Vulgar Latin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin, is the range of non-formal registers of

In general, the verbal system in the Romance languages changed less from Classical Latin than did the nominal system.

The four conjugational classes generally survived. The second and third conjugations already had identical imperfect tense forms in Latin, and also shared a common present participle. Because of the merging of short ''i'' with long ''ē'' in most of Vulgar Latin, these two conjugations grew even closer together. Several of the most frequently-used forms became indistinguishable, while others became distinguished only by stress placement:

These two conjugations came to be conflated in many of the Romance languages, often by merging them into a single class while taking endings from each of the original two conjugations. Which endings survived was different for each language, although most tended to favour second conjugation endings over the third conjugation. Spanish, for example, mostly eliminated the third conjugation forms in favour of second conjugation forms.

French and Catalan did the same, but tended to generalise the third conjugation infinitive instead. Catalan in particular almost eliminated the second conjugation ending over time, reducing it to a small relic class. In Italian, the two infinitive endings remained separate (but spelled identically), while the conjugations merged in most other respects much as in the other languages. However, the third-conjugation third-person plural present ending survived in favour of the second conjugation version, and was even extended to the fourth conjugation. Romanian also maintained the distinction between the second and third conjugation endings.

In the perfect, many languages generalized the ''-aui'' ending most frequently found in the first conjugation. This led to an unusual development; phonetically, the ending was treated as the diphthong rather than containing a semivowel , and in other cases the sound was simply dropped. We know this because it did not participate in the sound shift from to . Thus Latin ''amaui'', ''amauit'' ("I loved; he/she loved") in many areas became proto-Romance *''amai'' and *''amaut'', yielding for example Portuguese ''amei'', ''amou''. This suggests that in the spoken language, these changes in conjugation preceded the loss of .

Another major systemic change was to the

In general, the verbal system in the Romance languages changed less from Classical Latin than did the nominal system.

The four conjugational classes generally survived. The second and third conjugations already had identical imperfect tense forms in Latin, and also shared a common present participle. Because of the merging of short ''i'' with long ''ē'' in most of Vulgar Latin, these two conjugations grew even closer together. Several of the most frequently-used forms became indistinguishable, while others became distinguished only by stress placement:

These two conjugations came to be conflated in many of the Romance languages, often by merging them into a single class while taking endings from each of the original two conjugations. Which endings survived was different for each language, although most tended to favour second conjugation endings over the third conjugation. Spanish, for example, mostly eliminated the third conjugation forms in favour of second conjugation forms.

French and Catalan did the same, but tended to generalise the third conjugation infinitive instead. Catalan in particular almost eliminated the second conjugation ending over time, reducing it to a small relic class. In Italian, the two infinitive endings remained separate (but spelled identically), while the conjugations merged in most other respects much as in the other languages. However, the third-conjugation third-person plural present ending survived in favour of the second conjugation version, and was even extended to the fourth conjugation. Romanian also maintained the distinction between the second and third conjugation endings.

In the perfect, many languages generalized the ''-aui'' ending most frequently found in the first conjugation. This led to an unusual development; phonetically, the ending was treated as the diphthong rather than containing a semivowel , and in other cases the sound was simply dropped. We know this because it did not participate in the sound shift from to . Thus Latin ''amaui'', ''amauit'' ("I loved; he/she loved") in many areas became proto-Romance *''amai'' and *''amaut'', yielding for example Portuguese ''amei'', ''amou''. This suggests that in the spoken language, these changes in conjugation preceded the loss of .

Another major systemic change was to the

Paléoroman ''Daras'' (Pseudo-Frédégaire, VIIe siècle) : de la bonne interprétation d’un jalon de la romanistique

''Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris'', 112/1, p. 123-130. A periphrastic construction of the form 'to have to' (late Latin ''habere ad'') used as future is characteristic of Sardinian: * ''Ap'a istàre'' < ''apo a istàre'' 'I will stay' * ''Ap'a nàrrere'' < ''apo a nàrrer'' 'I will say' An innovative conditional (distinct from the

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

spoken from the Late Roman Republic onward. Through time, Vulgar Latin would evolve into numerous Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

. Its literary

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

counterpart was a form of either Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later periods ...

or Late Latin

Late Latin ( la, Latinitas serior) is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity.Roberts (1996), p. 537. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the , and continuing into the 7th century in t ...

, depending on the time period.

Origin of the term

During the Classical period, Roman authors referred to the informal, everyday variety of their own language as ''sermo plebeius'' or ''sermo vulgaris'', meaning "common speech". The modern usage of the term Vulgar Latin dates to theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, when Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

thinkers began to theorize that their own language originated in a sort of "corrupted" Latin that they assumed formed an entity distinct from the literary Classical variety, though opinions differed greatly on the nature of this "vulgar" dialect.

The early 19th-century French linguist Raynouard is often regarded as the father of modern Romance philology

Romance studies or Romance philology ( an, filolochía romanica; ca, filologia romànica; french: romanistique; eo, latinida filologio; it, filologia romanza; pt, filologia românica; ro, romanistică; es, filología románica) is an acade ...

. Observing that the Romance languages have many features in common that are not found in Latin, at least not in "proper" or Classical Latin, he concluded that the former must have all had some common ancestor (which he believed most closely resembled Old Occitan

Old Occitan ( oc, occitan ancian, label=Occitan language, Modern Occitan, ca, occità antic), also called Old Provençal, was the earliest form of the Occitano-Romance languages, as attested in writings dating from the eighth through the fourteen ...

) that replaced Latin some time before the year 1000. This he dubbed ''la langue romane'' or "the Roman language".

The first truly modern treatise on Romance linguistics, however, and the first to apply the comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor and then extrapolating backwards t ...

, was Friedrich Christian Diez

Friedrich Christian Diez (15 March 179429 May 1876) was a German philologist. The two works on which his fame rests are the ''Grammar of the Romance Languages'' (published 1836–1844), and the ''Etymological Dictionary of the Romance Languages'' ...

's seminal ''Grammar of the Romance Languages''.

Sources

Evidence for the features of non-literary Latin comes from the following sources: * Recurrent grammatical, syntactic, or orthographic mistakes in Latinepigraphy

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

.

* The insertion, whether intentional or not, of colloquial terms or constructions into contemporary texts.

* Explicit mention of certain constructions or pronunciation habits by Roman grammarians.

* The pronunciation of Roman-era lexical borrowings into neighboring languages such as Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

, or Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

.

