War of the Third Coalition)

* it is known as the Austrian campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Autriche de 1805) or the German campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Allemagne de 1805) was a European conflict spanning 1805 to 1806. During the war,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and

its client states under

Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

opposed an alliance, the Third Coalition, which was made up of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

,

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

,

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, and

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

.

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

remained neutral during the war.

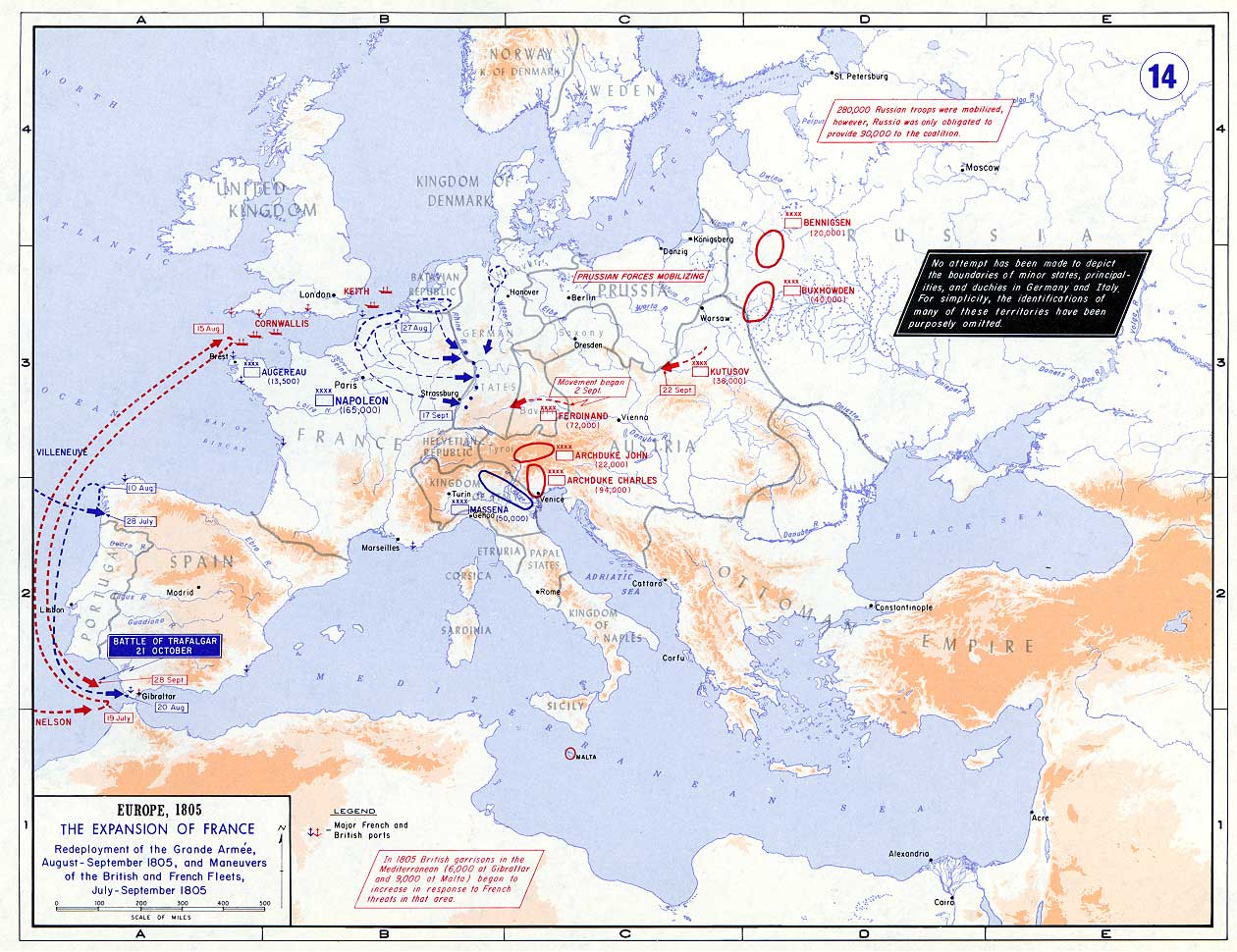

Britain had already been at war with France following the breakdown of the

Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it se ...

and remained the only country still at war with France after the

Treaty of Pressburg. From 1803 to 1805, Britain stood under constant threat of a

French invasion. The

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, however, secured mastery of the seas and decisively destroyed a Franco-Spanish fleet at the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

in October 1805.

The Third Coalition itself came to full fruition in 1804–05 as Napoleon's actions in Italy and Germany (notably the arrest and execution of the

Duc d'Enghien

Duke of Enghien (french: Duc d'Enghien, pronounced with a silent ''i'') was a noble title pertaining to the House of Condé. It was only associated with the town of Enghien for a short time.

Dukes of Enghien – first creation (1566–1569)

The ...

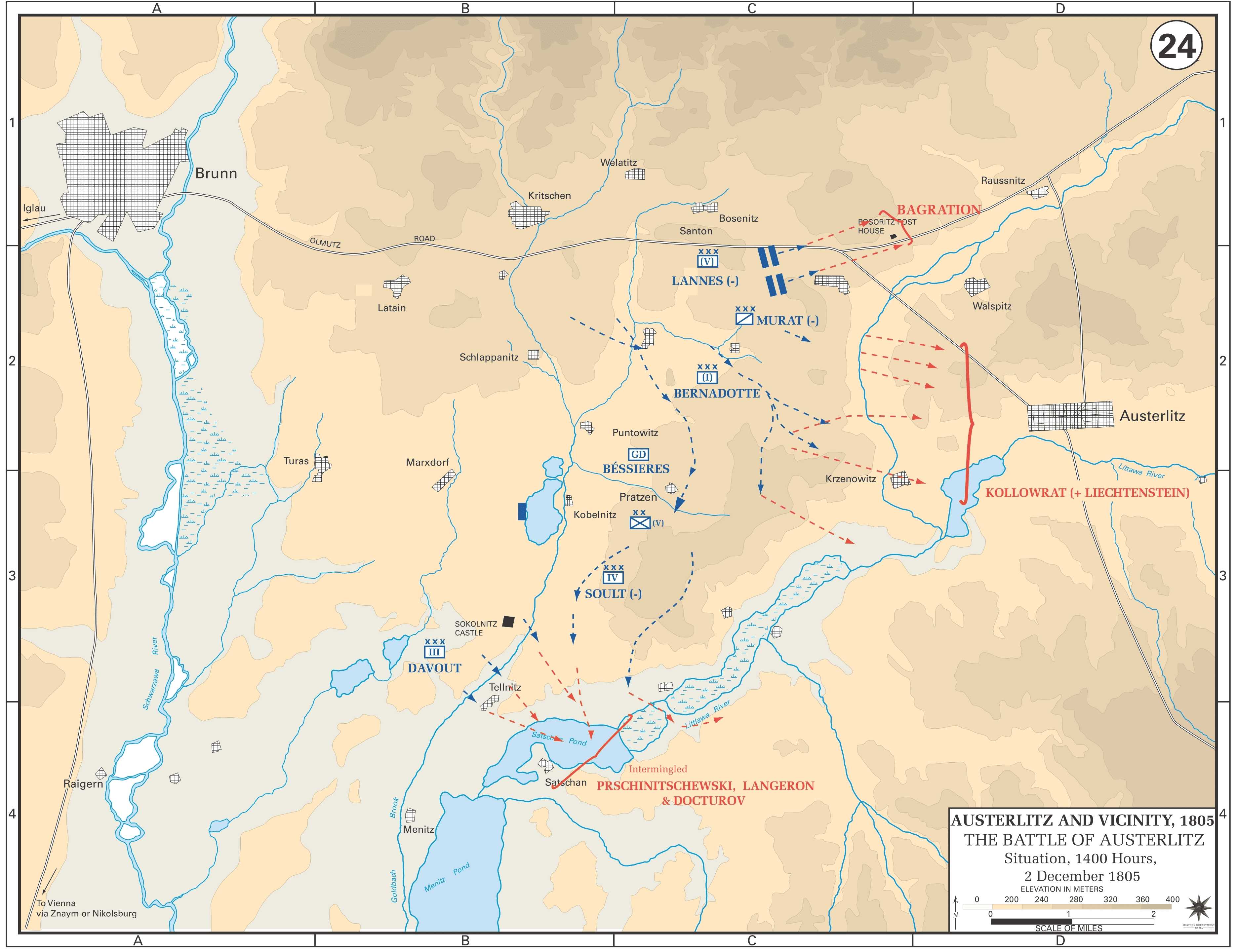

) spurred Austria and Russia into joining Britain against France. The war would be determined on the continent, and the major land operations that sealed the swift French victory involved the

