that were key to its political strength.

[, cited at ]

After the Conservatives won

the following year's election, they implemented their own legislation to address the issue. The

Industrial Relations Act 1971, modeled in part on the U.S.

Taft-Hartley Act, passed over determined union opposition, included many of the same provisions as ''In Place of Strife'', and explicitly stated that formal

collective bargaining agreement

A collective agreement, collective labour agreement (CLA) or collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is a written contract negotiated through collective bargaining for employees by one or more trade unions with the management of a company (or with an ...

s would have the force of law unless they had

disclaimer

A disclaimer is generally any statement intended to specify or delimit the scope of rights and obligations that may be exercised and enforced by parties in a legally recognized relationship. In contrast to other terms for legally operative langua ...

s to the contrary. It also created a

National Industrial Relations Court to handle disputes and put unions under a central registry to enforce their rules.

New Prime Minister

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

hoped that the new law would not only address the strike issue but the steep

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

plaguing the British economy (along with other industrial capitalist economies) at the time, eliminating the need for a separate

incomes policy by having a moderating effect on pay increases demanded by unions. Ongoing union resistance to the Industrial Relations Act led to a

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster ...

ruling in their favor over demonstrations and widespread unofficial strikes following the

Pentonville Five's imprisonment for continuing to picket a London container depot in violation of a court order, which undermined the legislation. Coal miners

officially went on strike for the first time in almost half a century in 1972; after two months the strike was settled with the miners getting a 21 per cent increase, less than half of what they had originally sought.

Heath as a result turned to an incomes policy; inflation continued to worsen. Its implementation was abandoned in 1973 when

that year's oil embargo nearly doubled prices within months. To meet demand for heat in the wintertime, the government had to return to coal, giving the

National Union of Mineworkers more leverage. The government declared a

state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

that November, and at the beginning of 1974 limited all nonessential businesses to

three days of electricity each week to conserve power. Miners, who had seen their rise from two years before turn into a pay cut in real terms due to the inflation the government had not brought under control, voted overwhelmingly to go on strike in late January.

Two weeks later, the government responded by calling

an election, running on the slogan "Who Governs Britain?". At the end of the month the Conservatives no longer did; Labour and Wilson returned, but

without a majority. They were able to pass the

Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974

The Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974c 37 (abbreviated to "HSWA 1974", "HASWA" or "HASAWA") is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that defines the fundamental structure and authority for the encouragement, regulation and enfor ...

, which repealed the Heath government's Industrial Relations Act.

In

October

October is the tenth month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars and the sixth of seven months to have a length of 31 days. The eighth month in the old calendar of Romulus , October retained its name (from Latin and Greek ''ôct� ...

they won a majority of three seats; still they needed a coalition with the

Liberal Party to have a majority on many issues. Callaghan, now

Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

, warned his fellow Cabinet members at the time of the possibility of "a breakdown of democracy", telling them that "If I were a young man, I would emigrate."

