Université De Paris on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

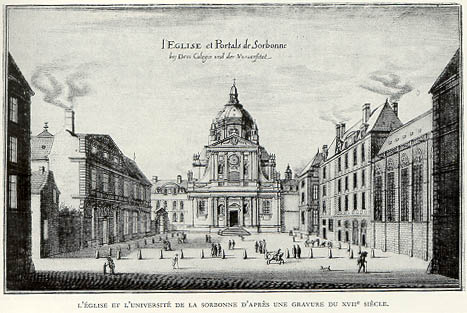

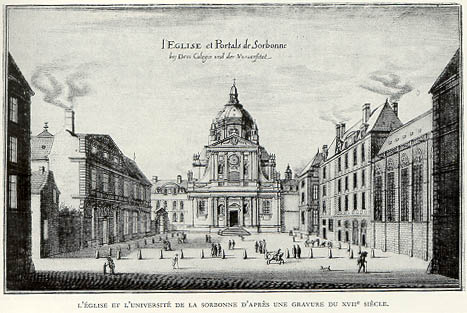

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated with the cathedral school of Notre Dame de Paris, it was considered the second-oldest university in Europe. Haskins, C. H.: ''The Rise of Universities'', Henry Holt and Company, 1923, p. 292.

Officially

Three schools were especially famous in Paris: the ''palatine or palace school'', the ''school of Notre-Dame'', and that of

Three schools were especially famous in Paris: the ''palatine or palace school'', the ''school of Notre-Dame'', and that of  The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their  To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to Matthew Paris,

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to Matthew Paris,

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate,

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate,

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of Honorius III in 1222. Later, they formed a distinct body. By 1249, the four nations existed with their procurators, their rights (more or less well-defined), and their keen rivalries: the nations were the French, English, Normans, and Picards. After the Hundred Years' War, the English nation was replaced by the Germanic. The four nations constituted the faculty of arts or letters.

The territories covered by the four nations were:

* French nation: all the

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of Honorius III in 1222. Later, they formed a distinct body. By 1249, the four nations existed with their procurators, their rights (more or less well-defined), and their keen rivalries: the nations were the French, English, Normans, and Picards. After the Hundred Years' War, the English nation was replaced by the Germanic. The four nations constituted the faculty of arts or letters.

The territories covered by the four nations were:

* French nation: all the

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if

In the fifteenth century, Guillaume d'Estouteville, a cardinal and Apostolic legate, reformed the university, correcting its perceived abuses and introducing various modifications. This reform was less an innovation than a recall to observance of the old rules, as was the reform of 1600, undertaken by the royal government with regard to the three higher faculties. Nonetheless, and as to the faculty of arts, the reform of 1600 introduced the study of Greek, of French poets and orators, and of additional classical figures like

In the fifteenth century, Guillaume d'Estouteville, a cardinal and Apostolic legate, reformed the university, correcting its perceived abuses and introducing various modifications. This reform was less an innovation than a recall to observance of the old rules, as was the reform of 1600, undertaken by the royal government with regard to the three higher faculties. Nonetheless, and as to the faculty of arts, the reform of 1600 introduced the study of Greek, of French poets and orators, and of additional classical figures like

The ancient university disappeared with the

The ancient university disappeared with the

File:Francisco_de_Zurbar%C3%A1n_-_The_Prayer_of_St._Bonaventura_about_the_Selection_of_the_New_Pope_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg, Bonaventure

File:Guizot,_Fran%C3%A7ois_-_2.jpg,

File:John Calvin - Young.jpg,

* Rodolfo Robles, physician

* Albert Simard, physician, activist during and post WWII.

* Carlos Alvarado-Larroucau, writer

* Paul Biya, President of Cameroon

* Jean-François Delmas, archivist, Director of the

Paul Nadar - Henri Becquerel.jpg,

Gabriel Lippmann2.jpg, Gabriel Lippmann

Jean Perrin 1926.jpg,

''La Sorbonne: ses origines, sa bibliothèque, les débuts de l'imprimerie à Paris et la succession de Richelieu d'après des documents inédits, 2. édition''

Paris: L. Willem, 1875 * Leutrat, Jean-Louis: ''De l'Université aux Universités'' (From the University to the Universities), Paris: Association des Universités de Paris, 1997 * Post, Gaines: ''The Papacy and the Rise of Universities'' Ed. with a Preface by William J. Courtenay. Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 54 Leiden: Brill, 2017. *Rivé, Phillipe: ''La Sorbonne et sa reconstruction'' (The Sorbonne and its Reconstruction), Lyon: La Manufacture, 1987 * Tuilier, André: ''Histoire de l'Université de Paris et de la Sorbonne'' (History of the University of Paris and of the Sorbonne), in 2 volumes (From the Origins to Richelieu, From Louis XIV to the Crisis of 1968), Paris: Nouvelle Librairie de France, 1997 * Verger, Jacques: ''Histoire des Universités en France'' (History of French Universities), Toulouse: Editions Privat, 1986 * Traver, Andrew G. 'Rewriting History?: The Parisian Secular Masters' ''Apologia'' of 1254,' ''History of Universities'' 15 (1997-9): 9-45.

Chancellerie des Universités de Paris

(official homepage)

Projet Studium Parisiense

database of members of the University of Paris from the 11th to 16th centuries

Liste des Universités de Paris et d'Ile-de-France : nom, adresse, cours, diplômes...

{{DEFAULTSORT:University Of Paris 12th-century establishments in France 1150 establishments in Europe 1150s establishments in France 1970 disestablishments in France Philip II of France Paris, University of Defunct educational institutions

charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

ed in 1200 by King Philip II of France and recognised in 1215 by Pope Innocent III, it was later often nicknamed after its theological College of Sorbonne, in turn founded by Robert de Sorbon and chartered by French King Saint Louis around 1257.

Internationally highly reputed for its academic performance in the humanities ever since the Middle Ages – notably in theology and philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

– it introduced several academic standards and traditions that have endured ever since and spread internationally, such as doctoral degrees and student nations. Vast numbers of popes

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

, royalty, scientists, and intellectuals were educated at the University of Paris. A few of the colleges of the time are still visible close to the Panthéon and Jardin du Luxembourg: Collège des Bernardins (18 rue de Poissy, 5th arr.), Hôtel de Cluny (6 Place Paul Painlève, 5th arr.), Collège Sainte-Barbe (4 rue Valette, 5th arr.), Collège d'Harcourt (44 Boulevard Saint-Michel, 6th arr.), and Cordeliers (21 rue École de Médecine, 6th arr.).

In 1793, during the French Revolution, the university was closed, and by Item 27 of the Revolutionary Convention, the college endowments and buildings were sold. A new University of France replaced it in 1806 with four independent faculties: the Faculty of Humanities (french: Faculté des Lettres), the Faculty of Law

A faculty is a division within a university or college comprising one subject area or a group of related subject areas, possibly also delimited by level (e.g. undergraduate). In American usage such divisions are generally referred to as colleges ...