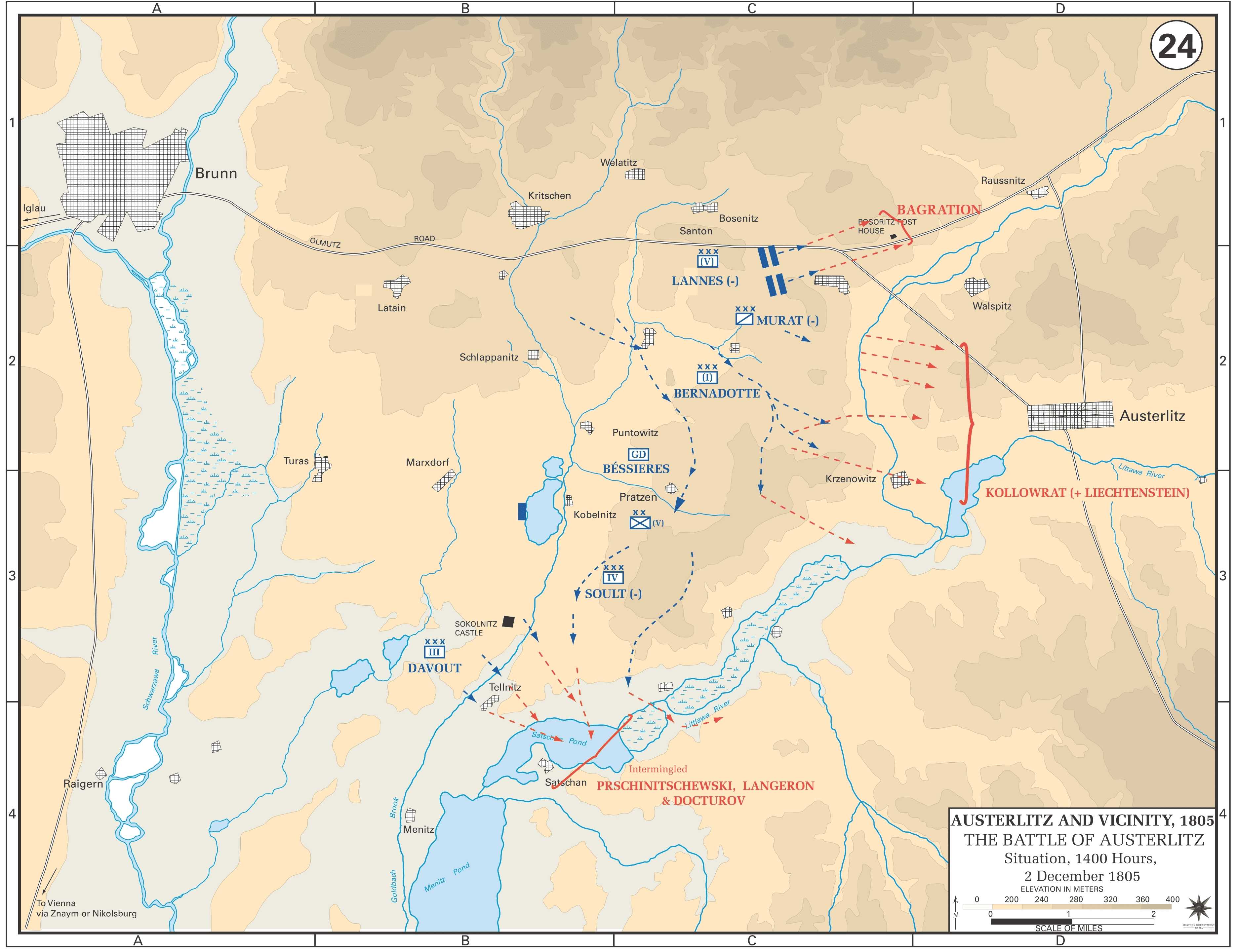

Ulm Campaign, a large wheeling manoeuvre by the lasting from late August to mid-October 1805 that captured an entire Austrian army, and the decisive French victory over a combined Austro-Russian force under

Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first King of Congress Poland from 1815, and the Grand Duke of Finland from 1809 to his death. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg.

The son of ...

at the

Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

in early December. Austerlitz effectively brought the Third Coalition to an end, although later there was a small side campaign against Naples, which also resulted in a decisive French victory at the

Battle of Campo Tenese

The Battle of Campo Tenese (9 March 1806) saw two divisions of the First French Empire, Imperial French Army of Naples led by Jean Reynier attack the left wing of the Royal Neapolitan Army under Roger de Damas. Though the defenders were protect ...

.

On 26 December 1805, Austria and France signed the Treaty of Pressburg, which took Austria out of both the war and the Coalition, while it reinforced the earlier treaties of

Campo Formio

Campoformido ( fur, Cjampfuarmit) is a town and ''comune'' in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, north-eastern Italy, with a population of 7743 (December 2019). It is notable for the Treaty of Campo Formio.

History

Campoformido is a village not far from Udi ...

and of

Lunéville

Lunéville ( ; German, obsolete: ''Lünstadt'' ) is a commune in the northeastern French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

It is a subprefecture of the department and lies on the river Meurthe at its confluence with the Vezouze.

History

Lun ...

between the two powers. The treaty confirmed the Austrian cession of lands in Italy to France and in Germany to Napoleon's German allies, imposed an indemnity of 40 million francs on the defeated Habsburgs, and allowed the defeated Russian troops free passage, with their arms and equipment, through hostile territories and back to their home soil. Victory at Austerlitz also prompted Napoleon to create the

Confederation of the Rhine

The Confederated States of the Rhine, simply known as the Confederation of the Rhine, also known as Napoleonic Germany, was a confederation of German client states established at the behest of Napoleon some months after he defeated Austria an ...

, a collection of German client states that pledged themselves to raise an army of 63,000 men. As a direct consequence of those events, the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

ceased to exist when, in 1806,

Francis II abdicated the Imperial throne, becoming Francis I, Emperor of Austria. Those achievements, however, did not establish a lasting peace on the continent. Austerlitz had driven neither Russia nor Britain, whose fleet protected Sicily from a French invasion, to cease fighting. Meanwhile, Prussian worries about the growing French influence in

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

sparked the

War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, s ...

in 1806.

Periodisation

Historians differ on when the War of the Third Coalition began and when it ended. From the British perspective, the war started when Britain declared war on France on 18 May 1803, but it was still on its own. It was not until December 1804 when Sweden entered into an alliance with the United Kingdom, not until 11 April 1805 when Russia joined the alliance, not until 16 July when Britain and Russia ratified their treaty of alliance, and only thereafter Austria (9 August) and Naples–Sicily (11 September) completed the fully-fledged coalition.

Meanwhile,

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

sided with France on 25 August, and

Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Würt ...

joined Napoleon on 5 September. No major hostilities between France and any member of the coalition other than Britain (

Trafalgar campaign March–November 1805) occurred until the

Ulm Campaign (25 September – 20 October 1805). This was in part because

Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom

Napoleon's planned invasion of the United Kingdom at the start of the War of the Third Coalition, although never carried out, was a major influence on British naval strategy and the fortification of the coast of southeast England. French attempt ...

was not called off until 27 August 1805, when he decided to use his invasion force

camped at Boulogne against Austria instead.

Likewise, no major battles occurred after the Battle of Austerlitz and the signing of the

Peace of Pressburg on 26 December 1805, which forced Austria to leave the Third Coalition and cease hostilities against France. Some historians conclude that Austria's departure "shattered the fragile Third Coalition"

and "ended the War of the Third Coalition".