Incomes policy

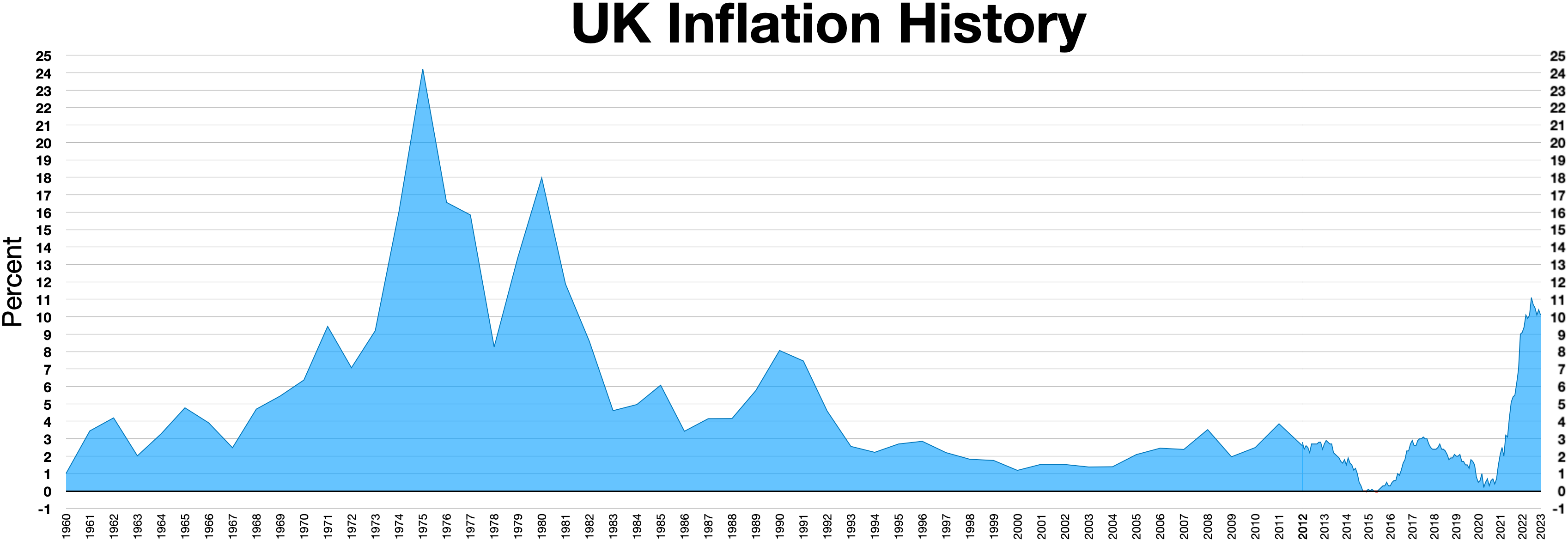

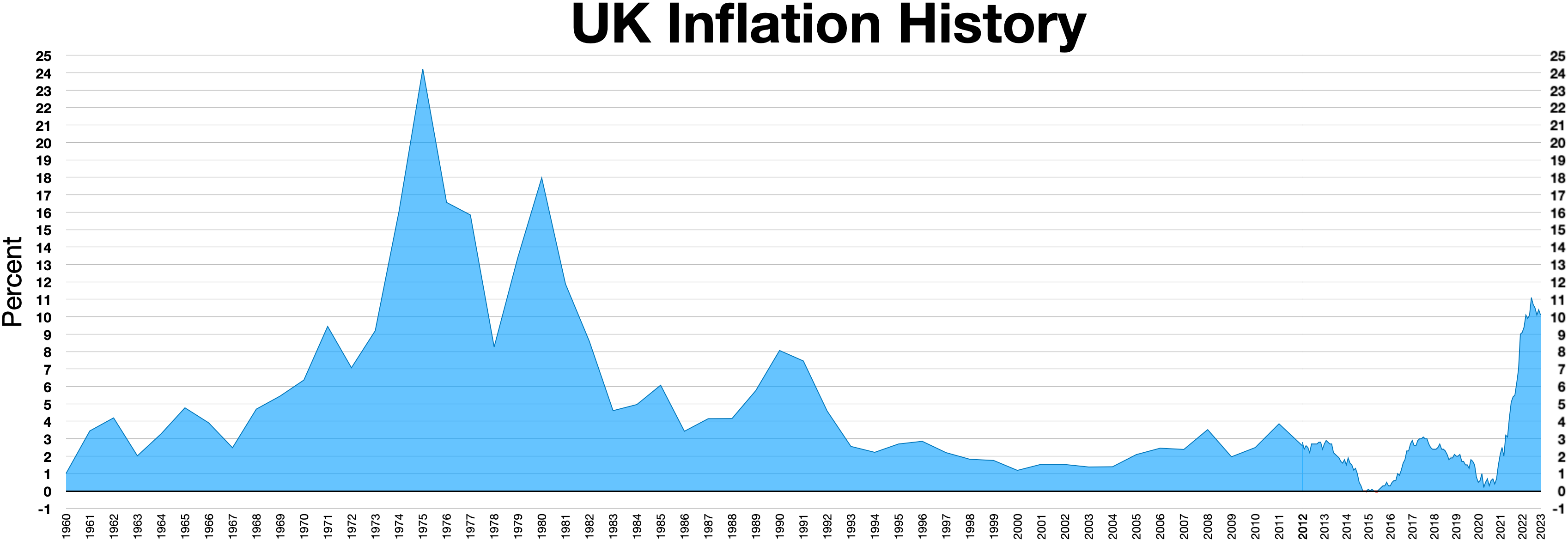

Wilson, and Callaghan, who succeeded him as Prime Minister after Wilson resigned for health reasons in 1976, continued to fight inflation, which peaked at 26.9 per cent in the 12 months to August 1975. While demonstrating to markets

fiscal responsibility the government wished to avoid large increases in unemployment. As part of the campaign to bring down inflation, the government had agreed a "

Social Contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Social ...

" with the TUC which allowed for a voluntary

incomes policy in which the pay rises for workers were held down to limits set by the government. Previous governments had brought in incomes policies backed by

Acts of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliament ...

, but the Social Contract agreed that this would not happen.

[

]

Phases I and II

Phase I of the pay policy was announced on 11 July 1975 with a white paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white pape ...

entitled ''The Attack on Inflation''. This proposed a limit on wage rises of £6 per week for all earning below £8,500 annually. The TUC General Council had accepted these proposals by 19 votes to 13. On 5 May 1976 the TUC accepted a new policy for 1976 increases, beginning 1 August, of between £2.50 and £4 per week with further years outlined. At the Annual Congress on 8 September 1976 the TUC rejected a motion which called for a return to free collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The ...

(which meant no incomes policy at all) once Phase I expired on 1 August 1977. This new policy was Phase II of the incomes policy.[

]

Phase III

On 15 July 1977, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey announced Phase III of the incomes policy in which there was to be a phased return to free collective bargaining, without "a free-for-all". After prolonged negotiations, the TUC agreed to continue with the modest increases recommended for 1977–78 under Phase II limits and not to try to reopen pay agreements made under the previous policy, while the government agreed not to intervene in pay negotiations. The Conservative Party criticised the power of the unions and lack of any stronger policy to cover the period from the summer of 1978. The inflation rate continued to fall through 1977 and by 1978 the annual rate was below 10 per cent.[

At the end of the year Bernard Donoughue, Callaghan's chief policy advisor, sent him a memo analysing possible election dates. He concluded that the following October or November would be the best option, as the economy was likely to remain in good shape through then. After that, he wrote, the outlook was unclear, with pressure from the government's own incomes policy likely.][, cited at ]

Five per cent limit

At a May 1978 Downing Street lunch with editors and reporters from the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its masthead was simply ''The Mirror''. It had an average daily print ci ...