(later including Economics), the Faculty of Science, the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Theology (closed in 1885).

In 1970, following the civil unrest of May 1968, the university was divided into 13 autonomous universities.

History

Origins

In 1150, the future University of Paris was a student-teacher corporation operating as an annex of the Notre-Dame cathedral school. The earliest historical reference to it is found in Matthew Paris' reference to the studies of his own teacher (an abbot of St. Albans) and his acceptance into "the fellowship of the elect Masters" there in about 1170, and it is known that Lotario dei Conti di Segni, the future Pope Innocent III, completed his studies there in 1182 at the age of 21. The corporation was formally recognised as an "''Universitas

''Universitas'' is a Latin word meaning "the whole, total, the universe, the world", or in Roman law a society or corporation; the latter sense is where the word university is derived from.

Universitas may also refer to:

* Universitas 21, an in ...

''" in an edict by King Philippe-Auguste in 1200: in it, among other accommodations granted to future students, he allowed the corporation to operate under ecclesiastic law which would be governed by the elders of the Notre-Dame Cathedral school, and assured all those completing courses there that they would be granted a diploma.

The university had four faculties: Arts, Medicine, Law, and Theology. The Faculty of Arts was the lowest in rank, but also the largest, as students had to graduate there in order to be admitted to one of the higher faculties. The students were divided into four '' nationes'' according to language or regional origin: France, Normandy, Picardy, and England. The last came to be known as the ''Alemannian'' (German) nation. Recruitment to each nation was wider than the names might imply: the English-German nation included students from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe.

The faculty and nation system of the University of Paris (along with that of the University of Bologna) became the model for all later medieval universities. Under the governance of the Church, students wore robes and shaved the tops of their heads in tonsure, to signify they were under the protection of the church. Students followed the rules and laws of the Church and were not subject to the king's laws or courts. This presented problems for the city of Paris, as students ran wild, and its official had to appeal to Church courts for justice. Students were often very young, entering the school at 13 or 14 years of age and staying for six to 12 years.

12th century: Organisation

Three schools were especially famous in Paris: the ''palatine or palace school'', the ''school of Notre-Dame'', and that of

Three schools were especially famous in Paris: the ''palatine or palace school'', the ''school of Notre-Dame'', and that of Sainte-Geneviève Abbey

The Abbey of Saint Genevieve (French: ''Abbaye Sainte-Geneviève'') was a monastery in Paris. Reportedly built by Clovis, King of the Franks in 502, it became a centre of religious scholarship in the Middle Ages. It was suppressed at the time of t ...

. The decline of royalty brought about the decline of the first. The other two were ancient but did not have much visibility in the early centuries. The glory of the palatine school doubtless eclipsed theirs, until it completely gave way to them. These two centres were much frequented and many of their masters were esteemed for their learning. The first renowned professor at the school of Ste-Geneviève was Hubold, who lived in the tenth century. Not content with the courses at Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

, he continued his studies at Paris, entered or allied himself with the chapter of Ste-Geneviève, and attracted many pupils via his teaching. Distinguished professors from the school of Notre-Dame in the eleventh century include Lambert, disciple of Fulbert of Chartres; Drogo of Paris

Drogo (french: Dreux or ; it, Drogone) may refer to:

People

:''Ordered chronologically.''

*Drogo of Champagne (670–708), Duke of Champagne

*Drogo (mayor of the palace) (c. 730–?), Merovingian mayor of the palace of Austrasia

*Drogo of Metz ( ...

; Manegold of Germany Manegold of Lautenbach (c. 1030 – c. 1103) was a religious and polemical writer and Augustinian canon from Alsace, active mostly as a teacher in south-west Germany. William of Champeaux may have been one of his pupils, but this is disputed. He was ...

; and Anselm of Laon. These two schools attracted scholars from every country and produced many illustrious men, among whom were: St. Stanislaus of Szczepanów, Bishop of Kraków; Gebbard, Archbishop of Salzburg

Blessed Gebhard von Salzburg ( 101015 June 1088), also occasionally known as Gebhard of Sussex, was Archbishop of Salzburg from 1060 until his death. He was one of the fiercest opponents of King Henry IV of Germany during the Investiture Controv ...

; St. Stephen, third Abbot of Cîteaux; Robert d'Arbrissel, founder of the Abbey of Fontevrault

The Royal Abbey of Our Lady of Fontevraud or Fontevrault (in French: ''abbaye de Fontevraud'') was a monastery in the village of Fontevraud-l'Abbaye, near Chinon, in the former French duchy of Anjou. It was founded in 1101 by the itinerant preache ...

etc. Three other men who added prestige to the schools of Notre-Dame and Ste-Geneviève were William of Champeaux, Abélard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed desc ...

, and Peter Lombard.

Humanistic instruction comprised grammar, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

, dialectics

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to ...

, arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

, geometry, music, and astronomy ( trivium and quadrivium). To the higher instruction belonged dogmatic and moral theology, whose source was the Scriptures and the Patristic Fathers. It was completed by the study of Canon law. The School of Saint-Victor arose to rival those of Notre-Dame and Ste-Geneviève. It was founded by William of Champeaux when he withdrew to the Abbey of Saint-Victor. Its most famous professors are Hugh of St. Victor

Hugh of Saint Victor ( 1096 – 11 February 1141), was a Saxon canon regular and a leading theologian and writer on mystical theology.

Life

As with many medieval figures, little is known about Hugh's early life. He was probably born in the 1090s ...

and Richard of St. Victor

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

.

The plan of studies expanded in the schools of Paris, as it did elsewhere. A Bolognese

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nati ...

compendium of canon law called the '' Decretum Gratiani'' brought about a division of the theology department. Hitherto the discipline of the Church had not been separate from so-called theology; they were studied together under the same professor. But this vast collection necessitated a special course, which was undertaken first at Bologna, where Roman law was taught. In France, first Orléans and then Paris erected chairs of canon law. Before the end of the twelfth century, the Decretals of Gerard La Pucelle, Mathieu d'Angers

Mathieu is both a surname and a given name. Notable people with the name include:

Surname

* André Mathieu (1929–1968), Canadian pianist and composer

* Anselme Mathieu (1828–1895), French Provençal poet

* Claude-Louis Mathieu (1783–1875 ...

, and Anselm (or Anselle) of Paris, were added to the Decretum Gratiani. However, civil law was not included at Paris. In the twelfth century, medicine began to be publicly taught at Paris: the first professor of medicine in Paris records is Hugo, ''physicus excellens qui quadrivium docuit''.