This narrative leaves out the subsequent

French invasion of Naples (February–July 1806), which the

occupying Anglo-Russian troops hastily evacuated and the remaining Neapolitan forces relatively quickly surrendered. Other scholars argue the southern Italian campaign should be included into the

War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

, and criticise ignoring the Mediterranean front by only focusing on land battles in Central Europe and the Trafalgar campaign.

Prelude

Europe had been embroiled in the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

since 1792. After five years of war, the

French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

subdued the armies of the

First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

in 1797. A

Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

was formed in 1798, but this too was defeated by 1801, leaving

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

the only opponent of the new

French Consulate

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

.

From Amiens to the Third Coalition

In March 1802, France and Britain agreed to cease hostilities under the

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on perio ...

. For the first time in ten years, all of Europe was at peace. However, many problems persisted between the two sides making the implementation of the treaty increasingly difficult. Napoleon was angry that British troops had not evacuated the island of

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

.

Chandler

Chandler or The Chandler may refer to:

* Chandler (occupation), originally head of the medieval household office responsible for candles, now a person who makes or sells candles

* Ship chandler, a dealer in supplies or equipment for ships

Arts ...

p. 304. The tension only worsened when Napoleon sent an expeditionary force to attempt to

re-establish control over Haiti.

[Chandler p. 320.] Prolonged intransigence on these issues led Britain to declare war on France on 18 May 1803.

Napoleon's expeditionary army was destroyed by disease in Haiti and subsequently swayed the First Consul to abandon his plans to rebuild France's New World empire. Without sufficient revenues from sugar colonies in the Caribbean, the vast

territory of Louisiana

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

in North America had little value to him. Though Spain had not yet completed the transfer of Louisiana to France per the

Third Treaty of San Ildefonso

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso was a secret agreement signed on 1 October 1800 between the Spanish Empire and the French Republic by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange its North American colony of Louisiana for territories in Tuscany. ...

, a war between France and Britain was imminent. Out of anger against Spain and having the unique opportunity to sell something that was useless and not truly his yet, Napoleon decided to sell the entire territory to the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

for a sum total of 68 million francs ($15 million). The

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

Treaty was signed on 30 April 1803.

Despite issuing orders that the over 60 million francs were to be spent on the construction of five new canals in France, Bonaparte spent the whole amount on his

planned invasion of England.

The nascent Third Coalition came into being in December 1804 when, in exchange for payment, an Anglo-Swedish agreement was signed allowing the British to use

Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

as a military base against France (explicitly, the nearby French-occupied

Electorate of Hanover

The Electorate of Hanover (german: Kurfürstentum Hannover or simply ''Kurhannover'') was an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, located in northwestern Germany and taking its name from the capital city of Hanover. It was formally known as ...

, the homeland of the British monarch). The Swedish government had broken diplomatic ties with France in early 1804 after the arrest and execution of

Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien

Louis Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Enghien (''duc d'Enghien'' pronounced ) (Louis Antoine Henri; 2 August 1772 – 21 March 1804) was a member of the House of Bourbon of France. More famous for his death than for his life, he was executed on charg ...

, a

royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

émigré who had been implicated (on dubious evidence) in an assassination plot against First Consul Bonaparte. The execution of Enghien shocked the aristocrats of Europe, who still remembered the bloodletting of the Revolution and thus lost whatever conditional respect they may have entertained for Napoleon.

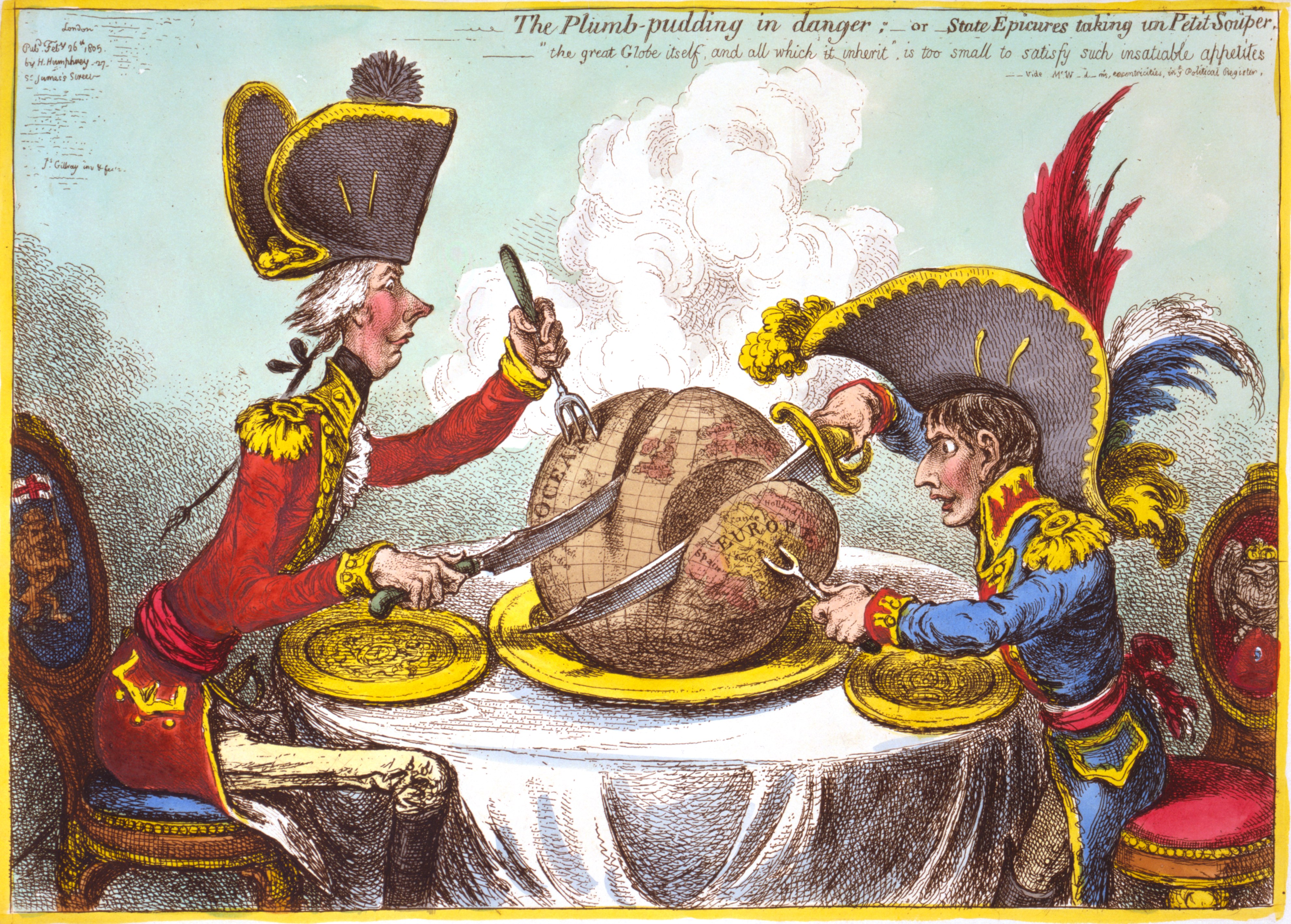

Fanning the flames of the outcry resulting from d'Enghien's death and the growing fear over increasing French power, British Prime Minister

William Pitt spent 1804 and 1805 in a flurry of diplomatic activity geared towards forming a new coalition against France. Pitt scored a significant coup by securing a burgeoning rival as an ally. The

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

was dominated by Russia, something Britain had been uncomfortable with since the area provided valuable commodities like timber, tar, and hemp, crucial supplies to its

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

.

[Chandler p. 328.]

Additionally, Britain had supported the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in resisting Russian incursions towards the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. Mutual suspicion between the British and the Russians eased in the face of several French political mistakes, and on 11 April 1805 the two signed a treaty of alliance in

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.

[Chandler p. 328.] The stated goal of the Anglo-Russian alliance was to reduce France to its 1792 borders. Austria, Sweden, and Naples would eventually join this alliance, whilst Prussia again remained neutral.