History

By the end of the first century AD the Romans had conquered the entireMediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

and established hundreds of colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

in the conquered provinces. Over time this—along with other factors that encouraged linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

and cultural assimilation, such as political unity, frequent travel and commerce, military service, etc.—made Latin the predominant language throughout the western Mediterranean. Latin itself was subject to the same assimilatory tendencies, such that its varieties had probably become more uniform by the time the Western Empire fell in 476 than they had been before it. That is not to say that the language had been static for all those years, but rather that ongoing changes tended to spread to all regions.

All of these homogenizing factors were disrupted or voided by a long string of calamities. Although Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

succeeded in reconquering Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, and the southern part of Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

in the period 533–554, the Empire was hit by one of the deadliest plagues in recorded history in 541, one that would recur six more times before 610. Under his successors most of the Italian peninsula was lost to the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

by c. 572, most of southern Iberia to the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

by c. 615, and most of the Balkans to the Slavs and Avars by c. 620. All this was possible due to Roman preoccupation with wars against Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, the last of which lasted nearly three decades and exhausted both empires. Taking advantage of this, the Arabs invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

and occupied Syria and Egypt by 642, greatly weakening the Empire and ending its centuries of domination over the Mediterranean. They went on to take the rest of North Africa by c. 699 and soon invaded the Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic peoples, Germanic su ...

as well, seizing most of Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

from it by c. 716.

It is from approximately the seventh century onward that regional differences proliferate in the language of Latin documents, indicating the fragmentation of Latin into the incipient Romance languages. Until then Latin appears to have been remarkably homogenous, as far as can be judged from its written records, although careful statistical analysis reveals regional differences in the treatment of the Latin vowel /ĭ/ and in the progression of betacism

In historical linguistics, betacism (, ) is a sound change in which (the voiced bilabial plosive, as in ''bane'') and (the voiced labiodental fricative , as in ''vane'') are confused. The final result of the process can be either /b/ → or ...

by about the fifth century.

Vocabulary

Lexical turnover

Over the centuries, spoken Latin lost various lexical items and replaced them with native coinages; with borrowings from neighbouring languages such asGaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic languages, Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium ...

, Germanic, or Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

; or with other native words that had undergone semantic shift

Semantic change (also semantic shift, semantic progression, semantic development, or semantic drift) is a form of language change regarding the evolution of word usage—usually to the point that the modern meaning is radically different from ...

. The literary language

A literary language is the form (register) of a language used in written literature, which can be either a nonstandard dialect or a standardized variety of the language. Literary language sometimes is noticeably different from the spoken langu ...

generally retained the older words, however.

A textbook example is the general replacement of the suppletive In linguistics and etymology, suppletion is traditionally understood as the use of one word as the inflected form of another word when the two words are not cognate. For those learning a language, suppletive forms will be seen as "irregular" or even ...

Classical verb ''ferre'', meaning 'carry', with the regular ''portare''. Similarly, the Classical '' loqui'', meaning 'speak', was replaced by a variety of alternatives such as the native '' fabulari'' and '' narrare'' or the Greek borrowing '' parabolare''.

Classical Latin particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscule in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

fared especially poorly, with all of the following vanishing from popular speech: an, at, autem, donec, enim, etiam, haud

The Haud (also Hawd) (, ), formerly known as the Hawd Reserve Area is a plateau situated in the Horn of Africa consisting of thorn-bush and grasslands. The region includes the southern part of Somaliland as well as the northern and eastern part ...

, igitur, ita, nam, postquam, quidem, quin Quin may refer to:

* Quin (name), including a list of people with the name

* Quin, colloquially, one of a set of quintuplets, a multiple birth of five individuals

* Quin (Sigilverse), a fictional planet

* Quin, County Clare, a village in County ...

, quoad, quoque, sed

sed ("stream editor") is a Unix utility that parses and transforms text, using a simple, compact programming language. It was developed from 1973 to 1974 by Lee E. McMahon of Bell Labs,

and is available today for most operating systems.

sed w ...

, sive Sive may refer to:

*Sive means hear us in isiXhosa

* David Sive (1922–2014), American attorney, environmentalist, and professor of environmental law

* Sive (noun), a Nation, a large body of people united by common descent, history, culture, or l ...

, utrum

Swedish is descended from Old Norse. Compared to its progenitor, Swedish grammar is much less characterized by inflection. Modern Swedish has two genders and no longer conjugates verbs based on person or number. Its nouns have lost the morpholog ...

, and vel

Vel ( ta, வேல், lit=Vēl) is a divine javelin or spear associated with Murugan, the Hindu god of war.

Significance

According to Shaiva tradition, the goddess Parvati presented the Vel to her son Murugan, as an embodiment of her shakti, ...

.

Semantic drift

Many surviving words experienced a shift in meaning. Some notable cases are ''civitas'' ('citizenry' ''→'' 'city', replacing ''urbs''); ''focus'' ('hearth' ''→'' 'fire', replacing ''ignis''); ''manducare'' ('chew' ''→'' 'eat', replacing ''edere''); ''causa'' ('subject matter' ''→'' 'thing', competing with ''res''); ''mittere'' ('send' → 'put', competing with ''ponere''); ''necare'' ('murder' ''→'' 'drown', competing with ''submergere''); ''pacare'' ('placate' ''→'' 'pay', competing with ''solvere''), and ''totus'' ('whole' ''→'' 'all, every', competing with ''omnis'').Phonological development

Consonantism

Loss of nasals

* Word-final /m/ was lost in polysyllabic words. In monosyllables it tended to survive as /n/. * /n/ was usually lost beforefricative

A fricative is a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate in t ...

s, resulting in compensatory lengthening

Compensatory lengthening in phonology and historical linguistics is the lengthening of a vowel sound that happens upon the loss of a following consonant, usually in the syllable coda, or of a vowel in an adjacent syllable. Lengthening triggered ...

of the preceding vowel (e.g. '' sponsa'' ‘fiancée’ > ''spōsa'').

Palatalization

Front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

s in hiatus

Hiatus may refer to:

*Hiatus (anatomy), a natural fissure in a structure

* Hiatus (stratigraphy), a discontinuity in the age of strata in stratigraphy

*''Hiatus'', a genus of picture-winged flies with sole member species '' Hiatus fulvipes''

* Gl ...

(after a consonant and before another vowel) became which palatalized preceding consonants.

Fricativization

/w/ (except after /k/) andintervocalic

In phonetics and phonology, an intervocalic consonant is a consonant that occurs between two vowels. Intervocalic consonants are often associated with lenition, a phonetic process that causes consonants to weaken and eventually disappear entirel ...

/b/ merge as the bilabial fricative /β/.

Simplification of consonant clusters

* The cluster /nkt/ reduced to �t * /kw/ delabialized to /k/ beforeback vowel

A back vowel is any in a class of vowel sound used in spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a back vowel is that the highest point of the tongue is positioned relatively back in the mouth without creating a constriction that would be c ...

s.