'', Callaghan asked if they believed it was possible that the planned Phase IV would succeed, as he believed it would if the unions and their members understood it was the best way to keep Labour in power. Most told him that it would be difficult, but not impossible. Geoffrey Goodman disagreed, saying in his view it would be impossible for the union leaders to keep their membership from demanding higher pay increases. "If that is the case, then I will go over the heads of the trade union leadership and appeal directly to their members—and the voters", the prime minister responded. "We have to hold the line on pay or else the government will fall."[, cited at ]

Having prepared for the imminent end of the incomes policy, global inflation supervened and was coming towards record levels during the 1978–82 period. On 21 July 1978 Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey introduced a new white paper which set a guideline for pay rises of 5 per cent in the year from 1 August. Callaghan was determined to keep inflation down to single figures, however trade union leaders warned the government that the 5 per cent limit was unachievable, and urged a more flexible approach with a range of settlements between 5 and 8 per cent. Terry Duffy president of the AUEW, described the limit as 'political suicide'. Healey also privately expressed scepticism about the achievability of the limit. The TUC voted overwhelmingly on 26 July to reject the limit and insist on a return to free collective bargaining as they were promised.[

It had been widely expected that Callaghan would call a general election in the autumn, and that the 5 per cent limit would be revised if Labour won. At a private dinner before that year's TUC conference, Callaghan discussed election strategy with the leaders of major unions. He asked whether he should call an autumn election; with the exception of Scanlon they all urged him to call for one no later than November. Any later, they said, and they could not guarantee their memberships would remain on the job and off the picket line through the winter.][, cited at ]

Unexpectedly however on 7 September, Callaghan announced that he would not be calling a general election that autumn but seeking to go through the winter with continued pay restraint so that the economy would be in a better state in preparation for a spring election, therefore the 5 per cent limit stood. The pay limit was officially termed "Phase IV" but most referred to it as "the 5 per cent limit". Although the government did not make the 5 per cent limit a legal requirement, it decided to impose penalties on private and public government contractors who broke the limit.

Changes in labour movement

Between 1966 and 1979, Britain's unions were changing and becoming more diverse. Most of the increase in union membership was driven by women returning to or entering the workforce—73 per cent of them joined a union during that period against 19.3 per cent of men newly in work, as manufacturing jobs, traditionally heavily male, disappeared. Black and Asian workers also filled union ranks; in 1977, 61 per cent of black men in work belonged to a union as opposed to 47 per cent of white men.participatory democracy

Participatory democracy, participant democracy or participative democracy is a form of government in which citizens participate individually and directly in political decisions and policies that affect their lives, rather than through elected rep ...

to the fore, and workers felt they should be taking decisions, including about when and whether to strike, that had hitherto been the province of union leadership. Hugh Scanlon, who took over as head of the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers (AUEW) in 1967, and Jack Jones Jack Jones may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

*Jack Jones (American singer) (born 1938), American jazz and pop singer

*Jack Jones, stage name of Australian singer Irwin Thomas (born 1971)

*Jack Jones (Welsh musician) (born 1992), Welsh mu ...

, general secretary of the Transport and General Workers' Union

The Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU or T&G) was one of the largest general trade unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland – where it was known as the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers' Union (ATGWU) to differentiate its ...

(TGWU) from shortly afterwards, were known among union leaders as "the dubious duo" for their advocacy for devolution.

Dissatisfied public employees

Many new members were also coming from government jobs. In 1974, about half of the total British workforce was unionised, but 83.1 per cent of all public-sector workers were. In the health sector that reached 90 per cent. Many of the government workers joining unions were women.state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

and bringing in Army troops as replacements. The TUC voted late in the strike to not campaign in support of the firemen, in order to maintain its relationship with the government.

"Stepping Stones" and hardening of Conservative position on unionism

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

was elected Conservative leader to succeed Heath in 1975. She had been known as a member of his Cabinet, where she served as Secretary of State for Education

The secretary of state for education, also referred to as the education secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the work of the Department for Education. ...

, for her advocacy of market-based solutions over government intervention in the economy, and had become convinced, as she wrote later, by that experience that the only thing more damaging to the British economy than Labour's socialist policies was her own party's attempts to emulate them. Influenced by writers such as Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek ( , ; 8 May 189923 March 1992), often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian–British economist, legal theorist and philosopher who is best known for his defense of classical liberalism. Hayek ...

and Colm Brogan, she came to believe the power of British unions under the postwar consensus

The post-war consensus, sometimes called the post-war compromise, was the economic order and social model of which the major political parties in post-war Britain shared a consensus supporting view, from the end of World War II in 1945 to the ...

had come at the expense of Britain as a whole.Stepping Stones

Stepping stones or stepstones are sets of stones arranged to form an improvised causeway that allows a pedestrian to cross a natural watercourse such as a river; or a water feature in a garden where water is allowed to flow between stone steps. ...