Meantime, the lull in participating in active military campaigning from 1801 to 1804 permitted Napoleon to consolidate his political power base in France. 1802 saw him proclaimed Consul for Life, his reward for having made peace with Britain, albeit briefly, as well as the establishment of a meritorious order, the

Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

. Then, in May 1804, Napoleon was proclaimed Napoleon, Emperor of the French, and crowned at

Notre Dame on 2 December 1804. He created eighteen ''

Marshals of the Empire'' from among his top generals, securing the allegiance of the army. Napoleon added the crown of

(Northern) Italy to his mantle in May 1805, thereby placing a traditional Austrian sphere of influence under his rule (eventually through a viceroy, his stepson

Eugène de Beauharnais

Eugène Rose de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg (; 3 September 1781 – 21 February 1824) was a French nobleman, statesman, and military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

Through the second marr ...

). Keen on revenge and having been defeated twice in recent memory by France, Austria joined the Third Coalition a few months later.

at Boulogne

Prior to the formation of the Third Coalition, Napoleon had assembled the ''Army of England'', an invasion force meant to strike at England, from around six camps at

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

in Northern France. Although they never set foot on British soil, Napoleon's troops received careful and invaluable training for any possible military operation. Boredom among the troops occasionally set in, but Napoleon paid many visits and conducted lavish parades in order to boost the morale of the soldiers.

[Chandler p. 323.]

The men at Boulogne formed the core for what Napoleon would later call ("The Great Army"). At the start, this French army had about 200,000 men organized into seven

corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

, each capable of independent action or in concert with other corps. Corps were large combined arms field units typically containing 2–4 infantry divisions, a cavalry division, and about 36 to 40

cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

.

[Chandler p. 332.]

On top of these forces, Napoleon created a

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

reserve of 22,000 organized into two

cuirassier

Cuirassiers (; ) were cavalry equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as men-at-arms and demi-lancers, discarding their lances and adoptin ...

divisions, four mounted

dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat w ...

divisions, and two divisions of dismounted dragoons and light cavalry, all supported by 24

artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

pieces.

By 1805, the had grown to a force of 350,000,

[Chandler p. 333.] was well equipped, adequately trained, and possessed a skilled officer class.

Russian and Austrian armies

The

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

in 1805 had many characteristics of

ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

military organization: there was no permanent formation above the regimental level, senior officers were largely recruited from aristocratic circles (including foreigners), and the Russian soldier, in line with 18th-century practice, was regularly beaten and punished to instill discipline. Furthermore, many lower-level officers were poorly trained and had difficulty getting their men to perform the sometimes complex manoeuvres required in a battle. Nevertheless, the Russians did have a fine artillery arm manned by soldiers who regularly fought hard to prevent their pieces from falling into enemy hands.

[ Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 33.]

Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

, brother of the Austrian Emperor, had started to reform the

Austrian army

The Austrian Armed Forces (german: Bundesheer, lit=Federal Army) are the combined military forces of the Republic of Austria.

The military consists of 22,050 active-duty personnel and 125,600 reservists. The military budget is 0.74% of natio ...

in 1801 by taking away power from the

Hofkriegsrat

The ''Hofkriegsrat'' (or Aulic War Council, sometimes Imperial War Council) established in 1556 was the central military administrative authority of the Habsburg monarchy until 1848 and the predecessor of the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War. Th ...

, the military-political council responsible for decision-making in the Austrian armed forces.

[Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 31.] Charles was Austria's best field commander,

[ Uffindell p. 155.] but he was unpopular with the imperial court and lost much influence when, against his advice, Austria decided to go to war with France.

Karl Mack

Karl Freiherr Mack von Leiberich (25 August 1752 – 22 December 1828) was an Austrian soldier. He is best remembered as the commander of the Austrian forces that capitulated to Napoleon's '' Grande Armée'' in the Battle of Ulm in 1805.

Early ...

became the new main commander in Austria's army, instituting reforms on the infantry on the eve of war that called for a regiment to be composed of four

battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

s of four

companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

rather than the older three battalions of six companies. The sudden change came with no corresponding officer training, and as a result, these new units were not led as well as they could have been.

[Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 32.] Austrian cavalry forces were regarded as the best in Europe, but the detachment of many cavalry units to various infantry formations precluded the hitting power of their massed French counterparts.

Finally, a significant divergence between these two nominal allies is often cited as a cause for disastrous consequences. The Russians were still using the old style

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

, while the Austrians had adopted the new style

Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

, and by 1805 a difference of 12 days existed between the two systems. Confusion is purported to have ensued from the differing timetables regarding when the Allied forces should combine, leading to an inevitable breakdown in mutual coordination. However, this tale is not supported in a contemporary account from a major-general of the Austrian army, who tells of a joint advance of the Russian and Austrian forces (in which he himself took part) five days before the Battle of Austerlitz,

and it is explicitly rejected in Goetz's recent book-length study of the battle.

Ulm campaign

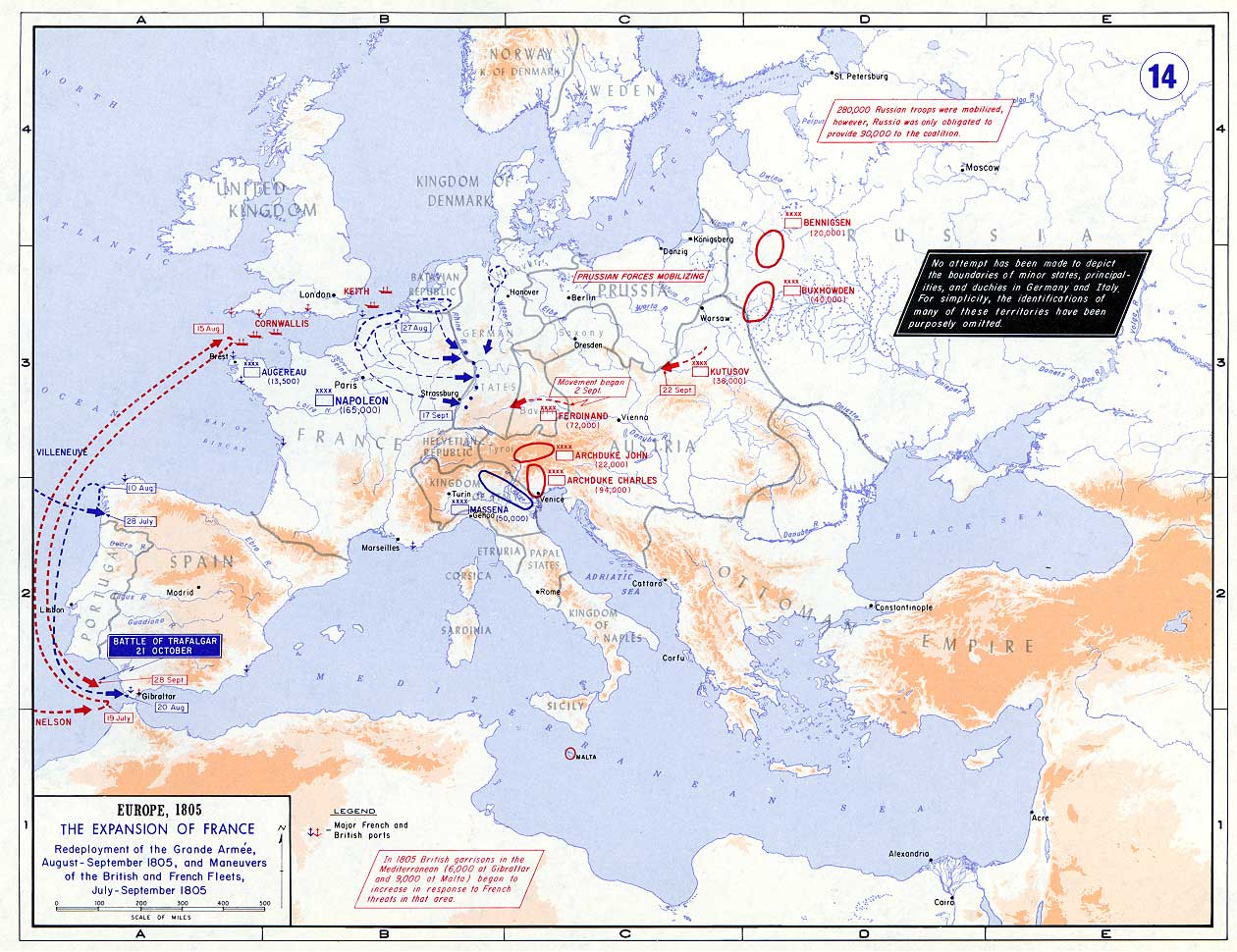

In August 1805, Napoleon,

Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First and the Second French Empires.