Professors were required to have measurable knowledge and be appointed by the university. Applicants had to be assessed by examination; if successful, the examiner, who was the head of the school, and known as ''scholasticus'', ''capiscol'', and ''chancellor,'' appointed an individual to teach. This was called the licence

A license (or licence) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another party (licensee) as an element of an agreeme ...

or faculty to teach. The licence had to be granted freely. No one could teach without it; on the other hand, the examiner could not refuse to award it when the applicant deserved it.

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their

The school of Saint-Victor, under the abbey, conferred the licence in its own right; the school of Notre-Dame depended on the diocese, that of Ste-Geneviève on the abbey or chapter. The diocese and the abbey or chapter, through their chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, gave professorial investiture in their respective territories where they had jurisdiction. Besides Notre-Dame, Ste-Geneviève, and Saint-Victor, there were several schools on the "Island" and on the "Mount". "Whoever", says Crevier "had the right to teach might open a school where he pleased, provided it was not in the vicinity of a principal school." Thus a certain Adam, who was of English origin, kept his "near the Petit Pont"; another Adam, Parisian by birth, "taught at the Grand Pont

Grand may refer to:

People with the name

* Grand (surname)

* Grand L. Bush (born 1955), American actor

* Grand Mixer DXT, American turntablist

* Grand Puba (born 1966), American rapper

Places

* Grand, Oklahoma

* Grand, Vosges, village and commun ...

which is called the Pont-au-Change

The Pont au Change is a bridge over the Seine River in Paris, France. The bridge is located at the border between the 1st arrondissement of Paris, first and 4th arrondissement of Paris, fourth arrondissements. It connects the Île de la Cité fro ...

" (''Hist. de l'Univers. de Paris,'' I, 272).

The number of students in the school of the capital grew constantly, so that lodgings were insufficient. French students included princes of the blood, sons of the nobility, and ranking gentry. The courses at Paris were considered so necessary as a completion of studies that many foreigners flocked to them. Popes Celestine II, Adrian IV and Innocent III studied at Paris, and Alexander III sent his nephews there. Noted German and English students included Otto of Freisingen, Cardinal Conrad, Archbishop of Mainz

Conrad of Wittelsbach (c. 1120/1125 – 25 October 1200) was the Archbishop of Mainz (as Conrad I) and Archchancellor of Germany from 20 June 1161 to 1165 and again from 1183 to his death. He was also a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

The ...

, St. Thomas of Canterbury

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

, and John of Salisbury; while Ste-Geneviève became practically the seminary for Denmark. The chroniclers of the time called Paris the city of letters par excellence, placing it above Athens, Alexandria, Rome, and other cities: "At that time, there flourished at Paris philosophy and all branches of learning, and there the seven arts were studied and held in such esteem as they never were at Athens, Egypt, Rome, or elsewhere in the world." ("Les gestes de Philippe-Auguste"). Poets extolled the university in their verses, comparing it to all that was greatest, noblest, and most valuable in the world.

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to Matthew Paris,

To allow poor students to study the first college des dix-Huit was founded by a knight returning from Jerusalem called Josse of London for 18 scholars who received lodgings and 12 pence or denarii a month.

As the university developed, it became more institutionalized. First, the professors formed an association, for according to Matthew Paris, John of Celles

John of Wallingford (died 1214), also known as John de Cella, was Abbot of St Albans Abbey in the English county of Hertfordshire from 1195 to his death in 1214. He was previously prior of Holy Trinity Priory at Wallingford in Berkshire (now O ...

, twenty-first Abbot of St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

, England, was admitted as a member of the teaching corps of Paris after he had followed the courses (''Vita Joannis I, XXI, abbat. S. Alban''). The masters, as well as the students, were divided according to national origin,. Alban wrote that Henry II, King of England, in his difficulties with St. Thomas of Canterbury, wanted to submit his cause to a tribunal composed of professors of Paris, chosen from various provinces (Hist. major, Henry II, to end of 1169). This was likely the start of the division according to "nations," which was later to play an important part in the university. Celestine III ruled that both professors and students had the privilege of being subject only to the ecclesiastical courts, not to civil courts.

The three schools: Notre-Dame, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Victor, may be regarded as the triple cradle of the ''Universitas scholarium'', which included masters and students; hence the name ''University''. Henry Denifle

Henry Denifle, in German Heinrich Seuse Denifle (January 16, 1844 in Imst, Tyrol – June 10, 1905 in Munich), was an Austrian paleographer and historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an auth ...

and some others hold that this honour is exclusive to the school of Notre-Dame (Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis), but the reasons do not seem convincing. He excludes Saint-Victor because, at the request of the abbot and the religious of Saint-Victor, Gregory IX in 1237 authorized them to resume the interrupted teaching of theology. But the university was largely founded about 1208, as is shown by a Bull of Innocent III. Consequently, the schools of Saint-Victor might well have contributed to its formation. Secondly, Denifle excludes the schools of Ste-Geneviève because there had been no interruption in the teaching of the liberal arts. This is debatable and through the period, theology was taught. The chancellor of Ste-Geneviève continued to give degrees in arts, something he would have ceased if his abbey had no part in the university organization.

13th–14th century: Expansion

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate,

In 1200, King Philip II issued a diploma "for the security of the scholars of Paris," which affirmed that students were subject only to ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The provost and other officers were forbidden to arrest a student for any offence, unless to transfer him to ecclesiastical authority. The king's officers could not intervene with any member unless having a mandate from an ecclesiastical authority. His action followed a violent incident between students and officers outside the city walls at a pub.

In 1215, the Apostolic legate, Robert de Courçon

Robert of Courson or Courçon (also written de Curson, or Curzon, ''Princes of the Church'', p. 173.) ( 1160/1170 – 1219) was a scholar at the University of Paris and later a cardinal and papal legate.

Life

Robert of Courson was born in Engla ...

, issued new rules governing who could become a professor. To teach the arts, a candidate had to be at least twenty-one, to have studied these arts at least six years, and to take an engagement as professor for at least two years. For a chair in theology, the candidate had to be thirty years of age, with eight years of theological studies, of which the last three years were devoted to special courses of lectures in preparation for the mastership. These studies had to be made in the local schools under the direction of a master. In Paris, one was regarded as a scholar only by studies with particular masters. Lastly, purity of morals was as important as reading. The licence was granted, according to custom, gratuitously, without oath or condition. Masters and students were permitted to unite, even by oath, in defence of their rights, when they could not otherwise obtain justice in serious matters. No mention is made either of law or of medicine, probably because these sciences were less prominent.

In 1229, a denial of justice by the queen led to suspension of the courses. The pope intervened with a Bull that began with lavish praise of the university: "Paris", said Gregory IX, "mother of the sciences, is another Cariath-Sepher, city of letters". He commissioned the Bishops of Le Mans and Senlis and the Archdeacon of Châlons to negotiate with the French Court for the restoration of the university, but by the end of 1230 they had accomplished nothing. Gregory IX then addressed a Bull of 1231 to the masters and scholars of Paris. Not only did he settle the dispute, he empowered the university to frame statutes concerning the discipline of the schools, the method of instruction, the defence of theses, the costume of the professors, and the obsequies of masters and students (expanding upon Robert de Courçon's statutes). Most importantly, the pope granted the university the right to suspend its courses, if justice were denied it, until it should receive full satisfaction.