* /ks/ before or after a consonant, or at the end of a word, reduced to /s/.

Vocalism

Monophthongization

*/ae̯/ and /oe̯/ monophthongized to �ːand ːrespectively by around the second century AD.Loss of vowel quantity

The system of phonemic vowel length collapsed by the fifth century AD, leavingquality

Quality may refer to:

Concepts

*Quality (business), the ''non-inferiority'' or ''superiority'' of something

*Quality (philosophy), an attribute or a property

*Quality (physics), in response theory

*Energy quality, used in various science discipli ...

differences as the distinguishing factor between vowels; the paradigm thus changed from /ī ĭ ē ĕ ā ă ŏ ō ŭ ū/ to /i ɪ e ɛ a ɔ o ʊ u/. Concurrently, stressed vowels in open syllables lengthened.

Loss of near-close front vowel

Towards the end of the Roman Empire /ɪ/ merged with /e/ in most regions, although not in Africa or a few peripheral areas in Italy.Grammar

Romance articles

It is difficult to place the point in which thedefinite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" ar ...

, absent in Latin but present in all Romance languages, arose, largely because the highly colloquial speech in which it arose was seldom written down until the daughter languages had strongly diverged; most surviving texts in early Romance show the articles fully developed.

Definite articles evolved from demonstrative pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun (abbreviated ) is a word or a group of words that one may substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the parts of speech, but some modern theorists would not co ...

s or adjective

In linguistics, an adjective (list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that generally grammatical modifier, modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Tra ...

s (an analogous development is found in many Indo-European languages, including Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

and Germanic); compare the fate of the Latin demonstrative adjective

Demonstratives (abbreviated ) are words, such as ''this'' and ''that'', used to indicate which entities are being referred to and to distinguish those entities from others. They are typically deictic; their meaning depending on a particular frame ...

, , "that", in the Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

, becoming French and (Old French ''li'', ''lo'', ''la''), Catalan and Spanish , and , Occitan and , Portuguese and (elision of -l- is a common feature of Portuguese) and Italian , and . Sardinian went its own way here also, forming its article from , "this" (''su, sa''); some Catalan and Occitan dialects have articles from the same source. While most of the Romance languages put the article before the noun, Romanian has its own way, by putting the article after the noun, e.g. ''lupul'' ("the wolf" – from *''lupum illum'') and ''omul'' ("the man" – ''*homo illum''),Vincent (1990). possibly a result of being within the Balkan sprachbund.

This demonstrative is used in a number of contexts in some early texts in ways that suggest that the Latin demonstrative was losing its force. The Vetus Latina

''Vetus Latina'' ("Old Latin" in Latin), also known as ''Vetus Itala'' ("Old Italian"), ''Itala'' ("Italian") and Old Italic, and denoted by the siglum \mathfrak, is the collective name given to the Latin translations of biblical texts (bot ...

Bible contains a passage ''Est tamen ille daemon sodalis peccati'' ("The devil is a companion of sin"), in a context that suggests that the word meant little more than an article. The need to translate sacred text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

s that were originally in Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

, which had a definite article, may have given Christian Latin an incentive to choose a substitute. Aetheria uses ''ipse'' similarly: ''per mediam vallem ipsam'' ("through the middle of the valley"), suggesting that it too was weakening in force.Harrington et al. (1997).

Another indication of the weakening of the demonstratives can be inferred from the fact that at this time, legal and similar texts begin to swarm with , , and so forth (all meaning, essentially, "aforesaid"), which seem to mean little more than "this" or "that". Gregory of Tours writes, ''Erat autem... beatissimus Anianus in supradicta civitate episcopus'' ("Blessed Anianus was bishop in that city.") The original Latin demonstrative adjectives were no longer felt to be strong or specific enough.

In less formal speech, reconstructed forms suggest that the inherited Latin demonstratives were made more forceful by being compounded with (originally an interjection

An interjection is a word or expression that occurs as an utterance on its own and expresses a spontaneous feeling or reaction. It is a diverse category, encompassing many different parts of speech, such as exclamations ''(ouch!'', ''wow!''), curse ...

: "behold!"), which also spawned Italian through , a contracted form of ''ecce eum''. This is the origin of Old French (*''ecce ille''), (*''ecce iste'') and (*''ecce hic''); Italian (*''eccum istum''), (*''eccum illum'') and (now mainly Tuscan) (*''eccum tibi istum''), as well as (*''eccu hic''), (*''eccum hac''); Spanish and Occitan and Portuguese (*''eccum ille''); Spanish and Portuguese (*''eccum hac''); Spanish and Portuguese (*''eccum hic''); Portuguese (*''eccum illac'') and (*''eccum inde''); Romanian (*''ecce iste'') and (*''ecce ille''), and many other forms.

On the other hand, even in the Oaths of Strasbourg

The Oaths of Strasbourg were a military pact made on 14 February 842 by Charles the Bald and Louis the German against their older brother Lothair I, the designated heir of Louis the Pious, the successor of Charlemagne. One year later the Trea ...

, no demonstrative appears even in places where one would clearly be called for in all the later languages (''pro christian poblo'' – "for the Christian people"). Using the demonstratives as articles may have still been considered overly informal for a royal oath in the 9th century. Considerable variation exists in all of the Romance vernaculars as to their actual use: in Romanian, the articles are suffixed to the noun (or an adjective preceding it), as in other languages of the Balkan sprachbund and the North Germanic languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also r ...

.

The numeral , (one) supplies the indefinite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" ar ...

in all cases (again, this is a common semantic development across Europe). This is anticipated in Classical Latin; Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

writes ''cum uno gladiatore nequissimo'' ("with a most immoral gladiator"). This suggests that ''unus'' was beginning to supplant in the meaning of "a certain" or "some" by the 1st century BC.

Loss of neuter gender

The threegrammatical genders

In linguistics, grammatical gender system is a specific form of noun class system, where nouns are assigned with gender categories that are often not related to their real-world qualities. In languages with grammatical gender, most or all noun ...

of Classical Latin were replaced by a two-gender system in most Romance languages.

The neuter gender of classical Latin was in most cases identical with the masculine both syntactically and morphologically. The confusion had already started in Pompeian

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

graffiti, e.g. ''cadaver mortuus'' for ''cadaver mortuum'' ("dead body"), and ''hoc locum'' for ''hunc locum'' ("this place"). The morphological confusion shows primarily in the adoption of the nominative ending ''-us'' (''-Ø'' after ''-r'') in the ''o''-declension.

In Petronius

Gaius Petronius Arbiter"Gaius Petronius Arbiter"

freedman A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

.