" which diagrammed the vicious cycle through which they believed the unions' influence exacerbated Britain's ongoing economic difficulties, such as unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refer ...

and inflation. Thatcher made it available to her shadow cabinet with the authors' recommendation that they all read it. By the end of the year she had formed a steering group to develop a specific policy aimed at curbing union power under a Tory government, and a media strategy that would invest the public in this.Larry Lamb

Lawrence Douglas Lamb (born 1 October 1947) is an English actor and radio presenter. He played Archie Mitchell in the BBC soap opera ''EastEnders'', Mick Shipman in the BBC comedy series '' Gavin & Stacey'' and Ted Case in the final series ...

met frequently with Thatcher's media advisor Gordon Reece to plan and refine strategy.

Ford negotiations

Although not an official guideline, the pay rise set by Ford of Britain

Ford of Britain (officially Ford Motor Company Limited)The Ford 'companies' or corporate entities referred to in this article are:

* Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, Michigan, USA, incorporated 16 June 1903

* Ford Motor Company Limited, incorpora ...

was accepted throughout private industry as a benchmark for negotiations. Ford had enjoyed a good year, and could afford to offer a large pay rise to its workers.Transport and General Workers Union

The Transport and General Workers' Union (TGWU or T&G) was one of the largest general trade unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland – where it was known as the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers' Union (ATGWU) to differentiate its ...

(TGWU), began an unofficial strike on 22 September 1978, which subsequently became an official TGWU action on 5 October. The number of participants grew to 57,000. The strike prevented the production of 115,000 vehicles which cost Ford around $885 million.

During the strike, Vauxhall Motors

Vauxhall Motors LimitedCompany No. 00135767. Incorporated 12 May 1914, name changed from Vauxhall Motors Limited to General Motors UK Limited on 16 April 2008, reverted to Vauxhall Motors Limited on 18 September 2017. () is a British car compa ...

employees accepted an 8.5 per cent rise. After long negotiation in which they weighed the chances of suffering from government sanctions against the continued damage of the strike, Ford eventually revised their offer to 17 per cent and decided to accept the sanctions; Ford workers accepted the rise on 22 November

Political difficulties

As the Ford strike was starting, the Labour Party conference began at

As the Ford strike was starting, the Labour Party conference began at Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, between the Ribble and Wyre rivers, and ...

. Terry Duffy, the delegate from Liverpool Wavertree Constituency Labour Party and a supporter of the Militant

The English word ''militant'' is both an adjective and a noun, and it is generally used to mean vigorously active, combative and/or aggressive, especially in support of a cause, as in "militant reformers". It comes from the 15th century Latin " ...

group, moved a motion on 2 October which demanded "that the Government immediately cease intervening in wage negotiations". Despite a plea from Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the '' Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 ...

not to put the motion to the vote, the resolution was carried by 4,017,000 to 1,924,000. The next day, the Prime Minister accepted the fact of defeat by saying "I think it was a lesson in democracy yesterday", but insisted that he would not let up on the fight against inflation.

Meanwhile, the government's situation in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

was increasingly difficult; through by-elections it had lost its majority of three seats in 1976 and had been forced to put together a pact

A pact, from Latin ''pactum'' ("something agreed upon"), is a formal agreement between two or more parties. In international relations, pacts are usually between two or more sovereign states. In domestic politics, pacts are usually between two or ...

with the Liberal Party in 1977 in order to keep winning votes on legislation; the pact lapsed in July 1978. A decision to grant extra parliamentary seats to Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

afforded temporary support from the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule ...

, but the Unionists were clear that this support would be withdrawn immediately after the bill to grant extra seats had been passed – it was through the Ulster Unionists agreeing to abstain that the government defeated a motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

by 312 to 300 on 9 November.[

]

Further negotiation at the TUC

By the middle of November it was clear that Ford would offer an increase substantially over the 5 per cent limit. The government subsequently entered into intense negotiations with the TUC, hoping to produce an agreement on pay policy that would prevent disputes and show political unity in the run-up to the general election. A limited and weak formula was eventually worked out and put to the General Council of the TUC on 14 November, but its General Council vote was tied 14–14, with the formula being rejected on the chair's casting vote. One important personality on the TUC General Council had changed earlier in 1978 with Moss Evans replacing Jack Jones Jack Jones may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

*Jack Jones (American singer) (born 1938), American jazz and pop singer

*Jack Jones, stage name of Australian singer Irwin Thomas (born 1971)

*Jack Jones (Welsh musician) (born 1992), Welsh mu ...

at the TGWU. Evans proved a weak leader of his union, although it is doubtful whether Jones could have restrained the actions of some of the TGWU shop stewards.

After Ford settled, the government announced on 28 November that sanctions would be imposed on Ford, along with 220 other companies, for breach of the pay policy. The announcement of actual sanctions produced an immediate protest from the Confederation of British Industry

The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) is a UK business organisation, which in total claims to speak for 190,000 businesses, this is made up of around 1,500 direct members and 188,500 non-members. The non members are represented through the 1 ...

which announced that it would challenge their legality. The Conservatives put down a motion in the House of Commons to revoke the sanctions. A co-ordinated protest by left-wing Labour MPs over spending on defence forced the debate set for 7 December to be postponed; however on 13 December an anti-sanctions amendment was passed by 285 to 279. The substantive motion as amended was then passed by 285 to 283. James Callaghan put down a further motion of confidence for the next day, which the government won by ten votes (300 to 290), but accepted that his government could not use sanctions. In effect this deprived the government of any means of enforcing the 5 per cent limit on private industry.