Details

A title and office used by the House of Bonaparte starting when Napoleon was procl ...

since May of the previous year, turned his army's sights from the

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

to the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

in order to deal with the new Austrian and Russian threats. The War of the Third Coalition began with the Ulm Campaign, a series of French and

Bavarian military manoeuvres and battles designed to outflank an Austrian army under General Mack.

Austrian plans and preparations

General Mack thought that Austrian security relied on sealing off the gaps through the mountainous

Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is t ...

area in Southern Germany that had witnessed much fighting during the campaigns of the French Revolutionary Wars. Mack believed that there would be no action in Central Germany. Mack decided to make the city of

Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

the centrepiece of his defensive strategy, which called for containment of the French until the Russians under

Mikhail Kutuzov

Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov ( rus, Князь Михаи́л Илларио́нович Голени́щев-Куту́зов, Knyaz' Mikhaíl Illariónovich Goleníshchev-Kutúzov; german: Mikhail Illarion Golenishchev-Kut ...

could arrive and alter the odds against Napoleon. Ulm was protected by the heavily fortified Michelsberg heights, giving Mack the impression that the city was virtually impregnable from outside attack.

[Fisher & Fremont-Barnes p. 36.]

Fatally, the

Aulic Council

The Aulic Council ( la, Consilium Aulicum, german: Reichshofrat, literally meaning Court Council of the Empire) was one of the two supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire, the other being the Imperial Chamber Court. It had not only concurrent juris ...

decided to make Northern Italy the main theatre of operations for the Austrian army.

Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

was assigned 95,000 troops and directed to cross the

Adige

The Adige (; german: Etsch ; vec, Àdexe ; rm, Adisch ; lld, Adesc; la, Athesis; grc, Ἄθεσις, Áthesis, or , ''Átagis'') is the second-longest river in Italy, after the Po. It rises near the Reschen Pass in the Vinschgau in the prov ...

river with

Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

,

Peschiera, and

Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

as the initial objectives.

[Chandler p. 382.] Archduke John

Archduke John of Austria (german: Erzherzog Johann Baptist Joseph Fabian Sebastian von Österreich; 20 January 1782 – 11 May 1859), a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, was an Austrian field marshal and imperial regent (''Reichsverwese ...

was given 23,000 troops and commanded to secure

Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

while serving as a link between his brother, Charles, and his cousin, Archduke

Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

; the latter's force of 72,000, which was to invade Bavaria and hold the defensive line at Ulm, was effectively controlled by Mack.

The Austrians also detached individual corps to serve with the Swedish in

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and the British in

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, though these were designed to obfuscate the French and divert their resources.

French plans and preparations

In both the campaigns of 1796 and 1800, Napoleon had envisaged the Danube theatre as the central focus of French efforts, but in both instances, the Italian theatre became the most important. The Aulic Council thought Napoleon would strike in Italy again. Napoleon had other intentions: 210,000 French troops would be launched eastwards from the camps of Boulogne and would envelop General Mack's exposed Austrian army if it kept marching towards the

Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is t ...

.

[Chandler p. 384.]

Meanwhile,

Marshal Murat would conduct cavalry screens across the Black Forest to fool the Austrians into thinking that the French were advancing on a direct west–east axis. The main attack in Germany would be supported by French assaults in other theatres: Marshal

Masséna would confront Archduke Charles in Italy with 50,000 men, Marshal

St. Cyr would march to Naples with 20,000 men, and Marshal

Brune would patrol Boulogne with 30,000 troops against a possible British invasion.

[Chandler p. 385.]

Marshal

Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

and General

Bertrand

Bertrand may refer to:

Places

* Bertrand, Missouri, US

* Bertrand, Nebraska, US

* Bertrand, New Brunswick, Canada

* Bertrand Township, Michigan, US

* Bertrand, Michigan

* Bertrand, Virginia, US

* Bertrand Creek, state of Washington

* Saint-Bert ...

conducted reconnaissance between the area bordering the Tyrol and the

Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

as General

Savary, chief of the planning staff, drew up detailed road surveys of the areas between the Rhine and the Danube.

The left-wing of the would move from

Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

and

Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

to fall on Württemberg; the right and centre, troops from the Channel coast, would concentrate along the

Middle Rhine

Between Bingen and Bonn, Germany, the river Rhine flows as the Middle Rhine (german: Mittelrhein) through the Rhine Gorge, a formation created by erosion, which happened at about the same rate as an uplift in the region, leaving the river at ...

around cities like

Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

and

Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

.

While Murat was making demonstrations across the Black Forest, other French forces would then invade the German heartland and swing towards the southeast by capturing

Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

, a move that was supposed to isolate Mack and interrupt the Austrian lines of communication.

The French invasion

On 22 September, Mack decided to hold the

Iller

The Iller (; ancient name Ilargus) is a river of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg in Germany. It is a right tributary of the Danube, long.

It is formed at the confluence of the rivers Breitach, Stillach and Trettach near Oberstdorf in the Allgäu ...

line anchored on Ulm. In the last three days of September, the French began the furious marches that would find them at the Austrian rear. Mack believed that the French would not violate Prussian territory, but when he heard that

Bernadotte's I Corps had marched through Prussian

Ansbach

Ansbach (; ; East Franconian: ''Anschba'') is a city in the German state of Bavaria. It is the capital of the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Ansbach is southwest of Nuremberg and north of Munich, on the river Fränkische Rezat, a ...

, he made the critical decision to stay and defend Ulm rather than retreat to the south, which would have offered a reasonable opportunity at saving the bulk of his forces.

[ Kagan p. 389.] Napoleon had little accurate information about Mack's intentions or manoeuvres. He knew that

Kienmayer

Michael von Kienmayer (17 January 1756 – 28 October 1828) was an Austrian general. Kienmayer joined the army of the Habsburg monarchy and fought against the Kingdom of Prussia and Ottoman Turkey. During the French Revolutionary Wars, he continued ...

's Corps was sent to

Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an independent city on the Danube in Upper Bavaria with 139,553 inhabitants (as of June 30, 2022). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan area. Ingolstadt is the second largest city in Upper Bav ...

east of the French positions, but his agents greatly exaggerated its size.

[Kagan p. 393.]

On 5 October, Napoleon ordered Marshal

Ney

The ''ney'' ( fa, Ney/نی, ar, Al-Nāy/الناي), is an end-blown flute that figures prominently in Persian music and Arabic music. In some of these musical traditions, it is the only wind instrument used. The ney has been played continually ...

to join Marshals

Lannes,

Soult

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, 1st Duke of Dalmatia, (; 29 March 1769 – 26 November 1851) was a French general and statesman, named Marshal of the Empire in 1804 and often called Marshal Soult. Soult was one of only six officers in Frenc ...

, and Murat in concentrating and crossing the Danube at

Donauwörth

Donauwörth () is a town and the capital of the Donau-Ries district in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is said to have been founded by two fishermen where the rivers Danube (Donau) and Wörnitz meet. The city is part of the scenic route called "Roman ...

.

[Kagan p. 395.] The French encirclement was not deep enough to prevent Kienmayer's escape: the French corps did not all arrive at the same place – they instead deployed on a long west–east axis – and the early arrival of Soult and

Davout

Louis-Nicolas d'Avout (10 May 1770 – 1 June 1823), better known as Davout, 1st Duke of Auerstaedt, 1st Prince of Eckmühl, was a French military commander and Marshal of the Empire who served during both the French Revolutionary Wars and th ...

at Donauwörth incited Kienmayer to exercise caution and evasion.