In modern Romance languages, the nominative ''s''-ending has been largely abandoned, and all substantives of the ''o''-declension have an ending derived from ''-um'': ''-u'', ''-o'', or ''-Ø''. E.g., masculine ("wall"), and neuter ("sky") have evolved to: Italian , ; Portuguese , ; Spanish , , Catalan , ; Romanian , ''cieru>''; French , . However, Old French still had ''-s'' in the nominative and ''-Ø'' in the accusative in both words: ''murs'', ''ciels'' ominative– ''mur'', ''ciel'' blique

For some neuter nouns of the third declension, the oblique stem was productive; for others, the nominative/accusative form, (the two were identical in Classical Latin). Evidence suggests that the neuter gender was under pressure well back into the imperial period. French ''(le)'' , Catalan ''(la)'' , Occitan ''(lo)'' , Spanish ''(la)'' , Portuguese ''(o)'' , Italian language ''(il)'' , Leonese ''(el) lleche'' and Romanian ''(le)'' ("milk"), all derive from the non-standard but attested Latin nominative/accusative neuter or accusative masculine . In Spanish the word became feminine, while in French, Portuguese and Italian it became masculine (in Romanian it remained neuter, /). Other neuter forms, however, were preserved in Romance; Catalan and French , Leonese, Portuguese and Italian , Romanian ("name") all preserve the Latin nominative/accusative ''nomen'', rather than the oblique stem form *''nominem'' (which nevertheless produced Spanish ).

Most neuter nouns had plural forms ending in -A or -IA; some of these were reanalysed as feminine singulars, such as ("joy"), plural ''gaudia''; the plural form lies at the root of the French feminine singular ''(la)'' , as well as of Catalan and Occitan ''(la)'' (Italian ''la'' is a borrowing from French); the same for ("wood stick"), plural ''ligna'', that originated the Catalan feminine singular noun ''(la)'' , Portuguese ''(a)'' and Spanish ''(la)'' . Some Romance languages still have a special form derived from the ancient neuter plural which is treated grammatically as feminine: e.g., : BRACCHIA "arm(s)" → Italian ''(il)'' : ''(le) braccia'', Romanian : ''brațe(le)''. Cf. also freedman A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

Latin ''ipsa animalia aliquas mortas fuerant''.

Alternations in Italian heteroclitic nouns such as ''l'uovo fresco'' ("the fresh egg") / ''le uova fresche'' ("the fresh eggs") are usually analysed as masculine in the singular and feminine in the plural, with an irregular plural in ''-a''. However, it is also consistent with their historical development to say that is simply a regular neuter noun (, plural ''ova'') and that the characteristic ending for words agreeing with these nouns is ''-o'' in the singular and ''-e'' in the plural. The same alternation in gender exists in certain Romanian nouns, but is considered regular as it is more common than in Italian. Thus, a relict neuter gender can arguably be said to persist in Italian and Romanian.

In Portuguese, traces of the neuter plural can be found in collective formations and words meant to inform a bigger size or sturdiness. Thus, one can use ''/ovos'' ("egg/eggs") and ''/ovas'' ("roe", "a collection of eggs"), ''/bordos'' ("section(s) of an edge") and ''/bordas'' ("edge/edges"), ''/sacos'' ("bag/bags") and ''/sacas'' ("sack/sacks"), ''/mantos'' ("cloak/cloaks") and ''/mantas'' ("blanket/blankets"). Other times, it resulted in words whose gender may be changed more or less arbitrarily, like / ("fruit"), / (broth"), etc.

These formations were especially common when they could be used to avoid irregular forms. In Latin, the names of trees were usually feminine, but many were declined in the second declension paradigm, which was dominated by masculine or neuter nouns. Latin ("pear

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in the Northern Hemisphere in late summer into October. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus ''Pyrus'' , in the family Rosaceae, bearing the p ...

tree"), a feminine noun with a masculine-looking ending, became masculine in Italian ''(il)'' and Romanian ; in French and Spanish it was replaced by the masculine derivations ''(le)'' , ''(el)'' ; and in Portuguese and Catalan by the feminine derivations ''(a)'' , ''(la)'' .

As usual, irregularities persisted longest in frequently used forms. From the fourth declension noun ''manus'' ("hand"), another feminine noun with the ending ''-us'', Italian and Spanish derived ''(la)'' , Romanian ''mânu>'' pl (reg.)''mâini/'', Catalan ''(la)'' , and Portuguese ''(a)'' , which preserve the feminine gender along with the masculine appearance.

Except for the Italian and Romanian heteroclitic nouns, other major Romance languages have no trace of neuter nouns, but still have neuter pronouns. French / / ("this"), Spanish / / ("this"), Italian: / / ("to him" /"to her" / "to it"), Catalan: , , , ("it" / ''this'' / ''this-that'' / ''that over there''); Portuguese: / / ("all of him" / "all of her" / "all of it").

In Spanish, a three-way contrast is also made with the definite articles , , and . The last is used with nouns denoting abstract categories: ''lo bueno'', literally "that which is good", from : good.

Loss of oblique cases

The Vulgar Latin vowel shifts caused the merger of several case endings in the nominal and adjectival declensions. Some of the causes include: the loss of final ''m'', the merger of ''ă'' with ''ā'', and the merger of ''ŭ'' with ''ō'' (see tables). Thus, by the 5th century, the number of case contrasts had been drastically reduced. There also seems to be a marked tendency to confuse different forms even when they had not become homophonous (like the generally more distinct plurals), which indicates that nominal declension was shaped not only by phonetic mergers, but also by structural factors. As a result of the untenability of the noun case system after these phonetic changes, Vulgar Latin shifted from a markedlysynthetic language

A synthetic language uses inflection or agglutination to express Syntax, syntactic relationships within a sentence. Inflection is the addition of morphemes to a root word that assigns grammatical property to that word, while agglutination is the ...

to a more analytic one.

The genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can al ...

died out around the 3rd century AD, according to Meyer-Lübke, and began to be replaced by "de" + noun (which originally meant "about/concerning", weakened to "of") as early as the 2nd century BC. Exceptions of remaining genitive forms are some pronouns, certain fossilized expressions and some proper names. For example, French ("Thursday") < Old French ''juesdi'' < Vulgar Latin ""; Spanish ''es'' ("it is necessary") < "est "; and Italian ("earthquake") < "" as well as names like ''Paoli'', ''Pieri''.

The dative case

In grammar, the dative case (abbreviated , or sometimes when it is a core argument) is a grammatical case used in some languages to indicate the recipient or beneficiary of an action, as in "Maria Jacobo potum dedit", Latin for "Maria gave Jacob a ...

lasted longer than the genitive, even though Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the gen ...