Onset of severe winter weather

A mild autumn turned cold on the morning of 25 November when temperatures recorded at Heathrow Airport dropped from to overnight, with some snowflakes. Throughout most of the following month, the cold lingered, only for temperatures to rise well above around Christmas. On 30 December, the temperature dropped again, along with rain that soon turned to snow; the next day 1978 ended with Heathrow recording a high of only amid steady snowfall.North Devon

North Devon is a local government district in Devon, England. North Devon Council is based in Barnstaple. Other towns and villages in the North Devon District include Braunton, Fremington, Ilfracombe, Instow, South Molton, Lynton and ...

could only be reached by helicopter as many roads could not be adequately cleared. The Royal Automobile Club

The Royal Automobile Club is a British private social and athletic club. It has two clubhouses: one in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a ...

blamed local councils, who in turn pointed to unresolved issues with their unions and staff shortages; even around London local authorities were only able to clear main roads. Two Scottish trains near Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

were stuck in the snow, leaving 300 passengers stranded; rail transport difficulties were exacerbated elsewhere in the country by a strike. Tanker drivers had also gone on strike in some areas from 18 December, causing some homeowners to have difficulties keeping their homes heated and limiting petrol supplies. Only three League football matches could take place over the New Year's The expression New Year's is a colloquial term with unclear definition. It may mean any or all of the following:

*

*

**

*

** New Year's Day#Traditional and modern celebrations and customs

*

*

* (2 January)

See also

* New Year's Day (disamb ...

holiday, and all rugby contests were cancelled. Three men drowned after falling through the ice on the Hampstead Heath

Hampstead Heath (locally known simply as the Heath) is an ancient heath in London, spanning . This grassy public space sits astride a sandy ridge, one of the highest points in London, running from Hampstead to Highgate, which rests on a band ...

pond in London.

Lorry drivers' strike

With the government now having no way of enforcing its pay policy, unions which had not yet put in pay claims began to increase their aim. Lorry

A truck or lorry is a motor vehicle designed to transport cargo, carry specialized payloads, or perform other utilitarian work. Trucks vary greatly in size, power, and configuration, but the vast majority feature body-on-frame constructi ...

drivers, represented by the TGWU, had demanded rises of up to 40 per cent on 18 December; years of expansion in the industry had left employers short of drivers, and those drivers who had jobs often worked 70–80 hours a week for minimal pay. The Road Haulage Association (RHA), the industry trade group, had initially told Secretary of State for Transport William Rodgers, a member of the Labour Party's right wing who had become sceptical of the public's appetite for the completion of the party's socialist programme, that it would stay within the 5 per cent ceiling. But as 1979 began, the RHA, whom Rodgers saw as disorganised and easily intimidated by the TGWU, suddenly increased its offer to 13 per cent, in hopes of settling before strikes became widespread.

The offer had the opposite effect. Drivers, emboldened by memories of a strike the previous winter by South Wales hauliers that won participants a 20 per cent rise, decided they could do better by walking out. The union's national leadership was, as they had anticipated in their September dinner with Callaghan, doubtful they could restrain the local leaders. On 2 January Rodgers warned the Cabinet that a national road-haulage strike was about to happen, but cautioned against pressuring the RHA to improve their offer even more.

The next day an unofficial strike of all TGWU lorry drivers began. With petrol distribution held up, petrol stations closed across the country. The strikers also picketed the main ports. The strikes were made official on 11 January by the TGWU and 12 January by the United Road Transport Union. With 80 per cent of the nation's goods transported by road, roads still not completely cleared from the earlier storm, essential supplies were put in danger as striking drivers picketed those firms that continued to work. While the oil tanker drivers were working, the main refineries were also targeted and the tanker drivers let the strikers know where they were going, allowing for flying pickets to turn them back at their destination. More than a million UK workers were laid off temporarily during the disputes.

In Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually abbreviated to Hull, is a port city and unitary authorities of England, unitary authority in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, inland from ...

, striking hauliers were able to blockade the city's two main roads effectively enough to control what goods were allowed into and out of the city, and companies made their case to their own nominal employees to get past the barricades. Newspaper headlines likened the situation to a siege, and the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II where Nazi Germany and its allies unsuccessfully fought the Soviet Union for control of the city of Stalingrad (later re ...

; fears that food supplies would also be impacted fuelled panic buying

Panic buying (alternatively hyphenated as panic-buying; also known as panic purchasing) occurs when consumers buy unusually large amounts of a product in anticipation of, or after, a disaster or perceived disaster, or in anticipation of a large ...

. Such coverage often exaggerated the reach of the strikers, which served both their interest and their employers'. It also helped the Conservatives disseminate the arguments of "Stepping Stones" about unionism out of control to the public; letters to the editor across the country reflected a growing public anger with the unions.

Due to the disruption of fuel supplies, the Cabinet Office prepared to implement previous plans for "Operation Drumstick", by which the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

were put on standby to take over from the tanker drivers. However, the operation would need the declaration of a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

in order to allow conscription of the assets of the oil companies, and the government drew back from such a step on 18 January. Rodgers in particular was opposed to it, since the available troops could at best only make up for a very small portion of the striking drivers, and it might be possible to use them more effectively without declaring an emergency. Before the situation developed into a crisis the oil companies settled on wage rises of around 15 per cent.