The pope authorized Pierre Le Mangeur to collect a moderate fee for the conferring of the license of professorship. Also, for the first time, the scholars had to pay tuition fees for their education: two sous weekly, to be deposited in the common fund.

Rector

The university was organized as follows: at the head of the teaching body was arector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

. The office was elective and of short duration; at first it was limited to four or six weeks. Simon de Brion

Pope Martin IV ( la, Martinus IV; c. 1210/1220 – 28 March 1285), born Simon de Brion, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 February 1281 to his death on 28 March 1285. He was the last French pope to have ...

, legate of the Holy See in France, realizing that such frequent changes caused serious inconvenience, decided that the rectorate should last three months, and this rule was observed for three years. Then the term was lengthened to one, two, and sometimes three years. The right of election belonged to the procurators of the four nations. Henry of Unna Henry of Unna was proctor of the University of Paris in the 14th century, beginning his term on January 13, 1340. He was preceded as proctor by Conrad of Megenberg. A native of Denmark, Henry of Unna's term as proctor extended until February 10, 13 ...

was proctor

Proctor (a variant of ''procurator'') is a person who takes charge of, or acts for, another.

The title is used in England and some other English-speaking countries in three principal contexts:

* In law, a proctor is a historical class of lawye ...

of the University of Paris in the 14th century, beginning his term on January 13, 1340.

Four "nations"

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of Honorius III in 1222. Later, they formed a distinct body. By 1249, the four nations existed with their procurators, their rights (more or less well-defined), and their keen rivalries: the nations were the French, English, Normans, and Picards. After the Hundred Years' War, the English nation was replaced by the Germanic. The four nations constituted the faculty of arts or letters.

The territories covered by the four nations were:

* French nation: all the

The "nations" appeared in the second half of the twelfth century. They were mentioned in the Bull of Honorius III in 1222. Later, they formed a distinct body. By 1249, the four nations existed with their procurators, their rights (more or less well-defined), and their keen rivalries: the nations were the French, English, Normans, and Picards. After the Hundred Years' War, the English nation was replaced by the Germanic. The four nations constituted the faculty of arts or letters.

The territories covered by the four nations were:

* French nation: all the Romance-speaking

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

parts of Europe except those included within the Norman and Picard nations

* English nation (renamed 'German nation' after the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

): the British Isles, the Germanic-speaking parts of continental Europe (except those included within the Picard nation), and the Slavic-speaking parts of Europe. The majority of students within that nation came from Germany and Scotland, and when it was renamed 'German nation' it was also sometimes called ''natio Germanorum et Scotorum'' ("nation of the Germans and Scots").

* Norman nation: the ecclesiastical province of Rouen, which corresponded approximately to the Duchy of Normandy. This was a Romance-speaking territory, but it was not included within the French nation.

* Picard nation: the Romance-speaking bishoprics of Beauvais

Beauvais ( , ; pcd, Bieuvais) is a city and commune in northern France, and prefecture of the Oise département, in the Hauts-de-France region, north of Paris.

The commune of Beauvais had a population of 56,020 , making it the most populous ...

, Noyon, Amiens, Laon, and Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

; the bilingual (Romance and Germanic-speaking) bishoprics of Thérouanne, Cambrai

Cambrai (, ; pcd, Kimbré; nl, Kamerijk), formerly Cambray and historically in English Camerick or Camericke, is a city in the Nord (French department), Nord Departments of France, department and in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, regio ...

, and Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Euromet ...

; a large part of the bilingual bishopric of Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far from b ...

; and the southernmost part of the Germanic-speaking bishopric of Utrecht (the part of that bishopric located south of the river Meuse; the rest of the bishopric north of the Meuse belonged to the English nation). It was estimated that about half of the students in the Picard nation were Romance-speakers ( Picard and Walloon), and the other half were Germanic-speakers ( West Flemish, East Flemish, Brabantian and Limburgish

Limburgish ( li, Limburgs or ; nl, Limburgs ; german: Limburgisch ; french: Limbourgeois ), also called Limburgan, Limburgian, or Limburgic, is a West Germanic language spoken in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg (Netherlands), L ...

dialects).

Faculties

To classify professors' knowledge, the schools of Paris gradually divided into faculties. Professors of the same science were brought into closer contact until the community of rights and interests cemented the union and made them distinct groups. The faculty of medicine seems to have been the last to form. But the four faculties were already formally established by 1254, when the university described in a letter "theology, jurisprudence, medicine, and rational, natural, and moral philosophy". The masters of theology often set the example for the other faculties—e.g., they were the first to adopt an official seal. The faculties of theology, canon law, and medicine, were called "superior faculties". The title of " Dean" as designating the head of a faculty, came into use by 1268 in the faculties of law and medicine, and by 1296 in the faculty of theology. It seems that at first the deans were the oldest masters. The faculty of arts continued to have four procurators of its four nations and its head was the rector. As the faculties became more fully organized, the division into four nations partially disappeared for theology, law and medicine, though it continued in arts. Eventually the superior faculties included only doctors, leaving the bachelors to the faculty of arts. At this period, therefore, the university had two principal degrees, the baccalaureate and the doctorate. It was not until much later that the licentiate and the DEA became intermediate degrees.Colleges

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if

The scattered condition of the scholars in Paris often made lodging difficult. Some students rented rooms from townspeople, who often exacted high rates while the students demanded lower. This tension between scholars and citizens would have developed into a sort of civil war if Robert de Courçon

Robert of Courson or Courçon (also written de Curson, or Curzon, ''Princes of the Church'', p. 173.) ( 1160/1170 – 1219) was a scholar at the University of Paris and later a cardinal and papal legate.

Life

Robert of Courson was born in Engla ...

had not found the remedy of taxation. It was upheld in the Bull of Gregory IX of 1231, but with an important modification: its exercise was to be shared with the citizens. The aim was to offer the students a shelter where they would fear neither annoyance from the owners nor the dangers of the world. Thus were founded the colleges (colligere, to assemble); meaning not centers of instruction, but simple student boarding-houses. Each had a special goal, being established for students of the same nationality or the same science. Often, masters lived in each college and oversaw its activities.

Four colleges appeared in the 12th century; they became more numerous in the 13th, including Collège d'Harcourt

In France, secondary education is in two stages:

* ''Collèges'' () cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15.

* ''Lycées'' () provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between ...