, in the 2nd century BC, already shows some instances of substitution by the construction "ad" + accusative. For example, "ad carnuficem dabo".

The accusative case

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘the ...

developed as a prepositional case, displacing many instances of the ablative

In grammar, the ablative case (pronounced ; sometimes abbreviated ) is a grammatical case for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the grammars of various languages; it is sometimes used to express motion away from something, among other uses. T ...

. Towards the end of the imperial period, the accusative came to be used more and more as a general oblique case.

Despite increasing case mergers, nominative and accusative forms seem to have remained distinct for much longer, since they are rarely confused in inscriptions. Even though Gaulish texts from the 7th century rarely confuse both forms, it is believed that both cases began to merge in Africa by the end of the empire, and a bit later in parts of Italy and Iberia. Nowadays, Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

maintains a two-case system, while Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

and Old Occitan

Old Occitan ( oc, occitan ancian, label=Occitan language, Modern Occitan, ca, occità antic), also called Old Provençal, was the earliest form of the Occitano-Romance languages, as attested in writings dating from the eighth through the fourteen ...

had a two-case subject-oblique system.

This Old French system was based largely on whether or not the Latin case ending contained an "s" or not, with the "s" being retained but all vowels in the ending being lost (as with ''veisin'' below). But since this meant that it was easy to confuse the singular nominative with the plural oblique, and the plural nominative with the singular oblique, this case system ultimately collapsed as well, and Middle French adopted one case (usually the oblique) for all purposes.

Today, Romanian is generally considered the only Romance language with a surviving case system. However, some dialects of Romansh retain a special predicative form of the masculine singular identical to the plural: ''il bien vin'' ("the good wine") vs. ''il vin ei buns'' ("the wine is good"). This "predicative case" (as it is sometimes called) is a remnant of the Latin nominative in ''-us''.

Wider use of prepositions

Loss of a productive noun case system meant that thesyntactic

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), ...

purposes it formerly served now had to be performed by preposition

Prepositions and postpositions, together called adpositions (or broadly, in traditional grammar, simply prepositions), are a class of words used to express spatial or temporal relations (''in'', ''under'', ''towards'', ''before'') or mark various ...

s and other paraphrases. These particles increased in number, and many new ones were formed by compounding old ones. The descendant Romance languages are full of grammatical particles such as Spanish , "where", from Latin + (which in Romanian literally means "from where"/"where from"), or French , "since", from + , while the equivalent Spanish and Portuguese is ''de'' + ''ex'' + ''de''. Spanish and Portuguese , "after", represent ''de'' + ''ex'' + .

Some of these new compounds appear in literary texts during the late empire; French , Spanish ''de'' and Portuguese ''de'' ("outside") all represent ''de'' + (Romanian – ''ad'' + ''foris''), and we find Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

writing ''stulti, nonne qui fecit, quod de foris est, etiam id, quod de intus est fecit?'' (Luke 11.40: "ye fools, did not he, that made which is without, make that which is within also?"). In some cases, compounds were created by combining a large number of particles, such as the Romanian ("just recently") from ''ad'' + ''de'' + ''in'' + ''illa'' + ''hora''.

Classical Latin:

:''Marcus patrī librum dat.'' "Marcus is giving isfather /thebook."

Vulgar Latin:

:''*Marcos da libru a patre.'' "Marcus is giving /thebook to isfather."

Just as in the disappearing dative case, colloquial Latin sometimes replaced the disappearing genitive case with the preposition ''de'' followed by the ablative, then eventually the accusative (oblique).

Classical Latin:

:''Marcus mihi librum patris dat.'' "Marcus is giving me isfather's book.

Vulgar Latin:

:''*Marcos mi da libru de patre.'' "Marcus is giving me hebook of isfather."

Pronouns

Unlike in the nominal and adjectival inflections, pronouns kept great part of the case distinctions. However, many changes happened. For example, the of ''ego'' was lost by the end of the empire, and ''eo'' appears in manuscripts from the 6th century.Adverbs

Classical Latin had a number of different suffixes that madeadverb An adverb is a word or an expression that generally modifies a verb, adjective, another adverb, determiner, clause, preposition, or sentence. Adverbs typically express manner, place, time, frequency, degree, level of certainty, etc., answering ...

s from adjective

In linguistics, an adjective (list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that generally grammatical modifier, modifies a noun or noun phrase or describes its referent. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Tra ...

s: , "dear", formed , "dearly"; , "fiercely", from ; , "often", from . All of these derivational suffixes were lost in Vulgar Latin, where adverbs were invariably formed by a feminine ablative

In grammar, the ablative case (pronounced ; sometimes abbreviated ) is a grammatical case for nouns, pronouns, and adjectives in the grammars of various languages; it is sometimes used to express motion away from something, among other uses. T ...

form modifying , which was originally the ablative of ''mēns'', and so meant "with a ... mind". So ("quick") instead of ("quickly") gave ''veloci mente'' (originally "with a quick mind", "quick-mindedly")

This explains the widespread rule for forming adverbs in many Romance languages: add the suffix -''ment(e)'' to the feminine form of the adjective. The development illustrates a textbook case of grammaticalization

In historical linguistics, grammaticalization (also known as grammatization or grammaticization) is a process of language change by which words representing objects and actions (i.e. nouns and verbs) become grammatical markers (such as affixes or p ...

in which an autonomous form, the noun meaning 'mind', while still in free lexical use in e.g. Italian ''venire in mente'' 'come to mind', becomes a productive suffix for forming adverbs in Romance such as Italian , Spanish 'clearly', with both its source and its meaning opaque in that usage other than as adverb formant.

Verbs

In general, the verbal system in the Romance languages changed less from Classical Latin than did the nominal system.

The four conjugational classes generally survived. The second and third conjugations already had identical imperfect tense forms in Latin, and also shared a common present participle. Because of the merging of short ''i'' with long ''ē'' in most of Vulgar Latin, these two conjugations grew even closer together. Several of the most frequently-used forms became indistinguishable, while others became distinguished only by stress placement:

These two conjugations came to be conflated in many of the Romance languages, often by merging them into a single class while taking endings from each of the original two conjugations. Which endings survived was different for each language, although most tended to favour second conjugation endings over the third conjugation. Spanish, for example, mostly eliminated the third conjugation forms in favour of second conjugation forms.

French and Catalan did the same, but tended to generalise the third conjugation infinitive instead. Catalan in particular almost eliminated the second conjugation ending over time, reducing it to a small relic class. In Italian, the two infinitive endings remained separate (but spelled identically), while the conjugations merged in most other respects much as in the other languages. However, the third-conjugation third-person plural present ending survived in favour of the second conjugation version, and was even extended to the fourth conjugation. Romanian also maintained the distinction between the second and third conjugation endings.