The Cabinet also decided that same day that it would not take action to limit any hauling company's profits, thereby allowing them to increase their offer to the strikers. Rodgers was so disheartened by this that he wrote a resignation letter to Callaghan, saying "the Government is not even in the front line" and accusing it of "defeatism of a most reprehensible kind". He ultimately decided to remain in the Cabinet.Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

did not allow the correct mix of animal feed through to local farms, the farmers dropped the bodies of dead piglets and chickens outside the union offices; the union contended that the farmers had actually wrung the chicken's necks to kill them, and the piglets had been killed when the sow rolled over and crushed them.Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, violence erupted on 17 January when three hundred women working at the Cadbury Schweppes plant in Bournville heard that a flying picket was moving into place to attempt to block a delivery. Swinging their pocketbooks and umbrellas, they quickly drove away the striking lorry drivers, whom they outnumbered by twenty to one. The incident made national news.Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

town of Oakengates organised a convoy, but it was unable to leave town as the ungritted roads proved too slippery to drive.The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econ ...

'' reported that many predicted shortages of foods had not actually taken place. Douglas Smith of the Employment Department recalled years later that he only recalled certain breakfast cereals being out of stock, and Rodgers, too, agreed that the job losses had not been as severe as they seemed they would be. But the fears of disruption had had an impact on the national mood even if little of what was feared had actually come to pass.

Media response by Callaghan and Thatcher

"Crisis? What crisis?"

While Britain was dealing with the strike and the aftermath of the storm, Callaghan was in the Caribbean, attending a summit in Guadeloupe with U.S. President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

, German chancellor Helmut Schmidt

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt (; 23 December 1918 – 10 November 2015) was a German politician and member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who served as the chancellor of West Germany from 1974 to 1982.

Before becoming C ...

and French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry René Marie Georges Giscard d'Estaing (, , ; 2 February 19262 December 2020), also known as Giscard or VGE, was a French politician who served as President of France from 1974 to 1981.

After serving as Minister of Finance under prime ...

discussing the growing crisis in Iran and the proposed SALT II

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds o ...

arms control treaty with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. He also spent a few days afterwards on holiday in Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate ...

, where he was photographed by the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' wearing a bathing suit and swimming in the sun. The newspaper used the images at the end of a lengthy leader

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets view ...

lamenting the state of affairs in Britain.Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'') "What is your general approach, in view of the mounting chaos in the country at the moment?" and replied:

The next day's edition of '' The Sun'' headlined its story "Crisis? What crisis?" with a subheading "Rail, lorry, jobs chaos – and Jim blames Press", condemning Callaghan as being "out of touch" with British society.Supertramp

Supertramp were an English rock band that formed in London in 1969. Marked by the individual songwriting of founders Roger Hodgson (vocals, keyboards, and guitars) and Rick Davies (vocals and keyboards), they are distinguished for blending ...

's 1975 album of the same name.

Conservative response

Thatcher, the Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

, had been calling for the government to declare a state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

to deal with the strike during the first week of January. She also called for the immediate enactment of reforms that "Stepping Stones", and before it ''In Place of Strife'' had proposed: a ban on secondary picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pick ...

of third-party businesses not targeted directly by a strike, ending closed shop

A pre-entry closed shop (or simply closed shop) is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times to remain employed. This is different fr ...

contracts under which employers can only hire those already members of a union, requiring votes by secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential v ...

before strikes and in the elections of union officials, and securing no-strike agreements with public-sector unions that provided vital public services, such as fire, health care and utilities.sitting room

In Western architecture, a living room, also called a lounge room (Australian English), lounge ( British English), sitting room ( British English), or drawing room, is a room for relaxing and socializing in a residential house or apartment. ...

she spoke, she said, not as a politician but as a Briton. "Tonight I don't propose to use the time to make party political points", she told viewers. "I do not think you would want me to do so. The crisis that our country faces is too serious for that."

Labour response

In its own party political broadcast on 24 January, Labour ignored the situation entirely. Instead, a Manchester city councillor argued for increasing council housing in his city. Party members privately expressed great disappointment with Callaghan and his Cabinet that the government had not taken the opportunity to put its plan before the public. "How do you think that we the Party workers are going to go out and seek support from the public if this is the best you people can do at Transport House?" wrote one.

Public sector employees

Bitter winter weather returned after a week of milder temperatures on 22 January. Freezing rain began falling across England at noon; by midnight temperatures dropped further and it turned to snow, which continued falling into the next day. Once again roads were impassable in the south; in the north and at higher elevations areas that had not yet recovered from the storm three weeks prior were newly afflicted.General Strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

of 1926,National Union of Railwaymen

The National Union of Railwaymen was a trade union of railway workers in the United Kingdom. The largest railway workers' union in the country, it was influential in the national trade union movement.

History

The NUR was an industrial union ...

had already begun a series of 24-hour strikes, and the Royal College of Nursing

The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) is a registered trade union in the United Kingdom for those in the profession of nursing. It was founded in 1916, receiving its royal charter in 1928. Queen Elizabeth II was the patron until her death in 2022. ...

conference on 18 January decided to ask that the pay of nurses be increased to the same level in real terms as 1974, which would mean a 25 per cent average rise. The public sector unions labelled the date the "Day of Action", in which they held a 24-hour strike and marched to demand a £60 per week minimum wage. It would later be recalled as "Misery Monday" by the media.Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a ...

, Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated pop ...

and the west of Scotland) their action included refusing to attend 999 emergency calls. In these areas, the Army was drafted in to provide a skeleton service. Ancillary hospital staff also went on strike.[ On 30 January, the ]Secretary of State for Social Services The Secretary of State for Health and Social Services was a position in the UK cabinet, created on 1 November 1968 with responsibility for the Department of Health and Social Security. It continued until 25 July 1988 when Department of Health and t ...

David Ennals

David Hedley Ennals, Baron Ennals, (19 August 1922 – 17 June 1995) was a British Labour Party politician and campaigner for human rights. He served as Secretary of State for Social Services from 1976 to 1979.

Early life and military career

...

announced that 1,100 of 2,300 NHS hospitals were only treating emergencies, that practically no ambulance service was operating normally, and that the ancillary health service workers were deciding which cases merited treatment. The media reported with scorn that cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal bl ...

patients were being prevented from getting essential treatment.

Gravediggers' strike

At a strike committee meeting in the Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

area earlier in January, it was reported that although local binmen

A waste collector, also known as a garbageman, garbage collector, trashman (in the US), binman or (rarely) dustman (in the UK), is a person employed by a public or private enterprise to collect and dispose of municipal solid waste (refuse) and r ...

were supportive of the strike, they did not want to be the first to do so as they had always been. The committee then asked Ian Lowes, convener for the General and Municipal Workers' Union

The GMB is a general trade union in the United Kingdom which has more than 460,000 members. Its members work in nearly all industrial sectors, in retail, security, schools, distribution, the utilities, social care, the National Health Service (N ...

(GMWU) local, to have the gravediggers and crematorium

A crematorium or crematory is a venue for the cremation of the dead. Modern crematoria contain at least one cremator (also known as a crematory, retort or cremation chamber), a purpose-built furnace. In some countries a crematorium can also ...

workers he represented take the lead instead. He accepted, as long as the other unions followed; and the GMWU's national executive approved the strike.Larry Whitty

John Lawrence Whitty, Baron Whitty, (born 15 June 1943), known as Larry Whitty, is a British Labour Party politician.

Early life

Born in 1943, Whitty was educated at Latymer Upper School and graduated from St John's College, Cambridge, with a ...

, an executive official with the union, also agreed later that it had been a mistake to approve the strike.National Union of Public Employees

The National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) was a British trade union which existed between 1908 and 1993. It represented public sector workers in local government, the Health Service, universities, and water authorities.

History

The union ...

(NUPE) and the Confederation of Health Service Employees, both of which were growing more quickly, it was trying not to be what members of those unions called the 'scab union'.Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

and in Tameside

The Metropolitan Borough of Tameside is a metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester in England. It is named after the River Tame, which flows through the borough, and includes the towns of Ashton-under-Lyne, Audenshaw, Denton, Droylsden, Duk ...

near Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of City of Salford, Salford to ...

, was later frequently referred to by Conservative politicians. With 80 gravediggers being on strike, Liverpool City Council

Liverpool City Council is the governing body for the city of Liverpool in Merseyside, England. It consists of 90 councillors, three for each of the city's 30 wards.

The council is currently controlled by the Labour Party and is led by Mayor J ...

hired a factory in Speke to store the corpses until they could be buried. The Department of Environment noted that there were 150 bodies stored at the factory at one point, with 25 more added every day. The reports of unburied bodies caused concern with the public.burial at sea

Burial at sea is the disposal of human remains in the ocean, normally from a ship or boat. It is regularly performed by navies, and is done by private citizens in many countries.

Burial-at-sea services are conducted at many different locations ...

would be considered. Although his response was hypothetical, in the circumstances it caused great alarm. Other alternatives were considered, including allowing the bereaved to dig their own funeral's graves, deploying troops, and engaging private contractors to inter the bodies. The main concerns were said to be aesthetic because bodies could be safely stored in heat-sealed bags for up to six weeks.

Waste collectors

With many collectors having been on strike since 22 January, local authorities began to run out of space for storing waste and used local parks under their control. The Conservative controlled Westminster City Council

Westminster City Council is the local authority for the City of Westminster in Greater London, England. The city is divided into 20 wards, each electing three councillors. The council is currently composed of 31 Labour Party members and 23 Con ...

used Leicester Square

Leicester Square ( ) is a pedestrianised square in the West End of London, England. It was laid out in 1670 as Leicester Fields, which was named after the recently built Leicester House, itself named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester ...

in the heart of London's West End for piles of rubbish and, as the ''Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'' reported, this attracted rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include ''Neotoma'' ( pack rats), ''Bandicota'' (bandicoot ...

s and the available food led to an increase in their numbers. The media nicknamed the area Fester Square.London Borough of Camden

The London Borough of Camden () is a London borough in Inner London. Camden Town Hall, on Euston Road, lies north of Charing Cross. The borough was established on 1 April 1965 from the area of the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn, and S ...

, conceded the union demands in full (known as the "Camden surplus") and then saw an investigation by the District Auditor

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions o ...

, which eventually ruled it a breach of the fiduciary duty owed to the ratepayers (local taxpayers) of the area and therefore illegal. Camden Borough councillors, among them Ken Livingstone

Kenneth Robert Livingstone (born 17 June 1945) is an English politician who served as the Leader of the Greater London Council (GLC) from 1981 until the council was Local Government Act 1985, abolished in 1986, and as Mayor of London from the ...