Napoleon gradually became more convinced that the Austrians were massed at Ulm and ordered sizeable portions of the French army to concentrate around Donauwörth; on 6 October, three French infantry and cavalry corps headed to Donauwörth to seal off Mack's escape route.

[Kagan p. 397.]

Battle of Wertingen

Realizing the danger of his position, Mack decided to go on the offensive. On 8 October, he commanded the army to concentrate around

Günzburg

Günzburg (; Swabian German, Swabian: ''Genzburg'') is a town in Bavaria, Germany. It is a ''Große Kreisstadt'' and the capital of the Swabian Günzburg (district), district Günzburg. This district was constituted in 1972 by combining the city ...

and hoped to strike at Napoleon's lines of communication. Mack instructed Kienmayer to draw Napoleon further east towards

Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

and Augsburg. Napoleon did not seriously consider the possibility that Mack would cross the Danube and move away from his central base, but he did realize that seizing the bridges at Günzburg would yield a large strategic advantage. To accomplish this objective, Napoleon sent Ney's Corps to Günzburg, completely unaware that the bulk of the Austrian army was heading to the same destination. On 8 October, however, the campaign witnessed its first serious battle at

Wertingen

Wertingen () is a town in the district of Dillingen in Bavaria, Germany. It is located along the river Zusam in 13 km east of Dillingen, and 28 km northwest of Augsburg. The city is the seat of the municipal association Wertingen.

S ...

between Auffenburg's troops and those of Murat and Lannes.

For reasons not entirely clear, Mack ordered Auffenburg on 7 October to take his division of 5,000 infantry and 400 cavalry from Günzburg to Wertingen in preparation for the main Austrian advance out of Ulm. Uncertain of what to do and having little hope for reinforcements, Auffenburg was in a dangerous position. The first French forces to arrive were Murat's cavalry divisions – Klein's 1st Dragoons, Beaumont 3rd Dragoons, and Nansouty's

cuirassier

Cuirassiers (; ) were cavalry equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as men-at-arms and demi-lancers, discarding their lances and adoptin ...

s. They began to assault the Austrian positions and were soon joined by

Oudinot

Nicolas Charles Oudinot, 1st Count Oudinot, 1st Duke of Reggio (25 April 1767 in Bar-le-Duc – 13 September 1847 in Paris), was a Marshal of the Empire. He is known to have been wounded 34 times in battle, being hit by artillery shells, sabers, ...

's grenadiers, who were hoping to outflank the Austrians from the north and west. Auffenburg attempted a retreat to the southwest, but he was not quick enough: the Austrians were decimated, losing nearly their entire force, 1,000 to 2,000 of which were prisoners.

[Kagan p. 404.] The

Battle of Wertingen

In the Battle of Wertingen (8 October 1805) Imperial French forces led by Marshals Joachim Murat and Jean Lannes attacked a small Austrian corps commanded by Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Xaver von Auffenberg. This action, the first battle of ...

had been an easy French victory.

The actions at Wertingen convinced Mack to operate on the left bank of the Danube instead of making a direct eastwards retreat on the right bank. This would require the Austrian army to cross at Günzburg. On 8 October, Ney was operating under Marshal

Berthier's directions that called for a direct attack on Ulm the following day. Ney sent in Malher's 3rd Division to capture the Günzburg bridges over the Danube. A column of this division ran into some Tyrolean

jägers and captured 200 of them, including their commander General

d'Aspré, along with two cannons.

[Kagan p. 408.]

The Austrians noticed these developments and reinforced their positions around Günzburg with three infantry battalions and 20 cannons.

Malher's division conducted several heroic attacks against the Austrian positions, but all failed. Mack then sent in

Ignác Gyulay

Count Ignác Gyulay de Marosnémeti et Nádaska, Ignácz Gyulay, Ignaz Gyulai (11 September 1763 – 11 November 1831) was a Hungarian military officer, joined the army of Habsburg monarchy, fought against Ottoman Turkey, and became a general ...

with seven infantry battalions and fourteen cavalry squadrons to repair the destroyed bridges, but this force was charged and swept away by the delayed French 59th Infantry Regiment.

[Kagan p. 409.]

Fierce fighting ensued and the French finally managed to establish a foothold on the right bank of the Danube. While the

Battle of Günzburg

The Battle of Günzburg on 9 October 1805 saw General of Division Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher's French division attempt to seize a crossing over the Danube River at Günzburg in the face of a Habsburg Austrian army led by Feldmarschall-Leutnan ...

was being fought, Ney sent General Loison's 2nd Division to capture the Danube bridges at

Elchingen

Elchingen is a municipality about 7 km east of Ulm–Neu-Ulm in the district of Neu-Ulm in Bavaria, Germany.

Municipality parts:

* Thalfingen: 4 211 residents, 8.83 km²

* Oberelchingen: 3 024 residents, 7.31 km²

* ...

, which were lightly defended by the Austrians. Having lost most of the Danube bridges, Mack marched his army back to Ulm. By 10 October, Ney's corps had made significant progress: Malher's division had crossed to the right bank, Loison's division held Elchingen, and

Dupont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

's division was heading towards Ulm.

Haslach-Jungingen and Elchingen

The demoralized Austrian army arrived at Ulm in the early hours of 10 October. Mack was deliberating about a course of action to pursue and the Austrian army remained inactive at Ulm until the 11th. Meanwhile, Napoleon was operating under flawed assumptions: he believed the Austrians were moving to the east or southeast and that Ulm was lightly guarded. Ney sensed this misapprehension and wrote to Berthier that Ulm was, in fact, more heavily defended than the French originally thought. During this time, the Russian threat to the east began to preoccupy Napoleon so much that Murat was given command of the right wing of the army, consisting of Ney's and Lannes's corps. The French were separated in two massive rings at this point: the forces of Ney, Lannes and Murat to the west were containing Mack, while those of Soult, Davout, Bernadotte and

Marmont

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont (20 July 1774 – 22 March 1852) was a French general and nobleman who rose to the rank of Marshal of the Empire and was awarded the title (french: duc de Raguse). In the Peninsular War Marmont succeede ...

to the east were charged with guarding against any possible Russian and Austrian incursions. On 11 October, Ney made a renewed push on Ulm; the 2nd and 3rd divisions were to march to the city along the right bank of the Danube while Dupont's division, supported by one dragoons division, was to march directly for Ulm and seize the entire city. The orders were hopeless because Ney still did not know that the entire Austrian army was stationed at Ulm.

The 32nd Infantry Regiment in Dupont's division marched from

Haslach towards Ulm and ran into four Austrian regiments holding Bolfingen. The 32nd carried out several ferocious attacks, but the Austrians held firm and repulsed every single one of them. The Austrians flooded the battle with more cavalry and infantry regiments to

Jungingen

Jungingen is a municipality in the Zollernalbkreis, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located nearby the castle Burg Hohenzollern, about 5 km east of Hechingen.

In former times, the city was located in ''Hohenzollern-Hechingen'', a principa ...

hoping to score a knockout blow against Ney's corps by enveloping Dupont's force. Dupont sensed what was happening and preempted the Austrians by launching a surprise attack on Jungingen that captured at least 1,000 prisoners. Renewed Austrian attacks drove these forces back to Haslach, which the French managed to hold. Dupont was eventually forced to fall back on Albeck, where he joined

d'Hilliers's troops. The effects of the

Battle of Haslach-Jungingen

The Battle of Haslach-Jungingen, also known as the Battle of Albeck, fought on 11 October 1805 at Ulm-Jungingen north of Ulm at the Danube between French and Austrian forces, was part of the War of the Third Coalition, which was a part of the ...

on Napoleon's plans are not fully clear, but the Emperor may have finally ascertained that the majority of the Austrian army was concentrated at Ulm.

[Kagan p. 417.] Accordingly, Napoleon sent the corps of Soult and Marmont towards the

Iller

The Iller (; ancient name Ilargus) is a river of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg in Germany. It is a right tributary of the Danube, long.

It is formed at the confluence of the rivers Breitach, Stillach and Trettach near Oberstdorf in the Allgäu ...