In the perfect, many languages generalized the ''-aui'' ending most frequently found in the first conjugation. This led to an unusual development; phonetically, the ending was treated as the diphthong rather than containing a semivowel , and in other cases the sound was simply dropped. We know this because it did not participate in the sound shift from to . Thus Latin ''amaui'', ''amauit'' ("I loved; he/she loved") in many areas became proto-Romance *''amai'' and *''amaut'', yielding for example Portuguese ''amei'', ''amou''. This suggests that in the spoken language, these changes in conjugation preceded the loss of .

Another major systemic change was to the

In general, the verbal system in the Romance languages changed less from Classical Latin than did the nominal system.

The four conjugational classes generally survived. The second and third conjugations already had identical imperfect tense forms in Latin, and also shared a common present participle. Because of the merging of short ''i'' with long ''ē'' in most of Vulgar Latin, these two conjugations grew even closer together. Several of the most frequently-used forms became indistinguishable, while others became distinguished only by stress placement:

These two conjugations came to be conflated in many of the Romance languages, often by merging them into a single class while taking endings from each of the original two conjugations. Which endings survived was different for each language, although most tended to favour second conjugation endings over the third conjugation. Spanish, for example, mostly eliminated the third conjugation forms in favour of second conjugation forms.

French and Catalan did the same, but tended to generalise the third conjugation infinitive instead. Catalan in particular almost eliminated the second conjugation ending over time, reducing it to a small relic class. In Italian, the two infinitive endings remained separate (but spelled identically), while the conjugations merged in most other respects much as in the other languages. However, the third-conjugation third-person plural present ending survived in favour of the second conjugation version, and was even extended to the fourth conjugation. Romanian also maintained the distinction between the second and third conjugation endings.

In the perfect, many languages generalized the ''-aui'' ending most frequently found in the first conjugation. This led to an unusual development; phonetically, the ending was treated as the diphthong rather than containing a semivowel , and in other cases the sound was simply dropped. We know this because it did not participate in the sound shift from to . Thus Latin ''amaui'', ''amauit'' ("I loved; he/she loved") in many areas became proto-Romance *''amai'' and *''amaut'', yielding for example Portuguese ''amei'', ''amou''. This suggests that in the spoken language, these changes in conjugation preceded the loss of .

Another major systemic change was to the future tense

In grammar, a future tense (abbreviated ) is a verb form that generally marks the event described by the verb as not having happened yet, but expected to happen in the future. An example of a future tense form is the French ''aimera'', meaning ...

, remodelled in Vulgar Latin with auxiliary verbs

An auxiliary verb (abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or a p ...

. A new future was originally formed with the auxiliary verb , *''amare habeo'', literally "to love I have" (cf. English "I have to love", which has shades of a future meaning). This was contracted into a new future suffix in Western Romance forms, which can be seen in the following modern examples of "I will love":

* french: j'aimerai (''je'' + ''aimer'' + ''ai'') ← ''aimer'' to love"+ ''ai'' I have"

* Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

and gl, amarei (''amar'' + 'h'''ei'') ← ''amar'' to love"+ ''hei'' I have"* Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

and ca, amaré (''amar'' + 'h'''e'') ← ''amar'' to love"+ ''he'' I have"

* it, amerò (''amar'' + 'h'''o'') ← ''amare'' to love"+ ''ho'' I have"

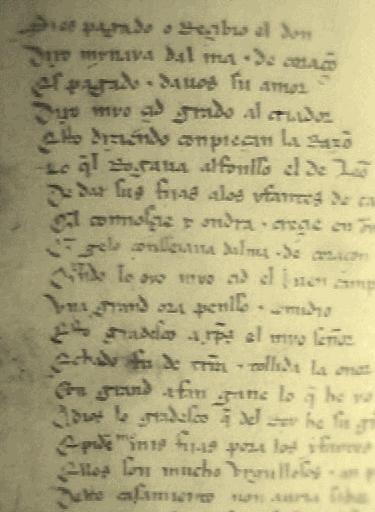

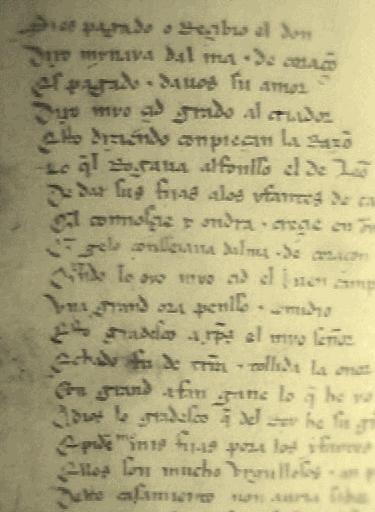

The first historical attestation of this new future can be found in a 7th-century Latin lext, the ''Chronicle of Fredegar

The ''Chronicle of Fredegar'' is the conventional title used for a 7th-century Frankish chronicle that was probably written in Burgundy. The author is unknown and the attribution to Fredegar dates only from the 16th century.

The chronicle begin ...

''Peter Nahon (2017Paléoroman ''Daras'' (Pseudo-Frédégaire, VIIe siècle) : de la bonne interprétation d’un jalon de la romanistique

''Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris'', 112/1, p. 123-130. A periphrastic construction of the form 'to have to' (late Latin ''habere ad'') used as future is characteristic of Sardinian: * ''Ap'a istàre'' < ''apo a istàre'' 'I will stay' * ''Ap'a nàrrere'' < ''apo a nàrrer'' 'I will say' An innovative conditional (distinct from the

subjunctive

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

) also developed in the same way (infinitive + conjugated form of ''habere''). The fact that the future and conditional endings were originally independent words is still evident in literary Portuguese, which in these tenses allows clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic (, backformed from Greek "leaning" or "enclitic"Crystal, David. ''A First Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics''. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980. Print.) is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a w ...

object pronouns to be incorporated between the root of the verb and its ending: "I will love" (''eu'') ''amarei'', but "I will love you" ''amar-te-ei'', from ''amar'' + ''te'' you"+ (''eu'') ''hei'' = ''amar'' + ''te'' + 'h'''ei'' = ''amar-te-ei''.

In Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, personal pronouns can still be omitted from verb phrases as in Latin, as the endings are still distinct enough to convey that information: ''venio'' > Sp ''vengo'' ("I come"). In French, however, all the endings are typically homophonous except the first and second person (and occasionally also third person) plural, so the pronouns are always used (''je viens'') except in the imperative.