(1280) and the Collège de Sorbonne (1257). Thus the University of Paris assumed its basic form. It was composed of seven groups, the four nations of the faculty of arts, and the three superior faculties of theology, law, and medicine. Men who had studied at Paris became an increasing presence in the high ranks of the Church hierarchy; eventually, students at the University of Paris saw it as a right that they would be eligible to benefices. Church officials such as St. Louis and Clement IV lavishly praised the university.

Besides the famous Collège de Sorbonne, other ''collegia'' provided housing and meals to students, sometimes for those of the same geographical origin in a more restricted sense than that represented by the nations. There were 8 or 9 ''collegia'' for foreign students: the oldest one was the Danish college, the ''Collegium danicum'' or ''dacicum'', founded in 1257. Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

students could, during the 13th and 14th centuries, live in one of three Swedish colleges, the ''Collegium Upsaliense'', the ''Collegium Scarense'' or the ''Collegium Lincopense'', named after the Swedish dioceses of Uppsala, Skara and Linköping.

The '' Collège de Navarre'' was founded in 1305, originally aimed at students from Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

, but due to its size, wealth, and the links between the crowns of France and Navarre, it quickly accepted students from other nations. The establishment of the College of Navarre was a turning point in the university's history: Navarra was the first college to offer teaching to its students, which at the time set it apart from all previous colleges, founded as charitable institutions that provided lodging, but no tuition. Navarre's model combining lodging and tuition would be reproduced by other colleges, both in Paris and other universities.

The German College, ''Collegium alemanicum'' is mentioned as early as 1345, the Scots college or ''Collegium scoticum'' was founded in 1325. The Lombard college or ''Collegium lombardicum'' was founded in the 1330s. The ''Collegium constantinopolitanum'' was, according to a tradition, founded in the 13th century to facilitate a merging of the eastern and western churches. It was later reorganized as a French institution, the ''Collège de la Marche-Winville''. The Collège de Montaigu

The Collège de Montaigu was one of the constituent colleges of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Paris.

History

The college, originally called Collège des Aicelins, was founded in 1314 by Gilles I Aycelin de Montaigu, Archbishop of Narbo ...

was founded by the Archbishop of Rouen in the 14th century, and reformed in the 15th century by the humanist Jan Standonck

Jan Standonck (or ''Jean Standonk''; 16 August 1453 – 5 February 1504) was a Flemish priest, Scholastic, and reformer.

He was part of the great movement for reform in the 15th-century French church. His approach was to reform the recruitment ...

, when it attracted reformers from within the Roman Catholic Church (such as Erasmus and Ignatius of Loyola) and those who subsequently became Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

(John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

and John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

).

At this time, the university also went the controversy of the condemnations of 1210–1277.

The Irish College in Paris originated in 1578 with students dispersed between Collège Montaigu, Collège de Boncourt, and the Collège de Navarre, in 1677 it was awarded possession of the Collège des Lombards. A new Irish College was built in 1769 in rue du Cheval Vert (now rue des Irlandais), which exists today as the Irish Chaplaincy and Cultural centre.

15th–18th century: Influence in France and Europe

In the fifteenth century, Guillaume d'Estouteville, a cardinal and Apostolic legate, reformed the university, correcting its perceived abuses and introducing various modifications. This reform was less an innovation than a recall to observance of the old rules, as was the reform of 1600, undertaken by the royal government with regard to the three higher faculties. Nonetheless, and as to the faculty of arts, the reform of 1600 introduced the study of Greek, of French poets and orators, and of additional classical figures like

In the fifteenth century, Guillaume d'Estouteville, a cardinal and Apostolic legate, reformed the university, correcting its perceived abuses and introducing various modifications. This reform was less an innovation than a recall to observance of the old rules, as was the reform of 1600, undertaken by the royal government with regard to the three higher faculties. Nonetheless, and as to the faculty of arts, the reform of 1600 introduced the study of Greek, of French poets and orators, and of additional classical figures like Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

, Plato, Demosthenes, Cicero, Virgil, and Sallust. The prohibition from teaching civil law was never well observed at Paris, but in 1679 Louis XIV officially authorized the teaching of civil law in the faculty of decretals. The "faculty of law" hence replaced the "faculty of decretals". The colleges meantime had multiplied; those of Cardinal Le-Moine and Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

were founded in the fourteenth century. The Hundred Years' War was fatal to these establishments, but the university set about remedying the injury.

Besides its teaching, the University of Paris played an important part in several disputes: in the Church, during the Great Schism; in the councils, in dealing with heresies and divisions; in the State, during national crises. Under the domination of England it played a role in the trial of Joan of Arc.

Proud of its rights and privileges, the University of Paris fought energetically to maintain them, hence the long struggle against the mendicant orders on academic as well as on religious grounds. Hence also the shorter conflict against the Jesuits, who claimed by word and action a share in its teaching. It made extensive use of its right to decide administratively according to occasion and necessity. In some instances it openly endorsed the censures of the faculty of theology and pronounced condemnation in its own name, as in the case of the Flagellants

Flagellants are practitioners of a form of mortification of the flesh by whipping their skin with various instruments of penance. Many Christian confraternities of penitents have flagellants, who beat themselves, both in the privacy of their dwe ...

.

Its patriotism was especially manifested on two occasions. During the captivity of King John, when Paris was given over to factions, the university sought to restore peace; and under Louis XIV, when the Spaniards crossed the Somme and threatened the capital, it placed two hundred men at the king's disposal and offered the Master of Arts degree gratuitously to scholars who should present certificates of service in the army (Jourdain, ''Hist. de l'Univers. de Paris au XVIIe et XVIIIe siècle'', 132–34; ''Archiv. du ministère de l'instruction publique'').

1793: Abolition by the French Revolution

The ancient university disappeared with the

The ancient university disappeared with the ancien régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

{{disambig ...

in the French Revolution. On 15 September 1793, petitioned by the Department of Paris and several departmental groups, the National Convention decided that independently of the primary schools, "there should be established in the Republic three progressive degrees of instruction; the first for the knowledge indispensable to artisans and workmen of all kinds; the second for further knowledge necessary to those intending to embrace the other professions of society; and the third for those branches of instruction the study of which is not within the reach of all men".Measures were to be taken immediately: "For means of execution the department and the municipality of Paris are authorized to consult with the Committee of Public Instruction of the National Convention, in order that these establishments shall be put in action by 1 November next, and consequently colleges now in operation and the faculties of theology, medicine, arts, and law are suppressed throughout the Republic". This was the death-sentence of the university. It was not to be restored after the Revolution had subsided, no more than those of the provinces.