, meaning he now had four infantry and one cavalry corps to deal with Mack; Davout, Bernadotte, and the Bavarians were still guarding the region around Munich.

Napoleon did not intend to fight a battle across rivers and ordered his marshals to capture the important bridges around Ulm. He also began shifting his forces to the north of Ulm because he expected a battle in that region rather than an encirclement of the city itself.

[Kagan p. 420.] These dispositions and actions would lead to a confrontation at Elchingen on the 14th as Ney's forces advanced on Albeck.

At this point in the campaign, the Austrian command staff was in full confusion. Ferdinand began to openly oppose Mack's command style and decisions, charging that the latter spent his days writing contradictory orders that left the Austrian army marching back and forth.

[Kagan p. 421.] On 13 October, Mack sent two columns out of Ulm in preparation for a breakout to the north: one under General

Johann Sigismund Riesch

Johann Sigismund Graf von Riesch (2 August 1750 – 2 November 1821) joined the army of Habsburg Austria as a cavalry officer and, during his career, fought against the Kingdom of Prussia, Ottoman Turkey, Revolutionary France, and Napoleon's ...

headed towards Elchingen to secure the bridge there and the other under

Franz von Werneck

Franz Freiherr von Werneck (13 October 1748 – 17 January 1806), enlisted in the army of Habsburg Austria and fought in the Austro-Turkish War, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. He enjoyed a distinguished career until 1797 ...

went north with most of the heavy artillery.

[Fisher & Fremont-Barnes pp. 39–40.] Ney hurried his corps forward to reestablish contact with Dupont. Ney led his troops to the south of Elchingen on the right bank of the Danube and began the attack. The field to the side was a partially wooded flood plain, rising steeply to the hill town of Elchingen, which had a wide field of view. The French cleared the Austrian pickets and a regiment boldly attacked and captured the

abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christian monks and nuns.

The conce ...

at the top of the hill at bayonet point. The Austrian cavalry was also defeated and Riesch's infantry fled; Ney was given the title "Duke of Elchingen" for his impressive victory.

Battle of Ulm

Other actions took place on the 14th. Murat's forces joined Dupont at Albeck just in time to drive off an Austrian attack from Werneck; together Murat and Dupont beat the Austrians to the north in the direction of

Heidenheim. By night on the 14th, two French corps were stationed in the vicinity of the Austrian encampments at Michelsberg, right outside of Ulm.

[Chandler p. 399.] Mack was now in a dangerous situation: there was no longer any hope of escaping along the north bank, Marmont and the

Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, in ...

were hovering at the outskirts of Ulm to the south of the river, and Soult was moving from

Memmingen

Memmingen (; Swabian: ''Memmenge'') is a town in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is the economic, educational and administrative centre of the Danube-Iller region. To the west the town is flanked by the Iller, the river that marks the Baden-Wü ...

to prevent the Austrians escaping south to the Tyrol.

Troubles continued with the Austrian command as Ferdinand overrode the objections of Mack and ordered the evacuation of all cavalry from Ulm, a total of 6,000 troopers.

[Chandler p. 400.] Murat's pursuit was so effective, however, that only eleven squadrons joined Werneck at Heidenheim.

Murat continued his harassment of Werneck and forced him to surrender with 8,000 men at

Trochtelfingten on 19 October; Murat also took an entire Austrian field park of 500 vehicles, then swept on towards

Neustadt and captured 12,000 Austrians.

Events at Ulm were now reaching a conclusion. On 15 October, Ney's troops successfully charged the Michelsberg encampments and on the 16th the French began to bombard Ulm itself. Austrian morale was at a low point and Mack began to realize that there was little hope of rescue. On 17 October, Napoleon's emissary,

Ségur, signed a convention with Mack in which the Austrians agreed to surrender on 25 October if no aid came by that date.

Gradually, however, Mack heard of the capitulations at Heidenheim and

Neresheim

Neresheim is a town in the Ostalbkreis district, in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated northeast of Heidenheim, and southeast of Aalen.

It's the home of the Neresheim Abbey, which still hosts monks, was '' Reichsfrei'' until the Germa ...

and agreed to surrender five days before schedule on 20 October. 10,000 troops from the Austrian garrison managed to escape, but the vast majority of the Austrian force marched out on the 21st and laid down their arms without incident, all with the drawn up in a vast semicircle observing the capitulation.

Battle of Trafalgar

When the Third Coalition declared war on France after the short-lived

Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it se ...

, Napoleon Bonaparte was determined to invade Britain. To do so, he had to ensure that the Royal Navy would be unable to disrupt the invasion

flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

, which would require control of the English Channel.

The main French

fleets were at

Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

in

Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

and at

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

on the Mediterranean coast. Other ports on the French Atlantic coast contained smaller

squadrons. In addition, France and Spain were allied, so the Spanish fleet based in

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

and

Ferrol was also available.

The British possessed an experienced and well-trained corps of naval officers. By contrast, most of the best officers in the

French Imperial Navy

The French Imperial Navy () was the name given to the French Navy during the period of the Napoleonic Wars, and subsequently during the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte. The first use of the title 'Imperial Navy' was in 1804, following the Coronation ...

had either been executed or dismissed from the service during the early part of the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. As a result, Vice-Admiral

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre de Villeneuve (31 December 1763 – 22 April 1806) was a French naval officer during the Napoleonic Wars. He was in command of the French and the Spanish fleets that were defeated by Nelson at the Batt ...

was the most competent senior officer available to command Napoleon's Mediterranean fleet. However, Villeneuve had shown a distinct lack of enthusiasm to face Nelson and the Royal Navy after his defeat at the

Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; french: Bataille d'Aboukir) was a major naval battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast off the ...

.

Napoleon's naval plan in 1805 was for the French and Spanish fleets in the Mediterranean and Cádiz to break through the blockade and combine in the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. They would then return, assist the fleet in Brest to emerge from blockade, and in combination clear the

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

of Royal Navy ships, ensuring a safe passage for the invasion barges. The plan seemed good on paper but as the war wore on, Napoleon's unfamiliarity with naval strategy and ill-advised naval commanders continued to haunt the French.

West Indies

Early in 1804, Admiral Lord Nelson commanded the British fleet blockading Toulon. Unlike

William Cornwallis

Admiral of the Red Sir William Cornwallis, (10 February 17445 July 1819) was a Royal Navy officer. He was the brother of Charles Cornwallis, the 1st Marquess Cornwallis, British commander at the siege of Yorktown. Cornwallis took part in a n ...

, who maintained a tight blockade of Brest with the Channel Fleet, Nelson adopted a loose blockade in hopes of luring the French out for a major battle. However, Villeneuve's fleet successfully evaded Nelson's when his forces were blown off station by storms. While Nelson was searching the Mediterranean for him, Villeneuve passed through the

Straits of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medit ...

, rendezvoused with the Spanish fleet, and sailed as planned to the West Indies. Once Nelson realized that the French had crossed the Atlantic Ocean, he set off in pursuit. Admirals of the time, due to the slowness of communications, were given considerable autonomy to make

strategic

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

as well as

tactical

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tacti ...

decisions.

Cádiz

Villeneuve returned from the West Indies to Europe, intending to break the blockade at Brest, but after two of his Spanish ships were captured during the

Battle of Cape Finisterre by a squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir

Robert Calder

Admiral Sir Robert Calder, 1st Baronet, (2 July 174531 August 1818) was a British naval officer who served in the Seven Years' War, the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. For much of his career ...

, Villeneuve abandoned this plan and sailed back to Ferrol.

Napoleon's invasion plans for England depended entirely on having a sufficiently large number of ships of the line before

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; pcd, Boulonne-su-Mér; nl, Bonen; la, Gesoriacum or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Northern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department of Pas-de-Calais. Boulogne lies on the ...

, France. This would require Villeneuve's force of 32 ships to join Vice-Admiral

Ganteaume's force of 21 ships at Brest, along with a squadron of five ships under Captain Allemand, which would have given him a combined force of 58 ships of the line.