Contrary to the millennia-long continuity of much of the active verb system, which has now survived 6000 years of known evolution, the synthetic passive voice

A passive voice construction is a grammatical voice construction that is found in many languages. In a clause with passive voice, the grammatical subject expresses the ''theme'' or ''patient'' of the main verb – that is, the person or thing t ...

was utterly lost in Romance, being replaced with periphrastic

In linguistics, periphrasis () is the use of one or more function words to express meaning that otherwise may be expressed by attaching an affix or clitic to a word. The resulting phrase includes two or more collocated words instead of one infl ...

verb forms—composed of the verb "to be" plus a passive participle—or impersonal reflexive forms—composed of a verb and a passivizing pronoun.

Apart from the grammatical and phonetic developments there were many cases of verbs merging as complex subtleties in Latin were reduced to simplified verbs in Romance. A classic example of this are the verbs expressing the concept "to go". Consider three particular verbs in Classical Latin expressing concepts of "going": , , and *''ambitare''. In Spanish and Portuguese ''ire'' and ''vadere'' merged into the verb ''ir'', which derives some conjugated forms from ''ire'' and some from ''vadere''. ''andar'' was maintained as a separate verb derived from ''ambitare''.

Italian instead merged ''vadere'' and ''ambitare'' into the verb . At the extreme French merged three Latin verbs with, for example, the present tense deriving from ''vadere'' and another verb ''ambulare'' (or something like it) and the future tense deriving from ''ire''.

Similarly the Romance distinction between the Romance verbs for "to be", and , was lost in French as these merged into the verb . In Italian, the verb inherited both Romance meanings of "being essentially" and "being temporarily of the quality of", while specialized into a verb denoting location or dwelling, or state of health.

Copula

The copula (that is, the verb signifying "to be") of Classical Latin was . This evolved to *''essere'' in Vulgar Latin by attaching the common infinitive suffix ''-re'' to the classical infinitive; this produced Italian and French through Proto-Gallo-Romance *''essre'' and Old French as well as Spanish and Portuguese (Romanian ''a'' derives from ''fieri'', which means "to become"). In Vulgar Latin a second copula developed utilizing the verb , which originally meant (and is cognate with) "to stand", to denote a more temporary meaning. That is, *''essere'' signified the ''esse''nce, while ''stare'' signified the ''state.'' ''Stare'' evolved to Spanish and Portuguese and Old French (both through *''estare''), Romanian "a sta" ("to stand"), using the original form for the noun ("stare"="state"/"starea"="the state"), while Italian retained the original form. The semantic shift that underlies this evolution is more or less as follows: A speaker of Classical Latin might have said: ''vir est in foro'', meaning "the man is in/at the marketplace". The same sentence in Vulgar Latin could have been *''(h)omo stat in foro'', "the man stands in/at the marketplace", replacing the ''est'' (from ''esse'') with ''stat'' (from ''stare''), because "standing" was what was perceived as what the man was actually doing. The use of ''stare'' in this case was still semantically transparent assuming that it meant "to stand", but soon the shift from ''esse'' to ''stare'' became more widespread. In the Iberian peninsula ''esse'' ended up only denoting natural qualities that would not change, while ''stare'' was applied to transient qualities and location. In Italian, ''stare'' is used mainly for location, transitory state of health (''sta male'' 's/he is ill' but ''è gracile'' 's/he is puny') and, as in Spanish, for the eminently transient quality implied in a verb's progressive form, such as ''sto scrivendo'' to express 'I am writing'. The historical development of the ''stare'' + ablative gerund progressive tense in those Romance languages that have it seems to have been a passage from a usage such as ''sto pensando'' 'I stand/stay (here) in thinking', in which the ''stare'' form carries the full semantic load of 'stand, stay' togrammaticalization

In historical linguistics, grammaticalization (also known as grammatization or grammaticization) is a process of language change by which words representing objects and actions (i.e. nouns and verbs) become grammatical markers (such as affixes or p ...

of the construction as expression of progressive aspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

(Similar in concept to the Early Modern English construction of "I am a-thinking"). The process of reanalysis that took place over time bleached the semantics of ''stare'' so that when used in combination with the gerund the form became solely a grammatical marker of subject and tense (e.g. ''sto'' = subject first person singular, present; ''stavo'' = subject first person singular, past), no longer a lexical verb In linguistics a lexical verb or main verb is a member of an open class of verbs that includes all verbs except auxiliary verbs. Lexical verbs typically express action, state, or other predicate meaning. In contrast, auxiliary verbs express gramm ...

with the semantics of 'stand' (not unlike the auxiliary in compound tenses that once meant 'have, possess', but is now semantically empty: ''j'ai écrit'', ''ho scritto'', ''he escrito'', etc.). Whereas ''sto scappando'' would once have been semantically strange at best (?'I stay escaping'), once grammaticalization was achieved, collocation with a verb of inherent mobility was no longer contradictory, and ''sto scappando'' could and did become the normal way to express 'I am escaping'. (Although it might be objected that in sentences like Spanish ''la catedral está en la ciudad'', "the cathedral is in the city" this is also unlikely to change, but all locations are expressed through ''estar'' in Spanish, as this usage originally conveyed the sense of "the cathedral ''stands'' in the city").

Word order typology

Classical Latin in most cases adopted an SOV word order in ordinary prose, although other word orders were employed, such as in poetry, enabled byinflection

In linguistic morphology, inflection (or inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and defin ...

al marking of the grammatical function of words. However, word order in the modern Romance languages generally adopted a standard SVO word order. This had to develop as a result of stylistic changes in the language over time. The object of the word can be after the verb to break monotony of the verb final structure and/or place emphasis on the object. This style became evidently more predominant over time and widespread in Romance. Fragments of SOV word order still survive in the placement of clitic

In morphology and syntax, a clitic (, backformed from Greek "leaning" or "enclitic"Crystal, David. ''A First Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics''. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1980. Print.) is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a w ...

object pronouns (e.g. Spanish ''yo te amo'' "I love you").

See also

*Proto-Romance

Proto-Romance is the comparatively reconstructed ancestor of all Romance languages. It reflects a late variety of spoken Latin prior to regional fragmentation.

Phonology

Vowels

Monophthongs

Diphthong

The only phonemic diphthong was ...

* Romance copula

In some of the Romance languages the copula, the equivalent of the verb ''to be'' in English, is relatively complex compared to its counterparts in other languages. A copula is a word that links the subject of a sentence with a predicate (a ...

* Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

* Reichenau Glosses The Reichenau Glossary is a collection of Latin glosses likely compiled in the 8th century in northern France to assist local clergy in understanding certain words or expressions found in the Vulgate Bible.

Background

Over the centuries Jerome’ ...