1806–1968: Re-establishment

The university was re-established byNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

on 1 May 1806. All the faculties were replaced by a single centre, the University of France. The decree of 17 March 1808 created five distinct faculties: Law, Medicine, Letters/Humanities, Sciences, and Theology; traditionally, Letters and Sciences had been grouped together into one faculty, that of "Arts". After a century, people recognized that the new system was less favourable to study. The defeat of 1870 at the hands of Prussia was partially blamed on the growth of the superiority of the German university system of the 19th century, and led to another serious reform of the French university. In the 1880s, the "licence" (bachelor) degree is divided into, for the Faculty of Letters: Letters, Philosophy, History, Modern Languages, with French, Latin and Greek being requirements for all of them; and for the Faculty of Science, into: Mathematics, Physical Sciences and Natural Sciences; the Faculty of Theology is abolished by the Republic. At this time, the building of the Sorbonne was fully renovated.

May 1968–1970: Shutdown

The student revolts of the late 1960s were caused in part by the French government's failure to plan for a sudden explosion in the number of university students as a result of the postwar baby boom. The number of French university students skyrocketed from only 280,000 during the 1962–63 academic year to 500,000 in 1967–68, but at the start of the decade, there were only 16 public universities in the entire country. To accommodate this rapid growth, the government hastily developed bare-bones off-site faculties as annexes of existing universities (roughly equivalent to American satellite campuses). These faculties did not have university status of their own, and lacked academic traditions, amenities to support student life, or resident professors. One-third of all French university students ended up in these new faculties, and were ripe for radicalization as a result of being forced to pursue their studies in such shabby conditions. In 1966, after a student revolt in Paris, Christian Fouchet, minister of education, proposed "the reorganisation of university studies into separate two- and four-year degrees, alongside the introduction of selective admission criteria" as a response to overcrowding in lecture halls. Dissatisfied with these educational reforms, students began protesting in November 1967, at the campus of the University of Paris in Nanterre;Readings, p. 136. indeed, according to James Marshall, these reforms were seen "as the manifestations of the technocratic-capitalist state by some, and by others as attempts to destroy the liberal university". After student activists protested against the Vietnam War, the campus was closed by authorities on 22 March and again on 2 May 1968. Agitation spread to the Sorbonne the next day, and many students were arrested in the following week. Barricades were erected throughout the Latin Quarter, and a massive demonstration took place on 13 May, gathering students and workers on strike. The number of workers on strike reached about nine million by 22 May. As explained by Bill Readings:resident Charles de Gaulle">Charles_de_Gaulle.html" ;"title="resident Charles de Gaulle">resident Charles de Gaulleresponded on May 24 by calling for a referendum, and ..the revolutionaries, led by informal action committees, attacked and burned the Euronext Paris, Paris Stock Exchange in response. The Gaullism, Gaullist government then held talks with union leaders, who agreed to a package of wage-rises and increases in union rights. The strikers, however, simply refused the plan. With the French state tottering, de Gaulle fled France on May 29 for a French military base in Germany. He later returned and, with the assurance of military support, announced eneralelections ithinforty days. ..Over the next two months, the strikes were broken (or broke up) while the election was won by the Gaullists with an increased majority.

1970: Division

Following the disruption, de Gaulle appointed Edgar Faure as minister of education; Faure was assigned to prepare a legislative proposal for reform of the French university system, with the help of academics.Berstein, p. 229. Their proposal was adopted on 12 November 1968;Berstein, p. 229; . in accordance with the new law, the faculties of the University of Paris were to reorganize themselves.Conac, p. 177. This led to the division of the University of Paris into 13 universities. In 2017, Paris 4 andParis 6

Pierre and Marie Curie University (french: link=no, Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie, UPMC), also known as Paris 6, was a public research university in Paris, France, from 1971 to 2017. The university was located on the Jussieu Campus in the La ...

universities merged to form the Sorbonne University. In 2019, Paris 5 and Paris 7 universities merged to form the new Paris Cité University

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Sin ...

, leaving the number of successor universities at 11.

The successor universities to the University of Paris are now split over the three academies of the Île-de-France region.

Most of these successor universities have joined several groups of universities and higher education institutions in the Paris region, created in the 2010s.

Notable people

Faculty

François Guizot

François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (; 4 October 1787 – 12 September 1874) was a French historian, orator, and statesman. Guizot was a dominant figure in French politics prior to the Revolution of 1848.

A conservative liberal who opposed the a ...

File:Jean-Jacques_Amp%C3%A8re.jpg, Jean-Jacques Ampère

Jean-Jacques Ampère (12 August 1800 – 27 March 1864) was a French philologist and man of letters.

Born in Lyon, he was the only son of the physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836). Jean-Jacques' mother died while he was an infant. (But ...

File:Victor_Cousin_by_Gustave_Le_Gray,_late_1850s-crop.jpg, Victor Cousin

File:Henri_Poincar%C3%A9-2.jpg, Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré ( S: stress final syllable ; 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as "The ...

Alumni

John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

File:Carlo_Crivelli_007.jpg, Thomas Aquinas

File:Denis_Diderot_111.PNG, Denis Diderot

File:Nicolas_de_Largilli%C3%A8re,_Fran%C3%A7ois-Marie_Arouet_dit_Voltaire_(vers_1724-1725)_-001.jpg, Voltaire

File:Honor%C3%A9_de_Balzac_(1842)_Detail.jpg, Honoré de Balzac

Bibliothèque Inguimbertine

The Bibliothèque Inguimbertine is a scholarly library located in Carpentras

Carpentras (, formerly ; Provençal Occitan: ''Carpentràs'' in classical norm or ''Carpentras'' in Mistralian norm; la, Carpentoracte) is a commune in the Vauc ...

and the museums of Carpentras

* Aklilu Habte-Wold, Ethiopian politician who served in Haile Selassie's cabinet

* Leonardo López Luján, Mexican archaeologist and director of the Templo Mayor Project

* Darmin Nasution, Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs of Indonesia

* Maria Vasillievna Pavlova (née Gortynskaia) (1854-1939), paleontologist and academician

* Jean Peyrelevade, French civil servant, politician and business leader.

* Issei Sagawa, cannibal and murderer

* Tamara Gräfin von Nayhauß

Countess Tamara von Nayhauss (german: Tamara Gräfin von Nayhauß) (born 23 July 1972) is a German television presenter, blogger, and socialite.

Early life and education

Von Nayhauss was born on 23 July 1972 in Bonn to Count Mainhardt von Nay ...

, German television presenter

* Michel Sapin, Deputy Minister of Justice from May 1991 to April 1992, Finance Minister from April 1992 to March 1993, and Minister of Civil Servants and State Reforms from March 2000 to May 2002.

* Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Head of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement

* Ahmad al-Tayyeb, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar

* Pol Theis

Pol Theis (born February 10, 1968) is a Luxembourger attorney and interior designer. He is the founder and principal of the international interior design firm P&T Interiors, which is based in New York City. Before pursuing interior design, he was a ...