, avoided surcharge. Livingstone was Leader of the Greater London Council

The Greater London Council (GLC) was the top-tier local government administrative body for Greater London from 1965 to 1986. It replaced the earlier London County Council (LCC) which had covered a much smaller area. The GLC was dissolved in 198 ...

at the time the decision not to impose a surcharge was made.

End of the strikes

By the end of January 90,000 Britons were receiving unemployment benefit. There were no more major storms, but temperatures remained bitterly cold. Many remote communities still had not quite recovered from the snowstorm at the beginning of the month.Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east of Wolverhampton and from Lichfield.

Walsall is t ...

was closed to traffic, and many other roads, even near London, had enforced temporary speed limits as low as . Plans to have the Army grit the roads were abandoned when NUPE official Barry Shuttleworth threatened an expanded strike of public employees in response.

Effect on general election

The strikes appeared to have a profound effect on voting intention. According to

The strikes appeared to have a profound effect on voting intention. According to Gallup

Gallup may refer to:

*Gallup, Inc., a firm founded by George Gallup, well known for its opinion poll

*Gallup (surname), a surname

*Gallup, New Mexico, a city in New Mexico, United States

**Gallup station, an Amtrak train in downtown Gallup, New Me ...

, Labour had a lead of 5 percentage points over the Conservatives in November 1978, which turned to a Conservative lead of 7.5 percentage points in January 1979, and of 20 percentage points in February. On 1 March, referendums on devolution to Scotland and Wales were held. That in Wales went strongly against devolution; that in Scotland produced a small majority in favour which did not reach the threshold set by Parliament of 40 per cent of that electorate. The government's decision not to press ahead with devolution immediately led the Scottish National Party

The Scottish National Party (SNP; sco, Scots National Pairty, gd, Pàrtaidh Nàiseanta na h-Alba ) is a Scottish nationalist and social democratic political party in Scotland. The SNP supports and campaigns for Scottish independence from ...

to withdraw support from the government and on 28 March in a motion of no confidence the government lost by one vote, precipitating a general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

.

Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

had already outlined her proposals for restricting trade union power in a party political broadcast on 17 January in the middle of the lorry drivers' strike. During the election campaign the Conservative Party made extensive use of the disruption caused during the strike. One broadcast on 23 April began with the Sun's headline "Crisis? What Crisis?" being shown and read out by an increasingly desperate voiceover interspersed with film footage of piles of rubbish, closed factories, picketed hospitals and locked graveyards. The scale of the Conservatives' victory in the general election has often been ascribed to the effect of the strikes, as well as their " Labour Isn't Working" campaign, and the party used film of the events of the winter in election campaigns for years to come.

Legacy

Following Thatcher's election win, she brought the post-war consensus to a halt and made drastic changes to trade union laws (most notably the regulation that unions had to hold a ballot among members before calling strikes) and as a result strikes were at their lowest level for 30 years by the time of the 1983 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1983.

Africa

* 1983 Cameroonian parliamentary election

* 1983 Equatorial Guinean legislative election

* 1983 Kenyan general election

* 1983 Malagasy parliamentary election

* 1983 Malawian general e ...

, which the Conservatives won by a landslide.Sex Pistols

The Sex Pistols were an English punk rock band formed in London in 1975. Although their initial career lasted just two and a half years, they were one of the most groundbreaking acts in the history of popular music. They were responsible for ...

, surviving members Steve Jones Steve or Steven Jones may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Steve Jones (English presenter) (born 1945), English musician, disk jockey, television presenter, and voice-over artist

*Steve Jones (musician) (born 1955), English rock and roll guita ...

and John Lydon recall 1975, around the time of the band's founding, for "a garbage strike that went on for years and years and there was trash piled ten-foot high". One of López's own students in her classes at the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The university owns and operates majo ...

identified the Winter of Discontent with the three-day week, which had actually been implemented during the 1974 miner's strike. She wrote: "The embeddedness of a memory infused with a mix of errors, political fact and evocative images is particularly interesting in understanding the Winter of Discontent because it intimates the broader historical significance of this series of events."

Within the Labour Party

The Winter of Discontent also had effects within the Labour Party. Callaghan was succeeded as leader by the more left-wing Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the '' Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 ...

, who did not succeed in unifying the party. In 1981, still believing the party to have been too firmly controlled by the unions, William Rodgers, the former transport minister who had tried to mitigate the effect of the hauliers' strike, left with three dozen other disaffected Labourites to form the more centrist Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

(SDP), a decision he recalls reaching with some difficulty. Similarly disillusioned, especially after a GMWU official assured him "we'll call the shots" after the winter ended, Tom McNally, Callaghan's advisor who had recommended the news conference that produced ''The Sun''s "Crisis? What Crisis?" headline, left Labour for the SDP.Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

positions of ''The Militant

''The Militant'' is an international socialist newsweekly connected to the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and the Pathfinder Press. It is published in the United States and distributed in other countries such as Canada, the United Kingdom ...

'' newspaper distributed to strikers, and soon formally joined the local branch of the Militant Tendency, leaving them six years later when the Liverpool City Council, controlled by Militant, followed local governments across Britain in contracting out work normally done by government workers.