When Villeneuve set sail from Ferrol on 10 August, he was under strict orders from Napoleon to sail northward toward Brest. Instead, he worried that the British were observing his manoeuvres, so on 11 August he sailed southward towards Cádiz on the southwestern coast of Spain. With no sign of Villeneuve's fleet by 26 August, the three French army corps invasion force near Boulogne broke camp and marched to Germany, where it would become fully engaged.

The same month, Nelson returned home to England after two years of duty at sea, for some well-earned rest. He remained ashore for 25 busy days, and was warmly received by his countrymen, who were understandably nervous about a possible French invasion. Word reached England on 2 September about the combined French and Spanish fleet in the harbour of Cádiz. Nelson had to wait until 15 September before his ship

HMS ''Victory'' was ready to sail.

On 15 August, Cornwallis made the fateful decision to detach 20 ships of the line from the fleet guarding the channel and to have them sail southward to engage the enemy forces in Spain. This left the channel somewhat denuded of ships, with only eleven ships of the line present. However, this detached force formed the nucleus of the British fleet that would fight at Trafalgar. Initially this fleet was placed under the command of Vice-Admiral Calder, reaching Cádiz on 15 September. Nelson joined the fleet on 29 September to take command.

The British fleet used

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

s to keep a constant watch on the harbour, while the main force remained out of sight west of the shore. Nelson's hope was to lure the combined Franco-Spanish force out and engage them in a "pell-mell battle". The force watching the harbour was led by Captain

Henry Blackwood

Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Blackwood, 1st Baronet, GCH, KCB (28 December 1770 – 17 December 1832), whose memorial is in Killyleagh Parish Church, was a British sailor.

Early life

Blackwood was the fourth son of Sir John Blackwood, 2nd Baronet, ...

, commanding

HMS ''Euryalus''. He was brought up to a strength of seven ships (five frigates and two schooners) on 8 October.

Supply situation

At this point, Nelson's fleet badly needed provisioning. On 2 October, five ships of the line,

''Queen'',

''Canopus'',

''Spencer'',

''Zealous'',

''Tigre'', and the frigate

''Endymion'' were dispatched to

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

under Rear-Admiral Louis for supplies. These ships were later diverted for convoy duty in the Mediterranean, whereas Nelson had expected them to return. Other British ships continued to arrive, and by 15 October the fleet was up to full strength for the battle. Although it was a significant loss; once the first-rate

''Royal Sovereign'' had arrived, Nelson allowed Calder to sail for home in his flagship, the 98-gun

''Prince of Wales''. Calder's apparent lack of aggression during the engagement off

Cape Finisterre

Cape Finisterre (, also ; gl, Cabo Fisterra, italic=no ; es, Cabo Finisterre, italic=no ) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.

In Roman times it was believed to be an end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like ...

on 22 July, had caused the Admiralty to recall him for a court martial and he would normally have been sent back to Britain in a smaller ship.

Meanwhile, Villeneuve's fleet in Cádiz was also suffering from a serious supply shortage that could not be readily rectified by the cash-strapped French. The blockades maintained by the British fleet had made it difficult for the allies to obtain stores and their ships were ill fitted. Villeneuve's ships were also more than two thousand men short of the force needed to sail. These were not the only problems faced by the Franco-Spanish fleet. The main French ships of the line had been kept in harbour for years by the British blockades with only brief sorties. The hasty voyage across the Atlantic and back used up vital supplies and was no match for the British fleet's years of experience at sea and training. The French crews contained few experienced sailors, and as most of the crew had to be taught the elements of seamanship on the few occasions when they got to sea, gunnery was neglected. Villeneuve's supply situation began to improve in October, but news of Nelson's arrival made Villeneuve reluctant to leave port. Indeed, his captains had held a vote on the matter and decided to stay in the harbour.

On 14 September, Napoleon gave orders for the French and Spanish ships at Cádiz to put to sea at the first favourable opportunity, join seven Spanish ships of the line then at

Cartagena, go to

Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, and land the soldiers they carried to reinforce his troops there, and fight a decisive action if they met a British fleet of inferior numbers.

On 18 October,

Villeneuve

Villeneuve, LaVilleneuve or deVilleneuve may refer to:

People

* Villeneuve (surname)

Places

Australia

* Villeneuve, Queensland, a town in the Somerset Region

Canada

* Circuit Gilles Villeneuve, a Formula One racetrack in Montréal

* Villeneuv ...

received a letter informing him that Vice-Admiral

François Rosily had arrived in

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

with orders to take command. At the same time, he received intelligence that a detachment of six British ships had docked at

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

(this was Admiral Louis's squadron). Stung by the prospect of being disgraced before the fleet, Villeneuve resolved to go to sea before his successor could reach Cádiz. Following a gale on 18 October, the fleet began a rapid scramble to set sail.

Departure

The weather, however, suddenly turned calm following a week of gales. This slowed the progress of the fleet departing the harbour, giving the British plenty of warning. Villeneuve had drawn up plans to form a force of four squadrons, each containing both French and Spanish ships. Following their earlier vote to stay put, the captains were reluctant to leave Cádiz and as a result they failed to follow closely Villeneuve's orders (Villeneuve had reportedly become despised by many of the fleet's officers and crew). As a result, the fleet straggled out of the harbour in no particular formation.

It took most of 20 October for Villeneuve to get his fleet organised, and it set sail in three columns for the Straits of Gibraltar to the south-east. That same evening, the ship ''

Achille'' spotted a force of 18 British ships of the line in pursuit. The fleet began to prepare for battle and during the night they were ordered into a single line. The following day Nelson's fleet of 27 ships of the line and four frigates was spotted in pursuit from the north-west with the wind behind it. Villeneuve again ordered his fleet into three columns, but soon changed his mind and ordered a single line. The result was a sprawling, uneven formation.

The British fleet was sailing, as they would fight, under

signal 72 hoisted on Nelson's flagship. At 5:40 a.m., the British were about to the north-west of

Cape Trafalgar

Cape Trafalgar (; es, Cabo Trafalgar ) is a headland in the Province of Cádiz in the southwest of Spain. The 1805 naval Battle of Trafalgar, in which the Royal Navy commanded by Admiral Horatio Nelson decisively defeated Napoleon's combined Spa ...

, with the Franco-Spanish fleet between the British and the cape. At 6 a.m. that morning, Nelson gave the order to prepare for battle.

At 8 a.m., Villeneuve ordered the fleet to ''wear together'' and turn back for Cádiz. This reversed the order of the Allied line, placing the rear division under Rear-Admiral

Pierre Dumanoir le Pelley

Vice-Admiral Count Pierre Étienne René Marie Dumanoir Le Pelley (2 August 1770 in Granville – 7 July 1829 in Paris) was a French Navy officer, best known for commanding the vanguard of the French fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. His conduct d ...

in the vanguard, or "van." The wind became contrary at this point, often shifting direction. The very light wind rendered manoeuvering all but impossible for the most expert crews. The inexperienced crews had difficulty with the changing conditions, and it took nearly an hour and a half for Villeneuve's order to be completed. The French and Spanish fleet now formed an uneven, angular crescent, with the slower ships generally leeward and closer to the shore.

Villeneuve was painfully aware that the British fleet would not be content to attack him in the old-fashioned way, coming down in a parallel line and engaging from van to rear. He knew that they would endeavour to concentrate on a part of his line. But he was too conscious of the inexperience of his officers and men to consider making counter movements.

By 11 a.m. Nelson's entire fleet was visible to Villeneuve, drawn up in two parallel columns. The two fleets would be within range of each other within an hour. Villeneuve was concerned at this point about forming up a line, as his ships were unevenly spaced and in an irregular formation. The Franco-Spanish fleet was drawn out nearly long as Nelson's fleet approached.

As the British drew closer, they could see that the enemy was not sailing in a tight order, but rather in irregular groups. Nelson could not immediately make out the French flagship as the French and Spanish were not flying command pennants.

The six British ships dispatched earlier to Gibraltar had not returned, so Nelson would have to fight without them. He was outnumbered and outgunned, nearly 30,000 men and 2,568 guns to his 17,000 men and 2,148 guns. The Franco-Spanish fleet also had six more ships of the line, and so could more readily combine their fire. There was no way for some of Nelson's ships to avoid being "doubled on" or even "trebled on".

Engagement