, attorney, interior designer, and founder of P&T Interiors in New York City

* Jean-Pierre Thiollet, French writer

* Loïc Vadelorge

Loïc Vadelorge, born 26 November 1964, graduate from École Normale Supérieure Lettres et Sciences Humaines, is a French historian, teacher of contemporary history at the Paris 13 University, after having been Senior Lecturer at the Versailles S ...

, French historian

* Yves-Marie Bercé, historian, winner of the Madeleine Laurain-Portemer

Madeleine Laurain-Portemer (7 June 1917 – 15 August 1996) was a 20th-century French historian, specializing in the history of Mazarin and his time, married to Jean Portemer (1911-1998).

Biography

An archivist palaeographer graduated from the ...

Prize of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques and member of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques

* Phulrenu Guha

Dr Phulrenu Guha (née Dutta, Bengali:ফুলরেণু গুহ; born 13 August 1911) was an Indian activist, educationist and politician, belonging to the Indian National Congress. She was a member of the Rajya Sabha the Upper house of ...

, Indian Bengali politician and educationist, class of 1928

* Antoine Compagnon

Antoine Compagnon (born 20 July 1950 in Brussels, Belgium) is a Professor of French Literature at Collège de France, Paris (2006–), and the Blanche W. Knopf Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, New York City ( ...

, professor of French literature at the Collège de France

* Anatole Félix Le Double

Félix Odoart Anatole Pierre Xavier Le Double (14 August 1848 – 22 October 1913) was a French anatomist and physician. He studied and taught comparative anatomy and took a special interest in anthropology and differences in anatomy and took an ev ...

, anatomist, physician, and academic

* Philippe Contamine, historian, member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres

* Pridi Banomyong, a Thai politician and professor who played an important role in drafting Thailand's first constitutions.

* Denis Crouzet

Denis Bertrand Yves Crouzet (born 10 March 1953) is a French historian specialising in the history of the early modern period and particularly in the French Wars of Religion during the Protestant Reformation, reformation. He is a professor at Paris ...

, Renaissance historian, winner of the Madeleine Laurain-Portemer Prize of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques

* Marc Fumaroli, member of the Académie française and professor at the Collège de France

* Olivier Forcade, historian of Political and International relations at the University of Paris-Sorbonne

Paris-Sorbonne University (also known as Paris IV; french: Université Paris-Sorbonne, Paris IV) was a public research university in Paris, France, active from 1971 to 2017. It was the main inheritor of the Faculty of Humanities of the Universit ...

and Sciences-Po Paris

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future

, type = Public research university''Grande école''

, established =

, founder = Émile Boutmy

, accreditation ...

, member of the French National Council of Universities

* Edith Philips

Edith Philips (November 3, 1892 – July 19, 1983) was an American writer and academic of French literature. Her research focused on eighteenth-century French literature and French emigration to the United States. She was a Guggenheim Fellow (1 ...

, American writer and educator

* Jean Favier, historian, member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, president of the French Commission for UNESCO

* Nicolas Grimal, egyptologist, winner of the Gaston-Maspero prize of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres et member of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, winner of the Diane Potier-Boes Prize of the Académie française.

* John Kneller

John William Kneller, OAP (October 15, 1916 – July 2, 2009) was an English-American French language professor and scholar, and the fifth President of Brooklyn College.

Biography

Kneller was born in Oldham, England, to John W. Kneller and M ...

(1916–2009), English-American professor and fifth president of Brooklyn College

Brooklyn College is a public university in Brooklyn, Brooklyn, New York. It is part of the City University of New York system and enrolls about 15,000 undergraduate and 2,800 graduate students on a 35-acre campus.

Being New York City's first publ ...

* Claude Lecouteux, professor of Medieval German literature, winner of the Strasbourg Prize of the Académie française

* Jean-Luc Marion, Philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, member of the Académie française

* Danièle Pistone, Musicologist, member of the Académie des beaux-arts

* Jean-Yves Tadié

Jean-Yves Tadié (born 7 September 1936) is a French writer, biographer, and academic, noted particularly for his work on Marcel Proust.

Biography

Tadié studied at the ''École normale supérieure'' in Paris, graduating in 1956. He began to pu ...

, professor of French literature, Grand Prize of the Académie française

* David Ting

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, at the European Commission since 1975

* Jean Tulard, historian, member of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques

* Khieu Samphan, former Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

leader and head of state of Democratic Kampuchea

* Haïm Brézis

The name ''Haim'' can be a first name or surname originating in the Hebrew language, or deriving from the Old German name ''Haimo''.

Hebrew etymology

Chayyim ( he, חַיִּים ', Classical Hebrew: , Israeli Hebrew: ), also transcribed ''Haim ...

, French mathematician who mainly works in functional analysis and partial differential equation

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which imposes relations between the various partial derivatives of a Multivariable calculus, multivariable function.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" to be sol ...

s

* Philippe G. Ciarlet

Philippe G. Ciarlet (born 14 October 1938) is a French mathematician, known particularly for his work on mathematical analysis of the finite element method. He has contributed also to elasticity, to the theory of plates and shells and differentia ...

, French mathematician, known particularly for his work on mathematical analysis of the finite element method. He has contributed also to elasticity, to the theory of plates and shells

In continuum mechanics, plate theories are mathematical descriptions of the mechanics of flat plates that draws on the theory of beams. Plates are defined as plane structural elements with a small thickness compared to the planar dimensions ...

and differential geometry

Differential geometry is a mathematical discipline that studies the geometry of smooth shapes and smooth spaces, otherwise known as smooth manifolds. It uses the techniques of differential calculus, integral calculus, linear algebra and multili ...

* Gérard Férey

Gérard Férey (14 July 1941 – 19 August 2017) was a French chemist who was a member of the French Academy of Sciences and a professor at the Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines University. He specialized in the physical chemistry of solid ...

, was a French chemist who specialized in the Physical chemistry of solids and materials. He focused on the crystal chemistry

Crystal chemistry is the study of the principles of chemistry behind crystals and their use in describing structure-property relations in solids. The principles that govern the assembly of crystal and glass structures are described, models of many ...

of inorganic fluorides and on porous solids

* Jacques-Louis Lions, was a French mathematician who made contributions to the theory of partial differential equation

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which imposes relations between the various partial derivatives of a Multivariable calculus, multivariable function.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" to be sol ...

s and to stochastic control

Stochastic control or stochastic optimal control is a sub field of control theory that deals with the existence of uncertainty either in observations or in the noise that drives the evolution of the system. The system designer assumes, in a Bayes ...

, among other areas

* Marc Yor, was a French mathematician well known for his work on stochastic processes

In probability theory and related fields, a stochastic () or random process is a mathematical object usually defined as a family of random variables. Stochastic processes are widely used as mathematical models of systems and phenomena that appe ...

, especially properties of semimartingales, Brownian motion and other Lévy processes, the Bessel processes In mathematics, a Bessel process, named after Friedrich Bessel, is a type of stochastic process.