* Oaths of Strasbourg

The Oaths of Strasbourg were a military pact made on 14 February 842 by Charles the Bald and Louis the German against their older brother Lothair I, the designated heir of Louis the Pious, the successor of Charlemagne. One year later the Trea ...

* Veronese Riddle

The Veronese Riddle ( it, Indovinello veronese) is a riddle written in late Vulgar Latin, or early Romance, on the Verona Orational, probably in the 8th or early 9th century, by a Christian monk from Verona, in northern Italy. It is an example o ...

* Glosas Emilianenses

The Glosas Emilianenses (Spanish for "glosses of he monastery of SaintMillán/Emilianus") are glosses written in the 10th or 11th century to a 9th-century Latin codex. These marginalia are important as early examples of writing in a form of Ro ...

* Gallo-Romance

The Gallo-Romance branch of the Romance languages includes in the narrowest sense the Langues d'oïl and Franco-Provençal. However, other definitions are far broader, variously encompassing the Occitano-Romance, Gallo-Italic, and Rhaeto-Roman ...

* Gallo-Italic

The Gallo-Italic, Gallo-Italian, Gallo-Cisalpine or simply Cisalpine languages constitute the majority of the Romance languages of northern Italy. They are Piedmontese, Lombard, Emilian, Ligurian, and Romagnol. Although most publications def ...

* Ibero-Roman

The Iberian Romance, Ibero-Romance or sometimes Iberian languagesIberian languages is also used as a more inclusive term for all languages spoken on the Iberian Peninsula, which in antiquity included the non-Indo-European Iberian language. are a ...

* Common Romanian

Common Romanian ( ro, româna comună), also known as Ancient Romanian (), or Proto-Romanian (), is a comparatively reconstructed Romance language evolved from Vulgar Latin and considered to have been spoken by the ancestors of today's Romania ...

* Daco-Roman

The term Daco-Roman describes the Romanized culture of Dacia under the rule of the Roman Empire.

Etymology

The Daco-Roman mixing theory, as an origin for the Romanian people, was formulated by the earliest Romanian scholars, beginning with Doso ...

* Thraco-Roman The term Thraco-Roman describes the Romanization (cultural), Romanized culture of Thracians under the rule of the Roman Empire.

The Odrysian kingdom of Thrace became a Roman client kingdom c. 20 BC, while the Greek city-states on the Black Sea coas ...

History of specific Romance languages

* Sicilian *Catalan phonology

The phonology of Catalan, a Romance language, has a certain degree of dialectal variation. Although there are two standard varieties, one based on Central Eastern dialect and another one based on South-Western or Valencian dialect, this articl ...

* History of French

French is a Romance language (meaning that it is descended primarily from Vulgar Latin) that specifically is classified under the Gallo-Romance languages.

The discussion of the history of a language is typically divided into "external history ...

* History of Italian

Italian (''italiano'' or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin. Spoken by about 85 m ...

* History of Portuguese

* History of the Spanish language

The language known today as Spanish is derived from a dialect of spoken Latin, which was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the Romans after their occupation of the peninsula that started in the late 3rd century BC. Influenced by the peninsul ...

* History of the Romanian language

The history of the Romanian language started in Roman provinces north of the Jireček Line in Classical antiquity. Between 6th and 8th century AD, following the accumulated tendencies inherited from the vernacular spoken in this large area and, to ...

* Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

References

Citations

Works consulted

; General * * * * * * Carlton, Charles Merritt. 1973. ''A linguistic analysis of a collection of Late Latin documents composed in Ravenna between A.D. 445–700''. The Hague: Mouton. * * * * * Gouvert, Xavier. 2016. Du protoitalique au protoroman: Deux problèmes de reconstruction phonologique. In: Buchi, Éva & Schweickard, Wolfgang (eds.), ''Dictionnaire étymologique roman'' 2, 27–51. Berlin: De Gruyter. * * * * * * Leppänen, V., & Alho, T. 2018. On the mergers of Latin close-mid vowels. Transactions of the Philological Society 116. 460–483. * * * Nandris, Grigore. 1951. The development and structure of Rumanian. ''The Slavonic and East European Review'', 30. 7-39. * * Pei, Mario. 1941. ''The Italian language''. New York: Columbia University Press. * Pei, Mario & Gaeng, Paul A. 1976. ''The story of Latin and the Romance languages''. New York: Harker & Row. * * * * Treadgold, Warren. 1997. ''A history of the Byzantine state and society''. Stanford University Press. * * * * * *Transitions to Romance languages

; To Romance in general * * * Ledgeway, Adam (2012). ''From Latin to Romance: Morphosyntactic Typology and Change''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. * * (esp. parts 1 & 2, ''Latin and the Making of the Romance Languages''; ''The Transition from Latin to the Romance Languages'') * * ; To French * * * * * ; To Italian * * ; To Spanish * * * * ; To Portuguese * * * ; To Occitan * ; To Sardinian *Further reading

* Adams, James Noel. 1976. ''The Text and Language of a Vulgar Latin Chronicle (Anonymus Valesianus II).'' London: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies. * --. 1977. ''The Vulgar Latin of the letters of Claudius Terentianus.'' Manchester, UK: Manchester Univ. Press. * --. 2013. ''Social Variation and the Latin Language.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Burghini, Julia, and Javier Uría. 2015. "Some neglected evidence on Vulgar Latin 'glide suppression': Consentius, 27.17.20 N." ''Glotta; Zeitschrift Für Griechische Und Lateinische Sprache'' 91: 15–26. . * Jensen, Frede. 1972. ''From Vulgar Latin to Old Provençal.'' Chapel Hill:University of North Carolina Press

The University of North Carolina Press (or UNC Press), founded in 1922, is a university press that is part of the University of North Carolina. It was the first university press founded in the Southern United States. It is a member of the Ass ...

.

* Lakoff, Robin Tolmach. 2006. Vulgar Latin: Comparative Castration (and Comparative Theories of Syntax). ''Style'' 40, nos. 1–2: 56–61. .

* Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1970. ''From Vulgar Latin to Old French: An Introduction to the Study of the Old French Language.'' Detroit: Wayne State University Press

Wayne State University Press (or WSU Press) is a university press that is part of Wayne State University. It publishes under its own name and also the imprints Painted Turtle and Great Lakes Books Series.

History

The Press has strong subjec ...

.

* Scarpanti, Edoardo. 2012. ''Saggi linguistici sul latino volgare.'' Mantova: Universitas Studiorum. .

* Weiss, Michael. 2009. ''Outline of the historical and comparative grammar of Latin.'' Ann Arbor, MI: Beechstave.

*

External links

* * * {{Authority control Latin language in ancient Rome Forms of Latin Gallo-Roman culture