Formal definition

The Bessel process of order ''n'' is the real-valued process ''X'' given (when ''n'' ≥ 2) by

:X_t = \, W_t \, ,

whe ...

, and their applications to mathematical finance

Mathematical finance, also known as quantitative finance and financial mathematics, is a field of applied mathematics, concerned with mathematical modeling of financial markets.

In general, there exist two separate branches of finance that require ...

* Bernard Derrida

Bernard Derrida (; born 1952) is a French theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in statistical mechanics, and is the eponym of ''Derrida plots'', an analytical technique for characterising differences between Boolean networks.

Biogr ...

, a French theoretical physicist. He is best known for his work in statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

, and is the eponym of ''Derrida plots'', an analytical technique for characterising differences between Boolean networks.

* François Loeser

François Loeser (born August 25, 1958) is a French mathematician. He is Professor of Mathematics at the Pierre-and-Marie-Curie University in Paris. From 2000 to 2010 he was Professor at École Normale Supérieure. Since 2015, he is a senior member ...

, a French mathematician who specialized in algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

and is best known for his work on motivic integration, part of it in collaboration with Jan Denef

Jan Denef (born 4 September 1951) is a Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and Ge ...

* Achille Mbembe, Cameroonian Intellectual historian, Political philosophy, author of ''On the Postcolony

''On the Postcolony'' is a collection of critical essays by Cameroonian philosopher and political theorist Achille Mbembe. The book is Mbembe's most well-known work and explores questions of power and subjectivity in postcolonial Africa. The book ...

'', introduced the concept of necropolitics

* Claire Voisin

Claire Voisin (born 4 March 1962) is a French mathematician known for her work in algebraic geometry. She is a member of the French Academy of Sciences and holds the chair of Algebraic Geometry at the Collège de France.

Work

She is noted for h ...

, French mathematician known for her work in algebraic geometry

Algebraic geometry is a branch of mathematics, classically studying zeros of multivariate polynomials. Modern algebraic geometry is based on the use of abstract algebraic techniques, mainly from commutative algebra, for solving geometrical ...

* Jean-Michel Coron

Jean-Michel Coron (born August 8, 1956) is a French people, French mathematician. He first studied at École Polytechnique, where he worked on his PhD thesis advised by Haïm Brezis. Since 1992, he has studied the control theory of partial differ ...

, French mathematician who studied the control theory of partial differential equation

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which imposes relations between the various partial derivatives of a Multivariable calculus, multivariable function.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" to be sol ...

s, and which includes both control and stabilization

* Michel Talagrand, French mathematician specialized in functional analysis and probability theory and their applications

* Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, French physicist who specialized in methods of laser cooling and trapping atoms

* Serge Haroche

Serge Haroche (born 11 September 1944) is a French-Moroccan physicist who was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physics jointly with David J. Wineland for "ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual q ...

, French physicist who specialized in quantum physics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, qua ...

, whose other works developed laser spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

* Riad Al Solh First Prime-minister of Lebanon

* Benal Nevzat İstar Arıman (1903–1990), one of the first woman members of the Turkish parliament (1935)

* Abdelkebir Khatibi

Abdelkebir Khatibi ( ar, عبد الكبير الخطيبي) (11 February 1938 – 16 March 2009) was a prolific Moroccan literary critic, novelist, philosopher, playwright, poet, and sociologist. Affected in his late twenties by the rebellious ...

, Moroccan literary critic, novelist, philosopher, playwright, poet, and sociologist

* Muhammad Shahidullah, Bengali linguist, educationalist, and social reformer

* Wu Songgao

Wu Songgao (, 1898–1953) was a politician, jurist and political scientist in the Republic of China. He was an important politician during the Wang Jingwei regime. He was born in Wuxian (now, Wuzhong District and Xiangcheng District, Suzhou), J ...

(1898–1953), Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

politician, jurist and political scientist

* Abdul Hafeez Mirza (1939-2021) Pakistani tourism worker, cultural activist and Professor of French. Recipient of Ordre des Palmes Academiques

A suite, in Western classical music and jazz, is an ordered set of instrumental or orchestral/concert band pieces. It originated in the late 14th century as a pairing of dance tunes and grew in scope to comprise up to five dances, sometimes w ...

* Frederic Scheer

Frederic Scheer is a French-American entrepreneur and inventor. He is the founder of multiple companies, including Interpart, Biodegradable Products Institute, Cereplast, Biocorp, and Alercell. He has 15 US patents under his name in biotechnolog ...

, French-American entrepreneur and inventor

Nobel prizes

Alumni

The Sorbonne has taught 11French presidents

The president of France is the head of state of France. The first officeholder is considered to be Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who was elected in 1848 and provoked the 1851 self-coup to later proclaim himself emperor as Napoleon III. His coup, w ...

, almost 50 French heads of government, 2 Popes, as well as many other political and social figures. The Sorbonne has also educated leaders of Albania, Canada, the Dominican Republic, Gabon, Guinea, Iraq, Jordan, Kosovo, Tunisia and Niger among others.

List of Nobel Prize winners who had attended the University of Paris or one of its thirteen successors.

# Albert Fert (PhD) – 2007

# Alfred Kastler

Alfred Kastler (; 3 May 1902 – 7 January 1984) was a French physicist, and Nobel Prize laureate.

Biography

Kastler was born in Guebwiller (Alsace, German Empire) and later attended the Lycée Bartholdi in Colmar, Alsace, and École Normale Sup ...

(DSc) – 1966

# Gabriel Lippmann (DSc) – 1908

# Jean Perrin

Jean Baptiste Perrin (30 September 1870 – 17 April 1942) was a French physicist who, in his studies of the Brownian motion of minute particles suspended in liquids ( sedimentation equilibrium), verified Albert Einstein’s explanation of this ...

(DSc) – 1926

# Louis Néel (MSc) – 1970

# Louis de Broglie (DSc) – 1929

# Marie Curie (DSc) – 1903, 1911

# Pierre Curie (DSc) – 1903

# Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (DSc) – 1991

# Serge Haroche

Serge Haroche (born 11 September 1944) is a French-Moroccan physicist who was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physics jointly with David J. Wineland for "ground-breaking experimental methods that enable measuring and manipulation of individual q ...

(PhD, DSc) – 2012

# Frédéric Joliot-Curie (DSc) – 1935

# Gerhard Ertl (Attendee) – 2007

# Henri Moissan (DSc) – 1906

# Irène Joliot-Curie (DSc) – 1935

# Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff (Attendee) – 2007

# André Frédéric Cournand

André Frédéric Cournand (September 24, 1895 – February 19, 1988) was a French-American physician and physiologist.

Biography

Cournand was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1956 along with Werner Forssmann and Dickinson W ...

(M.D) – 1956

# André Lwoff (M.D, DSc) – 1965

# Bert Sakmann (Attendee) – 1991